Introduction

Scholars and activists have been increasingly invoking the concept of poly- or meta-crisis (Heinberg & Miller, Reference Heinberg and Miller2023; Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Homer-Dixon, Janzwood, Rockstöm, Renn and Donges2024; cf. Tooze, Reference Tooze2022) to describe the many, interconnected and compounding environmental and social crises we find ourselves confronting in the 21st century. Indeed, each author on our research team has started to take seriously the ways societal norms are being reconfigured in a time of polycrisis and ensuing social and environmental unravelling – Campbell in the context of educational research; Hoeller in the context of land economics activism, and Benkaiouche in the context of urban studies and disaster studies. Together we co-run a not-for-profit arts/research organisation called the New Curriculum Group, working at the intersections of public education and community-engaged arts and research.

We collectively maintain that what many refer to through broad labels like climate change, global warming and even the Anthropocene, might actually be better described as an era of polycrisis, or cumulative crisesFootnote 1 : “a cluster of interdependent global risks [that] create a compounding effect, such that their overall impact exceeds the sum of their individual parts.”Footnote 2 The neologism polycrisis allows us to bring attention to the many-headed hydra of climate change, unhinged economic and industrial growth and their conjoined impacts on societal and ecological well-being. Many authors (Stein, Reference Stein2022; Rowson, Reference Rowson2021) have observed that what has been articulated as polycrisis is the reflection of an underlying ur-crisis or meta-crisis associated with the values, frames and assumptions of industrial modernity and the history of western imperialism and colonialism. While we subscribe to the notion of meta-crisis and would not want to obscure these underlying origins/links to western modernity, we also maintain that methodologically, a focus on polycrisis is practical, especially in education, providing a curricular orientation for understanding how multiple global crises interact and compound – often through focusing on constructs from complexity science such as conduits, attractors, vectors and triggers (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Homer-Dixon, Janzwood, Rockstöm, Renn and Donges2024). This orientation towards poly- over meta-, itself reflects an insight of complexity science (and indeed the polycrisis framework), is that causation in complex systems cannot be decidedly and holistically known or predicted (see Campbell & Hoeller, Reference Campbell, Hoeller and Jandrić2025). We would also caution that, without being paired with a related notion of polycrisis, the metacrisis may run the risk of flattening the complex causal entanglements of polycrises to abstract, and importantly, difficult-to-teach “isms,” ideas like colonialism, capitalism, imperialism, etc. For us, overshoot is a clear and measurable driver of the Great Acceleration (and by extension, the metacrisis) – offering a simple empirical approach for untangling complex forms of causation that educators can readily work with.

In this article we seek to articulate how the aims and purposes we commonly ascribe to education in general (and environmental education in particular) are being reconfigured in this time of run-away growth. We make the case that education must rise to meet the challenges of the polycrisis by fully confronting the interconnectedness and complexity of the challenges we face. For us, embracing such a transdisciplinary challenge will involve connecting fields and discourses that have historically remained disparate in education research – such as population ecology, stratification economics and disaster studies.

The purpose of this article is to articulate interconnected challenges confronting environmental education in this time of “polycrisis and unraveling” (Heinberg & Miller, Reference Heinberg and Miller2023). More specifically, we aim to:

-

1. redirect educational attention away from a reductive focus on what has been called carbon tunnel vision (Konietzko Reference Konietzko2022) – the idea that these various challenges associated with the poly/meta-crisis can be remedied by (simply) tackling the problem of carbon-emissions – towards the more foundational issue of ecological overshoot, and

-

2. contribute to less naïve conceptions of technology and technological progress, hopefully leading to a more refined critique of technocratic solutionism as the sole or chief solution to sustainability problems.

