Introduction

The role of interest groups in policy making has long been a subject of academic debate. On the one hand, these groups can serve as a ‘transmission belt’ between the public and policymakers. On the other hand, consulting groups carries the risk that they exert undue influence on policies to promote their own special interests (e.g., Boräng & Naurin, Reference Boräng and Naurin2022; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Carroll and Lowery2014, Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018; Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1948; Schlozman & Tierney, Reference Schlozman and Tierney1986). Recently, scholars have started to examine how legitimate citizens perceive interest group involvement in policy-making processes (Bernauer & Gampfer, Reference Bernauer and Gampfer2013; Bernauer et al., 2016, Reference Bernauer, Mohrenberg and Koubi2020; Beyers & Arras, Reference Beyers and Arras2021; Rasmussen & Reher, Reference Rasmussen and Reher2023; Terwel et al., Reference Terwel, Harinck, Ellemers and Daamen2010). While the general answer has been that they boost perceived legitimacy, unequal involvement of different types of interest groups can dampen this effect. Especially processes where cause groups representing broader societal interests, such as environmental or consumer organizations, are under-represented or absent are perceived as less legitimate by citizens.

Yet, previous research has only sparsely reflected on variation in how individuals judge the involvement of specific types of interest groups in policy making. We address this question by asking whether, and how, citizens’ ties to different types of interest groups – specifically, cause and business groups – affect how legitimate they perceive decision-making processes that involve group types to unequal degrees. We argue that citizens have a preference for consulting the groups to which they have emotional ties, indicating affective attachment to a group (i.e., trust), behavioural ties, meaning actual engagement in groups (e.g., supporting them financially), or attitudinal ties, where citizens and interest groups share ideological views. Furthermore, we posit that the effects of ties to interest groups representing societal and business interests are asymmetric, due to differences in the quality of the relationships between these interest group types and their constituents. Citizens’ affiliation to cause groups is likely to be more solidary, expressive and value-based in nature than to business groups, which promote more exclusive benefits that are often restricted to their members or certain sectors of the economy, rather than a more widely shared mission. As a result, we predict that ties to cause groups lead to stronger reactions to the inclusion and marginalization of these groups in consultations than ties to business groups.

We test our expectations in a survey experiment with a conjoint design among representative samples of around 3,000 respondents, respectively, in Germany, the United Kingdom (UK) and the Unites States (US). We presented respondents with two realistic decision-making scenarios in which parliaments invite cause and business groups to provide oral evidence. By randomly varying the balance of the groups of each type that are invited, we can identify the effect of (unequal) group consultation on citizen perceptions of legitimacy. We also asked respondents to what extent they trust the group types, whether they are members or otherwise engaged with them and where they stand on the left-right dimension, to measure respondents’ affective, behavioural and attitudinal ties to the group types, respectively.

We show that the aggregate patterns in how citizens judge consulting different types of interest groups shown in previous research, indeed, conceal important individual differences. Citizens with any type of ties to cause groups consider processes that under-represent these groups as less legitimate than processes that under-represent business groups. By contrast, citizens with behavioural or attitudinal ties to business groups consider unequal group representation in either direction as similarly legitimate; only trust leads to a stronger preference for the representation of business groups. Thus, we find that while ties matter, not all ties matter equally.

Our findings contribute to the literature on how citizens assess the legitimacy of policy making, which has focused on, for example, turnout in referendums, participatory forms of decision making and gender balance in committees (e.g., Arnesen & Peters, Reference Arnesen and Peters2018; Arnesen et al., Reference Arnesen, Broderstad, Johannesson and Linde2019; Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019; De Fine Licht et al., Reference De Fine Licht, Naurin, Esaiasson and Gilljam2014; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2019; Strebel et al., Reference Strebel, Kübler and Marcinkowski2019; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). Understanding better how different parts of the electorate perceive the involvement of (specific types of) interest groups in policy making helps shed light on how citizens filter information about group involvement in policy making. This makes our findings important for scholars but also for policymakers, who might not only be held accountable by citizens for their policy decisions but also for their decisions about which interest groups to provide access to in policy-making processes.

