Introduction

Bermudagrass is a perennial warm-season grass that grows from mid-spring to mid-fall. It reproduces through rhizomes and stolons, with a few cultivars producing seeds (Wallau et al. Reference Wallau, Vendramini and Yarborough2024). The leaves are gray-green, and the seed heads form from upright spikelets. Bermudagrass is an important species in livestock grazing and hay production in Florida and other areas of the southeastern United States (Sellers et al. Reference Sellers, Smith and Ferrell2025). It is highly productive, is tolerant of drought, and withstands heavy grazing. However, weeds, especially grass weeds, tend to establish and compete with bermudagrass, reducing productivity. Grass weeds like bahiagrass, guineagrass, and vaseygrass predominate in bermudagrass pastures due to their low nutritive value and palatability, and their presence in the field contaminates fodder, reducing its quality and appearance (Putman and Orloff Reference Putman and Orloff2014; Rouquette et al. Reference Rouquette, Corriher-Olson and Smith2020). Also, the success of these weeds is influenced by their ability to grow and reproduce during the growing season of bermudagrass (Sellers et al. Reference Sellers, Smith and Ferrell2025), their tolerance to mowing (Henry et al. Reference Henry, Yelverton and Burton2007), and differences in cultivar response to herbicides (Bunnell et al. Reference Bunnell, Baker, McCarty, Hall and Colvin2003; Jeffries et al. Reference Jeffries, Travis and Yelverton2017), which result in difficult weed control.

Bahiagrass, a perennial warm-season forage crop cultivated throughout Florida, is a common weed in bermudagrass pastures. Its dense sod and vegetative propagation through rhizomes and stolons with a deep root system enable establishment. Also, it reproduces by seeds, and the tall seed heads consist of 2 to 3 smooth and shiny, spikelike racemes with multiple tiny spikelets. The seeds are ovoid shaped and glossy yellowish (Wallau et al. Reference Wallau, Vendramini, Dubeux and Blount2023). The leaves are formed at the base of the plant and are flat, folded, and tapered at the tip. However, bahiagrass control in bermudagrass pastures with selective herbicides is challenging and often inconsistent. For example, metsulfuron is reported to be ineffective against several bahiagrass cultivars, but bermudagrass is tolerant (Bunnell et al. Reference Bunnell, Baker, McCarty, Hall and Colvin2003; Matocha and Grichar Reference Matocha and Grichar2013). Conversely, Grichar et al. (Reference Grichar, Baumann, Baughman and Nerada2008) reported that imazapic completely controlled bahiagrass but significantly damaged bermudagrass. Therefore exploring combinations of these herbicides to reduce bahiagrass dominance while encouraging bermudagrass growth is important.

Vaseygrass and guineagrass, perennial grasses characterized by smaller fibrous roots, have also become common weeds in bermudagrass pastures throughout the southeastern United States (Webster Reference Webster2000). Controlling these species is challenging because they are often misidentified as johnsongrass. Vaseygrass is a bunch-type grass that grows well in wet fields and alongside drainage ditches (Sellers et al. Reference Sellers, Smith and Ferrell2025). The leaves are elongated and narrow with an indented midrib and wrinkled leaf margins. Also, the grass contains hair where the leaves join the stem, but these hairs disappear as the stem lengthens. It reproduces by seed, and the seed head has alternating spikelets forming silky hairs around the seeds. The seeds are produced throughout the seed head branch and are flat with some hairs (Sellers et al. Reference Sellers, Smith and Ferrell2025). Conversely, guineagrass colonizes disturbed sites, including roadsides, and prefers drier areas. The leaves have a prominent white midrib, and their undersides are rough with stiff hair. Additionally, the leaf blades are long, narrow, and finely tipped. The stems have scattered but abundant hairs, and the hair density varies with biotypes. The seed head of guineagrass is a single, open panicle with smaller green to purple wrinkled seeds. However, there is limited information on effective chemical management techniques for these grasses. Fewer studies (Sellers et al. Reference Sellers, Smith and Ferrell2025) have identified glyphosate as an effective herbicide to control these weeds, though spot spray applications are recommended to avoid bermudagrass injury. Other efficacious herbicides are imazapic, nicosulfuron, and metsulfuron (Jeffries et al. Reference Jeffries, Travis and Yelverton2017).

Controlling undesirable grass weeds in bermudagrass pastures depends on applying nonselective herbicides like glyphosate, which injures bermudagrass. Preliminary observations indicate that established bermudagrass is relatively tolerant to low glyphosate application rates (Abreu et al. Reference Abreu, Rocateli, Manuchehri, Arnall, Goad and Antonangelo2020). For example, Webster et al. (Reference Webster, Hanna and Mullinix2004) reported that common bermudagrass was tolerant to glyphosate rates <0.84 kg ae ha−1 applied at 15-cm height. Additionally, Abreu et al. (Reference Abreu, Rocateli, Manuchehri, Arnall, Goad and Antonangelo2020) reported that the bermudagrass cultivars ‘Greenfield’ and ‘Goodwell’ had minimal visual injury (<55%) 16 d after treatment (DAT), which was transient as regrowth resumed approximately 24 DAT. Therefore weed management can be enhanced by understanding how each herbicide, whether applied alone or in combination, improves bahiagrass, guineagrass, and vaseygrass control. Hence the objectives of the study were to evaluate (a) the efficacy of glyphosate and glyphosate tank mixes on bahiagrass control under field conditions and (2) the efficacy of glyphosate, imazapic, and nicosulfuron + metsulfuron on the control of guineagrass and vaseygrass under greenhouse conditions.

Materials and Methods

Control of Bahiagrass with Glyphosate Alone and in Tank Mixes

Field experiments were conducted at the Plant Science Research and Education Unit near Citra, FL (29.405°N, 82.169°W), in June 2016 and repeated at the Range Cattle Research and Education Center (RCREC) near Ona, FL (27.673°N, 82.569°W), in July 2018. The soil at the Citra location was Arredondo sand (loamy, siliceous, semiactive, hyperthermic Grossarenic Paleudults) with 1% organic matter and pH 5.3, while the soil at the Ona location was a Pomona fine sand (sandy, siliceous, hyperthermic Ultic Alaquods) with 1% organic matter and pH 4.8.

The experiment had eight treatments of either glyphosate (Roundup PowerMAX®, Bayer Crop Science, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 0.28 and 0.56 kg ae ha−1 applied alone or in a tank mix with metsulfuron (Escort®, Bayer Crop Science) at 0.008 kg ai ha−1, imazapic (Impose, Adama, Raleigh, NC, USA) at 0.11 kg ae ha−1, or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron (Pastora®, DuPont, Wilmington, DE, USA) at 0.06 + 0.02 kg ai ha−1, with four replications in a randomized complete block design. A nontreated check was included for comparison. A non-ionic surfactant (NIS) (ACTIVATOR 90, Loveland Products, Loveland, CO, USA) at 0.25% v/v was added to each treatment per label instructions. Each experimental site consisted of pure, ‘Pensacola’ bahiagrass with plots measuring 3.1 × 6.2 m. Fertilizer was not applied. The experimental area was mowed to an initial height of 6 to 8 cm 7 d before herbicide application to simulate a haying operation in bermudagrass hayfields. A CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer with an AM11002 low-pressure Airmix® venturi nozzle (Greenleaf Technologies, Covington, LA, USA) calibrated to deliver herbicide treatments at 187 L ha−1 at 193 kPa.

Vaseygrass and Guineagrass Response to Glyphosate and Herbicide Mixes

Three experimental runs were conducted at the RCREC greenhouse in 2017 and 2018. Individual vaseygrass and guineagrass culms with undamaged roots were separated from field-dug clumps and planted into individual 3.8-L plastic pots filled with a commercial potting soil mix (Sun Gro Professional Growing Mix, Sun Gro Horticulture, Agawam, MA, USA). Miracle-Gro fertilizer (N:P:K, 24:8:16) was applied at 35 kg N ha−1, 12 kg P ha−1, and 23 kg K ha−1 at weekly intervals. Plants were grown in a greenhouse with a day/night 30/24 C and were irrigated as needed. After establishment, the plants in each pot were clipped to a height of 6 to 8 cm, and 1 mo of regrowth was allowed prior to cutting to the same height and treatment application. During the regrowth phase, plants were fertilized biweekly.

