Timeline of key events of the Greek National Schism (1915–1922)

-

• 1915: King Constantine dismisses Prime Minister Venizelos twice, sparking the National Schism.

-

• 1916: The “National Defence” movement led by Venizelos forms a provisional government in Thessaloniki, effectively splitting Greece into two administrations.

-

• 1917: King Constantine abdicates under pressure from the Allies, and Venizelos returns to power, officially aligning Greece with the Entente in World War I. Authoritarian rule of Venizelos.

-

• 1920: Treaty of Sèvres expands Greece’s territory; Venizelist victory celebrations take place in September. Venizelos loses elections later in the year, and royalists return to power. King Constantine is restored to the throne following a plebiscite, increasing political instability.

-

• 1922: The Asia Minor Catastrophe marks the end of Greece’s territorial ambitions. Fall of the Antivenizelist Government and execution of its members in the Trial of the Six.

Introduction

In a world where sound and music shape political realities and collective identities, the study of historical soundscapes reveals how auditory experiences have been employed as tools of power, resistance, and nationalist narratives. This essay examines the Greek National Schism (1915–1922) through an ethnographic reconstruction of the soundscapes embedded in the Venizelist victory celebrations of 14–15 September 1920. These curated cultural, musical, and auditory experiences—including songs, anthems, marches, dances, and public chants—were deliberately designed to consolidate power within a polarized society. However, alongside these dominant soundscapes, spontaneous public soundscapes of protest and dissent emerged, challenging the state’s auditory supremacy and reflecting the contested nature of political authority.

While focusing on the Venizelist celebrations as a case study, this essay situates these soundscapes within the broader context of the decade 1912–1922. Nationalist performances during the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) (Liavas Reference Liavas2009: 125–33) and Antivenizelist celebrations following the General Elections of November 1920 (Kokoris Reference Kokoris2025) illustrate how sound and music consistently served as tools of political mobilization and identity formation during critical moments of Greek history.

This research introduces a methodological approach to address the challenges of reconstructing these soundscapes from partisan and polarized sources. By cross-referencing archival materials—including press narratives, parliamentary speeches, and diplomatic records—it uncovers shared auditory events described by both Venizelist and Antivenizelist perspectives. This method mitigates bias by identifying common ground between conflicting accounts, revealing the consistent events underlying divergent interpretations. These reconstructed soundscapes highlight how music and auditory practices mediated power, resistance, and identity during the National Schism.

Through this lens, the study draws on contemporary ethnomusicological discourse on music and politics (Berger Reference Berger2014; Mahon Reference Mahon2014; Berger and Stone Reference Berger, Stone, Berger and Stone2019; Belkind Reference Belkind2021), sound and noise (Wong Reference Wong2014; Rice Reference Rice2017; Meizel and Daughtry Reference Meizel, Daughtry, Berger and Stone2019), and historical acoustemology (Smith Reference Smith2004, Reference Smith2007; Mansell Reference Mansell2021). By treating soundscapes as primary ethnographic sources, it reveals how music and sound shaped nationalist narratives, consolidated political authority, and facilitated acts of resistance. Ultimately, this essay demonstrates the centrality of soundscapes in mediating collective memory and political transformation within civil conflicts.

Reconstructing soundscapes: bridging music, politics, and historical narratives

Contemporary ethnomusicology increasingly examines the intricate interplay between music, politics, and power, particularly in conflictual contexts (O’Connell Reference O’Connell, O’Connell and Castelo-Branco2010; Belkind Reference Belkind2021). Timothy Rice (Reference Rice2017: 249–50) calls for an ethnomusicology attuned to “times and places of trouble,” where music shapes and is shaped by social and political realities. This aligns with interdisciplinary efforts to decentre music studies, incorporating vocal and sonic dimensions that emphasize music as an active cultural and political practice (Meizel and Daughtry Reference Meizel, Daughtry, Berger and Stone2019: 176, 184; Wong Reference Wong2014). Historical soundscape studies complement this perspective by uncovering how auditory experiences are embedded in cultural memory, mediating power dynamics and shaping political narratives (Mansell Reference Mansell2021; Smith Reference Smith2004: ix–xxii; Smith Reference Smith2007: 41–58).

The convergence of ethnomusicology with auditory history and sound studies fosters interdisciplinary dialogue across the humanities. Schafer’s (Reference Schafer1994) soundscape theory frames sound as both a natural and socially constructed element of the human environment. Meizel and Daughtry (Reference Meizel, Daughtry, Berger and Stone2019) build on this, highlighting listening as a culturally situated act that reflects and reinforces power hierarchies. Smith, in the introduction of his edited volume Hearing History: A Reader (2004: ix–xxii), critiques the dominance of visual narratives in historical studies, advocating for the centrality of sound as an active force that shapes identities, challenges social structures, and mediates political power. This study engages these frameworks to reconstruct the soundscapes of the Greek National Schism (1915–1922) through press articles, diaries, and other textual sources, underscoring the multisensory and embodied nature of listening practices in public spaces.

Philip Bohlman’s (Reference Bohlman, Barz and Cooley2008: 258–9, italics in original) concept of the “Past as Everyday and Mentalité” further elucidates how musical practices dynamically connect past and present, embedding lived experiences into historical narratives. His emphasis on the “Past as Narrative Space” (2008: 261–263), particularly in his analysis of European Jewish communities, illustrates how music and ritual performances shape collective identities and reveal contested historical memories. Applied to the Greek National Schism, this perspective highlights how Venizelist and Antivenizelist soundscapes functioned as performative tools for political identity formation and resistance.

James Mansell’s (Reference Mansell2021) historical acoustemology provides additional insight into how societies interpret past auditory experiences to understand political and cultural hierarchies. Mansell emphasizes the role of sound in reinforcing or disrupting social orders, arguing for its analytical centrality in political historiography. Recent studies, such as those in the Radical History Review (Bender et al. Reference Bender, Corpis and Walkowitz2015), reinforce this perspective, asserting that soundscapes are not neutral but shaped by political and cultural forces. This study explores these insights to analyse how Venizelist soundscapes amplified state authority while Antivenizelist counter-soundscapes contested dominant narratives, reshaping public discourse.

