Introduction

Consuming a varied, nutrient-dense, and balanced diet is fundamental for optimal child growth and development and helps reduce the risk of diet-related chronic diseases.(Reference Nishida, Uauy and Kumanyika1,Reference Uauy, Kain and Mericq2) However, focusing solely on food intake overlooks the crucial role of the environments in which children consume their food. The environments and experiences that a child encounters during the early years of their life help set the foundation for their future health and well-being.(Reference Miguel, Pereira and Silveira3,Reference Tierney and Nelson4) Over half of Canadian children under the age of six years old are attending child care programmes,(5) and meals and snacks are typically a regular part of the daily routine. Early childhood educators working in child care have a key role in ensuring children’s early food and feeding experiences are positive and health-promoting through their practices and the resulting broader environment. Regulated child care programmes across Canada are required to follow nutrition standards that align with the national Canada’s Food Guide recommendations.(6) In addition to the requirements on what children should be served, nutrition standards in child care programmes often encourage responsive feeding practices to promote a healthy relationship with food, such as meal routines, family-style meals, and caregiver engagement.(7,8) Responsive feeding is multi-faceted and consequently, the definitions of responsive feeding in the literature vary.(Reference Black and Aboud9–Reference Satter14) Largely, a responsive feeding environment includes practices that validate children’s ability to self-regulate their food intake by encouraging them to adhere to their internal hunger and satiety cues, which can strengthen a child’s self-efficacy, self-regulation and emotional management.(Reference Black and Aboud9,Reference Daniels15,Reference Haines, Haycraft and Lytle16) Other practices often associated with a responsive feeding environment include avoiding using food as a reward,(Reference Ward, Hales and Haverly17–Reference Tovar, Vaughn and Fisher19) role-modelling eating behaviour, and having positive conversations throughout mealtime.(Reference Dev, McBride and Harrison20)

Although children are born with the innate ability to self-regulate their food intake and nutrition standards in child care promote aspects of responsive feeding, there is a knowledge-to-action gap in implementing responsive feeding environments.(Reference McIsaac, MacQuarrie and Barich21,Reference McIsaac, Richard and Turner22) Caregivers, including early childhood educators, often override children’s cues by restricting certain foods, controlling children’s food intake, or using food as a reward.(Reference Black and Aboud9,Reference McIsaac, Richard and Turner22–Reference Byrne, Baxter and Irvine24) These behaviours may be influenced by the caregiver’s social and cultural beliefs around food and feeding(Reference Dev, Speirs and McBride25,Reference Redsell, Slater and Rose26) or due to their limited time or resources.(Reference Black and Aboud9,Reference McIsaac, Richard and Turner22,Reference Wood, Blissett and Brunstrom27) Previous interventions that address responsive feeding often focus on parent practices(Reference Daniels15,Reference Redsell, Slater and Rose26) or only on one or two components of a responsive feeding environment, such as encouraging food exploration,(Reference Coulthard and Sealy28) using neutral language,(Reference Barrett, Moding and Flesher29) or language surrounding praise or pressure(Reference Ramsay, Branen and Fletcher30–Reference Smith, Dev and Hasnin32). Other comprehensive feeding practice interventions in child care have been found to be effective, but evaluated only one meal time(Reference Sleet, Sisson and Dev33,Reference Belza, Herrán and Anguera34) or only assessed educator perceived changes in behaviours(Reference Dev, Dzewaltowski and Hasnin35) rather than direct observation. Since a responsive feeding environment is multi-faceted and made up of many components that are influenced by a variety of behaviours throughout the whole day and environment, a comprehensive intervention is needed that considers the various influences on responsive feeding.(Reference Metz, Halle and Bartley36)

A recent scoping review identified the behavioural components of the interventions that support responsive feeding in child care but an overall gap in the explicit use of behaviour change science to inform implementation.(Reference McIsaac, MacQuarrie and Barich21) The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) is an established theoretical framework developed by Michie et al.(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West37) that offers a systematic approach to developing multilayered behaviour change interventions. The BCW has been successfully used in responsive feeding interventions aimed at parents,(Reference Russell, Denney-Wilson and Laws38,Reference Markides, Hesketh and Maddison39) however, its application to support responsive feeding in child care programmes is a novel endeavour. Given that young children spend a significant amount of time in child care environments, which impacts what food they consume and how it is offered, and are influenced by multiple practices and environmental components, behaviour change interventions for educators are needed. The purpose of this study is to determine the effects of a six-month intensive, BCW feasibility coaching intervention on the responsive feeding environments of child care centres.

Methods

Design and participants

Coaching in Early Learning Environments to Build a Responsive Approach to Eating and Feeding (CELEBRATE Feeding) was a behaviour change feasibility study conducted in two east coast provinces of Canada (Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island). Its primary objective was to enhance the practice of responsive feeding in child care settings through a coaching intervention based on practices that promote responsive feeding environments.(Reference McIsaac, MacQuarrie and Barich21) To address the complexity and various concepts included in a responsive feeding environment in child care settings, the CELEBRATE Feeding Approach was created.(Reference Rossiter, Young and Dickson40) It is a flexible framework that enhances previous concepts of responsive feeding and emphasises support for educators in implementing responsive feeding practices, fostering children’s autonomy, confidence, and self-regulation not only during meals but also through play and language surrounding food throughout the day. The CELEBRATE Feeding Approach emphasises the significance of language, play, diversity, inclusivity, and celebration in early learning environments by highlighting 13 actionable behaviours that early childhood educators can carry out to promote responsive feeding in child care settings.(Reference Rossiter, Young and Dickson40) This approach to responsive feeding is designed to facilitate children’s exposure to a wide range of foods through various methods in a predictable, secure, and supportive environment. Importantly, it does not pressure children to eat specific amounts of particular foods. Ultimately, the aim is to cultivate children’s openness to diverse foods, strengthen self-regulation, and develop the foundation for a lifelong positive relationship with food.

