Stigmatisation has been defined as ‘one of the main obstacles to the electoral and political success’ of populist radical right (PRR) parties in Western Europe (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007, p. 245).Footnote 1 First, it can deter citizens from voting for these parties (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Dahlberg, Kokkonen and van der Brug2017; van Spanje & Azrout, Reference van Spanje and Azrout2019). Second, it creates obstacles to the recruitment and retention of grassroots members, which in turn hinders the party's electoral prospects (Art, Reference Art2011; Klandermans, Reference Klandermans and Mudde2016). In fact, the stigma ascribed to PRR party membership implies severe social and material costs, which can include isolation from family and friends, and loss of job opportunities (Klandermans & Mayer, Reference Klandermans and Mayer2006; Stockemer, Reference Stockemer2014). Therefore, those rank‐and‐file who join stigmatised PRR parties are said to be mostly people who are not susceptible to such costs (Art, Reference Art2011). This body of work on PRR stigmatisation, however, has taken parties as units of analysis, rather than focusing on individuals. In this article, I adopt a different approach, and study stigmatisation by looking at PRR grassroots members. Rather than assuming that these people will be similarly oblivious to stigma, I investigate whether they differ in this regard. Specifically, I ask Which PRR party members are more likely to feel stigmatised?

To date, scholars have proposed that being susceptible to stigma is determined by two factors: ideological position and socio‐economic status (SES). The argument goes that extremist people, as well as those with low SES, will find the stigma which characterises PRR party membership less discrediting (Art, Reference Art2011). However, there has been little empirical evidence to sustain these claims, and the mechanisms which underpin them are unclear. In this article I argue that, since stigma is socially constructed, feelings of stigmatisation may depend on the personal networks in which PRR grassroots members are embedded. In particular, I contend that whether PRR rank‐and‐file will be susceptible to stigmatisation is likely to be predicated on the political views prominent among (1) their family and friends; (2) acquaintances in their wider social circles; and (3) colleagues at work. These views can be gauged by examining whether PRR grassroots members have ever had any relatives or friends in the party, and by proxies such as their educational level and their employment sector. I test this argument with a membership study of the Sweden Democrats (SD), a typical case of a PRR party which has passed from the fringe to the centre of its country's political landscape (Jungar, Reference Jungar, Heinisch and Mazzoleni2016; Rydgren & van der Meiden, Reference Rydgren and van der Meiden2018). Adopting a mixed methods research design, first, I draw on an original nationwide membership survey of about 7,000 SD grassroots members (the largest survey conducted of any contemporary PRR party) to investigate which members are more likely to feel stigmatised; second, I use online interviews with 30 of them in the counties of Skåne and Stockholm to inductively build a theory of feelings of stigmatisation.

The survey results show that education is the strongest predictor of feelings of stigmatisation. The higher the educational qualification PRR grassroots members have achieved, the more likely that they will feel stigmatised. Furthermore, those who have never had any relatives and/or friends in the SD, and those who are employed in the public sector, are more likely to consider SD membership as discrediting. By contrast, ideological self‐placement, being outside the workforce and economic well‐being have no impact, countering the idea that those who are not susceptible to stigma will be mostly extremist and low‐SES individuals (Art, Reference Art2011). The interview data shed light on these findings, by highlighting how the different personal networks which PRR party members find themselves in are key to understanding stigmatisation. They illustrate how PRR grassroots members who work in the public sector or are enrolled in university find it hard to be open about their membership because they are surrounded by colleagues and acquaintances with left‐wing views. On the other hand, having relatives and/or friends who are members of the party reduces the stigma of joining PRR parties in the first place, of becoming active in them and of discussing politics and current affairs.

This article makes several contributions to the study of PRR parties, and that of party membership more generally. Theoretically, it shifts the focus from stigmatisation of PRR parties to stigmatisation of PRR party members. Furthermore, it proposes a novel theoretical explanation for stigmatisation which relates to the social and professional networks of these individuals. Methodologically, this is the first study of (PRR) party membership which combines a large‐scale survey with in‐depth interviews with grassroots members. As such, not only does it allow us to test a new theory through the survey, but it also brings additional insights and uncovers ‘the dynamics of membership involvement’ thanks to the interviews (van Haute & Gauja, Reference van Haute and Gauja2015, p. 199). Empirically, this article addresses an overlooked topic in the literature on PRR party family and its organisation, namely PRR grassroots membership (Castelli Gattinara, Reference Castelli Gattinara2020, p. 322; Mudde, Reference Mudde2019, p. 76). In addition, it counters some of the prevailing wisdom about stigmatisation among PRR rank‐and‐file, and explores a dimension of party membership that has been neglected by scholars: what the experience of membership means to individuals (Gauja, Reference Gauja2015, p. 244).

Stigmatisation among PRR party members

Stigmatisation, understood here as the process through which a party is designated as illegitimate and a danger to the political system (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2022), has long characterised the PRR party family, especially those parties whose legacy lies in extremist and racist ideologies and movements (Art, Reference Art2011). Because of their nativist agendas, PRR parties are perceived as violating a strong social norm that citizens in Western democracies have internalised since the end of the Second World War – the norm of not discriminating against ‘out‐groups’ defined on the basis of their ethnicity and/or religion (Blinder et al., Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013). As a result, these parties tend to be stigmatised by a range of actors, including other parties, media and society at large. First, stigmatisation may take the form of a cordon sanitaire, with parties refusing to cooperate or enter coalitions with PRR parties. Second, the media can stigmatise PRR parties either by erecting a cordon médiatique, that is, refusing to offer a platform to parties, or by casting them as illegitimate in their coverage (de Jonge, Reference de Jonge2019). Finally, stigmatisation can occur at the societal level, with PRR candidates and grassroots members facing significant social and material costs, such as exclusion from their social environments, and loss of jobs or employment opportunities (Klandermans & Mayer, Reference Klandermans and Mayer2006; Stockemer, Reference Stockemer2014). Evidence of societal stigmatisation is not limited to memberships of politically marginalised PRR parties; on the contrary, it has also been found among rank‐and‐file of PRR parties which are considered legitimate actors in their political systems, like the League in Italy (Biorcio, Reference Biorcio1997; Zulianello, Reference Zulianello2021). Relatedly, even though cordons sanitaires and cordons médiatiques may weaken or break, this does not necessarily mean that a PRR party is no longer stigmatised at the societal level (Bolin et al., Reference Bolin, Dahlberg and Blombäck2022).

