Introduction

Local government is key for how the public interacts with the political system. Even though policy decisions at the national level often have more far‐reaching consequences, it is policy choices at the local level that are most tangible for citizens. Yet, despite the important role that local politics plays in making politics manifest for the public, political scientists have long paid vastly less attention to politics at the local level, resulting in several research gaps. One of these gaps concerns representation at the local level. While there is extensive research on local descriptive representation (Anzia & Bernhard, Reference Anzia and Bernhard2022; Crowder‐Meyer et al., Reference Crowder‐Meyer, Kushner Gadarian and Trounstine2015; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Reingold and Owens2012; Trounstine & Valdini, Reference Trounstine and Valdini2008; Vowles & Hayward, Reference Vowles and Hayward2021), much less work has gone into studying representation beyond descriptive questions. Several studies have investigated the responsiveness of local elites and have generally found that local policy choices reflect public preferences (Einstein & Kogan, Reference Einstein and Kogan2016; Kelleher Palus, Reference Kelleher Palus2010; Sances, Reference Sances2021; Tausanovitch & Warshaw, Reference Tausanovitch and Warshaw2014). These works have compared municipalities to assess whether local public policy is aligned with voter preferences. What is lacking, however, is an understanding of the extent to which the interests of particular voter groups are over‐ or underrepresented in local politics. We tackle this question from the perspective of geographic representation by asking: Do parties represent some districts more than others and what explains potential disparities?

The analysis focuses on a sample of 12 large German cities. Uncovering disparities in geographic representation is especially concerning in urban politics, as large cities tend to be composed of sociostructurally homogeneous units with substantial variation between districts (Alisch, Reference Alisch, Huster, Boeckh and Mogge‐Grotjahn2018; Friedrichs & Triemer, Reference Friedrichs and Triemer2009). Consequently, geographic representation in large cities tends to coincide with the representation of social strata, making deviations from the ideal of equal representation a normative concern.

The study speaks to a broader research on geographic representation in party‐centred political systems (Alemán et al., Reference Alemán, Pablo Micozzi and Ramírez2018; Nagtzaam & Louwerse, Reference Nagtzaam and Louwerse2023; Sozzi, Reference Sozzi2016; Zittel et al., Reference Zittel, Nyhuis and Baumann2019) by adding two important perspectives. First, existing work on geographic representation has often focused on representation in national politics, where legislators appeal to comparatively large electoral districts, while we lack comparable evidence on geographic representation in local politics (but see Harjunen et al., Reference Harjunen, Saarimaa and Tukiainen2023). Beyond the abstract normative ideal of equal representation in local politics, it is likely that voters are particularly mindful of whether the interests of their immediate surroundings are represented in the political process (McCartan et al., Reference McCartan, Brown and Imai2024). Second, existing research has mostly addressed geographic representation from the perspective of personal vote seeking, while disregarding party rationales for geographic representation.

Empirically, we analyse geographic appeals in 10,189 parliamentary questions that were submitted in 12 German city councils over the course of one electoral term. To gauge geographic representation, we employ a dictionary approach that goes beyond the current state of the art. Whereas most current work on geographic representation relies on dictionaries that only contain the names of the municipalities in a district or some variant thereof (Geese & Martínez‐Cantó, Reference Geese and Martínez‐Cantó2023; Kartalis, Reference Kartalis2023; Nagtzaam & Louwerse, Reference Nagtzaam and Louwerse2023; Russo, Reference Russo2021; Sanches & Kartalis, Reference Sanches and Kartalis2024), we assemble dictionaries that contain a more expansive set of geographic markers to get a better sense of the varied ways in which councillors appeal to voters. Specifically, we rely on geolocated data from Wikipedia and OpenStreetMap to automatically generate dictionaries containing features such as street names, sights, businesses, and buildings, in addition to administrative units which should be particularly important for understanding patterns of geographic representation in local politics.

The results suggest that geographic representation is a key feature of local politics, as nearly half of the questions contain a geographic reference. This is a considerably higher value than is commonly observed in national politics. Furthermore, geographic representation in local politics aligns with electoral incentives, as parties frequently appeal to their electoral strongholds. This effect is particularly pronounced when the voter base of a party is highly localized. Parties also engage more in geographic representation when the electoral system promises a more immediate pay‐off from such behaviour.

Geographic representation in party‐centred political systems

Research on representation is dominated by two contrasting models, the dyadic and the collective model of representation (Powell, Reference Powell2000). The dyadic model is characteristic of majoritarian electoral systems, where individual legislators represent geographically defined constituencies. Collective representation is the dominant model in proportional electoral systems, where parties are thought to represent socially defined voter groups.

