Using Birmingham as a case-study, this article explores the extent and impact of urban ‘dry’ conservancy systems on public health in England between the 1870s and 1920s.Footnote 1 It examines the local council’s adoption and management of pail privies (or closets), known colloquially as the ‘pan system’, which operated between 1873 and 1915 and was intended as a replacement for the existing ashpit (or midden) conservancy system. Although water carriage systems that used water to flush through sewers were expanding by 1870, ashpit conservancy was the main form of waste management for households in Birmingham and human excreta from privies drained into many of them. The ashpits were often located right next to buildings and were left exposed for long periods with infrequent emptying. The pail system was another form of dry conservancy but involved a removable receptacle under a wooden seat, typically collected once a week and exchanged for a clean pail.Footnote 2 As these systems were often ‘class specific’, this article looks to the inhabitants of Birmingham’s back-to-back houses to assess the impact of conservancy and leads to a deeper understanding of living with pail and ashpit privies.Footnote 3 It argues that the extent and longevity of dry conservancy systems should be given greater attention due to their impact on health and disease, through human and insect pathways of transmission. It draws out the importance of looking at the problem of flies, something which was largely ignored until the twentieth century. This examination of waste management in Birmingham advances knowledge on the practice and impact of conservancy and offers local context to understand the reasons for their systemized development. Also, why the systems endured despite considerable municipal investment in sanitation, typically defined as water supply, sewerage and sewage treatment. This investment in the late nineteenth century fuelled a sanitary revolution, yet conservancy systems were relied upon well into the next century. As conservancy also saw considerable investment, particularly in new technology for the disposal of human excreta and the burning of refuse, a case is made for a wider perspective when exploring sanitation. It also challenges existing ideas in the debates surrounding investment in sanitation infrastructure and mortality decline and considers the implications for future research.

Tom Crook points out that by the 1890s, dry conservancy systems were in use in 30 urban centres, and that for 15 of those centres with a population of 2.6 million, there were 230,000 pail closets in use.Footnote 4 Ashpits remained in use despite their universal condemnation by medical practitioners and social reformers. For instance, in Gateshead, ashpits continued to be installed at the end of the century and as many as 18,000 were still in use in 1913.Footnote 5 Crucially, Crook identifies that pail systems were often implemented as solutions to the nineteenth-century’s ‘sewage question’ but then often became contested themselves.Footnote 6 Alan Wilson’s detailed look at the development of Manchester’s municipal wet and dry sanitary systems concludes that pail systems were the ‘next logical step in improving urban conservancy sanitation’, as they established the principles of regular waste removal. He argues that the choice of sanitary system by local authorities ‘had a profound influence’ on the environment and urban communities.Footnote 7 Similarly, Geoff Timmins, in his assessment of the efforts to improve ‘domestic sanitation’ in the county of Lancashire, highlights the importance of housing design to facilitate collection practices for conservancy. He suggests that with single family use pail systems were workable.Footnote 8 John Wilson and Denise Amos, in separate studies, have both examined the use of pail privies in Nottingham and Wilson suggests that up to World War I most houses in Nottingham used this type of closet.Footnote 9 When looking more closely at the relationship of pail privies and water closets to warm weather and infant mortality rates (IMRs), Wilson found evidence for improved public health with water closets (WCs).Footnote 10 This article adds to the scant historiography examining conservancy systems in localities, but goes further by illuminating more closely the practice of municipal waste management.

Conservancy formed part of the urban environment with thousands of outdoor privies and exposed ashpits. The pail systems added to the ‘urban metabolism’ through the regular collection of waste by horse-drawn vehicles and central processing plants.Footnote 11 As Sabine Barles reconstructed for a metabolic history of Paris, the ‘material flows’ within a city which result in outflows of waste as ‘exports’, or ‘flows to nature’, were multi-species.Footnote 12 This article highlights the public health consequences of these multi-species outflows in Victorian cities when flies were ‘ubiquitous’.Footnote 13 The presence of working horses for carriage and transport produced huge amounts of manure; the favoured breeding site for flies.Footnote 14 Nigel Morgan argues that horse populations in towns ‘was probably responsible for sustaining, or even enhancing, levels of infant mortality due to enteric diseases spread by flies’.Footnote 15 Linda Davies also emphasizes the importance of flies in relation to diarrhoea and enteritis and IMRs in a local study of Hemsworth in Yorkshire. Yet, Davies’ findings did not fully support Morgan’s claim that this was attributable to the increase in the number of horses.Footnote 16 Whereas Christopher French and Juliet Warren’s analysis of infant mortality in Canbury concluded that ‘the proximity of animals to living space’ was a significant factor due to the manure produced.Footnote 17 As peak fly breeding is in the warmer summer months, climate plays its part, and feeds into identified patterns in mortality rates.Footnote 18 However, horse manure was not the only attractive prospect for flies in the urban landscape with slaughter houses, poor sanitation and a lack of proper waste management equally important attractions.Footnote 19 Dawn Biehler stresses how important ‘environmental sanitation’ was to eliminate ‘fly-breeding landscapes’, and this article highlights the interdisciplinary potential of animal history as a branch of environmental history.Footnote 20 Crucially in terms of conservancy, I.H. Buchanan identified that methods of privy waste disposal were a significant factor for the impact of the house-fly as flies spread filth to food.Footnote 21 This study offers further evidence for this vector of transmission relationship through the lived experience of the inhabitants of Birmingham’s back to backs. It goes further to make the point that as this transmission relationship was not widely understood by medical practitioners in England until the second decade of the twentieth century, it is not found in contemporary sources. Consequently, this relationship continues to be underappreciated in later analyses of those sources.