As Mudde (Reference Mudde2007, 247) wrote, the ‘detrimental effects’ of stigmatisation on the electoral outcomes of PRR parties ‘are both direct and indirect’. Directly, stigmatisation can deter citizens from voting for a party. Recent work on negative partisanship in Western Europe has revealed how half of the electorate displays a stable psychological repulsion towards PRR parties, limiting their potential for electoral growth (Meléndez & Kaltwasser, Reference Meléndez and Kaltwasser2021). Their electoral support can be further hindered by ‘demonising’ media coverage (van Spanje & Azrout, Reference van Spanje and Azrout2019). Moreover, in dozens of European countries, the stigma associated with PRR parties has been found to partly explain why women are less likely than men to vote for them (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Dahlberg, Kokkonen and van der Brug2017; Oshri et al., 2022). Indirectly, stigmatisation can negatively affect PRR party organisation, which is considered a key factor in sustaining their electoral breakthroughs (Loxbo & Bolin, Reference Loxbo and Bolin2016) and persistence (Art, Reference Art2011; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007). In particular, stigmatisation creates obstacles to the recruitment and retention of grassroots members (Art, Reference Art2011; Klandermans, Reference Klandermans and Mudde2016), who cover important linkage and mobilisation functions, and represent the first pool of parties’ personnel and candidates.

To date, scholars have proposed that being susceptible to the stigma of PRR party membership is influenced by ideological and socio‐economic factors. In particular, in his book on PRR party organisation in 12 Western European countries, Art (Reference Art2011) argues that given the social and material costs of joining PRR parties, those individuals who become members ‘normally fall into two categories: extremists, who have no problem flouting social norms, and those who have little to lose in terms of employment and social relations’, that is, people with low SES (ibid., p. 47).Footnote 2 In other words, extremists and low‐SES individuals are said not to care about the stigma, whereas moderates and higher‐SES individuals do. Art (Reference Art2011), however, does not provide systematic empirical evidence for these claims, and the mechanisms underpinning them are unclear. Ideological and socio‐economic explanations of PRR stigmatisation overlook how stigma, understood as ‘an attribute that is deeply discrediting’ (Goffman, Reference Goffman1963, p. 3), is a social construction. Specifically, stigma is constructed when (1) people identify and label differences which are socially salient (e.g., identify what PRR supporters stand for); (2) they link those labelled differences to stereotypes (e.g., PRR supporters are neo‐Nazi); (3) they separate themselves, who do not share the label, from the stigmatised (e.g., ‘we' support democracy, ‘they' oppose it); and (4) the outcome of these three mechanisms (labelling, stereotyping and separation) results in status loss and discrimination of the stigmatised (Link & Phelan, Reference Link and Phelan2001; see also van Spanje & Azrout, Reference van Spanje and Azrout2019, p. 288). Whether a certain collective identity is discredited, therefore, depends on the reaction of others in a determined social context (Crocker et al., Reference Crocker, Major, Steele, Gilbert, Fiske and Lindzey1998).

Given the inherently relational nature of stigma, in this article I offer a novel theoretical explanation for feelings of stigmatisation among PRR grassroots members which focuses on social factors. In particular, I argue that PRR party membership will be more or less discrediting depending on the personal networks in which PRR rank‐and‐file are embedded. In doing so, I further depart from the work of Art (Reference Art2011) in that I shift the analytical focus from PRR parties to PRR grassroots members. In his view, once a party is stigmatised by other parties, the media, and in society, it can be inferred that those who join it are largely unaffected by the party's stigma. In this article, by contrast, rather than taking PRR party memberships as monolithic blocks and assuming that they consist mostly of individuals who do not care about stigma, I examine whether grassroots members actually differ in this regard, that is, whether some feel more stigmatised than others. In addition, I am interested in whether PRR party members feel stigmatised, rather than whether they actually are, because for PRR grassroots members to be actually stigmatised, their membership needs to be revealed. However, this may not be the case for an important section of party members who join political parties just to provide passive/silent support (Heidar & Kosiara‐Pedersen, Reference Heidar, Kosiara‐Pedersen, Heidar, Demker and Kosiara‐Pedersen2020; van Haute & Gauja, Reference van Haute and Gauja2015), and are nonetheless affected by the stigma of PRR party membership.Footnote 3

The departure point of my theoretical framework is that the choice of joining and being active in a party is partly influenced by social norms, that is, by how political participation is perceived by ‘significant others’ whose opinions the (potential) member values and respects (Whiteley & Seyd, Reference Whiteley and Seyd1996, p. 221). These ‘significant others’ can span from the closer networks of family and friends to the wider ones including acquaintances and colleagues. In the remaining part of this section, I develop three expectations regarding how these networks can foster or hinder feelings of stigmatisation surrounding PRR party membership. In particular, I expect that whether PRR rank‐and‐file will be susceptible to stigmatisation is likely to be affected by (1) whether they have had any relatives or friends in the party, who thus share their same political views; (2) their educational level, which is a proxy for the political views expressed in their wider social circles; and (3) their employment sector, which is a proxy for the political views expressed at work.