While the two models constitute stylized accounts of politics, there are empirical regularities in proportional and majoritarian systems that speak to the differences between the two models. One of the most notable differences is the level of unity in legislative voting (Soberer, Reference Sieberer2006). As parties are considered the agents of representation in proportional systems, the norm of voting with the party is more internalized – and more strictly enforced if necessary. Consequently, while we can readily identify the effects of constituency preferences on legislator voting in highly dyadic systems like the United States (Bishin, Reference Bishin2000; Butler & Nickerson, Reference Butler and Nickerson2011; Miller & Stokes, Reference Miller and Stokes1963; Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, Brady, Brody and Ferejohn1990), constituency effects on legislator votes are a more marginal phenomenon in European proportional systems (Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2010).

Yet even though constituency effects on legislator voting are rare in systems characterized by the collective model of representation, voters in such systems are sure to hold geographically defined preferences in addition to their socially defined ones and would like to see those interests represented (Jankowski, Reference Jankowski2016; Schulte‐Cloos & Bauer, Reference Schulte‐Cloos and Bauer2023; Velimsky et al., Reference Velimsky, Block, Gross and Nyhuis2024). Research has highlighted a variety of ways in which geographic interests are fed into the political process in party‐centred political systems. The common feature of the various strategies for representing geographic interests in proportional systems is that parties are willing to tolerate them only when they do not damage public perceptions of party unity, for example, through constituency service (André & Depauw, Reference André and Depauw2013, Reference André and Depauw2018; Bradbury & Mitchell, Reference Bradbury and Mitchell2007; Itzkovitch‐Malka, Reference Itzkovitch‐Malka2021), pork barrelling (Catalinac & Motolinia, Reference Catalinac and Motolinia2021; Gschwend & Zittel, Reference Gschwend and Zittel2018; Stratmann & Baur, Reference Stratmann and Baur2002), and non‐binding legislative instruments, such as parliamentary questions (Martin, Reference Martin2011b; Russo, Reference Russo2011).

Parliamentary questions in particular are a useful tool for representing voter interests in the parliamentary process. Conventionally conceived of as a tool for information gathering and executive control (Bailer, Reference Bailer2011), there is now a rich literature highlighting how parliamentary questions are used for political representation, both in terms of socially (Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2011; Saalfeld & Bischof, Reference Saalfeld and Bischof2013) and geographically defined constituencies (Alemán et al., Reference Alemán, Pablo Micozzi and Ramírez2018; Nagtzaam & Louwerse, Reference Nagtzaam and Louwerse2023; Sozzi, Reference Sozzi2016). One of the main benefits of parliamentary questioning over other legislative instruments is that they are unconstrained by the parliamentary agenda, allowing legislators to raise a varied set of issues (Martin, Reference Martin2011a). What is more, parliamentary questions are available to all parties, setting them apart from majority‐dominated instruments like targeted spending. Parliamentary questions are also more useful for representation than constituency service, as the case‐by‐case nature of constituency service makes it difficult to address general grievances, while also being less visible to the electorate.

Despite the extensive work on political representation through parliamentary questions, there are notable gaps in current research. Previous research has often studied geographic representation in national politics, thus focusing on comparatively large electoral districts, while disregarding representation at smaller scales, which are characteristic of local politics (but see Harjunen et al., Reference Harjunen, Saarimaa and Tukiainen2023). Second, existing work has typically studied geographic representation from the perspective of personal vote seeking (cf. Carey & Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995), where individual legislators use geographic appeals to build a personal brand to ensure their re‐election. While this perspective is not unwarranted given that the right to question the executive is typically granted to individual legislators, it has overlooked that there can be a collective rationale for geographic representation through non‐binding legislative instruments. Especially in proportional systems, parties should have an interest in letting their representatives appeal to geographically defined constituents to raise their collective electoral prospects, particularly when such appeals are not damaging to party unity. Consequently, we aim to map the party‐level rationale for geographic representation, where parties are expected to collectively appeal to certain districts.

The party rationale for geographic representation in local politics

By focusing on national politics, existing research on geographic representation has arguably looked for geographic appeals in places where they are least likely to occur, as national politics is often about abstract policy. While the impact of specific policies may differ between electoral districts, it is not obvious that legislators would explicitly mention their districts in fighting for or against a particular policy. This stands in stark contrast to decision‐making at the local level, where debates will often be about geography, for example, when councillors discuss infrastructure projects. This implies that we should expect geographic references to occur much more frequently in local politics than in national politics, as it is often impossible to discuss city politics without mentioning geography, making an analysis of geographic representation in local politics all the more worthwhile.

Yet, what does it mean for councillors to address a particular area in their parliamentary questions? We assume that geographic references predominantly entail an effort to represent the interests of a localized constituency. While geographically targeted questions may focus on desirable infrastructure projects, such as building a new park or renovating a school, it is more likely that questions address unwanted issues such as areas subject to crime or delays in public projects. Yet, in raising such issues, councillors still represent citizens’ interests by trying to make the city administration aware of a problem in the hope that they can provide relief.