The current feasibility study compares data collected from child care centres before and after participating in the six-month CELEBRATE Feeding coaching intervention. The study initially involved nine child care centres, with dedicated coaching in two rooms per centre, comprising of 18 child care rooms in total. The age groups of children in each room were varied and included infants (<18 months), toddlers (18 months – <3 years), preschool (3–5 years), and mixed age groups (18 months–5 years). These centres were recruited through a public outreach effort, which included email and social media, to gauge interest in the study. Selection of the centres was based on their expressed interest and their capacity to engage in the intervention following an information session. This purposive selection process aimed to encourage a diverse representation, encompassing child care centres with varying licencing capacities (with a maximum capacity of up to 80 children) and a mix of demographics from different regions within the two provinces. The individual rooms coached at each centre were either the only two rooms or two rooms identified by the centre director. After the baseline data collection, one centre had to withdraw from the intervention due to staffing and structural limitations. Thus, eight centres with 16 rooms took part in the coaching intervention. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures were approved by the Prince Edward Island (REB# 6010388) and Mount Saint Vincent University’s Research Ethics Boards (REB# 2021–112). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants indicating which aspects of the study they consented to participate in (i.e. coaching, survey, observation, interviews).

CELEBRATE Feeding intervention

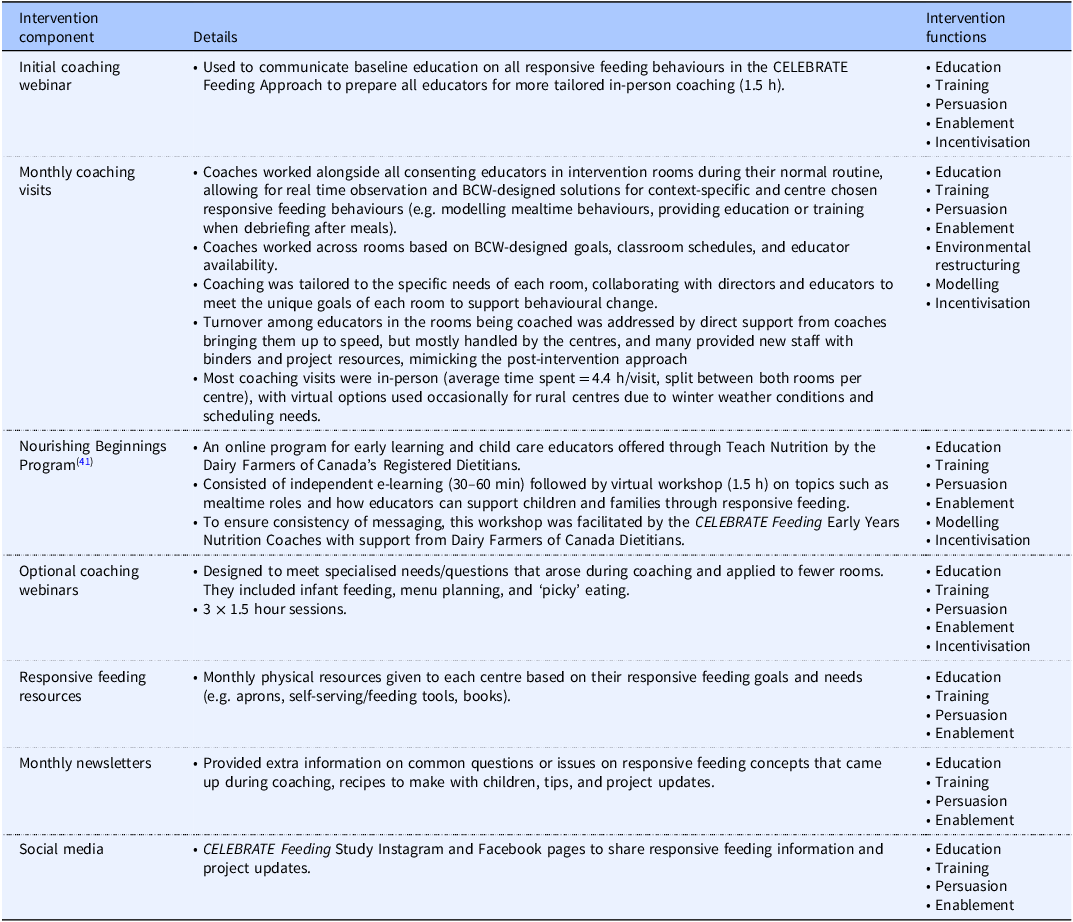

The CELEBRATE Feeding intervention was a six-month responsive feeding coaching intervention carried out by two early years nutrition coaches, both registered dietitians, one in Nova Scotia and one in Prince Edward Island. The intervention consisted of various components which are detailed in Table 1. Briefly, the director and consenting educators in each centre received a mandatory initial online coaching session on responsive feeding and the CELEBRATE Feeding Approach (1.5 h), 4–7 monthly coaching visits (mostly in-person with virtual visits supplementing due to winter weather conditions and scheduling, lasting an average of 4.4 h/visit, split between both rooms per centre, usually capturing both morning and afternoon snacks and lunch time), a mandatory Nourishing Beginnings(41) training module (30–60 min) and online session (1.5 h), three optional coaching webinars on specific topics, monthly resources and newsletters for responsive feeding, and access to responsive feeding information on our social media accounts. The coaches were also available to the centres and educators by email and phone whenever needed.

Table 1. CELEBRATE Feeding intervention components

The coaching intervention was based on a behaviour change system informed by the BCW.(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West37) This was accomplished by identifying desired behaviour outcomes and individualised goals of each room and centre and using a Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) analysis to determine the proper intervention strategies and policy categories to achieve these outcomes. The BCW employs the COM-B model as its core, aiming to enhance comprehension of the target behaviour. This involves assessing an individual’s ability to execute the behaviour, the circumstances enabling the behaviour, and the motivation behind performing the behaviour. There are various intervention functions provided by the BCW framework that are strategies that can be used in behaviour change interventions (i.e. education, modelling, persuasion, incentivisation, coercion, training, restriction, enablement, and environmental restructuring). Their use in coaching is determined by the educators’ desired CELEBRATE Feeding responsive feeding behaviours and goals, which aspects of the COM-B are able to be influenced, as well as the APEASE criteria (Acceptability, Practicability, Effectiveness, Affordability, Side-Effects, Equity),(Reference Michie, Atkins and West42) ensuring that the child care centre’s needs and context were considered and the coaching intervention was set up for success.

Data collection

Demographic data

Centre-level data were obtained from a survey filled out by each director and from postal codes of each centre. Educator demographic characteristics of those educators and directors that were involved in coaching (n = 74) (i.e. attended at least one online or one in-person coaching session) were obtained through an optional demographic survey, ensuring participation was voluntary on different levels and educators could still take part in and benefit from other intervention components.

Responsive feeding scoring

Comprehensive day-long observations were conducted at both baseline (July–September 2022) and follow-up (June–August 2023) across the two separate rooms within each participating child care centre (n = 18 rooms at baseline; n = 16 rooms at follow-up). Each observation was carried out by two trained research staff, always including the intervention coach (consistent across both data collection periods) and one other team member (four total). The observations were completed using a modified Environment and Policy Assessment and Observation (EPAO-2017) tool that is designed to assess responsive feeding practices and environments in child care centres.(Reference Ward, Hales and Haverly17,43) The modifications were made to align with the CELEBRATE Feeding Approach (Reference Rossiter, Young and Dickson40) and to create a scale called the CELEBRATE Feeding scale that allows for the nuances in scoring that come with multiple educators in each room and acknowledges the differences in frequency of the behaviours captured with the tool [see(Reference Campbell, McIsaac and Young44) for details on the modifications]. Instead of using the 0–1 (no/yes) values for the various observation items, the CELEBRATE Feeding scale was used to score behaviours based on frequency and breadth of practices, resulting in two 4-point scales (none, some, most, all, (of the educators), (of the time)), which captured more nuanced and detailed observation information to inform future coaching.(Reference Campbell, McIsaac and Young44) Rather than simply categorising the behaviour as occurring or not, this scale allowed the research team to quantify nuanced differences that inevitably occur between child care rooms and track progress more closely. However, some observation items were not subject to the breadth among educators and frequency of a behaviour (e.g. environmental observations, serving style, planned nutrition education) and required dichotomous scoring (yes/no) using the modified EPAO.(Reference Campbell, McIsaac and Young44) Altogether, the modified EPAO and CELEBRATE Feeding scale provided 21 behavioural or environmental components of responsive feeding that also aligned with our CELEBRATE Feeding Approach, with each scored from 0–3 (3 as best practice).

The observers were trained in the use of the modified EPAO tool prior to data collection and participated in piloting sessions where they practiced scoring sample observations and discussed areas of uncertainty until consistency was achieved. During data collection, each day of observation focused on one of the two intervention rooms, with observations starting before the morning snack and concluding after the afternoon snack, with a small break during the children’s rest time. The observers positioned themselves in distinct areas of the room and independently recorded raw notes in a non-judgemental manner about the room environment, mealtimes, activities, and interactions that related to the CELEBRATE Feeding Approach (Reference Rossiter, Young and Dickson40) to responsive feeding that may have occurred throughout the day. Because observers were positioned in different parts of the room, they may have noticed or heard different interactions; the subsequent discussions were therefore important not only for resolving discrepancies but also for integrating multiple perspectives. This process strengthened the final scoring by ensuring that the agreed-upon ratings reflected a more complete view of the classroom context. After the observation, the researchers individually typed up their raw notes and proceeded to complete the modified version of the EPAO, scoring the appropriate items on the CELEBRATE Feeding scale.(Reference Campbell, McIsaac and Young44) Once each researcher had finished their individual modified EPAO assessments, they convened to review and resolve any discrepancies in their scoring. They collectively agreed on scores, which were then documented in a final modified EPAO report.

Intervention implementation

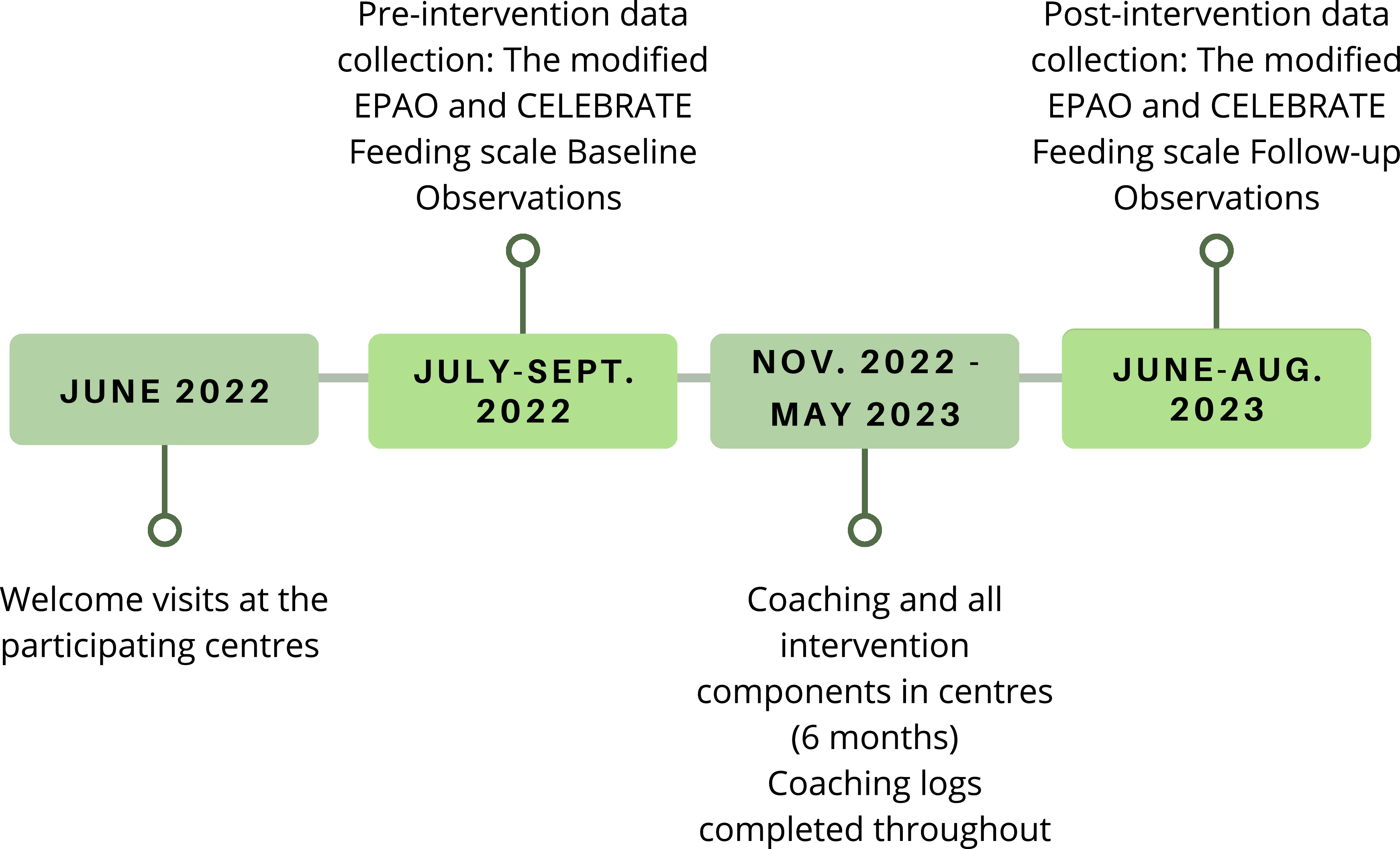

Before and throughout the intervention, the coaches diligently filled out a coaching log of all interactions they had with each centre and educator. They kept an up-to-date table that included information such as date, length, type (in-person, phone, email), purpose, who was involved, and a summary of the interaction/coaching visit, any resources they provided, action items, goals identified, and a reflexive journal to debrief the coach’s thoughts. The coaches also kept detailed notes on educator attendance for each coaching interaction and observation period. For each interaction, the coaches also filled out which intervention functions were employed, if any, during the interaction or visit. These measures were gathered to enable comparisons of the intervention across centres and rooms. Figure 1 provides a visual of the project’s timeline for data collection and the intervention components.

Figure 1. The CELEBRATE Feeding project’s timeline.

Data analysis

Demographic characteristics of participating centres, individual rooms, and educators/directors were obtained and analysed descriptively. Centres’ locations were classified per Statistics Canada’s Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016 using their postal code.(45) The Shapiro-Wilk test determined that the changes in observation scores was normally distributed (W = 0.916, P = .399). As such, independent samples t-tests and one-way ANOVAs were used to determine if demographics such as province, location, median after-tax household income of the centre location, and age group were related to changes in observation scores over time.

Responsive feeding scoring

The 21 relevant responsive feeding scores were calculated for both data collection time points based on the EPAO-2017 user manual(43) scoring details (0–3, where 3 is the most responsive score or ‘best practice’).

For both time points, each responsive feeding score was aggregated to derive an overall CELEBRATE Feeding scale score for each room, and also averaged across both rooms in each centre for an overall centre score, with a maximum possible score of 63 points. The average score and standard deviation across all rooms was also assessed. To identify specific areas of strength or areas that may need improvement, mean and standard deviation for each responsive feeding score across all rooms were calculated.

To assess the impact of the intervention on overall rooms’ scores (Shapiro-Wilk, P > 0.05) on the CELEBRATE Feeding scale over time, a paired samples t-test was conducted. A Pearson correlation coefficient was used to explore the relationship between the rooms’ baseline scores and the mean difference in scores post-intervention. To determine change in the individual responsive feeding scores across rooms over time, Wilcoxon signed rank tests were conducted, as most responsive feeding scores were non-normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk, P < 0.05). Adjustments for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction) were applied to reduce the risk of Type I error given the 21 separate tests.

Intervention implementation

To determine the total intervention time spent in each centre, we summed the time for active in-person and online coaching from the day the initial coaching session occurred to the last day of coaching. The number of in-person and total coaching sessions and intervention functions implemented were counted per centre. The proportion of each intervention function per centre was also determined. A content analysis(Reference Hsieh and Shannon46) of the coaching logs was completed to quantify which goal areas of focus were addressed most often across centres.

Educators in the rooms that were coached could elect to participate in different aspects of the intervention. Given the absence of a validated scale to measure participation in or dosage of our intervention, we developed a scale to provide a framework for assessing and comparing participant participation, recognising the importance of this aspect to the implementation of the intervention. The coaching participation scale was created from attendance kept and notes from the coaching logs to give each educator a score from 0–3, with 3 being the most engaged in the intervention. The scale was determined based on attendance and participation in both in-person and online coaching sessions. A score of 0 was given if the educator was not coached, a score of 1 if the educator was present during some in-person coaching visits but not actively being coached and attended 0-2 online sessions, a score of 2 if the educator was present during some in-person coaching visits but not actively being coached and attended 3 or more online sessions or if they participated in some coaching visits and attended 0–2 online coaching sessions, and a score of 3 if the educator participated in the majority of coaching sessions and attended 2 or more online coaching sessions. The average participation level of educators who were observed post-intervention was determined per room.

Additionally, many rooms experienced turnover in staffing due to educators moving to a different room or leaving the centre altogether. To calculate a value for turnover in each room, the number of educators that were observed at baseline but not at follow-up was divided by the number of educators observed at baseline.

Pearson correlation coefficients were used to explore how differences in the intervention per centre, such as total intervention time spent, number of in-person coaching sessions, and number of total coaching sessions may be related to change in overall centre scores (average of mean difference for both rooms per centre). Differences per room, such as average educator participation score, and percent turnover were also assessed in relation to difference in overall room scores using Pearson correlation coefficients. As not all percentage of intervention function variables were normally distributed, Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients were used to assess the relationship between change in overall centre scores and the percentage of each intervention function. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 27.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, USA).

Results

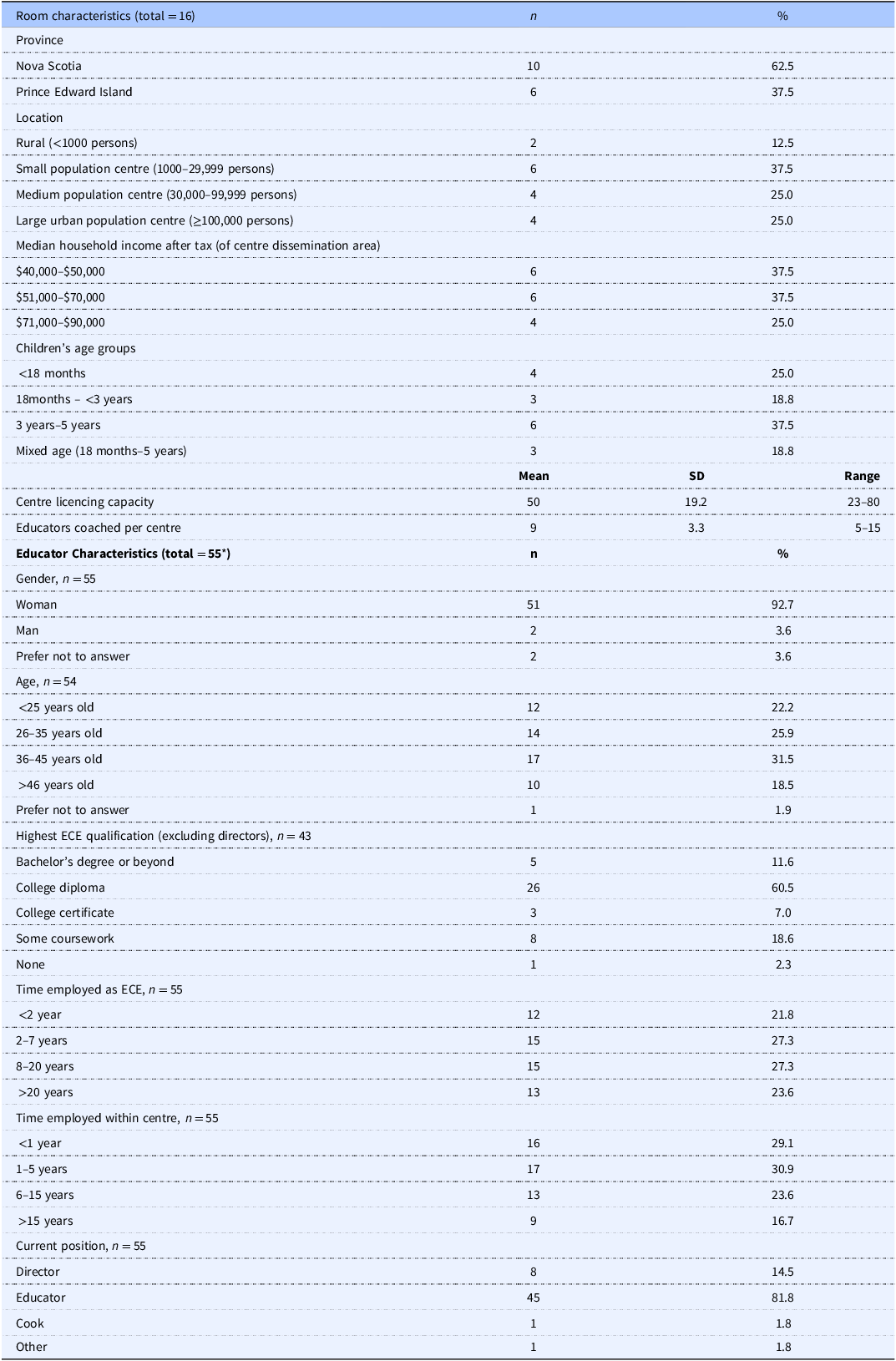

Table 2 presents the demographic characteristics of the rooms in each child care centre and the educators coached throughout the intervention. Of the eight centres observed at both time points, five were in Nova Scotia and three were in Prince Edward Island. The majority (37.5%) of centres were located in small population centres (1,000–29,999 people) and were located in areas that were relatively evenly split amongst range of median household income after tax and 37.5% of rooms observed in the centres were of the preschool (3years–5years) age group. The mean licencing capacity of all centres was 50 children. Overall differences in responsive feeding scores were not related to province, location, median household income, age group, or licencing capacity. Of those educators who were coached (n = 74, M = 9 per centre), 55 (74.3%) had completed the demographic survey. All but two were women (92.7%), the majority were between 36–45 years old (31.5%), held college diplomas in ECE (60.5%), and were currently in an educator position (81.8%). The time employed as an ECE and employed at the current centre were evenly divided amongst time categories.

Table 2. Room and educator demographics

* Indicates that this number represents educators who were coached and who opted to complete the demographic survey. ECE, Early Childhood Education.

Responsive feeding scoring

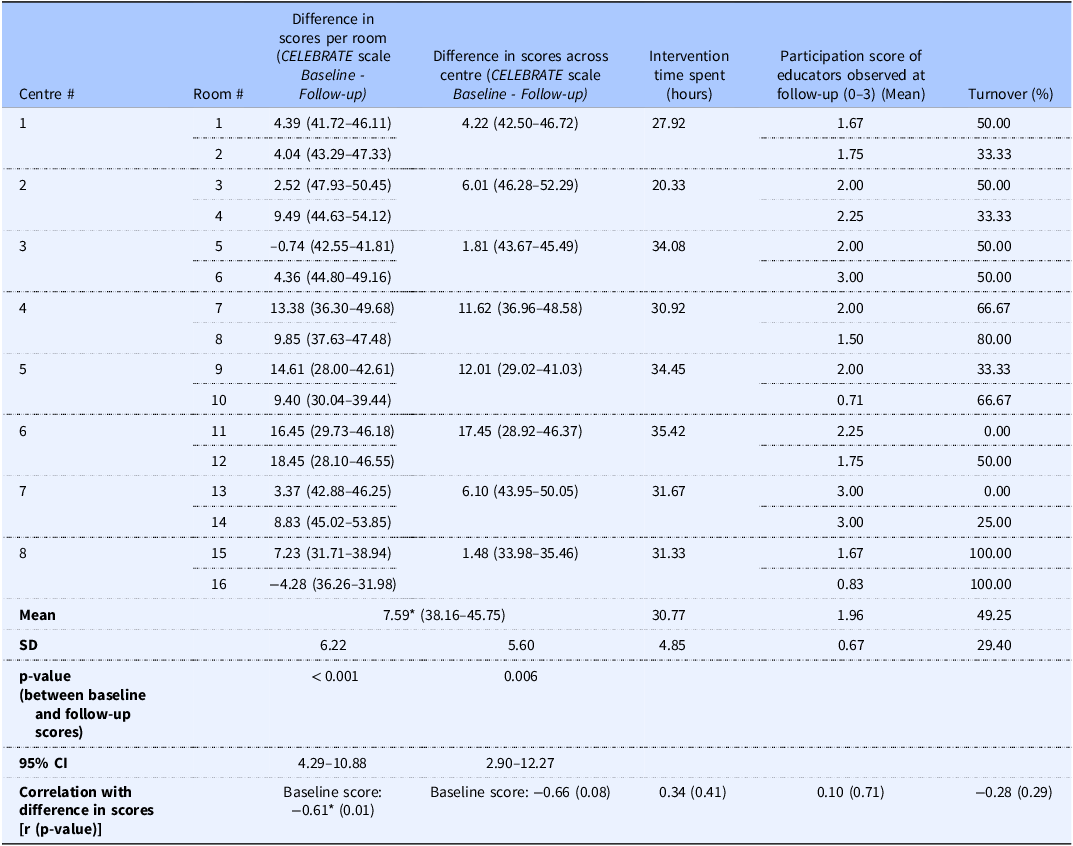

Table 3 provides each centre’s and corresponding room’s differences in overall responsive feeding scores at baseline and follow-up. Paired-samples t-tests were conducted to evaluate the impact of the intervention on room and centre average scores on the CELEBRATE Feeding scale. There was a statistically significant increase in the room scores from baseline (M = 38.16, SD = 6.55) to follow-up after the intervention (M = 45.75, SD = 5.87), t (15) = 4.91, P < 0.001. The mean increase in the CELEBRATE Feeding scale scores was 7.59 with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) ranging from 4.29–10.88. The Cohen’s D statistic (1.23) indicated a large effect size. All but two rooms increased their score from baseline to follow-up, with the largest increase in score in room #12 with an 18.45-point increase. The highest scoring room was #4 at 54.12, which is 6.19 points higher than the highest score at baseline. The lowest scoring room was #16 at 31.98, however this is 3.98 points higher than the lowest scoring room at baseline. Overall centre scores were also significantly higher, t (7) = 3.83, P = 0.006, with a 95% CI ranging from 2.90–12.27. Cohen’s D statistic (1.35) indicated a large effect size. The baseline overall room scores were strongly and negatively correlated with the mean difference in scores r = −0.61, P = 0.012, such that higher baseline scores were related to lower mean difference in scores. The average baseline score per centre was not significantly correlated with mean difference in scores per centre, r = −0.66, P = 0.07.

Table 3. Responsive feeding scores and intervention implementation details per centre and room

* Significant at the P < 0.05 level.

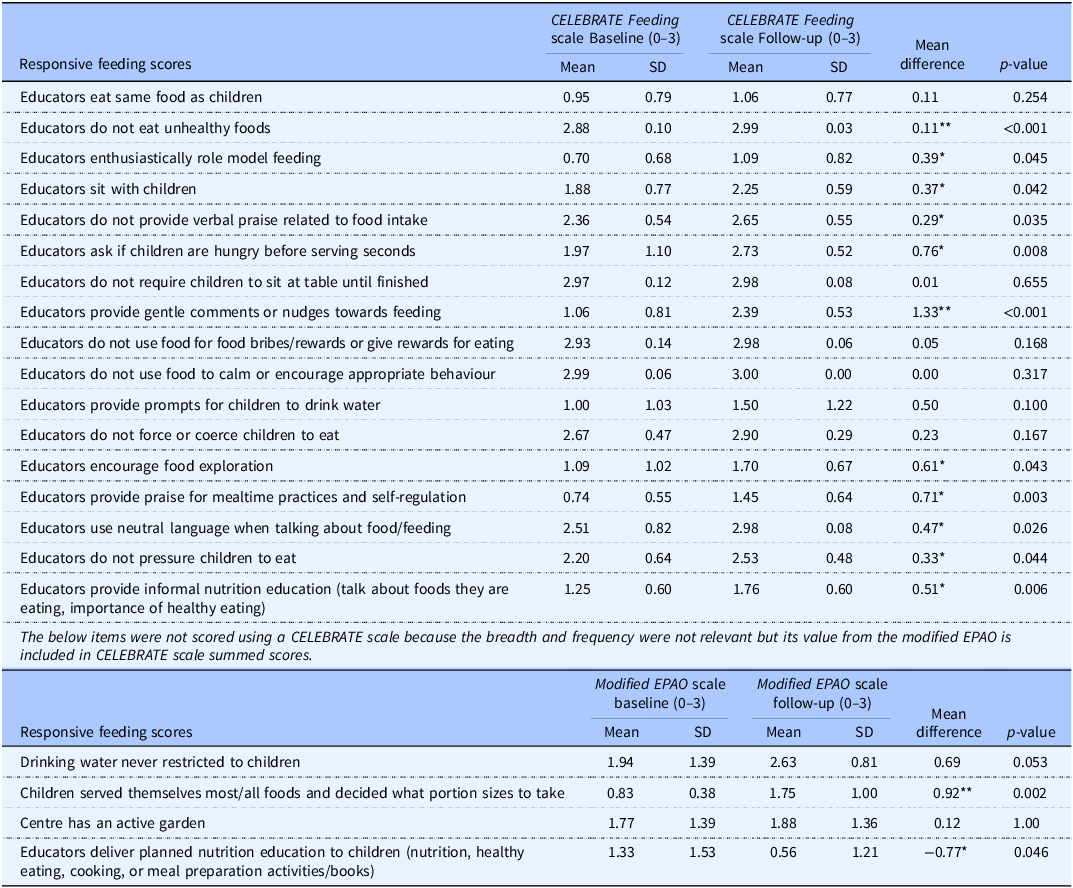

Table 4 presents the average scoring across all rooms of each responsive feeding score at both time points. Wilcoxon signed rank tests were conducted to determine the effect of the intervention on each of the 21 responsive feeding scores and Bonferroni corrections were applied (p < 0.002). Thirteen of the 21 scores were significantly different at the P < 0.05 level at follow-up, where 12 of these were significantly more responsive after the intervention; and only three scores were significant at the P < 0.002 level, including ‘Educators provide gentle comments or nudges towards feeding’, ‘Children served themselves most/all foods and decided what portion sizes to take,’ and ‘Educators do not eat unhealthy foods.’ Other behaviours with notable improvements included ‘Educators ask if children are hungry before serving seconds’, ‘Educators encourage food exploration’, ‘Educators provide praise for mealtime practices and self-regulation’, ‘Educators provide informal nutrition education’, and ‘Drinking water is never restricted to children’. The only behaviour to become less responsive was ‘Educators deliver planned nutrition education to children’, with a mean difference of −0.77, P = 0.046, although this score was quite low to begin with and was not identified as a priority for centres due to the play-based nature of the child care programmes.

Table 4. Scoring per responsive feeding item across rooms at baseline and follow-up (n = 16)

Mean values were significantly different from baseline to follow-up:

* p values indicate behaviours that were significantly different at the P < 0.05 level before applying the Bonferroni correction. After applying the Bonferroni correction (adjusted alpha = 0.0024),

** indicates P < 0.002.

Intervention implementation

Table 3 also outlines the intervention implementation details (time spent, participation score of educators observed at follow-up, and percent turnover) captured in the coaching logs by centres and rooms. Throughout the six-month intervention, the coaches spent an average of about 31 h coaching each centre, with an average of 10.75 coaching sessions (5.13 in-person visits) per centre. Of those educators observed at follow-up, the average participation score (out of 3) was 1.96 and the average percent turnover in rooms was 49.25%. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no educator left the study for reasons related to the study. Pearson correlations showed that intervention time spent (r = 0.34, P = 0.408), total coaching visits (r = 0.311, P = 0.453), in-person coaching (r = −0.266, P = 0.524), mean participation score of educators observed at follow-up (r = 0.10, P = 0.712), and percent turnover (r = −0.28, P = 0.291) were not significantly correlated with change in overall scores per centre and room. The content analysis created six overarching categories of goal areas of focus across centres, with the most frequently addressed category being the mealtime environment and routine, followed by children’s self-regulation, language at mealtime, food exposure and exploration, adjustments to the menu, and least addressed was peer and parent support.

Figure 2 displays the breakdown of all the intervention functions employed per centre during coaching. All intervention functions were used to influence educators’ responsive feeding behaviours except restriction and coercion in each centre. Education and persuasion were the most frequent intervention functions used, while modelling was the least frequent intervention function used. Spearman’s correlations found no significant correlations between the percentages of each intervention function and the mean difference in scores except for the percent modelling used, where it was strongly negatively related to mean difference in scores (rho = −0.74, P = 0.037).

Figure 2. The proportion of each intervention function used at each centre during the six-month intervention.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of a 6-month behaviour change coaching intervention on the responsive feeding environments and practices of child care centres. The CELEBRATE Feeding Approach offered a framework to target responsive feeding behaviours for nutrition coaches who developed meaningful interventions based on centre priorities and behavioural influences. Baseline observations informed the development of goals, alongside considerations from APEASE (Acceptability, Practicability, Effectiveness, Affordability, Side-Effects, Equity) to ensure that the unique context and realities of child care centres were incorporated into intervention goals and implementation strategies applied by the coaches. Results indicate that this approach to coaching was successful, as all but two rooms increased their overall responsive feeding score, and the intervention resulted in an increase in all but one of the 21 responsive feeding scores with a significant increase in 12 of these scores.

The overall average responsive feeding score of all rooms was found to be significantly higher post-intervention than at baseline, with some rooms increasing more than others. Time spent coaching each centre, the number of in-person coaching visits, and the total number of coaching sessions (based on each room or centre’s needs and goals) were not related to the mean difference in scores per centre. While variation in educator participation in coaching sessions and staff turnover may have contributed to differences in scores, neither variable was significantly correlated with changes in responsive feeding scores. Notably, the room with the lowest post-intervention score had low educator participation and high turnover. Participation and turnover themselves were significantly negatively correlated (r = −0.677, P = 0.004), highlighting that centres with higher turnover tended to have lower educator participation, but these scores did not directly translate into statistically significant differences in outcome scores. Observed lower participation may have been influenced by language barriers, lower buy-in to the approach, and less leadership from experienced educators, as expressed in the coaching logs. Kenney et al.(Reference Kenney, Mozaffarian and Ji47) study related to an obesity prevention policy in early childhood education also found that staff turnover impeded the uptake of the intervention as staff had to be constantly re-trained. Staff turnover is a reality of child care; thus, finding ways of sustaining the practices learned throughout the intervention is paramount. This may be accomplished by working with new staff through regular training opportunities, such as during staff meetings,(Reference Byrne, Baxter and Irvine24) having leadership within the centre bought in to the approach, and identifying champions from within the centre to carry on the work.(Reference Chan, Hyde-Page and Phongsavan48–Reference Shoesmith, Hall and Wolfenden51)

The proportion of each intervention function used per centre was not correlated with changes in centres’ scores, as centres received very similar amounts of each. The only exception to this was for the intervention function modelling. The centres that received the highest percent of ‘modelling’ were two of the highest scoring at baseline and the lowest change in score; this might have occurred because coaches did not need to incentivise or persuade these educators to change behaviour because they had already demonstrated valuing of a responsive feeding approach. As a result, there might have been more receptiveness to modelling as an intervention function so that the coach could demonstrate and clarify the practice. Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)(Reference Bandura52) may help explain this, such that individuals are more likely to adopt behaviours if they value them and expect positive outcomes. When educators already value and understand a behaviour, they may be more open to observing authoritative figures like coaches model it. This observation reinforces their beliefs and self-efficacy, making them more receptive to adopting the behaviour themselves.(Reference Sheeshka, Woolcott and Mackinnon53) Further, counting the implementation of intervention functions may be a more limited way of reporting coaching practice as it might misrepresent the influence of different functions. For instance, modelling and environmental restructuring were the least frequently reported; however, they may have made more of an influence on overall changes in behaviour without requiring repetition. Differently, education, persuasion, and enablement were functions that were repeatedly used, in all intervention components, as new information about behaviours, their impact on children’s feeding, and goal setting was introduced each visit. Further, in addition to individual use of intervention functions, it may also be important to consider the use and interaction of the various functions together. In a systematic review of child and maternal nutrition interventions that used BCW intervention functions, researchers found that none of the 79 studies used restriction or coercion in their interventions, similar to the current intervention, and that interventions that used more than two intervention functions were most effective.(Reference Watson, Mushamiri and Beeri54) As a whole, this intervention reinforced that providing information through education and training alone is not sufficient.(Reference Golden and Earp55) Although this supports knowledge building for educators, it was important to consider other intervention functions, adapted to the needs of each room and centre, that build toward supporting the capability, opportunity, and motivation to implement responsive feeding behaviours.

The main differences observed in the scores across rooms seemed to be influenced by their baseline score. Those who had lower scores at baseline had more room to grow, such that baseline scores were negatively correlated with changes in scores. This finding emphasises the importance of personalised approaches to intervention delivery and optimising coaching strategies for settings with different levels of responsive feeding to begin with. An approach such as this may be especially important for those in such a busy and demanding profession with a longstanding history of being unappreciated and underpaid, such as early childhood education.(Reference Saulnier and Frank56) Further, the CELEBRATE Feeding Approach emphasises the interrelatedness of language and mealtime routines; once one behaviour is well-established, there are spillover effects across many other behaviours leading to an increased score. For example, having educators sit with the children and allowing the children to serve themselves would increase those specific scores, but also impact scores related to the language about serving children like not forcing or pressuring them to eat and role-modelling eating behaviours. In the CELEBRATE Feeding Approach there is an emphasis on relinquishing the caregiver’s control of children’s intake by acknowledging the critical role of children in deciding ‘if and how much’ to eat.(57) Once caregivers have the belief in their role in the feeding environment (motivation), they are more easily supported through interventions that support capacity building (capability) and environmental changes (opportunity).(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West37)

Some of the responsive feeding scores that were not as often addressed as centre priorities through the coaching intervention were planned nutrition education, having a centre garden, prompts to drink and not restricting water, and behaviours that centres were already doing quite well in the beginning. From our analysis of the baseline observation data, we identified that the centres’ highest scores were practices that focused on what not to do, such as not forcing or coercing children to eat, not using food for rewards and bribes, and not requiring children to sit at the table until they finished their food.(Reference Campbell, McIsaac and Young44) An assessment of feeding practices and environments in Australian daycare contexts also observed that educators were achieving scores closer to best practice by not using negative practices like coercion, pressure, and bribery.(Reference Kerr, Kelly and Hammersley58) These studies highlight that educators may find it easier to stop a behaviour than start a new one, and they often understand which behaviours are harmful; thus, coaching is needed to explore the positive, health-promoting practices that educators may be less aware of or lack the skills and resources to accomplish. Because these behaviours did not come up as goals for the centres or rooms, they were not a priority to address and, therefore, did not achieve significant favourable changes due to the intervention.

Strengths of this study include the quality of the early years nutrition coaches who were both registered dietitians, which has previously been reported as beneficial given their specialised expertise.(Reference Bell, Hendrie and Hartley59,Reference Lyn, Evers and Davis60) Additionally, at least one trained observer in each room was the same at each time point of data collection, ensuring consistency in data collection methods and interpretation of observed behaviours. Although there was a relatively small sample size, the centres and individual rooms coached were diverse in size, location, and age groups, providing evidence for success in a range of contexts. Last, the study employed a four-point CELEBRATE Feeding scale to record more detail and nuance in the scores than the dichotomous version of the EPAO-2017. This allowed for the capture of subtle changes in behaviour and environment, such as a behaviour occurring ‘some of the time’ pre-intervention to ‘most of the time’ post-intervention. One limitation with scoring to track improvements in certain behaviours is that it might not show if a behaviour is happening more post-intervention if it was already being done consistently by all educators all the time. For example, if, before the intervention, all educators in a room always used neutral language when talking about food, they would have received a score of 3. However, after the intervention, if they are using neutral language even more frequently, the scores would not show that improvement as they were already at the maximum score.

As this study was a feasibility study using a pre-post intervention design, we cannot attribute all changes in scores to the intervention. Employing more robust study designs, such as randomised controlled trials with control groups could provide stronger evidence of causal relationships between interventions and outcomes; however, such designs are often not feasible among real-world interventions.(Reference Glasgow, Lichtenstein and Marcus61) Further, because the observations only occurred on one day, it is possible they did not capture usual practices, or that educators altered their behaviour while observers were present, leading to potential social desirability bias.(Reference Bergen and Labonté62) Another limitation of the design is that many of the responsive feeding behaviour scores are based on educator behaviours, where in some centres and rooms, these were not the same educators at both time points. This was due to staff turnover, vacation, or shuffling of educators into different rooms. Future work could consider identifying certain educators and following them and their behaviours over time rather than the room they were in, with the caveat that responsive feeding environments include educator behaviours but also the environment within the room or centre. Similarly, while coaching occurred in specific classrooms, coaching hours were recorded at the programme/centre level due to the transient nature of child care (children and staff frequently moving between rooms). This limited our ability to report coaching exposure at the classroom level and should be considered in interpreting findings. Additionally, this study took place in centres and rooms that were purposively selected and were keen to take part in the study. This allowed for buy-in of the CELEBRATE Feeding Approach, and relatively good engagement from educators. Therefore, behaviour change may not be as successful among centres who are less familiar with and do not value responsive feeding.

Conclusion

The CELEBRATE Feeding coaching intervention was successful in creating more responsive feeding practices and environments in child care settings. Scores improved the most in areas most often identified through coaching goals and in areas with the lowest scores to begin with. Using a BCW approach to coaching, creating relationships with the centres and educators through in-person coaching, and working with the centres to identify areas of improvement and goal setting allowed for positive intervention outcomes, moving toward more responsive feeding environments. Future work could continue using the CELEBRATE Feeding Approach to encourage responsive feeding practices and environments and continue to employ the BCW within behaviour change interventions. Additional research could also be explored to identify how CELEBRATE Feeding could be scaled up to sustain and provide more widespread responsive feeding coaching to other child care environments.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the child care centres for their enthusiastic participation in the CELEBRATE Feeding project, members of our research advisory committee made up of project investigators and government partners (health and education departments and health authorities), and research team members Elizabeth Dickson, Rachel Barich and Heather Podanovitch for their support with the project.

Author contribution

All authors had input into the design and conduct of this study. J.E.C., M.Y., and S.C. collected the data. J.E.C. completed data analysis with help from O.L. and drafted the manuscript with the help of S.C. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Financial support

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (J.L.D.M., M.D.R., Award # 173374), the Foundation J-Louis Lévesque (M.D.R.) and was also undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program (J.L.D.M).

Competing interests

The authors declare a potential perceived conflict of interest. The Nourishing Beginnings program was developed and delivered by Registered Dietitians from Dairy Farmers of Canada, and the CELEBRATE Feeding Early Years Nutrition Coaches facilitated the workshops with support from Dairy Farmers of Canada Dietitians. No authors or project staff received personal financial benefit from Dairy Farmers of Canada related to this work. While Dairy Farmers of Canada is an industry group, the program content was designed to align with evidence-based responsive feeding and child nutrition guidelines.