Introduction

It is common wisdom that the process of European integration has downplayed the salience of national borders, resulting in a ‘borderless’ Europe (Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2021). It has, however, altered the nature of border regions and contributed to their relevance in new ways. Border areas used to be (marginalized) buffer zones between competing European nation‐states or sites of military installations, but they have since evolved into integration ‘bridges’. They connect the territories of European member states and are, therefore, considered living labs of European integrationFootnote 1 where one of the key cornerstones of the European project, freedom of movement, is manifested in its purest form. According to the European Committee of the Regions, approximately 150 million people, which constitutes around 30 per cent of the European Union's (EU) population, reside in European border regions today.Footnote 2 Although scholars argue that borders have lost their significance as symbols of the Westphalian state in Europe, we show in this study that borders still play vital roles: They can colour public sentiments and perceptions towards European integration.

The fundamental question our study seeks to contribute to is why citizens support (or oppose) European integration. This question has attracted considerable attention from scholars of European politics in the past two decades, partially as a result of the expansion of European integration to areas of ‘core state powers’ (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2014) and the increasing importance of public opinion in Europe (Green‐Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2012; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). However, when considering public opinion and support for European integration, it becomes apparent that the role of geography, let alone borders, has often been neglected, with a few sporadic exceptions (e.g., Gabel & Palmer, Reference Gabel and Palmer1995; Gabel, Reference Gabel2001; Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012).Footnote 3

In the current study, we extend beyond existing accounts and pay careful attention to how geography can shape public sentiments towards higher levels of governance, focusing on the impact of borders. Our understanding of borders surpasses borders per se as physical lines of demarcation and focuses on borderlands, which we perceive as socio‐geographic spaces (Enos, Reference Enos2017, p. 3), where social phenomena induced by borders, such as perceptions, stereotypes and behaviours, are experienced (Popescu, Reference Popescu2008). We, therefore, perceive borderlands as socio‐geographic spaces characterized by their unique position at the margins of two or more distinct regions or territories. These spaces often exhibit a dynamic interplay of cultural, political, economic and social forces due to their proximity to multiple, sometimes contesting, centres of power and influence. Nonetheless, European border regions have unique characteristics that motivate us to investigate the attitudes of their inhabitants closely. Elsewhere in the world, international borders are commonly regarded as vital bastions of security and military installations, as evidenced by the escalating global trend towards reinforcing border security measures and fortified border infrastructure (Mutz & Simmons, Reference Mutz and Simmons2022; Simmons & Kenwick, Reference Simmons and Kenwick2022). In sharp contrast, however, and as a result of the freedoms established by the EU,Footnote 4 border regions have become epicentres of cross‐border economic activities, service exchange and transnational labour and migration flows, embodying the principles of free movement within the EU. Consequently, contiguous territories placed at different sides of internal EU borders became interdependent, as evidenced by the emergence of quasi‐autonomous coordination structures combining border regions from different countries, the so‐called Euroregions, and the numerous EU initiatives directed to borderlands, such as Interreg programs. In sum, several social, economic, political as well as institutional developments resulting from the internal debordering of Europe (Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2021) make it likely that the socio‐political context of Europe's border regions to be critical in shaping the political attitudes and behaviour of their residents. The question is how the unique environment that borderland residents navigate in their everyday experiences will impact their political perceptions and attitudes towards the EU.

A few studies have suggested that inhabitants of the borderlands are more optimistic about the EU. According to Gabel and Palmer's (Reference Gabel and Palmer1995) analysis of Eurobarometer data, people in border regions, which they operationalize in terms of NUTS‐2 regionsFootnote 5, have a more favourable perception of the EU. In a similar line, Kuhn (Reference Kuhn2012), focusing on Germany and France, demonstrates that German border regions are more optimistic about the EU. In contrast, French border regions are not different compared to core regions (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012).

However, we suspect that the role of borders is far from clear‐cut or even one‐sided. Borders can act as integration bridges, but their roles as barriers cannot be neglected (O'Dowd, Reference O'Dowd2002). Interactions with strangers can contribute to the emergence of multi‐layered identities, but they can also amplify cultural differences and disparities. Economic cooperation can generate positive externalities that benefit all, but competition over scarce resources created by disparities on both sides of the border can breed negative sentiments. Furthermore, the recent movements towards re‐bordering and the rise of challenger parties make the effect of borders unclear. The latter thrive electorally on demonizing strangers, leading to possibilities of finding support in particular in regions where strangers are physically closer, as in border regions. In sum, we suspect that the effect of borders is not clear‐cut, and we seek to investigate more thoroughly the political behaviour and attitudes of borderland inhabitants in Europe.

Indeed, our findings point to surprising and novel directions from behavioural and attitudinal perspectives. Employing fine‐grained voting data from the European NUTS‐Level Election Dataset (EU‐NED) dataset (Schraff et al., Reference Schraff, Vergioglou and Demirci2023), public opinion data from the Eurobarometer, and statistical matching, we find robust evidence that border regions hold more pronounced negative attitudes towards the EU. First, our findings demonstrate that NUTS‐3 border regions support Eurosceptic and far‐right parties more strongly compared to core regions. Eurosceptic parties receive around 1.4 percentage points more votes in border regions, which is a considerable electoral advantage when the relatively small vote share of these parties and the low electoral thresholds applied in many EU member states are considered. Furthermore, we analyse Eurobarometer data from 15 EU member states to better understand the nature of public attitudes in these regions. Using multiple outcome variables and exact matching, we find consistent evidence that borderland inhabitants view the EU less positively and trust it less. Our mediation analysis points to intriguing institutional mechanisms. It demonstrates that borderland inhabitants place less trust in their national political institutions, which translates to less trust in the EU.

How geography shapes public attitudes

Recently, several strands of political science literature have suggested that the place of residence, or place‐based identities, can affect individuals' political attitudes and behaviour (Huijsmans, Reference Huijsmans2023; Jennings & Stoker, Reference Jennings and Stoker2016; Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2019). Scholars have documented considerable variation in people's attitudes and behaviour based on where they live, which is argued to shape their experiences and perceptions. The most prominent distinction featured in this literature is the urban–rural divide. Jennings and Stoker (Reference Jennings and Stoker2016), for example, highlight the existence of two versions of England: a cosmopolitan England – mostly found in larger cities – where citizens exhibit cosmopolitan and liberal attitudes, and ‘backwaters’ provinces – mainly found outside large cities and in rural areas – where citizens hold relatively conservative and nationalist attitudes. Jennings and Stoker (Reference Jennings and Stoker2016) demonstrate that these differences not only exist but also increase over time, suggesting their increasing importance and relevance. These differences are not unique to England; they are almost observed everywhere else to the extent that urban–rural divides are considered a global social cleavage (Guilluy, Reference Guilluy2016; Huijsmans, Reference Huijsmans2023; Lyons & Utych, Reference Lyons and Utych2023; Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2019, Reference Maxwell2020; Walsh, Reference Walsh2012). This literature agrees that place of residence can shape people's identities, their understanding of in‐ and out‐group members and, consequently, their political attitudes and behaviour. In the words of Enos (Reference Enos2017), geographical spaces lead to psychological and cognitive spaces which in turn lead to political spaces.