While it is certainly conceivable that some geographic references are not welcomed by citizens, say, when a councillor highlights the need to expand a landfill in a particular district, in practice, unwanted references are far less likely as they go against the electoral rationale of parliamentary questioning. Particularly when studying an optional legislative instrument like parliamentary questions, it is unlikely that legislators will go out of their way to take an unpopular stance, when they could also push for an unpopular policy behind the scenes. It is therefore reasonable to expect that most geographic references in parliamentary questions are in fact desirable geographic appeals.Footnote 1

Having suggested that most geographic references are desirable from the point of view of constituents, we need to examine what motivates geographic appeals. We expect that there are essentially two, not mutually exclusive, factors. Efforts to represent the interests of particular districts may reflect a sincere desire on the part of councillors to highlight the concerns of particular citizens. More than in national politics, local councillors will often be personally affected by council decisions, such that the interests of their constituents may coincide with their own. We also expect the hope for an electoral reward to motivate geographic appeals. Just like in national politics, individual and collective re‐election concerns will be the primary drivers of political behaviour in local councils (Bäck, Reference Bäck2003; Debus & Gross, Reference Debus and Gross2016; Otjes et al., Reference Otjes, Nagtzaam and Well2023).

The electoral value of including geographic appeals in parliamentary questions depends on whether they are perceived by the public. There are two plausible mechanisms for how voters become aware that parties engage in geographic representation. First, parties should frequently engage in geographic representation in matters of infrastructure development. It seems reasonable that interested citizens will pay close attention to whether their needs and grievances are being voiced in the city council, especially since infrastructure projects often prove controversial in the affected neighbourhoods. Second, while local newspaper circulation has been declining (Ellger et al., Reference Ellger, Hilbig, Riaz and Tilmann2024), large cities are still frequently served by at least one local newspaper, and parties can be expected to try to highlight their efforts to represent local communities in local news coverage. At the same time, research on national politics has found that political actors overestimate the willingness of the public to pay attention to their efforts (Soontjes, Reference Soontjes2021) and there is no reason to assume that the same should not also be true for council members.

Based on these propositions, it is possible to formulate expectations about geographic representation in local councils and to identify factors that should increase the likelihood of parties representing specific districts, resulting in predictable deviations from equal representation. As a baseline, we expect parties to appeal more frequently to their electoral strongholds than to areas where they have performed poorly. Collectively speaking, it is reasonable for parties to voice the interests of areas where their voter potential is high to improve their re‐election chances. Beyond the collective electoral rationality, party representatives on the council are also more likely to reside in areas that are party strongholds (Górecki et al., Reference Górecki, Bartnicki and Alimowski2022; Schulte‐Cloos & Bauer, Reference Schulte‐Cloos and Bauer2023), such that at least some councillors would feel personally motivated to represent the interests of their electoral strongholds. This latter point also highlights how individually rational behaviour, whether electorally or personally motivated, can result in party‐level deviations from equal representation. We can summarize these arguments as follows:

H1: Parties are more likely to represent areas where they are electorally strong than where they are electorally weak.

One context factor that should make geographic appeals particularly likely is a highly localized voter base. A voter base is highly localized when the voters of a party are concentrated in a few districts, that is, when a party wins a large share of its votes in a few districts, resulting in a large differential between the district vote share and the city‐wide vote share. When parties receive most of their votes from a few districts, it is easier for them to localize their appeals. Conversely, when their vote share is similar across districts, parties are confronted with difficult trade‐offs. While geographic appeals by parties with a widely dispersed voter base necessarily mean not representing other districts, potentially upsetting parts of their electorate, such considerations are less pressing for parties with a localized support base. We should therefore expect the effects of electoral strongholds to be more prominent when parties have a localized voter base.

H2: Parties are more likely to represent areas where they are electorally strong when their voters are localized than when their voters are dispersed.

While the previous two expectations are partially based on electoral rewards, the institutional context should impact the likelihood of such a reward. One feature of electoral systems that is particularly relevant for whether parties can expect an electoral reward from geographic representation is whether elections are run using electoral districts. Even though parties should pay more attention to their electoral strongholds whether or not elections are run using electoral districts, we expect that parties engage more in geographic representation across the board when the payoffs from geographic representation are more evident to parties. In other words, while parties are expected to include more geographic appeals in their parliamentary questions under conditions of voting in electoral districts, we nonetheless expect more appeals to their electoral strongholds, leading us to expect the following:

H3: Parties are more likely to engage in geographic representation when electoral systems contain electoral districts than when electoral systems do not.

Data and methods

In the following, we first present the case selection and discuss the data generation mechanism. Next, we describe the coding of geographic appeals in local parliamentary questions. Finally, we discuss the operationalization of the variables.