Urban conservancy systems continued to operate alongside significant investment in local sanitation infrastructure or major civil engineering projects in the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 22 When examining this investment, the focus is often on water supply, sewerage and sewage treatment and can exclude expenditure for conservancy and waste management. Birmingham council invested in all these areas but certainly its most significant investment was in water supply, with the municipalization of the city’s private waterworks in 1875 followed by the 1892 Elan Valley Water Scheme. This ambitious scheme involved the construction of dams and reservoirs in gathering grounds in Wales with a 73-mile aqueduct to transport water to the city.Footnote 23 A local act of parliament gave the authority to borrow and construction began in 1893, taking 11 years for the completion of the first phase. Local authority access to favourable financial terms was crucial and Matthew Gandy has highlighted how important municipal bonds were to enable these large-scale projects.Footnote 24 Prior to the arrival of this supply in 1904, the council relied on local sources and had significantly expanded the supply across the city. However, it faced a continual battle to meet the growing demand for water and protect its sources from pollution.Footnote 25 There was also considerable investment in the development of sewage treatment infrastructure through a joint drainage board largely controlled by Birmingham council.Footnote 26 Yet, throughout this period, Birmingham’s mortality rates and infant mortality remained stubbornly high.Footnote 27 This therefore can contribute to existing debates on whether investment in sanitation in the last part of the nineteenth and early part of twentieth centuries had any major impact on mortality trends.Footnote 28 Similarly, it throws light on the efforts to measure the contribution of loan financed public works.Footnote 29 The original suggestion made in the 1970s by Thomas McKeown was that the contribution of ‘municipal sanitation’ was less than a quarter at best, but this was refuted by Simon Szreter, who, by correlating decline in deaths with government loans, suggested that sanitation was the primary factor.Footnote 30 More recently, Jonathan Chapman suggests that investment in sanitation infrastructure accounted for 60 per cent of urban mortality decline between 1861 and 1900.Footnote 31 With other recent studies, such as those by Bernard Harris and Andrew Hinde and Toke S. Aidt et al., not coming to firm conclusions, the debate persists.Footnote 32 This article presents evidence from Birmingham, which suggests that England’s second city did not see a significant decline in mortality before 1905 and considers the implications for these debates.

As greater responsibility was placed on local government for improving sanitation through the Public Health Acts of the 1870s, local records are important sources. Birmingham has extensive local government records that chart this development, plus numerous local specific sources produced by council individuals and employees involved in the development of municipal systems.Footnote 33 For example, Birmingham’s sewage enquiry in 1871 produced a 300-page report which offers valuable detail on waste management systems in operation in Liverpool, Manchester, Rochdale, Leeds, Nottingham and Hull.Footnote 34 Medical officer of health (MOH) annual reports are also rich sources as environmental sanitation formed a major part of their remit, with MOHs often recording the type and number of conveniences in areas of concern.Footnote 35 Local newspapers help complete the picture by revealing any problems or challenges that local government records may deliberately omit or downplay.

This article firstly looks broadly at conservancy in England and the development of systemized operations, before focusing on the practice of municipal waste management in Birmingham. Secondly, it analyses the investment made by Birmingham council for improving sanitation infrastructure and examines the city’s mortality rates for the period. It then turns to the impact of conservancy through the experience of the inhabitants of Birmingham’s back to backs, the primary users of ashpit and pail privies. Finally, it draws conclusions and considers the implications on existing debates and future research.

