Introduction

Globalisation, de‐industrialisation and changing gender roles have challenged welfare states since the late 1970s. Nevertheless, there is little consensus on how we should understand the ‘new politics’ of the welfare state. During the ‘Golden Age’ of the welfare state in the postwar period, social democratic parties generally promoted welfare state expansion, while conservative and liberal parties fought against expansion – with Christian Democratic parties occupying a middle position. Following neoconservative efforts to retrench welfare states in the 1980s, however, we have experienced relatively large shifts in the coalitions that support or attack the welfare state. In general, centre‐right parties have abandoned all‐out broadsides against the welfare state. They now often support the welfare state, and even claim credit for welfare state programmes. At the same time, left governments have introduced welfare state cutbacks despite the widely held view that this would amount to electoral suicide. If we look more closely, we see that welfare state politics today are no longer simply about expanding or retrenching traditional income maintenance programmes such as pensions and unemployment insurance, but are also increasingly concerned with measures to address ‘new’ social risks, such as parental leave, daycare and active labour market policies (Taylor‐Gooby Reference Taylor‐Gooby2004; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Picot and Geering2013; Steinmo Reference Steinmo, Schäfer and Streeck2013; Gingrich & Häusermann Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015). Significantly, this cleavage between social investment and social consumption cuts across the traditional left‐right partisan divide.

In order to explain the new politics of the welfare state, we build on a growing literature on the political economy of advanced capitalist societies that analyses the shifting bases of support for welfare states in terms of large‐scale shifts in post‐industrial economies. As a number of scholars have argued, the transition to a service economy is linked to three main social structural trends: (1) a decline in the marginal utility of low‐skilled or semi‐skilled work, and a tendency of these workers to move into less‐protected, peripheral sectors; (2) a reduction in the numerical importance of core, high‐skilled industrial workers with high levels of protection; and (3) an increase in educated, disproportionately female service workers whose new social risks are not always adequately covered by traditional welfare state programmes (Estevez‐Abe et al. Reference Estevez‐Abe, Iversen, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Iversen Reference Iversen and Pierson2001; Palier & Thelen Reference Palier and Thelen2010; Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi2015; Iversen & Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2015; Oesch Reference Oesch2015). What is more, overlaying these socioeconomic developments, changing cultural attitudes have restructured the parameters of party competition. In addition to the traditionally prominent left‐right dimension, which is based on the conflict of state‐versus‐market, a second, post‐materialist libertarian‐authoritarian dimension of party competition has emerged (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Inglehart Reference Inglehart1997; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008). Taken together, these developments imply shifts in the electoral opportunity structures for parties. Cosmopolitan, middle‐class voters in the social service sector – predominantly female – have become a core electoral group for centre‐left parties, while culturally traditional working‐class voters increasingly support centre‐right parties. Given limited fiscal resources, however, these new opportunities are fraught with strategic trade‐offs for both left and centre‐right parties (Kitschelt & Rehm Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014, Reference Kitschelt, Rehm and Beramendi2015; Gingrich & Häusermann Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015).

While building on this important scholarship, our contribution is twofold. First, we examine the link between these electoral incentives and policy outcomes; and second, we place the intensity and directionality of electoral competition at the centre of the analysis. While the concept of ‘electoral competition’ is much invoked, it is rarely measured, nor has its empirical impact been tested directly in the field of welfare politics. We argue that electoral competition affects the electoral trade‐offs faced by political parties – trade‐offs that are specific to the policy area at hand. For migration or morality politics, for instance, the pattern might entail other groups and different trade‐offs. But when it comes to social policy, which is the case we focus on here, left parties must decide whether to focus on appealing to educated middle‐class voters by expanding social investment policies or whether to appeal to working‐class voters by defending status quo male breadwinner provisions. The same logic holds for the centre‐right. These parties must decide whether to practice restraint on pension cuts in order to appeal to culturally conservative working‐class voters or to promote the fiscal austerity appreciated by their pro‐business low‐tax constituencies. This is where electoral competition enters in. We define the degree of electoral competition as the probability that a vote shift will occur that changes a party's bargaining position in parliament (Abou‐Chadi & Orlowski Reference Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski2016). As this risk increases – that is, as electoral competition intensifies – parties should react by prioritising vote‐seeking strategies (Robertson Reference Robertson1976; Strøm Reference Strøm1990). Combining this moderating effect of competitiveness with parties’ ideological predispositions and their changing electoral constituencies leads to several predictions about different parties’ propensity to defend old social risk policies. At low levels of electoral competition, left parties should be prone to stick to their traditional defence of the welfare state status quo. At higher levels of electoral competition, however, left parties have increasing incentives to focus on vote‐seeking. This means appealing to educated, service sector, middle‐class voters and thus recalibrating welfare policies by privileging social investment at the expense of consumption. Similarly, if electoral competition is low, centre‐right parties will tend to follow their traditional policy profile, and thus be more likely to retrench welfare state measures in the interest of fiscal consolidation and economic growth. With higher levels of competition, however, centre‐right parties will prioritise their appeal to socially conservative working‐class voters, and will find engaging in welfare state cutbacks increasingly risky.

In addition to the intensity of electoral competition, we also consider the directionality of electoral competition. New entrants – in this case radical right parties – significantly change the trade‐offs between vote‐ and policy‐seeking. For left parties, the presence of a radical right competitor makes the vote‐seeking strategy of recalibration riskier as the risk that blue‐collar voters might defect to the right increases; thus, recalibration should be less attractive. For conservative parties, who already become less prone to recalibration as the intensity of competition increases, the entry of a radical right challenger should further strengthen this tendency. Thus, as electoral competition becomes more intense, both centre‐left and centre‐right parties will reach out to maximise their vote share. However, if a radical right competitor is available, the risk of compensatory electoral losses increases.

