1 Introduction

Throughout the paper,

![]() $\Bbbk $

stands for a field. Consider a polynomial ring

$\Bbbk $

stands for a field. Consider a polynomial ring

![]() $S=\Bbbk [x_1,\dots ,x_n]$

standard graded by

$S=\Bbbk [x_1,\dots ,x_n]$

standard graded by

![]() $\deg (x_i)=1$

for each i, and let I be a graded ideal. The graded

$\deg (x_i)=1$

for each i, and let I be a graded ideal. The graded

![]() $\Bbbk $

-algebra

$\Bbbk $

-algebra

![]() $Q=S/I$

is

Koszul

if

$Q=S/I$

is

Koszul

if

![]() $\Bbbk $

has a linear free resolution over Q, that is, the entries in the matrices of the differential in the resolution are linear forms; in this case, we also say that the ideal I is

Koszul

. Koszul algebras were formally defined by Priddy [Reference Priddy37] (who considered a more general situation which includes the noncommutative case as well). They appear in many areas of algebra, geometry, and topology. Two of their exceptionally nice properties are that the minimal free resolution of

$\Bbbk $

has a linear free resolution over Q, that is, the entries in the matrices of the differential in the resolution are linear forms; in this case, we also say that the ideal I is

Koszul

. Koszul algebras were formally defined by Priddy [Reference Priddy37] (who considered a more general situation which includes the noncommutative case as well). They appear in many areas of algebra, geometry, and topology. Two of their exceptionally nice properties are that the minimal free resolution of

![]() $\Bbbk $

can be explicitly described as the generalized Koszul complex (see [Reference McCullough and Peeva28, 8.12]), and there is an elegant formula relating the Hilbert function of Q and the Poincaré series of

$\Bbbk $

can be explicitly described as the generalized Koszul complex (see [Reference McCullough and Peeva28, 8.12]), and there is an elegant formula relating the Hilbert function of Q and the Poincaré series of

![]() $\Bbbk $

(which is the generating function of the minimal free resolution of

$\Bbbk $

(which is the generating function of the minimal free resolution of

![]() $\Bbbk $

over Q), see [Reference McCullough and Peeva28, 8.5]. Another important property of commutative Koszul algebras is that they are the algebras over which every finitely generated module has finite regularity [Reference Avramov and Eisenbud1, Reference Avramov and Peeva2]. The papers [Reference Conca14], [Reference Conca, De Negri and Evelina Rossi12], [Reference Fröberg23], and [Reference Polishchuk and Positselski36] provide excellent overviews of Koszul algebras. It is well known that if I is Koszul then it is generated by quadrics; in this case, we say that Q and I are

quadratic

.

$\Bbbk $

over Q), see [Reference McCullough and Peeva28, 8.5]. Another important property of commutative Koszul algebras is that they are the algebras over which every finitely generated module has finite regularity [Reference Avramov and Eisenbud1, Reference Avramov and Peeva2]. The papers [Reference Conca14], [Reference Conca, De Negri and Evelina Rossi12], [Reference Fröberg23], and [Reference Polishchuk and Positselski36] provide excellent overviews of Koszul algebras. It is well known that if I is Koszul then it is generated by quadrics; in this case, we say that Q and I are

quadratic

.

The Koszul property has been studied for quadratic graded

![]() $\Bbbk $

-algebras coming from graphs. Let G be a graph on vertex set

$\Bbbk $

-algebras coming from graphs. Let G be a graph on vertex set

![]() $[n] = \{1, 2, \dots , n\}$

. Throughout this paper, all graphs are assumed to be simple, that is, with no loops and no double edges. There are various constructions that produce a quadratic graded

$[n] = \{1, 2, \dots , n\}$

. Throughout this paper, all graphs are assumed to be simple, that is, with no loops and no double edges. There are various constructions that produce a quadratic graded

![]() $\Bbbk $

-algebra starting from G; we discuss some of them: The monomial edge ideal

$\Bbbk $

-algebra starting from G; we discuss some of them: The monomial edge ideal

![]() $N_G=\big (x_ix_j\,|\, \{i,j\} \ \text { is an edge in } G\,\big )$

is generated by quadratic monomials, and it is always Koszul. One may consider the toric edge ring

$N_G=\big (x_ix_j\,|\, \{i,j\} \ \text { is an edge in } G\,\big )$

is generated by quadratic monomials, and it is always Koszul. One may consider the toric edge ring

![]() $A_G = \Bbbk [x_ix_j\,|\, \{i,j\} \ \text { is an edge in } G\,]$

, for which Hibi and Ohsugi provide a characterization when

$A_G = \Bbbk [x_ix_j\,|\, \{i,j\} \ \text { is an edge in } G\,]$

, for which Hibi and Ohsugi provide a characterization when

![]() $A_G$

is quadratic. Furthermore, if the graph G is bipartite, they prove in [Reference Ohsugi and Hibi32] that

$A_G$

is quadratic. Furthermore, if the graph G is bipartite, they prove in [Reference Ohsugi and Hibi32] that

![]() $A_G$

is Koszul if and only if it is quadratic, if and only if there is a quadratic Gröbner basis.

$A_G$

is Koszul if and only if it is quadratic, if and only if there is a quadratic Gröbner basis.

We focus on the concept of binomial edge ideal associated with a graph G, which generalizes the classical concept of determinantal ideal generated by the

![]() $2$

-minors of a

$2$

-minors of a

![]() $(2\times n)$

-matrix of indeterminates.

$(2\times n)$

-matrix of indeterminates.

Definition 1.1. The

binomial edge ideal

![]() $J_G$

is the ideal

$J_G$

is the ideal

in the polynomial ring

We set

![]() $R_G = S_G/J_G$

. We will use this notation throughout the paper.

$R_G = S_G/J_G$

. We will use this notation throughout the paper.

Binomial edge ideals were first introduced in [Reference Herzog, Hibi, Hreinsdóttir, Kahle and Rauh25] and independently in [Reference Ohtani30] as a generalization of the ideals of minors that appear in algebraic statistics; see [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, Section 4]. Binomial edge ideals also generalize ladder determinantal ideals and ideals of adjacent minors studied in [Reference Conca13]. They have been studied extensively, and the book [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26] provides an overview of their properties.

It turns out that the Koszul property of

![]() $J_G$

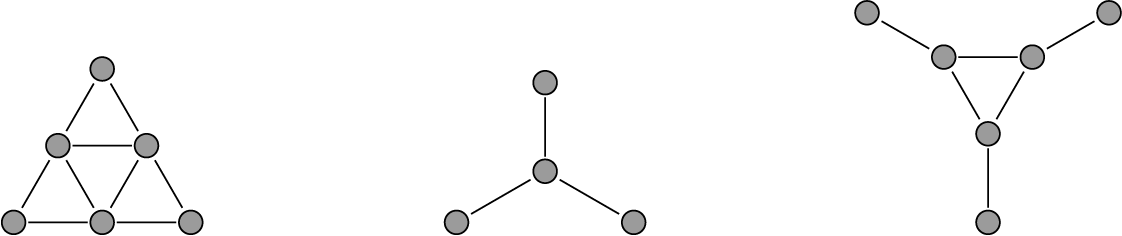

is related to three special graphs, defined in Figure 1: the tent, the claw, and the net.

$J_G$

is related to three special graphs, defined in Figure 1: the tent, the claw, and the net.

Figure 1 The tent (left), claw (center), and net (right) graphs.

The study of the Koszul property of binomial edge ideals was launched by Ene, Herzog, and Hibi in 2014 in [Reference Ene, Herzog and Hibi21]. They showed that if the binomial edge ideal

![]() $J_G$

is Koszul, then the graph G is chordal [Reference Ene, Herzog and Hibi21, Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26], that is, G does not contain an induced cycle of length greater than three. Furthermore, they found that the binomial edge ideal of the claw and the binomial edge ideal of the tent are not Koszul. The ideal

$J_G$

is Koszul, then the graph G is chordal [Reference Ene, Herzog and Hibi21, Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26], that is, G does not contain an induced cycle of length greater than three. Furthermore, they found that the binomial edge ideal of the claw and the binomial edge ideal of the tent are not Koszul. The ideal

![]() $J_G$

is multigraded, and this implies that if

$J_G$

is multigraded, and this implies that if

![]() $J_G$

is Koszul, then

$J_G$

is Koszul, then

![]() $J_F$

is Koszul for any induced subgraph F of G, by [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, 7.46]. So, if

$J_F$

is Koszul for any induced subgraph F of G, by [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, 7.46]. So, if

![]() $J_G$

is Koszul, then G is chordal, claw-free, and tent-free. The rather sparse known results on Koszulness of binomial edge ideals are surveyed in the book [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26].

$J_G$

is Koszul, then G is chordal, claw-free, and tent-free. The rather sparse known results on Koszulness of binomial edge ideals are surveyed in the book [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26].

The main result in our paper is that, in Section 2, we prove the following characterization of Koszulness:

Theorem 1.2. The binomial edge ideal

![]() $J_G$

is Koszul if and only if the graph G is chordal, claw-free, and tent-free.

$J_G$

is Koszul if and only if the graph G is chordal, claw-free, and tent-free.

We also show in Corollary 2.4 that the above conditions are equivalent to G being strongly chordal and claw-free.

The usual technique for establishing that an ideal is Koszul is to show that it has a quadratic Gröbner basis. Proving Koszulness in the absence of a quadratic Gröbner basis is very challenging, and there are very few such results known. For example, Caviglia and Conca study the Koszul property of projections of the Veronese cubic surface in [Reference Caviglia and Conca11], and Hibi and Ohsugi provide such toric rings in [Reference Ohsugi and Hibi33]. It is known that the binomial edge ideal

![]() $J_G$

has a quadratic Gröbner basis if and only if the graph G is closed by [Reference Herzog, Hibi, Hreinsdóttir, Kahle and Rauh25, 1.1] and [Reference Crupi and Rinaldo16, 3.4]. In this case,

$J_G$

has a quadratic Gröbner basis if and only if the graph G is closed by [Reference Herzog, Hibi, Hreinsdóttir, Kahle and Rauh25, 1.1] and [Reference Crupi and Rinaldo16, 3.4]. In this case,

![]() $J_G$

has the very rare property that its graded Betti numbers coincide with those of its lex initial ideal [Reference Peeva35]. By [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, 7.10], G is closed if and only if it is chordal, claw-free, tent-free, and net-free. Thus, any Koszul binomial edge ideal for which G contains a net as an induced subgraph does not have a quadratic Gröbner basis. There are many such examples, starting with the net itself. This is in stark contrast with the binomial edge ideals of a pair of graphs, where the two notions are equivalent by [Reference Baskoroputro, Ene and Ion3].