Jacques Attali’s Noise: The Political Economy of Music (1985) frames noise as a force that disrupts social orders and signals societal transformation. In the context of the National Schism, Antivenizelist dissent—manifested through chants, protests, and reappropriated anthems—aligns with Attali’s concept of noise as an active agent of resistance. Venizelist soundscapes, curated through public celebrations and media portrayals, consolidated power by framing Venizelos as the embodiment of national unity, while counter-soundscapes used spontaneous and subversive auditory practices to challenge this hegemony.

Building on William Noll’s (Reference Noll, Barz and Cooley1997: 163, 166–8, 171) concept of the ethnographer of the past as a “silent partner,” this study reframes early twentieth-century Greek journalists as unintended ethnographers who wielded “cultural authority” in shaping public perceptions. These journalists actively constructed soundscapes that asserted political dominance, shaped cultural identities, and marginalized dissent. Noll’s emphasis on the dialogic relationship between past and present underscores the interpretive value of these sources, despite their biases. By treating press narratives as constructed soundscapes, this research aligns with Noll’s (Reference Noll, Barz and Cooley1997: 170) notion of “dovetailing” past and present to reveal how auditory practices mediated power and memory across temporal divides.

Historiographical insights from Adrian Bingham (Reference Bingham2009), Marcel Broersma (Reference Broersma2007), and Martin Conboy (Reference Conboy2002) highlight newspapers’ role in actively shaping public opinion. Treated as quasi-ethnographic documents, these sources mediated contested soundscapes while reflecting journalistic and political biases. Kitsios (Reference Kitsios2020) and Lyberatos (2021) further emphasize the challenges of reconstructing soundscapes from politically charged narratives, underscoring the need to navigate silences and omissions. By synthesizing these perspectives, this study reconstructs Athens’s contested auditory environments, revealing how sound mediated power and shaped collective memory during the National Schism.

This research employs critical discourse analysis to reconstruct the soundscapes of the National Schism, treating newspapers and archival documents as “earwitness accounts.” These sources—cross-referenced with parliamentary and public speeches, along with diplomatic and governmental records—offer invaluable details of sounds, chants, and musical expressions in public spaces. However, the limited space of this essay allows for an analysis of newspaper articles and chronicles. The Venizelist Ακρόπολις (Acropolis), Ελεύθερος Τύπος (Eleftheros Typos), Εστία (Estia), and Μακεδονία (Makedonia), and the Antivenizelist newspapers Αθήναι (Athinai), Εμπρός (Embros), and Πολιτεία (Politeia), offer invaluable insight into the soundscapes of this tumultuous period. By following this methodological approach, the study reconstructs the curated Venizelist soundscapes of victory parades, anthems, and folk dances alongside the counter-soundscapes of Antivenizelist protests and subversive songs, capturing the contested auditory dynamics of the period.

The curated soundscapes of victory parades, patriotic anthems, folk songs and dances, and military marches were instrumental in consolidating Venizelist power, portraying Venizelos as the “Father of the People.” Conversely, Antivenizelist counter-soundscapes, manifested through protests, chants, and reappropriated musical symbols, challenged Venizelist dominance and asserted alternative political narratives. These auralities highlighted the contested nature of political authority and resistance, illustrating how sound became a medium for articulating dissent and reimagining national identity. Drawing on Noll’s emphasis on the power dynamics of cultural representation, this study underscores how public soundscapes served as arenas for both state control and popular resistance, reflecting the broader socio-political dynamics of early twentieth-century Greece.

Reassessing the National Schism (1915–1922): Charismatic Leadership and Mass Politics

The Greek National Schism (1915–1922) was one of the most divisive conflicts in modern Greek history, polarizing society between two entrenched political factions: Venizelists and Antivenizelists. The crisis had lasting repercussions on Greece’s political structures and societal dynamics, particularly during the interwar period (1922–1936). At its core, the Schism was not merely a personal rivalry between Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos (1864–1936) and King Constantine I (1868–1923) but a profound ideological conflict over Greece’s political direction and identity (Mavrogordatos Reference Mavrogordatos1983: 55–62).

The conflict began in February 1915, when King Constantine, favouring neutrality in World War I, dismissed Venizelos, who sought to align Greece with the Allied Powers. Despite Venizelos’s electoral victories, Constantine’s insistence on neutrality deepened the rift, eventually leading to the establishment of two competing governments in 1916: the royalist administration in Athens and Venizelos’s National Defence Movement in Thessaloniki. This division coincided with shifting European alliances, making Greece a focal point in the geopolitical rivalry between the Allied and Central Powers.

Under Allied pressure, Venizelos returned to power in June 1917, imposing martial law, censorship, and a crackdown on political opposition. His government exiled prominent Antivenizelists and banned public performances of the royalist anthem O Aetos,Footnote 1 replacing it with Venizelist symbols of loyalty. The period from 1917 to 1920 became known among Antivenizelists as the “Venizelist Tyranny,” reflecting their perception of his authoritarian rule.

The political landscape grew increasingly volatile in 1920. Venizelos secured significant diplomatic victories, including the Treaty of Sèvres on July 28, 1920, which expanded Greece’s territory. However, internal tensions escalated following an assassination attempt on Venizelos in Lyon and the murder of Antivenizelist leader Ion Dragoumis during the Ioulianà events in July 1920. The sudden death of King Alexander in October further destabilized the political climate.

The pivotal General Elections of 1 November 1920, unexpectedly brought the Antivenizelist United Opposition to power, marking a significant turning point. The electoral defeat of Venizelos reflected public discontent with his increasingly authoritarian policies and the mounting sacrifices imposed to fulfil the Megali Idea. Footnote 2 Following the Antivenizelist victory, a referendum reinstated King Constantine on 6 December 1920. The ensuing celebrations, marked by public singing of O Aetos and chants of the Antivenizelist symbol-chant elià (olive branch), symbolized the reclaiming of public spaces by Antivenizelists, with soundscapes becoming expressions of political power and psychological warfare (see Kokoris Reference Kokoris2025; cf. Mavrogordatos Reference Mavrogordatos2015: 269–70 for the socio-political analysis).

This historical trajectory underscores the cyclical nature of power shifts, where triumph is often followed by backlash (see Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006: 5–7; cf. Levy and Thompson Reference Levy and Thompson2010: 186–204). The Epinikia celebrations of September 1920 marked the zenith of Venizelist power, but societal tensions soon erupted, demonstrating how civil conflicts leave enduring psychological scars and recalibrate political allegiances. The Schism, as Mavrogordatos argues, illustrates the transformation of a personal dispute between two leaders into a mass political and cultural conflict, with each figure embodying distinct visions of Greece’s future (Mavrogordatos Reference Mavrogordatos1983: 60–2).