Case selection and data generation

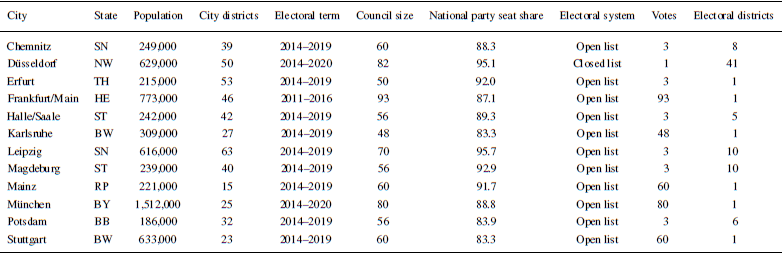

To assess the level and the determinants of local geographic representation, we analyse patterns of parliamentary questioning in German city councils. We focus on large German cities, defined by population sizes over 100,000, which provides several advantages for an analysis of local geographic representation. Politics in German city councils is fairly professionalized with high levels of intra‐party coordination and party‐centric interactions between the councillors (Reiser, Reference Reiser2006; Stecker, Reference Stecker, Tausendpfund and Vetter2017), thus mimicking politics at the state and national levels. The party‐centric nature of German city politics is partly a function of the comparatively large council sizes, ranging from 48 to 93 in our sample (see Table 1). Coordinating this many councillors requires a more elevated function of the party organizations (Egner, Reference Egner2015). The party‐centredness of German city politics is also evidenced by the fact that the overwhelming majority of council seats are won by national parties (Nyhuis et al., Reference Nyhuis, Velimsky, Block and Gross2022; Pollex, Block, Gross, Nyhuis, et al., Reference Pollex, Block, Gross and Nyhuis2021; Vetter & Kuhn, Reference Vetter, Kuhn, Haus and Kuhlmann2013).

Table 1. Information on case selection

Abbreviations: BB, Brandenburg; BW, Baden‐Württemberg; BY, Bayern; HE, Hessen; NW, Nordrhein‐Westfalen; RP, Rheinland‐Pfalz; SN, Sachsen; ST, Sachsen‐Anhalt; TH, Thüringen

One indicator for the high level of professionalization of German city politics is the fact that all councillors are equipped with the right to address questions to the local public administration. Most state laws governing the institutional structure of local politics explicitly mention the right of questioning and that right is enshrined in all council rules of procedure.Footnote 2 As a practical matter, parliamentary questions are frequently used, with hundreds of questions being submitted per legislative term in all cases in our sample, suggesting a high degree of formalized interaction and professionalization.

One additional benefit of studying German city politics is that the individual cases exhibit a lot of similarities, such as the party system and the general institutional framework, while differing on key independent variables, such as the electoral system. Specifically, while all electoral systems in our sample feature some form of personalized vote, only some elections are conducted using electoral districts, which we expect to be a key driver of geographic representation.

Data on parliamentary questions were collected from the council websites for one full electoral term, ranging from 5 to 6 years. We were able to gather all the necessary data for 12 German cities. Limiting factors were the availability of electoral data at the district level as well as shapefiles for the automated coding of the parliamentary questions. While the case selection does not constitute a random sample, it covers a lot of the potentially relevant variations, for example, regarding states, and therefore the different electoral systems, covering both East and West German states, as well as the wealth and size of municipalities.

We restrict the analysis to parliamentary questions by council parties that are part of the national party system, that is, Alternative for Germany (AfD), Christian Democratic Union (CDU)/Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU), Free Democratic Party (FDP), Alliance 90/The Greens, Social Democratic Party (SPD), and The Left. This restriction results in little loss of information, as the local party systems are highly nationalized (cf. Kjaer & Elklit, Reference Kjaer and Elklit2010a, Reference Kjaer and Elklit2010b), with close to 90 per cent of the council seats being won by national parties. What is more, as we are interested in the geographic representation of party organizations, little can be learned from studying the efforts of individual councillors with no party affiliation.

In total, 10,189 questions were submitted by the seven parties in the 12 cities in the period of investigation. Of these, 6,948 were submitted by one councillor, 2,344 by two or more members, and 897 questions were submitted by one or more party organizations. The vast majority of questions were submitted by a single party, either individually or collectively, with less than 2 per cent of questions being submitted by members from more than one party group. All questions were aggregated to the signing party, as even individually submitted questions show whether parties collectively make an above‐average effort to raise specific local interests in council politics.Footnote 3 Questions submitted by multiple parties were assigned to all signatories.