Urban conservancy systems

Alan Wilson suggests that conservancy systems were a necessity, particularly in areas where water supply or river pollution was an issue.Footnote 36 In terms of supply, just as fresh water is ‘spread unevenly’ around the globe, so too are there ‘regional imbalances’ in England and Wales, which influenced choices for sanitary provision.Footnote 37 Both issues were integral to Birmingham’s experience, but river pollution was the initial motivating factor for change. Like Manchester, Birmingham council adopted a pail system as a substitute for the existing ashpits in an attempt to ‘intercept’ excreta and prevent waste entering the sewers and polluting rivers and tributaries.Footnote 38 It was motivated to do this because it was subject to injunctions during a long legal battle over its sewage nuisance of the river Tame.Footnote 39 Circumstances came to a crisis point in 1870–71 and brought the sewage question for Birmingham into sharp focus.Footnote 40 The response was an internal enquiry with a remit to recommend solutions to deal with Birmingham’s growing volume of human waste while at the same time allay the legal injunctions against the council. As part of the enquiry, the committee investigated all available methods (both wet and dry) and looked to systems already in operation in other provincial towns.Footnote 41

Liverpool had chosen to pursue water carriage, and for the poorest classes was using troughs with intermittent flushing controlled by the council. In contrast, Manchester council had decided to replace middens with a new type of pail privy (at the cost of the owners) designed with a meshed chute to allow the adding of sifted fine ash to soak and deodorize. Whereas the authorities in Rochdale had introduced another version of a pail system using two separate receptacles, one for ashes and another for excreta.Footnote 42 At the time, pail systems were seen as an improvement on ashpits on the basis that the system facilitated regular waste removal. This was because ashpits were notoriously left exposed and unemptied for long periods of time and this was a complaint raised during Birmingham’s enquiry and beyond.Footnote 43 Due to the city’s river pollution, the expansion of water carriage was immediately discounted; the last thing Birmingham council wanted to do was encourage more WCs exacerbating the problem. A pail system was the obvious choice, and the committee concluded that the methods used in Manchester and Rochdale might work best for Birmingham. From the council’s perspective, a new form of conservancy would not only reduce river pollution but it could also address public health through the substitution of all ashpits and introduce regular waste collection. The final decision was to follow the Rochdale method with the separation of waste, a choice based upon that town’s experience of operating 1,250 pails at the time. There was also a local influence as Birmingham Workhouse was also trialling a pail system and offered a positive report to the enquiry.Footnote 44 After initial delays, the roll out of Birmingham’s new method began in late 1873, by which time Manchester had 696 of its new privies in operation.Footnote 45

By 1876, more towns adopted the pail system and a Local Government Board survey reported that Birmingham with its 83,500 houses had 8,000 WCs, 35,000 ashpit and 7,000 pail privies. In the northern towns of Bolton and Blackburn, there were 700 and 2,690 pail privies respectively, despite Blackburn having fewer houses than Bolton. In contrast, the elite spa town of Cheltenham, with 8,725 houses, used water carriage completely with 8,500 WCs and no privies.Footnote 46 By 1885, Birmingham’s new system had expanded with more than 36,900 pails in service. In contrast, there were over 66,000 pails in service in Manchester by 1888.Footnote 47 Nottingham had also adopted a pail system from 1868 and by 1910 had ‘36,015 pail closets…of which 6, 172 served two or more households’.Footnote 48 Although similar in operational size to Birmingham, there were differences in practice, as Nottingham had persevered with wooden pails and only changed to galvanized steel buckets in 1904. Whereas Birmingham from the start used galvanized iron ‘pans’ that were larger than the pails used in Rochdale.Footnote 49

Eventually, this new method of conservancy became just as contested as ashpits, but it endured.Footnote 50 Nottingham council passed a resolution in July 1895 that the pail privy should ‘no longer be recognised and that water carriage was the way forward’. Despite this resolution, pail privies remained the ‘mainstay’ until 1919.Footnote 51 There was a similar situation in Birmingham and Manchester where council decisions to phase out the pail did not translate into a fully funded programme of conversion to WCs. Contrast this with Leicester, where pails began to be replaced with WCs in 1896, with the scheme virtually completed by 1903.Footnote 52 World War I hampered many a conversion programme but ratepayer resistance to the expense being placed upon them and a lack of local authority funds to facilitate speedier conversion were also factors. So too were continual issues over inadequate water supply and river pollution. Birmingham cited all these reasons to explain why its system endured until 1915. For other towns and cities, World War I saw much conversion work cease. Post-war conversion took place at a greater pace but in 1920 Manchester still had over 1,300 pail and 48 ashpit privies and Nottingham had 660 pails remaining in 1923.Footnote 53

Birmingham’s adoption of a pail system lasted for four decades. The underlying principles of any pail system was the regular collection and efficient disposal of waste. This required labour and transport, as well as processes to deal with large volumes of waste, as Birmingham’s system in practice reveals.