The role of group ties in legitimacy perceptions

Our study focuses on oral consultations, which are a key way for governments or parliaments to select and invite a set of stakeholders to express their views and provide expertise, for example about potential future legislation (e.g., Ban et al., Reference Ban, Park and You2022; Bishop & Davis, Reference Bishop and Davis2002; Eising & Spohr, Reference Eising and Spohr2017; Fraussen et al., Reference Fraussen, Albareda and Braun2020; Helboe Pedersen et al., Reference Helboe Pedersen, Halpin and Rasmussen2015; Leyden, Reference Leyden1995; Mikuli & Kuca, Reference Mikuli and Kuca2016). Because interest groups participating in oral consultation have already passed the hurdle of obtaining access to policy making, these procedures are typically seen as central venues for interest groups to try to influence policy making (e.g., Beswick & Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019). According to the logic of an exchange framework (e.g., Pfeffer and Salancik, 2003 [Reference Pfeffer and Salancik1978]; Berkhout, Reference Berkhout2013; Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2004; Lowery & Gray, Reference Lowery and Gray2004), oral consultations can be viewed as central venues through which interest groups provide both technical expertise and political information about stakeholder views on topics to decision makers, in exchange for potentially having their views heard.

A small but growing literature examines how legitimate citizens perceive the consultation of different types of interest groups in policy making at the domestic and the international levels (Bernauer et al., Reference Bernauer, Mohrenberg and Koubi2020; Beyers & Arras, Reference Beyers and Arras2021; Rasmussen & Reher, Reference Rasmussen and Reher2023; Terwel et al., Reference Terwel, Harinck, Ellemers and Daamen2010). This research suggests that the involvement of cause groups, such as environmental organizations, increases the perceived legitimacy of policy-making processes, whereas consulting business groups has less strong positive or even negative effects. Importantly, unequal involvement of different types of groups is seen as less legitimate than equal participation. While these studies distinguish between different interest group types, they do not take into account how individual citizens relate to the different group types. We expect that individuals react to injustices towards the groups they identify with more strongly than those affecting other groups. As such, we argue that marginalizing one group type in consultations will decrease the perceived legitimacy of the decision-making process more strongly among citizens with ties to this group type. Conversely, we expect that legitimacy losses will be mitigated if the group type to which citizens hold stronger ties is over-represented.

One underlying rationale is that citizens identify with the interest groups to which they hold ties. In line with social identity theory (e.g., Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986), they should prefer situations where their in-group has influence over situations where the out-group – interest groups with which they do not identify – does. This mechanism is particularly relevant for affective ties, that is, group trust, and behavioural ties, that is, group engagement. An additional mechanism is based on cognitive heuristics: it predicts that citizens use the involvement of group types that share their broad political views as an information short-cut to judging whether their views are adequately represented (Lau & Redlawsk, Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001). This mechanism is likely to explain why attitudinal ties – shared political ideology – affect citizens’ legitimacy perceptions of involving different interest group types.

Previous research demonstrates that interest group mobilization has a particular capacity to enhance positional congruence between citizens and elected representatives who share similar ideological views (De Bruycker & Rasmussen, Reference De Bruycker and Rasmussen2021). It also shows that group ties and identity shape individuals’ perceptions of the composition of decision-making bodies in various contexts more broadly. For example, among equality- or proportionality-based procedures, which can both be considered fair, individuals tend to endorse those that give their group greater influence (e.g., Azzi, Reference Azzi1992; Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Christensen and Prislin2009). Moreover, citizens judge elections as fairer (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Martinez, Gainous and Kane2006), are more satisfied with the functioning of democracy (Anderson & Guillory, Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Singh, Reference Singh2014) and trust governments more (Keele, Reference Keele2005) if they voted for the winning candidate or party. These findings support our argument that individuals’ ties to groups and organizations not only shape how they evaluate the outcome of a process, but also the process itself.

Hypothesis 1: The stronger citizens’ ties to an interest group type, the less legitimate they consider processes that under-represent (as opposed to over-represent) this group type.