In our analysis, we focus on changes in pension rights generosity, pension generosity and social policy recalibration. Pensions are critical because public pensions are the core of the traditional welfare state and comprise the largest component of social policy expenditures. More importantly for our purposes, as we will elaborate below, it is precisely in the pension area that the interests of blue‐collar workers diverge from those of sociocultural professionals (Häusermann Reference Häusermann2010; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Schwander2015). By measuring changes in pension rights, we can tap into governments’ commitments to income maintenance for pensioners over the long term. Importantly, the pension rights indicator is designed to capture explicit changes in policy as well as policy drift directly as they occur. By measuring pension generosity, we measure current payments to individual pensioners. And by using a new social policy recalibration index, we compare the ratio of expenditures on social investment (day care and active labour market policy) to expenditures on social consumption (pensions). Using this combination of dependent variables, we perform a time‐series cross‐section analysis of ten OECD countries from 1980 until 2011, and find that electoral competitiveness indeed affects the behaviour of parties in government. For left governments, the likelihood of a reduction in pension rights generosity increases with the intensity of electoral competition, but only in the absence of a radical right party. For centre‐right governments, by contrast, increasing electoral competition decreases the probability of a reduction in pension rights generosity. Further, if a radical right competitor is available, this tendency is exacerbated. For left parties, we posit that pension recalibration is necessary to pay for new‐social‐risk policies, such as day care and active labour market policies. We show that with increasing levels of competition, left governments do indeed increase the share of spending on day care and labour market activation policies in comparison to public pension spending. For right‐of‐centre governments, we posit that pension retrenchment appeals to traditional centre‐right voters and should hence be a priority under low levels of electoral competition. And indeed, using a measure of pension generosity based on per capita pension expenditures, we find that lower levels of competition are associated with lower pension generosity.

Partisanship and the welfare state

Much theorising and empirical research on the politics of the welfare state has been inspired by two related sources: the ‘politics matters’ school, which responded to convergence theory by demonstrating the importance of political partisanship for social policy (Cutright Reference Cutright1965; Hibbs Reference Hibbs1977); and the ‘democratic class struggle approach’, which posited a clear linkage between class mobilisation, political parties and social policy outcomes (Castles Reference Castles1982; Korpi Reference Korpi1983). On this view, working‐class voters were mobilised by unions and left parties, whose combined economic and political clout allowed for class compromises that resulted in the establishment and expansion of the welfare state (Esping‐Andersen Reference Esping‐Andersen1990; Van Kersbergen Reference Kersbergen1995; Huber & Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001).

While some scholars defend the relevance of this ‘traditional’ view of partisanship for welfare state retrenchment (see, e.g., Korpi & Palme Reference Korpi and Palme2003; Allan & Scruggs Reference Allan and Scruggs2004), a growing body of contemporary research has increasingly come to question its assumptions. The ‘new politics’ of the welfare state literature argues that the existence of the welfare state itself creates multiple support groups, such that welfare state politics in the era of ‘permanent austerity’ have become an exercise in ‘blame avoidance’ and ‘path dependency’ (Pierson Reference Pierson1996). Empirical research on this topic, however, has delivered mixed results on whether parties actually get punished for welfare state reforms (Giger Reference Giger2011).

In contrast to the ‘new politics’ literature, the ‘new partisanship’ or ‘constrained partisanship’ literature continues to emphasise the role of political parties for welfare state developments, but argues that party behaviour can only be meaningfully analysed in the light of the structural changes of post‐industrial societies (Gingrich Reference Gingrich2011; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Picot and Geering2013; Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi2015). As a broader group has pointed out, post‐industrial economies display dualistic tendencies, with jobs for core industrial workers in decline, and jobs in peripheral sectors and in public services increasing, the proportions of which vary among liberal versus coordinated economies, and also depend upon the type of welfare state regime (Hall & Thelen Reference Hall and Thelen2009; Palier & Thelen Reference Palier and Thelen2010; Iversen & Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2015). Production workers as a percentage of the workforce have fallen by more than 20 per cent between 1990/1991 and 2007/2008 in Switzerland (from 24 to 19 per cent), the United Kingdom (from 25 to 16 per cent) and even in Germany (from 36 to 23 per cent), while sociocultural semi‐professionals and associate managers have increased their share by more than 20 per cent. More specifically, the share of sociocultural professionals increased from 11 to 14 per cent in Switzerland and Germany and from 9 to 13 per cent in the United Kingdom. The share of associate managers increased from 11 to 18 per cent in Switzerland and Denmark, from 13 to 18 per cent in Germany, and from 17 to 23 per cent in the United Kingdom (Oesch Reference Oesch2015: 122). In terms of votes, between 1980 and 2010, middle‐class voters as a percentage of employed left voters increased from just under 20 to more than 60 per cent in social democratic welfare state regimes, while working‐class voters decreased from just under 50 to just over 20 per cent. The figures vary somewhat across welfare state regimes, but even in southern welfare state regimes, where these shifts have been the least dramatic, middle‐class voters comprise a larger percentage of employed left voters than working‐class voters (Gingrich & Häusermann Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015: 59). Thus, the electoral relevance of working‐class voters has declined for social democratic and other parties (Best Reference Best2011).