Firstly, despite the fact that party members in Western democracies rarely join because of the influence of relative and friends (Heidar & Kosiara‐Pedersen, Reference Heidar, Kosiara‐Pedersen, Heidar, Demker and Kosiara‐Pedersen2020; van Haute & Gauja, Reference van Haute and Gauja2015), political attitudes and behaviour, including partisanship, are heavily shaped by discussions we have within these close personal networks. For instance, family has been described as ‘the most important socialization agency’ for far‐right party members, whose path towards membership is often encouraged by grandparents and parents (Klandermans & Mayer, Reference Klandermans and Mayer2006, p. 270; Stockemer, Reference Stockemer2014). Given the normative concerns that support for these parties raises (Blinder et al., Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013), I expect that those individuals who have been socialised in an environment favourable to PRR politics, and had close contacts in the party when joining, will be less concerned by stigmatisation than ‘self‐recruits’, who lack this background. Similarly, those grassroots members who currently have some relatives and/or friends that joined the party since they did, will consider their membership less burdensome.

H1: PRR party members who have had relatives and/or friends in the party will be less likely to feel stigmatised.

Beyond this closer network, it is plausible that feelings of stigmatisation among PRR rank‐and‐file will be affected by the political views shared by acquaintances within their wider social circles. These views can be gauged by taking the educational level of PRR party members as a proxy. In fact, research in sociology has long illustrated how, when building their personal networks, individuals follow the ‘homophily’ principle, that is, they establish relationships with people similar to them according to key socio‐demographic characteristics, including education (McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Smith‐Lovin and Cook2001). Individuals with similar educational levels tend to interact and marry more frequently, especially those at the lowest and highest extremes of the education distribution (Marsden, Reference Marsden1988; Smith et al., Reference Smith, McPherson and Smith‐Lovin2014). Accordingly, one can expect that, for highly educated PRR party members, there will be less people in their social networks who sympathise with their political activities. In fact, education has been found to be a strong predictor of PRR support. Studies have shown that people with a university education are the least likely to vote for PRR parties, while citizens with lower levels of education tend to be overrepresented among PRR voters (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer and Mudde2016). Consequently, if we take the educational level of PRR grassroots members as a proxy for the political views prominent in their social circles, those with lower educational attainments will be more likely than those with a university degree to be surrounded by friends and acquaintances sharing their views. Therefore, they ought to be less susceptible to the stigma which characterises their membership.

H2: The higher the educational level of PRR party members, the more likely that they will feel stigmatised.

Finally, PRR rank‐and‐file may also be sensitive to social cues from their colleagues at work. In this regard, following a similar logic to the one leading to H2, I expect some working environments to be less favourable than others to revealing one's membership of a PRR party, meaning that the sector in which PRR party members are employed will likely affect feelings of stigmatisation. Specifically, even if the employment sector is not as strong a predictor of vote choice for PRR parties as it is for other party families (Knutsen, Reference Knutsen2005, p. 617), we know that PRR voters have been consistently underrepresented among public sector employees (Betz, Reference Betz1994; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, van der Brug, Dahlberg and Kokkonen2015). By the same token, studies have observed that public sector employees in Western democracies are more inclined to vote for parties of the left, especially if they work in health and education (Knutsen, Reference Knutsen2005; Tepe, Reference Tepe2012). It follows that PRR party members employed in the public sector will likely be surrounded by colleagues who share opposite ideological and programmatic views – almost certainly to a larger extent that those employed in the private sector, or the self‐employed. As a result, I predict that they will find their membership in a PRR party significantly more discrediting.

H3: PRR party members working in the public sector will be more likely to feel stigmatised.

Case selection, methods and data

I test my hypotheses about feelings of stigmatisation on the grassroots membership of the SD. The SD was formed in 1988 from Sweden's extreme right milieu. For almost two decades, this highly compromising legacy limited the electoral impact of the party (Widfeldt, Reference Widfeldt2008). In fact, despite efforts to clean its image, for instance by banning political uniforms at meetings and publicly disowning Nazism, it remained irrelevant on the national stage until mid‐2000s – although it did gain some seats in local councils (Widfeldt, 2008). In 2005, the SD youth wing leader, Jimmie Åkesson, became party leader, a position that he has held ever since. Under Åkesson, the SD was met with increasing media interest and became involved in public debates with other political forces, which until then had ignored the SD (Hellström et al., Reference Hellström, Nilsson and Stoltz2012). Åkesson worked towards increasing the party's respectability in the eyes of the Swedish public ‘by moving toward ideological moderation and enforcing greater party discipline’ (Jungar, Reference Jungar, Heinisch and Mazzoleni2016, p. 210). The growing popularity and media interest in the SD paved the way for the party's electoral breakthrough at the 2010 general election.Footnote 4 In 2012 it introduced what it called a ‘zero tolerance for racism’ policy, which resulted in numerous expulsions of grassroots members over the following years (Rydgren & van der Meiden, Reference Rydgren and van der Meiden2018). Since then, the SD has grown into the third largest political force of the country, steadily improving its parliamentary representation at both the 2014 and 2018 general elections where it gained 49/349 and 62/349 seats, respectively.

Following its breakthrough, Sweden's mainstream right parties established a tight cordon sanitaire against the SD, refusing to collaborate with it even when this cost them remaining in office in 2014. This lack of cooperation has been the result of both strategic considerations of Sweden's mainstream parties in their pursuit of policy, office, and votes (Backlund, Reference Backlund2022), and the SD's extreme right history (McDonnell et al., Reference McDonnell, Werner and Karlsson2021). However, already in 2014 the SD acquired de facto ‘absolute blackmail potential’, meaning that since then it has become difficult to ignore it when assembling a parliamentary majority (Jungar, Reference Jungar, Heinisch and Mazzoleni2016, p. 209). Since 2021, moreover, the mainstream right front has been expressing greater openness to some kind of cooperation with the SD (Jupskås, Reference Jupskås, Bale and Rovira Kaltvasser2021, p. 268). This party thus represents a clear example of how, in the electoral arena, stigmatisation is not a permanent condition, but rather is ‘a spectrum across which parties can move depending […] on how dangerous and/or illegitimate they are seen’ (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2022, p. 391). In this sense, the SD represents a typical case of a PRR party, since it has passed from being a force on the fringe of its country's politics to gaining more prominence in the public debate in tandem with the increasing salience of immigration (Jupskås, Reference Jupskås, Bale and Rovira Kaltvasser2021; Rydgren & van der Meiden, Reference Rydgren and van der Meiden2018).