Birmingham’s municipal waste management system

Between 1853 and 1873, Birmingham council’s waste management consisted of a single Nightsoil section responsible for emptying the city’s ashpits. However, the sewage enquiry in 1871 had exposed the infrequent emptying and poor state of the city’s ashpits.Footnote 54 With the introduction of the new pail system, municipal waste management expanded to include an ‘Interception’ section to operate alongside Nightsoil.Footnote 55 The key difference was ‘efficient and regular’ collection, with full pails collected once a week and replaced with disinfected ones; the dirty pails were taken to three of the council’s canal side wharves within the city centre for processing.Footnote 56 Initially small scale, the new section comprised ten men, five horses, three vans and two dust carts attempting weekly collections of 1,700 pails. It was soon apparent that requirements had been underestimated, and additional workers and transport were needed. Over the next decade, the system expanded considerably, reaching its peak of over 38,000 pails in service, including at Board schools and some manufactories. By 1883, the Interception section alone employed over 220 men with a transport stock of 57 vans, 60 ash carts and 124 horses in service.Footnote 57

In the early years, the disposal method of pail contents was like that of ashpits, with the mixing of ashes and waste to create a type of manure that would be available at a cheap price to farmers. Any surplus was transported by canal or cart to tips located outside of the centre. When increased volumes made this unsustainable and expensive the council looked to new technology specifically designed to deal with the excreta collected in pails. By 1877, the council was using industrial drying machines to produce a fertilizer product in the hope that ‘poudrette’ would rival guano sales and generate a source of income.Footnote 58 By the end of the century, the Interception section was disposing of pail contents, ashes, animal matter from abattoirs, vegetable refuse from the markets and street sweepings.Footnote 59 Poudrette and concentrated fish manure (made from trade waste fish offal) did find a market for a time, necessitating the need for a salesperson, but it only ever succeeded in generating a modest annual income. Nevertheless, the manufacture of poudrette continued until 1910, contrary to the suggestion that ‘urban chemistry’ and the circulatory conception of the nitrogen cycle faded from the 1860s.Footnote 60 As the system involved the collection of two receptacles, the collection of ashes and other domestic refuse motivated the investment in destructors to burn waste and therefore reduce the volume being sent to local tips. Birmingham had very quickly followed Manchester’s lead by installing an Alfred Fryer destructor in 1876 at its Shadwell Street wharf and depot.Footnote 61

Although similar in practice, the Birmingham pail system never matched the scale of Manchester’s operation. The original aim had been to ‘abolish’ ashpits, but this never happened. At best, there was a 60 per cent reduction in number by 1885, as another council survey revealed there were still around 13,000 ashpits, despite the new system having been in operation for over a decade.Footnote 62 Given that there was no incentive scheme to help with the costs of converting privies, the council faced resistance from landlords. When challenged legally, local magistrates ruled that despite being an Urban Sanitary Authority, the council could not enforce the adoption of pails over the ashpit if property owners attended to them properly.Footnote 63 This forced the council to instead focus on new buildings, stipulating the adoption of the municipal pail, through the power of its own by-laws for new buildings of a certain class. There were other challenges as the system soon proved extremely unpopular with the city’s residents due to the noisy collections at night with the smelly vans travelling back and forth to the wharves multiple times. Letters to local newspapers complained about the ‘demons of the night’.Footnote 64 The council faced a dilemma; it was in no position to opt for a swift transition to full water carriage due to the legal difficulties over river pollution (which continued until 1895) and the struggle to meet the growing demand for water from local sources. However, in 1887 the council made a discreet policy change, halting any additions to the pail system and directing that any new building should have WCs rather than pails.Footnote 65

Another reason the system was not extended further was that it was clear from an early stage that the design of back-to-back housing with a narrow entrance to a central communal courtyard was not suitable for this type of conservancy. There was little space for additional privies with more desperately needed as there were some reports of 60 people sharing six pails in a single courtyard.Footnote 66 Illustrating Timmins’ point on housing design, back to backs with no access to the courtyards for the horse-drawn vans meant intensive lifting and carrying of heavy pails. This led to bad practices by employees, which were eventually exposed as a scandal in the pages of the Birmingham Daily Post in 1890. The insanitary nature of pails was compounded by being moved at night in little light with the contents split around the courtyards and alleyways. Many pails ended up not being returned for disinfecting and no one was responsible for cleaning these areas before the late 1890s.Footnote 67 Yet, despite the problems, those already part of the municipal pail system before 1887 had to endure the system for at least a further 15 years before any significant conversion began.

