1 Introduction

In this paper, we explore autonomous agents operating in dynamic environments governed by policies or norms, including cultural conventions and regulations. Our focus is on agents whose knowledge bases and reasoning algorithms are encoded in logic programming, specifically Answer Set Programming (ASP) (Gelfond and Lifschitz Reference Gelfond and Lifschitz1991; Marek and Truszczynski Reference Marek and Truszczynski1999). We introduce a framework that enables these policy-aware agents to assess potential penalties for noncompliance and generate suitable plans for their goals.

Research on norm-aware autonomous agents predominantly focuses on compliance (e.g., (Oren et al. Reference Oren, Vasconcelos, Meneguzzi and Luck2011; Alechina et al. Reference Alechina, Dastani and Logan2012)). However, studying noncompliant agents is equally important for two key reasons. First, autonomous agents may be tasked with high-stakes objectives (e.g., assisting in rescue operations) that can only be achieved through selective noncompliance. In such cases, identifying optimal noncompliant plans that accomplish the goal while minimizing repercussions is crucial. Second, our framework can support policymakers by enabling policy-aware agents to model human behavior. Humans do not always adhere to norms and often seek to minimize penalties for noncompliance. By simulating different compliance attitudes, policymakers can identify potential weaknesses in policies and refine them accordingly.

To enable autonomous agents to reason about policies, evaluate penalties for noncompliance, and generate optimal plans based on their circumstances and given norms, we must first encode these policies. In our proposed framework, policies are specified in the Authorization and Obligation Policy Language (

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

) by Gelfond and Lobo (Reference Gelfond and Lobo2008), whose semantics are defined via a translation into ASP. We expand

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

) by Gelfond and Lobo (Reference Gelfond and Lobo2008), whose semantics are defined via a translation into ASP. We expand

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

to enable the representation of, and reasoning about, penalties that may be incurred for noncompliance with a policy. We develop an automated translation of the extended

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

to enable the representation of, and reasoning about, penalties that may be incurred for noncompliance with a policy. We develop an automated translation of the extended

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

, referred to as

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

, referred to as

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

, into ASP and refine ASP-based planning algorithms to incorporate penalty considerations.

$\mathscr{P}$

, into ASP and refine ASP-based planning algorithms to incorporate penalty considerations.

Using a high-level language such as

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

for representing policies and penalties offers several advantages over alternative approaches, which may include encoding policies as soft constraints in ASP (Calimeri et al. Reference Calimeri, Faber, Gebser, Ianni, Kaminski, Krennwallner, Leone, Maratea, Ricca and Schaub2020). One key benefit is that

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

for representing policies and penalties offers several advantages over alternative approaches, which may include encoding policies as soft constraints in ASP (Calimeri et al. Reference Calimeri, Faber, Gebser, Ianni, Kaminski, Krennwallner, Leone, Maratea, Ricca and Schaub2020). One key benefit is that

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

ensures the policy is well-structured, with built-in mechanisms to detect issues like inconsistencies, ambiguities, and underspecification (Inclezan Reference Inclezan2023). Additionally,

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

ensures the policy is well-structured, with built-in mechanisms to detect issues like inconsistencies, ambiguities, and underspecification (Inclezan Reference Inclezan2023). Additionally,

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

’s syntax and semantics support the representation of priorities between policy statements, allowing for the determination of which statements apply at different points in time. Moreover, our

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

’s syntax and semantics support the representation of priorities between policy statements, allowing for the determination of which statements apply at different points in time. Moreover, our

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

-based approach enhances explainability by identifying which policy rules an agent violated and how these violations led to accumulated penalties – something that would be difficult to achieve using soft constraints.

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-based approach enhances explainability by identifying which policy rules an agent violated and how these violations led to accumulated penalties – something that would be difficult to achieve using soft constraints.

In previous work on policy-aware autonomous agents, Harders and Inclezan (Reference Harders and Inclezan2023) introduced behavior modes to capture different attitudes toward policy compliance, allowing noncompliant actions within the Risky mode. While this framework established a foundation for reasoning about noncompliance, it ranked plans in the Risky mode solely by their length, without accounting for the number or proportion of noncompliant actions or the severity of the violated rules. However, other behavior modes – excluding noncompliant ones – did consider the proportion of explicitly known compliant actions, for example.

In this work, we extend that approach by introducing a more nuanced evaluation of noncompliance, enabling agents to weigh trade-offs between policy violations and their objectives more effectively. Our framework distinguishes between noncompliant plans using penalties, allowing agents to achieve their goals while minimizing repercussions. Experimental results show that our approach generates higher-quality plans. For example, in a Traffic Norms domain, it selects an optimal driving speed and avoids actions potentially harmful to humans. Such factors are overlooked by the previous framework, which accounts only for plan length while ignoring execution time (and thus driving speed) and gives no special consideration to preventing human harm. Additionally, for certain domains, our method demonstrates improved efficiency. A preliminary version of this work appears in (Tummala and Inclezan Reference Tummala and Inclezan2024).

The rest of the paper starts with background information in Section 2, followed by a motivating example in Section 3. We present our framework in Section 4, which includes the extension of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

with penalties (

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

with penalties (

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

), an automated translator from

$\mathscr{P}$

), an automated translator from

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

to ASP, penalty-aware planning, and revised behavior modes. We present experimental results in Section 5. We discuss related work in Section 6 and end with conclusions and future work in Section 7.

$\mathscr{P}$

to ASP, penalty-aware planning, and revised behavior modes. We present experimental results in Section 5. We discuss related work in Section 6 and end with conclusions and future work in Section 7.

2 Background

We now provide background on the norm-specification language

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

and our previous work on policy-aware planning agents. We assume readers are familiar with ASP or can consult external resources (e.g., (Gelfond and Lifschitz Reference Gelfond and Lifschitz1991; Gelfond and Kahl Reference Gelfond and Kahl2014; Calimeri et al. Reference Calimeri, Faber, Gebser, Ianni, Kaminski, Krennwallner, Leone, Maratea, Ricca and Schaub2020)) as needed.

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

and our previous work on policy-aware planning agents. We assume readers are familiar with ASP or can consult external resources (e.g., (Gelfond and Lifschitz Reference Gelfond and Lifschitz1991; Gelfond and Kahl Reference Gelfond and Kahl2014; Calimeri et al. Reference Calimeri, Faber, Gebser, Ianni, Kaminski, Krennwallner, Leone, Maratea, Ricca and Schaub2020)) as needed.

2.1 Policy-specification language

$\mathscr{\textbf{AOPL}}$

$\mathscr{\textbf{AOPL}}$

Gelfond and Lobo (Reference Gelfond and Lobo2008) designed the Authorization and Obligation Policy Language

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

for specifying policies for an intelligent agent acting in a dynamic environment. A policy is a collection of authorization and obligation statements. An authorization indicates whether an agent’s action is permitted or not, and under which conditions. An obligation specifies whether an agent is required or not required to perform a particular action or to abstain from it under given conditions. An

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

for specifying policies for an intelligent agent acting in a dynamic environment. A policy is a collection of authorization and obligation statements. An authorization indicates whether an agent’s action is permitted or not, and under which conditions. An obligation specifies whether an agent is required or not required to perform a particular action or to abstain from it under given conditions. An

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy assumes that the agent’s environment is described using an action language, a high-level language designed to concisely and accurately represent action preconditions as well as the direct and indirect effects of actions. Over time, various action languages have been developed (e.g.,

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy assumes that the agent’s environment is described using an action language, a high-level language designed to concisely and accurately represent action preconditions as well as the direct and indirect effects of actions. Over time, various action languages have been developed (e.g.,

![]() $\mathscr{A}$

(Gelfond and Lifschitz Reference Gelfond and Lifschitz1993),

$\mathscr{A}$

(Gelfond and Lifschitz Reference Gelfond and Lifschitz1993),

![]() $\mathscr{B}$

(Gelfond and Lifschitz Reference Gelfond and Lifschitz1998),

$\mathscr{B}$

(Gelfond and Lifschitz Reference Gelfond and Lifschitz1998),

![]() $\mathscr{C+}$

(Giunchiglia et al. Reference Giunchiglia, Lee, Lifschitz, Mccain and Turner2004),

$\mathscr{C+}$

(Giunchiglia et al. Reference Giunchiglia, Lee, Lifschitz, Mccain and Turner2004),

![]() $\mathscr{H}$

(Chintabathina et al. Reference Chintabathina, Gelfond and Watson2005),

$\mathscr{H}$

(Chintabathina et al. Reference Chintabathina, Gelfond and Watson2005),

![]() $\mathscr{AL}_d$

(Gelfond and Inclezan Reference Gelfond and Inclezan2013), etc.), including modular action languages such as MAD (Lifschitz and Ren Reference Lifschitz and Ren2006) and

$\mathscr{AL}_d$

(Gelfond and Inclezan Reference Gelfond and Inclezan2013), etc.), including modular action languages such as MAD (Lifschitz and Ren Reference Lifschitz and Ren2006) and

![]() $\mathscr{ALM}$

(Inclezan Reference Inclezan2012). They all incorporate means for dealing with the ramification and qualification problems, as well as the law of inertia (i.e., domain properties not affected by actions remain unchanged).

