Introduction

The story of Scott and his Terra Nova Expedition has been told many times. From those narratives, there is no doubt that the shortage of heating and cooking fuel was a major factor in the demise of the Polar Party. Possible explanations for Scott’s fuel shortages have been advanced ever since the expedition’s return in 1913; explanations such as damaged fuel cans, failed solder joints, faulty washers, “fuel creep” and theft by expedition members.

A common characteristic of such narratives is the absence of verifiable evidence or eyewitness accounts that properly explain the cause(s) of fuel shortages at Scott’s crucial depots. These technical explanations are later reconstructions, not firsthand observations recorded in the field by the members of Scott’s returning Polar Party. Later, secondary analyses provide theoretical explanations, some based on prior polar experience, but do not tie these directly to Scott’s depot conditions.

An important gap, therefore, exists in our understanding of the cause(s) of Scott’s demise. The principal objective of this article is to establish an evidence-based explanation for the cause(s) of Scott’s fuel shortages, an explanation tied to and consistent with contemporaneous expedition records.

This article uses Robert Falcon Scott’s Journals by Max Jones as the source of all quotations from Scott’s journals. It is cited herein as (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006) and has three advantages over older versions of Scott’s journals (a) allows the reader to distinguish between Scott’s original text (verified by Jones against Scott’s handwritten sledging journals) and Editor Leonard Huxley’s changes to Scott’s text, (b) is readily available and, (c) is available in digital format which enables rapid and accurate searching for Scott’s own words and phrases.

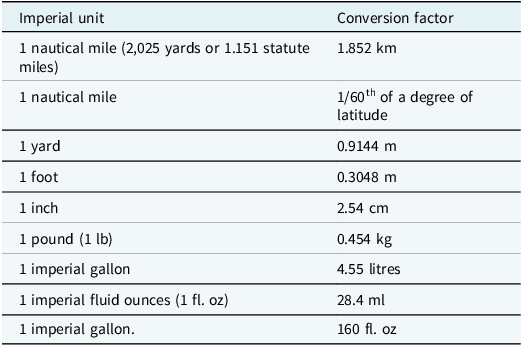

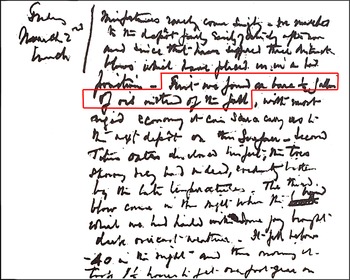

Scott and his men used imperial units of measure. These have not been converted to metric units, as that would break up the story. Except if mentioned in the original text, all mileages are given in geographical (nautical) miles. Table 1 provides metric conversion factors for Scott’s units of measure.

Table 1. Units of measure

Reports of kerosene shortage and leakage

This article uses the international term “kerosene” when describing its physical properties (such as freezing temperature, vapour pressure etc.), its packaging and its transportation. The term “fuel” is used where kerosene is destined for cooking or lighting purposes. Scott and his men referred to kerosene by several names, including “fuel,” “kerosene,” “oil” and “paraffin” (a term common in the UK). Text searches indicate that Scott used all four terms in his journals – over half being “fuel,” with “oil” next most popular.

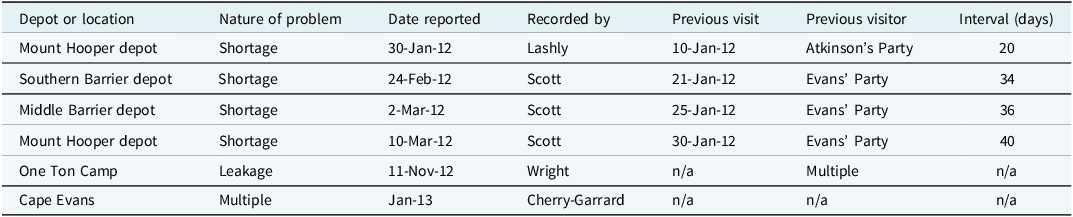

A literature review has revealed only six instances of kerosene shortage and leakage being reported during the entire Terra Nova Expedition, as listed in Table 2. There may have been unreported shortages that cannot be assessed in this article. The first four items in Table 2 were recorded in a six-week period in the 1911–12 season, at consecutive depots along the southern route, while the other two instances were noted in the following season and have quite different characteristics from the first four.

Table 2. Reported instances of kerosene shortage and leakage

Twelve depots were established along the southern route, where food, kerosene and other provisions and equipment were placed prior to and during the Southern Journey. The twelve depots were (from north to south): Corner Camp, Bluff Depot, One Ton Camp, Upper Barrier Depot (also called Mount Hooper), Middle Barrier Depot, Southern Barrier Depot, Lower Glacier Depot, Middle Glacier Depot, Upper Glacier Depot, 3 Degree Depot, 1½ Degree Depot and Last (also called Half Degree) Depot. Cherry-Garrard’s sketch of the southern route (Fig. 1) shows the approximate locations. Exact geographic coordinates are included in the text.

Figure 1. The southern route, showing all depots. Diagram from The Worst Journey in the World by Cherry-Garrard.

The shortages of fuel that ruined the Polar Party’s prospect of survival (the first four items in Table 2) were not randomly distributed along the route – they were reported at only three consecutive depots in the third quarter of the return route, at depot numbers six, five and four, out of twelve. These depots were at Ross Ice Shelf (“the Barrier”) altitude, much lower than depots on the Beardmore Glacier (“the Glacier”) and the Polar Plateau. They were much closer to base than the southernmost depots and therefore at lower risk of physical damage to cans during transportation.

Intended fuel ration for the Southern Journey

Scott’s Discovery Expedition of 1901–1904 had a fuel allowance of one gallon per three-man party per ten days (Scott, 1905/Reference Scott2009, p. 306).

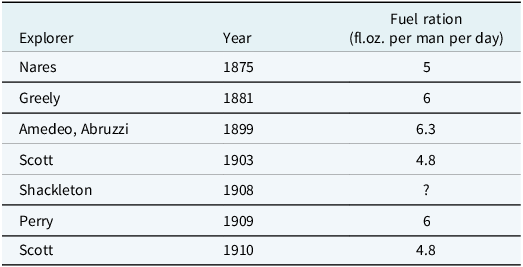

In May 1911, Bowers undertook a literature review of books in the expedition’s Cape Evans library, tabulating the food and fuel rations for as many Arctic and Antarctic expeditions as practicable. The resulting table Sledging Allowances. Arctic and Antarctic was published with many of Scott’s other Cape Evans papers in what later became known as the “Facsimile Journals, volume III” (Scott, Reference Scott1911b). The author transcribed Bowers’ information into Table 3 without further verification.

Table 3. Daily fuel allowance on polar expeditions

From the fuel allowance of Scott’s Discovery Expedition (Table 3), ten days’ fuel for a three-man party equals 4.8 fl. oz. x 10 days x 3 men = 144 fl. oz. = 90% of one imperial gallon. Bowers may have included a margin of 10% for wastage or as a contingency measure.

Table 3 indicates that in May 1911, after completing the Depot Journey, Scott intended to stick with 4.8 fl. oz. per man per day. However, a few months later, his 13 September 1911 Southern Journey plans indicate a revised allowance of one gallon of fuel per four-man party per week. His Facsimile Journals, volume III, include a page headed “Sledging Rations” (Scott, Reference Scott1911b), with the left-hand column headed “weekly for 4 men” and a row “Fuel 1 gall. 8.5 lbs.” The daily allowance would, therefore, become 160 fl. oz./4 men/7 days = 5.7 fl. oz. per man per day. This allowance, albeit mid-field amongst the other expeditions reviewed by Bowers, represents an increase over the initial 4.8 fl.oz.

Scott’s standard depot provisioning pattern became one gallon of fuel per ration unit (a wooden box containing pemmican, butter, sugar, salt, tea, etc., sufficient to sustain four men for one week). There are several instances in Scott’s plans where a ratio of one gallon of fuel to one ration unit is evident. The Pony Party’s southern journey (one-way) had 14 gallons of fuel to 14 ration units (Wilson, Reference Wilson1911, pp. 34). The Glacier and Summit allowance for southern parties (return) had 18 gallons of fuel to 18 ration units (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard2010, p. 365).

