LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

-

understand and recognise the distinct clinical features, diagnostic criteria and sensory profiles of visual snow syndrome and exploding head syndrome

-

understand the application of structured clinical approaches to the assessment, investigation and diagnosis of patients presenting with unexplained visual or auditory perceptual disturbances

-

demonstrate an understanding of individualised management strategies that incorporate psychoeducation, multidisciplinary referrals and evidence-based pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for these rare perceptual disorders.

Perceptual disturbances are central to many psychiatric disorders, for example manifesting as hallucinations in psychosis or illusions in delirium. These symptoms are clinically significant because they frequently drive diagnostic decision-making in acute and chronic psychiatric settings. Although such phenomena are typically associated with classic psychiatric syndromes, a number of rare, non-psychotic perceptual conditions have emerged in the literature that challenge conventional diagnostic boundaries and may present to psychiatric services because of their unusual sensory profiles and associated distress, despite their distinct neurobiological underpinnings.

Visual snow syndrome (VSS) and exploding head syndrome (EHS) are two examples of these rare conditions. Respectively affecting visual and auditory perception, they share many similarities in terms of management and pathophysiological theories. This article aims to demonstrate how the conditions can be recognised, with an overview of the recent literature, especially those aspects that are of relevance to psychiatrists. The case vignettes used in this article are fictitious.

Visual snow syndrome

Case vignette

A 49-year-old man with no significant psychiatric or neurological history presented with a gradual onset of persistent visual disturbances over 4–5 years. He described the symptoms as continuous visual ‘static’ over his entire visual field. The disturbance worsened in low-light environments, but improved slightly with increased illumination. His visual symptoms were invariably preceded by a single episode of full-field black and white zig-zag lines that resolved within seconds. In addition to the static, he reported photophobia, light sensitivity, afterimages, floaters and occasional tiny purple blobs. He denied visual trailing, hallucinations, migraines and headaches. Neurological and ophthalmological examinations and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were normal. Extensive laboratory testing was unremarkable. Psychiatrically, he had no current symptoms and functioned well academically and socially.

Clinical presentation and diagnostic criteria of VSS

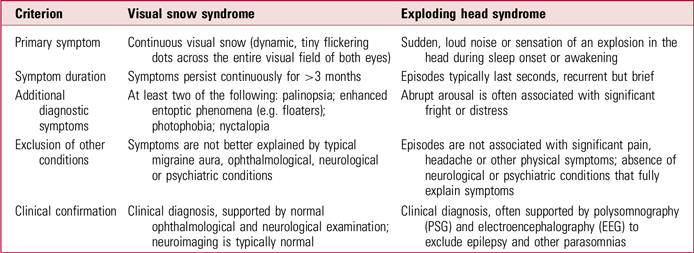

Visual snow syndrome (VSS) is a visual perceptual disorder characterised by a persistent perception of visual static across the entire visual field of both eyes (Schankin Reference Schankin, Maniyar and Digre2014; Aeschlimann Reference Aeschlimann, Klein and Schankin2024). These continuous, dynamic, tiny flickering dots are often likened to the ‘static’ on an untuned analogue television screen (Barral Reference Barral, Martins Silva and García-Azorín2023; Rusztyn Reference Rusztyn, Stańska and Torbus2023; Chojdak-Łukasiewicz Reference Chojdak-Łukasiewicz and Dziadkowiak2024). VSS can occur with additional visual symptoms (Fig. 1), such as palinopsia (the persistent or recurring afterimage of an object after it has been removed from view), entoptic phenomena (visual effects originating within the eye itself, such as seeing floaters, flashes or blue field entoptic dots), photophobia (abnormal sensitivity or discomfort to light) and nyctalopia (difficulty seeing in low-light or night-time conditions) (Puledda Reference Puledda and Goadsby2022; Brooks Reference Brooks, Chan and Fielding2024).

FIG 1 Illustrations to demonstrate symptoms of visual snow syndrome. (a) ‘Visual snow’ (tiny dynamic flickering dots in the entire visual field) in the dark; (b) visual snow during the day; (c) floaters; (d) palinopsia (‘trailing’); (e) blue field entoptic phenomenon; (f) palinopsia (positive afterimages). From Schankin et al (Reference Schankin, Maniyar and Digre2014), by permission of Oxford University Press.

Beyond visual symptoms, other associated features can include tinnitus, anxiety, depression, tremors and, in some cases, gait imbalance. Although the syndrome often begins in the third decade of life, some individuals retrospectively report symptoms dating back to childhood. The condition may also manifest in adolescence and persist across decades without structural pathology (Sampatakakis Reference Sampatakakis, Lymperopoulos and Mavridis2022). Ophthalmological evaluations in VSS are typically unremarkable, despite patients frequently reporting significant visual disturbances. In one study, all patients had normal acuity and visual fields, yet photophobia and entoptic phenomena were consistently described (Yoo Reference Yoo, Yang and Choi2020).