$\mathscr{ALM}$

(Inclezan Reference Inclezan2012). They all incorporate means for dealing with the ramification and qualification problems, as well as the law of inertia (i.e., domain properties not affected by actions remain unchanged).

A system description written in an action language defines the domain’s transition diagram whose states are complete and consistent sets of static (i.e., immutable) and fluent literals (i.e., properties of the domain that may be changed by actions), and whose arcs are labeled by actions. The signature of the dynamic system description (which includes predicates denoting sorts, statics, fluents, and actions) is included in the signature of an

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy for that dynamic domain. Additionally, the signature of an

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy for that dynamic domain. Additionally, the signature of an

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy includes predicates

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy includes predicates

![]() $permitted$

for authorizations,

$permitted$

for authorizations,

![]() $obl$

for obligations, and prefer for specifying preferences between authorizations or between obligations. A prefer atom is created from the predicate prefer; similarly, for

$obl$

for obligations, and prefer for specifying preferences between authorizations or between obligations. A prefer atom is created from the predicate prefer; similarly, for

![]() $permitted$

and

$permitted$

and

![]() $obl$

atoms. A literal is an atom or its negation.

$obl$

atoms. A literal is an atom or its negation.

An

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

is a finite collection of statements of the form:

$\mathscr{P}$

is a finite collection of statements of the form:

where

![]() $e$

is an elementary action;

$e$

is an elementary action;

![]() $h$

is a happening (i.e., an elementary action or its negationFootnote

1

);

$h$

is a happening (i.e., an elementary action or its negationFootnote

1

);

![]() $cond$

is a set of literals of the signature, except for prefer literals;

$cond$

is a set of literals of the signature, except for prefer literals;

![]() $d$

appearing in (1e)–(1h) denotes a defeasible rule label; and

$d$

appearing in (1e)–(1h) denotes a defeasible rule label; and

![]() $d_i$

,

$d_i$

,

![]() $d_j$

in (1i) refer to distinct defeasible rule labels from

$d_j$

in (1i) refer to distinct defeasible rule labels from

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

. Rules (1a)–(1d) encode strict policy statements, while rules (1e)–(1h) encode defeasible statements (i.e., statements that may have exceptions). Rule (1i) captures priorities between defeasible statements only. It specifies that a defeasible rule labeled

$\mathscr{P}$

. Rules (1a)–(1d) encode strict policy statements, while rules (1e)–(1h) encode defeasible statements (i.e., statements that may have exceptions). Rule (1i) captures priorities between defeasible statements only. It specifies that a defeasible rule labeled

![]() $d_i$

overrides a defeasible rule labeled

$d_i$

overrides a defeasible rule labeled

![]() $d_j$

, rendering the latter inapplicable when the condition of the former (i.e., of

$d_j$

, rendering the latter inapplicable when the condition of the former (i.e., of

![]() $d_i$

) is satisfied. Strict rules, whenever their condition

$d_i$

) is satisfied. Strict rules, whenever their condition

![]() $cond$

is satisfied, always override the defeasible rules they conflict with. Unlike deontic logic, the

$cond$

is satisfied, always override the defeasible rules they conflict with. Unlike deontic logic, the

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

language described by Gelfond and Lobo does not assume an equivalence between rules for

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

language described by Gelfond and Lobo does not assume an equivalence between rules for

![]() $\neg permitted(e)$

and

$\neg permitted(e)$

and

![]() $obl(\neg e)$

. We believe this choice was made to allow for different interpretations and to accommodate other types of logics. Such an equivalence can be implemented by adding the following rules to an

$obl(\neg e)$

. We believe this choice was made to allow for different interpretations and to accommodate other types of logics. Such an equivalence can be implemented by adding the following rules to an

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

:

$\mathscr{P}$

:

However, the lack of a clear relationship between permissions and obligations can give rise to modality conflicts, a term introduced by Craven et al. (Reference Craven, Lobo, Ma, Russo, Lupu and Bandara2009), as noted by Inclezan (Reference Inclezan2023). For example, an

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy may derive both

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy may derive both

![]() $\neg permitted(e)$

and

$\neg permitted(e)$

and

![]() $obl(e)$

for the same elementary action

$obl(e)$

for the same elementary action

![]() $e$

in a given state, which is an undesirable outcome, as it appears contradictory.

$e$

in a given state, which is an undesirable outcome, as it appears contradictory.

The semantics of an

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy determine a mapping

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy determine a mapping

![]() $\mathscr{P}(\sigma )$

from states of a transition diagram

$\mathscr{P}(\sigma )$

from states of a transition diagram

![]() $\mathscr{T}$

into a collection of

$\mathscr{T}$

into a collection of

![]() $permitted$

and

$permitted$

and

![]() $obl$

literals, obtained from the policy statements that are applicable in state

$obl$

literals, obtained from the policy statements that are applicable in state

![]() $\sigma$

(i.e., have a satisfied

$\sigma$

(i.e., have a satisfied

![]() $cond$

and are not overridden). To formally describe the semantics of

$cond$

and are not overridden). To formally describe the semantics of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

, a translation of a policy

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

, a translation of a policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

and a state

$\mathscr{P}$

and a state

![]() $\sigma$

of the transition diagram into ASP is defined as

$\sigma$

of the transition diagram into ASP is defined as

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

. Properties of an

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

. Properties of an

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

are defined in terms of the answer sets of the logic program

$\mathscr{P}$

are defined in terms of the answer sets of the logic program

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

expanded with appropriate rules. Gelfond and Lobo define a policy as consistent if, for every state

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

expanded with appropriate rules. Gelfond and Lobo define a policy as consistent if, for every state

![]() $\sigma$

of

$\sigma$

of

![]() $\mathscr{T}$

, the logic program

$\mathscr{T}$

, the logic program

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

is consistent (i.e., has an answer set). A policy is categorical if

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

is consistent (i.e., has an answer set). A policy is categorical if

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

has exactly one answer set for every state

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

has exactly one answer set for every state

![]() $\sigma$

of

$\sigma$

of

![]() $\mathscr{T}$

.

$\mathscr{T}$

.

In our work, we adopt established definitions for classifying events as strongly-compliant (i.e., explicitly permitted), underspecified (i.e., neither explicitly permitted nor explicitly prohibited), or noncompliant (i.e., explicitly prohibited) with respect to authorizations, and as compliant or noncompliant with respect to obligations. Formal definitions for these concepts, adapted from Gelfond and Lobo (Reference Gelfond and Lobo2008) and Inclezan (Reference Inclezan2023), are provided below. Note that

![]() $ca$

denotes a compound action, while

$ca$

denotes a compound action, while

![]() $e$

refers to an elementary action. An event

$e$

refers to an elementary action. An event

![]() $\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is a pair consisting of a state

$\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is a pair consisting of a state

![]() $\sigma$

and a (possibly compound) action

$\sigma$

and a (possibly compound) action

![]() $ca$

occurring in that state. If

$ca$

occurring in that state. If

![]() $l$

is a literal, then

$l$

is a literal, then

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

![]() $\models l$

, read as “the logic program

$\models l$

, read as “the logic program

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

entails

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

entails

![]() $l$

,” denotes that

$l$

,” denotes that

![]() $l$

belongs to every answer set of

$l$

belongs to every answer set of

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

. Similarly,

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

. Similarly,

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

![]() $\not \models l$

read as “the logic program

$\not \models l$

read as “the logic program

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

does not entail

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

does not entail

![]() $l$

,” denotes that

$l$

,” denotes that

![]() $l$

does not appear in any of the answer sets of

$l$

does not appear in any of the answer sets of

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

.

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

.

Definition 1 (Compliance for Authorizations).

-

• An event

$\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is strongly-compliant with respect to the authorizations in policy

$\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is strongly-compliant with respect to the authorizations in policy

$\mathscr{P}$

if, for every

$\mathscr{P}$

if, for every

$e \in ca$

, we have that

$e \in ca$

, we have that

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$\models permitted(e)$

.