The experimental design for each experiment was a randomized complete block design with four replications. The herbicide treatments were divided into three experiments: (1) glyphosate-only treatments with six application rates (0.14, 0.28, 0.56, 0.84, 1.12, and 2.24 kg ae ha−1), (2) imazapic-only treatments with five application rates (0.02, 0.04, 0.07, 0.14, and 0.28 kg ae ha−1), and (3) a tank-mix experiment containing glyphosate at 0.28 or 0.56 kg ae ha−1 alone or in combination with 0.07 kg ae ha−1 imazapic or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron at 0.06 + 0.02 kg ai ha−1; imazapic and the premix of nicosulfuron + metsulfuron were also applied without glyphosate. Treatments were applied with a compressed air-powered moving nozzle spray chamber (Generation II Spray Booth, Devries Manufacturing, Hollandale, MN, USA) equipped with a TeeJet® 8001 EVS spray nozzle (TeeJet Technologies Southeast, Tifton, GA, USA) calibrated to deliver 187 L ha−1 at 172 kPa. All herbicide treatments included NIS (ACTIVATOR 90) at 0.25% v/v.

Data Collection

Control of grasses was evaluated using a visual estimate of a control scale of 0 to 100, with 0 representing no control and 100 indicating complete death. Bahiagrass visual estimates of control were recorded at 30 and 60 DAT, while vaseygrass and guineagrass visible estimates of control were recorded at 15 and 30 DAT. A 1.5 × 1.8 m swath was harvested from each bahiagrass plot for biomass determination at 30 and 60 DAT. In the greenhouse experiment, biomass was determined by clipping the treated plants at 30 DAT and reclipping at 60 DAT. Samples were dried at 60 C in a forced-air oven for 72 h, and dry weight was recorded. Biomass was expressed as percent of nontreated in the bahiagrass field study and the greenhouse studies.

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed using the open-source statistical software R (version 4.3.1; R Core Team Reference Core Team2022). Bahiagrass data for control and biomass were subjected to analysis of variance to test for glyphosate and glyphosate tank-mix effect per study area. Visual estimates of control and biomass for guineagrass and vaseygrass were determined by mixed-effects models using the package nlme in R (Pinheiro Reference Pinheiro2025). Glyphosate, imazapic, tank-mix rates, and their interactions were the fixed effects; the experimental run was a random effect. The effective imazapic rate for visual estimates of control and biomass reduction by 80% (ED80) for guineagrass and vaseygrass was obtained from a three-parameter log-logistic model (Equation 1), whereas for glyphosate, it was obtained from a four-parameter log-logistic model (Equation 2) using the ED function under the drc (Ritz and Streibig Reference Ritz and Streibig2016) package in R:

where Y is biomass or visual estimates of control of guineagrass or vaseygrass, x is glyphosate or imazapic application rate (kg ae ha−1), b is the relative slope at the inflection point, d is the upper limit of the curve, c is the lower limit of the curve, and e is the fitted line’s inflection point (ED80). Simple linear regression, two-, three-, and four-parameter log-logistic models were first run, and the best model was chosen using Akaike’s information criterion in the qpcR package of R (Ritz and Spiess Reference Ritz and Spiess2008). A lack-of-fit test at the 95% confidence level (P ≤ 0.05) was conducted to assess the model fit of the linear regressions (Ritz and Streibig Reference Ritz and Streibig2005). Standard error, t-test, and F-test were used to assess the differences in parameter estimations at the 5% significance level.

Results and Discussion

Control of Bahiagrass with Glyphosate Alone and in Mixtures

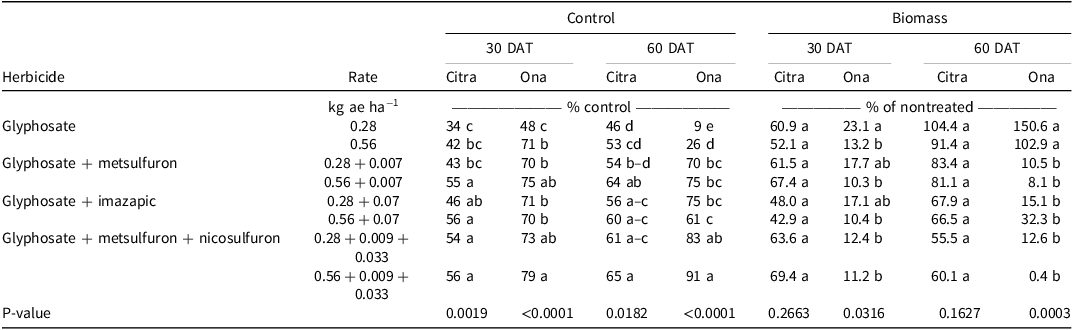

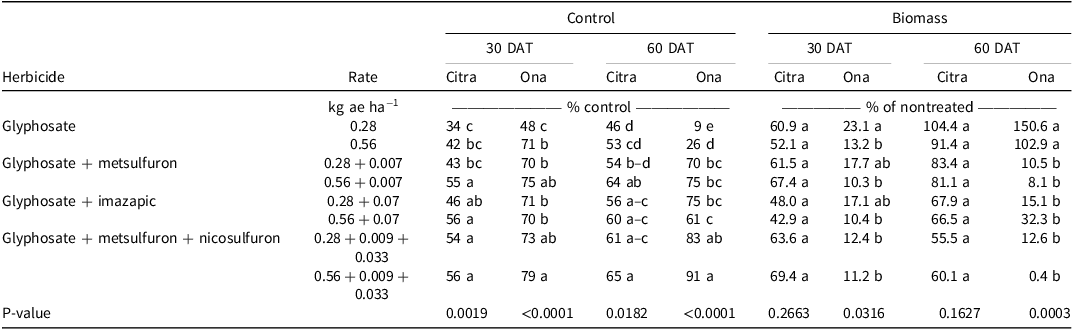

Visual estimates of bahiagrass control in Citra, FL, were different among treatments. Glyphosate at 0.28 kg ae ha−1 resulted in 34% and 46% control at 30 and 60 DAT, respectively (Table 1), and increasing the glyphosate rate to 0.56 kg ae ha−1 did not increase control at either evaluation. However, the addition of imazapic or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron to glyphosate at 0.28 kg ae ha−1 resulted in at least 1.6 times greater control than glyphosate alone 30 DAT; this trend was also observed 60 DAT, with the same mixtures providing at least 1.2 times greater control. Adding either metsulfuron, imazapic, or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron resulted in at least 1.3 times greater control than glyphosate alone at 0.56 kg ae ha−1 30 DAT. However, only glyphosate mixtures containing metsulfuron or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron resulted in greater control than glyphosate alone at 0.56 kg ae ha−1 60 DAT. At Ona, FL, glyphosate at 0.28 kg ae ha−1 resulted in the least bahiagrass control 30 (48%) and 60 (9%) DAT. Increasing the glyphosate rate to 0.56 kg ae ha−1 resulted in 1.5 and 3 times greater bahiagrass control 30 and 60 DAT, respectively; however, bahiagrass control following the high rate of glyphosate 60 DAT was <30% (Table 1). Only the addition of nicosulfuron + metsulfuron resulted in increased bahiagrass control compared to the high rate of glyphosate alone 30 DAT. Conversely, bahiagrass control 60 DAT with glyphosate + imazapic or metsulfuron or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron was at least 7.8 and 2.3 times greater than glyphosate alone at 0.28 and 0.56 kg ae ha−1, respectively. These data indicate that a tank-mix partner is necessary with glyphosate to control bahiagrass, as bahiagrass control was transient when using glyphosate alone.

Table 1. Effect of glyphosate and glyphosate tank mixes on bahiagrass control and biomass at Citra and Ona, FL, in 2016 and 2018, respectively.a,b,c

a Means followed by the same letter within columns are not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05.

b Abbreviation: DAT, days after treatment.

c Biomass of nontreated bahiagrass at the Citra location was 531 and 667 kg ha−1 at 30 and 60 DAT, respectively. Nontreated bahiagrass biomass at the Ona location was 444 and 275 kg ha−1 at 30 and 60 DAT, respectively.