To examine which PRR party members are more likely to feel stigmatised, I conducted a nationwide online survey of the SD grassroots membership, as well as online interviews with 30 members in two Swedish counties. Specifically, I first assessed which PRR party members were more likely to feel stigmatised through the membership survey, and then used the interviews inductively to build a theory of feelings of stigmatisation. The decision to adopt a mixed methods approach was based on a number of reasons. On the one hand, research on far‐right parties and movements has mostly relied on interviews and ethnographies to study membership (Castelli Gattinara, Reference Castelli Gattinara2020).Footnote 5 In comparison to secondary sources, such methods ‘provide a better understanding of the workings of far‐right groups and the beliefs and motivations of their activists’ (Blee, Reference Blee2007, p. 121). However, most of these studies ‘are based on interviews with an unrepresentative sample of more dedicated members’ (Mudde, Reference Mudde2019, p. 76), limiting the generalisability of their findings. On the other hand, surveys have become ‘the dominant methodological tool’ in party membership research, and are used to investigate who are party members, why they join, and what they do (van Haute & Gauja, Reference van Haute and Gauja2015, p. 200); yet, while surveys do overcome questions of generalisability, they are not able to provide an in‐depth account of what the experience of membership means to individuals (Gauja, Reference Gauja2015, p. 244; van Haute & Gauja, Reference van Haute and Gauja2015, p. 199). Using both the membership survey and qualitative interviews thus allowed me to address these methodological concerns.

Between October and December 2021, I conducted a nationwide online survey of the SD party membership. Despite the well‐known difficulties of gaining access to political parties for membership surveys, especially among PRR parties (Art, Reference Art2011, p. 53; Gauja & Kosiara‐Pedersen, Reference Gauja and Kosiara‐Pedersen2021, p. 11), the survey was conducted with the full cooperation of the party secretariat. The latter first distributed the link to the survey via mail to the whole membership (which, according to the party, consists of approximately 36,000 people), and then followed up with two reminders. In total, 9,177 grassroots members started the survey, which constitutes a high response rate (25 per cent) in comparison to other studies of party membership, including in Sweden (see Kölln & Polk, Reference Kölln and Polk2017). This makes it also the largest membership survey of a contemporary PRR party.Footnote 6 For the purposes of this article, the analysis was conducted on the 6,934 SD grassroots members for whom information on all the variables of interest was collected.Footnote 7

The dependent variable, feelings of stigmatisation, was measured by asking respondents the extent to which they agreed with the following survey item: ‘It is not easy to publicly admit that I am a member of the Sweden Democrats’. They could choose between answer options on a 4‐point Likert scale (‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘agree’, ‘strongly agree’, and ‘don't know’). I coded this as 0 if party members disagreed or strongly disagreed with the sentence, and 1 if they agreed or strongly agreed.Footnote 8 One could argue, drawing on Goffman's (Reference Goffman1963, p. 3) definition of stigma as ‘an attribute deeply discrediting’ (emphasis added), that only those who ‘strongly agree’ with the statement should be considered as feeling stigmatised. However, I contend it is problematic to group together those who ‘somewhat agree’ that they feel stigmatised with those who do not, since these groups of respondents are expressing two reactions to their party's reputation that are substantially different. In doing so, I nonetheless acknowledge that my dichotomisation of the dependent variable implies a lower bar of feeling stigmatised than that defined by Goffman.

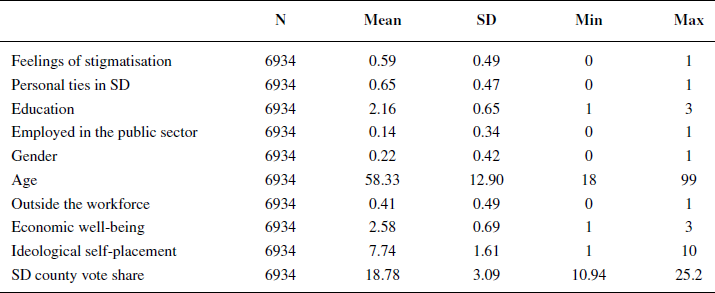

The first independent variable, personal ties in the SD, was measured by asking respondents four questions: the first two on whether at the time they joined, anyone in their immediate family or among their friends was a member of the SD; and the second two on whether, since they joined, anyone in their immediate family or among their friends had become a member of the SD. They could choose between three answer options (‘yes’, ‘no’, and ‘don't know’). I coded this as 1 if they have ever had relatives and/or friends who were SD party members (i.e., if they answered ‘Yes’ to any of the four questions), and as 0 if they had no one, or did not know. The second independent variable, education, was gauged by asking party members their highest educational qualification. Responses were grouped into three categories: 1 = up to ninth grade; 2 = upper secondary education; 3 = tertiary education.Footnote 9 The third independent variable, measuring whether respondents were employed in the public sector, was a dummy variable created by asking them about their occupational status, and was coded as 1 if they were public employees, and 0 if they were not. In addition to these predictors, I included a number of controls, which are shown in Table 1 and described in the Supporting Information Appendix C.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

To assess the statistical effects of the variables identified above on feelings of stigmatisation among PRR party members, I performed a logistic regression model. I computed robust standard errors clustered at the county level, to account for the non‐independence of observations within the same county. To evaluate whether a multilevel model would provide a better fit for my data, I calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Following Heck et al. (Reference Heck, Thomas and Tabata2014, p. 8), since the ICC was well below 0.05, I used a single level regression model.

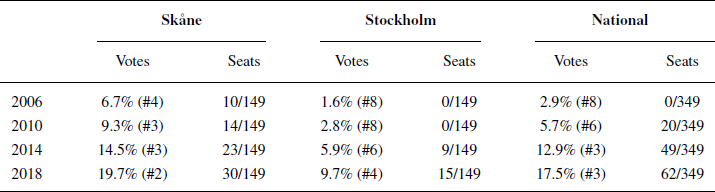

To further understand what drives feelings of stigmatisation, I draw on data from 30 online interviews I conducted between April 2021 and January 2022 with SD grassroots members in two selected counties, Skåne and Stockholm. These were chosen because they differ in terms of the electoral support which the party enjoys (see Table 2). While the SD vote share in Skåne, the party's traditional stronghold, has constantly been above the national vote share, the one in Stockholm has constantly been below it. Therefore, this selection allows us to get a better picture of the diverse contexts in which SD grassroots members are embedded. In order to recruit participants, I contacted the SD county presidents of Skåne and Stockholm, and asked them to help organise the interviews, explaining that I was interested in talking with a mixture of women and men, and younger and older grassroots members. Interviews were conducted in English on two online platforms, Zoom and Skype, and asked questions about how and why people had joined the party, the kind of activities they undertook as party members, and the reasons for their sustained commitment (where applicable).Footnote 10

Table 2. SD vote share in last four national elections in Skåne, Stockholm and nationally

Source: Swedish Election Authority. The party's position relative to other Swedish parties is shown in parentheses. The electoral threshold to enter the Swedish national parliament is 4 per cent.

Who feels stigmatised?

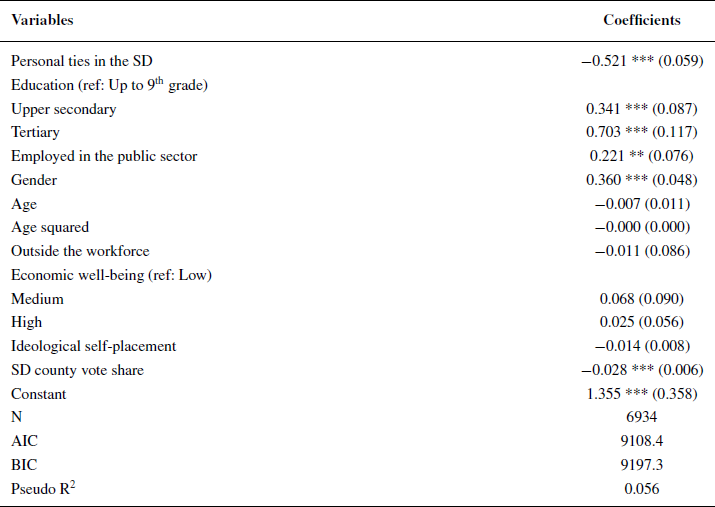

The survey results show that the majority of SD grassroots members feel stigmatised because of their membership. About 60 per cent of respondents agreed that it is not easy to publicly admit they are members of the SD, with one out of four strongly agreeing with this statement.Footnote 11 Therefore, despite the efforts of the party to shed its ‘extreme baggage’ (McDonnell et al., Reference McDonnell, Werner and Karlsson2021, p. 627), SD membership remains a source of discredit in the eyes of most SD rank‐and‐file. Table 3 reports the estimated effects of the variables identified earlier as potential drivers of feelings of stigmatisation. As expected, these are distributed unequally among different categories of party members. I will now turn to each predictor to assess which PRR party members are more likely to feel stigmatised. First, I consider the impact of the three independent variables, and then I move on to the control variables suggested in the literature.

Table 3. Logistic regression model predicting feelings of stigmatisation among PRR party members

Notes: Robust standard errors adjusted for clustering on county are shown in parentheses. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

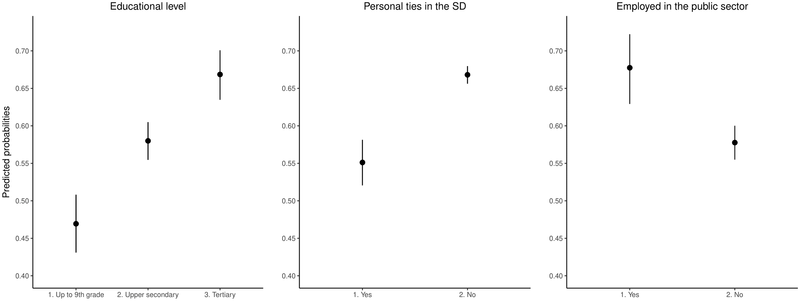

Table 3 illustrates that education is the strongest predictor of feelings of stigmatisation, both among the three independent variables and in the whole model. Its effect is in the expected direction: the higher the educational qualification achieved by SD grassroots members, the more likely that they will be wary of revealing their membership. As the left graph of Figure 1 shows, the probability of feeling stigmatised among those who completed tertiary education is estimated at 67 per cent, as opposed to 58 per cent among members with an upper secondary education, and 47 per cent among those who attended up to ninth grade. This result suggests that, comparatively, the personal networks of highly educated SD grassroots members represent a more difficult environment to talk about their membership, thus providing support for H2. The second strongest driver among the independent variables, as well as in the full model, is having had personal ties in the SD. As predicted, those who have had relatives and/or friends who were SD members are less susceptible to stigma than those who have never had anyone. Noticeably, there is a 12‐percentage point gap in estimated probabilities of feeling stigmatised between the two groups (55 vs 67 per cent, respectively), as the central graph in Figure 1 illustrates. This lends support for H1, and illustrates that individuals socialised in a context favourable to the SD find their membership less burdensome. Finally, being employed in the public sector also influences feelings of stigmatisation, with public employees considering their SD membership more discrediting than the rest of the respondents. The right graph of Figure 1 shows that the estimated probability of feeling stigmatised among the latter is 58 per cent, which is 10 percentage points lower than that of public employees (68 per cent). Therefore, this finding provides support for H3, indicating that public institutions do not provide a friendly political environment for SD rank‐and‐file.Footnote 12

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities of feeling stigmatised among PRR party members by independent variable, with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Moving on to the control variables, we see that, among socio‐demographic factors, only gender is a strong and significant predictor of feelings of stigmatisation, with women being more likely than men to report they find it hard to talk about their membership. Notably, after education and personal ties, the effect of gender is the third strongest in the whole model. The probability of feeling stigmatised is estimated at 66 per cent among women members, as opposed to 57 per cent among men. This result echoes those by Harteveld et al. (Reference Harteveld, Dahlberg, Kokkonen and van der Brug2017) who find that women are more sensitive to the stigma surrounding PRR parties. As for the two variables related to socio‐economic explanations of stigma, neither being outside the workforce nor economic well‐being affect feelings of stigmatisation. This counters the idea that, in comparison to low‐SES individuals, citizens with (well‐paid) jobs will be more susceptible to stigma, because they have more to lose economically from being a PRR party member (Art, Reference Art2011).Footnote 13 Relatedly, given that young and older people are overrepresented among members outside the workforce, age does not have an impact on whether SD rank‐and‐file find their membership discrediting. Furthermore, ideological self‐placement has no significant effect on feelings of stigmatisation. To give an example, the probability of finding SD membership discrediting is estimated at 60 per cent among those who place themselves at 6 on a 1–10 left–right scale, as opposed to 58 per cent among those who locate themselves at 10. Again, this finding counters the prevailing wisdom that extremist PRR party members are less susceptible to stigma than moderate ones, because they do not care about defeating social norms (Art, Reference Art2011). It is important to acknowledge, however, that, according to some scholars, the left‐right scale gauges people's position on the socio‐economic dimension rather than on the socio‐cultural one (e.g., van der Brug & van Spanje, Reference van der Brug and van Spanje2009), which for PRR supporters can be expected to be more salient. Therefore, while these results on ideological extremism are noteworthy, they come with this small caveat.

Finally, the survey results show that, in addition to personal networks, the broader socio‐political context in which SD rank‐and‐file are embedded also influences feelings of stigmatisation, as captured by the variable which measures the SD county vote share in the 2018 general election. As one could expect, the lower the SD vote share is in a county, the higher the chance that SD grassroots members will be wary of disclosing their membership. When looking at the predicted probability of feeling stigmatised among members living in the county with the highest vote share, Blekinge, in comparison to those living in the county with the lowest one, Västerbotten, we find a remarkable 12 percentage point gap (54 vs 66 per cent). This finding resonates with a recent study by Harteveld et al. (Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2021) on affective polarisation in Europe, which demonstrates that when the electoral support for PRR parties increases, these tend to receive more sympathy from mainstream party voters. In other words, electoral success works as a social cue that signals increasing legitimacy of PRR parties (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2021, p. 12), thereby reducing the stigma of being a PRR party member.

To corroborate the robustness of my findings, the regression was re‐estimated by firstly excluding each of the three most populous counties (Skåne, Stockholm and Västra Götaland) one at a time, and then excluding all three together (Table D1 in Appendix D). I also re‐ran the model by keeping the dependent variable as an ordinal variable of four levels (Table D5), to make sure the results were not sensitive to its dichotomisation. Moreover, given how my measure of feeling stigmatised implied a lower bar compared to Goffman's definition, I dichotomised the dependent variable by distinguishing those who strongly agreed that they felt stigmatised from the rest of respondents (Table D6). Finally, it is plausible that levels of engagement within the party may affect feelings of stigmatisation of PRR grassroots members, and that more active rank‐and‐file will be less sensitive to stigma. Therefore, I re‐ran the main model by controlling for frequency of party meetings attendance, and for whether members held an internal party position (Table D7). Overall, the results are further supported by these tests.Footnote 14

‘It really sucks when people narrow you down to just your politics’

Each of the 30 grassroots members I interviewed was well aware of the stigma that comes with being a member of the SD. This meant that, when possible, they tried to keep a low profile and avoided disclosing their membership. However, this was not always successful, and could have serious repercussions on their personal relationships, such as in the cases of Member 9 (‘My father, he was furious. There was a long time when we didn't talk because of this’), and Member 10 (‘My best friend, he didn't want to be friends with me anymore, so that's a little bit sad’). It could also affect their economic well‐being and career prospects. Member 11, working in sales, confessed: ‘I actually believe that I lost several job opportunities because of my political involvement’. But the most serious consequences were in the form of physical and verbal threats, like the call that Member 16, at the time working in a big company based in the United States, received one afternoon: ‘He had checked me out [on the internet] and said that “I'm going to tell those in America, your employers, what a Nazi swine you are” and, you know, things like that’. Yet, despite interviewees being unequivocally conscious of (and often subject to) the social and material sanctions that characterise SD membership, their attitudes towards these varied considerably depending on the personal networks they were part of.

Stigma in the wider personal networks: Colleagues and acquaintances

A very frequent theme throughout the interviews was that those employed in the public sector found their membership especially discrediting, because they were surrounded by colleagues who held left‐wing views. As Member 4 puts it, those who work ‘within the municipalities or within hospitals, and teachers, for example, they are very much afraid of mentioning that they are joining the Sweden Democrats’. A clear example of this was Member 8, a social worker. Despite joining back in 2009, no one at work in 2021 knew she was an SD member. She admitted: ‘I'm a little bit afraid of what my colleagues and my employer think about this engagement. Maybe they don't think I should continue to work where I work’. Her fears may have been founded. For instance, Member 18 believed she had lost her job as a schoolteacher because they learnt about her membership: ‘They did not say, of course, that it was because of that, but I know it. […] That's how it is, because the Swedish school is very to the left’. These accounts help explain why, in the survey, public employees were significantly more likely to report they find it hard to talk about their membership. They also reflect how public institutions can represent unfriendly environments for PRR party members, as public employees are largely left‐wing (Knutsen, Reference Knutsen2005; Tepe, Reference Tepe2012). Moreover, in the specific case of universities, both staff and students were portrayed as being from the opposite side of the political spectrum. Member 20, a university student, revealed:

At the beginning, well, that was quite a pain in the arse. The universities in Sweden are very, very radical leftie. […] After a while they learned I was a party member. When I walked around from courses to courses, well, they spat on the ground when they saw me.

This experience resonates with the well‐established finding that education has a negative relationship with PRR support (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer and Mudde2016), and illustrate how the more educated PRR party members are, the lower the likelihood that they will be surrounded by people sharing their political views.

Stigma in the closer personal networks: Family and friends

The importance of personal networks in mediating the extent to which SD membership was perceived as discrediting was also evident in the role of relatives and friends. The interviews highlighted a few mechanisms in this regard. For instance, having close contacts in the SD reduced the stigma of joining the party in first place. An example of this was Member 15, who by joining herself encouraged other relatives to do the same:

I have my family, my mother's siblings and stuff, they are party members as well. […] I think we joined more or less the same time, when we became members. Because if one takes the step, it's easier for the rest to take the step.

Moreover, having personal ties in the party also worked as a way to gather information about it before getting involved. Once she joined, it took Member 2 some time, and the reassurances of her partner, to actually show up at the first party meetings:

It became easier because my partner got engaged and got to know the right people. I was a bit nervous before, you know, what will the meetings be like – if there are a lot of racists and strange ideas among the people that are engaged.

Finally, having family and/or friends in the SD allowed party members to discuss about politics and current affairs, which is something they felt they could not do with other people. Member 12, a 77‐year‐old woman, explained to me:

It's important, you know, to have someone to talk to about how you feel and what you read about. My family, my sister and my brother‐in‐law, and their children – I can always talk to them. And I have some other long‐term friends who understand. Not many people engage and understand.

Therefore, these stories emphasise how the most intimate networks of relatives and friends are crucial in influencing how PRR rank‐and‐file see and live their membership. Specifically, having close contacts in the party can attenuate the stigma of joining, the stigma of being active and the stigma of talking in public about politics.

Stigma as a gendered phenomenon

In addition to highlighting the importance of ‘significant others’ (Whiteley & Seyd, Reference Whiteley and Seyd1996) in driving feelings of stigmatisation, the interviews revealed how the stigma surrounding PRR membership is a deeply gendered phenomenon, with women being more affected than men. According to some, one of the reasons is that women tend to be employed in the public sector to a larger extent than men. Member 29, a schoolteacher, observed that ‘women have like, we have certain types of jobs, often. In my circle, most men have their own companies, or they are like craftsmen, artisans. And in those workplaces there is not the same resistance’. This recalls a common explanation for the gender gap in PRR support – women vote less for PRR parties partly because they are over‐represented among public employees (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, van der Brug, Dahlberg and Kokkonen2015). Another argument advanced for gender differences in attitudes towards stigma was that women are more sensitive to the opinions of others within their social circles, and thus find their membership more problematic to reveal than men. Member 29, talking about the adverse reactions she encountered when her membership was made public, concluded that ‘It's harder for us women. […] I think men, they don't care that much. Women do. Women are more afraid to be exposed’. Conversely, as Member 26 (a man) illustrated, ‘Males are more like – okay, the neighbour doesn't like me. Fuck off, I don't care. […] Males are more confronting’. These accounts suggest that women perceive a greater social risk in being PRR party members than men, echoing the results of Oshri et al. (2022) on how gendered dynamics of risk aversion affect the gender gap in PRR support.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study I have investigated which PRR grassroots members are more likely to feel stigmatised because of their membership. My theoretical framework was based on two premises: first, stigma is a social construct (Link & Phelan, Reference Link and Phelan2001), meaning that social explanations have to be central to explaining PRR stigmatisation; second, the decision of joining and being active in a party is affected by how political participation is perceived by ‘significant others’ whose opinions the (potential) member values and respects (Whiteley & Seyd, Reference Whiteley and Seyd1996). These ‘significant others’ are embedded in a variety of personal networks, from the closer ones including family and friends to the wider ones composed of colleagues and acquaintances. Depending on the political views prominent within these networks, I argued that PRR rank‐and‐file would find their membership more or less discrediting. Drawing on an original membership survey of about 7,000 members of the SD, and interviews with 30 of them, I showed that highly educated PRR party members, as well as those employed in the public sector, feel more stigmatised because their social and professional circles are filled with left‐wing people. By contrast, those who have had any relatives and/or friends in the SD are less burdened by the stigma of their membership. These findings have a number of implications for the study of PRR party organisation, as well as party membership in general, which I address below.

Since grassroots members are considered key actors in the ideological and organisational development of PRR parties, and stigmatisation represents a major obstacle to their recruitment and retention (Art, Reference Art2011; Klandermans, Reference Klandermans and Mudde2016), understanding what drives feelings of stigmatisation among PRR party members can provide unique insights into the growth of this party family. To give an example, one of the most consistent findings in party membership studies is that higher‐educated citizens are overrepresented (van Haute & Gauja, Reference van Haute and Gauja2015). By contrast, in my study, only 29 per cent of respondents had a tertiary (vocational or university) education qualification. To put this figure into context, the same proportion of tertiary‐educated people among memberships of other Swedish parties ranges between 54 and 75 per cent.Footnote 15 One plausible reason is that, despite having the material and cognitive resources to join a PRR party, highly‐educated PRR supporters will be deterred from doing so because of the stigma. Similarly, we know that the most active members tend to be those interested in standing as candidates (Whiteley & Seyd, Reference Whiteley and Seyd1996). Although the educational level of SD local candidates has increased over time (Loxbo & Bolin, Reference Loxbo and Bolin2016), the SD still fields less tertiary‐educated candidates than other Swedish parties (Dal Bó et al., Reference Dal Bó, Finan, Folke, Persson and Rickne2019). While this can be a reflection of the social base which the SD appeals to, it cannot be ruled out that grassroots members’ fear of making their membership public is partly what impedes PRR parties like the SD from putting forward their most educated and skilful members as candidates. Future research should therefore investigate more systematically whether feelings of stigmatisation affect levels of activism and political ambitions of PRR grassroots members. In this regard, my study has indicated that by examining stigma using the individual member, rather than the whole party, as the unit of analysis, one can gain a more thorough understanding of this phenomenon, and its possible consequences on PRR party organisation development.

At the same time, one of the main takeaways of this article is that when PRR grassroots members have relatives and friends who were either already party members when they joined, or became members since they joined, feelings of stigmatisation are attenuated. In a moment where the benefits for political parties of sustaining large and active membership bases are being questioned, this finding is particularly significant. Despite the advent of social media, and the crucial role that the latter has played in the SD's mobilising efforts given the cordon médiatique this party has been subject to (Hellström et al., Reference Hellström, Nilsson and Stoltz2012), SD grassroots members still act as ‘ambassadors to the community’ (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow1994, p. 47), providing outreach benefits through their daily contacts. In this sense, what in the past has been described as the ‘main liability’ of the SD, its rank‐and‐file base (Loxbo & Bolin, Reference Loxbo and Bolin2016, p. 172), today may be turning into an important source of organisational strength. While the relevance of grassroots members in established party families may be diminishing, therefore, this study suggests that for PRR parties, and especially those which are still striving to gain legitimacy among large sections of the public, grassroots members represent key figures for the recruitment and retention of other party members and supporters. As such, it would be interesting to conduct more research on these actors. For example, do they join for similar reasons as members of other political parties? Or is the ‘personal ties’ factor more relevant in their paths to membership? Are they similarly (in)active, or do they participate more often in party activities? Considering how the internal organisation of PRR parties is widely recognised as an important variable determining their electoral breakthrough (Loxbo & Bolin, Reference Loxbo and Bolin2016) and persistence (Art, Reference Art2011; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007), research on PRR grassroots members becomes even more timely.

This study has also highlighted how PRR party members differ in the ways they experience their membership – in this case, their susceptibility to stigmatisation. Art (Reference Art2011, p. 234) proposed that by breaking down memberships into groups, ‘one can gain more analytical leverage than by maintaining the unitary actor assumption’ that guides much work on far‐right organisations. The same can be said for political parties in general. My findings illustrate that our knowledge of party membership would benefit from considering characteristics such as members’ socio‐demographics as explanatory variables, rather than mere descriptive statistics of a sample. As this article has shown, PRR party members who did not complete high school will not find their political engagement as discrediting as those with a university degree. Nor will a shop‐owner, in comparison to a healthcare worker. Future research should investigate more extensively how factors like gender, age, education, occupation and ethnicity of party members affect partisan participation, from reasons for joining to future political ambitions. In other words, we should refrain from considering grassroots memberships as monolithic blocks, and extend the comparative focus from memberships across parties to include memberships within parties. Doing so would allow us to go beyond the ‘who, what and why’ questions which have been extensively addressed in the field (van Haute & Gauja, Reference van Haute and Gauja2015, p. 9), and to shed light on an undertheorised aspect of party membership – what the experience of membership actually means to individuals (Gauja, Reference Gauja2015, p. 244).

Finally, a word on generalisability. Even though the SD is among those PRR parties still subject to a cordon sanitaire because of its extremist past, I expect the findings of this study to hold across the PRR party family, for a number of reasons. First, the increasing openness of the Swedish mainstream right towards some sort of formal cooperation with the SD means that the cordon sanitaire is gradually weakening. As such, the SD is following what can be seen as ‘a common trajectory for radical right parties’, namely becoming increasingly normalised thanks to a shift in policy positions of other parties, increasing parliamentary representation, and media legitimisation (Bolin et al., Reference Bolin, Dahlberg and Blombäck2022, p. 5). Second, even in those PRR parties which are perceived as more respectable actors because they have no extremist legacy, PRR party members may nonetheless face stigmatisation, as is the case for League members in Italy (Biorcio, Reference Biorcio1997; Zulianello, Reference Zulianello2021). In this sense, political stigmatisation and societal stigmatisation are two related but distinct processes, and just because a political party is increasingly accepted in the electoral arena, it does not mean that the stigma at the societal level will similarly fade away (see, e.g., Bolin et al., Reference Bolin, Dahlberg and Blombäck2022). Therefore, while the extent of feelings of stigmatisation will possibly be lower among members of more accepted PRR parties, there are no reasons to believe that the dynamics underpinning feelings of stigmatisation will be any different. Future research could test this theory on less stigmatised parties such as Italy's League or the Danish People's Party. It would also be interesting to study the phenomenon of stigma among members of other party families. At a time when citizens are growingly disengaged from, and disillusioned by, political parties (Mair, Reference Mair2013), do grassroots members even of mainstream parties see their membership as something to hide from other people? If so, under what conditions do they feel stigmatised? This research could be extremely revealing of the public standing of political parties in current democracies.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the members of the “People, Elections and Parties” research group of the Centre for Governance and Public Policy (CGPP) at Griffith University – Max Grömping, Ferran Martinez i Coma, Duncan McDonnell, and Lee Morgenbesser – as well as Darren Halpin and the three anonymous reviewers for their extensive feedback on previous drafts of this article. I would also like to thank the participants at The Populism Seminar and the 2022 Australian Political Studies Association Standing Group on Political Organisations and Participation (APSA POP) workshop in Brisbane for their helpful comments, questions, and suggestions. Finally, I would like to thank the Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) for their financial support for the interview transcriptions.

Open access publishing facilitated by Griffith University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Griffith University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix A: Online membership survey of Sweden Democrats

Appendix B: Interviews with Sweden Democrats grassroots members

Appendix C: Control variables for statistical analyses

Appendix D: Robustness checks and further analyses

Supporting information