It was only after the arrival of the new water supply from Wales that the council felt it could confidently declare a policy of abolition for the pail. After the 1911 boundary extension and council reorganization, there was a more concerted effort for conversion to WCs, although still completely chargeable to the property owners. The Interception and Nightsoil sections became part of the Lighting, Refuse and Stables Department eventually becoming the Salvage Department with a sole focus on refuse.Footnote 68

Birmingham’s pail system had considerable running costs due to staff and horses as well as capital investment in vehicles, infrastructure and new technology to deal with the volumes of waste. It was implemented as part of the answer to the sewage question and the city’s sanitation needs. Hence, the capital expenditure for conservancy should be considered when looking at what local authorities invested, yet it is often ignored when the typical focus of sanitation is water supply and water carriage systems.

Birmingham’s sanitation infrastructure investment from the 1870s to 1915 and mortality decline

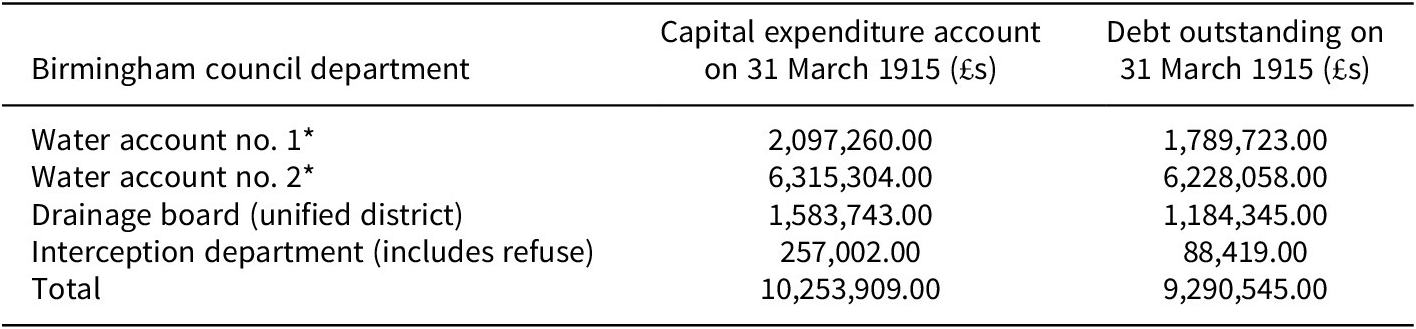

Over this period, Birmingham made considerable investment in its sanitation infrastructure by transitioning from wells to a piped water supply; implementing a new method of conservancy; and the development of a sewage works through a joint drainage board. Table 1 offers the capital expenditure accounts for these three main areas of investment in Birmingham. The Birmingham and District Tame and Rea Drainage Board was a separate entity to the council as it included the surrounding self-governing districts. However, Birmingham was the primary contributor and the major producer of waste. After the boundary extension of the Greater Birmingham Act of 1911, most of those surrounding districts came under the authority of Birmingham council.Footnote 69

Table 1. Birmingham’s capital expenditure accounts and debts outstanding for sanitation as at 1915

Note: * There were two capital accounts for water with no. 1 account relating to the 1875 and 1879 acts and no. 2 account relating to the 1892 Act for the Elan Valley Scheme.

Sources: This table was compiled using figures from Bunce, History of the Corporation II, and Vince, History of the Corporation IV, 99, 440–5, 450.

Added to this should be some of the capital expenditure of the Public Works Department, which was responsible for sewerage. That department’s total capital expenditure by March 1915 was £3,256,377.Footnote 70 It is difficult to offer a complete breakdown of the exact costs of sewerage, but between 1900 and 1915 there were several individual loans on terms of 30 years, totalling just over £288,000.Footnote 71 This suggests in the region of £11 million was invested in sanitation.

Some examples of this capital expenditure in Birmingham include £25,000 by the Interception Department in 1879 on machinery, plant and stabling at the Montague Street works. There was further expenditure of £27,000 in 1882 in the additional drying machines to process the contents from the pails.Footnote 72 For waste delivered by sewerage, there was major investment extending the drainage board’s sewage farm operation at a cost of £500,000 in 1896. This was quickly followed by an additional £400,000 by 1912 as the drainage board embraced the new scientific advancement in the treatment of sewage and constructed bacteria beds at the Saltley and Minworth works.Footnote 73 The greatest capital expenditure was for the Elan Valley Water Scheme (water account no. 2) with powers granted through a local act to borrow £6.6 million for a scheme to be delivered in two phases.Footnote 74 However, simple statistics on how much was borrowed cannot reveal the whole story. The 1892 water scheme, based on an original estimate at just over £3.4 million for the first phase, went over budget with total costs of just over £5.8 million, meaning the money intended for the second part of the scheme was spent. The council’s promises to ratepayers of no additional burden on the rates and to customers of reduced water charges by a certain date never materialized. To meet the shortfall in capital expenditure for the next phase of the Elan Valley project, customer water rates were increased by a significant amount in 1915, rising from 6 per cent of rateable value to 10 per cent. The council partly justified this rise by pointing out that consumption had significantly increased due to the widespread conversion to WCs and more internal bathrooms.Footnote 75

