Introduction

Let’s say that ‘universalism’ is the view that God will ensure every creature eventually enjoys heaven with God forever.Footnote 1 Let’s say that ‘traditionalism’ is the view that God allows some creatures to be tormented and left alone in hell forever because those creatures freely chooses to be tormented and left alone in hell forever.Footnote 2

Some traditionalists think that universalism faces an important problem. They think universalism fails to explain why we have earthly lives. Earthly life contains suffering. And although there are unique earthly goods that can only be had by allowing that suffering, those goods are nothing compared to the goods enjoyed in heaven. So by spending time on earth first, we miss out on the even better goods we would have had if God had started us off in heaven instead. If God is going to ensure everyone goes to heaven eventually, as universalists maintain, there is no point in God starting us off on earth first. This argument is defended by Murray (Reference Murray1999, pp. 56–8) and Rooney (Reference Rooney2025, p. 123).

I identify two problems for this argument.Footnote 3 First, given the endless and infinitely valuable nature of heaven, time on earth doesn’t result in a deduction of time or goods received in heaven. It would be one thing if, for each year on earth, we got one year less in heaven along with fewer total heavenly goods. But we do not. We get the same amount of heavenly goods whether we start on earth or heaven first. Second, given origin essentialism, we couldn’t have started anywhere but earth. God might have been able to create duplicates of us that started out in heaven. But those duplicates wouldn’t be us. So if God wanted to create us, in particular, we had to begin our existence on earth with its entire causal history of suffering.

An earthly life does not result in missing out

Murray (Reference Murray1999, pp. 56–8) argues that earthly creatures are missing out by getting an earthly life. They experience some evils. They experience some unique earthly goods. But no matter how good an earthly life is, it won’t measure up to a heavenly existence. So it seems pointless for God to give us an earthly life. Murray says:

The universalist might respond here that earthly evils are not without purpose since… they are necessary conditions for procuring outweighing goods. However, the universalist continues, the outweighing goods in this case are found not in the afterlife, but in the earthly life itself… . Notice, however, that this response misses the point… . The intrinsic good of the earthly life, on the [universalist] scheme, seems outweighed by the good one would have experienced if one has been created enjoying perfect communion with God from the beginning. Why would God prefer to have us spend our first seventy or so years of existence in this earthly phase, enjoying a measure of intrinsic good but with the accompanying evil required to secure it, rather than positioning us in such a way that these years are spent in perfect communion with Him in heaven? After all, any earthly goods obtained would pale in comparison with the goods achieved by spending those years in this way.

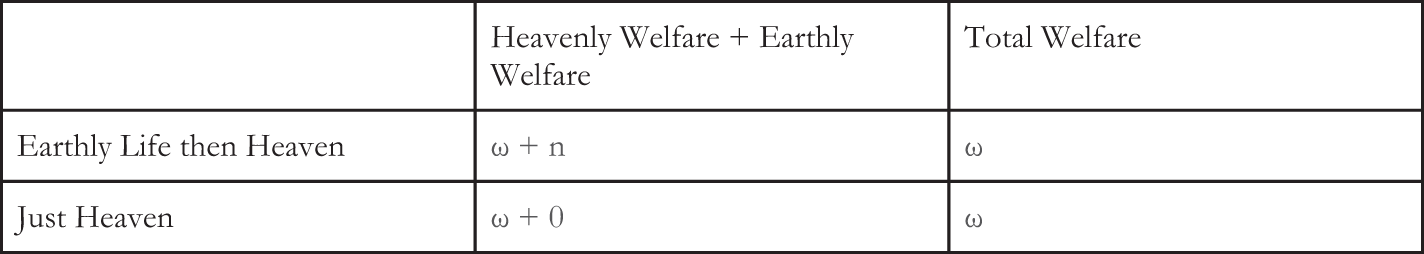

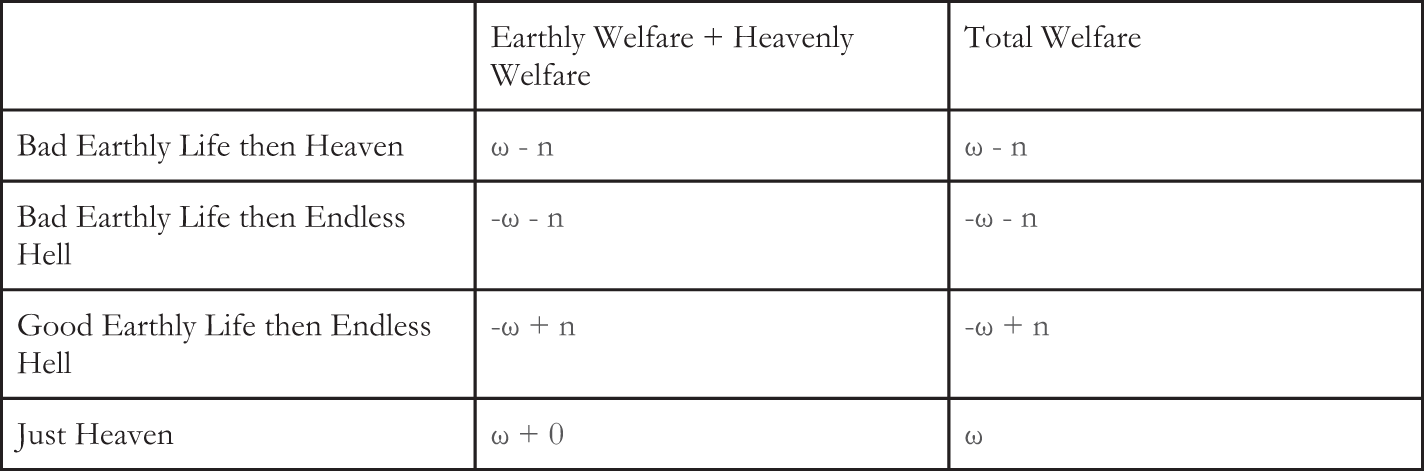

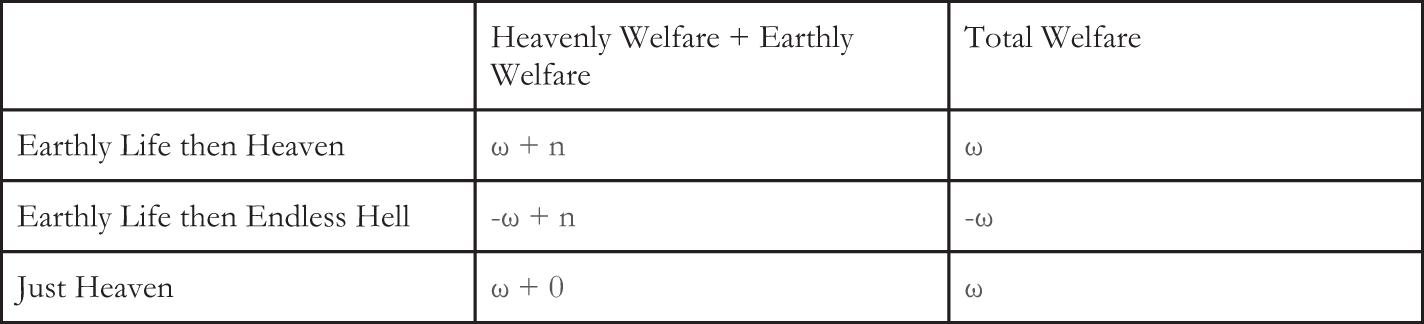

I think this is mistaken: Assume standard arithmetic is the correct way to describe a subject’s overall welfare level in infinite contexts. In that case, Murray is underestimating the value of heavenly connection with God. You are in heaven with God forever. And you get an infinite amount of welfare from your intimate connection with God. Let’s say that n is equal to the finite welfare level of a creature’s earthly life. Then God’s options, given universalism, for the creature are described in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Heavenly absorption of finite goods.

Whichever option God goes with, the creature’s overall welfare level is the same. The creature’s connection with God is so infinitely wonderful that adding earthly life or suffering just doesn’t change that creature’s overall welfare. Furthermore, tacking on an earthly life at the beginning of a creature’s existence doesn’t change the infinite amount of heavenly goods the creature gets.Footnote 4

It would be one thing if, for example, heaven only lasted for a finite amount of time, contained only a finite amount of goods, and each year spent on earth resulted in a one year deduction from time in heaven. Then Murray might be right that a creature is missing out by spending time on earth before heaven. But that isn’t the way it works. Heaven lasts forever and provides creatures with the infinite good of intimacy with God. So a creature gets the same infinite amount of heavenly goods whether it spends 70 years on earth first or not. The creature isn’t missing out on anything.

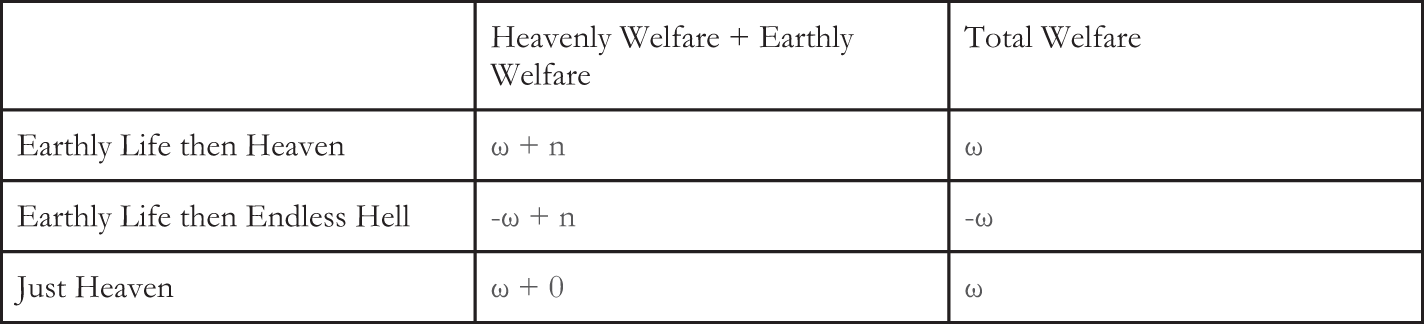

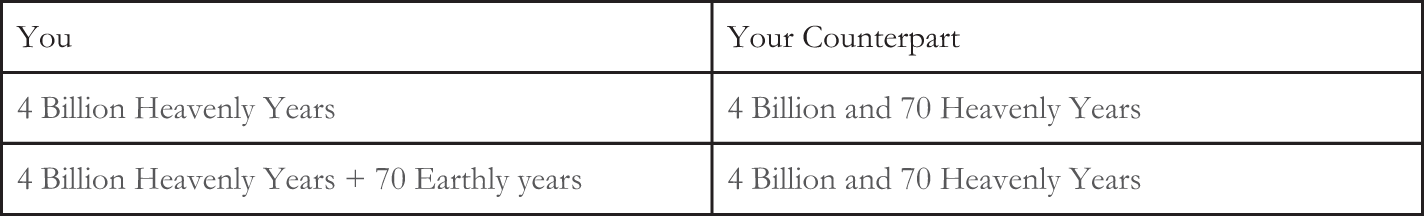

There is an additional point. For traditionalists like Murray, some creatures have an earthly life and end up in heaven. But other creatures have an earthly life but end up in hell forever. And so things look like as described in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Infernal absorption of earthly goods.

While the universalist needs only to explain why God makes creatures with the overall welfare level described in Row 1 of Fig. 2, the traditionalist has to explain that as well. In addition, the traditionalist must explain why some people have the overall welfare level described in Row 2 of Fig. 2. I think it is pretty easy to explain why God would give someone the welfare level represented in the first row. And it is certainly comparatively easier to explain welfare levels in Row 1 than Row 2. The universalist just has to explain Row 1. The traditionalist has to explain both rows. So, as I see it, if we go with standard arithmetic, there is no problem for universalism and a big problem for non-universalism.

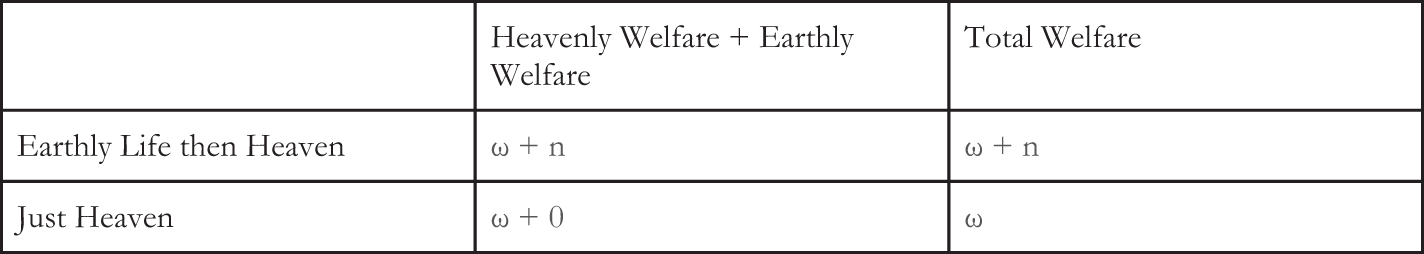

Not all philosophers of religion think that welfare levels in infinite contexts should be calculated using standard arithmetic. Some figures such as Jackson and Rogers (Reference Jackson and Rogers2019), Chen and Rubio (Reference Rubio2021), and Rubio (Reference Rubio2020) think that what happens on earth should be reflected in the math one uses to calculate one’s total overall welfare. They don’t like the idea that particular earthly goods or earthly suffering just get absorbed by infinity as they do in standard arithmetic. If these authors are right, we should instead use surreal arithmetic, an alternative in which infinities do not absorb finite numbers, to calculate overall welfare levels. And so, using surreal arithmetic in a context in which a creature has an overall good earthly life, God’s options for His creatures given universalism are more like as described in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Heavenly surreal non-absorption of earthly goods (good life).

In this case, earthly life plus heaven yields a higher total welfare level for a creature than just heaven. And so the universalist has an explanation of why God gives such creatures an earthly life before they enter heaven. If God gives the creature an earthly life, then that creature will get a higher welfare level than if God had just put the creature in heaven. That seems sufficient to ensure that it is not pointless for God to give creatures an overall good earthly life even if that life contains suffering and sin. The point is they get a slightly higher overall welfare level.

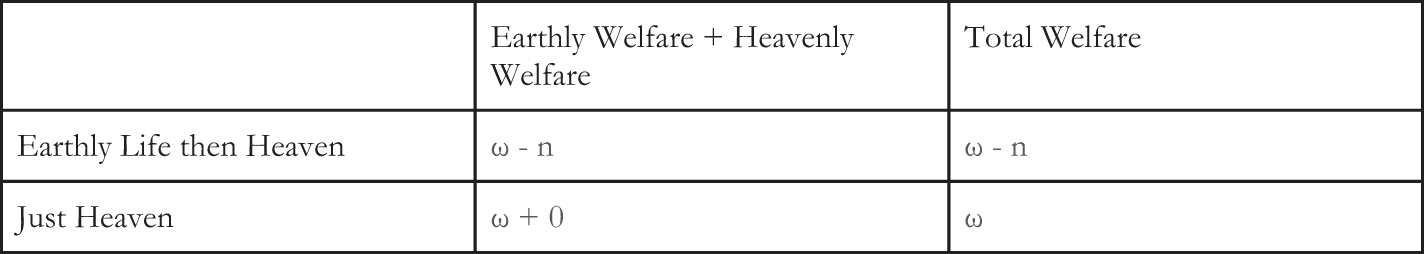

Now suppose we continue to employ surreal arithmetic but are evaluating a case in which a creature has a negative number for its overall earthly welfare level. Then, if we say that n, is that number, then surreal arithmetic will yield the following options as described in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. Heavenly surreal non-absorption of earthly goods (bad life).

And so the creature’s overall welfare level is lower than it would have been if God had just put the creature in heaven. And therefore the universalist, perhaps, has some explaining to do. But the traditionalist has at least as much to explain. There will be cases in which one has an overall bad earthly life but goes to heaven. So they have to explain that just as the universalist does. But they also have to explain cases in which someone ends up abandoned in hell forever. For the traditionalist, things look like as described in Fig. 5.

Figure 5. Infernal surreal non-absorption of earthly goods.

Assuming that some creatures have overall bad earthly lives, both the universalist and the traditionalist have to explain why God opts to give some creatures the welfare level in Row 1 rather than the welfare level in Row 4. But on top of that, the non-universalist has to explain why God allows some creatures to have the overall welfare levels as depicted in Rows 2 and 3. It seems like the traditionalist has a much harder task than the universalist. Universalism scores better.

So my view is this: Either we use regular arithmetic or surreal arithmetic when calculating welfare levels involving infinities. Either way, universalism scores much better than non-universalism. In the case of regular arithmetic, universalism comes away completely unscathed. In the case of surreal arithmetic universalism still has some explaining to do about why someone might have an overall bad earthly life. But it still scores far better than non-universalism. Earthly life does not take away anything from heavenly life. You don’t get less time in heaven from having an earthly life. You do not get fewer goods in heaven from having an earthly life. So it isn’t pointless to tack an earthly life onto the beginning of a heavenly life. Nothing is lost in doing so.

I have been assuming that time and welfare level in heaven is infinite. Suppose instead that time and welfare level in heaven is not infinite but merely finite and indefinitely extended. As Mawson (Reference Mawson2020) argues the earlier figures ‘represent a state of affairs that will never be realised, but rather one towards which reality tends… given we will never actually have lived an infinite time, the amount of meaningfulness our lives will ever contain is always going to be a potential infinity, not an actual infinity, i.e. it will always be finite’. So on this sort of view, you will continue in heaven without limit. But the time you spend there will always remain finite. And the amount of good you get from enjoying God’s presence will always remain finite. In that case, your first day in heaven would have been day 70 years + 1 if you had not started on earth, and more generally day n would have been day 70 years + n for all n if you had not started on earth.

One might wonder whether the considerations I raise above apply, given this alternative picture of heaven and its associated heavenly math. I think they do apply. Here, I will introduce an appropriate argument by Mawson (Reference Mawson2020) for other purposes. Pick any finite amount of time that one might spend in heaven, say, 40 billion years. Consider your counterpart who started out in heaven rather than on earth 70 years ahead of you. Suppose she has been in heaven for 40 billion years. And so you have been in heaven for 70 years less than her. I see no problem with this. In 70 years you’ll have the same welfare level as her plus whatever you got on earth. Maybe you’ll always be 70 years behind her. Nevertheless, for any finite welfare level that anyone reaches in heaven, you will at some point have that welfare level. For any finite welfare level that you would have reached if God had started you off in heaven 70 years earlier, you will still reach that welfare level. Again, it would be one thing if any amount of time on earth was deducted from your total amount of time you will eventually get in heaven. But your time in heaven is indefinitely extended. It keeps going. For any finite amount of time you may wish to spend in heaven, you will get it no matter how much time you spent on earth before going to heaven. You will just get it a bit later.

There is an additional consideration. Consider two things God might have done in creating you. God might have just created you in heaven 70 years after your counterpart. Or, God might have done what God actually did and have given you an earthly life beforehand. So the possibilities look as described in Fig. 6.

Figure 6. Heavenly indefinite extension.

There is no problem with God just starting you out in heaven by creating you 70 years after your counterpart rather than at the exact same time as your counterpart. The only relevant difference between God creating you 70 years later in heaven and what God actually did is that God tacked on an extra 70 good earthly years before that. And that gets you an even higher total welfare level than you would otherwise have had if God started you off in heaven 70 years later and skipped earthly life altogether. So the argument is this: It is not problematic for God to create you and your counterpart in the way described in Row 1 of Fig. 6. If that is not problematic, then God creating you and your counterpart as in Row 2 of Fig. 6 is not problematic either.

A different way to put the point: This is just the problem of no best world. For any amount of time God gives you in heaven, He could have started you off in heaven earlier and given you more. For any amount of finite goods, He gives you at each moment in heaven He could have given you a larger finite amount of goods at each moment. There is an interesting puzzle about what to make of this. But that puzzle is not something that universalism adds to theism. It is something universalism inherits from theism. And so the worry about universalism isn’t independent of this other worry about no best world.

Humans could not exist without an earthly life

Murray’s argument plays an important role in Rooney’s (Reference Rooney2025) recent defence of traditionalism. Rooney (Reference Rooney2025, p. 123) endorses this argument:

Michael Murray has raised an issue for universalism that the earthly life seems gratuitous on a universalist picture of what God needs to do for us, as God could have beatified us at the first moment of our existence, and thereby prevented many gratuitous evils (among which would be the possibility of sin). Thomas Talbott responded to these criticisms by suggesting that an earthly life full of obstacles was ‘a metaphysically necessary condition of our creation [emphasis original]’. That is, apparently, God must allow sin if He wants to create free persons. However, this too seems overly strong (and may not be what Talbott means), as it would imply persons cannot exist without sinning at some time or another. Further, there is potentially theological evidence which contradicts this: sin was not metaphysically necessary for at least some created persons to achieve union with God, as with the Blessed Virgin Mary, who was preserved from sin, from the first moment of her conception, and never committed any sin (according to Orthodox and Catholic dogma) – nor did any of the blessed angels ever sin.

Rooney is right to criticize Talbott for being short on details. But it is possible to develop Talbott’s point in a way that is sound. Assume Mary was preserved from sin for her entire existence as the relevant traditions claim. Then distinguish between two claims:

1. Necessarily Mary exists only if Mary sins.

2. Necessarily Mary exists only if every sin in her causal history happened.

There is a way of developing Talbott’s point that commits him to only 2 and not to 1. In Naming and Necessity, Kripke discusses some scenarios in which the circumstances surrounding the birth of Elizabeth II are altered. In one scenario he considers, her birth is altered so that a different sperm and egg meet than the ones that actually met and formed into her. Kripke (Reference Kripke1980, p. 113) claims that to alter Elizabeth II’s origins in this way would be to alter her origins in such a way that she never existed. Kripke endorsed origin essentialism according to which:

If something originated in a certain way, then it could not have had another origin that was too different.

Leibniz (Reference Leibniz1967, p. 128) substantially anticipated origin essentialism as well as the use Parfit (Reference Parfit1984) made of a similar thesis to generate the non-identity problem. He argued that if the evils in our past were removed, we would not have existed:

if God had done that, sin having been taken away, an entirely different series of things, entirely different combinations of circumstances, persons, and marriages, and entirely different persons would have been produced and, consequently, sin having been taken away or extinguished, they themselves would not have existed. They therefore have no reason to be indignant that Adam and Eve sinned and, much less, that God permitted sin to occur, since they must rather credit their own existence to God’s tolerance of those very sins.

Robert Adams (Reference Adams1979, p. 54) and (Adams Reference Adams1972) has discussed this idea:

Leibniz is right about this. Even if I could have existed without some of the evils of the actual world (for example, those that will occur tomorrow), I could not have existed without past evils that have profoundly affected the course of human history. My identity is established by my beginning. It has been suggested that no one who was not produced from the same individual egg and sperm cells as I was could have been me (cf. Kripke, [2]: 312–4). If so, the identity of those gametes presumably depends in turn on their beginnings and on the identity of my parents, which depends on the identity of the gametes from which they came, and so on. It seems to me implausible to suppose that the required identities could have been maintained through generations in which the historical context differed radically from the actual world by the omission of many, or important, evils.

Vitale (Reference Vitale2017, Vitale Reference Vitale2020) and Hill (Reference Hill2022) think that this idea can be developed into a full blown theodicy. But for our purposes, we need not make the extreme claim these authors do in suggesting that this supports theodicy. We only need to explain why there might be a point to earthly existence and why Talbott’s vague suggestion about that point wouldn’t contradict the dogma about Mary that concerns Rooney. So the important point is just that the causal history leading to one’s origin is essential to that creature. Change the causal history about that creatures origin, and you change whether it is that creature that originated. You might get a duplicate of the creature. But you won’t get that creature in particular.Footnote 5

So, given origin essentialism, God couldn’t have gotten any earthly creatures unless He created them on earth and included suffering in their causal history. Each individual creature might be able to exist without suffering. But it could not exist without prior suffering. And it is part of a process that enables creatures to exist that could not otherwise have existed. Such creatures benefit from this process. And they contribute to it. So the point of earthly existence and suffering is to get creatures that could not have otherwise existed.

Contrast two claims:

For each person who actually exists, God could have preserved that individual person from sin in the way He preserved Mary from sin.

God could have made a world that contains every person in the actual world but in which none of them sin.

When I said ‘God could have done that for everyone’ I meant to endorse the former claim rather than the latter. And so origin essentialism entails:

For each person who actually exists, God could not have created that person if no one in that person’s causal history had sinned.

It may be that Mary was preserved from sin in her earthly life. It may be that she was immaculately conceived. But there are actual sins in the causal history leading up to her immaculate conception. Adam sinned, for example. Her parents sinned before she was born. Change whether these sins occurred, and you change Mary’s origin. Given origin essentialism, the result would not be Mary but at best a mere duplicate of Mary.

This vindicates the view that earthly life is necessary for our existence. If God were to start a creature off in heaven rather than on earth, that creature’s origin would be different. And it wouldn’t be that creature but a mere duplicate. Without a long earthly history of billions of years and stretching back to the Big Bang, no actually existing human would exist. While individual creatures could then be whisked away to heaven immediately after they begin to exist, doing so would prevent creatures later in the relevant causal chain from existing. So the point of an earthly life is to allow the set of actual humans God created to exist. This does not in any way run afoul of the relevant dogmas concerning Mary that Rooney is concerned to preserve.

Remember, the puzzle here is supposed to be independent of the problem of evil. While I myself think the above considerations are sufficient to solve the problem of evil, you may have some lingering doubts. Suppose your doubts are correct. If so, that is beside the point. The real question is this: After the considerations raised, do you think there is any problem leftover other than the problem of evil? If so, what is it? If we assume that the problem of evil is solved, what unique problem would remain for the universalist? Why isn’t it good enough for the universalist to simply maintain that God wanted to create us and that He couldn’t have done so if He had started us off in heaven rather than on earth? If your answer requires invoking the problem of evil, then I have done my job.

Gratuitous evil

A referee points out that Murray’s worry stems from a concern about gratuitous evil. As Murray characterizes gratuitous evil in the following way:

(NGE) An evil E is nongratuitous if, and only if, (a) there exist, some outweighing intrinsic good G such that it was not within God’s power to achieve G without either permitting E or permitting some other evil at least as bad as E and (b) there is not some further intrinsic good G*, which is both exclusive of G and greater than G, which could have been secured without permitting E or some other evil at least as bad as E.

(GE) An evil E is gratuitous if, and only if, it is not non-gratuitous.

He says:

We can begin to frame this first problem for [universalism] as follows. On the [universalist] picture, all human beings end up in perfect communion with God, enjoying the beatific vision forever. This entails, however, that one’s fate in eternity is entirely independent of the choices a person makes and the beliefs a person adopts in the earthly phase of their existence. Thus, the evils that one experiences in the earthly life are gratuitous. Why, one is led to wonder, would God put us through such a pointless exercise, an exercise filled with much misery, suffering, and travail, only in the end to invest the experience with no ultimate consequences or significance?

But the referee notes, I haven’t said anything about gratuitous evil yet. So, the referee reasonably wonders, how do my objections address Murray’s argument?

It is important to note that my objections to Murray’s argument are raised at a particular point in the dialectic. After giving his argument from gratuitous evil, Murray considers an objection on behalf of the universalist:

The universalist might respond here that earthly evils are not without purpose since, contrary to first appearances, they are necessary conditions for procuring outweighing goods. However, the universalist continues, the outweighing goods in this case are found not in the afterlife, but in the earthly life itself. Thus, while evils in this life do not affect my eternal destiny, they do affect the course of the earthly life itself and in this way earthly evils have their purpose in bringing about outweighing earthly goods. Notice, however, that this response misses the point of the original criticism. While the response offered here shows that the evils in the earthly life might satisfy conjunct (a) in the right half of the biconditional (NGE), it fails to satisfy conjunct (b). The intrinsic good of the earthly life … seems outweighed by the good one would have experienced… . After all, any earthly goods obtained would pale in comparison with the goods achieved by spending those years in this way.

So, the universalist objector Murray imagining says that earthly life isn’t pointless because there are all sorts of goods that God couldn’t have achieved without allowing people to suffer. Murray agrees and says this is enough to satisfy condition (a). But Murray thinks condition (b) remains unsatisfied. He thinks that this is because getting these lesser earthly goods results in missing out on better heavenly goods.

This is where my objections begin. Since Murray agrees that condition (a) is satisfied, my objections are intended to target Murray’s claim that (b) is not satisfied. My first objection is that (b) is satisfied because no one, given universalism, is missing out on any heavenly goods. They get the same amount of heavenly goods whether they first spend time on earth collecting the lesser goods or not. God deemed the lesser goods that you can only get with an earthly life worth picking up and tacking on to the even better heavenly goods that people are going to get anyway. God isn’t keeping track of time spent on earth and then subtracting the heavenly goods we get from that amount of time. We get an infinite amount of heavenly goods either way. So condition (b) is satisfied. There isn’t some better good we would get if only we did not spend time on earth first.

My second objection is that we wouldn’t exist if God didn’t have a policy of allowing earthly suffering. God can create duplicates of us in heaven with no causal history of suffering at all. But those duplicates won’t be us. So we aren’t missing out on any heavenly goods. Without God’s policy of allowing earthly suffering, we wouldn’t be around to enjoy heavenly pleasures. So there is a good for us that we can’t get without all this suffering – our very existence and the endless heavenly bliss that follows. Thus, condition (b) is satisfied. And the evils do not count as gratuitous given Murray’s definition.

A better world

The referee concerned about gratuitous evil objects:

It might (and here I stress might) be the case that this [stuff about origin essentialism] could show why sin and suffering is not gratuitous for the individual, but it does not show that God’s permission of this sin and suffering is not gratuitous globally. God could have made an even better world by creating only individuals without such an earthly life. And that makes the suffering of those with earthly lives (globally) gratuitous.

Another referee raises a similar objection:

The existence of sinful Mary, [that is, Mary with the sinful people in her causal history], has closed the door on many other possibilities. Possibilities that could just as well have led to a better world (which should be God’s primary concern).

I have four responses: First, I deny the intuition that it is wrong to create one set of people when one could have instead created a different set of people with even better lives leading to an even better world. I think there is a well-motivated error theory for the relevant intuition. And so the universalist may reject it. The error theory is found by consulting the literature on the non-identity problem. Consider:

Disability: Anne wishes to have a child. She may select an embryo that will grow to develop a disability or a different embryo that will never have a disability. Either way the embryo will end up with a very good life. But the particular disability in question would yield a lot of suffering that the person arising from the non-disabled embryo would not experience. Anne chooses the disabled embryo only because she desires the attention she would get from taking care of a disabled child.

People report having the intuition that Anne has wronged the person who develops from the embryo. But it is difficult to explain how it could be wrong. The person who develops from the embryo is better off because he would not have existed if Anne had not picked the embryo that would turn into him. So the puzzle is to reconcile the claim that Anne wrongs him with the fact that he is better off because of what she has done.

I agree there is something wrong that Anne does in Disability because she is using the child to get attention. Something is wrong with her motives. But once that is corrected, once it is stipulated that she just wants to love the disabled child and has no selfish desire for attention, once it is stipulated that the child has an exceedingly good life that is well worth living rather than a horrible life, I think that what Anne does is permissible and that the intuition some people have that what she does is wrong is unreliably formed.

There have been many heroic attempts to solve the non-identity problem in a way that preserves the relevant intuition. But in the end, they never ring true to me. The problem always remerges and remains unsolved (Boonin (Reference Boonin2014)). Or the solution commits one to an even more counterintuitive result. The older I get, the less I have the intuitions about such cases that I am told I am supposed to have. And when non-identity cases like Disability are carefully stipulated in the right way where everyone has the right motives and the alleged victim has an exceedingly good life that is well worth living, it now seems obvious to me that the subjects of such cases do not act wrongly and the intuition most people report having otherwise is mistaken and in need of reform.

So I think that careful reflection on the non-identity problem gives us an error theory for the intuition that it is wrong to create one set of people when one could have instead created a different set of people with even better lives or leading to an even better world. For this reason, even if we grant the assumption that the other lives and worlds are better than our lives and the actual world, it still comes out as permissible for God to make our world instead of one of those other worlds. As Vitale puts it:

Because God is gracious, his desire to love us is not on the condition that we are more valuable than other creatures he could have created or that our existence allows for the maximization of overall world value. On the contrary, reflection on the virtue of grace suggests that desiring to create and love persons vulnerable to significant evil can be just as fitting with the abundance of divine generosity as desiring to create and love the most valuable, most useful, or most well-off persons God could create.

This seems exactly right to me. So one reply I have to the objection in question is that even if our lives and our world is not as good as other lives and worlds of duplicates of us that God could have made, that is not a reason why it would be wrong for God to create us and our world. Some people have the intuition that it would be wrong. But there is a well-motivated error theory for that intuition. So the universalist is free to reject it.

My second response is that I reject the assumption that a world with duplicates of ours that never suffer is better than the actual world. The world is not better in virtue of the value of the lives of its inhabitants. Go back to the figures earlier in the paper. If standard arithmetic is the right way to measure welfare, our lives are just as good as our duplicates in the other world. If surreal arithmetic is the way to do it, our lives are even better than the lives of mere duplicates who start off in heaven. Furthermore, as Metcalf (Reference Metcalf2020) argues, rags-to-riches worlds are valuable and good in a way that riches worlds are not. It is good for creatures to work together to overcome and conquer evil.Footnote 6 It is good for them to be part of making the world beautiful and good rather than simply starting off in a world that is already as beautiful and good as can be. And so our world is better in this respect than that of our mere duplicates who start off in heaven. Perhaps the relevant types of worlds are good in incommensurable ways, so that neither surpasses the other. Or perhaps our world is just better simpliciter. Either way, I deny that our world is of less value than a world with duplicates that never sin or suffer.

Third, I agree that after allowing the first sin, there are specific people God can no longer make descending from that particular causal history. But the objectors are not worried about missing out on those particular people. The objectors are worried about an allegedly better world that contains no sin or suffering. This is where I disagree with the readers on two points. First, take whatever world God might have gotten by preventing the relevant sin. He can make a causally isolated part of this world that contains duplicates of everything in that world. Just as big as the world that the objectors want and containing all the sinless creatures the objectors want. Indeed, God can create an infinite number of such causally isolated duplicates of us. Then, after creating an infinite number of such duplicates, God may wish to create a new sort of causally isolated universe, one that includes the unique goods that can only come from allowing the existence of sin and suffering. So take whatever is valuable about the world God could have made by preventing sin in Mary’s causal history. God can get that value an infinite number of times over with duplicate causally isolated universes. Then, God can add to that our causally isolated part of the world that has the relevant unique goods such as us and our rags-to-riches story. Here is another way to think about it: It is good enough for God just to create an infinite number of the relevant causally isolated duplicates. Tacking on our causally isolated part of the world just makes the world even better. So it is good enough for God to tack on our causally isolated part of the world. Take whatever number of the relevant causally isolated universes you want, tacking us on doesn’t prevent God from adding that number of universes.

Fourth, I remind the reader that my job in the paper is not to do theodicy but to show that universalism does at least as well as traditionalism with respect to the problem at hand. Suppose one does not like my first three responses. The relevant question is this: Does the universalist do at least as well in addressing the problem as the traditionalist? They clearly do. The traditionalist view is that the actual world is one in which a lot of people end up in hell forever. The universalist view is that everyone ends up in heaven forever. The universalist only has to explain suffering and sinning at the start of our existence. The traditionalist has to explain eternal suffering. The universalist scores at least as well as the traditionalist.

Another referee says:

Here’s a bold claim I’m not sure is right: the author’s arguments show only that God wouldn’t have reasons NOT to start creatures off in Non-Heaven … none of the author’s arguments show that God would have reasons TO start creatures who are capable of enjoying Heaven off in Non-Heaven. Does the author agree with this reviewer’s bold claim?

My view is that some but not all of the arguments show that God has a positive reason to create us rather than mere duplicates that do not suffer or sin. One of the arguments is that if we use surreal arithmetic to calculate welfare, a good earthly life results in a greater total welfare (ω + n) than heaven alone (ω). This provides a positive reason for God to create us rather than our duplicates. Another of the arguments is the idea that rags-to-riches world is better in at least some respects than a riches-to-riches world. It is beautiful and good to create creatures like us that can only start off bad and in conditions of suffering and then rise us to the heights of excellence and the delights of heaven. And this good is not present in riches-to-riches worlds. So that gives God a positive reason to create us rather than our duplicates.

Benatar

A referee says:

As people like Benatar have noted, a life that includes any harm is worse than never having a life… . If it is the same subject who experiences bliss in heaven that experiences pain and pleasure on earth, then it must be the case that the pain experienced on earth remains part of the subject’s life even if s/he experience future eternal bliss. Again following this point, we must ask whether that experience of earthly pain undermines the value–of-life overall, especially when compared to, say, not existing at all.

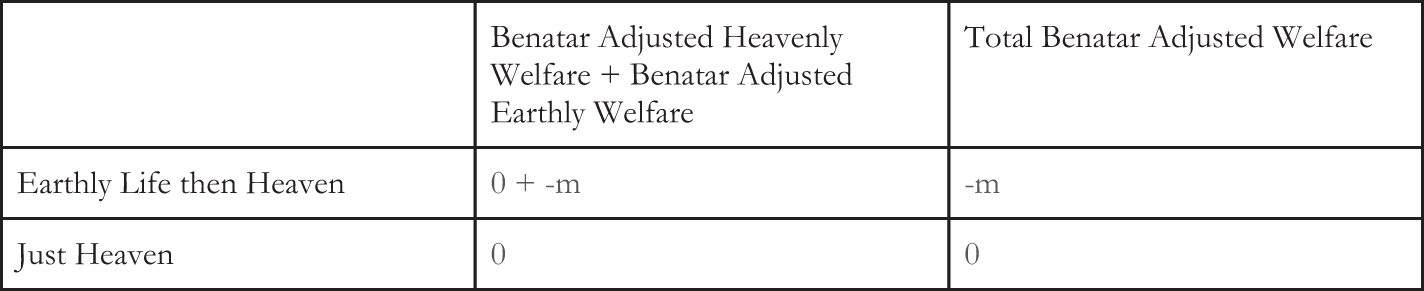

Benatar (Reference Benatar2006) holds that positive welfare is irrelevant when deciding whether creating someone will benefit them or harm them. Only pain matters. If someone will experience pain, then no matter how much pleasure they will get, they would have been better off never existing. Nor, as I understand it, will the person’s pleasure directly add to the value of the world. Let’s say that -m is the amount of suffering a person will experience in their earthly life before going on to enjoy eternal bliss. Then that is all that matters. Let’s say that ‘Benatar Adjusted Welfare’ is the total amount of pain one suffers and includes none of the goods that contribute to one’s welfare. Then the numbers for my earlier figures will look more like as described in Fig. 7.

Figure 7. Both of us knowing.

So Benatar’s view, as I understand it, implies that the welfare relevant for deciding whether someone is better off than not existing is -m if you put them on earth first and 0 if you start them off in heaven. So, if that is right, the person is worse off if God gives them an earthly life first.

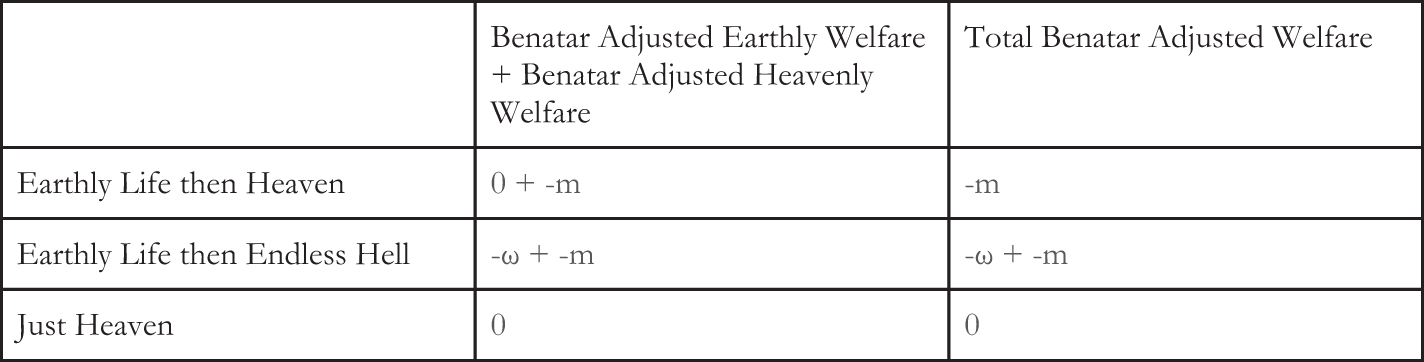

I remind anyone who is sympathetic to Benatar that my official job in this paper is not to do theodicy (even if I can’t resist the temptation to speculate about theodicy along the way). Instead, my job is to show that when it comes to whether earthly life is pointless, or whether the universalist has a problem with gratuitous evil, the universalist scores at least as well as the traditionalist. And so what is relevant is not just the numbers you get for universalism but how those numbers compare to traditionalism. And, if we follow Benatar and ignore any pleasure a subject might enjoy, things look like this for the traditionalist (see Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Love is a battlefield.

The universalist only has to explain the point of God giving people -m rather than 0 units of Benatar adjusted welfare. The traditionalist has to explain that as well as the point of God giving people -ω+ -m rather than 0 Benatar adjusted units of welfare. It seems like the universalist does far better. It seems like any story the traditionalist can give about why God gives people -ω + -m units of Benatar adjusted welfare can be appropriated by the universalist to explain why God gives people -m units of Benatar adjusted welfare. Thus, universalism does at least as well as traditionalism. And so I have done my job.

Still, I cannot resist expressing disagreement with Benatar. I know Benatar recognizes that his view is counterunitive. I will here register my own view that while Benatar takes well motivated counterintuitive results to radically restrict permissible creation, I instead take well-motivated counterintuitive results to open up wide vistas of previously unnoticed permissible creation.

Origin essentialism and the soul

A referee notes that the soul view seems to conflict with origin essentialism. Furthermore, many theists accept the soul view. So, the referee worries, accepting origin essentialism would require rejecting a view of personal identity that many theists accept. This sort of concern is often raised in conversation. And there is a recent paper Deshmukh and Janssen-Lauret (Reference Deshmukh and Janssen-Lauretforthcoming) that makes a similar point in the context of Hindu philosophy.

However, I think this is mistaken. While Kripke and others sometimes talk in ways that sound like they are identifying origin essentialism with the view that we could not have had different parents or that their view only applies to material objects, in their more careful moments, such figures articulate origin essentialism in a way that is compatible with the soul theory. For example, in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Ishii and Atkins (Reference Robertson Ishii and Atkins2023) say this:

Kripke (1972/1980, pp. 112–114) when he endorsed the view that an object could not have had a radically different origin from the one it actually had.

As Burgess (2013, p. 141) puts it:

Is Kripke committed to the claim that the concepts of reincarnation and so forth are not just false but incoherent? Well, perhaps the a priori principle in the background … is that my origins whatever they may be are necessary. That my only origins are my biological origins would then be an additional assumption that might be considered a scientific discovery by some, a scientistic prejudice by others.

Origin essentialism, then, is not the view that we have the exact parents we do or that we are material objects. Instead, origin essentialism entails that given the assumption that Elizabeth II, for example, actually originated from her parent’s sperm and egg combination and did not exist prior to the joining of that sperm and egg, she could not have had an origin that was too different and could not have instead been born as a pig. If we drop that assumption and if we instead assume that Elizabeth II existed before her birth and actually has some other earlier origin, then the claim that she could not have been born as a pig is no longer entailed by origin essentialism.

To illustrate, let us assume that human persons are immaterial souls. Assume that, at the first instant of the Big Bang, God created an infinite number of souls and kept them preserved. Suppose that each time a human foetus develops a brain, God places one of the souls created billions of years ago in the foetus. In this case, origin essentialism allows that we each could have been born of different biological parents than the ones we actually had. God could have taken any of the pre-existing souls that God actually put in a human foetus and God could have put it in a pig foetus instead. In that case, the person actually born human would have been born a pig. All of this is compatible with origin essentialism because the origin of the person occurred billions of years before their birth.

What origin essentialism requires is not that we originated with our parents or that we could not have had different parents. What it instead requires is that whatever something’s origins are, those origins could not have been too different. In the present example, it requires that the souls God created at the Big Bang could not have originated in a way that was too different. They couldn’t have been created five years after the Big Bang. They couldn’t have been created in Western Kansas in 1942. If God had created souls at those moments and places, God would not have created the souls God actually created but instead mere duplicates. And what the universalist should say is this: We are souls. But our souls have very specific origins. Our souls were created in a particular time and place. There is a causal history leading up to the origin of our souls. The long history of suffering on earth led to the creation of each of our souls. Change whether that history of suffering occurred, and you might get duplicates of our souls. But you won’t get our souls. And so you won’t get us. It seems to me that origin essentialism and the soul view fit comfortably together. For more on this, see Hill (Reference Hillforthcoming).

Conclusion

In this paper, I have argued that we are not missing out by starting off on earth if universalism is true. First, given the endless and infinitely valuable nature of heaven, time on earth doesn’t result in a deduction of time or goods received in heaven. It would be one thing if, for each year on earth, we got one year less in heaven along with fewer total heavenly goods. But we do not. We get the same amount of heavenly goods whether we start on earth or heaven first. Second, given origin essentialism, we couldn’t have started anywhere but earth. God might have been able to create duplicates of us that started out in heaven. But those duplicates wouldn’t be us. So if God wanted to create us, in particular, we had to begin our existence on earth with its entire causal history of suffering.