As noted in Scott’s changes to the plan (below), Scott later reduced the fuel allowance at several barrier depots to only two-thirds of a gallon per week per four-man party, with dire consequences.

Suitability of Terra Nova cans and kerosene

The kerosene cans used on Scott’s earlier Discovery Expedition had proved unsatisfactory. Scott later wrote:

Each tin had a small cork bung, which was a decided weakness […] It was impossible to make these bungs quite tight, however closely they were jammed down, so that in spite of a trifling extra weight a much better fitting would have been a metallic screwed bung. (Scott, 1905/Reference Scott2009, p. 306)

Regular mass-produced one-gallon automotive petrol cans were used on the Terra Nova Expedition. These cans (Fig. 2) and their contents were supplied by Shell Oil in Melbourne, Australia. The Shell cans proved wholly satisfactory for the Terra Nova Expedition. No problems were reported with metal components (e.g. no solder failures, no ruptured panels, no failure of screw caps to remain tight etc.). The weakest part was claimed by some to be the leather washer between the cap and spout, said to deteriorate and become brittle in extreme cold. No loss from unopened Terra Nova cans was reported when travelling over uneven terrain, unlike the Discovery Expedition. The caps had castellated lugs (see Fig. 3). They were loosened and tightened by using any handy object as a lever, thereby ensuring they were tighter than “finger tight.” Small holes in the lugs were possibly for customs excise sealing as the kerosene was exported from Australia.

Figure 2. Terra Nova Expedition kerosene can. Image courtesy of Antarctic Heritage Trust, AHT12342.1.

Figure 3. Kerosene can cap as used on the Terra Nova Expedition. Image courtesy of David Harrowfield.

The expedition’s Scientific Committee later noted, “The oil used was a paraffin with a very low flash point. It withstood freezing temperatures of 77 deg. F.; below - 60 deg. F., however, it became slightly opalescent and thick” (Lyons, Reference Lyons1924, p. 31). There were no reports of opalescence causing any problems.

Chemically, kerosene is a mixture of hydrocarbons. Alkanes and naphthenes together make up about 70% of its composition, while the rest is largely made up of alkylbenzenes and alkyl naphthalenes, according to a quick online search. Its vapour pressure is around 0.7 Kilopascals (“kPa”), indicating a very low evaporation rate. Density is in the range of 0.78–0.81 g per cc.

Food rations

This article does not investigate the adequacy of food rations consumed by Scott and his men on their Southern Journey in 1911–12, because it is already well documented that the food rations were inadequate for the work being undertaken. For example, Ranulph Fiennes explained that Scott’s daily summit ration of about 4500 calories per day should have been at least 7000 calories per day (Fiennes, Reference Fiennes2003, pp. 283–285).

Food and fuel rations were always stored in the same depots along the southern route; so, journal entries about fuel usually mention food. In fact, food was mentioned more frequently, particularly as the men became weakened by hunger, dehydration and exposure in the later stages of the Southern Journey.

Scott was proud of the food ration chosen after the dietary experiments conducted during the Winter Journey by Doctor Edward “Bill” Wilson, Lieutenant Henry “Birdie” Bowers and Apsley “Cherry” Cherry-Garrard (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 259). Initially, he saw no need to supplement that ration with meat from ponies taken on the Southern Journey. Scott did not take any pony meat beyond the point where animals were slaughtered, relying solely on his ration units. The only exception was when Lieutenant Edward “Teddy” Evans secretly took a large piece of pony meat south, which was incorporated into in the communal Christmas Dinner (“Recollections of a gallant comrade”, 1913).

Scott planned the supply logistics of the Southern Journey carefully. He was able to maintain the intended food ration throughout, apart from a few days in each direction on the Glacier. The consequence of relying solely on a diet deficient in energy content and essential vitamins was that the men were effectively on a starvation diet.

Historic comments about fuel shortages

The first comment recorded in an expedition member’s journal was Frederick (“Percy”) Hooper’s, written on 11 November 1912. That was the day the Search Party reached One Ton Camp, one day before finding the Polar Party:

The depot that was laid here by Garrard last March for the Pole Party was absolutely covered with paraffin. Apparently, he left Hut Point with 2 XS Rations covered with paraffin, being dark at Hut Point he could not see whether they were alright or not. It also ruined the other food that was left here by Day, Nelson & Clissold & myself in Jan. (Hooper, Reference Hooper1912, p. 4)

Other members of the Search Party noted the problem but Hooper was the only one to blame Cherry-Garrard for spillage at One Ton Depot. Hooper’s opinion that cans were already leaking at Hut Point was not adopted by other expedition members or subsequent writers. Nonetheless, it was the first comment on the subject.

The first recorded explanation by an expedition committee member was by Lord George Curzon on 16 April 1913, in a private note (Curzon, Reference Curzon1913), written after meeting with Kathleen Scott and after reading Scott’s journals. Curzon wrote:

Words in his [Scott’s] Diary on exhaustion of food & fuel in depots on his return. He spoke in reference to “lack of thoughtfulness & even of generosity” It appears Lieut Evans – down with scurvy – and the two men with him must on return journey have entered & consumed more than their share.

Scott’s exact words were “Yesterday we marched up the depot, Mt. Hooper. Cold comfort. Shortage on our allowance all round. I don’t know that anyone is to blame but generosity and thoughtfulness have not been abundant” (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, pp. 408, 471). Curzon seemingly interpreted Scott’s words to mean that Evans, Crean and Lashly had consumed food and used fuel beyond their entitlement, thereby contributing to the demise of the Polar Party.

Modern explanations for Scott’s fuel shortages

The intriguing subject of Scott’s fuel shortages has been studied by many researchers and writers. This section considers explanations that have been proposed, plus a new one: Explanation 5. The explanations are not mutually exclusive and could conceptually overlap in different ways. However, we have insufficient evidence to know whether any overlap occurred at Scott’s last three depots. This section does not choose between explanations, simply laying each one out and commenting on its likelihood.

Explanation 1: Fuel creep

A literature search indicates “fuel creep” originated in Scott’s book, The Voyage of the Discovery, where he wrote:

Each tin had a small cork bung, which was a decided weakness; paraffin creeps in the most annoying manner, and a good deal of oil was wasted in this way, especially when the sledges were travelling over rough ground and were shaken or, as frequently happened, capsized. (Scott, 1905/Reference Scott2009, p. 306).

Scott was writing about kerosene cans on sledges in motion over uneven surfaces. The contents would be sloshing around inside the cans, keeping all interior surfaces wet. The bottoms of the stoppers would be more or less permanently wet while the sledge was in motion. This is when capillary action can occur.

Capillary action occurs when liquid flows through narrow spaces without the aid of external forces, such as gravity. Rather, the liquid’s movement is aided by intermolecular forces present between the liquid and a solid surface. Capillary action is well understood, behaving in accordance with the laws of physical chemistry. Capillary action would transfer liquid kerosene from the bottom of the wet stopper (inside the can) to the top of the spout (outside the can). This would be a genuine case of kerosene loss. When the sloshing stopped, the bottom of the stopper would receive no more liquid, and the capillary action would soon stop. In addition to capillary action, Scott may also have lost kerosene on the Discovery Expedition by direct leakage when sledges capsized.

If Terra Nova Shell cans with their metal screw caps and leather washers had suffered from fuel creep while in motion across the Barrier, this would have been evident to the men, both by sight and by the smell of kerosene. Kerosene was carried on Nansen sledges using a board made of venesta or ply board laid on the sledge, where escaped liquid would be visible. Nothing like this was reported, indicating an effective airtight seal existed below the caps of the Shell cans. If the leather washer of a Terra Nova can become damaged to the extent that the airtight seal was damaged (either at its first opening or later), then fuel creep could occur when the can was subsequently transported by sledge.

Cherry-Garrard recounted that some cans had lost kerosene over a long period while under a snowdrift at Cape Evans (last line in Table 2) cannot be treated as fuel creep because the cans were motionless. Likewise, cans could not have suffered from fuel creep while stored in barrier depots for the same reason.