$\models permitted(e)$

. -

• An event

$\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is underspecified with respect to the authorizations in policy

$\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is underspecified with respect to the authorizations in policy

$\mathscr{P}$

if, for every

$\mathscr{P}$

if, for every

$e \in ca$

, we have that

$e \in ca$

, we have that

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$\not \models permitted(e)$

and

$\not \models permitted(e)$

and

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$\not \models \neg permitted(e)$

.

$\not \models \neg permitted(e)$

. -

• An event

$\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is noncompliant with respect to the authorizations in policy

$\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is noncompliant with respect to the authorizations in policy

$\mathscr{P}$

if, for every

$\mathscr{P}$

if, for every

$e \in ca$

, we have that

$e \in ca$

, we have that

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$\models \neg permitted(e)$

.

$\models \neg permitted(e)$

.

Definition 2 (Compliance for Obligations). An event

![]() $\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is compliant with respect to the obligations in policy

$\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is compliant with respect to the obligations in policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

if

$\mathscr{P}$

if

![]() $\bullet$

For every

$\bullet$

For every

![]() $e$

such that

$e$

such that

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

![]() $\models obl(e)$

we have that

$\models obl(e)$

we have that

![]() $e \in ca$

, and

$e \in ca$

, and

![]() $\bullet$

For every

$\bullet$

For every

![]() $e$

such that

$e$

such that

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

![]() $\models obl(\neg e)$

we have that

$\models obl(\neg e)$

we have that

![]() $e \notin ca$

.

$e \notin ca$

.

Definition 3 (Compliance for Authorization and Obligations). An event

![]() $\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is strongly compliant with arbitrary policy

$\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

is strongly compliant with arbitrary policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

(that may contain both authorizations and obligations) if it is strongly compliant with the authorization component and compliant with the obligation component of

$\mathscr{P}$

(that may contain both authorizations and obligations) if it is strongly compliant with the authorization component and compliant with the obligation component of

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

.

$\mathscr{P}$

.

Inclezan (Reference Inclezan2023) showed that in categorical (i.e., unambiguous) policies, events

![]() $\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

such that

$\langle \sigma , ca \rangle$

such that

![]() $ca$

consists of a single elementary action can be categorized with respect to authorization as either strongly-compliant (i.e., explicitly permitted), noncompliant (i.e., explicitly prohibited), or underspecified (i.e., neither explicitly permitted nor explicitly prohibited). In the case of noncategorical consistent policies, there will be events that lie outside of this categorization (i.e., do not fit in any of these three categories). A typical example of a noncategorical consistent policy is one that consists of two defeasible rules, both applying in a state

$ca$

consists of a single elementary action can be categorized with respect to authorization as either strongly-compliant (i.e., explicitly permitted), noncompliant (i.e., explicitly prohibited), or underspecified (i.e., neither explicitly permitted nor explicitly prohibited). In the case of noncategorical consistent policies, there will be events that lie outside of this categorization (i.e., do not fit in any of these three categories). A typical example of a noncategorical consistent policy is one that consists of two defeasible rules, both applying in a state

![]() $\sigma$

, one deriving

$\sigma$

, one deriving

![]() $permitted(e)$

and the other deriving

$permitted(e)$

and the other deriving

![]() $\neg permitted(e)$

with no preference stated between them. In such a case,

$\neg permitted(e)$

with no preference stated between them. In such a case,

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

has two answer sets where one answer set contains

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma )$

has two answer sets where one answer set contains

![]() $permitted(e)$

, while the other contains

$permitted(e)$

, while the other contains

![]() $\neg permitted(e)$

; hence none of the categories in Definition 1 apply to event

$\neg permitted(e)$

; hence none of the categories in Definition 1 apply to event

![]() $\langle \sigma , e \rangle$

. Similarly, in the case of compound actions (i.e., when the agent executes more than one action at a time). A compound action may include elementary actions belonging to different categories (e.g., one compliant and another underspecified), and thus the compound action itself does not fit into any single category.

$\langle \sigma , e \rangle$

. Similarly, in the case of compound actions (i.e., when the agent executes more than one action at a time). A compound action may include elementary actions belonging to different categories (e.g., one compliant and another underspecified), and thus the compound action itself does not fit into any single category.

In what follows, we assume categorical policies. Handling noncategorical policies is nontrivial and left for future work. However, a well-defined policy is generally expected to be categorical, while a noncategorical (i.e., ambiguous) policy typically reflects a flaw in its specification or design.

2.2 Agent behavior modes with respect to policy compliance

In previous work, Harders and Inclezan (Reference Harders and Inclezan2023) introduced an ASP framework for plan selection in policy-aware autonomous agents, where policies were specified in

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

. They proposed that agents could adopt different attitudes toward norm compliance, influencing the selection of the “best” plan. These attitudes, termed behavior modes, were defined using various metrics to capture different compliance strategies. These metrics included plan length as well as the number and percentage of different types of elementary actions: strongly compliant actions (explicitly permitted), underspecified actions (neither explicitly permitted nor prohibited), and noncompliant actions (violating authorizations or obligations).

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

. They proposed that agents could adopt different attitudes toward norm compliance, influencing the selection of the “best” plan. These attitudes, termed behavior modes, were defined using various metrics to capture different compliance strategies. These metrics included plan length as well as the number and percentage of different types of elementary actions: strongly compliant actions (explicitly permitted), underspecified actions (neither explicitly permitted nor prohibited), and noncompliant actions (violating authorizations or obligations).

The following predefined agent behavior modes were introduced by Harders and Inclezan:

-

• Safe Behavior Mode – prioritizes actions that are explicitly known to be compliant (i.e., maximizes the percentage of strongly-compliant elementary actions first and then plan length) and does not execute noncompliant actions;

-

• Normal Behavior Mode – prioritizes plan length and then actions explicitly known to be compliant (i.e., minimizes plan length first and then maximizes the percentage of strongly-compliant elementary actions), while not executing noncompliant actions; and

-

• Risky Behavior Mode – disregards policies, but does not go out of its way to be noncompliant either. This may result in the inclusion of noncompliant actions if they contribute to minimizing plan length.

Harders and Inclezan (Reference Harders and Inclezan2023) encoded these behavior modes in the ASP-variant that constitutes the input language for the Clingo solver (Gebser et al. Reference Gebser, Kaminski, Kaufmann and Schaub2019) using constraints, employing the

![]() $\#maximize$

and

$\#maximize$

and

![]() $\#minimize$

constructs to express priorities. For instance, in the Safe behavior mode, the planning module included the following rules:

$\#minimize$

constructs to express priorities. For instance, in the Safe behavior mode, the planning module included the following rules:

\begin{align*} \begin{array}{l} \#maximize\ \{N@2\ :\ p\_sa(N)\}\\ \#minimize\ \{N@1\ :\ l(N)\}\\ \leftarrow n\_na(N), \mbox{ not } N = 0\\ \leftarrow n\_no(N), \mbox{ not } N = 0 \end{array} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \begin{array}{l} \#maximize\ \{N@2\ :\ p\_sa(N)\}\\ \#minimize\ \{N@1\ :\ l(N)\}\\ \leftarrow n\_na(N), \mbox{ not } N = 0\\ \leftarrow n\_no(N), \mbox{ not } N = 0 \end{array} \end{align*}

where

![]() $p\_sa$

is the percentage of strongly-compliant elementary actions (with respect to authorizations);

$p\_sa$

is the percentage of strongly-compliant elementary actions (with respect to authorizations);

![]() $l$

is the length of the plan;

$l$

is the length of the plan;

![]() $n\_na$

and

$n\_na$

and

![]() $n\_no$

denote the number of noncompliant elementary actions with respect to authorizations and obligations, respectively.

$n\_no$

denote the number of noncompliant elementary actions with respect to authorizations and obligations, respectively.

3. Motivating example: Traffic norms domain

To illustrate the need for penalties in enabling more nuanced planning, especially allowing certain levels of noncompliance in high-stakes situations, consider a dynamic domain where a self-driving agent navigates a simplified city environment. There are certain norms that the self-driving agent must be aware of when driving, which may represent traffic regulations or cultural conventions. We limit ourselves to one agent, a few traffic signs, and a grid street layout. A schematic view of this Traffic Norms Domain is in Figure 1.

