Introduction

In an era of globalization and digital interconnectivity, increasingly integrated labor markets have intensified global competition for skilled talent, particularly across countries in the Global North. In developed nations such as Canada, this competition is further shaped by aging populations, labor shortages, and the strategic role of skilled immigrants in driving innovation, sustaining economic growth, and competing in the knowledge-based global economy. Yet, a decolonial analysis raises a critical question: what counts as “skill,” and who gets to define it? Scholars such as Iskander (Reference Iskander2021) argue that dominant skill hierarchies are not neutral but historically rooted in colonial logics that privilege Western forms of knowledge, technical expertise, and credentialed professionalism while devaluing relational, embodied, or community-based competencies common in the Global South (Karki Reference Karki2016). This critique is directly relevant to Canada’s immigration regime, which valorizes “skilled labor” at the selection stage but often subjects immigrants to epistemic injustice upon arrival through credential devaluation and the erasure of non-Western forms of expertise. Interrogating the colonial construction of skill, therefore, deepens the analysis of labor market exclusion and reinforces the central argument of this study: integration is not merely about economic participation, but about whose knowledge and labor are recognized as legitimate within national economies.

Canada’s immigration system is structured around three primary categories of permanent residency: (a) the Family Class, which facilitates the reunification of close relatives; (b) the Economic Class, which includes skilled professionals and entrepreneurs; and (c) the Refugee and Humanitarian Class, which offers protection to individuals fleeing persecution, war, or human rights violations. These categories emerged following the introduction of the Points System in 1967, a pivotal reform that redefined Canadian immigration policy. The system replaced earlier country-of-origin preferences that had favored European and U.S. immigrants with a merit-based assessment of human capital factors such as education, work experience, language proficiency, and age (Bauder Reference Bauder2003; Coustere et al. Reference Coustere, Brunner, Shokirova, Karki and Valizadeh2024; Satzewich Reference Satzewich2015). This policy transformation opened Canada’s doors to migrants from the Global South, including Asia, Africa, and Latin America, thus reshaping the country’s demographic composition.

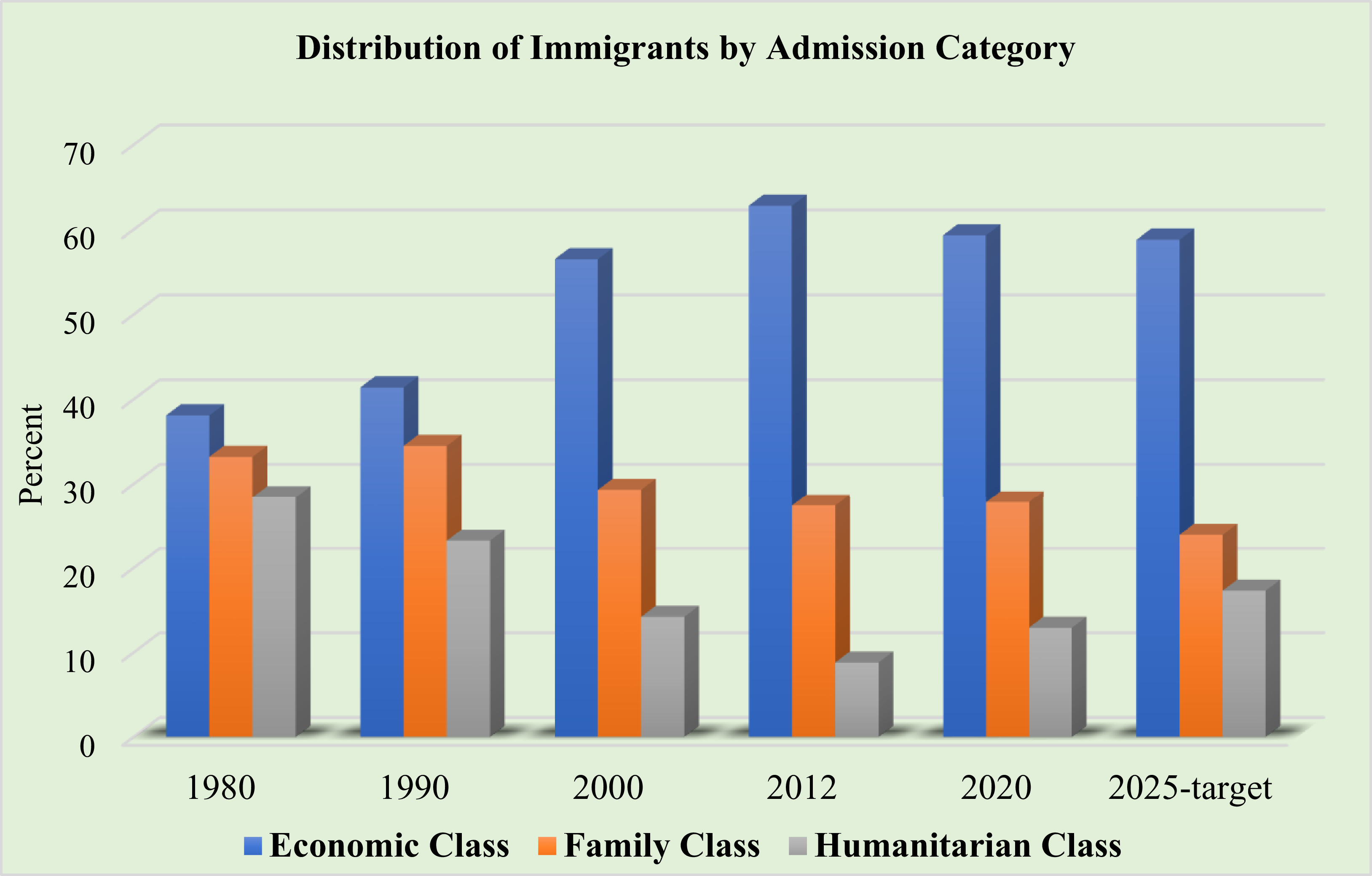

Among the three categories, Canada has increasingly prioritized the Economic Class, emphasizing immigrants’ potential contributions through their skills and educational attainment (Brunner et al. Reference Brunner, Karki, Valizadeh, Shokirova and Coustere2024). This orientation reflects a broader policy logic that positions immigration as a demographic tool and an economic strategy to mitigate labor shortages and bolster global competitiveness (Karki Reference Karki2020, Reference Karki2025). Over time, the balance among immigration objectives has shifted considerably. In 1980, economic class immigrants accounted for 38.1% of total admissions, compared to 33.2% for family class and 28.4% for protected persons. By 2020, these proportions had changed to 59.3%, 27.8%, and 12.9%, respectively (Statistics Canada 2024), illustrating a pronounced shift toward a market-oriented immigration model in which human capital and labor market integration take precedence over social and humanitarian goals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of immigrants by admission category

Source: (Karki, Reference Karki2025; Statistics Canada, 2024).

Today, immigration is the primary driving force of Canada’s population growth. Statistics Canada (2024) reports that international migration, including permanent and temporary immigration, accounted for 92% of population growth in the third quarter of 2024. Between 2023 and 2024, Canada’s population grew by nearly 3%, primarily due to international migration, a rate surpassing that of most OECD countries. In 2024 alone, 464,000 new permanent residents were admitted, nearly achieving the planned target of 485,000 (Statistics Canada 2025a). By 2033, immigration is projected to become the sole source of population growth, as the natural increase (births minus deaths) turns negative (The Conference Board of Canada 2024). This projection indicates Canada’s reliance on immigration, not merely as a policy preference, but as a demographic necessity. However, high admission levels do not automatically ensure equitable labor market outcomes. Although programs such as the Federal Skilled Worker Program (FSWP) attract highly qualified individuals, many skilled immigrants continue to face underemployment and deskilling (Karki and Moasun Reference Karki and Moasun2023a, Reference Karki and Moasun2023b; Reitz Reference Reitz2001; Reitz, Curtis, and Elrick Reference Reitz, Curtis and Elrick2014). These phenomena—where highly educated and professionally trained individuals cannot secure employment commensurate with their qualifications—undermine both immigrants’ career aspirations and Canada’s capacity to fully utilize their talents.