At the same time, we expect that citizens’ ties to cause and business groups are not equally important. The reason is that citizens’ motivations for engaging in the two types of groups and the nature of their relationships to them are likely to differ, and with this the implications that citizens draw from the groups’ inclusion in policy-making processes. As Moe (Reference Moe1980, Reference Moe1981) explains, individuals join groups either because of the potential of reaping private, economic benefits (Olson, Reference Olson1965) or due to non-material benefits (Salisbury, Reference Salisbury1969), including social or solidary incentives (e.g., obtaining a feeling of social status or a sense of companionship and belonging) as well as purposive incentives linked to broader supra-personal goals related to individuals’ ideological and ethical principles (e.g., social justice and good governance). The relative importance of material, solidary and purposive incentives is likely to vary between business and cause groups.

Economic incentives are likely to be particularly important for individuals to engage with business groups. Membership and activities of these associations is typically restricted to constituents possessing certain objective characteristics, for example, belonging to a specific profession with a shared economic interest and businesses in a specific sector (Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy1988). In contrast, non-material benefits are seen as particularly important for cause groups. These groups do not have fixed criteria for membership but appeal to members of the general public who support the broader causes for which they advocate (Berry, Reference Berry1977). People engage because they are devoted to supporting the fight for a particular joint cause, such as a cleaner environment, stronger animal protection or the fight against democratic backsliding.

The dedication to a common purpose might lead citizens with ties to cause groups to experience a stronger social identification than those with ties to business groups. As a result, they are likely to experience stronger positive and negative reactions to the inclusion and marginalization of these groups.Footnote 1 Since their engagement is based on a feeling that these groups represent important causes that ought to be promoted and represented in society, they are likely to perceive a process as less democratically legitimate when these groups are not adequately represented. By contrast, citizens with ties to business groups might feel that the process might be less likely to yield outcomes in their personal interest if these groups are under-represented, but their sense of democratic legitimacy might be less affected. Thus, we hypothesize that ties to cause groups have stronger conditioning effects than business group ties:

Hypothesis 2: Citizens with ties to cause groups perceive greater differences in the legitimacy of processes based on the under- and over-representation of the group type than citizens with ties to business groups.

Data and method

To test whether group ties condition how citizens evaluate the (unequal) participation of interest groups in policy-making we conducted survey experiments in Germany (N = 3,130), the UK (N = 3,048) and the US (N = 3,179) through Qualtrics. The samples were quota samples representative of the population along age, gender and region. Respondents were first shown a short text explaining that parliament can consult stakeholders, including different kinds of interest groups, by inviting them to participate in an oral consultation (see Figure S1 in the online Supplementary Information for the exact phrasing in each country). They were then presented with a vignette describing a realistic policy making scenario, where cause and business groups are either invited in equal numbers, in unequal numbers, or not at all. Afterwards, we asked respondents a set of questions measuring their perceived legitimacy of the process.Footnote 2 Each respondent participated in two experiments.

The oral consultation procedures are Congressional hearings in the US, oral evidence in the UK and public hearings in the German Bundestag. While their formats and practices differ somewhat between the parliaments, the procedures in the three countries share two key commonalities relevant for our design. First, they can be used to gather technical and political information (including insights into the attitudes of key constituents and the wider public) from interest groups and other stakeholders (e.g., experts, citizens and other public authorities) on new pieces of legislation similar to those in our vignettes, described below. According to Eising and Spohr's study of German hearings, ‘committee hearings are the most established and visible form of obtaining such policy advice and are also meant to enhance the legitimacy and transparency of decisions’ (Reference Eising and Spohr2017, p. 319). Second, access is determined by the parliaments (e.g., Ban et al., Reference Ban, Park and You2022; Eising & Spohr, Reference Eising and Spohr2017; Helboe Pedersen et al., Reference Helboe Pedersen, Halpin and Rasmussen2015; Loewenberg, Reference Loewenberg, Power and Rae2006; Mikuli & Kuca, Reference Mikuli and Kuca2016); this allows us to judge how citizens perceive parliament's decisions on which groups to invite, rather than the groups’ own choices or behaviour. These closed procedures are also seen as more efficient for participants to influence policy making compared to consultation procedures where access is not conditional on invitation (e.g., written consultations open to all interested stakeholders (see e.g., Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2015)) (Beswick & Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019).