These socioeconomic transformations play a crucial role for the strategic behaviour of political parties as they are leading to a changing demand‐side structure of political competition. For not only are the relative sizes of occupational groups changing, so are their social policy preferences. As Häusermann et al. (Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Schwander2015) demonstrate, high‐skilled individuals are increasingly exposed to labour market vulnerabilities, and these high‐skilled outsiders support activation and redistribution policies over classical social insurance policies, whose benefits rest on the stable employment more typical of labour market insiders (Rueda Reference Rueda2005; Martin & Thelen Reference Martin and Thelen2007; King & Rueda Reference King and Rueda2008; Lindvall & Rueda Reference Lindvall and Rueda2014; Gingrich & Ansell Reference Gingrich, Ansell and Beramendi2015; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Schwander2015). By shifting preference structures, these sociostructural changes of post‐industrial societies engender a new potential for novel support coalitions of the established political parties. As these groups have different social policy preferences, however, parties face both incentives to update their policy profiles and, at the same time, considerable trade‐offs owing to differences in the social policy preferences of labour market ‘insiders’ versus ‘outsiders’. For social democratic parties they reinforce a structural dilemma that has already been pointed out by Przeworksi and Sprague (Reference Przeworski and Sprague1986): in order to be electorally successful social democratic parties need to incentivise electoral alliances of working‐class and educated middle‐class voters. However, by focusing on policies favouring middle‐class voters, social democrats risk losing their capacity to attract working‐class voters. More generally, all parties face the challenge of bridging the preferences of their core voters with those that can be regarded as swing voters, who thus play a crucial role in party competition (Adams Reference Adams2001). Green (Reference Green2011) additionally argues that what political parties care about is issue consistency – that is, promoting issues that are in line with the priorities of their core supporters. Parties that attempt to attract novel groups within the electorate thus face the risk of neglecting the issues their supporters care about. Consequently, changing demand‐side structures of political competition create political trade‐offs between core supporter demands and potential vote‐maximising strategies.

Not only have shifting support coalitions of established parties transformed political competition in the post‐industrial age, but also the emergence and establishment of new parties challenge traditional patterns of party competition. The success of left‐libertarian, green and especially radical right parties has led to the politicisation of second dimension policies, such as immigration, European integration and morality politics (Hobolt & De Vries Reference Hobolt and Vries2015; Abou‐Chadi Reference Abou‐Chadi2016). Whereas earlier studies focused on macroeconomic and sociostructural transformations as the driver of second‐dimension politics (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008), the most recent research emphasises how issue competition changes the dynamics of party competition, particularly when new entrants are involved. Parties have strategic incentives to politicise specific issues and dimensions that they expect to benefit from in upcoming elections (Green & Hobolt Reference Green and Hobolt2008; Hobolt & De Vries Reference Hobolt and Vries2015). Issues that do not fit the traditional left‐right dimension, particularly lend themselves to these strategies as they can potentially drive wedges between support groups of established parties and coalitions (Van de Wardt et al. Reference de Wardt, Vries and Hobolt2014). A key consequence of the politicisation of the second dimension is that centre‐right and radical right parties can appeal more easily to the culturally conservative traditional working class. At the same time, with the rise of culturally liberal service professionals, left parties increasingly depend upon this group for support (Gingrich & Häusermann Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015: 58).

Electoral competition and welfare state politics

Given these shifts in social structure and party competition, we argue that both left and right parties face a fundamental trade‐off between their vote‐seeking and their policy‐seeking incentives – one that crucially depends upon the degree of electoral competition. When electoral competition is high, parties should follow their vote‐seeking incentives and pursue a strategy of vote maximisation by reaching out beyond their core constituency; in cases of low competitiveness, however, their policy‐seeking strategies should dominate and they will follow their traditional ideological profile and the preferences of their rank‐and‐file members.

Left parties have traditional ties to unionised workers in core economic sectors. However, as outlined before, the structural transformation of post‐industrial societies means that left parties need to appeal to educated middle‐class voters and high‐skilled outsiders in order to be electorally successful. Consequently, as a vote‐maximising strategy, left governments should prioritise social investment, such as better coverage of new social risks through day care and active labour market programmes over defence of traditional social consumption, such as the generosity of pension rights. Here we stress that such initiatives affect traditional working‐class male breadwinners quite differently than female sociocultural professionals. A high replacement rate based on 45 years of continuous employment is important to traditional core industrial workers. But service sector women and other high‐skilled labour market outsiders rarely achieve the earnings record necessary for the full standard benefit. Consequently, improvements in day care, and methods of re‐adjusting the accumulation of pension entitlements so as to credit family roles and forgive interruptions and career changes, should be more important to this constituency than all‐out defence of the standard pension. We thus argue that, under increased electoral pressure, when faced with demographic and fiscal pressures to rein in pension expenditures, governments will take the opportunity to recalibrate their systems, redirecting some resources from pensions to new social risks.

There are two reasons why appealing to these new groups should be electorally beneficial and does not simply result in a trade‐off between old and new voters. First, the fact that vote choice is not fully a function of parties’ policy positions but also dependent on party identification and political socialisation gives parties some leeway to strategically position themselves without necessarily alienating their core constituency (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005). Hence, incorporating new social risks and demonstrating a commitment to the demand of educated, female, middle‐class voters should not necessarily decrease working‐class support, particularly as some of this re‐direction may be achieved through attrition rather than actual cuts. Second, activists and core supporters themselves can be willing to accept the strategic movement of parties even if it deviates from their policy beliefs to a certain degree (Keman Reference Keman2011; Karreth et al. Reference Karreth, Polk and Allen2013). Hence, when electoral competition is high, we should expect left parties to be more likely to restructure systems of social security. Empirically, Abou‐Chadi and Wagner (Reference Abou‐Chadi and Wagner2018) find that more investment‐oriented policy strategies are generally electorally beneficial for social democratic parties. The first hypothesis thus states:

H1: With increasing levels of competitiveness left governments become more likely to recalibrate systems of social security.

The impact of increasing electoral competition on conservative governments, on the other hand, should be different. Their ideological profile and traditional voter base prescribe small‐state and fiscally conservative policies. Under conditions of low electoral competition these parties should therefore aim to reduce welfare state generosity. However, as electoral competition increases, conservative parties should reach out to traditional working‐class voters, their newer constituency. Consequently, they should avoid ‘neoliberal’ cuts on traditional social consumption. Furthermore, de‐polarising the welfare issue can be seen as a beneficial electoral strategy for right‐of‐centre parties as it will reduce class voting (Evans & Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2012), and thus allows them to compete with social democratic parties on their ‘home turf’ (Arndt Reference Arndt2014). Hence, we can formulate a second hypothesis:

H2: With increasing levels of competitiveness, right governments become less likely to recalibrate systems of social security.

