Introduction

Anomalous origin of one pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta, previously termed hemitruncus arteriosus, is a rare congenital malformation with an incidence of approximately 0.12%. Reference Pumacayo-Cárdenas, Jimenez-Santos and Quea-Pinto1 In approximately 70–80% of anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta cases, the right pulmonary artery anomalously originates from the ascending aorta, while in the remaining cases, the left pulmonary artery is involved. Reference Garg, Talwar, Kothari, Saxena, Juneja and Choudhary2 Without timely surgical correction, anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta frequently leads to early-onset segmental pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, and death—up to 70% of untreated infants die within the first year. Reference Haywood, Chakryan, Kim, Boltzer, Rivas and Shavelle3 Most patients are diagnosed during the neonatal and infantile periods, necessitating urgent anatomical correction surgery for the abnormal pulmonary artery branch.

The diagnosis of newly identified patients during adolescence and adulthood continues to be based on rare case reports. For patients diagnosed at a late stage, the main concern is to evaluate the patient for operability. Conventional invasive haemodynamic assessment is insufficient for determining reversibility. Reference Tamimi and Mohammed4 In such patients, there is a growing need to integrate multimodal imaging findings—such as echocardiography, CT angiography, cardiac MRI, and nuclear medicine techniques—to provide a comprehensive interpretation of the underlying patient-specific pathophysiology and to guide clinical decision-making. Reference Gupta, Choubey, Kumar, Patel and Airan5 An 11-year-old patient with anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta who underwent 2D phase-contrast cardiac MRI guided reversibility assessment will be presented.

Case presentation

An 11-year-old girl was referred to the paediatric cardiology outpatient clinic with complaints of progressive fatigue. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed mild dilation of the left heart chambers; however, the origin of the right pulmonary artery could not be clearly delineated. CT angiography demonstrated an anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta, while the left pulmonary artery originated normally from the main pulmonary artery (Figure 1a–1c). Additionally, both lower lobes showed disproportionate enlargement of the pulmonary arteries relative to the accompanying bronchi, suggestive of segmental pulmonary hypertension

Figure 1. ( a ) Contrast-enhanced cardiac CTA showing the AORPA (red arrow) from the ascending aorta and the normal origin of the left pulmonary artery from the main pulmonary artery (blue arrow). ( b ) Axial CT image demonstrating interstitial thickening in the right lung (black arrow), consistent with microvascular congestion. ( c ) Volume-rendered 3D reconstruction visualising the right pulmonary artery arising directly from the ascending aorta (red arrow). AORPA = anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta.