All three countries constitute advanced democracies with long-standing traditions of involving interest groups in policy making, although their state-society structures differ. In neo-corporatist Germany, institutionalized political consultation with specific stakeholders is more common than in the pluralist models of the UK and US, where competition between stakeholders and decision-makers is more open and competitive (Jahn, Reference Jahn2016). Yet, we do not expect these differences to translate into differences in citizen attitudes towards unequal consultation of interest groups. Similarly, we do not expect the nature of citizens’ trust, engagement, and ideological alignment with groups to differ, or the effect of these on their attitudes towards consulting them. Instead, our rationale for including three countries in the study is to obtain more robust results and put their generalizability across advanced (western) democracies to a more stringent test. We conduct the analyses on the pooled sample but present estimates for each country in the SI (Section 5.4).

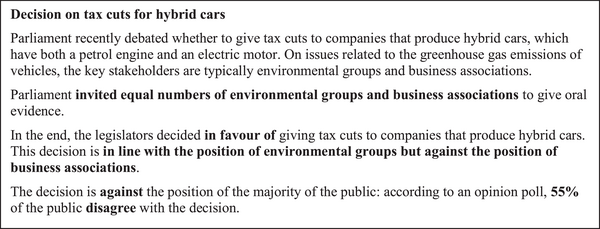

Figure 1 shows an example vignette. The values of the attributes in bold were randomly assigned independently from each other, giving it a conjoint design (Table S1 shows all possible values of each of the attributes). We explain that the key stakeholders on the issue are a type of cause group and business organizations. We then randomly vary whether parliament consulted (a) neither of the group types, (b) equal numbers of both group types, (c) more cause groups or (d) more business groups; this is our independent variable. To identify the effects of the consultation of groups on respondents’ legitimacy perceptions independently from (assumptions about) the policy decision, the groups’ policy attainment and the alignment of the decision and groups’ positions with public opinion, we also randomize whether the policy proposal was accepted or rejected, whether this decision reflects the positions of both, neither or one of the group types, and whether the decision reflects public opinion.

Figure 1. Example of vignette on tax cuts (UK version).

The two experiments each respondent participated in are identical except for the policy issue and the type of cause group that is the key stakeholder: one decision is about tax cuts for hybrid car producers (see Figure 1), with environmental groups as the cause groups, and the other is about regulating sugar content of beverages, with consumer groups as cause groups. The two issues were selected so as to fall into different areas and to realistically have business associations and a type of cause group as key stakeholders. Importantly, since we vary the groups’ policy positions, we also chose policies which business and cause groups may realistically either support or oppose. For example, some business groups may welcome the tax break whereas others, for example car makers that do not manufacture hybrid cars, might oppose it. Similarly, environmental groups might support greener solutions or might oppose cars altogether, while consumer organizations might welcome legislation that protects people's health or reject limitations of people's choices. Presenting respondents with these realistic yet simplified scenarios is likely to yield more externally valid estimates of citizen evaluations of such processes than abstract survey questions. It is certainly true that, in reality, citizens are not always aware of which interest groups are involved, and to what degree, in the policy-making process. Nevertheless, it is important to ascertain their opinions on the set-up of these processes when they do have access to this information, which is arguably the ideal scenario in a flourishing democracy.

Each respondent participated in both experiments in randomized order (Section 5.2 in the SI shows that the order of the experiments did not affect the results; Section 5.3 shows the estimates for each experiment separately). After each vignette, respondents were asked a set of questions about the process and the decision. Perceptions of the legitimacy of governance are based on both the process and its outcomes (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019). We are interested in the former: procedural legitimacy. This is measured by respondents’ agreement with three statements: ‘The process that led to the policy decision was fair’, ‘When making the decision, policymakers took the views of all relevant actors into account’ and ‘The process that led to the decision was democratic’. Agreement with each statement is measured on a five-point scale; our composite measure takes the mean of the items.Footnote 3

Moderating variables

Since there may be differences between our group types in how any given type of tie could materialize, we employ measures of three different types of ties. As an indicator of emotional ties, we measure respondents’ trust in business, environmental and consumer groups before the experiments in order to avoid post-treatment bias. Since we pool the data from the two experiments, we generate a measure of trust in cause groups which indicates respondents’ trust in environmental groups in the hybrid cars experiment and trust in consumer groups in the beverage experiment. We generate a measure of relative trust, which subtracts trust in business groups from trust in cause groups and ranges from −10 (high relative trust in business groups) to 10 (high relative trust in cause groups).

