Introduction

The year 2019 in Italy was marked by contentious elections to the European Parliament (EP) that confirmed the momentum of Matteo Salvini and the tumbling support for the 5 Star Movement/Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S). The enduring disputes between government allies M5S and League for Salvini Premier/Lega Salvini Premier (LpSP) ultimately led to the collapse of the first Giuseppe Conte Cabinet, the formation of a new coalition executive (Conte II), this time between the M5S and the Democratic Party/Partito Democratico (PD), and the return of the League to the opposition. Various issues dominated public debates, notably migration, climate and infrastructures, as well as law and order. Over the year, the League consolidated its central role in the Italian political system.

Election report

European Parliament elections

The EP election was held on 26 May. The turnout was 54.5 per cent. That was 2 percentage points less than in 2014, in contrast to most other European countries where more citizens voted than at any time in the past. Trust in the European Union (EU) attained a record low: only 37 per cent of Italians tended to trust the EU, whereas 55 per cent expressed distrust (European Commission 2019). In sum, the wind of change was on its way. The EP changed the balance of power in the first Conte government, marking a tipping point of the ascension of Italy's then Minister of Internal Affairs, Matteo Salvini.

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament in Italy in 2019

Note: aThe lists of The Left ran in 2014 under the label Other Europe for Tsipras.

Source: Ministero dell'Interno (2019).

Salvini's League was both the recipient and the main expression of EU discontent, and it was the only party that was not weakened upon the election. Salvini ran a well‐organized campaign associated with strong anti‐immigration and anti‐establishment messages, calling for restrictive borders policies and in‐depth changes in the economic governance of the EU. After the ballots, the League realized its best result at the EP elections. It obtained 34 per cent of the votes (and 29 EP seats), and this was higher than in 2014 when the party obtained just 6 per cent of the vote (and five EP seats).

In contrast, the M5S (Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group, EFDD), suffered major losses. Squeezed between government responsibility and an anti‐establishment base, the M5S run an uncertain campaign. It hesitated between strong positions against specific EU policies (such as the single currency and the fiscal compact) and vocal calls to give stronger powers to the EU to bring it closer to its citizens. Ultimately, the M5S obtained 17 per cent of the vote (and 14 EP seats), which is around 4 per cent less than in 2014 (17 EP seats).

The centre‐left PD (Alliance of Socialists and Democrats Group, S&D) suffered the greatest loss even if it were placed second ahead of the M5S. Riven by its internal divisions in the months that preceded this election, the PD approached the ballot with its newly appointed leader Nicola Zingaretti. Consistently pro‐European, the PD advocated for stronger economic leadership at the EU level. It also called for new stricter regulations of EU asylum policies and for fostering employment measures while containing public speeding. Ultimately the PD lost 17.4 per cent of the vote from 2014 (and 12 EP seats), when the party scored its record in EP elections.

Increasingly challenged by the far‐right Brothers of Italy/Fratelli d'Italia (FdI), Silvio Berlusconi's centre‐right Go Italy/Forza Italia (FI) continued its electoral decline. The FI campaigned on increasing investments to foster employment, and agreed with the League on implementing the flat tax. In comparison with the 2014 EP elections, Berlusconi's party's results were basically halved (from 16.8 per cent to 8.8 per cent) and it lost seven seats.

Tax reduction was also at the core of EP election campaign of the far‐right FdI (European Conservatives and Reformists Group, ECR). The party campaigned on strengthening military controls of European external borders, abandoning austerity and EU‐wide protection of Made in Italy products. Despite the competition with both the League and FI, the FdI achieved a positive result. It gained 2.8 per cent of the vote compared with the 2014 election, passing from 3.7 per cent (and no EP seats) to 6.5 per cent (obtaining five EP seats). This result was also an improvement from the 2018 general elections, when FdI obtained 4.4 per cent of the vote.

Finally, a smaller organisation +Europe/Italy in Common/+Europa/Italia in Comune (+Eu) (Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Group, ALDE) also participated in the elections, but with poor results. Probably the most pro‐European party in Italy, it campaigned on the proposal of a European system of unemployment subsidy. The party obtained only 3 per cent of the vote and no seats.

Overall, the electoral campaign focused on the consequences of the asylum policy crisis, the cleavage between fascism/antifascism, the stability of the first Conte government, and the questionable efficacy of EU monetary governance with Salvini in one way or another always at the centre of the scene. Some issues that instead are important at the supranational and EU levels have been absent. This is notable in the case of climate change which instead mobilized students in the streets (see below).