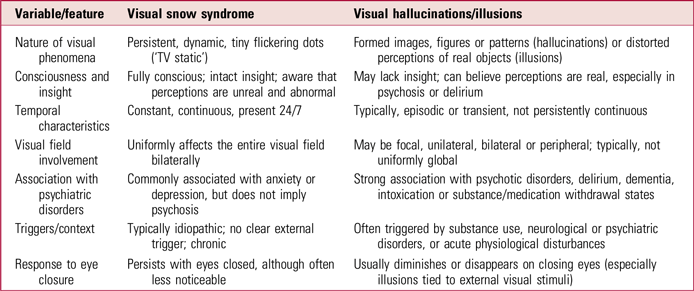

VSS may be associated with persistent migraine aura or hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD), but recent research (Barral Reference Barral, Martins Silva and García-Azorín2023; Chojdak-Łukasiewicz Reference Chojdak-Łukasiewicz and Dziadkowiak2024) supports its recognition as a distinct clinical entity in the most recent edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3; International Headache Society 2018). Diagnostic criteria for VSS are summarised in Box 1. The pathophysiology, diagnostic challenges and comorbidities of VSS are still being elucidated.

BOX 1 Diagnostic criteria for visual snow syndrome according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3)

Criterion A: Continuous visual snow (tiny, dynamic, flickering dots) affecting the entire visual field of both eyes, lasting for at least 3 months.

Criterion B: Presence of at least two of the following four additional visual symptoms:

-

palinopsia (afterimages or trailing)

-

enhanced entoptic phenomena (floaters, blue-field entoptic phenomenon, or self-light of the retina)

-

photophobia (sensitivity or intolerance to light)

-

nyctalopia (impaired night vision).

Criterion C: Symptoms are not consistent with typical migraine visual aura (which is typically episodic, unilateral and transient).

Criterion D: Symptoms are not better explained by another disorder (ophthalmological, neurological or psychiatric).

(After International Headache Society 2018: p. 192)

Pathophysiology

Although the exact pathophysiology of VSS remains unclear, current evidence suggests a distributed dysfunction across visual, attentional and sensory processing systems, rather than localised cortical or ophthalmological abnormalities (Sampatakakis Reference Sampatakakis, Lymperopoulos and Mavridis2022; Rusztyn Reference Rusztyn, Stańska and Torbus2023; Aeschlimann Reference Aeschlimann, Klein and Schankin2024). Neuroimaging studies have shown hypermetabolism and altered grey matter volume in the lingual gyrus and visual cortices, as well as reduced perfusion in occipital areas, suggesting disrupted visual processing (Schankin Reference Schankin, Maniyar and Digre2014; van Dongen Reference van Dongen, van der Marel and Karas2019; Rusztyn Reference Rusztyn, Stańska and Torbus2023). Electrophysiological findings, including increased gamma activity and reduced phase and amplitude coupling, support the presence of thalamocortical dysrhythmia and cortical hyperexcitability (Sampatakakis Reference Sampatakakis, Lymperopoulos and Mavridis2022; Aeschlimann Reference Aeschlimann, Klein and Schankin2024). Additional evidence from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies reveal impaired white matter connectivity within visual attention networks (Brooks Reference Brooks, Chan and Fielding2024). These abnormalities, alongside proposed disruptions in sensory gating and glutamatergic signalling, reinforce the model of VSS as a network-level perceptual disorder (Rusztyn Reference Rusztyn, Stańska and Torbus2023; Aeschlimann Reference Aeschlimann, Klein and Schankin2024).

Secondary visual snow

In contrast to VSS, which is considered a primary neurological disorder characterised by the absence of identifiable ophthalmological or structural abnormalities, secondary visual snow occurs comorbidly with or secondary to other conditions. In such cases, there may be abnormal neuro-ophthalmological findings or a clear temporal relationship with the underlying disorder, such as migraine, posterior vitreous detachment or hallucinogen persisting perception disorder.

There are four main categories of secondary visual snow symptoms: neurological disorders, ocular pathologies, drug-related visual snow and other systemic diseases. Red flags for secondary visual snow symptoms include new-onset or intermittent visual snow, unilateral or quadrant visual snow, and accompanied ocular or neurological deficits (Hang Reference Hang, Leishangthem and Yan2021). Hang et al (Reference Hang, Leishangthem and Yan2021) highlight the importance of distinguishing VSS from secondary visual snow to ensure accurate diagnosis and management, as delayed or incorrect diagnosis of these VSS mimics may lead to permanent vision loss or even death, in addition to the possibility of secondary forms responding to treatment of the underlying condition.

Sensory and psychiatric comorbidities

Although primarily a visual disorder, VSS is frequently accompanied by sensory and psychiatric comorbidities that have a significant impact on quality of life. From a sensory perspective, tinnitus is the most frequently reported non-visual symptom, affecting 30–60% of patients (Solly Reference Solly, Clough and Foletta2021; Renze Reference Renze2017; Lauschke Reference Lauschke, Plant and Fraser2016). Photophobia, phonophobia and heightened sensitivity to environmental stimuli are also common; tremors and gait imbalance are less frequent but noteworthy (Solly Reference Solly, Clough and Foletta2021; Ayesha Reference Ayesha, Riehle and Leishangthem2025). These symptoms likely reflect broader dysfunction in sensory integration networks, particularly within the salience and default mode systems, which may also explain clinical overlaps with conditions such as persistent perceptual postural dizziness and functional neurological disorder (Rusztyn Reference Rusztyn, Stańska and Torbus2023). Additionally, many patients report enduring traits of sensory sensitivity and emotional reactivity, suggesting a possible neurodevelopmental predisposition to altered sensory gating (Sampatakakis Reference Sampatakakis, Lymperopoulos and Mavridis2022).

