“Opulence and freedom, the two greatest blessings men can possess.”

—Adam Smith (LJA iii.111)

Introduction

Capitalism is in trouble,Footnote 1 or so we have been told. Recently, there has been a surge in interest in capitalism and criticisms thereof. For example, The Economist has a special feature article on “The Next Capitalist Revolution,”Footnote 2 while Foreign Affairs published “The Future of Capitalism.”Footnote 3 Within a short space of time, many books have been published, including The Future of Capitalism, Capitalism in America, Radical Markets, Can American Capitalism Survive?, The Myth of Capitalism, and Capitalism, Alone. Footnote 4

These titles were published before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world. Since then, the trend has accelerated with a growing sense of urgency, as is shown by a stream of books, including Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire, The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, The Capitalist Manifesto, and Capitalism and Crises, to name just a few.Footnote 5 The Oxford Review of Economic Policy featured seventeen articles on capitalism by some of the most distinguished economists in 2021.Footnote 6

No doubt, this surge of capitalism studies reflects the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008–2009 and the subsequent Great Recession. A crisis casts doubt on existing policy, institutions, and ideas, demanding their revision. A post-crisis world is a world of policy controversies.Footnote 7 Needless to say, not all the challenges and issues we now face are necessarily related to the GFC, and many of them were already discussed before the GFC. Also, those seemingly contemporary challenges and issues are not unique to capitalism. However, the GFC has been a catalyst revealing that the challenges today’s world faces are ones that today’s capitalism faces. These post-crisis developments spilled over to politics, as the rise of “isms”—including protectionism, nationalism, and populism—testifies. Also, moral criticism of corporations gains momentum.

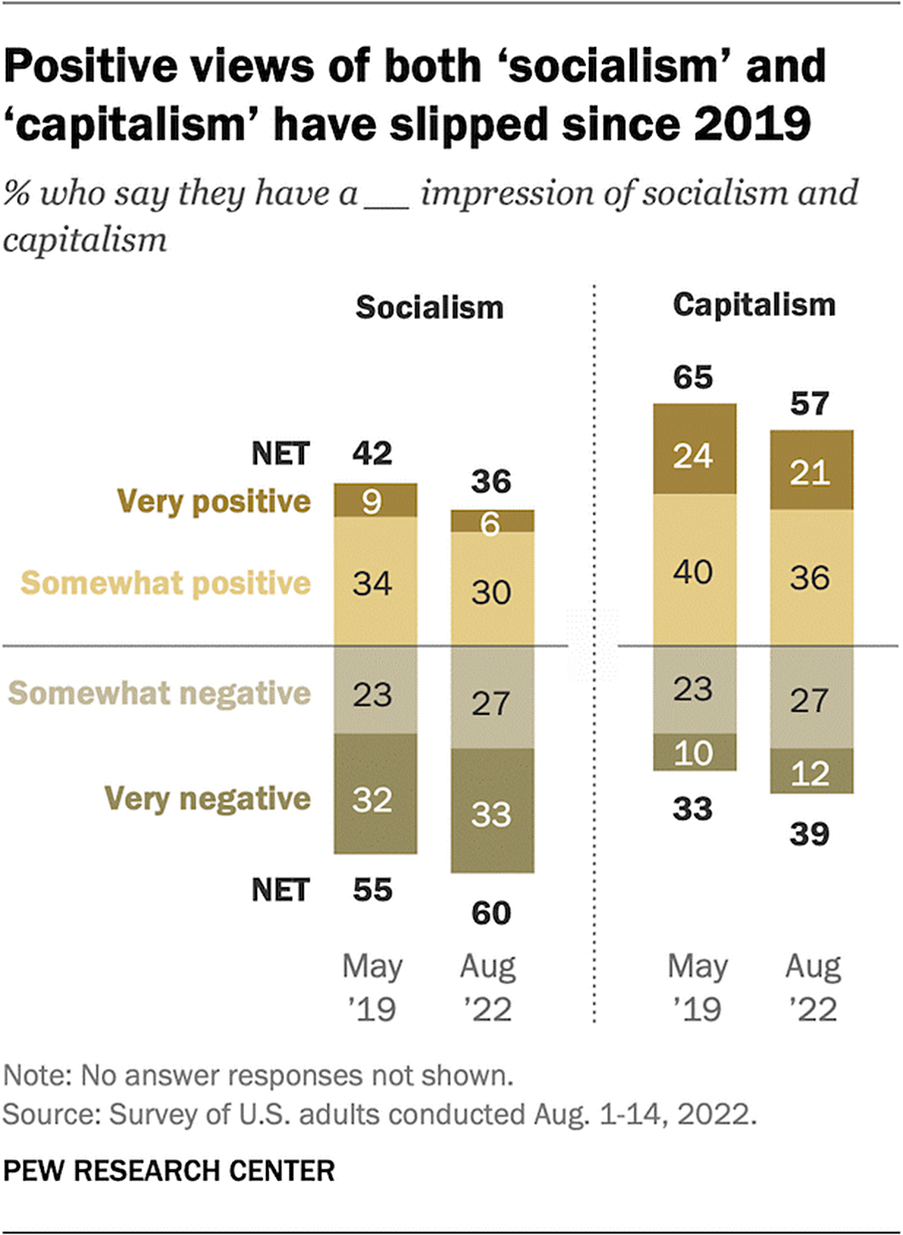

Against this background, it is noteworthy that the public shows very mixed feelings toward capitalism. According to the Pew Research Center, positive views of “capitalism” have slipped from 2019 to 2022 (see Figure 1).Footnote 8 On closer inspection, however, variations in their views of capitalism and socialism depend on gender, ethnicity, age, education, and family income. Especially for younger people ages 18–29, views of socialism are more positive than those of capitalism. Among the so-called “millennials” and Gen Zer’s,Footnote 10 favorable views toward “socialism” are almost the same as those toward capitalism.Footnote 11

Figure 1. Both socialism and capitalism are losing popularity.Footnote 9

This pattern of younger generations preferring socialism as much as capitalism is confirmed by a Fraser Institute survey: about half of people ages 18–24 in four English-speaking countries (United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia) prefer socialism as the ideal economic system.Footnote 12 Discontents with capitalism are not limited to the youth in those countries. When Edelman Trust Barometer asked citizens of twenty-eight markets whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement that “capitalism as it exists today does more harm than good in the world,” the majority agreed with it in twenty-two out of twenty-eight markets.Footnote 13

This recent surge of interest in capitalism is associated with an appreciation of Adam Smith as a potential source of insights for conceiving new, and presumably better, capitalism. Paul Collier criticizes the moral degradation of society since the 1970s, arguing that capitalism and economics need a renewed sense of shared morality, one based on Smithian sympathy among people.Footnote 14 Steven Pearlstein envisions a better capitalism where the pursuit of self-interest “is tempered by moral sentiments such as compassion, generosity and a sense of fair play,” with reference to Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Footnote 15 Recent assessments of Smith’s work make a forceful case for his relevance in contemporary capitalism.Footnote 16 Colin Mayer, calling The Theory of Moral Sentiments “arguably one of the most important books of the Age of the Enlightenment,” attempts to “provide the glue that cements the wealth of nations with our moral sentiments in a form in which, as Adam Smith intended, they are conjoined at the head as well as the hip.”Footnote 17

In this essay, I shall argue that Smith has a lot to teach us about the future of capitalism, although it is unhistorical to claim that everything is already in Smith’s works because current capitalism is also the product of history. I shall first examine recent discussions about current challenges and criticisms against capitalism. The major themes involve the current productivity slowdown, waning competition, the role of globalization, rising inequality, and climate change. Through this exercise, I emphasize that there are some global trends, but there are also important national and regional differences reflecting differences in institutions and policy. In this sense, not only natural-scientific technology, but also social-scientific technology—that is, governance, policy, and institutions—matter. Then, I shall argue that Smith can teach us in five ways. First, Smith conceives a truly inclusive capitalism, as he takes income distribution into account when he argues for the desirability of economic development. For Smith, economic development is desirable when the well-being of the majority of people is improved.Footnote 18 Second, inclusive capitalism requires knowledge formation and sharing of knowledge among people. Smith’s inclusive capitalism is based on the division of labor principle, with markets (or broad exchange) fostering the division of labor as well as policy measures alleviating negative side effects of the division of labor.Footnote 19 Third, the expansion of exchange and trade has beneficial effects, but we should be aware of its distributional consequences. Fourth, institutions matter. Markets are the most fundamental institution, but it is imperative to preserve competition, especially free entry, in markets. Fifth, proper law and institutions—the “system of natural liberty” (WN IV.ix.51)—are essential to a well-functioning market economy. However, the “system of natural liberty” is not automatically achieved. Policy and institutions are history-dependent; therefore, history matters. We should be reminded here of the “relatively cautious sense of progress” of Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, including Smith.Footnote 20

The essay is organized as follows. The next section surveys recent challenges of capitalism. Then, I turn to how Smith could answer those challenges regarding the future of capitalism. The last section offers some concluding thoughts.

A comparative and historical tour of challenges in the spirit of Montesquieu, Hume, and Smith

Capitalism or not, the world faces several challenges. I lay out five challenges: (1) productivity slowdown, (2) waning globalization, (3) growing inequality, (4) rising corporate market power, and (5) climate change.Footnote 21

Challenge 1: Productivity slowdown

All over the world, productivity is still growing, but its speed has been slowing down. As Robert Gordon argues, one may say that the 1950s and 1960s were the exception in terms of productivity growth, and today is closer to the historical normal.Footnote 22 Gordon shows that growth in total factor productivity in the United States recorded a very high growth rate in the 1950s, but not so in recent decades. For example, even during what was hailed as the information technology revolution, the productivity growth rate was not that high. Also, productivity slowdown is prevalent in other advanced economies, including Canada, Japan, Germany, France, United Kingdom, and Italy.

What determines productivity? The question still has no clear answer; in fact, the whole history of economics has been trying to answer this question. Gordon thinks that productivity gains during the 1950s and 1960s was driven by a cluster of innovations, further arguing that “Secular Stagnation” should be caused by supply side factors.

Related to the question of productivity, what about the rise of robots and artificial intelligence (AI)? Currently, there is no definitive consensus of their impact on productivity and employment. Some say, “Productivity will go up,”Footnote 23 while others say, “It won’t go up that much.”Footnote 24 Regarding the impact on employment, some say, “AI will cause job losses, and 90 percent of the people who are there now will lose their jobs,”Footnote 25 while others say that it will not, so the assessment is very divided.

However, the most recent studies point to more positive impacts of AI on productivity and employment. For example, Erik Brynjolfsson and colleagues show that generative AI increases productivity, worker retention, and customer satisfaction and decreases inequality,Footnote 26 while Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang show that ChatGPT substantially raises average productivity and decreases inequality between workers.Footnote 27 In a similar vein, David Autor argues that AI as a tool for facilitating decision-making could enhance the productivity of lower-skilled workers. Thus, it could reduce skill gaps and inequality between higher-skilled workers and lower-skilled workers.Footnote 28

Without a consensus at hand, there is nevertheless an interesting interaction between globalization and the rise of robots and AI. With today’s globalization, products that used to be made entirely in Japan can now be manufactured at local production bases by taking overseas the design specifications for what is to be made. In the case of services, it is now possible to use overseas services without having to leave Japan. What used to be done with domestic services in the past can now be done with overseas services via the Internet or through teleconferencing. In this context, it is possible to predict that as robots and AI evolve, coupled with increasing globalization, the demand for certain types of services in Japan may decrease.Footnote 29

Challenge 2: Waning globalization

Globalization has been one of the focal points of criticism against current capitalism. Global volumes of trade in goods and services and the stock of financial assets relative to nominal gross domestic product (GDP) have become flat after the GFC. This has sometimes been cited as a sign of the end of globalization or the crisis thereof.