Coding of the data: Geographic appeals

To understand geographic representation through parliamentary questions, we automatically code whether a city district is referenced in a question. We rely on the district boundaries as defined by the city administrations. The districts are typically defined to reflect natural boundaries and enclose established communities. One challenge for the analysis is that city administrations define their own district boundaries. While this ensures that district boundaries coincide with local communities, there are no firm guidelines regarding the number of layers for subdividing cities, such that some cities operate with just one layer, while others aggregate small districts into larger districts, where the upper layers tend to serve statistical purposes rather than being natural points of identification. In general, larger cities tend to have more layers than smaller cities. For the analysis, we tried to aim for the smallest layer possible to ensure more fine‐grained results while relying on districts that residents would naturally identify with. The choice of layer was sometimes governed by data availability, such as election results at the district level. Empirically, our cases range from 15 to 63 city districts with an average of 37.9 districts per city and a standard deviation of 14.0. On a more technical level, the number of districts is sufficiently low to ensure a reasonable number of district mentions in the parliamentary questions.Footnote 4

For the automated coding of the questions, we rely on a dictionary approach, as is common in research on geographic representation (Alemán et al., Reference Alemán, Pablo Micozzi and Ramírez2018; Geese & Martínez‐Cantó, Reference Geese and Martínez‐Cantó2023; Russo, Reference Russo2021). We generate one dictionary for each of the 455 districts in the 12 cities in our sample and check whether terms that can be associated with a district are mentioned in the questions from the relevant city. We go beyond the state of the art by building more elaborate dictionaries for gauging geographic representation than is currently done in the literature. Whereas early attempts were at times limited to mentions of district names and variants thereof (Kellermann, Reference Kellermann2016), more recent studies have relied on extensive databases of geocoded data to identify geographic representation (Alemán et al., Reference Alemán, Pablo Micozzi and Ramírez2018; Viganò, Reference Viganò2024; Zittel et al., Reference Zittel, Nyhuis and Baumann2019). Although such efforts constitute a step forward in research on geographic representation, public databases are often limited to natural and administrative markers, while missing important markers such as businesses, sights, or notable buildings, which should play an important role in city politics and in councillors’ efforts to represent their constituents. To include the latter types of categories, we rely on geocoded data from Wikipedia, which provides a rich data source of geographic markers, which are typically missing in public databases.

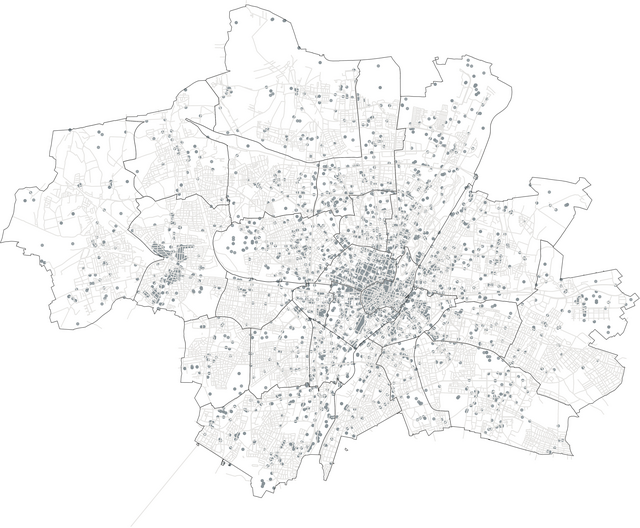

To automatically assemble the dictionaries, we start with shapefiles containing city and district boundaries that were gathered from the city administrations. Next, we collect a database of geolocated markers from the German Wikipedia, containing both the label of the marker as well as the associated latitude and longitude. To this, we add geolocated data from a public database containing all streets in the respective city based on OpenStreetMap.Footnote 5 Then, we compare whether the geolocation of a marker falls inside the boundaries of a city district, in which case it is added to the district dictionary. Some markers, streets in particular, can span across multiple districts and are thus added to multiple dictionaries. Figure 1 presents an example of the geolocated data for the city of Munich. Examples of parliamentary questions with and without geographical appeals are provided in the Online Appendix.

Figure 1. Geographic markers in the city of Munich.

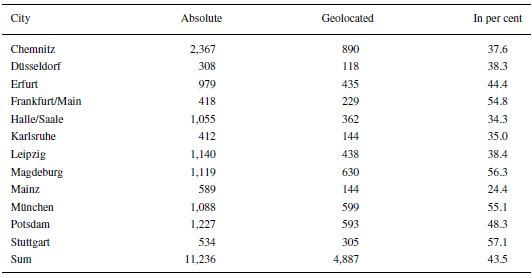

To code the parliamentary questions, we check whether any of the terms in the cities’ district dictionaries are referenced in the parliamentary questions. The result of this operation is presented in Table 2. One notable feature of the data is the comparatively high number of questions containing geographic references. In some cities, more than one out of every two questions contains at least one such reference. Compared to most research on geographic representation in national politics, these figures are exceptionally high (Papp, Reference Papp2016; Russo, Reference Russo2021; Zittel et al., Reference Zittel, Nyhuis and Baumann2019), although some studies have observed similarly high localness figures even at the national level (Martin, Reference Martin2011b; Russo, Reference Russo2021). While part of this finding can likely be attributed to the use of more extensive dictionaries than previous research, the figures align with the notion that local politics is overwhelmingly about concrete infrastructure decisions and not about abstract policy in the way that state and national politics is (Block, Reference Block2024b; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Nyhuis, Block and Velimsky2024).