Psychiatric comorbidities are also highly prevalent and clinically important. In a large study of 125 patients, anxiety (44.8%), depression (38.4%), depersonalisation (44.1%), sleep dysfunction (44.8%) and fatigue (49.6%) were frequently reported, with depersonalisation showing the strongest correlation with symptom burden, suggesting a shared neurobiological basis (Solly Reference Solly, Clough and Foletta2021). Despite this, psychiatric symptoms are often under-recognised, highlighting the need for routine screening and structured support, particularly for individuals experiencing emotion dysregulation or chronic depersonalisation (Ayesha Reference Ayesha, Riehle and Leishangthem2025). Treatment is further complicated by reports that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although commonly prescribed, may worsen visual symptoms in some people, necessitating individualised pharmacological strategies (Rusztyn Reference Rusztyn, Stańska and Torbus2023; Ayesha Reference Ayesha, Riehle and Leishangthem2025). Altogether, these findings support the view of VSS as a multisystem disorder, and not purely visual, requiring multidisciplinary management across neurology, psychiatry and neuro-ophthalmology.

Differential diagnosis

Visual snow syndrome presents a diagnostic challenge owing to its subjective symptoms and overlaps with neurological, ophthalmological and psychiatric conditions. Since diagnosis is clinical and based on exclusion, thorough history taking and appropriate investigations are essential. From a neurological perspective, the most common misdiagnosis is persistent migraine aura. Unlike VSS, migraine aura is episodic, typically unilateral and associated with transient, evolving visual disturbances like zigzag lines or scintillating scotomas. In contrast, VSS is continuous, bilateral and marked by fine, uniform visual static. These differences, particularly the persistence and lack of progression, are crucial for accurate diagnosis (Chojdak-Łukasiewicz Reference Chojdak-Łukasiewicz and Dziadkowiak2024).

Occipital lobe seizures or epilepsy can also mimic VSS with visual phenomena like flashes or static. However, these events are brief, paroxysmal and often associated with altered awareness or motor features. Electroencephalogram (EEG) or video-EEG monitoring helps distinguish seizure-related events from VSS (Sampatakakis Reference Sampatakakis, Lymperopoulos and Mavridis2022).

Ophthalmological conditions such as retinal disease, optic neuritis and vitreous floaters may be considered, but these are usually excluded by normal findings on visual acuity testing, optical coherence tomography and fundoscopy. The full-field nature of visual snow differs from localised floaters, and neuro-ophthalmological exams in VSS are typically unremarkable (Yoo Reference Yoo, Yang and Choi2020).

Among psychiatric conditions, hallucinogen persisting perception disorder is an important differential diagnosis. Although it shares features such as visual static, afterimages and entoptic phenomena, this disorder requires a clear history of hallucinogen use and often involves well-formed hallucinations and broader psychiatric symptoms. VSS, in contrast, typically arises spontaneously and demonstrates greater perceptual stability. Detailed history taking establishes prior substance use and the temporal relationship with symptoms. Importantly, visual hallucinations in VSS are consistent, non-verbal and non-formed, distinguishing them from psychotic or drug-induced experiences (Barral Reference Barral, Martins Silva and García-Azorín2023; Aeschlimann Reference Aeschlimann, Klein and Schankin2024).