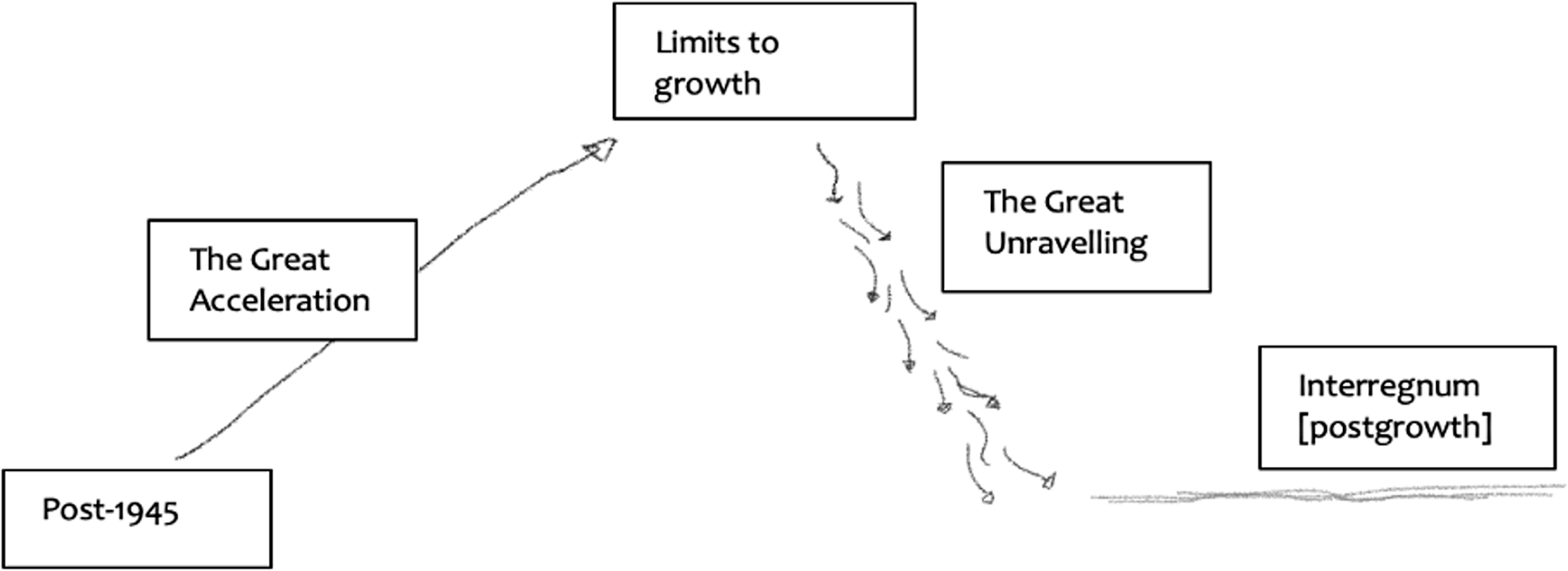

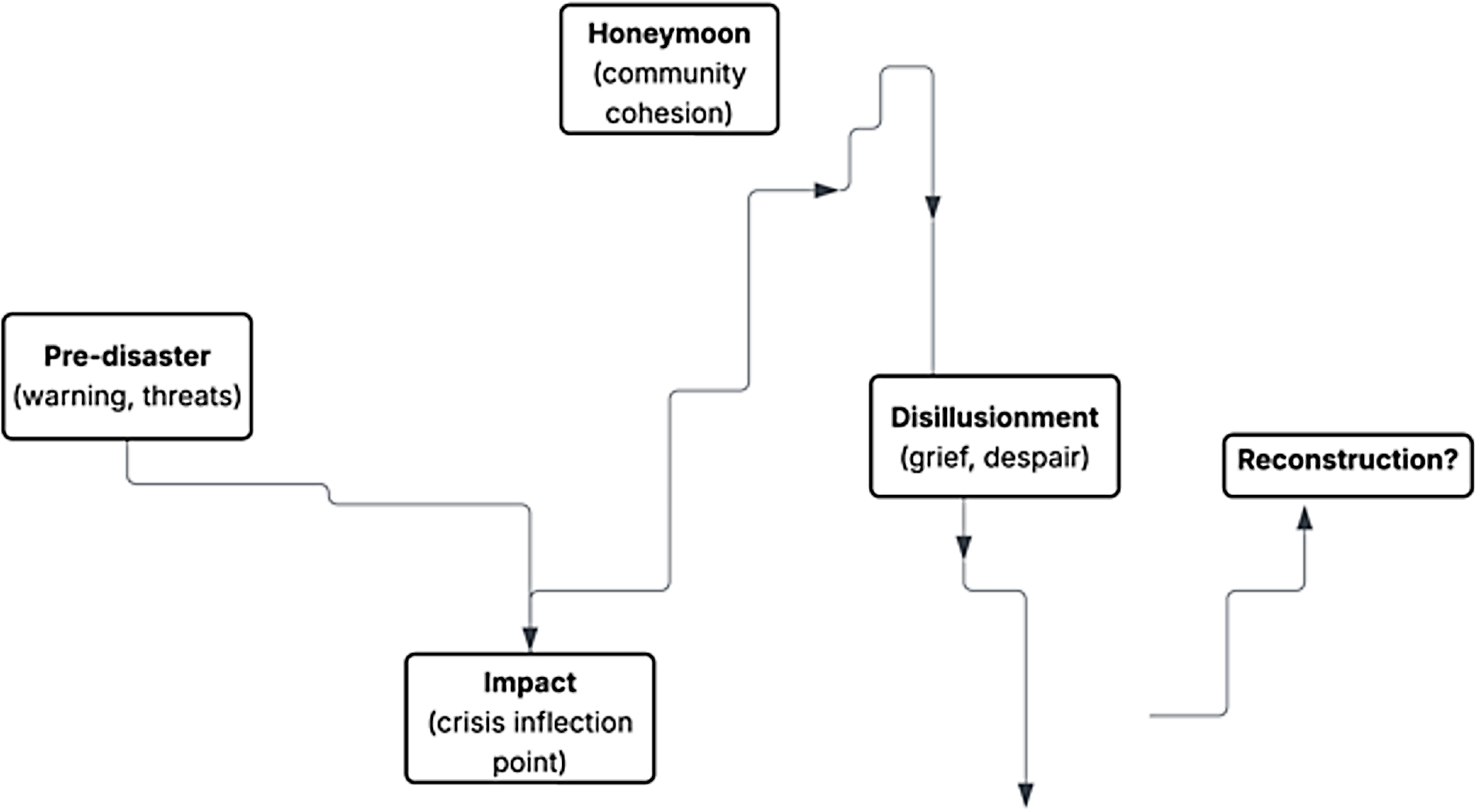

In Section 2, we synthesise research related to both the Anthropocene and post-growth discourses, presenting two simple heuristics (see Figures 1 and 2) that we have found useful in designing educational, community and research-led responses to the polycrisis. Afterwards in Section 3, we discuss these heuristics in relation to the post- and de-growth movement as well as long-standing practices of resource and wealth redistribution. In Section 4 we offer a set of criteria for distinguishing high-energy technologies (Tab. 2), and their associated modes of living, from low-energy technologies. We conclude (Section 5), by highlighting key openings for future research and education.

Figure 1. Representing the polycrisis, and the reduction of the problem to the singular issue of “carbon emissions” (Figure by Hoeller and Campbell); adapted from Konietzko, Reference Konietzko2022).

Figure 2. Our “limits to growth” heuristic. (By Cary Campbell).

Polycrisis and postgrowth: two heuristicsFootnote 3

Again, and crucially, the polycrisis encompasses much more than climate change, connecting issues as diverse as biodiversity and habitat loss, water and food scarcity, pollution and resource depletion, to growing economic and social precarity. As Figure 3 shows, an inability to acknowledge the multi-sided nature of the polycrisis results in what has been recently called “Carbon Tunnel Vision” (Konietzko, Reference Konietzko2022; Berman, Reference Berman2023) – the belief that these various challenges can be remedied by (only) tackling the problem of carbon-emissions.

Figure 3. The spiral of existential questioning (adapted from Campbell, Reference Campbell2023).