To measure engagement in the group types as our indicator of behavioural ties, we asked respondents at the end of the survey (since recall of behaviour should be less at risk of post-treatment bias but might prime respondents if asked before the experiment) whether they are a member of or had participated in events or activities, donated money or volunteered in business or employer, environmental or consumer organizations in the previous 12 months. We create a nominal variable indicating whether a respondent has engaged in at least one of these ways with neither of the group types, both, only business or only cause groups. Again, for engagement in cause groups we use environmental or consumer groups, depending on the experiment.

Finally, we measure attitudinal ties by respondents’ self-placement on the ideological left-right scale, measured before the experiment. Left-wing citizens are assumed to align with cause groups, while right-wing citizens are linked to business groups, akin to the alignment between left and right-wing parties and these interest groups, as literature suggests (e.g., Allern, Reference Allern2010; Allern & Bale, Reference Allern and Bale2012; Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Hanegraaff and Statsch2021; Otjes & Rasmussen, Reference Otjes and Rasmussen2017). Section 2 in the SI provides further details on the measures and descriptive statistics and bivariate correlation of the ties measures.

Our models include the other randomized attributes as covariates: whether group types attain their policy preference; degree of public support for the policy, as citizens might prefer decisions aligned with the public majority (Arnesen et al., Reference Arnesen, Broderstad, Johannesson and Linde2019); and a measure of outcome favourability, that is, whether the policy decision is aligned with the respondent's policy preference (cf. De Fine Licht et al., Reference De Fine Licht, Naurin, Esaiasson and Gilljam2014). For the latter, we asked respondents about their positions on the two policies before the experiment on five-point scales from ‘strongly oppose’ to ‘strongly in favour’. This scale was flipped when the randomly assigned decision was against the policy. We include fixed effects for the countries, the issues (hybrid cars or beverages) and whether the experiment appeared first or second in the survey.

Results

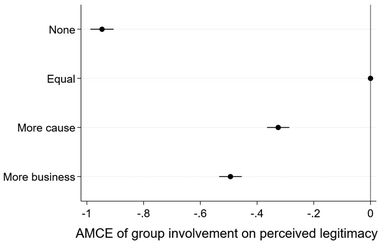

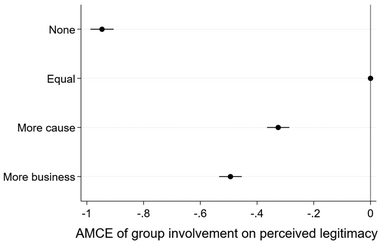

We illustrate the key findings through plots of marginal effects and predicted values of the outcome. The full results are shown in Table S4. Figure 2 shows the average marginal effects of group involvement on legitimacy perceptions from a linear regression model, with equal involvement as the reference category. Citizens perceive the process as most legitimate when business and cause groups are involved in equal numbers, and least legitimate – almost an entire scale point lower on the five-point scale – when neither group type is involved. Unequal group involvement is considered less legitimate than equal involvement, but still more legitimate than processes that exclude interest groups. An over-representation of cause groups is seen as more legitimate than a stronger presence of business groups, with a modest but statistically significant difference of 0.17 points on the 5-point scale.

Figure 2. Effects of interest group involvement in decision-making on perceived legitimacy.

Note: Full set of model estimates shown in Table S4.

According to existing research, the reason is likely because citizen groups are perceived as and shown to be more representative of society than business groups (Flöthe & Rasmussen, Reference Flöthe and Rasmussen2019; Rasmussen & Reher, Reference Rasmussen and Reher2023). Following an exchange logic, citizen groups are also typically seen as more likely to provide political information about constituent opinion to policymakers than business groups, who are instead known for their comparative advantage in providing technical expertise (e.g., Dür & Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013; Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2020). Facilitating that constituent views are transmitted to policymakers may be more desirable for boosting the legitimacy of policy making than submitting technical expertise in the eyes of citizens. This also aligns with recent literature indicating that while lobbying by business (and sectional groups more broadly) provides incentives for elected representatives to defect from their constituents, citizen groups strengthen the bond between representatives and their voters (Giger & Klüver, Reference Giger and Klüver2016).