The consequences of the 2019 EP elections led to a change in government majority, resulting from the exacerbated divergences between the M5S and the League, and the growing popularity of its leader, Salvini, and its anti‐immigration campaigns.

Regional elections

In addition to the EP election, regional elections took place in five of Italy's 20 regions: Abruzzo (10 February), Sardinia (24 February), Basilicata (24 March), Piedmont (26 May) and Umbria (27 October). The elections mirrored ongoing trends at the national level, confirming the momentum of Salvini's League, the progressive popularity drop of the M5S, and the enduring struggles of the PD. Indeed, while in the aftermath of the Conte II government deal, the M5S and PD struck a coalition deal for the Umbria elections, the candidates of the centre‐right coalition won in the five regions, all of which were originally ruled by the PD. The elections also mirrored the progressive reshaping of Italy's centre right bloc, mainly thanks to the increasing popularity of the FdI. While Salvini confirmed his predominance over the centre right, a candidate by the FdI was elected president in Abruzzo, whereas Giorgia Meloni's list doubled the score of the FI list in Umbria, further contributing to the side‐lining of Berlusconi's party.

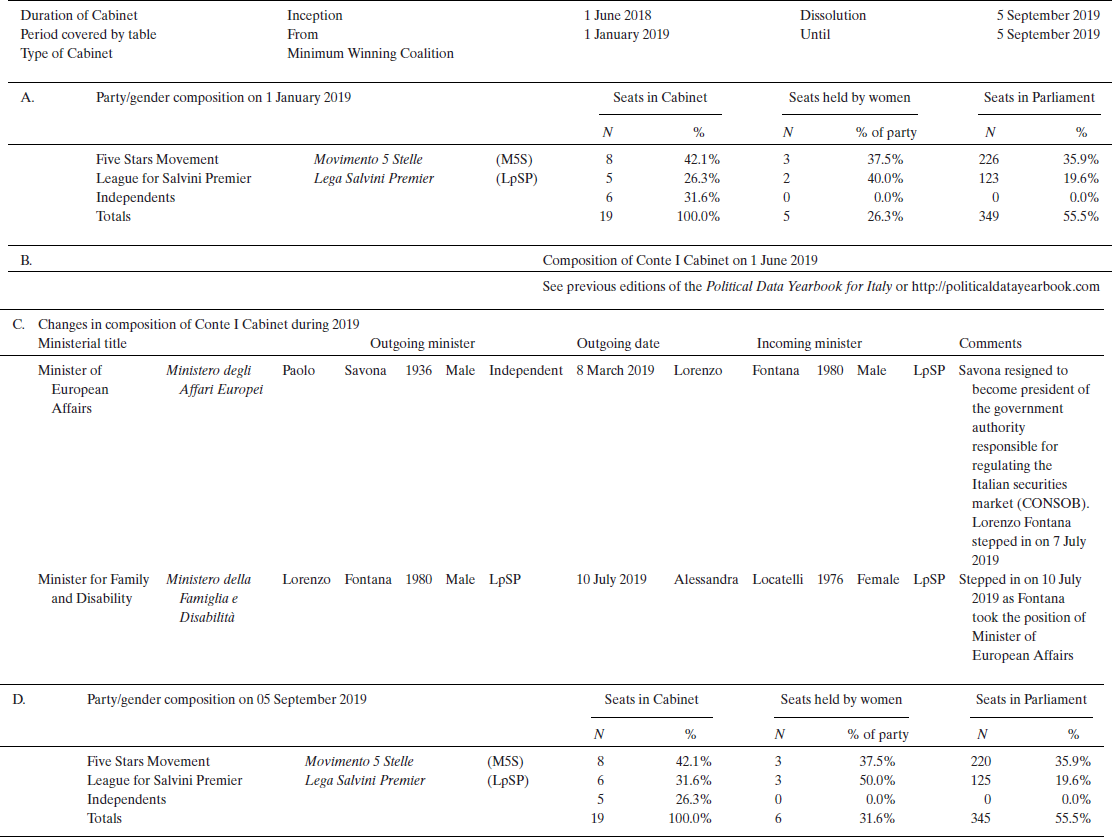

Cabinet report

In the months that preceded the EP election, Italy's EU Affairs Minister Paolo Savona resigned. While officially the decision was motivated by another appointment as the new head of bourse regulator CONSOB, the resignation took place after weeks of growing tensions within the governing coalition that kept refusing Savona's proposal to challenge EU budget rules. The consequences of the EP and regional elections paved the way for the fall of the Conte I government and for the formation of Conte II.

After 14 months of bickering, the government coalition bringing together the M5S and the League collapsed in August 2019. The Conte I government came apart after a mutinous power play by Interior Minister Salvini, who tried to amplify conflict inside the coalition surfing on the wave of the League's positive results at the 2019 EP election.

Tensions between the two allies first emerged when the League decided to oppose the appointment of Ursula von der Leyen as next President of the European Commission, while the M5S backed her. Conflict intensified over the heated discussions on the introduction of the flat tax, a fiscal measure (unsuccessfully) sponsored by the League and opposed by the M5S. Ultimately, the issue over which Conte I collapsed was the construction of the Turin–Lyon high‐speed railway, supported by the League and opposed by the M5S. All over the summer, during a highly mediatized ‘beach tour’, Salvini repeatedly announced that he was fed up with the M5S's incompetence and inaction and openly made a bid for early elections, asking Italian voters to give him unrestrained power. On 20 August Conte announced to the Senate that he would present his resignation. He did this in anticipation of a no‐confidence vote that had to take place on the same day. In his speech in front of the Senate, Conte openly pointed at Salvini for setting in motion a ‘dizzying spiral of political and financial instability’ and for sacrificing the government's survival in favour of his eagerness to become Prime Minister.

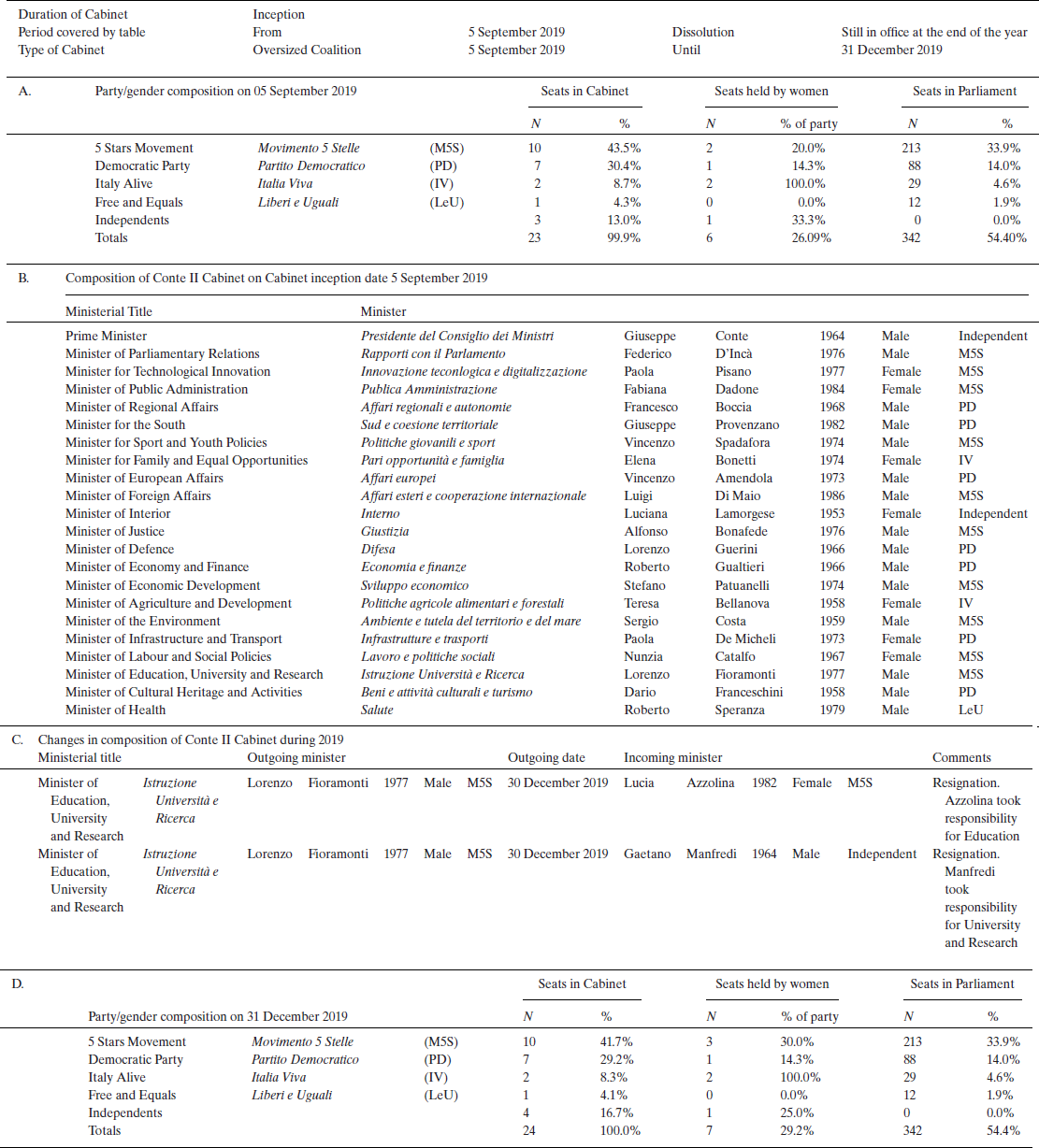

After weeks of consultations under the supervision of the President of the Republic Sergio Mattarella, the M5S and the PD agreed to form a new coalition government headed again by Conte (Conte II). The two parties signed a joint platform (‘Accordo di Governo’) including 26 points, whose endurance is highly unpredictable. In December 2019, Italian Education Minister Lorenzo Fioramonti resigned after writing a letter to Prime Minister Conte, citing a lack of government funding to schools, universities and research as the key to his decision.

Parliament report

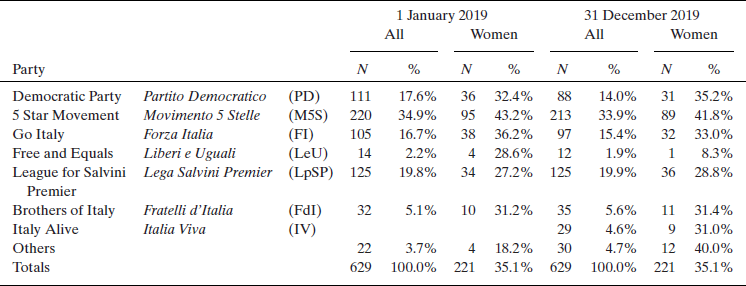

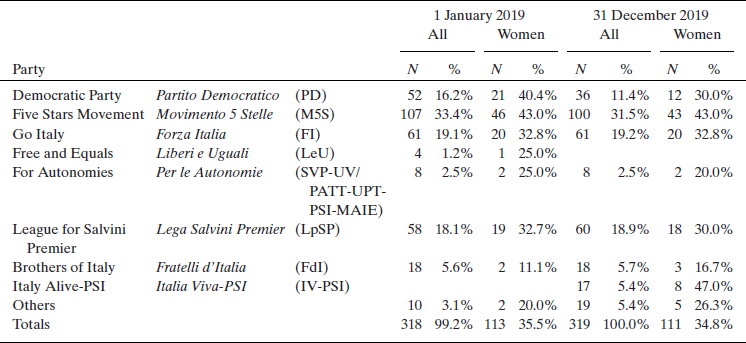

During 2019, the splits and exits from the parties in Parliament continued. While various parties experienced some outflow, the M5S and the PD suffered specifically.

Within the M5S, MPs quit the parliamentary group criticizing the party as too moderate and/or too radical on various issues (notably the economy, climate and migration), and ultimately joined various parliamentary groups. After the splinter, the PD lost a group of MPs led by Matteo Renzi and Maria Elena Boschi that joined a new parliamentary group in September: ‘Italia Viva–PSI’.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (Camera dei Deputati) in Italy in 2019

Source: Camera dei Deputati (2019).

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the Senato della Repubblica in Italy in 2019

Source: Senato della Repubblica 2019.

