It has been over a decade since the construct of collective psychological ownership (CPO) was first introduced into the organizational behavior literature (Pierce & Jussila, Reference Pierce and Jussila2010). Since its inception, scholarly engagement with CPO has expanded beyond the traditional boundaries of work and organizational sciences, reaching a wide range of interdisciplinary domains. These include, but are not limited to, environmental studies (e.g., Contzen & Marks, Reference Contzen and Marks2018), urban studies (e.g., Szamatowicz & Paundra, Reference Szamatowicz and Paundra2019), marketing (e.g., Kumar, Reference Kumar2019), as well as entrepreneurship and family business research (Yttermyr & Wennberg, Reference Yttermyr and Wennberg2021).

The construct of CPO has also been applied to a diverse array of ownership targets. Some of these are macro-level entities, such as nations, territories, nature, and organizations, while others pertain to micro-level phenomena, including individual attitudes, specific behaviors, written works, personality traits, one’s job or work, and tangible objects such as toys. In addition to its conceptual diffusion across disciplinary boundaries, CPO has also received empirical attention across a wide spectrum of cultural and national contexts, including China, Finland, India, Kenya, Lithuania, Romania, and the United States.

To date, the empirical literature on CPO appears to have developed along two primary streams concerning its conceptualization and measurement. The first stream conceptualizes CPO as a psychological state embedded within the collective cognition of a group or team (e.g., Giordano, Paient, Passos & Sguera, Reference Giordano, Paient, Passos and Sguera2020; Gray, Knight & Baer, Reference Gray, Knight and Baer2020; Liang & Zhao, Reference Liang and Zhao2021; Martinaityte, Unsworth & Sacramento, Reference Martinaityte, Unsworth and Sacramento2020; Pierce, Jussila & Li, Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018; Pierce, Li, Jussila & Wang, Reference Pierce, Li, Jussila and Wang2020). In these studies, CPO is operationalized and assessed at the group or team level, often in conjunction with other collective constructs.

The second stream, which constitutes the majority of empirical investigations, examines CPO from the perspective of the individual. These studies explore an individual’s psychological ownership of macro-level entities that are jointly owned or shared with others, such as organizations (e.g., Henssen & Koiranen, Reference Henssen and Koiranen2021; Su, Liang & Wong, Reference Su, Liang and Wong2021a; Su & Ng, Reference Su and Ng2019b) territories, and natural resources (Kirk & Rifkin, Reference Kirk and Rifkin2022; Nijs, Martinovic, Verkuyten, & Sedikides, Reference Nijs, Martinovic, Verktenan and Sedikides2021; Nooitgedagt, Martinović, Verkuyten, & Maseko, Reference Nooitgedagt, Martinović, Verkuyten and Maseko2022; Selvanathan, Lickel & Jetten, Reference Selvanathan, Lickel and Jetten2021; Storz et al., Reference Storz, Martinovic, Verkuyten, Žeželj, Psaltis and Roccas2020; Toruńczyk-Ruiz & Martinović, Reference Toruńczyk-Ruiz and Martinović2020). In this line of research, CPO is measured and analyzed at the individual level.

To date, the existing literature lacks a comprehensive synthesis of the two predominant streams of CPO research. It remains unclear why these distinct trajectories have evolved from the foundational conceptual framework proposed by Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010). Moreover, there is limited understanding of the methodological challenges and practical issues encountered in the empirical implementation of CPO across various research settings. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to provide an integrative review of the literature on CPO, from its origins within organizational contexts to how it subsequently extended into broader social contexts. Specifically, we aim to synthesize the existing literature that builds upon the foundational construct of CPO and how the literature relates CPO with other research constructs. We identify the conceptual and methodological challenges encountered in empirical investigations and develop a research agenda for future research.

To achieve these goals, we conducted a comprehensive literature review of studies that stem from the seminal work by Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010) where CPO appears to have first appeared. We found 96 studies, the majority of which are empirical studies, that examined a diverse range of CPO targets across multiple academic disciplines. We first systematically analyzed how these studies have approached CPO both conceptually and methodologically. In particular, we examine how these studies position CPO in their conceptual model, either as an antecedent, an outcome, a mediator, a moderator, or just a correlate. We then identified issues and concerns in its operationalization and measurement. We conclude the paper with an agenda for future research of CPO.

Background

‘“Ours”, a small word, arising out of a shared events, when collectively experienced and recognized by a group of people who experience themselves as “us”, it is “deceptive in its power and importance”, capable of binding people together and controlling their behavior in pursuit of a common cause, such as marking, claiming, and defending a territory.’ (Pierce & Jussila, Reference Pierce and Jussila2010: 827, Reference Pierce and Jussila2011, 237).

The construct of CPO originates from foundational work on psychological ownership at the individual level, situated within the broader context of organizational arrangements (Pierce, Rubenfeld & Morgan, Reference Pierce, Rubenfeld and Morgan1991). In their seminal study, Pierce and colleagues compared employee-owned organizations with those in which employees were compensated primarily based on time worked. Their findings indicated that when employees perceived themselves as genuine owners, possessing rights analogous to those associated with personal property such as homes, they experienced a psychological sense of ownership. This insight underscored the notion that ownership may manifest not only as a legal or formal condition, but also as a psychological state. Pierce and his collaborators termed this phenomenon psychological ownership. It is noteworthy that in the same year, other studies (cf. Pierce & Jussila, Reference Pierce and Jussila2010) also recognized that feelings of ownership are inherently cognitive and reside within the human psyche, further reinforcing the conceptual foundation of psychological ownership as a mental construct.

These works led to the emergence of Pierce, Kostova and Dirks (Reference Pierce, Kostova and Dirks2001; Reference Pierce, Kostova and Dirks2003) initial theorizing on psychological ownership. They indicated that psychological ownership is a condition that can exist within the mind of an individual and his/her relationship with some target of ownership as exclusively ‘mine’ (e.g., that hammer, office, authored text are ‘mine’) and/or in recognition of the fact that others may feel similarly toward the same object (e.g., this is ‘my’ colleague). Thereby, the object is referred to as ‘my’, ‘mine’, or ‘ours’ (the word ‘ours’ is inclusive of ‘mine’, thus a dual possessive pronoun).

Recognizing that organizational work is inherently collaborative and rarely performed in isolation, the concept of psychological ownership was subsequently extended to the collective level. Pierce and Jussila formally defined CPO as a ‘collectively held sense (feeling) that this target of ownership (or a piece of that target) is collectively “ours”’ (Pierce & Jussila, Reference Pierce and Jussila2010: 812). Unlike individual psychological ownership, CPO is socially constructed and shared among members of a group or team, representing a collectively held cognitive-emotional state.

Notably, earlier scholarship (cf. Pierce & Jussila, Reference Pierce and Jussila2010) had already observed manifestations of possessive behavior at the group level. For instance, prior studies documented how groups such as street gangs symbolically and behaviorally claimed ownership over physical spaces like street corners or neighborhoods, illustrating the social dynamics of territoriality and collective possession.

Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010) approached CPO as though it is a ‘collective mind’ (a la Weick & Roberts, Reference Weick and Roberts1993) or as a ‘collective cognition’ (e.g., Cooke, Reference Cooke2015; Gibson, Reference Gibson2001). Weick and Roberts referred ‘collective mind’ as ‘people who act as if they are a group interrelate their actions with more or less care, and focusing on the way this interrelating is done reveals collective mental processes that differ in their degree of development’ (Weick & Roberts, Reference Weick and Roberts1993: 360). Gibson defined ‘collective cognition’ as ‘the group processes involved in the acquisition, storage, transmission, manipulation, and use of information’ (Gibson, Reference Gibson2001: 123). It is through interactive dynamics that a group of individuals who consider themselves as ‘us’ come to a ‘single and shared’ mindset as it pertains to some object material (e.g., club house) or immaterial (e.g., ideas). Pierce and Jussila referred to this emergent phenomenon as a shared mental model, developed through the cognitive interdependence among group members (Pierce & Jussila, Reference Pierce and Jussila2010: 811). This shared mindset underpins the experience of CPO, wherein the target of ownership is perceived not merely as ‘mine’, but as ‘ours’, reflecting a collectively held sense of possession.

