Introduction

Border closures and travel restrictions are among the most widely used policy measures to deal with pandemics (Kenwick & Simmons, Reference Kenwick and Simmons2020), yet their consequences for political attitudes are poorly understood. This is surprising because border closures have profound economic consequences and are palpable in people's everyday lives. Conflict over open or closed borders is also at the heart of an emerging transnational cleavage in Europe (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). Hence, actual border closures should leave their imprint on people's political orientations.

At the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic in early 2020, 18 European countries were quick to impose travel restrictions and close the borders to their neighbouring countries (Freudlsperger et al., Reference Freudlsperger, Lipps, Nasr, Schilpp, Schimmelfennig and Yildirim2024; Sabat et al., Reference Sabat, Neuman‐Böhme, Varghese, Barros, Brouwer, Exel, Schreyögg and Stargardt2020; Wolff & Ladi, Reference Wolff and Ladi2020). This led to an unprecedented period of sustained internal border closures in the Schengen area,Footnote 1 which had abolished national border controls since 1995 and facilitated an area of free movement across the European Union (EU) (Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2021). When responding to COVID‐19, national governments prioritized attempts to slow down the spread of the virus over one of the EU's core principles, that of free movement, disregarding the idea of European integration and cooperation. Especially people living in border regions, with strong cross‐national practices and ties, had to adapt their everyday lives to these closures (e.g., see Evrard et al., Reference Evrard, Nienaber and Sommaribas2020; Prokkola & Ridanpää, Reference Prokkola, Ridanpää, Brunn and Gilbreath2022). Images of families and friends living in cross‐border towns being separated by fences spread across the news (e.g., Illien, Reference Illien2020).

Borders are more than geographic divisions; they are socio‐political constructs that regulate flows, assert sovereignty and shape identities (Andersen & Prokkola, Reference Andersen, Prokkola, Andersen and Prokkola2021b; Evrard et al., Reference Evrard, Nienaber and Sommaribas2020; Paasi, Reference Paasi2011). Recent scholarship in the interdisciplinary field of border studies highlights how crises like COVID‐19 reveal and amplify the political, social and symbolic significance of border closures. While borders connect regions and enable exchange, they are never fully ‘open’ or ‘closed’ but exist on a spectrum of permeability (Brändle & Eisele, Reference Brändle and Eisele2022; Paasi, Reference Paasi2012; Popescu, Reference Popescu2012). During the pandemic, borders were partly or fully closed, disrupting EU principles of openness, suspending cross‐border practices and reinforcing ‘mental borders’ that heightened distinctions between insiders and outsiders (Wassenberg, Reference Wassenberg2020). Border restrictions revealed the vulnerabilities and adaptability of border communities in response to government‐imposed controls (e.g., see Andersen & Prokkola, Reference Andersen and Prokkola2021a; Evrard et al., Reference Evrard, Nienaber and Sommaribas2020). Despite their broad societal effects, the political implications of border closures remain underexplored, with most research focusing on their role in curbing the virus (e.g., Linka et al., Reference Linka, Peirlinck, Costabal and Kuhl2020; Mallapaty, Reference Mallapaty2020; Shiraef et al., Reference Shiraef, Friesen, Feddern and Weiss2022), economic impacts (e.g., Capello et al., Reference Capello, Caragliu and Panzera2023) or legal aspects (e.g., Goldner Lang, Reference Goldner Lang2023; Thym & Bornemann, Reference Thym and Bornemann2021). This study fills this gap by examining how border closures shape political attitudes.

We argue that it is equally important to advance our understanding of the attitudinal consequences of intra‐EU border closures. The central expectation of our paper is that the closure of Schengen borders in the COVID‐19 crisis decreased EU support and increased hostility towards immigrants by signalling that people from across the border are a threat to public health, showing little trust in European governance, and by reducing cross‐border interactions.

Empirically, we focus on Germany, one of the largest EU member states, which is part of the Schengen zone and shares borders with eight EU member states as well as Switzerland. Due to the diversity of bordering countries and the federal system of Germany, different border measures were in place at different points in time (Blauberger et al., Reference Blauberger, Grabbe and Servent2023). This allows for variation in border policies, which is necessary to identify the effects of these closures. To test the effect of closed borders on attitudes, we use a difference‐in‐differences (DiD) design that exploits variation in the closing of German borders with the neighbouring countries across regions and over time. We collect fine‐grained regional data on COVID‐19‐related border closures and survey data from the German Socio‐Economic Panel (SOEP) to estimate the effect of border closures on attitudes towards immigrants and EU support (Socio‐Economic Panel (SOEP), 2022).

We find that border closures had a short‐term adverse impact on EU support, which gradually subsided over time. We also find that border closures have the potential to increase outgroup hostility. Our findings indicate that people living close to a border that shut down became significantly more negative towards immigrants immediately after the introduction of border closures.

Overall, our study contributes to existing research in several ways. First, by isolating the effect of border closures on EU support and outgroup hostility, we make an important theoretical contribution to the literature on COVID‐related attitudinal changes. While a large body of research has dealt with the question of whether the virus itself stokes nationalism (Bieber, Reference Bieber2022; Wamsler et al., Reference Wamsler, Freitag, Erhardt and Filsinger2023; Woods et al., Reference Woods, Schertzer, Greenfeld, Hughes and Miller‐Idriss2020), anti‐immigrant attitudes and outgroup hostility (Bartoš et al., Reference Bartoš2021; Esses et al., Reference Esses, Sutter, Bouchard, Choi and Denice2021; Ferwerda et al., Reference Ferwerda, Magni, Hooghe and Marks2023; Freitag & Hofstetter, Reference Freitag and Hofstetter2022), our findings suggest that one of the central policies to stop the virus (also) led to more negative attitudes towards immigrants and the EU, but its effect waned quickly over time. Second, while there is a large literature studying the effect of the pandemic and the ensuing policy responses on support for national institutions (Bol et al., Reference Bol, Blais and Loewen2021; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Sohlberg, Ghersetti and Johansson2021; Schraff, Reference Schraff2021), only few studies examine its impact on orientations towards the EU (Marín et al., Reference Marín, Rapp, Adam, James and Manatschal2021; Nicoli et al., Reference Nicoli, Duin, Beetsma, Bremer, Burgoon, Kuhn, Meijers and Ruijter2024; Reinl et al., Reference Reinl, Katsanidou and Pötzschke2024), even though it turned out to be a central actor in fighting the virus and its economic consequences. Third, by collecting fine‐grained data that registered border closures and openings at daily intervals and combining them with information on respondents’ residence at the NUTS‐3 level (Nomenclature of territorial units for statistics ‐ small regions), we are able to analyse the impact of border closures at a more detailed level than previous research (Shiraef et al., Reference Shiraef, Friesen, Feddern and Weiss2022) and we shed light on the geographic and temporal differentiation in the impact of the pandemic on political orientations. Finally, our findings have important implications for the growing research on border politics in the EU and elsewhere (Freudlsperger et al., Reference Freudlsperger, Lipps, Nasr, Schilpp, Schimmelfennig and Yildirim2024; Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2021; Simmons & Kenwick, Reference Simmons and Kenwick2022).