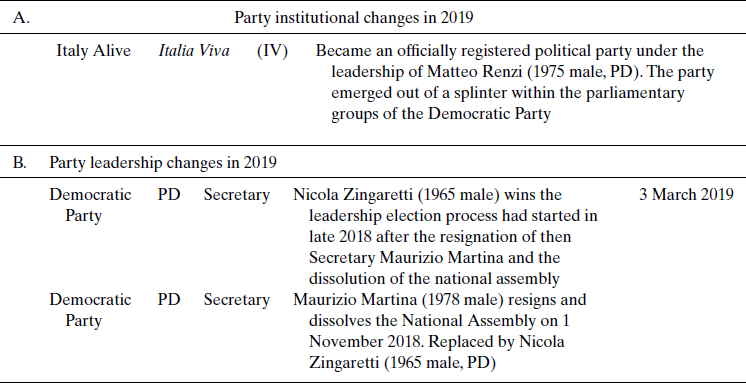

Political party report

The most notable development concerned the PD. In March, Zingaretti was elected new secretary of the party. He is currently president of the Lazio region, which includes Rome. The other candidates to the primary election were Roberto Giachetti, considered the closest to former PD leader and Prime Minister Renzi's centrist politics, and Maurizio Martina, a former agriculture minister. The primary election was triggered by the resignation of former Prime Minister Renzi on 12 March 2018, following the party's defeat at the 2018 general election. A few months after Zingaretti's election, Renzi decided to leave the PD, which agreed to form the Conte II government with the M5S. Renzi formed a new party called Italia Viva/Italy Alive (IV).

During the same period, the FI also experienced internal tensions when Mara Carfagna (former equal opportunities minister) tried (unsuccessfully) to gather support within the party to protest Berlusconi's decision to ally with Salvini.

Institutional change report

In October 2019, the Chamber of Deputies approved by a large majority – 553 votes in favour, 12 against and two abstentions – a reform that will reduce the number of MPs from 630 to 400 and from 315 to 200 senators. The reform was voted by the M5S, the party that promoted it, with the Cabinet allies of the PD, IV, Free and Equals/Liberi e Uguali (LeU), but also by the major opposition parties: the League, FI and FdI. Among others, the MPs of +Eu voted against it. To come into force, however, the constitutional reform needed confirmation by referendum – which was slated for March 2020, but which has been postponed due to the Covid‐19 outbreak.

Issues in national politics

Alongside the EP elections and formation of Conte II, other major themes dominated politics throughout 2019: migration, climate and infrastructure, as well as law and order.

Vivid debates about immigration and citizenship rights revolved around three core events: the ban on Riace's Mayor Domenico Lucano, the arrest of Sea‐watch Captain Carola Rackete, and the hijacking of a school bus stopped thanks to teenager Ramy Shehata. Lucano was the Mayor of Riace, a small hilltop village in Calabria internationally known for the way in which migrants were integrated into the local community. Lucano was arrested in 2018 and charged with aiding and abetting illegal immigration. After being released, in 2019 he was banned from residing and visiting the town whilst the investigation and court cases against him proceeded. Captain Carola Rackete was arrested on 29 June 2019 for entering Italy's Lampedusa port with the non‐governmental organization (NGO) Sea‐Watch boat, despite a veto imposed by far‐right Interior Minister Salvini, and knocking a coastguard boat out of the way to land 40 migrants after over two weeks blocked at sea. A judge overturned the arrest three days later, saying that Rackete had acted just to save lives. During the same year, a teenage of Egyptian citizenship, Rami Shehata, helped the authorities to stop the hijacking of a school bus outside Milan by secretly ringing his father and telling what was happening while the driver was threatening 51 children. In 2019, both Lucano and Rackete became the target of ferocious campaigns by Interior Minister Salvini. The case of Shehata fuelled debates about the requirements to obtain Italian citizenship.

In response to Salvini's policies and to counter the League's campaigns for the 2020 regional election in Emilia‐Romagna, the Sardine (Sardines) started taking to the streets. The Sardines are a grassroots movement funded in mid‐November by a group of four friends from Bologna. It attracted a huge following, with tens of thousands of supporters cramming into piazzas across the country.

Climate change was another issue central to public debates, and this was notably related to the emergence of grassroots climate protests and to reactions to the devastating flood of Venice. In 2019, the #FridaysForFuture climate protests mobilized thousands of students across Italy, notably in Rome and Florence (Wahlström et al. Reference Wahlström, Kocyba, De Vydt and de Moor2019). During the same year, Venice was hit by one of the most devastating floods in the last 50 years which caused three‐quarters of the city to be submerged by seawater. Against the backdrop of the disaster, the debate rapidly focused on climate change, but also on corruption slowing the completion of the MOSE, that is, an underwater barrier system that was supposed to protect the city and to be working by 2011, but which was still not operational after more than 16 years of construction.

Other relevant issues in 2019 include debates on the arrest of fugitive Cesare Battisti in Bolivia, and on a breakthrough in the case of Stefano Cucchi's death in custody, for which two carabinieri were found guilty of having brutally caused his death.