A theoretical extension of CPO at the individual level

Building upon the conceptualization of the ‘group mind’, Pierce and colleagues developed a measurement instrument for CPO (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018) and subsequently applied it within the context of work teams (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Li, Jussila and Wang2020). These empirical contributions were situated within organizational settings, where the focal unit of analysis was the team or group. Concurrently, however, a significant theoretical expansion of CPO emerged, extending its relevance beyond organizational boundaries into broader societal contexts (e.g., Verkuyten & Martinovic, Reference Verkuyten and Martinovic2017).

This stream of literature emerges in the areas of territorial claims, intergroup relations, interpersonal conflict, and in-group solidarity/cohesion (e.g., Nijs, Martinovic, Verktenan & Sedikides, Reference Nijs, Martinovic, Verktenan and Sedikides2021; Storz et al., Reference Storz, Martinovic, Verkuyten, Žeželj, Psaltis and Roccas2020; Verkuyten & Martinovic, Reference Verkuyten and Martinovic2017). The disruptions caused by wars, domestic political upheaval, economic collapses, environmental disasters (e.g., drought, earthquake, global warming, rising oceans), and more have given rise to individuals being on the move and often times in large numbers. Flows of migrants from their home countries (regions, territories) are seeking entry into spaces that currently appear to be more stable and promising. They are met with local populations who are taking a stand not in ‘my (our) country’ (i.e., a sense of ownership for one’s territorial space) in such places as Southeast Asia, Eastern and Western Europe, and the United States.

It is clear that the targets of ownership in these settings are far beyond the initial targets of CPO in the organizational setting, such as a job, work, a project, an office space, or other intangible organizational assets such as knowledge. Instead, these targets are much bigger and in a greater geographical scope, such as country, territory, nature, water, and forest. This leads to an empirical challenge in these settings, i.e., it is difficult, and sometimes impossible, to identify what the group is because all the individuals in the organization, the country, the tribe, or the territory form one group. It is also difficult to define what is the right size of the group or team to measure CPO. Instead, these empirical studies measure CPO at the individual level.

Unlike the seminal conceptualization of CPO in the work context where CPO emerges from among group members through dynamic engagement in work and information processing, the emergence of CPO in the abovementioned social settings may follow a different pathway. Early child development research indicates that individuals are generally aware that certain ownership targets are shared collectively, and that a personal sense of ‘mine’ is embedded within a collective sense of ‘ours’, rather than necessarily resulting in CPO (e.g., Huh & Friedman, Reference Huh and Friedman2017). According to Verkuyten (Reference Verkuyten2024), the social identity framework which encompasses both social identity theory and self-categorization theory (Hogg & Turner, Reference Hogg and Turner1985; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981) offers a unified approach for analyzing CPO across different ownership targets and contexts. It is noteworthy that this perspective is briefly surveyed by Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010) in their initial conceptualization. Verkuyten (Reference Verkuyten2024) further contends that incorporating the social identity perspective more thoroughly can significantly advance research in the field of CPO, especially in response to the various measurement challenges in the empirical studies.

We agree that the social identity perspective is a way in which to explain and predict intergroup behavior on the basis of perceived group status differences. There is, then, a need for or desirability of social identity to be a precursor to the emergence of CPO. We also acknowledge that the attractiveness of a target of ownership may be strong enough such that an individual is driven to a particular group to gain access to a sense of belongingness. The emergence of the shared (collective) psychological ownership of a particular target, then, is bigger than the ones in the team/group context, such as territory and organization.

Overview of the review

To conduct this literature review, we followed the guidelines established by Siddaway, Wood and Hedges (Reference Siddaway, Wood and Hedges2019). For this literature review, the language of the publication was limited to English, and the range of the publication dates was set from January 1, 2010 to Dec. 31, 2024. First, we conducted searches in Google Scholar to find all the studies that cited Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010) to build an initial list of studies that have investigated CPO. We received a total of 463 studies. Second, we searched Web of Science, Academic Source Premier, Business Source Premier, Psych Info, and ProQuest databases using keywords that included ‘collective ownership’, ‘collective psychological ownership’, and ‘group ownership’ to complement the initial list of studies from the first search. A total of 538 publications including dissertations and theses were found. Combining these two pools of studies and removing duplications, we received 560 studies to start with.

To align with the purpose of this literature review, which is to examine how CPO is conceptually extended and empirically examined in different academic disciplines, we removed studies that simply cited Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010) but did not have CPO as a major research construct in the conceptualization and corresponding empirical study. Two co-authors worked independently on identifying the relevant studies to keep in the final sample. Disagreement in their independent classification was resolved upon further discussions between the co-authors. As a result, we retained a list of 96 studies in our final sample.

The two co-authors proceeded with the coding procedure of these 96 studies. They read the publications independently and coded the studies according to the criteria shown in the tables in the main text and the appendix. Discrepancies in coding were addressed upon discussions. The results are summarized in the tables.

Results

This section focuses exclusively on findings derived from the coded results presented in the appendix, in alignment with the objectives of this literature review. Readers interested in examining additional dimensions of CPO research are encouraged to conduct their own analyses using the comprehensive coding data provided in the appendix.