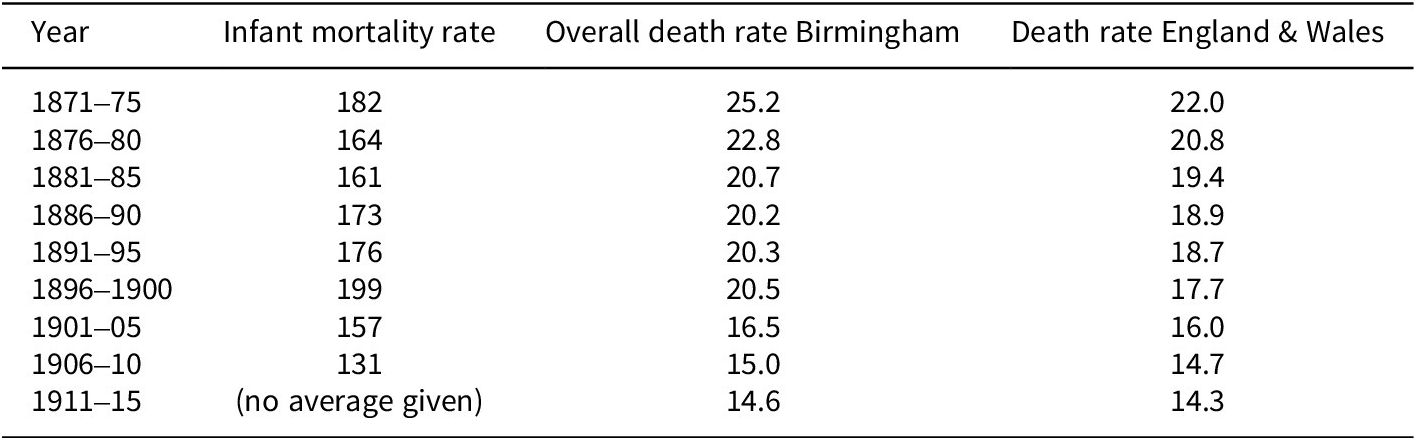

Yet, despite this considerable investment in sanitation during this period, for Birmingham’s poorest classes conservancy remained the reality. With specific local context how did this all translate in terms of public health? Is there evidence that any of this investment led to a significant reduction in mortality rates in Birmingham? Table 2 suggests there was no significant decline in overall death rates in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. This was not seen until the early twentieth century, with rates between 1906 and 1910 averaging at 15.0, which corresponds to the arrival of the new water supply after 11 years of construction. However, overall death rates can be misleading as rates in individual districts (wards) could be much higher. Birmingham’s three most densely populated wards were St Stephen’s, St Mary’s and St Bartholomew’s and were labelled as ‘unhealthy areas’. They saw higher death rates of between 24.6 and 26.6 between 1897 and 1902. By 1907, rates for St Mary’s and St Bartholomew’s had declined only slightly to 21.4 and 23.6 respectively, and by 1912 the rate for St Bartholomew’s reduced to 20.2 but St Mary’s saw a rise to 26.0.Footnote 76 At this stage, the majority of citizens had access to the new supply of fresh water from Wales and the council was no longer operating a policy of discouraging WCs, but still those in the poorest housing were living alongside pail and ashpit privies. The overspend on the Elan Valley Scheme meant the council was in no financial position to facilitate a swifter transition or tackle the desperate need for new housing in the city. As Robert Millward and Frances Bell identified, data on loans cannot indicate when such investment actually impacted on health.Footnote 77 The benefits of the investment in infrastructure for water supply and sewage treatment, which facilitated conversion to WCs and internal bathrooms, was not felt equally by all citizens. Those in the poorest housing with conservancy continued to experience its impact and less positive health outcomes.