Although herbicide treatments resulted in differences in bahiagrass control at Citra, there were no differences in bahiagrass biomass among the treatments 30 or 60 DAT (Table 1). Biomass 30 DAT ranged from 43% to 69% of the nontreated control and from 56% to 104% of the nontreated control 60 DAT. Conversely, there were differences in biomass among treatments 30 and 60 DAT at Ona. Bahiagrass biomass ranged from 10% to 18% of the nontreated control 30 DAT. Biomass was 1.9 times greater with glyphosate at 0.28 kg ae ha−1 than this rate of glyphosate applied with nicosulfuron + metsulfuron. Additionally, bahiagrass biomass was 1.8 times greater when glyphosate was applied at a low rate versus at a high rate. Bahiagrass fully recovered by 60 DAT when glyphosate was applied at either rate, as biomass was at least 103% of the nontreated control. Adding metsulfuron, imazapic, or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron to glyphosate at either rate 60 DAT reduced biomass production, with bahiagrass biomass ranging from 0.4% to 32% of the nontreated control.

Bahiagrass recovery following glyphosate applied alone was expected, as recommendations to kill bahiagrass for pasture renovation are usually 3.36 kg ae ha−1 (Bunnell et al. Reference Bunnell, Baker, McCarty, Hall and Colvin2003; Rogers et al. Reference Rogers, Miller and King1987). The variability in responses at the Citra location could be due to contamination of diploid ‘Pensacola’ bahiagrass with tetraploid ‘Argentine’ bahiagrass, as tetraploid cultivars are tolerant to acetolactate synthase–inhibiting herbicides (Bunnell et al. Reference Bunnell, Baker, McCarty, Hall and Colvin2003). The differences between the two locations with regard to bahiagrass response could be due to differences in soil pH, as the Citra location soil pH was near the optimum of 5.5 (Wallau et al. Reference Wallau, Vendramini, Dubeux and Blount2023), which likely made the bahiagrass more resilient to herbicide applications. The tank mixes of glyphosate and/or imazapic and nicosulfuron + metsulfuron at Ona showed increased bahiagrass control and biomass reduction, and this was likely due to the combined effect of the herbicides. Metsulfuron controls broadleaf and grass weeds and is effective against bahiagrass (McElroy and Martin Reference McElroy and Martin2013). Therefore glyphosate + nicosulfuron + metsulfuron mixtures demonstrate potential for use in bermudagrass pastures, as glyphosate applied at these rates and nicosulfuron + metsulfuron cause minimal damage to bermudagrass while removing bahiagrass (Abreu et al. Reference Abreu, Rocateli, Manuchehri, Arnall, Goad and Antonangelo2020; Matocha et al. Reference Matocha, Grichar and Grymes2010). The herbicide label recommends the application of nicosulfuron + metsulfuron earlier in the growing season (March to April) than the application in this study (June to July). However, a delayed application schedule was chosen because the rainy season in Florida begins from mid- to late June, hence increasing the efficacy of the herbicide at this application timing.