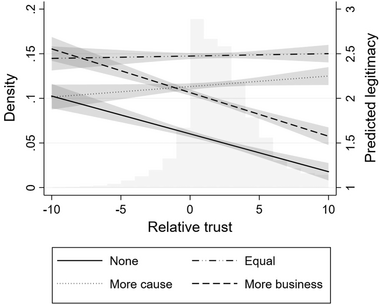

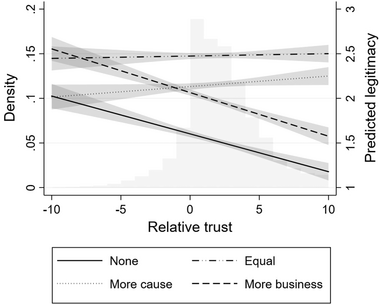

Next, we examine whether these perceptions vary with citizens’ interest group ties by adding interactions between the ties measures and group representation scenarios. Figures 3–5 illustrate these moderating effects by showing the predicted legitimacy perceptions under the different consultation scenarios for different values of the ties measures. In Figure 3, we see that relative trust in the two group types clearly moderates the effects of unequal group participation, supporting Hypothesis 1. Individuals with high trust in business and low trust in cause groups (low values on the scale) consider processes which under-represent business groups as less legitimate than processes over-representing them or involving both group types equally. Similarly, at the other end of the scale, individuals with high trust in cause and low trust in business groups (high values) clearly consider processes which under-represent cause groups as much less legitimate than processes with equal involvement or under-representation of business groups. Citizens at the mid-point of the trust scale, who (mis-)trust both group types equally, see their under-representation as equally legitimate.

Figure 3. Predicted legitimacy by interest group involvement, moderated by relative group trust (based on average marginal effects).

Note: High positive levels on the trust variable mean high trust in cause and low trust in business groups; zero means equal trust in both group types; high negative levels mean high trust in business and low trust in cause groups. Full set of estimates shown in Table S4.

We also find some support for Hypothesis 2: the effect of affective ties to cause groups is stronger than the effect of affective ties to business groups. Amongst citizens with the strongest relative trust in cause groups (10 on the scale), procedural legitimacy is 0.67 points lower if cause groups are under-represented than if business groups are under-represented. Meanwhile, amongst citizens with the strongest relative trust in business groups (−10 on the scale), procedural legitimacy is 0.54 points lower if business groups are under-represented than if cause groups are under-represented, meaning the effect is slightly smaller. More generally, it appears that citizens with high trust in cause groups are more concerned about the involvement of interest groups in policy making, as the predicted legitimacy of the different scenarios has a much wider range than amongst citizens with high relative trust in business groups.

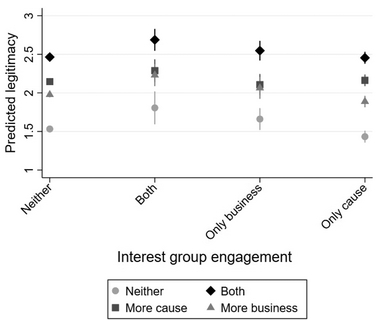

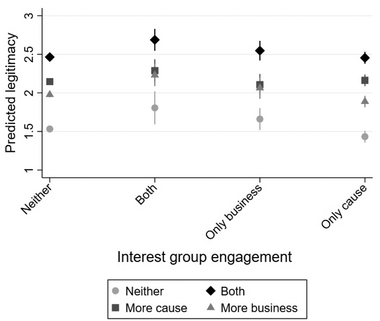

Figure 4 shows the results of the moderating effects of behavioural ties, measured by group engagement. Looking first at citizens engaged in business groups, we find that while they prefer equal over unequal group involvement, they do not perceive processes under-representing business groups as any less legitimate than processes under-representing cause groups – similarly to individuals engaged in both group types. By contrast, citizens only engaged in cause groups clearly do consider processes under-representing these groups as less legitimate than processes under-representing business groups. Thus, behavioural ties matter, supporting Hypothesis 1, and the effect of having their group type less well represented is stronger among citizens with ties to cause groups, supporting Hypothesis 2.