Table 2. Overview of the data

Note: The column ‘Absolute’ contains the number of questions that were submitted over the course of one legislative term. Questions are counted more than once when they were signed by more than one council party. The column ‘Geolocated’ provides the number of questions that contain at least one geographic reference. The column ‘In per cent’ provides the share of questions containing at least one reference to a district.

Operationalization of dependent, independent and control variables

To assess whether parties mention some districts more than others, we model the number of parliamentary questions by a council party that references a particular city district over the course of one legislative term. The dependent variable is calculated by checking how many questions by a council party mention at least one term in one of the district dictionaries of the relevant city. One question can contain references to multiple districts. This is obviously the case when a term occurs in multiple dictionaries. For the purpose of labelling a question as referencing a district or not, we do not distinguish between questions that mention one term or several terms from a district dictionary. The labelling process is repeated for all parties and all relevant district dictionaries, resulting in 6 (parties) × 455 (city districts) = 2730 observations. The number of observations in the empirical analysis is slightly lower than the theoretical maximum, since not all parties are represented in all city councils and some city districts, such as industrial areas, are not populated. As there are no election results for these districts, they are excluded from the analysis.

In the theoretical account, we have argued that parties focus their representational efforts on city districts with strong electoral support (H1). The most straightforward way to test this proposition is through parties’ vote shares in the city districts,Footnote 6 where we expect a positive effect on the number of geographic references. We further argued that the effect of the district vote share may be contingent on parties’ general electoral support in that parties would be especially motivated to focus on specific districts when their voter base is localized (H2). This can be tested by adding parties’ city‐wide vote share to the model and estimating an interaction effect between the district vote share and the city vote share. We expect that the number of geographic references go up under conditions of strong electoral support in a district but poor city‐wide electoral support.

A slightly different way to model this latter expectation is to calculate the difference between the district vote share and the city‐wide vote share and to include this difference in the model. We expect that as the delta between the two vote shares goes up, so will the number of geographic references to districts where parties have a strong surplus in electoral support. One additional benefit of modelling this difference is that it does away with different party‐specific baselines of electoral support. For example, a district vote share of 15 per cent will typically constitute a strong electoral result for the FDP, while it would be considered a poor outcome for the CDU. Calculating the differences between parties’ district results and their city‐wide electoral results places the parties on a common metric, where a value of zero constitutes an average district result.Footnote 7

While parties can always hope to be rewarded electorally for representing their voters, the likelihood of a payoff differs by institutional context. We argued that electoral systems featuring electoral districts should increase the incentives to engage in geographic representation, as the potential payoff from such behaviour is more apparent to parties (H3). Therefore, we include a variable indicating whether the local electoral system features electoral districts, expecting that the number of geographic references is higher when voting is done in electoral districts.

We control for the size of the district dictionaries, as larger dictionaries increase the likelihood that parties mention one of the terms in their parliamentary questions. On average, the dictionaries contain 113 geographic markers with a sizeable standard deviation of 114.3. One reason for the large variation is that while inner‐city districts tend to be smaller, they contain a higher number of notable markers, such as buildings or sights. This feature of the data is evident in Figure 1. We expect that larger dictionaries increase the number of geographically targeted questions.

While the size of the district dictionaries may thus be considered a technical control, more frequent mentions of central districts could also represent a substantive effect. To disentangle the two possibilities, we add the distance to the city centre as a further control. Based on the shape files, we calculate the centroids of the city districts, along with the centroid of the central district, as indicated by the district name, before calculating the distance between the district centroids and the centroid of the city centre. In case two districts were labelled as inner‐city districts, such as Centre South and Centre West, we merged their geometries and used the centroid of the resulting artificial district to calculate the distances.

We also control for the length of the electoral term, as longer terms provide parties with more opportunities to make geographic appeals.

Finally, we add party fixed effects as summary controls for party‐level idiosyncrasies. An alternative model specification is presented in Table A1 in the Online Appendix, where we control for the government status of parties rather than party fixed effects, as this arguably constitutes the most important party‐level effect to control for.