Study contexts and target of CPO

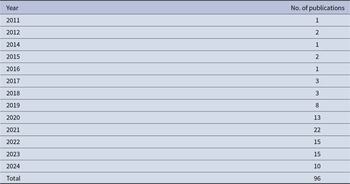

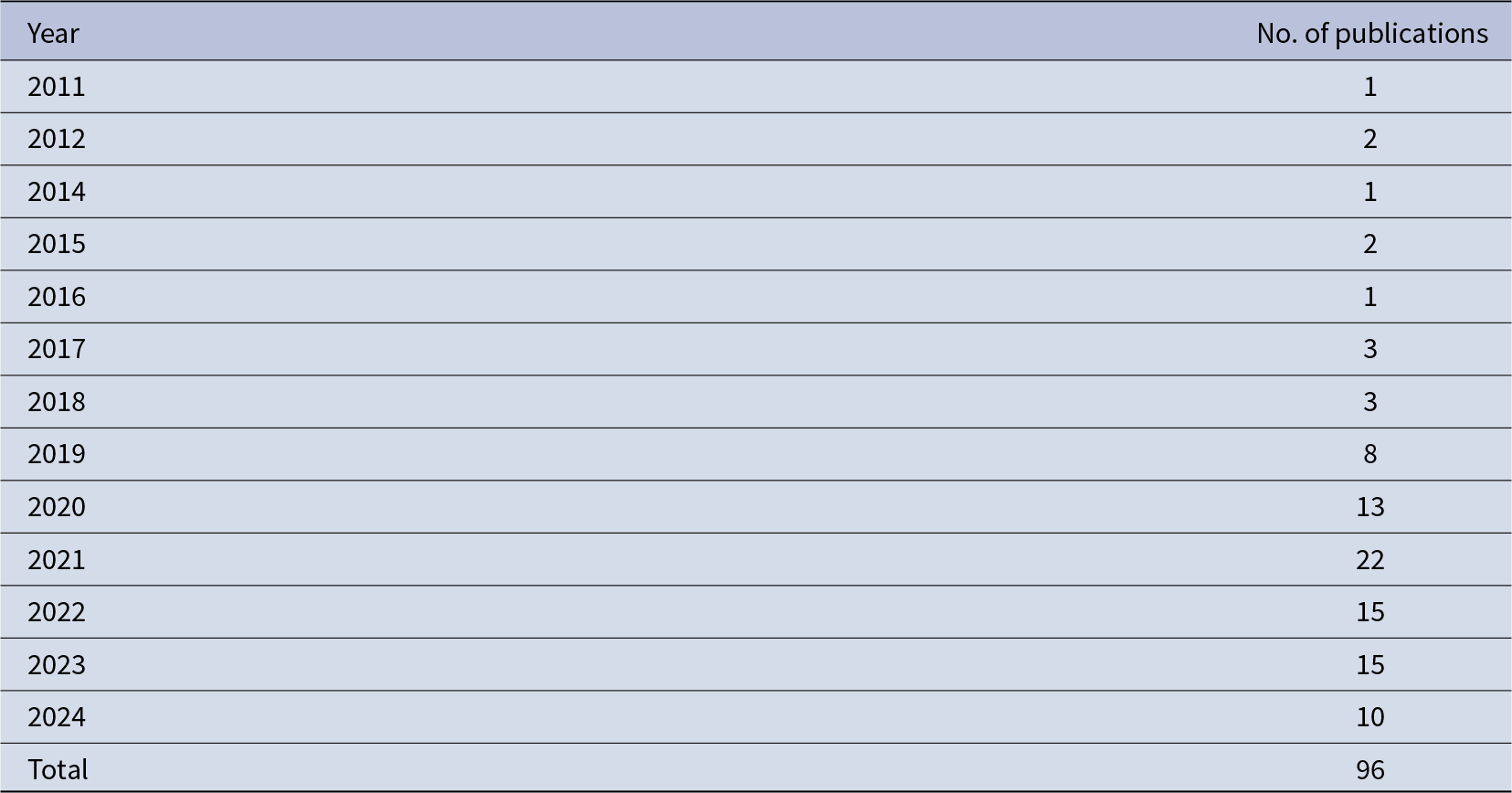

Table 1 shows the number of CPO publications by year since 2011. There has been a significant increase in the number of publications since 2019. We anticipate that the growing trend may continue in the future.

Table 1. Number of CPO studies by year

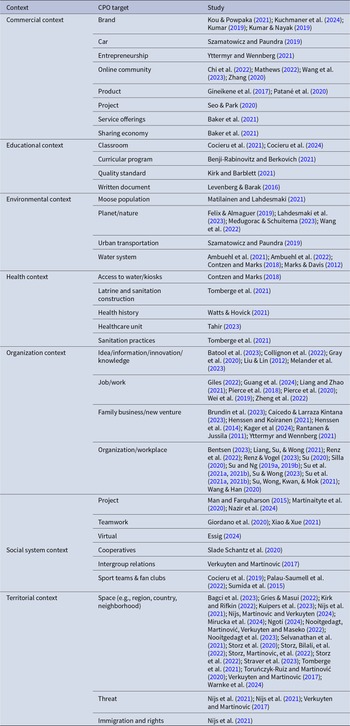

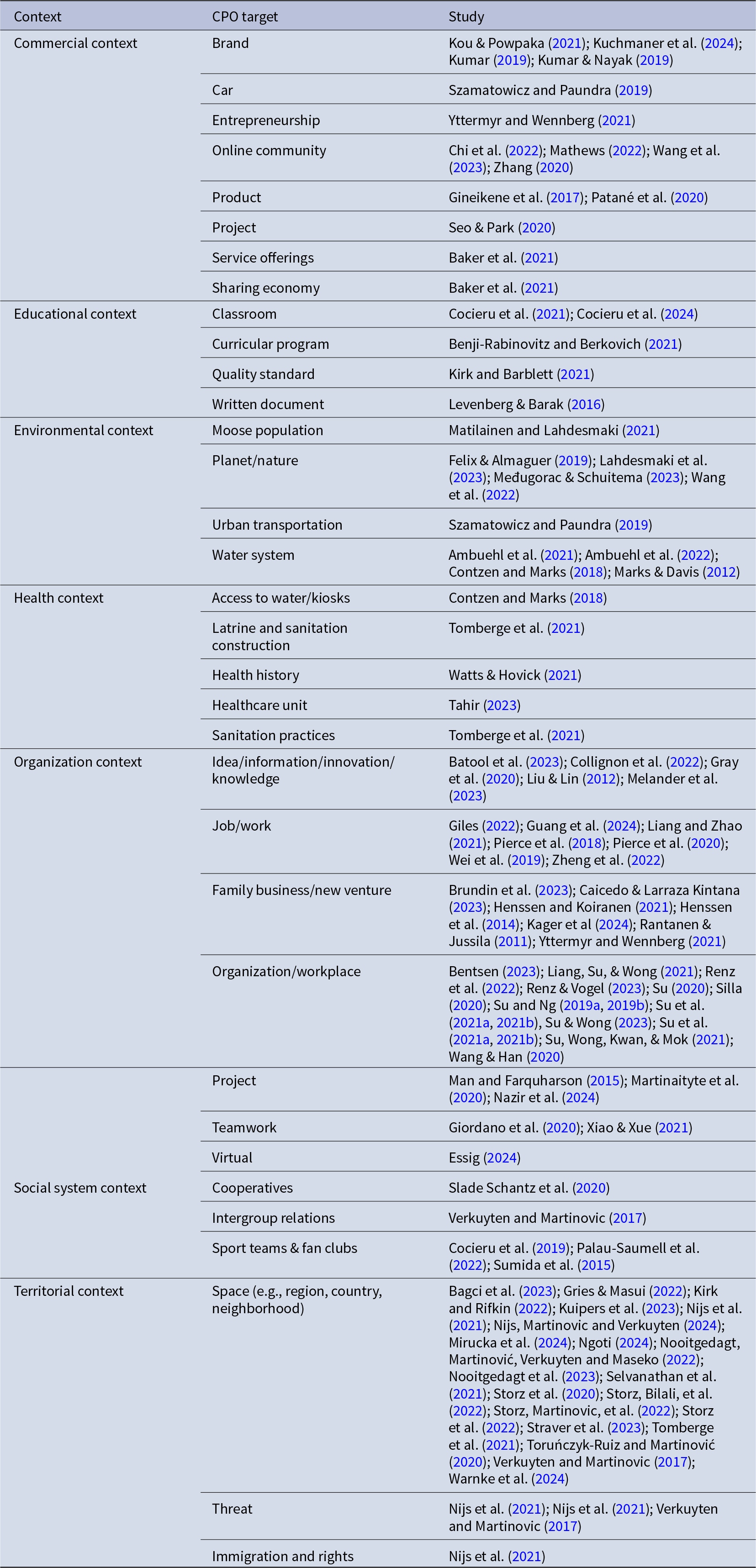

Table 2 shows the categorization of these 96 studies in terms of the general context and the target of CPO. We grouped these studies into 7 different contexts and the number of CPO targets in these studies exceeded 20. The most studied CPO target seems to be at the macro level, with organization and territory, followed by job or work. A more detailed summary of the targets of CPO can be found in the appendices (Tables S5 and S6). In Table 2, Column 1 indicates the ‘context’ (environments, settings) in which the CPO research has been conducted (e.g., Commercial, Educational, Environmental). In Column 2, we identity the ‘target’ that was the focus of an investigation in the context identified in Column 1. In the Educational Context, for example, there was a focus on the classroom as one target. In Column 3, you will find the relevant author(s) name and year of their publication. In addition, we have uncovered the existing empirical studies of CPO from very diverse disciplines (e.g., Organizational studies, Education, Rural and Urban studies) as well as from many different countries in the world (e.g., Britain, China, India). The details of these disciplines and countries can also be seen in the appendices.