One additional factor that should influence the relationship between electoral competition, partisan ideology and welfare state recalibration is the presence of a credible radical right challenger. Radical right parties have become established contenders for the working‐class vote in a large share of industrialised democracies. While there is an ongoing debate about whether the economic policy positions of radical right parties can be adequately described as neoliberal, more centrist or welfare chauvinist (Kitschelt & McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995; De Lange Reference Lange2007), radical right parties mostly appeal to the losers of globalisation through their authoritarian and anti‐immigrant positions (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008). They, thus, compete with centre‐left and centre‐right parties alike. If a radical right party can credibly compete for the working‐class vote, then losing those voters as a result of welfare state recalibration becomes much more risky for government parties. This means that the effect of the degree of electoral competition will depend on the existence of a credible radical right challenger. Several studies have indeed investigated how established parties react to the radical right and how this affects their electoral fortunes. Meguid (Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008) demonstrates how accommodative strategies of mainstream parties potentially reduce the electoral success of the radical right. Several other studies also show that mainstream parties indeed shift toward a more anti‐immigrant position when radical right parties are successful (Van Spanje Reference Spanje2010; Abou‐Chadi Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Wagner & Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2016). Our argument somewhat differs from these studies as we do not focus on the main issue that radical right parties compete over: immigration. We are more concerned with the question of how the social policies enacted by mainstream left and right parties will make the working class more available for the radical right as they might become frustrated with the dynamics of mainstream politics.

We expect to see that the increasing propensity of left parties to reduce the generosity of traditional welfare schemes with a higher level of competition is more pronounced when there is no radical right challenger. Similarly, centre‐right parties with increasing competitiveness will become even less likely to reduce welfare generosity in the presence of a radical right challenger. This is summarized in the following hypotheses:

H3a: The positive effect of competitiveness on left parties’ likelihood to recalibrate systems of social security will be stronger if there is no radical right challenger.

H3b: The negative effect of competitiveness on right parties’ likelihood to recalibrate systems of social security will be stronger if there is a radical right challenger.

Data, operationalisation and method

In order to test our hypotheses, we have compiled a novel dataset combining data on pension generosity with macroeconomic indicators, political institutions and a new measure of the degree of electoral competition. It includes country‐year information for ten OECD countries from 1980 until 2011.Footnote 1 We focus on pensions as they account for the lion's share of social spending and must be trimmed if resources are to be made available to cover new social risks and social investment. We use the pension rights generosity index from the Comparative Welfare Entitlements dataset as an indicator of governments’ commitment to traditional income maintenance (Scruggs et al. Reference Scruggs, Jahn and Kuitto2014; Scruggs Reference Scruggs2014). The PGEN indicator is comprised of the pension take‐up rate (proportion of persons over the standard retirement age that receive a pension) multiplied by the sum of four standardised items and a constant. The four components comprise: the standard pension replacement rate (the pension benefit as a percentage of the average production wage for a worker that earned 100 per cent of the average production wage for the full qualification period); the ‘social pension’ replacement rate (percentage of wage of average production worker received by a person with no pension contributions whatsoever); expected pension duration in years (based on the difference between the standard retirement age and life expectancy) and years of qualification for the standard pension; and the ratio of employee to employer funding. Critically, the PGEN indicator is ‘based on the structure of benefits for a new retiree in the specified year, and not spending levels” so [pension rights generosity] reflects more than simply aging population structures’.Footnote 2 If life expectancy increases over time, for example, the PGEN index will also increase over time; thus, not introducing an increase in the retirement age can be viewed as a non‐decision to increase pension rights generosity. Similarly, if wages and/or prices increase over time, the PGEN index will sink, unless governments react. Again, a failure to react to this situation can be viewed as a non‐decision to allow pension rights generosity to drift down. Many legislated pension reforms continue to affect the PGEN year after year. Again, governments have the option of reversing or modifying these reforms, and thus, continued change in the PGEN may be viewed as symptomatic of current governments’ commitment to pension rights generosity as they do not pursue the available option of stepping in to reverse or modify previous pension reform legislation. For these reasons, the PGEN indicator is appropriate for measuring governments’ changing commitments to pension rights, as both pension reforms (such as changes in the benefit formula or the retirement age) as well as policy drift (such as neglecting to increase pension benefits or indexation rates even though the value of average pension benefits may be slowly eroding compared to average wages or prices) will be reflected in the PGEN indicator. We construct a binary indicator for reduction in pension rights generosity that takes the value of 1 if in a year public pension generosity was reduced, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 3 As a validity check, we investigated whether legislated pension reforms actually result in decreases in the pension rights and report the results in the Online Appendix.Footnote 4 In addition, in order to assure that our findings are not driven by smaller changes related to policy drift, we re‐run our main analysis with a dependent variable that only takes on the value of 1 if there is a large shift in the pension generosity index.Footnote 5 The results of these additional analyses can be found in Figures A2 and A3 in the Online Appendix.

We use two additional dependent variables in our analysis based on social spending data. This allows us to more specifically address the dynamics that we have outlined in the theory section. In addition, they help us demonstrate that our findings are not based on idiosyncrasies of the pension generosity data. First, we use a newly constructed new social rights recalibration index as our dependent variable, which consists of the sum of public spending on day care and active labour market policies divided by public spending on old‐age benefits. All indicators are taken from the Comparative Welfare States database (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Huber and Stephens2014). Higher values on this index thus indicate more investment‐oriented spending that is targeted towards new social risk groups relative to traditional consumption‐oriented old‐age spending. Second, we use a measure of pension generosity (as opposed to pension rights generosity) based on spending data. More precisely we use public and mandatory private expenditure on old‐age benefits, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) divided by the size of the population over 65. By standardising pension expenditures by the population over 65, we create a quasi per capita measure for the elderly that captures generosity largely independent of the number of recipients and thus of demographic trends. As the traditional conservative party profile is defined by fiscal prudence, we expect that conservative parties restrain pension expenditures unless electoral competition increases.Footnote 6