However, there is a change in the composition of trade. While trade in goods is indeed stagnating, trade in services is increasing. Richard Baldwin further predicts that trade in intermediate services will continue to grow.Footnote 30 In this sense, news of the death of globalization may be exaggerated.

Taking a broader historical view, first, globalization or freer trade has been the driving force behind improved living conditions in the world, and it has contributed to economic growth.Footnote 31 It also has achieved lengthening of average life expectancy and the reduction of the number of people living under the poverty line, enriching India, China, and African countries.

Second, however, globalization has ebbed and flowed depending on the race between technology, policy, and institutions.Footnote 32 Globalization progressed when communication and transportation technologies improved,Footnote 33 or institutions such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) functioned with eased geopolitical tensions; it receded when geopolitical tensions such as world wars rose; economic crises such as the Great Depression occurred; or national security concerns, protectionism, and trade wars erupted.

Nevertheless, the fruits of progress may not be shared evenly within or across countries. Therefore, third, globalization has distributional consequences. The most famous example is the “China Shock”Footnote 34 where U.S. manufacturing jobs were “lost” due to imports from China, although the authors note that there are still net benefits from trade with China. Another example is the “New Trilemma.” Dani Rodrik proposes the political trilemma of the world economy, according to which deepening economic integration, nation-states, and democratic politics cannot all be established at the same time.Footnote 35 According to this view, the current halt in globalization can be interpreted as a movement to defend the nation-state and democratic politics at the expense of deeper economic integration since the GFC.

Challenge 3: Rising inequality

Thomas Piketty’s pioneering workFootnote 36 gives us the impression that inequality in income and wealth has been rising all over the world since the late 1970s. However, inequality trends vary across countries. The United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Italy show an upward U-shaped trend, while Japan, Sweden, France, Spain, and the Netherlands show a stable flat trend; Piketty himself as well as Joe Hasell have shown that result.Footnote 37

Also, there can be pre-tax income inequality, while several redistribution institutions and policies are in place. Once those are considered, income inequality is less than pre-tax data shows. Hasell eloquently summarizes the implications of inequality studies:

The differences in these trends tell us something important: high and rising inequality is not an inevitability; it’s something that individual countries can influence. A universal trend of increasing inequality would support the idea that inequality is completely determined by global economic forces like technological progress, globalization, or capitalism. The very different trends we see among countries exposed to these same forces suggest that national institutions, politics, and policy matter a lot.Footnote 38

Second, causes of this widening inequality are also the subject of many theories and are difficult to determine. For example, Piketty famously points out that it is because the rate of return on wealth (r) exceeds the rate of economic growth (g).Footnote 39 Other arguments include, for example, that it is because of declining labor union organization rates or changes in the tax system.

Historically, the relationship between (r) and (g) varies. According to Jordà and colleagues, the relationship that (r) is greater than (g) holds most of time, but not always.Footnote 40 Especially when a major war broke out, (r) is smaller than (g). This implies that forces for increased inequality are also a product of history.

Third, in terms of global inequality, a graph called the “Elephant Chart” has become famous in recent years.Footnote 41 It shows the income growth of the world’s poorest to richest people on the horizontal axis from left to right and plots the growth of income for each group on the graph. The middle part of the elephant’s nose is almost zero, which is interpreted to mean that the people in this area are the ones losing the most or gaining the least. It was interpreted that the working class and middle class in developed countries were being undercut by the very rich people in developed countries who were at the tip of the elephant’s nose, and the newly rich people in emerging countries such as China, who were getting richer at the head of the elephant.

However, the original elephant curve needs a major correction, as it now does not look like an elephant at all. Branko Milanovic, one of the originators of the curve, re-estimates and revises the curve.Footnote 42 The more the lower-income group benefits, the more the global “median” or middle class grows, whereas the top income group, especially the top 1 percent, is experiencing slower growth: the world is becoming less unequal. This can be attributed to a slowdown in the West after the GFC, as well as the continued growth of China, India, and other Asian countries.

Challenge 4: The rise of big-tech corporations and waning competition

Globalization has led to the rise of global big-tech companies. The first thing to point out is the role of intangible assets. Today, big tech companies, the so-called “GAFAMs” (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft) run their businesses using intangibles.Footnote 43 In other words, intellectual property rights, algorithms, and data are becoming increasingly important. They have different properties from ordinary tangible assets. With respect to data, it does not degrade regardless of how many times it is used (nonrivalry); the more data you have, the more of an advantage you have (economies of scale). The more data a company has on its customers, presumably the more of an overwhelming advantage it will have over companies that have less data.

This would lead to what economists call a natural monopoly or oligopoly. For example, when people search the Internet, they tend to use a particular company’s search engine. This is thought to be the reason, if not the only reason, for ongoing decline in the level of competition in developed countries.

Second, it has been noted that as oligopoly increases and the degree of competition decreases, there is an inverse U-shaped relationship where investment and innovation initially increase but they eventually decrease.Footnote 44 Joseph Schumpeter once argued that the greater oligopolistic market power is, the more innovation is promoted.Footnote 45 However, recent empirical studies show that this is true only up to a certain point, after which the relationship declines in innovation. This is also regarded as one of the reasons for the decline in productivity discussed in Challenge 1. In other words, productivity is declining because firms are investing less and innovation is slowing down.

Looking at the advance of oligopoly in terms of the markup of firms, which is its proxy variable (that expresses the degree of oligopoly), markups have risen significantly in developed economies, especially in the United States. The degree of oligopoly of Japanese firms also differs considerably from that of foreign firms. On the other hand, in emerging economies, the trend toward oligopoly has not yet been observed. This supports the view that big tech companies may be creating an oligopoly in the economy. As the markup increases, the investment rate increases up to a certain point, but as the markup increases beyond that point, the investment rate tends to decrease.

However, there are debates as to the origin of waning competition in the U.S. economy. Thomas Philippon points out that GAFAMs owe their existence and rise to the U.S. Department of Justice’s decision to prevent “Microsoft from monopolizing the Internet in the late 1990s.”Footnote 46 He summarizes the “evolution of economics and politics in the United States over the past twenty years”:

First, US markets have become less competitive: concentration is high in many industries, leaders are entrenched, and their profit rates are excessive. Second, this lack of competition has hurt US consumers and workers: it has led to higher prices, lower investment, and lower productivity growth. Third, and contrary to common wisdom, the main explanation is political, not technological: I have traced the decrease in competition to increasing barriers to entry and weak antitrust enforcement, sustained by heavy lobbying and campaign contributions.Footnote 47

On the other hand, although markup has been rising in advanced economies, there are important national and regional differences, reflecting differences in competition policy and institutions. Philippon compares Europe and the United States on competition policy, arguing that the current “EU [European Union] competition policy has become stronger than US competition policy, and EU consumers are better off for it.” Ironically, the EU previously was not advanced in competition policy, but it learned from the United States when the EU refined the single market. He concludes: “I was surprised by the power and persistence of institutions beyond their original intent.”Footnote 48

Challenge 5: Climate change

Some economists say that climate change is our most pressing existential threat.Footnote 49 Noah Smith succinctly summarizes key facts about climate change.Footnote 50

First, the planet is getting warmer. It is not yet certain that global temperature is coming down to the target level. Second, because climate change has been caused by human activities, it can be changed on principle. As Bill Gates and others stress, it is imperative to have technological breakthroughs to achieve a net-zero CO2-emission economy.Footnote 51 New cleaner energy technologies to replace fossil fuels such as solar, wind, and batteries have been advancing. Also, policies tackling climate change began around the 2010s. As a result, global CO2 emissions have slowed down since then, and even the current policy would stabilize global temperature with an increase of around 2.6 degrees Celsius. Current policy falls short of the goal of 1.7 degrees Celsius with zero-emission pledges, which leaves a 0.9 degree Celsius discrepancy.