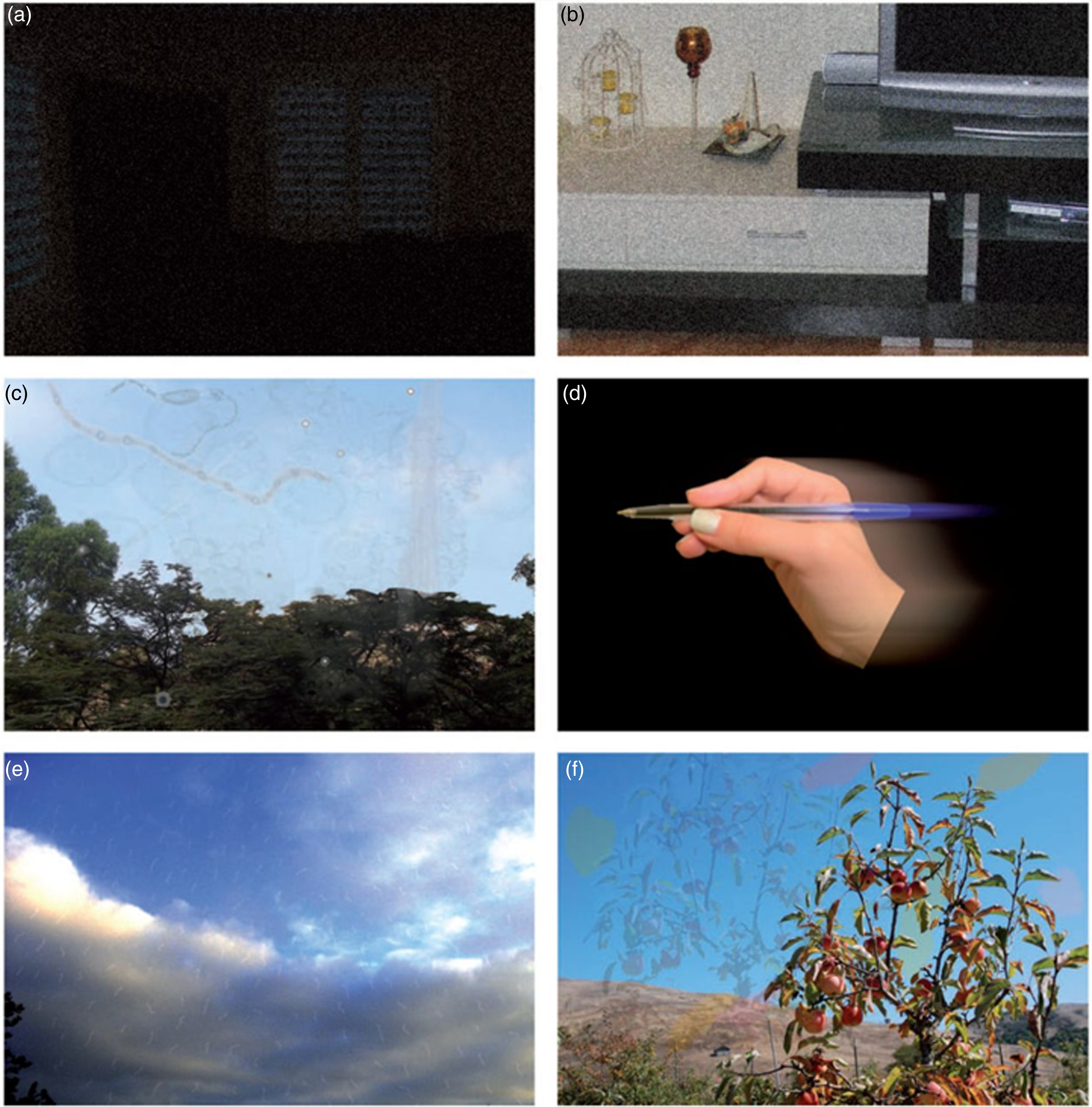

Other psychiatric differentials include psychosis, major depressive disorder with psychotic features, and delirium, which are marked by well-formed verbal hallucinations, delusions and impaired reality testing. Individuals with VSS maintain intact insight, and their visual phenomena are non-verbal, non-formed and consistent (Aeschlimann Reference Aeschlimann, Klein and Schankin2024) (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Features distinguishing visual snow syndrome from typical visual hallucinations

Sources: ffytche & Howard (Reference ffytche and Howard1999); Schankin et al (Reference Schankin, Maniyar and Digre2014); International Headache Society (2018).

Diagnostic investigations and clinical recommendations

Current recommendations advise clinicians managing patients who present with symptoms consistent with VSS to conduct a thorough clinical history and physical examination, carefully documenting the onset, duration, persistence and specific characteristics of the visual disturbances, along with related symptoms, such as photophobia, palinopsia and enhanced entoptic phenomena. MRI imaging of the brain is also recommended to exclude structural lesions or demyelinating conditions, especially if unusual clinical presentations or neurological findings are evident. Comprehensive ophthalmological assessment, involving visual acuity testing, visual field evaluations, dilated fundoscopic examination and optical coherence tomography, is essential to identify or exclude subtle retinal or optic nerve pathology. Additionally, a psychiatric evaluation should be conducted in cases where anxiety, depression, depersonalisation or other mental health symptoms significantly affect patient well-being or clinical management. Audiological assessment may also be beneficial if symptoms such as tinnitus or multisensory hypersensitivity are reported, given their frequent co-occurrence with VSS (Solly Reference Solly, Clough and Foletta2021).

Treatment and management

Given the distressing nature of VSS and its frequent misattribution to more serious neurological conditions, clear communication and education about the benign yet persistent nature of the disorder is essential. Validating the patient’s experience and offering reassurance that symptoms are neither progressive nor life-threatening can help alleviate anxiety and improve coping strategies. Collaborative, supportive care centred on realistic expectations has been shown to significantly improve long-term patient outcomes (Ayesha Reference Ayesha, Riehle and Leishangthem2025).

Currently, no standardised or universally effective treatment exists for VSS, and therapeutic strategies remain largely empirical. Management often requires a multidisciplinary approach, addressing visual symptoms and associated psychiatric or sensory disturbances.

Pharmacological interventions

Pharmacological treatments for VSS have shown limited and variable success (Rusztyn Reference Rusztyn, Stańska and Torbus2023; Aeschlimann Reference Aeschlimann, Klein and Schankin2024; Ayesha Reference Ayesha, Riehle and Leishangthem2025). Among the most tried agents, lamotrigine, a glutamate-modulating anticonvulsant, has demonstrated modest efficacy in reducing visual symptoms in a minority of patients, with 20–30% improvement in symptom severity, although some patients report worsening symptoms. Other medications, such as topiramate, acetazolamide and verapamil, have been used off-label, with anecdotal benefits, particularly in individuals with overlapping migraine features. SSRIs, including sertraline and citalopram, are often prescribed for comorbid anxiety or depression, but have been reported to exacerbate visual symptoms in some cases. The inconsistency of pharmacological responses in VSS has been highlighted, emphasising the need for more targeted clinical trials; consequently, a pragmatic, symptom-based pharmacological framework advocating for slow dose escalation and regular monitoring (because of variable tolerability) has been proposed.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Non-pharmacological interventions have demonstrated promising results in improving patient comfort and quality of life in VSS. Precision-tinted lenses can provide substantial relief, particularly those filtered for specific wavelengths: a measurable reduction in visual discomfort was demonstrated using visual noise quantification metrics, with up to 80% of patients reporting symptom improvement (Brooks Reference Brooks, Chan and Fielding2024). Although not curative, neuro-optometric rehabilitation therapy (NORT) may enhance functional visual processing and alleviate visual fatigue and distress. NORT is a specialised form of vision therapy designed to restore or improve visual function affected by neurological conditions; it involves customised visual exercises, prisms, lenses and eye–hand coordination training to enhance visual processing, eye movements and integration with balance and cognition (Suter Reference Suter and Harvey2011). Behavioural interventions such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) have shown benefits in improving attentional control and reducing anxiety, photophobia and depersonalisation, especially in individuals with high symptom burden (Ayesha Reference Ayesha, Riehle and Leishangthem2025). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) targeting visual and associative cortices has shown early promise in pilot studies and is currently being investigated for modulating cortical hyperexcitability in VSS (Rusztyn Reference Rusztyn, Stańska and Torbus2023). Additionally, vestibular and balance therapy may aid the minority of patients experiencing dizziness or gait imbalance (Sampatakakis Reference Sampatakakis, Lymperopoulos and Mavridis2022).