Venizelos and Constantine both exemplified charismatic leadership—a concept central to understanding the Schism’s escalation (see Mavrogordatos Reference Mavrogordatos2015). Venizelos’s charisma was based on his portrayal as a saviour during moments of crisis, while Constantine’s authority was rooted in his role as a God-appointed warrior-king, drawing on Byzantine and Orthodox traditions. Their simultaneous emergence created a unique situation in Greek history, where competing charismatic movements polarized society along cultural and political lines. This dynamic transformed the Schism into a quasi-religious conflict, with soundscapes playing a pivotal role in affirming loyalty and expressing dissent (Mavrogordatos Reference Mavrogordatos1983: 61).

Ultimately, the Schism reveals how charismatic leadership can fuel societal divisions, with mass political movements reinforcing exclusionary identities and deepening conflicts. The auditory landscape of Athens during this period vividly illustrates how political power was projected and contested through sound, demonstrating the lasting impact of charismatic authority on Greece’s political history. Having established the political context of the National Schism, the next section will explore how soundscapes during the 1920 celebrations were curated to promote Venizelist ideals, while Antivenizelist counter-soundscapes emerged as acts of resistance.

The Epinikia celebrations of 14–15 September 1920, 1920

The Epinikia celebrations in Athens commemorated the Treaty of Sèvres (signed on 28 July 1920), highlighting Greece’s national achievements and linking modern Greece to its ancient past. The concept for these festivities was initially proposed in an article from the US-based journal Christian Science Monitor, which was later republished in the Greek newspaper Estia on 30 August 1919 (Anonymous 1919). The article suggested the ceremonial crowning of the Greek Prime Minister with a wreath reminiscent of Olympic champions at the Panathenaic Stadium, symbolizing a connection between contemporary Greece and its ancient heritage.

The celebrations were attended by prominent figures, including King Alexander, Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, and members of the Cabinet, alongside the highest echelons of political, ecclesiastical, and military leadership. Local dignitaries, including bishops and mayors from across Greece, were welcomed by the Mayor of Athens, Spyridon Patsis, on the first day of the festivities.

The programme for the two-day event was meticulously organized. On the first day, the formal Doxology took place at the Metropolitan Church of Athens, followed by a reception for mayors at the Municipal Theatre. The afternoon featured the grand “Celebration of the Epinikia” at the Panathenaic Stadium, which included a procession and military parades, culminating in the arrival of King Alexander. The evening concluded with a performance at the “Dionysia” theatre and a concert in Syntagma Square.

The second day commenced with a reception for mayors at the Piraeus City Hall, followed by a lunch for ecclesiastical leaders. The afternoon was dedicated to a performance of Aeschylus’s Persians and the premiere of Manolis Kalomiris’s Symphony of Leventia Footnote 3 at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. The celebrations culminated in a gala dinner at the Zappeion, where the Mayor of Athens presented a golden wreath to Prime Minister Venizelos, symbolizing national unity and pride. The festivities concluded with a spectacular illumination of the city, including fireworks over the Acropolis and Lycabettus, encapsulating the celebratory spirit of the occasion.

The events of the first day

The inaugural day of the celebrations, as recounted by Estia (Anonymous 1920a), commenced at 11:00 a.m. with a morning reception at the Municipal Theatre, where mayors, communal leaders, and representatives from “the various parts of the new Great Greece” gathered in traditional attire reflective of their regional origins. The ceremonial atmosphere was imbued with symbolic messages of national unity and cultural diversity, encapsulating the aspirations of the newly expanded Greek state.

During his speech, Athens Mayor Spyridon Patsis passionately proclaimed a series of patriotic slogans, including “Hooray for Great Greece!”, “Long live the army!,” “Long live Venizelos!,” and “Up to the Poli [Constantinople], long live the Saviour of the Nation!”. His speech culminated in a fervent chant of “Long live Venizelos!” that resonated through the theatre. The emotional intensity of the gathering demonstrated the deep admiration for Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos among his supporters.

Following the reception, a demonstration unfolded as attendees made their way to the residence of the Prime Minister. The procession, led by Mayor Patsis and other dignitaries, was accompanied by enthusiastic chants and expressions of gratitude. According to Estia:

The demonstration of mayors and presidents, followed by a crowd of people, descended to the house of the Prime Minister cheering and acclaiming.

-

– “Hooray for the Liberator.”

-

– “Long live the National Lord.”

-

– “Long live the Liberator!” they shouted as they surrounded the house of Mr. Venizelos.

Venizelos, preparing to leave for the afternoon’s events, greeted the crowd at his front door, smiling and waving as chants of support filled the air. Mayor Patsis, representing the delegates, expressed their collective gratitude, emphasizing the historic significance of the day. Venizelos, visibly moved by the display of admiration, responded with heartfelt thanks. The Prime Minister’s attempts to enter his car were met with difficulty, as the crowd surged forward, eager to see him up close:

The crowd wanted to approach him, to see him face to face.

-

– “Long live you.”

-

– “A thousand years old,” they cried.

Many delegates, particularly those from the newly annexed territories, were overcome with emotion. Some wept openly, touched by the sincere expressions of loyalty and gratitude. Venizelos, deeply moved by the spontaneous outpouring of affection, continued to greet and thank the crowd before departing for the Panathenaic Stadium.

The day’s centrepiece was the grand celebration at the Panathenaic Stadium, described in detail by both the Venizelist press and opposition newspapers. Estia (Anonymous 1920a) highlighted the “greeting of the Victory” ceremony, where King Alexander, Prime Minister Venizelos, and Vice President Emmanuel Repoulis symbolically reaffirmed Greece’s territorial gains. The newspaper Athinai (Anonymous 1920b) offered a more nuanced account, noting the initial political chants from the crowd, representing both Venizelist and Antivenizelist factions. However, these chants were eventually overshadowed by a collective ovation that, according to the paper, “masked the veil of national unity among the attendees.” The arrival of Venizelos and other officials marked a key moment in the day’s events. Athinai emphasized:

The universal greeting which the entire Stadium, regardless of political affiliation and without any consideration of any personal affections, addressed to the Greek Prime Minister when he arrived, surrounded by the Cabinet, the Presidency of the Parliament and other officials. At that moment no one thought about whether or not they liked Mr. Venizelos and the whole world stood up and cheered him.

