Introduction

Weed infestation is a growing and increasing challenge to wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) production worldwide. American sloughgrass [Beckmannia syzigachne (Steud.) Fernald] is one of the most widespread grassy weed species in winter wheat planting areas across East Asia and is also widely distributed in Europe and North America (GBIF 2025). This species competes intensely with wheat for space, water, nutrients, and light, and reduces the number of grains per spike and grain weight; its infestations also frequently increase lodging and the incidence of pests and diseases (G Chen et al. Reference Chen, Chen, Liu, Wu, Luo, Huang, Yang and Ding2025a; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Zhang, Shen, Mao, Wei, Wei, Zuo, Li, Song and Qiang2020; S Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Liu and Zhuang1999; Z Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Li, Wang, Valverde and Qiang2019). Li et al. (Reference Li, Rao, Dong and Zhang2010) reported that a density of 30 B. syzigachne plants m− 2 reduced wheat yield by >50%. In 2024, we surveyed 936 wheat fields in Jiangsu Province, China, and found that the average dominance value of B. syzigachne was substantially higher than those of 155 other weed species (G Chen et al. Reference Chen, Huang, Xue, Zhu, Chen and Wu2025b).

Chemical control remains the primary strategy for weed management in wheat fields worldwide, while B. syzigachne has evolved resistance to several important wheat herbicides (Li et al. Reference Li, Du, Liu, Yuan and Wang2014, Reference Li, Liu, Chi, Guo, Luo and Wang2015; Yin et al. Reference Yin, Jiang, Liao, Cao, Huang and Zhao2024). Our previous study demonstrated hormetic effects of higher doses of two acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase)-inhibiting herbicides, fenoxaprop-P-ethyl and pinoxaden, on an B. syzigachne population holding an ACCase I1781L mutation (G Chen et al. Reference Chen, Xue, Yu and Mao2025c). These findings underscore the urgent need for sustainable and effective management strategies to combat B. syzigachne in wheat fields.

Beckmannia syzigachne reproduces by seed, and its seeds are the primary source of its occurrence and persistence in fields. Therefore, knowledge of its seed germination and early seedling growth biology is fundamental for developing precise and effective management strategies. Previous studies have shown that weed germination traits frequently range greatly among populations, reflecting adaptations to heterogeneous environmental conditions (Kraehmer et al. Reference Kraehmer, Laber, Rosinger and Schulz2014). For instance, our previous research on 242 Chinese sprangletop [Leptochloa chinensis (L.) Nees] populations and 327 populations of barnyard grass (Echinochloa spp.) revealed great intraspecific variations (An et al. Reference An, Chen, Liu, Wei and Chen2024; Y Chen et al. Reference Chen, Masoom, Huang, Xue and Chen2025; Masoom et al. Reference Masoom, An, Chen, Dai and Chen2025). Thus, a broad sampling of representative populations and systematic evaluation are essential to elucidate the biology of a target weed species.

Accurately predicting the development of B. syzigachne leaf stages is crucial for preparing management practices. Beckmannia syzigachne and wheat both belong to the Poaceae family and share similar physiological and ecological traits. Chemical control practices against grassy weeds are usually conducted from wheat emergence to periods before the jointing stage of wheat, with different growth stages requiring tailored management strategies. For example, several preemergence wheat herbicides hold high efficacy against B. syzigachne seedlings before the 1-leaf stage, which decreases greatly after the 2-leaf stage (G Chen et al. Reference Chen, Chen, Liu, Wu, Luo, Huang, Yang and Ding2025a). Hence, predicting the development of B. syzigachne leaf stages could be key information for preparing control strategies.

Temperature is a key environmental factor regulating seed germination, seedling emergence, and growth of plants. Therefore, studies on seed germination response to different temperatures and thermal requirements for early seedling development could be the basis for predicting B. syzigachne occurrence in fields.

In 2023, we collected seeds from 225 B. syzigachne populations from different wheat fields in Jiangsu Province, located in eastern China. We conducted systematic experiments with the aim of revealing: (1) seed germination characteristics response to different temperatures simulating typical sowing periods of winter wheat and (2) thermal requirements for different leaf stages of early seedling growth.