If there is a core driver underlying the polycrisis, we strongly assert that it can ultimately be attributed to the more foundational issue of ecological overshoot and land-enclosure – itself fuelled by the accelerated growth of modern techno-industrial society (MIT), i.e. metacrisis. For decades, population ecologists like William Rees (Rees, Reference Rees2000) have been providing evidence of ecological overshoot through applying methods like Ecological Footprint Analysis to measure carrying capacity in relation to land appropriation (Rees & Wackernagel, Reference Rees and Wackernagel2004, Reference Rees and Wackernagel2023). Rees (Reference Rees2023a) articulates the situation all-too-cogently in two points:

First, the human population substantially exceeds the long-term carrying capacity of Earth even at current average material standards. We are in overshoot, a state in which excess consumption and pollution are eroding the biophysical basis of our own existence. Second, national government and international community responses to even the most publicised symptom of overshoot, climate change, have been dismally limited and wholly ineffective. (p. 16 [emphasis added])

Taking this seriously – that we are in ecological overshoot – is a first, crucial step, necessitating that we locate educational theories and practices that can help us make sense of what this means for our lives, communities and the planet. What is significant about EFA is how it unambiguously shows the link between increasing consumption and population growth with appropriated land use. This connection to land use reveals that the crisis of ecological overshoot must be further connected to the ongoing history of colonial-imperialist land enclosure (Patnaik & Patnaik, Reference Patnaik and Patnaik2021) – which ultimately comes down to the private accumulation and capture of the socially and naturally created value that comes from the private enclosure of land (Obeng-Odoom, Reference Obeng-Odoom2020). For our purposes, the ongoing interdisciplinary conversation into the Anthropocene (see Angus, Reference Angus2016; Foster, Reference Foster2022; cf. Silova, Reference Silova2021) has brought attention to a series of concepts which, we argue, are significant in illuminating the dynamics of overshoot and exponential growth. In our work, we focus on three guiding concepts that have emerged from (or at least emerged in relation to) this ongoing discourse:

-

Polycrisis;

-

The Great Acceleration and

-

The Great Unravelling.

Acceleration and unravelling

Through our shared work navigating different aspects of the polycrisis, we have gradually fine-tuned a simple, historical roadmap (expressed in Figure 1). In short:

-

We are in what are (likely) the end-stages of a period of accelerated industrialisation and overshoot, which ramped up in the second half of the 20th century, labelled The Great Acceleration (see Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Broadgate, Deutsch, Gaffney and Ludwig2015a; Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Richardson, Rockström, Cornell, Fetzer, Bennett and Sörlin2015b, p. 743).

-

This Great Acceleration is showing signs of withdrawalFootnote 4 , as we breach key planetary thresholds (Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Richardson, Rockström, Cornell, Fetzer, Bennett and Sörlin2015b) which will result in forms of social and environmental unravelling, coined recently as The Great Unravelling (Heinberg & Miller, Reference Heinberg and Miller2023).

-

Such unravelling will eventually result in a postgrowth future – a world-order in which economic-industrial growth has ceased (Crownshaw et al. Reference Crownshaw, Morgan, Adams, Sers, Britto dos Santos, Damiano, Gilbert, Yahya Haage and Horen Greenford2019, p. 121) and likely because of an “involuntary and unplanned cessation of growth” (p. 117) brought on by necessity.

-

We can think of the early stages any postgrowth future as an interregnum, which Wolfgang Streeck (Reference Streeck2016) describes as “a prolonged period of social entropy, radical uncertainty and indeterminacy, in which society is essentially ungovernable and no new world order waits in the wings” (cf. Fitzi, Reference Fitzi2022).

Notably, working with this simple heuristic (Figure 1) allows us, to experientially situate ourselves somewhere in relation to the Earth’s current and recent trajectory while avoiding the Anthropocene’s often distracting scholarly debates about both its start-date or periodicity (Edgeworth et al., Reference Edgeworth, Ellis, Gibbard, Neal and Ellis2019) as well as its status as a geological epoch at all (see Lewis & Maslin, Reference Lewis and Maslin2015; Foster, Reference Foster2022; cf. Rull, Reference Rull2018). Instead, The Great Acceleration and its associated effects (unravelling, social and environmental) is the main historical demarcation Figure 1 brings awareness to – something which can be used to position ourselves, that, though multi-generational in scale, is experientially and historically relatable (see Moura & Guerra, Reference Moura, Guerra, Wallace, Bazzul, Higgins and Tolbert2022; Chakrabarty, Reference Chakrabarty2018) – ultimately, the scale of many student’s parents or grandparents’ life. Still, this simple heuristic is ultimately linear – linearity itself, one of the core, narrative and discursive traps of growth-based thinking. To this point we stress the ambiguous space of possibilities that the postgrowth-interregnum stage ushers in. Here, suspended in the liminality of Interregnum is a place for imagining new kinds of postgrowth stories and practices that could conceivably push up against this oppressive linearity of growth-centred, progress narratives.

Our article represents an attempt to consider how we might mobilise educational efforts in response to widespread ideological paralysis in the face of polycrisis. However, as we will return to in our conclusion, navigating such a difficult reality requires continued and sustained questioning that, as Latour (Reference Latour2017) says in his late essay, can hopefully reveal to us important Terrestrial attractors – values and practices that could conceivably bring us down to earth – but that also don’t succumb to anxiety, cognitive exhaustion, hopelessness and paralysis in the face of ecological issues while fully acknowledging the educational importance of such feelings (see Campbell, Reference Campbell2023). Enter our second guiding heuristic:

What’s happening? Why me? What now?

Cary Campbell (Reference Campbell2023) located and described a kind of dialogical-unfurling that conversations about climate-change often move through, in terms of three existential-pedagogical-curricular questions:

-

What’s Happening?

-

Why Me? and, lastly;

-

What Now?

These questions are conceptualised as a kind of recursive, both existential and curricular unfolding – through which researchers, teachers, students, both collectively and individually, grow their awareness of the molycrisis, possibly through focusing on one or more intersecting polycrises. One way of expressing this dialogic unfolding is in the form of a spiral (see Figure 2), in which each question resurfaces as students and teachers encounter and foster greater and more nuanced understandings of these interconnected issues.

More recently – and directly inspired by Dillon’s integration of Campbell’s framework with Biesta’s work – we have started to employ Campbell’s three-part framework in conjunction with Biesta’s (Reference Biesta2021a) similarly tripartite conceptualisation of education-towards-subjectification moving through phases of: Interruption, Suspension and Sustenance. Bringing attention to “what’s happening,” always involves a kind of interruption of routine everyday experience, often felt through the feeling of resistance, such as for instance through encountering strong and distressing emotions in the face of ecological loss.