Table 2. Research contextual focus and CPO target

Overall, the CPO construct appears to have emerged from work and organizational studies literature, and it quickly spread to a diverse set of other disciplines. The Organization Context seems to be the subject of greatest interest, followed by the Territory Context.

Related theory and role of CPO

Because of the diverse research interests from a variety of academic disciplines, it is not surprising to see that CPO has been examined together with other theories and concepts from these disciplines such as attachment (Storz et al., Reference Storz, Martinovic, Verkuyten, Žeželj, Psaltis and Roccas2020; Toruńczyk-Ruiz & Martinović, Reference Toruńczyk-Ruiz and Martinović2020), change management (Benji-Rabinovitz & Berkovich, Reference Benji-Rabinovitz and Berkovich2021), engagement (Baker, Kearney, Laud & Holmlund, Reference Baker, Kearney, Laud and Holmlund2021; Chi, Harrigan, & Zhu, Reference Chi, Harrigan and Xu2022; Martinaityte et al., Reference Martinaityte, Unsworth and Sacramento2020; Ng & Su, Reference Ng and Su2018; Su, Reference Su2020), social capital (Chi, Harrigan & Xu, Reference Chi, Harrigan and Xu2022; Kirk & Rifkin, Reference Kirk and Rifkin2022), social norms (Contzen & Marks, Reference Contzen and Marks2018; Matilainen & Lahdesmaki, Reference Matilainen and Lahdesmaki2021), social identity (Storz, Martinović & Rosler, Reference Storz, Martinović and Rosler2022; Verkuyten & Martinovic, Reference Verkuyten and Martinovic2017), and more.

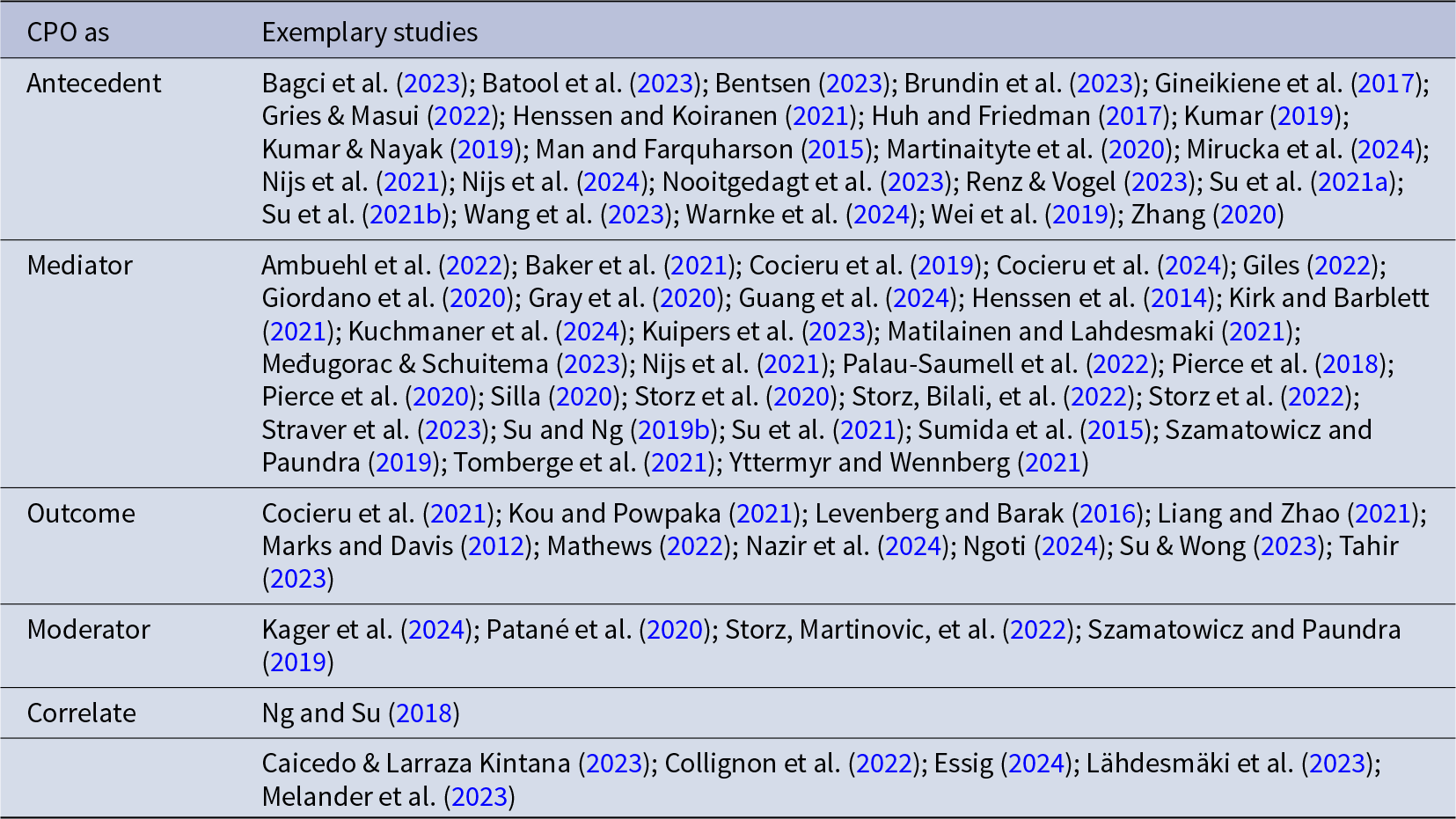

Regarding the role of CPO in the conceptualization in the study, we categorize whether CPO is an antecedent, a mediator, an outcome, a moderator, or just simply a correlate. The results are shown in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, CPO is most studied as a mediator variable, followed by an antecedent variable and an outcome variable. The least researched area is CPO as either a moderator or a correlate.

Table 3. Studies with CPO classifications

It is not surprising that CPO is mainly positioned as the mediating construct in the prior literature because the way Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010)’s theoretical framework laid out the focal role played by CPO, its development from the three route variables, and its subsequent impact on other variables. Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010) have further provided directions for future research to connect their framework to other root variables, which seems to have been well-received by the subsequent studies that apply the CPO framework to their corresponding domain of knowledge and make meaningful connections to the native constructs in their respective domains.

Measurement, unit of analysis, and CPO scale

There have mainly been two methodological approaches to the measurement of CPO in the literature. These measures and units of analysis for CPO are found to be either at the group level (i.e., group-mind, or collective cognition) or at the individual level. Regarding the scales that are used to measure CPO, three appear to be the most widely adopted. The first scale was developed by Pierce et al. (Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018) and the second by Su and Ng (Reference Su and Ng2019b). Before the development of these two scales, researchers adopted and modified Van Dyne and Pierce’s (Reference Van Dyne and Pierce2004) individually anchored measure for job-based psychological ownership to measure CPO. In addition to these three scales, other researchers developed their own scales. Next, we synthesize how the three scales were implemented in the studies that were at either the group level or the individual level.

