Introduction

European Union (EU) agencies are ‘integral in ensuring that regulatory policies can be implemented coherently and consistently throughout the EU’ (Rittberger & Wonka Reference Rittberger and Wonka2012: 3). However, they do not have direct legal power to implement regulations (Busuioc Reference Busuioc2013), but usually must rely on fostering their reputation and image among competent member state authorities, businesses, professionals, consumer groups and the media to gain authority. As Gehring and Krapohl (Reference Gehring and Krapohl2007: 28) argue, agencies ‘[o]perate in highly politicized environments and the extent to which they manage to establish themselves as credible regulators will often be dependent on the manner in which they manage their relations with, and competing expectations from, the multiple political actors within their environment’. In short, agencies have to become political entrepreneurs.

This article advances an agenda for studying how EU agencies engage their political environments, via a focus on their ‘entrepreneurial strategies’, defined as how they work informally to spread information and ideas. Existing research on EU agencies has systematically studied their formal and informal accountability to, and autonomy from, central EU institutions and national member states (see Rittberger & Wonka Reference Rittberger and Wonka2011). This literature, following Majone's (Reference Majone1996) work, has tended to assume EU agencies have significant levels of power, which require control from, and accountability to, political principals. By contrast, this article proposes an agenda that views agencies’ powers as dynamic and ‘emergent’, based on engagement with external actors, much like the EU's wider executive order (Trondal Reference Trondal2010). Existing studies examine how agencies utilise connections with external actors to manage complex transboundary problems and crises (Boin et al. Reference Boin, Busuioc and Groenleer2014), and deliver effective policy coordination (Heims Reference Heims2016). ‘Stakeholder engagement’ has been touched upon in studies of the composition of agency boards (Busuioc Reference Busuioc2012; Font Reference Font2015; Buess Reference Buess2015) as well as studies on how agencies function as centres of epistemic networks (Trondal & Jeppesen Reference Trondal and Jeppesen2008). Entrepreneurship has not, however, formed a central focus of analysis. There has yet to be a research agenda specifically on EU agencies’ entrepreneurial activities that systematically maps variability across agencies. This connects with stakeholder engagement but goes beyond it because it focuses on ‘everyday’ practices rather than the structure of agency board membership.

This article fills this gap by providing the first systematic typology of EU agencies’ entrepreneurial strategies, encompassing all 33 official decentralised agencies. The central argument is that there are four types of entrepreneurial strategies EU agencies adopt: technical‐functional; insulating; network‐seeking; and politicised. To make this argument the article innovates both conceptually and empirically. Conceptually, it draws from sophisticated accounts of international organisation (IO) authority, arguing that a map of entrepreneurial strategies must account for how agencies share information and ideas (how ‘entrepreneurial’ they are), in a context of a more or less politically salient environment (Broome & Seabrooke Reference Broome and Seabrooke2015; Stone & Ladi Reference Stone and Ladi2015). Knill et al.’s (Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017) typology of IO strategies for gaining authority is adapted as a framework, covering four types: technical‐functional, insulating, network‐seeking and politicised. To operationalise this framework, measurement across two dimensions – ‘political salience’ (within media and parliamentary circles) and ‘entrepreneurial methods’ (including agencies’ media engagement, face‐to‐face networking, and knowledge dissemination and learning practices) – is used. Evidence is then deployed on both dimensions from a newly constructed database of 33 EU agencies. Mapping agencies on these dimensions shows they conform to the four theorised types, albeit some are marginal between different types. The typology is validated through semi‐structured interviews in 11 agencies, from a wider project of 32 interviews, justifying how to distinguish between categories in the typology.

The article proceeds as follows. First, it stipulates that entrepreneurship is an important and distinctive topic for analysis because it is essential for the authority of EU agencies. Second, the article argues for a typology of entrepreneurial strategies including the political salience and entrepreneurial methods dimensions, and building on Knill et al.’s (Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017) recent contribution. Third, the research strategy is set out, the methods and data used are specified, a ‘conceptual typology’ is developed and an ‘ordinal’ dataset measuring entrepreneurial methods is constructed. Fourth, the article maps agencies according to their political salience and entrepreneurship methods, and provides evidence for each type of entrepreneurial strategy. In conclusion, the key contributions of the study, some limitations and agendas for further research are discussed.

European agencies and entrepreneurship: The search for authority

Since the early 1990s a large number of decentralised EU agencies have been created with quasi‐regulatory, informational, coordination or executive powers (Busuioc Reference Busuioc2013). Agencies have usually been established on a case‐by‐case basis, ‘on a proposal from the [European] Commission, but with the decision taken by the European Parliament or the Council of Ministers’ (Schneider Reference Schneider2009: 33), and therefore their powers are highly differentiated. According to the so‐called ‘Meroni Doctrine’ – a judgment delivered by the European Court on 13 June 1958 – ‘a delegation of powers can only involve clearly defined executive powers, the use of which must be entirely subject to … supervision’ (Schneider Reference Schneider2009: 35–36). As such, the delegation of powers to agencies has been uneven. Importantly, ‘no European agencies created so far have been endowed with genuine, direct rule‐making powers’ (Busuioc Reference Busuioc2013: 23), which means that no agency is able to make new binding rules independent of ratification by Community institutions. Agency authority is therefore crucially contingent on how it is perceived by external actors, and in this sense agencies ought to be seen as political actors, carrying specified roles and functions, but simultaneously establishing themselves as autonomous actors in highly charged political environments.

Existing research tends to focus on the implications of differing forms of ‘stakeholder involvement’. Analysing stakeholder practices by the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA), which in its early years focused primarily on the scientific details of regulatory opinions, Borras et al. (Reference Borrás, Koutalakis and Wendler2007: 592) find that ‘it remains questionable how far stakeholder consultation by EFSA can address concerns from the wider institutional and political context’. Political issues of food safety, they argue, were far greater than EFSA could reasonably account for with a narrow stakeholder engagement setup. Schout (Reference Schout2011: 381) also points to limitations of stakeholder involvement in the case of the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), stating that ‘as regards the initial hope that agencies would increase expert input in decisions, this has only happened to a limited extent’. Pre‐existing European networks, he argues, continue to dominate decision making in the aviation sector. Buess (Reference Buess2015: 106) also raises concerns about how extensive stakeholder engagement mechanisms really are, with an examination of six agencies finding ‘low levels of horizontal peer accountability’.