But why do places shape attitudes? This literature relies upon the effect of the context, usually known as contextual effects, which makes the case that locations as such are distinctive to their inhabitants such that the experiences they live colour their attitudes (Books & Prysby, Reference Books and Prysby1988, Reference Books and Prysby1991; Enos, Reference Enos2017; Ethington & McDaniel, Reference Ethington and McDaniel2007). Books and Prysby (Reference Books and Prysby1991), for example, demonstrate that contextual effects could take place through everyday experiences and events that people live, their understanding of local issues the political information channelled through local organizations, and the institutional and social networks prevalent locally. Nonetheless, other scholars argue that the observed contextual effects of places could be confounded by compositional effects, which contend that people self‐select into places that mirror their views and interests (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2019, Reference Maxwell2020). While we are not particularly interested in this debate, we have strong reasons to argue that borderlands are distinctive due to intertwined cultural, economic and political circumstances that colour their inhabitants' perceptions of and support for the EU. Our empirical analysis also combines aggregate and individual‐level analysis to control for (and match on) important individual‐level factors and tease out some mechanisms related to the context rather than individuals' characteristics.Footnote 6

Are Borderlanders more or less Eurosceptic?

We agree with the existing literature that variations in social contexts of geographical places are consequential for their inhabitants' perceptions (Ethington & McDaniel, Reference Ethington and McDaniel2007). Moreover, we contend that this effect is by no means limited to urban–rural divides but is also observable along other geographical lines, among which are borders and border regions. We conceive of borderlands as socio‐geographic spaces where unique phenomena to borders and their perceptual and attitudinal consequences are manifested (Enos, Reference Enos2017). Speaking of the EU, border regions have acquired a distinct character due to various factors. Positioned strategically along the EU's internal borders, these areas have evolved into vibrant hubs characterized by increased cross‐border economic activity, service exchanges, labour commuting and migration flows. Consequently, this heightened level of transnational interactions has engendered interdependence among border regions situated within different EU member states. Responding to these unique circumstances, quasi‐autonomous institutional structures have emerged with the aim of dealing with the specific needs and challenges facing their residents. Therefore, we expect that the daily milieu that borderland residents navigate will significantly shape their perceptions and attitudes towards the EU.

The main question that arises is how borders can shape the political attitudes and behaviour of borderlands' inhabitants. Previous research suggests that living in border areas makes one more inclined to view the EU positively for economic and cultural factors (Gabel & Palmer, Reference Gabel and Palmer1995; Gabel, Reference Gabel1998; Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012). In an early study of public support for European integration, Gabel and Palmer (Reference Gabel and Palmer1995) expected proximity to the borders of the European Community to be among the drivers of optimistic views of the European integration process (see also Gabel, Reference Gabel1998). They argue that citizens in regions bordering other EC members ‘may have greater opportunities to exploit liberalized commodity, labour, and financial markets’ and, therefore, support European integration (Gabel & Palmer, Reference Gabel and Palmer1995, p. 8). Thus, because border regions are characterized by cross‐border economic mobility embodied in the exchange of goods, services and labour, individuals residing close to the EU borders might benefit from their ability to cross the border and look for better services and career prospects. Indeed, finding a job across the border, Schönwald (Reference Schönwald, Lechevalier and Wielgohs2013, p. 120) finds, was the primary positive perception her interviewees held about the Greater Region located between Germany, France, Luxembourg and Belgium.

From a cultural perspective, the freedom of movement installed by the EU and the resulting social, economic and political interactions between regions on different sides of the borders have been shown to reduce ignorance about other groups, promote stable forms of cooperation and create a transnational identity for individuals moving across borders (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012, Reference Kuhn2015; Schönwald, Reference Schönwald, Lechevalier and Wielgohs2013). Paying close attention to the role of borders, Kuhn (Reference Kuhn2012) expects that living in border regions correlates with optimistic views about the EU. In addition to the aforementioned economic dynamics, she also highlights cultural factors related to social interactions and individuals' mobility. She argues that residents of border regions are more likely to engage in social interactions targeting non‐materialistic goals, such as friendships and socialization, and, consequently, have more chances to develop a transnational identity. Kuhn (Reference Kuhn2012) finds support for her expectations in Germany, whereas French border districts were not distinct from core regions.

Furthermore, Kuhn (Reference Kuhn2012, Reference Kuhn2015) finds that the level of transnationalism has a positive effect on EU support. Nonetheless, differences in this regard between inhabitants of border and core regions are limited, making the positive effect of transnationalism unspecific to border regions as such (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012, p. 109). In contrast, however, Ciornei and Recchi (Reference Ciornei and Recchi2017) find a limited effect of transnationalism on individuals' willingness to share resources with other Europeans, an important component of European identity (Verhaegen, Reference Verhaegen2018).

In sum, from these insights, we can expect that residents of border regions are more supportive of the EU compared to residents of core regions.

-

Hypothesis 1. Residents of borderlands view the EU more positively compared to residents of core regions.

However, we contend that the impact of borders is far more intricate than posited by previous empirical findings. Borders can serve as bridges connecting diverse territories but also as symbols of demarcation that separate distinct regions (O'Dowd, Reference O'Dowd2002). They represent not only physical boundaries but also delineate economic, cultural, linguistic and historical differences. Thus, while proximity to foreigners may foster prospects for cooperation, it also opens the possibility for increased contention. In summary, we maintain that there are valid reasons to anticipate that borderlands continue to witness social and political processes that could exert a negative influence on public opinion. In what follows, we seek to flesh out these mechanisms and evaluate their effect empirically.

First, transnational interactions do not necessarily carry positive consequences or lead to the formation of multilayered and cosmopolitan identities. By contrast, negative attitudes could evolve as a result, especially in the presence of strong stereotypes about the out‐group members, rapid demographic changes that threaten one's neighbourhood or competition over scarce resources (Allport, Reference Allport1954; Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2010; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010; van Heerden & Ruedin, Reference van Heerden and Ruedin2019). Kuhn (Reference Kuhn2015, p. 127), for instance, postulates that transnational cross‐border interactions could lead to negative consequences on residents who are not transnationally active since these individuals ‘might feel overwhelmed and marginalized by the transnationalization of their environment’. In a different context, Hangartner et al. (Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2019) and Dinas et al. (Reference Dinas, Matakos, Xefteris and Hangartner2019) demonstrate that contact with incoming Syrian refugees made inhabitants of the receiving Greek islands more hostile towards strangers and more inclined to prefer exclusionary politics.

Furthermore, transnational encounters in border regions might lead to negative externalities, especially in the presence of strong economic disparity between strangers. Rippl et al. (Reference Rippl, Bücker, Petrat and Boehnke2010) hypothesize that transnational social capital, which they define in terms of the intensity of cross‐border interactions, carries less positive externalities when economic differences at the borders are heightened. Mazzoleni and Pilotti (Reference Mazzoleni and Pilotti2015) also demonstrate that inhabitants of Ticino, the Swiss canton bordering northern Italy, hold the strongest negative attitudes towards immigration among all Swiss cantons. Citizens of Ticino were highly concerned about competition in the labour market as a consequence of foreign workers moving across borders. Balogh (Reference Balogh2013) also highlights similar resentments among German citizens living in the Vorpommern region regarding cross‐border Polish workers from the city of Szczecin. Economic concerns may also arise in the disadvantaged region, as its residents may perceive that the prosperous regions are benefiting from their labour without bearing the cost in terms of education, training and infrastructure development (Decoville & Durand, Reference Decoville and Durand2019, p. 139).

Furthermore, borders can also serve as prominent markers of demarcation that define the distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’, potentially giving rise to stereotypes and discrimination against individuals belonging to different groups. In the Greater Region, constituted of sub‐regions from Germany, France, Belgium and Luxembourg, Schönwald (Reference Schönwald, Lechevalier and Wielgohs2013) identifies distinct and unfavourable stereotypes held by French‐ and German‐speaking residents regarding each other's perceived levels of flexibility, efficiency and discipline in the workplace. Regions on the edges of this region are also less inclined to cooperate with the others, and Luxembourgers – being the only nation fully contained in the Greater Region and the strongest economy of its constituent sub‐regions – perceive cultural and identity threats from openness to neighbouring regions (Schönwald, Reference Schönwald, Lechevalier and Wielgohs2013). Finally, Decoville and Durand (Reference Decoville and Durand2019) show that cross‐border interactions do not necessarily foster mutual trust among inhabitants of borderlands. Consequently, while border experiences may contribute to the formation of complex and multifaceted identities, they are equally likely to foster nationalist attitudes (Mazzoleni & Pilotti, Reference Mazzoleni and Pilotti2015), which have been found to correlate with Euroscepticism (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2004).

We also envision non‐economic and non‐cultural developments that might lead to negative attitudes in border regions. From an institutional perspective, European cross‐border regions have evolved in a way that led to the emergence of local networks of governance which enjoy quasi‐autonomy from their composite national governments. Such local and regional communities ‘can emancipate themselves vis‐a‐vis nation‐state dominance’ (Perkmann, Reference Perkmann2003, p. 135). Cross‐border cooperation refers to ‘a voluntary process in which states or sub‐national territorial units act together for a common purpose or benefit without pooling sovereignty to a supranational body,’ and whereby these regional bodies are more aware of the daily needs of borderland inhabitants (Weber, Reference Weber2022, p. 5).

The experience of relying on local problem‐solving efforts, when considered side by side with decisions made by the central government that might fail to adequately consider the daily needs of borderland inhabitants, can contribute to the development of negative attitudes towards higher levels of governance, such as national governments and potentially the EU. Such sentiments were particularly evident during the initial wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic when central governments implemented measures that significantly impacted the lives of individuals in border regions without adequately considering their unique circumstances. For instance, Weber (Reference Weber2022) shows that the German government's decision to close borders in the SaarLorLux region resulted in severe disruptions for residents who were unable to return home or receive necessary medical assistance during emergencies. Consequently, the institutional developments within Euregios, aimed at redefining the territory and establishing customized local solutions and networks, may prompt borderland residents to advocate for their interests in relation to higher levels of authority. Consequently, due to the conflicting interests between local and national authorities, negative attitudes towards national governments might extend to the EU (Anderson, Reference Anderson1998; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Meer and Vries2013).Footnote 7

Finally, (local) political actors can capitalize on the prejudice towards members of out‐groups, thereby reinforcing conservative attitudes in borderlands. For example, in some border areas, radical right actors have taken advantage of the lack of secured national borders to oppose the EU. Since its inception, the Geneva Citizen Movement has focused its campaign rhetoric on promising to eradicate cross‐border commuters from France (Bernhard, Reference Bernhard2017, p. 512). Geneva, an area that shares 90 per cent of its borders with France, teems with anti‐commuter posters even in public transport at times of elections.Footnote 8 Other radical parties such as the Swiss People's Party have followed suit (Bernhard, Reference Bernhard2017). Similarly, in France, the National Rally (RN) has a significant base near borders such as the Lorraine region, which is adjacent to Luxembourg. In regional elections, the RN constantly attacked the EU and defended national sovereignty against ‘agents of economic, political and cultural borderless globalization’, a discourse that attracted a considerable number of local supporters (Lamour, Reference Lamour2023, p. 4). The same pattern has been noticed on the German–Polish border in the Vorpommern region. At the same time that the borders with Poland were being opened, the radical right party NPD has found strong support in the German part of the border. Its rhetoric was based on assaulting Polish commuters and employing them as a scapegoat for the region's problems (Balogh, Reference Balogh2013, p. 195). Previous research has shown that cue‐taking, especially with regard to the EU due to its intricate and multilevel structure, can be particularly effective in shaping public attitudes towards the EU (Hooghe, Reference Hooghe2007). Therefore, radical rhetoric targeting strangers in border regions might induce negative sentiments.

Overall, these considerations show that, while residents of borderlands experience the benefits of integration more directly than residents of core areas and cities, they may still encounter local social, economic, and political characteristics that fuel feelings of nationalism and Euroscepticism.

-

Hypothesis 2. Residents of borderlands view the EU less positively compared to residents of core regions.

In what follows, our aim is twofold: firstly, to assess the impact of residing in border regions on EU support and, secondly, to examine the influence of the aforementioned economic, cultural and institutional mechanisms. It is worth noting that although we acknowledge the existence of a fourth mechanism pertaining to party rhetoric, we are unable to evaluate this particular aspect due to data limitations. We will turn to this concern in greater detail in the subsequent empirical and discussion sections of the paper.

Data and methods

Rather than considering attitudes towards the EU alone, we seek to combine both attitudinal and behavioural indicators of citizens in border and core regions. We, therefore, conduct our empirical analysis in two parts. In the first, we consider behavioural data by studying Eurosceptic voting in border and core regions in 19 EU member states between 1999 and 2019 using the EU‐NED (Schraff et al., Reference Schraff, Vergioglou and Demirci2023), which includes both national and European Parliament elections. The main benefit of this first part is that the data set covers a long period of time and provides us with election results at the very fine‐grained NUTS‐3‐regional level.Footnote 9 In the second part, we use five waves of the Eurobarometer (European Commission, 2023, 2019; European Commission & European Parliament, 2019; European Commission, 2022a, 2022b) surveys from 2018 to 2021 to study respondents' attitudes towards the EU in 15 member states.Footnote 10 Since the period of observations also includes the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic, an empirical concern is whether it has an impact on our analysis. We thus replicate our main analysis using only the three surveys preceding the onset of the pandemic and find that our main findings still hold.Footnote 11

While the first part answers the general question of whether borderlanders are more or less Eurosceptic than others, the second part allows us to shed light on the attitudes and mechanisms driving Eurosceptic behaviour in these different regions. In so doing, we also provide a more holistic picture of borderlands and EU support. By studying both electoral results and attitudes with two very different data sources in multiple EU member states, we are able to provide a more comprehensive analysis of citizens' support for the EU in border regions than previous research. Earlier studies are limited to studying survey data alone (Gabel & Palmer, Reference Gabel and Palmer1995; Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012) – in the case of Kuhn (Reference Kuhn2012) even with a single survey of German and French respondents. Therefore, our analysis provides a more encompassing view of public support for the EU in border regions.

Our main independent variable of interest is a dummy variable that indicates whether a region is or a respondent lives in an internal border region or not. While election data are available at the level of NUTS‐3 regions, the level of Eurobarometer data varies across countries and is typically at the NUTS‐2 level. For any NUTS level, we consider a region of an EU member state to be a border region if it shares a land border with another country that is a member of the EU or the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).Footnote 12 Conversely, we refer to any other region as a core region. We include regions neighbouring EFTA countries because these borders have effectively been subject to much the same debordering as the EU's internal borders. We also create a second dummy variable that codes regions as external border regions if the region neighbours a non‐member state of the EU or EFTA. Throughout the analysis, our main focus lies on internal borders, and we, therefore, frequently omit ‘internal’, referring to them as just ‘border regions’. We thus treat the external border region dummy as a control variable. Using GISCO dataFootnote 13 containing geometric information on European countries and NUTS regions, we compute the distances between each region and any other possible region or third country. For a given region, we then code it as being an internal border region if it has at least one neighbouring region that belongs to another EU/EFTA member state, an external border region if it is bordering on a third country or both.

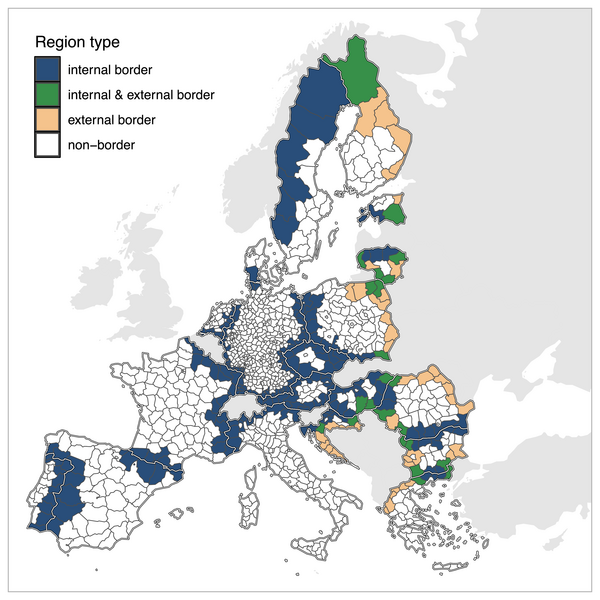

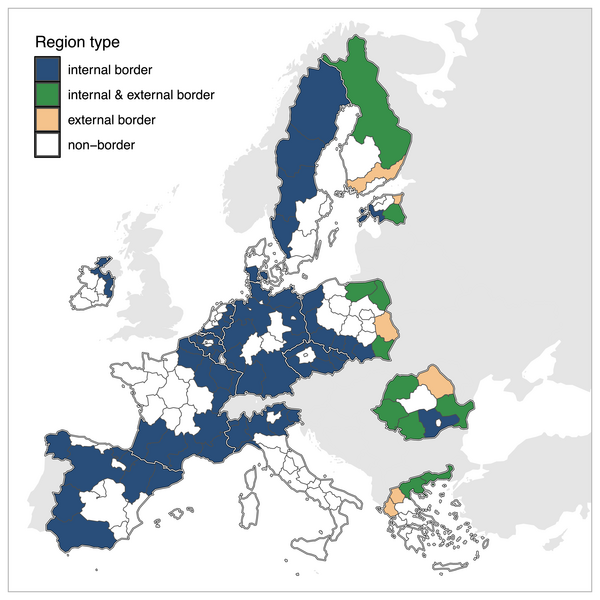

To illustrate the border and non‐border regions, Figures 1 and 2 map the regional border status at the regional granularity of the first and second part of the analysis in our sample of countries, respectively. Note that both maps provide a snapshot of the border status for the period after the accession to the EU of Croatia and before Brexit. In the analysis, we account for the temporal variation in countries' membership status during the period of observation such that there is also variation in border status over time for some regions – mostly as a result of EU enlargement.Footnote 14 While ideally, we would like to have fine‐grained NUTS‐3 data for both parts of the analysis, we want to stress that using a rougher geographic indicator makes our tests at the individual level more conservative. This is a result of the fact that NUTS‐2 border regions will typically include a higher share of respondents who do in fact not live very close to the border compared to NUTS‐3 border regions. Statistically speaking, picking up any result is, therefore, more difficult as these respondents should behave more like respondents from core regions, thereby biasing our estimator towards zero.

Figure 1. Map of border status for NUTS‐3 regions (2013–2020).

Figure 2. Map of border status for regions in Eurobarometer surveys.

For both parts of the analysis, an important concern is that the relationship between living in a border region and political attitudes towards the EU or their behaviour may be spurious. Recall that research on place‐based identities highlights two competing explanations for why place of residence could affect political attitudes. The first consists of contextual factors pertaining to unique characteristics of the place of residence that shape people's attitudes mainly through the daily experiences they have in their place of residence. The second is driven by compositional factors which mainly relate to self‐selection biases (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2019). Since we are particularly interested in the contextual effects of borders, we seek to isolate this effect from compositional factors. Luckily, the most critical compositional factors are observable and measurable. They mainly relate to individuals' level of education, socio‐economic background, age, left‐right ideology, gender and the like. We expect that controlling for the factors most critical to compositional effects, the largest variation left can be attributed to contextual factors related to the nature of the place of residence, in our case borderlands. Another crucial confounder relates to the centre–periphery cleavage (Lipset & Rokkan, Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967) because border regions are more likely to be periphery regions. To account for these factors, our empirical strategy is to match observable compositional variables and regions' status as centre or periphery in each part.

In the analysis of electoral results for Eurosceptic parties, we match border and non‐border regions on the basis of their logged gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, the square root of the unemployment rate,Footnote 15 the percentage of the population that is older than 65, the logged population density and a dummy of whether a region is a periphery region using coarsened exact matching.Footnote 16 We include an analysis of covariate balance in section A‐4 of the online Appendix. All but the last covariate were obtained from EUROSTAT and cover the most crucial compositional factors at the regional level, namely economic performance, age and degree of rurality. The dummy of periphery status is generated by first computing the distance between each region's centroid and the country's capital and then coding the 30 per cent most distant regions within each country as periphery regions.Footnote 17 Unfortunately, most EUROSTAT time series at the regional level are only available from 1999 onward. Consequently, we are unable to use earlier observations available in EU‐NED. While we view controlling for these factors to be paramount, we also replicate our main results with the unmatched original data set starting in 1987. The results of this robustness check are included in section A‐5 of the online Appendix and confirm the findings obtained from the main analysis, as shown below. We view this as evidence that our results are not driven by implicitly subsetting our data to a shorter time period. The dependent variable in this first part of the analysis is the regional vote share of Eurosceptic parties in national and European Parliament elections in percent. To arrive at this measure, we identify Eurosceptic parties following the coding scheme of the PopuList project (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019) and then obtain the regional vote share for these parties from the EU‐NED data, as previously mentioned. For the modelling, we use linear regression both with and without a number of covariates at the regional level using our matched data set.

We also rely on matching for the analysis of the Eurobarometer data using a number of individual‐level variables. More specifically, we match respondents living in border or core regions on age, their socio‐economic background in terms of social class, gender, marital status, left‐right ideology, whether they live in a rural or urban area and whether they live in a core or periphery region. The exact wording of the corresponding survey items can be found in section A‐3 of the online Appendix. Respondents' age is binned into five categories. For measuring their economic situation, respondents are asked to self‐report their social class which is measured on a five‐point scale ranging from 1 (working class of society) to 5 (higher class of society). For gender, we distinguish between male and female.Footnote 18 Marital status distinguishes between respondents who are married, single, divorced or widowed. Left‐right ideology is measured on a 10‐point scale ranging from 1 (left) to 10 (right). Respondents living in a rural area are coded as those who said they live in a rural area or village. Finally, we use the same coding of periphery regions from the first part of the analysis to identify respondents from the periphery in each country.

Given the large sample size and the fact that the matching variables are not truly continuously measured, we are able to follow an exact matching procedure instead of the coarsened exact matching procedure used in the first part. In so doing, we compare people who are identical with respect to these factors but vary in terms of whether they live in border regions or not. While we cannot rule out the presence of unobservables entirely, we believe that the largest share of the remaining variation in people's attitudes can be attributed to contextual factors. For this second matching procedure, we also include an analysis of covariate balance in section A‐4 of the online Appendix.

Using the data set of exactly matched survey respondents, we then study attitudes towards the EU and shed light on the mechanisms through which living in a border region drives these attitudes. Our two main dependent variables in this part consist of survey items gauging respondents' image of the EU (binary, 1 = positive) and trust in the EU (binary, 1 = tend to trust). While the survey item underlying the first dependent variable provides respondents with a five‐point scale ranging from 1 (very positive) to 5 (very negative), we turn it into a binary variable in our main analysis to ease the comparison with the second dependent variable for which respondents only had a binary choice. In particular, we code respondents who respond with 1 (very positive) or 2 (positive) as having a positive image of the EU. As we show in section A‐8 of the online Appendix, this binarization does not change our results in any meaningful way.

In order to explore the utility‐, identity‐ and institution‐based mechanisms through which living in a border region could influence these attitudes, we consider respondents' economic well‐being, their association of the EU with a loss of identity and their trust in the national parliament, respectively. The corresponding survey items ask respondents to indicate whether they have recently struggled to pay their bills at the end of the month, whether they believe that the EU means a loss of identity, and whether they tend to trust their national parliament. The exact wording of all the survey questions also can be found in section A‐3 of the online Appendix. While responses to the latter two are binary, respondents are given three options whether they struggle economically (1 = most of the time; 2 = from time to time; 3 = almost never/never). To make all variables comparable, we turn it into a binary variable by coding respondents as struggling economically if they responded with option one or two. We use these variables for our mechanisms in several binary logistic regression models where we also control for regional‐level per capita GDP and unemployment as well as gender, age and left‐right position. In a final step, we then conduct a mediation analysis by using these models to estimate the direct and mediated effect of living in a border region on EU support and trust for our three potential mechanisms.

Analysis and results

Regional Eurosceptic voting

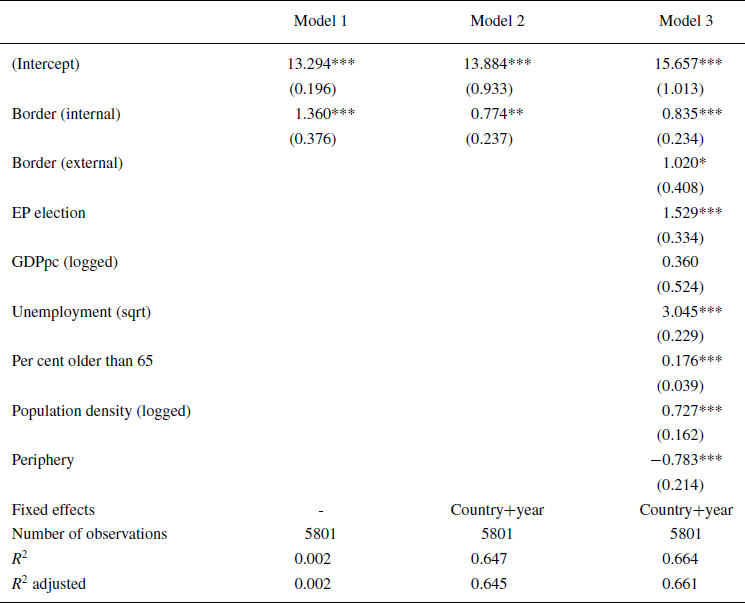

Do Eurosceptic parties fare better in border regions? Table 1 summarizes the analysis of these parties' vote shares using matching weights obtained from coarsened exact matching as described above. The first and second models only include the border treatment dummy without and with country and year fixed effects, respectively. The third model additionally controls for regions' external border status, the variables used for matching and another dummy separating national from European Parliament elections. Across all models, we find a consistently positive and statistically significant effect of regions' status as a border region on the vote share of Eurosceptic parties. Eurosceptic parties actually perform better in border constituencies. Since the dependent variable is measured in percentage points, the interpretation of the estimates is straightforward: In our matched data set, Eurosceptic parties receive about 13.29 per cent of votes cast in core regions. In border regions, on the other hand, these same parties receive about 1.36 percentage points more, resulting in an estimated 14.65 per cent of the total vote. While this may not sound like much, we would like to stress that this represents an increase of about 10 per cent relative to core regions (

![]() $14.65/13.29=1.10$). Consequently, we view this as a very substantial effect and strong evidence in support of our second hypothesis that borderlanders are more Eurosceptic compared to residents of core regions.

$14.65/13.29=1.10$). Consequently, we view this as a very substantial effect and strong evidence in support of our second hypothesis that borderlanders are more Eurosceptic compared to residents of core regions.

Table 1. Linear regression estimates using matching weights. Standard errors in parentheses.

![]() ${}^{\ast}$

p

${}^{\ast}$

p

![]() $<$ 0.05,

$<$ 0.05,

![]() ${}^{\ast \ast}$p

${}^{\ast \ast}$p

![]() $<$ 0.01,

$<$ 0.01,

![]() ${}^{\ast \ast \ast}$p

${}^{\ast \ast \ast}$p

![]() $<$ 0.001.

$<$ 0.001.

This main effect is also robust to the inclusion of country and year fixed effects as well as the additional inclusion of covariates. While the effect is somewhat smaller in magnitude, Eurosceptic parties still receive at least 0.77 percentage points more in border regions than in core regions. Recall that the matching procedure effectively removes a lot of observations available in EU‐NED due to data availability issues for regional‐level covariates. We, therefore, replicate these results for the full unmatched sample in section A‐5 of the online Appendix. The results of this exercise are very much in line with the ones shown here.Footnote 19

Since we do not match to estimate the effects of the additional covariates, we refrain from putting too much emphasis on the interpretation of their effects. Notwithstanding, the direction of these effects is mostly intuitive: Eurosceptic parties receive a higher share of the vote in external border regions, European Parliament elections, as well as in regions with high unemployment and an older population. Less intuitive is the positive effect for regions with a higher population density. Periphery regions, on the other hand, tend to be less Eurosceptic when accounting for all other covariates. Finally, the effect of GDP per capita is positive but fails to reach statistical significance.

Attitudes towards the EU

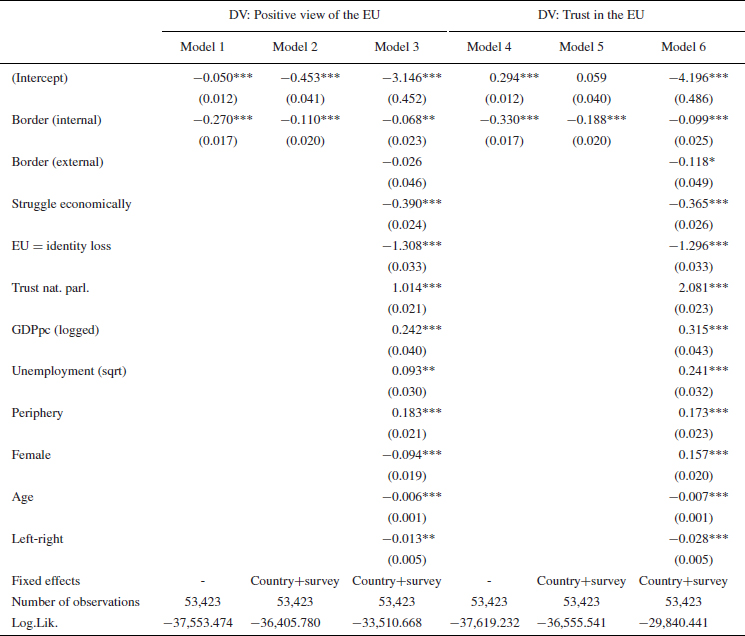

The analysis of election results above raises the question of what explains the more Eurosceptic behaviour of voters in border regions. In order to answer this question, we delve into the attitudes towards the EU with an analysis of survey data from the Eurobarometer. More specifically, we study respondents' views of and trust in the EU using our exactly matched data set. In particular, we seek to understand the mechanism through which living in a border region influences these attitudes. As we do not expect the effect of living in a border region to be a purely direct effect, we also consider how attitudes are shaped through the three mechanisms: utility‐, identity‐ and/or institution based. Table 2 summarizes the results of several binary logistic regression models. Models one through three have as the dependent variable a positive image of the EU while models four through six focus on respondents' trust in the EU. For each dependent variable, we include one model with just the internal border indicator, one for which we add country and survey fixed effects and a last model that includes the three potential mediators as well as additional controls for regional GDP per capita, regional unemployment, regional periphery status, gender, age and left‐right ideology.

Table 2. Binary logistic regression estimates using matching weights. Standard errors in parentheses.

![]() ${}^{\ast}$

p

${}^{\ast}$

p

![]() $<$ 0.05,

$<$ 0.05,

![]() ${}^{\ast \ast}$p

${}^{\ast \ast}$p

![]() $<$ 0.01,

$<$ 0.01,

![]() ${}^{\ast \ast \ast}$p

${}^{\ast \ast \ast}$p

![]() $<$ 0.001.

$<$ 0.001.

Across all dependent variables and models, we find consistently negative effects: Respondents living in border regions are less likely to respond that they view the EU positively or that they trust it.Footnote 20 All coefficient estimates are statistically significant, and the effects are quite substantial in magnitude. To illustrate, we estimate the average marginal effects of living in a border region. Using the base models one and four, we find that respondents in border regions are about 6.7 per cent less likely to indicate that they have a positive image of the EU and about 8.2 per cent less likely to say that they trust the EU. However, the inclusion of country and survey fixed effects as well as the covariates in models three and six significantly reduces the magnitude of these effects. This yields the interpretation that while respondents living in border regions are clearly more Eurosceptic than those from core regions, a substantial share of this effect can be explained by these additional covariates. We thus focus our attention on exploring these potential mechanisms and their relative importance below.

Clearly, models three and six show that the variables measuring the potential mechanisms through which people living in border regions may be more Eurosceptic are highly predictive of respondents attitudes towards the EU. Moreover, the direction of their effects is in line with general expectations: Respondents who struggle to pay their bills by the end of the month, to which the EU means a loss of identity or who have low trust in their national parliament have a much more negative view of the EU and trust it less. We argue that living in a border region has potentially indirect effects that function through these mechanisms.

To disentangle the direct and indirect effects, we conduct a mediation analysis on the basis of models three and six. Of course, a causal mediation analysis would require us to causally identify each effect in a mediation triangle, that is, the effects of living in a border region on both EU attitudes and each of the mechanisms as well as the effects of each mechanism on EU attitudes. Notwithstanding, although we cannot make any causal claims about this part of the analysis, the mediation analysis still helps understand the mechanism through which living in a border region shapes attitudes towards the EU with a correlational approach.

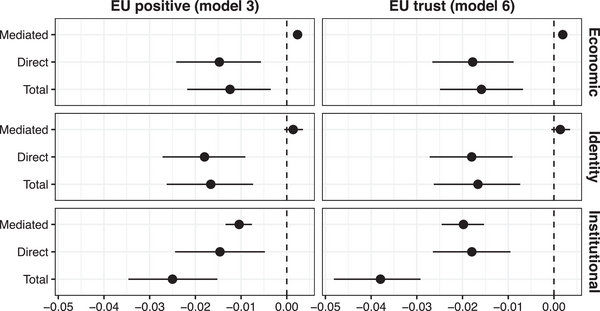

In Figure 3, we present these results for both dependent variables across columns and the three potential mechanisms across rows. As in previous steps of the analysis, there is little difference between the dependent variables, which provides additional reassurance that our findings are not specific to one outcome.

Figure 3. Mediated, direct and total effects for utility‐, identity‐ and institution‐based mechanisms. Horizontal lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Comparing the different mechanisms, what becomes immediately clear is that the mediated effects of the three mechanisms differ substantially. More specifically, we find a small positive but statistically significant mediated effect for the economic/utilitarian explanation, a null finding for the identity‐based mechanism and a much larger negative effect for the institutional mechanism which is statistically significant. While this gives some credence to the utilitarian explanation of more pro‐EU borderlanders, it also shows that its effect is all but negligible in comparison to the negative mediated effect of the institutional mechanism. What this means is that respondents from border regions tend to have lower trust in their national parliament and in turn a more negative image of the EU as well as lower trust in the EU. In terms of relative magnitude compared to the direct effect, the mediation explains about half of the total negative effect. This share is slightly higher in model six, which is likely due to the fact that both items relate to trust and are asked in the same battery of questions in the survey. However, it also holds for model three. The positive mediated effects of the economic and identity mechanism, on the other hand, are too small to meaningfully impact the overall negative effect of living in border regions.

In summary, we view this as strong evidence that the institutional mechanism plays a vital role in explaining our central finding that inhabitants of border regions are more Eurosceptic. At the same time, the mediation analysis demonstrates that this is only part of the explanation. The remaining negative direct effect leaves room for additional explanations of what drives Eurosceptic attitudes and behaviour in EU border regions. In the final discussion below, we propose further factors to be considered in future research.

Robustness checks

To ensure the robustness of our findings, we have conducted a series of checks addressing a range of empirical concerns. Detailed discussions of these additional analyses can be found in the online Appendix. First, we investigate whether our findings are robust to country‐ and time‐specific intricacies, and this analysis ensures that the findings we uncover are neither driven by peculiar cases nor inconsistent over time. Second, because matching results in some loss of observations, we re‐estimated all of our models with the full unmatched samples to ensure that the results we find also hold when using a fixed‐effects regression design. Third, since we rescale the outcome variable expressing the positive image of the EU from a five‐point scale to a dummy variable, we have estimated our results with the original scale. Fourth, to ensure that the results we uncover are not specific to exact matching, we re‐estimated our models using an alternative matching method, specifically nearest neighbour matching. Lastly, because mediation analysis can be challenging to interpret, we have undertaken an alternative modelling strategy to ensure that the institutional mechanism we uncover holds in a different empirical setup. Taken together, these robustness checks reveal that our results are robust to different modelling decisions, variable scales and empirical approaches.Footnote 21

Alternative explanations

Finally, we have conducted several empirical analyses to test the effect of borders we uncover against several alternative factors and explanations. First, a critical reader might argue the effect of borders we uncover is simply a reflection of the classical centre–periphery cleavage, whereby border regions are also more likely to share the characteristics of a political periphery. To test against this explanation, sections A‐7 and A‐10 of the online Appendix include iterations of our analysis where we excluded the capital regions of the countries included in our sample. Furthermore, our primary analysis matches on periphery status as we explain in the empirical section. Taken together, the findings from these two procedures confirm that the core–border differences we find are distinct from a centre–periphery cleavage.

Second, it might be the case that differences at the borders, for example, in terms of economic prosperity, account for the negative effect we uncover for borders, especially if our sample over‐represents advantaged border regions. To warrant against this factor, we have calculated economic differences in terms of GDP per capita and controlled for this factor in section A‐12 of the online Appendix. While boundary gaps have their independent effect, we find their effect neither consistent nor capable of substituting or undermining the effect of borders which our analysis revealed. In other words, we find that internal borders have a negative influence, regardless of any cross‐border differences in economic prosperity.

Third, while we posited two alternative hypotheses whereby residing in border regions either has positive or negative effects, an alternative explanation holds that borders might exert both effects simultaneously on different voters, leading to a polarization effect which our general hypotheses do not uncover. To investigate this possibility empirically, section A‐15 of the online Appendix includes an additional analysis where we interact the border dummy with a score of individual‐level characteristics, reflecting the winners versus losers of the globalization dynamics (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012). This analysis does not provide any strong evidence for such polarization effects.

Lastly, because we rely in our analysis on recent waves of the Eurobarometer, particularly the waves collected after COVID‐19, a critical reader might wonder if the negative effect we find is a result of the negative experiences of COVID‐fencing that European border regions have gone through. To ensure that the border effect is not specific to the COVID‐19 pandemic, we re‐estimate our models for the pre‐COVID waves separately in section A‐9 of the online Appendix and we obtain very similar findings. However, the effects are slightly less strong, suggesting that the pandemic may have exacerbated the difference between border and core regions. At the same time, the fact that our analysis of the EU‐NED extends to 2000 (and indeed to 1990 in our additional analysis in section A‐5 of the online Appendix) largely eliminates the concern that our findings only hold in a narrow time period.

Discussion and conclusion

European border regions are uniquely characterized by living the consequences of European integration in everyday experiences. In this paper, we have synthesized research on EU support, place‐based identities and border studies to argue that borderlands play a significant role in shaping the perceptions of the people residing within them. While past empirical findings demonstrated that borders exert a positive effect on their inhabitants' attitudes towards the EU, our contention in this paper has been more nuanced. We maintained that the effect of borders is intricate, multidimensional and potentially two‐sided. We theorized that although borderlands' everyday experiences could lead to more positive attitudes towards the EU, they still encounter economic, political, cultural and institutional developments that might impact the attitudes of their residents rather negatively.

Indeed, our empirical analysis provides remarkable and novel results. Using statistical matching, we find evidence that borderland inhabitants are more inclined to support Eurosceptic parties and hold negative attitudes towards the EU. We depart from past literature by employing more rigorous statistical methods and investigating both behavioural and attitudinal data to draw a more holistic picture of Euroscepticism in borderlands. Furthermore, our mediation analysis points to intriguing findings. While we find a small positive effect for the economic mechanism in line with past research (Gabel & Palmer, Reference Gabel and Palmer1995), our analysis reveals a much stronger negative impact of our institutional mechanism. Residents of border regions hold low trust in their national political institutions, which translates to more negative attitudes towards the EU.

Our findings square nicely with the extrapolation mechanism (Anderson & Reichert, Reference Anderson and Reichert1995; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Meer and Vries2013) and recent findings showing that trust in national political institutions is an antecedent to trust in the EU (Lipps & Schraff, Reference Lipps and Schraff2021). Nonetheless, our results refer to a novel theoretical twist, whereby political elites residing in the capital, rather than people on the other side of the border, might be one reason why borderland residents are more sceptical of the EU. By highlighting this institutional mechanism, we wish to contribute to past literature employing economic and cultural mechanisms. Lastly, although we could not investigate our political mechanism, pertaining to party rhetoric in borderlands, we believe that trust in political institutions captures some of the political consequences of this rhetoric. It remains open for future research to investigate whether party rhetoric exerts distinctive effects in border regions compared to core regions.

Our study speaks and contributes to at least three bodies of literature. First, we contribute to the literature on public support for European integration. As mentioned, this literature mainly considers economic, cultural or cue‐taking and bench‐marking explanations, whereas attention to the role of geography has been scant. Second, we speak to the literature on place‐based identities and politics. This literature has been focusing mainly, if not exclusively, on urban–rural divides, whereas the role of other geographical lines of division has been ambiguous. More generally, our study also addresses larger studies of political geography and anthropology concerned with the nature and attitudes of border regions and their inhabitants by illuminating how borders can shape sentiments towards supranational systems of governance.

One limitation of our study pertains to the lack of fine‐grained data on public attitudes. Although the first part of our analysis employs NUTS‐3 regional units, which is the most fine‐grained administrative level in the EU, the Eurobarometer is only available at the NUTS‐2 level, which is not fine‐grained enough to distinguish very clearly between border and core regions. Nonetheless, while we can only speculate as to how this affects our findings, we are convinced that this lack of fine‐grained data makes our statistical investigation highly conservative. Since we hypothesize about meaningful differences between residents of border and core regions, combining them in larger NUTS‐2 geographical units most likely underestimates the effect of residing in border regions, assuming that they are distinct as our voting data unambiguously demonstrate. Therefore, our expectation is that with more fine‐grained data, our effects should be larger in magnitude.

Another potential issue with this lack of granularity is the fact that our analysis may pick up on more general trends and patterns in some countries. In Sweden, for instance, border regions cover the large and contiguous northern part of the country. Idiosyncrasies of such regions may have a bearing on the effects we find for border regions in general. Notwithstanding, while we cannot fully rule out the issues of unobservables and self‐selection, our matching design mitigates this risk by taking into account that such areas and their inhabitants also typically differ on the socio‐demographic, economic and geographical variables that we match on.

It is also possible that the effect of borders varies with several factors, such as the historical legacies between different regions and the economic, political and cultural disparities on both sides of the borders –what is known as ‘boundary gaps’ (Rippl et al., Reference Rippl, Bücker, Petrat and Boehnke2010; Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2021). Nonetheless, we have taken steps to test the boundary gap effect, and we find that differences at the borders cannot substitute or undermine the effect we uncover for borders. For more details, we refer the reader to section A‐12 in the online Appendix. Furthermore, our goal in this paper was to tackle the question of whether and why borders matter. Future research could investigate more closely the question of which borders matter, and under what conditions, possibly employing more fine‐grained data on attitudes than the data we possess.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Frank Schimmelfennig, Dominik Schraff, Sven Hegewald, the participants of the 2022 summer retreat of the European Politics Group and students in the Spring 2023 course Comparative and EU Politics at ETH Zurich for their invaluable feedback on earlier versions of this paper. We also extend our gratitude to three anonymous reviewers for their excellent comments. This research was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 programme (ERC‐AdG EUROBORD, grant agreement 101018300).

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A‐1: Country selection for each part of the analysis.

Table A‐2: Number of border and core regions across countries in matched EU‐NED sample.

Table A‐3: Timeline of major border changes.

Table A‐4: Eurobarometer survey questions and responses.

Figure A‐1: Covariate balance for EU‐NED election data.

Figure A‐2: Covariate balance for Eurobarometer survey data.

Table A‐5: Linear regression estimates.

Table A‐6: Linear regression estimates using matching weights.

Table A‐7: Linear regression estimates using matching weights.

Table A‐8: Linear regression results using matching weights.

Table A‐9: Binary logistic regression estimates.

Table A‐10: Binary logistic regression estimates.

Table A‐11: Binary logistic regression estimates.

Table A‐12: Binary logistic regression estimates.

Figure A‐3: Border effects across countries.

Figure A‐4: Border effects across time periods.

Table A‐13: Interacting internal borders with individual characteristics.

Table A‐14: Linear regression estimates.

Data S1