Collective approach (group mind)

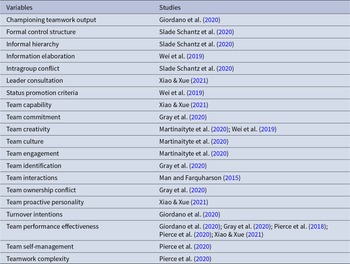

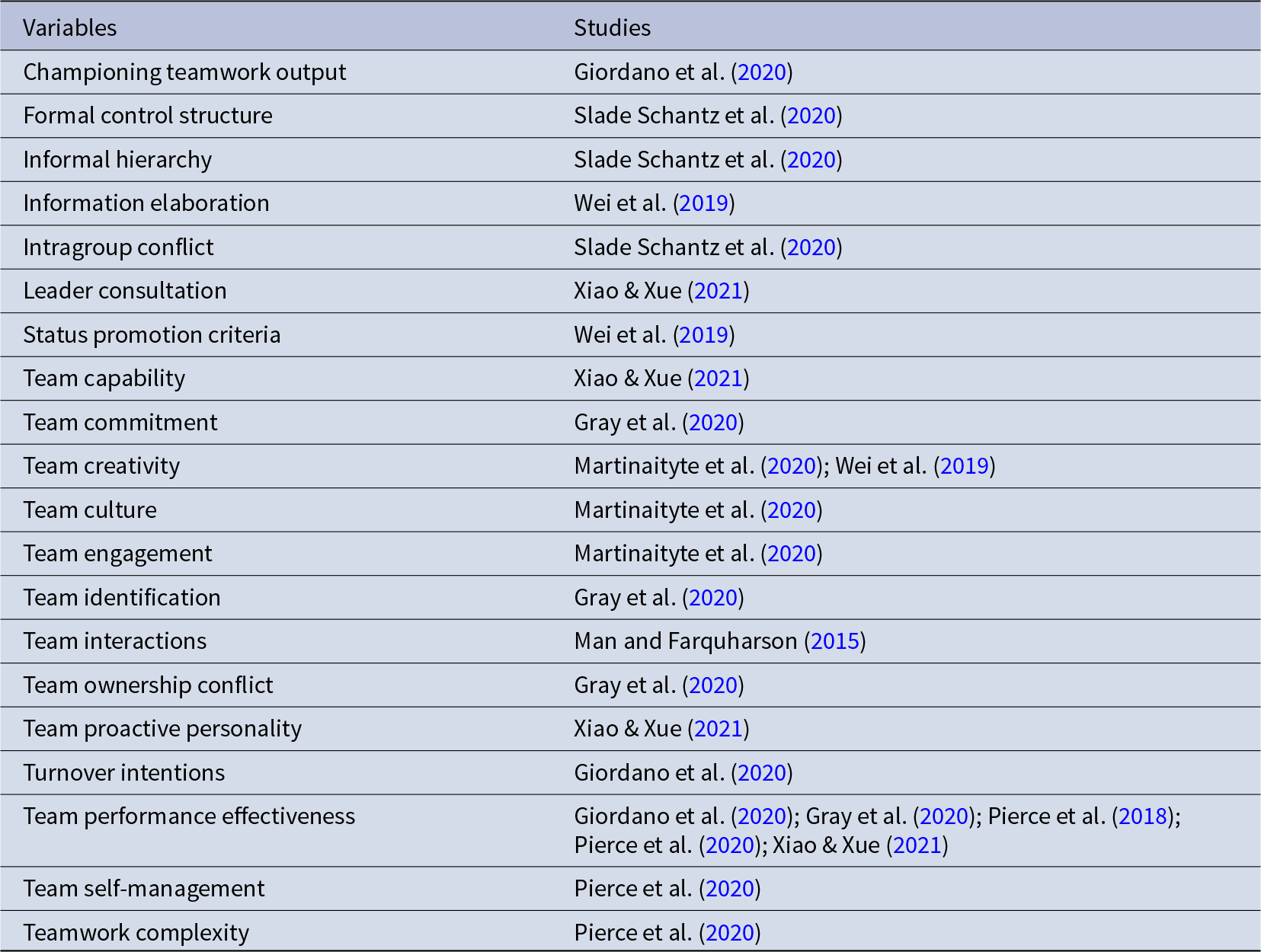

This first approach was focused on group or team as the unit of analysis and measured CPO using a scale developed and validated by Pierce et al. (Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018). With regard to the group-mind approach, we found a limited number of studies (i.e., Giordano et al., Reference Giordano, Paient, Passos and Sguera2020; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Knight and Baer2020; Liang & Zhao, Reference Liang and Zhao2021; Martinaityte et al., Reference Martinaityte, Unsworth and Sacramento2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018, Reference Pierce, Li, Jussila and Wang2020; Slade Schantz, Kistruck, Pacheco & Webb, Reference Slade Schantz, Kistruck, Pacheco and Webb2020; Wei, Liu, Liao, Long & Liao, Reference Wei, Liu, Liao, Long and Liao2019) that appear to have taken this tack (see Table 4).

Table 4. Research variables at the group/team level

A review of these papers finds that the conceptualization of CPO of these studies is consistent with the group-mind or collective cognition approach. Additionally, these studies measure each team/group member’s sense of collective psychological ownership and then aggregate them to form the group’s collective sense of ownership after testing for and finding within-group homogeneity (i.e., agreement) among the responses from team/group members as well as interrater reliability. This approach has been validated in the prior literature that studies team or applies multi-level analysis (James, Demaree & Wolf, Reference James, Demaree and Wolf1993; LeBreton & Senter, Reference LeBreton and Senter2008).

Further, Pierce et al. (Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018) in their selection of work teams that had the possibility of having a ‘group-mind’, only selected real teams which Wageman, Hackman and Lehman (Reference Wageman, Hackman and Lehman2005) characterized as teams with team membership clarity, stability, and team member interdependence, which differs from the perspective held by Wageman, Gardner and Mortensen (Reference Wageman, Gardner and Mortensen2012). In addition, the teams had to be relatively small (e.g., having no more than 10 members), to have worked on a recent project or task together, and had time to interact with one another during and upon completion of the project or task (seeds for the emergence of a collective cognition). These are necessary conditions for the existence of ‘group-mind’ or the presence of a ‘collective cognition’ (James et al., Reference James, Demaree and Wolf1993; LeBreton & Senter, Reference LeBreton and Senter2008).

Individual approach

On the other hand, the majority of the existing CPO studies adopted the second approach, the individual approach, with a certain degree of variation. These studies examine CPO at the individual level as they ask an individual to report on the CPO on their behalf and that of others.

Among these studies, several authors study CPO at the organizational level and therefore their unit of analysis is the organization (e.g., Henssen & Koiranen, Reference Henssen and Koiranen2021; Henssen, Voordeckers, Lambrechts & Koiranen, Reference Henssen, Voordeckers, Lambrechts and Koiranen2014). In doing so, the authors collect data from different organizations such as family firms (e.g., Henssen & Koiranen, Reference Henssen and Koiranen2021; Henssen et al., Reference Henssen, Voordeckers, Lambrechts and Koiranen2014) and ask one individual (e.g., the CEO or owner of the family business) from each organization to report their CPO of the organization. On the other hand, the majority of the other studies examine CPO at the individual level; thus, the unit of analysis is therefore the individual.

Regarding the CPO scale used in these studies that adopt the individual approach, we find four variations. The first is illustrated in those studies (e.g., Henssen & Koiranen, Reference Henssen and Koiranen2021) that adapt the individual psychological ownership scale developed by Van Dyne and Pierce (Reference Van Dyne and Pierce2004) to measure CPO. These studies modify the original psychological ownership scale by recasting the target of ownership from the singular form to the collective (plural) form (i.e., ‘my’ to ‘our’, ‘mine’ to ‘ours’).

A second example comes from by the work of Contzen and Marks (Reference Contzen and Marks2018). They ask each respondent to report their own feelings of CPO on a question such as ‘How much do you feel that you are one of the owners of ___the target of ownership___?’ Here the respondent is reporting on only their own feelings of the ownership of the target instead of the feelings of the group of people who may feel ownership for the same target.

A more recent tack applies to those studies (e.g., Kumar, Reference Kumar2019; Tomberge, Harter & Inauen, Reference Tomberge, Harter and Inauen2021) that adopt the CPO scale developed by Pierce et al. (Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018). These studies ask a respondent to respond to the ownership feeling on behalf of not only themselves but also their colleagues simultaneously in response to each of the questions in the CPO scale. However, because the focus of these studies is on an individual, there is no aggregation to the collective level.