To analyse the number of questions referencing a district, we estimate negative binomial models as the data are subject to overdispersion. We add random intercepts at the city level to account for different levels of parliamentary questioning, geographic representation, and other city‐specific idiosyncrasies, such as local political culture.Footnote 8

Empirical analysis

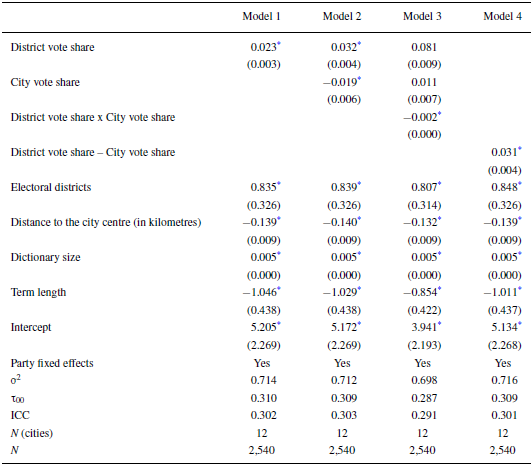

The results from four multilevel negative binomial models are presented in Table 3. Model 1 explains the number of geographically targeted questions with the district vote share, Model 2 adds the city vote share, and Model 3 the interaction between the two. Model 4 contains the difference between the district vote share and the city vote share. All models also include an indicator of whether council elections are run using electoral districts.

Table 3. Model results

Note: Dependent variable: Number of geographic references by a party to a city district in their parliamentary questions over the course of one legislative period. Displayed are the coefficients from negative binomial models with random intercepts at the city level. ICC, Intra‐class correlation.

* p < 0.05.

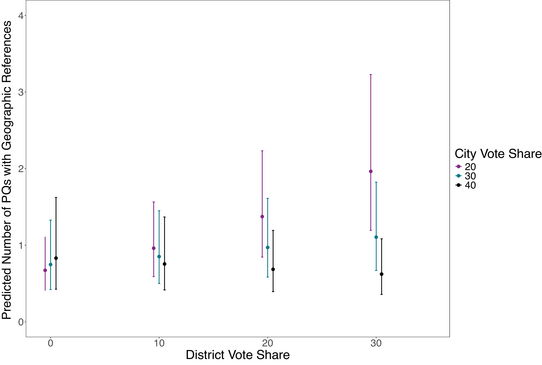

All hypothesized effects are correctly signed and significantly different from zero at conventional levels of statistical significance. First, there is a positive effect of the district vote share on council parties’ efforts to represent city districts, lending support to the first hypothesis. Parties represent areas where they are electorally strong more than areas where they are electorally weak. The interaction term between the district vote share and the city vote share is negative and statistically significant. To turn this result into easy‐to‐understand quantities, Figure 2 presents model predictions for several scenarios based on Model 3 in Table 3. The figure displays the predicted number of references to the districts for several combinations of district vote share and city vote share. The predictions are in line with the expectations. We observe the greatest effort to represent city districts when the electorate is localized, that is, when the city‐wide vote share is low, but the district vote share is high. Such an interaction is virtually non‐existent when parties’ city‐wide vote share is high. It is worth mentioning that while the predicted values of geographically targeted questions in Figures 2 and 3 are always in the single digits, the analysis is at the district‐by‐party level, meaning that these figures reflect sizeable levels of geographic representation overall.

Figure 2. Predicted values based on Model 3 in Table 3.

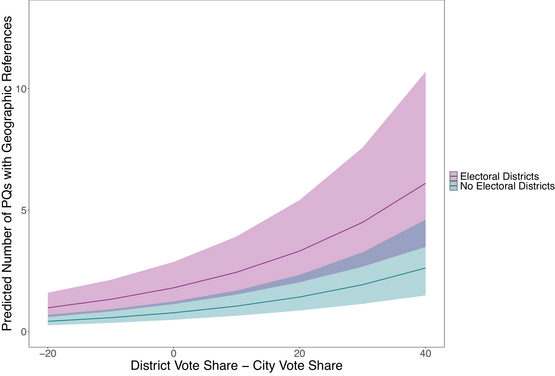

Figure 3. Predicted values based on Model 4 in Table 3.

A different way of looking at the combined effect of city vote share and district vote share is presented in Model 4, which models the frequency of geographically targeted questions as a function of the difference between the district vote share and the city vote share. Again, the effect is in line with expectations, as the predicted number of questions referencing a district goes up when the delta between the district vote share and the city vote share increases.

We also find that parties are significantly and substantially more likely to use geographic appeals when voting is done in electoral districts. It is worth reiterating that we are estimating multilevel models with random intercepts at the city level, such that the effect of the electoral district variable does not simply capture differences between the cities.

Again, to get a better sense of the effect sizes, Figure 3 depicts the predictions based on Model 4 in Table 3 across a range of values for the vote share delta for cities that elect their councillors in electoral districts and those that do not. While both slopes point upwards as the difference between the district vote share and the city vote share goes up, the level of the predictions is notably higher when elections are conducted using electoral districts.