$J_G$

has the very rare property that its graded Betti numbers coincide with those of its lex initial ideal [Reference Peeva35]. By [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, 7.10], G is closed if and only if it is chordal, claw-free, tent-free, and net-free. Thus, any Koszul binomial edge ideal for which G contains a net as an induced subgraph does not have a quadratic Gröbner basis. There are many such examples, starting with the net itself. This is in stark contrast with the binomial edge ideals of a pair of graphs, where the two notions are equivalent by [Reference Baskoroputro, Ene and Ion3].

We prove the “if” implication of Theorem 2 in Section 2. The key idea in our proof is that such graphs are strongly chordal and claw-free, which yields orders on both the vertices and edges with special properties. Our proof is an inductive argument based on the properties of this class of graphs. Although the “only if” implication was already established by Ene, Herzog, and Hibi [Reference Ene, Herzog and Hibi21], [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, Section 7.4.1], we give a self-contained, characteristic-free proof that does not rely on computer algebra computations in Section 4. In Section 5, we characterize strongly chordal, claw-free graphs with small clique number and show that this characterization does not generalize to graphs with higher clique numbers.

2 Koszul binomial edge ideals

The aim of this section is to prove the sufficient condition in our main result Theorem 1.2:

Theorem 2.1. If a simple graph G is chordal, claw-free, and tent-free, then the binomial edge ideal

![]() $J_G$

is Koszul.

$J_G$

is Koszul.

We first develop the graph machinery necessary. We refer the reader to [Reference West39] and [Reference Brandstädt, Bang Le and Spinrad9] for more on graph theory. Throughout, we assume that G is a finite simple graph. Let

![]() $G = (V(G),E(G))$

have a set of vertices

$G = (V(G),E(G))$

have a set of vertices

![]() $V(G)$

, and a set of edges

$V(G)$

, and a set of edges

![]() $E(G)$

. For simplicity, we may write

$E(G)$

. For simplicity, we may write

![]() $\{i,j\}\in G$

meaning

$\{i,j\}\in G$

meaning

![]() $\{i,j\}\in E(G)$

, or may write

$\{i,j\}\in E(G)$

, or may write

![]() $ij$

to denote the edge

$ij$

to denote the edge

![]() $\{i,j\}$

. The set of

neighbors

of a vertex i in G is the set

$\{i,j\}$

. The set of

neighbors

of a vertex i in G is the set

![]() $N(i)$

of all vertices j such that

$N(i)$

of all vertices j such that

![]() $\{i, j\}$

is an edge of G. The set

$\{i, j\}$

is an edge of G. The set

![]() $N[i] = N(i) \cup \{i\}$

is called the

closed neighborhood

of i. A subgraph H of G is

induced

if for any

$N[i] = N(i) \cup \{i\}$

is called the

closed neighborhood

of i. A subgraph H of G is

induced

if for any

![]() $v_i,v_j \in V(H)$

, if

$v_i,v_j \in V(H)$

, if

![]() $v_iv_j \in E(G)$

then

$v_iv_j \in E(G)$

then

![]() $v_iv_j \in E(H)$

. The complete graph contains all possible edges between distinct vertices. A

cycle

graph

$v_iv_j \in E(H)$

. The complete graph contains all possible edges between distinct vertices. A

cycle

graph

![]() $C_n$

of length n has n vertices

$C_n$

of length n has n vertices

![]() $v_1,\ldots ,v_n$

and edges

$v_1,\ldots ,v_n$

and edges

![]() $v_iv_{i+1}$

for

$v_iv_{i+1}$

for

![]() $1 \le i \le n$

, where we identify

$1 \le i \le n$

, where we identify

![]() $v_{n+1}$

with

$v_{n+1}$

with

![]() $v_1$

.

$v_1$

.

A chordal graph is one with no induced cycles of length at least four. There are several characterizations of chordal graphs; we highlight two characterizations involving vertex orderings and special types of vertices.

A

perfect elimination order

for a graph G is an ordering

![]() $v_1, \dots , v_n$

of its vertices such that whenever

$v_1, \dots , v_n$

of its vertices such that whenever

![]() $v_iv_j, v_iv_k \in E(G)$

and

$v_iv_j, v_iv_k \in E(G)$

and

![]() $i < j, k$

, we have that

$i < j, k$

, we have that

![]() $v_jv_k \in E(G)$

. We say that v is a

simplicial vertex

of G if

$v_jv_k \in E(G)$

. We say that v is a

simplicial vertex

of G if

![]() $N[v]$

is a clique, that is, the induced subgraph of G on the set

$N[v]$

is a clique, that is, the induced subgraph of G on the set

![]() $N[v]$

is a complete graph. In that case,

$N[v]$

is a complete graph. In that case,

![]() $N[v]$

is a maximal clique of G. If G has a perfect elimination order

$N[v]$

is a maximal clique of G. If G has a perfect elimination order

![]() $v_1, \dots , v_n$

, it is easily seen that

$v_1, \dots , v_n$

, it is easily seen that

![]() $v_i$

is a simplicial vertex of the induced subgraph

$v_i$

is a simplicial vertex of the induced subgraph

![]() $G_i = G[v_i, \dots , v_n]$

for all i.

$G_i = G[v_i, \dots , v_n]$

for all i.

Theorem 2.2 [Reference Dirac19].

For a graph G, the following are equivalent:

-

(a) G is chordal.

-

(b) G has a perfect elimination order.

-

(c) Every induced subgraph of G has a simplicial vertex.

We will use the stronger concept of strongly chordal graphs. A

strong elimination order

on the set of vertices of G is a perfect elimination order

![]() $v_1, \dots , v_n$

such that whenever

$v_1, \dots , v_n$

such that whenever

![]() $v_iv_k, v_kv_j, v_iv_\ell \in E(G)$

with

$v_iv_k, v_kv_j, v_iv_\ell \in E(G)$

with

![]() $i < k < \ell $

and

$i < k < \ell $

and

![]() $i < j$

, then we also have

$i < j$

, then we also have

![]() $v_jv_\ell \in E(G)$

. The graph G is called

strongly chordal

if it has a strong elimination order.

$v_jv_\ell \in E(G)$

. The graph G is called

strongly chordal

if it has a strong elimination order.

Similar to the case of chordal graphs, strongly chordal graphs can also be characterized by special types of vertices. A vertex v of G is called

simple

if the collection of distinct sets in

![]() $\{N[w] \mid w \in N[v]\}$

is totally ordered by inclusion. In particular, every simple vertex is also simplicial. If

$\{N[w] \mid w \in N[v]\}$

is totally ordered by inclusion. In particular, every simple vertex is also simplicial. If

![]() $v_1, \dots , v_n$

is a strong elimination order for G, it is easily seen that the vertex

$v_1, \dots , v_n$

is a strong elimination order for G, it is easily seen that the vertex

![]() $v_i$

is a simple vertex of the induced subgraph

$v_i$

is a simple vertex of the induced subgraph

![]() $G_i := G[v_i, \dots , v_n]$

for all i.

$G_i := G[v_i, \dots , v_n]$

for all i.

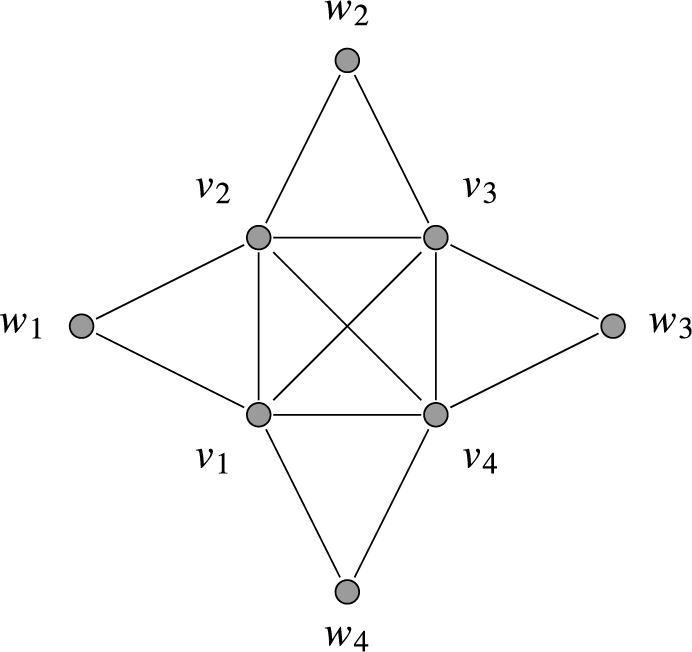

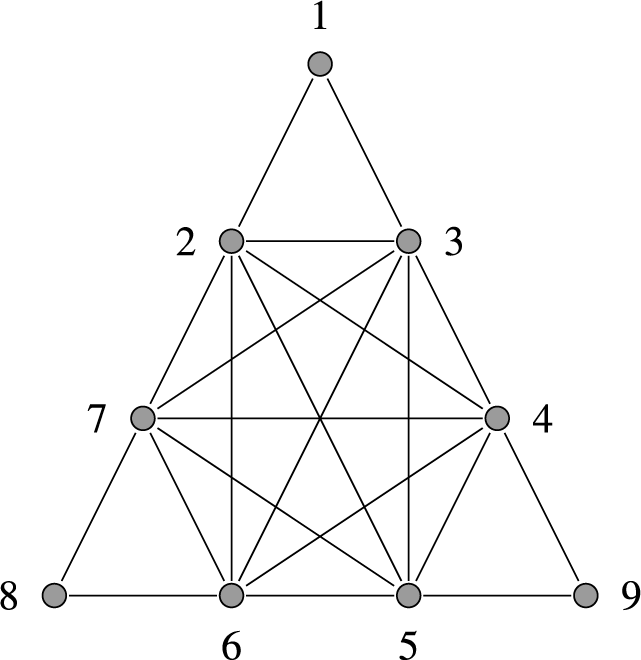

Strongly chordal graphs can also be characterized by forbidden induced subgraphs. A graph T is an n