Vaseygrass and Guineagrass Response to Glyphosate and Herbicide Mixes

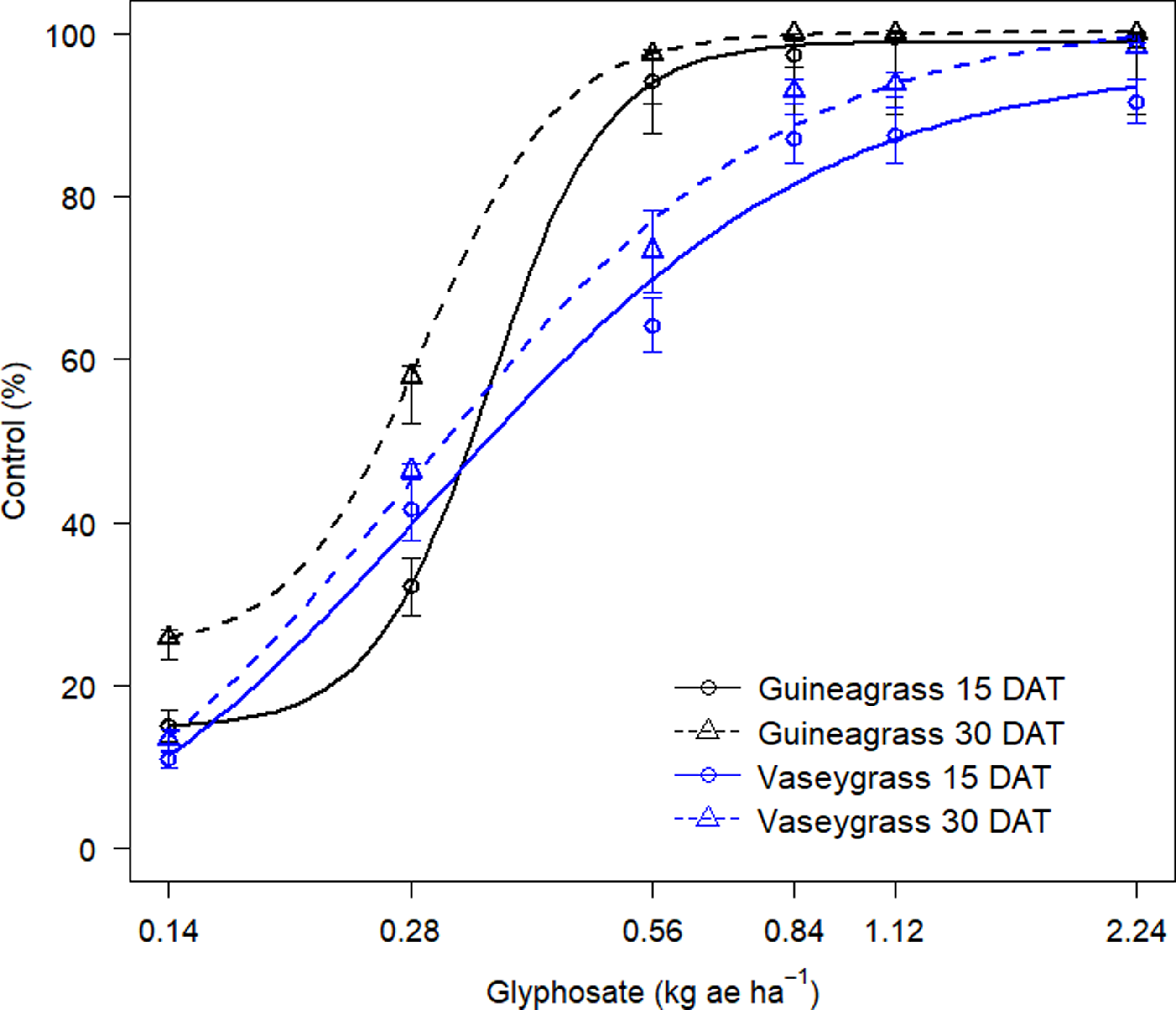

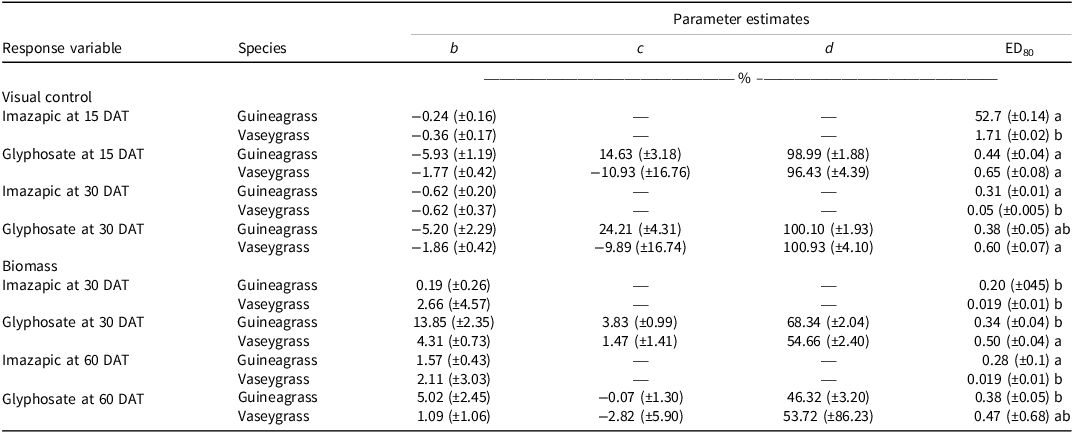

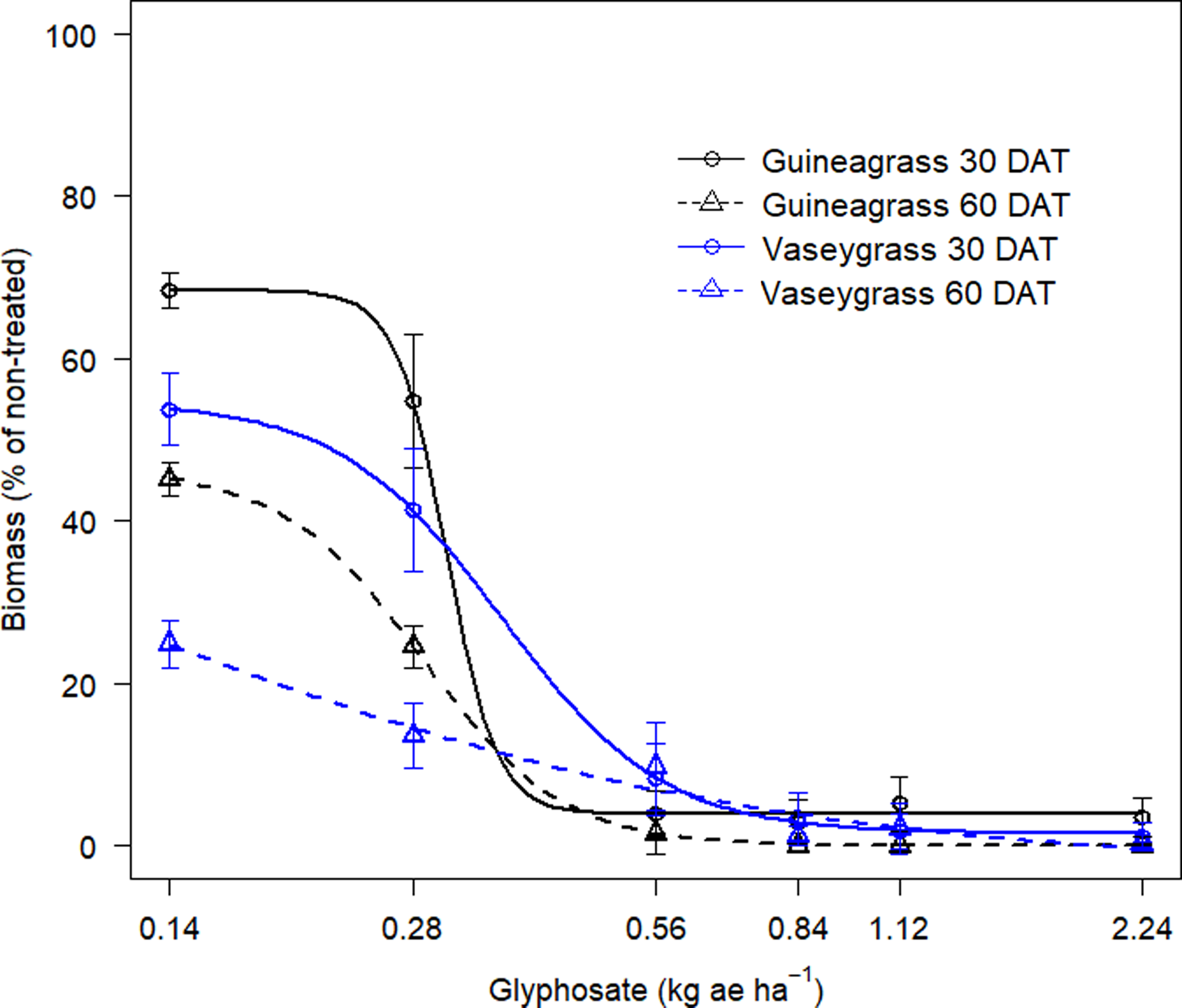

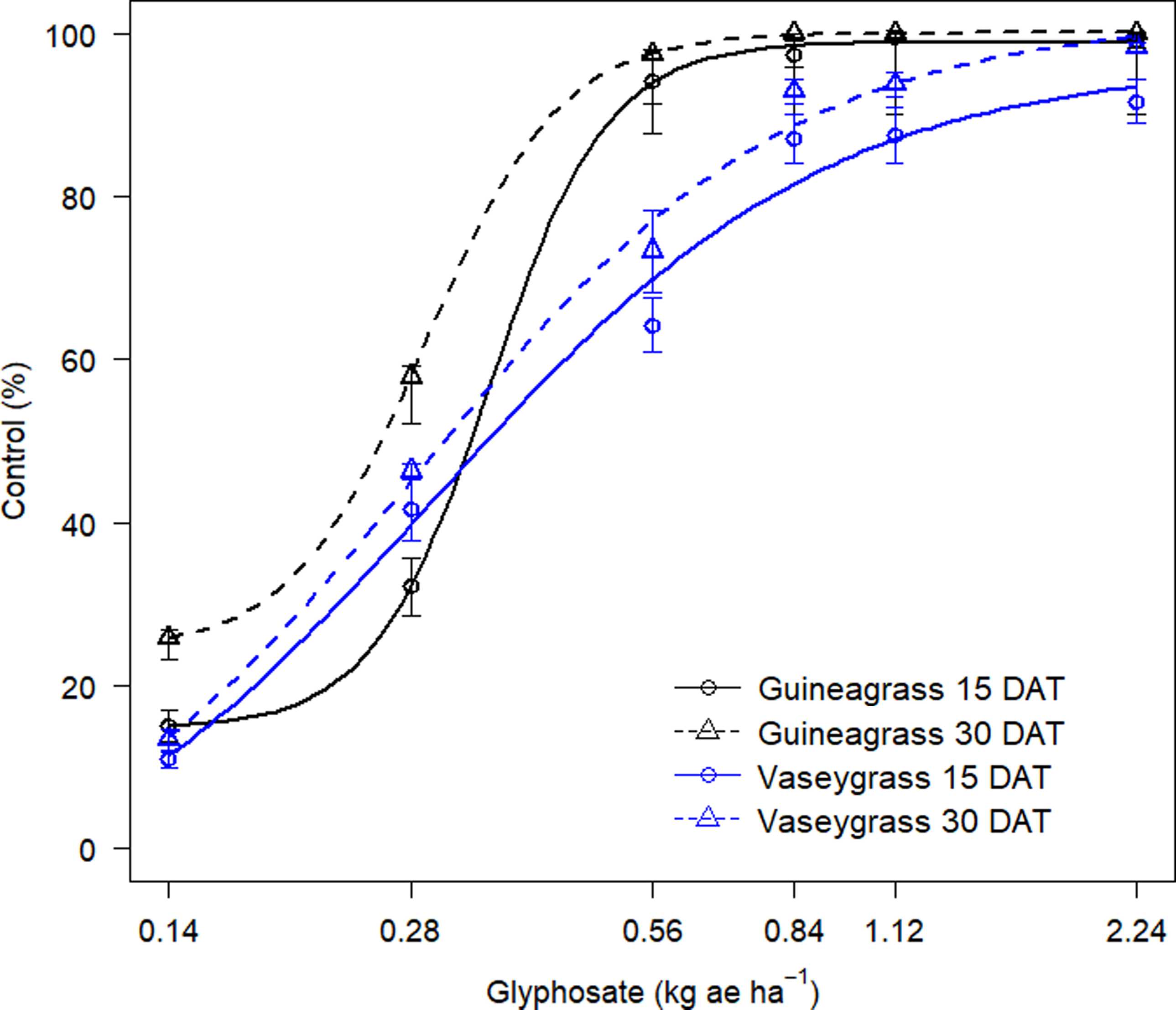

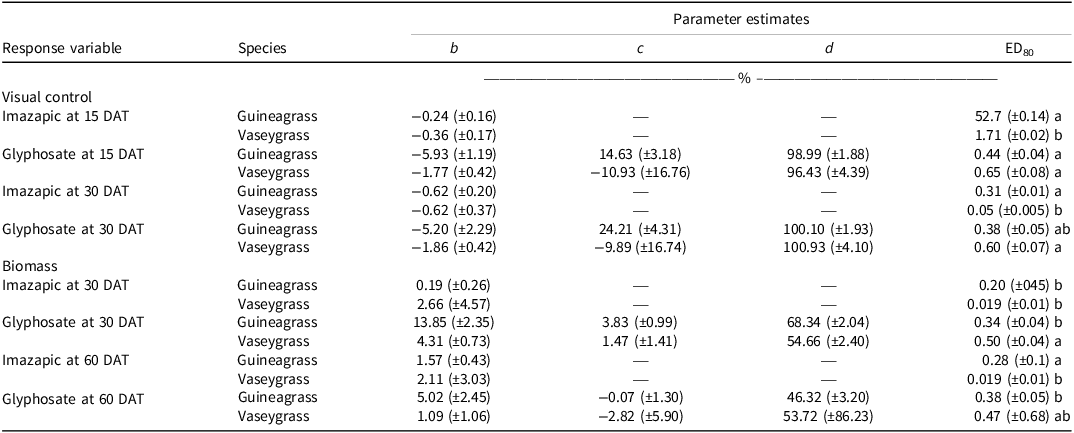

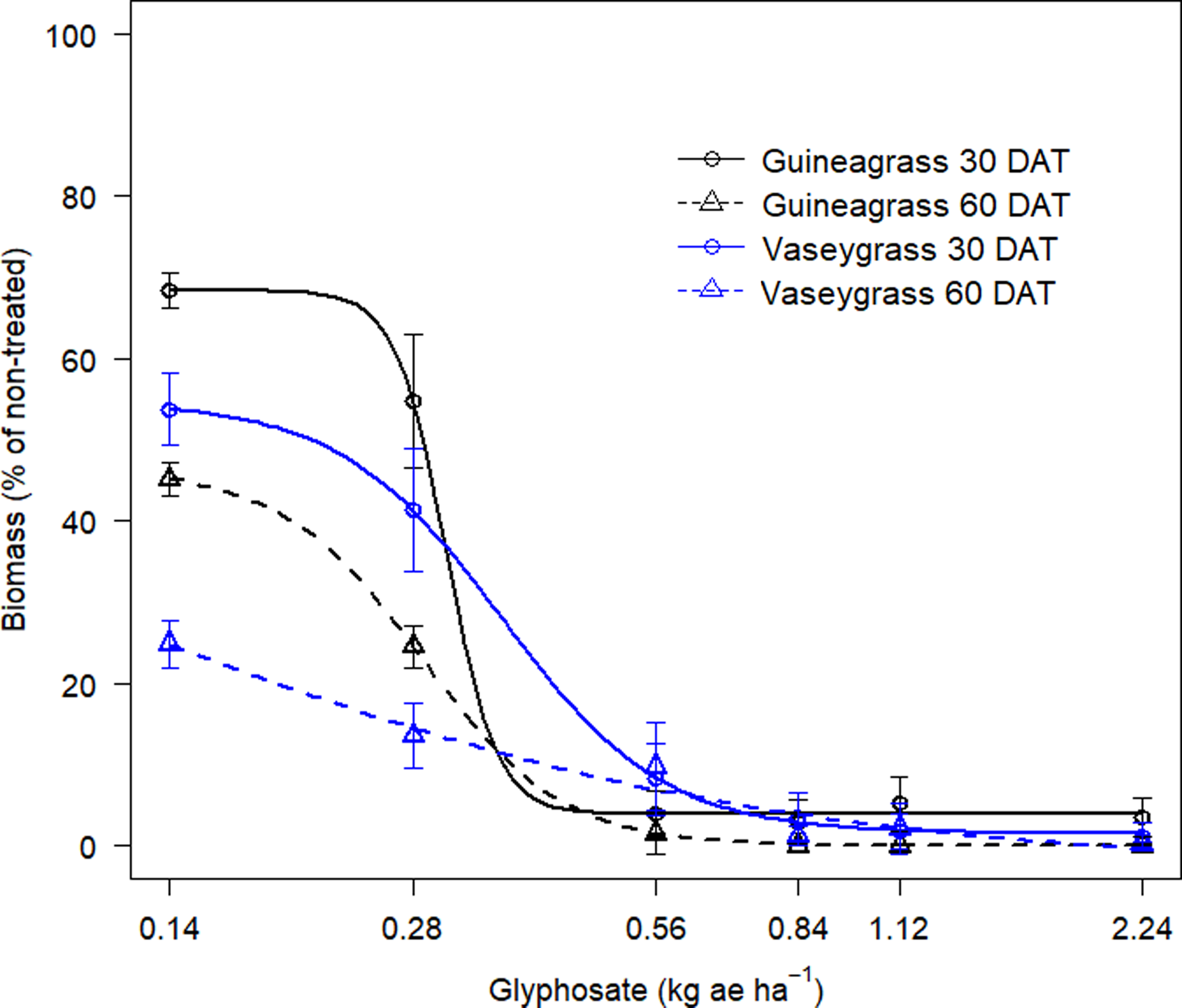

There was no Glyphosate × Experimental Run effect for visual estimates of control and biomass for either grass species. Increasing glyphosate rates significantly influenced visual estimates of control for both guineagrass and vaseygrass (Figure 1). The greatest control of guineagrass 15 and 30 DAT was observed with glyphosate rates >0.56 kg ae ha−1, whereas control of vaseygrass was observed with glyphosate rates >0.84 kg ae ha−1. Additionally, the effective glyphosate rate needed to achieve ED80 guineagrass control was 0.44 and 0.38 kg ae ha−1, while for vaseygrass the effective glyphosate rate was 0.65 and 0.60 kg ae ha−1 15 and 30 DAT, respectively. Biomass ED80 value estimates showed that glyphosate rates of 0.34 and 0.47 kg ae ha−1 were required for ED80 guineagrass biomass reduction, while glyphosate rates of 0.38 and 0.50 kg ae ha−1 were required for vaseygrass 30 and 60 DAT, respectively (Table 2; Figure 2). The findings corroborate work by Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Gonçalves, Scarano, Pereira and Martins2017), who reported effective guineagrass control with glyphosate at 0.54 kg ae ha−1.