Materials and Methods

Seed Collection

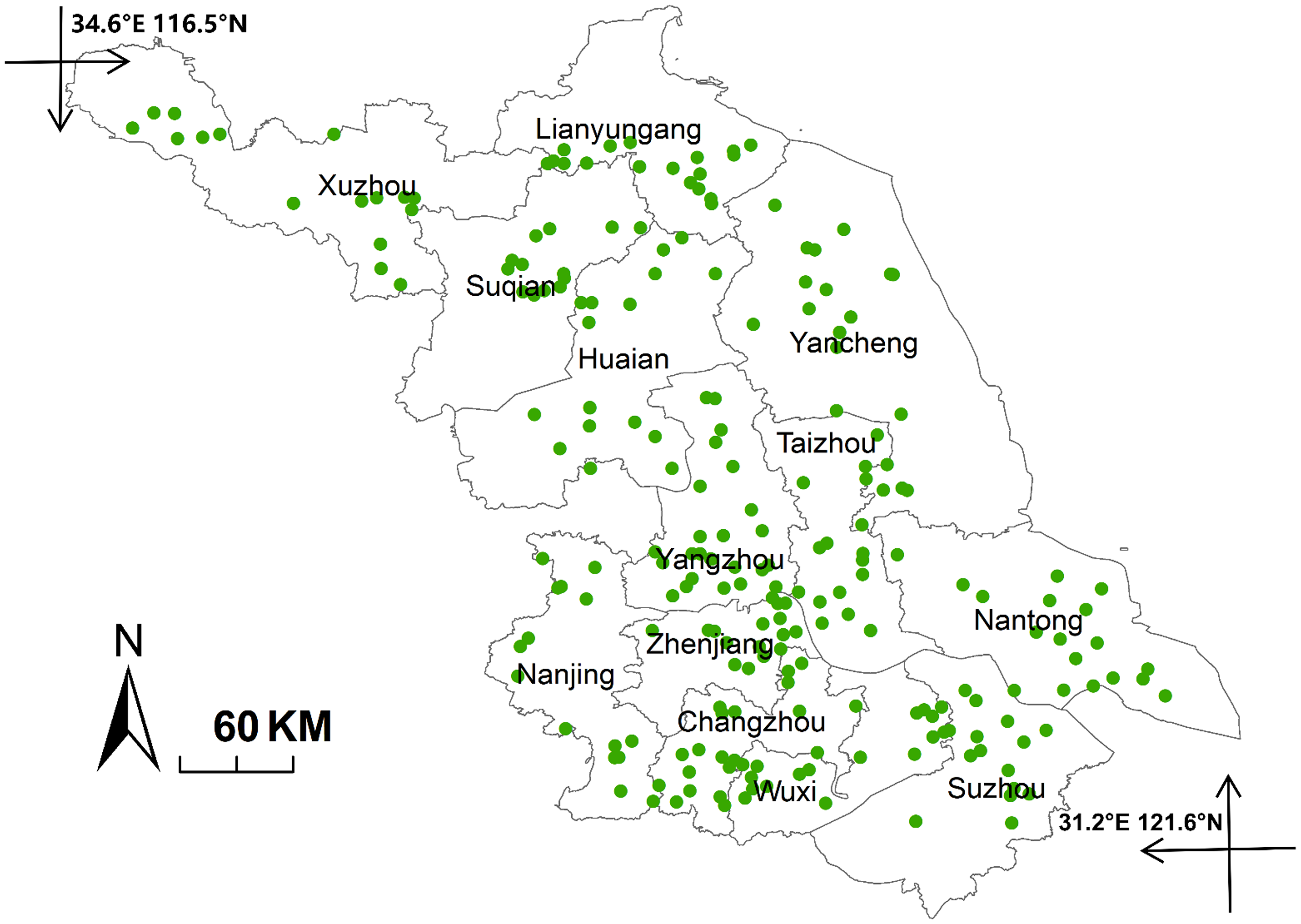

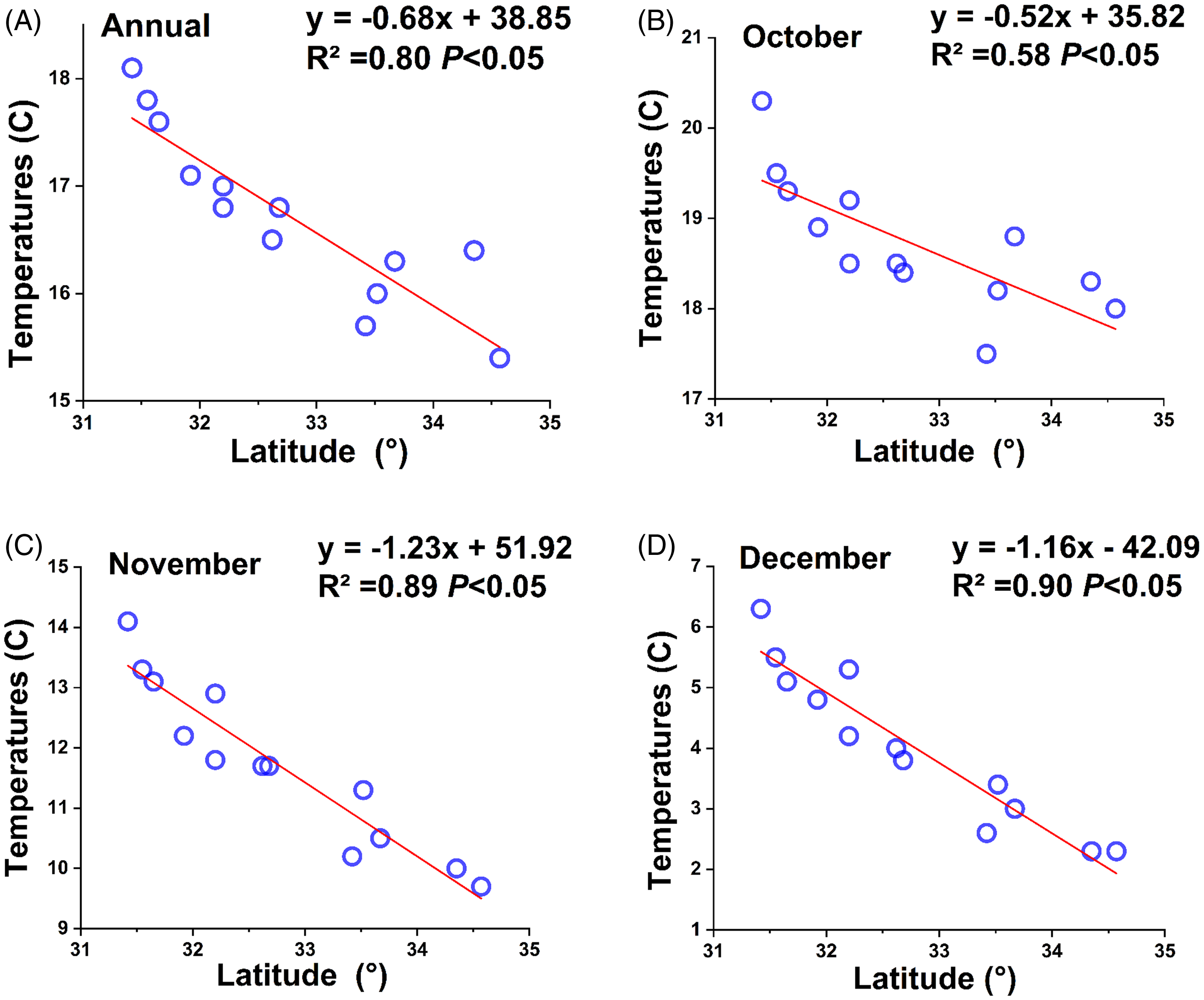

In May 2023, we visited 72 wheat-growing counties in Jiangsu Province to collect B. syzigachne populations. Seeds of 225 populations were collected from 225 different wheat fields (Figure 1), with a minimum distance of 5 km between adjacent populations, which spanned from 116.5°E to 121.6°E and from 31.2°N to 34.6°N. According to the Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook 2024 (https://tj.jiangsu.gov.cn/2024/index.htm, accessed: March 21, 2025), mean annual temperatures of 13 cities of Jiangsu Province ranged from 15.4 to 18.1 °C (Figure 2A); mean temperatures of the coldest month (January) ranged from 1.6 to 6.1 °C. Latitude showed significant (P < 0.05) negative correlations (Figure 2C and 2D) with annual mean temperatures in wheat sowing and early seedling growing periods (October to December).

Figure 1. Sites where seeds of Beckmannia syzigachne populations were collected in Jiangsu Province, China, in May 2023. Seeds of 225 populations were collected from 225 different wheat fields.