The events at the stadium were meticulously chronicled in various accounts. Historian Tasos Michalakeas, in his editorial for the centenary commemorative edition of Venizelos, The Bible of Eleftherios Venizelos (1964: 678–84), offers a detailed description of the arrival of dignitaries and their seating arrangements in the prominent stands facing the Cenotaph of the Fallen. The dignitaries included high-ranking political, military, and ecclesiastical leaders.

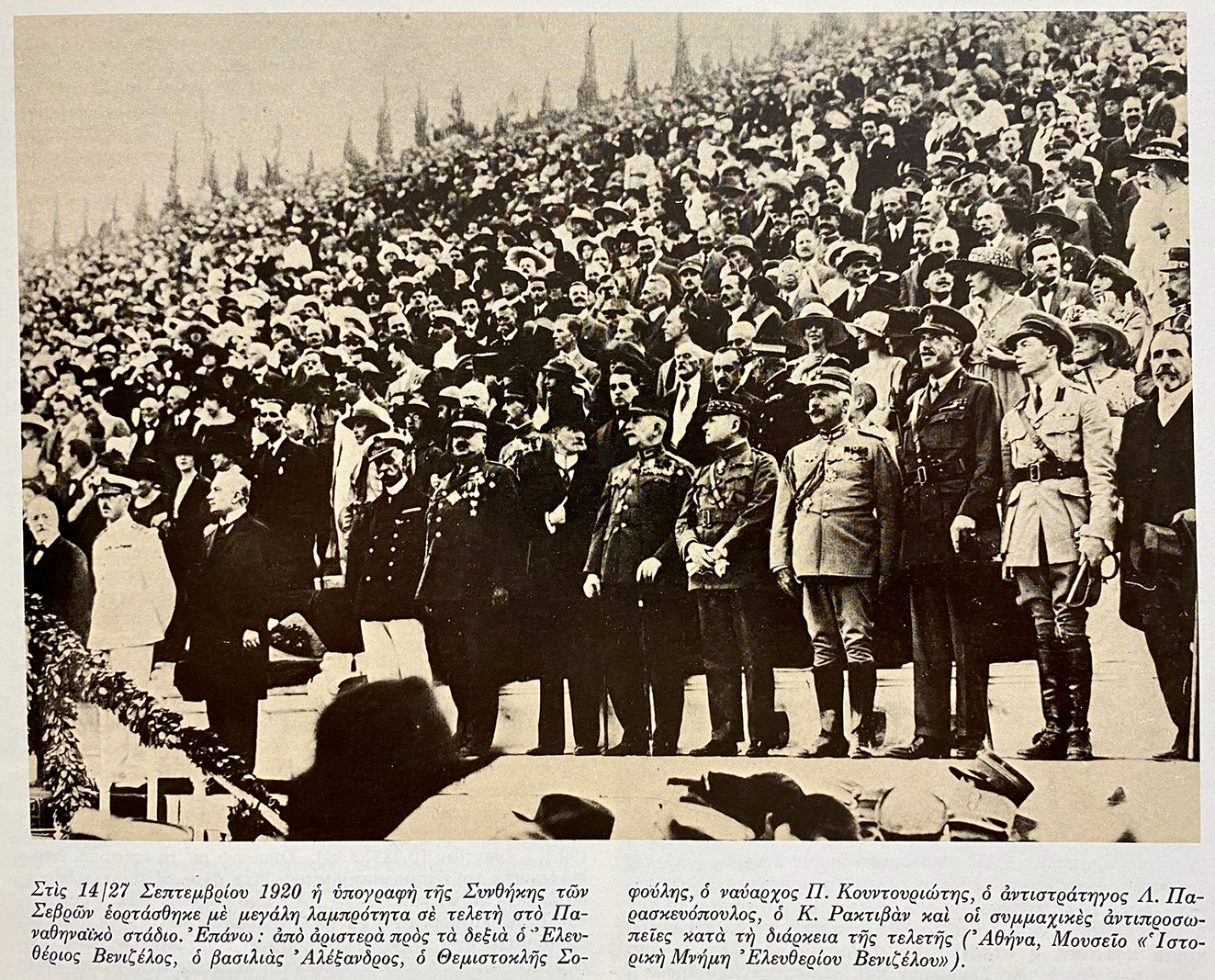

Figure 1. Stadium celebrations on 14 September 1920, honouring the Treaty of Sèvres. Prime Minister Venizelos is shown on the left, with King Alexander I beside him in a white uniform. The image also includes the names of Venizelist officials in the front row (History of the Hellenic Nation 2000: 149).

The sonic dimensions of the event were particularly notable. The ceremony included religious processions, the display of sacred banners, and a memorial service attended by over a hundred priests and fifty bishops. A Byzantine choir, comprising 150 chanters, performed hymns that resonated throughout the stadium. Among the notable musical pieces was Mavre ein’e nychta sta vouna, a patriotic march that stood out as a significant component of the soundscape.Footnote 4

A particularly memorable moment occurred when Prime Minister Venizelos presented King Alexander with a laurel wreath, an act steeped in ancient symbolism. The gesture evoked the image of an Olympic champion, prompting a rapturous ovation from the crowd, who celebrated Venizelos as a heroic figure embodying Greece’s aspirations and achievements.

The press coverage of the inaugural day’s events reveals contrasting narratives. Estia (Anonymous 1920c) reported an impressive turnout of between 120,000 and 150,000 attendees, interpreting this participation as a validation of Venizelist policies, particularly those aligned with the Megali Idea. The enthusiastic reception of Venizelos was portrayed as evidence of widespread support for his leadership.

However, opposition newspapers like Athinai offered a more critical perspective. While acknowledging the collective ovation that greeted Venizelos, Athinai also highlighted the political discord that preceded it, suggesting that the unity displayed at the stadium may have been more performative than genuine. The newspaper noted that the crowd’s applause for Venizelos did not necessarily reflect unanimous political support but was instead a reflection of the celebratory atmosphere and the gravity of the occasion.