Border closures and the transnational cleavage

European politics has been marked by an increasing political conflict that has arisen from European integration, globalization and immigration (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). In a nutshell, this conflict – also referred to as transnational cleavage – revolves around the question of whether national borders should be open or closed to allow immigrants, capital and culture from abroad to enter the national arena. In Europe, attitudes towards immigration and European integration are at the heart of this conflict (Van der Brug & Van Spanje, Reference Van der Brug and Van Spanje2009). Anti‐immigrant sentiment and scepticism towards the EU are core components of the nationalist‐protectionist side of this divide, while support for immigration and European integration reflects cosmopolitan‐globalist values.

The COVID‐19 pandemic and the ensuing border closures offer a unique lens through which to explore how these dynamics interact. Border closures acted as a flashpoint within this cleavage, reinforcing nationalist narratives that emphasize sovereignty, foreign threat and mistrust of supranational institutions. By exacerbating these tensions, the closures provide a microcosm of the broader political struggles shaping Europe.

In short, we posit that the unexpected and sudden closure of intra‐EU borders in the wake of the COVID‐19 crisis has increased opposition to European integration and immigration through two primary mechanisms: direct effects of border closures and contextual signals regarding the EU and national governance.

Direct mechanism: Threat perception and group dynamics

Group threat theory (Quillian, Reference Quillian1995) and behavioural immune system theory (Aarøe et al., Reference Aarøe, Bang Petersen and Arceneaux2017; Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Hill and Murray2018) provide a framework for understanding how border closures amplify hostility towards immigrants. Both theories suggest that crises, such as a pandemic, intensify perceptions of outgroups as sources of threat.

First, group threat theory (Quillian, Reference Quillian1995), a social psychological perspective, examines how perceived threats from one group to another can influence intergroup relations. The theory suggests that when one group perceives another as a threat, it can lead to negative attitudes, stereotypes and discriminatory behaviour (Gorodzeisky & Semyonov, Reference Gorodzeisky and Semyonov2016). These perceived threats can be symbolic, such as cultural threats, or realistic, such as economic competition, security threats or a deadly pandemic (Rios et al., Reference Rios, Sosa and Osborn2018).

Second, behavioural immune system theory (Aarøe et al., Reference Aarøe, Bang Petersen and Arceneaux2017; Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Hill and Murray2018; Freitag & Hofstetter, Reference Freitag and Hofstetter2022; Wamsler et al., Reference Wamsler, Freitag, Erhardt and Filsinger2023) makes an even more direct link between threats related to pandemics and outgroup attitudes. According to this theory, individuals have developed psychological mechanisms to detect and respond to cues associated with the presence of pathogens or infectious diseases in their environment. These mechanisms are designed to protect individuals and groups from the potential threats posed by infectious agents. The theory posits that a pandemic increases hostility towards outgroups as a protection mechanism. Aarøe et al. (Reference Aarøe, Bang Petersen and Arceneaux2017) tested this theory for anti‐immigration attitudes in the United States and Denmark and found, indeed, a link between behavioural immune sensitivity and anti‐immigration attitudes. Using a cross‐national survey fielded in the first COVID‐19 wave, Wamsler et al. (Reference Wamsler, Freitag, Erhardt and Filsinger2023) found that exposure to the pandemic was linked to more ethnic conceptions of nationhood as opposed to civic ones.

While previous research has already established a link between COVID‐related threat exposure and hostility towards immigrants (Ferwerda et al., Reference Ferwerda, Magni, Hooghe and Marks2023; Freitag & Hofstetter, Reference Freitag and Hofstetter2022; Marín et al., Reference Marín, Rapp, Adam, James and Manatschal2021), we emphasize the role of border closures – rather than the virus itself or other pandemic measures – as a distinct mechanism that activates hostility towards immigrants. Lockdowns and social distancing measures suggested that the virus was omnipresent and potentially carried by anyone, including close friends, neighbours and relatives. In contrast, border closures sent a focused and powerful signal that the pandemic threat originated abroad and could be mitigated by restricting cross‐border movement and keeping foreigners out. This framing mobilized perceptions of foreigners as potential threats, reinforcing xenophobic attitudes and general hostility towards immigrants (e.g., see Bartoš et al., Reference Bartoš2021; Esses & Hamilton, Reference Esses and Hamilton2021; Hartman et al., Reference Hartman2021). These effects were not only limited to populations on the other side of the border but also tapped into broader narratives of external threats, such as the ‘Chinese virus’ rhetoric and stigmatization of foreigners (Reny & Barreto, Reference Reny and Barreto2022; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Li, Luu, Yan and Madrisotti2021).

In summary, the COVID‐19 border closures reinforced these dynamics by explicitly linking the virus to external dangers. Unlike universal measures such as lockdowns, border closures directly targeted the foreign ‘other’, amplifying fears and hostility. Based on this framework, we propose the following hypothesis:

1H Border closures will lead to an increase in hostility towards immigrants.

We argue that this hostility emerges from direct mechanisms caused by the border closures, such as heightened threat perception and the behavioural immune response.