The measurement of CPO done by Su and colleagues (e.g., Su & Ng, Reference Su and Ng2019b; Su, Wong & Liang, Reference Su, Wong and Liang2021a) is based on a scale developed by Su and Ng (Reference Su and Ng2019a). In these studies, each respondent is asked to report their personal sense of organization-based CPO. Additionally, they answered the same six organization-based CPO items as a representative on behalf of their whole group.

In summary, there is a moderate amount of variation in studies that follow this individual approach, yet none of those found have examined the construct as a group-mind or purely at the collective level. Because the unit of analysis of all of these above studies is at the individual level, the authors do not attempt to aggregate the individual data to form CPO at the group, team, or collective level. These studies, then, appear to assume using an individual’s perception of CPO that resides in an individual’s mind can represent CPO at the collective level, and this leads them to measure CPO as an individual psychological state or ask an individual of a social system (e.g., group, team, community) to report on CPO on behalf of the whole group. This is understandable because the target of collective ownership is about a much bigger social system.

Statistical analysis approach

We find a variety of analytical approaches in the empirical studies of CPO from this literature review. Because CPO is positioned as a mediator in the original framework (Pierce & Jussila, Reference Pierce and Jussila2010), it is not surprising that statistical approaches that are capable of examine mediating effects seem to be most widely adopted, such as structural equation modeling. In addition, conventional approaches such as regression and ANOVA are also found in a few studies. It is noteworthy that a couple of studies have applied multi-level analysis when CPO is investigated together with variables at a different level from the group level (e.g., Ng & Su, Reference Ng and Su2018; Su et al., Reference Su, Wong and Liang2021a; Tomberge et al., Reference Tomberge, Harter and Inauen2021; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Liu, Liao, Long and Liao2019).

Empirical findings regarding antecedents, correlates, and consequences of CPO

Finally, in this section we report on the empirically derived correlates of CPO. We will comment upon those observations derived from both methodological approaches (i.e., the group-mind and individual approaches). In general, these studies that adopt the group-mind approach provide support for the presence of CPO, its three Route variables (i.e., collective control over, collective intimate knowing of, and investment of our collective selves into the target of ownership), as well as a number of other antecedent conditions, and of possible effects.

Regardless of the methodological approach taken (group-mind or individual), there is support for the role played by each of CPO’s three direct Route variables which have been theoretically positioned as its most immediate causes (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Kearney, Laud and Holmlund2021; Cocieru, Lyle & McDonald, Reference Cocieru, Lyle and McDonald2021; Giordano et al., Reference Giordano, Paient, Passos and Sguera2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Li, Jussila and Wang2020). In addition, there are a couple of studies (e.g., Martinaityte et al., Reference Martinaityte, Unsworth and Sacramento2020; Tomberge et al., Reference Tomberge, Harter and Inauen2021) that have linked psychological ownership and collective psychological ownership, in support of the notion that ‘mine’ coexists under conditions of ‘ours’, even though there have been concerns whether feelings of CPO are accompanied by conditions of individual anchored psychological ownership.

There are a few other variables that are seen as antecedents of CPO, such as involvement (Contzen & Marks, Reference Contzen and Marks2018), autonomy (Henssen et al., Reference Henssen, Voordeckers, Lambrechts and Koiranen2014), distributed leadership (Kirk & Barblett, Reference Kirk and Barblett2021), job resources (Ng & Su, Reference Ng and Su2018), job demand (Ng & Su, Reference Ng and Su2018) and member identification (Ng & Su, Reference Ng and Su2018). CPO has been indirectly associated with team-work design and team-work complexity (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Li, Jussila and Wang2020), as well as team chemistry and interdependence of tasks (Cocieru et al., Reference Cocieru, Lyle and McDonald2021), by working through one or more of its Route variables.

The consequences of CPO include such variables as stewardship behavior (Henssen et al., Reference Henssen, Voordeckers, Lambrechts and Koiranen2014), change (Kirk & Barblett, Reference Kirk and Barblett2021), purchase intention (Kumar, Reference Kumar2019), engagement and creativity (Martinaityte et al., Reference Martinaityte, Unsworth and Sacramento2020), and attitude towards immigrant (Nijs et al., Reference Nijs, Martinovic, Verktenan and Sedikides2021). Among some of its other correlates are social loafing and turnover intentions (negative) (Giordano et al., Reference Giordano, Paient, Passos and Sguera2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018) and positive relationships with group potency (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018), team performance effectiveness (Giordano et al., Reference Giordano, Paient, Passos and Sguera2020; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Knight and Baer2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018, Reference Pierce, Li, Jussila and Wang2020), experienced responsibility (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018), personal initiative (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018), championing teamwork output (Giordano et al., Reference Giordano, Paient, Passos and Sguera2020), commitment (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Knight and Baer2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018), team identification (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Knight and Baer2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Jussila and Li2018), creativity (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Liu, Liao, Long and Liao2019), and other factors related to the job (Ng & Su, Reference Ng and Su2018). These empirically anchored findings appear to provide reasonably strong evidence in support of the current theorizing on CPO (Pierce & Jussila, Reference Pierce and Jussila2010). In particular, we summarize in Table 4 the group or team level research variables that have been examined together with CPO from this literature review.

An agenda for future research

Expanding study contexts

Our literature review finds a variety of contexts for the study of CPO. We encourage scholars from other science and social science disciplines that are not referenced in existing studies to make a logical connection between CPO and their target of research interests. Given the extensive use of teams/groups in today’s society, we call for more scholarship on CPO within that context, yet not to the exclusion of other viable areas. In the team context, there are a limited number of studies that have been conducted. Beside work teams in an organization, studies of teams in other social contexts such as sports, music, and non-profit organizations could provide additional insights into the role of CPO in these social contexts.

We also hope to see more future work building into their models the role of CPO played by economic and political systems (e.g., capitalism, socialism, as well as societal norms, ethos, and wildly accepted values, practices and traditions) in the development of CPO. We have seen an increasing number of empirical studies that examine individual psychological ownership beyond the organizational context such as the broader social context and their corresponding social behaviors such as pro-social behaviors (e.g., Jami, Kouchaki & Gino, Reference Jami, Kouchaki and Gino2021). We call for additional CPO studies in these similar study contexts. Exploration of the role of CPO in these expanded social contexts may well reveal additional moderators and or correlates of CPO, which may promote the research of CPO to address social issues.

In addition, it appears as though there are limited CPO literature that conceptually and empirically address issues pertaining to intergroup relationship in the organizational setting, despite some recent literature in the social sciences field (e.g., Verkuyten & Martinovic, Reference Verkuyten and Martinovic2017). This can arise when two or more groups in an organization have come to feelings of ownership for the same target of ownership (e.g., geographical space, ideas, authorship of written text) or conflict that arises when one party feels psychological ownership for a target of ownership, and another or other groups attempt to secure legal ownership over the same target of ownership.

Advancing the CPO theory

An important issue to be resolved relates to the theorization and conceptualization of CPO. Pierce, Kostova and Dirks (Reference Pierce, Kostova and Dirks2003) suggested that feelings of personal ownership can manifest themselves as one feeling as though they have exclusive ownership of an object. They also noted that a person may also feel that there are others who have or may have the same feeling. This conceptualization of CPO at the group or team level suggests that the ownership of the object is at a level that is different from the individual level. Future studies can continue to enrich the theoretical work of CPO, especially the theoretical distinctions between CPO and individual PO.

Because of the two divergent views and conceptualizations of CPO, there is a need to reconcile or integrate the two approaches. Future studies can explore the reason that leads to these two different views of CPO. It is easy to understand that, when the object of ownership is at a macro level, such as nation or country, the social identity approach seems to be in a better position to explain CPO. Studies of CPO in the micro setting can examine how the macro-level CPO and the micro-level CPO interact with one another.

Correlates of CPO

The current literature has done a good job of identifying a myriad of variables that are predictors of CPO (e.g., teamwork complexity, teamwork design). Missing from the current literature appears to be a focus on its motives (e.g., a need for group identity, effectance) as well as how individual personality differences (e.g., locus of control, individualism/collectivism, proactive personality) play a role as moderators or causal variables. We encourage the future exploration of the role of individual motivation and differences in CPO research, as well as group differences (e.g., size, homogeneity/heterogeneity, membership clarity, cohesiveness).

CPO studies that anchored from the social identity theory and the social categorization theory (Verkuyten, Reference Verkuyten2024) can contribute to the CPO literature by investigating the antecedent factors that lead to the emergence of CPO from the social identity perspective. The abundance of empirical studies based on the social identity theory and the social categorization theory have accumulated sufficient evidence that reveals the antecedent factors that lead to the development of social identity and social categorization. Future studies can investigate how these factors work as antecedents in the CPO setting.

While a majority of the empirical studies have considered CPO as either an antecedent factor or a mediator, more research can be done that examines CPO as the moderator. As a powerful psychological state in a group mind, the construct of CPO may execute its impact on a relationship between research constructs that are established in the prior literature. It is noteworthy to reveal how CPO improves or attenuates the relationship. Another major area that we observe that future studies can explore is to see the role of CPO in the leader-member exchange (LMX) domain. We have not found any studies from this literature review that have examined how CPO impacts leader-member relationships.

While prior CPO studies have examined various positive outcomes of CPO, we also encourage researchers to consider the potential that there are also negative effects that are associated with the presence of CPO. It is somewhat questionable that all of its effects are positive in nature. It is noteworthy to examine the dark side of CPO, which can be investigated at both the group level and the individual level (Avey, Avolio, Crossley & Luthans, Reference Avey, Avolio, Crossley and Luthans2009; Brown, Crossley & Robinson, Reference Brown, Crossley and Robinson2014).

As one example, while the literature has frequently found CPO to negatively relate to outcomes like turnover and burnout (i.e., Su, Reference Su2020; Su, Liang & Wong, Reference Su, Liang and Wong2021b; Su & Ng, Reference Su and Ng2019b; Su et al., Reference Su, Wong and Liang2021a), this may not universally be true; instead, there may exist other instances where CPO can lead to burnout and stress from the need to protect, nurture, and care for the target of ownership. We call for an expansion in this area inclusive of an examination of depression and other dimensions of subjective well-being.

As another example, Peng and Pierce (Reference Peng and Pierce2015) suggested and found evidence that individual PO is often associated with the resistance to share information. It is conceivable that CPO may well contribute, on occasion, to a resistance to share (information, ideas, tools, territory) (i.e., Batool, Raziq, Obaid & Sumbal, Reference Batool, Raziq, Obaid and Sumbal2023).

CPO can also contribute to the emergence of overly protective behavior as it relates to the target of ownership and as a detriment of others, the job, or larger social system (e.g., social system community, state, country), that can lead to collective ownership threat (Bagci, Verkuyten & Canpolat, Reference Bagci, Verkuyten and Canpolat2023; Nijs, Verkuyten & Martinovic, Reference Nijs, Verkuyten and Martinovic2021) and more generally, the exclusion of outsiders and less positive perceptions of immigrants (i.e., Kuipers, Martinović & Yogeeswaran, Reference Kuipers, Martinović and Yogeeswaran2023; Nijs et al., Reference Nijs, Martinovic, Verktenan and Sedikides2021; Straver, Martinović, Nijs, Nooitgedagt & Storz, Reference Straver, Martinović, Nijs, Nooitgedagt and Storz2023; Verkuyten, Reference Verkuyten2024). At the group or team level, it is worth investigating how CPO correlates with group loafing, group thinking, group equity, and group conflict under different boundary conditions.

Dynamics of CPO

We strongly encourage CPO scholars to take a deeper dive into the dynamic development of CPO, even though a couple of such studies have emerged recently (e.g., Baker et al., Reference Baker, Kearney, Laud and Holmlund2021; Benji-Rabinovitz & Berkovich, Reference Benji-Rabinovitz and Berkovich2021; Cocieru et al., Reference Cocieru, Lyle and McDonald2021; Man & Farquharson, Reference Man and Farquharson2015; Yttermyr & Wennberg, Reference Yttermyr and Wennberg2021). To date there has been an extensive use of what we have called the individual approach of which there have been several different tacks, a couple investigations using of the group-mind approach, as well as a couple qualitative studies. To this end, we encourage more thinking as to CPO’s emergent process addressing the questions of how, where, and when.

Said somewhat differently, without reference to time between events (immediately, seconds, minutes, hours, …) acknowledging that there may be other variables involved, this transformative process might best be understood in terms of three distinct and sequential events. In event one, the target of ownership becomes grounded as ‘mine’ as the individual finds themselves within the object, and it becomes a part of the extended self. In the second event, there is an awareness that the object is not just that of ‘mine’ (a personal phenomenon), but that it exists at the group level and thus there is an ‘ours’ (this is ‘ours’) in association with the object. It is unlikely that a sense of ‘ours’ can exist in the absence of a sense of ‘mine’. Third and finally through interactive dynamics, an emergent phenomenon is created which is more than the sum of the individual attributes. Thus, the construct of CPO is transformed from the individual to the group level and finally the collective sense that the target is ‘ours’ emerges and becomes a part of the group’s extended sense of itself. Thus, we have a group-mind or the collective cognition, blending perspectives (cf. Pierce & Jussila, Reference Pierce and Jussila2010).

In addition, we find ourselves wondering about the time duration of the sense of ownership that accompanies CPO. It is not necessarily uncommon after certain periods of time for the individual to lose interest in what was once prized possession. This raises questions of time: How long do these ownership feelings and effects last? What are among the causes of its deterioration?

To summarize these, we propose the following propositions:

Proposition 1: In the initial stage, individual PO plays a significant role in the perception of ownership.

Proposition 2: In the developmental stage, individual PO and CPO co-exist in the perception of ownership.

Proposition 3: In the mature stage, CPO outperforms individual PO in the perception of ownership.

Methodological issues

The aggregation approach. As we have expressed earlier in the paper, the measurement of CPO in much of the reviewed literature examined individually derived data as the first of multiple steps inquiring about how I or the collective of which I am a part collectively believes (feels). These papers have often utilized the practice of aggregating individual-level data to represent a collective-level construct (James et al., Reference James, Demaree and Wolf1993; LeBreton & Senter, Reference LeBreton and Senter2008). Importantly, there needs to be evidence that all members of the collective possess virtually a similar view (i.e., there is homogeneity of belief) before that becomes the team’s CPO score that subsequently gets associated with the other variables of interest in the study.

There are important considerations when moving from the individual to the group level to remain confident that you are still measuring what you had intended, or accounting for important conceptual differences. Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010) discussed the importance of groups being able to differentiate and distinguish themselves from other groups. This is echoed again by Bliese, Maltarich, Hendricks, Hofmann and Adler (Reference Bliese, Maltarich, Hendricks, Hofmann and Adler2019), who highlight the importance not only of the group members being on the same page, but members of a Group 1 being able to distinguish themselves from members of a Group 2.

To do this, Bliese et al. (Reference Bliese, Maltarich, Hendricks, Hofmann and Adler2019) discuss the importance of ICC, ‘the amount of variance in any one group member’s response that can be explained by group membership.’ ICC highlights the impact of the group, or what comes with being part of the group rather than any one individual. A high ICC(1) suggests that an individual is accurately speaking on behalf of the group, or the shared group experience. Otherwise, it is the sum or average of personal feelings, which is a different construct altogether compared to the group’s perception.

Overall, it is important that not only all members of the collective possess virtually a similar view (homogeneity of belief), but also there should be confidence in differentiating one group/collective from another – between group variance that can be captured by ICC (1). More generally, Chen, Mathieu and Bliese (Reference Chen, Mathieu and Bliese2005) highlight the steps/framework needed to maintain proper conceptualization when going to different levels. Otherwise, the move from individual to collective level is not examining what was intended, as can happen with an aggregate approach.

Challenges of the aggregation approach. The operationalization of aggregating lower-level data to measure a higher-level group-mind or collective cognition will be virtually impossible if the target of ownership is at the macro level, as we have noted before. One could contend that the popular ‘group mind’ approach offers limited utility, as it is primarily useful for comparing numerous small teams or specific groups and poses challenges for empirical applications that examine larger targets of ownership. If the organization is the target of ownership, a study that applies the aggregation approach will need to collect data from multiple individuals in multiple organizations to have a sufficient number of observations, with each organization being one observation. It will become more challenging if the target of ownership is country, region, or a large territory, as demonstrated by Verkuyten and Martinovic (Reference Verkuyten and Martinovic2017) and others who study intergroup conflicts and immigrations to a foreign country.

We also want to bring attention to some insights provided by Verkuyten (Reference Verkuyten2024) in a recent paper. Verkuyten made a similar comment in their recent work, along with a great insight of the potential for bias and social projection: ‘The process of projection implies that what seems to be a CPO mindset (“we collectively agree that this is our, e.g., work product, firm, cultural artifact, neighborhood, territory”) might (partly) reflect individual’s sense of shared ownership (“I feel this is our – e.g., – work product, firm, cultural artefact, neighborhood, territory”)’ (2024: 401). Furthermore, Verkuyten (Reference Verkuyten2024: p. 401) offers a potentially interesting solution:

Specifically, the average CPO score of all group members—the “actual” shared CPO—can be subtracted from the CPO score of each individual group member. This group-mean centering procedure creates individual CPO deviation scores indicating the part of their own feeling that is not shared with their group members, and by definition this deviation is independent of the latter (see Raudenbush & Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002). Thus, a positive deviation indicates a relatively high score for group members own sense of shared ownership, whereas a negative deviation indicates a relatively low score. When the deviation score independently predicts perceived collective ownership (“what other group members think”), this effect suggests false consensus due to projection. In that case group members perception of what other group members think is not only dependent on the actual “group mind” - what the group actually and collectively thinks - but also reflects the projected impact of their unique individual feelings.

Attention to the referent shift approach. There are a handful of reasons why we discourage aggregating individual PO responses to calculate CPO. Aggregation may be a poorer approach compared to referent shift for CPO because the nature across levels (individuals, groups) is not specified, or it is determined to be a certain way without actually being tested (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Mathieu and Bliese2005: 275). For CPO, as an example, there are issues including but not limited to 1) the individual might not have the accurate perception and 2) the individuals within the same group might not align in perception with one another. Overall, it is insufficient to have individuals answer individual PO items, aggregate or take the average of those scores, and label them CPO.

Pierce and colleagues developed a CPO measure that indicates a reference shift, as it had items that used the group as the referent, rather than the individual. Specifically, CPO measurements have had ‘we’ as the referent for the item, rather than ‘I’ used in the individual PO measure. A referent shift is an important approach, where the referent of the ownership is collective ‘we’ or ‘our’ versus individual: ‘I’ or ‘my’. Overall, in moving forward with CPO, we would encourage a referent shift approach, compared to the use of aggregation methods such as consensus of individual PO. CPO is interested in the perception of ownership felt altogether, rather than the ownership felt by each individual individually, the latter of which is more represented by aggregate/consensus, while the former – referent shift. The important thing is capturing a shared perception rather than individual experiences.

The level of homogeneity. Methodologically, for all studies of CPO, we strongly recommend looking at and reporting on the level of homogeneity of responses about ownership. We ask this of all researchers and journal review boards who oversee their work before publication. This call also goes out to those who adopted methodologically the collective or individual approach to the measurement of CPO (James et al., Reference James, Demaree and Wolf1993). Extremely large samples such as those drawn from large regions (e.g., nations) may make this unrealistic. Under such circumstances it is very possible that many respondents do not feel as though they are owners. In such instances, researchers should consider drawing a random sample or more (to enable comparing the degree of homogeneity among the sampled groups) to provide a degree of certainty that a respondent can accurately report how it is that others feel. We also recommend that before CPO research is conducted in the future that researchers examine the writings of Wageman et al. (Reference Wageman, Gardner and Mortensen2012) to see whether or not modifications need to be made to the measurement of CPO and the use of teams as their research focus.

Call for multi-level and multi-method design. If future research intends to integrate CPO with other variables that are at a different level, most likely at the individual level, we suggest that authors apply multi-level analysis approach such as hierarchical linear modeling to capture the effects of variables at different levels of analysis. Additionally, the study of the dynamics of the development of CPO in part can be achieved using a longitudinal design and multiple waves of data collection. Others including Matilainen and Lahdesmaki (Reference Matilainen and Lahdesmaki2021), for example, have suggested that qualitative studies such as interviews and case studies that involve multiple waves of data collection can be a powerful tool for theory (hypothesis) development, as well as a methodological approach to validate the development and dynamics of CPO as described in the Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010) model.

Conclusion

Our objective in this review has been to critically examine the emerging construct of CPO, conceptualized as a unified and shared mindset or a group-level mental model that evolves over time. This review encompasses the conceptual definition of CPO, its theoretical and methodological foundations and extensions, and the empirical literature across disciplines that have incorporated CPO as a core construct and have connected CPO with other theoretical constructs.

We find that the majority of scholarly contributions to the CPO literature have adopted the foundational definition and theoretical framework introduced by Pierce and Jussila (Reference Pierce and Jussila2010). Notably, there has been meaningful theoretical advancement from the perspective of social identity theory. While a limited number of studies have explored CPO through the lens of group cognition such as the group-mind framework proposed by Weick and Roberts (Reference Weick and Roberts1993) or the notion of collective cognition discussed by Gibson (Reference Gibson2001), the predominant approach has been to examine CPO at the individual level within the social identity paradigm. Methodologically, most investigations have employed correlational designs and individual-level measures, with few adopting quasi-experimental or true experimental approaches.

In conclusion, the construct of CPO presents a rich and underexplored domain for future inquiry. The literature remains ripe for further theoretical refinement and empirical validation. We extend an open invitation to scholars to engage with and contribute to the continued development of this promising domain.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2025.10053.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Jon L. Pierce is a Professor of Management and Organization emeritus in the Department of Management Studies, Labovitz School of Business and Economics at the University of Minnesota Duluth. He received his PhD from the University of Wisconsin Madison in management and organizational studies. His research interests focus on the psychology of work and organizations, with a particular interest in psychological ownership and organization-based self-esteem. He twice held a visiting scholar appointment in the Department of Psychology at New Zealand’s University of Waikato, and was named a University of Minnesota Horace T. Morse Distinguished Professor for his contribution to undergraduate education at the University of Minnesota.

Jonathan I. Lee is an Assistant Professor of Organizational Behavior at the Labovitz School of Business and Economics, University of Minnesota Duluth. He received his PhD from Washington University in St. Louis. His research examines the intrapersonal and interpersonal processes through which emotions impact trust repair.

Dahui Li is a professor of management information systems at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs, United States. He received his PhD in MIS from Texas Tech University. His research interests encompass business-to-consumer relationships, online communities, and technology innovation. His research has been published in Decision Sciences, Decision Support Systems, Information & Management, International Journal of Electronic Commerce, Journal of the Association for Information Systems, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Management Science, and elsewhere.