To model this dynamic domain, we consider fourteen locations labeled from

![]() $1$

to

$1$

to

![]() $14$

; a set of driving speeds; traffic light colors red, yellow, and green; and two traffic signs “Stop” and “Do not enter.” One example of a fluent in this domain is

$14$

; a set of driving speeds; traffic light colors red, yellow, and green; and two traffic signs “Stop” and “Do not enter.” One example of a fluent in this domain is

![]() $pedestrians\_are\_crossing(L)$

saying that people are crossing the street at location

$pedestrians\_are\_crossing(L)$

saying that people are crossing the street at location

![]() $L$

. The agent can execute actions:

$L$

. The agent can execute actions:

![]() $drive(L_1, L_2, S)$

to drive between two (connected) locations

$drive(L_1, L_2, S)$

to drive between two (connected) locations

![]() $L_1$

and

$L_1$

and

![]() $L_2$

at a speed

$L_2$

at a speed

![]() $S \gt 0$

; and

$S \gt 0$

; and

![]() $stop(L)$

to stop at

$stop(L)$

to stop at

![]() $L$

.

$L$

.

Fig 1. Layout of the traffic norms domain.

We consider the set of policies in Figure 2. Note that some of these rules represent cultural norms (e.g., rules 1 and 2), while others reflect traffic regulations (e.g., rule 5). For illustration purposes, we consider a system of penalties on a scale from 1 to 3 and discuss potential issues with this choice in Section 4.7. In practice, such penalties would be determined by experts in ethics and traffic regulation; here, we adopt a 3-point scale solely to illustrate the framework. Policy rules 7 and 8 do not have penalties associated with them, as they describe permissions.

Fig 2. Policies and penalties for the traffic norms domain.

Harders and Inclezan (Reference Harders and Inclezan2023) introduced the Risky agent behavior mode for emergency situations. Agents in this mode only look for the shortest plan while ignoring policies. As a result, a Risky agent in the Traffic Norms domain who starts in location 6 and needs to get to location 1, where the speed limit between locations 2 and 1 is 45 mph, may come up with several plans (we don’t specify driving speeds unless relevant to our discussion), including:

-

1. Drive from 6 to 5, from 5 to 4 without stopping for the pedestrians crossing the street, then from 4 to 3, and finally from 3 to 1 (possibly on a red light).

-

2. Drive from 6 to 8 and thus enter a “Do not enter” street, drive from 8 to 7, from 7 to 2, and finally from 2 to 1 at 65 mph.

-

3. Same as plan 2, but drive from 2 to 1 at 45 mph.

According to the definition of Risky agents, all these plans are treated as equivalent, as they consider only plan length without factoring in the severity of infractions, such as the number or gravity of noncompliant actions. Instead, we aim to distinguish between plans containing noncompliant actions and prioritize those that incur the least penalty. In scenarios where a fully compliant plan is unavailable, an agent may need to choose a noncompliant plan to achieve a high-stakes goal. To enable this, we introduce penalties as a means of guiding plan selection.

4 Penalization framework for policy-aware agents

In our framework, we assume that penalties for a domain are set by domain experts in collaboration with specialists in ethics. We consider penalties that are specified as numbers on a given scale. For illustration purposes, we start by considering a scale from 1 to 3, where a 3-point penalty corresponds to situations with a high gravity. We also account for interactions between penalties and other planning-relevant metrics that should be optimized, such as the total execution time of a plan (as opposed to plan length).

In the remainder of this section, we present the implementation of our framework. We first introduce an adaptation of the

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

version first presented by Inclezan (Reference Inclezan2023), which we refer to as

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

version first presented by Inclezan (Reference Inclezan2023), which we refer to as

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

. We then extend

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

. We then extend

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

with penalties, resulting in

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

with penalties, resulting in

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

(i.e.,

$\mathscr{P}$

(i.e.,

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

with penalties), and expand the corresponding ASP translation. An automated translator from

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

with penalties), and expand the corresponding ASP translation. An automated translator from

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

into ASP has been implemented and is described next. We then show how reasoning about penalties in planning is handled in our framework, followed by the incorporation of additional metrics, in particular plan execution time. We also revisit behavior modes in this context and discuss a key refinement needed to prevent harm to humans. The section concludes with a high-level overview of the framework.

$\mathscr{P}$

into ASP has been implemented and is described next. We then show how reasoning about penalties in planning is handled in our framework, followed by the incorporation of additional metrics, in particular plan execution time. We also revisit behavior modes in this context and discuss a key refinement needed to prevent harm to humans. The section concludes with a high-level overview of the framework.

4.1

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

and its ASP translation

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

and its ASP translation

In our work, we build on the

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

version introduced by Inclezan (Reference Inclezan2023), which assumes that all rules – including strict ones – are labeled, unlike in the original definition of the language by Gelfond and Lobo (see Section 2.1). While Gelfond and Lobo assigned labels only to defeasible rules to allow expressing preferences among them, we require labels on both strict and defeasible rules to track which policy rules are violated by an agent. The distinction between defeasible and strict rules specifies only whether a rule can have exceptions to its applicability. It does not determine which rules an agent may violate, as both strict and defeasible applicable rules can be violated. We further extend this version of

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

version introduced by Inclezan (Reference Inclezan2023), which assumes that all rules – including strict ones – are labeled, unlike in the original definition of the language by Gelfond and Lobo (see Section 2.1). While Gelfond and Lobo assigned labels only to defeasible rules to allow expressing preferences among them, we require labels on both strict and defeasible rules to track which policy rules are violated by an agent. The distinction between defeasible and strict rules specifies only whether a rule can have exceptions to its applicability. It does not determine which rules an agent may violate, as both strict and defeasible applicable rules can be violated. We further extend this version of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

by refining its semantics to support reasoning over trajectories in dynamic systems, a key requirement for planning. We refer to this refined version as

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

by refining its semantics to support reasoning over trajectories in dynamic systems, a key requirement for planning. We refer to this refined version as

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

.

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

.

In

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

, rules of a policy may have one of the forms below:

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

, rules of a policy may have one of the forms below:

As in the original

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

language, the rules of

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

language, the rules of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

use the following notation:

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

use the following notation:

![]() $e$

denotes an elementary action,

$e$

denotes an elementary action,

![]() $h$

a happening (i.e., an elementary action or its negation), and

$h$

a happening (i.e., an elementary action or its negation), and

![]() $cond$

a set of literals from the signature, excluding those containing the predicate prefer. Rules (2a)–(2d) represent strict policy rules, now labeled with a label denoted by

$cond$

a set of literals from the signature, excluding those containing the predicate prefer. Rules (2a)–(2d) represent strict policy rules, now labeled with a label denoted by

![]() $r$

. Defeasible rules of types (2e)–(2h) are likewise labeled, as in the earlier version, and contain the keyword normally. As before, preference relationships such as rule (2i) can be specified only between defeasible rules, while strict rules always override the defeasible rules with which they conflict.

$r$

. Defeasible rules of types (2e)–(2h) are likewise labeled, as in the earlier version, and contain the keyword normally. As before, preference relationships such as rule (2i) can be specified only between defeasible rules, while strict rules always override the defeasible rules with which they conflict.

The semantics of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

are given in terms of a translation into ASP. We adapt the translation defined by Inclezan (Reference Inclezan2023) in two ways: first, by introducing discrete time steps to reason over trajectories of multiple steps for planning purposes; and second, by modifying the original translation from the Clingo input language to the ASP-Core-2 standard input language for ASP (Calimeri et al. Reference Calimeri, Faber, Gebser, Ianni, Kaminski, Krennwallner, Leone, Maratea, Ricca and Schaub2020), thereby ensuring compatibility with other solvers such as DLV2 (Alviano et al. Reference Alviano, Calimeri, Dodaro, Fuscá, Leone, Perri, Ricca, Veltri and Zangari2017). This translation is denoted by

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

are given in terms of a translation into ASP. We adapt the translation defined by Inclezan (Reference Inclezan2023) in two ways: first, by introducing discrete time steps to reason over trajectories of multiple steps for planning purposes; and second, by modifying the original translation from the Clingo input language to the ASP-Core-2 standard input language for ASP (Calimeri et al. Reference Calimeri, Faber, Gebser, Ianni, Kaminski, Krennwallner, Leone, Maratea, Ricca and Schaub2020), thereby ensuring compatibility with other solvers such as DLV2 (Alviano et al. Reference Alviano, Calimeri, Dodaro, Fuscá, Leone, Perri, Ricca, Veltri and Zangari2017). This translation is denoted by

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

for an

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

for an

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

policy

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

.

$\mathscr{P}$

.

The signature of

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

for a policy

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

for a policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

applying in a dynamic domain described by a transition diagram

$\mathscr{P}$

applying in a dynamic domain described by a transition diagram

![]() $\mathscr{T}$

contains the sorts, statics, fluents, and actions of

$\mathscr{T}$

contains the sorts, statics, fluents, and actions of

![]() $\mathscr{T}$

; predicates

$\mathscr{T}$

; predicates

![]() $action$

,

$action$

,

![]() $static$

, and

$static$

, and

![]() $fluent$

; the sort

$fluent$

; the sort

![]() $step$

representing time steps; a predicate

$step$

representing time steps; a predicate

![]() $holds(s)$

for every static

$holds(s)$

for every static

![]() $s$

; and a predicate

$s$

; and a predicate

![]() $holds(f, i)$

for every fluent

$holds(f, i)$

for every fluent

![]() $f$

and time step

$f$

and time step

![]() $i$

.

$i$

.

To simplify the presentation of other components of the signature of

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

, we generalize the syntax of

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

, we generalize the syntax of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

rules of type (2a)–(2h) as:

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

rules of type (2a)–(2h) as:

which refers to both strict and defeasible, authorization and obligation rules from

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

. The square brackets “

$\mathscr{P}$

. The square brackets “

![]() $[\ ]$

” indicate an optional component of a rule (in this case the keyword “normally” denoting a defeasible rule). We use the term head of policy rule

$[\ ]$

” indicate an optional component of a rule (in this case the keyword “normally” denoting a defeasible rule). We use the term head of policy rule

![]() $r$

to refer to the

$r$

to refer to the

![]() $hd$

part in (3), where

$hd$

part in (3), where

![]() $hd \in HD$

,

$hd \in HD$

,

and

![]() $E$

is the set of all elementary actions in

$E$

is the set of all elementary actions in

![]() $\mathscr{T}$

. We refer to the

$\mathscr{T}$

. We refer to the

![]() $cond$

part of a policy rule

$cond$

part of a policy rule

![]() $r$

as its body. The signature

$r$

as its body. The signature

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

contains functions

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

contains functions

![]() $permitted$

and

$permitted$

and

![]() $obl$

, as well as a function

$obl$

, as well as a function

![]() $neg$

that encodes the negation “

$neg$

that encodes the negation “

![]() $\neg$

” when it is present in a policy rule. We introduce the following transformation lp that replaces the negation “

$\neg$

” when it is present in a policy rule. We introduce the following transformation lp that replaces the negation “

![]() $\neg$

” by the function

$\neg$

” by the function

![]() $neg$

:

$neg$

:

-

• If

$x$

is a static, fluent, or elementary action, then lp

$x$

is a static, fluent, or elementary action, then lp

$(x) = x$

and lp

$(x) = x$

and lp

$(\neg x) = neg(x)$

$(\neg x) = neg(x)$

-

• If

$e$

is an elementary action then:

$e$

is an elementary action then: \begin{align*} \begin{array}{l} \textbf {lp}(permitted(e)) = permitted(e)\\ \textbf {lp}(\neg permitted(e)) = neg(permitted(e))\\ \textbf {lp}(obl(e)) = obl(e)\\ \textbf {lp}(\neg obl(e)) = neg(obl(e))\\ \textbf {lp}(obl(\neg e)) = obl(neg(e))\\ \textbf {lp}(\neg obl(\neg e)) = neg(obl(neg(e))) \end{array} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \begin{array}{l} \textbf {lp}(permitted(e)) = permitted(e)\\ \textbf {lp}(\neg permitted(e)) = neg(permitted(e))\\ \textbf {lp}(obl(e)) = obl(e)\\ \textbf {lp}(\neg obl(e)) = neg(obl(e))\\ \textbf {lp}(obl(\neg e)) = obl(neg(e))\\ \textbf {lp}(\neg obl(\neg e)) = neg(obl(neg(e))) \end{array} \end{align*}

The signature of

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

also includes the following functions:

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

also includes the following functions:

-

•

$b(r)$

for every rule

$b(r)$

for every rule

$r$

to denote the condition

$r$

to denote the condition

$cond$

of

$cond$

of

$r$

(i.e., its body);

$r$

(i.e., its body); -

•

$ab(r)$

for each defeasible rule

$ab(r)$

for each defeasible rule

$r$

, representing an exception to its application (i.e., the rule being overridden by another defeasible rule, as specified by a prefer relation).

$r$

, representing an exception to its application (i.e., the rule being overridden by another defeasible rule, as specified by a prefer relation).

Additionally, the signature of

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

contains the predicates:

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

contains the predicates:

-

•

$rule(r)$

– where

$rule(r)$

– where

$r$

is a rule label (referred shortly as “rule” below)

$r$

is a rule label (referred shortly as “rule” below) -

•

$type(r, ty)$

– where

$type(r, ty)$

– where

$ty \in \{strict,$

defeasible, prefer

$ty \in \{strict,$

defeasible, prefer

$\}$

is the type of rule

$\}$

is the type of rule

$r$

$r$

-

•

$head(r, \textbf {lp}(hd))$

– to denote the head

$head(r, \textbf {lp}(hd))$

– to denote the head

$hd$

of rule

$hd$

of rule

$r$

$r$

-

•

$body(r, b(r))$

– to associate a rule

$body(r, b(r))$

– to associate a rule

$r$

with its body denoted by function

$r$

with its body denoted by function

$b(r)$

$b(r)$

-

•

$mbr(b(r), \textbf {lp}(l))$

– for every

$mbr(b(r), \textbf {lp}(l))$

– for every

$l$

in the condition

$l$

in the condition

$cond$

of rule

$cond$

of rule

$r$

, where the condition is represented by

$r$

, where the condition is represented by

$b(r)$

(

$b(r)$

(

$mbr$

stands for “member”)

$mbr$

stands for “member”) -

• prefer

$(d_1, d_2)$

– where

$(d_1, d_2)$

– where

$d_1$

and

$d_1$

and

$d_2$

are defeasible rule labels

$d_2$

are defeasible rule labels

To reason about which policies are applicable (i.e., active) at each time step, the signature of

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

also includes the following predicates:

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

also includes the following predicates:

-

•

$holds(x, i)$

– where

$holds(x, i)$

– where

$i$

is a time step and

$i$

is a time step and

$x$

may be a rule

$x$

may be a rule

$r$

; lp(hd) for the head

$r$

; lp(hd) for the head

$hd$

of a rule; the function

$hd$

of a rule; the function

$b(r)$

representing the body of a rule; or the function

$b(r)$

representing the body of a rule; or the function

$ab(r)$

for every defeasible rule

$ab(r)$

for every defeasible rule

$r$

$r$

-

•

$opp(r, \textbf {lp}(\overline {hd}))$

– where

$opp(r, \textbf {lp}(\overline {hd}))$

– where

$r$

is a defeasible rule and

$r$

is a defeasible rule and

$\overline {hd} \in HD$

(

$\overline {hd} \in HD$

(

$opp$

stands for “opposite”)

$opp$

stands for “opposite”)

The predicate

![]() $holds$

determines which policy rules are applicable, based on the truth values of statics and fluents in a state and the interactions among policy rules. Note that

$holds$

determines which policy rules are applicable, based on the truth values of statics and fluents in a state and the interactions among policy rules. Note that

![]() $holds$

with arity two is an overloaded predicate, also applying to pairs of fluents and time steps when it is used to describe states of a trajectory in

$holds$

with arity two is an overloaded predicate, also applying to pairs of fluents and time steps when it is used to describe states of a trajectory in

![]() $\mathscr{T}$

. The predicate

$\mathscr{T}$

. The predicate

![]() $opp(r, \textbf {lp}(\overline {hd}))$

indicates that

$opp(r, \textbf {lp}(\overline {hd}))$

indicates that

![]() $\overline {hd}$

is the logical complement of

$\overline {hd}$

is the logical complement of

![]() $r$

’s head

$r$

’s head

![]() $hd$

.

$hd$

.