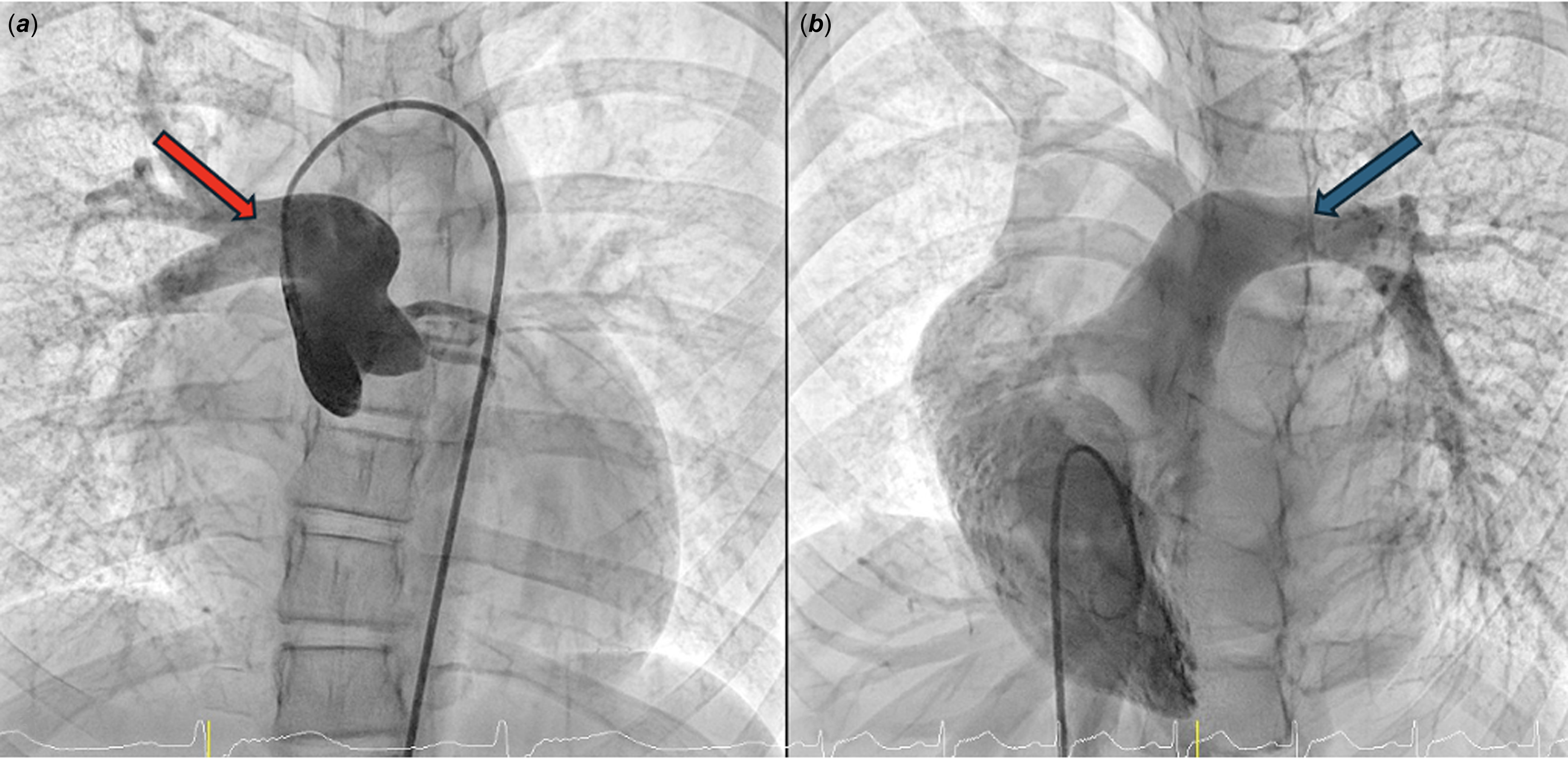

Diagnostic cardiac catheterisation was performed to evaluate the pulmonary circulation further and confirm the diagnosis. Angiography confirmed the anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta (Figure 2a and 2b). Haemodynamic measurements revealed the following pressures (in mmHg): main pulmonary artery: 38/12 (23), left pulmonary artery: 34/13 (25), right pulmonary artery: 98/55 (75), and right ventricle 38/3, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 16/15 (14) mmHg, and ascending aorta pressure was measured as 98/57 (73). Shunt and resistance calculations revealed a pulmonary-to-systemic flow ratio (Qp/Qs) of 0.75 and a pulmonary vascular resistance-to-systemic vascular resistance ratio of 1.25.

Figure 2. ( a ) Angiographic image demonstrating the anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta, following a posterior and medial course(red arrow). ( b ) Right ventricular injection illustrating the continuity between the main pulmonary artery and the left pulmonary artery (blue arrow).