The FSWP, a subcategory of the Federal High Skilled stream within Canada’s economic immigration pathway, is designed to attract skilled professionals who can contribute to the national economy. The potential applicants are assessed through a triangulated points-based system that considers skilled work experience, language proficiency in English and/or French, and educational attainment, with credentials evaluated by designated agencies for Canadian equivalency (Government of Canada 2022). While this system suggests a meritocratic approach that recognizes transferable expertise, empirical realities often diverge from policy expectations. Skilled immigrants arriving through the FSWP frequently encounter barriers to upward occupational mobility, as labor market outcomes remain mediated by race, gender, class, location, and age (Gyan et al. Reference Gyan, Lafreniere, Diallo, Wilson-Forsberg, Karki and Hinkkala2024). These structural constraints shape not only access to employment but also the recognition of professional identity, which depends on both self-identification and external validation (Korzeniewska and Erdal Reference Korzeniewska and Bivand Erdal2021). For instance, skilled migrant women are often overlooked in professional contexts and instead positioned within global reproductive or caregiving labor, despite possessing broader expertise (Kofman and Raghuram Reference Kofman and Raghuram2006). Such patterns reveal a critical paradox: although the FSWP recruits highly educated individuals based on their perceived economic value, systemic bias and occupational segregation frequently obstruct their professional advancement. As a result, the program may inadvertently reproduce existing inequalities in the labor market rather than promote equitable integration, illustrating a key gap between immigration policy intent and labor market practice.

Empirical evidence consistently shows that skilled immigrants experience lower employment integration than their Canadian-born counterparts, even when they possess comparable credentials (Raihan, Chowdhury, and Turin Reference Raihan, Chowdhury and Turin2023). Statistics Canada (2020) found that overqualification among university degree holders was significantly higher for immigrants (10%) than for non-immigrants (4%) in both 2006 and 2016. These disparities are particularly acute for racialized immigrants, who encounter systemic and institutional barriers (Karki Reference Karki2025, Reference Karki2026) and face what Block and Galabuzi (Reference Block and Galabuzi2018) describe as a “color code” limiting access to professional opportunities. However, it is important to note that comparing immigrants solely to non-racialized Canadian-born workers may obscure the differentiated effects of race and migration status. Recent wage analyses that include racialized Canadian-born workers reveal that both racial and migrant penalties operate simultaneously, but not uniformly. For instance, while racialized immigrants earned an average of 82 cents for every dollar earned by non-racialized Canadian-born workers, racialized Canadian-born workers also experienced wage suppression at approximately 90 cents on the dollar, suggesting a compounded disadvantage for racialized migrants (Block, Galabuzi-Grace, and Tranjan Reference Block, Galabuzi-Grace and Tranjan2019). This layered inequality underscores the racialized structure of labor markets while also highlighting how migration status interacts with race to intensify credential devaluation and income precarity. Moreover, those trained in regulated professions—such as health care, law, or engineering—often face restrictive credential recognition processes and subtle forms of discrimination that divert them into lower-skilled occupations (Chowdhury, Lake, and Turin Reference Chowdhury, Lake and Turin2023).

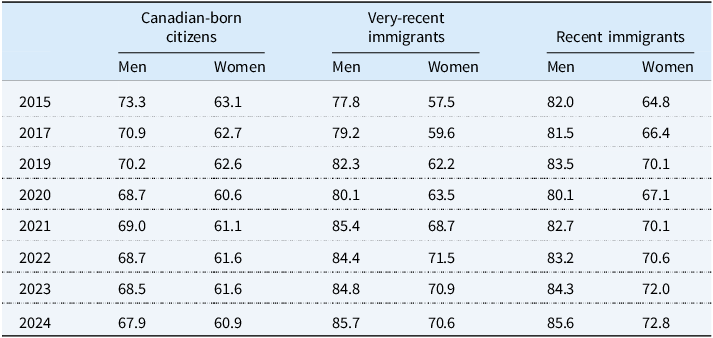

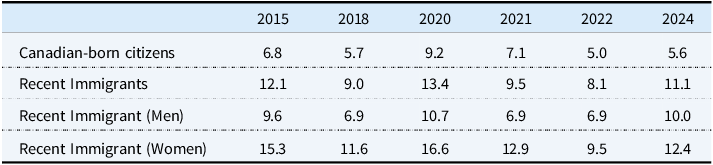

Labor force participation and unemployment data further support this paradox (see Tables 1 and 2). Between 2015 and 2024, very recent immigrants (those residing in Canada for five years or less) and recent immigrants (five to ten years) consistently demonstrated higher workforce participation than Canadian-born citizens. For example, labor force participation among recent immigrant men rose from 82.0% in 2015 to 85.6% in 2024, while participation among Canadian-born men declined from 73.3% to 67.9% (Statistics Canada 2025b). Yet, despite higher levels of participation, immigrants continued to face disproportionately high unemployment rates. These disparities must be interpreted with caution, however, given that very recent immigrants may be subject to immigration conditions—such as temporary work visa requirements or proof of economic self-sufficiency—that incentivize immediate labor market entry. Age composition also plays a role: immigrants are, on average, younger than Canadian-born workers, which may inflate participation rates while masking gaps in job quality and stability. Notably, recent immigrant women face a double disadvantage: in 2024, their labor force participation was 72.8%, lower than that of recent immigrant men (85.6%), yet their unemployment rate was significantly higher at 12.4% compared to 10% for men. These patterns highlight the need to disentangle participation from meaningful inclusion and to analyze labor force statistics in relation to immigration status, gender, race, and life stage.

Table 1. Labor force participation rates of Canadian-born and immigrants (2015–2024)

Source: Statistics Canada, 2025b

Table 2. Unemployment rates of Canadian-born and recent immigrants (20215–2024)

Source: Statistics Canada, 2025b

The above statistical figures reveal that participation alone does not guarantee meaningful or equitable employment commensurate with immigrants’ skills and qualifications. Structural barriers such as credential devaluation, limited professional networks, and systemic racism continue to shape labor market outcomes (Block, Galabuzi-Grace, and Tranjan Reference Block, Galabuzi-Grace and Tranjan2019; Karki et al. Reference Karki, KC, Giwa, Mullings and Raible2023; Oreopoulos Reference Oreopoulos2011). Consequently, the stratification of the labor market along lines of origin, race, and gender exposes contradictions between immigration policy goals and economic realities. From a social work and integration policy perspective, such disparities carry far-reaching implications. Employment integration is central to immigrants’ socio-economic well-being and to the broader success of Canada’s immigration system. The persistent underutilization of skilled immigrants thus reflects not individual deficits but structural and institutional inequities that disproportionately affect racialized newcomers.

Given these tensions, there is a pressing need for a coordinated and systemic approach to understanding how such inequities arise and persist. This study responds to that need by exploring the lived experiences of skilled, racialized immigrants navigating the Canadian labor market, specifically how systemic barriers shape their professional trajectories and the adaptive strategies they employ. Drawing on critical migration theory, intersectionality, and decolonial social work perspectives, the study investigates how race, skill, and professional identity intersect within broader structures of power. The central research question guiding this inquiry is: How do systemic barriers in British Columbia’s labor market shape the professional trajectories and deskilling experiences of skilled, racialized immigrants, and how do they navigate these challenges? This research contributes to migration and social work scholarship in three key ways. First, it empirically documents the structural barriers that skilled, racialized immigrants face in Canada’s labor market. Second, it advances theoretical understanding of how migration regimes, intersectional inequalities, and colonial epistemologies influence labor market integration. Third, it offers policy and practice insights for developing decolonial and anti-oppressive strategies that promote equitable professional inclusion.