-trampoline

if it has vertices

![]() $v_1,\dots , v_n, w_1, \dots , w_n$

for some

$v_1,\dots , v_n, w_1, \dots , w_n$

for some

![]() $n \geq 3$

and edges

$n \geq 3$

and edges

![]() $v_iv_j$

for all

$v_iv_j$

for all

![]() $i \neq j$

,

$i \neq j$

,

![]() $w_iv_i$

for all i,

$w_iv_i$

for all i,

![]() $w_iv_{i+1}$

for all

$w_iv_{i+1}$

for all

![]() $i < n$

, and

$i < n$

, and

![]() $w_nv_1$

. We note that the n-trampoline is sometimes referred to as the n-sun graph, and the 3-trampoline is also called the

tent

in the literature on binomial edge ideals. The

$w_nv_1$

. We note that the n-trampoline is sometimes referred to as the n-sun graph, and the 3-trampoline is also called the

tent

in the literature on binomial edge ideals. The

![]() $4$

-trampoline is pictured in Figure 2. Setting

$4$

-trampoline is pictured in Figure 2. Setting

![]() $w_{i + n} = w_i$

, we note that

$w_{i + n} = w_i$

, we note that

![]() $w_i \in N[v_{i+1}] \smallsetminus N[v_{i+2}]$

and

$w_i \in N[v_{i+1}] \smallsetminus N[v_{i+2}]$

and

![]() $w_{i+2} \in N[v_{i+2}] \smallsetminus N[v_{i+1}]$

for all i since

$w_{i+2} \in N[v_{i+2}] \smallsetminus N[v_{i+1}]$

for all i since

![]() $n \geq 3$

. Consequently, the sets

$n \geq 3$

. Consequently, the sets

![]() $N[v_{i+1}]$

and

$N[v_{i+1}]$

and

![]() $N[v_{i+2}]$

are incomparable for all i. Hence, no vertex of the n-trampoline is simple, and so no trampoline graph is strongly chordal.

$N[v_{i+2}]$

are incomparable for all i. Hence, no vertex of the n-trampoline is simple, and so no trampoline graph is strongly chordal.

Figure 2 The 4-trampoline.

Theorem 2.3 [Reference Farber22, 3.3, 4.1].

For a graph G, the following are equivalent:

-

(a) G is strongly chordal.

-

(b) Every induced subgraph of G has a simple vertex.

-

(c) G is chordal and n-trampoline-free for every

$n \geq 3$

.

$n \geq 3$

.

Applying the above theorem to the graphs that we consider in Theorem 2, we get:

Corollary 2.4. A graph G is chordal, claw-free, and tent-free if and only if it is strongly chordal and claw-free.

Proof . Note that the 3-trampoline is the tent. Hence, if G is strongly chordal and claw-free, then G is clearly chordal, claw-free, and tent-free. Conversely, if G is chordal, claw-free, and tent-free, then G is n-trampoline-free since every n-trampoline with

![]() $n> 3$

contains an induced claw, and so, G is strongly chordal.

$n> 3$

contains an induced claw, and so, G is strongly chordal.

In the rest of this section, we assume that G is a simple graph with vertex set

![]() $[n] = \{1, 2, \dots , n\}$

.

$[n] = \{1, 2, \dots , n\}$

.

If i is a simplicial vertex of G, then

![]() $N[i]$

is the unique maximal clique containing i. This motivates the following definition.

$N[i]$

is the unique maximal clique containing i. This motivates the following definition.

Definition 2.5. Let G be a chordal graph.

-

• A simplicial edge of a graph G is an edge e that is contained in exactly one maximal clique of G and

$G \smallsetminus e$

is chordal.

$G \smallsetminus e$

is chordal. -

• A simplicial edge is claw-avoiding if it does not belong to an induced claw of G.

-

• A claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order is an ordering

$e_1, \dots , e_m$

of the edges of G such that

$e_1, \dots , e_m$

of the edges of G such that

$e_i$

is a claw-avoiding simplicial edge of

$e_i$

is a claw-avoiding simplicial edge of

$G \smallsetminus \{e_1, \dots , e_{i-1}\}$

for every i.

$G \smallsetminus \{e_1, \dots , e_{i-1}\}$

for every i.

Remark 2.6. We caution the reader that there is at least one other notion of a simplicial edge in the literature. Dragan [Reference Dragan20] defines the class of strongly orderable graphs as a common generalization of both strongly chordal and chordal bipartite graphs and characterizes them in terms of edges

![]() $e = \{i, j\}$

such that any distinct vertices

$e = \{i, j\}$

such that any distinct vertices

![]() $k \in N(i)$

and

$k \in N(i)$

and

![]() $l \in N(j)$

are adjacent; he calls such an edge a simplicial edge. For chordal graphs, every simplicial edge in Dragan’s sense is a simplicial edge as defined above. However, our notion of simplicial edge is strictly weaker than Dragan’s since the middle edge of a path of length 3 is simplicial in our sense but not Dragan’s.

$l \in N(j)$

are adjacent; he calls such an edge a simplicial edge. For chordal graphs, every simplicial edge in Dragan’s sense is a simplicial edge as defined above. However, our notion of simplicial edge is strictly weaker than Dragan’s since the middle edge of a path of length 3 is simplicial in our sense but not Dragan’s.

Lemma 2.7. Let G be a strongly chordal graph with at least one edge. Then G has a simplicial edge e such that

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

is strongly chordal. Moreover, one can choose the simplicial edge e so that, if G is claw-free then so is

$G \smallsetminus e$

is strongly chordal. Moreover, one can choose the simplicial edge e so that, if G is claw-free then so is

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

.

$G \smallsetminus e$

.

Proof . We may assume that the vertices of G have been labeled so that

![]() $1, 2, \dots , n$

is a strong elimination order. Then

$1, 2, \dots , n$

is a strong elimination order. Then

![]() $1$

is a simple vertex of G, and we can choose j so that

$1$

is a simple vertex of G, and we can choose j so that

![]() $N[j]$

is maximal in the totally ordered set

$N[j]$

is maximal in the totally ordered set

![]() $\{ N[i] \mid i \in N[1]\}$

. We also note that

$\{ N[i] \mid i \in N[1]\}$

. We also note that

![]() $N[1]$

is minimal in

$N[1]$

is minimal in

![]() $\{ N[i] \mid i \in N[1]\}$

. Since

$\{ N[i] \mid i \in N[1]\}$

. Since

![]() $1$

is in particular a simplicial vertex of G, it follows that

$1$

is in particular a simplicial vertex of G, it follows that

![]() $N[1]$

is the unique maximal clique of G containing

$N[1]$

is the unique maximal clique of G containing

![]() $1$

.

$1$

.

We claim that the edge

![]() $e = \{1, j\}$

is simplicial. We have already shown that

$e = \{1, j\}$

is simplicial. We have already shown that

![]() $N[1]$

is the unique maximal clique of G containing e, so it remains to show that

$N[1]$

is the unique maximal clique of G containing e, so it remains to show that

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

is chordal. If

$G \smallsetminus e$

is chordal. If

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

is not chordal, then it contains an induced cycle C of length at least 4. As G is chordal, e must be the unique chord of C, and so C has length 4. Hence, G has an induced subgraph of the form

$G \smallsetminus e$

is not chordal, then it contains an induced cycle C of length at least 4. As G is chordal, e must be the unique chord of C, and so C has length 4. Hence, G has an induced subgraph of the form

which is impossible as

![]() $i, k \in N[1]$

and 1 is a simplicial vertex. Hence, e is a simplicial edge of G as claimed.

$i, k \in N[1]$

and 1 is a simplicial vertex. Hence, e is a simplicial edge of G as claimed.

To see that

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

is still strongly chordal, we note that

$G \smallsetminus e$

is still strongly chordal, we note that

![]() $N_{G \smallsetminus e}[1] = N_G[1] \smallsetminus \{j\}$

and that

$N_{G \smallsetminus e}[1] = N_G[1] \smallsetminus \{j\}$

and that

![]() $N_{G \smallsetminus e}[i] = N_G[i]$

for all

$N_{G \smallsetminus e}[i] = N_G[i]$

for all

![]() $i \neq 1, j$

, so the set

$i \neq 1, j$

, so the set

is still totally ordered by inclusion. Hence,

![]() $1$

is still a simple vertex of

$1$

is still a simple vertex of

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

, and the graph

$G \smallsetminus e$

, and the graph

![]() $(G \smallsetminus e) \smallsetminus \{1\} = G \smallsetminus \{1\}$

has

$(G \smallsetminus e) \smallsetminus \{1\} = G \smallsetminus \{1\}$

has

![]() $2, \dots , n$

as a simple elimination order. Thus,

$2, \dots , n$

as a simple elimination order. Thus,

![]() $1, 2, \dots , n$

is a simple elimination order for

$1, 2, \dots , n$

is a simple elimination order for

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

, so

$G \smallsetminus e$

, so

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

is strongly chordal by Theorem 2.3.

$G \smallsetminus e$

is strongly chordal by Theorem 2.3.

Suppose in addition we know that G is claw-free. If

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

has an induced claw, then G has an induced subgraph of the form

$G \smallsetminus e$

has an induced claw, then G has an induced subgraph of the form

But this is impossible since

![]() $k \in N[1]$

implies

$k \in N[1]$

implies

![]() $l \in N[k] \subseteq N[j]$

.

$l \in N[k] \subseteq N[j]$

.

The following is a refinement of [Reference Mohammadi and Sharifan29, 3.7].

Proposition 2.8. Let G be a graph and

![]() $e = \{i,j\} \in E(G)$

. Denote by

$e = \{i,j\} \in E(G)$

. Denote by

![]() $G_{e}$

the graph on

$G_{e}$

the graph on

![]() $[n]=\{1,\dots ,n\}$

having edge set

$[n]=\{1,\dots ,n\}$

having edge set

$$\begin{align*}E(G_{e}) = E(G \smallsetminus e) \cup \binom{N_{G \smallsetminus e}(i)}{2} \cup \binom{N_{G \smallsetminus e}(j)}{2}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}E(G_{e}) = E(G \smallsetminus e) \cup \binom{N_{G \smallsetminus e}(i)}{2} \cup \binom{N_{G \smallsetminus e}(j)}{2}. \end{align*}$$

For any cycle

![]() $C: i = i_0, i_1, \dots , i_s, i_{s+1}= j$

of G containing e and

$C: i = i_0, i_1, \dots , i_s, i_{s+1}= j$

of G containing e and

![]() $0 \leq t \leq s$

, set

$0 \leq t \leq s$

, set

Then

We observe that the graph

![]() $G_e$

of the theorem is the graph obtained from

$G_e$

of the theorem is the graph obtained from

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

by adding edges to turn the ends of e into simplicial vertices of

$G \smallsetminus e$

by adding edges to turn the ends of e into simplicial vertices of

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

.