The ASP translation of a policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

denoted by the ASP program

$\mathscr{P}$

denoted by the ASP program

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

consists of:

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

consists of:

-

1. A collection

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

of facts (or rules) representing the encoding of the policy rules in

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

of facts (or rules) representing the encoding of the policy rules in

$\mathscr{P}$

using the predicates

$\mathscr{P}$

using the predicates

$rule$

,

$rule$

,

$type$

,

$type$

,

$head$

,

$head$

,

$mbr$

, and prefer

$mbr$

, and prefer

-

2. The set of policy-independent ASP rules

$\mathscr{R}$

shown below in (4), which define predicates

$\mathscr{R}$

shown below in (4), which define predicates

$holds(x, i)$

and

$holds(x, i)$

and

$opp(r, \textbf {lp}(\overline {hd}))$

. In these ASP rules, variable

$opp(r, \textbf {lp}(\overline {hd}))$

. In these ASP rules, variable

$F$

represents a fluent,

$F$

represents a fluent,

$S$

a static,

$S$

a static,

$E$

an elementary action,

$E$

an elementary action,

$H$

a happening (i.e., an elementary action or its negation), and

$H$

a happening (i.e., an elementary action or its negation), and

$I$

a time step.(4)

$I$

a time step.(4) \begin{align} \begin{array}{lll} body(R, b(R)) & \leftarrow & rule(R)\\ holds(R, I) & \leftarrow & type(R, strict), holds(b(R), I)\\ holds(R, I) & \leftarrow & type(R, defeasible), holds(b(R), I), \\ & & opp(R, O), \mbox{not } holds(O, I), \mbox{not } holds(ab(R), I)\\ \neg holds (B, I) & \leftarrow & body(R, B), mbr(B, F), fluent(F), \neg holds(F, I).\\ \neg holds (B, I) & \leftarrow & body(R, B), mbr(B, neg(F)), fluent(F), holds(F, I).\\ \neg holds (B, I) & \leftarrow & body(R, B), mbr(B, S), static(S), \neg holds(S), step(I).\\ \neg holds (B, I) & \leftarrow & body(R, B), mbr(B, neg(S)), static(S), holds(S), step(I).\\ holds(B, I) & \leftarrow & body(R, B), not \neg holds(B, I), step(I).\\holds(ab(R_2), I) & \leftarrow & {{prefer}}(R_1, R_2), holds(b(R_1), I) \\ holds(Hd, I) & \leftarrow & holds(R, I), head(R, Hd)\\ opp(R, permitted(E)) & \leftarrow & head(R, neg(permitted(E)))\\ opp(R, neg(permitted(E))) & \leftarrow & head(R, permitted(E))\\ opp(R, obl(H)) & \leftarrow & head(R, neg( obl(H)))\\ opp(R, neg(obl(H))) & \leftarrow & head(R, obl(H)) \end{array} \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{array}{lll} body(R, b(R)) & \leftarrow & rule(R)\\ holds(R, I) & \leftarrow & type(R, strict), holds(b(R), I)\\ holds(R, I) & \leftarrow & type(R, defeasible), holds(b(R), I), \\ & & opp(R, O), \mbox{not } holds(O, I), \mbox{not } holds(ab(R), I)\\ \neg holds (B, I) & \leftarrow & body(R, B), mbr(B, F), fluent(F), \neg holds(F, I).\\ \neg holds (B, I) & \leftarrow & body(R, B), mbr(B, neg(F)), fluent(F), holds(F, I).\\ \neg holds (B, I) & \leftarrow & body(R, B), mbr(B, S), static(S), \neg holds(S), step(I).\\ \neg holds (B, I) & \leftarrow & body(R, B), mbr(B, neg(S)), static(S), holds(S), step(I).\\ holds(B, I) & \leftarrow & body(R, B), not \neg holds(B, I), step(I).\\holds(ab(R_2), I) & \leftarrow & {{prefer}}(R_1, R_2), holds(b(R_1), I) \\ holds(Hd, I) & \leftarrow & holds(R, I), head(R, Hd)\\ opp(R, permitted(E)) & \leftarrow & head(R, neg(permitted(E)))\\ opp(R, neg(permitted(E))) & \leftarrow & head(R, permitted(E))\\ opp(R, obl(H)) & \leftarrow & head(R, neg( obl(H)))\\ opp(R, neg(obl(H))) & \leftarrow & head(R, obl(H)) \end{array} \end{align}

Thus, for a policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

,

$\mathscr{P}$

,

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

=

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

=

![]() $\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

![]() $\cup$

$\cup$

![]() $\mathscr{R}$

.

$\mathscr{R}$

.

Example 1 (ASP Encoding

![]() $\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

of a Policy

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

of a Policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

). Let’s give an example of the encoding

$\mathscr{P}$

). Let’s give an example of the encoding

![]() $\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

of a policy

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

of a policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

consisting of a unique policy rule:

$\mathscr{P}$

consisting of a unique policy rule:

where 1 refers to location 1 in Figure 1,

![]() $stop(1)$

is an action, and

$stop(1)$

is an action, and

![]() $pedes$

$pedes$

![]() $trians\_are\_crossing(1)$

is a fluent.

$trians\_are\_crossing(1)$

is a fluent.

![]() $\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

for this policy will consist of the ASP facts:

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

for this policy will consist of the ASP facts:

\begin{align*} \begin{array}{l} rule(r6(1)).\\ type(r6(1),\ strict).\\ head(r6(1),\ obl(stop(1))).\\ mbr(b(r6(1)),\ pedestrians\_are\_crossing(1)). \end{array} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \begin{array}{l} rule(r6(1)).\\ type(r6(1),\ strict).\\ head(r6(1),\ obl(stop(1))).\\ mbr(b(r6(1)),\ pedestrians\_are\_crossing(1)). \end{array} \end{align*}

We discuss next the role of the set of rules

![]() $\mathscr{R}$

given in (4). For a given trajectory in the system description to which policy

$\mathscr{R}$

given in (4). For a given trajectory in the system description to which policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

belongs, if

$\mathscr{P}$

belongs, if

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

is categorical, atoms of the form

$\mathscr{P}$

is categorical, atoms of the form

![]() $holds(\textbf {lp}(hd), i)$

indicate which literals

$holds(\textbf {lp}(hd), i)$

indicate which literals

![]() $hd$

from

$hd$

from

![]() $HD$

(i.e., literals formed by predicates permitted and

$HD$

(i.e., literals formed by predicates permitted and

![]() $obl$

) hold at time step

$obl$

) hold at time step

![]() $i$

. Atoms of the form

$i$

. Atoms of the form

![]() $holds(r, i)$

, where

$holds(r, i)$

, where

![]() $r$

is a rule and

$r$

is a rule and

![]() $i$

is a time step, indicate which rules are applicable at each step. If a rule is applicable, the agent’s actions must be checked for compliance. Strict rules apply in all states where their condition (i.e., body) is satisfied, but not in states that do not satisfy it – see the second rule in (4). For instance, in the sample policy from Figure 2, rule 6 applies only if pedestrians are crossing at the location where the agent is currently situated; crossings at other locations or the absence of pedestrians are irrelevant, and the rule would not apply in those situations. Strict rules with satisfied bodies cannot be rendered inapplicable by rules with the opposite (complement) head. However, a defeasible rule may be overridden by another rule, rendering it inapplicable in a state that would otherwise satisfy its condition – see the third rule in (4). The part “

$i$

is a time step, indicate which rules are applicable at each step. If a rule is applicable, the agent’s actions must be checked for compliance. Strict rules apply in all states where their condition (i.e., body) is satisfied, but not in states that do not satisfy it – see the second rule in (4). For instance, in the sample policy from Figure 2, rule 6 applies only if pedestrians are crossing at the location where the agent is currently situated; crossings at other locations or the absence of pedestrians are irrelevant, and the rule would not apply in those situations. Strict rules with satisfied bodies cannot be rendered inapplicable by rules with the opposite (complement) head. However, a defeasible rule may be overridden by another rule, rendering it inapplicable in a state that would otherwise satisfy its condition – see the third rule in (4). The part “

![]() $opp(R, O),\ \mbox{not } holds(O, I)$

” in this ASP rule specifies that an applicable (strict) rule with the opposite head makes the defeasible rule

$opp(R, O),\ \mbox{not } holds(O, I)$

” in this ASP rule specifies that an applicable (strict) rule with the opposite head makes the defeasible rule

![]() $R$

inapplicable. The part “

$R$

inapplicable. The part “

![]() $\mbox{not } holds(ab(R), I)$

” indicates that a preference relationship can render a defeasible rule

$\mbox{not } holds(ab(R), I)$

” indicates that a preference relationship can render a defeasible rule

![]() $R$

inapplicable if a more preferred defeasible rule applies in the state. This is encoded as an exception to the default case through the use of

$R$

inapplicable if a more preferred defeasible rule applies in the state. This is encoded as an exception to the default case through the use of

![]() $ab(R)$

, following the standard treatment of defaults (see the ninth rule in (4)). Ultimately, only the policy rules applicable at a given time step

$ab(R)$

, following the standard treatment of defaults (see the ninth rule in (4)). Ultimately, only the policy rules applicable at a given time step

![]() $i$

need to be checked for the agent’s compliance at that step.