Figure 2. Regression between average latitudes and average temperatures in 2024 for annual (A), October (B), November (C), or December (D) for the 13 cities of Jiangsu Province, China. Data cited are from the Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook (https://tj.jiangsu.gov.cn/2024/index.htm).

At each seed-collecting field, B. syzigachne panicles with mature seeds from more than 100 plant individuals were randomly collected into a 100-mesh (30 cm by 45 cm) bag. Mature seeds were collected by gently scratching the bags to facilitate their detachment from panicles. Seeds were air-dried and stored in our lab at room temperature fluctuating from 15 to 25 °C for 1 yr, and then were transferred to a refrigerator with −20 °C for long-term storage. In July and August 2023, the 1,000-seed weight of each population was determined by weighing five replicates of 100 mature seeds from all collected samples.

Seed Germination Experiments

From August to December 2024, seed germination of the 225 populations at five different temperatures (12-h dark/12-h light,12,000 lx) was tested with growth chambers (HBZ-400B, Changzhou Haibo Instrument Equipment, Changzhou, Jiangsu, China). To simulate typical temperature conditions during winter wheat sowing periods, four diurnal temperature regimes were applied: 25/15 °C simulating average temperatures of early-sown winter wheat in warm seasons (commonly in early to middle October), 20/10 °C simulating average temperatures of standard-sown winter wheat (late October to early November), 15/5 °C simulating average temperatures of late-sown winter wheat (middle to late November), and 5/0 °C simulating average temperatures of very late sown winter wheat (December). Rao et al. (Reference Rao, Dong, Li and Zhang2008) reported that no B. syzigachne seed germination was observed under treatments with temperatures higher than 30 °C. Seeds of 10 randomly selected populations from 10 different cities were subjected to a constant temperature treatment of 30 °C. The B. syzigachne glume encloses a structure consisting of two waterproof airbags surrounding the true seed, which causes the seed to remain dormant. Before the experiment, the two pieces of airbag structures on each seed were fully uncoupled with tweezers. Two layers of filter paper were placed in 9-cm petri dishes and moistened with 6 ml distilled water; then, 50 randomly selected mature seeds from the same population were placed in each dish and incubated. Each treatment was replicated with three petri dishes per population. Germination was defined as the emergence of a visible radicle at least 1 mm in length. Germinated seeds were counted and removed every 2 d. The experiment lasted for 21 days after treatment (DAT), defined as days after the initiation of the temperature treatment. The experiment was repeated in November 2025 using 52 populations randomly selected from the total of 225 populations, with four populations sampled from each city in Jiangsu Province.

Determination of Accumulated Temperatures for Different Leaf Stages

From October to December 2023, greenhouse pot experiments were conducted using seedlings from 225 populations to evaluate accumulated temperature requirements for developing the second, third, fourth, and fifth leaves of seedlings. For each population, 50 mature seeds were incubated in petri dishes within growth chambers set at 25/15 °C (12-h light/12-h dark, 12,000 lx), following the same method described earlier. A vigorous seedling with a fully expanded first leaf was then transplanted into a plastic pot (7 cm by 7 cm by 10 cm), with 10 seedlings of the same population per pot. Each population was replicated with four pots. The potting substrate consisted of a 2:1 mixture of conventional wheat field soil (pH 5.6, organic matter 15 g kg−1) and commercial nutrient soil (pH 6.8, total nutrients 3.8%, organic matter >40%; Nanjing Duole Horticultural Co., Ltd., Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China), which was thoroughly mixed, moistened, and compacted before planting. Leaf stage progression was recorded when 8 out of 10 seedlings in a pot fully expanded a new leaf and marked as the beginning of that leaf stage (Meier Reference Meier and Schwartz2003). The end of each leaf stage was defined as the day before the initiation of the next stage. In this way, the duration of each leaf stage was determined. During the experiment, all windows and doors of the greenhouse were kept open. Daily air temperature was recorded using a thermometer positioned 2 m above the ground inside the greenhouse. The accumulated temperature was calculated as the sum of daily mean temperatures >0 C. The experiment was repeated from October to December 2024.

Statistical Analysis of Data

The data were subjected to one-way ANOVA using the SPSS version 16.0 statistical package (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were checked for normality and constant variance before analysis. Data were log-transformed before analysis. Nontransformed means were reported with statistical interpretation based on transformed data. Treatment means were separated using Fisher’s protected LSD test at P = 0.05. For each measured index, the coefficient of variation (CV) was determined to evaluate variation among populations. Response curves between germination percentages of each population and period or accumulative temperature were fit using a three-parameter logistic model in the drc package of R v. 3.1.3 (Ribeiro-Oliveira and Ranal Reference Ribeiro-Oliveira and Ranal2016).

![]() $\hskip 6.3pc{{{Y\; = \;a/[1\; + \;(x/e}}{{{)}}^{{b}}}{{]}}}$

[1]

$\hskip 6.3pc{{{Y\; = \;a/[1\; + \;(x/e}}{{{)}}^{{b}}}{{]}}}$

[1]

where Y denotes the accumulative germination percentage (%) at day x or accumulated temperature x after sowing; a is the upper limit; b indicates the slope; and e is the period or accumulated temperature required for 50% of total germination (GD50 or GT50). The days required for 90% of total germination (GD90) and the accumulated temperature required for 90% of total germination (GT90) were determined accordingly. Independent-sample t-tests were employed to compare significant differences in GD50, GT50, GD90, and GT90 between 20/10 and 25/15 °C treatments, using the SPSS v. 16.0 statistical package. Linear regressions were conducted to determine correlations between seed germination indices and seed weight or latitudes of seed-collecting sites, using the SPSS v. 16.0 statistical package.