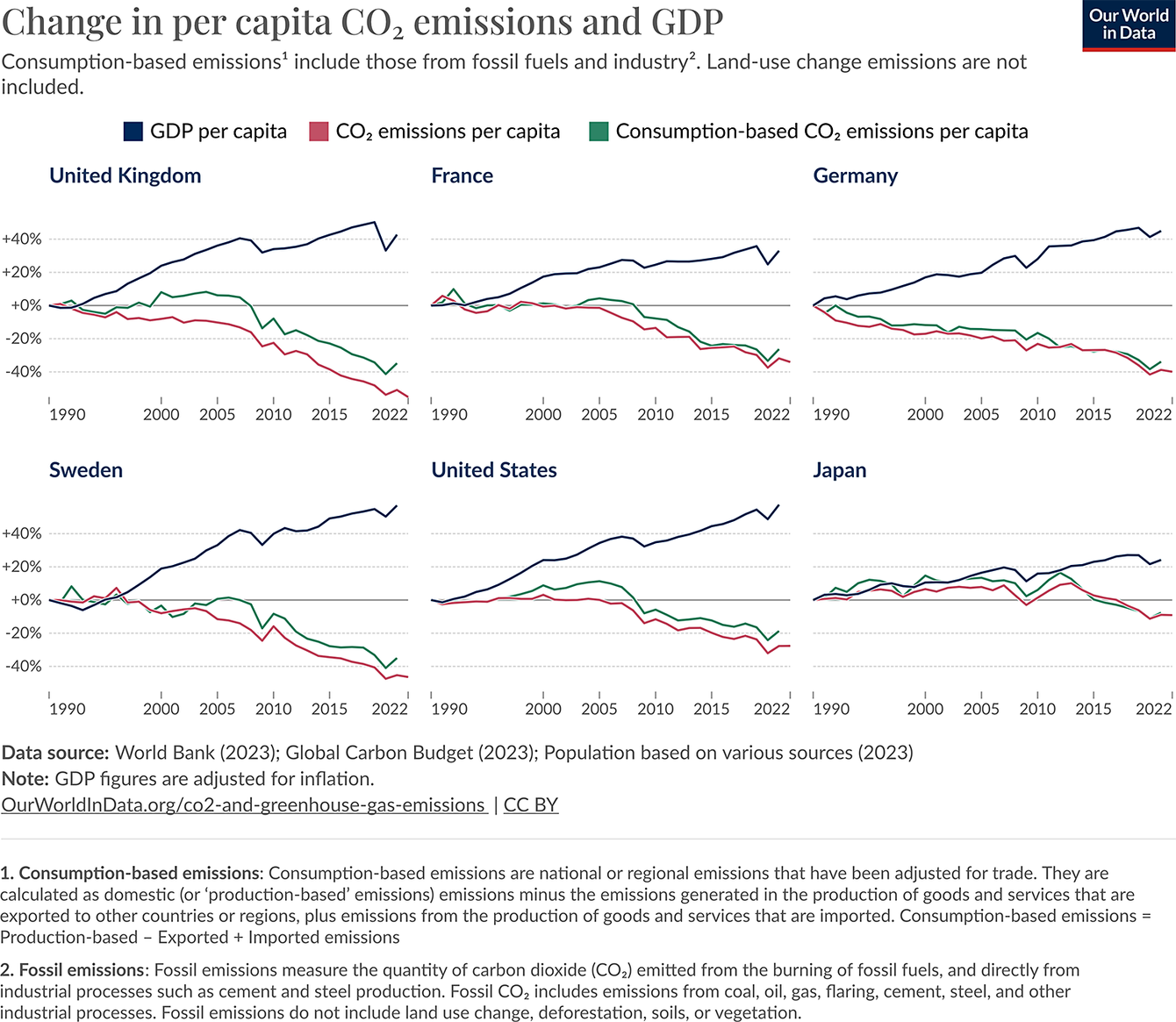

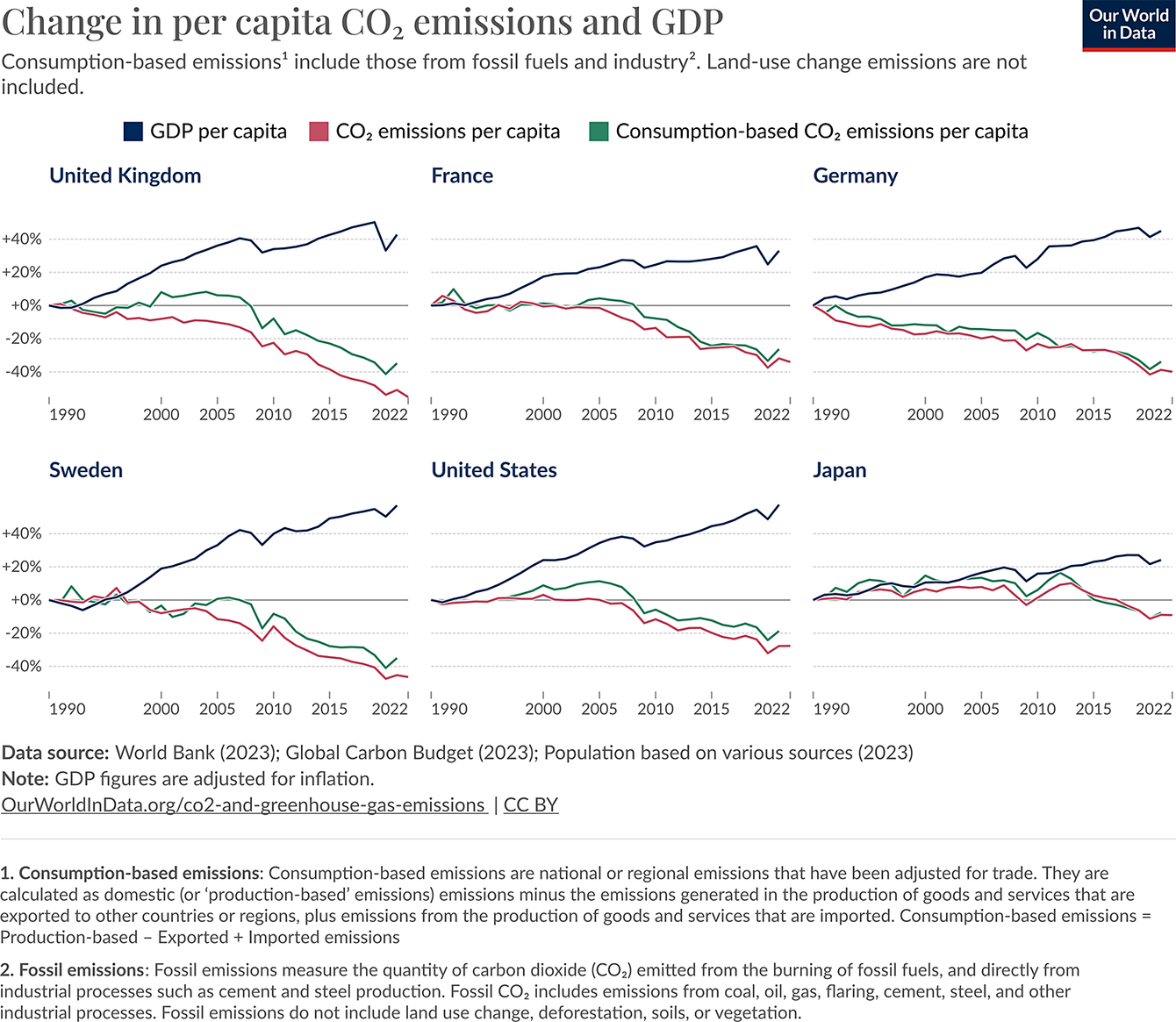

Third, there are differences in regional responses. Advanced economies are reducing CO2 emissions, while other regions—especially China and India—are increasing CO2 emissions. Fourth, advanced economies are succeeding in decoupling CO2 emissions from economic growth by reducing CO2 emissions while maintaining economic growth. As consumption-based CO2 emissions per capita show (see Figure 2), decoupling is not due to exporting CO2-emissions industries to developing economies.

Figure 2. CO2 emissions are being decoupled from economic growth.Footnote 52

These challenges are not only about technology, but also about institutions and policy. Behind growing criticism of capitalism is the fear of what will happen to people’s jobs when globalization, AI, and robots evolve. Regardless of whether jobs are actually disappearing, the fact that such fears exist is itself amplifying anxiety. Whether or not globalization is really making people poorer, the fact that globalization is progressing is associated with the anxiety that people have. When there is such anxiety, it is easy for various “isms” to spring up, one of which is populism.Footnote 53

Populism has many aspects. One is opposition to an old establishment or elite class, which forms the core of populism. Because the establishment and elites are the architects of today’s society, they become the targets to which one can voice one’s concerns that society is not doing well. Populism has a very dangerous element because if it takes the wrong form, it can become a force that destroys the social order itself. However, it is not without its positive elements in the sense that it can point out current problems and serve as a driving force to change the status quo. However, if it becomes xenophobic, anti-scientific, and anti-knowledge, it will impede progress.

Perhaps anxiety about the future is caused not only by the GFC, but it is also influenced by various underlying changes. For example, technological changes that are occurring now are creating oligopolies in the form of changes in market structure. This slows the growth of productivity and lowers the rate of economic growth. Stagnant economic growth could also affect income inequality. According to Piketty, a decline in the rate of economic growth will lead to an increase in income inequality. Therefore, what matters in understanding these challenges is not only technology, but also policy and institutions. The following are what we could learn about current challenges:

-

1. The productivity slowdown is a complicated issue, but there is some element of institution and policy. To the extent that the current productivity slowdown is related to weakened investment and competition, which in turn is caused by political influences, the productivity slowdown is a social phenomenon.Footnote 54 Even with the advent of AI and robots, there are promising signs that they are not reducing worker employment.

-

2. With respect to globalization, trade in goods is stagnating, while trade in services continues increasing. This is despite decoupling or derisking as well as recent growing tensions in U.S.-China trade.

-

3. Inequality in income and wealth is not uniform for all countries, but varies across countries, reflecting differences in redistributive policy and institutions.Footnote 55 To the extent that the difference between (r) and (g) is driving inequality, changing (r) and (g) will affect inequality.

-

4. The waning of competition and increased concentration has been reducing investment. To the extent that waning of competition is driven by restriction of free entry by political influences, changing restriction of free entry will affect competition.Footnote 56

-

5. Climate change is posing a great existential threat to humanity. Even on this front, we have been making progress in reducing CO2 emissions due to both technological and institutional changes.Footnote 57

In addition to this list, we could also argue that austerity policies after the GFC and the Great Recession exacerbated the damage to economies and contributed to the rise of populism. In this sense, we should focus on social-scientific technology, that is, the technology of governance, institutions, and policy.

The Smithian vision for the future of capitalism

Despite many challenges, capitalism or the current economic system has delivered a great deal of progress.Footnote 58 Overall, humankind has progressed. Although there are still countries where average life expectancy is lower, the average life expectancy has gotten longer. Also, the number of people under extreme poverty, hunger, or without literacy has decreased considerably within the past twenty years, mainly due to economic development of developing countries such as China and India. The world is getting richer and richer. This Great Enrichment is a Smithian achievement. Although inequality across countries persists, and it is even increasing for childhood survival and clean air, the overall trend is toward reduced inequality.Footnote 59

What contributed to these remarkable achievements? Herbert Simon says that “humans are social animals who solves [sic] problems and use skills to solve them.”Footnote 60 To perceive problems and to use skills to solve them require knowledge. First, recognizing the role of knowledge itself is part of and the driving force behind human progress, which includes the rise of the Enlightenment and scientific thinking.Footnote 61 But this does not mean that progress is automatic. Second, it is important to note that scientific and technological knowledge entails not only natural-scientific and engineering technology, but also social-scientific and social-engineering knowledge, that is, policy and institutions. Third, globalization has been playing a vital role in diffusing and disseminating knowledge. When one thinks of globalization, one might imagine international movements of goods and services, capital, and people, but that of knowledge is a far more important part of globalization.

In this light, the direction in which to upgrade capitalism is also clear. Economic growth is still desirable. We should continue to maintain and improve the system of a competitive market economy that improves people’s lives. Throughout history, no country has been able to maintain prosperity for an extended period without maintaining markets and trade. However, a market economy requires some form of regulation and institutions, and care for those who have fallen out of the market is not automatically achieved. In this regard, both regulation and redistribution are necessary.

Humankind has achieved remarkable progress, but that progress has not been automatic. Rather, it has been achieved through the history of people struggling to work on challenges and problems at hand. Against this backdrop, I shall focus on five of Smith’s insights that could teach us about the future of capitalism: the desirability of growth; the drivers of growth; the role of exchange, trade, and markets; the importance of institutions; and dependency of institutions on history.Footnote 62

Smith’s human nature assumptions

At the heart of Smith’s work are his assumptions about egalitarian human nature. First, Smith focuses on human beings as an exchanging animal distinct from other animals: the “propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another” is “common to all men, and to be found in no other race of animals” (WN I.ii.1–2).Footnote 63 His life-long interest in communication is well-known.Footnote 64 Exchange requires language and a notion of contract; Smith suggests that this propensity is “the necessary consequence of the faculties of reason and speech” (WN I.ii.2)Footnote 65

Second, Smith stresses the difference between people in natural and cultivated abilitiesFootnote 66 with his famous reference to the difference between “a philosopher and a common street porter”:

The difference of natural talents in different men is, in reality, much less than we are aware of; and the very different genius which appears to distinguish men of different professions, when grown up to maturity, is not upon many occasions so much the cause, as the effect of the division of labour. The difference between the most dissimilar characters, between a philosopher and a common street porter, for example, seems to arise not so much from nature, as from habit, custom, and education. (WN I.ii.4)

Third, Smith admits a wide variety of human motives other than self-interest. Although Smith assigns the “desire of bettering our condition” (WN II.iii.28) a dominant role among human motives, arguing that it is “uniform, constant, and uninterrupted” (WN II.iii.31), he juxtaposes it with “passions,” which are a wide variety of motives, such as overconfidence, pride, vanity, love for dominance and control, envy, and rapacity. Indeed, the running theme of Smith and most of his contemporaries is consideration of the circumstances in which “passions” do not coincide with real “interests.”Footnote 67

First, economic growth is good, desirable, and just, as long as it contributes to the happiness of the majority of the people. Provided that economic growth benefits the lower ranks of the people by raising their living standard through the increased natural rate of wage, Smith asks himself this question:

Is this improvement in the circumstances of the lower ranks of the people to be regarded as an advantage or as an inconveniency to the society? The answer seems at first sight abundantly plain. Servants, labourers and workmen of different kinds, make up the far greater part of every great political society. But what improves the circumstances of the greater part can never be regarded as an inconveniency to the whole. No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable. It is but equity, besides, that they who feed, cloath and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labour as to be themselves tolerably well fed, cloathed and lodged. (WN I.viii.36)

It is important that Smith accounts for distributional concerns when he argues for the desirability of economic growth. It is not only the majority (the “far greater part of the members”) but also the lower-income group (the “lower ranks of the people”) to which policymakers should pay attention. Also, Smith believes that focusing on those groups of people is just. In this regard, policies that benefit the majority of the people should be preferred.Footnote 68

Economic growth contributes to the happiness of the people, especially for the “labouring poor,” although he thinks growth will raise the happiness of “all the different orders of the society”:

It deserves to be remarked, perhaps, that it is in the progressive state, while the society is advancing to the further acquisition, rather than when it has acquired its full complement of riches, that the condition of the labouring poor, of the great body of the people, seems to be the happiest and the most comfortable. It is hard in the stationary, and miserable in the declining state. The progressive state is in reality the chearful and the hearty state to all the different orders of the society. The stationary is dull; the declining, melancholy. (WN I.viii.43)

The relationship between economic growth and happiness is contentious. It is possible that economic and material wealth does not bring happiness, although loss of income through unemployment and poverty does affect people’s well-being. According to Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, subjective well-being has two aspects: emotional well-being (the frequency and intensity of stress, anger, and sadness felt in daily life) and evaluation of one’s life.Footnote 69 The former increases with income up to a certain level, but does not change beyond that, while the latter continues to increase with income. They conclude that money can buy an evaluation of life and a certain level of satisfaction, but it cannot buy emotional well-being. However, a recent study shows that “[h]appiness increases steadily with log(income) among happier people, and even accelerates in the happiest group,” but there is a flattening pattern among the least happy 20 percent of the population, so the positive relationship between economic growth and happiness still holds for the majority of the people.Footnote 70

Second, knowledge and technology drive economic growth, but they are endogenously and socially created. As is discussed in Challenge 3 above, productivity is technologically and socially determined.Footnote 71 This follows from Smith’s human nature assumption that human beings are learners. He locates the division of labor at the center of endogenous generation of knowledge. The division of labor is the connecting principle of Smith’s work, and it is the foundation of a society. When we work in one occupation, we work in the occupation created by the division of labor. The division of labor also creates new occupations: “The division of labour, however, so far as it can be introduced, occasions, in every art, a proportionable increase of the productive powers of labour. The separation of different trades and employments from one another, seems to have taken place, in consequence of this advantage” (WN I.i.4). The division of labor presupposes mutual yet unconscious cooperation among people:

[I]f we examine, I say, all these things, and consider what a variety of labour is employed about each of them, we shall be sensible that without the assistance and co-operation of many thousands, the very meanest person in a civilized country could not be provided, even according to, what we very falsely imagine, the easy and simple manner in which he is commonly accommodated. (WN I.i.11)

The egalitarian assumption in human capacity entails the significance of knowledge acquired through “habit, custom, and education” (WN I.ii.4). More specifically, Smith comprehends the sources of knowledge in five ways: skill formation of the working population, human capital accumulation, the rise of invention and innovation at the workplace, the progress of science, and technology transfer.

The division of labor entails both the division of labor within firms and that within society,Footnote 72 which allows Smith to recognize ever-growing types of new occupations. Smith refers to skill formation among the workers (the “increase of dexterity in every particular workman”) as the first benefit of the division of labor (WN I.i.5–6), through which human capital also accumulates.Footnote 73 Technology transfer is also endogenized through capital accumulation: “[A] nation is not always in a condition to imitate and copy the inventions and improvements of its more wealthy neighbors; the application of these frequently requiring a stock with which it is not furnished.”Footnote 74

The progress of science is also endogenized in that the security and material foundation of a society allows people to be curious. According to Smith, the rule of law is crucial for the development of knowledge. This continues a Humean theme, yet, while David Hume considers that the steps from security through curiosity to knowledge are subject to uncertainty, Smith goes further than Hume in relating security to knowledge more firmly:

[W]hen law has established order and security, and subsistence ceases to be precarious, the curiosity of mankind is increased, and their fears are diminished. The leisure which they then enjoy renders them more attentive to the appearances of nature, more observant of her smallest irregularities, and more desirous to know what is the chain which links them all together.Footnote 75

The key to inclusive capitalism lies in the fact that the natural wage would increase during economic growth, a feature of Smith’s growth model as distinct from the post–1815 growth model based on diminishing returns.Footnote 76 Inclusiveness is closely related to a sense of fairness, as there is a growing sense among the public that “[c]urrent competition seems unfair to those who are affected,”Footnote 77 when they feel their wages are stagnant. From the Smithian point of view, it is crucial that inclusiveness be accompanied by growth in wages.

Potentially, this knowledge-based growth has no limit, because there are no diminishing returns to knowledge. Baldwin notes that “human and physical capital face diminishing returns, while knowledge capital does not,” and he further speculates that “[t]he reason is unclear, but one guess [sic] that it reflects the fact that human ignorance is infinite despite millenniums [sic] of knowledge creation.”Footnote 78 Despite prevalent pessimism about productivity growth in the future, Smith clearly sides with optimists.

Third, the expansion of exchange and trade is good, but we should be aware of its distributional consequences. This follows directly from Smith’s human nature assumption that humans are exchanging animals who have, as already noted, “the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.” Markets also serve as knowledge-enhancing and disciplinary institutions. As the Smithian dictum that the “division of labor is limited by the extent of the market” suggests, markets enlarge the scale and scope of the division of labor, which in turn facilitates knowledge of the economy.

Globalization has been associated with economic growth not only in correlation but also in causation. Smith thinks of globalization in terms of a “more extensive foreign trade,” relating it to improvement in the productivity of its industry:

A more extensive foreign trade, however, which to this great home market added the foreign market of all the rest of the world; especially if any considerable part of this trade was carried on in Chinese ships; could scarce fail to increase very much the manufactures of China, and to improve very much the productive powers of its manufacturing industry. By a more extensive navigation, the Chinese would naturally learn the art of using and constructing themselves all the different machines made use of in other countries, as well as the other improvements of art and industry which are practised in all the different parts of the world. (WN IV.ix.41)

His argument is based on technology transfer induced by foreign trade, which resembles Hume’s view of this issue.

Smith is also aware of the distributional consequences of trade:

The undertaker of a great manufacture who, by the home markets being suddenly laid open to the competition of foreigners, should be obliged to abandon his trade, would no doubt suffer very considerably. That part of his capital which had usually been employed in purchasing materials and in paying his workmen, might, without much difficulty, perhaps, find another employment. But that part of it which was fixed in workhouses, and in the instruments of trade, could scarce be disposed of without considerable loss. (WN IV.ii.44)

Ultimately, or in the longer run, there may be an equilibrium in which capital can be reallocated to other areas, but Smith stresses that adjustment costs due to trade could be significant. Therefore, he proposes a gradual transition for opening up the domestic market:

The equitable regard, therefore, to his interest requires that changes of this kind should never be introduced suddenly, but slowly, gradually, and after a very long warning. The legislature, were it possible that its deliberations could be always directed, not by the clamorous importunity of partial interests, but by an extensive view of the general good, ought upon this very account, perhaps, to be particularly careful neither to establish any new monopolies of this kind, nor to extend further those which are already established. Every such regulation introduces some degree of real disorder into the constitution of the state, which it will be difficult afterwards to cure without occasioning another disorder. (WN IV.ii.44)

It should be also noted that Smith is concerned with the equity or fairness of such a policy. He is also concerned with the competence of policymakers to make an appropriate decision, a feature I shall discuss below.

Fourth, institutions matter. Markets are the most fundamental institutions, but it is imperative to preserve competition, especially free entry, in markets. Given Smith’s assumptions of humans as exchanging animals, “opulence,” or economic development, depends on how people organize themselves via institutions. Smith regards markets as the fundamental institutions: they are knowledge-enhancing and disciplinary. He says that the “division of labour is limited by the extent of the market.” Markets enlarge the scale and scope of the division of labor, which in turn facilitates knowledge of the economy. It is also disciplinary because Smith thinks of what we would call corporate governance in terms of interaction between corporations and markets.

A case in point is Smith’s analysis of joint-stock companies, exemplified by the East India Company. He stresses that joint-stock companies are inherently inefficient due to principal-agent problems and its status as monopoly: “The directors of such companies, however, being the managers rather of other people’s money than of their own, it cannot well be expected, that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private copartnery frequently watch over their own” (WN V.i.e.18).Footnote 79 He continues by saying that because “[n]egligence and profusion … must always prevail, more or less, in the management of the affairs of such a company,” joint-stock companies for foreign trade “have seldom been able to maintain the competition against private adventurers … without an exclusive privilege.”

The above example shows that Smith is not a defender of capitalists, but of competitive market capitalism. Smith is decidedly pro-market, but not pro-business, and his objective is to “save capitalism from the capitalists.”Footnote 80 After all, Smith attacks the system of commerce supported by merchants and manufacturers:

To widen the market and to narrow the competition, is always the interest of the dealers. To widen the market may frequently be agreeable enough to the interest of the publick; but to narrow the competition must always be against it, and can serve only to enable the dealers, by raising their profits above what they naturally would be, to levy, for their own benefit, an absurd tax upon the rest of their fellow-citizens. The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order, ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men, whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the publick, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the publick, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it. (WN I.xi.p.10)

Fifth, proper law and institutions—the “system of natural liberty”—are essential to a well-functioning market economy. However, the “system of natural liberty” is not automatically achieved. History matters. Policy and institutions are history-dependent. Smith states clearly that his ideal is to establish the “simple system of natural liberty”:

All systems either of preference or of restraint, therefore, being thus completely taken away, the obvious and simple system of natural liberty establishes itself of its own accord. Every man, as long as he does not violate the laws of justice, is left perfectly free to pursue his own interest his own way, and to bring both his industry and capital into competition with those of any other man, or order of men. The sovereign is completely discharged from a duty, in the attempting to perform which he must always be exposed to innumerable delusions, and for the proper performance of which no human wisdom or knowledge could ever be sufficient; the duty of superintending the industry of private people, and of directing it towards the employments most suitable to the interest of the society. (WN IV.ix.51)

The system of natural liberty, however, is not a system without regulations or the government: “[T]hose exertions of the natural liberty of a few individuals, which might endanger the security of the whole society, are, and ought to be, restrained by the laws of all governments; of the most free, as well as of the most despotical” (WN II.ii.94). For example, Smith supports regulation of banking,Footnote 81 and he continues by saying that “[t]he obligation of building party walls, in order to prevent the communication of fire, is a violation of natural liberty, exactly of the same kind with the regulations of the banking trade which are here proposed.” In addition, he justifies patents based on the nature of knowledge as a public good (WN V.i.e.30). In light of the 1763 financial crisis, Smith describes what is now considered as the lender of last resort function of the central bank conducted by the Bank of England. He regards the Bank of England as acting “not only as an ordinary bank, but as a great engine of state” (WN II.ii.85).Footnote 82 A free and competitive market system works best when it is supported by a proper legal and institutional structure. Therefore, Smith is not an advocate of “laissez faire.”Footnote 83

It is well known that Smith argues for a limited government under the system of natural liberty: “According to the system of natural liberty, the sovereign has only three duties to attend to; three duties of great importance, indeed, but plain and intelligible to common understandings” (WN IV.ix.51). These three duties are (1) defense of the country, (2) administration of justice, and (3) maintenance of certain public works. They have three characteristics in common. First, they are focused on the effective establishment of property rights. Smith famously says that “defence, however, is of much more importance than opulence” (WN IV. ii.30), underscoring the importance of national security as fundamental for securing property rights. Second, they are for the benefit of the public, not for individual interests. By focusing on three duties,

[t]he sovereign is completely discharged from a duty, in the attempting to perform which he must always be exposed to innumerable delusions, and for the proper performance of which no human wisdom or knowledge could ever be sufficient; the duty of superintending the industry of private people, and of directing it towards the employments most suitable to the interest of the society. (WN IV.ix.51)

Third, they are communication-and-knowledge-enhancing policies, with an emphasis on public infrastructure and elementary education, which are closely related to Smith’s conception of human beings.Footnote 84

A bigger question is how a proper legal and institutional structure would emerge; Smith sees that it is not automatic. Examples are plentiful. First, the most fundamental problem is the violation of property rights, the prime example of which is slavery. Second, inefficient property rights, such as primogeniture and entails, persist. Third, there are a wide variety of inefficient government regulations, such as protection and monopoly.

This leads to Smithian comparative and historical analysis, which is based on three assumptions. First, following Smithian assumptions about human nature, he conceives a race among human motives. Second, he also highlights the race between knowledge, technology, trade, institutions, policy, and politics. Third, as such, historical contingencies matter in deciding the course of development of a society.

Two prime examples of Smithian comparative and historical analysis are slavery and free trade. For Smith, slavery poses a puzzle: he believes that free labor is more efficient than forced labor, that is, slavery is inefficient, yet it persists throughout history: “We are apt to imagine that slavery is entirely abolished at this time, without considering that this is the case in only a small part of Europe; not remembering that all over Moscovy and all the eastern parts of Europe, and the whole of Asia, that is, from Bohemia to the Indian Ocean, all over Africa, and the greatest part of America, it is still in use” (LJA iii.101). He answers this puzzle by recourse to the human love of domination: “The pride of man makes him love to domineer, and nothing mortifies him so much as to be obliged to condescend to persuade his inferiors. Wherever the law allows it, and the nature of the work can afford it, therefore, he will generally prefer the service of slaves to that of freemen” (WN III.ii.10).Footnote 85 But there is a further question as to why slavery was abolished in “a small part of Europe.” For him, the answer lies in politics with the collusion of interested groups. Slavery was abolished because the king and the Church wanted to reduce the power base of the large slaveholders: “[I]t was absolutely necessary both that the authority of the king and of the clergy should be great. Where ever any one of these was wanting, slavery still continues” (LJA iii.121).

From this perspective, it follows that progress through abolishing slavery as an inefficient and unjust institution is possible but not guaranteed. Moreover, Smith is pessimistic about the prospect of abolishing slavery in the future:

It is indeed allmost impossible that it should ever be totally or generally abolished. In a republican government it will scarcely ever happen that it should be abolished. The persons who make all the laws in that country are persons who have slaves themselves. These will never make any laws mitigating their usage; whatever laws are made with regard to slaves are intended to strengthen the authority of the masters and reduce the slaves to a more absolute subjection. The profit of the masters was increased when they got greater power over their slaves. The authority of the masters over the slaves is therefore unbounded in all republican governments. (LJA iii.101–2)

It is noteworthy that Smith predicts that conflicts of vested interests become stronger as the polity becomes more democratized.

Smith is also pessimistic about the prospects of achieving free trade. Using the word “Utopia,” he declares: “To expect, indeed, that the freedom of trade should ever be entirely restored in Great Britain, is as absurd as to expect that an Oceana or Utopia should ever be established in it.” The reason is, again, politics motivated by self-interest:

Not only the prejudices of the publick, but what is much more unconquerable, the private interests of many individuals, irresistibly oppose it…. This monopoly has so much increased the number of some particular tribes of them, that, like an overgrown standing army, they have become formidable to the government, and upon many occasions intimidate the legislature. The member of parliament who supports every proposal for strengthening this monopoly, is sure to acquire not only the reputation of understanding trade, but great popularity and influence with an order of men whose numbers and wealth render them of great importance. If he opposes them, on the contrary, and still more if he has authority enough to be able to thwart them, neither the most acknowledged probity, nor the highest rank, nor the greatest publick services can protect him from the most infamous abuse and detraction, from personal insults, nor sometimes from real danger, arising from the insolent outrage of furious and disappointed monopolists. (WN IV.ii.43)

Another example involves his discussion of the interaction between cities and the countryside in British development. Two forces operate in shaping the development of institutions: the “extent of the market” and politics. The former is assumed to be a positive, progressive, and beneficial force such as the discovery of America (WN I.xi.g.25). In comparison, the latter could be either progressive or retrogressive, depending on the particular policies that the political process takes. It could secure property rights, lift regulations, or open up markets or it could maintain inefficient institutions, close or limit trade with foreign countries, establish monopoly companies, or set regulations.Footnote 86

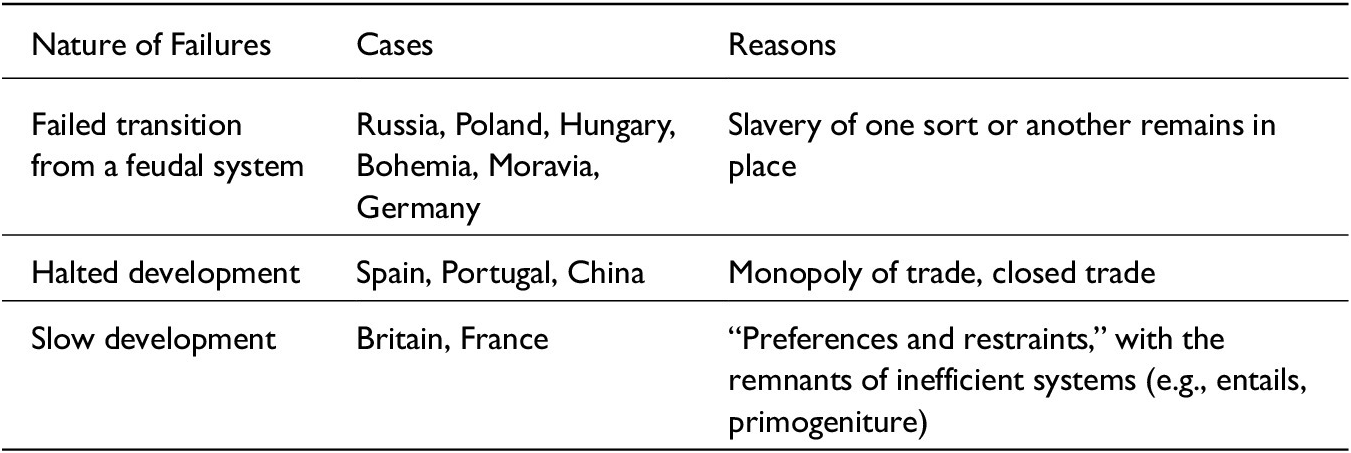

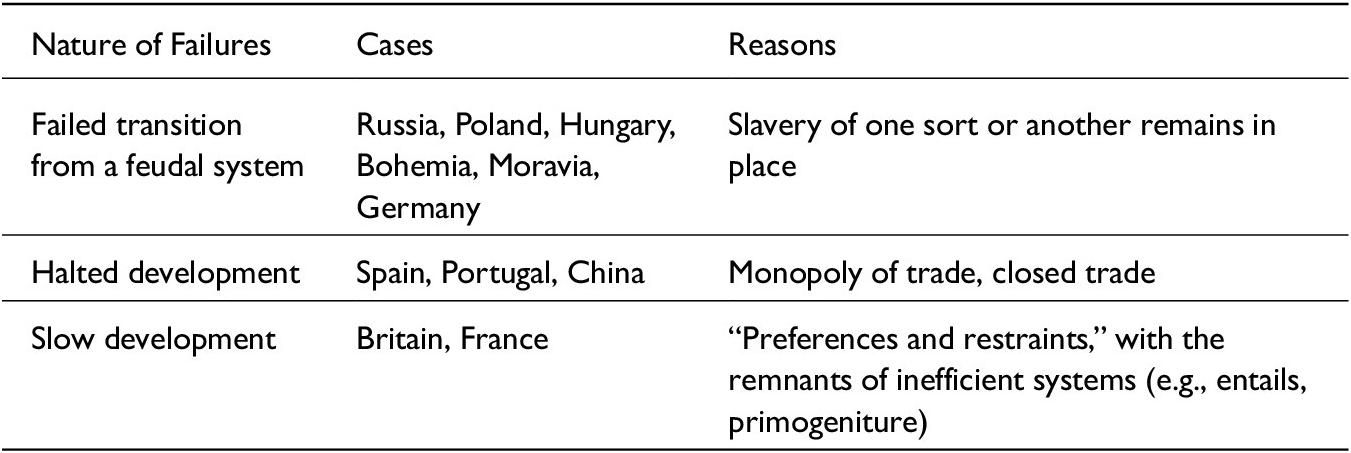

Smith thus argues that the path to “opulence” is not automatic. His comparative and historical analysis of this path can be summarized in Table 1. Three types of failure can occur on this path: failed transition from the feudal system, halted development, or slow development. Reasons for these three types vary depending on specific situations. For failed transition, slavery or its equivalent remain; for halted development, monopoly of trade and closed trade are the causes; and for slow development, “preferences and restraints” and remnants of inefficient institutions are in place.Footnote 87

Table 1. Smith’s Analysis of Failures of “Opulence”

Concluding remarks

Capitalism, or a “commercial society” in Smith’s parlance, has delivered a great deal of achievements. Yet, it now faces several serious challenges. I have argued that Smith could still offer answers to those challenges. First, capitalism should be knowledge-based, growing, market-oriented, and inclusive. Smith’s version has broader endogenous economic growth, with a pro-market but not pro-business orientation, and is concerned with distributional outcomes for most of the people. Second, although Smith believes that progress is possible, history, institutions, and policy determine the course of progress. In this sense, he takes a view that institutions are not always efficient; historical incidents and social conflict shape them.Footnote 88 Therefore, third, progress is not automatically achieved. Smith has a “relatively cautious sense of progress” common among Scottish Enlightenment thinkers.Footnote 89

We tend to forget the historical context against which Smith wrote his work, including the Wealth of Nations. That was a time when the infant mortality rate was high, universal basic education was nonexistent, the free expression of ideas was severely limited, competition was restricted, internal and external trade was distorted, and large corporations dominated much of the subcontinent. Smith’s problems are still our problems.

In his excellent book The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, Martin Wolf stresses four key objectives that a renewed capitalism should satisfy: security, opportunities, prosperity, and dignity. His five more specific goals are:

-

1. A rising, widely shared, and sustainable standard of living.

-

2. Good jobs for those who can work and are prepared to do so.

-

3. Equality of opportunity.

-

4. Security for those who need it.

-

5. Ending special privileges for the few.Footnote 90

These five goals can legitimately be called Smith’s goals as well.

I conclude this essay with three parting thoughts. The first concerns exactly what people understand by “capitalism” and “socialism.”

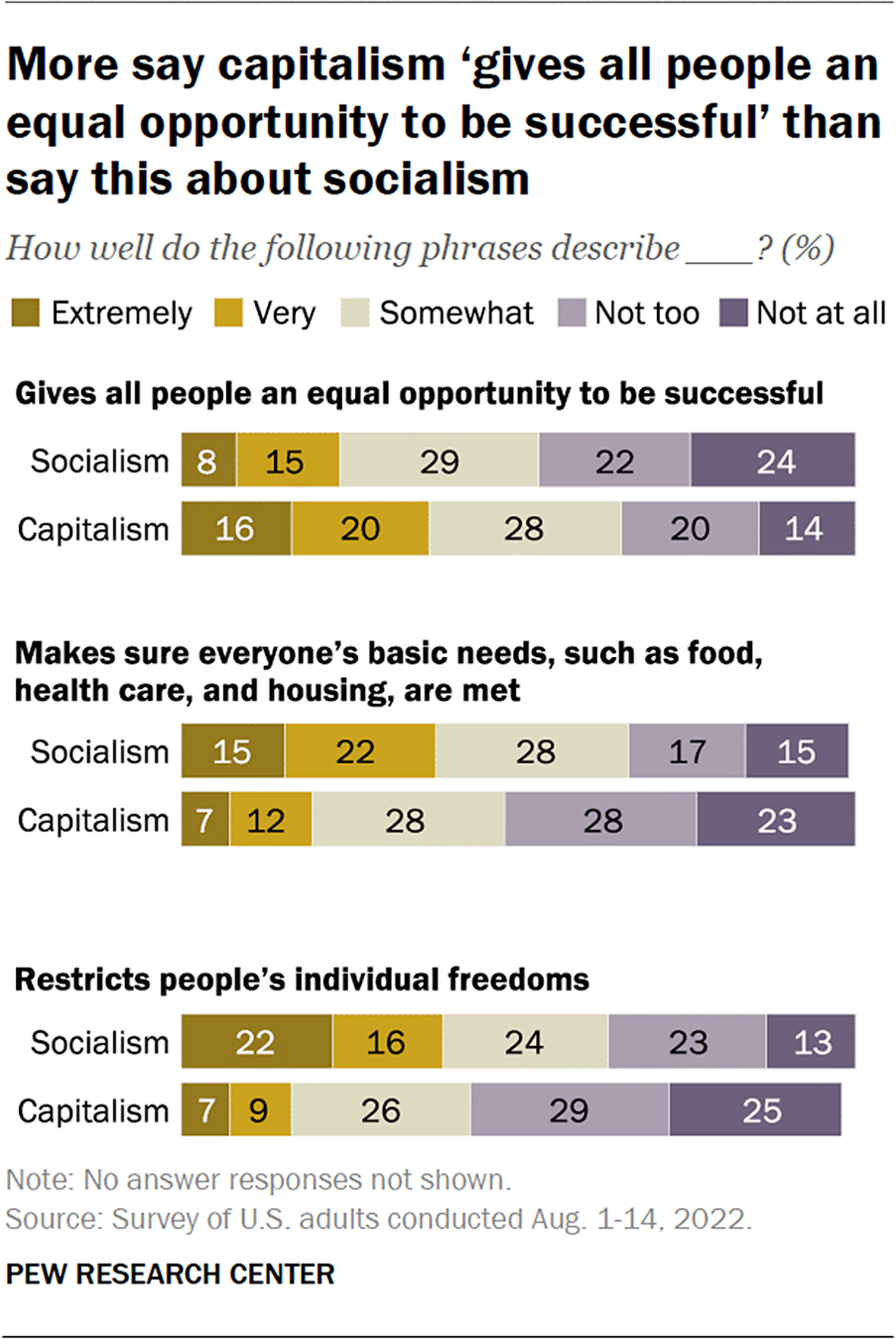

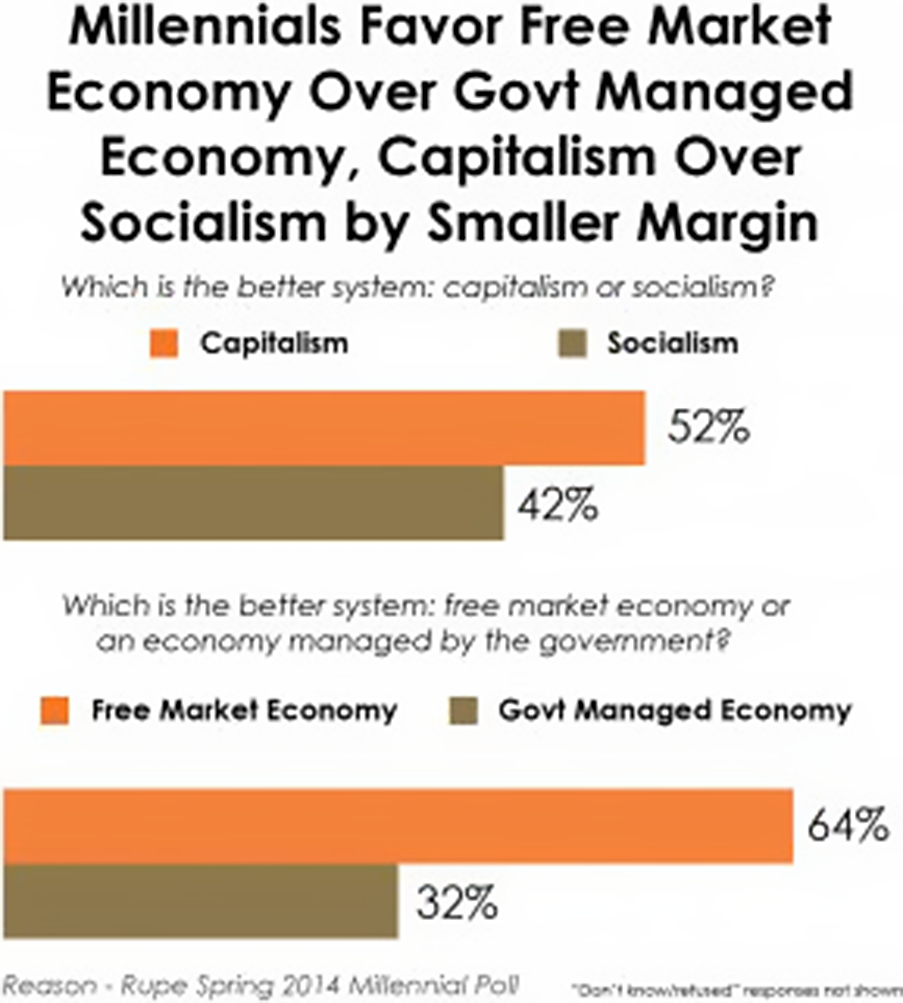

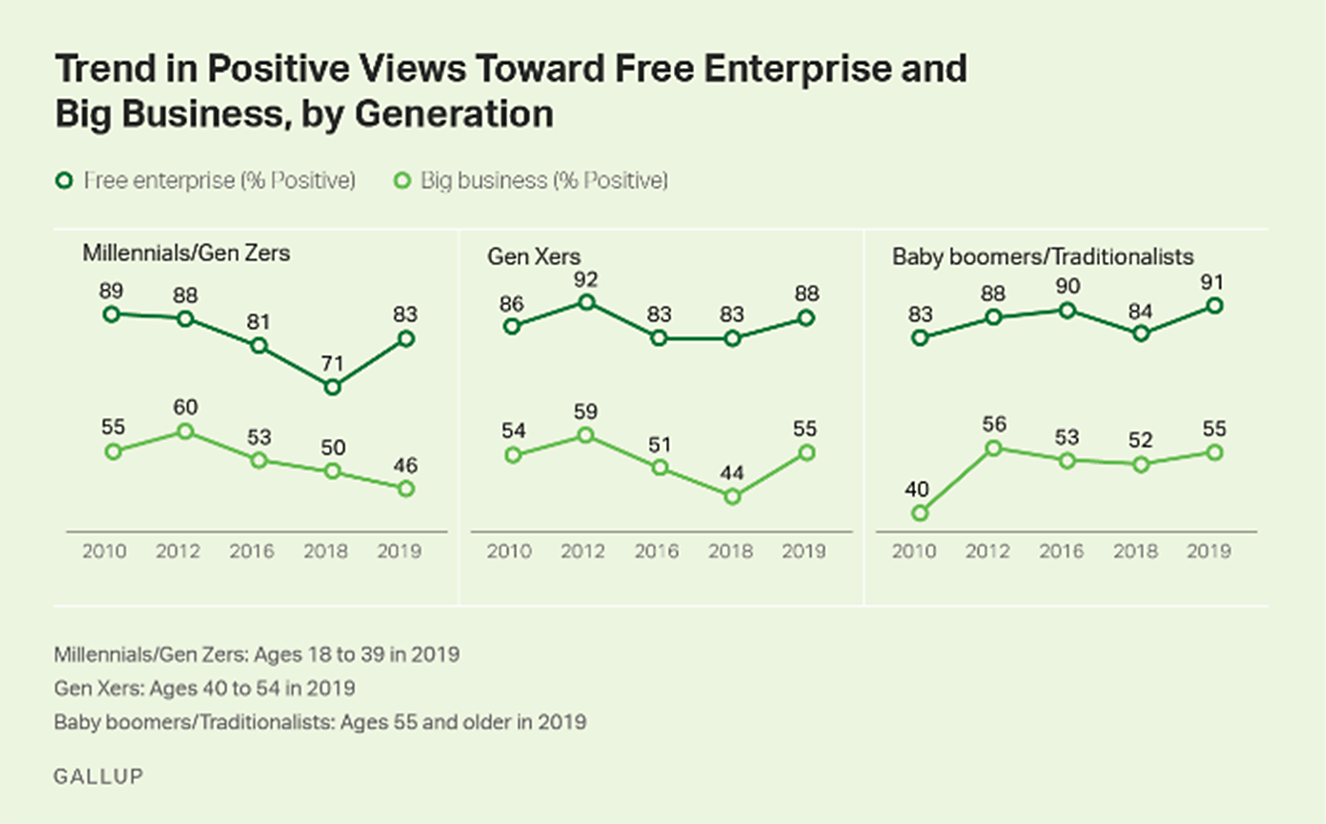

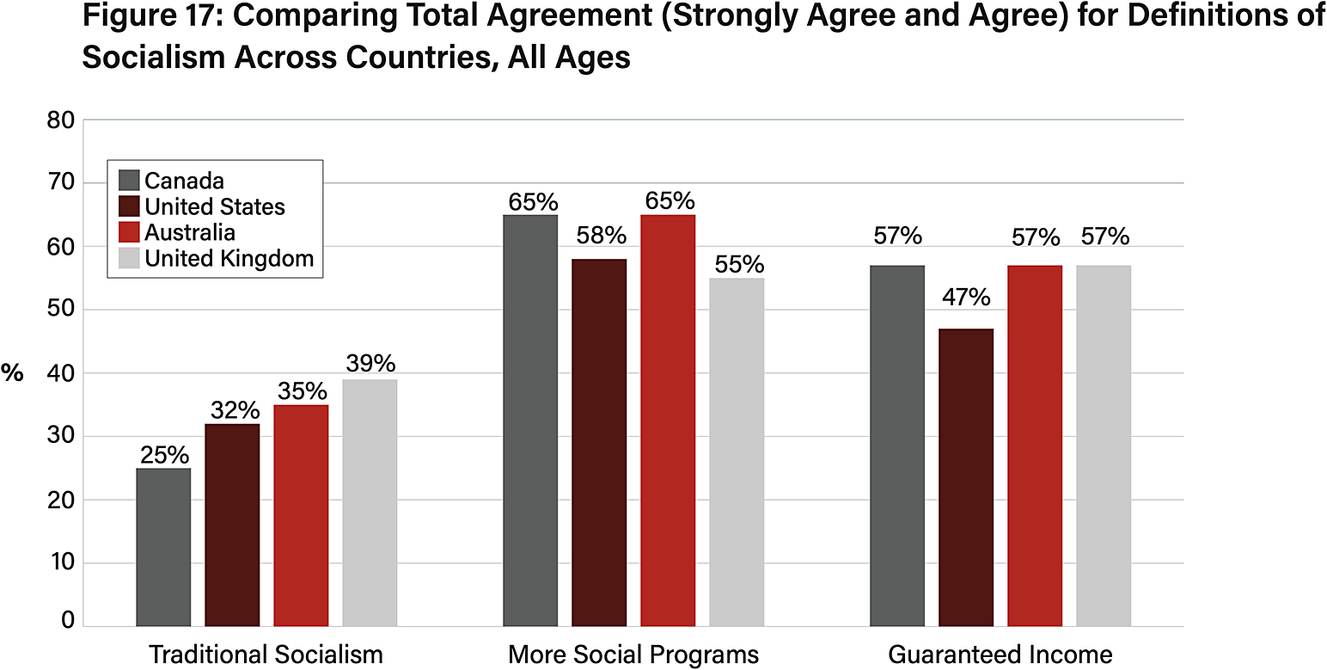

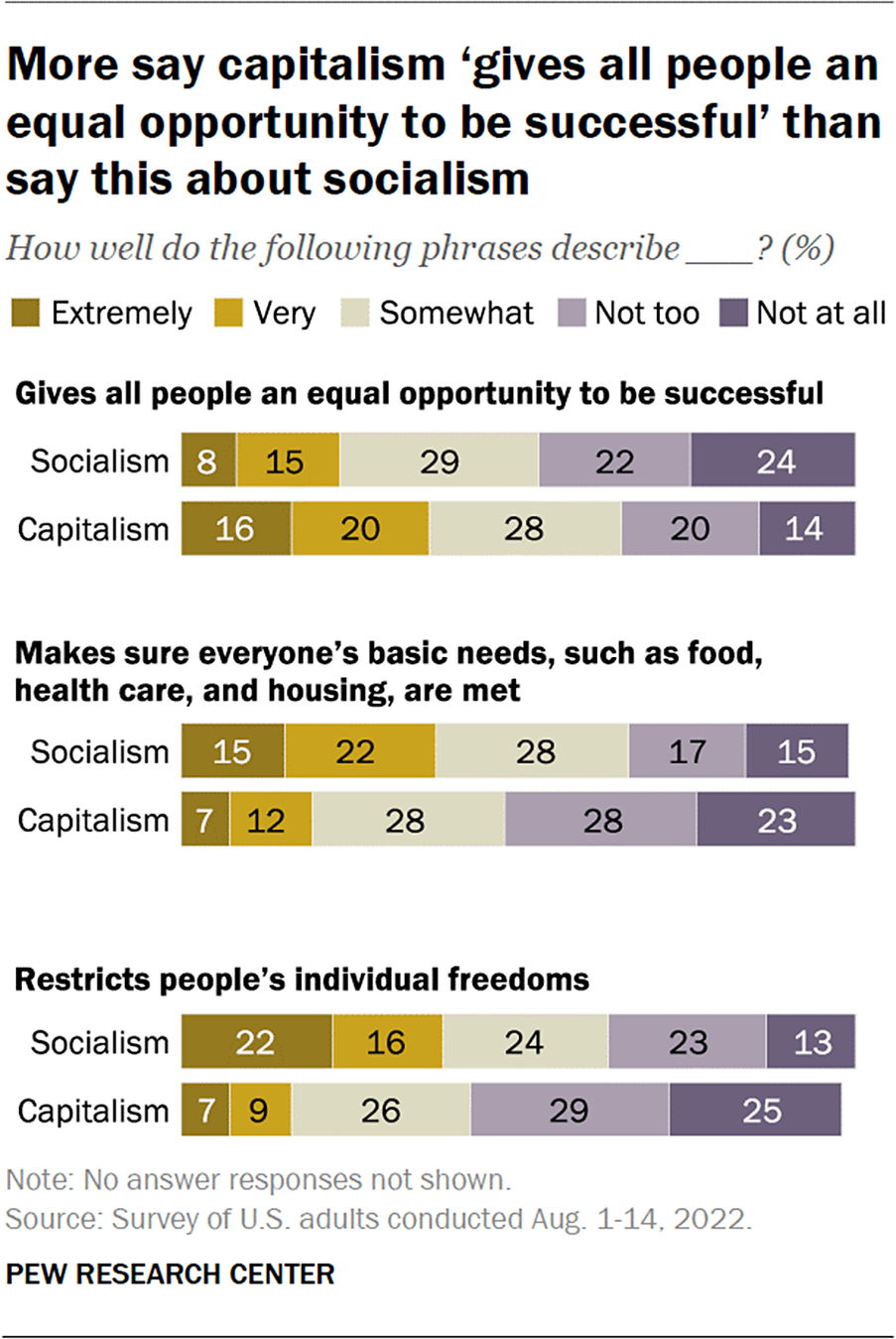

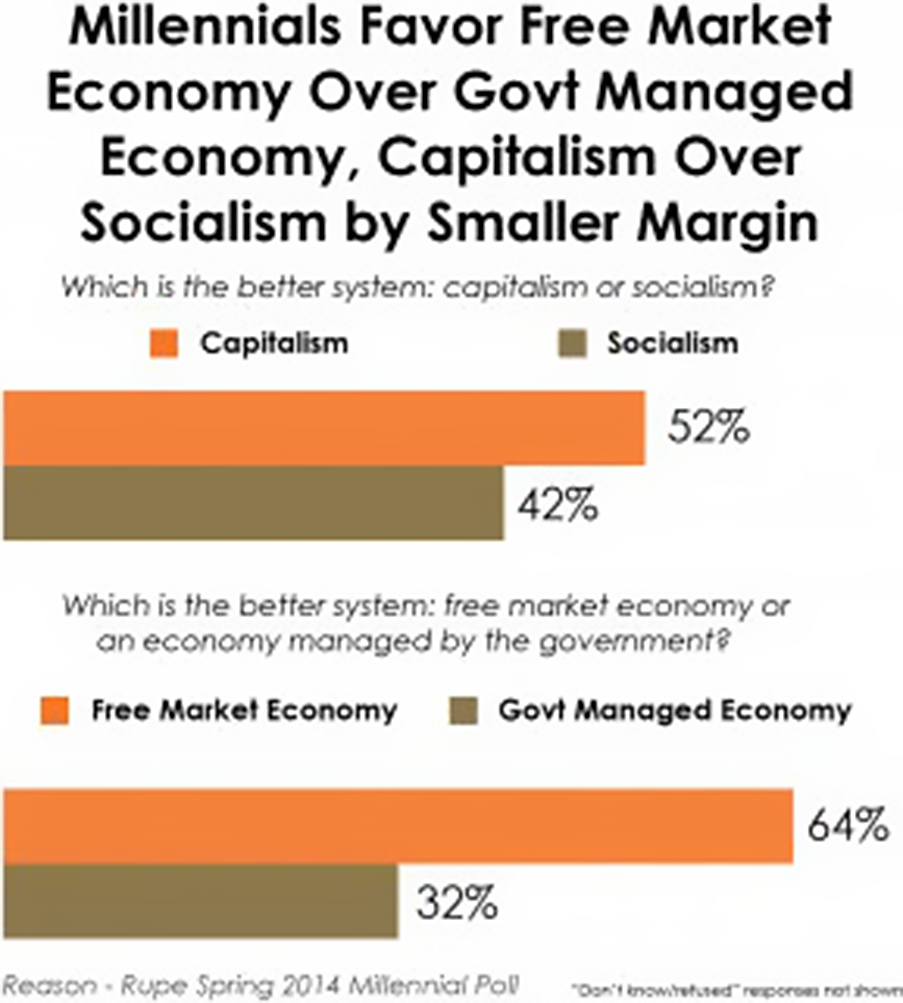

Millennials are perceived to be in favor of “socialism,” but what they understand by that word may be different from socialism as we know it. For those unfamiliar with the Cold War era, their model of socialism is that of Nordic countries. Nordic countries are advanced capitalist welfare states combined with a high degree of globalization and a market economy (see Figure 3). In the meanwhile, millennials are perceived to be in favor of income redistribution, but they tend to trust government less and are skeptical about government intervention in general (see Figure 4). Also, as other generations do, they tend to favor free market economy and free enterprise over big business (see Figure 5). Furthermore, they understand “socialism” not in a traditional sense, but as providing more social services and guaranteed income (see Figure 6). They may be critical of the current form of capitalism, but they do not really wish to go back to old-style socialism.

Figure 3. People appreciate capitalism giving all people an equal opportunity.Footnote 91

Figure 4. Millennials favor free market economy over government-managed economy.Footnote 92

Figure 5. Younger people prefer free enterprise.Footnote 93

Figure 6. People want more social programs and guaranteed income than traditional socialism.Footnote 94

Arguably, millennials are the generation surrounded by new technology as well as being practitioners of the gig and sharing economy. Their lifestyle tends to downplay material acquisition, as they show strong interest in environmental issues. Most of all, they cherish freedom and democracy. It is quite possible that they are already living in a future vision of capitalism.

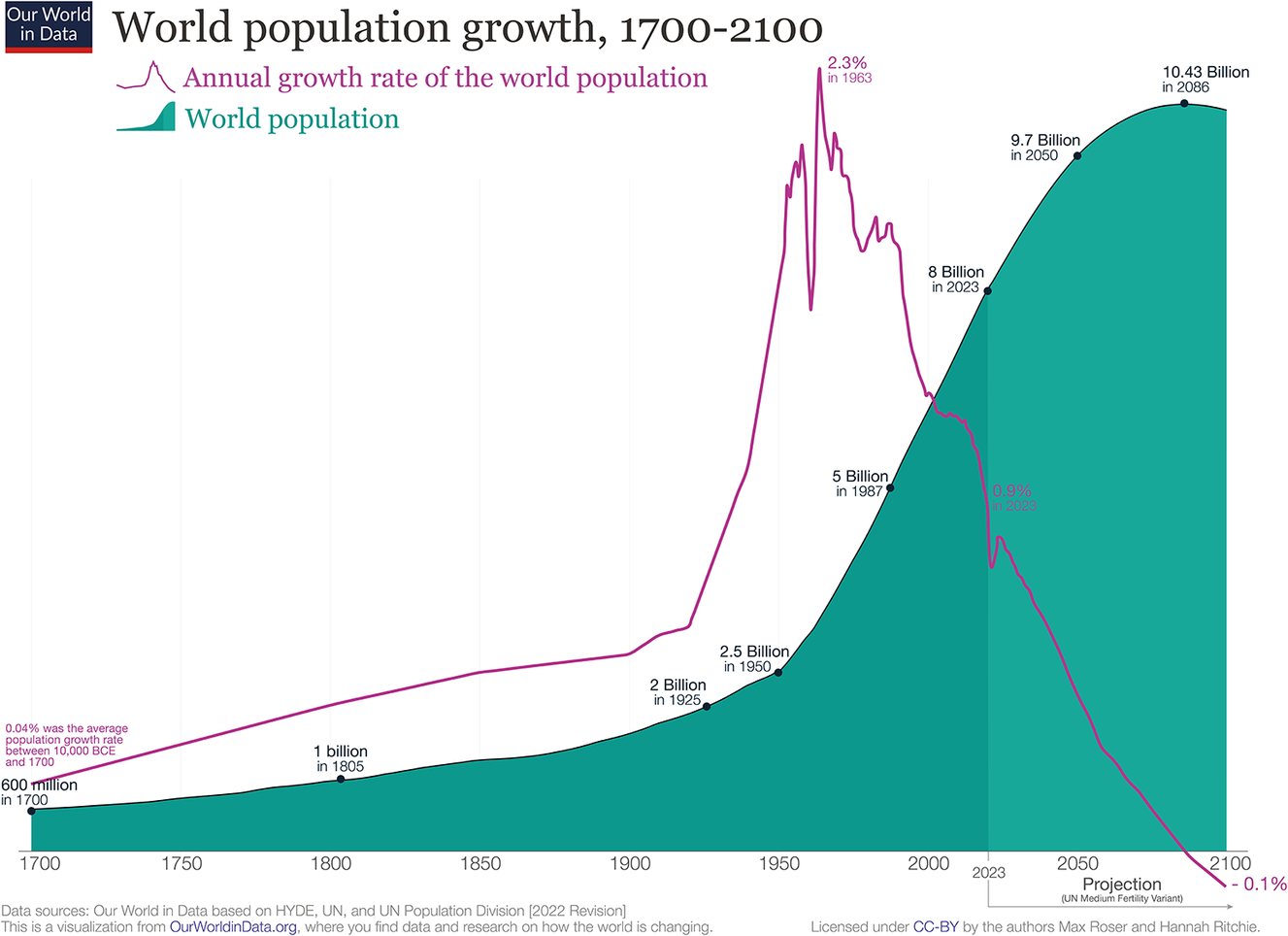

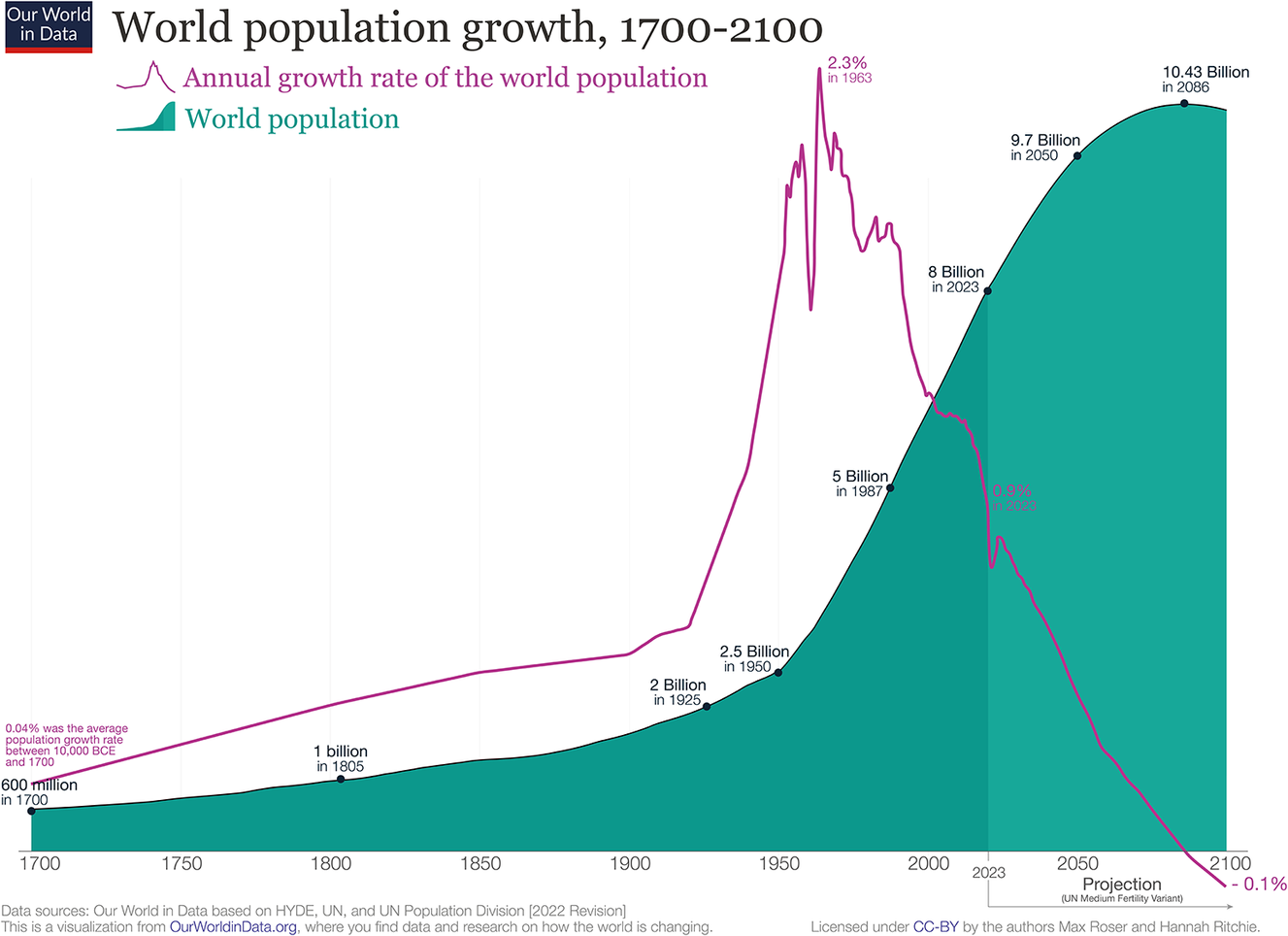

Second, even though one feels confident about dealing with current challenges, there may be a genuine fear for the future of capitalism, from a Smithian perspective, because of depopulation. The world population growth rate is already declining, and it is estimated to decrease from a peak of 10.43 billion in 2086 onward.

If this happens, one may have to worry about the implications of this for the world, based on the Smithian dictum that the “division of labor is limited by the market.” Smithian growth process entails a virtuous interdependence between increased population and increased prosperity through knowledge generation, supported by the above-mentioned Smithian dictum. Charles Jones argues for this linkage from a modern theoretical perspective, and he voices concerns about the prospects for economic growth, namely, that today’s declining fertility rate would slow down and eventually halt economic growth in the future (see Figure 7).Footnote 95 To counter this possibility, one could argue that we need all people, regardless of gender, ethnicity, and regions, to come on board to contribute to the growth process. Beyond that, would AI and robots sustain economic growth in the future?

Figure 7. World population will decrease in the future.Footnote 96

Finally, I would like to touch upon the motivation behind why Smith wrote what he wrote. Who is the impartial spectator, by the way? It should be not the Adam Smith who lived a real life, but the ideal person whom Adam Smith thought he should be. He is the person who does not side with special interests or the privileged, but with the general interests of the people. After all, that is the ideal political economist. And this should also apply to the ideal who Wolf characterizes as follows:

[I]t is not enough for members of elites to be clever, well trained, and ambitious if they are also self-satisfied, narrowly educated, and selfish, possibly even amoral. Members of a functioning elite, which includes the business elite, need wisdom as well as knowledge. Above all, they need to feel responsible for the welfare of their republic and its citizens. Indeed, if there are to be citizens at all, members of the elite must be exemplars. It is not hard: instead of lies, honesty; instead of greed, restraint; instead of fear and hatred, appeals to what Abraham Lincoln called “the better angels of our nature.”Footnote 97

Moreover, in The Theory of Moral Sentiments,Footnote 98 Smith asks how one can persuade the legislator, “who seems almost dead to ambition,” to think more about public affairs. Smith’s tactic is to appeal to the

same love of system, the same regard to the beauty of order, of art and contrivance. … If you would hope to succeed, you must describe to him the conveniency and arrangement of the different apartments in their palaces; you must explain to him the propriety of their equipages, and point out to him the number, the order, and the different offices of all their attendants. If any thing is capable of making impression upon him, this will. (TMS IV.i.11)

The Smithian tactic is to apply the famous “invisible hand” argument, which relies on unintended consequences. Given this, there is a hope that social-scientific inquiry may promote public spirit, and therefore action toward better public policy:

Nothing tends so much to promote public spirit as the study of politics, of the several systems of civil government, their advantages and disadvantages, of the constitution of our own country, its situation, and interest with regard to foreign nations, its commerce, its defence, the disadvantages it labours under, the dangers to which it may be exposed, how to remove the one, and how to guard against the other. Upon this account political disquisitions, if just, and reasonable, and practicable, are of all the works of speculation the most useful. Even the weakest and the worst of them are not altogether without their utility. (TMS IV.i.11)

I believe that a gathering of the International Adam Smith Society would eventually offer “the most useful” speculation to promote public spirit.

Acknowledgments

This essay is based on a keynote speech I delivered at the International Adam Smith Society Conference held at Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan on March 12, 2024. I would like to thank Maria Pia Paganelli, Tatsuya Sakamoto, and Shinji Nohara for giving me such an honor. I am grateful for the excellent research assistance of Motonori Ishii. A Research Grant I received from JSPS (No.24K04810) is also greatly appreciated.

Competing interests

The author declares none.