Table 2. Recorded death rates taken from Birmingham medical officer of health reports for 1914 and 1921

The impact of conservancy

Conservancy was obviously dirty, smelly and unhygienic with faecal matter left exposed until collection, and non-existent means to keep areas clean and hygienic. Large-scale sharing of privy facilities with no hand washing inevitably meant increased opportunity for the transmission of disease. Hygiene issues were compounded by the poor collection practices by council employees leaving the privies and courtyards soiled. From a public health perspective, local MOHs may not have had full epidemiological understanding in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, but connections were definitely made.Footnote 78 Birmingham’s MOH, Dr Alfred Hill, frustratedly reported in 1897 that the death rate for the city had remained stubbornly the same for 15 years.Footnote 79 Covering a period that coincides with the peak years of operation for the pail system, the rate was stuck at 20 per 1,000 of the population. In the ‘unhealthy areas’ with the highest concentration of pail and ashpit privies, the ratio of people to privies was between 6:1 and 10:1.Footnote 80 Not surprisingly, when Birmingham suffered a severe diarrhoea epidemic in 1897, Hill reported that the highest number of deaths were in these areas. Again, in his 1899 report he demonstrated the correlation, using a graph, showing how the highest death rates were in districts with the lowest percentage of WCs.Footnote 81

MOHs and local administrations made some key interventions that reduced mortality but could be restricted by a lack of political will and financial resources. Hill was well informed on new medical developments, active within a network of societies for MOHs and public analysts.Footnote 82 Yet, despite the rise of bacteriology, some aspects of how disease was spread were still not widely understood by many MOHs at that time, in particular a form of transmission which increased the risk of disease spreading in the warmer months. Anne Hardy suggests that horses alone ensured breeding right at the annual peak time of year for fly activity, due to the fact that farmers were just too busy to regularly relieve urban environments of its manure, so piles of manure built up.Footnote 83 However, flies also had easy access to human faecal waste through conservancy. Biehler refers to a twentieth-century example of 2.3 acres of mismanaged trenching in India, filled with human waste, which reportedly produced in the region of 24 million flies.Footnote 84 Although less hot, the warmer summer months in Birmingham offered thousands of reeking pails and ashpits, three major central processing plants, as well as tons of nightsoil and market refuse left at canal wharves waiting for transport out of the city. In 1849, Joseph Hodgson offered a description of the problem in Birmingham at a time when only ashpit waste and horse manure were created by a much smaller population: ‘depots of manure by the side of the canal…In the summertime swarms of flies, millions upon millions of flies, infest the houses in the neighbourhood.’Footnote 85 It was not much better in the early twentieth century when a resident of a court in Aston reminisced about living with a pail privy: ‘the toilets were big containers under the seat…Every week they were emptied by the nightsoil men and when they were due everyone closed their windows and bunged up any holes because the flies were everywhere.’Footnote 86

This supports Morgan’s findings for Preston and the relationship between large horse populations, flies and enteric disease. Other studies have also highlighted either the climate, the proximity of animals to living space or choice of waste management and their impact upon public health.Footnote 87 More importantly, this offers further evidence, supporting Buchanan’s point, that privy waste disposal methods were an important factor for the impact of the house-fly. Hence, in addition to horse populations, conservancy and waste management should also be considered in the relationship between flies and higher rates of enteric disease and persistently high IMRs. This was a relationship that MOHs in England came to understand more fully in the second decade of the twentieth century.

Medical understanding of flies as a vector of transmission and public health

Hardy suggests that the medical professions were becoming aware of flies as a possible source of diseases in the 1870s to the 1880s.Footnote 88 Yet, it was not until 1904 that Dr James Niven, the MOH for Manchester, first drew attention in England to the problem of flies in the urban environment.Footnote 89 In America as early as 1906, some authorities had introduced measures to enforce stable owners and manure haulers to keep better control on the favoured site for fly-breeding.Footnote 90 This new knowledge did not form part of any national public health campaigns in England before the second decade of the twentieth century, when the government issued circulars to local authorities to warn about the dangers of accumulations of refuse as potential breeding sites for flies.Footnote 91 In 1913, the English entomologist Ernest Edward Austen described how flies were carriers of disease such as ‘cholera, typhoid fever and tropical dysentery’ and that they were also under grave suspicion for ‘maladies’ such as ‘infantile or summer diarrhoea’.Footnote 92 He also confirmed that although horse manure formed the chief breeding site, flies would breed in ‘other excrementitious substances’.Footnote 93

It was not until 1915 that Dr John Robertson, Birmingham’s second MOH, distributed a handbill declaring that flies are ‘probably the MAIN CAUSE of spreading summer DIAHORREA’ and offered six points of advice to help households prevent the ‘fly nuisance’.Footnote 94 Council minutes record that 60,000 public information handbills about the dangers flies posed were distributed to the poorer areas of the city.Footnote 95 The advice centred on the cleanliness of the home and the courtyard area, with advice on the covering of food and good domestic waste management practices. The policy of education placed a ‘private responsibility’ on preventing fly-borne disease, just as Beihler found in America in the 1910s.Footnote 96 The primary target for the handbills were women to educate them about the dangers posed to infants. This was reinforced by health and infant welfare visitors and other connected volunteer organizations.Footnote 97 The same year, an illustrated booklet was also issued to owners of stables across the city to encourage the speedy removal of horse manure with recommendations for the wider distribution of ashbins with lids and for the Cleansing Department to prioritize the emptying of bins at least once a week.Footnote 98 This new public health strategy coincided with the phasing out of the pail system, although men leaving to serve in the war may have also motivated this decision.Footnote 99 Once the pail system had ceased, the city still had conditions conducive for fly-breeding with a large horse population and city centre and canal side waste storage and processing. However, the potential impact of poor waste management was more fully understood with a clear counter strategy. Despite the shift away from ‘crude sanitarianism’ with the rise of bacteriology and greater understanding of the causes and spread of disease, effective waste management in the urban landscape remained vital for public health.Footnote 100