Other scholars, however, have found entrepreneurialism can prove important for achieving agency aims. Groenleer (Reference Groenleer2009: 368) shows that ‘networking and cooptation’ can be useful for building support for an agency within the broader multilevel governance environment. Klika (Reference Klika2015) demonstrates this process as an interactive one of sourcing support from relevant non‐state actors to support a Europe‐wide policy, using the example of the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) and its implementation of the ‘REACH’ initiative on chemical safety. Here, stakeholder engagement can be seen as a political game in which an agency seeks out support for its agenda while industry lobbyists, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and other actors seek to influence that agenda. Where agencies play the game well they can benefit significantly, as Groenleer (Reference Groenleer2009) shows in the case of the European Medicines Agency, which gained substantial external and internal support in its early years.

Existing research hence suggests agencies can improve their organisational authority via entrepreneurial activities, but that their strategies are heterogenous and results are varied. This research has examined the groups agencies tend to engage via survey and interview data, emphasising the centrality of the European Commission compared to non‐state actors (Trondal Reference Trondal2010; Egeberg & Trondal Reference Egeberg and Trondal2011). Studies also map formal arrangements for incorporating expertise from differing stakeholder groups in the form of consultation and membership of boards (Buess Reference Buess2015). The focus has been primarily on evaluating whether these adhere to normative standards of legitimacy – for example, input, output and throughput (Schout Reference Schout2011). Where interactions with external stakeholders have been examined, they have focused principally on coordination with and accountability to Community institutions (Font & Pérez Durán Reference Font and Pérez Durán2016) and national‐level state authorities (Heims Reference Heims2016).

The emphasis, therefore, has been on who agencies engage with in largely formal settings. What is missing is a map of how agencies interact with their political environments informally at day‐to‐day level through, for example, forms of communication and coordination with industry and NGOs. As Chatzopoulu (Reference Chatzopoulou2015: 160) comments on the existing EU agencies literature, ‘these contributions ignore what exactly happens within the governance process’. Constructing a map of how EU agencies interact with their diffuse environments, with a concern for the differentiated nature of EU policy areas, can enable a better understanding of how agencies act as authorities ‘informally’ within a complex transnational political landscape. This article represents the first attempt at doing this in a systematic manner, across all 33 EU agencies.

Four ideal typical entrepreneurship strategies for EU agencies

‘Entrpreneurship’ is a broad and amorphous concept, and overlaps with general ‘stakeholder engagement’ practices where public organisations aim to engage ‘no longer simply [with other] public sector agencies but also private firms, the media and associations in civil society’ (Bovaird Reference Bovaird2005: 218). The potential organisations to which the concept applies is vast, including the public, private and voluntary sectors. The mechanisms for ‘engaging’ have been diverse, from pure ‘one‐way’ communication to ‘deep’ local‐level involvement (Bell & Hindmoor Reference Bell and Hindmoor2009). Some scholars have questioned the utility and normative desirability of these mechanisms when ‘colonized by elites at the exclusion of many potentially affected groups and individuals’ (Hendriks Reference Hendriks2008: 1010). This article avoids the term ‘stakeholder engagement’, with its often naïve assumptions of such practices being democratically ‘good’, by focusing on entrepreneurship strategies as the potential range of approaches through which EU agencies strategically disseminate information and ideas informally to relevant organisations and actors, in light of their political context. This definition finds inspiration from the literature on transnational public administration (TPA), which has developed a sophisticated grasp of how authority works ‘informally’ at a transnational level.

Andrew Moravscik (Reference Moravcsik1999: 268; emphasis added) argues that ‘supranational officials and institutions … exercise “leadership” rather than formal power. In short, they are “informal” political entrepreneurs’. ‘Political entrepreneurs’ are organisations attempting the ‘manipulation of information and ideas’ (Moravscik Reference Moravcsik1999: 272). In this definition, authority is ‘a quality of communication’ (Friedrich Reference Friedrich1958: 36) rather than a form of power given by formal‐legal fiat (Knill et al. Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017). Studies of authority at the transnational level have therefore focused on everyday processes of ‘socialisation’ (Broome & Seabrooke Reference Broome and Seabrooke2015). Stone and Ladi (Reference Stone and Ladi2015) map out a range of ways ‘authoritativeness’ is enacted at the global level – via, for example, the creation of a prospective ‘civil service’ by the United Nations; appeals to normative values made by charitable trusts; the professionalism of management consultancy companies like Deloitte and KPMG; and even the democratic credentials of ‘global civil society’ forums. The targets of these ‘appeals’ are necessary flexible, covering those who may be important to influence so as to spread specific ideas or achieve more generic ‘influence’ – hence this article's flexible definition of ‘relevant organisations and actors’ rather than specific groups.

The key insight of TPA is thus a concern not merely for the institutional processes and procedures of IOs, but their ‘entrepreneurship’ or the ‘various styles of professionalism in play’ where ‘public authority has been semiprivatized’ (Stone Reference Stone2008: 33). The shape of this ‘entrepreneurship’ is paradoxically obscure, yet crucial to their functioning. Research on national‐level public organisations has to some extent recognised the importance of developing authority through ‘entrepreneurial‐style’ activities, via concepts, such as ‘reputation’ (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2010). Reputation theory shows how and when agencies engage in communicative action when their reputation is either high or low, secure or under threat, rather than as a result of legal fiat. Gilad et al. (Reference Gilad, Maor and Bloom2015), for example, show how agencies tend to communicate more when they have a lower reputation, whereas regulatory ‘silence’ happens where their reputation is strong. Busuioc and Lodge (Reference Busuioc and Lodge2017) demonstrate how the reputation of agents and their principals can influence different types of communicative relationships between the account‐givers and account‐holders. These studies valuably highlight the importance of understanding the political environment of agencies when analysing their ‘entrepreneurial’ activities.

TPA, however, highlights the especially ‘emergent’ character of organisational authority at a transnational level where EU agencies are based, and the need to map this space with a special concern for the highly informal conduct of these bodies against highly uneven political status of their environments. EU agencies clearly have a much stronger remit, and are more embedded in national‐level authorities than most other transnational bodies, particularly in areas like medicines and food. Existing work has thus tended to apply national‐level public administration concepts to their work. This article does not claim that TPA can be applied as a wholesale alternative, but rather it is useful for analysing the diffuse ‘entrepreneurial’ aspects of their work, which come from operating above and between EU member states. Such practices interact with diffuse expectations of the salience of the bodies, as Moravscik (Reference Moravcsik1999) notes, rather than responding to specific reputational ‘threats’, which are atypical at the transnational level compared to the national or subnational levels. As Stone and Ladi (Reference Stone and Ladi2015: 8) note, ‘this [transnational] “sphere” remains conceptually shapeless in its institutional, professional and policy practice dimensions’. This article thus contributes by filling this gap.