The narratives surrounding the inaugural celebrations of the “new Great Greece,” as recounted by Estia and other contemporary sources, reveal a strikingly biased portrayal of the events. The enthusiastic reception of Venizelos, characterized by fervent chants and emotional displays of gratitude, is depicted as a universal sentiment among the attendees. This portrayal effectively glosses over any dissent or opposition, raising critical questions about the authenticity of the so-called national unity that the narratives claim to celebrate.

The contrasting account from Athinai, which acknowledges the initial political discord among factions, serves as a reminder of the complexities underlying the public’s reception of Venizelos. While the Athinai narrative highlights the eventual collective ovation, it also subtly critiques the superficiality of this unity, suggesting that it may have been more symbolic than genuine.

Figure 2. 14 September. Festivities in the Panathinaiko Stadium following the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres [Digitized Collections of Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive (E.L.I.A.)—Cultural Foundation of the National Bank of Greece 1920a].

Moreover, the emphasis on the sheer number of attendees at the stadium, interpreted by Estia as a validation of Venizelist policies, further exemplifies the bias inherent in these accounts. The framing of the gathering as a critique of “reactionaries” marginalizes dissenting voices and reinforces a narrative that positions Venizelos as the unequivocal hero of the era.

In summary, the events of the first day of the Epinikia celebrations reflect the intertwining of political sentiment with cultural expression. The public reception of Venizelos, the curated soundscape of the ceremonies, and the contrasting press narratives underscore the complexities of national identity and political allegiance during the National Schism. The inaugural day set a precedent for the subsequent celebrations, which would continue to blend historical symbolism with contemporary political aspirations.

The events of the second day: The Odeon of Herodes Atticus festivities

The second day of the festivities (15 September 1920) at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus unfolded with a meticulously planned agenda, as detailed by Athinai (Anonymous 1920d). Distinguished mayors and community leaders, welcomed in Piraeus, participated in a series of parades and receptions. A parade in front of King Alexander followed at 1:00 p.m., while Metropolitan Meletios Metaxakis of Athens hosted a luncheon for the visiting hierarchs. The day culminated with the performance of Aeschylus’s Persians and Manolis Kalomiris’s Symphony of Leventia at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. The evening concluded with a gala dinner at the Zappeion mansion, attended by the Mayor of Athens, Patsis, and other dignitaries, in honour of Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos. The narrative concludes with the mention of the “conventioneers” escorting Venizelos to his residence and outlines the itinerary for the visiting mayors and community leaders, who were set to embark on an excursion to the “New Lands,” with Smyrna as their destination.

Figure 3. Event at the Theatre of Herodes Atticus in the Presence of Eleftherios Venizelos. This photograph likely captures either the “Epinikia” victory celebrations in September 1920, or the May 1920 concert honouring French composer Camille Saint-Saëns, who performed at the Odeon during a festival organized by the Athens Conservatoire—both events attended by Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos. Without definitive visual or archival confirmation, the exact occasion remains unverified.[Digitized Collections of Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive (E.L.I.A.)—Cultural Foundation of the National Bank of Greece 1920b].

The newspaper Embros (Anonymous 1920e) provided an extensive report on the evening performances, capturing the atmosphere, the attendees, and the overall festive spirit. The report highlighted the significant turnout of large crowds, including clergy, representatives, and institutions, alongside the joyous arrival of King Alexander. The Hellenic Theatre Company’s rendition of Aeschylus’s Persians, followed by Kalomiris’s Symphony of Leventia, was central to the day’s cultural agenda.

The performance of Symphony of Leventia, conducted by Kalomiris himself, holds significant historical and cultural importance. Composed between 1918 and 1920, the symphony embodies themes of valour and national pride, resonating with the political aspirations of the Venizelist regime. According to Sakallieros (Reference Sakallieros2023), Kalomiris’s work exemplifies the synthesis of Greek musical modernism and nationalism, positioning the composer as a key figure in shaping a distinct Greek art music tradition. However, Sakallieros also highlights the nuanced relationship between Venizelos and modernism in the arts. While Venizelos actively supported modernist movements in the visual arts, such as the Ομάδα Τέχνη (Omada Techni, “Art Group”), his approach to music was more traditional, focusing on the preservation of folk musical traditions and his personal support for Kalomiris.

Nikolaos Papadakis (Reference Papadakis and Venizelos2017: 743) notes that Venizelos held a profound belief in the pedagogical power of the arts, which was a persistent concern for him. In 1919, amidst intense diplomatic challenges, Venizelos allocated substantial funding to support theatrical and musical groups, emphasizing the importance of accessible performances for the broader public. The staging of the Persians and Symphony of Leventia at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus reflected this vision, as cultural events were strategically used to reinforce national identity and unity.

Scholars like Anastasia Siopsi (Reference Siopsi2003) and Markos Tsetsos (Reference Tsetsos, Nikos and Alexandros2013) emphasize that Kalomiris was seen as a cultural ambassador of Venizelist ideals, representing a modern yet distinctly Greek musical idiom. His works combined European compositional techniques with Greek folk elements, creating a unique musical language that both resonated with popular sentiments and reinforced Venizelos’s political narrative of cultural progress and national unity. Tsetsos (Reference Tsetsos2011) further argues that Kalomiris’s music functioned as a political statement, reflecting the ideological alignment between the composer and the Venizelist regime.

The press narratives surrounding the performance further underscore the political and cultural symbolism of the event. Embros praised the grandeur of the symphony but critiqued its length, suggesting that the audience, eager for celebratory music, found some sections overly academic. The newspaper proposed that the performance might have been more effective if limited to the final movement, “The Victory Gratitudes,” which incorporated the Byzantine hymn To Thee, the Champion Leader. This hymn evoked profound patriotic emotions, leading many attendees to rise in appreciation, culminating in enthusiastic applause. In contrast, Estia (Anonymous 1920f) criticized the adaptation of the hymn, viewing it as a departure from traditional forms. The critique reflected broader societal tensions between modernist and traditionalist perspectives in the arts.

Kalomiris’s relationship with Venizelos is also explored by Xanthoulis (Reference Xanthoulis, Tasos and Argyro2012), who notes that the composer’s works were often used to reinforce Venizelist cultural policies. These policies aimed to project Greece as a modern European state while preserving its unique cultural heritage. The performance of Symphony of Leventia at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus symbolized this dual aim, blending modernist techniques with national symbols to create a cohesive narrative of cultural continuity and national triumph.