$G \smallsetminus e$

.

Proof . The statement of the proposition is precisely [Reference Mohammadi and Sharifan29, 3.7] if we omit the condition that the cycles C are induced. In the statement of that theorem, the monomials are indexed instead by paths from i to j in

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

, but such paths correspond bijectively with cycles of G containing e. We will show that each monomial

$G \smallsetminus e$

, but such paths correspond bijectively with cycles of G containing e. We will show that each monomial

![]() $g_{C, t}$

is divisible by a suitable monomial

$g_{C, t}$

is divisible by a suitable monomial

![]() $g_{C', t'}$

whenever C admits a chord.

$g_{C', t'}$

whenever C admits a chord.

Let

![]() $C: i = i_0, i_1, \dots , i_s, i_{s+1} = j$

be any cycle of G containing e. If C has a chord

$C: i = i_0, i_1, \dots , i_s, i_{s+1} = j$

be any cycle of G containing e. If C has a chord

![]() $\{i_p, i_q\}$

for some

$\{i_p, i_q\}$

for some

![]() $p < q$

, then we have a cycle

$p < q$

, then we have a cycle

![]() $C': i = i_0, i_1, \dots , i_p, i_q, i_{q+1}, \dots , i_{s+1} = j$

so that

$C': i = i_0, i_1, \dots , i_p, i_q, i_{q+1}, \dots , i_{s+1} = j$

so that

divides

![]() $g_{C, t}$

for all

$g_{C, t}$

for all

![]() $t < p$

,

$t < p$

,

divides

![]() $g_{C, t}$

for all

$g_{C, t}$

for all

![]() $p \leq t < q$

, and

$p \leq t < q$

, and

divides

![]() $g_{C,t}$

for all

$g_{C,t}$

for all

![]() $t \geq q$

.

$t \geq q$

.

Corollary 2.9. Let G be a chordal graph, and let

![]() $e \in E(G)$

be a claw-avoiding simplicial edge. Let U be the unique maximal clique of G containing e. Then

$e \in E(G)$

be a claw-avoiding simplicial edge. Let U be the unique maximal clique of G containing e. Then

Proof . By the preceding proposition, we know that

![]() $J_{G \smallsetminus e}: f_e = J_{G_e} + L$

, where

$J_{G \smallsetminus e}: f_e = J_{G_e} + L$

, where

If

![]() $e = \{i,j\}$

, then for every

$e = \{i,j\}$

, then for every

![]() $k \in U \smallsetminus e$

, we have an induced

$k \in U \smallsetminus e$

, we have an induced

![]() $3$

-cycle

$3$

-cycle

![]() $i,j,k$

so that

$i,j,k$

so that

On the other hand, every induced cycle of G has length 3 since G is chordal so that

![]() $L = (x_k,y_k \mid k \in U\smallsetminus e)$

.

$L = (x_k,y_k \mid k \in U\smallsetminus e)$

.

Next, we show that

![]() $J_{G_e} + L = J_{G \smallsetminus e} + L$

. Since

$J_{G_e} + L = J_{G \smallsetminus e} + L$

. Since

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

is a subgraph of

$G \smallsetminus e$

is a subgraph of

![]() $G_e$

, it is clear that

$G_e$

, it is clear that

![]() $J_{G \smallsetminus e} + L \subseteq J_{G_e} + L$

. Every additional generator of

$J_{G \smallsetminus e} + L \subseteq J_{G_e} + L$

. Every additional generator of

![]() $J_{G_e}$

but not

$J_{G_e}$

but not

![]() $J_{G \smallsetminus e}$

is of the form

$J_{G \smallsetminus e}$

is of the form

![]() $f_{k, l}$

for some

$f_{k, l}$

for some

![]() $k,l \in N_{G \smallsetminus e}(i)$

or

$k,l \in N_{G \smallsetminus e}(i)$

or

![]() $k, l \in N_{G \smallsetminus e}(j)$

. If

$k, l \in N_{G \smallsetminus e}(j)$

. If

![]() $k, l \in N_{G \smallsetminus e}(i)$

, the induced subgraph on

$k, l \in N_{G \smallsetminus e}(i)$

, the induced subgraph on

![]() $\{i,j,k,l\}$

has as an edge

$\{i,j,k,l\}$

has as an edge

![]() $\{j,k\}$

,

$\{j,k\}$

,

![]() $\{j,l\}$

, or

$\{j,l\}$

, or

![]() $\{k,l\}$

because e does not belong to an induced claw of G. If

$\{k,l\}$

because e does not belong to an induced claw of G. If

![]() $\{k,l\}$

is an edge, then

$\{k,l\}$

is an edge, then

![]() $f_{k, l} \in J_{G \smallsetminus e}$

. On the other hand, if

$f_{k, l} \in J_{G \smallsetminus e}$

. On the other hand, if

![]() $\{j,l\}$

or

$\{j,l\}$

or

![]() $\{j,k\}$

is an edge of G, then either

$\{j,k\}$

is an edge of G, then either

![]() $\{i, j, l\}$

or

$\{i, j, l\}$

or

![]() $\{i, j, k\}$

is a clique containing e, and so, either l or k belongs to U as e is simplicial, in which case it is clear that

$\{i, j, k\}$

is a clique containing e, and so, either l or k belongs to U as e is simplicial, in which case it is clear that

![]() $f_{k,l} \in L$

. Either way, we see that

$f_{k,l} \in L$

. Either way, we see that

![]() $f_{k, l} \in J_{G \smallsetminus e} + L$

, and the argument is completely analogous if

$f_{k, l} \in J_{G \smallsetminus e} + L$

, and the argument is completely analogous if

![]() $k, l \in N_{G \smallsetminus e}(j)$

. Thus, we have

$k, l \in N_{G \smallsetminus e}(j)$

. Thus, we have

![]() $J_{G_e} + L = J_{G \smallsetminus e} + L$

as claimed.

$J_{G_e} + L = J_{G \smallsetminus e} + L$

as claimed.

We are now ready to prove our main theorem. Recall the notation in Definition 1.1.

Proof of Theorem 2.1.

We argue by induction on the number of edges of G. If G has no edges, then

![]() $J_G = 0$

and the statement holds trivially. So, we may assume that G has at least one edge and that the theorem holds for all claw-free strongly chordal graphs with fewer edges. In that case, since G is strongly chordal and claw-free, it has a simplicial edge e such that

$J_G = 0$

and the statement holds trivially. So, we may assume that G has at least one edge and that the theorem holds for all claw-free strongly chordal graphs with fewer edges. In that case, since G is strongly chordal and claw-free, it has a simplicial edge e such that

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

is strongly chordal and claw-free by Lemma 2.7. Since

$G \smallsetminus e$

is strongly chordal and claw-free by Lemma 2.7. Since

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

is a claw-free strongly chordal graph with fewer edges than G, we know that

$G \smallsetminus e$

is a claw-free strongly chordal graph with fewer edges than G, we know that

![]() $R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

is Koszul by induction. We will show that

$R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

is Koszul by induction. We will show that

![]() $R_G$

is Koszul as well.

$R_G$

is Koszul as well.

Let K be the unique maximal clique of G containing e. Corollary 2.9 yields the exact sequence of

![]() $R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

-modules

$R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

-modules

where H is the induced subgraph of

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

obtained by deleting the vertices of

$G \smallsetminus e$

obtained by deleting the vertices of

![]() $K \smallsetminus e$

. Since H is an induced subgraph of

$K \smallsetminus e$

. Since H is an induced subgraph of

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

, we have that

$G \smallsetminus e$

, we have that

![]() $R_H$

is an algebra retract of

$R_H$

is an algebra retract of

![]() $R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

; this means that we have the homogeneous inclusion

$R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

; this means that we have the homogeneous inclusion

![]() $i: \ R_H\subset R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

and homogeneous surjection

$i: \ R_H\subset R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

and homogeneous surjection

![]() $\varphi : R_{G \smallsetminus e} \longrightarrow R_H$

so that

$\varphi : R_{G \smallsetminus e} \longrightarrow R_H$

so that

![]() $\varphi i=id$

(see [Reference Römer and Saeedi Madani38] for other applications of algebra retracts in an algebra-graph setting). Combining this with the assumption that

$\varphi i=id$

(see [Reference Römer and Saeedi Madani38] for other applications of algebra retracts in an algebra-graph setting). Combining this with the assumption that

![]() $R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

is Koszul yields that

$R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

is Koszul yields that

![]() $R_H$

has a linear free resolution as a module over

$R_H$

has a linear free resolution as a module over

![]() $R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

by [Reference Ohsugi, Herzog and Hibi31, 1.4]. Now, combine this with the above short exact sequence, and conclude that

$R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

by [Reference Ohsugi, Herzog and Hibi31, 1.4]. Now, combine this with the above short exact sequence, and conclude that

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {reg}}_{R_{G \smallsetminus e}} R_G \leq 1$

. It follows that

$\operatorname {\mathrm {reg}}_{R_{G \smallsetminus e}} R_G \leq 1$

. It follows that

![]() $R_G$

is Koszul by [Reference Conca, De Negri and Evelina Rossi12, Theorem 2].

$R_G$

is Koszul by [Reference Conca, De Negri and Evelina Rossi12, Theorem 2].

Corollary 2.10. Let G be a chordal graph and

![]() $e \in E(G)$

be a claw-avoiding simplicial edge of G. If

$e \in E(G)$

be a claw-avoiding simplicial edge of G. If

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

is strongly chordal and claw-free, then so is G.

$G \smallsetminus e$

is strongly chordal and claw-free, then so is G.

Proof . By our main theorem 1.2, the ring

![]() $R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

is Koszul. Then the proof above implies that

$R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

is Koszul. Then the proof above implies that

![]() $R_G$

is also Koszul. Applying our main theorem once more yields that G is strongly chordal and claw-free.

$R_G$

is also Koszul. Applying our main theorem once more yields that G is strongly chordal and claw-free.

Corollary 2.11. A chordal graph is strongly chordal and claw-free if and only if it has a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order.

Proof . (

![]() $\Rightarrow $

): We argue by induction on the number of edges of G. The statement holds trivially if G has no edges, so we may assume that G has at least one edge and that all claw-free strongly chordal graphs with fewer edges have a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order. By Lemma 2.7, there is a simplicial edge

$\Rightarrow $

): We argue by induction on the number of edges of G. The statement holds trivially if G has no edges, so we may assume that G has at least one edge and that all claw-free strongly chordal graphs with fewer edges have a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order. By Lemma 2.7, there is a simplicial edge

![]() $e_1$

of G such that

$e_1$

of G such that

![]() $G \smallsetminus e_1$

is strongly chordal and claw-free. Note that

$G \smallsetminus e_1$

is strongly chordal and claw-free. Note that

![]() $e_1$

is claw-avoiding as G is claw-free. By induction

$e_1$

is claw-avoiding as G is claw-free. By induction

![]() $G \smallsetminus e_1$

has a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order

$G \smallsetminus e_1$

has a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order

![]() $e_2, \dots , e_m$

, and so

$e_2, \dots , e_m$

, and so

![]() $e_1, e_2, \dots , e_m$

is a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order for G.

$e_1, e_2, \dots , e_m$

is a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order for G.

(

![]() $\Leftarrow $

): Let

$\Leftarrow $

): Let

![]() $e_1, \dots , e_m$

be a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order for G. Again, we argue by induction on m. The case

$e_1, \dots , e_m$

be a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order for G. Again, we argue by induction on m. The case

![]() $m = 0$

being trivial, we may assume that

$m = 0$

being trivial, we may assume that

![]() $m \geq 1$

and that the corollary holds for all chordal graphs having a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order with fewer edges. Since

$m \geq 1$

and that the corollary holds for all chordal graphs having a claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order with fewer edges. Since

![]() $e_1$

is a claw-avoiding simplicial edge of G, we know in particular that

$e_1$

is a claw-avoiding simplicial edge of G, we know in particular that

![]() $G \smallsetminus e_1$

is chordal, and as

$G \smallsetminus e_1$

is chordal, and as

![]() $G \smallsetminus e_1$

has claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order

$G \smallsetminus e_1$

has claw-avoiding perfect edge elimination order

![]() $e_2, \dots , e_m$

, it follows by induction that

$e_2, \dots , e_m$

, it follows by induction that

![]() $G \smallsetminus e_1$

is strongly chordal and claw-free. Thus, Corollary 2.10 implies that G is also strongly chordal and claw-free.

$G \smallsetminus e_1$

is strongly chordal and claw-free. Thus, Corollary 2.10 implies that G is also strongly chordal and claw-free.

3 Closed graphs and quadratic Gröbner bases

In the next section, we will make use of the concept of closed graphs, whose properties are reviewed here.

A

closed order

for a graph G is an ordering

![]() $v_1, \dots , v_n$

of its vertices such that whenever

$v_1, \dots , v_n$

of its vertices such that whenever

![]() $v_iv_j, v_iv_k \in E(G)$

and either

$v_iv_j, v_iv_k \in E(G)$

and either

![]() $i < j, k$

or

$i < j, k$

or

![]() $i> j, k$

, then

$i> j, k$

, then

![]() $v_jv_k \in E(G)$

. The graph G is a

closed graph

if it has a closed order. It is straightforward to check that every closed order is a strong elimination order. (There are two cases to consider depending on whether

$v_jv_k \in E(G)$

. The graph G is a

closed graph

if it has a closed order. It is straightforward to check that every closed order is a strong elimination order. (There are two cases to consider depending on whether

![]() $k < j$

or

$k < j$

or

![]() $j < k$

.) Thus, every closed graph is strongly chordal.

$j < k$

.) Thus, every closed graph is strongly chordal.

The significance of closed graphs is that they characterize when binomial edge ideals have a quadratic Gröbner basis. Hence, the binomial edge ideal of any closed graph is Koszul.

Theorem 3.1 [Reference Herzog, Hibi, Hreinsdóttir, Kahle and Rauh25, 1.1][Reference Crupi and Rinaldo16, 3.4].

For a graph G, the following are equivalent:

-

(a)

$J_G$

has a quadratic Gröbner basis with respect to some monomial order.

$J_G$

has a quadratic Gröbner basis with respect to some monomial order. -

(b)

$J_G$

has a quadratic Gröbner basis with respect to some lex order.

$J_G$

has a quadratic Gröbner basis with respect to some lex order. -

(c) G is a closed graph.

Denoting by

the sets of neighbors of the vertex

![]() $v_i$

that come after or before i respectively in the given order, we can characterize when G has a closed order as follows.

$v_i$

that come after or before i respectively in the given order, we can characterize when G has a closed order as follows.

Proposition 3.2 [Reference Crupi and Rinaldo16, 4.8][Reference Cox and Erskine15, 2.2].

For a graph G, the following are equivalent:

-

(a)

$v_1, \dots , v_n$

is closed order for G.

$v_1, \dots , v_n$

is closed order for G. -

(b) The sets

$N^{\leq }[v_i]$

and

$N^{\leq }[v_i]$

and

$N^{\geq }[v_i]$

are both cliques for all i.

$N^{\geq }[v_i]$

are both cliques for all i. -

(c) The set

$N^{\geq }[v_i]$

is a clique and

$N^{\geq }[v_i]$

is a clique and

$N^{\geq }[v_i] = [v_i, v_{i+r}]$

, where

$N^{\geq }[v_i] = [v_i, v_{i+r}]$

, where

$r = \left \vert N^{\geq }[v_i] \right \vert $

, for all i.

$r = \left \vert N^{\geq }[v_i] \right \vert $

, for all i.

A graph G is an

intersection graph

if there is a family of sets

![]() $\{F_i\}_{i \in V(G)}$

such that

$\{F_i\}_{i \in V(G)}$

such that

![]() $ij \in E(G)$

if and only if

$ij \in E(G)$

if and only if

![]() $F_i \cap F_j \neq \varnothing $

. A graph G is an

interval graph

if it is the intersection graph of a family of open intervals of real numbers. If the family of intervals can be chosen so that no interval properly contains any other, then G is a

proper interval graph

. A

proper interval order

for a graph G is an ordering

$F_i \cap F_j \neq \varnothing $

. A graph G is an

interval graph

if it is the intersection graph of a family of open intervals of real numbers. If the family of intervals can be chosen so that no interval properly contains any other, then G is a

proper interval graph

. A

proper interval order

for a graph G is an ordering

![]() $v_1, \dots , v_n$

of its vertices such that whenever

$v_1, \dots , v_n$

of its vertices such that whenever

![]() $v_iv_k \in E(G)$

and

$v_iv_k \in E(G)$

and

![]() $i < j < k$

, then

$i < j < k$

, then

![]() $v_iv_j, v_jv_k \in E(G)$

. We note that every proper interval order is a closed order and vice versa by Proposition 3.2.

$v_iv_j, v_jv_k \in E(G)$

. We note that every proper interval order is a closed order and vice versa by Proposition 3.2.

Theorem 3.3 [Reference Crupi and Rinaldo17, 2.2][Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, 7.10].

For a graph G, the following are equivalent:

-

(a) G is a closed graph.

-

(b) G has a proper interval order.

-

(c) G is a proper interval graph.

-

(d) G is chordal, claw-free, net-free, and tent-free.

The net (see Figure 1) is the smallest example of a nonclosed graph whose binomial edge ideal is Koszul; a Koszul filtration argument is given in [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, 7.56]. Our main theorem 1.2 shows that the presence of induced nets is precisely the difference between those binomial edge ideals that are Koszul and those that admit a quadratic Gröbner basis.

4 Obstructions to Koszulness

As discussed in the introduction, the “only if” direction of Theorem 1.2 was already shown by Ene, Herzog, and Hibi, namely:

Theorem 4.1 [Reference Ene, Herzog and Hibi21], [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, Section 7.4.1].

If the binomial edge ideal

![]() $J_G$

is Koszul, then the graph G is chordal, claw-free, and tent-free.

$J_G$

is Koszul, then the graph G is chordal, claw-free, and tent-free.

Their argument easily reduces to checking that the binomial edge ideals of n-cycles for

![]() $n \ge 4$

, the claw, and the tent are not Koszul, which they verify by computer. For completeness, in the three lemmas below, we provide direct proofs that the binomial edge ideals of n-cycles for

$n \ge 4$

, the claw, and the tent are not Koszul, which they verify by computer. For completeness, in the three lemmas below, we provide direct proofs that the binomial edge ideals of n-cycles for

![]() $n \ge 4$

, the claw, and the tent are not Koszul in any characteristic. The arguments for the n-cycles and the claw are fairly quick, but the reasoning for the tent is longer and more intricate.

$n \ge 4$

, the claw, and the tent are not Koszul in any characteristic. The arguments for the n-cycles and the claw are fairly quick, but the reasoning for the tent is longer and more intricate.

Some care about the characteristic is warranted since D’Alì and Venturello have shown [Reference D’Alì and Venturello18, 5.15] that for any finite list of primes P, it is possible to construct ideals of polynomials with integer coefficients that fail to be Koszul modulo p exactly when

![]() $p \in P$

. Moreover, there are examples of graphs G such that the finite resolution of

$p \in P$

. Moreover, there are examples of graphs G such that the finite resolution of

![]() $J_G$

over the ambient polynomial ring can depend on the characteristic of the coefficient field [Reference Bolognini, Macchia and Strazzanti5, 7.6], [Reference Bolognini, Macchia, Strazzanti and Welker6, 5.9]. A priori, the Koszul property of

$J_G$

over the ambient polynomial ring can depend on the characteristic of the coefficient field [Reference Bolognini, Macchia and Strazzanti5, 7.6], [Reference Bolognini, Macchia, Strazzanti and Welker6, 5.9]. A priori, the Koszul property of

![]() $R_G$

could depend on the characteristic as well, although it follows from Theorem 2.1 that this is not the case.

$R_G$

could depend on the characteristic as well, although it follows from Theorem 2.1 that this is not the case.

Throughout this section, we set

![]() $f_{i,j} = x_iy_j - x_jy_i$

for any i and j (not necessarily adjacent in G); in particular,

$f_{i,j} = x_iy_j - x_jy_i$

for any i and j (not necessarily adjacent in G); in particular,

![]() $J_G$

is generated by the

$J_G$

is generated by the

![]() $f_{i,j}$

corresponding to edges.

$f_{i,j}$

corresponding to edges.

We will make frequent use of known restrictions on graded Betti numbers of Koszul algebras. We refer the reader to [Reference Peeva34] for background on free resolutions and graded Betti numbers; we just recall the definition of the graded Betti number

![]() $\beta _{i,j}^R(M)$

of a finitely generated graded R-module M over a graded

$\beta _{i,j}^R(M)$

of a finitely generated graded R-module M over a graded

![]() $\Bbbk $

-algebra R:

$\Bbbk $

-algebra R:

The graded Betti numbers may be displayed in the Betti table, which contains

![]() $\beta _{i,j}^R(M)$

in the

$\beta _{i,j}^R(M)$

in the

![]() $i,i+j$

’th slot. We will also use the following result of Blum concerning when the symmetric algebra

$i,i+j$

’th slot. We will also use the following result of Blum concerning when the symmetric algebra

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Sym}}_R(M)$

is Koszul.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Sym}}_R(M)$

is Koszul.

Proposition 4.2 [Reference Blum4, 3.1].

Let R be a standard graded

![]() $\Bbbk $

-algebra and M be a finitely generated graded R-module such that

$\Bbbk $

-algebra and M be a finitely generated graded R-module such that

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Sym}}_R(M)$

is Koszul. Then R is also Koszul, and

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Sym}}_R(M)$

is Koszul. Then R is also Koszul, and

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Sym}}_R^i(M)$

has a linear free resolution over R for all i. In particular, M has a linear free resolution over R.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Sym}}_R^i(M)$

has a linear free resolution over R for all i. In particular, M has a linear free resolution over R.

Lemma 4.3. Let

![]() $C_n$

be the n-cycle. Then the ring

$C_n$

be the n-cycle. Then the ring

![]() $R_{C_n}$

is not Koszul.

$R_{C_n}$

is not Koszul.

Proof . For

![]() $n \ge 5$

, see the proof in [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, 7.47] where it is shown that

$n \ge 5$

, see the proof in [Reference Herzog, Hibi and Ohsugi26, 7.47] where it is shown that

![]() $J_{C_n}$

has a minimal first syzygy of degree n; for

$J_{C_n}$

has a minimal first syzygy of degree n; for

![]() $n \ge 5$

, if

$n \ge 5$

, if

![]() $J_{C_n}$

were Koszul, this contradicts [Reference Kempf27, Lemma 4]. For

$J_{C_n}$

were Koszul, this contradicts [Reference Kempf27, Lemma 4]. For

![]() $n = 4$

, consider the graph G shown below

$n = 4$

, consider the graph G shown below

and set

![]() $e = \{2, 3\}$

. Note that

$e = \{2, 3\}$

. Note that

![]() $G \smallsetminus e = C_4$

. We will show that

$G \smallsetminus e = C_4$

. We will show that

![]() $\beta ^S_{2,4}(R_{C_4}) = 9> \binom {4}{2}$

, so

$\beta ^S_{2,4}(R_{C_4}) = 9> \binom {4}{2}$

, so

![]() $R_{C_4}$

is not Koszul by [Reference Boocher, Hamid Hassanzadeh and Iyengar8, 3.4].

$R_{C_4}$

is not Koszul by [Reference Boocher, Hamid Hassanzadeh and Iyengar8, 3.4].

Note that

![]() $S_G=\Bbbk [x_1, \dots ,x_4, y_1, \dots , y_4].$

First, we observe that the labeling of G is closed, and so

$S_G=\Bbbk [x_1, \dots ,x_4, y_1, \dots , y_4].$

First, we observe that the labeling of G is closed, and so

![]() $R_G$

has a quadratic Gröbner basis with respect to the lex order with

$R_G$

has a quadratic Gröbner basis with respect to the lex order with

![]() $x_1> \cdots > x_4 > y_1 > \cdots > y_4$

. In particular, we have that the initial ideal is

$x_1> \cdots > x_4 > y_1 > \cdots > y_4$

. In particular, we have that the initial ideal is

so it is the edge ideal of a path with 6 vertices. Using [Reference Boocher, D’Alì, Grifo, Montaño and Sammartano7, 3.4, 3.5], one can check that the Betti table of

![]() $S_G/\operatorname {\mathrm {in}}_>(J_G)$

is:

$S_G/\operatorname {\mathrm {in}}_>(J_G)$

is:

Since G is a closed graph,

![]() $\beta _{i,j}^R(R_G) = \beta _{i,j}^{S_G}(S_G/\operatorname {\mathrm {in}}_>(J_G))$

for all

$\beta _{i,j}^R(R_G) = \beta _{i,j}^{S_G}(S_G/\operatorname {\mathrm {in}}_>(J_G))$

for all

![]() $i,j$

( see [Reference Peeva35, 1.3]).

$i,j$

( see [Reference Peeva35, 1.3]).

To see that

![]() $\beta ^S_{2,4}(R_{C_4}) = 9$

, we note that Theorem 2.8 yields the exact sequence

$\beta ^S_{2,4}(R_{C_4}) = 9$

, we note that Theorem 2.8 yields the exact sequence

from which we obtain the exact sequence

$$ \begin{align*} 0 = \operatorname{\mathrm{Tor}}_3^{S_G}(R_G, \Bbbk)_4 &\to \operatorname{\mathrm{Tor}}_2^{S_G}({S_G}/(x_1,y_1, x_4, y_4), \Bbbk)_2 \to \operatorname{\mathrm{Tor}}_2^{S_G}(R_{C_4}, \Bbbk)_4 \\ &\to \operatorname{\mathrm{Tor}}_2^{S_G}(R_G, \Bbbk)_4 \to \operatorname{\mathrm{Tor}}_1^{S_G}({S_G}/(x_1,y_1, x_4, y_4), \Bbbk)_2 = 0. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} 0 = \operatorname{\mathrm{Tor}}_3^{S_G}(R_G, \Bbbk)_4 &\to \operatorname{\mathrm{Tor}}_2^{S_G}({S_G}/(x_1,y_1, x_4, y_4), \Bbbk)_2 \to \operatorname{\mathrm{Tor}}_2^{S_G}(R_{C_4}, \Bbbk)_4 \\ &\to \operatorname{\mathrm{Tor}}_2^{S_G}(R_G, \Bbbk)_4 \to \operatorname{\mathrm{Tor}}_1^{S_G}({S_G}/(x_1,y_1, x_4, y_4), \Bbbk)_2 = 0. \end{align*} $$

Since

![]() $x_1,y_1,x_4,y_4$

is a regular sequence on

$x_1,y_1,x_4,y_4$

is a regular sequence on

![]() ${S_G}$

, we have

${S_G}$

, we have

as desired.

Lemma 4.4. Let G be the claw. Then the ring

![]() $R_{G}$

is not Koszul.

$R_{G}$

is not Koszul.

Proof . Consider the claw G labeled as shown below

Thus, the binomial edge ideal is

![]() $J_G = (f_{1,2}, f_{1,3}, f_{1,4}) \subseteq S_G = \Bbbk [x_1, y_1, \dots , x_4, y_4]$

. If

$J_G = (f_{1,2}, f_{1,3}, f_{1,4}) \subseteq S_G = \Bbbk [x_1, y_1, \dots , x_4, y_4]$

. If

![]() $e = \{1,4\}$

, then Theorem 2.8 shows that

$e = \{1,4\}$

, then Theorem 2.8 shows that

![]() $J_{G \smallsetminus e} : f_e = J_{G_e} = (f_{1,2}, f_{1,3}, f_{2,3})$

, since

$J_{G \smallsetminus e} : f_e = J_{G_e} = (f_{1,2}, f_{1,3}, f_{2,3})$

, since

![]() $G \smallsetminus e$

has no induced cycles. Hence,

$G \smallsetminus e$

has no induced cycles. Hence,

![]() $J_{G \smallsetminus e} : f_e = I_2(M)$

, where

$J_{G \smallsetminus e} : f_e = I_2(M)$

, where

$$\begin{align*}M = \begin{pmatrix} x_1 & x_2 & x_3 \\ y_1 & y_2 & y_3 \end{pmatrix}, \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}M = \begin{pmatrix} x_1 & x_2 & x_3 \\ y_1 & y_2 & y_3 \end{pmatrix}, \end{align*}$$

which has a Hilbert-Burch resolution. Applying Theorem 2.8 once more to

![]() $G' = G \smallsetminus \{4\}$

and the edge

$G' = G \smallsetminus \{4\}$

and the edge

![]() $e' = \{1, 3\}$

shows that

$e' = \{1, 3\}$

shows that

![]() $(f_{1,2}) : f_{1,3} = J_{G'\smallsetminus e'} : f_{e'} = J_{G^{\prime }_{e'}} = (f_{1,2})$

, so

$(f_{1,2}) : f_{1,3} = J_{G'\smallsetminus e'} : f_{e'} = J_{G^{\prime }_{e'}} = (f_{1,2})$

, so

![]() $J_{G \smallsetminus e} = (f_{1,2}, f_{1,3})$

is a complete intersection. We can construct an explicit chain map lifting the multiplication by

$J_{G \smallsetminus e} = (f_{1,2}, f_{1,3})$

is a complete intersection. We can construct an explicit chain map lifting the multiplication by

![]() $f_{1,4}$

map

$f_{1,4}$

map

![]() $S_G/I_2(M)(-2) \to R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

as shown below.

$S_G/I_2(M)(-2) \to R_{G \smallsetminus e}$

as shown below.

The first column of the middle vertical map comes from the Plücker relation

![]() $f_{1,2}f_{3,4} - f_{1,3}f_{2,4} + f_{2,3}f_{1,4} = 0$

(see [Reference Bruns and Herzog10, 7.2.3]). Hence, the mapping cone of the above chain map yields the minimal free resolution of

$f_{1,2}f_{3,4} - f_{1,3}f_{2,4} + f_{2,3}f_{1,4} = 0$

(see [Reference Bruns and Herzog10, 7.2.3]). Hence, the mapping cone of the above chain map yields the minimal free resolution of

![]() $R_G$

, which has Betti table:

$R_G$

, which has Betti table:

In particular, because

![]() $\beta ^S_{2,4}(R_G) = 4> \binom {3}{2}$

, we see that

$\beta ^S_{2,4}(R_G) = 4> \binom {3}{2}$

, we see that

![]() $R_G$

is not Koszul by [Reference Boocher, Hamid Hassanzadeh and Iyengar8, 3.4].

$R_G$

is not Koszul by [Reference Boocher, Hamid Hassanzadeh and Iyengar8, 3.4].

Lemma 4.5. Let T be the tent. Then the ring

![]() $R_T$

is not Koszul.

$R_T$

is not Koszul.

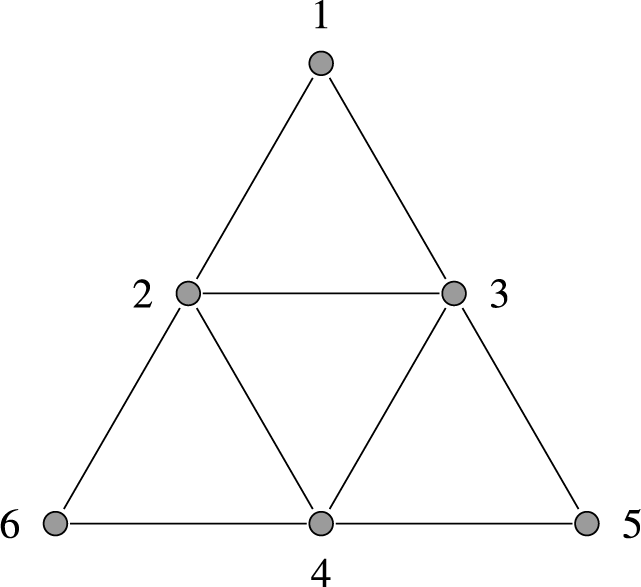

Proof . Consider the tent T with labeling as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 The tent.

Setting

![]() $G = T \smallsetminus \{6\}$

, we note that

$G = T \smallsetminus \{6\}$

, we note that

![]() $R_T \cong \operatorname {\mathrm {Sym}}_{R_G}(M)$

, where M is the cokernel of the matrix

$R_T \cong \operatorname {\mathrm {Sym}}_{R_G}(M)$

, where M is the cokernel of the matrix

$$\begin{align*}\partial_1 = \begin{pmatrix} -y_2 & -y_4 \\ x_2 & x_4 \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\partial_1 = \begin{pmatrix} -y_2 & -y_4 \\ x_2 & x_4 \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

If

![]() $R_T$

is Koszul, then M has a linear free resolution over

$R_T$

is Koszul, then M has a linear free resolution over

![]() $R_G$

by Proposition 4.2. However, we will show that M has a minimal nonlinear fourth syzygy, and so the ring

$R_G$

by Proposition 4.2. However, we will show that M has a minimal nonlinear fourth syzygy, and so the ring

![]() $R_T$

is not Koszul.

$R_T$

is not Koszul.

To see this, we first note that the labeling of G is closed, and so

![]() $J_G$

has a quadratic Gröbner basis with respect to the lex order with

$J_G$

has a quadratic Gröbner basis with respect to the lex order with

![]() $x_1> \cdots > x_5 > y_1 > \cdots > y_5$

. In particular, we have that the initial ideal is

$x_1> \cdots > x_5 > y_1 > \cdots > y_5$

. In particular, we have that the initial ideal is

Thus, the quotient

![]() $R_G$

has a monomial basis consisting of all monomials not contained in the above monomial ideal. We also note that

$R_G$

has a monomial basis consisting of all monomials not contained in the above monomial ideal. We also note that

![]() $R_G$

admits a

$R_G$

admits a

![]() $\mathbb {Z}^5$

-grading via

$\mathbb {Z}^5$

-grading via

![]() $\deg x_i = \deg y_i = \mathbf {e}_i$

, where

$\deg x_i = \deg y_i = \mathbf {e}_i$

, where

![]() $\mathbf {e}_i$

is the i-th standard basis vector of

$\mathbf {e}_i$

is the i-th standard basis vector of

![]() $\mathbb {Z}^5$

, and

$\mathbb {Z}^5$

, and

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _1$

is homogeneous with respect to this grading. We exploit this grading to simplify the computation of the first few terms of the linear strand of the minimal free resolution of M.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _1$

is homogeneous with respect to this grading. We exploit this grading to simplify the computation of the first few terms of the linear strand of the minimal free resolution of M.

Let

![]() $u = (u_1, u_2) \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _1 \subseteq R_G(-\mathbf {e}_2) \oplus R_G(-\mathbf {e}_4)$

be a nonzero homogeneous element of degree

$u = (u_1, u_2) \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _1 \subseteq R_G(-\mathbf {e}_2) \oplus R_G(-\mathbf {e}_4)$

be a nonzero homogeneous element of degree

![]() $\mathbf {a} \in \mathbb {Z}^5$

. Since

$\mathbf {a} \in \mathbb {Z}^5$

. Since

![]() $(R_G)_{\mathbf {b}} = 0$

if any component of

$(R_G)_{\mathbf {b}} = 0$

if any component of

![]() $\mathbf {b}$

is negative, we must have either

$\mathbf {b}$

is negative, we must have either

![]() $\mathbf {e}_2 \leq \mathbf {a}$

or

$\mathbf {e}_2 \leq \mathbf {a}$

or

![]() $\mathbf {e}_4 \leq \mathbf {a}$

, where

$\mathbf {e}_4 \leq \mathbf {a}$

, where

![]() $\mathbf {b} = (b_1, \dots , b_5) \leq (a_1, \dots , a_5) = \mathbf {a}$

means that

$\mathbf {b} = (b_1, \dots , b_5) \leq (a_1, \dots , a_5) = \mathbf {a}$

means that

![]() $b_i \leq a_i$

for all i. If u is a linear syzygy, then we have

$b_i \leq a_i$

for all i. If u is a linear syzygy, then we have

![]() $\left \vert \mathbf {a} \right \vert = \sum _i a_i = 2$

, so

$\left \vert \mathbf {a} \right \vert = \sum _i a_i = 2$

, so

![]() $\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_i, \mathbf {e}_4 + \mathbf {e}_j, \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_4$

for some

$\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_i, \mathbf {e}_4 + \mathbf {e}_j, \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_4$

for some

![]() $i \neq 4$

and

$i \neq 4$

and

![]() $j \neq 2$

. In the first case, we have

$j \neq 2$

. In the first case, we have

![]() $u = (\alpha x_i + \beta y_i, 0)$

for some

$u = (\alpha x_i + \beta y_i, 0)$

for some

![]() $\alpha , \beta \in \Bbbk $

, so

$\alpha , \beta \in \Bbbk $

, so

![]() $\partial _1u = 0$

implies

$\partial _1u = 0$

implies

![]() $\alpha x_2x_i + \beta x_2y_i = 0$

. As

$\alpha x_2x_i + \beta x_2y_i = 0$

. As

![]() $x_2x_i$

is part of the monomial basis for

$x_2x_i$

is part of the monomial basis for

![]() $R_G$

, it follows that

$R_G$

, it follows that

![]() $\alpha = 0$

, and so

$\alpha = 0$

, and so

![]() $\beta x_2y_i = 0$

. If

$\beta x_2y_i = 0$

. If

![]() $i \neq 5$

, then

$i \neq 5$

, then

![]() $0 = \beta x_2y_i = \beta x_iy_2$

. In any case, either

$0 = \beta x_2y_i = \beta x_iy_2$

. In any case, either

![]() $x_2y_i$

or

$x_2y_i$

or

![]() $x_iy_2$

is part of the monomial basis for

$x_iy_2$

is part of the monomial basis for

![]() $R_G$

, so

$R_G$

, so

![]() $\beta = 0$

, which contradicts that u is nontrivial. A similar argument shows that there are no nontrivial elements of

$\beta = 0$

, which contradicts that u is nontrivial. A similar argument shows that there are no nontrivial elements of

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _1$

in degree

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _1$

in degree

![]() $\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_4 + \mathbf {e}_j$

for

$\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_4 + \mathbf {e}_j$

for

![]() $j \neq 2$

. However, when

$j \neq 2$

. However, when

![]() $\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_4$

, we see that

$\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_4$

, we see that

![]() $u = (\alpha _1x_4 + \beta _1y_4, \alpha _2x_2 + \beta _2y_2)$

, so

$u = (\alpha _1x_4 + \beta _1y_4, \alpha _2x_2 + \beta _2y_2)$

, so

![]() $\partial _1u = 0$

implies

$\partial _1u = 0$

implies

As

![]() $x_2x_4$

and

$x_2x_4$

and

![]() $x_4y_2$

are part of the monomial basis for

$x_4y_2$

are part of the monomial basis for

![]() $R_G$

, it follows that

$R_G$

, it follows that

![]() $\alpha _2 = -\alpha _1$

and

$\alpha _2 = -\alpha _1$

and

![]() $\beta _2 = -\beta _1,$

so

$\beta _2 = -\beta _1,$

so

$$\begin{align*}u = \alpha_1\begin{pmatrix} x_4 \\ -x_2 \end{pmatrix} + \beta_1\begin{pmatrix} y_4 \\ -y_2 \end{pmatrix}, \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}u = \alpha_1\begin{pmatrix} x_4 \\ -x_2 \end{pmatrix} + \beta_1\begin{pmatrix} y_4 \\ -y_2 \end{pmatrix}, \end{align*}$$

and the columns of the matrix

$$\begin{align*}\partial_2 = \begin{pmatrix} x_4 & y_4 \\ -x_2 & -y_2 \end{pmatrix} \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\partial_2 = \begin{pmatrix} x_4 & y_4 \\ -x_2 & -y_2 \end{pmatrix} \end{align*}$$

are easily seen to generate the linear syzygies of

![]() $\partial _1$

.

$\partial _1$

.

If

![]() $u = (u_1, u_2) \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _2 \subseteq R(-\mathbf {e}_2-\mathbf {e}_4)^2$

is a nonzero homogeneous element of degree

$u = (u_1, u_2) \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _2 \subseteq R(-\mathbf {e}_2-\mathbf {e}_4)^2$

is a nonzero homogeneous element of degree

![]() $\mathbf {a}$

, then

$\mathbf {a}$

, then

![]() $\mathbf {a} \geq \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_4$

. If in addition u is a linear syzygy, then

$\mathbf {a} \geq \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_4$

. If in addition u is a linear syzygy, then

![]() $\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_4 + \mathbf {e}_i$

for some i, so

$\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_4 + \mathbf {e}_i$

for some i, so

![]() $u = (\alpha _1x_i + \beta _1y_i, \alpha _2x_i + \beta _2y_i)$

. Then

$u = (\alpha _1x_i + \beta _1y_i, \alpha _2x_i + \beta _2y_i)$

. Then

![]() $\partial _2u = 0$

implies:

$\partial _2u = 0$

implies:

$$ \begin{align*} 0 &= \alpha_1x_ix_4 + \beta_1x_4y_i + \alpha_2x_iy_4 + \beta_2y_iy_4 \\ 0 &= \alpha_1x_ix_2 + \beta_1x_2y_i + \alpha_2x_iy_2 + \beta_2y_iy_2 \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} 0 &= \alpha_1x_ix_4 + \beta_1x_4y_i + \alpha_2x_iy_4 + \beta_2y_iy_4 \\ 0 &= \alpha_1x_ix_2 + \beta_1x_2y_i + \alpha_2x_iy_2 + \beta_2y_iy_2 \end{align*} $$

As

![]() $x_ix_4$

and

$x_ix_4$

and

![]() $y_iy_4$

are part of the monomial basis for

$y_iy_4$

are part of the monomial basis for

![]() $R_G$

, it follows that

$R_G$

, it follows that

![]() $\alpha _1 = \beta _2 = 0$

, so

$\alpha _1 = \beta _2 = 0$

, so

![]() $\beta _1x_4y_i + \alpha _2x_iy_4 = 0$

and

$\beta _1x_4y_i + \alpha _2x_iy_4 = 0$

and

![]() $\beta _1x_2y_i + \alpha _2x_iy_2 = 0$

. If

$\beta _1x_2y_i + \alpha _2x_iy_2 = 0$

. If

![]() $i = 1, 5$

, then

$i = 1, 5$

, then

![]() $\alpha _2 = \beta _1 = 0$

as well since

$\alpha _2 = \beta _1 = 0$

as well since

![]() $x_4y_1, x_1y_4, x_2y_5$

, and

$x_4y_1, x_1y_4, x_2y_5$

, and

![]() $x_5y_2$

are also part of the monomial basis for

$x_5y_2$

are also part of the monomial basis for

![]() $R_G$

, which contradicts that u is nontrivial. Hence, we must have

$R_G$

, which contradicts that u is nontrivial. Hence, we must have

![]() $i = 2, 3, 4$

, in which case we have

$i = 2, 3, 4$

, in which case we have

![]() $0 = \beta _1x_4y_i + \alpha _2x_iy_4 = (\beta _1 + \alpha _2)x_iy_4 = (\beta _1 + \alpha _2)x_4y_i$

where either

$0 = \beta _1x_4y_i + \alpha _2x_iy_4 = (\beta _1 + \alpha _2)x_iy_4 = (\beta _1 + \alpha _2)x_4y_i$

where either

![]() $x_iy_4$

or

$x_iy_4$

or

![]() $x_4y_i$

is part of the monomial basis for

$x_4y_i$

is part of the monomial basis for

![]() $R_G$

, so

$R_G$

, so

![]() $\alpha _2 = -\beta _1$

. From this, it is easily seen that the columns of the matrix

$\alpha _2 = -\beta _1$

. From this, it is easily seen that the columns of the matrix

$$\begin{align*}\partial_3 = \begin{pmatrix} y_2 & y_4 & y_3 \\ -x_2 & -x_4 & -x_3 \end{pmatrix} \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\partial_3 = \begin{pmatrix} y_2 & y_4 & y_3 \\ -x_2 & -x_4 & -x_3 \end{pmatrix} \end{align*}$$

generate the linear syzygies of

![]() $\partial _2$

.

$\partial _2$

.

Let

![]() $u = (u_1, u_2, u_3) \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _3 \subseteq R(-2\mathbf {e}_2-\mathbf {e}_4) \oplus R(-\mathbf {e}_2-2\mathbf {e}_4) \oplus R(-\mathbf {e}_2-\mathbf {e}_3-\mathbf {e}_4)$

be a nonzero linear syzygy of degree

$u = (u_1, u_2, u_3) \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _3 \subseteq R(-2\mathbf {e}_2-\mathbf {e}_4) \oplus R(-\mathbf {e}_2-2\mathbf {e}_4) \oplus R(-\mathbf {e}_2-\mathbf {e}_3-\mathbf {e}_4)$

be a nonzero linear syzygy of degree

![]() $\mathbf {a}$

. If

$\mathbf {a}$

. If

![]() $\mathbf {a} \ngeq \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_3 + \mathbf {e}_4$

, then

$\mathbf {a} \ngeq \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_3 + \mathbf {e}_4$

, then

![]() $u_3 = 0$

, so

$u_3 = 0$

, so

![]() $(u_2, u_1) \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _1$

and

$(u_2, u_1) \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Ker}} \partial _1$

and

$$\begin{align*}u = \alpha\begin{pmatrix} -x_2 \\ x_4 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \beta\begin{pmatrix} -y_2 \\ y_4 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}u = \alpha\begin{pmatrix} -x_2 \\ x_4 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \beta\begin{pmatrix} -y_2 \\ y_4 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \end{align*}$$

for some

![]() $\alpha , \beta \in \Bbbk $

. So, we may assume that

$\alpha , \beta \in \Bbbk $

. So, we may assume that

![]() $\mathbf {a} \geq \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_3 + \mathbf {e}_4$

, in which case we have either:

$\mathbf {a} \geq \mathbf {e}_2 + \mathbf {e}_3 + \mathbf {e}_4$

, in which case we have either:

-

1.

$\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_2 +\mathbf {e}_3 + \mathbf {e}_4 + \mathbf {e}_i$

for some

$\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_2 +\mathbf {e}_3 + \mathbf {e}_4 + \mathbf {e}_i$

for some

$i \neq 2, 4$

,

$i \neq 2, 4$

, -

2.

$\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_2 +\mathbf {e}_3 + 2\mathbf {e}_4$

, or

$\mathbf {a} = \mathbf {e}_2 +\mathbf {e}_3 + 2\mathbf {e}_4$

, or -

3.

$\mathbf {a} = 2\mathbf {e}_2 +\mathbf {e}_3 + \mathbf {e}_4$

.

$\mathbf {a} = 2\mathbf {e}_2 +\mathbf {e}_3 + \mathbf {e}_4$

.

In case (1), we have

![]() $u = (0, 0, \alpha x_i + \beta y_i)$

for some

$u = (0, 0, \alpha x_i + \beta y_i)$

for some

![]() $\alpha , \beta \in \Bbbk $

, so

$\alpha , \beta \in \Bbbk $

, so

![]() $\partial _3u = 0$

implies

$\partial _3u = 0$

implies

![]() $0 = \alpha x_iy_3 + \beta y_iy_3$

and

$0 = \alpha x_iy_3 + \beta y_iy_3$

and

![]() $0 = \alpha x_ix_3 + \beta y_ix_3$

. As

$0 = \alpha x_ix_3 + \beta y_ix_3$

. As

![]() $x_ix_3$

and

$x_ix_3$

and

![]() $y_iy_3$

are part of the monomial basis for

$y_iy_3$

are part of the monomial basis for

![]() $R_G$

, it follows that

$R_G$

, it follows that

![]() $\alpha = \beta = 0$

, which contradicts that u is nontrivial. In case (2), we have

$\alpha = \beta = 0$

, which contradicts that u is nontrivial. In case (2), we have

![]() $u = (0, \alpha _2x_3 + \beta _2 x_3, \alpha _3x_4 + \beta _3 x_4)$

for some

$u = (0, \alpha _2x_3 + \beta _2 x_3, \alpha _3x_4 + \beta _3 x_4)$

for some

![]() $\alpha _i, \beta _i \in \Bbbk $

. Then

$\alpha _i, \beta _i \in \Bbbk $

. Then

![]() $\partial _3u = 0$

implies

$\partial _3u = 0$

implies

As

![]() $x_4y_3$

and

$x_4y_3$

and

![]() $y_3y_4$

are part of the monomial basis for

$y_3y_4$

are part of the monomial basis for

![]() $R_G$

, we see that

$R_G$

, we see that

![]() $\alpha _3 = -\alpha _2$

and

$\alpha _3 = -\alpha _2$

and

![]() $\beta _3 = -\beta _2$

, so

$\beta _3 = -\beta _2$

, so

$$\begin{align*}u = \alpha_2\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ x_3 \\ -x_4 \end{pmatrix} + \beta_2\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ y_3 \\ -y_4 \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}u = \alpha_2\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ x_3 \\ -x_4 \end{pmatrix} + \beta_2\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ y_3 \\ -y_4 \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

By a similar argument applied to case (3), we see that the columns of the matrix

$$\begin{align*}\partial_4 = \begin{pmatrix} -x_2 & -y_2 & x_3 & y_3 & 0 & 0 \\ x_4 & y_4 & 0 & 0 & x_3 & y_3 \\ 0 & 0 & -x_2 & -y_2 & -x_4 & -y_4 \end{pmatrix} \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\partial_4 = \begin{pmatrix} -x_2 & -y_2 & x_3 & y_3 & 0 & 0 \\ x_4 & y_4 & 0 & 0 & x_3 & y_3 \\ 0 & 0 & -x_2 & -y_2 & -x_4 & -y_4 \end{pmatrix} \end{align*}$$

generate the linear syzygies of

![]() $\partial _3$

.

$\partial _3$

.

Finally, we observe that

![]() $x_3f_{1,5} = x_1f_{3,5} + x_5f_{1,3} \in J_G$

and similarly that

$x_3f_{1,5} = x_1f_{3,5} + x_5f_{1,3} \in J_G$

and similarly that

![]() $y_3f_{1,5} \in J_G$

, so

$y_3f_{1,5} \in J_G$

, so

![]() $q = (0, 0, f_{1,5})$

is a quadratic syzygy of

$q = (0, 0, f_{1,5})$

is a quadratic syzygy of

![]() $\partial _3$

. If q is a nonminimal syzygy, the above description of the linear syzygies of

$\partial _3$

. If q is a nonminimal syzygy, the above description of the linear syzygies of

![]() $\partial _3$

implies that

$\partial _3$

implies that

![]() $f_{1,5} \in J_G + (x_2, y_2, x_4, y_4)$

, which is easily seen to imply that

$f_{1,5} \in J_G + (x_2, y_2, x_4, y_4)$

, which is easily seen to imply that

![]() $f_{1,5} \in J_P$

where P is the induced path of G on the vertices

$f_{1,5} \in J_P$

where P is the induced path of G on the vertices

![]() $\{1,3, 5\}$