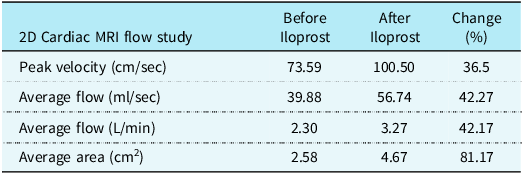

Since the haemodynamic study alone was inconclusive for operability assessment, a non-invasive vasoreactivity test using inhaled iloprost during 2D phase-contrast cardiac MRI was planned. Initially, a baseline flow assessment of the anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta was performed using 2D phase-contrast cardiac MRI. Subsequently, the patient received inhaled iloprost at a dose of 2.5 mcg, and serial 2D flow MRI acquisitions were obtained at 2-minute intervals over a 10-minute period. The peak flow response observed during this interval was used to evaluate vascular reactivity. A 42% increase in mean flow rate at the peak response was noted, suggesting preserved pulmonary vascular reversibility in the right pulmonary artery (Table 1). In the pre-iloprost phase, flow velocity in the right pulmonary artery increased from 73.5 cm/s to 100.5 cm/s, and flow volume increased from 22.5 ml to 32.4 ml. In the left pulmonary artery, flow velocity increased from 125.8 cm/s to 141 cm/s, while flow volume decreased from 57.3 ml to 50.2 ml. This partial reduction in left pulmonary artery flow volume may reflect a preferential redistribution of flow towards the right pulmonary artery. However, due to the subjective and experimental nature of this method, it was decided to complement the evaluation with a lung biopsy for definitive assessment.

Table 1. Quantitative 2D phase-contrast cardiac MRI flow parameters in the right pulmonary artery before and after inhaled iloprost administration

Given the long-term morbidity and mortality linked to the condition, a lung biopsy was performed to confirm the severity of pulmonary vascular disease through histopathological examination. According to the Heath–Edwards classification, the biopsy showed pulmonary vascular changes consistent with Stage II–III. Based on the combined clinical, imaging, and pathological findings, the patient was considered suitable for surgery. The correction was carried out via a mini-sternotomy by directly implanting the anomalous right pulmonary artery into the main pulmonary artery. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged in stable condition. At the six-month follow-up, repeat cardiac catheterisation revealed the following haemodynamic measurements (in mmHg): main pulmonary artery: 35/14 (22), left pulmonary artery: 31/15 (22), right pulmonary artery: 34/14 (22), and the right ventricle pressure was 37/3. No residual stenosis was detected at the anastomosis site between the right ventricular outflow tract and the reimplanted right pulmonary artery (Figure 3).

Figure 3. ( a ) Catheter angiography demonstrating the origin of the pulmonary artery branches from the right ventricle following surgical repair. ( b ) Ascending aortogram showing no residual stenosis. ( c ) Cardiac MRI reveals a patent anastomosis between the right ventricular outflow tract and the right pulmonary artery (red arrow).

Discussion

The early onset and progressive course of pulmonary hypertension in patients with anomalous origin of one pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta significantly influences surgical outcomes. Therefore, managing patients diagnosed during adolescence or adulthood presents notable clinical challenges. In such cases, segmental pulmonary hypertension may already be well-established, necessitating meticulous evaluation of operability and long-term prognosis. Reference Gupta, Choubey, Kumar, Patel and Airan5 Beyond anatomical confirmation of anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta, the most critical and complex aspect in late-presenting cases is accurately assessing the severity and reversibility of pulmonary vascular disease.

Echocardiography is a highly sensitive but low-specificity modality for evaluating pulmonary hypertension, particularly in CHD. Cross-sectional imaging techniques, such as CT and cardiac MRI, provide detailed anatomical and functional information and are essential for diagnosis and longitudinal follow-up. Despite these advances, right heart catheterisation remains the gold standard for assessing pulmonary artery pressures and calculating pulmonary vascular resistance. However, in patients with anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta, the atypical vascular anatomy poses significant challenges in interpreting invasive haemodynamic data, particularly concerning operability and reversibility assessment. Reference Urbina-Vazquez, del Lopez-Rodríguez and Ortega-Silva6

Lung biopsy is not routinely employed in the assessment of pulmonary hypertension due to its invasive nature, limited diagnostic yield, and potential for complications. However, in certain cases—particularly when operability remains uncertain and non-invasive tests are inconclusive—it can serve as a useful adjunct in surgical decision-making. In our patient, a biopsy was conducted to better understand the degree of pulmonary vascular disease. In this case, histological findings indicated Stage II–III disease, supporting the decision to proceed with surgical repair. A similar approach was described by Zhao et al., who reported on two adolescents with anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta (aged 14 and 17 years), in whom lung biopsy revealed Stage II and Stage III pulmonary vascular disease. Both patients successfully underwent surgical correction, and no signs of pulmonary hypertension were observed during 9- and 8-year follow-ups, respectively. Reference Zhao, Si, Wang, Chen, Yan and Chen7

The normalisation of mean postoperative PA pressure can be explained using Ohm’s law and the formula for resistances in parallel:

$${1 \over PVR_{total} } = {1 \over PVR_{RPA} } + {1 \over PVR_{LPA} } $$

$${1 \over PVR_{total} } = {1 \over PVR_{RPA} } + {1 \over PVR_{LPA} } $$

Despite high preoperative resistance in the right pulmonary artery, the low resistance and compliant vascular bed of the left pulmonary artery lowers the total pulmonary vascular resistance, resulting in normalisation of overall PA pressures. This supports the notion that high unilateral PA pressure alone should not be considered an absolute contraindication to surgery. Reference Gupta, Choubey, Kumar, Patel and Airan5

In patients with anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta, both invasive haemodynamic assessment and lung biopsy carry procedural risks and may not always yield definitive information regarding operability. Therefore, a less invasive yet functionally informative approach was considered in this case. While 2D phase-contrast cardiac MRI has been validated for evaluating pulmonary haemodynamics in CHD, to the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have utilised cardiac MRI to assess pulmonary vasoreactivity in cases of segmental pulmonary arterial hypertension, such as anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta. Reference Körperich, Gieseke and Barth8 In this patient, serial 2D phase-contrast cardiac MRI measurements performed during inhaled iloprost administration revealed a 42% increase in flow through the anomalous right pulmonary artery, suggesting preserved pulmonary vascular reactivity. This non-invasive result provided supportive evidence toward operability and justified proceeding with lung biopsy. The biopsy subsequently confirmed Stage II–III disease, allowing for surgical intervention to be undertaken with a favourable risk–benefit profile.

In the surgical management of anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta, Armer et al. first reported in 1961 that the anomalous pulmonary artery could be connected to the main pulmonary artery using a Dacron interposition graft. Subsequently, in 1967, Kirkpatrick et al. demonstrated that direct anastomosis was also feasible, eliminating the need for synthetic grafts. Today, direct implantation is the preferred technique, particularly in isolated anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta cases diagnosed during infancy. Reference Jiang, Zhang and Hu9

In patients for whom direct anatomical repair is not feasible—typically due to delayed diagnosis and advanced pulmonary vascular disease—alternative approaches such as pneumonectomy or single-lung transplantation may be considered. In a case reported by Nikolaidis et al., a 41-year-old patient with anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta presented with recurrent haemoptysis and was deemed unsuitable for definitive surgical correction due to high-operative risk. As a palliative measure, pulmonary artery banding was performed. During a two-year follow-up period, no recurrence of haemoptysis was observed. Reference Nikolaidis, Velissaris and Haw10

The operation was carried out using a mini-sternotomy approach. This method provided adequate exposure for direct implantation while reducing surgical trauma. To our knowledge, this is one of the very few reports describing the use of a minimally invasive technique for late-presenting AORPA. The favourable postoperative outcome further supports the potential feasibility and safety of this approach in carefully selected patients.

Conclusion

Anomalous origin of the right pulmonary artery from the ascending aorta is a rare congenital malformation typically diagnosed and repaired in early infancy. In patients presenting during adolescence or adulthood, assessing operability remains a major clinical challenge. While lung biopsy may aid in select cases, this report highlights the potential utility of a non-invasive vasoreactivity assessment using inhaled iloprost during 2D phase-contrast cardiac MRI to support decision-making before high-risk invasive procedures.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None.