Figure 4. Predicted legitimacy by interest group involvement, moderated by group engagement in only cause, only business, both cause and business or neither cause and business groups (based on average marginal effects).

Note: Full set of estimates shown in Table S4.

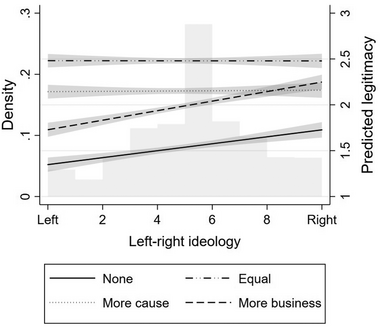

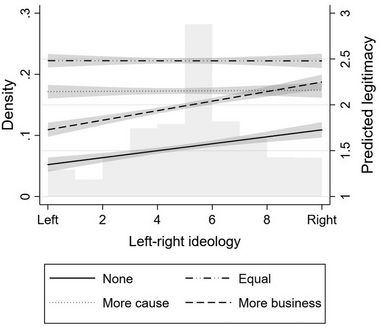

Finally, Figure 5 shows that attitudinal ties also affect the perceived legitimacy of unequal group representation. Citizens on the left clearly consider policy-making processes under-representing cause groups as less legitimate than processes under-representing business groups. This gap decreases as we move to the right, though interestingly, citizens at the ideological centre still prefer business groups to be under-represented rather than cause groups. Meanwhile, citizens on the right do not see processes under-representing business groups as less legitimate than processes under-representing cause groups. This pattern is similar as for behavioural ties and, again, supports Hypothesis 2: ties to cause groups generate stronger concern about the under-representation of these groups in policy-making.

Figure 5. Predicted legitimacy by interest group involvement, moderated by ideology (based on average marginal effects).

Note: Full set of estimates shown in Table S4.

We can draw several conclusions from these results. Most importantly, we find that affective, behavioural and attitudinal ties to interest groups shape citizens’ perceptions of how legitimate policy-making processes are, and ties to cause groups are particularly relevant. Citizens with strong ties to cause groups always consider their under-representation as less legitimate than the under-representation of business groups. By contrast, citizens with behavioural or attitudinal ties to business groups are equally concerned about the under-representation of both group types. Only high trust in business groups accompanied by low trust in cause groups leads to a preference for processes that over-represent business groups. This suggests that trust may be a more powerful tie than engagement or attitudinal congruence, which future research should explore further.

Conclusion

How interest groups contribute to democracy and democratic legitimacy has been a long-standing debate among both scholars and practitioners. Whereas there is no lack of arguments both supporting and criticizing the democratizing potential of groups (e.g. Bevan & Rasmussen, Reference Bevan and Rasmussen2020; Boräng & Naurin, Reference Boräng and Naurin2022; Flöthe & Rasmussen, Reference Flöthe and Rasmussen2019; Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1948; Schlozman & Tierney, Reference Schlozman and Tierney1986), there is a lack of research assessing how group involvement affects citizen judegement of the legitimacy of policy making. While a handful of studies have addressed this need (Bernauer & Gampfer, Reference Bernauer and Gampfer2013; Bernauer et al., Reference Bernauer, Gampfer, Meng and Su2016, Reference Bernauer, Mohrenberg and Koubi2020; Beyers & Arras, Reference Beyers and Arras2021; Rasmussen & Reher, Reference Rasmussen and Reher2023), they tend to not explore differences across citizens. Yet, we know that individuals’ identities and beliefs shape their responses to processes and outcomes, and such variation matters to politicians, who typically seek to appeal more to some citizens than others.

Our study shows that individuals indeed differ in how the consultation of interest groups in policy-making processes affects their legitimacy perceptions. Similarly to how voters who supported the losing party in an election tend to be less satisfied with the political system (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005), citizens perceive decision-making processes as less legitimate if the interest groups to which they hold ties are not equally represented. However, not all ties are equal: citizens who trust, are engaged in or share political attitudes with cause groups, such as environmental and consumer groups, consider processes that do not give these groups an equal voice as less legitimate. By contrast, processes that under-represent business groups do not invoke such strong reactions among citizens who are engaged in or share ideological views with these groups.

This discrepancy in the role of ties to business and cause groups is likely related to differences in people's reasons for joining the different types of groups and the nature of their group ties. Dedication to a joint cause is more likely to underpin ties to cause than to business groups, generating a stronger sense of group identification. The narrative of cause groups defending the interests of wider society, which is much less the case for business groups, also means that individuals close to cause groups are likely to conceive of them as legitimate representatives of large sections of the public who ought to be represented in democratic processes. This belief might also exist to some extent among individuals engaged in business but not cause groups and those with right-wing views, since they consider processes that over-represent cause groups just as legitimate as processes that over-represent business groups. Therefore, policymakers concerned about how legitimate citizens consider legislative processes – for example, because it may affect decision acceptance and compliance (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2019) – might want to pay special attention to the inclusion of relevant cause groups in consultations.

We hope these findings will stimulate additional future research on how ties to different types of interest groups affect legitimacy perceptions in policy making. While we have included different indicators of ties to make our conclusions less sensitive to differences between group types in how any given type of tie (such as the behavioural one in the case of business and citizen groups) might materialize, future research might explore additional measures. These could include behavioural measures of participation in comparable activities of specific (types of) groups, or more fine-grained attitudinal tie measures. Instead of considering left-right placement, it might be possible to collect survey data on positions of both interest groups and citizens on specific issues or policy dimensions (Allern et al., Reference Allern, Klüver, Marshall, Otjes, Rasmussen and Witko2021).

Beyond the more immediate implications for the design and organization of consultation procedures, our findings also have more general significance. They underline the importance of equal representation at the decision-making table for citizens’ justice and legitimacy perceptions, which previous research has demonstrated, for example, regarding the inclusion of women (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019) and Blacks (Hayes & Hibbing, Reference Hayes and Hibbing2017). At the same time, the study also confirms that the concern for equal opportunity and inclusion may compete with another concern, namely for one's personal interests and those of one's in-group.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2023 Annual Meeting of the European Political Science Association in Glasgow, the 2023 Annual Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research in Prague, the 2022 Money in Politics conference at the Copenhagen Business School, and a departmental seminar of the Department of Political Economy, King's College London in 2021. The article also benefited from comments received during an internal seminar at the University of Strathclyde. We thank all participants, in particular Ellis Aizenberg, Despina Alexiadou, Patrick Bayer, Adam Chalmers, Benjamin Egerod, Maria Grasso, Hanna Kleider, Brian Libgober, Julian Limberg and Evelien Willems, as well as the EJPR editors and the anonymous reviewers, for their valuable feedback and suggestions.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Data availability statement

The replication files for the study can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/G2NKLO.

Funding

The research was supported by funding from the European Research Council (Consolidator Grant 864648) and from the Danish Council for Independent Research (Sapere aude grant 0602–02642B).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure S1. Introductory text

Figure S2. Vignette on tax cuts for hybrid car producers (UK version)

Figure S3. Vignette on restrictions on sugar content of beverages (UK version)

Table S1. Attributes and values in vignettes

Figure S2. Mean group trust and proportion of citizens engaged in interest groups

Table S2. Correlations (Pearson's r) between the types of interest group ties

Table S3. Factor loadings of legitimacy questions from factor analysis with oblique oblimin rotation

Table S4. Linear regression of perceived legitimacy on interest group involvement, moderated by ties

Table S5. Linear regression of age and gender on randomized attributes

Table S6. Models from Table S4 among experimental group 1 (hybrid cars first)

Table S7. Models from Table S4 among experimental group 2 (sugar content first)

Table S8. Models from Table S4 on sample of hybrid cars experiment

Table S9. Models from Table S4 on sample of sugar content experiment

Table S10. Models from Table S4 estimated on UK sample

Table S11. Models from Table S4 estimated on US sample

Table S12. Models from Table S4 estimated on Germany sample