Three main independent variables of interest are necessary to test our hypotheses: (1) government ideology, (2) electoral competitiveness and (3) radical right party presence. We define a left government as one that does not include a conservative or radical right party; a right government is a government without a left party. This coding of government ideology differs from other studies which calculate some variant of a weighted average of government parties’ policy positions (Huber & Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Allan & Scruggs Reference Allan and Scruggs2004). In contrast to this operationalisation, we follow a veto player logic of policy making (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002). It makes a significant difference if a government contains either exclusively left parties or right parties – or, if it includes a party from across the aisle. For, if this is indeed the case, a veto player from the opposing camp can veto government policy proposals. Therefore, we define a left government not by its degree of ‘leftness’, but by the absence of a conservative partisan veto player – that is, a centre‐right or radical right party in government that has the potential to block legislation. Similarly a right government is defined by the absence of a left‐of‐centre veto player.Footnote 7 We prefer this measure of government ideology for two main reasons. First, our expectations are based on the preferences of constituencies of party types and not a linear relation of party positions and voter preferences. In other words, we do not expect our findings to vary with differences in the leftness of social democratic parties, for example. Second, a gradual measure of party ideology contains a much higher risk of an endogenous relationship. Continuous measures of party ideology based on manifestos or expert coding are likely affected by the pension policies enacted by these parties. However, in order to demonstrate that our findings do not constitute artifacts of our coding of government ideology, in Figure A6 in the Online Appendix we show that our main findings hold using a dichotomous variable of left versus right government based on the weighted average of a government's left‐right position calculated from the CMP data (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens2017). Figure A1 in the Online Appendix additionally shows that all three types of governments, on average, lead to the same amount of reduction in pension rights generosity. These findings are a first indication that neither partisanship nor blame avoidance coalitions alone can account for the dynamics of pension politics in post‐industrial societies.

In order to investigate the effect of electoral competitiveness, we employ a novel measure proposed by Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski (Reference Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski2016). This measure defines the degree of electoral competition a party is facing as the probability of a vote shift occurring that changes the party's bargaining position in the legislature. While conceptions of the degree of electoral competition within democracies have long been a part of political science arguments (e.g., on the effects of electoral systems), only recently have scholars begun to construct measures that adequately capture degrees of competitiveness in multiparty systems (Kayser & Lindstädt Reference Kayser and Lindstädt2015). Conceptually, the core of these measures lies in connecting shifts in votes to shifts in power. And indeed, some studies can demonstrate how varying degrees of competition affect policy making and social policy more specifically (Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008; Immergut & Abou‐Chadi Reference Immergut and Abou‐Chadi2014; Hübscher & Sattler Reference Hübscher and Sattler2017). Crucially, in contrast to these studies, we are interested in the interaction of degrees of competitiveness with party strategies. We thus rely on the measure provided by Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski (Reference Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski2016), which is the only measure that truly varies at the party level.Footnote 8

The basic idea of the Abou‐Chadi/Orlowski measure is that parties exercise power by contributing to legislative majorities. Parties that command absolute majorities in the legislature can be seen as most powerful followed by parties that only need few coalition partners to form a winning coalition and so on. Based on this conception of power, the crucial question for competitiveness becomes how likely shifts in votes will occur that change this bargaining position of a party in a legislature. Two components are necessary to estimate this quantity of interest. First, it is necessary to estimate how insulated parties are against vote shifts – that is, how many votes a party has to win or lose until changes of its position in the legislative party system occur. Consequently, a full calculation of electoral insulation requires information on the electoral system, geographical distributions of party competition and which parties are more likely to attract voters from one another. This is achieved in two steps: the derivation of an optimisation problem from a set of inequalities describing the bargaining position of each party in a legislature; and the estimation of seats‐votes curves for all parties to express every party's seat share as a function of its own and every other party's vote share (Abou‐Chadi & Orlowski Reference Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski2016). This procedure results in two quantities defining a party's insulation to vote shifts: an upper bound of each party's future vote share that, when exceeded, will improve a party's bargaining position; and a lower bound that has to be kept in order not to worsen a party's bargaining position.

However, a party's insulation of vote shifts alone does not define the degree of electoral competitiveness yet. The crucial second question is how likely a vote shift of this magnitude will occur. Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski (Reference Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski2016) estimate this likelihood based on individual‐level voting data. The crucial idea here is that the number of party identifiers in the electorate as well as the strength with which party identification affects vote choice provide parties with an approximation of what vote share they can reasonably expect at future elections. Simply put, a party with a large share of identifiers (e.g., a northern European social democratic party) should expect a higher vote share than a party with a small group of identifiers. More precisely Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski (Reference Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski2016) fit conditional logit models on individual‐choice pairs where the only predictor is a binary variable indicating whether an individual identifies with the specific party. Based on these models they estimate parties’ expectations about future vote shares including four sources of uncertainty through simulation: the strength of party identification as a predictor for vote choice; the share of non‐identifiers in the electorate and their voting behaviour; the uncertainty associated with any attempt to identify the previous two factors; and the question of how well even a valid model based on information about a current election is suited to predict the outcomes of future elections. It is important to point out that our measure of competitiveness does not rely on information about parties’ policy positions. It is thus unlikely that it is by construction correlated with the emergence of radical right parties or the pension policy preferences of political parties.