Despite the mixed reception, the performance of Symphony of Leventia was a deliberate cultural statement aligned with Venizelos’s broader vision of nation-building. The symphony’s blend of folk motifs and Byzantine elements symbolized a cohesive Greek identity that embraced both modernity and tradition. As Sakallieros (Reference Sakallieros2023) emphasizes, the inclusion of this symphony in the Victory Celebrations illustrated how music could be instrumentalized to project political messages and reinforce national unity.

In conclusion, the second day of the Victory Celebrations at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus showcased the complex relationship between culture, politics, and national identity in early twentieth-century Greece. The performances of Aeschylus’s Persians and Kalomiris’s Symphony of Leventia symbolized Greece’s historical continuity and cultural resilience, aligning with Venizelos’s nation-building agenda. The press coverage of the events highlighted the cultural symbolism and political messaging embedded in the day’s festivities, illustrating how music and theatre were used to shape public perceptions and reinforce the narrative of national progress. The celebrations at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus thus stand as a testament to the power of cultural production in shaping political discourse and fostering national unity during a transformative period in Greek history.

The events of the second day: The Zappeion mansion festivities

On the second day of the events honouring Prime Minister Venizelos, a grand reception was held at the Zappeion mansion, organized by the Municipality of Athens and attended by various dignitaries, including mayors and community leaders. Following performances at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, the gala dinner commenced, marked by the presence of political, military, and religious officials. The evening culminated with Mayor Spyridon Patsis delivering a toast and presenting a golden wreath to Venizelos, who responded with an impassioned speech. The festivities continued with a feast, during which the press provided vivid accounts of the musical diversity representing Greater Greece and the emotional resonance of Venizelos’s presence among the guests (Michalakeas Reference Michalakeas1964: 686).

Figure 4. Street bedecked in flags, possibly for the reception of Eleftherios Venizelos arriving from France [Digitized Collections of Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive (E.L.I.A.)—Cultural Foundation of the National Bank of Greece 1920c].

The newspaper Acropolis (Anonymous 1920g) enthusiastically detailed the arrival of the “conventioneers” and dignitaries, noting that upon Venizelos’s entrance, “the music performed the greeting [anthem] of the President of the Government” (see Footnote footnote 1 for Venizelos’s anthem). As the meal progressed, the atmosphere transformed into one of exuberance, with feasting and dancing taking centre stage. The music, performed from a balcony, included various traditional dances such as syrtos, kalamatianos, and pendozali, with attendees, including mayors and community leaders, joining in the revelry. The scene was described as chaotic yet joyous, with individuals dancing, singing, and reciting poetry, while Venizelos observed with delight, smoking a cigar:

The music placed in the balcony… performs anthem marches and dances. Two or three fustanella-wearing delegates rise with their meal half-finished and begin the dance. Mr. Venizelos is watching the dancing … .

…And the feast begins. The music [band] plays [the] dances, syrtos, kalamatianos, tsamikos, pentozali. Mayors, community leaders, officers, citizens, official and unofficial, are caught in the dance. Now the general Mr. Nider is leading the dance, soon the fez-wearing Turk from Drama Kotza-Emir, soon a fustanella-wearing delegate, then Mr. Koundouros, then a vraka-wearing delegate, then a tuxedo-dressed gentleman, then a valiant delegate from Epirus with his black cap. It is impossible to describe what is happening at this hour inside the Zappeion. Some are dancing, others singing, one man on a chair is reciting his poem to Mr. Venizelos, Mr. Zacharias Papantoniou on another chair is sketching pictures of the mayors and presidents of communities, others are embracing, others are kissing, others are clinking their glasses. And Mr. Venizelos, smoking a cigar, is watching the spectacle with glee.

Eleftheros Typos (Anonymous 1920h) provided an even more lyrical account, characterizing the event as a “genuine Greek feast of the mountains of Roumeli and the plains of Thessaly.” The newspaper offered a vivid portrayal of the local costumes worn by the representatives, including the fez of the Turkish representative from Drama. The orchestra began to play folk songs, stirring the Greek spirit among the participants:

…In the midst of the general excitement the orchestra then begins to recite folk songs to the sounds of which the Greek soul of the participants is excited. The excitement and joy reach its peak. Nothing can now hold back the congregants, who, setting aside the tables, ‘give way’ and begin the Greek dances to the sounds of the orchestra.

In a few seconds, the gala dinner, which had been a few moments ago of European etiquette and solemnity, was transformed into a genuine Greek feast of the mountains of Roumeli and the plains of Thessaly.

Formalities are being disregarded. The Greek soul now dominates. Under the dazzling light of the large electric lamps the clear air of the Greek mountain and the aura of the famous Greek beaches are blowing. So genuine is the Greek environment that one thinks that in that marble environment one breathes the thyme of the Greek mountainside and the fragrance of the pines of Parnassus and Orthis. The excitement is indescribable. Gentle mayors, frugal presidents of communities, living icons of Greek beauty and the Greek soul, eloquent, are placed at the head of the syrtos and as they dance, they make the ground creak under their feet. The orchestra on the gallery literally rages. The spectacle of the dance is most picturesque. The white multicreased fustanella, the symbol of Greek valour, is succeeded by the glorious Cretan vraka, the picturesque garment of our islanders, the fez, and so on.

The whole of Hellenism, embraced, fraternized, loved in a mosaic of national colors, celebrates the resurrection of the race. All the national dances are danced, from the syrtos and the Kalamatianos to the spectacular Pendozalis.

The account from Eleftheros Typos (1920h) vividly captures a transformative event that transcends formalities, evolving from a structured gala dinner into a vibrant celebration of Greek culture. The orchestration of folk songs ignites a collective enthusiasm, prompting participants to engage in traditional dances that embody the essence of Greek identity. The rich imagery of local costumes and the evocative atmosphere—reminiscent of Greece’s mountainous landscapes and coastal beauty—further enhance the experience. This celebration serves as a poignant reminder of Hellenism’s unity and cultural vitality, as diverse representatives come together to honour their shared heritage through dance and camaraderie.