Contextual mechanism: Trust and European integration

While border closures directly influenced perceptions of foreigners, we argue that their broader political context and indirect consequences also impacted attitudes towards the EU. By closing borders unilaterally, national governments signalled a lack of confidence in the EU's ability to manage the crisis, challenging the union's principles of free movement and solidarity. The pandemic's political framing exacerbated this erosion of trust, as member states – especially in the first weeks of the pandemic – prioritized national security over collective European solutions. These closures disrupted not only political cooperation but also the daily cross‐border interactions that underpin citizens’ sense of connection to the EU. Transactionalist theory (Deutsch et al., Reference Deutsch, Burrell, Kann, Lee, Lichterman, Lindgren, Loewenheim and Wagenen1957) provides a valuable framework for understanding these dynamics, highlighting how regular cross‐border exchanges foster trust and attachment to broader supranational entities. A large body of literature within this line of research shows that European citizens who regularly interact across borders are indeed more likely to have a European identity and show support for European integration (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2015; Prati et al., Reference Prati, Cicognani and Mazzoni2019; Stoeckel, Reference Stoeckel2016). We argue that the prolonged prohibition of these interactions disrupted the development of attachment to Europe in the short term, reinforcing a reliance on national‐level solutions. Consequently, border closures symbolized the perceived ineffectiveness of the EU, further diminishing public support for European integration.

Recent research provides important insights into the relationship between border regions and EU support. On the one hand, Nasr and Rieger (Reference Nasr and Rieger2023) find that individuals living in border regions tend to hold more Eurosceptic views, driven by lower trust in national political institutions, which translates into broader distrust of the EU. On the other hand, Bauhr and Charron (Reference Bauhr and Charron2024) find that citizens living close to European borders are more likely to express a stronger European identity compared to those living further inland. This is in line with earlier research by Kuhn (Reference Kuhn2012), who finds that German border residents are less prone to Euroscepticism, not simply because they live close to the border, but because they engage more in transnational interactions.

While these previous studies (Bauhr & Charron, Reference Bauhr and Charron2024; Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012; Nasr & Rieger, Reference Nasr and Rieger2023) are concerned with baseline differences in Euroscepticism in border and core regions, we do not claim that these regions are inherently more or less supportive of the EU. Instead, we argue that border closures disproportionately affected these regions due to their dependence on cross‐border interactions for economic, social and cultural practices. This disruption, therefore, likely had a stronger negative impact on EU support in border regions compared to less integrated areas.

Based on this framework, we propose the following second hypothesis:

2H Border closures will lead to a decrease in EU support.

We argue that this decrease is driven by contextual mechanisms, including the symbolic undermining of European solidarity and the disruption of cross‐border interactions that foster trust and supranational identity. Specifically, the unilateral nature of border closures challenged the core principle of free movement within the EU, sending a signal that prioritized national sovereignty over collective European solutions. These signals likely eroded emotional attachment to the EU as a supranational institution, particularly in border regions where cross‐border practices were most integral to daily life. The resulting decrease in diffuse EU support reflects the weakening of emotional ties to Europe, as citizens reevaluated the EU's role and relevance in managing the crisis.

Temporal dimensions of border closures

The temporal dimension is critical for understanding how border closures influence political attitudes. As outlined in our theoretical framework, direct mechanisms, such as heightened threat perceptions stemming from group threat theory and behavioural immune system theory, are likely to produce immediate increases in anti‐immigrant sentiment. These reactions occur as border closures signal a direct external threat, activating psychological and social responses to perceived danger. In contrast, the contextual mechanisms, centred on the erosion of attachment to the EU and the disruption of cross‐border interactions emphasized by transactionalist theory, are expected to evolve more gradually. These mechanisms rely on the gradual realization of how border closures undermine European integration's tangible benefits, particularly in border regions where cross‐border interactions are integral to daily life.

To capture both the immediate and emerging effects of border closures, we focus on the 4 weeks following their implementation. Over time, external factors such as the stabilization of the pandemic and a more coordinated European response to border policies may have mitigated some of these effects, emphasizing the need to examine the dynamic nature of these changes. By considering the distinct temporal trajectories of the direct and contextual mechanisms, our analysis aims to disentangle the immediate effects of border closures from their sustained impact, offering a nuanced understanding of how these measures shape political attitudes.

Research design

We use a DiD research design to test our hypotheses. We combine survey data from the SOEP (Socio‐Economic Panel (SOEP), 2022) with manually collected data on COVID‐related border closures. By leveraging the SOEP data, our study can identify individuals living in close proximity to the border in Germany, allowing for a more precise estimation of the treatment effect.

Data on border closures

After examining existing datasets on mobility restrictions during the COVID‐19 pandemic (e.g., the Oxford Governance Response Tracker by Hale et al. (Reference Hale2020) or the COVID Border Accountability Project by Shiraef et al., Reference Shiraef, Hirst, Weiss, Naseer, Lazar, Beling, Straight, Feddern, Taylor, Jackson, Yu, Bhaskaran, Mattar, Amme, Shum, Mitsdarffer, Sweere, Brantley, Schenoni and Lewis‐Beck2021), we decided to create our own dataset on border closures for two reasons: First, those datasets are coded on the national level, not taking regional variation into account (e.g. Hale et al., Reference Hale2020, Shiraef et al., Reference Shiraef, Hirst, Weiss, Naseer, Lazar, Beling, Straight, Feddern, Taylor, Jackson, Yu, Bhaskaran, Mattar, Amme, Shum, Mitsdarffer, Sweere, Brantley, Schenoni and Lewis‐Beck2021), which is vital for this study. Second, some of the datasets only reported a start date of the measure but no date of termination (e.g., Piccoli et al., Reference Piccoli, Ader, Hoffmeyer‐Zlotnik, Mittamasser, Pedersen, Pont, Rausis and Sidler2020, Suryanarayanan et al., Reference Suryanarayanan, Tsou, Poddar, Mahajan, Dandala, Madan, Agrawal, Wachira, Samuel, Bar‐Shira, Kipchirchir, Okwako, Ogallo, Otieno, Nyota, Matu, Barros, Shats, Kagan, Remy, Bent, Guhan, Mahatma, Walcott‐Bryant, Pathak and Rosen‐Zvi2021). However, to accurately test the impact of border closures on attitudes, we need to account for their reopening as well. Therefore, we collected fine‐grained daily data on Germany's closures based on official government documents and media reports. This approach has several advantages, for example, it takes into account that closures are not in place at all land borders simultaneously and that they can also be enforced by a neighbouring state. For example, the German–Danish border was closed first by the Danish authorities on 14 March 2020, followed by a closure from the German side on 16 March 2020 and stayed closed until 15 June 2020. In comparison, the German–Dutch border was never closed from the German or the Dutch side throughout the pandemic, while the Belgian border was closed from the Belgian side but not the German one. In short, we created a dyadic dataset accounting for closures from either the German side or their neighbouring side for each of the nine German border regions, respectively. To check the validity of our dataset, we compared it to a report by Peyrony et al. (Reference Peyrony, Rubio and Viaggi2021), which also summarized border closures for each border dyad. For all nine German border dyads, we only found two discrepancies between their description in the report and our dataset.Footnote 2 After checking other datasets, as well as official documents and media reports, we decided to keep our original dates for those two cases.

Moreover, since we do not expect the described mechanisms to work for all citizens equally. This paper places special emphasis on people living in border regions, as they were most directly affected by the measure in their daily lives. First, border residents live in close geographical proximity to foreign populations and markets. Hence, they should be more perceptive of border closures to begin with and more sensitive to any signals of pandemic threat coming from abroad that were emitted by closing the border to stop the virus. Second, while the border closures came as a surprise for everyone, they had particularly strong implications for the everyday lives of citizens living close to a national border. Given the close geographical proximity to the border, the Schengen Area enables border residents to lead truly transnational lives by spreading their daily activities across two countries and having access to the goods and services of two countries. Hence, Schengen border regions have become epicentres of cross‐border activities. Empirical research suggests that border residents are indeed more likely to interact across borders on a regular level (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012; Rehm et al., Reference Rehm, Schröder and Wenzelburger2024). The COVID‐19‐related border closures put an abrupt end to these practices, while people living in ‘core regions’, that is, regions further away from the national border, were less affected by the border closures. At the same time, border closures might also send more powerful threat messages to border residents as they are in close proximity to potential external threats, reinforcing fears and insecurity among the local population. Therefore, our main treatment variable takes the value 1 if an individual lives in a border region and experienced any (either external or internal) border closures at the time of their interview, and 0 otherwise.

We define a border region as a district whose geographic centroid lies within 25 km of the closest border and assign it to the specific closest border. For example, all districts whose centroids are within 25 km of the Polish border will be assigned to the Polish border region. Our choice of a 25‐km radius aligns with established norms of spatial analysis, as the evidence suggests that it captures a representative area while maintaining analytical detail (Gould, Reference Gould1986; Hanson, Reference Hanson2001). Figure 1 provides an overview of the respective border regions.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Visualization of the nine border regions by Kreis (district).

Note: Each ‘dot’ indicates the geographical centroid of a Kreis. If the centroid is within 25 km of a German land border with a neighbouring country, we consider it to be part of the corresponding border region.

Initially, we assume that individuals who live in a border region but did not experience a border closure and individuals who live in a core region (any district not directly bordering another country) are both in the control group. However, this assumption is a strong one, as there may be differences between border regions and core regions that we are not accounting for. Therefore, we relax this assumption later on by only comparing groups that live in a border region and experienced a border closure with groups that live in a border region but did not experience a border closure at the respective time, even if this decreases our number of observations.

Measuring attitudes: The German Socio‐Economic Panel

We use the SOEP, which is a representative household panel survey conducted in Germany since 1984. It includes about 30,000 respondents in 15,000 households and covers topics such as work and employment, attitudes and values, as well as integration, migration and transnationalization. The centrepiece of the SOEP is the SOEP‐Core survey, which provides information about every member of every household that takes part in the longitudinal SOEP study. This sample includes Germans as well as recent immigrants and refugees. Especially important for the purpose of our study is that the SOEP provides regional information at the NUTS‐3 level (Landkreise) on the individual level, which, due to data security and privacy standards, is only accessible on‐site at the SOEP headquarter in Berlin. The granularity of the data enables highly localized analyses of socio‐economic variables, enhancing the precision and relevance of our study. In 2020, the 37th wave of the SOEP‐Core was conducted which included 21,614 adults across 13,460 households.

To operationalize attitudes towards immigrants, we use three questions on attitudes towards refugees: Respondents were asked whether refugees erode or enrich cultural life in Germany, whether refugees are good for the German economy and whether they make Germany a better place. Each question is measured on a scale from 0 to 11, with higher numbers indicating more positive attitudes towards refugees. To create a comprehensive measure, we combined these three items into a single index by applying principal component analysis (PCA), which captures the shared variance across the items (e.g., see Abdi & Williams, Reference Abdi and Williams2010; Bro & Smilde, Reference Bro and Smilde2014). It would be preferable to measure attitudes towards specific groups of foreigners, such as those living immediately across the border. However, due to data limitations, these detailed measures and tests are not feasible. However, while we ideally would measure attitudes towards specific groups of foreigners, our focus on general attitudes towards immigrants remains consistent with the broader theoretical context. The pandemic and associated border closures were driven by a generalized rise in xenophobia, where immigrants – regardless of their proximity – were framed as risks in terms of both disease transmission and competition over resources like healthcare (e.g., see Dhanani & Franz, Reference Dhanani and Franz2021; Reny & Barreto, Reference Reny and Barreto2022; White, Reference White2020). As such, the general measure of attitudes towards refugees still captures relevant dynamics.

When it comes to EU support, we follow Easton's distinction between diffuse and specific support (Easton, Reference Easton1975; Hobolt & De Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2016; Norris, Reference Norris1997). While specific support is output and performance oriented, diffuse support relates to more general attitudes towards the EU. The SOEP wave we use includes one item which can be used to measure diffuse support (‘How strongly do you feel emotionally connected to Europe?’). The item was recorded on a scale from 0 (‘not at all emotionally attached’) to 10 (‘very emotionally attached’). It would be desirable to also analyse specific EU support, but the survey does not include any relevant items. Nonetheless, our measure aligns well with our theoretical framework, as we argue that border closures disrupted cross‐border interactions and undermined trust in the EU, potentially leading to a weakening of emotional attachment to the EU. However, this measure also presents certain limitations. First, it does not capture specific support, such as evaluations of EU performance or policy effectiveness, which might be influenced by border closures in different ways. Second, while the item provides insight into emotional attachment, it does not allow for a multidimensional analysis of diffuse support.

SOEP data: Descriptive statistics

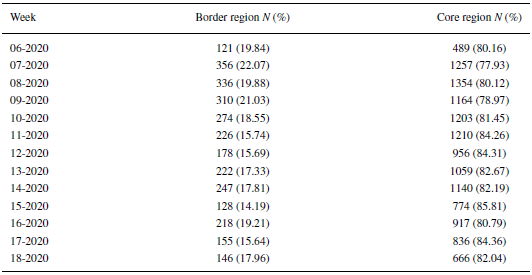

In our analysis, we examine survey responses from 2020, which include a total of 4718 participants from border regions and 22,781 participants from core regions. Among these, 1104 individuals residing in the border regions were classified as treated, that is, having experienced the border closures directly, while 26,395 participants from both border and core regions formed the control group. Weekly interviews, summarized in Table 1, reveal that the proportion of interviews conducted in border regions ranges between 15 per cent and 20 per cent, while those in core regions range between 77 per cent and 85 per cent. This consistent weekly distribution highlights the stability in representation between border and core regions over time, ensuring a balanced dataset for identifying the effects of border closures on EU attachment.

Table 1. Number of interviews per week (border vs. core regions)

Note: For an overview of all weeks of 2020, see online Appendix B.1

Additionally, we compare mean values between core and border regions for our three outcome variables. Before the border closures, the mean values for key outcomes reveal minimal differences between border and core regions, suggesting no substantial pretreatment differences. For attitudes towards immigration, the mean in the border regions is 0.54 (SD = 0.23), compared to 0.50 (SD = 0.24) in the core regions, indicating very similar levels of support. Similarly, for attitudes towards the EU, the mean in the border regions is 0.67 (SD = 0.23), closely aligned with 0.68 (SD = 0.24) in the core regions.

Control variables

We used the following control variables: To account for socio‐structural differences at the individual level, we control for age, sex and education, as well as for voting in the 2017 Bundestag election accounts for political preferences. To account for transnational ties and interactions, we include measures on working and contacts abroad as well as EU residence status, while the option to work from home accounts for lower exposure to COVID‐19 restrictions. We also control for the survey completion mode. Finally, we control for some region‐specific variables such as the percentage of foreigners per district, the population per border region, as well as if it is a border region towards an Eastern country. Moreover, we use data from the German Statistical Office (DESTATIS, 2023) to control for the infection rate per district. Lastly, in additional robustness checks, we control for national and regional lockdowns by using data from the German Statistical Office (DESTATIS, 2023, Variable: Code m18‐030) to capture internal mobility restrictions and data from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC, 2022) to control for the infection rate in the neighbouring border district (i.e., infection rate on the non‐German side of the border) indicating the severeness of the situation and consequently pandemic threat, at the other side of the border.

Analysis

We distinguish between nine border regions, each corresponding to one of Germany's neighbouring countries (i.e., Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland and Switzerland; for an overview, see Figure 1). Each district (NUTS‐3 level) with a centroid within 25 km of the closest border with a neighbouring country is considered to be in a border region. Our unit of analysis is the border‐week, meaning that each border region is observed weekly throughout the year.

Figure 2 provides an overview of respondents aggregated by their border region (with ‘Germany’ representing the core regions) and treatment status for our treatment variable. Each square represents a border region‐week observation, with missing data indicating groups without available information. Upon inspection of the figure, a pattern of staggered treatment over time is evident. However, it is also apparent that there are insufficient interviews for the first 3 weeks of 2020. Online Appendix Table B.1 further illustrates this by plotting the number of interviews per week and comparing interviews in border and core regions. The figure shows that in the first few weeks of the year, almost no interviews were conducted. Although there are not enough interviews for the first 3 weeks of 2020 for all groups per week, this should not pose a problem for our estimation strategy since we match on treatment history and covariates to control for potential confounding variables and ensure that the treatment and control groups are comparable. Furthermore, we focus on the time period of 4 weeks before and after the start of the closures in mid‐March 2020, which does not include the first weeks of 2020. This becomes relevant only for one of our robustness checks, which includes the time period of 8 weeks before the start of the closures and is discussed in that context. Ultimately, by examining nine border regions over the 52 weeks in 2020 and accounting for missing data, this approach results in the following sample sizes at the border‐week unit: a control group of n Control = 312 and a treated group of n Treated = 84. Here, a ‘border‐week’ unit refers to a single border region observed during a given week. For example, if the French border region (coloured in orange in Figure 1) experienced a closure on more than half of the days in that week, that region‐week pair would count as one treated observation within our sample.

Figure 2. Aggregated respondents based on border region and treatment status for our main treatment variable (any border closure).

Note: Each square shows a border region‐week observation. Germany unit aggregates people who do not live in a border region. Missing weeks result from not enough interviews being conducted in the specific border region and week – the smaller the shared border (e.g., Luxembourg) the more likely are missing weeks. For a full overview of the number of interviews in the combined border and core regions per week, see Online Appendix B.1.

PanelMatch and matching analysis

In our analysis, we employ a DiD framework combined with matching methods to estimate the causal effect of border closures on political attitudes. The DiD estimator compares changes in attitudes over time between treated units (border regions with closures) and control units (regions without closures), assuming that, in the absence of treatment, both groups would follow similar trends. Matching methods enhance comparability by ensuring that observed differences in attitudes are attributable to border closures rather than pre‐existing conditions or time‐varying confounders.

We implement this approach using the PanelMatch method (Imai et al., Reference Imai, Kim and Wang2021), which enhances the analysis in three key ways. First, it accommodates staggered treatment assignments and treatment reversals, making it ideal for capturing the temporal dynamics of border closures, where some regions closed or reopened their borders at different times. Second, it adjusts for confounders, such as cross‐border connections in our case, even when weekly data for these variables is unavailable. Third, it systematically selects comparable cases across treated and control groups, providing a robust counterfactual to improve the validity of the estimated treatment effects.

Importantly, this method introduces two crucial parameters: F and L. F represents the number of weeks following a border closure, while L represents the number of weeks preceding the treatment. Setting F allows estimation of treatment effects over time, while L accounts for treatment history before the intervention. For instance, if F is set to 4, we can calculate the cumulative treatment effect for the 4 weeks following the start of the border closure – comprising the first week of the closure (T) and the subsequent 3 weeks (T+1, T+2, T+3). Conversely, L adjusts for treatment history before the intervention. Setting L to 4 allows for accounting for treatment history up to 4 weeks before the treatment (T−1, T−2, T−3, T−4). In our case, we compare units that experienced a border closure with units that had a similar trajectory but did not experience a border closure (including core regions).

To account for potential confounding factors, we incorporate a range of time‐varying covariates, such as infection rate per district and the infection rate in the across‐the‐border districts (i.e., the non‐German side of the border area), as well as time‐nonvarying covariates, including age, gender, transnational contacts (i.e., working abroad and contacts abroad), education, employment, voting in the 2017 Bundestag elections, the option to work from home, EU residence status and survey completion mode in our models that use covariate matching. These covariates capture various factors that may influence political attitudes. Additionally, we account for region‐specific factors such as population per border region, if it is a region bordering an Eastern neighbouring country (eastern borders have been more effected by migration streams in the past and, therefore, previously experienced restrictive measures such as temporary border controls) as well as the percentage of foreigners per district.

Our analysis uses non‐parametric matching techniques for covariates. While the DiD estimator relaxes the assumption of unconfoundedness, it requires a parallel trend in the outcome variable, assessed by matching on previous treatment history and covariate trajectory. Relating to this, we demonstrate the balance of covariates by treatment in Online Appendix Table E.1 and employ the Mahalanobis refinement method to effectively balance time‐varying and time‐invariant covariates, particularly across diverse regions with multiple confounding factors. Online Appendix Figure E.1 illustrates significant improvements in covariate balance, with Mahalanobis refinement compared to the no‐refinement method. Although some imbalance remains with the Mahalanobis distance, the standardized mean difference for the lagged outcome remains stable, reinforcing the validity of the parallel trends assumption for the proposed DiD estimator (Imai et al., Reference Imai, Kim and Wang2021).

Results

Figures 3 and 4 present the results on attitudes towards refugees and EU attachment.

Figure 3. Average treatment effect on attitudes towards refugees.

Note: This figure presents the estimated effects of any border closure on attitudes towards refugees (PCA) in border regions (y‐axis). The outcome variable is normalized to vary between 0 and 1 for ease of interpretation. The grey estimates are generated without matching or refinement, while the refined estimates, shown in blue, apply matching and refinement, both accompanied by 95 per cent confidence intervals. The analysis covers an 8‐week period: 4 weeks prior to the border closures (T−1, T−2, T−3, T−4), the week of the closures (T) and the following 3 weeks (T+1, T+2, T+3). For this 8‐week period, the analysis includes N control = 45 and N treated = 27 region‐week units.

Figure 4. Average treatment effect on attachment with Europe.

Note: This figure presents the estimated effects of any border closure on EU attachment in border regions (y‐axis). The outcome variable is normalized to vary between 0 and 1 for ease of interpretation.

The grey estimates are generated without matching or refinement, while the refined estimates, shown in blue, apply matching and refinement, both accompanied by 95 per cent confidence intervals. The analysis covers an 8‐week period: 4 weeks prior to the border closures (T−1, T−2, T−3, T−4), the week of the closures (T) and the following 3 weeks (T+1, T+2, T+3). For this 8‐week period, the analysis includes N control = 45 and N treated = 27 region‐week units.

To ensure comparability, units are matched based on their treatment and covariate histories 4 weeks prior to a border closure (i.e., L = 4). We distinguish between the short ‐and medium‐term effects of border closures on people living in border regions by examining the effects up to 4 weeks after the start of the border closures (i.e., F = 4). For each week, the graph displays the over‐time treatment effect with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

To test H1, we analyse the effect of border closures on attitudes towards refugees. As expected, we find an immediate negative treatment effect in the first week after border closures, indicating an overall 7.6 percentage‐point decrease in welcoming attitudes towards refugees (p < 0.05). This means attitudes towards refugees dropped by more than 7 percentage points in the group that did directly experience a border closure compared to those that did not. However, the effect becomes insignificant in the following 3 weeks. The result is robust to the matching procedure, with no significant differences between the treatment and control groups before the start of the treatment, indicating that the treatment effect is not driven by observable differences between the treatment and control groups and supporting a valid parallel trend assumption prior to the treatment. Hence, we find limited support for H1.

In the week following the start of border closures, we observed a negative effect on EU attachment by an overall 6.5 percentage‐point decrease in the treatment group compared to the control group (p < 0.05). This aligns with our theoretical expectation of a slightly delayed effect on this outcome, as the impact of border closures on emotional attachment to the EU likely required time to manifest. Specifically, emotional attachment dropped by more than 6 percentage points in the group directly experiencing a border closure compared to those that did not. This effect quickly fades away over time, particularly within a month after the onset of the treatment. Again, no significant differences between the treatment and control groups can be observed before border closures, providing further evidence for the valid parallel trends assumption.

As an alternative model, we relaxed the assumption of core regions being in the control group for our two significant models. This means that, in this model, closed‐border regions are compared to open‐border regions. We show these results in Online Appendix Figures C.2 and C.1. The results remain substantively the same.

Overall, therefore, we find support for hypotheses H1 and H2 only in the short term, which fades away over time.

Robustness checks

We conducted a variety of additional analyses to assess the validity of our results. First, we estimate the effects up to 6 and 8 weeks post‐treatment, respectively, to see whether the effects are sustained. The results of these checks are presented in Online Appendix Figures D.1 and D.2 for 6 weeks post‐treatment and in Online Appendix Figures D.3 and D.4 for up to 8 weeks post‐treatment. They confirm the robustness of our findings with the initial negative effect on attitudes towards refugees and the significant negative effect on EU support in week two being consistent across the different models.

Second, to test the robustness of our two significant effects, we added the presence of a federal or regional lockdown as a control variable. The result can be found in Online Appendix Figures D.5 and D.6. The results remain robust when controlling for national and regional lockdowns. Third, we account for infection rates at the other side of the border to control for the overall severity of the pandemic, and hence the pandemic threat, in the neighbouring region. Online Appendix Figures D.7 and D.8 demonstrate that our findings remain significant even when accounting for the severity of the pandemic in the respective neighbouring country. Fourth, we excluded the covariates and our significant results remain robust to that specification (see Online Appendix Figures D.9 and D.10).

In sum, the negative but short‐term effect of border closures on attitudes towards refugees and EU support for people living in border regions remains robust throughout the numerous checks applied.

Placebo analyses

To be fair, the decrease in EU support and increase in anti‐immigrant attitudes found in this paper might be part and parcel of a more general downturn in political mood in response to the border closures. Hence, we also conducted placebo analyses to determine whether border closures had more general negative effects on political attitudes. Our analyses suggest that this is not the case. When looking at Online Appendix Figure D.11, we see that border closures did not have an effect on satisfaction with democracy. This suggests that the overall negative effects on attitudes and identities found in this paper really capture ingroup–outgroup dynamics triggered by the border closures rather than a general depression of political attitudes.

Conclusion

Did the national border closures during the COVID‐19 pandemic also lead to ‘closed minds and hearts’ among European citizens? While the impact of the pandemic itself on attitudes towards immigrants and nationalism has been well studied, the specific effects of national border closures, a central policy measure to stop the virus on political attitudes remain unclear. Border closures are traditionally among the most pervasive means to respond to pandemics (Kenwick & Simmons, Reference Kenwick and Simmons2020), but they seem to have mainly symbolic value rather than being an effective measure (Shiraef et al., Reference Shiraef, Friesen, Feddern and Weiss2022). This paper explored the wider political implications of border closures by analysing their impact on diffuse EU support and attitudes towards refugees.

Our analysis, based on unique and fine‐grained data on national border closures in Germany in 2020 combined with panel data from the SOEP, provides limited empirical support for our hypothesis that border closures negatively affected attitudes towards immigrants and EU support. Regarding our first hypothesis (H1) that border closures lead to an increase in hostility towards immigrants, we observe an immediate significant negative effect on attitudes towards refugees in the first week of border closures. Specifically, there is a 7.6 percentage‐point decrease in welcoming attitudes towards refugees (p < 0.05) among areas that directly experiencing border closures compared to those that did not. This effect becomes insignificant in the following 3 weeks, indicating a short‐lived effect. These findings align with the expectation of an immediate increase in hostility due to heightened threat perception and behavioural immune response. However, the effect's short duration suggests that the impact may not be as sustained as initially hypothesized.

Likewise, the results provide some support for the second hypothesis (H2) that border closures would lead to a decrease in EU support. We find a significant negative effect on EU attachment in the week following the start of border closures with a 6.5 percentage point decrease in EU attachment (p < 0.05) in areas directly experiencing border closures. Also, in this case, the effect quickly fades away, particularly within a month after the onset of the treatment. The slight delay in the effect on EU attachment aligns with the expectation that contextual mechanisms, such as the erosion of European solidarity and the disruption of cross‐border interactions, would take more time to manifest (Ares et al., Reference Ares, Ceka and Kriesi2017; Norris, Reference Norris1997). Both effects fading within a month suggest that external factors, such as pandemic stabilization or coordinated European responses, may have mitigated the long‐term impact of border closures.

Overall, the effects remain robust when comparing closed border regions to open border regions only (i.e., excluding core regions), supporting the validity of the findings. Various robustness checks, including extended post‐treatment periods, controlling for lockdowns and accounting for infection rates in neighbouring countries, confirm the consistency of the significant effects. Placebo analyses show no effect on satisfaction with democracy, suggesting that the observed changes were specific to ingroup–outgroup dynamics rather than a general depression of political attitudes. In conclusion, while the results provide some support for the hypotheses, the effects of border closures on attitudes towards immigrants and EU support appear to be short‐lived. This suggests that the impact of border closures on political attitudes may be more nuanced and temporary than initially theorized, highlighting the complex interplay between policy measures and public opinion during crisis situations.

These effect sizes, while not large, are substantively meaningful considering the short‐time frame and the stability of political attitudes. A change of 6–8 per cent in core political attitudes within a week is notable, especially given that our measure of EU support pertains to diffuse attachment, which is typically resistant to rapid shifts (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012). Nonetheless, border regions should be considered a ‘most likely case’ for observing the effects of border closures on political attitudes. Border residents are most directly affected by border closures, experiencing immediate disruptions to their daily lives and cross‐border interactions (Evrard et al., Reference Evrard, Nienaber and Sommaribas2020; Prokkola & Ridanpää, Reference Prokkola, Ridanpää, Brunn and Gilbreath2022; Wassenberg, Reference Wassenberg2020). The visibility and tangibility of border closures are highest in these areas, making the policy change more salient to local residents. Also, border regions often have stronger pre‐existing transnational networks and interactions, which are suddenly disrupted by closures. Given that we observe modest effects even in this most likely case, it suggests that the impact of border closures on political attitudes across the entire nation is likely to be smaller or non‐existent. This implies that while border closures may have localized effects on attitudes, their influence on national public opinion may be limited. However, it is important to note that border regions might also be more resilient to these changes due to their familiarity with cross‐border dynamics. The short‐lived nature of the observed effects could indicate that border residents adapt quickly to such disruptions (e.g., see Andersen & Prokkola, Reference Andersen, Prokkola, Andersen and Prokkola2021b; Prokkola & Ridanpää, Reference Prokkola, Ridanpää, Brunn and Gilbreath2022).

The limited empirical support for our hypotheses might also stem from the operationalization of our main dependent variables. While SOEP offers fine‐grained data on respondents’ residences, it limits our choice of attitudinal variables. For instance, intra‐European border closures might especially impact attitudes towards immigrants from neighbouring countries or mobile Europeans (Marín et al., Reference Marín, Rapp, Adam, James and Manatschal2021), but our SOEP wave only included items pertaining to refugees. Moreover, SOEP's single item on diffuse EU support is less likely to fluctuate in the short term compared to more specific forms of support like EU government satisfaction and policy support (Norris, Reference Norris1997). Hence, any change in diffuse support we observe should increase our confidence that specific support would show even more significant changes.

Moreover, individual heterogeneity in response to the border closures might have clouded our results. Reactions may vary depending on factors such as whether individuals are cross‐border commuters or have been personally infected with the virus (Ferwerda et al., Reference Ferwerda, Magni, Hooghe and Marks2023; Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012). Hence, while our research focuses on aggregate relationships through DiD analyses, which makes it difficult to study individual heterogeneity, future studies could explore individual heterogeneity in responses to border closures. Additionally, examining actual behaviours, such as mobility and compliance with restrictions, could provide deeper insights into the mechanisms underlying the observed effects. In our study, this was not possible due to data limitations. Lastly, we only take the official border policies at the respective border into account, indicating a start and end date for the measure. A valid point of criticism is that the reality of these measures may have differed significantly in practice, with potential variations in how border closures were implemented locally. Ideally, incorporating such information into the analysis would enhance its depth. However, obtaining such data through first‐hand accounts or media reports remains challenging.

Even so, it remains possible that the significant effects that we observed are endogenous, with border closures potentially being a reaction to pre‐existing outgroup hostility and low EU support rather than causing them (Kenwick & Simmons, Reference Kenwick and Simmons2020). However, a recent study (Freudlsperger et al., Reference Freudlsperger, Lipps, Nasr, Schilpp, Schimmelfennig and Yildirim2024) indicates that Schengen border closures during the COVID pandemic were driven by the pandemic's spread rather than public opinion. Furthermore, our DiD design allows us to detect changes in attitudes in response to prior border closures rather than merely showing correlations.

This study offers several substantive implications for EU politics. Although border regions are often considered ‘most likely cases’ for observing positive effects of European integration, our findings show that crisis‐induced border closures can temporarily disrupt these attitudes. The short‐lived nature of the observed effects highlights the importance of considering temporal dimensions when studying policy impacts. This suggests that public opinion in the EU context can be quite responsive to immediate policy changes but also resilient in the longer term. Consequently, the differential effects observed across regions highlight the importance of considering local contexts when studying EU‐wide phenomena. Finally, the study illuminates how national‐level decisions (border closures) can have implications for attitudes towards supranational institutions (EU support), underscoring the complex interrelationship between different levels of governance in the EU.

Our findings contribute to the wider scholarly debate on the effects of border policies on political attitudes towards immigrants. Contrary to our expectations and findings, some scholars argue that implementing stricter border controls helps mitigating hostility towards immigration because these measures signal that the government is gaining control over immigrant entries (Alrababah et al., Reference Alrababah, Beerli, Hangartner and Ward2024; Briggs & Solodoch, Reference Briggs and Solodoch2024; Solodoch, Reference Solodoch2021). For example, the EU–Turkey agreement was found to significantly reduce public opposition to immigration in Germany (Seimel, Reference Seimel2024; Solodoch, Reference Solodoch2021). How can we explain these divergent effects? The ultimate goal of the EU‐Turkey deal was to get control over an unprecedented increase in immigration (Seimel, Reference Seimel2024), whereas the goal of the COVID‐related closures was aimed at reducing the spread of the virus. Hence, while the Turkey deal might have signalled control over unwanted immigration, the measures in 2020 rather signalled that immigrants and other people crossing the border bring in the virus. In other words, the impact of border closures is not one‐size‐fits‐all, and lessons drawn from controlling migration may not readily apply to health‐driven scenarios, highlighting the importance of context when generalizing such findings.

Our study shows how border closures during crises serve as control signals that can shape public perceptions of external threats and national governance. Policymakers must recognize the symbolic implications of their decisions, ensuring effective communication about the rationale behind such measures to maintain public trust. Furthermore, policymakers should develop crisis management frameworks that align national actions with EU values and goals, reinforcing the importance of collective responses to shared challenges while being mindful of the local contexts that shape public attitudes. By integrating these strategies, policymakers can better navigate public sentiment and enhance support for both national and EU‐level initiatives during crises.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Socio‐Economic Panel (SOEP) at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) in Berlin and their staff for providing the data and the necessary research infrastructure. We are grateful for the valuable feedback received from participants and discussants at the EPSA 2023 and MPSA 2023 conferences, as well as workshops held at the University of Gothenburg, University of Warsaw, ARENA at the University of Oslo and the Robert Schuman Centre at the European University Institute (EUI). Additionally, we extend our gratitude to the editors and the anonymous reviewers whose insightful comments significantly improved this paper. We gratefully acknowledge funding from the VolkswagenStiftung (Grant: 9B051) in support of the COVIDEU project, upon which this article is based.

Funding information

VolkswagenStiftung (Grant: 9B051) in support of the COVIDEU project.

Data Availability Statement

We use the SOEP‐Core v37 dataset for our analysis. Due to the use of fine‐grained regional data and GDPR compliance regulations, this dataset can only be accessed onsite at the German Socio‐Economic Panel (SOEP) (2022) facilities in Berlin. Therefore, the replication scripts provided here can largely only be executed on‐site.

The replication materials, including scripts and additional datasets used in our analysis, are publicly accessible via Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/4NWUDL).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix A: Attention to border closures

Online Appendix B: Summary statistics

Online Appendix C: Alternative Models

Online Appendix D: Robustness Checks

Online Appendix E: Covariate Balancing Analysis