Results and Discussion

Seed Germination under Different Temperatures

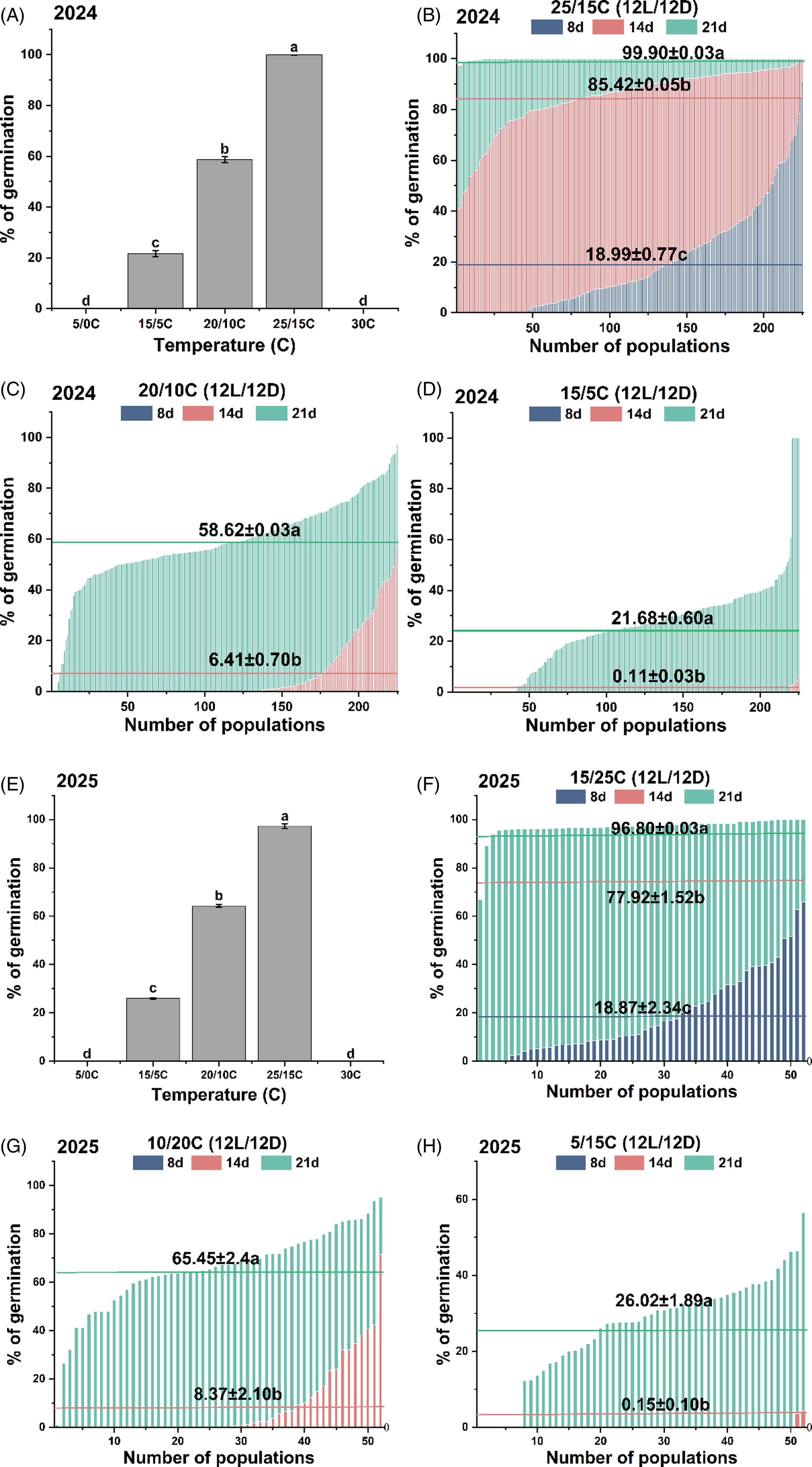

At 21 DAT with 5/0 °C or constant 30 C, no seeds germinated. Germination percentages differed significantly (P < 0.05) among different treatments (Figure 3A). Treatment at 25/15 °C was identified as the most optimal condition for germination. At 21 DAT of 25/15 °C, the average germination rate of 225 populations was 99.9%, and 92% of populations achieved complete germination (Figure 3B). At 21 DAT of 20/10 C, the average germination percentage of 225 populations was 58.6%, and 11.1% populations exceeded 80% germination (Figure 3C). Under 15/5C treatment, the average germination percentage of 225 populations at 21 DAT was 21.7% (Figure 3D), with only 2% populations exceeding 80% germination. CVs of germination percentages among populations also varied among treatments, being 14.9%, 199.1% and 598.5% for 14 DAT of 25/15, 20/10, and 15/5 C, respectively, and decreased to 0.4%, 29.3%, and 76.9% at 21 DAT, respectively. Results of seed germination experiments repeated in 2025 (Figure 3E–H) showed coincident patterns.

Figure 3. Germination percentages of Beckmannia syzigachne populations (225 for 2024; 52 for 2025) at different time points under varying temperature conditions (12/12-h light/dark). The horizontal line represents the average germination rate of three periods. Different letters in a subfigure indicate significant differences among different periods (P < 0.05). No seeds of overall tested populations germinated at 30 and 15/5 °C.

Seed germination represents the initial stage of B. syzigachne infestation of and damage in wheat fields. In the present study, 225 populations were collected from different wheat fields across Jiangsu Province. Together, our results showed that the optimum temperature for B. syzigachne seed germination was 25/15 °C, as 93% of the overall 225 populations tested showed the highest germination percentage at 14 or 21 DAT. Rao et al. (Reference Rao, Dong, Li and Zhang2008) tested seed germination of a B. syzigachne population collected from a wheat field in eastern China at constant temperatures of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 °C, and found that 10 °C was the optimal temperature, while 5, 20, 25, and 30 °C greatly inhibited seed germination. Zhu (Reference Zhu2008) tested B. syzigachne seed germination in response to 13 temperatures ranging from 4 to 40 °C and found that 17 to 22 °C was suitable. Therefore, seed germination biology might range greatly among different populations, which suggests the importance of knowing the germination biology of local B. syzigachne populations of target arable lands.