Exploding head syndrome

Case vignette

A 51-year-old woman presented with recurrent episodes characterised by hearing a sudden loud noise resembling an explosion, which she described as occurring when trying to fall asleep. These episodes caused her extreme distress and anxiety, significantly affecting sleep quality and psychological well-being. Her medical and psychiatric history were unremarkable, she had no current comorbid medical or psychiatric symptoms, nor was there evidence suggesting substance misuse or medication side-effects. The investigative workup included a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, routine laboratory testing, brain MRI and EEG, all of which were normal. The management approach included reassurance about the benign nature of the syndrome and recommending clomipramine.

Clinical presentation and diagnostic criteria of EHS

Exploding head syndrome (EHS), also known as episodic cranial sensory shock, is an auditory perceptual disorder characterised primarily by sudden, intense auditory phenomena that patients vividly describe as loud explosions, gunshots, metallic clangs or crashing sounds perceived to occur within or immediately around the head. These phenomena occur predominantly during transitions from wakefulness to sleep (hypnagogic) or from sleep to wakefulness (hypnopompic), and persist over varied time frames, typically seconds to minutes (Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015). Although auditory experiences are the hallmark of EHS, additional sensory phenomena commonly accompany episodes. These can include brief visual disturbances, notably bright flashes of light or lightning-like visual experiences, transient bodily sensations resembling electric shocks, or myoclonic jerks (sudden involuntary muscle contractions) often occurring concurrently with auditory episodes. These associated phenomena add complexity to the clinical picture, but they remain secondary to the primary auditory symptoms, which consistently dominate patient reports across clinical studies (Pearce Reference Pearce1989; Sachs Reference Sachs and Svanborg1991; Denis Reference Denis, Poerio and Derveeuw2019).

EHS is classified as an independent disorder in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders – Third Edition (ICSD-3; American Association of Sleep Medicine 2014). The diagnostic criteria for EHS are shown in Box 2.

BOX 2 Diagnostic criteria for exploding head syndrome according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders – Third Edition (ICSD-3)

Criterion A: Sudden loud noise or explosive sensation in the head occurring during the transition from wakefulness to sleep or from sleep to wakefulness.

Criterion B: The experience results in abrupt arousal, usually accompanied by a sense of fright, agitation, or anxiety.

Criterion C: Episodes are not associated with significant pain or physical symptoms (e.g., headache).

Criterion D: Symptoms are not better explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurological disorder, mental disorder, medication or substance use.

(American Association of Sleep Medicine 2014)

EHS episodes are benign and painless, but they frequently cause significant distress and fear owing to their abrupt, alarming nature, often leading patients to seek medical evaluation for serious neurological or psychiatric conditions, such as hypnic headaches or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Pearce Reference Pearce1989; Frese Reference Frese, Summ and Evers2014). Although EHS events typically last only seconds, their frequency and recurrence vary considerably among patients, ranging from isolated or infrequent occurrences to nightly or multiple nightly episodes, significantly impairing sleep quality and continuity. In the above case vignette, the frequent recurrent episodes markedly compromised the patient’s sleep patterns, intensified anxiety symptoms and profoundly reduced quality of life, and this aligns closely with literature reports documenting similarly variable but disruptive patterns (Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015; Fortune Reference Fortune and Richards2024).

Polysomnography (PSG) and EEG evaluations, although not mandatory for EHS diagnosis, play essential roles in clinical management, primarily through exclusion of differential diagnoses such as seizure disorders, other sleep-related parasomnias and neurological abnormalities. Moreover, distinguishing EHS from psychiatric or substance-induced hallucinations requires a detailed assessment of symptom consistency, duration, associated cognitive or psychiatric symptoms, and the temporal relationship to substance or medication use.

Pathophysiology

The precise pathophysiology of EHS remains uncertain, although current hypotheses suggest dysfunction across auditory, sleep–wake and sensory processing systems rather than isolated neurological deficits (Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015; Fortune Reference Fortune and Richards2024). Neurophysiological studies have proposed several potential mechanisms underlying EHS. One theory involves transient dysfunction or delayed inactivation of the brainstem reticular formation, which plays a key role in sensory gating during sleep–wake transitions; this disruption may result in the abrupt and heightened sensory experiences characteristic of EHS (Pearce Reference Pearce1989; Sachs Reference Sachs and Svanborg1991). Another hypothesis suggests that brief disturbances in calcium-channel activity, particularly within thalamocortical pathways, may lead to short bursts of cortical hyperexcitability and sensory distortions (Jacome Reference Jacome2001; Chakravarty Reference Chakravarty2008). Additionally, the symptom overlap between EHS and migraine aura has led some researchers to propose a role for cortical spreading depression (CSD), a wave of neuronal depolarisation commonly seen in migraine, as a potential contributing mechanism, although direct evidence remains limited (Evans Reference Evans2006; Kallweit Reference Kallweit, Khatami and Bassetti2008).

Recent EEG findings indicate transient alpha rhythm co-activation during sleep–wake transitions, suggesting cortical hyperexcitability or sensory gating deficits (Fotis Sakellariou Reference Fotis Sakellariou, Nesbitt and Higgins2020). Collectively, current evidence supports a systems-level dysfunction involving brainstem–thalamocortical pathways rather than isolated structural lesions.

Physical and psychiatric comorbidities

Exploding head syndrome frequently coexists with various neurological and sleep-related disorders, reflecting its complex clinical presentation. Neurologically, migraine and headache disorders demonstrate notable overlaps, with documented cases where EHS episodes occur in close temporal proximity to migraine exacerbations, suggesting potential shared underlying neurophysiological mechanisms (Evans Reference Evans2006; Kallweit Reference Kallweit, Khatami and Bassetti2008). Although epilepsy was initially considered as a differential diagnosis, clinical presentations and EEG evaluations typically distinguish epilepsy clearly from EHS; rare overlapping cases underscore the importance of careful neurological assessment (Gillis Reference Gillis and Ng2017).

Sleep disorders are significant physical comorbidities in people with EHS. Insomnia shows a markedly elevated prevalence compared with the general population, indicating disrupted sleep phases and persistent hyperarousal as possible contributing factors. Additionally, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) has been frequently observed, implicating intermittent hypoxic events or sleep fragmentation as potential triggers for EHS episodes (Nakayama Reference Nakayama, Nakano and Mihara2021; Ji Reference Ji2022). Parasomnias, including isolated sleep paralysis and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder, commonly co-occur, highlighting a shared vulnerability within sleep–wake transitional mechanisms (Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015).

From a psychiatric perspective, EHS is significantly associated with psychological distress. Anxiety is reported in approximately 44–50% of individuals, depression in around 35–40%, and panic attacks are also commonly documented, reflecting the intense emotional impact of EHS episodes (Denis Reference Denis, Poerio and Derveeuw2019; Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015). These psychiatric comorbidities not only exacerbate symptom severity but may also perpetuate a cycle of heightened sensory sensitivity and hyperarousal. Collectively, the physical and psychiatric comorbidities associated with EHS advocate for a comprehensive, multidisciplinary clinical approach, integrating neurology, sleep medicine and psychiatry to optimise patient outcomes through targeted evaluation and individualised management strategies.

Differential diagnosis

Diagnosing EHS requires careful consideration of several neurologically related conditions. Migraine aura can superficially resemble EHS, but it typically has a gradual onset over several minutes, involves visual or sensory disturbances, and often precedes a headache phase, unlike the brief, instantaneous auditory phenomena experienced in EHS (Evans Reference Evans2006; Kallweit Reference Kallweit, Khatami and Bassetti2008). Epileptic seizures constitute another key differential diagnosis. Seizures frequently present with impaired consciousness, stereotyped motor behaviours, postictal confusion and distinct EEG abnormalities; these features are characteristically absent in EHS, underscoring the importance of EEG and polysomnographic evaluations (Sachs Reference Sachs and Svanborg1991; Gillis Reference Gillis and Ng2017). Hypnic headache, another pertinent differential, typically manifests as a predictable nocturnal headache lasting 15 min or longer, accompanied by significant pain – distinctly contrasting with the brief, painless, auditory episodes characteristic of EHS (International Headache Society 2018). Lastly, transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) or minor strokes are considered because of their transient neurological disturbances; however, TIAs usually present with clear focal neurological deficits (e.g. weakness, speech impairment), which are notably absent in EHS presentations (Pearce Reference Pearce1989; Frese Reference Frese, Summ and Evers2014).

From a psychiatric standpoint, distinguishing EHS from conditions involving auditory hallucinations is essential. Psychiatric auditory hallucinations, typically associated with schizophrenia or severe affective disorders, generally persist over extended periods, are complex and verbal in nature, and occur predominantly during wakefulness, frequently accompanied by delusional content or significant psychiatric impairment. On the other hand, auditory experiences in EHS are brief, isolated, non-verbal and primarily occur at sleep–wake transitions, without additional psychiatric symptoms (Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015; Denis Reference Denis, Poerio and Derveeuw2019). Additionally, nightmares and sleep-related PTSD symptoms, which also present distressing sensory experiences, can mimic EHS. However, these nightmares are commonly longer, associated with vivid dream recall and emotional arousal, and occur predominantly during REM sleep, as opposed to the transient auditory events seen with EHS (Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015).

Diagnostic investigations and clinical recommendations

It is recommended that the evaluation of individuals presenting with EHS-like symptoms should include a detailed clinical history and examination that evaluates the frequency, duration and nature of episodes, including the patient’s descriptions of the auditory phenomena and associated symptoms. Additionally, EEG and polysomnography are useful in ruling out epilepsy or parasomnias, particularly if atypical features (such as limb movements, confusion or prolonged events) are present. Conducting MRI or computed tomography brain imaging could also help detect focal neurological deficits, new onsets in older age or atypical clinical presentations. Another necessary step is to perform a psychiatric evaluation if there is evidence of psychiatric conditions, complex hallucinations or significant anxiety and distress related to episodes. Finally, it is important to consider audiological testing if tinnitus or hyperacusis are also present, as such symptoms occasionally overlap with auditory phenomena of EHS (Aazh Reference Aazh, Stevens and Jacquemin2023).

Treatment and management

Currently, no universally effective or standardised treatment exists for EHS, making therapeutic strategies largely empirical and individualised. Management typically involves a multidisciplinary approach combining reassurance, behavioural modifications and pharmacological treatments, depending on symptom severity and patient distress. The management strategy implemented in the case vignette above aligns with current guidelines advocating comprehensive neurological assessment, reassurance, patient education and targeted symptomatic relief.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Given the benign yet distressing nature of EHS, non-pharmacological interventions form an essential cornerstone of management. Reassurance and psychoeducation serve as first-line approaches, effectively mitigating patient anxiety and reducing the frequency of episodes by clearly communicating the harmless and non-progressive nature of the disorder (Frese Reference Frese, Summ and Evers2014; Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015). Behavioural sleep interventions – such as optimising sleep hygiene, minimising caffeine consumption and maintaining structured sleep–wake routines – should be routinely advised. Cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) and relaxation techniques are valuable supplementary interventions aimed at decreasing hyperarousal and anticipatory anxiety associated with EHS episodes (Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015). Mindfulness-based strategies may further enhance emotional resilience and support coping mechanisms in managing anxiety linked to the condition.

Pharmacological interventions

Although no medications are specifically approved for EHS, several pharmacological treatments demonstrate variable efficacy, primarily based on case reports or small-scale studies. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), particularly amitriptyline and clomipramine, are among the most frequently prescribed, owing to their effects on serotonergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission, which may stabilise sleep–wake transitions (Sachs Reference Sachs and Svanborg1991; Pirzada Reference Pirzada, Almeneessier and Bahammam2020). Clinicians should initiate these medications cautiously because of their potential anticholinergic side-effects, sedation and weight gain.

Calcium channel blockers such as flunarizine, traditionally used in migraine prophylaxis, have also shown anecdotal effectiveness, possibly by modulating calcium channels involved in transient neuronal hyperexcitability (Chakravarty Reference Chakravarty2008). Selective serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as duloxetine have been used to relieve severe anxiety and depression in EHS (Wang Reference Wang, Zhang and Yuan2019).

Benzodiazepines, notably clonazepam, may provide acute symptomatic relief, owing to their GABAergic activity, although their routine use should be approached with caution, considering potential sedation, cognitive impairment and dependency risks. Their role is primarily reserved for short-term symptomatic relief or severe cases refractory to other interventions (Salih Reference Salih, Klingebiel and Zschenderlein2008; Kaneko Reference Kaneko, Kawae and Saitoh2021).

Non-invasive neurostimulation

Emerging treatments such as single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (sTMS) have shown promise. Early research suggests that sTMS may reduce cortical hyperexcitability, a proposed mechanism in EHS, and could be considered in future treatment plans for individuals with refractory symptoms (Puledda Reference Puledda, Moreno-Ajona and Goadsby2021).

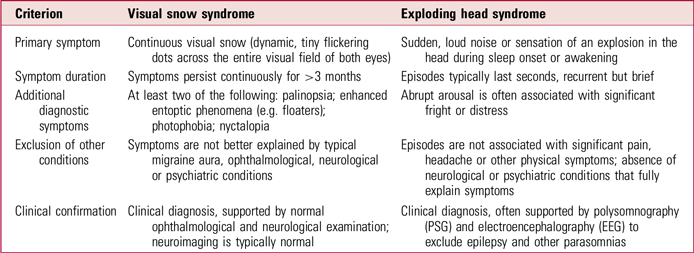

Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges

Both EHS and VSS are rare and relatively understudied disorders characterised by continuous or recurrent benign disturbances of sensory perception– auditory in EHS and visual in VSS. Although distinct in symptomatology (Table 2), the conditions share common diagnostic and therapeutic challenges that highlight broader limitations in clinical recognition, standardised evaluation and effective management strategies.

TABLE 2 Clinical differences between visual snow syndrome and exploding head syndrome

Diagnosis

Despite their distinctive features, both syndromes pose diagnostic complexities, primarily due to the subjectivity of their symptomatology, reliance on patient self-report and absence of specific biomarkers. As a result, both conditions remain largely diagnoses of exclusion, necessitating thorough clinical evaluation to rule out alternative neurological, psychiatric and ophthalmological causes (Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015; Fortune Reference Fortune and Richards2024).

A central clinical challenge shared by EHS and VSS is the frequent misattribution or dismissal of the patient’s experiences, particularly given the absence of objective findings on routine clinical investigations. Increasing awareness of these conditions and their characteristic presentations among primary care clinicians, neurologists, sleep medicine specialists, ophthalmologists and psychiatrists is crucial for minimising diagnostic delays and patient anxiety associated with unexplained symptoms (Denis Reference Denis, Poerio and Derveeuw2019; Solly Reference Solly, Clough and Foletta2021).

From a pathophysiological perspective, both syndromes appear rooted in broader network-level dysfunctions involving central nervous system hyperexcitability and impaired sensory processing. This shared neurobiological basis of disrupted cortical excitability and abnormal sensory gating mechanisms highlights potential avenues for exploring common therapeutic targets and broadens our understanding of sensory perceptual dysregulation (Fotis Sakellariou Reference Fotis Sakellariou, Nesbitt and Higgins2020).

Management

Both conditions also frequently coexist with psychiatric and sensory comorbidities that significantly affect patients’ quality of life. These overlapping psychiatric and sensory comorbidities highlight the necessity for integrated care models emphasising psychological support, symptom-specific interventions and holistic patient-centred approaches (Kirwan Reference Kirwan and Fortune2021; Solly Reference Solly, Clough and Foletta2021).

Effective management strategies for EHS and VSS remain limited, highlighting significant gaps in therapeutic understanding. Both disorders currently lack standardised, universally effective pharmacological treatments. Non-pharmacological interventions show greater promise and practicality in managing both disorders. Psychoeducation and patient reassurance are foundational in reducing anxiety and improving coping strategies, particularly given the benign yet distressing nature of the symptoms. CBT, mindfulness-based interventions, relaxation techniques and lifestyle modifications have shown initial effectiveness in reducing symptom severity and enhancing overall quality of life across both conditions (Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015; Solly Reference Solly, Clough and Foletta2021). These interventions emphasise the importance of patient-centred approaches addressing psychological distress and promoting adaptive coping mechanisms, areas that deserve further empirical validation through controlled trials.

Research gaps

Research limitations continue to impede a comprehensive understanding and effective management of both EHS and VSS. Current epidemiological data for both conditions suffer from methodological heterogeneity, sample biases and inconsistent diagnostic criteria, leading to wide variability in reported prevalence. Large-scale, standardised population studies utilising clear diagnostic frameworks, such as those provided by the ICSD-3 for EHS and the ICHD-3 for VSS, are critically needed to clarify epidemiological profiles and demographic patterns (Sharpless Reference Sharpless2015; Fortune Reference Fortune and Richards2024). Longitudinal cohort studies exploring the natural histories, remission rates and long-term psychological impacts of these conditions will further improve clinical understanding and guide patient counselling and prognosis.

Advanced neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies are promising research directions, particularly in concluding precise pathophysiological mechanisms. Functional MRI, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, magnetoencephalography (MEG), EEG and polysomnography could further clarify cortical and subcortical involvement, neurotransmitter imbalances and neurophysiological correlations underlying these sensory disturbances. Additionally, exploring genetic susceptibilities, molecular markers and familial aggregation patterns could identify specific risk factors and inform individualised treatment approaches, potentially transforming future therapeutic paradigms (Kallweit Reference Kallweit, Khatami and Bassetti2008; Puledda Reference Puledda, Moreno-Ajona and Goadsby2021).

Finally, the development of standardised, validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) tailored to each condition remains essential. Such measures can systematically capture symptom severity, quality of life impacts, psychological distress and treatment efficacy from patient perspectives, providing robust end-points for clinical trials and enhancing evidence-based clinical practice.

Conclusion

Visual snow syndrome and exploding head syndrome are distinct perceptual disorders characterised by persistent, benign sensory disturbances – visual in VSS and auditory in EHS – that significantly affect patients’ quality of life. Despite growing clinical recognition, both disorders continue to present considerable challenges in diagnosis, management and research owing to their subjective nature, lack of definitive biomarkers and frequent misunderstanding by clinicians. Addressing diagnostic challenges, therapeutic uncertainties and research gaps associated with VSS and EHS requires increased clinical awareness, standardised diagnostic approaches, multidisciplinary collaboration and patient-centred research initiatives. Ongoing advancements in scientific understanding will pave the way for improved diagnostic accuracy, targeted therapeutic interventions and, ultimately, enhanced quality of life for individuals experiencing these complex perceptual disorders.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Which of the following features is most characteristic of visual snow syndrome (VSS)?

-

a Episodic flashes of light localised to one visual hemifield

-

b Continuous, dynamic visual static affecting the entire visual field

-

c Vivid, formed visual hallucinations accompanied by delusions

-

d Sudden visual blackout during transitions between sleep and wakefulness

-

e Recurrent blurred vision associated with optic neuritis.

-

-

2 Which comorbidity is most commonly reported by people with exploding head syndrome (EHS)?

-

a Schizophrenia

-

b Seizure disorder

-

c Anxiety

-

d Parkinson’s disease

-

e Substance use disorder.

-

-

3 What is the primary diagnostic criterion that differentiates VSS from typical migraine aura?

-

a Occurrence during REM sleep

-

b Association with vivid dream recall

-

c Continuous bilateral symptoms lasting more than 3 months

-

d Onset during adolescence

-

e Presence of ocular abnormalities on examination.

-

-

4 Which of the following is the most appropriate initial management strategy for a patient with EHS?

-

a Immediate initiation of antipsychotic medication

-

b Referral for electroconvulsive therapy

-

c Reassurance and psychoeducation about the benign nature of the condition

-

d Emergency neuroimaging and lumbar puncture

-

e High-dose corticosteroids.

-

-

5 Which of the following neurobiological mechanisms underlies both VSS and EHS?

-

a Neurodegeneration of the basal ganglia

-

b Structural lesions of the occipital lobe

-

c Cortical hyperexcitability and thalamocortical dysrhythmia

-

d Reduced dopamine synthesis in the mesolimbic pathway

-

e GABAergic neuron loss in the cerebellum.

-

MCQ answers

-

1 b

-

2 c

-

3 c

-

4 c

-

5 c

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conception of the manuscript. D.A.A., A.K.J.A. and M.A. contributed to the review of literature and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. K.A.A. and D.A.E.-G. contributed to the preparation of material and the review of literature. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This article received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.