An Integrative Theoretical Framework

This study is guided by an integrated theoretical framework combining critical migration theory (Anderson Reference Anderson2013; De Haas et al. Reference Haas, Hein, Flahaux, Mahendra, Natter, Vezzoli and Villares-Varela2019; Mezzadra and Neilson Reference Mezzadra and Neilson2020), intersectionality (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Hill Collins Reference Collins2019), and decolonial social work perspectives (Dominelli Reference Dominelli2002; Hetherington et al. Reference Hetherington, Gray, Coates and Yello Bird2016; Mignolo and Walsh Reference Mignolo and Walsh2018) to interrogate how structures of power shape skilled immigrants’ exclusion in the Canadian labor market. The framework elucidates the entanglement of global hierarchies, racialized and gendered stratifications, and colonial epistemologies that simultaneously celebrate and devalue “skilled” migrants.

Critical Migration Theory

Critical migration theory (CMT) reorients understandings of migration away from individual decision-making and towards the political economy of mobility, emphasizing the ways migration is shaped by capitalist interests, racialized logics, and state regulation (Anderson, Sharma, and Wright Reference Anderson, Sharma and Wright2011). Rather than a neutral or humanitarian process, migration is viewed as a socially constructed and politically managed mechanism that secures labor for national economies while reinforcing global hierarchies. De Haas et al. (Reference Haas, Hein, Flahaux, Mahendra, Natter, Vezzoli and Villares-Varela2019) argue that migration functions as a mode of social ordering that organizes people into differentiated categories of belonging, legality, and employability. Complementing this perspective, Mezzadra and Neilson (Reference Mezzadra and Neilson2020) conceptualize migration governance as a system of social bordering—one that constructs inclusion and exclusion through both formal policy and everyday institutional practices. Borders, in this view, are not merely territorial lines but social techniques for producing stratified labor markets.

Canada’s points-based immigration system illustrates these contradictions clearly. On the surface, it appears meritocratic, rewarding education, work experience, and language proficiency. Yet, in practice, it operates as a technology of labor governance that commodifies global talent while preserving national hierarchies (Bauder Reference Bauder2015; De Haas et al. Reference Haas, Hein, Flahaux, Mahendra, Natter, Vezzoli and Villares-Varela2019). Immigrants’ qualifications become strategic assets during the selection phase, yet are frequently devalued upon arrival through credential recognition regimes, deskilling processes, and racialized assessments of employability. This contradiction reflects what (Sharma Reference Sharma2006) terms flexible inclusion: migrants are incorporated into the labor market as workers but are withheld recognition as professionals or full members of the national community.

These dynamics reveal that migration policy operates less as a mechanism of equitable integration and more as an instrument of labor governance that channels migrants into stratified occupational niches. Far from simply facilitating settlement, the system actively delineates who counts as “Canadian skilled labor” and the terms under which they may participate. Immigrants, therefore, do not merely enter a labor market; they are positioned within a hierarchy of labor shaped by intersecting regimes of race, skill, language, and legality. Viewed through the lens of critical migration theory, these practices render visible the structured production of precarity and the institutional reproduction of inequality within migration regimes that are publicly framed as inclusive and meritocratic.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality deepens critical migration theory by illuminating how race, gender, class, and migration status intersect to structure exclusion within labor markets and institutional arrangements. Rather than treating disadvantage as an additive phenomenon, intersectionality analyses exclusion as relational, emerging through interlocking systems of domination that configure power across multiple axes of identity (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989, Reference Crenshaw1991; Hill Collins Reference Collins2019). From this perspective, migrants do not simply face isolated barriers; they encounter structured inequalities embedded in the everyday norms that shape employability and professional legitimacy. These dynamics are particularly evident in the ways professional competence is evaluated through standards implicitly aligned with whiteness, middle-class cultural capital, and Western career trajectories. Research demonstrates that racialized immigrants, particularly women, face intensified barriers to recognition and advancement despite holding equivalent or even superior credentials (Creese and Wiebe Reference Creese and Wiebe2012; Karki Reference Karki2025).

A key example is the persistent demand for “Canadian experience,” which functions as a proxy for cultural proximity and racial belonging. Presented as neutral, this requirement reifies professional norms that advantage dominant groups; it is less a measure of skill than a mechanism for privileging those already positioned within normative frameworks of belonging. Such expectations exemplify what Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2012) calls institutional habits: racialized norms that become naturalized as objective criteria of fit or professionalism. The demand for “Canadian experience,” therefore, does not merely reflect local labor market preferences; it operates as a mechanism of racialized boundary-making that delineates who counts as a legitimate professional. These dynamics are further entrenched through credential recognition regimes, such as the Foreign Credential Recognition Program, which often subject highly trained immigrants to costly, opaque, and prolonged assessment processes. In this sense, credential recognition constitutes a form of epistemic gatekeeping (i.e., whose knowledge counts and whose is rendered suspect), in which professional legitimacy is not merely assessed but actively constructed.

Through an intersectional lens, these barriers emerge not as isolated regulatory issues but as manifestations of broader systems of racialized labor stratification. Intersectionality, therefore, renders visible the logics through which the Canadian labor market privileges particular embodiments of skill, experience, and cultural familiarity while systematically devaluing others (Block, Galabuzi-Grace, and Tranjan Reference Block, Galabuzi-Grace and Tranjan2019). It exposes how “professionalism” itself becomes a boundary-making practice—one that upholds national hierarchies of belonging and labor worthiness.

Decolonial Social Work

A decolonial social work lens extends this critique to the epistemic domain, interrogating how Western institutions define legitimate knowledge, expertise, and professional worth (Mullings et al. Reference Mullings, Power, Giwa, Karki, Burt, Caines, English-Lillos, McLean and Ricketts2022). Epistemic violence—manifested in the erasure of Global South knowledges—pervades credential recognition and settlement systems (Guo Reference Guo2015; Mignolo and Walsh Reference Mignolo and Walsh2018). Decolonial scholarship challenges these assimilationist logics by advancing epistemic justice: recognition of plural knowledges, multiple standards of competence, and relational dignity. Scholars such as Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Green, Gilbert and Bessarab2013), Dominelli (Reference Dominelli2002), and Hetherington et al. (Reference Hetherington, Gray, Coates and Yello Bird2016) contend that mainstream social work, though framed as universal and humanitarian, reproduces Western epistemic dominance that marginalizes non-Western worldviews through education, policy, and practice. Razack and Jeffery (Reference Razack and Jeffery2002) and Walter, Taylor, and Habibis (Reference Walter, Taylor and Habibis2011) call for dismantling whiteness and institutional privilege embedded within professional structures, while Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Green, Gilbert and Bessarab2013) and Prehn and Walter (Reference Prehn and Walter2023) propose decolonial frameworks grounded in Indigenous sovereignty, land-based ethics, and relational accountability. Decolonial social work thus reframes the profession ethically, demanding transformation rather than adaptation through the redistribution of epistemic and institutional power toward plural, equitable, and self-determining forms of practice.

The integrative framework, therefore, offers a robust lens for interpreting empirical evidence on deskilling, precarious employment, and downward occupational mobility among skilled, racialized immigrants in the Canadian labor market. Precarious employment is characterized by unstable contracts, limited protections, and constrained opportunities for advancement, often leaving workers vulnerable to both economic insecurity and social marginalization (Karki et al. Reference Karki, Chi, Gokani, Grosset, Vasic and Kuwee Kumsa2018). CMT explains how migrants are recruited through an ostensibly meritocratic system but subsequently positioned within stratified labor hierarchies that commodify their skills while withholding full professional legitimacy. Intersectionality deepens this analysis by demonstrating that these exclusions are not evenly distributed; rather, they are patterned through interlocking relations of race, gender, class, and migration status—illuminating why women and racialized migrants disproportionately encounter devaluation despite holding equivalent credentials. A decolonial social work lens further extends these insights by revealing how institutional practices reproduce epistemic hierarchies that privilege Western norms of expertise and systematically discount Global South knowledge systems, shaping both credential recognition and workplace inclusion. These perspectives help explain not only what forms of exclusion occur but also how they are reproduced through policy, professional standards, and the everyday logics of employability.

Methodology

Research Design and Context

This study employed a qualitative research design (Yegidis, Weinbach, and Myers Reference Yegidis, Weinbach and Myers2018) to examine how systemic barriers in British Columbia’s labor market shape the professional trajectories and deskilling experiences of skilled, racialized immigrants, as well as the strategies they employ to navigate these challenges. The research was situated in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, a region renowned for its ethnocultural diversity and economic vitality. With a population of approximately three million, representing about 61% of the province’s total population, the region provides a particularly relevant context for exploring immigrant labor market integration (Trade and Invest British Columbia 2024). According to TransMountain Corporation (2022), the Lower Mainland labor force numbered roughly 1.8 million, with a participation rate of 67.2% and an unemployment rate of 5.1%. These demographic and economic characteristics highlight the area’s importance as a focal site for understanding the intersections of race, skill, and employment integration.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (Protocol No: 101494). All participants provided informed written consent prior to participation. Ethical safeguards guided every stage of the study, ensuring that participants’ autonomy, confidentiality, and dignity were upheld throughout the research process.

Participants and Sampling

Participants were skilled immigrants who self-identified as racialized. To be eligible, individuals were required to (1) have immigrated under the Federal Skilled Worker (FSW) program; (2) be the principal applicant under this program; (3) have applied for permanent residency through a Canadian mission abroad; (4) currently reside in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia; and (5) self-identify as belonging to a visible minority group, as defined by the Government of Canada. To ensure clarity in the scope of the study, immigrants who had initially entered Canada through other immigration categories, such as international student permits, temporary work visas, or business visas, and later transitioned to permanent residency, were excluded. This exclusion recognized that such individuals often accumulate settlement experiences that may shape professional integration differently from those who migrated directly as skilled workers.

A combination of criterion-based and convenience sampling strategies guided participant recruitment. This dual approach ensured that participants met the study’s inclusion criteria while also accommodating practical factors such as availability and willingness to participate (Yegidis, Weinbach, and Myers Reference Yegidis, Weinbach and Myers2018). Efforts were made to achieve gender balance and diversity within the sample, acknowledging that experiences of deskilling and labor market navigation are influenced by intersecting social identities, including gender. Such attention to intersectional representation strengthened the study’s capacity to capture a broad spectrum of perspectives within the racialized skilled immigrant population.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Participants were recruited in collaboration with local community organizations, including settlement agencies, cultural associations, religious institutions, and ethnic community networks. The researcher (principal investigator) contacted organizational representatives who circulated recruitment flyers to potential participants within their networks. Partnering with these trusted intermediaries fostered credibility and facilitated access to potential participants who might otherwise be hesitant to engage due to previous experiences of marginalization.

Data were collected through four focus group discussions involving 18 participants (10 women and eight men). Focus groups were selected as the primary data collection method because they encourage interaction and collective sense-making, enabling participants to articulate shared and divergent experiences (Yegidis, Weinbach, and Myers Reference Yegidis, Weinbach and Myers2018). This approach was particularly suited to examining how racialized skilled immigrants negotiate professional barriers in dialogue with others facing similar challenges. Each session consisted of four to six participants and lasted approximately 90 to 120 minutes. Two sessions were conducted in person, and two were held via Zoom to accommodate participant preferences and prevailing public health considerations. All sessions were facilitated by the principal investigator using a semi-structured interview guide developed in alignment with the study’s central research questions. The guide ensured consistency across sessions while allowing flexibility for participants to narrate their experiences in their own words. Throughout the discussions, the researcher emphasized confidentiality, cultural sensitivity, and respect, thereby creating a supportive environment that encouraged openness. Each participant received a $50 gift card honorarium in recognition of their time and contributions.

Data Preparation and Analysis

All focus group sessions were audio-recorded with participants’ consent and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were reviewed for accuracy and served as the primary data source for analysis. To ensure deep engagement with the data, the researcher conducted repeated readings, complemented by note-taking and reflexive journaling to document emergent insights. Thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) six-phase framework, was employed to identify and interpret patterns of meaning across the dataset. This analytic approach was chosen for its flexibility and suitability for exploring complex, socially embedded experiences. The process began with familiarization through repeated readings, followed by systematic coding of significant features of the data. Related codes were then grouped to generate potential themes, which were subsequently reviewed and refined to ensure conceptual coherence. Each finalized theme was clearly defined and named to capture its central organizing idea. NVivo software (version 15, 2024) supported the coding, organization, and retrieval of data. To enhance the trustworthiness of the analysis, coding decisions and emerging themes were discussed collaboratively within the research team. This iterative review process helped to mitigate individual bias and ensure that interpretations remained grounded in the participants’ narratives. Detailed analytic memos and an audit trail were maintained throughout to promote transparency and rigor.

Participant Characteristics

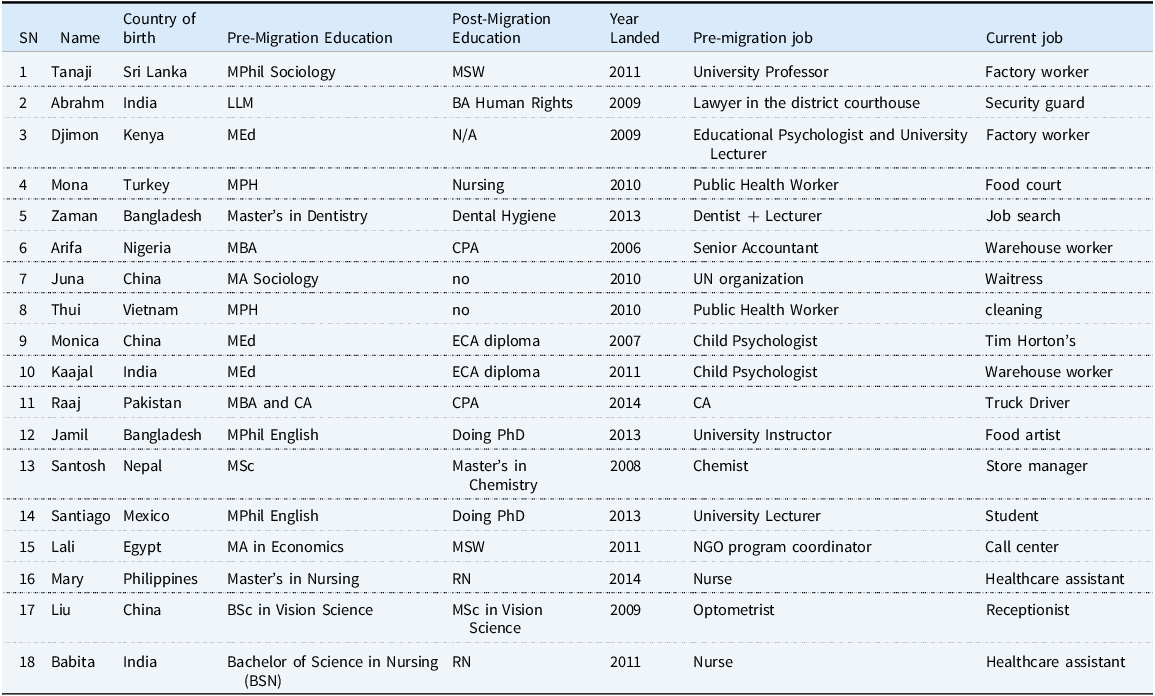

Table 3 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the 18 participants (10 women and eight men). Participants originated from a diverse range of countries, including Sri Lanka, India, Kenya, Turkey, Bangladesh, Nigeria, China, Vietnam, Nepal, Mexico, Egypt, and the Philippines. Their educational profiles were notably strong: most held advanced degrees (13 master’s, 3 MPhil), and several possessed professional qualifications in fields such as law, dentistry, and nursing. Many also pursued additional Canadian credentials post-migration, such as MSW, CPA, RN, and PhD programs, to align with domestic professional standards.

Before migration, participants had established careers across sectors, including academia, healthcare, law, finance, public health, and research. Their roles ranged from university professors and psychologists to dentists, accountants, nurses, and optometrists, with an average of four to eight years of professional experience. Following migration, however, the majority were employed in low-skilled or unrelated occupations such as factory work, security services, food service, cleaning, and warehouse labor. A smaller number were still engaged in credential recognition or further education. This stark occupational mismatch illustrates the extent of deskilling and underemployment experienced by racialized skilled immigrants in British Columbia’s labor market.

Table 3. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

Findings

Degrees in Hand, Doors Closed: The Skilled Immigrant Dilemma

This study explores the paradoxical realities faced by highly educated, professionally accomplished immigrants who arrived in Canada through skilled immigration programs. While these individuals were selected for their qualifications and global expertise, their lived experiences reveal the structural contradictions embedded within Canada’s immigration and labor market systems. The findings are organized into four interrelated themes and associated subthemes, each reflecting a distinct dimension of skilled immigrants’ encounters with systemic barriers, institutional inefficiencies, and intersectional discrimination. The conceptual “iceberg” metaphor has been used to visualize the visible and invisible barriers shaping these experiences. These findings trace the contours of exclusion, identity negotiation, and resilience within the skilled immigrant journey. Figure 2 presents the major themes and sub-themes.

Figure 2. Tip of the iceberg: degrees in hand, doors closed: the skilled immigrant dilemma.

Theme 1: The Promise and Paradox of Skilled Migration

This first theme captures the tension between the promise of skilled migration as a route to professional fulfillment and the structural realities that undermine that promise upon arrival. Participants’ narratives reveal a sharp disjuncture between their global expertise and the segmented Canadian labor market that privileges “Canadian experience/credentials” while devaluing foreign credentials. Two subthemes emerged: (a) Global Expertise, Local Barriers and (b) Dreams Confronting Labor Market Realities.

Global Expertise, Local Barriers

Participants arrived in Canada with substantial educational and professional backgrounds, often holding master’s or professional degrees and extensive work experience in fields such as healthcare, education, law, and research. Their professional identities were deeply tied to these credentials and achievements. One participant reflected, “I did a Master’s Degree in Nursing (MScN) from the University of the Philippines, Manila. I was a registered nurse, working at a hospital back home for about seven years.” Another shared, “I’m originally from Vietnam. We immigrated to Canada in 2010. I completed a Master’s in Public Health. I was working full-time in a hospital as a public health worker for about four years before coming to Canada.”

Despite their expertise, participants encountered significant barriers in having their qualifications recognized or valued in British Columbia’s labor market. As one noted poignantly, “Your back home flying is different than Canadian flying. So, you have to learn Canadian flying.” While their credentials were sufficient for immigration, they were often deemed inadequate for professional employment, producing a painful gap between pre-migration status and post-migration opportunity.

Dreams Confronting Labor Market Realities

Participants migrated under the FSW program with aspirations for upward mobility, stability, and better futures for their families. The decision to immigrate was guided by Canada’s points-based system, which appeared to reward human capital and merit. As one participant explained, “I discovered that to come to Canada under the Federal Skilled Worker program, there are specific requirements, right? Like language requirement, education requirement, age, health, and so many types of requirements, right?” However, upon arrival, optimism gave way to frustration. Participants reflected on the emotional impact of this realization. One participant recalled, “I landed in Canada carrying my dream of a professional opportunity, better career, but since the very first day I started feeling that those dreams were not real.” Many participants came to view the labor market as paradoxically demanding laborers rather than professionals.

Another participant stated, “They [Canada] need around 70–80% labourers here; and if they need labourers, why do they bring skilled professionals? Why don’t they recruit labourers like Gulf countries, Korea, or Israel do?” This growing disillusionment was deepened by prolonged job searches that often yielded no results. “I have already applied to more than 200 positions. It has been almost a year; I have been continuously applying, going on all available websites, using my sources, networking, and an employment counsellor, everybody, but no luck yet.” These accounts expose how systemic and institutional barriers effectively restrict professional entry, rendering migrants’ prior expertise invisible. The tension between the imagined promise of migration and the lived realities of the labor market lies at the heart of migrants’ settlement journeys, framing the recurring narrative of “dream versus reality.”

Theme 2: Structural Deskilling and Labor Market Exclusion

This theme examines how systemic processes, including credential devaluation, labor market segmentation, and institutional inefficiencies, produce patterns of deskilling and underemployment among skilled immigrants. These are not isolated setbacks but manifestations of a broader structural exclusion. Three subthemes emerged: (a) From Professional to Survival Work, (b) Credential Devaluation and the “Canadian Experience” Trap, and (c) Institutional Navigation and Systemic Inefficiencies.

From Professional to Survival Work

Despite holding advanced qualifications, nearly all participants were unable to secure positions aligned with their expertise. Instead, they found themselves in low-skilled, precarious, or survival jobs, often in warehouses, factories, or service industries. One participant recounted, “I was a university professor back home, but here I work in a factory,” one participant shared. Another noted, “Even with a Master’s in Public Health and prior experience from my home country, it wasn’t enough to secure a job in my field in Canada.” This shift represented more than economic displacement; it entailed a profound erosion of professional identity. Participants described the emotional and physical toll of this downward mobility and working in survival jobs. One participant shared, “I have to work in a factory on night shift with full of tears remembering my back days from my homeland,” one of the participants shared. Another added,

I went to a labour job through an employment agency. The job was a night shift—it was a nightmare for me. I had a sleeping disorder; I was working at night, and the next morning, I was crying, I was crying alone.

These narratives capture the cumulative strain of underemployment—its physical, psychological, and emotional dimensions.

Credential Devaluation and the “Canadian Experience” Trap

A recurring structural barrier was the persistent demand for “Canadian experience,” which acted as a gatekeeping mechanism that invalidated foreign professional experiences. One of the participants shared their experience satirically, “At that time, I wondered what ‘Canadian experience’ really meant. For example, I was a mathematics lecturer back home. If I am to teach mathematics, what I taught there should be similar to what is taught in Canada.” In response, many sought to overcome these barriers by pursuing further education, only to find that these efforts yielded little or no improvement. As one participant reflected, “I went to MSW with a hope that this degree would help me find a job… But unfortunately, it did not work.” This experience highlights the limited value of recredentialing in a labor market that continues to devalue prior qualifications and sustain structural barriers. Participants expressed deep frustration at the paradox of credential valuation—degrees that opened doors to migration were simultaneously devalued upon arrival. “My degree has expired; that does not work anymore. How many years I study doesn’t matter,” lamented one participant. This contradiction exposes the systemic inconsistency in Canada’s immigration regime, which celebrates skilled migration while obstructing the professional participation of those it recruits.

Institutional Navigation and Systemic Inefficiencies

Participants also described navigating employment and settlement institutions that often reinforced rather than alleviated exclusion. Many reported that employment counsellors and settlement agencies lacked the expertise to support professional reintegration. “Why don’t you [employment counsellor] counsel for teaching? Why are you diverting me to go to factories and warehouses? I have years of experience in teaching,” one participant asked. Settlement services were frequently described as generic and tokenistic. “They have a very general type of services, such as resume writing, interview skills, and training on basic email/internet use. These are very basic for me,” one participant noted. Another added, “When I went to the settlement agencies to seek their help to find a job in my nursing field, I found they don’t have the ability to find nursing jobs, but jobs in factories or warehouses.” Networking—so often portrayed as the key to professional success—offered little advantage against the weight of systemic bias. Participants described how their efforts to build connections were quietly thwarted by subtle exclusions and structural barriers that left their social capital unrecognized and unrewarded. As one participant explained,

For me, finding a job was so difficult, even though I have a strong network. The problem is that when I am observed through a lens of deficiency—language, culture, race—the networking won’t work, no matter how strong it is.

Participants characterized settlement services as generic and tokenistic, noting that they primarily provided basic supports, such as résumé preparation and rudimentary digital literacy training, while lacking the structural capacity to facilitate access to professional employment pathways in skilled sectors or in their professional fields.

Theme 3: Discrimination and Intersectional Marginalization

This theme highlights how racialized and gendered discrimination intersect with structural barriers to shape immigrants’ exclusion. Participants described the experience of discrimination both overtly—through hiring practices and workplace treatment—and covertly—through systemic filters that reproduced racial hierarchies. Two subthemes emerged: (a) Racialized Gatekeeping and Gendered Inequalities and (b) Social and Cultural Invisibility.

Racialized Gatekeeping and Gendered Inequalities

Many participants recounted direct experiences of racial bias in hiring practices, noting that decisions were often influenced by their race, ethnicity, or accent. As one participant shared,

Right after they see your picture or you as non-white, or your ethnic sounding name in a resume, the boss who is there for the interview, right away, they make a decision, say 80% of the decision, not to hire you.

Some recounted experiences of being explicitly racialized. One participant shared their experience when seeking a volunteer position at an agency: “I could hear a one-way conversation; and I heard a sentence, ‘He looks like an Indian.’ Then, a few minutes later, they said, “Currently, we are not taking volunteer or placement positions.” Accent discrimination also surfaced frequently. One of the participants shared his experience with a professor at a Canadian university: “He [professor] said, ‘You did an excellent job. You got an A. But you have an accent, my boy.” Women participants described additional layers of gendered marginalization. They described physically demanding tasks being allocated without consideration for gender differences: as one participant shared, “In my current job, we are around seven women and fifteen men. Sometimes the supervisor gives us heavy-weightlifting jobs. We are women, right? Biologically and physically, we are weaker than men. But he doesn’t understand.” Workplace power imbalances often intensify gendered marginalization. Another reflected, “The supervisor used to give me the hardest work… She called me out loud and asked me to pick up… I was crying the whole night, and the next day I quit the job.” These accounts reveal how race, gender, and power intersect to constrain upward mobility and reproduce inequities in the workplace.

Social and Cultural Invisibility

Although Canada is often portrayed as a country of diversity, inclusivity, and multiculturalism, many participants reported experiencing socio-cultural invisibility. One participant stated,

People say Canada is a multicultural country, but I think it is a monocultural country. You can’t celebrate your cultural festival here… If I want to take a day off to celebrate my festival, I may get off, but I will have to choose between losing my hours or not getting paid.

The erasure of cultural identity was eloquently discussed across the focus group discussions. For example, one participant stated,

The mainstream society wants to kill our identity, our cultural values, and our languages. If you wanna be Canadians, okay, you can, but the condition is you have to kill our identity first. That’s not the true meaning of integration, inclusion.

These reflections highlight a contradiction between official multiculturalism and lived exclusion—a reality where inclusion often demands assimilation.

Theme 4: Postcolonial Dimensions and Identity Negotiation

The final theme situates participants’ experiences within broader postcolonial dynamics, emphasizing how global hierarchies of knowledge and labor persist within contemporary migration regimes. Participants critically interpreted their deskilling not merely as an individual misfortune but as part of a broader political economy that extracts and devalues skilled labor from the Global South. Two subthemes were identified: (a) Modern Colonial Logics and Brain Waste and (b) Belonging, Mental Health, and Resistance.

Modern Colonial Logics and Brain Waste

Several participants framed Canada’s skilled immigration system as a form of modern colonial extraction. They interpreted their experiences through a colonial lens, describing the immigration system as exploitative to less resourceful countries in the global south. One of the participants asserted, “If Canada doesn’t need highly educated and skilled workers, why does it bring those educated people from the least developed countries? This is simply a modern form of colonization.” Others described a “triple loss” of brain waste—wasted talent for the individual, lost human capital for the home country, and underutilized potential for the host nation. One participant explained, “Just think how much money and time were invested to produce a doctor in those least developed countries. Canada simply lures these professionals, and when they get here, then sends them to manual work.”

Belonging, Mental Health, and Resistance

Participants expressed their struggles with belonging and identity. Despite formal integration markers such as citizenship or Canadian education, participants struggled to feel accepted. One of the participants stated, “I feel that materialistically I belong to Canada, but emotionally and professionally I don’t. I have to be socially, economically, culturally, and emotionally feel that I have those rights, but I don’t have them.” The mismatch between credentials and employment gradually eroded professional identity, confidence, and self-worth. One of the participants stated, “My Master’s in Public Health doesn’t match with the cleaning job I am doing at a motel,” one shared. Another added, “It has been four years since I started working at a factory job, still hopeful to find a job that aligns with my profession.” Many expressed mental health challenges linked to prolonged underemployment. The cumulative effects of exclusion, discrimination, and underemployment led to mental distress, as one of the participants described it.

Another participant recounted, “I had a sleeping disorder, I was working night and the next morning I was crying, I was crying alone. And I called my parents back home. I said, ‘I don’t want to stay here, I want to come back.” Yet, amid hardship, participants expressed resilience and hope. One participant shared, “I lost both of my parents 4 and 10 years ago. Every day when I am working with these people, I feel I am with my parents, you know, it’s so rewarding, right?” Another reflected, “I want to work hard for my children’s future here, but I am worried that my children may go through a similar circumstance that I am going through. Let’s be hopeful their life will be a bit easier than mine.” These lived narratives call for critical reflection on how Canada defines merit, integration, and inclusion within an increasingly globalized labor market.

Summary of Key Findings

Overall, the findings reveal a striking disjuncture between the promise of Canada’s skilled migration framework and the lived realities of racialized immigrants navigating its labor market. Participants’ narratives highlight how structural and discursive forces systematically produce deskilling and underemployment. These mechanisms not only constrain economic participation but also erode professional identity, belonging, and well-being. The experiences of intersectional discrimination further demonstrate how race, gender, and accent operate as intertwined axes of marginalization. At a broader level, participants interpreted these experiences through colonial lenses, viewing Canada’s skilled migration system as reproducing global hierarchies of value and labor. Yet amid structural exclusion, their stories also reflect resilience, hope, and an enduring pursuit of dignity. These insights point to the need for a critical re-examination of how integration, merit, and inclusion are conceptualized within Canada’s labor and immigration systems.

Discussion

The findings from this study reveal a structured paradox: immigrants are actively recruited to Canada for their human capital, yet they encounter labor market architectures that constrain the recognition and utilization of that capital. The narratives of skilled immigrants illuminate how immigration policy, credentialing regimes, hiring practices, and organizational norms interact to produce deskilling, underemployment, and identity erosion, while also eliciting resilience and counter-narratives of belonging. At the heart of these findings lies a stark contradiction between the rhetoric of meritocratic migration and the realities of stratified labor market incorporation. Critical migration theorists have long observed how states strategically mobilize skilled migration to serve economic imperatives while maintaining differentiated access to rights and opportunities (Anderson Reference Anderson2013; Shachar Reference Shachar2020; Sharma Reference Sharma2005). Canada’s FSW program exemplifies this contradiction. While the immigration system rewards high human capital at the time of selection, post-arrival realities often devalue these same credentials through employer bias, credentialing barriers, and institutionalized demands for “Canadian experience/credentials.” Participants’ reflections—ranging from the sense of betrayal expressed in “I landed in Canada carrying my professional dream… those dreams were not the real” to the critique that “they [Canada] need 70–80% labourers here”—highlight this disjuncture between the promise of upward mobility and the structural reproduction of inequality. The metaphor “your back home flying is different than Canadian flying” encapsulates this epistemic rupture: expertise developed in the Global South is rendered symbolically inferior to Western norms. These findings are consistent with previous research (Gyan et al. Reference Gyan, Lafreniere, Diallo, Wilson-Forsberg, Karki and Hinkkala2024; Karki, Mullings, and Giwa Reference Karki, Mullings, Giwa and Deshpande2023b; Mullings et al. Reference Mullings, Giwa, Karki, Shaikh, Gooden, Spencer and Anderson2020). The very institutions that position Canada as a global hub for talent simultaneously reproduce hierarchies of legitimacy, privileging “local” knowledge while disqualifying international expertise. This process exemplifies what Bauder (Reference Bauder2003) terms institutionalized exclusion, in which professional licensing and employer practices transform global capital into local disadvantage.

Structural Deskilling and Systemic Exclusion: The study’s findings align with existing research demonstrating how structural barriers, not individual deficits, underlie immigrant underemployment. For instance, Oreopoulos (Reference Oreopoulos2011) and Quillian and Lee (Reference Quillian and Lee2023) have documented significant hiring penalties for applicants with foreign-sounding names or international credentials, even when qualifications are equivalent. Statistics Canada (2024) reports that over one in four immigrants with a bachelor’s degree or higher work in occupations requiring only a high school education or less, evidence of persistent “brain waste.” Similarly, wage and occupational gaps remain significant for racialized immigrants despite comparable education (Block and Galabuzi Reference Block and Galabuzi2018; Statistics Canada 2020). An analysis from the C.D. Howe Institute estimates a wage gap of approximately 46% between overqualified immigrants and their Canadian-born peers (Mahboubi and Zhang Reference Mahboubi and Zhang2024). These disparities are not reflections of individual inadequacy but of systemic bias embedded in institutional norms of employability and professional legitimacy. Participants’ accounts of working in factories, warehouses, or cleaning jobs—after careers as nurses, professors, or dentists—speak to the embodied humiliation of deskilling and professional loss. These findings align with Creese and Wiebe’s (Reference Creese and Wiebe2012) observations from over a decade ago, suggesting that this is not a transitional integration issue but a persistent structural feature of the Canadian labor market. The continued underutilization of skilled immigrant labor points to significant economic consequences: lost productivity, widening skills mismatches in sectors facing acute shortages, lower long-term tax contributions, and a misalignment between immigration policies and labor market absorption. The persistence of deskilling cannot be attributed solely to individual adaptation; rather, it points to ongoing institutional constraints and subtle forms of racialized gatekeeping (Creese Reference Creese2018). These dynamics suggest that Canada’s labor market has yet to fully develop the structural capacity needed to translate immigrant human capital into equitable economic participation.

The “Canadian Experience” as a Mechanism of Exclusion: The demand for “Canadian experience/credentials” emerged as a pivotal mechanism of exclusion in both policy and practice. Although framed as a neutral indicator of employability, it operates as a racialized gatekeeping tool that privileges cultural proximity to dominant norms. The Ontario Human Rights Commission (2013) has formally acknowledged that blanket requirements for Canadian experience may constitute systemic discrimination. Yet, such expectations remain embedded in hiring processes and licensing bodies—particularly in regulated professions. Participants described interview scenarios in which their international experience was dismissed as “not Canadian enough,” even when directly applicable to job criteria, and several recounted being asked to demonstrate “accent clarity” despite holding Canadian postsecondary degrees. These narratives exemplify how Canadian experience functions as a proxy for whiteness and cultural conformity, reinforcing what Sakamoto, Chin, and Young (Reference Sakamoto, Chin and Young2010) identify as a preference for local habitus rather than transferable expertise. Participants who pursued recredentialing encountered parallel barriers: despite completing Canadian graduate degrees or bridging programs, employer-side skepticism persisted, leading many to cycle through survival employment and contract work unrelated to their fields. This pattern aligns with national reviews indicating that the Foreign Credential Recognition Program, while improving procedural fairness, has limited impact when employer discretion and provincial inconsistencies remain unregulated (Employment and Social Development Canada [ESDC], 2020). Although the Foreign Credential Recognition Program has improved procedural fairness, its impact remains constrained by provincial inconsistencies and the absence of mechanisms enforcing equitable hiring (Parliamentary Information and Research Service 2020). The program’s focus on assessing equivalency does not address the underlying issue: skill recognition is socially and racially mediated and thus cannot be resolved solely through procedural reform. These examples ground the theoretical claim that Canadian experience functions as a proxy for whiteness—not merely symbolically, but materially—through hiring practices, licensing requirements, and the lived consequences of credential devaluation.

Colonial Dimensions of “Brain Waste”: The political economy of “brain waste” extends beyond individual losses to systemic inefficiency and moral contradiction. Participants’ framing of their experiences as a “modern form of colonization” points to the enduring colonial logics embedded within global labor flows. Scholars such as Raihan, Chowdhury, and Turin (Reference Raihan, Chowdhury and Turin2023) and Sharma (Reference Sharma2020) describe this as a form of neo-colonial labor governance, wherein Western economies benefit from the mobility of skilled labor while withholding recognition and authority. This dynamic produces a “triple loss” (Karki Reference Karki2025): skilled migrants experience identity erosion, sending countries lose valuable human capital, and host societies fail to capitalize on the full potential of their labor. Reitz (Reference Reitz2001) long ago noted that underutilization of immigrant skills is a durable feature of Canada’s economy, sustained by occupational closure and racialized hiring norms. Recent evidence confirms that racialized immigrants remain overrepresented in precarious and low-paying sectors despite high educational attainment (Mooten Reference Mooten2021; Statistics Canada 2020). Participants’ accounts of “crying alone during night shifts” embody the emotional cost of structural exclusion. Such experiences mirror the psychological sequelae of perceived underemployment and discrimination identified by Szaflarski and Bauldry (Reference Szaflarski, Bauldry and Frank2019). Through a decolonial lens, deskilling becomes not just an economic phenomenon but an epistemic one: the privileging of Western credentials constitutes an epistemic hierarchy (Bauder, Reference Bauder2015) that marginalizes immigrant knowledge. As Tuck and Yang (Reference Tuck and Wayne Yang2012) suggest, these hierarchies sustain colonial logics under the rhetoric of quality assurance and professional regulation.

Intersectionality, Discrimination, and Conditional Belonging: An intersectional analysis further illuminates how race, gender, accent, and migration status intersect to shape exclusionary outcomes. The findings of this study closely align with the theoretical framework, suggesting that immigrant deskilling is neither incidental nor temporary but rooted in broader systems of labor governance, racialized credentialing, and epistemic exclusion. Participants’ experiences of résumé rejection based on ethnic names, accent discrimination, and gendered task assignments align with empirical evidence of systemic racism in hiring and promotion (Block and Galabuzi Reference Block and Galabuzi2018; Quillian and Lee Reference Quillian and Lee2023). Studies consistently show that identical résumés receive fewer callbacks when linked to non-Anglophone or racialized names (Oreopoulos Reference Oreopoulos2011; Quillian and Lee Reference Quillian and Lee2023). For women, these inequalities are compounded by gendered expectations and family responsibilities, often pushing them into precarious or part-time employment (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada [IRCC], 2021). Participants’ descriptions of being assigned physically demanding or subordinate tasks echo research documenting a “triple disadvantage” of gender, race, and migrant status (Block, Galabuzi-Grace, and Tranjan Reference Block, Galabuzi-Grace and Tranjan2019; Karki Reference Karki2025). Language emerged as another axis of exclusion. Accent-based bias functioned as linguistic gatekeeping, transforming speech into a racial marker. This subtle form of discrimination erodes a sense of belonging even within nominally multicultural workplaces. Participants’ accounts of cultural invisibility underscore the persistence of monocultural norms within institutions that espouse diversity. As Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2012) argues, this “everyday governance of belonging” normalizes one cultural framework as the universal standard. Decolonial social work theorists identify such institutional monoculturalism as a form of epistemic violence: institutions claim inclusivity while enforcing assimilation to dominant norms (Dominelli Reference Dominelli2002). These everyday exclusions aggregate into structural underrepresentation in leadership and professional roles. Racialized Canadians who experience repeated microaggressions report higher levels of alienation and conditional belonging. Participants’ reflections, “I belong materially, but emotionally and professionally, I don’t,” capture this fracture between structural inclusion and affective belonging, echoing Berry’s (Reference Berry2005) concept of duality in acculturation outcomes, where citizenship or employment does not guarantee affective belonging.