Dimensions of entrepreneurial strategies: Political salience and entrepreneurial methods

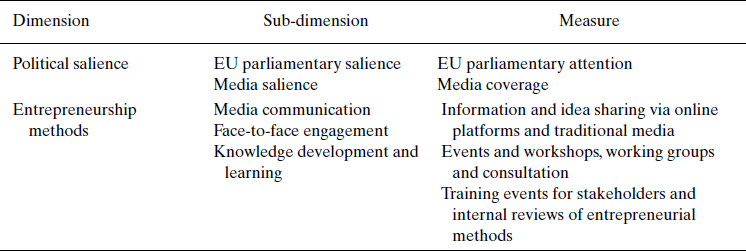

To capture EU agencies’ entrepreneurial strategies systematically in the nuanced context described above, this article maps two dimensions: political salience and entrepreneurial methods. Entrepreneurial strategies involve the strategic choice of particular methods to engage of a broad political sphere on the basis of expectations about how that environment will respond. ‘Entrepreneurial’ organisations will select particular methods or tools to achieve the aims they have, be they meeting relevant groups in person or disseminating their message through the media and other outlets to ‘target’ audiences. This ‘strategic’ element will be sensitive to the salience of the organisation within the transnational political community, including potential venues of accountability and national and international media. These dimensions are summarised in Table 1 and specified below.

Table 1. Dimensions determining entrepreneurial strategies

Defined by Koop (Reference Koop2011: 210), ‘political salience’ is ‘the degree of importance which is attributed to political matters’. Kelemen and Tarrant (Reference Kelemen and Tarrant2011: 943) argue that ‘neither functional necessities nor convictions about the efficacy of “network governance” explain decisions concerning the design of European regulatory structures … the degree of distributional conflict in the policy area in question explains the design of EU regulatory bodies’. More generally, Koop (Reference Koop2011: 210) explains; ‘politicians can be assumed to invest more in those issues which they themselves and the public care about, we may expect the political salience of the issue with which an independent agency deals to affect its degree of accountability’. Salience can be viewed either in terms of the broad salience of an issue area, or more specifically of an organisation itself in public and political discourse. In this article, ‘salience’ refers to the visibility specifically of agencies. It is closely related to ‘valence’, referring to ‘negative or positive tone’ of coverage or attention by the media or public (Maor & Sulitzeanu‐Kenan Reference Maor and Sulitzeanu‐Kenan2013: 32). For our purposes, valence is not incorporated as a relevant dimension, given that EU agencies are usually less directly affected by day‐to‐day national press coverage and public opinion than by general ‘attention’.

‘Entrepreneurial methods’ is defined in Moravscik's (Reference Moravcsik1999) terms as the informal dissemination of ‘information and ideas’. Integrating both TPA and existing work on agencies, this dimension can be split into three areas: media communication; face‐to‐face networking; and knowledge development and learning. ‘Media communication’ refers to information and idea sharing via online platforms like social media, as well as traditional media like industry magazines and daily newspapers. It has become increasingly prominent in the agencies literature, as research shows ‘government agencies set aside substantial resources for media management and adapt their organizational structures, processes, and rules’ (Fredriksson et al. Reference Fredriksson, Schillemans and Pallas2015: 1). As ‘government agencies appear in a large share of the daily news coverage. … This has led governments and agencies to make investments in media‐related activities’ (Fredriksson et al. Reference Fredriksson, Schillemans and Pallas2015: 2–3).

This ‘mediatised’ engagement is complemented by more ‘face‐to‐face’ engagement in the form of events to which stakeholders are invited for networking purposes (conferences and workshops, for example) and collaborative taskforces or working groups. Stakeholders are invited for more formalised involvement or consultation on agency work, or what Moffitt (Reference Moffitt2014) calls ‘participatory bureaucracy’. This form of engagement has been highlighted, for example, by Stone (Reference Stone2007) who emphasises the importance of conferences and workshops as ways in which think tanks ‘informally’ shape ideas and build networks. Recent work on agencies translates this argument, suggesting such events help develop a positive reputation for agencies (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2010). Moreover, face‐to‐face stakeholder forums and consultation processes can publicise and add ‘normative authority’ to agency decisions (Borras et al. Reference Borrás, Koutalakis and Wendler2007).

Finally, ‘knowledge development and learning’ refers to ‘epistemic’ exercises involving either the spreading of knowledge and ideas through the sharing of expertise with stakeholders, or developing and refining how knowledge is shared from within the agency. This third area is half way between the previous two, and refers to recent research suggesting the role of unelected agencies is to constantly revise, update and reconsider policy on the basis of new information in close collaboration with stakeholders (Zeitlin Reference Zeitlin2015). Sabel and Zeitlin (Reference Sabel and Zeitlin2008) call this ‘experimentalist governance’, and it has had significant impact on how transnational agencies act – for example, ECHA (Biedenkopf Reference Biedenkopf and Zeitlin2015) and Frontex (Pollack & Slaminski Reference Pollak and Slominski2009). In practice, knowledge development and learning can include the creation of online or offline ‘training’ exercises that stakeholders can undertake to improve professional skills and possibly gain recognised certification (Broome & Seabrooke Reference Broome and Seabrooke2015). Internally, it covers consultation and reform exercises to revise and expand entrepreneurial methods. This aspect of entrepreneurship is important because it puts us in mind of just how far integrated some agencies have become with stakeholders. For many, entrepreneurialism is a matter of course and something they regularly do in a continuous ‘learning’ exercise, and this article seeks to capture this relationship and how far it is consistent across the range of EU agencies.

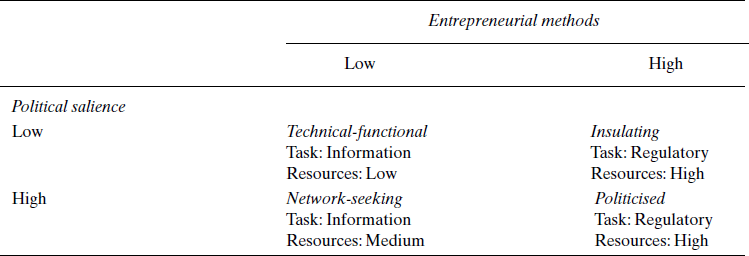

Mapping political salience against entrepreneurial methods based on a simple ‘high’ or ‘low’ score produces a two‐by‐two typology of entrepreneurial strategies. This typology develops Knill et al.’s (Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017) map of four ideal typical ‘administrative styles’ of IOs by comparing the ‘external institutional challenges’ an IO faces (‘political salience’ in our terms) with an IO's ‘bureaucratic policy ambitiousness’ (‘entrepreneurial methods’). Table 2 sets out the strategies, and this section then summarises the four types: technical functional; politicised; insulating; and network‐seeking.

Table 2. Typology of entrepreneurial strategies based on level of political salience and extent of entrepreneurial methods

Source: Adapted from Knill et al. (Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017: 66).