Embros (Anonymous 1920i) reflected on the vibrant attendance of over a thousand individuals in diverse local attire, emphasizing the cultural importance of Cretan music and dance, particularly the Pendozalis. The article also mentioned the Roumeliotes, delegates from the broader Roumeli region—historically linked to the first Greek State of 1830—who performed traditional dances, albeit mistakenly conflating two folk songs, thereby illustrating the intricate dynamics of regional identities within the national context. The Kalamatianos dance, emblematic of the Peloponnese (Morias in Greek) and also historically linked to the first Greek State of 1830, was led by Mayor Spyridon Patsis, inciting enthusiastic applause from the audience.

The cultural symbolism embedded in the Zappeion festivities highlights the role of music and dance in reinforcing Greek national identity. Folk dances such as the syrtos (from Central “Old” Greece) and pendozalis (from Crete, the “New Lands”) symbolized regional diversity while simultaneously promoting a unified Hellenic identity. As noted by Kitromilides (Reference Kitromilides and Kitromilides2006: 382), Venizelos’s appreciation for folk traditions, especially those rooted in his Cretan heritage, reflects his efforts to use cultural expressions as a means of fostering national cohesion. The prominence of Cretan cultural elements during the reception further underscores this connection, with fifty Cretan mayors in traditional attire participating in the celebrations.

The Thessaloniki newspaper Makedonia (Anonymous 1920j) also chronicled the musical celebration at the Zappeion, capturing the fervour surrounding Venizelos’s arrival, where crowds enthusiastically cheered and shouted “Àngkyra.”Footnote 5 Seating arrangements placed Venizelos centrally among military leaders, prompting cheers of “Long live the Triumvirate,” a nod to the Provisional Government period in Thessaloniki (1916–1917). The orchestral performance featured folk songs, leading to spontaneous dancing initiated by Venizelos:

During the meal the music plays folk songs […] Afterwards the music plays a national song. The Mayors and the Presidents of the communities of Thessaly and Central Greece rise as a cue and dance, Mr. Venizelos giving the cue. Then the music recalls the Cretan syrtos. Fifty Cretan mayors, wearing the national uniform, dance while the conventioneers engage in all sorts of demonstrations in favor of the great island. The Cretan syrtos at the request of the conventioneers was resumed three times. The meal was served until the tenth, with the musicians playing various exquisite pieces. The meal was concluded, the national anthem being recited. All the conventioneers and crowds of people accompanied Mr. Venizelos in a procession to his home.

In conclusion, the celebrations surrounding Venizelos’s reception not only honoured Greek cultural heritage but also functioned as a strategic platform for reinforcing national unity and political allegiance. The vibrant expressions of joy captured in newspaper accounts illustrate the significance of such events in shaping national identity and political discourse in Greece during this period. However, these festivities also reveal the complexity of political expressions, where contrasting sentiments of loyalty and dissent coexisted. The spontaneous expressions of Cretan identity, the communal dances, and the celebratory atmosphere in favour of Venizelos underscored his influence. At the same time, the accounts of demonstrations, such as those highlighted by Eleftheros Typos (Anonymous 1920k), reveal how such events became stages for both celebration and subtle forms of dissent.

As we transition to the next chapter on the soundscapes of popular dissent, it is crucial to acknowledge the relationship between political expression and cultural identity during Greece’s tumultuous 1920s. The national Epinikia marked a moment of international triumph while simultaneously serving as a pivotal moment for Antivenizelists to voice their opposition to the Venizelist regime. The lifting of martial law facilitated a resurgence of public dissent, expressed through political demonstrations and the accompanying rich soundscapes of music and dance. The contrasting narratives in the press—ranging from fervent support for Venizelos to suppressed royalist sentiments—underscore the complexities of national identity amid political turmoil. This chapter will further explore how auditory expressions and public performances became essential tools for both resistance and celebration in a society grappling with its fractured identity.

The pre-electoral clash: soundscapes of dissent

In contrast to the vibrant depictions of festival celebrations associated with Venizelos and his party, the reality on the streets of Athens was marked by violence, as various groups, particularly those aligned with the Antivenizelist camp, faced brutal assaults from Venizelist supporters. This group included a diverse array of individuals—supporters of the monarchy, conservative party members, and politically unaffiliated citizens—who expressed dissent against the government’s policies. The election campaign, and the broader conflict between the two political factions, effectively commenced during the two-day festivities, a situation exacerbated by the Antivenizelist party’s newfound “freedom” following the repeal of Military Law. Pavlos Petridis (Reference Petridis2000: 50) notes that the Antivenizelists perceived this repeal as “manifestly delaying” the electoral process leading up to the General Elections on 1 November. Nikolaos Papadakis (Reference Papadakis and Venizelos2017: 752) further elucidates that this period was characterized by “intensity and cruelty,” which reignited civil passions and reaffirmed societal divisions.

Figure 5. Assembly of the supporters of Eleftherios Venizelos [Digitized Collections of Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive (E.L.I.A.)—Cultural Foundation of the National Bank of Greece 1920d].

Despite the media’s emphasis on the festivities at the Panathenaic Stadium and the commemoration of the Treaty of Sèvres, the Politeia (Anonymous 1920l) newspaper took the opportunity to address the “recovery of the liberties of the Greek people” and the effective abolition of Military Law. The author recounts an incident where a “renowned itinerant poet … sang his Venizeliada [Venizelos’s praise], causing disturbance among the gathered crowd.” In a moment of sarcasm, the author reflects on the prior three years of enforced silence, stating,

It is not enough now for three years that we were not allowed to express our conscience and were forced to sing whatever songs they wanted! …Well, enough is enough!

This expressive trait incited a reaction from a Guards officer, who called for the arrest of a disgruntled citizen, only to be interrupted by other Antivenizelists who seized the moment to express their newfound freedom:

-

– “Hooray for Eliá!” The signal was given.

-

– “Long live Elià!,” everyone was now shouting. “Down with Àngkyra. It has roared at us. Down! Down! So much for martial law. Long live freedom.”

Two days later, Politeia (Anonymous 1920m) reported on a “spontaneous rally” during a general assembly of the People’s Political Association, highlighting the opposition’s now-unrestricted ability to express their political views following the repeal of martial law. Concurrently, a protest in Vathi Square echoed sentiments of support for “Elia,” with demonstrators chanting:

-

– “They are ours!”

-

– “Elia!”

-

– “Elia a thousand times …”

-

– “Long live Gounaris!”

-

– “Long live the Opposition!”

As the “reactionary movement” gained momentum, citizen groups joined the demonstration, contributing to an increasingly vibrant atmosphere of dissent characterized by chants and the performance of the National Anthem, albeit excluding the Royalist Aetos anthem. The demonstration, described as a mass gathering, advanced towards Syntagma Square, where the atmosphere was charged with cries of “Down with the tyrant!” and the chant of “elià” resonated throughout the crowd.

Press accounts reveal how the repeal of Military Law enabled public dissent, creating a vibrant soundscape of opposition. Chants of “Elià” and other political chants echoed through Athens, marking a stark contrast to the orchestrated celebrations of the Venizelist government. These soundscapes of dissent reflect Jacques Attali’s (Reference Attali and Massumi1985) theory of noise as a disruptive force within political and social spaces. According to Attali, noise signifies disorder and rebellion against established authority. In the case of Athens in 1920, the chants of “elià” and Antivenizelist slogans disrupted the controlled soundscapes curated by the Venizelist government, transforming public spaces into arenas of conflict and resistance.

Amidst the festivities on 14 September, Politeia (Anonymous 1920n) also chronicled a religious procession, during which opposing voices advocated for “freedom” from “tyranny,” with the crowd exclaiming:

-

– “Long live freedom!”

In another article, Politeia (Anonymous 1920o) criticized the “terrorism” associated with Venizelism, highlighting the violence perpetrated by “hordes of stick-carrying” supporters against Antivenizelist citizens. The newspaper recorded threats from these supporters directed at demonstrators holding olive branches, stating:

-

– “Cheer Hurray for Venizelos, you fool!”

Despite this, the populace maintained a passive resistance, with widespread protests echoing “Down with the tyrant….” Similar incidents of violence were reported across various districts, including Stadiou Street and Omonia Square, where “hordes of stick-carriers” gathered to perform music while engaging in exchanges of chants with dissidents.

In response to the escalating tensions, the Police issued a decree on 18 September 1920, aimed at regulating demonstrations. This decree required prior approval from the Police Authority for any public gathering, designated specific routes for demonstrations, and prohibited assemblies in Syntagma and Omonia squares. It also restricted demonstrators from carrying weapons and outlawed provocative counterarguments. The press subsequently detailed the electoral and political conflict in Athens leading up to the pivotal elections at the end of October, while also covering the deteriorating health and eventual death of King Alexander.

As we draw closer to the conclusion of this analysis, it is essential to acknowledge the contrast between the celebratory narratives propagated by the Venizelist faction and the grim realities faced by the citizens of Athens during this politically charged period. The vibrant festivities, often highlighted in media representations, served as a façade that masked the widespread violence and oppression experienced by the Antivenizelist community. Although the repeal of Military Law was heralded as a victory for freedom, it ignited a fierce and often brutal struggle for political expression, evidenced by the escalating confrontations between opposing factions.

The contrasting soundscapes of Athens—joyful chants in support of Venizelos juxtaposed with defiant cries of “Down with the tyrant”—illustrate how political expression manifested through auditory experiences. Drawing from Attali’s concept of noise, these soundscapes reveal how dissenting voices disrupted the sonic order imposed by the Venizelist government. These auditory expressions, marked by chants, protests, and musical performances, became essential tools for both resistance and celebration, reflecting the fractured identity of Greek society during this transformative period. This analysis thus paves the way for a more profound examination of the repercussions of these events on Greece’s socio-political landscape.

Soundscapes, power, and historical transformation: concluding remarks

The contested soundscapes of the Greek National Schism (1915–1922) reveal the profound interplay between sound, power, and historical transformation during one of Greece’s most turbulent periods. This study’s reconstruction of the Venizelist victory celebrations of September 1920 demonstrates how curated soundscapes were employed for political mobilization, while counter-soundscapes emerged as acts of dissent, reflecting societal divisions and shaping collective memory.

Soundscapes were not passive reflections of events but active agents in shaping historical narratives. The Venizelist regime’s Epinikia festivities employed music, dance, chants, and symbolic performances to project Eleftherios Venizelos as the embodiment of Greek national aspirations, invoking ancient heritage to legitimize modern territorial ambitions. Counter-soundscapes of dissent, as theorized by Jacques Attali’s concept of noise, disrupted these curated narratives, reclaiming public spaces and asserting alternative political identities.

William Noll’s concept of cultural authority underscores the role of press narratives as “earwitness” accounts, which documented and shaped auditory experiences while reflecting the biases of their creators. These mediated sources offer invaluable insights into the emotional and symbolic dimensions of political events, bridging ethnomusicology and historical sound studies to reveal how auditory practices were culturally and politically situated.

James Mansell’s framework of historical acoustemology situates the Venizelist soundscapes as tools for reinforcing power through grand processions, anthems, and ritualized performances. Yet, as this study shows, counter-soundscapes of dissent emerged simultaneously, challenging authority and exposing the fragility of charismatic leadership. These auditory conflicts exemplify the cyclical nature of power struggles in Greek society, where soundscapes alternated between unifying narratives and acts of resistance.

The Venizelist celebrations of 1920 serve as a case study for broader patterns in Greek political culture. Similar uses of soundscapes can be seen in nationalist performances during the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) and Antivenizelist celebrations following the November 1920 elections. These moments demonstrate how music and soundscapes have historically been used as tools of political mobilization and identity formation, reflecting ongoing tensions between state control and popular resistance.

Moreover, the insights gained from this historical case study resonate with contemporary political mobilizations, where sound continues to play a crucial role in shaping public discourse and collective memory. Chants, anthems, and auditory expressions remain central to modern protests and political movements, illustrating the enduring power of sound in contesting and transforming societal narratives.

In conclusion, the contested soundscapes of the National Schism highlight the central role of auditory experiences in shaping political realities and historical memory. Future research in historical sound studies should expand its focus to include other socio-political conflicts and cross-cultural comparisons, exploring how soundscapes mediate power dynamics globally. This study underscores the need for interdisciplinary approaches that bridge ethnomusicology, history, and political science, offering frameworks for understanding the enduring impact of sound in shaping societal transformations. By reconstructing these soundscapes, this study reveals the emotional, symbolic, and performative dimensions of political events, offering valuable insights into the transformative power of sound in past and present socio-political contexts.