When Hill was making connections about the impact of conservancy on public health in his 1897 and 1899 reports, he made no mention of flies because he had no knowledge of the relationship. French and Warren also noted this in their analyses of MOH reports for the Canbury area, which highlights a particular limitation of rich local sources.Footnote 101 This in turn can lead to continued underappreciation of the impact of flies in later analyses of these sources. For instance, in studies that analyse MOH reports for Birmingham before 1915, there was no mention of the relationship between flies, summer diarrhoea and increased infant mortality. Therefore when exploring the effectiveness of social interventions to tackle infant mortality in Birmingham, as for example in works by Chris Galley and Ruth Procter, consideration of this important factor is missed.Footnote 102 In a later work, Galley considers the findings of Morgan in relation to horses, flies and enteric disease to be important, and rightly highlights other important factors such as the spoiling of food in warm weather, dehydration and unhygienic cleaning and feeding practices for infants.Footnote 103 However, as this article argues, there is also a need to consider contemporary sanitation arrangements and medical understanding at the time.

Conclusion

This article has argued that greater attention should be given to dry conservancy and waste management development across the urban landscape in England. The scant number of studies that explore the local operation of these systems leaves much to do to learn to what extent and for how long they were in use. Local studies benefit larger national research projects, as place-specific context is vital to understand more fully the conditions and challenges that motivated the introduction of pail systems and why they endured. This in turn, will help pinpoint exactly when the transition to water carriage was complete in England.

Exploring conservancy in Birmingham’s courtyards of back to backs adds to our understanding of the impact of living with pail and ashpit privies. Unhygienic practices and shared facilities, along with annual plagues of flies during the summer months, facilitated the spread of faecal–oral disease. A lack of medical understanding of flies as a vector of transmission meant the relationship with conservancy was underappreciated and therefore not referred to in contemporary reports. This has led to the continued underappreciation of the impact of conservancy in later analyses. When exploring aspects of public health in localities, such as infant mortality, sanitation and waste management as well as medical knowledge and practice are important considerations.Footnote 104

Despite investment in sanitation infrastructure, the evidence from Birmingham suggests that it did not immediately translate into improving sanitation for all citizens and significantly reduce mortality. Part of this investment included infrastructure and new technology for the new pail system, implemented initially in good faith by the council as a solution to the city’s sewage crisis, but this was a sanitation system that became an additional danger to public health. Birmingham’s investment in water supply and sewage treatment laid the foundations for a more widespread impact later in the inter-war years. There could be up to a 30-year lag before the full benefits of this investment was felt by the poorest citizens of Birmingham, with the phasing out of conservancy and conversion to WCs.Footnote 105 These findings have implications for the existing debates surrounding the contribution of sanitary investment to mortality decline. Firstly, in respect to measuring the contribution of loan financed public works.Footnote 106 The financial situation over the Elan Valley Scheme demonstrates that sole reliance on data about loans cannot offer the complete picture and this supports the suspicion of Harris and Hinde that there is a need to know how money borrowed was used and what challenges were faced.Footnote 107

Secondly, the findings in Birmingham do not support the suggestion by Chapman that sanitation infrastructure accounted for 60 per cent of urban mortality decline between 1861 and 1900. Findings may go some way to support McKeown’s original, though disputed, claims. They also fit with what Aidt et al. identify in their study as the ‘late persistence of high rates of diarrhoea’, even though water-borne diseases had declined.Footnote 108 Despite definite improvement in terms of water quality and then quantity after 1904, the benefits were ‘cancelled out’ for those living in Birmingham’s back to backs with ashpit and pail privies.Footnote 109 Subsequently, the Aidt et al. study has instigated further research into the relationships between urbanization and mortality from faecal–oral diseases in Britain.Footnote 110 The extent and longevity of urban conservancy systems should be evaluated when assessing these relationships.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their input and Malcolm Dick for reading initial drafts and offering valuable comments.

Competing interests

The author declares none.