The resulting composite measure of electoral competitiveness ranges from 0 to 1 for every party. It represents the probability of a vote shift occurring that is big enough to surpass the insulation boundaries for a given party. For our analyses we use the competitiveness value of the party that leads the government. In order to evaluate our hypotheses, we estimate two models: one where we interact the measure of left government with the measure of competitiveness, and one where we do the same for the right government dummy.Footnote 9

In order to test how the effect of competitiveness on pension reforms depends on the presence of a radical right party, we add a binary indicator for the representation of a radical right party in parliament. If radical right parties make it into parliament this signals to other parties that they are a credible challenger that has proven the necessary capacity for a minimum amount of electoral success.Footnote 10

We add a number of control variables that have been shown to affect welfare state efforts and that are possibly correlated with our main variables of interest.Footnote 11 First, we include a measure of institutional veto points. Veto points have been shown to impede the development of social security systems in the expansion phase of the welfare state, but results for the ‘silver age’ of the welfare state are more mixed (Swank Reference Swank2002; Allan & Scruggs Reference Allan and Scruggs2004). Especially in the area of pension politics, several scholars show that veto points do not necessarily impede change but may even be conducive for it as they allow blame sharing (Pierson & Weaver Reference Pierson, Weaver, Weaver and Rockman1993; Bonoli Reference Bonoli and Pierson2001; Schludi Reference Schludi2005). In contrast to existing studies that often rely on additive indices of veto points that are time‐invariant, and more in line with the original theory, we use a dynamic definition of veto points. We code an open veto point as 1 for a country‐year where government parties do not have a majority in the first or second chamber of parliament (if the second chamber has de jure veto power) or if a president with veto power of another party is in office.Footnote 12 Second, we include a number of macroeconomic and demographic indicators that have been shown to affect party positioning and issue choice, as well as policy developments more generally (Ward et al. Reference Ward, Ezrow and Dorussen2011; Greene Reference Greene2016; Bevan & Greene Reference Bevan and Greene2017). All of these have been collected for the Comparative Welfare States database (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Huber and Stephens2014). We control for the share of the population over 65, the harmonised unemployment rate and GDP per capita (logged) as domestic factors that affect welfare state efforts. We also include a dummy variable for the years of the global economic and financial crisis starting in 2008. Several scholars argue that globalisation and regional integration affect national systems of social security (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Beckfield and Seeleib‐Kaiser2005). Hence, we include controls for trade openness and EU membership. Third, following power resource approaches (next to our variables for government ideology), we control for union density, female labour force participation and the type of welfare state regime. In the following analyses, all independent variables are lagged by one year. As we argued that pension reforms can also lead to reductions in pension rights generosity in the same year, we re‐run our main analyses without lagging our independent variables. None of our main findings are affected by this alternative specification. The according results as well as summary statistics for all independent variables can be found in Figures A4 and A5 in the Online Appendix.

Since our main dependent variable is a binary indicator within a time‐series cross‐section set up we follow Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Katz and Tucker1998) and estimate a complementary loglog (cloglog) model and correct for serial dependence by including a spell counter (for the years leading up to a reform) and three natural cubic splines. In addition to this, the standard errors are clustered by countries. We also estimated the models using several variations of this approach including a logit link instead of a cloglog link; spell dummies instead of splines and the cubic polynomial splines suggested by Carter and Signorino (Reference Carter and Signorino2010). We also run our models without clustering our standard errors. All main findings are robust against these alternative specifications.

Results

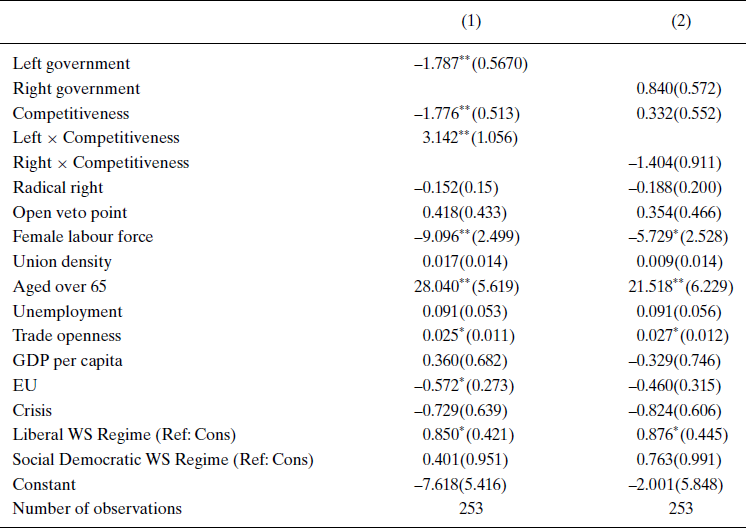

Our first hypothesis pertained to the impact of electoral competition on the behaviour of left governments. This is tested in model 1, for which the results are presented in Table 1. Here we find significant effects for the interaction of electoral competition and government ideology, as well as for both constituent terms. In addition, Table 1 shows that most of our independent variables show a sign in the predicted direction, but that only some of them reach statistical significance at a conventional level. ‘Problem pressure’, operationalised as the size of the population over 65, increases the likelihood of pension reform. In line with the power resources approach, liberal welfare regimes are more likely to reduce pension rights generosity. Female labour force participation, by contrast, significantly reduces this likelihood. For trade openness, we also find a significant positive effect, indicating that globalisation is associated with a decrease in pension rights generosity, thus supporting the competition rather than the compensation hypothesis.

Table 1. Determinants of pension rights change

Notes: Cloglog models for pension reform. Clustered standard errors in parentheses. All models include a spell‐counter and three cubic splines. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

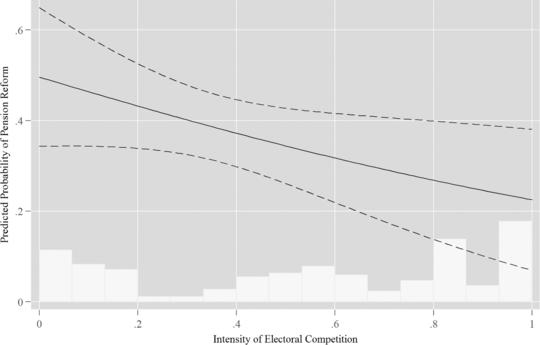

As in a non‐linear model the interaction term does not provide us with sufficient information for evaluating the relationship under investigation (Ai & Norton Reference Ai and Norton2003), we turn now to the predicted probabilities derived from model 1. Figure 1Footnote 13 shows how the predicted probabilities for left governments to reduce pension rights generosity change with electoral competitiveness.Footnote 14 We can see that with increasing intensity of electoral competition, left governments indeed become substantially more likely to reduce pension rights generosity. For a competitiveness value of 0.1 the predicted probability for a left government to reduce pension rights generosity lies at about 0.18, while for a high degree of competitiveness it is about 0.42 and thus more than twice as high. The average marginal effect of a change in electoral competitiveness from 0 to 1 amounts to a change in the predicted probability of pension rights generosity reduction of 0.3.Footnote 15 Hence, we find empirical support for H1. With increasing levels of electoral competition, left governments become more likely to recalibrate pension systems and reduce the generosity of pension rights.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities of reduction in pension rights generosity for left governments.