Furthermore, to illuminate and make sense of what’s happening – and specifically to understand our own implication and involvement within “what’s happening” – educators evoke practices of suspension. According to Dillon (Reference Dillon2024) and Biesta (Reference Biesta2017), enacting suspension largely involves a confrontation with limits (which necessarily involves a confrontation with our personal, existential limits) and this is the implicit connection to Why Me?. Such acknowledgements of “what’s happening?,” when meaningfully engaged, often move people to a place of fret, worry, despair, fear – when they start to understand and grapple with what all this means for their own life choices, desires. This personalising aspect of “Why Me?” is difficult but it can also not be ignored, glossed over or sped past. Addressing “Why Me?” exposes and makes us vulnerable to the world – but it is also entirely necessary to move us beyond the ego towards the eco (see Biesta, Reference Biesta2021b; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Chang and Scott2020). Eco-pedagogues have consistently associated phases of suspension with arts-educational practices (see Vasko, Reference Vasko2016, Reference Vasko2024). This is because the arts are more than vehicles of self-expression (Biesta, Reference Biesta2017) – they help bring us into dialogue with the world by connecting us with the limits of our bodies, our senses, and the worldly materials of our art-making (sound, stone, paint, wood, metal, etc.,). Finally, teachers must come to cultivate practices of sustenance, which as Dillon (Reference Dillon2024) notes, manifests as “support and nourishment” by which this difficult work of “dialoguing through” is made “possible, bearable” (Biesta, Reference Biesta2019, p. 16). This What Now? work involves reconciling our beliefs, experiences and desires with the world as we now understand them. Through such practices of slowing down (suspension) we encounter the limits of our desires.Footnote 5 The cycle begins anew.

We embrace working with heuristics as a powerful methodology for teacher inquiry and self-study. Beyond making prescriptions around best practices, working with heuristics in open-ended and creative ways can allow teacher-researchers to embrace the “multidimensional, multiperspectival […] ‘story of the lived experience of teaching” (Fogelgarn, Reference Fogelgarn2019). The flexible nature of heuristic inquiry allows teachers to focus on the nuanced and contextual aspects of their own teaching practice, while remaining open to the unknown.

Vannessa Andreotti (Reference Andreotti2024) have recently articulated how, in the face of the systemic denials of modernity, educators must come away with models of pedagogy based, not on the individual “mastery of knowledge and skill” towards embracing the complexities of what she calls depth education, based on the “non-coercive rearrangement of desires.” Mastery is about acquiring knowledge that makes you strong and unshakable in your beliefs. Indeed, mastery feeds directly into the frames, values and orientations of industrial modernity – based on ideas of possessive individualism and extractivist logics that that we are masters of the earth. Depth education can be thought of through the frame of the “widening the circle of relations” (Ling and Campbell, in Campbell, in press/Reference Ling, Campbell and Campbell2026), an organic sense of pedagogy that proceeds iteratively and gradually towards deepening our awareness and attention of our embeddedness within eco-social complexity; not unlike heuristic inquiry itself.

Mass subjectification in a time of disaster: The story of Okawa elementary school

We propose that – precisely because of the mass experience created by increasing climate emergencies – disaster-response pedagogy and education (Kitagawa, Reference Kitagawa2021; cf. Irwin, Reference Irwin2024b) becomes of renewed significance as a field, allowing us to pose critical questions and actions that reframe notions of subjecthood, emancipation, agency, as well as societal and community cohesion in the face of the “limits and limitations” (Biesta, Reference Biesta2021a, p. 3) imposed on us through this time of (poly)crisis. Connected to Figure 2, acknowledging our shared experience of climate disasters presents important existential and pedagogical openings to explore shades of what’s happening, together. Such confrontations are essential, as the experience of shared experiences of climate disaster and ensuing social/political failures precisely points to the emergence and significance of mass subjectification events – the dynamics of which have, arguably, not been grappled with in education or curriculum research (cf. Campbell, Reference Campbell2024, Reference Campbell, Olteanu, Pesce and Pikkarainen2025; cf. Benkaiouche and Campbell, in Campbell, in press/Reference Benkaiouche, Campbell and Campbell2026).

Biesta (Reference Biesta2009) notes that subjectification is a process “that allows those being educated to become more autonomous and independent in their thinking and acting” (p. 41). From a disaster context, the tragic case of Okawa Elementary School in Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan, highlights the complex dynamics involved with mass subjectification events (events that, existentially and often dramatically, call huge groups of people to risk themselves (see Biesta, Reference Biesta2020), to make their own choices – to act or not act.

Fifty-one minutes after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE) hit, a tsunami made its way up the Kitakami River and killed 74 out of the 78 pupils and 10 of the 11 teachers still at the school (Sakurai & Ito, Reference Sakurai, Ito, Ito, Tamura, Kotera and Ishikawa-Ishiwata2022, p 92). When the earthquake first struck, teachers and administrators initially argued over whether to evacuate to higher ground by climbing up the snowy mountain behind the schoolgrounds. Two boys began running towards the mountain, but “the boys were ordered to come back and shut up, and they returned obediently to their class” (Parry, Reference Lloyd Parry2017). Soon after, the tsunami washed most of the class away.

Years later, the Sendai High Court ruled that the school was guilty of negligence, primarily due to the lack of a designated third tsunami evacuation area, and clear evacuation routes in its risk management manual (Sakurai et al., Reference Sakurai, Ito, Ito, Tamura, Kotera and Ishikawa-Ishiwata2022, p 92). However, the problem is not only that a third evacuation area (up the hill behind the school) had not been formally designated in advance: the real negligence was the institutional paralysis that inhibited students (and teachers) from responding improvisationally and intuitively, to the imminent disaster at hand, the tsunami, with the affordances and resources on hand.

The pre-impact reaction to the imminent tsunami could not be faulted: prior to the GEJE, residents of Ishinomaki were used to cleaning up after frequent earthquakes. This response quickly became business-as-usual – following, and as noted by local government bureaucrats, many residents stood calmly in the street chatting and tidying despite the evacuation warnings from the loudspeaker car. What occurred after the tragedy was a bifurcated response, highlighting, how community responses to disasters necessarily mirror internal psychological responses (see Figure 4): a steadfast desire to move forward to “reconstruct” on the part of government officials, and a profound sense of loss and disillusionment among the parents of the dead children, and those children who survived.