$i$

need to be checked for the agent’s compliance at that step.

The reified translation

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

of

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

into ASP preserves the intended semantics of

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

into ASP preserves the intended semantics of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

. Proposition 1 discusses the correspondence between the original ASP translation of

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

. Proposition 1 discusses the correspondence between the original ASP translation of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

and the reified translation

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

and the reified translation

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

introduced here for

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

introduced here for

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

. To establish this correspondence, we first present the ASP translation of a trajectory, which will be referenced in the proposition. If

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

. To establish this correspondence, we first present the ASP translation of a trajectory, which will be referenced in the proposition. If

![]() $t = \langle \sigma _0, ca_0, \sigma _1, ca_1, \dots , ca_n, \sigma _{n+1} \rangle$

is a trajectory in transition diagram

$t = \langle \sigma _0, ca_0, \sigma _1, ca_1, \dots , ca_n, \sigma _{n+1} \rangle$

is a trajectory in transition diagram

![]() $\mathscr{T}$

, where

$\mathscr{T}$

, where

![]() $\sigma _0, \dots , \sigma _{n+1}$

are states and

$\sigma _0, \dots , \sigma _{n+1}$

are states and

![]() $ca_0, \dots , ca_n$

are actions, then the ASP encoding of

$ca_0, \dots , ca_n$

are actions, then the ASP encoding of

![]() $t$

denoted by

$t$

denoted by

![]() $\mathscr{E}(t)$

is defined as follows:

$\mathscr{E}(t)$

is defined as follows:

\begin{align*} \begin{array}{lll} \mathscr{E}(t) & =_{def} & \{holds(f, i) : f \mbox{ is a fluent},\ f \in \sigma _i,\ 0 \leq i \leq n+1\}\ \cup \\ & & \{\neg holds(f, i) : f \mbox{ is a fluent,}\ \neg f \in \sigma _i\,\ 0 \leq i \leq n+1\}\ \cup \\ & & \{holds(s) : s \mbox{ is a static},\ s \in \sigma _i,\ 0 \leq i \leq n+1\}\ \cup \\ & & \{\neg holds(s) : s \mbox{ is a static},\ \neg s \in \sigma _i,\ 0 \leq i \leq n+1\}\ \cup \\ & & \{occurs(e, i) : e \mbox{ is an elementary action}, \ e \in ca_i, \ 0 \leq i \leq n \} \end{array} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \begin{array}{lll} \mathscr{E}(t) & =_{def} & \{holds(f, i) : f \mbox{ is a fluent},\ f \in \sigma _i,\ 0 \leq i \leq n+1\}\ \cup \\ & & \{\neg holds(f, i) : f \mbox{ is a fluent,}\ \neg f \in \sigma _i\,\ 0 \leq i \leq n+1\}\ \cup \\ & & \{holds(s) : s \mbox{ is a static},\ s \in \sigma _i,\ 0 \leq i \leq n+1\}\ \cup \\ & & \{\neg holds(s) : s \mbox{ is a static},\ \neg s \in \sigma _i,\ 0 \leq i \leq n+1\}\ \cup \\ & & \{occurs(e, i) : e \mbox{ is an elementary action}, \ e \in ca_i, \ 0 \leq i \leq n \} \end{array} \end{align*}

Proposition 1.

Let

![]() $\langle \sigma _i, ca_i \rangle$

be an event in a trajectory

$\langle \sigma _i, ca_i \rangle$

be an event in a trajectory

![]() $t = \langle \sigma _0, ca_0, \sigma _1, ca_1, \dots , ca_n, \sigma _{n+1} \rangle$

in the transition diagram

$t = \langle \sigma _0, ca_0, \sigma _1, ca_1, \dots , ca_n, \sigma _{n+1} \rangle$

in the transition diagram

![]() $\mathscr{T}$

. For every

$\mathscr{T}$

. For every

![]() $i \in \{0, \dots , n\}$

, let

$i \in \{0, \dots , n\}$

, let

![]() $\mathscr{A}_i$

be the collection of answer sets of

$\mathscr{A}_i$

be the collection of answer sets of

![]() $lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma _i)$

and let

$lp(\mathscr{P}, \sigma _i)$

and let

![]() $\mathscr{B}_i$

be the collection of answer sets of

$\mathscr{B}_i$

be the collection of answer sets of

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

![]() $\cup$

$\cup$

![]() $\mathscr{E}$

(

$\mathscr{E}$

(

![]() $\langle \sigma _i, ca_i \rangle$

).

$\langle \sigma _i, ca_i \rangle$

).

There is a one-to-one correspondence

![]() $map : \mathscr{A}_i \rightarrow \mathscr{B}_i$

such that if

$map : \mathscr{A}_i \rightarrow \mathscr{B}_i$

such that if

![]() $map (A) = B$

then for every

$map (A) = B$

then for every

![]() $hd \in HD$

where

$hd \in HD$

where

![]() $\textbf {lp}(hd) \in A$

, we have that

$\textbf {lp}(hd) \in A$

, we have that

![]() $\exists holds(\textbf {lp}(hd), i) \in B$

.

$\exists holds(\textbf {lp}(hd), i) \in B$

.

Challenges: The

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

translation described above presents specific challenges when it comes to automating the translation process. The description of

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

translation described above presents specific challenges when it comes to automating the translation process. The description of

![]() $\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

above assumes that rule labels are ground terms, as in Example 1. In practical applications, it is more common for rule labels to contain variables, thus representing a schema for a collection of ground rule labels. If that is the case, then

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

above assumes that rule labels are ground terms, as in Example 1. In practical applications, it is more common for rule labels to contain variables, thus representing a schema for a collection of ground rule labels. If that is the case, then

![]() $\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

would not contain facts, but rather a collection of rules qualifying the variables.

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

would not contain facts, but rather a collection of rules qualifying the variables.

Let’s consider rule 6 from Figure 2 stating that there is a strict obligation to stop when pedestrians are crossing. Assuming that the dynamic domain includes action

![]() $stop(l)$

and fluent

$stop(l)$

and fluent

![]() $pedestrians\_are\_crossing(l)$

where

$pedestrians\_are\_crossing(l)$

where

![]() $l$

is a location, the corresponding

$l$

is a location, the corresponding

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

rule would look as follows:

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

rule would look as follows:

Note that the rule label,

![]() $r6(L)$

is not ground. Hence the representation of this rule in

$r6(L)$

is not ground. Hence the representation of this rule in

![]() $\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

would be as follows:

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

would be as follows:

\begin{align*} \begin{array}{l} rule(r6(L)) \ \leftarrow \ action(stop(L))\\ type(r6(L), strict) \ \leftarrow \ rule(r6(L))\\ head(r6(L), obl(stop(L))) \ \leftarrow \ rule(r6(L))\\ mbr(b(r6(L)), pedestrians\_are\_crossing(L)) \ \leftarrow \ rule(r6(L)) \end{array} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \begin{array}{l} rule(r6(L)) \ \leftarrow \ action(stop(L))\\ type(r6(L), strict) \ \leftarrow \ rule(r6(L))\\ head(r6(L), obl(stop(L))) \ \leftarrow \ rule(r6(L))\\ mbr(b(r6(L)), pedestrians\_are\_crossing(L)) \ \leftarrow \ rule(r6(L)) \end{array} \end{align*}

where the body “

![]() $action(stop(L))$

” of the first rule above is derived from the name of the action referenced in policy rule 6.

$action(stop(L))$

” of the first rule above is derived from the name of the action referenced in policy rule 6.

Another challenge posed by the reified translation of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

into ASP is dealing with arithmetic comparisons. To illustrate this, let’s consider rule 1 from Figure 2. The label of the

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

into ASP is dealing with arithmetic comparisons. To illustrate this, let’s consider rule 1 from Figure 2. The label of the

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

statement for this policy rule,

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

statement for this policy rule,

![]() $r1(L_1, L_2, S, S_1)$

, needs to keep track of four variables:

$r1(L_1, L_2, S, S_1)$

, needs to keep track of four variables:

![]() $L_1, L_2$

, and

$L_1, L_2$

, and

![]() $S$

associated with the

$S$

associated with the

![]() $drive$

action from location

$drive$

action from location

![]() $L_1$

to location

$L_1$

to location

![]() $L_2$

at speed

$L_2$

at speed

![]() $S$

; and the speed limit

$S$

; and the speed limit

![]() $S_1$

for the road section from

$S_1$

for the road section from

![]() $L_1$

to

$L_1$

to

![]() $L_2$

:

$L_2$

:

The ASP encoding of rule 1 from Figure 2 would contain a statement:

Since this syntax is not allowed by ASP solvers, we replace arithmetic comparisons with our own, for example

![]() $gt$

for “

$gt$

for “

![]() $\gt$

”, as in:

$\gt$

”, as in:

and define these new symbols (e.g.,

![]() $gt, gte$

) via ASP rules added to the

$gt, gte$

) via ASP rules added to the

![]() $\mathscr{R}$

part of

$\mathscr{R}$

part of

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

, which corresponds to policy-independent ASP rules (see (4)).