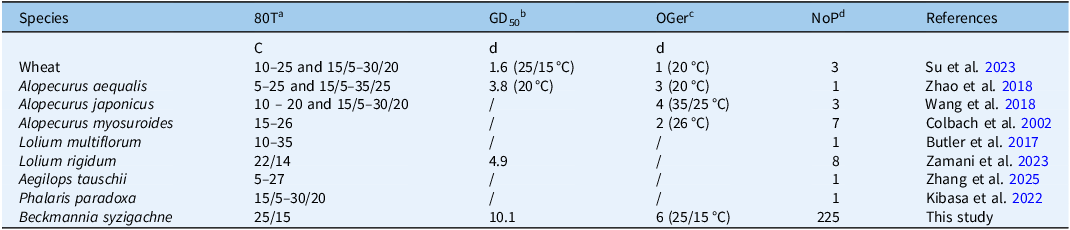

According to published reports, seed germination percentages of three wheat varieties were >80% under temperature conditions from 10 to 25 °C (Su et al. Reference Su, Yang, Ma, Li, Xu, Xue, Sun, Lu and Wu2023); comparatively, the range of suitable temperatures for B. syzigachne seed germination was much narrower and higher than those of other common wheat weeds (Table 1), including shortawn foxtail (Alopecurus aequalis Sobol.) (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Li, Guo, Zhang, Ge and Wang2018), Japanese foxtail (Alopecurus japonicus Steud.) (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Huang, Zhang, Liu and Wang2018), blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides Huds.) (Colbach et al. Reference Colbach, Chauvel, Dürr and Richard2002), rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaudin) (Zamani et al. Reference Zamani, Keshtkar, Sasanfar and Zand2023), Italian ryegrass [Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum (Lam.) Husnot] (Butler et al. Reference Butler, Celen, Webb, Krstic and Interrante2017), Tausch’s goatgrass (Aegilops tauschii Coss.) (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Yuan, Wang, Wang, Li, Zhou, Zhang, Yuan, Wang, Wang, Li and Zhou2025), and hood canarygrass (Phalaris paradoxa L.) (Kibasa et al. Reference Kibasa, Mahajan and Chauhan2022). The narrower range in optimal temperatures for seed germination constrained the occurrence and distribution of B. syzigachne. Beckmannia syzigachne is distributed in Asia, Europe, and North America (GBIF 2025), and it is reported to be troublesome in parts of wheat- or canola-planting (Brassica napus L.) areas in eastern Asia, particularly eastern and central China. Most rice (Oryza sativa L.) fields in eastern and central China sustain double- or triple-cropping systems every year, including one to two rice-growing seasons and another wheat- or canola-growing season. Thus, natural thermal resources during standard wheat-sowing seasons (usually from mid-October to early November) are sufficient for B. syzigachne seed germination. In northern areas, the lower temperatures during standard wheat-sowing seasons might be an important constraint to B. syzigachne seed germination. With ongoing global climate change (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Ismail and Ding2017), the suitable distribution areas for B. syzigachne might tend to increase, facilitating its dominance as a weed in more regions worldwide.

Table 1. Comparison of germination characteristics between wheat and common wheat field weeds.

a 80T, range of temperatures suitable for >80% germination.

b GD50, time required to reach 50% germination (days).

c Oger, onset of germination (days).

d NoP, number of populations.

The symbol “/” indicates that the corresponding data were not reported in the referenced literature.

Seed Germination Processes

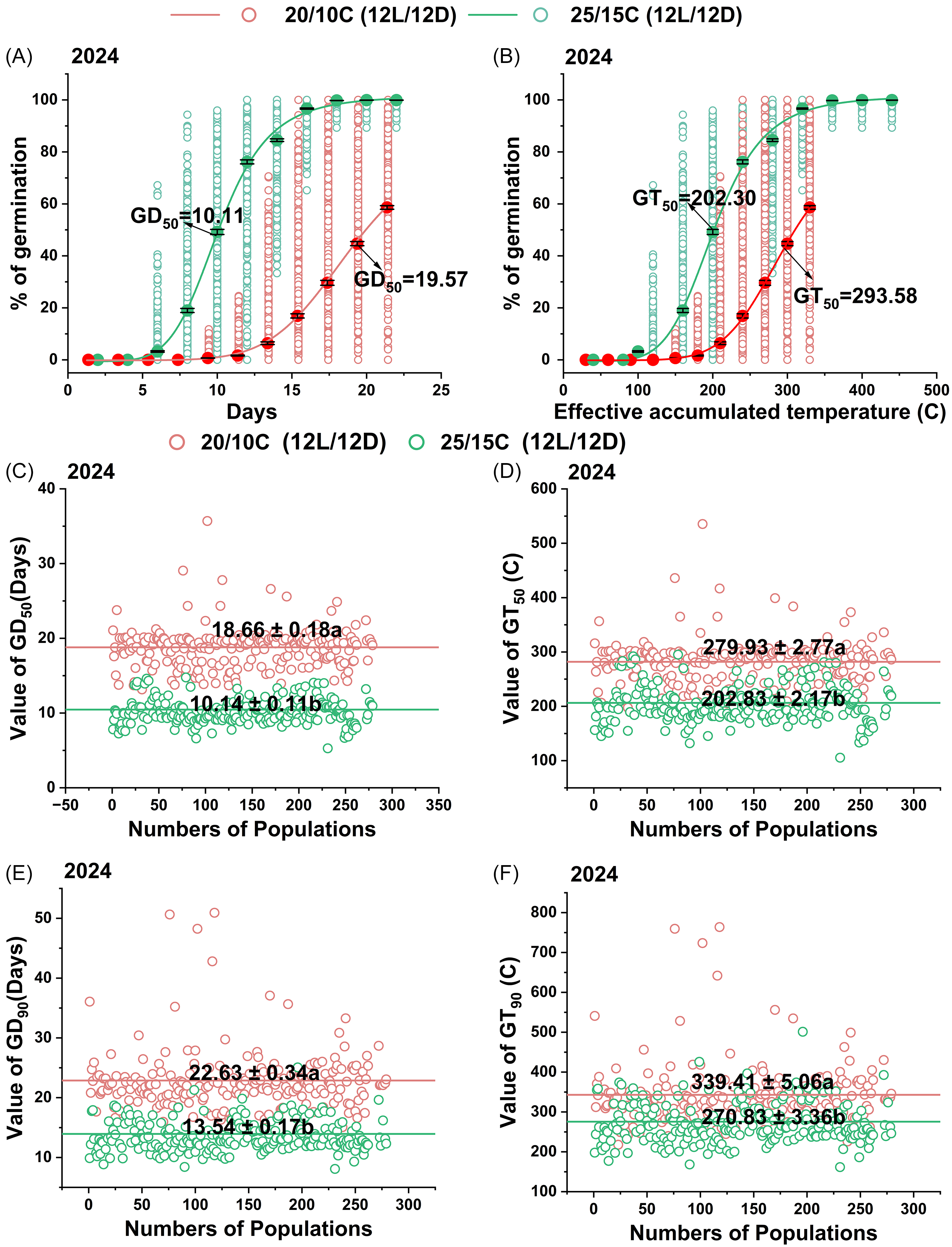

Beckmannia syzigachne germination initiated at 14, 10, and 6 DAT under treatments of 15/5, 20/10, and 25/15 °C (Figure 4A), respectively. At 25/15 °C, 222 populations were fitted to the logistic curve. On average, the GD50 of all populations under 25/15 °C treatment was 10.1 DAT (Figure 4A), corresponding to an accumulated temperature of 202.3 °C (Figure 4B); and GD50 (Figure 4C) and GD90 (Figure 4E) ranged from 5.3 to 14.8 DAT and 8.1 to 20.1 DAT, with mean values of 11.1 and 13.5 d. At 20/10 °C, 222 populations were fitted to the logistic curve; the average GD50 extended to 19.6 DAT, corresponding to an accumulated temperature of 293.6 °C; GD50 and GD90 ranged from 13.2 to 35.7 DAT and 14.5 to 50.9 DAT, with mean values of 18.7 and 22.6 DAT. GT50 (Figure 4D) and GT90 (Figure 4F) followed the same trend as GD50 and GD90. Moreover, GD50, GT50, GD90, and GT90 of 25/15 °C were all significantly lower than relative values of the 20/10 °C treatment (P < 0.05), by independent-sample t-tests. Results of experiments repeated in 2025 (Supplementary Figure S1) showed coincident patterns.

Figure 4. Germination curves of 225 Beckmannia syzigachne populations with increasing period (A) and accumulated temperature (B) and distributions of periods (GD50/90) or accumulated temperatures (GT50/90) needed for 50% (C and D) or 90% (E and F) germination of different populations. Different letters indicate significant differences between the two temperatures in the same subfigure (P < 0.05). Seed germination was tested with growth chambers (12-h dark/12-h light,12,000 lx).

Compared with other common grassy wheat weeds, B. syzigachne germinates more slowly and heterogeneously (Table 1). For example, A. aequalis was observed to initiate seed germination at 3 DAT under 15/5 °C, which showed germination percentages of 96% at 14 DAT (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Li, Guo, Zhang, Ge and Wang2018); A. japonicus started germination at 4 DAT under 35/25 °C, and achieved 80% germination at 6 DAT (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Huang, Zhang, Liu and Wang2018); A. myosuroides started germination on 2 DAT at a constant 26 °C, reaching 80% by 10 DAT (Colbach et al. Reference Colbach, Chauvel, Dürr and Richard2002). Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum achieved ≥95% germination at 8 DAT across four alternating temperature regimes from 10 to 35 °C (Lin et al. Reference Lin, Hua, Peng, Dong and Yan2018); L. rigidum reached 50% germination by 5 and 7 DAT at 22/14 and 17/7 °C (Zamani et al. Reference Zamani, Keshtkar, Sasanfar and Zand2023). Phalaris paradoxa showed ≥80% germination at 21 DAT under four alternating temperature regimes from 5 to 30 °C (Kibasa et al. Reference Kibasa, Mahajan and Chauhan2022).

Its slower and heterogeneous germination biology enables B. syzigachne to effectively avoid being collectively controlled. For example, in eastern China, farmers usually sow wheat seeds in later autumn and follow with an application of preemergence herbicides several days after sowing; and most farmers do not apply herbicides again until the temperature warms in February (G Chen et al. Reference Chen, Chen, Liu, Wu, Luo, Huang, Yang and Ding2025a); Thus, the delayed and heterogeneous seed germination of B. syzigachne enable a great portion of its seedlings to avoid preemergence herbicides and grow enough to be tolerant to many postemergence wheat herbicides applied in February.

Moreover, B. syzigachne seed germination was not adapted to temperature conditions simulating late- and very-late-planted winter wheat, which suggests lower risks of its infestation in late- and very-late-planted winter wheat fields. However, winter temperature fluctuations frequently show a warm period, which may also facilitate seed germination of B. syzigachne.

Accumulated Temperatures for Different Leaf Stages

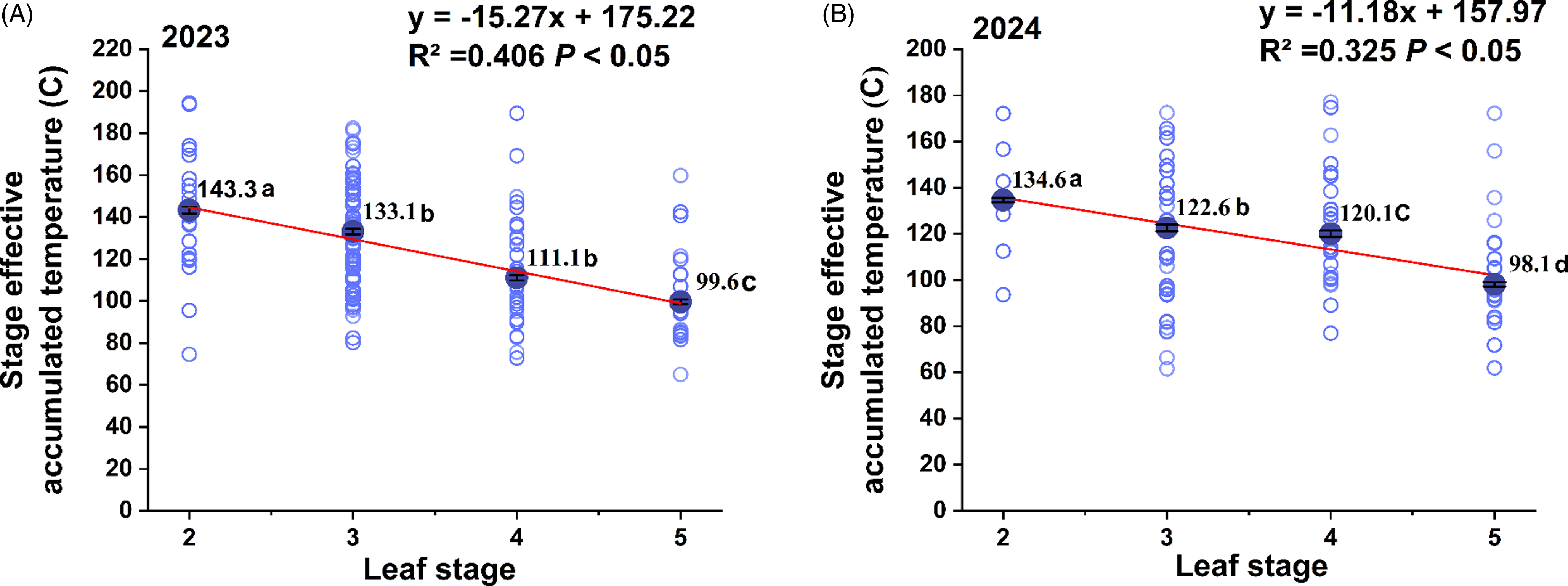

During the early leaf growth stage, the accumulated temperature required for each new leaf of B. syzigachne significantly (P < 0.05) decreased with increasing leaf age in both 2023 (Figure 5A) and 2024 (Figure 5B). Pooled across both years, accumulated temperatures for growing the second, third, fourth, and fifth leaves were 139.0 °C ± 1.0, 127.8 ± 1.0, 115.6 ± 1.0, and 98.9 ± 0.7 °C, respectively. The average accumulated temperature required for growing a new leaf was estimated to be between 118.9 and 121.3 °C.

Figure 5. Distributions of accumulated temperatures required for growing different leaves of Beckmannia syzigachne early seedlings in 225 populations. Different letters represent significant differences among different leaf stages (P < 0.05). Greenhouse pot experiments were conducted using seedlings from 225 populations collected from wheat fields in eastern China to evaluate accumulated temperature requirements for developing the second, third, fourth, and fifth leaves of seedlings.

Field observations in China showed that wheat seedlings generally require 70 to 80 °C of accumulated temperature to produce each new leaf during early seedling growth (Li et al. Reference Li, Yin, Liu, Zhou, Li, Niu, Niu and Ma2012). Together, our results imply that B. syzigachne required higher accumulated temperatures for developing new leaves at early seedling growth stages than wheat and other common wheat weeds reported. Ball et al. (Reference Ball, Klepper and Rydrych1995) compared wheat with five common wheat weeds, including cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum L.), bulbous bluegrass (Poa bulbosa L.), jointed goatgrass (Aegilops cylindrica Host), L. perenne ssp. multiflorum, and wild oat (Avena fatua L.), and reported that in experiments in 1991, wheat required 111.1 °C for growing a new leaf, followed by A. fatua (92.6 °C), B. tectorum (66.2 °C), and P. bulbosa (58.7 °C); and in 1992, A. fatua required the highest accumulated temperature for growing a new leaf (123.5 °C), followed by wheat (101.0 °C), L. perenne ssp. multiflorum (88.5 °C), A. cylindrica (74.1 °C), P. bulbosa (69.3 °C), and B. tectorum (66.2 °C). The higher accumulated temperatures required for growing new leaves at early seedling growing stages also may possibly constrain B. syzigachne infestations in northern areas. Moreover, the accelerated seedling growth of B. syzigachne, which requires less accumulated thermal time as leaf number increases, suggests that this trait may reflect both an adaptation to the overwintering period in winter wheat cultivation systems and the potential effects of increased photosynthate allocation.

Influences of Latitude and Seed Weight

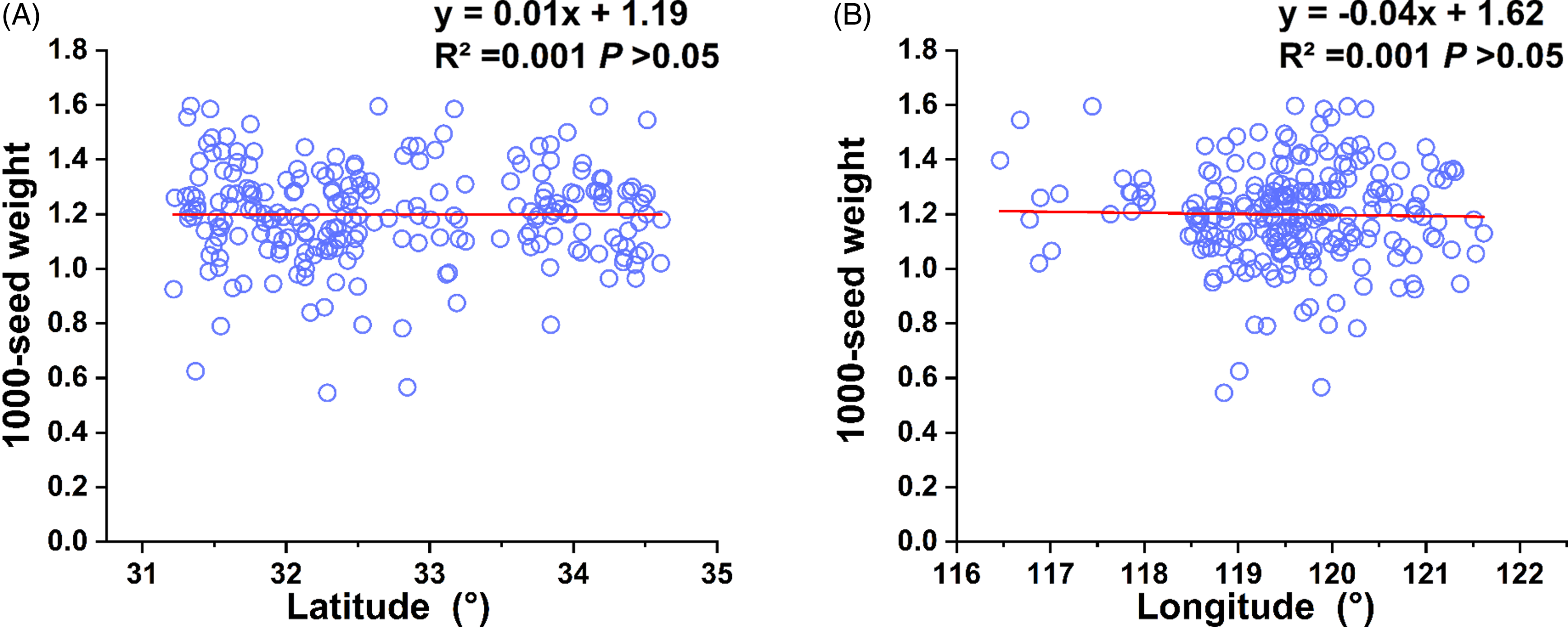

Thousand-seed weights of 225 B. syzigachne populations ranged from 0.5 to 1.6 g, with an average of 1.2 ± 0.01 g and a CV of 15%. No significant (P > 0.05) correlations were observed between seed weight and latitude of seed-collecting fields (Figure 6 A and B). No significant correlations were observed between germination percentages of different treatments and seed weight (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1). The 1,000-seed weight of Beckmannia syzigachne was moderate among those of common grass weeds in wheat fields, such as A. fatua with 1,000-seed weight ranging from 15 to 33.8 g (Ionescu et al. Reference Ionescu, Ionescu, Georgescu, Săvulescu and Penescu2016), L. perenne ssp. multiflorum, 1.3 to 2.6 g (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021), A. japonicus, 1.4 to 1.6 g (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Zhang, Pan, Wang, Xu and Dong2016), and annual bluegrass (Poa annua L.), 0.2 to 0.3 g (Li et al. Reference Li, Bai, Li, Yan, Zhang, Zheng and Zhu2024).