Note: Dashed lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

In model 2 (also in Table 1), we tested the prediction that enhanced electoral competition would reduce the likelihood that right governments (defined as those lacking a left party) would reduce pension rights generosity. Figure 2 shows the predicted probabilities for a right government reducing pension rights generosity based on this model. For right governments we find that increasing levels of competitiveness substantially reduce the likelihood of reductions of pension rights. For a competitiveness value of 0.1 the predicted probability for a right government to reduce pension rights generosity lies at about 0.46, while for a value of 0.9 it is reduced to about 0.25. The average marginal effect for a change in competitiveness from 0 to 1 is a change in the predicted probability of reform of –0.27. We can thus confirm H2. With increasing levels of competitiveness, right governments become less likely to reduce pension rights generosity.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of reduction in pension rights generosity for right governments.

Note: Dashed lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

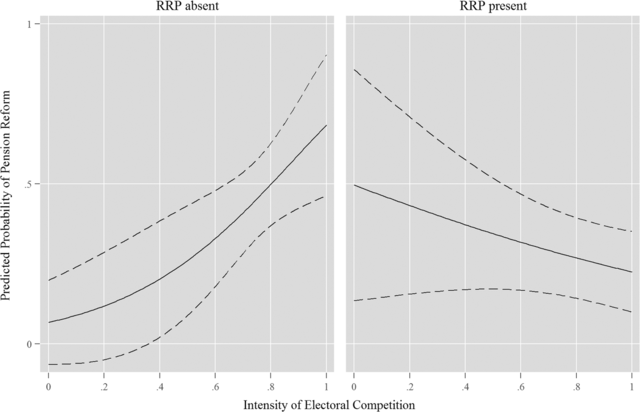

We additionally investigate how the presence of a radical right challenger affects the interaction of government ideology with electoral competitiveness. A successful radical right party will make welfare state recalibration a much more risky electoral strategy for left parties. While they should still be able to attract educated middle‐class voters with this strategy, the likelihood of losing the working‐class vote increases dramatically in the presence of a credible radical right challenger. Figure 3 shows results that support this expectation. The regression table for this analysis can be found in the Online Appendix. We can see the predicted probability of a left government reducing pension rights generosity is conditional on the degree of electoral competition. The left panel shows the effect with no radical right party represented in parliament, while the right panel shows the effect if there is at least one. We can see that the positive effect that we reported in the previous analysis is a lot more pronounced if there is no credible radical right challenger. On the other hand, if there is a radical right party in parliament we do not find this effect – it is even slightly negative albeit far from being significant.

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities of reduction in pension rights generosity for left governments conditional on RRP presence.

Note: Dashed lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

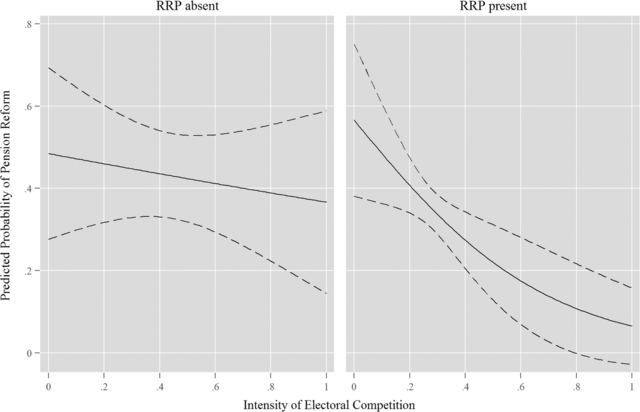

For centre‐right governments we should expect that the presence of a credible radical right challenger increases the negative effect that competitiveness has on the likelihood of a reduction in pension rights generosity. Again, with an additional competitor for the working‐class vote, reducing traditional welfare benefits becomes a lot more risky. Moreover, the politicisation of second‐dimension politics that goes along with a successful radical right party can be beneficial for mainstream right parties in their competition with the mainstream left (Bale Reference Bale2003; Abou‐Chadi Reference Abou‐Chadi2016). They, thus, do not have an interest in putting welfare state policies more prominently onto the agenda by reducing pension rights generosity. Figure 4 again empirically supports this intuition. We can see that in both panels competitiveness has a negative effect on the likelihood of a centre‐right government reducing pension rights generosity. This effect, however, is a lot more pronounced when a radical right party is represented in parliament. In cases where mainstream right parties expect elections to be very competitive and are facing a radical right challenger their likelihood of reducing pension rights generosity becomes minimal.

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of reduction in pension rights generosity for right governments conditional on RRP presence.

Note: Dashed lines indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

New social rights recalibration

We will present analyses for two additional dependent variables in order to investigate more specifically how reductions in pension generosity are potentially related to attempts to provide coverage for new social risks or to reducing generosity per se. As outlined earlier, we use a new social rights recalibration index that measures public spending on day care and active labour market policies in relation to spending on old‐age benefits as well as a measure of pension generosity as quasi per capita old‐age spending. Since these new dependent variables are continuous, our strategy to deal with the time‐series cross‐section nature of the data differs from the previous models. We include a lagged dependent variable to model a first‐order autoregressive process, country‐fixed effects to control for country specific heterogeneity and we estimate the model using ordinary least squares (OLS) with panel corrected standard errors (Beck & Katz Reference Beck and Katz1995). In what follows, we present graphs with the marginal effects for our relationship of interest. The regression table with the full results can be found in the Online Appendix.