[Correction added on 16 March, 2018, after first online publication: Table 2 has been updated.]

A technical‐functional agency has low political salience and performs low on entrepreneurial methods. Knill et al. (Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017) call this the ‘servant’ type of IO, which they characterise using the UNESCO International Hydrological Programme. The Programme has ‘clear‐cut council structure and responsibilities, strong focus on technicality’. These types of IO, they argue, are characterised by ‘turf wars between sectors [that] severely hamper coordination; work overload due to reduced personnel; and the organization's mandate requires it to be, above all, a facilitator of science, not a policy enforcer’ (Knill et al. Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017: 66). This fits with the expectations we would derive from a low salience, less entrepreneurial EU agency, which would likely have low levels of funding and personnel, coupled with a limited remit around collecting and synthesising information, and as a result a very limited entrepreneurial strategy.

By contrast, a politicised agency has high levels of salience matched with high levels of entrepreneurship across all three dimensions. Knill et al. (Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017) call this a ‘policy and institutional entrepreneur’ type IO. For them, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is one example of this: ‘it is under constant political pressure from member states as well as societal groups and the media that it has to be very entrepreneurial … promoting policies that have a record of being successful’ (Knill et al. Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017: 66). Here, IOs have to fight on all fronts due to the perceived importance of their work and the pressure they receive for getting their recommendations and analysis right. This may apply especially to bodies with a potentially strong regulatory remit, such as those concerned with food or health regulation, where the EU has an especially strong role but still requires support from member states.

The other two ideal types of strategies are less clear cut, but in the case of insulating strategies there is a clear theoretical referent in the form of ‘credible commitment’ theory (Majone Reference Majone2001). These are bodies with high political salience, but with relatively few entrepreneurial methods, covering two or less of the three dimensions. Majone's famous argument that ‘non‐majoritarian’ institutions will provide legitimacy and authority for European governance as a result of their ‘output‐focused’ expertise, is played out in practice here, as agencies rely on their ‘independence’ for achieving authority. The assumption for these organisations is that if they do their jobs well as producers of expert technical opinions, they will be recognised as authoritative decision makers. Knill et al. (Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017) call this ‘institutional entrepreneurship’, in which agencies focus on ‘the quality, consistency and internal effectiveness of their policies’. ‘Bureaucracies of this type’, they argue, will emphasise ‘their role and self‐understanding as policy experts, while explicitly neglecting any strategic policy engagement’ (Knill et al. Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017: 66–67). These strategies will tend to be associated with agencies with large budgets and resources, high levels of political insulation and a strong regulatory mandate, with few international competitors.

Finally, network‐seeking agencies have extensive entrepreneurship methods but low levels of salience. For Knill et al. (Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017: 67), these are the ‘policy entrepreneurs’ that aim principally to ‘strengthen [their] political economy, status, size, and competencies. … The main interest is on the increase of competencies as such, that is, the growth of the policy portfolio is given precedence.’ The aim is hence to become integrated within ‘networks’ of relevant stakeholders, emphasising ‘mobilization and mapping of political space’. As many EU agencies are aimed at sharing information and even advocating for the evidence they provide, we may expect to see a number of agencies in this category. The agencies may be well resourced, but face severe competition in a crowded policy area (e.g., disease prevention) where a large number of transnational actors compete to set the global policy agenda.

Research process, methods and data

The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the applicability of the typology developed above to mapping EU agencies’ as political entrepreneurs. In doing so, it draws from a newly constructed database on the political salience and entrepreneurial methods of EU agencies (an Online Appendix will be uploaded to www.crickcentre.org upon publication of this article). Analysis of this database is complemented by semi‐structured interviews with officials in 11 EU agencies. This section explains and justifies the rationale of the typology in question, including the desirability of developing a conceptual typology and using an ordinal scale. It then goes on to outline how the dimensions of political salience and entrepreneurship were measured as well as how the validity and robustness of the data was ensured, before discussing the semi‐structured interviews used to validate the typology.

Conceptual typologies and ordinal data

It is useful to stipulate the purpose of the typology developed in this article, and the way in which the empirical data substantiates it. As Collier et al. (Reference Collier, LaPorte and Seawright2012: 228) define it, this article develops a ‘conceptual typology’ in that ‘(1) [t]he types are “a kind of” in relation to the overarching concept, and (2) the categories that establish the row and column variables provide the defining attributes of each cell type’. Here, two dimensions – political salience and entrepreneurial methods – are mapped as defining attributes of four entrepreneurship strategies. Critical commentaries on conceptual typologies have argued that they do not produce ‘systematic explanation’. This, however, overlooks how conceptual typologies can be used to construct important variables for utilisation in future explanations. Examples include ‘varieties of capitalism’ and national ‘administrative traditions’.

A key aspect of the typology is that it is developed through the construction of ordinal data on organisational entrepreneurship. Agencies are ‘scored’ along a scale based on a count of how many of the criteria of the (theoretical) dimensions under analysis they satisfy. This is mapped against ratio data of the average percentage of media and parliamentary attention agencies receive. While ratio variables tend to be more accepted due to having a ‘real’ zero, the approach of ordinal ‘ranking’ can be contested on the grounds that it sets up a false sense of ‘order’ and ‘obscures multidimensionality’. Hence, ‘with many presumably ordinal scales, the demonstration of order is questionable, and if one applies a strong standard, there are many fewer meaningful ordinal scales than is often believed’ (Collier et al. Reference Collier, LaPorte and Seawright2012: 219). This argument assumes that such ‘real’ ordering is in fact possible, but with various social science concepts this has not proved to be the case. The concept of ‘entrepreneurship’ is particularly slippery and difficult to measure in the first place – a task other scholars have tended to avoid. Hence, while a ratio variable would be preferable, this article adheres to a pragmatic approach where ordinal ranking serves the specific purpose of ‘bringing order out of chaos’ in organising an initial measure of this difficult concept (Bailey Reference Bailey1994: 33). Collier et al. (Reference Collier, LaPorte and Seawright2012: 219) state that ‘the idea of measurement should not be reified. … The real issue is whether the differentiation along dimensions or among cases serves the goals of the researcher.’ The purpose here is precisely this: to produce a typology of entrepreneurship strategies that serves an important descriptive and conceptual purpose.

Measuring entrepreneurship methods and political salience

The entrepreneurship methods of EU agencies were measured via an analysis of the annual activity reports to the Commission from 2014, the most recent year available at the time of data collection in December 2015. This year was also chosen specifically to map well against the political salience measures (see below), including media reports and parliamentary salience over the period 2009–2014. The 2014 reports show most clearly how an agency has responded to developments ‘filtering through’ in its wider political environment by adopting particular entrepreneurial methods. Each report was examined for evidence of all three aspects of the entrepreneurship methods dimension, media communication, face‐to‐face engagement, and learning and knowledge development, with six indicators:

Media communication

1 Website: Where there is evidence of the agency adding extra dimensions to its web presence (creating new website designs, a twitter account, etc.)