Figure 6. Correlations between 1,000-seed weight of 225 Beckmannia syzigachne populations and latitude or longitude of seed collecting field. Seeds were collected from wheat fields in eastern China in May 2023.

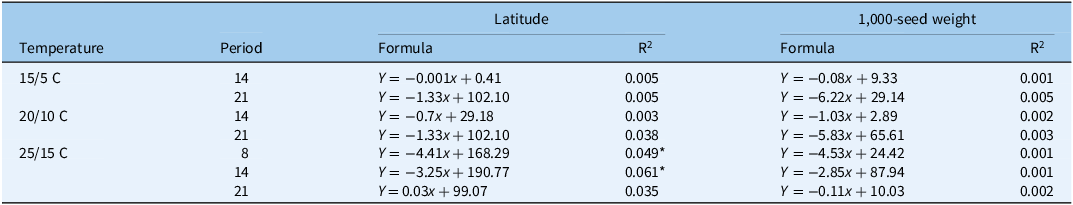

Table 2. Linear regressions between latitude of seed-collecting field or 1,000-seed weight (x) and seed germination rate of Beckmannia syzigachne (Y) at 8, 14, and 21 d after treatment at different temperatures. a

a Seed germination of 225 populations was tested with growth chambers (12-h dark/12-h light,12,000 lx). P < 0.05.

* Significant correlation at P < 0.05.

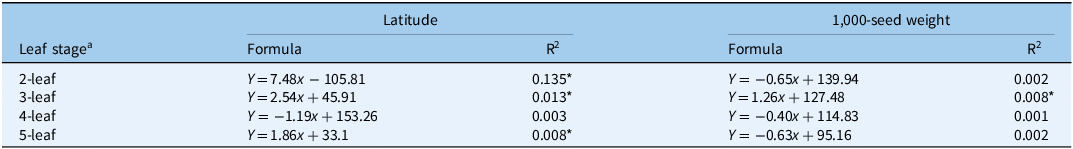

At 8 and 14 DAT at 25/15 C, germination percentages were significantly (P < 0.05) and negatively correlated with latitudes of seed-collecting fields. Accumulated temperatures required for growing the second, third, and fifth leaves were significantly and positively correlated with latitudes of seed-collecting fields. In addition, only the accumulated temperature for growing the third leaf showed a significant and positive correlation with 1,000-seed weight (Table 3).

Table 3. Linear regressions between accumulated temperatures (Y) for growing different leaves and latitude of seed-collecting field or 1,000-seed weight (x) of 225 Beckmannia syzigachne populations.

a Greenhouse pot experiments were conducted using seedlings from 225 populations to evaluate accumulated temperature requirements for developing the second, third, fourth, and fifth leaves of seedlings.

* Significant correlation at P < 0.05.

Seed germination can be affected by environmental cues experienced by the mother plant, and differences in germination characteristics of seeds from different maternal environments might be due to the epigenetic memory inherited from the mother plants (Nguyen et al. Reference Nguyen, Chen, Clark, Perez and Huo2021). Moreover, field seeds might experience different temperatures. Our previous study with 242 L. chinensis populations found that populations collected from northern areas significantly show higher germination percentages under different temperatures (An et al. Reference An, Chen, Liu, Wei and Chen2024). In seed-collecting areas, solar thermal resources decrease significantly with increasing latitude (Figure 2), which leads to slower B. syzigachne seedling growth in northern areas. Thus, preemergence chemical control against B. syzigachne in February may be more effective due to the higher sensitivities of younger seedlings in northern areas, and surviving seedlings might need a longer period to recover and accumulate nutrition for seeds. Moreover, B. syzigachne populations collected in northern areas significantly tended to require higher accumulated temperatures for growing a new leaf at early growing stages, which might also be due to distribution of solar thermal resources. Our previous study with 327 Echinochloa spp. populations also suggested that accumulated temperatures required for seed germination under treatments with higher temperatures were significantly lower (Y Chen et al. Reference Chen, Masoom, Huang, Xue and Chen2025). Thus, continuous higher temperatures may better facilitate seedling development of plants (Vu et al. Reference Vu, Xu, Gevaert and De Smet2019).

Management Strategies

Currently, weed management in many wheat-planting areas worldwide relies on chemical control. In eastern China, most growers apply preemergence herbicides after sowing wheat seeds (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Xiang, Zong, Ma, Wu, Liu, Zhou and Bai2019). The slow and heterogeneous germination of B. syzigachne highlighted the importance of timing and herbicide selection for preemergence chemical control. Beckmannia syzigachne seedlings before the 1-leaf stage are highly sensitive to several preemergence wheat herbicides such as flufenacet, acetochlor, pyroxasulfone, and isoproturon (G Chen et al. Reference Chen, Chen, Liu, Wu, Luo, Huang, Yang and Ding2025a). Thus, the best timing for applying preemergence herbicides against B. syzigachne should be the 0.5-leaf stage, to collectively kill emerged seedlings and also continuously kill subsequent emerging seedlings (G Chen et al. Reference Chen, Chen, Liu, Wu, Luo, Huang, Yang and Ding2025a). Moreover, flufenacet frequently shows high efficacy against B. syzigachne for longer effective periods, which could be recommended to tackle B. syzigachne infestations in wheat fields (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wu, Xu, Gao, Zhang and Dong2017).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/wsc.2025.10078

Acknowledgments

We thank Hongcheng Zhang (Yangzhou University) for his guidance in this study. We also thank Yang Chen and Kai An, both from Yangzhou University, for their help collecting seeds.

Funding statement

This study was funded by the National Key R&D Program Projects (2021YFD1700100), Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX24_3792), the Jiangsu Province Agricultural Science and Technology Independent Innovation Fund Project (CX (24) 1026), and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.