Beyond the variables of interest, three additional observations stand out in the models in Table 3. First, as expected, the size of the district dictionaries exhibits a significant positive effect on the number of geographic references, while the distance to the city centre exhibits a negative effect. We can thus conclude that while the size of the dictionaries does have mechanical effects on the number of geographic questions, parties are also substantively more likely to address more central districts.

Second, it is worth noting how much of the variation in the dependent variable can be explained at the city level. The intra‐class correlation coefficients suggest that well over a third of the variation in the dependent variable can be traced back to the city level. There are likely unobserved city‐level factors beyond the electoral system which are drivers for the different levels of geographic representation. One possible explanation for the considerable variation at the city level might be differences in parliamentary culture where the competitors collectively differ in how they engage in geographic representation. This proposition aligns with the large differences in the number of parliamentary questions in Table 2, where the number of questions is unrelated, if not inversely related, to the city or council sizes.Footnote 9

Conclusion

While research has clearly established that parties in proportional systems engage in geographic representation through non‐binding legislative instruments such as parliamentary questions, the willingness of parties to represent their constituents geographically has almost exclusively been investigated for national politics. What has been missing is evidence for patterns of geographic representation in local politics, where this type of representation should play an even more prominent role than in national politics. By analysing geographically targeted parliamentary questioning in 12 German city councils, we are among the first to shed light on this question.

Our results can be summarized as follows. First and foremost, we find that council politics is highly localized, with nearly one out of every two questions containing a geographic reference. This underscores the notion that unlike national politics, where much of the debate is about abstract policy, council politics is about concrete policy decisions. We also find consistent evidence that local competitors are strategic about which areas to represent, as they are more likely to appeal to their electoral strongholds. This behaviour is especially pronounced for parties whose electorate is highly localized. Finally, parties are more likely to engage in geographic representation when the electoral system incentivizes them to do so. On a more general level, we can thus summarize that electoral incentives shape political behaviour in council politics and that these incentives result from the same institutional features that impact national political behaviour. This adds to the growing literature on the similarities between local politics, at least in larger municipalities, and regional and national politics in European multi‐level democracies (Högström & Lidén, Reference Högström and Lidén2023; Otjes, Reference Otjes2024).

While the results undoubtedly speak to a gap in current research, further research is needed to assess the generalizability of the results. German city councils are highly professionalized. The right to ask questions and their systematic publication by local administrations, along with the professionalization of local parties and the widespread use of parliamentary questions were prerequisites for this study of geographic representation in local politics. It is not obvious that the same conditions hold for smaller municipalities or in other countries. As researchers have only recently begun to investigate patterns of parliamentary questioning in local politics (Block, Reference Block2024a; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Nyhuis, Block and Velimsky2024; Otjes et al., Reference Otjes, Nagtzaam and Well2023), it is difficult to judge whether similar studies could be carried out for other cases and, if so, what the results might be. This is not to suggest that geographic representation is not a feature of local politics elsewhere, it may simply not be as evident or it may be on display in other venues, such as targeted spending on specific districts.

Local parliamentary questions provide a rich data source that can help answer a number of important research questions. One obvious extension of this study could address the question whether some districts are better represented in city politics than others. That question is subtly different from the question that was analysed here. Whereas we asked whether parties differ in their efforts to represent certain districts and what factors can explain those differences, one might also wonder whether council parties collectively represent certain districts more than others. In some regard, observing collective imbalances would be even more troublesome than observing imbalances at the party level. This is particularly true when we recall that city districts in large municipalities tend to constitute sociostructurally homogeneous units that strongly differ between the districts (Alisch, Reference Alisch, Huster, Boeckh and Mogge‐Grotjahn2018; Friedrichs & Triemer, Reference Friedrichs and Triemer2009). Tying into a broader research on disparities in the representation of social classes (Carnes, Reference Carnes2013; Elsässer et al., Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2021; Gilens, Reference Gilens2012), one might hypothesize a representational deficit for less well‐off districts. One factor that should play a key role in this regard is district turnout, given the debate on the link between (non‐)voting and representation (Griffin & Newman, Reference Griffin and Newman2005; Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1997). Overall, we can thus summarize that local politics and the data sources introduced here hold a lot of promise for research going forward.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this paper was presented at the Local Party Politics (LoPaPol) workshop in Ghent 2024. We thank all participants for their valuable comments and suggestions, especially Alistair Clark. We are grateful to Louis Drexler, Hanna Hieronymus, Anna Missy, Aaron Reudenbach, Janina Schindler, Sinéad Thielen and Katia Werkmeister for excellent research assistance.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data Availability Statement

The replication material for the final analyses can be found in the following repository: https://osf.io/bhzc2/?view_only=2c8615d7f09e48a490c76109ffe0c2d1

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: