Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) is an obligate intracellular parasite with marked neurotropism, infecting up to one-third of the global population (Montoya and Liesenfeld, Reference Montoya and Liesenfeld2004). Its ability to establish chronic infections in immune-privileged sites like the central nervous system (CNS) enhances its persistence. In the CNS, the parasite switch to a low-replicative form, encysting within neurons and glial cells. Tissue cysts are impermeable to drugs and impervious to host immune responses, typically resulting in a silent, lifelong infection.

A growing body of research highlights the multifaceted impact of T. gondii infection on the nervous system, spanning molecular, cellular and behavioural alterations in both in vitro and in vivo studies. In vitro studies indicate that T. gondii affects the γ-aminobutyric acid system (MacRae et al., Reference MacRae, Sheiner, Nahid, Tonkin, Striepen and McConville2012). In animal models, T. gondii has been shown to affect the glutamate systems (David et al., Reference David, Frias, Szu, Vieira, Hubbard, Lovelace, Michael, Worth, McGovern, Ethell, Stanley, Korzus, Fiacco, Binder and Wilson2016), to induce phosphorylation of tau protein and apoptosis of hippocampal neurons (Tao et al., Reference Tao, Wang, Liu, Ji, Luo, Du, Yu, Shen and Chu2020), and to induce marked behavioural changes. In particular, T. gondii appears to specifically alter certain behavioural patterns, such as reducing the predator aversion through epigenetic modulation in the amygdala, thereby facilitating its transmission to felid hosts (Vyas et al., Reference Vyas, Kim, Giacomini, Boothroyd and Sapolsky2007; Hari Dass and Vyas, Reference Hari Dass and Vyas2014; Poirotte et al., Reference Poirotte, Kappeler, Ngoubangoye, Bourgeois, Moussodji and Charpentier2016). Therefore, motor performance, exploration of novel environments, host risk-taking tendencies or even suicidal tendencies can be altered (Vyas et al., Reference Vyas, Kim, Giacomini, Boothroyd and Sapolsky2007; Hari Dass and Vyas, Reference Hari Dass and Vyas2014; Poirotte et al., Reference Poirotte, Kappeler, Ngoubangoye, Bourgeois, Moussodji and Charpentier2016).

Interestingly, although infection in immunocompetent humans is typically asymptomatic and they are no longer part of a predator-prey trophic cycle with felids, accumulating evidence strongly associate T. gondii with neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. Specifically, T. gondii has been associated with self-directed violence in psychiatric subjects, schizophrenia, aggression and impulsivity, suicide attempts and traffic accidents, as well as Alzheimer’s disease (Torrey et al., Reference Torrey, Bartko and Yolken2012; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Brenner, Cloninger, Langenberg, Igbide, Giegling, Hartmann, Konte, Friedl, Brundin, Groer, Can, Rujescu and Postolache2015; Coccaro et al., Reference Coccaro, Lee, Groer, Can, Coussons-Read and Postolache2016; Nayeri Chegeni et al., Reference Nayeri Chegeni, Sarvi, Moosazadeh, Sharif, Aghayan, Amouei, Hosseininejad and Daryani2019; Sutterland et al., Reference Sutterland, Kuin, Kuiper, van Gool, Leboyer, Fond and de Haan2019). Furthermore, T. gondii has been found in children and older individuals with cognitive impairment (Gajewski et al., Reference Gajewski, Falkenstein, Hengstler and Golka2014; Mendy et al., Reference Mendy, Vieira, Albatineh and Gasana2015).

In people with HIV (PWH), where low cognitive performance are well-documented and known to impair quality of life (Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Clifford, Franklin, Woods, Ake, Vaida, Ellis, Letendre, Marcotte, Atkinson, Rivera-Mindt, Vigil, Taylor, Collier, Marra, Gelman, McArthur, Morgello, Simpson, McCutchan, Abramson, Gamst, Fennema-Notestine, Jernigan, Wong, Grant and Group2010; Saylor et al., Reference Saylor, Dickens, Sacktor, Haughey, Slusher, Pletnikov, Mankowski, Brown, Volsky and McArthur2016; Trunfio et al., Reference Trunfio, Vai, Montrucchio, Alcantarini, Livelli, Tettoni, Orofino, Audagnotto, Imperiale, Bonora, Di Perri and Calcagno2018), T. gondii is one of the most prevalent opportunistic infection of the CNS (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Liu, Ma, Li, Wei, Zhu and Liu2017), potentially fueling chronic immune activation, indirect neuronal damage and, possibly, neurocognitive deficits (Escobar-Guevara et al., Reference Escobar-Guevara, de Quesada-martínez, Roldán-Dávila, de Noya B and Alfonzo-Díaz2023; Diaz et al., Reference Diaz, McCutchan, Crescini, Tang, Franklin, Letendre, Heaton and Bharti2024; Manuel et al., Reference Manuel, Comia, Miambo, Sousa, Cuboia, Carimo, Massuanganhe, Buene, Banze, Paraque, Nhancupe, Schooley, Santos-Gomes, Noormahomed and Benson2025).

Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate the effect of latent T. gondii infection on neurocognitive performances and CNS pathophysiological alterations in a group of PWH without neurotoxoplasmosis.

Materials and methods

Study population

A descriptive, single-centre, cross-sectional study involving adult PWH was conducted. The enrolled subjects were admitted to the Infectious Diseases Department of Amedeo di Savoia Hospital, Turin, Italy, for neurocognitive evaluation and for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum specimens’ collection. The samples were appropriately stored at −80 °C until further use. In this cohort, both the neurocognitive assessment and the biological specimens’ retrieval were performed as part of routine clinical care for neurological symptoms. In the present study, the latent T. gondii infection was defined as the presence of anti-T. gondii IgG in the absence of overt clinical symptoms. The definition of latent T. gondii infection aligns with current literature, which, despite progress in elucidating the mechanisms of latency and developing novel latency-specific biomarkers, continues to rely on these criteria (Egorov et al., Reference Egorov, Converse, Griffin, Styles, Sams, Hudgens and Wade2021; Licon et al., Reference Licon, Giuliano, Chan, Chakladar, Eberhard, Shallberg, Chandrasekaran, Waldman, Koshy, Hunter and Lourido2023; Diaz et al., Reference Diaz, McCutchan, Crescini, Tang, Franklin, Letendre, Heaton and Bharti2024; Getzmann et al., Reference Getzmann, Golka, Bröde, Reinders, Kadhum, Hengstler, Wascher and Gajewski2024; Laguardia et al., Reference Laguardia, Carellos, Andrade, Carneiro, Januário and Vitor2024; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Toledo, Pio, Machado, Dos Santos, Hó, Medina, Cordeiro, Perucci, Pinto and Talvani2024; Montazeri et al., Reference Montazeri, Fakhar, Sedighi, Makhlough, Tabaripour, Nakhaei and Soleymani2025; Robert et al., Reference Robert, Swale, Pachano, Dépéry, Bellini, Dard, Cannella, Corrao, Belmudes, Couté, Bougdour, Pelloux, Chapey, Wallon, Brenier-Pinchart and Hakimi2025). Additionally, individuals with a confirmed diagnosis of neurotoxoplasmosis, as defined by the presence of radiological findings on Magnetic Resonance Imaging compatible with the disease, the presence of T. gondii IgG, and no evidence of alternative aetiologies (e.g. lymphoma, cryptococcoma or abscesses), were excluded from the study. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (i.e. HAND) were assessed using the previously described Frascati criteria, categorizing HAND according to the extent of impairment in everyday functioning as asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), mild neurocognitive disorder (MND) or HIV-associated dementia (HAD) (Antinori et al., Reference Antinori, Arendt, Becker, Brew, Byrd, Cherner, Clifford, Cinque, Epstein, Goodkin, Gisslen, Grant, Heaton, Joseph, Marder, Marra, McArthur, Nunn, Price, Pulliam, Robertson, Sacktor, Valcour and Wojna2007). The Medical Ethical Committee of the University of Turin approved each phase of the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Anti-T. gondii IgG antibodies

Anti-T. gondii IgG levels were evaluated with chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA) (LIAISON®, DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy) on participants’ serum samples. According to manufacturer’s instruction anti-T. gondii IgG concentrations were categorized as follows: negative (below 7.2 IU mL−1), dubious (between 7.2 and 8.8 IU mL−1) and positive (above or equal to 8.8 IU mL−1).

Assessment of neurocognitive impairments

Neurocognitive performance was evaluated through full neurocognitive testing (NCT). NCT was carried out by a trained neuropsychologist and included 12 neurocognitive tests for 6 cognitive domains: Memory (Corsi Test, Serial Repetition Disyllabic Words Test), Attention/working memory (Trail Making Test part B, Stroop Colour Test Time, Stroop Colour Interference Error), Executive functions (Frontal Assessment Battery, Verbal fluency test), Ideomotor speed (Digit symbol, Trail Making Test Part A), Visuospatial Capabilities (Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Copy) and Motor Functioning (Grooved Pegboard Test Dominant Hand, and Grooved Pegboard Test Non-Dominant Hand) (Antinori et al., Reference Antinori, Arendt, Becker, Brew, Byrd, Cherner, Clifford, Cinque, Epstein, Goodkin, Gisslen, Grant, Heaton, Joseph, Marder, Marra, McArthur, Nunn, Price, Pulliam, Robertson, Sacktor, Valcour and Wojna2007; Trunfio et al., Reference Trunfio, Vai, Montrucchio, Alcantarini, Livelli, Tettoni, Orofino, Audagnotto, Imperiale, Bonora, Di Perri and Calcagno2018). Depressive and anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A). Educational attainment, expressed as cumulative years of school attendance, was recorded as an indicator of cognitive reserve, which has recently been associated with reduced risk of cognitive impairments (Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Li, Liu, Wang and Chen2024).

Assessment of central nervous system involvement

CSF biomarkers were used for assessing neuronal-synaptic degeneration (total tau, i.e. T-tau) (Soares et al., Reference Soares, Bellaver, Ferreira, Povala, Schaffer Aguzzoli, Ferrari-Souza, Zalzale, Lussier, Rohden, Abbas, Bauer-Negrini, Teixeira Leffa, Benedet, Langhough, Betthauser, Christian, Wilson, Tudorascu, Rosa-Neto, Karikari, Zetterberg, Blennow, K, Johnson and Pascoal2025), Alzheimer’s pathology (phosphorylated tau, i.e. P-tau) (Ashton et al., Reference Ashton, Benedet, Pascoal, Karikari, Lantero-Rodriguez, Brum, Mathotaarachchi, Therriault, Savard, Chamoun, Stoops, Francois, Vanmechelen, Gauthier, Zimmer, Zetterberg, Blennow and Rosa-Neto2022), beta-amyloid deposition (amyloid-β1-42) (Theodorou et al., Reference Theodorou, Tsantzali, Stefanou, Sacco, Katsanos, Shoamanesh, Karapanayiotides, Koutroulou, Stamati, Werring, Cordonnier, Palaiodimou, Zompola, Boviatsis, Stavrinou, Frantzeskaki, Steiner, Alexandrov, Paraskevas and Tsivgoulis2025), macrophage-derived inflammation (neopterin) (Miyaue et al., Reference Miyaue, Yamanishi, Ito, Ando and Nagai2024), as well as glial activation and degeneration (S-100β) (Papuć and Rejdak, Reference Papuć and Rejdak2020). Briefly, amyloid-β1-42, T-tau and P-tau were quantified immunoenzymatically (Fujirebio diagnostics, Malvern, PA, USA); neopterin and S-100β through validated ELISA assays (DRG Diagnostics kit Marburg, Germany and DIAMETRA Srl Spello, Italy, respectively). References values were T-tau < 300 pg mL−1 (in patients aged 21–50), <450 pg mL−1 (in patients aged 51–70) or <500 pg mL−1 (in older patients); P-tau < 61 pg mL−1; amyloid-β1-42 > 500 pg mL−1; neopterin < 1.5 ng mL−1; S-100β < 380 pg mL−1.

Statistics

Eligible individuals were categorized in two groups based on the detectability of anti-T. gondii IgG, and continuous variables were compared using a Mann–Whitney U test, whereas categorical variables were compared using a Fisher’s exact. A generalized linear model was used to assess the effect of T. gondii infection on the neurocognitive impairments and CSF biomarkers of CNS pathophysiological alterations correcting for CD4 T cell counts nadir, CSF HIV viral load, potential neurotoxic ARTs, and months from HIV diagnosis. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, all statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 30.0.0, and results were graphed with GraphPad Prism 10.3.1.

Results

Study population and anti-T. gondii igG prevalence

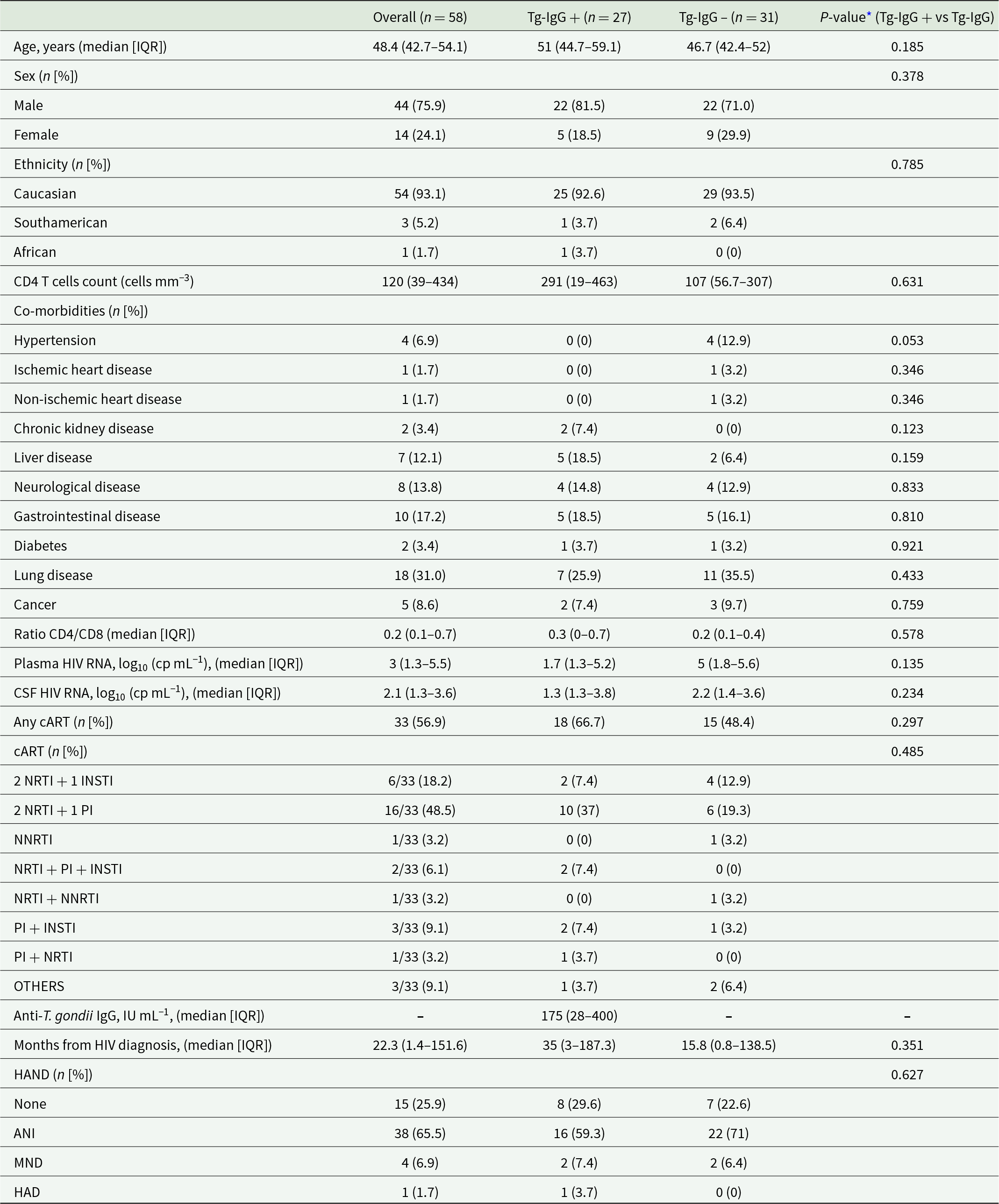

A total of 58 adult PWH were enrolled in the present study (Table 1). The median age of the cohort was 48.4 years (IQR 42.7–54.1), with the majority being male (75.9%) and of Caucasian ethnicity (93.1%). At the time of enrolment, 56.9% of participants (n = 33/58) were receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (i.e. cART). Among PWH receiving cART, the majority was receiving triple therapy NRTI + PI (48.5%) or NRTI + INSTI (18.2%). Importantly, most individuals of the cohort had a CD4 + T cell count below 500 cells mm−3, with a median of 120 cells mm−3 (IQR 39–434), and consequent low CD4/CD8 ratio (median 0.2; IQR 0.1–0.7). The median plasma HIV RNA level was 3 log₁₀ (copies mL−1) (IQR 1.3–5.5), while the median CSF HIV RNA level was 2.1 log₁₀ (copies mL−1) (IQR 1.3–3.6). The median time since HIV diagnosis was 22.3 months (IQR: 1.4–151.6), and the majority of subjects either presented an ANI (65.5%) or did not have any HAND (25.9%). None of the participants included in the study had a history of toxoplasmic encephalitis (TE)/cerebral toxoplasmosis (CTX).

Table 1. Study population

IQR, interquartile range; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; cART, combination antiretrovial therapy; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitors; PI, protease inhibitors; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; HAND, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders; ANI, HIV-associated asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment; MND, HIV-associated mild neurocognitive disorder; HAD, HIV-associated Dementia.

* Statistical analyses: Mann–Whitney U test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate; P-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Next, T. gondii co-infection was evaluated by quantifying anti-T. gondii IgG antibodies in serum samples, which revealed a prevalence of 46.5% (n = 27/58) within our cohort. Participants were subsequently stratified into two groups based on the detectability of anti-T. gondii IgG in those without any detectable IgG levels (i.e. Tg-IgG −, n = 31) and those with any detectable IgG levels (i.e. Tg-IgG+, n = 27). Among Tg-IgG + individuals, the median anti-T. gondii IgG titer was 175 IU mL−1 (28–400 IQR). The two groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, ethnicity, and comorbidities (Table 1). No statistically significant differences were observed between Tg-IgG+ and Tg-IgG− individuals with respect to CD4 + T cell counts, CD4/CD8 ratios, cART regimens, cART with neurotoxic potential, months from diagnosis, nor HAND. Similarly, HIV RNA levels in both plasma and CSF specimens did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 1).

T. Gondii and neurocognitive impairments in PWH

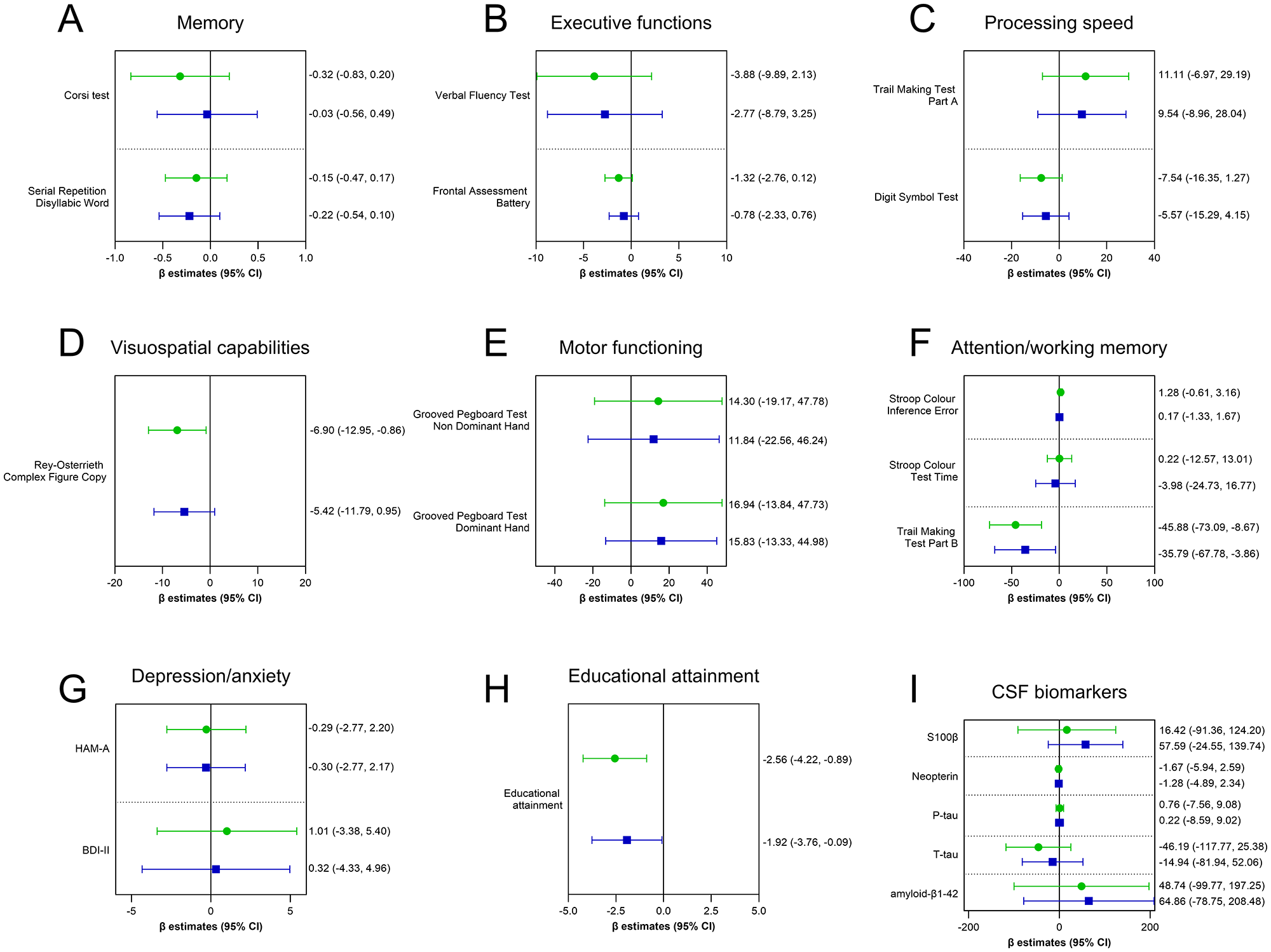

Full NCT is shown in Figure 1 (panels A–F). The most involved domain appeared to be the visuospatial capabilities as measured by the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Copy test. In the unadjusted model, T. gondii seropositivity was associated with poorer visuospatial performance (estimate: −6.90; 95% CI: −12.95 to −0.86), and, after adjusting for the relevant covariates, a comparable negative trend, though not statistically significant, persisted (estimate: −5.42; 95% CI: −11.79 to 0.95; P-value = 0.095) (Figure 1D). Within the attention/working memory domain, despite comparable performance on measures of inhibitory control and selective attention (i.e. Stroop Colour Inference Error, P-value = 0.826, and Stroop Colour Test Time, P-value = 0.707), subjects with co-infection presented a faster completion of the Trail Making Test Part B (estimate: −35.79 seconds; 95% CI: −67.78 to −3.86; P = 0.028) (Figure 1F). Second, depressive and anxiety symptoms were assessed through BDI-II and HAM-A scores; however, having the co-infection did not associate with heightened anxiety or depression (Figure 1G). Third, educational attainment was assessed as an indicator of cognitive reserve, and individuals with co-infection showed a significant lower education attainment (estimate: −1.92; 95% CI: –3.76 to −0.09); P-value = 0.040) (Figure 1H). This atypical pattern may reflect a subtle but widespread negative impact of co-infection on neurocognitive performance.

Figure 1. Effect of T. Gondii infection on neurocognitive performance and CFS markers of CNS pathophysiological alterations. Lines represent the estimated β coefficients (mean differences between IgG+ and IgG−) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), derived from the generalized linear model. The green-coloured line with circle represents the unadjusted β coefficients, whereas the blue-coloured line with square represents the adjusted β coefficients for the relevant covariates (CD4 T cell count nadir, CSF HIV viral load, potential neurotoxic ARTs, months from HIV diagnosis). Educational attainment was additionally corrected for age. P-value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

T. Gondii and CSF biomarkers of CNS pathophysiology in PWH

To investigate potential biological correlates of neuronal-synaptic degeneration, Alzheimer’s pathology, beta-amyloid deposition, macrophage-derived inflammation, as well as glial activation and degeneration associated with T. gondii seropositivity, five established CSF biomarkers were quantified: amyloid-β1-42, T-tau, P-tau, neopterin and S-100β. In this cohort, the median values of CSF amyloid-β1-42 (968 pg mL−1 [IQR: 730.5–1122]), T-tau (152 pg mL−1 [IQR: 88.3–242.9]), P-tau (35 pg mL−1 [IQR: 24.7–44]), neopterin (1.1 ng mL−1 [IQR: 0.8–3.5]) and S100β (105.1 pg mL−1 [64.2–165.5]) were all within the normal range. Indeed, reference values were as follow: i.e. T-tau < 300 pg mL−1 (in patients aged 21–50), <450 pg mL−1 (in patients aged 51–70), or <500 pg mL−1 (in older patients); P-tau < 61 pg mL−1; amyloid-β1-42 > 500 pg mL−1; neopterin < 1.5 ng mL−1; S-100β < 380 pg mL−1). Furthermore, neither in the unadjusted nor in the adjusted model was T. gondii seropositivity associated with differences in CSF biomarker levels (Figure 1I). Specifically, the group with co-infection was associated with the following estimates: amyloid-β1-42 (estimate: 64.86; 95% CI: –78.75 to 208.48; P-value = 0.376), T-tau (estimate: –14.94; 95% CI: –81.94 to 52.06; P-value = 0.662), P-tau (estimate: 0.22; 95% CI: –8.59 to 9.02; P-value = 0.961), Neopterin (estimate: –1.28; 95% CI: –4.89 to 2.34; P-value = 0.488), S-100β (estimate: 57.59; 95% CI: –24.55 to 139.74; P-value = 0.169).

These findings suggest that latent T. gondii infection is not associated with detectable alterations in the levels of CSF selected biomarkers.

Discussion

T. gondii is a neurotropic parasite with a marked affinity for the CNS. In individuals with impaired immune functions, it can cause neurotoxoplasmosis, a life-threatening condition with severe neurological manifestations. When the infection is effectively controlled, patients may remain seropositive without overt neurological symptoms. Although latent T. gondii infection has long been considered largely harmless, three decades of research now indicate otherwise, revealing a subtle but widespread impact on cognitive performance, behaviour and population-level morbidity (Latifi and Flegr, Reference Latifi and Flegr2025). This issue is particularly relevant in PWH, who not only exhibit a higher prevalence of T. gondii infection but also are at risk of cognitive impairment despite antiretroviral therapy (Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Clifford, Franklin, Woods, Ake, Vaida, Ellis, Letendre, Marcotte, Atkinson, Rivera-Mindt, Vigil, Taylor, Collier, Marra, Gelman, McArthur, Morgello, Simpson, McCutchan, Abramson, Gamst, Fennema-Notestine, Jernigan, Wong, Grant and Group2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Lu, Farrell, Lappin, Shi, Lu and Bao2020). However, data addressing the impact of latent T. gondii infection on neurocognitive outcomes in PWH remain limited. Therefore, in an attempt to address this knowledge gap, this study aimed to investigate the impact of latent T. gondii infection on neurocognitive performance and CSF biomarkers of CNS pathophysiology in PWH with low CD4 T cell counts without neurotoxoplasmosis.

Interestingly, the global seroprevalence of T. gondii is estimated at 31% (95% CI: 28–34), with substantial heterogeneity across regions (e.g. 42% in Africa and 25% in Asia) (Sengupta et al., Reference Sengupta, Jacob, Suresh, Rajamani and Maharana2025). Prevalence rates are higher among immunocompromised subjects, with a recent pooled estimate of 42% (95% CI: 34–49) (Rahmanian et al., Reference Rahmanian, Rahmanian, Jahromi and Bokaie2020). In the context of HIV infection, the global prevalence of T. gondii co-infection in PWH has been estimated at 35.8% (95%: 30.8–40.7), with the highest rates observed in sub-Saharan Africa and low-income countries (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Liu, Ma, Li, Wei, Zhu and Liu2017). Consistently, our findings revealed a seroprevalence of T. gondii infection of 46.5% among PWH with low CD4 T cell counts, aligning with previous reports associating immunosuppression as well as HIV infection with higher T. gondii prevalence.

Furthermore, although the prevalence of HAND has decreased with cART (Mastrorosa et al., Reference Mastrorosa, Pinnetti, Brita, Mondi, Lorenzini, Del Duca, Vergori, Mazzotta, Gagliardini, Camici, De Zottis, Fusto, Plazzi, Grilli, Bellagamba, Cicalini and Antinori2023), neurocognitive impairment remains common, with an estimated overall prevalence of 42.6% (ANI 23.5%, MND 13.3%, HAD 5%) (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Lu, Farrell, Lappin, Shi, Lu and Bao2020). However, the potential impact of HAND on our study measures may be considered negligible. Indeed, on one hand, the majority of individuals fell within the spectrum of either no HAND or ANI. On the other hand, emerging evidence indicates that conventional neurocognitive assessments may overestimate disease burden, suggesting that the high reported prevalence of HAND may not fully reflect clinically meaningful impairment (Nightingale et al., Reference Nightingale, Ances, Cinque, Dravid, Dreyer, Gisslén, Joska, Kwasa, Meyer, Mpongo, Nakasujja, Pebody, Pozniak, Price, Sandford, Saylor, Thomas, Underwood, Vera and Winston2023): while TE may be crucial for legacy symptoms, the role of T. gondii infection in active HIV-associated brain injury is unknown. Accurate diagnosis in PWH therefore requires simultaneous consideration of cognitive symptoms, low performance on cognitive tests, and abnormalities on neurological investigations (Nightingale et al., Reference Nightingale, Ances, Cinque, Dravid, Dreyer, Gisslén, Joska, Kwasa, Meyer, Mpongo, Nakasujja, Pebody, Pozniak, Price, Sandford, Saylor, Thomas, Underwood, Vera and Winston2023), and we did not detect CSF biomarkers alterations.

In our cohort, T. gondii infection did not appear to strikingly affect the neurocognitive performance, except for a faster completion of the Trail Making Test Part B and a reduced educational attainment. Importantly, a faster performance on the Trail Making Test Part B, which occurred in the absence of better outcomes in the Stroop Colour tests, should be interpreted with caution, and argue against a generalized improvement in executive control. Indeed, the complex and multifactorial mechanisms underlying the performance on this test have already been shown (Chan et al., Reference Chan, MacPherson, Robinson, Turner, Lecce, Shallice and Cipolotti2015; Varjacic et al., Reference Varjacic, Mantini, Demeyere and Gillebert2018; Recker et al., Reference Recker, Foerster, Schneider and Poth2022). Furthermore, T. gondii has been associated self-directed violence in psychiatric populations, including schizophrenia, aggression and impulsivity, suicide attempts and traffic accidents (Torrey et al., Reference Torrey, Bartko and Yolken2012; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Brenner, Cloninger, Langenberg, Igbide, Giegling, Hartmann, Konte, Friedl, Brundin, Groer, Can, Rujescu and Postolache2015; Coccaro et al., Reference Coccaro, Lee, Groer, Can, Coussons-Read and Postolache2016; Sutterland et al., Reference Sutterland, Kuin, Kuiper, van Gool, Leboyer, Fond and de Haan2019). Therefore, our findings may reflect differences in response strategies, impulsivity or altered risk-taking behaviour rather than cognitive benefits. The trends observed across the other cognitive domains are consistent with subtle, non-significant but widespread decline in cognitive performance, as observed in the visuospatial performance. The lack of significant alterations in CSF biomarkers of neuronal-synaptic degeneration, Alzheimer’s pathology, beta-amyloid deposition, macrophage-derived inflammation or glial activation and degeneration align with these cognitive findings. Moreover, these biological data are further supported by previous in vitro and in vivo studies, which have shown more subtle biological mechanisms associated with T. gondii infection, such as modulation of the γ-aminobutyric acid and glutamate systems, or epigenetic changes in the amygdala (MacRae et al., Reference MacRae, Sheiner, Nahid, Tonkin, Striepen and McConville2012; Hari Dass and Vyas, Reference Hari Dass and Vyas2014; David et al., Reference David, Frias, Szu, Vieira, Hubbard, Lovelace, Michael, Worth, McGovern, Ethell, Stanley, Korzus, Fiacco, Binder and Wilson2016). Therefore, the faster completion of the Trail Making Test Part B and the reduced educational attainment appear to occur in the absence of detectable CNS pathophysiological alterations.

The atypical pattern of T. gondii–host interaction observed in our cohort is not surprising. Indeed, whereas T. gondii infection is often associated with adverse cognitive outcomes, emerging evidence suggests that under specific conditions it may exert neuroprotective or compensatory effects on the brain. For example, in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia, chronic T. gondii infection was linked to reduced brain damage and improved neurobehavioral performance, potentially through the upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), both of which may enhance cerebral resilience (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Jung, Song, Seo, Chai and Oh2020). Therefore, the mechanisms underlying T. gondii–human interaction may be more complex than initially thought. Additionally, recent findings have shown that PWH with latent toxoplasmic infection, as defined by the presence of anti-T. gondii IgG, do not exhibit different cognitive performance as compared to PWH without latent toxoplasmic infection, as defined by the absence of anti-T. gondii IgG (Diaz et al., Reference Diaz, McCutchan, Crescini, Tang, Franklin, Letendre, Heaton and Bharti2024). Notably, cognitive impairment was significantly worse among PWH diagnosed with toxoplasmic encephalitis. Our study confirms and extends these observations in a more heterogeneous cohort. While we did not find statistically significant associations between T. gondii infection and cognitive impairment, the observed trajectories suggest a subtle but widespread trend towards poorer performance across most cognitive domains. These patterns may be linked to the significantly lower educational attainment observed in this group. Indeed, previous research has identified education as a key predictor of cognitive impairment (Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Li, Liu, Wang and Chen2024). Furthermore, longitudinal data show that cognitive performance in PWH, regardless of whether they had latent T. gondii infection or encephalitis, remained stable over a 7-year follow-up, despite the highest prevalence of cognitive impairments in the domains of verbal, executive function, learning, recall, working memory, processing speed and motor functions in those with encephalitis (Diaz et al., Reference Diaz, McCutchan, Crescini, Tang, Franklin, Letendre, Heaton and Bharti2024). However, despite our results align with the literature showing subtle but widespread effects of latent T. gondii infection on cognitive performance and behaviour (Latifi and Flegr, Reference Latifi and Flegr2025), the present study cannot exclude the occurrence of increased cognitive impairments over a longer follow-up.

Several limitations must be acknowledged when interpreting the results of this study. First, the relatively small sample size as well as the heterogeneity of the study population may have limited the statistical power. These constraints are especially relevant in the context of complex cognitive phenotypes, which are influenced by numerous biological, clinical and environmental factors. Moreover, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes any causal inferences about the directionality or temporality of the observed associations. Longitudinal data would be needed to determine whether T. gondii seropositivity predicts cognitive decline or modulates neurodegenerative progression over time. Furthermore, the mechanisms underlying the absence of overt clinical symptoms in our cohort cannot be determined; e.g. this could reflect T. gondii infection before HIV acquisition or the effect of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis. Lastly, the findings of the present study should be interpreted within the context of a predominantly male PWH population with low CD4 T cell counts, but future studies will be valuable to clarify potential sex-specific differences (Latifi and Flegr, Reference Latifi and Flegr2025), as well as the impact of higher CD4 T cell counts.

In summary, these initial findings in PWH with low CD4 counts and a likely T. gondii latent infection, suggest that they do not exhibit markedly worse cognitive performance, although subtle declines are suggested across domains. These individuals show lower educational attainment and a faster completion of the Trail Making Test Part B without evidence of detectable CNS pathophysiological alterations. These findings highlight the complex, context-dependent effects of T. gondii on the brain. Given the study’s limitations, particularly the sample size and cross-sectional design, caution is warranted. Nonetheless, the results call for further research into how chronic infections interact with cognition in vulnerable populations. In this context, there is a growing effort to identify circulating plasma biomarkers that could facilitate large-scale studies and enable less invasive monitoring of CNS pathophysiological alterations (Prins et al., Reference Prins, de Kam, Teunissen and Groeneveld2022; Vrillon et al., Reference Vrillon, Bousiges, Götze, Demuynck, Muller, Ravier, Schorr, Philippi, Hourregue, Cognat, Dumurgier, Lilamand, Cretin, Blanc and Paquet2024), as well as to better define latent T. gondii infection (Egorov et al., Reference Egorov, Converse, Griffin, Styles, Sams, Hudgens and Wade2021; Licon et al., Reference Licon, Giuliano, Chan, Chakladar, Eberhard, Shallberg, Chandrasekaran, Waldman, Koshy, Hunter and Lourido2023; Robert et al., Reference Robert, Swale, Pachano, Dépéry, Bellini, Dard, Cannella, Corrao, Belmudes, Couté, Bougdour, Pelloux, Chapey, Wallon, Brenier-Pinchart and Hakimi2025). Longitudinal, mechanistic studies with larger cohorts are needed to clarify whether T. gondii contributes to cognitive outcomes in HIV, and under what conditions such effects may be harmful, neutral, or adaptive.

Acknowledgements

We thank the clinical and laboratory staff of the Infectious Diseases Department, Amedeo di Savoia Hospital, Turin, Italy, for their support in patient management and specimen collection. We are also grateful to all study participants for their contribution.

Author contribution

D.R. conceived the study, collected and analysed data, and drafted the manuscript. S.Z. contributed to study design and data interpretation. M.T. and A.C. provided clinical data, patient recruitment, and critical manuscript review. E.F. supervised the project and contributed to study design. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Financial support

The work was financed through the grant UNITO funds RILO 2020-2021 Zanet-Ferroglio, University of Turin.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the University of Turin, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment.

Artificial intelligence

ChatGPT5 was used to proofread the main text.