Figure 1. Visual estimates of control (%) of guineagrass and vaseygrass at 15 and 30 d after treatment (DAT) in response to glyphosate rates under greenhouse conditions in 2017 and 2018. Solid and dashed lines represent predicted values. Data were fit to a four-parameter log-logistic regression model, Y = c + {d – c/1 + exp[b(log (x) – log(e)]}, where Y is visual estimates of guineagrass or vaseygrass control, x is glyphosate application rate (kg ae ha−1), b is the relative slope at the inflection point, d is the upper limit of the curve, c is the lower limit of the curve, and e is the fitted line’s inflection point (ED80).

Table 2. Log-logistic regression parameter estimates for visual control at 15 and 30 d after treatment (DAT) and biomass at 30 and 60 DAT of guineagrass and vaseygrass experiments under greenhouse conditions in Ona, FL, in 2017 and 2018.a,b,c

a Standard errors are in parentheses.

b Means followed by the same letter within columns are not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05.

c Abbreviation: DAT, days after treatment.

Figure 2. Biomass reduction (%) at 30 and 60 DAT of guineagrass and vaseygrass in response to glyphosate rates under greenhouse conditions in 2017 and 2018. Solid and dashed lines represent predicted values. Data were fit to a four-parameter log-logistic regression model, as given in Figure 1.