Explanation 2: Evaporation

The explanation of “evaporation” was proposed by Cherry-Garrard and Doctor Edward “Atch” Atkinson in their written works after the return of the Terra Nova Expedition. For kerosene to escape from a can by evaporation, the can cannot be airtight – the airtight seal must have already been damaged.

A scientific measure for evaporation of a liquid in a vessel is its “vapour pressure” – the pressure exerted by the gas above the liquid in a sealed container at a certain temperature. Compounds with strong intermolecular forces produce a lower rate of evaporation and have a lower vapour pressure. Compounds with weak intermolecular forces produce a higher rate of evaporation and have a higher vapour pressure. Vapour pressure is measured in kilopascal (kPa). Kerosene has a vapour pressure of approximately 0.7 kPa at 20° Celsius, which is very low. In comparison, water has a vapour pressure of 2.4 kPa at 20° Celsius, while the methylated spirits used to start Scott’s Primus cookers had a vapour pressure of about 16.9 kPa at 20° Celsius. This is a huge difference, indicating that kerosene evaporation is extremely slow at 20° Celsius and even slower at Antarctic temperatures.

Table 2 shows the interval between cans being first opened (potentially damaging the airtight seal) and when the shortage was reported. The period varies from 20 to 40 days. The amount of evaporation that could have occurred in that short period, at Antarctic temperatures, would be minimal. Anecdotally, in a temperate climate, after two months in a one-litre plastic container with an extremely loose cap, kerosene evaporation took the fluid level down by about one millimetre (pers. obs.).

It is apparent that evaporation would not have been a significant contributor to fuel shortages in Scott’s depots – its effect was, at most, minimal.

Explanation 3: Failure of solder

Conceptually, soldered seams could be the weakest part of any fuel can. However, a literature search for eyewitness accounts during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration did not reveal any record of solder failure in kerosene cans or in other equipment with soldered seams, such as Primus cooker tanks. The literature search covered all expeditions led by Scott, Shackleton, Amundsen and Mawson. The literature search found that Amundsen was almost obsessive about soldered seams. Apparently, his team often re-soldered seams in case of unexpected failures. He used large 17 litre cans whereas the other expeditions used smaller one-gallon (4.5 litre) cans. Amundsen’s cans, being almost four times heavier than the others’, were presumably at greater risk of damage from rough handling, as it is unlikely they would have been four times stronger. Amundsen wrote, “We kept it in the usual cans, but they proved too weak; not that we lost any paraffin, but Bjaaland had to be constantly soldering to keep them tight” (Amundsen, Reference Amundsen2001, Vol. 2, p. 19).

There is no eyewitness evidence that the failure of soldered seams ever occurred or caused leakage of kerosene in Scott’s Terra Nova depots.

Explanation 4: Solar gain

An unusual assertion appears in Editor’s Note 26 of the expedition’s official book, published on 6 November 1913. The full text of Note 26 is included as Appendix I for ease of reference.

It suggests:

The oil was specially [sic] volatile, and in the warmth of the sun (for the tins were regularly [emphasis added] set in an accessible place on the top of the cairns) tended to become vapour and escape through the stoppers even without damage to the tins (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 442).

However, a search of expedition journals reveals only one eyewitness account of a kerosene can being placed or observed on top of any depot cairn (a unique situation addressed in Explanation 6 below). A wide search for a photograph or a sketch of a can atop a depot cairn has been unsuccessful. Dr. David Wilson is undertaking a huge project, Terra Nova Illustrated: Pictures from Captain Scott’s Last Antarctic Expedition 1910–1913, covering all photographs and sketches he can find – “in the thousands” he says. Dr. Wilson has not seen a single photograph or sketch of a can atop a depot cairn.

The cairns were marked by larger red or black flags on bamboo poles. Several men recorded great relief upon sighting the flag of the depot they had been seeking. A literature search found no instances where anybody reported seeing a kerosene can as they approached a depot. Bowers was the “depot maker” of the expedition, providing a lot of useful detail in his sledging journal about the depots he established. Nowhere in those details is there any mention of cans being placed on top. The only recorded instance of cans being placed atop a cairn is Cherry-Garrard’s own rebuilding of One Ton in March 1912: “the oil was placed on the top of the snow, in order that the red tins might prove an additional mark for the depot” (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard2010, pp. 569–570). This appears to have been an isolated incident.

Kerosene is not “specially volatile” as asserted; it has low volatility, as noted in the suitability of Terra Nova cans and kerosene (above). In summary, the assertion that Terra Nova kerosene cans were regularly placed on top of depot cairns is unverified and unlikely to be true. However, the absence of evidence is not absolute proof that an event never occurred – counter-evidence could possibly be discovered in the future.

Explanation 5: Dual meaning of “shortage”

Examination of Scott’s Terra Nova sledging journals reveals that Scott himself only referred to fuel “shortages,” he never referred to “evaporation” or “creep” or “leakage” or “loss” of fuel. The word “shortage” literally means a situation in which something needed cannot be obtained in sufficient amounts. For provisions in a depot, two possibilities exist (1) the amount in the depot is less than it should have been i.e. “depot depletion”; or (2) the amount required now exceeds the amount initially placed in the depot i.e. “increased need.”

Early investigations of Scott’s fuel shortages (e.g. those by Curzon, Huxley and Cherry-Garrard) focused on possibility (1), leading them to write about the possible reasons for fuel depletion at Scott’s last three depots. Surprisingly, nobody appears to have investigated possibility (2), despite several significant pieces of direct evidence that indicate insufficient fuel was provided for the Polar Party at three barrier depots on the return journey. Scott, in a late reorganisation, reduced their ration from 1 gallon of kerosene per depot to two–thirds of a gallon per depot, as described in Scott’s changes to the plan (below). This under-provisioning was exacerbated by the Polar Party travelling more slowly over later Barrier stages than planned, meaning that each can of fuel had to last several days longer than planned. The weather as they returned across the Barrier was much colder than expected, requiring more fuel than planned to melt ice for drinking water and to cook food. They had a substantial quantity of pony meat to eat but had not brought fuel to cook it, necessitating more unplanned usage of fuel.

The evidence supporting the first four explanations (fuel creep, evaporation, failure of solder or solar gain – the “depot depletion” explanations) appears unconvincing when compared against solid evidence of “increased need.”

Explanation 6: Leakage at one ton camp

The Search Party found a unique instance of fuel leakage at One Ton in November 1912 (Wright, Reference Wright, Bull and Wright1993, p. 343). It is the only instance where liquid kerosene contaminated provisions in the depot and left a strong odour. All other instances appear to have been contamination-free and odourless. Despite this depot having been opened and rebuilt by several parties passing through in both directions, no problems were reported until after Cherry-Garrard’s visit with the dog teams in March 1912. He rebuilt the depot after failing to meet up with the Polar Party, the first time he had ever rebuilt a depot. He placed cans atop the depot cairn, “the oil was placed on the top of the snow” (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard2010, pp. 569–570), perhaps expecting Scott to retrieve them in a few days. However, when the Search Party arrived eight months later, strong winds had ablated the supporting snow, causing cans to fall off the cairn. Previously opened cans with damaged washers, which landed on their side, could then leak a significant quantity of kerosene at the surface level.

In any event, this was not actually a shortfall (there was still ample kerosene in the depot, which the Polar Party never reached), and it did not contribute to their demise.

Explanation 7: Kerosene loss at Cape Evans

The loss of kerosene at Cape Evans (last line of Table 2) is also a unique instance, first recorded by Cherry-Garrard on-board ship while returning to New Zealand:

I think that I have not mentioned one or two items of past news: first, that Demetrie at Cape Evans dug up the C. Crozier Depot which was left at C. Evans for the ship to take, and which was made up at the same time as our Southern Journey Rations. There were 8 tins of oil – one was quite empty, two were only two-thirds full, the rest were full. This may be important. (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard1913a, 27 January 1913)

Cherry-Garrard’s text is notably lacking in detail, raising several doubts about its completeness and accuracy. It seems unusual for Demetrie (a dog handler) to dig up a kerosene depot – no information is provided about who asked him to do it, and why. Given its possible importance in explaining Scott’s fuel shortages, it is surprising that supporting details such as the date of excavation, the reason for excavation and intended use of the kerosene were not recorded. No independent eyewitness accounts have been discovered, and no corroborating evidence can be found. Editor’s Note 26 of the expedition’s official book tells the same tale, but with significant discrepancies in the quantity of kerosene lost, “three tins full, three empty, one a third full and one two–thirds full” (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 442). This version of the tale is credited, in Note 26, to Atkinson.

In any event, the loss of kerosene reported at Cape Evans (which the Polar Party did not reach) did not contribute to their demise.

Teddy Evans’ folly

Scott’s October 1911 instructions for the Motor Party covered the possibility of breakdowns, “If motors break down irretrievably, take 5 weeks’ provision and 3 gallons extra summit oil on 10-foot sledge and continue south easy marches” (Evans, Reference Evans1961, p. 143).

The second motor failed on 1 November 1911, and Evans wrote:

Arrived at this important depot [Corner Camp] we deposited the dog pemmican and took on three sacks of oats, but after proceeding under motor power for 1½ miles, the big end brass of No. 1 cylinder went, so we discarded the car and slogged on foot with a six weeks’ food supply for one 4-man unit. Our actual weights were 185 lb. per man (p. 172).

Evans was assertive, dominant and a natural leader – an archetypal “alpha male.” He did not follow Scott’s instructions in this instance, taking six ration units (63.4 pounds each) instead of the five specified by Scott, and he did not take the requisite three cans of kerosene (10 pounds each). Evans may have decided to exceed Scott’s expectations by taking a greater load at a faster pace than instructed, “I was very proud of the Motor Party, and determined that they should not be overtaken by the ponies to become a drag on the main body” (p. 173). Scott’s farewell letter to Joseph Kinsey (the expedition’s New Zealand Agent) from the death tent commented, “Teddy Evans is not to be trusted over much though he means well” (Scott, Reference Scott1911d). This sentence was redacted by Editor Huxley from the expedition book (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 418).

Wright later reported during the Search Journey “3 tins oil in drum” were found with the second failed motor (Wright, Reference Wright, Bull and Wright1993, p. 328). Perhaps, these were the “three gallons extra summit oil” Evans had been instructed to take south. The three gallons of kerosene Evans left behind were essential items, and their abandonment had serious logistical consequences as noted in the next section.

Scott’s changes to the plan

Scott’s original plans for the Southern Journey had only one depot on the Barrier south of One Ton Camp. Cherry-Garrard’s noted at Scott’s 13 September 1911 presentation, “At 82° 30’ S. a depot. Two weeks of food and fuel for all returning parties” (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard1913b, p. 298). Wilson and Oates both noted at the same presentation, “It will be possible to leave hereabouts [latitude 82½° south] 2 weeks food and fuel for return = 422 pounds” (Wilson, Reference Wilson1911, p. 7; Oates, Reference Oates1911, p. 5). A weekly food ration (B Unit) for one party weighed 60.4 pounds and one gallon of fuel with packaging weighed ten pounds. Two weeks’ worth for three parties would weigh 422.4 pounds. Two weeks’ worth of fuel and food were to be uplifted by each of the three returning parties at 82½° south to sustain four men on their journey back to One Ton, at 79½° south.

However, the depot at 82½° south was never established. Instead, three smaller depots were built: Upper Barrier, Middle Barrier and Southern Barrier. Something significant must have occurred to change Scott’s scheme between his 13 September 1911 presentation and 21 November 1911, when the first new depot was laid beside Evans’ Mount Hooper cairn. Upon reaching One Ton on 15 November 1911, Scott declared the following day a rest day. He held a “council of war” meeting during which some important changes to pony fodder management were agreed (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard2010, p. 338). To reduce pony loads, it was decided pony fodder for the ascent of the Glacier would be left at One Ton. A plan for progressive slaughter of ponies was settled, allowing a further reduction of pony fodder. Scott called another “council of war” meeting on 17 November 1911, where it was decided ponies would be underfed for their last few days of life, allowing another hundred pounds of pony fodder to be dumped immediately (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard2010, p. 343).

Around this time, Scott decided to have three barrier depots south of One Ton, rather than the single 422-pound depot at 82½° south. That change would allow pony loads to be reduced as each new depot was established, rather than hauling the entire 422 pounds to 82½° south.

Three depots for three returning parties would require nine ration units and nine gallons of kerosene, but there were only six of each assigned to the proposed 82½° south depot. He knew from Evans’ note at One Ton that six additional ration units were being brought south, but there was no certainty about additional fuel. If there were no spare cans available, then there could be only two cans per depot, to be shared between three parties. This was a risky change as it was not normal practice for cans to be shared between parties (e.g. the Dog Party had to carry their own fuel and ration units, as did the Motor Party).

Ultimately, only two cans were provided at each of the three barrier depots.

Scott’s Southern journey

Establishing the Mount Hooper depot

The new fuel allowance pattern was first implemented on 21 November 1911, with the depot constructed at 80° 32’ south, alongside the Mount Hooper cairn. Scott was preoccupied at this time with concerns about the ponies so, as usual, he left the depot work to Bowers. However, Scott did briefly instruct Evans about what his party needed to contribute to the new depot and what to hand over to Bowers for redistribution to other parties, reducing the workload on Evans’ gaunt and undernourished team (Evans, Reference Evans1961, p. 178). Evans recorded a reduction of one ration unit (62 pounds) two biscuit boxes (42 or 44 pounds each) and three gallons of fuel (ten pounds each). That was a net reduction of at least 170 pounds from their cargo of around 750 pounds at the time. Bowers was an excellent record keeper, with an eye for detail. He was proficient at allocating and redistributing sledge loads. With Scott’s “naval convoy” transportation model, it was essential for all units to travel the same daily mileage and then camp together, requiring occasional readjustment of loads so tail end units did not drop behind. Scott had faith in Bowers:

I leave all the provision arrangement in his [Bowers] hands and at all times he knows exactly how we stand, or how each returning party should fare. It has been a complicated business to redistribute stores at various stages of reorganisation, but not one single mistake has been made (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, pp. 369–370).

Scott recorded nothing about the establishment of Mount Hooper depot. Bowers wrote:

At this spot (80° 32’ S) Evans had erected a massive cairn […] I depoted here 3 ‘S’ rations with 2 cases of ‘Emergency’ Biscuit & 2 cans of oil which constitutes 3 weekly food units for our 3 returning parties. […] A week’s food for 4 men (‘B’) rations was also left for Day’s return to Bluff Camp Depot where he will pick up his next rations for returning to Hut Point. (Bowers, Reference Bowers1912, 21 November 1911).

Cherry-Garrard’s memoir confirms the detail of what was left in the Mount Hooper depot, as well as its purpose:

The cairn was in 80° 32´, and under the name Mount Hooper formed our Upper Barrier Depot. We left there three S (Summit) rations, two cases of emergency biscuits and two cases of oil, which constituted three weekly food units for the three parties which were to advance from the bottom of the Beardmore Glacier. This food was to take them back from 80° 32´ to One Ton Camp. (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard2010, p. 344)

The Mount Hooper fuel-allowance pattern was continued for another three depots southwards (Middle Barrier, Southern Barrier and Lower Glacier) after which the standard pattern was resumed, with one gallon of fuel per ration unit.

Establishing more barrier depots to the south

Bowers recorded the establishment of the next depot, Middle Barrier (at 81° 35’ south) on 26 November 1911. This depot also had two gallons of fuel and three ration units for the three parties “We left 3 S. rations (pemmican, sugar, butter, tea and cocoa), 2 cases emergency biscuits, 2 cases oil (2 gallons) 1 tin salt, 3 boxes of matches and a packet of toilet paper.” (Bowers, Reference Bowers1912, 26 November 1911).

It is not widely known that exceptionally warm weather prevailed during several stages of the Southern Journey, particularly the latter part of the southward march across the Barrier and returning down the Glacier. An article published by the American Meteorological Society (Fogt et al., Reference Fogt, Jones, Solomon, Jones and Goergens2017, p. 2189) found “The race for the South Pole during the summer of 1911–12 was marked by exceptionally high temperature and pressure anomalies experienced by both Amundsen and Scott.” Exposure to below-average temperatures did not begin until late February 1912. Bowers recorded the establishment of the next depot, Southern Barrier (at 82° 47’ south) on 1 December 1911:

I have made our last Barrier Depot here, called the Southern Barrier Depot. It contains 3 S weekly units, 2 cans of oil and two cases of emergency biscuits as well as a 12 ft. sledge and a tank of dog biscuits (Bowers, Reference Bowers1912, 1 December 1911)

A four-day blizzard was experienced near the foot of the Glacier, from 5 December to 8 December 1911, with men being tent-bound for the duration. Because of pony limitations, and despite regular reviews to reduce pony loads, they had barely kept up with Scott’s tough schedule, which was based upon Shackleton’s daily mileage along the same route three years earlier. The unplanned delay of four days was most unwelcome at this stage, with 14 men to be fed. This reduced the amount of food and fuel available for the Glacier and Polar Summit stages by about two ration units and two gallons respectively.

Struggling up the Glacier

The next depot was Lower Glacier (at 83° 35’ south), established on 11 December 1911. Bowers was suffering from snow blindness at the time and wrote on 14 December 1911 after recovering:

On the 11th, we got the depot made. I depoted three south units of provisions, 2 cases of emergency biscuits (84 lbs) and 2 cans of oil for returning parties to last us as far as the Southern Glacier [sic] [Southern Barrier] Depot. Also, 1 can of spirits for lighting purposes (Bowers, Reference Bowers1912, 14 December 1911).

Upon leaving the depot, the three sledges carried all provisions available for ascending the Glacier, traversing the Polar Summit to the South Pole and returning back to Lower Glacier Depot. Eighteen ration units and eighteen gallons of fuel were taken southwards, reverting to the normal ratio of 1:1. Bowers wrote:

We stowed our three tanks [i.e. one per sledge] with 6 south units each besides 3 ready bags, the complement of biscuits being 10 cases in addition to the 3 ready boxes and 18 cans of oil with 2 cans of lighting spirit completed the stores for the rest of the journey (Bowers, Reference Bowers1912, 14 December 1911)

The next depot, Middle Glacier, approximately half way up the Glacier, was established on 18 December 1911. Its precise location is unknown: “we got no cross-bearing on prominent peaks to fix its position, although its position was known to be upstream from the Cloudmaker on our right” (Wright, Reference Wright, Bull and Wright1993, p. 220). Bowers recorded “It consisted of 3 half weekly S. units and a half weekly allowance of biscuits and oil for three parties viz. 42 lbs of biscuits and one gallon of oil” (Bowers, Reference Bowers1912, 18 December 1911)

On 21 December 1911, at 85° 7’ south, the first returning party, comprising Atkinson, Cherry-Garrard, Wright and Keohane was instructed to return to base. Over the next month or so, they would travel back to One Ton, uplifting their ration units and decanting their two-thirds of a gallon of fuel at the three southernmost barrier depots. From One Ton back to Cape Evans, they would rely on the new XS ration unit and full can of fuel brought out to One Ton for the three returning parties by a man hauling party.

The next depot was Upper Glacier at 85° 07’, established on 22 December 1911. Bowers did not record precise details of provisions stored there “I rigged up the Upper Glacier Depot after breakfast. We depoted two half weekly units for return of the two parties …” (Bowers, Reference Bowers1912, 22 December 1911).

Although Scott had written on 16 December 1911, “We must push on all we can, for we are now 6 days behind Shackleton, all due to that wretched storm” (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 351), by 30 December 1911 he was able to write, “We have caught up Shackleton’s dates” (p. 363). The next depot, Three Degree, (at 86° 56’ south) was established on 31 December 1911. Scott wrote, “This is to be called the “3 Degree Depot,” and it holds a week’s provision for both units” (p. 364) without mentioning the amount of fuel left there – not surprising as Scott seldom wrote about fuel.

A fifth man shall go to the Pole

An important decision was made three days later, with Scott announcing on 3 January 1912 (at 87° 32’ south) that five men would go to the Pole, instead of the planned four. This decision had been made the evening before “last night I decided to reorganise” (p. 365). The five men were Scott, Wilson, Captain Lawrence “Titus” Oates, Bowers (without skis) and Edgar “Taff” Evans. If Scott had made this decision a few days earlier, Bowers could have taken skis, which had been left at the previous depot for unknown reasons. Teddy Evans, Crean and Lashly were instructed to return to base.

Some of Scott’s critics, such as Roland Huntford, condemn this last minute change of plan as ill conceived, with terrible consequences for the Polar Party (Huntford, Reference Huntford2002, pp. 453–454). But Huntford was wrong. Scott and Bowers had assessed the provisions at hand on 3 January 1912, finding sufficient ration units and fuel to sustain five men on full rations for a month. Scott intended to reach the Pole and then return to Three Degree Depot on full rations within that month. Scott wrote on 3 January 1912 “We have 5½ [four-man] units of food – practically over a month’s allowance for five people – it ought to see us through” (p. 365). Bowers recorded on 4 January 1912, “Packed up sledge with 4 weeks and 5 days food for 5 men, 5 sleeping bags etc.” (Bowers, Reference Bowers1912, 4 January 1912)

Scott already knew from the Winter Journey that their Shell kerosene was good for temperatures as low as minus 70 degrees Fahrenheit. The Polar Party’s latest five days travelling, at altitudes exceeding 9,000 feet, had suggested that the Shell kerosene seemed fine for the weeks of high-altitude travel ahead. What Scott probably did not know was that in the oxygen-reduced air of the Polar Plateau, his Primus cookers would be producing more carbon monoxide than at Barrier level. In the cramped and poorly ventilated tent, the men were at risk of carbon monoxide poisoning, a cumulative hazard. It is beyond the scope of this article to investigate whether carbon monoxide poisoning on the Polar Plateau was a significant contributor to the problems experienced as they descended the Glacier.

History shows Scott and Bowers did indeed assess the situation correctly. The five-man Polar Party reached the Pole and return to Three Degree Depot on full rations within a month (actually 28 days) with surplus provisions. Adding a fifth man brought a 25% increase in the fuel ration for the Polar Party. More fuel was burnt in the tent each day (as compared with a four-man allowance), keeping the tent warmer for longer, thereby helping to dry wet footwear and clothing hanging in the peak of the tent.

The next depot, One and a Half Degree, (at 88° 29’ south) was established on 10 January 1912. Scott wrote, “Built cairn and left one week’s food together with sundry articles of clothing” (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 371) again without mentioning fuel. However, Bowers wrote on their return journey “Here we picked up 1¼ cans of oil and one week’s food for five men, together with some personal gear depoted.” (Bowers, Reference Bowers1912, 25 January 1912).

The Pole attained

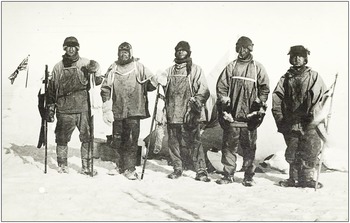

The Polar Party reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912 (Fig. 4) without any recorded reduction in food or fuel allowances. Scott’s lecture of 5 May 1911 had included calculations and details of his intended timeline (Scott, Reference Scott1911a, p. 4):

At Shackleton’s averages it would take 84 days to reach the Pole

We [therefore] have 84 days outward to Pole

[Plus] 53 days homeward from Pole to [Bluff Camp] Depot = 137 [days]

[Plus] 7 [from Bluff Camp] Depot to Hut Point = 144 [days]

3rd Nov [1911] to 27th March [1912] (Scott, Reference Scott1911a, p. 11) [The calculation of return date is straightforward: 3 November 1911 (intended start date) + 84 days (southward travel) + 1 day (at the Pole) + 60 days (northward travel) = 27 March 1912.]

Figure 4. Polar Party at the South Pole. Image scanned from (Scott, Reference Scott1911d).

Scott had told his men that if they could match Shackleton’s pace, then the Pole would be reached on Day 85 (Scott, Reference Scott1911a, p. 4) but they actually reached it on Day 78. Moreover, they had departed southwards on 1 November 1911, rather than the planned 3 November 1911 departure, gaining two more days. Benefiting from having the fifth man, they were now nine days ahead of schedule.

Scott wrote despairingly upon reaching the South Pole:

Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority. Well, it is something to have got here, and the wind may be our friend to-morrow. […] Now for the run home and a desperate struggle to get the news through first. I wonder if we can do it. (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, pp. 376–377, 470)

Scott’s phrase “to get the news through first” was redacted from the official book for unknown reasons. The phrase does appear reasonable, as they had already regained their six days behind schedule and are were now nine days ahead. With five men in harness, they would most likely make further gains. The schedule allowed 60 days for four men hauling the sledge from the Pole back to Cape Evans. Sixty days after 18 January 1912 would be 18 March 1912, but with five men in harness, they could possibly arrive several days earlier than that, possibly in time to catch the ship.

When the Polar Party reached the Pole, they had been in harness for 39 days (from the foot of the Glacier), with an estimated 60 days still to haul in harness. The work so far had been very strenuous. “About 74 miles from the Pole – can we keep this up for seven days? It takes it out of us like anything. None of us ever had such hard work before” (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 371). A few days later Scott wrote, “It is everything to keep up a good marching pace; I trust we shall be able to do so and catch the ship.” (p. 382)

The repercussions of long hours of physically demanding sledge work on a diet deficient in energy and essential vitamins, as noted in Food rations (above), were only just appearing. Those consequences would become painfully apparent in due course, along with the physical breakdown of two men and a swing from exceptionally high temperatures to exceptionally low temperatures.

Return across the Polar Plateau

The Polar Party reached 1½ Degree Depot on 25 January 1912 where Bowers recorded:

Assisted by the wind we made an excellent rundown to our One and a Half Degree Depot, where the big red flag was blowing out like fury with the breeze, in clouds of driving drift. Here we picked up 1¼ cans of oil and one week’s food for five men (Bowers, Reference Bowers1912, 25 January 1912).

The depot was in order, with the correct quantity of food and fuel for five men for a week. However, the men were not coping well, “I think about the most tiring march we have had; solid pulling the whole way, in spite of the light sledge and some little helping wind at first” (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, pp. 382–383). Others wrote about feeling the cold more acutely than before, presumably indicating depleted levels of body fat. They had taken seven days to reach 1½ Degree Depot instead of the intended six days. Scott’s hope that five men in harness would continue to make gains against schedule had not eventuated, but they were still eight days ahead of schedule.

They reached the next depot, Three Degree, on 31 January 1912, having brought about three days’ worth of surplus food which, together with depot provisions of one week’s food (Wilson, Reference Wilson1972, p. 238), allowed Scott to increase daily rations by about one seventh above normal (p. 239). This increase in food was much needed and contributed to an increase in average speed to the next depot. Regrettably, Bowers ceased regular journal entries on 25 January 1912, so from then onwards we have less precise information about fuel quantities.

The Polar Party reached the next depot, Upper Glacier, on 7 February 1912, seven days ahead of schedule. At breakfast that day (before reaching the depot), a shortfall of one full day’s biscuit allowance had been discovered – presumably a shortfall in the ration unit uplifted from Three Degree Depot a week earlier. There is no suggestion of any corresponding shortfall in fuel. At the depot Wilson noted, “We reached the Upper Glacier Depot by 7.30 p.m. and found everything right which was satisfactory” (Wilson, Reference Wilson1972, p. 240). From this depot, they took their half a week’s worth of provisions. In hindsight, that allowance was inadequate presumably based upon expectation of easy going (downhill) to the next depot about 46 miles away.

This was the end of the Polar Plateau stage and Scott wrote, “Well, we have come through our 7 weeks’ ice cap journey and most of us are fit, but I think another week might have had a very bad effect on P.O. Evans, who is going steadily downhill” (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 391). Scott may have recalculated their expected return date as follows: 92 miles (down the Glacier) at 16.2 mile per day plus 357 miles (across the Barrier) at 10 miles per day = 42 total days of travel, giving an arrival date at Cape Evans of 19 March 1912. They were still seven days ahead of Scott’s schedule but unlikely to catch the ship.

Return down the Glacier

The Polar Party reached the next depot, Middle Glacier, on 13 February 1912, taking six days. They reached the next depot, Lower Glacier, on 18 February 1912 and reached Shambles Camp later that day. This was the end of the Glacier stage.

Despite above-average temperatures as they descended the Glacier (Fogt et al., Reference Fogt, Jones, Solomon, Jones and Goergens2017, p. 2196) and despite the Glacier stage having the shortest inter-depot distances of the entire return route, this leg of the return journey was a tipping point. Scott had not left route markers on the way up the Glacier and had not made adequate navigation notes to guide their return down the Glacier. “We ought to have kept the bearings of our outwards compass that is where we failed” (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 470). The result was that the Polar Party lost their way in deep ice disturbances several times, taking 11 days to travel the 92 miles Scott had planned to achieve comfortably in six days. With only seven days’ worth of food and fuel available, rations had to be considerably reduced.

The cold, exhausted, dehydrated and undernourished men spent about a week on reduced rations for the first time on the return journey. This was bad for morale and bad for fitness. In contrast, both Atkinson’s Party and Evans’ Party completed the 92-mile Glacier leg within seven days, remaining on full rations. Scott and his men were no longer the elite party – they had become the slowest. They were now only two days ahead of schedule, which was not in itself disastrous, but they now had no chance of getting news to the ship before it departed.

Taff Evans had died on 17 February 1912, leaving only four men to do the heavy work. Oates had become susceptible to frost bite. All men were extremely tired – almost exhausted – and were now permanently hungry after their period of reduced rations on the Glacier. They desperately needed additional provisions. There would be pony meat available from the foot of the Glacier northwards, but no additional fuel had been brought for cooking it.

Arriving back at Shamble Camp on 18 February 1912, they picked up pony meat to supplement their standard food rations. Scott wrote, “Here with plenty of horsemeat we have had a fine supper, to be followed by others such, and so continue a more plentiful era if we can keep good marches up.” (p. 399). However, unplanned usage of fuel for cooking pony flesh would make inroads into their already scanty fuel allowance. Wright later noted:

The apparent neglect in Scott’s plan to make maximum use of the meat of the ponies, the survivors of which were to be shot at the foot of the Beardmore Glacier. … The use of this meat should be part of the plan even though it would mean giving up something else to make room for the extra fuel needed to cook the meat (Wilson, Reference Wilson1972, p. xiii).

Scott’s final journey on the Barrier

As they travelled northwards across the Barrier, the Polar Party could now enjoy pony meat, at least until reaching Mid-Barrier Depot, where the first pony had been killed. Four caches of pony meat were marked by cairns along their northward route. Scott and Wilson recorded multiple instances where they enjoyed “pony hoosh” (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, pp. 399–404; Wilson, Reference Wilson1972, p. 245). The desperately hungry men regularly consumed pony flesh – a necessity for which no fuel had been provided, requiring steady inroads into their already scanty fuel allowance of only two-thirds of a gallon at the next three depots.

The Polar Party reached the Southern Barrier Depot (at 82° 47’ south) on 24 February 1912, one day ahead of schedule. Scott wrote “Found stores in order except shortage oil – shall have to be very [Scott’s emphasis] saving with fuel – otherwise have 10 full days’ provision [food] from to-night and shall have less than 70 miles to go” (p. 401). Scott’s concerns about fuel never left him after the Southern Barrier Depot. Five days later Scott wrote:

Next camp [Middle Barrier Depot] is our depot and it is exactly 13 miles. It ought not to take more than 1½ days; we pray for another fine one. The oil will just about spin out in that event and we arrive [with] 3 clear days’ food in hand (p. 404).

Food rations, once supplemented by ample quantities of pony flesh, were working out as planned but fuel was desperately short. Minimum night temperatures had dropped to around minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit, requiring more fuel to melt water and cook food.

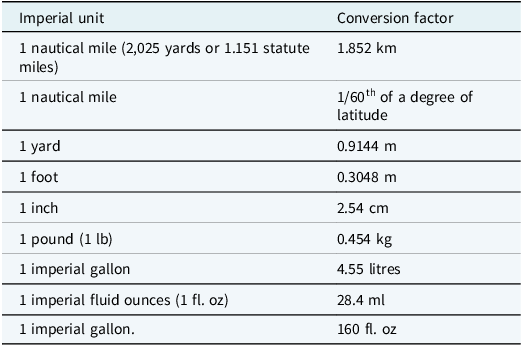

The Polar Party reached Middle Barrier Depot (at 81° 35’ south) on 2 March 1912, still one day ahead of schedule. Scott’s sledging diary for that day has been scanned (Fig. 5). He wrote about “three distinct blows” that placed his party in a bad situation, “First we found a bare ½ gallon of oil instead of the full; with most rigid economy it can scarce carry us to the next depot on this surface.” As described above, only two gallons had been left at Middle Barrier Depot, to be shared between three parties. Scott had no reason to expect a full gallon of fuel for his own party. Had he forgotten his own last-minute instructions, slipping back to the previous fuel-allowance pattern? The phrase “bare ½ gallon of oil instead of the full” was redacted from the expedition’s official book (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 404). Two days later Scott noted:

We are about 42 miles from the next depot and have a week’s food, but only about 3 to 4 days’ fuel […]. We can expect little from man now except the possibility of extra food at the next depot. A poor one. It will be real bad if we get there and find the same shortage of oil. Shall we get there? (pp. 405–406, 471)

Figure 5. Scott’s diary entry at Middle Barrier Depot, highlighting redacted text. Image scanned from (Scott, Reference Scott1911c, 2 March 1912).

A new theme entered the narrative at this point with the reference to “extra food.” It seems Scott was now hoping other returning parties would have generously left some of their own food and fuel behind for the Polar Party. Progress was slowing, due to exhaustion, inadequate nutrition and extremely low temperatures. Slower progress meant each part-can of fuel from a depot had to last longer, thereby further reducing the daily allowance. On 5 March 1912, Scott wrote, “We started [today’s] march on tea and pemmican as last night – we pretend to prefer the pemmican this way. […] Our fuel dreadfully low and poor Soldier nearly done” (p. 406). They now had insufficient fuel to melt and heat their pemmican so were consuming it solid (very cold).). Scott had by now accepted that he was unlikely to survive:

We mean to see the game through with a proper spirit, but its tough work to be pulling harder than we ever pulled in our lives for long hours, and to feel that the progress is so slow. One can only say “God help us!” and plod on our weary way, cold and very miserable, though outwardly cheerful (p. 405).

His journal entry of 7 March 1912 suggests disorientation about whether one or two depots lay between their position and One Ton (See Fig. 1):

We are 16 [miles] from our depot [Mount Hooper]. If we only find the correct proportion of food there and this surface continues, we may get to the next depot but not to One Ton Camp. (p. 407).

Scott’s expectations about the dogs had changed. He now hoped they would bring food and fuel southwards, quite different to his expectation at the Pole (seven weeks earlier) when the dogs were to hasten his newspaper report back to the ship. The slow-moving Polar Party reached Mount Hooper Depot (at 80° 32’ south) on 9 March 1912, one day behind schedule. The next day Scott wrote:

Yesterday we marched up the depot, Mt. Hooper. Cold comfort – Shortage on our allowance all round. I don’t know that anyone is to blame but generosity and thoughtfulness has not been abundant. The dogs which would have been our salvation have evidently failed. Meares had a bad trip home I suppose. It is a miserable jumble. (p. 408, 471)

Once again, Scott had been hoping that other parties would leave some of their own food and fuel behind for the Polar Party. His sentence “It is a miserable jumble” may reflect accumulated frustrations. Evans’ Party had left much of their own pemmican allowance for the Polar Party but had left no fuel to cook it (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard2010, pp. 411–412). Atkinson’s Party had been so eager to take their full entitlement of fuel that they “had to dump a lot of methylated spirits and put the rest in chafing gear tubes [containers with long spout or tube for priming a cooker with methylated spirits]” to uplift every drop of their fuel entitlement (Wright, Reference Wright, Bull and Wright1993, p. 233). It is no wonder Scott wrote “generosity and thoughtfulness has not been abundant.”

The Polar Party made their final camp at 79° 47’ south on 19 March 1912. They never left their tent again and by 29 March 1912, or shortly afterwards, Scott, Wilson and Bowers were all dead.

Development of the prevalent explanation

Scott’s final words about fuel shortages

Scott’s journals have been quoted extensively in previous sections of this article. This section, therefore, considers only what Scott wrote (and did not write) about fuel shortages in the period between leaving the Mount Hooper Depot on 10 March 1912 (the last “shortage”) and his death around 29 March 1912. During the period from 16 March 1912 to 24 March 1912, Scott wrote personal farewell letters to people who had been important in his life. None of the farewell letters mentions fuel shortages.

Scott started writing his Message to Public after the leaving Mount Hooper Depot. The full text has been copied into Appendix II. David Crane characterises the message as Scott’s “last defiant apologia, a final settling of accounts with his country and posterity” (Crane, Reference Crane2007, p. 514). Susan Solomon wrote, “Like some of his other writings, it seems to reflect a defensive turn of mind, as if he were already dreading the way that history would record his actions. And perhaps that tone contributed to the way the record indeed evolved.” (Solomon, Reference Solomon2001, p. 244). Diana Preston wrote, “Scott’s ‘Message to the Public’, written under enormous stress with his two friends dying at his side, was a careful vindication of his conduct of the expedition” (Preston, Reference Preston1997, p. 291). David Thomson wrote, “The message is frank, but not understanding; it is the more moving in that Scott died with only a sketchy notion of his mistakes” (Thomson, Reference Thomson1977, p. 293).

Scott’s message omits certain facts that could have created a more balanced explanation of fuel shortages. Understandably, Message to Public does not:

-

○ Acknowledge that dehydration and starvation were major contributors to the Polar Party’s ever-decreasing fitness in that final month.

-

○ Acknowledge that decreased fitness contributed to a reduction in daily mileage, meaning that food and fuel in depots had to sustain the men for more days than initially planned, writing instead “Every detail of our food supplies, […] worked out to perfection.”

-

○ Suggest that fuel rations “worked out to perfection.”

-

○ Address his decision to reduce the fuel allowance from a full gallon down to two-thirds of a gallon per party in several barrier depots.

-

○ Mention unplanned usage of fuel to cook pony flesh.

-

○ Explain that fuel shortages were due to a need for fuel in excess of the quantity provided in the last three depots, as instructed by himself.

Instead of providing a balanced record, Scott’s message deflected blame by stating “a shortage of fuel in our depots for which I cannot account.”

Evans’ stance on fuel shortages

As second-in-command, Evans became Expedition Leader after Scott’s death, the public face and spokesperson for the expedition. Evans avoided in-depth discussions about fuel shortages, stating that food and fuel simply ran out in the final prolonged blizzard (implying all was well until the final blizzard). He never explained his stance.

After the Terra Nova left the Antarctic for the last time, Evans had to draft the press telegram Scott had sold in advance to Central News (London). It was to be a South Polar Story of 8,000 to 10,000 words. Evans convened an on-board working group of officers to draft the telegram. Apparently, Evans wanted to delete the reference to fuel shortages from Scott’s Message to Public:

I have had a talk with Atkinson: Evans has been trying get Drake to read Scott’s Diary – he wants to have the passage about the lack of oil out of Scott’s Message to the Public – he wants to put excuses of loss back into the telegram (Cherry-Garrard, Reference Cherry-Garrard1913a, 21 January 1913)

Evans’ 2,500-word press telegram, which included the full text of Message to Public, provides no hint of the fuel crisis the Polar Party experienced at their last three depots:

On March 16th Oates was really unable to travel, but the others could not leave him. After his gallant death, Scott, Wilson and Bowers pushed northwards, when the abnormally bad weather would let them, but were forced to camp […] eleven miles south of the big depot at One Ton Camp. This they never reached, owing to a blizzard, which is known from the records to have lasted nine days, overtaking them, and food and fuel giving out. (“What the records told”, 1913)

Evans presented the expedition’s formal report to a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society (“RGS”) in July 1913. There is no mention in Evans’ 17-page report of any fuel shortage. Evans’ memoir South with Scott does not explicitly address fuel shortages at Scott’s last three depots, commenting only on kerosene leakage that was discovered by the Search Party at One Ton (Evans, Reference Evans1961, p. 251). Evans claimed the leakage caused a shortage at One Ton, yet the men of the Search Party said that there was still ample fuel left in that depot. The accuracy of Evans’ statement is dubious.

As noted in Teddy Evans’ folly (above), there is evidence suggesting Evans left behind the three gallons of kerosene that Scott had explicitly instructed him to take from the failed motors to 80½° south. If that is true, and if Evans felt guilty, then that might explain his persistent efforts to downplay or deny fuel shortages. Those three gallons would have permitted a full gallon to be left for each returning party at the last three barrier depots. One can understand Evans’ desire to stifle public discussion.

Editor Leonard Huxley’s contribution

Evans’ press telegrams, sent from Christchurch in February 1913, had contained the full text of Message to Public (see Appendix II) but had provided no elucidation on fuel shortages (see Evan’s stance on fuel shortages above). News Agencies were not impressed:

The ‘brevity, and in some cases the peculiar wording of the first dispatch [press telegram] which we received attracted immediate attention here,’ commented the general manager of the Central News Agency, John Gennings, ‘and gave rise to an almost universal belief that something had occurred which it was sought to hide.’ (Jones, Reference Jones2003, p. 110)

Newspapers reacted to the reference to fuel shortages in Scott’s message:

‘Out of his diary leaps a phrase which demands elucidation insistently’, observed the Daily Express, “We should have got through in spite of the weather… but for a shortage of fuel in our depots for which I cannot account.” The words are ominous. Will they ever be explained?’ (Jones, Reference Jones2003, p. 114)

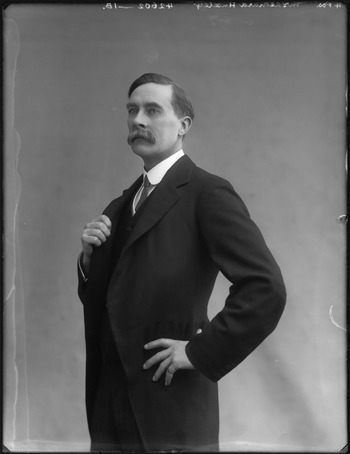

In April 1913, after the expedition’s return to Britain, expedition committee members were eager not to cause controversy, so did not draw attention to fuel shortages. They rejected a solo effort by the RGS President (Curzon) to establish an informal enquiry, because Admiral Lewis Beaumont had advised against it (Jones, Reference Jones2003, p. 117). Beaumont had warned that no one could predict where an enquiry might lead. A tidy explanation for fuel shortages was required – an official opinion on the causes of fuel shortages. Scott had engaged publishers Smith, Elder to produce the book of the expedition. Leonard Huxley was hired as Editor and he was advised by Kathleen Scott, some committee members and some expedition members (notably Atkinson and Cherry-Garrard). Scott’s Last Expedition appeared in November 1913. Huxley (Fig. 6) may have had more influence over the book’s content than was acknowledged at the time.

Figure 6. Leonard Huxley, Editor of Scott’s Last Expedition. Image courtesy National Portrait Gallery, NPG x127808.

The official opinion on fuel shortages appeared as Huxley’s Note 26 (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, pp. 441–443). It soon became widely disseminated as the official explanation. The text of Note 26 has been copied into Appendix I. Dr Max Jones (editor of the most recent version of Scott’s Journals) believes Note 26 was most likely written by Cherry-Garrard (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006, p. 501). Evidence suggests that the long-winded wide-ranging note may well be the work of more than one person, or possibly a committee, intent on leaving no loose ends. In any event, it became a definitive part of the story of Scott’s fuel shortages.

Official explanation for oil shortages: Editor’s Note 26

Huxley’s Note 26 asserts that fuel shortages arose not from greed of supporting parties (as suggested by Curzon) but from unsuitable washers on the fuel cans. It assumed that an adequate fuel ration had been left at all depots for the returning Polar Party. The note unequivocally states that fuel losses were caused by evaporation of kerosene that had escaped through cold-damaged washers. This explanation conveniently absolves expedition members from personal blame and upholds the reputations of the naval officers involved. It satisfied the expedition committee’s desire to avoid controversy over fuel shortages and remains today as the prevalent explanation.

Memoirs of expedition members are mostly silent about fuel shortages, but a few (such as Cherry-Garrard’s) rely on the official explanation and none offer alternative explanations. Official expedition reports rely on the official explanation. In light of earlier sections of this article, several doubtful assumptions and assertions can be identified in Note 26:

-

○ It incorrect assumes that Scott’s term “shortage” meant kerosene had been depleted when in fact, the men’s need for fuel had increased since depots were established.

-

○ The false assertion that kerosene is “specially volatile.”

-

○ The unverified assertion that kerosene cans were placed on top of depot cairns, where solar gain heated the cans, causing fuel to escape by evaporation.

-

○ The irrelevant (and implausible) tale of unexplained loss from eight cans that were stored for more than a year under a snowdrift at Cape Evans, purportedly proving that evaporation could have occurred in barrier depots.

-

○ The dubious reasoning that fuel leakage and food contamination at One Ton somehow proved that evaporation could have occurred at other barrier depots.

-

○ The misleading implication that fuel shortages were widespread and random – overstating the true situation tabulated in Table 2 (above).

-

○ It is silent about Scott reducing the fuel ration from one gallon per ration unit down to two-thirds of a gallon at some barrier depots.

-

○ It is silent about unplanned usage of fuel to cook pony flesh.

Several aspects of Note 26 warrant re-examination: its assumptions about the meaning of “shortage,” its characterisation of kerosene volatility, and its unverified claims about depot practice. These features raise concerns about the note’s explanatory adequacy and suggest it functioned, in part, to deflect scrutiny from operational decisions.

Conclusions: the cause of fuel shortages

The greater part of this article has presented a detailed account of what actually happened in the story of Scott’s fuel shortages, derived from a wide range of primary expedition records. It is a tragic story, one of the extreme human hardships caused by planning errors, inadequate provisions (both food and fuel), ad hoc changes to the plan, and extremely fine contingency margins, aggravated in the final month by extreme cold.

The best-known reference to fuel shortages appeared in Scott’s personal journals, in his Message to Public. His message omitted certain facts that could have created a more balanced explanation. He cited only the unexpectedly cold weather of March 1912 as a contributing factor. See Scott’s final words about fuel shortages (above).

The Expedition Committee’s official explanation of fuel shortages first appeared as Editor’s Note 26 in the expedition’s official book (Scott, Reference Scott and Jones2006). It assumes that an adequate quantity of kerosene (“fuel ration”) was initially stowed in depots that were to be used by three returning parties and that widespread random evaporation of kerosene subsequently reduced the quantity available. The loss was blamed on leather washers located between the can’s spout and its brass screw cap. The washers were said to harden, shrink and crack in extreme cold, permitting evaporation. See Official explanation: Editor’s Note 26 (above).

Conclusion 1

In a late reorganisation, Scott reduced the Polar Party’s ration at some depots from one gallon of kerosene per depot to two-thirds of a gallon per depot, in hindsight an error of judgement.

Conclusion 2

This under-provisioning was exacerbated by the Polar Party travelling more slowly than intended in the final stages, so each can of fuel had to last several days longer than intended.

Conclusion 3

The weather as they returned across the Barrier was much colder than expected, requiring more fuel than planned to melt ice for drinking water and to cook food.

Conclusion 4

The Polar Party had a substantial quantity of pony meat to eat but had not brought fuel to cook it, necessitating more unplanned usage of kerosene.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247425100144

Competing interests

Conflict of interest: The author declares none.