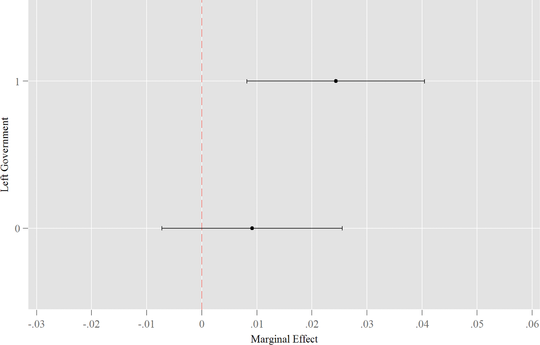

Since our theorised effect for the interaction of left government with electoral competitiveness implies that social democratic parties reduce traditional welfare benefits partly in order to recalibrate the welfare state towards other types of needs, we test our interaction of left government with the degree of electoral competition using the recalibration index as a dependent variable. The marginal effects in Figure 5 represent this relationship. The figure shows the marginal effect of competitiveness (with a 95 per cent confidence interval) on our recalibration index for left and non‐left governments. We can see a significant positive effect for left governments. With increasing levels of electoral competitiveness, left governments spend more on day care and active labour market policies versus old‐age benefits. This is in line with our expectation that when left parties expect elections to be more competitive they increasingly appeal to high‐skilled, female, middle‐class voters and follow less their traditional working‐class ideology that is related to the traditional welfare state in the form of generous, earnings‐related pensions.

Figure 5. Marginal effect of competitiveness on new social rights recalibration.

Note: Horizontal bars indicate the 95 per cent confidence intervals. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

As a second analysis we use spending on old‐age benefits divided by the population over 65 in order to test if higher competitiveness for right governments is indeed associated with higher pension generosity. Figure 6 shows the marginal effect of competitiveness on pension generosity for right and non‐right governments. Again, in line with our argumentation, we find that competitiveness has a positive effect on generosity for centre‐right governments. With increasing competitiveness these parties refrain from reducing pension generosity.

Figure 6. Marginal effect of competitiveness on pension generosity.

Note: Horizontal bars indicate the 95 per cent confidence intervals. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Conclusion

Welfare states in an age of austerity can be sustained only by continual recalibration in light of changing demographic and economic conditions, and the diversified social policy preferences of changing constituencies. In this article, we contribute to the new partisanship view on the politics of the welfare state. We can show that left and right parties have, indeed, departed from their traditional policy positions on social policies, and that these departures can be explained by the changing electoral constituencies for these parties, as analysed in the new partisanship literature. This departure, however, depends on the degree of electoral competition that these parties are facing. Left parties in government become more likely to cut pension rights generosity and to recalibrate social policy in order to favour social investment when electoral competition increases. The opposite is true for centre‐right parties.

By emphasising the role of electoral competition, we contribute to the debate about the role of context in understanding the policy‐responsiveness of political parties. This has implications for a range of topics beyond the welfare state, including economic voting and issue evolution. In contrast to approaches that focus on the electoral system per se, however, we show that the intensity of electoral competition – which depends upon an interaction among electoral rules, voter results and party strategies – varies over time within a given electoral system, and that it has an independent effect on parties’ policy choices. Further, in line with recent research about party strategies, we show that the reaction of parties to electoral competition depends upon their ideological placement and strategic positioning, particularly with regard to right‐wing challengers.

Further research on a broader array of policies, as well as analysis of vote gains and losses between elections, would contribute to a more precise analysis of the dynamics of party positioning. Furthermore, we have not considered all possible constituent changes or types of parties. Thus, a more fine‐grained analysis of party types and their constituencies should be fruitful for future research. In particular, distinctions among different types of outsiders, their skill‐levels, their preferences and party allegiances, as well as more consideration of the role of Christian democratic parties, left parties and green parties would enrich the analysis. Here, we do show, however, that governments’ policy output is influenced by their competitive situation in the preceding election, and that a government's policy priorities vary based on the impact of potential voter losses on its legislative bargaining position. Consequently, governments interpret their electoral mandate based on their competitive situation, and are thus differentially accountable to particular sub‐sets of their constituents. In this way, institutions do indeed constitute a ‘mobilisation of bias’, but one that is produced by interactions among institutions and strategic political behaviour of self‐reflective actors.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at the 2015 annual meetings of the European Political Science Association and the American Political Science Association as well as at the State and Capitalism Seminar the Center for European Studies, Harvard University. For helpful comments and feedback we wish to thank Peter Hall, Silja Häusermann, Herbert Kitschelt, Kati Kuitto, Katja Möhring, Matthias Orlowski, Philipp Rehm, Konstantin Vössing and Markus Wagner as well as two anonymous reviewers and the editors of the EJPR. This research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, grant IM 35/3‐1) and the NORFACE Welfare State Futures Programme (HEALTHDOX, grant 462‐14‐070; with ERA‐Net Plus funding, grant 618106).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix:

Figure A1: Distribution of pension reforms by government type

Figure A2: Average marginal effect on predicted probability of pension reform for left governments

Figure A3: Average marginal effect on predicted probability of pension reform for right governments

Figure A4: Average marginal effect on predicted probability of pension reform for left governments. Independent variables not lagged

Figure A5: Average marginal effect on predicted probability of pension reform for right governments. Independent variables not lagged

Figure A6: Main findings using government coding according to ideology based on manifesto data

Figure A7: Main findings controlling for number of partisan veto players

Table A1: Summary statistics

Table A2: Radical Right Moderation

Table A3: Recalibration and Generosity