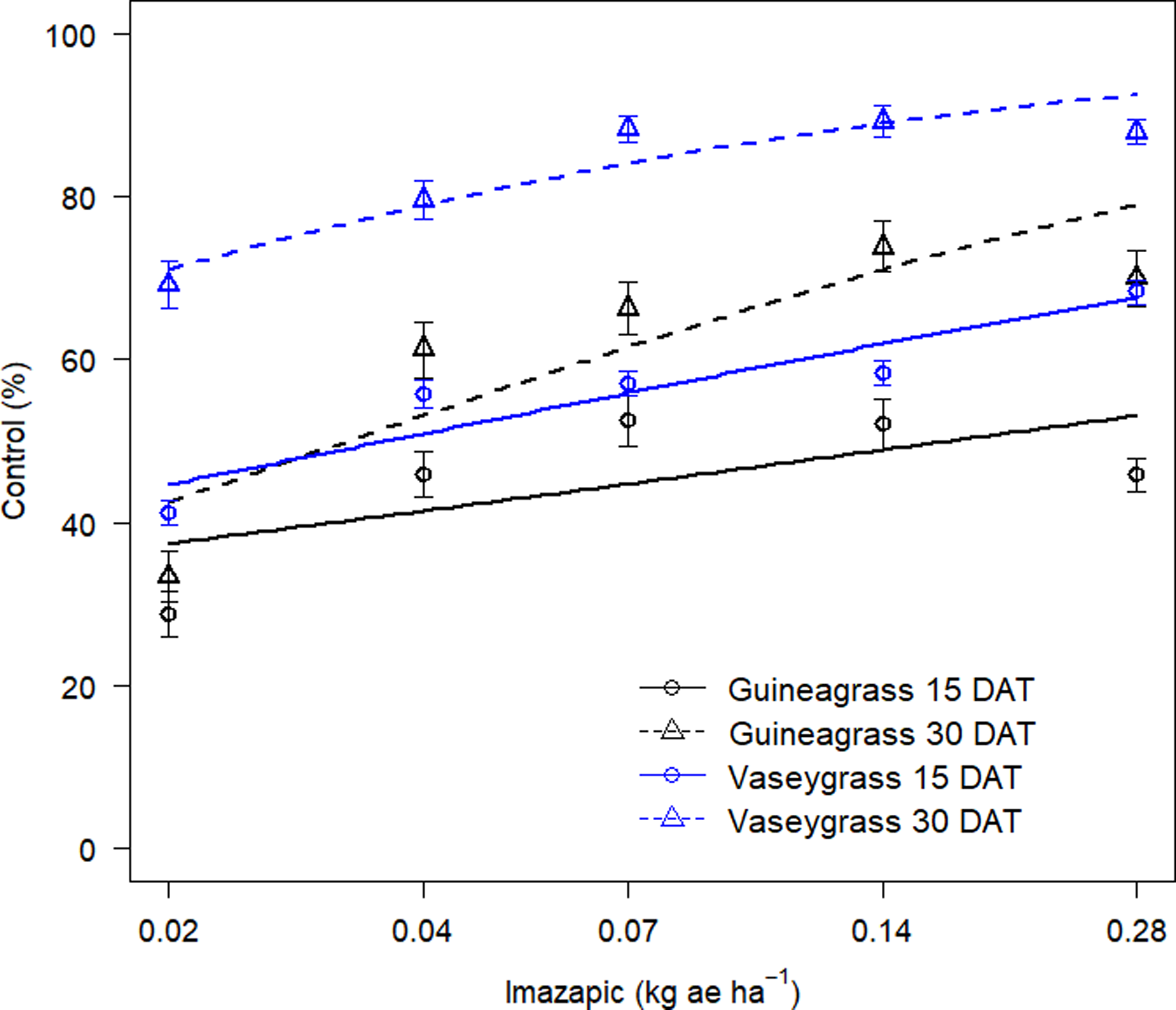

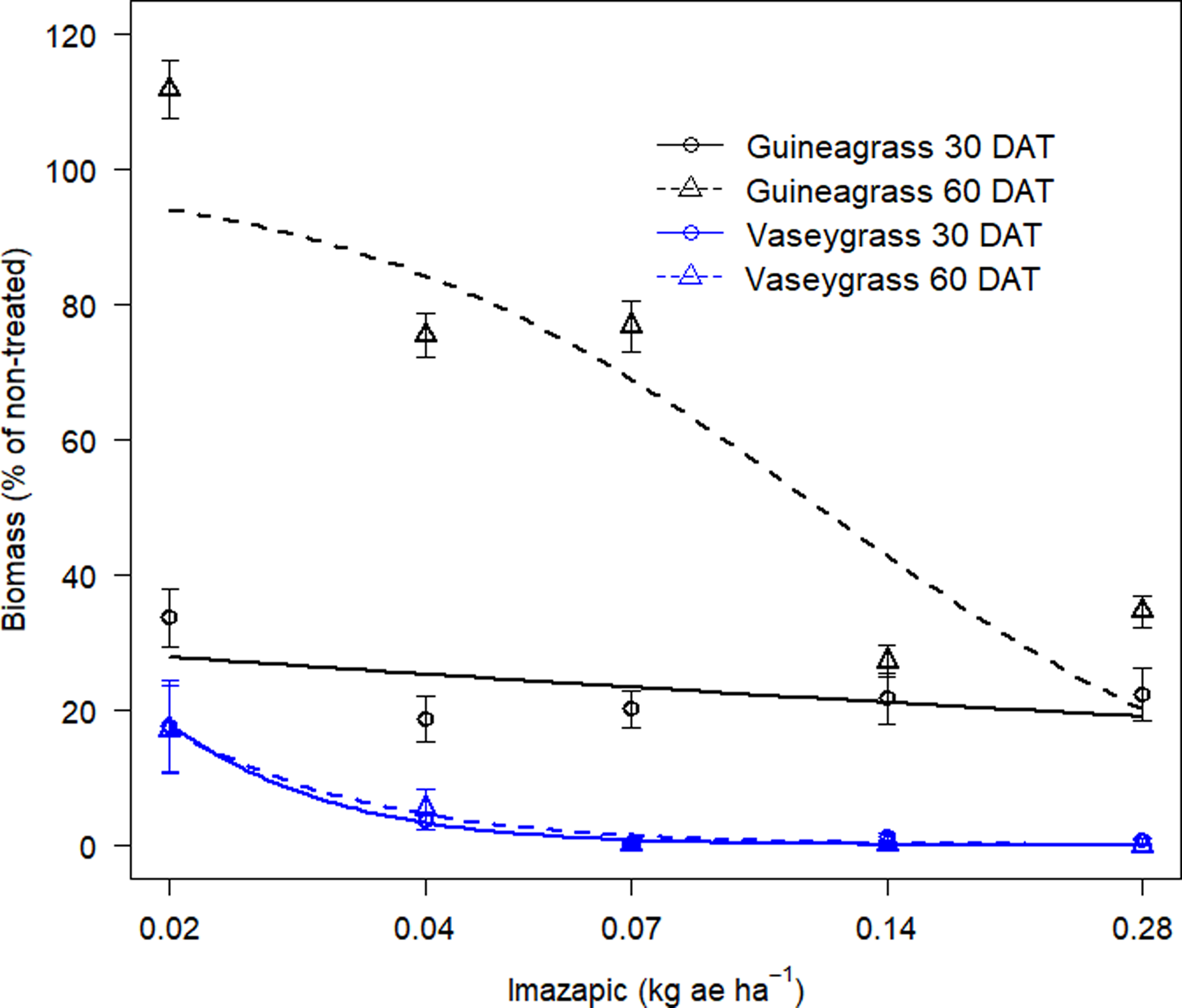

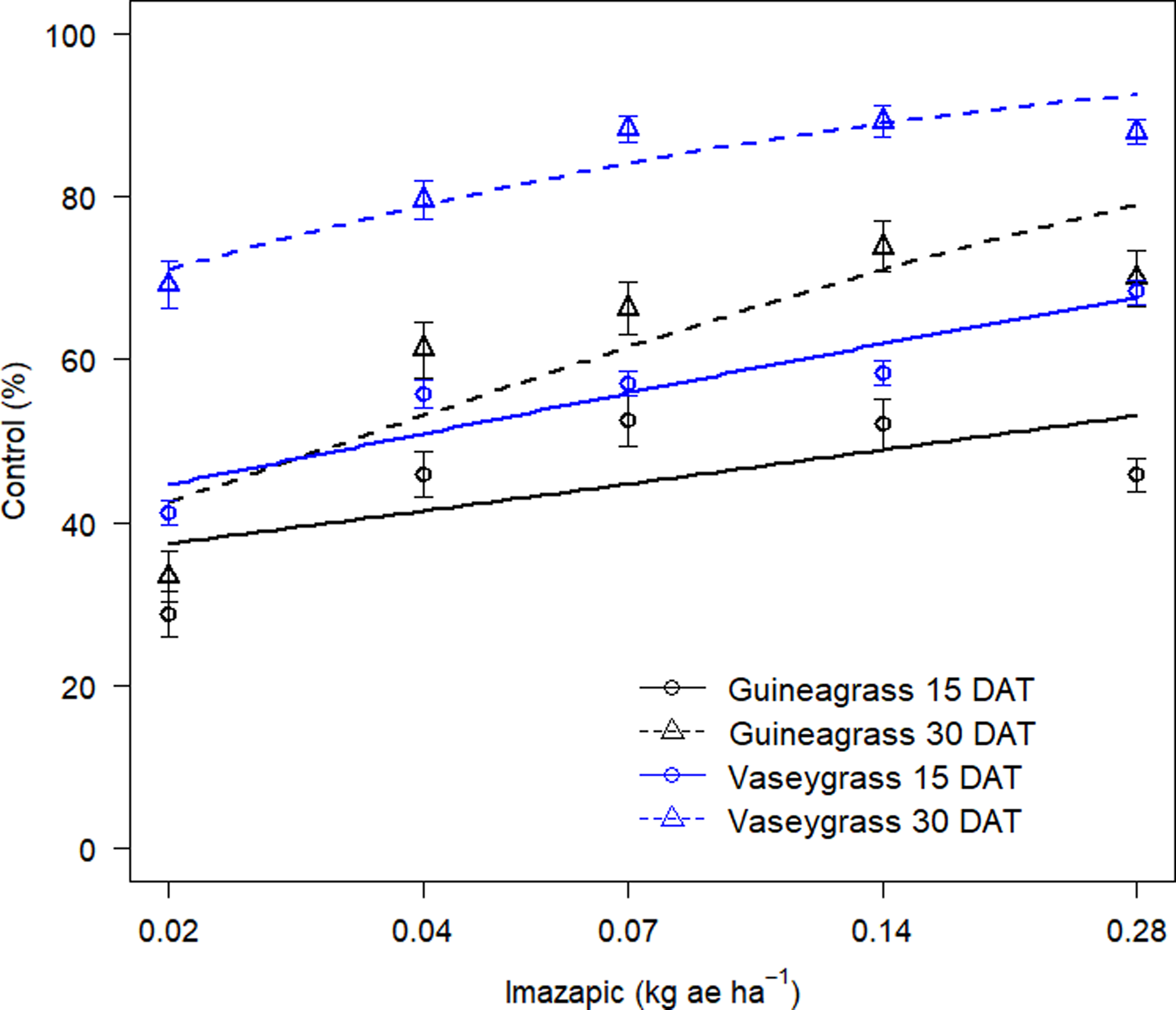

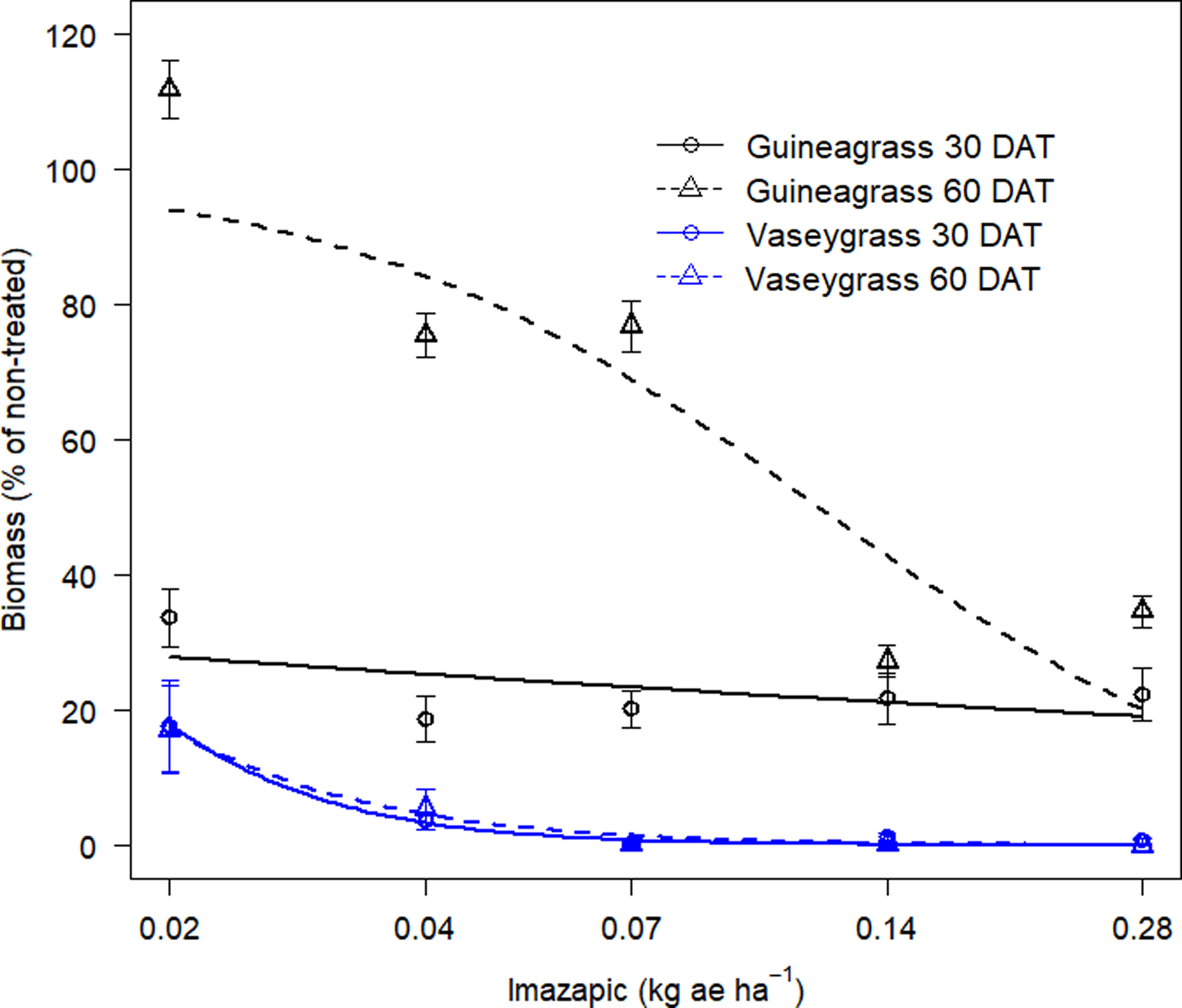

There was no Imazapic × Experimental Run effect for either grass species’ visual estimates of control or biomass. Increasing imazapic rates substantially affected visual estimates of control for both guineagrass and vaseygrass (Table 2; Figure 3). Imazapic at >0.04 kg ae ha−1 caused the most damage to guineagrass and vaseygrass at 15 and 30 DAT. In addition, the effective imazapic rate needed to obtain ED80 guineagrass control was 52.7 and 0.31 kg ae ha−1, while for vaseygrass, the effective imazapic rate was 1.71 and 0.05 kg ae ha−1 15 and 30 DAT, respectively. Biomass ED80 values showed that guineagrass required imazapic rates of 0.20 and 0.28 kg ae ha−1 for biomass reduction 30 and 60 DAT, respectively, whereas vaseygrass required an imazapic rate of 0.019 kg ae ha−1 at both sampling times (Table 2; Figure 4). However, the ED80 imazapic dose requirements for guineagrass control are above the evaluated rates.

Figure 3. Visual estimates of control (%) of guineagrass and vaseygrass at 15 and 30 DAT in response to imazapic rates under greenhouse conditions in 2017 and 2018. Solid and dashed lines represent predicted values. Data were fit to a three-parameter log-logistic regression model, Y = 0 + {d − 0/1 + exp[b(log(x) − log(e)]}, where Y is visual estimates of guineagrass or vaseygrass control, x is glyphosate application rate (kg ae ha−1), b is the relative slope at the inflection point, d is the upper limit of the curve, and e is the fitted line’s inflection point (ED80).

Figure 4. Biomass reduction (%) at 30 and 60 DAT of guineagrass and vaseygrass in response to imazapic rates under greenhouse conditions in 2017 and 2018. Solid and dashed lines represent predicted values. Data were fit to a three-parameter log-logistic regression model, as described in Figure 3.

The results indicate that higher rates of imazapic are needed for guineagrass control, whereas lower rates are required for vaseygrass. However, these rates are relatively high for broadcast applications in the field because imazapic has been shown to damage bermudagrass. Grichar et al. (Reference Grichar, Baumann, Baughman and Nerada2008) reported ‘Coastal’ bermudagrass injury of 73% to 87% with imazapic rates of 0.2 and 0.24 kg ae ha−1, respectively, when broadcast in a bermudagrass pasture. Lemus and White (Reference Lemus and White2015) also reported a yield decrease in bermudagrass of 43% from applications of imazapic at 0.23 kg ae ha−1 applied before green-up. Therefore spot application of imazapic should be considered to target guineagrass and limit bermudagrass damage.

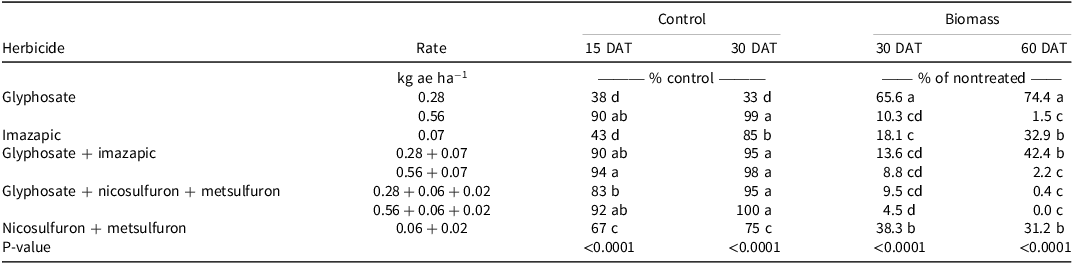

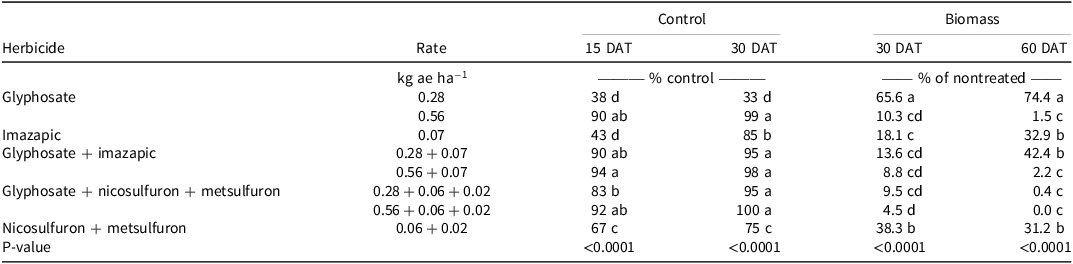

There was no Glyphosate Tank Mix × Experimental Run effect for guineagrass control and biomass. Visual estimates of guineagrass control were greatest with glyphosate at 0.56 kg ae ha−1, glyphosate + imazapic, or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron (>90%) 15 and 30 DAT. Guineagrass control was lowest with glyphosate at 0.28 kg ae ha−1 (38%) and imazapic (43%) 15 DAT and glyphosate at 0.28 kg ae ha−1 30 DAT (Table 3). Guineagrass biomass with imazapic or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron was at least 20 times greater than that treated with glyphosate at 0.56 kg ae ha−1 60 DAT. However, adding these active ingredients with glyphosate at 0.56 kg ae ha−1 resulted in similar biomass. These data indicate that glyphosate alone at 0.56 kg ha−1 effectively controls guineagrass and that additional active ingredients are not required. There is little published information regarding the control of guineagrass in forage systems. However, the sensitivity of guineagrass to glyphosate demonstrated in the glyphosate-only experiment and glyphosate tank-mix experiment supports the commonly recommended spot treatment with glyphosate for this species (Sellers et al. Reference Sellers, Smith and Ferrell2025).

Table 3. Effect of herbicide tank mixes on guineagrass under greenhouse conditions in Ona, FL, in 2017 and 2018.a,b,c

a Means followed by the same letter within columns are not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05.

b Abbreviation: DAT, days after treatment.

c Nontreated guineagrass biomass averaged 11.1 and 10.1 g (dry weight) at 30 and 60 DAT, respectively, over all three experimental runs.

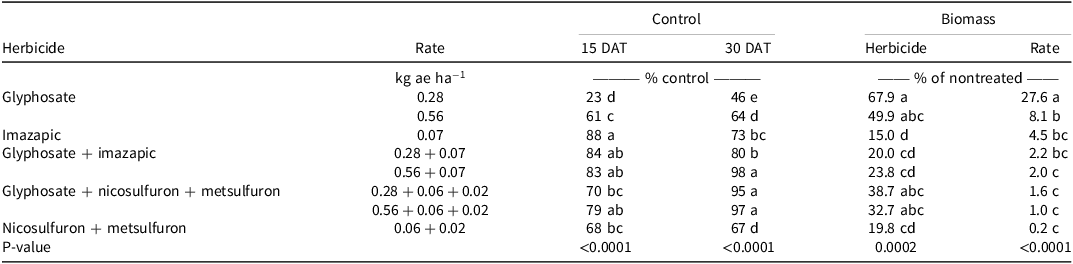

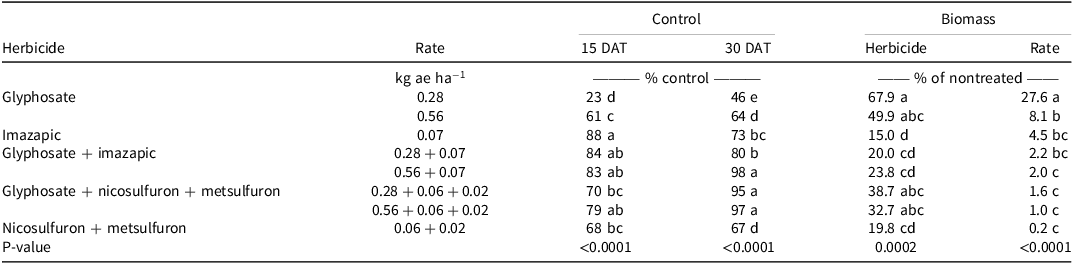

There was no Glyphosate Tank Mix × Experimental Run effect for vaseygrass control and biomass. Imazapic resulted in the greatest (88%) vaseygrass control at 15 DAT, but the level of control was not different from glyphosate + imazapic treatments or the high rate of glyphosate + nicosulfuron + metsulfuron (Table 4). By 30 DAT, treatments with glyphosate at 0.56 kg ae ha−1 + imazapic and either rate of glyphosate + nicosulfuron + metsulfuron provided at least 95% control, and this was at least 1.3 times greater than control observed with either rate of glyphosate, imazapic, or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron alone. Vaseygrass biomass was greatest with glyphosate at the low rate of 30 DAT and was at least 1.4 times greater than all other treatments. By 60 DAT, biomass in all treatments was <28% of the nontreated control, indicating that all treatments can significantly suppress vaseygrass. Unlike guineagrass, adding other active ingredients to glyphosate may enhance vaseygrass control, especially if a low rate of glyphosate is utilized. These results are consistent with Twidwell et al. (Reference Twidwell, Strahan and Granger2014), who reported that nicosulfuron + metsulfuron and glyphosate + nicosulfuron + metsulfuron provided 58% to 78% control after 2 consecutive yr of treatment. Furthermore, Jeffries et al. (Reference Jeffries, Travis and Yelverton2017) reported that nicosulfuron + metsulfuron applied to not mowed vaseygrass resulted in 80% cover reduction 52 wk after treatment.

Table 4. Effect of glyphosate and glyphosate tank mixes on control of vaseygrass under greenhouse conditions in Ona, FL, in 2017 and 2018.a,b,c

a Means followed by the same letter within columns are not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05.

b Abbreviation: DAT, days after treatment.

c Vaseygrass biomass removed from nontreated pots averaged 8.9 and 6.9 g (dry weight) at 30 and 60 DAT, respectively, over all three experimental runs.

Practical Implications

Applying glyphosate, imazapic, and/or nicosulfuron + metsulfuron provides efficient long-term control of bahiagrass and vaseygrass. Glyphosate at 0.56 kg ae ha−1 controls guineagrass effectively, and ranchers can save on herbicide costs by applying at this rate, because applying at higher rates results in similar control. Guineagrass is tolerant to imazapic; therefore higher rates are required for adequate control; ranchers need to spot apply the herbicide to minimize bermudagrass injury at high rates. Future studies need to investigate the susceptibility of hybrid bermudagrass cultivars to these rates and tank mixes, and vaseygrass and guineagrass field studies should be conducted to validate the greenhouse results.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch Project no. 10006034.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.