Figure 4. Community responses to disaster. (By Marion Benkaiouche and Cary Campbell, inspired by Zunin and Meyers, as cited in DeWolfe and Nordboe, Reference DeWolfe and Nordboe2000).

This tragedy highlights the importance of education, and schools in particular, in a time of increasing disasters and undergirds the importance of reconsidering subjectification as an often-neglected domain of educational purpose, especially against the more ubiquitous aspects of education for socialisation, as well as the importance of cultivating what could be called improvisational agency in disaster pedagogy. As Keiko Ishikawa (Reference Ishikawa2023) reflected,

At the time, my children were 9 and 13 years old. I told them about this tragedy and told them, “If you think that the people around you or the adults are wrong, trust your own intuition and judgment and take action to protect your life.” This became the educational principle for our home.

Retheorising subjectification in times of climate disaster presents a strong challenge to formal education, especially in the context of formal schooling – pushing us to consider what education is for beyond the more conventional domains of qualification and socialisation.Footnote 6 Fettes and Blenkinsop (Reference Fettes and Blenkinsop2023) strongly express the concern that schools often “institutionalize a kind of cultural stupidification that stems from our progressive estrangement with wild nature” (p. 2). In the face of the uncertainties of disaster events and crises, the limits of business-as-usual and other normalising forms of socialisation may become increasingly apparent, as they did in Ishinomaki City. Still, it is imperative that we resist instrumentalizing or imposing ideal visions of the moral self onto our students or research participants (see Thompson, Reference Thompson2024) – that we allow for, as yet, unarticulated forms and dynamics of subjectification to emerge in unprecedented times (Campbell, Reference Campbell2024).

Returning to the synthesis of Campbell and Biesta’s heuristics: this proposal to take subjectification seriously opens up a space of suspension following the initial interruption that disaster events force upon (What’s Happening?), moving us quite inevitably to feel our complex feelings of disillusionment (Why Me?/Why Us?), hopefully ushering a third stage, where new beginnings, practices and ways of life can come into existence (sustenance).

Again here, our task as educators and researchers is not principally to impose methods but rather to bring attention to important aspects of our shared experiences – encapsulated by the iterative and spiralling movement of What’s happening – Why me – What now? – and working to support this dialogical movement through practices that Interrupt – Suspend – and offer sustenance. We can implicitly see how this framing informs pedagogical orientations: dialogic modes of pedagogy that connect to individual and shared experiences of climate-disaster offer an important Interruption, as an integral part of What’s Happening? is a pedagogy that centres shared emotions beyond facts and what has been called info-dump pedagogy (Campbell, Reference Campbell2023). This follows from the Method of Currere (Pinar, Reference Pinar1975), that curriculum is itself lived experience that remembers the past (regressive) with an eye to the future (progressive), while staying focused on the present (Pinar, Reference Pinar2022). Such dialogic practices (talking with each other about climate-change) indeed slows us down (Suspension). In such suspended moments, a move inward to “Why me?” is inevitable and necessary as students turn to consider what this means for their lives. However, Why Me? the focus on self and interiority should always open back up to Why Us? which is arguably the beginning of the next phase, the start of asking What now? Once we have attended to the previous phases, we find ourselves existentially and socially more capable of addressing the complexities of imagining futures beyond growth. This again shows the importance of cultivating disaster-response pedagogy – in times of disaster, considerations that may have previously been seen as taboo in mainstream discourse become essential and unavoidable conversations. We firmly believe that the disruption caused by disaster events offer essential educational opportunities to question the status-quo and to articulate new societal-community responses – new futures, beyond the purviews of unlimited economic growth, beyond the meta-crisis! Just as Suspension/Why Me? Has been practically married with arts-education practices, so too, can Sustenance/What Now? be married to imaginative education frameworks and practices (Judson, Reference Judson2024). Here, it is integral for educators to draw from diverse cognitive tools to tell new stories of the future (see Ch. 8 in Campbell, in press/Reference Campbell2026).

In the next section, we review the diverse world of postgrowth discourse, discussing critical openings for pedagogy and curriculum, before going on to highlight how postgrowth questions can be illuminated by long-standing resource redistribution practices rooted in local, Ecological Knowledge (EK).

Post/de-growth

The post/de-growth movement is diverse in terms of activism, theory and empirical research. The movement is often connected back to the cornerstone 1972 report The limits of growth – arguably the first thorough economic-social–ecological modelling of the consequences of infinite economic and population growth in a world of finite resources, authored by Donnella and Denis Meadows and a total team of 17 contributing researchers (Meadows & Randers, Reference Meadows and Randers2012). More recently, researchers such as John O’Neill, Julia Steinberger and Jason Hickel (O’Neill et al., Reference O’Neill, Fanning, Lamb and Steinberger2018; Otero et al., Reference Otero, Farrell, Pueyo, Kallis, Kehoe, Haberl, Plutzar, Hobson, García‐Márquez, Rodríguez‐Labajos, Martin, Erb, Schindler, Nielsen, Skorin, Settele, Essl, Gómez‐Baggethun, Brotons and Peer2020; Hickel et al., Reference Hickel, Brockway, Kallis, Keyßer, Lenzen, Slameršak, Steinberger and Ürge-Vorsatz2021; Vogel et al., Reference Vogel, Guerin, O’Neill and Steinberger2024) have been modelling various ways we might achieve economic-social–ecological well-being within planetary boundaries. Other researchers like Mattioli and Roberts (Mattioli et al., Reference Mattioli, Roberts, Steinberger and Brown2020) have been studying the political economy of car-dependency and the ways in which western governments continue to advance policy that ensures and maintains such dependency (including the current, massive economic drive to produce and sell electric vehicles), despite the countless deleterious social and environmental effects, effectively locking us into an inter-generational cycle of petrol-mineral consumptive reliance.Footnote 7 Though diverse in philosophy and approach, these scholars are in large measure united in addressing the rather straightforward question: “Is it possible to decouple improvement in people’s quality of life…from increases in consumption?” (Porritt, Reference Porritt2003, p.4; see also Quilley, Reference Quilley2017; Rosa & Henning, Reference Rosa and Henning2018; cf. Saito, Reference Saito2024).

One important distinction we do make revolves around the subtle differences of meaning behind the terms degrowth and postgrowth. In short: while degrowth refers to a deliberate and intentional reduction in economic growth and overshoot (consumption, extraction and production), postgrowth discourse begins by acknowledging the realities of the Great Acceleration and run-away climate change – coming to the understanding that such changes will be “unlikely to originate from proactive government policy” (Crownshaw et al., Reference Crownshaw, Morgan, Adams, Sers, Britto dos Santos, Damiano, Gilbert, Yahya Haage and Horen Greenford2019, p. 121) and will instead be “predicated on an involuntary and unplanned cessation of growth” (p. 117) brought on by necessity. Quite frankly, we assert that an involuntary and unplanned cessation of growth is what a world of polycrisis confronts us with.

In the last decade or so, a growing movement of scholars have started to consider what post-de-growth means for educational thinking and doing in this historical moment.Footnote 8 White and Wolfe (Reference White and Wolfe2022) argue that, in this historical moment, education researchers now have a critical “response-ability to explore other material-theoretical possibilities and speculate that by thinking with different theories we can materialise other perspectives of reality … such as the theory that there are limits to growth […]” (p. 469): Indeed, we must seriously work to understand why educational thinking at large has failed to propose anything in place of continued growth and consumption? Why are we utterly unable to collectively muster a political-educational response to this rapid acceleration in consumption and extraction (Latour, Reference Latour2017, pp. 57–58)?” Ultimately, talking about postgrowth and overshoot remain extremely unpopular and even taboo topics in education as they directly challenge a deeply ingrained modernist nexus of normativity fixated on individual competition, societal progress and consumerism (Irwin, Reference Irwin2017, Reference Irwin2024a; Fettes & Blenkinsop, Reference Fettes and Blenkinsop2023; cf. Rees, Reference Rees2003).Footnote 9

Postgrowth imaginaries; potlatch and wealth redistribution

Imagining post-growth futures is difficult work and knowing exactly where to turn for solace or direction is unclear. Furthermore, and as mentioned, totalising and techno-rationalist understandings of the future function to diminish our capacity for agentive, adaptive and ethical response. The tension emerges in a question: how can we cultivate pedagogical and curricular practices that create openings for multiple post-growth-imaginaries, while being cautious not to advance a single or totalising-narrative of a post-growth future?

Ruth Irwin (Reference Irwin2017; cf. Reference Irwin2024a) is one educationist who has not turned away from this challenge, advocating that we explore the social-educational potential of worldviews and practices that could point us towards alternative values and notions of progress and technology beyond the horizons of endless growth – including, for instance, ancient alternative economic orders such as the Mesopotamian “sacred jubilee.”Footnote 10 Irwin (Reference Irwin2017):

Continuous exponential economic growth is catastrophic to the relationship of communities with their environment. […] [T]echniques such as the sacred jubilee, or debt forgiveness, could become a normal and fundamental element of the financial management of national, sustainable, steady state economics. (p. 68).

Adding to this list of alternative economic imaginaries with deep educational relevance, we would add the important Pacific Northwest ceremony of Potlatch – a particularly nuanced mode of public wealth and resource redistribution. Historian Keith Thor-Carlson (Ch. 10 in Cook et al., Reference Cook, Vallance, Lutz, Brazier and Foster2021) explains how resource-redistribution is/was integral to Potlatch, in his chapter “The last Potlatch”: Quite the contrary of impoverishing one community at the expense of another, Coast Salish potlatching actually enriched by ensuring that wealth resources that were more “available at one place than another, and more in one season than another, and often more in one year than another” became accessible to those whose tribal territories lacked specific resources (p. 317; cf. Bish, n.d.). This kind of commoning – making land, resources, families, property, names, songs in common – at the root of the potlatch are indeed an opening to understanding why these cultural practices were seen as so deeply subversive and threatening to the Colonial Matrix of Power behind the (new) province of British Columbia (see: Cook et al., Reference Cook, Vallance, Lutz, Brazier and Foster2021; cf. Campbell, Reference Campbell2022).

Considering these alternative practices of sharing and commoning – and through this, alternative practices of learning and teaching (see Davidson & Davidson, Reference Davidson and Davidson2018) – is an essential part of how education can work towards preparing us for a world beyond growth. Such practices represent significant openings towards considering and coordinating different kinds of postgrowth-futures through the Interregnum. In the final section, we will try to weave together these ideas around educating in a time of polycrisis. For us, these three theoretical paradigms come to the fore around the question of land and its relationship to technology.

High-energy versus low-energy technology

Current (globally adopted) systems of private property, industrialisation and taxation are colonial economic legacies (Patnaik & Patnaik, Reference Patnaik and Patnaik2016; Patnaik & Patnaik, Reference Patnaik and Patnaik2021) that continue to encourage land grabs and enclosures that catalyse further inequality, overshoot (Rees, Reference Rees2023) and elite overproduction (Turchin, Reference Turchin2023; Reference Turchin2024). In our work and organisation, we turn to land and stratification economicsFootnote 11 (Obeng-Odoom, Reference Obeng-Odoom2020, Reference Obeng-Odoom2021; Darity Jr., Reference Darity2022), as a focus on land illuminates a direct connection to both overshoot and the land-enclosure integral to ongoing processes of colonialism and capitalist expansion.

Technology – specifically, technology dependent on high-density, carbon-based energy – enabled massive population growth outcome. Obeng-Odoom (Reference Obeng-Odoom2021) explains how technological change is often correlated with increasing economic growth. The mechanisms behind this process are no doubt complex, but most directly they involve a “transformation in the nature of landed property,” away from common-property to property in the service of industrial production (pp. 115–116 cf. George, Reference George2009/1879). Obeng-Odoom’s (Reference Obeng-Odoom2020) analysis shows the limitations of mainstream development economics, demonstrating how institutions supporting individual property rights in land (cf. de Soto, Reference De Soto2007) have failed to accomplish the goal of equitable development in the global south and instead function as “a tool for transferring African [and global south] wealth to the rest of the world in ways that widen, rather than close, the many fissures of development and underdevelopment” (p. 117).

Our earlier discussions around Potlatch showcased a redistribution of wealth and power from elite households back to the community; while the debt-Jubilee – centred on redistributing land back to debtors who had lost their land (see Hudson, Reference Hudson2024) – acted similarly – both ultimately functioning to prevent elite over-accumulation and social stratification. Importantly, such social–political practices can be understood as complex ritual-processes scaffolded by symbolic systems – which likely emerged evolutionarily as a function to stabilise increasingly complex and abstract social relations (Deacon, Reference Deacon1997) and maintain reciprocal relationships under complex and dynamic environmental conditions. Primarily, this was accomplished through illuminating bio-regional limits and the basic fact that unbalanced ownership of land and resources leads to power imbalances that bring instability and crisis (Kemp, Reference Kemp2025).

The Reesian argument has been summarised by Smith (Reference Smith2024) in 7 pointsFootnote 12 . Referring to Smith’s (Reference Smith2024) third point, we observe that the energy power of fossil fuels has been historically controlled by western colonial nations. However, there are dynamics at play enabled by the relaxation of negative feedback from recent technological advancements in fossil fuel-use as well as bio-evolutionary processes to consider alongside these social-technological dynamics. We note that symbolic reference has played a critical role in enabling homo sapiens to encode information through ritual, storytelling and myths (Deacon, Reference Deacon1997). In ancient Mesopotamian societies, for instance, these were enacted through rituals that countered the oligarchic capture of land and resources (Hudson, Reference Hudson2024). There’s an important energy dynamic to grapple with here, as evidenced by recent work on Jevon’s Paradox (Polimeni et al., Reference Polimeni, Mayumi, Giampietro and Alcott2009) – an increase in technological efficiency has historically never led to a decrease in energy consumption in the contemporary history of human energy use (cf. Irwin Reference Irwin2024: Ch. 1). Now that the intensive power of fossil fuels has been fully released upon the globe, the dynamics of exponential growth are difficult to escape from (Berman, Reference Berman2023). This is precisely what is powerful methodologically about focusing on overshoot – it shows, bluntly, how modernity’s narratives of techno-industrial progress give us no escape plan (meta-crisis), and also, that this system has grown so large and complex in a state of global overshoot, that the dynamics of transforming such systems from within are themselves complexified (polycrisis).

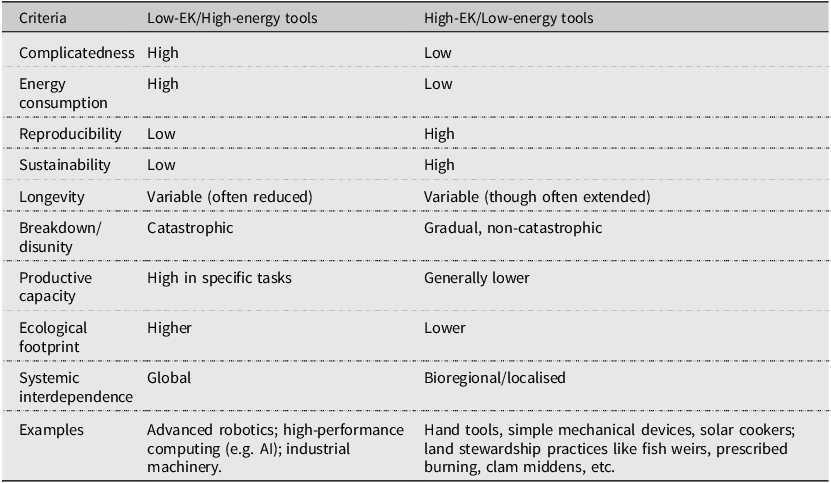

Currently no industrialised nation is fulfilling its social needs within ecological limits (O’Neill et al., Reference O’Neill, Fanning, Lamb and Steinberger2018), showing that high-energy technology is interwoven into the destructive cycle of land-enclosure and profit seeking. Responding educationally to this cycle would involve more fully articulating the technological values and orientations of petroleum-driven, growth-based society and how this connects to, as well as differs from, past societies. This is what is offered in Table 1 – a reframing of the high-energy tools that our growth-based societies have become reliant on as comparatively low in terms of their alignment and connectedness to Ecological Knowledge (EK) or Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) (See Turner & Mathews, Reference Turner, Mathews, Bai, Chang and Scott2021; Nelson & Shilling, Reference Nelson and Shilling2018). We should note our view is significantly informed by our conversations with William Rees (Rees et al., Reference Rees, Campbell and Hoeller2024) who prefers to invert the framing as “low-tech/high-energy tools,” building off general insights from complex systems research.

Table 1. Low-EK/High-energy tools versus High-EK/Low-energy tools. [by Thomas Hoeller and Cary Campbell]

Key points from Table 1: High-EK/Low-energy tools can be extremely effective for many tasks. Because of their low complexity they are easier to produce and reproduce across various places and bioregions, which makes them more sustainable due to lower energy consumption and production costs. These low-energy tools also often last longer due to their relative simplicity and ease of repair. In our figure, productive capacity is defined as the rate or potential which a tool/system can transform energy and the environment into useful work. In doing so we specifically avoid making claims about efficiencyFootnote 13 as it is difficult to quantify and measure across contexts and complex systems.

This reconceptualization of high-tech/low-tech challenges the perspective that advanced technology must always be equated with increasing productivity, growth and increased high-energy consumption. This also points to different iterations of fallibility in the context of complex systems: all systems deteriorate, break-down and eventually enter a state of disunity. High-EK/low-energy tools simply break-down less catastrophically and often more gradually compared to low-EK-high-energy tools.

Table 1 also shows from a macro perspective how technocracy is inherently connected to high-tech and high-energy modes of being. As such, we can make the claim that technocratic societies mostly only offer brute-force (what Rees calls low-tech/high-energy) technological solutions that, though highly productive, have higher risk of breaking down in catastrophic ways.Footnote 14 Importantly, we see living examples of high-EK/low-energy tools in the TEK practiced by many of the globes’ Indigenous peoples (Turner & Mathews, Reference Turner, Mathews, Bai, Chang and Scott2021; Nelson & Shilling, Reference Nelson and Shilling2018; cf. Irwin, Reference Irwin2024). In our own bioregion of the PNW, we encounter many complex and nuanced practices of land-management based on intergenerational systems of TEK such as clam gardens/middens, fish weirs and prescribed burning practices, to name a few – all of which could be important practices in revitalising postgrowth futures in our region.Footnote 15 No doubt, post-growth futures will have to effectively extend and merge TEK with Modern Ecological Knowledge (or MEK) in ways that harness the power and productive capacity of high-energy tech. Another important contribution of our diagram is in bringing nuance to conceptions and values of technology – to understand TEK, not as discordant or out of line with high-energy tech, but existing together on a continuum. For instance, many high-tech/high energy systems could potentially integrate great benefits to human ecology by helping us to more effectively organise around land and resources if brought into closer relationship with modes of EK. The point of our table is not to reject or dismiss such high-energy systems, but simply to highlight some of the inherent risks and trade offs of becoming overly reliant on them. Furthermore, Table 1 also shows how low-energy modes of being associated with EK can always be co-opted by high-energy tech. Obeng-Odoom (Reference Obeng-Odoom2021) goes on to discuss how such a vicious and perpetual cycle of technology-growth-enclosure can be broken through commoning-focused policies that explicitly prevent the transfer and concentration of land as a form of wealth exclusively within future generations of land-owners (land monopolisation) – commoning dynamics we encountered earlier with our conversation on Potlatch and other ancient modes of wealth distribution like the Mesopotamian debt jubilee.

“Down to earth” conclusions

As Latour notes in his late (Reference Latour2017) Down to Earth, we now need more than ever, “Terrestrial attractors” – perspectives and practices that proceed from the foundational understanding that the earth “is no longer the milieu or the background of human actions” (p. 41), but an essential and agentive participant. Scholars have called this ecological-disposition different things, but Latour (Reference Latour2017) describes it through the idea of being Earth-bound, what he calls being a Terrestrial: “Terrestrials in fact have the very delicate problem of discovering how many other beings they need to subsist. It is by making this list that they sketch out their dwelling places …” (p. 87). The question of sketching out dwelling spaces, we believe, is ultimately about how we can come to see ourselves as “down to earth” as rooted to a place, bioregion or piece of earth, not in a narrowly parochial or nationalistic way (Stables, Reference Stables2019), but rather in the sense of seeking out a place to care about, to be an inhabitant, to be in-habit with, and to dwell as a Terrestrial co-dependent on other Terrestrials. This drive to be autochthonous (Lilburn, Reference Lilburn2023) – to be an inhabitant of some place (not any place) is, importantly, not first and foremost an economic or consumptive choice. In our shared work through the New Curriculum Group, this has led us to engage seriously with the Curriculum for Bioregion movement (see MacGregor, Reference MacGregor2013), united behind the idea of designing educational resources and curricula that focuses on our embeddedness within a bioregion, or lifeplace (see Thayer, Reference Thayer2003).

Persson et al. (Reference Persson, Andrée and Caiman2022) ponders the extent to which environmental education can locate such terrestrial attractors, by offering opportunities: “for young people to spend time in a place, to connect with other species, and to prepare them, both intellectually and emotionally, for a life in the Anthropocene?” (cf. Gleason, Reference Gleason2019). By taking the question of what it means to be a Terrestrial seriously, educators may be able to prepare students for the realities of a world beyond growth, as White and Wolfe (Reference White and Wolfe2022) ask: “What might it mean to educate for this type of [postgrowth] society? How might this alternative vision of a sustainable future impact the design of educational policy and practice today?” (p. 469).

In this article, we have focused on framing the educational challenges underlying the polycrisis. We have advocated for the curricular interdependency (Pinar, Reference Pinar2022) of concepts such as overshoot – acceleration – unravelling. While we do not explicate specific pedagogical practices in this article, our hope is that educators can design practices that work through and across these interlinked concepts by iteratively moving through different stages of existential awareness by working with our heuristics Figures 1 and 2.

Ultimately the opening of this kind of pedagogy emerges in interruption – when our growth-addicted ways of being connected to the polycrisis, appear as contradictory or incoherent. We insist that a crucial opening can be found in disaster-response-pedagogy, in taking experiences of climatic disaster and unravelling seriously in the classroom.

We have tried to observe some of the main processes exacerbating the polycrisis, growth and overshoot, but have had to leave out many complex dynamics of this story. To sum up: as Table 1 showcases, high-energy technologies quickly become embedded within the fabric of growth-based society. However, and importantly, this occurs within a broader context of land enclosure and resource appropriation, itself connected to imperialism and colonialism. Some traditional societies historically had means to counteract the tendency towards elite-overproduction and resource concentration, including redistributive practices such as debt jubilees and Potlatch. The advent of fossil fuel energy, characterised by high energy density (low entropy), has effectively disrupted these long-standing land management and wealth distribution practices, leading to the enclosure of commons and their resources on a global scale and showcased by the phenomenon of global, ecological overshoot. Ultimately, education itself is thoroughly caught up and contributing to this dynamic of accelerating growth and elite over-production (see Turchin, Reference Turchin2023; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Campbell and Hoeller2024). In the face of the polycrisis, education (and the social sciences) has a strong obligation to articulate new values of technology and social–ecological progress beyond consumerism and its reliance on high-energy technology to sustain exponential growth (Table 1). This immensely difficult work, though fraught with complexities and uncertainties, will, we insist, involve locating and enacting life, research and educational practices that bring one down to earth to engage with particular places and bioregions, better understanding their systemic interdependence, and fulfilling social needs within biophysical limits. This will require educators to craft meaningful stories that truthfully speak to our current predicament confronted with the limits of growth and the realities of unravelling.

Acknowledgements

We are strongly indebted to our conversations with William Rees, who directly helped shape the thinking behind Table 1.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical standard

Nothing to note.

Author Biographies

Cary Campbell is a Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at Simon Fraser University and a co-director of New Curriculum Group. Cary works across the fields of educational philosophy, curriculum studies, biosemiotics and music education and is currently publishing a book of essays and interviews in the new year entitled “Education in a time of social and environmental unraveling: transdisciplinary responses to the polycrisis” (Routledge).

Thomas Hoeller is a co-director of New Curriculum Group and an independent scholar interested in biosemiotics, complexity, economics, and musicology.

Marion Benkaiouche is a founding member of New Curriculum Group and a Graduate Student at Simon Fraser University’s Urban Studies Programme, interested in the ways communities form, are maintained, and come apart, and explored through the themes of accelerationism, decay and circularity.