Institutional Responses and the Limits of Settlement Support: While settlement and employment services play a central role in supporting newcomers, participants’ accounts highlight their structural limitations. Many described these agencies as offering “generic” assistance—résumé workshops or interview skills training—rather than meaningful pathways to professional reintegration. Research similarly notes that one-size-fits-all models prioritize rapid labor market entry over long-term career integration (Intungane et al. Reference Intungane, Long, Gateri and Dhungel2024; Shields, Drolet, and Valenzuela Reference Shields, Drolet and Valenzuela2016). Such approaches individualize responsibility for integration, shifting focus away from employer discrimination and credential bias. This depoliticization of settlement work sustains systemic inequities under the guise of neutrality. The resulting exclusions reverberate across psychosocial domains, producing anxiety, grief, and isolation. These experiences align with findings that underemployment and discrimination are major predictors of psychological distress among immigrants (Elshahat, Moffat, and Bruce Newbold Reference Elshahat, Moffat and Bruce Newbold2022; Hynie Reference Hynie2018; Lin Reference Lin2024). Hynie (Reference Hynie2018) observes that post-migration stressors, such as status loss and exclusion, often outweigh pre-migration trauma in shaping well-being.

Resilience, Agency, and the Ethics of Structural Change: Despite these adversities, participants articulated remarkable resilience and hope. Resilience in this context refers to the capacity to adapt and persist in the face of adversity, though it often obscures the structural conditions that make such endurance necessary (Karki, Dhungel, and Marriette Reference Karki, Dhungel and Marriette2025; Marriette et al. Reference Marriette, Dhungel, Karki and Tovillo2025). Their determination to work “for their children’s futures” reflects both endurance and the moral weight of intergenerational aspiration. This ambivalent resilience complicates deficit narratives of immigrant suffering by highlighting agency within constraint. However, as anti-oppressive scholars caution, resilience should not be romanticized in ways that obscure the structural sources of oppression (Dominelli Reference Dominelli2002). Ethical and policy responses must therefore move beyond individualized coping toward collective advocacy and structural transformation. Anti-oppressive and decolonial frameworks call for interventions that target systemic inequities rather than focusing solely on immigrant adaptation (Dominelli Reference Dominelli2002). Social workers and policymakers should engage employers, regulatory bodies, and governments to dismantle credential cartels, discriminatory hiring, and exclusionary licensing practices. Equally, challenging the epistemic dominance of Western credentialism requires the development of mutual recognition frameworks that value diverse professional traditions and knowledge systems.

Implications and Recommendations

The findings of this study highlight the urgent need to reimagine Canada’s skilled migration framework through a structural rather than an individual lens. Current policies valorize human capital at the point of selection yet systematically undermine it through credentialing regimes, employer bias, and racialized notions of “fit.” Addressing these contradictions requires coordinated, justice-oriented transformation across policy, practice, and institutional culture.

Policy Implications: At the policy level, reform must begin with accountability. Federal and provincial governments should establish a unified, enforceable framework for credential recognition that ensures transparent, timely, and equitable assessments across provinces and professions. The Foreign Credential Recognition Program, while conceptually progressive, remains fragmented and largely voluntary; it must be strengthened through binding national standards, oversight mechanisms, and anti-discrimination provisions that hold professional regulatory bodies and employers accountable. Equally critical is dismantling the entrenched Canadian experience/credentials requirement, which often operates as an exclusionary proxy for race and origin. Human rights commissions and labor ministries should expand compliance monitoring to ensure that hiring and licensing standards assess demonstrable competence rather than cultural conformity. Immigration policy should also be explicitly tied to anti-racism and equity mandates, recognizing integration as both an economic and social process.

Practice Implications: For practitioners, particularly in social work, employment services, and settlement sectors, these findings call for a paradigm shift from adaptation-based models to transformative practice. Agencies must move beyond “job readiness” paradigms that individualize responsibility for integration. Instead, they should function as advocates challenging discriminatory employment structures while collaborating with employers to develop professional reintegration pathways. Embedding anti-oppressive and decolonial frameworks in practice is essential. Practitioners must cultivate cultural humility, interrogate systemic bias within their organizations, and build intersectoral partnerships with employers, unions, and professional associations. Training programs in social work and allied disciplines should integrate critical migration and anti-racist perspectives, preparing professionals to engage not only at the service-delivery level but also in policy and organizational advocacy. True inclusion requires structural transformation within institutions that hold power over recognition and opportunity. Employers, licensing bodies, and universities must critically examine how their internal hierarchies reproduce exclusion. This includes revising hiring metrics that privilege “Canadian experience/credentials,” conducting regular equity audits, and incorporating diverse epistemologies of knowledge and professionalism. Institutional change is not merely an ethical ideal; it is an economic necessity for a society increasingly reliant on global expertise. Valuing transnational knowledge systems strengthens innovation and positions Canada to fulfill its stated commitment to diversity and inclusion.

Directions for Future Research

Future research should deepen understanding of how power, race, and epistemology intersect to shape the valuation of “skill” in contemporary migration regimes. Comparative analyses across provinces and sectors could reveal how varied regulatory contexts influence integration outcomes. Longitudinal research would also illuminate how skilled immigrants’ trajectories evolve as they navigate recredentialing, retraining, and occupational mobility. The perspectives of immigrant women, racialized professionals in underrepresented fields, and migrants in rural or non-metropolitan contexts remain particularly underexplored. Additionally, scholarship must move beyond documenting barriers to evaluating structural interventions, including employer-led diversity initiatives, alternative credentialing models, and community-driven advocacy. Participatory research methodologies, grounded in collaboration with immigrant professionals, can generate praxis-oriented knowledge that informs equitable policy reform.

Conclusion

This study reveals a central paradox within Canada’s skilled migration regime: while the state selects immigrants based on education, expertise, and economic potential, institutional practices frequently devalue those very qualifications upon arrival. Credentialing systems, licensing bodies, and employer expectations operate as gatekeeping mechanisms that reproduce racialized hierarchies while maintaining a veneer of neutrality. The consequences extend beyond the labor market. Deskilling and exclusion unsettle identity and belonging, generating psychological strain and moral fatigue. Yet within these narratives of pain are also moments of endurance and hope. Participants continued to pursue retraining, volunteer work, and better futures for their children, reflecting what may be termed “hopeful endurance,” a moral determination to transform suffering into continuity. However, resilience must not be mistaken for justice. As Dominelli (Reference Dominelli2002) cautions, resilience without structural reform risks legitimizing inequality rather than challenging it. A just and inclusive migration model must therefore move beyond human capital theory and interrogate the very criteria that define “skill” and “merit.” Recognizing plural forms of knowledge—and dismantling the epistemic hierarchies that privilege Western credentials—remains essential to realizing the ethical promise of multiculturalism. Inclusion, in this sense, begins not with migrants learning to conform to existing norms, but with institutions reconfiguring their frameworks to value diverse expertise and histories.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Canada [Grant number: 430-2022-00068]. The funding body had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The author reports no potential conflict of interest.

Disclosure statement

AI-assisted copy-editing tools (including Grammarly and Microsoft Editor) were used exclusively to improve language clarity, grammar, and style. No AI tools were used for content generation, data analysis, interpretation, or decision-making.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia (Protocol No: 101494). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the study.

Karun Kishor Karki is an associate professor in the School of Social Work at the University of British Columbia. He is a Founding Director of the Emotional Well-being Institute (EWBI) Canada and a Co-Director of Education and Professional Development, EWBI Geneva, Switzerland. His research focuses on critical social justice issues, including anti-racism, anti-casteism, and the well-being of marginalized groups, including immigrants, refugees, and LGBTQ+ communities in Canada and internationally. Informed by postcolonial theory, Dr. Karki explores how biopolitical and necropolitical spaces within the borders of the nation-states govern people and how the state’s sovereign power becomes a persistent recurrence of the process of exclusion and disposition of people in light of today’s pressing issues, including the migration crisis, global displacement, the rise of populism, homonationalist practices, and state-sanctioned targeting of gender, sexual, racial, and ethnic “others.”