2 Traditional media: Where the agency has adopted or furthered a strategy for communicating more regularly with the media and public about its decisions

Face‐to‐face engagement

3 Events: Where the agency has held conferences, workshops and seminars for other national or EU agencies, professionals, consumers or companies

4 Collaboration: Where the agency has set up task forces or working groups with other agencies, professionals, consumers or companies

Knowledge development and learning

5 Training/learning: Where the agency has run an online or physical knowledge exchange session for professionals in its field of competence

6 Reform: Where the agency has conducted a survey, review or monitoring and improvement exercise on its stakeholder or communications strategy

This analysis produced a score for each agency based on how many criteria they fulfilled, which was termed their ‘entrepreneurial methods rating’ on a scale from 0–1. Coding was conducted by the author and a research assistant. The coders met to discuss any disputes resolved on the basis of the coding rules (see Online Appendix II). The author and research assistant coded 204 data points separately, and compared results. The intercoder reliability score Krippendorf Alpha was calculated to test coding reliability, as it provides a ‘strict’ test accounting for levels of disagreement expected by chance, and is useful for studies with fewer data points (Lovejoy et al. Reference Lovejoy2016: 1139). The score produced was 0.78. This is above the 0.7 level required for tough coding tests, especially for exploratory projects using new coding rules (Lombard et al. Reference Lombard, Snyder‐Duch and Bracken2002: 593; see Online Appendix V).

Political salience is measured following Koop's (Reference Koop2011) approach using data from media (newspaper) coverage of an agency and its prominence in EP debates. An original Lexis‐Nexis search was conducted for all mentions of an agency in English, French, German and Spanish newspapers for the period 2011–2014. Then existing data of agencies’ mentions in the 7th EP oversight questions from MEPs is used (from 2009–2014, drawn from Font and Pérez Durán's (Reference Font and Pérez Durán2014) dataset). Agency salience over the previous EP session and recent media reports (three years in the run up to when the entrepreneurship rating is generated) is averaged to produce an overall political salience rating for each agency. Following Koop (Reference Koop2011: 221), equal weight is given to media and parliamentary salience in a composite measure (see Online Appendix IV).

Elite semi‐structured interviews

The empirical analysis produced a graph of political salience rating against entrepreneurship methods rating (see Appendix I). The graph formed the basis for categorising each agency on the typology. At this stage, the choice of whether to place marginal agencies into the four boxes involved interpretation by the author. While an integer of 0.5 was included in coding to create the possibility of more than four types (a 3 × 2 typology), the agencies appeared to fit well into the fourfold typology, so analytical parsimony was maintained. Supporting these choices, evidence is used from a series of interviews with officials in 11 EU agencies. Interviewees were all officials in their respective agencies, with extensive knowledge of the agencies’ entrepreneurial methods. All interviews were between 30 and 90 minutes in length, transcribed by a research assistant, and interviewees were allowed to review and edit the interview transcript before it was used. Interviewees were promised anonymity; hence their role is anonymised to include only the agency name and date. The interviews themselves began with a broad set of questions that did not presuppose the categories in each typology (a list of interviewees and interview schedule is reproduced in Online Appendix III). Nevertheless, the data produced validates the distinctions in the typology, both for agencies that closely match the types and those that are marginal.

Empirical results

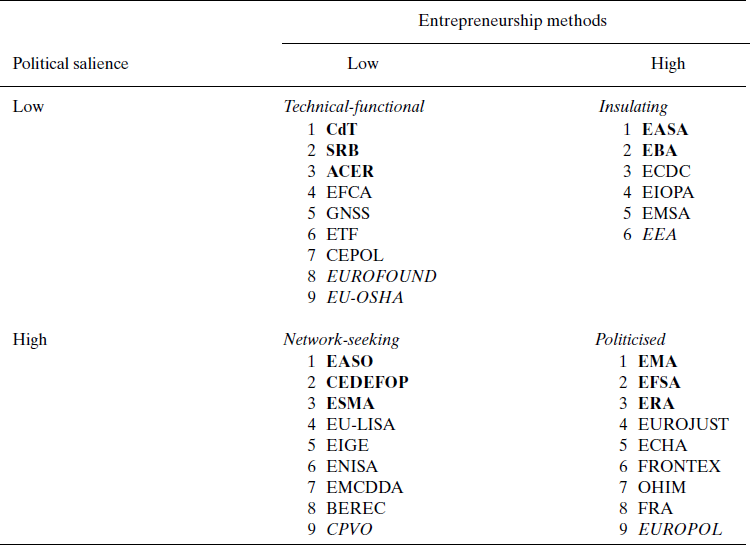

This section first describes the distribution of agencies across the two dimensions and then shows how they can be positioned within the typology developed in this article. Online Appendix II shows a distribution of entrepreneurial methods for 2014 across six dimensions. Scores were translated into increments of 1/12 (0.08333) for each agency (0 = least ‘entrepreneurial’, 1 = most ‘entrepreneurial’). The average score overall was 0.6, the highest score was 0.9166 (European Railway Agency, ERA) and the lowest was 0 (the Single Resolution Board, SRB). Mapping entrepreneurial methods (Online Appendix II) against political salience (Online Appendix IV) enables the placement of each of the agencies within the four typological categories identified by this article. Table 3 maps each agency onto the ideal types of entrepreneurial strategy identified in the theoretical section. Agencies in bold might be seen as the ‘ideal typical’ agencies that fit best into each category, while those in italics represent ‘borderline’ cases requiring further justification/exploration.

Table 3. Typology of EU agencies’ entrepreneurial strategies, 2014

Note: Agencies in bold might be seen as the ‘ideal‐typical’ agencies that fit best into each category, while those in italics represent ‘borderline’ cases requiring further justification/exploration.

Technical‐functional agencies have low entrepreneurial ratings and low political salience. There is little pressure for them to respond to external pressures for engagement, beyond basic responses required by their founding regulations. The Translation Centre for the Bodies of the European Union (CdT), for example, received 0.1 per cent of all newspaper mentions for EU agencies and 1.2 per cent of questions to agencies in the 7th EP. New agencies can take this form – for example the SRB, which in this period of analysis had only emergent activity matched by low salience in media and parliament. One interviewee from European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU‐OSHA) highlighted the typical approaches of these agencies:

Our primary audiences are intermediaries, people that can take our information and messages to the beneficiaries of our work in the EU's workplaces. We don't really expect to have direct communication with very many work places. And to aspire to do so, we'd probably just waste resources. So we're better off looking for those people and organisations that can act as intermediaries between us and actual workplaces. (Interview, EU‐OSHA official)

This quote highlights how constrained technical‐functional agencies are. EU‐OSHA itself is one of the smallest agencies, with only 65 members of staff. The reliance on ‘intermediaries’ suggests that while these agencies may wish to get a ‘message’ out (the interviewee often referred to ‘campaigns’ the agency runs), they will rely on other actors to do so for them and focus primarily on collecting and analysing information. Informal relationships with external organisations are crucial, but their capacity to expand those relationships means making important trade‐offs:

[W]hat we'll do is try and focus on improving the quality of [existing] relationships while not adding more in terms of numbers. The agency has very limited resources. … So, how can we be creative in terms of running things and maximising our technical resources? (Interview, EU‐OSHA official)

A similar approach can be seen in EUROFOUND, which produces research on employment and working conditions across Europe. An interviewee described how as a small agency they focus specifically on their task at hand: producing reports for the EP:

[W]e're a very small organisation – 100 people. To try and impact on that level across Europe, you could argue that it's practically impossible to ever achieve what everyone would want. But that's why it's important to define your goals. … that would be something that I think has worked well. So that when [EUROFOUND's] director goes to the Parliament, he's able to say, ‘We set out to do this and look, we've done this’. Now, if they come back saying, ‘We don't want you to do that anymore’, that's fine. That is fine because then we change. But then we need to know what it is. (Interview, EUROFOUND official)

This approach sticks quite rigidly to the original spirit of EU agencies as servants of the Community institutions (see Trondal Reference Trondal2010), fitting with Knill et al.’s (Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017) image of the ‘servant’ IO focused specifically on its core task and largely unable to expand beyond it. EUROFOUND itself is classified a marginal case, and the interviewee did note a desire to ‘reach out’ to wider European civil society. This desire, however, must be managed against resource constraints and demanding workloads:

By diverting resources to something that we're not sure we're going to reach, we can't afford to do that. We can decide that a little bit of that can be diverted to that to give it a go but, fundamentally, we need to maintain the core. And the core needs to keep working more and more effectively. (Interview, EUROFOUND official)

In sum, the technical‐functional agencies may desire to spread knowledge and ideas beyond their basic area of stakeholders – be more ‘entrepreneurial’ – but resource constraints mean they are heavily reliant on national level ‘multipliers’ to get any message out, and often choose to strategically focus on providing core Community institutions with required policy briefings and other information.

The network‐seeking agency has high levels of entrepreneurialism but low political salience. The European Asylum Support Office (EASO) is a good example, ranking low on media salience and receiving only 1 per cent of questions in parliament, but scoring a very high 0.9166 entrepreneurial rating. Agencies like EASO are termed ‘network‐seeking’ as they are attempting to raise their profile despite having less attention focused on them. The European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) is a clear example of a network‐seeking agency, focused on advancing gender equality through information dissemination. With only 27 members of staff, the agency is one of the smallest among the population. It has a very low profile in the political and public realms, being newly established in 2010. However, it also has ambitious aims for influencing European and even global public discourse, as an official from the agency put it:

[A] very important strand is making sure that those organisations that work on gender equality are actually aware of our work and that we work together with them. So this can range from other international organisations such as the United Nations, … Council of Europe, all of them with a strong mandate in the area of gender equality … it's quite challenging for such a small agency to reach out to all EU member states [and] to make sure that our evidence expertise [and] awareness raising tools are present in every national language in each member state. Civil society, through these EU‐level networks and their members, are important partners for that. We work a lot with multipliers, as [we ourselves are] not able to [be] present in every member state. (Interview, EIGE official)

This category therefore includes a number of agencies with small budgets and staff, and using ‘multipliers’ (the same with technical‐functional agencies), but with a strategic aim of expanding its networks and contacts. One agency on the borderline between ‘technical‐functional’ and network‐seeking is the Community Plant Variety Office (CPVO), which is in a transitional phase from being a largely managerial body, to promoting its policies more systematically. As one official put it:

There has been an evolution of stakeholder engagement over time. Previously we were focused on our core tasks, and the breeders [of different varieties of plants] were always observers of our business. Now the Commission want us to be more visible though. The Commission used to see us as having a technical role, now there's a much greater emphasis on engagement. (Interview, CPVO official)

As this quote suggests, network‐seeking may not be something that agencies are motivated merely by their own ‘entrepreneurial’ instincts to do, but by the Commission pushing them to seem more ‘relevant’ to the outside world. In the case of CPVO, as an agency funded by the plant breeding industry, the pressure also comes from firms keen to ‘know what's going on, what they're getting for their money’ (Interview, CPVO official). In this case, entrepreneurship is designed to maximise political influence, even to ensure agency survival in the face of termination threats.

The third type of strategy – insulating – includes the lowest number of agencies, clustered towards the bottom right of the graph in Appendix I. The European Banking Authority (EBA) is one of the ‘core’ agencies in this group. It is responsible for the EU‐wide ‘stress‐test’ of banks to protect against another financial crisis, and therefore has garnered significant media and EP attention. The way it has responded has been focused on internal policy coherence and, where necessary, aimed to ensure a coherent and consistent ‘message’ is communicated. As one interviewee from EBA stated:

We had a stakeholder engagement strategy in place, we developed a strategy, but it was really more on reacting rather than having the time to really proactively engage with them … you have all the important announcements like what to expect in terms of products or deliverables, what the EBA is working on, what will be published, and the key messages that we want them to convey. For some of the key topics that we identify that we're working on and which will be published, we identify key messages. Of course, we work closely with all the policy people to make sure that they provide us with the right input and then we work on the messages. (Interview, EBA official)

This quote demonstrates the essence of an ‘insulating’ approach, which aims to defend and maintain the agency's credibility with close internal cooperation and a clear ‘message’. EASA is another core example of an insulating agency. It receives substantial media coverage (15.1 per cent, ranked highest) and high parliamentary attention (6.5 per cent, ranked fifth) but also scores below average on entrepreneurship (0.5). An interviewee from EASA highlighted how the agency tended to be more ‘reactionary’ to any media story, using the example of the tragic Germanwings crash in 2015: ‘[I]t's a very dramatic and unfortunate event [but] well managed and handled by the agency. … We have been extremely reactive and we have been extremely prompt to react, to explain what our role was’ (Interview, EASA official). This was a development of the approach adopted following the crash of Air France flight 447 in 2009, which the interviewee described as relatively constrained: ‘At the time, we were still fairly unknown. We'd been around just over five years. … We were extremely quiet and we had a “no comment” approach’ (Interview, EASA official). This ‘reactive’ approach is complemented by a communications strategy that emphasises the generation of a coordinated and consistent response mechanism to any external enquiries:

[W]e have a communication strategy which we update on a yearly basis and this strategy aims at basically three things: [to] develop a greater awareness of the work of the agency, protect its reputation, and promote our values. Basically, in the details it describes what message we are going to convey so we try to fine tune our key messages on a yearly basis. (Interview, EASA official)

While there is an aim to ‘promote’ the agency further in terms of public knowledge about what it does, but the focus on ‘messages’ demonstrates a reactive approach primarily focused to responding to reputational threats. Insulating approaches also – as expected in the typology – exhibit a formalised and restrictive approach to meeting stakeholders in person and involving them in consultations, as one interviewee from EBA mentioned:

We even try as much as possible to informally meet some of the stakeholders. … The limit to that, and the risk, is that at some point, the more informal you go, the higher the risk of being lobbied … by the industry. Which is a red light for us. And this is something on which the European Parliament is required to be, I would say, vigilant at the moment. So, to avoid that … it's really technical input that we are looking for. (Interview, EBA official)

In contrast to the ‘network‐seeking’ agencies, which are keen to be involved with wider policy actors, this quote clearly shows a reticence to be involved in informal networks, seeking instead a more formalised approach that conforms to standards set by Community institutions. Such an approach is linked to the relative institutional autonomy and regulatory remit of the agency, which is greater than those ‘network‐seeking’ agencies primarily. In other words, stakeholders will take an interest in the agency because of its formalised responsibility for ‘stress testing’ banks by monitoring their resilience against market instability. A similar dynamic can also be seen in the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA), another economic regulator with strong legal mandate:

EIOPA is a very technical and legal body. … On insurance and occupational pensions there is an institutionalized stakeholder group, which helps with dialogue with academics, NGOs, industry, etc. There is a clear selection process for this group. They have to apply and a steering group appoints them for 2 and a half years. This can be renewed. It checks conflicts of interest, and ensures geographical and gender balance. There have to be not too many candidates. They meet four times a year. (Interview, EIOPA official; emphasis added)

This formalised process, including sub‐committees on insurance and reinsurance and occupational pensions, was required of EIOPA in its founding regulation, and provides feedback that the agency must take into account in its regulatory activities. While the interviewee noted the desire to ‘build a regulatory culture’, the formal committees were seen as central in achieving this, rather than informal communication.

EIOPA's approach to media communication, similar to EBA, is also limited to managing risk through a tight messaging campaign. ‘Your message should always be the same. You need to get to your audience on board’ (Interview, EIOPA official). This tight link to specific messages, the interviewee suggested, was due to the significant consequences any misinformation could have on the confidence of regulated markets: ‘It is all about confidence. If you lose it you are lost. … The action has to fit the talk. You have to be responsible for how and when you do what you do’ (Interview, EIOPA official).

However, insulating strategies are not limited to those with strong regulatory mandates. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), which is a ‘coordinating’ agency with no formalised regulatory remit, comes under this category as well. ECDC has relatively high media coverage for an information‐focused agency (2.6 per cent media coverage and 1.7 per cent parliamentary attention), and rates below average (0.5) on entrepreneurial methods. Its main focus is on coordinating with national‐level authorities, and in 2014 identified information communication technologies as vital for ‘efficiently and effectively supporting the Centre's ICT needs for internal, Commission and Members States users’. This aim of servicing the member states and Commission took priority in the ECDC's work over media engagement, face‐to‐face networking and knowledge development and learning – a key feature of a less entrepreneurial agency.

Interview data from the European Environment Agency (EEA) also demonstrates that credibility‐seeking can extend to ‘information’ agencies. EEA's primary purpose is to develop and distribute evidence on environmental standards comparing member states, by coordinating Eionet, the European regulatory network on the environment. This involves organising and participating in workshops and disseminating reports (e.g., on the environmental quality of beaches) via social media. This communicative focus is, however, offset by the need to maintain objectivity:

For us, co‐creation is increasingly important, we already work with external people but directly creating products and research with them is the future. There is a strong need to engage with this in the future. However there is also a big risk involved in this, about maintaining reliability and objectivity in our work while also working closely with external bodies. … We are aware co‐creation produces greater impact from a study or assessment – you reach a wider audience – but independence and reliability are crucial. The topic and the role you play is important – for example air pollution and climate change have been politically relevant topics and need to be approached with caution. (Interview, EEA official)

As this quote makes clear, insulating agencies do not object to working with external actors. Indeed, the importance of ‘co‐creation’ as described by the EEA official can be important for their functioning. Nevertheless, the competing pressures to maintain perceptions of objectivity mean that entrepreneurial activities take a backseat to the production of credible information and opinions.

Finally, politicised agencies, to repeat, are highly politically salient and have a relatively wide range of entrepreneurial methods. The European Food Safety Agency (EFSA), for example, receives over 25 per cent parliamentary attention and 7.8 per cent media coverage, and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) ranks top ten for media and parliamentary salience (averaging third highest salience rating overall). Both agencies have entrepreneurship scores above average (see Online Appendix II). These agencies are concerned to engage a wide range of stakeholders in light of their high levels of visibility. One interview talked about EMA's ‘expansive’ approach to including a diversity of stakeholders:

The agency developed across the years, really, a kind of increasing engagement with stakeholders and [was] actually always trying to, at different stages, find out what stakeholders wanted to do and kind of adapted its way of working through the years. So I think the most recent innovation in a way was the integration of patients and handicapped professionals into the committee decision‐making of the Committee for Medicines for Human Use, which is a new stamp of stakeholder engagement. (Interview, EMA official)

This approach is closely linked to the salience of the agency within the politicised realm of medicines provision. This was characterised in terms of ‘risk management’, which the EMA is constantly involved in communicating:

People became aware that, as patients are the ultimate beneficiaries of what we are doing, they have a different perspective, for example, of benefit‐risk (how much risk they want to take with a certain medicine) which is probably different from a purely scientific view because, depending on where you stand and what your personal situation is, the assessment will be quite different. … We try more to reassure and to ensure that we are taking the right measures to ensure that everything is safe rather than talking about the risks. The key message we try to deliver is that the risk is always well‐managed. (Interview, EMA official)

Credibility is important for politicised agencies, but it is managed in a more outward‐facing way than in insulating agencies. As interviewees from ECHA, EMA and EUROPOL noted, credibility is vital to agencies’ authority. At ECHA, the ‘objectivity’ of the REACH scheme was viewed as ‘crucial’ to ‘how stakeholders perceive us’ (Interview, ECHA official). However, as interview evidence again makes clear, the core aspect of a ‘politicised’ approach is a proactive response to risk communication that actively coordinates contact with stakeholders who are not immediately accessible:

We have already started … to be much more proactive, have more organised press briefings with people … we normally do this virtually in workshop briefings because as Europe is big, people can't necessarily come here. We also want to allow, for example, American journalists … [so] we normally do it early afternoon. We have this direct exchange where journalists can also ask questions to experts. We do this more proactively and this has had quite a big impact because it increased, again, the visibility … in more media queries. (Interview, EMA official)

Hence, for entrepreneurial agencies ‘entrepreneurship’ expands their range of contacts, making them more ‘visible’, rather than seeking to manage that visibility and restrict the groups they come into contact with. For EUROPOL, there is a desire to expand their reach in order to ensure the public and media knew more about transnational policing strategies and the different levels they should report transnational crime. The key difference from network‐seeking agencies here is the intensive media and public spotlight they tend to come under:

A lot has changed in the past few years. In 2008 nobody knew what EUROPOL was, today we are all over the news. … There was never a question that we didn't want to communicate. We were a young organisation, 8 years ago we had 4,000 cases, now we have 40,000 cases. All member states are now using us. The environment has clearly changed … we have been proactive in communicating and giving information. (Interview, EUROPOL official, emphasis added)

Politicised agencies adopt a similar approach to network‐seeking agencies in going beyond their formal remit for communication and risk management, but the key distinguishing feature is that they do so in a strategic context focusing on extending their capacity and reach in an already challenging political context. This is particularly important following ‘hot’ crises like the shootings at the Charlie Hebdo magazine offices in Paris in 2015, as well as more gradual tasks of informing and educating the public:

Risk and prevention underlies all the communication we do. This involves either highlighting new risks, for example giving advice to ministers on where they should put resources. We also need to inform the public, so we highlight crime assessments to the public in collaboration with member states. In this regard, we can use issues in the limelight to talk to the public about prevention, for example on preventing everyday citizens being victims of crime. One example of this is making sure citizens pay attention to the sort of products they buy, or viruses and phishing emails. (Interview, EUROPOL official)

Risk management is a crucial aspect of politicised agencies’ work. EFSA and ECHA, for example, are constantly involved in ongoing controversies over genetically manufactured foods and chemicals that require reaching out to the European public to communicate health risks.

Discussion and conclusion: Developing the typology

This article is the first exercise in systematically mapping EU agencies as political entrepreneurs. While existing research has tended to focus on accountability and autonomy dynamics, this article focuses on how agencies practically navigate their political environments through a broader or narrower set of entrepreneurial methods in a context of differing levels of political salience. It has done so by connecting EU agencies literature with a TPA framework (Knill et al. Reference Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017), which is useful because of its acute understanding of the informal ways in which supranational organisations claim authority through political entrepreneurship (Moravscik Reference Heims2016). The article has brought together literature on political salience, mediatisation, epistemic communities and learning, creating a distinctive analytical framework for studying a tricky and multifaceted concept. The key result is the validation of a typology of four entrepreneurial strategies: technical‐functional; insulating; network‐seeking; and politicised. This concluding section reflects on the typology's limitations, benefits and future developments.

First, the typology is useful principally because its empirical findings enable the conceptualisation of a crucial, yet previously imperceptible feature of EU agencies: their approaches to achieving informal authority within a fluid and diverse transnational policy environment. It provides a firm basis for positing hypotheses about what determines the adoption of one strategy over another; focusing, for instance, on size, resources of the agency, its financial or policy autonomy, or requirements for accountability (Wonka & Rittberger Reference Wonka and Rittberger2010). Second, and linking to existing literature, the typology adds to existing knowledge about the differential approaches of agencies to achieving authority. Complementing existing typologies of differing accountability structures and levels of autonomy, the article develops an encompassing set of measures of political entrepreneurship. Third, and in terms of political science literature on agencies more broadly, the typology contributes towards an agenda on the ‘public communication’ of agencies, and their potential democratic value. Puppis et al. (Reference Puppis2014: 389) state that ‘it can be argued that communication contributes to the accountability of regulatory agencies and might eventually help them to mitigate their inherent democratic deficit’. The analysis in this article suggests, at the EU level, divergence between agencies on the extent of their communication. This could be mapped against indicators of accountability to show whether different communication strategies enhance accountability and democratic quality.

These benefits are, of course, tempered by some limitations. The first is that the data covers only one year, whereas further data covering multiple years for each agency would provide a dynamic picture of agencies moving between the four categories identified here. This may also enable the typology to be refined to cover the history of different agencies, rather than simply positing one type of entrepreneurial strategy at a specific moment. Second, the creation of an ordinal scale, while justified in this case as a necessary framing device, clearly risks simplification. Media communication, face‐to‐face networking, and knowledge development and learning practices are not homogenous and could have divergent qualitative value for different agencies. Treating them as equal may therefore gloss over important nuances that qualitative research would uncover. To account for such nuances here, agencies were coded 0.5 where activities were either partial or seemed functional aspects of standard agency practice (see the coding schedule in Online Appendix II). While this enabled a successful exercise in typology‐building, it could be innovated through a more sophisticated measure for each aspect of entrepreneurship, incorporating a fine‐grained scale for each. This limitation may also apply to political salience, which currently gives equal weight to traditional media and EP salience. However, some agencies may give substantial attention to their media image rather than EP attention, or vice versa, which may impact upon where they can be placed on the typology.

Finally, further research should test hypotheses on whether entrepreneurial strategies are successful in shaping the views of agency audiences. As existing research on reputation suggests, audience ‘images’ of agencies are shaped by these informal strategies (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2010). But how in particular does this interaction function? Do audiences demand more politicised or technical‐functional strategies? How do certain strategies affect agency audiences? Are audiences content with an agency being ‘technical’ and see ‘politicised’ entrepreneurship as damaging what they expect from a discrete technical body not interfering in the wider political world? Alternatively, do audiences demand greater openness, accessibility and interaction? Which aspects of entrepreneurship do audiences demand, and do agencies meet those expectations? This article marks a starting point for a research strategy looking at this interaction.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges funding from the Economic and Social Research Council funded project ‘New Political Spaces? Enhancing the Legitimacy of Delegated Agencies’ (grant no. ES/L010925/1). Sincere thanks go to the interviewees, and Lucy Parry and May Anne Hill for valuable assistance with coding and interview transcription. Any remaining mistakes are those of the author.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Appendix II: Table 4.2: EU Agencies’ Entrepreneurial Methods (2014)

Appendix III: Interview Schedule for semi‐structured interviews with EU agency elite managers

Appendix IV: Political salience scores

Appendix V: Inter‐coder reliability

Appendix I: Mapping organisational entrepreneurship and political salience

[Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Source: Constructed by the author from data in Online Appendices II and IV.