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

, which corresponds to policy-independent ASP rules (see (4)).

The process of obtaining these translations is described further in Section 4.3. But first, let’s extend

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

with means for representing penalties.

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

with means for representing penalties.

4.2 Extending

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

with penalties:

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

with penalties:

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{P}$

$\mathscr{P}$

In our framework we extend the

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

syntax (i.e., statements of type (2a)-(2i)) by a new type of statement for penalties:

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

syntax (i.e., statements of type (2a)-(2i)) by a new type of statement for penalties:

where r is the label of the prohibition or obligation rule for which the penalty is specified, p stands for the number of penalty points imposed if the policy rule r applies and the agent is noncompliant with it, and

![]() $cond_p$

is a collection of static literals. The “

$cond_p$

is a collection of static literals. The “

![]() $\textbf {if}\ cond_p$

” part is omitted if

$\textbf {if}\ cond_p$

” part is omitted if

![]() $cond_p$

is empty. We denote this extension of

$cond_p$

is empty. We denote this extension of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

as

$\mathscr{AOPL}^{\prime}$

as

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

.

$\mathscr{P}$

.

For instance, the penalty associated with rule 6 from Figure 2 is encoded in

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

as:

$\mathscr{P}$

as:

This says that the agent will incur a 3-point penalty at each time step in which this rule applies and the agent’s action is noncompliant with it.

Multiple penalty values may be associated with the same rule, reflecting different gravity levels, as in rule 1 of Figure 2. If the rule applies at a given time step and the agent’s action is noncompliant, the agent incurs one of the specified penalties according to the gravity level. The various levels of penalties assigned to rule 1 are stated in

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

as:

$\mathscr{P}$

as:

\begin{align} \begin{array}{l@{\quad}l@{\quad}l} penalty(r1(L_1, L_2, S, S_1),1) & \textbf {if} & S - S_1 \lt 10\\ penalty(r1(L_1, L_2, S, S_1),2) & \textbf {if} & S - S_1 \gt = 10,\ S - S1 \lt 20\\ penalty(r1(L_1, L_2, S, S_1),3) & \textbf {if} & S - S_1 \gt = 20 \end{array} \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{array}{l@{\quad}l@{\quad}l} penalty(r1(L_1, L_2, S, S_1),1) & \textbf {if} & S - S_1 \lt 10\\ penalty(r1(L_1, L_2, S, S_1),2) & \textbf {if} & S - S_1 \gt = 10,\ S - S1 \lt 20\\ penalty(r1(L_1, L_2, S, S_1),3) & \textbf {if} & S - S_1 \gt = 20 \end{array} \end{align}

Recall from the previous section that the semantics of the policy language are given in terms of a translation into ASP. We need to expand this translation to cover the new type of statement in (7). Given a policy

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

, recall that

$\mathscr{P}$

, recall that

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

=

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

=

![]() $\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

![]() $\cup$

$\cup$

![]() $\mathscr{R}$

, where

$\mathscr{R}$

, where

![]() $\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

is the encoding of the statements in

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

is the encoding of the statements in

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

and

$\mathscr{P}$

and

![]() $\mathscr{R}$

is the set of policy-independent rules described in (4). We expand the

$\mathscr{R}$

is the set of policy-independent rules described in (4). We expand the

![]() $\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

part of

$\mathscr{E}(\mathscr{P})$

part of

![]() $rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

with the ASP translation of the new type of

$rei\_lp(\mathscr{P})$

with the ASP translation of the new type of

![]() $\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

$\mathscr{AOPL}$

-

![]() $\mathscr{P}$

statement (7) for penalties:

$\mathscr{P}$

statement (7) for penalties:

The rules in

![]() $\mathscr{R}$

remain as they are. As an example, statement (8) is translated into ASP as:

$\mathscr{R}$

remain as they are. As an example, statement (8) is translated into ASP as:

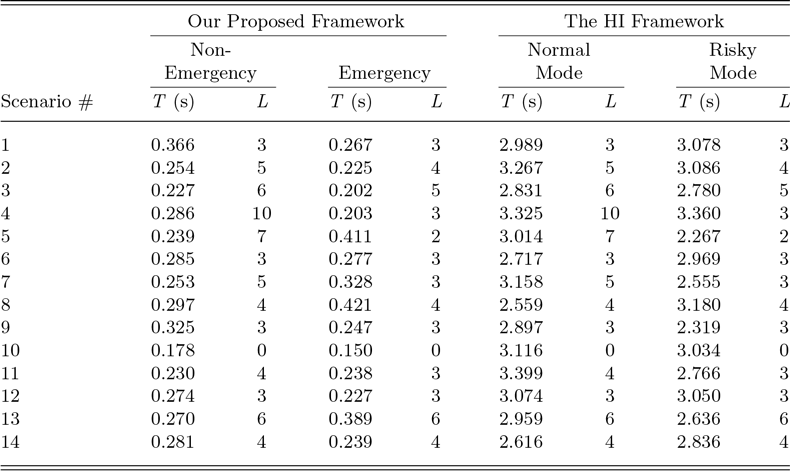

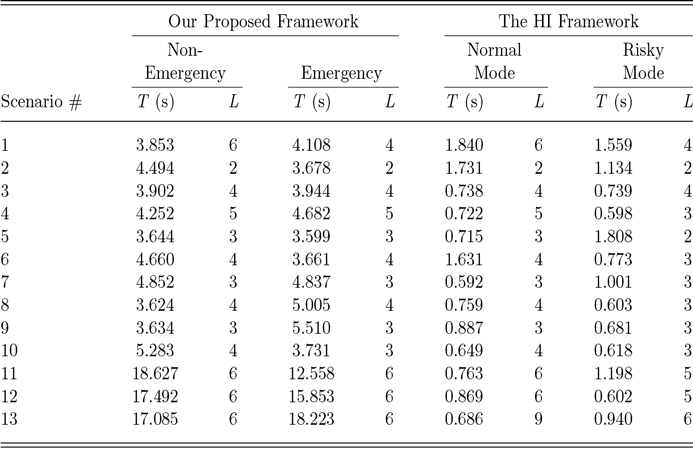

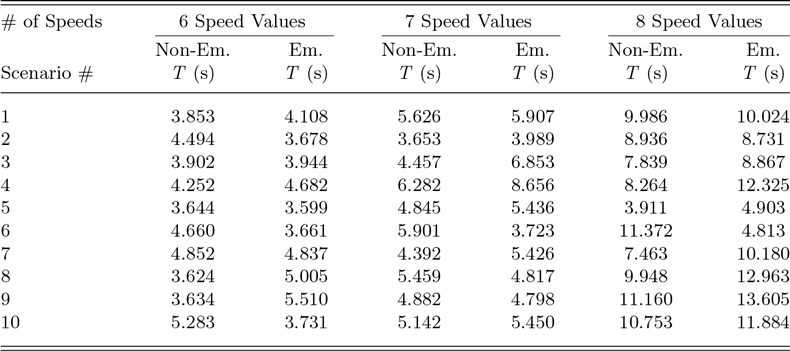

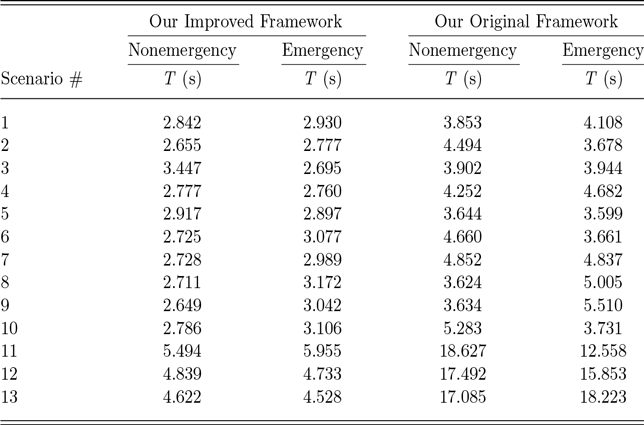

Penalty statements (9) are translated as: