Introduction

Conversion and degradation of wetlands, through waterworks such as reclamation of shallows, and the construction of dams and drainage canals, have in many parts of the world largely reduced and altered natural wetlands, especially inland wetlands (Davidson Reference Davidson2014; Fluet-Chouinard et al. Reference Fluet-Chouinard, Stocker, Zhang, Malhotra, Melton and Poulter2023). Nowadays in inland Western Europe, only remnants exist of muddy freshwater landscapes subject to tides, such as estuaries and riverine flood-plains (Čížková et al. Reference Čížková, Květ, Comín, Laiho, Pokorný and Pithart2013; Verhoeven Reference Verhoeven2014). Freshwater mudflats must historically have been extensive because river discharges fluctuated naturally between years creating nutrient-rich silty mudflats (Wolff Reference Wolff1993). These mudflats were important feeding habitat for waders in addition to marine tidal flats and still are in some areas of the world (Meissner et al. Reference Meissner, Karlionova and Pinchuk2011). Many wader species that predominantly use marine habitats also feed in large numbers in nutrient-rich freshwater ecosystems if available. Examples are avocets (Boula Reference Boula1986; Hötker and West Reference Hötker and West2005), Bar-tailed Godwits Limosa lapponica (Duijns et al. Reference Duijns, van Dijk, Spaans, Jukema, de Boer and Piersma2009), and Dunlins (Colwell and Dodd Reference Colwell and Dodd1997; Conklin et al. Reference Conklin, Colwell and Fox-Fernandez2008). Indeed, these species rarely stop over in substantial numbers in inland Western Europe nowadays (Hooijmeijer et al. Reference Hooijmeijer, van der Burg and Poutsma2010), due to a lack of freshwater mudflats.

An important current topic in the field of biological conservation is the function of artificial wetlands as alternative bird habitats (see Li et al. Reference Li, Chen, Lloyd, Zhu, Shan and Zhang2013), initiating studies on (management) factors influencing bird abundance (see Bolduc and Afton Reference Bolduc and Afton2008; Toral et al. Reference Toral, Aragonés, Bustamante and Figuerola2011; Voslamber and Vulink Reference Voslamber and Vulink2010). Examples are rice-fields (Lourenço and Piersma Reference Lourenço and Piersma2009; Maeda Reference Maeda2001), fish-ponds (Sebastián-González and Green Reference Sebastián-González and Green2016), and water reservoirs (Rajpar et al. Reference Rajpar, Ahmad, Zakaria, Ahmad, Guo and Nabi2022). Many of artificial habitats were not intentionally created for bird conservation but thrive under suitable management such as Oostvaardersplassen in the Netherlands (Vonk et al. Reference Vonk, Rombouts, Schoorl, Serne, Westerveld and Cornelissen2017; Vulink and van Eerden Reference Vulink, van Eerden, WallisDeVries, Bakker and Van Wieren1998). Others are too small and may have lower ecological value than nearby natural areas (Almeida et al. Reference Almeida, Sebastián-González, dos Anjos and Green2020; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Li, Jing, Tang and Chen2004). Successes with artificial and restored wetlands that specifically mitigated the loss of freshwater mudflats and shallows (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Cai, Li and Chen2010) have evoked new initiatives.

Recently an inspiring new wetland has been created in the inland IJsselmeer region in the Netherlands: a large-scale archipelago of basins surrounded by sandy levees and gullies made of locally sourced (dredged up) silt and sand from the lake bottom (de Rijk et al. Reference de Rijk, van Kessel, Klinge, Noordhuis, de Leeuw, Vervaart and IJff2022; Irwin Reference Irwin2023; van Leeuwen et al. Reference van Leeuwen, Temmink, Jin, Kahlert, Robroek and Berg2021). The archipelago, named Marker Wadden, lies 3 km from the nearest shores of the 700 km2 large freshwater lake, and is subject to irregular floods due to wind tide. An essential part of the design of Marker Wadden is the silt-filled basins, with shallows, providing gradual land–water transitions (Jin et al. Reference Jin, Van de Waal, van Leeuwen, Lamers, Declerck and Amorim2023). This led to the availability of a wealth of macroinvertebrates (van Leeuwen et al. Reference van Leeuwen, de Leeuw, Volwater, van Keeken, Jin and Drost2023; Verkuil et al. Reference Verkuil, Dreef, van Leeuwen, van der Winden and Bakker2024) in shallows and freshwater mudflats that serve as feeding habitats for waders (Verkuil et al. Reference Verkuil, Dreef, van Leeuwen, van der Winden and Bakker2024). The design is innovative with different types of basins which have proved their value for staging and breeding waterbirds (van der Winden et al. Reference van der Winden, Dreef, Posthoorn and Verkuil2024). The shallows were very attractive from the start of the construction, especially for Pied Avocets Recurvirostra avosetta. However, the pristine bare sandy landscape with mudflats slowly got more vegetated and overgrown. From a conservation point of view, Pied Avocets are an attractive species for which to study the impacts of the creation of an artificial wetland and its differences in (basin) design and phasing. Pied Avocets can be common in freshwater wetlands but have declined in numbers much more in this habitat type than in marine environments; currently the inland staging populations depend on small water-bodies scattered all over Europe (Hötker and West Reference Hötker and West2005). The Netherlands holds a substantial part of the European staging population, but the Dutch staging birds are of conservation concern (Sovon 2023).

Our main objective was to study the impact of habitat development on Pied Avocet numbers in a developing artificial wetland. Understanding the processes that can create and maintain suitable foraging habitat for waders in artificial habitats is important for wetland conservation. The development of the archipelago created the opportunity to empirically investigate differences in design and the phasing of construction over seven years. In this study we specifically quantified changes in Pied Avocet numbers in relation to vegetation development, water-level induced changes in habitat characteristics, and colonisation by raptors. The expectation was to identify the factors influencing habitat suitability that could contribute to optimising future artificial wetlands for waders such as Pied Avocets.

Methods

We (1) monitored the numbers of Pied Avocets, and (2) measured habitat characteristics, both remotely and on the ground, including the presence of raptors, and (3) modelled the joint effects of basin design, basin age, basin size, and habitat characteristics on avocet abundance.

Study species

Pied Avocets (avocets from here onwards) forage in Europe in marine, brackish as well as freshwater shallows in coastal and inland wetlands (Enners et al. Reference Enners, Chagas, Ismar-Rebitz, Schwemmer and Garthe2019; Hötker Reference Hötker1999; Joest et al. Reference Joest, Hälterlein, Klinner-Hötker, Cimiotti and Krahn2021; Moreira Reference Moreira1995). During the northern winter, avocets are scarce in north-western Europe; most individuals are present from April until October (Smith and Piersma Reference Smith, Piersma, Boyd and Pirot1989). The Netherlands offers abundant feeding habitat for 12,000–17,000 avocets in the Wadden Sea and Dutch Delta region, and scarce patches of inland wetlands (Sovon 2023). Notably, high numbers (2,000–9,500) were also reported from the IJsselmeer region in the 1970s when new polders were developed and famous wetlands such as Oostvaardersplassen provided freshwater habitat for avocets for a while (de Bie and Zijlstra Reference de Bie and Zijlstra1985). After changes in these nature reserves, avocet numbers declined. The IJsselmeer region had not supported similar internationally important staging numbers, until Marker Wadden was constructed.

Study area

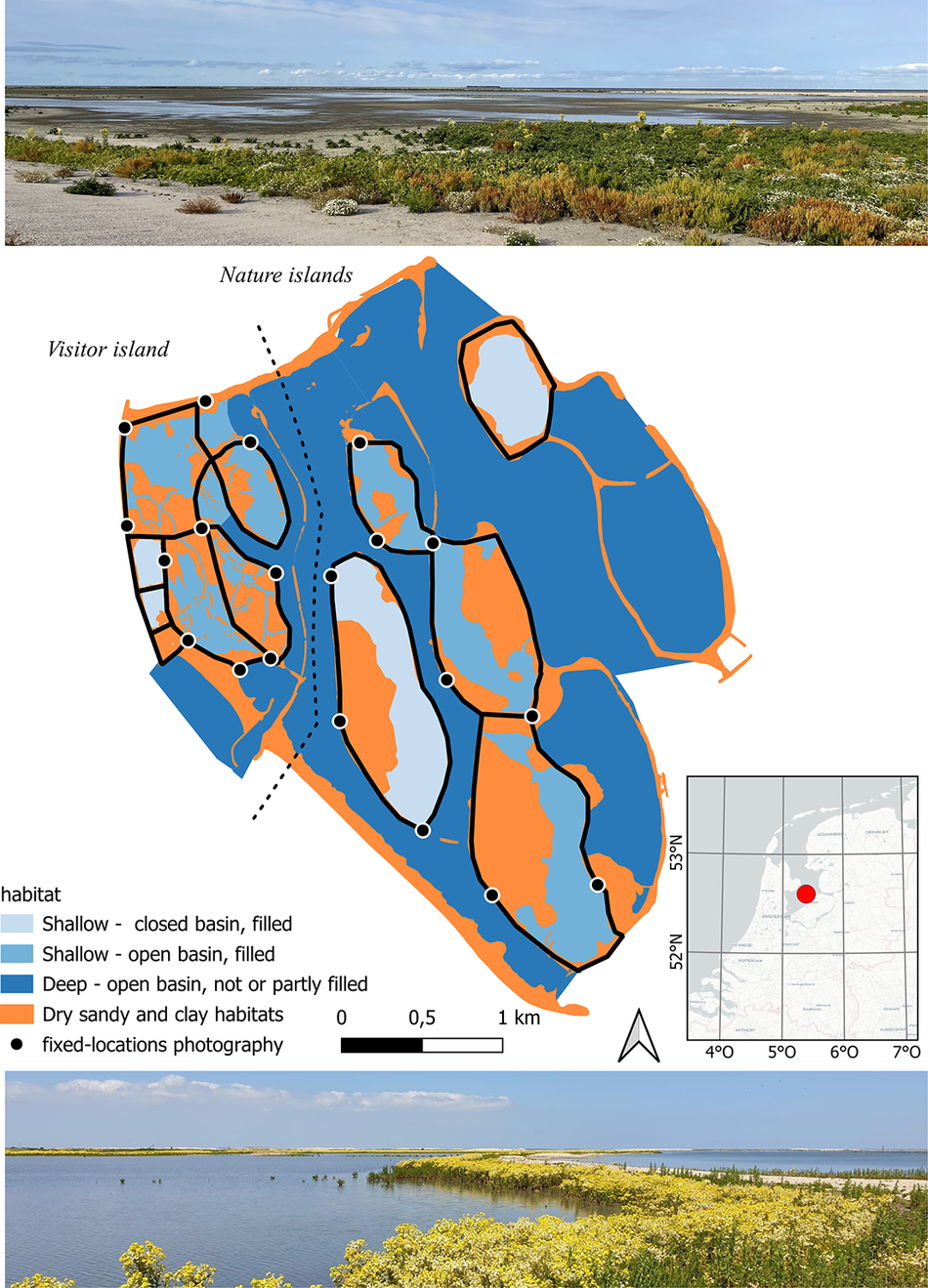

Marker Wadden is a human-made archipelago in the Netherlands (52°35′N, 5°22′E), situated in the 700-km2 freshwater lake Markermeer about 3 km from the mainland (Figure 1) (Irwin Reference Irwin2023). It consists of an aggregation of subunits, or basins, surrounded by sandy levees, mostly filled with clay and silt. Construction of the archipelago started in late 2016. The first basin-complex was completed in 2021, and the last in 2021–2023. Therefore pristine, bare mudflats were present in 2017, 2018, and 2021. By 2023 the archipelago covered over 1,000 ha. The visitor island (western basins) has trails, a harbour, a visitor centre, a handful of holiday homes, and a research station. The basins completed in 2018 (central basins) and 2021 (eastern basins) form the so-called nature islands which are strictly closed for the public.

Figure 1. Marker Wadden situated in lake Markermeer in the Netherlands (52°35′N, 5°22′E). The types of basins (closed or open) comprising the archipelago in 2023 are indicated. Of the shallow, filled basins included in this study (outlined in black; n = 12), the levees were either breached (creating open basins) or remained intact (closed basins). Fixed photography locations are shown as black dots. Marsh fleawort Tephroseris palustris is the dominant vegetation. Top: closed basin in May 2022; bottom: open basin in May 2021.

Construction and design of the archipelago

The basins that were filled with clay and silt had largely unbroken levees during the first years after construction, but many levees were breached after 1–2 years to allow permanent flooding. The open silt-filled basins are in contact with the open waters of the gullies of the archipelago, and thus the Markermeer. In these open basins, water levels follow the human-controlled water levels of lake Markermeer (low in winter, higher in summer). The silt-filled basins that remained closed (because of specific habitat development aims, mostly reedbeds) have a more natural seasonal differences in water level due to rainfall and evaporation (higher in winter, lower in summer), although some lake water was pumped in early spring in some years in one basin.

Habitat for avocets

Three major design/habitat types have been available for foraging waders (Figure 1). (1) Permanently closed, filled basins with mudflats subject to semi-natural minor fluctuations in water level (by 2023 n = 5). Here the extent of feeding habitat mostly varies with vegetation cover and rainfall/evaporation. (2) Open, filled basins with mudflats and subject to substantial irregular water level fluctuations due to wind tide in the lake (by 2023 n = 7). Here the extent of mudflats depends on the water level equal of lake Markermeer. (3) Open basins with shallow or deep water (lagoons and gullies) with sandy shores and no mudflats. Since the number of avocets using lagoon and gully shores was very low, only filled basins were used in the analyses.

Study design

In 2017 we started waterbird counts of the entire archipelago, monthly from 2018 onwards, and in 2020 monthly standardised photography was added. Satellite images were annually available for 2018–2022. We quantified the effect of habitat characteristics on the presence of avocets during peak presence in May–July. Data sets used were:

-

• 2017–2023: counts of foraging avocets (monthly during general presence in March–October);

-

• 2018–2022 (2023 not available): quantification of vegetation cover and surface wetness of each basin using satellite images (May–July); with estimates of the extent of mudflats for 2018 and 2022 using field notes;

-

• 2020–2023: quantification of vegetation density and water cover of each basin with standardised 4-directions photographs on the ground at 20 fixed locations (May–July).

We then tested how developments in the use of the archipelago by avocets correlated with the vegetation and water surface development of the filled basins (n = 12) (Figure 1).

Bird counts

The number of avocets and raptors staging on Marker Wadden were monitored following the field protocols of Wetlands International (2010). Each basin was counted separately, by foot and small boats during daylight hours. Raptor numbers were summed for the entire archipelago because they moved between basins. Survey groups kept in contact to be able to correct for avocet movements. Additional to the monthly counts, from mid-April to mid-August, the number of avocets was counted weekly per basin. We also scored their behaviour in four categories: foraging, resting, breeding, and alarming (off nest); this was used to assess the correlation between numbers feeding and total numbers present (Supplementary material (SM) Figure S2).

Habitat scoring

We quantified the availability of potential feeding habitat per basin in the months most avocets feed on Marker Wadden using two independent sources, i.e. satellite images and on-the-ground fixed-location photography.

Satellite images were obtained from the Copernicus website (https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/, pre-processed sentinel 2A-L2a images). Image pixel resolution was 30 × 30 m. A scene classification based on reflective characteristics of RGB channels (https://custom-scripts.sentinel-hub.com/sentinel-2/scene-classification/) was used as a crude land-cover map. For each year/month between April and August 2018–2022, 3–5 dates with complete coverage in cloudless conditions were available. Per basin, the proportion of pixels classified as “dry vegetated” was used to assess terrestrial vegetation coverage. We collected on-the-ground data on the mud–water mosaic as a proxy for water depth (see next section). Additionally, in Google Earth Pro, the polygon method was used to measure the size of the basins and the extent of shallows and mudflats in the basins in 2018 and 2022.

Standardised 4-directions photographs taken by observers on the ground at 20 fixed locations were used to verify habitat indices from satellite images. This approach made it possible to describe water and mudflat coverage and assess the vegetation coverage in more detail. Since 2020 four photographs (one in each cardinal direction) were taken each month at the 20 locations distributed evenly over the entire area (Figure 1). Basins had, depending on their size, one to three points with enough vantage to describe the basin. Photographs were analysed for May–July 2020–2023 (n = 384). Vegetation and water coverage were scored separately. From each photograph vegetation was scored in five categories: B1, mostly bare: 0–5% of surface covered with vegetation; B2, bare but encroaching: 5–20% of surface; C, closing but mostly bare: 20–50% of surface; D, dense but still some open patches: 50–90% of surface; E, everywhere: 90–100% of surface. Water coverage was scored in four categories: WF, wet and mostly flooded: 80–100% covered with water; WM, wet mosaic: 50–80% covered with water; DM, dry mosaic: 20–50% covered with water; DD, dry dominates: 0–20% covered with water. Data points are the number of on-the-ground points that fall into each category.

Data analyses

Pearson correlations coefficients between vegetation scores from satellite images and fixed-location photographs were calculated for the years where the two data sets overlapped: May–July 2020–2022 (see Figure S1). Based on results presented in SM1, the sum of vegetation categories B1 and B2 was used as an estimate of availability of bare sparsely vegetated soils, called soil bareness (four categories, available at 0–3 points). The water categories DM and WM were summed to a single variable approximating the availability of water–mud mosaic, called water mosaic (four categories, available at 0–3 points).

In all models assessing which factors determined the abundance of avocets in a basin, the number of avocets per monthly count is the dependent variable, the variation of which is assessed in space (basin ID, basin type, habitat characteristics) and time (year, age of basin), under raptor presence or absence. Linear regressions were used to test the expectation that the number of avocets feeding or resting in the basins linearly increases with the total number of avocets present.

We modelled the effect of different factors on avocet abundances in a mixed modelling glm framework. We tested Poisson models against negative-binomial (NB) models with or without zero-inflation to correct for potential overdispersion. We used the packages glmmTMB (Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Kristensen, Van Benthem, Magnusson, Berg and Nielsen2017) and DHARMa (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/DHARMa/). To test for multicollinearity, variance inflation factors (VIF) were determined for all covariates. To estimate effects of covariates we used models without intercept. Models were selected applying the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Residual plots and coefficients (tables and plots) are available in SM2. Differences between models were assessed with analysis of variation (ANOVA).

In modelling step A, the habitat characteristic included was vegetation cover as measured with satellite images (data April–August 2018–2022). The full model included the following fixed factors: vegetation cover (% vegetated pixels), basin design (open/closed), basin age (years), size (ha), and raptors (presence/absence); random (crossed) effects were year, month, and basin ID.

In modelling step B, habitat factors measured with fixed-location photography were applied (data May–July 2020–2023). Based on the results of modelling step A, we used NB linearised mixed models. We stated that basin age accounted for habitat succession, including (increasing) vegetation cover. The full model included water–mudflat mosaic and soil bareness (four categories each), basin age, design, size, and presence/absence of raptors as fixed factors; random (crossed) effects were year, month, and basin ID.

Results

Avocet abundance

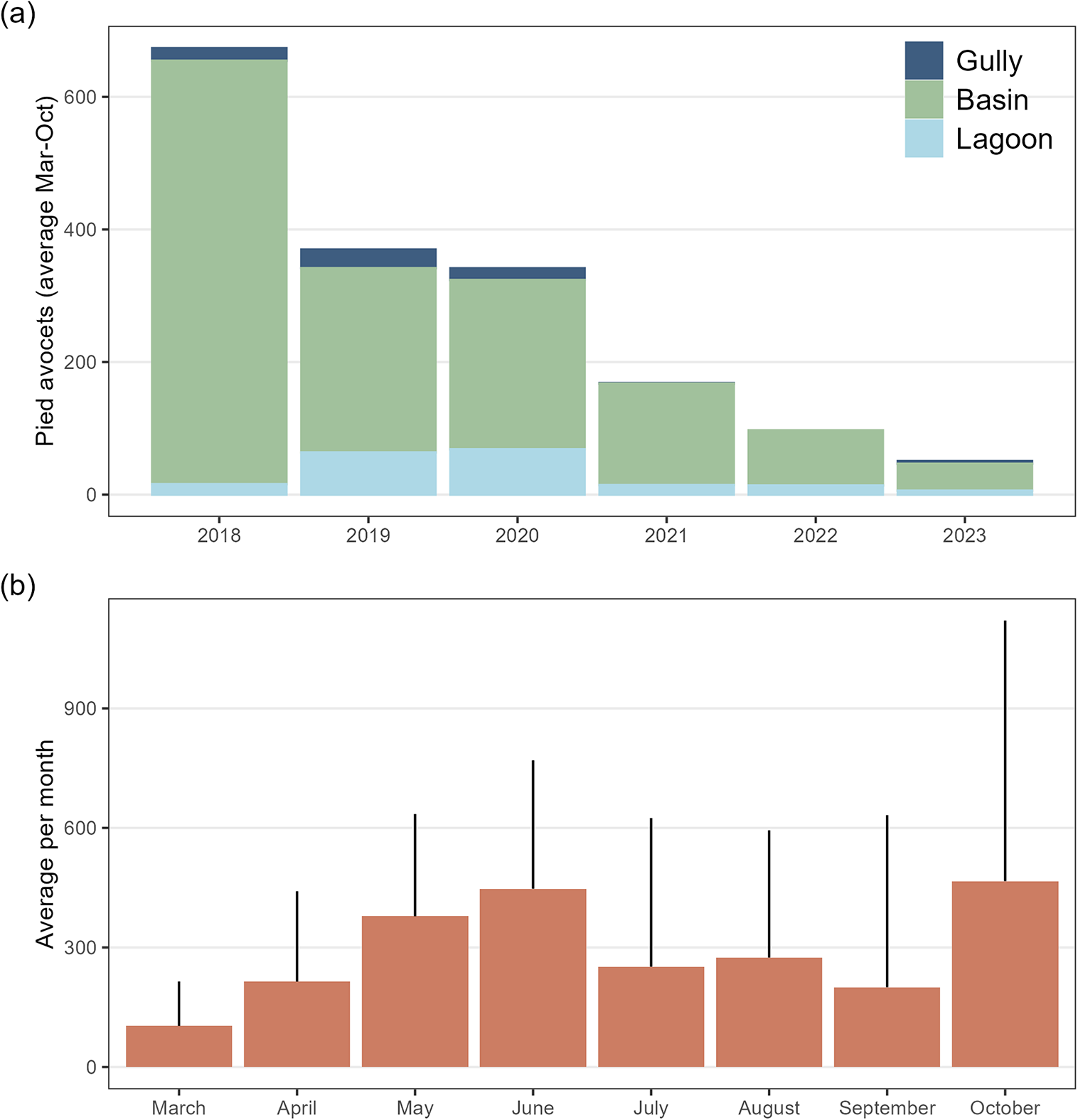

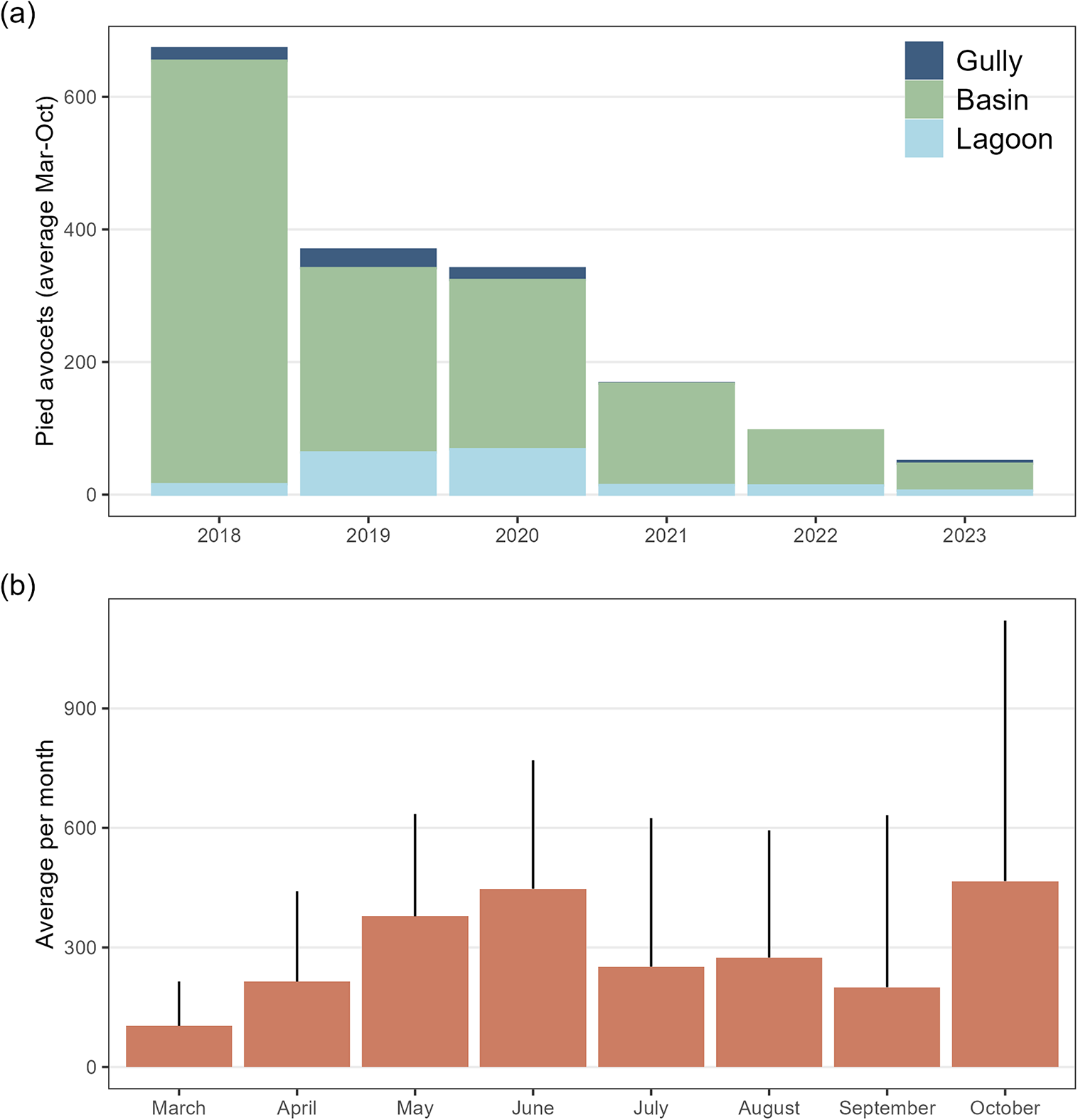

Avocets were present on Marker Wadden from March until September/October after which most birds left the area (Figure 2). The number of avocets was exceptionally high in 2018, immediately after construction of the archipelago, and only in this year high numbers were present until October. Avocets used the basins for feeding, and some nested on the islands. Since 2020, staging numbers have decreased strongly (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Population development (a); average number of Pied Avocets per year, and phenology (b) one average per month on Marker Wadden between 2018 and 2023.

Successional changes in basins

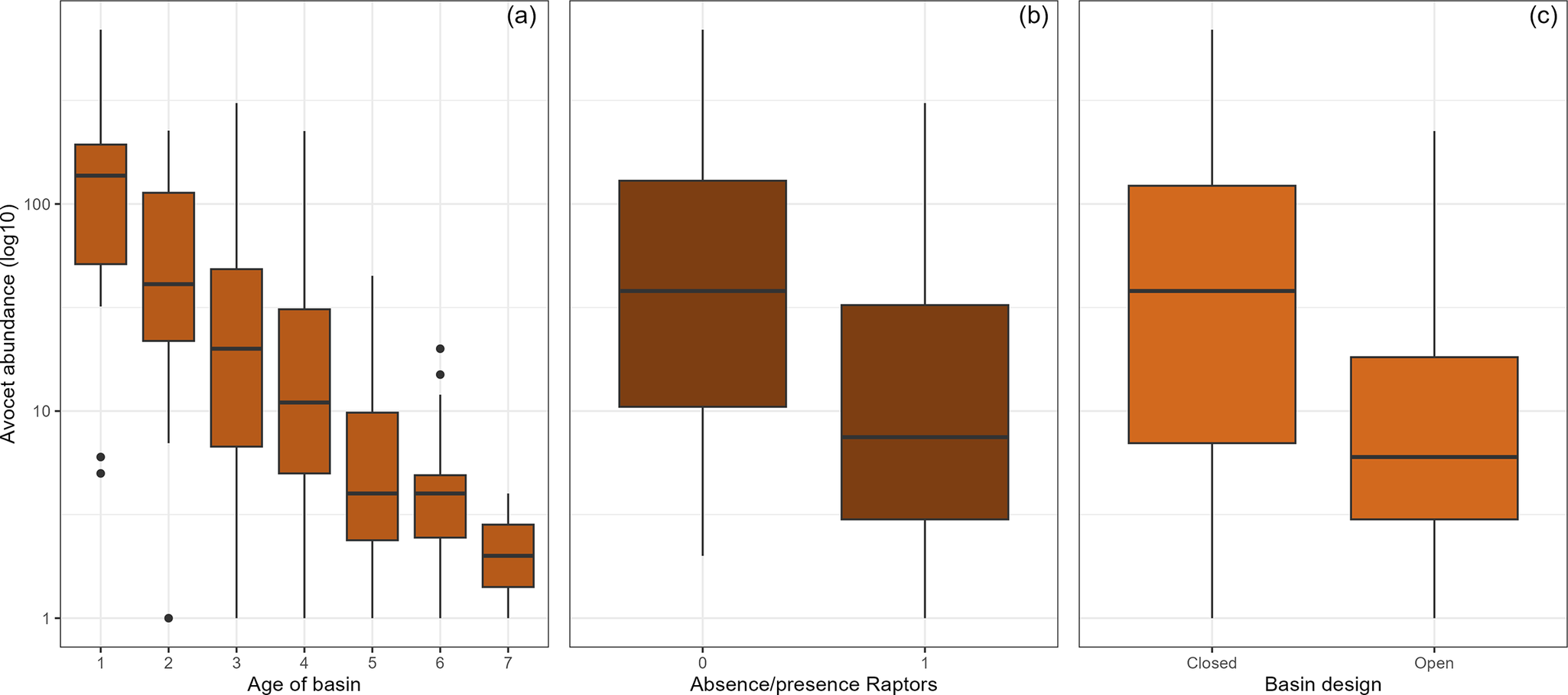

By 2022, the filled basins covered 780 ha of which 385 ha were shallows plus mudflats: 71% (110 ha) in closed basins and 29% (275 ha) in open basins. Both in open and closed basins, the vegetated surface area (as measured by the proportion of pixels assigned to vegetation greenness between 2018 and 2022) increased with basin age (Figure 3a). Overall, by 2022, almost 40% of the surface of the basins was vegetated with herbs and helophytes (e.g. marsh fleawort Tephroseris palustris; Figure 1). Compared with 2018, when all the basins were still closed, most unvegetated mudflats had disappeared by 2022, decreasing from 318 ha to 22 ha (Figure 3b). Fixed-location photography between 2020 and 2023 showed similar changes with age: a decrease in the water–mudflat mosaic and bare and sparse vegetated surface (Figure 3c and d). Between 2020 and 2023, the number of avocets decreased with the age of the basin (Figure 4a) and the presence of raptors (Figure 4b). Overall, the number of avocets appeared higher in closed than in open basins (Figure 4c).

Figure 3. Successional changes in the 12 basins used as feeding habitat by Pied Avocets in the human-made archipelago Marker Wadden. (a) Vegetation cover (% of 30 × 30 m pixels on satellite images) in relation to basin age for closed and open basins; box plots show median, 95% CI, and range. (b) Overall percentage of four habitat types estimated for 2018 and 2022, where the pixel category water is divided into water and mudflat. (c) Extent of mosaic of water and mudflats in relation to basin age (basin had 0, 1, 2 or 3 of 3 fixed points with mosaic, given is the mean proportion for each category). (d) Extent of (semi)bare soils in relation to basin age (basin had 0, 1, 2 or 3 points that were bare/open vegetation, given is the mean proportion for each category). Satellite data: May–August 2018–2022. Fixed-location photography: May–July 2020–2023. Photographs illustrate two fixed locations in (e) 2020 and (f) 2022, and (g) 2021 and (h) 2023.

Figure 4. Variation in the number of Pied Avocets using the archipelago basins in relation to (a) basin age, (b) presence or absence of raptors, and (c) basin design. Based on average (± SD) monthly counts of avocets in May through to July 2020–2023 (data used in modelling step B).

Factors predicting avocet abundance

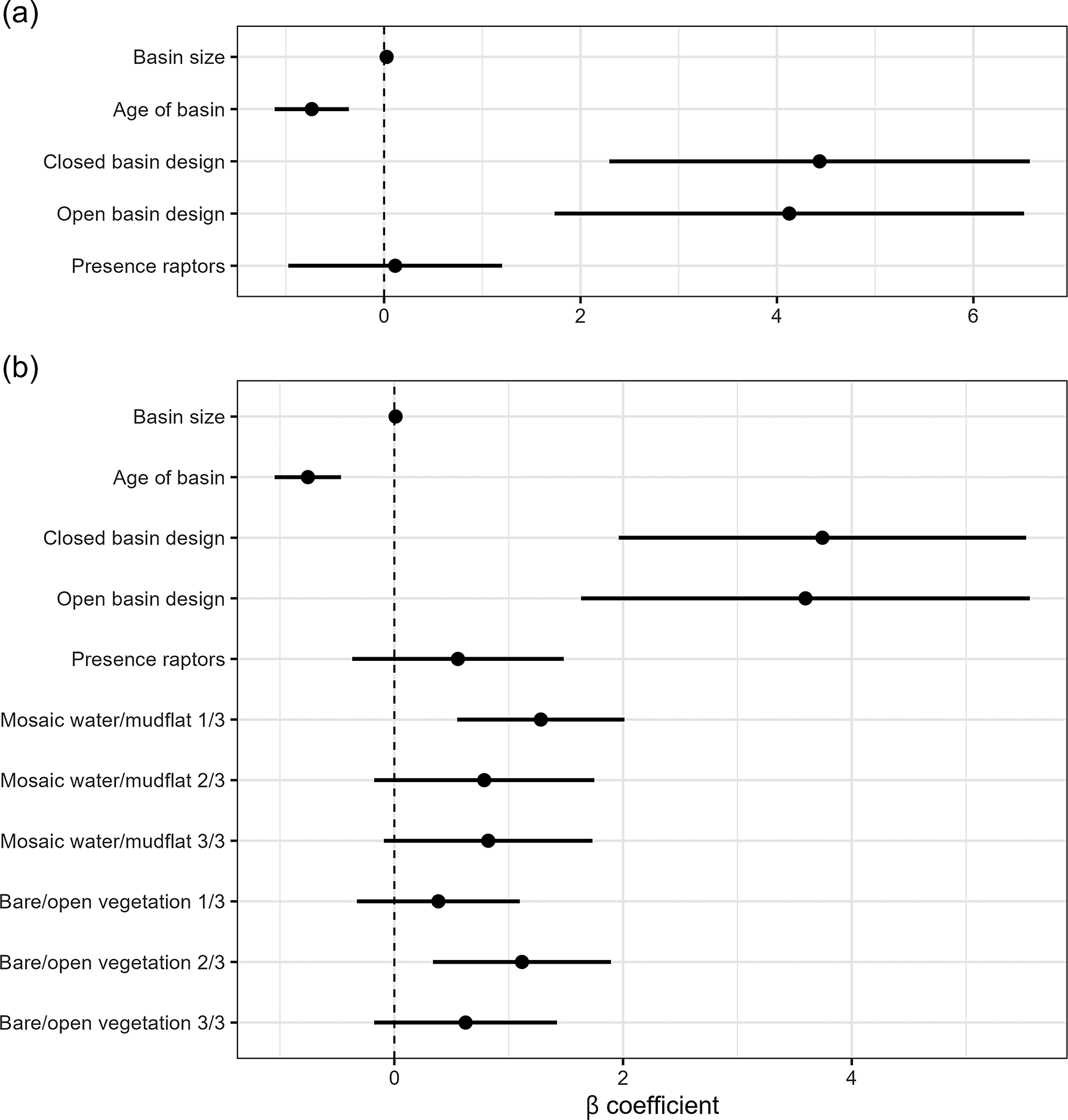

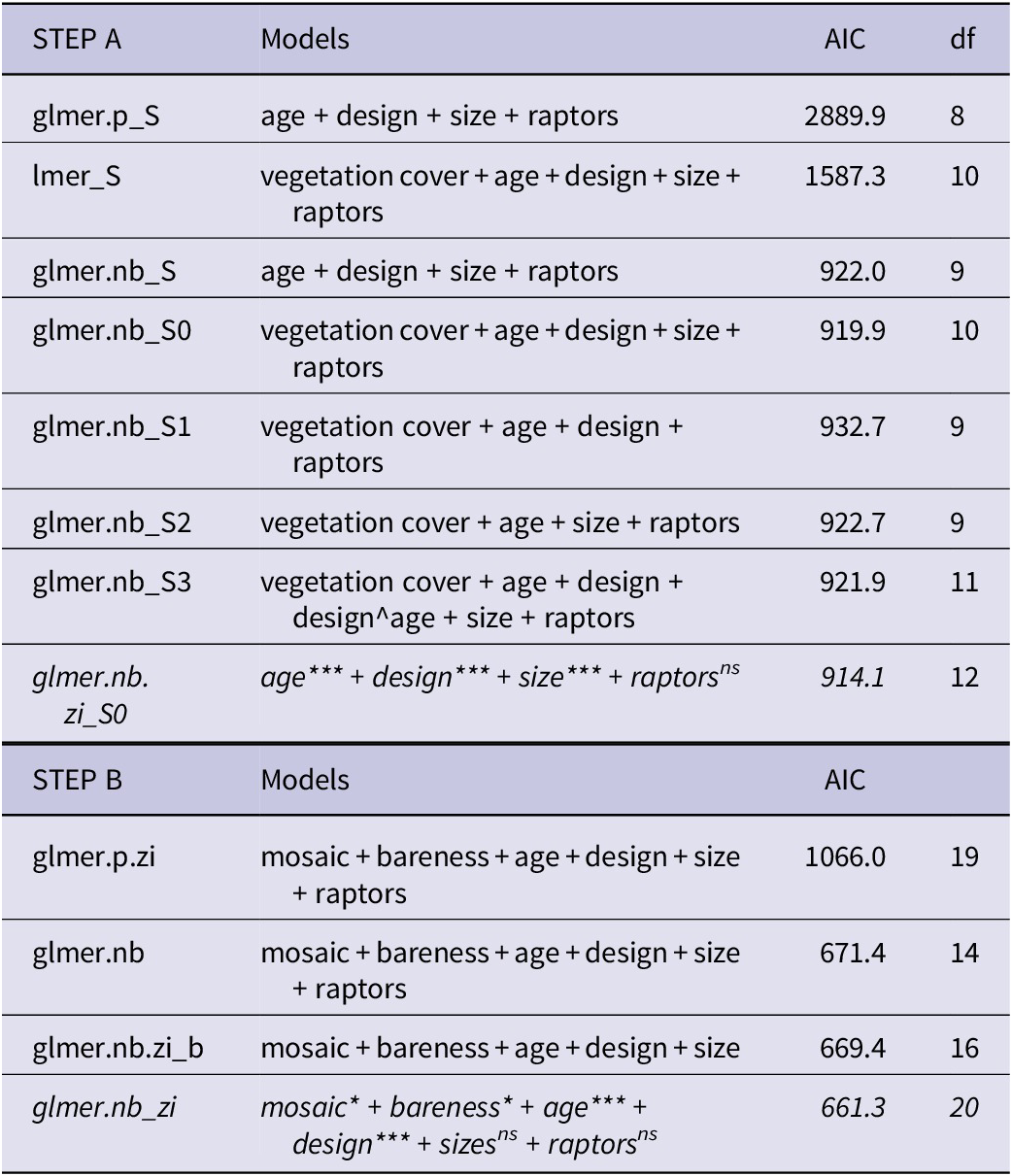

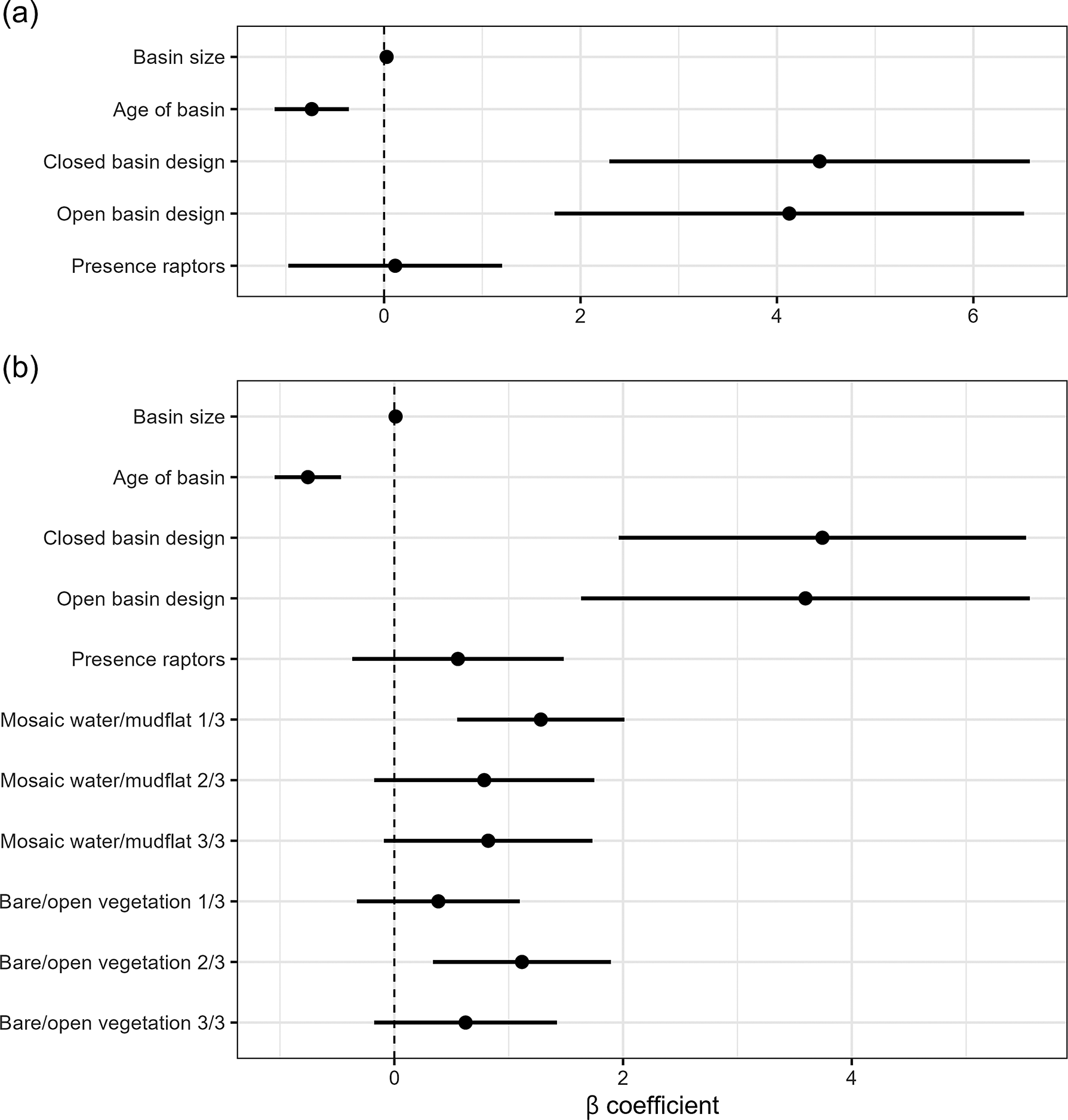

Modelling step A. The NB model had lower AIC values than a Poisson distributed model or a linearised mixed model and was significantly different (Table 1; X2 = 4.81, P = 0.03). Including zero-inflation effects improved the full model. Since vegetation cover strongly correlated with basin age (Figure 3a), only age was included in the final model; VIFs for the other covariates were <5, rejecting multicollinearity (SM2). This selected zero-inflated NB model had three significant predictors of abundance of avocet: basin age, basin size, and basin design (Table 1 and Figure 5a). Raptor presence was a non-significant factor. Basin age was used in step B as a measure of succession.

Table 1. Model results predicting avocet numbers. Modelling step A assessed the relative effects of the following fixed effects (in bold): basin age (years), vegetation cover (% pixels, measured by satellite imagery), basin design (open or closed), basin size (ha), and presence/absence of raptors (0/1). Step B assessed the following fixed effects (in bold): the specific habitat factors (proportion points, measured on the ground) water–mud mosaic and soil bareness, with basin age, design, size, and raptors. Random effects in all models were year, month, and basin ID, modelled as crossed effects: (1|year) + (1|month) + (1|basinID). Models were selected applying Akaike information criterion (AIC). Final models in italics; residual plots and coefficients (tables and plots) in Supplementary material 2

glmer = generalised linearised mixed model; lmer = linearised mixed model; p = Poisson distributed model; nb = negative binomial model; zi = model with zero-inflation effects on basin size and age. Significance of fixed effects: * P ≤0.05; ** P ≤0.01; *** P ≤0.001; ns signifies P >0.05.

Figure 5. Results of final models predicting differential use of the archipelago basins by Pied Avocets. Shown are the mean β coefficient and its standard error. (a) Model using satellite image data. (b) Model for on-the-ground fixed-location photography data.

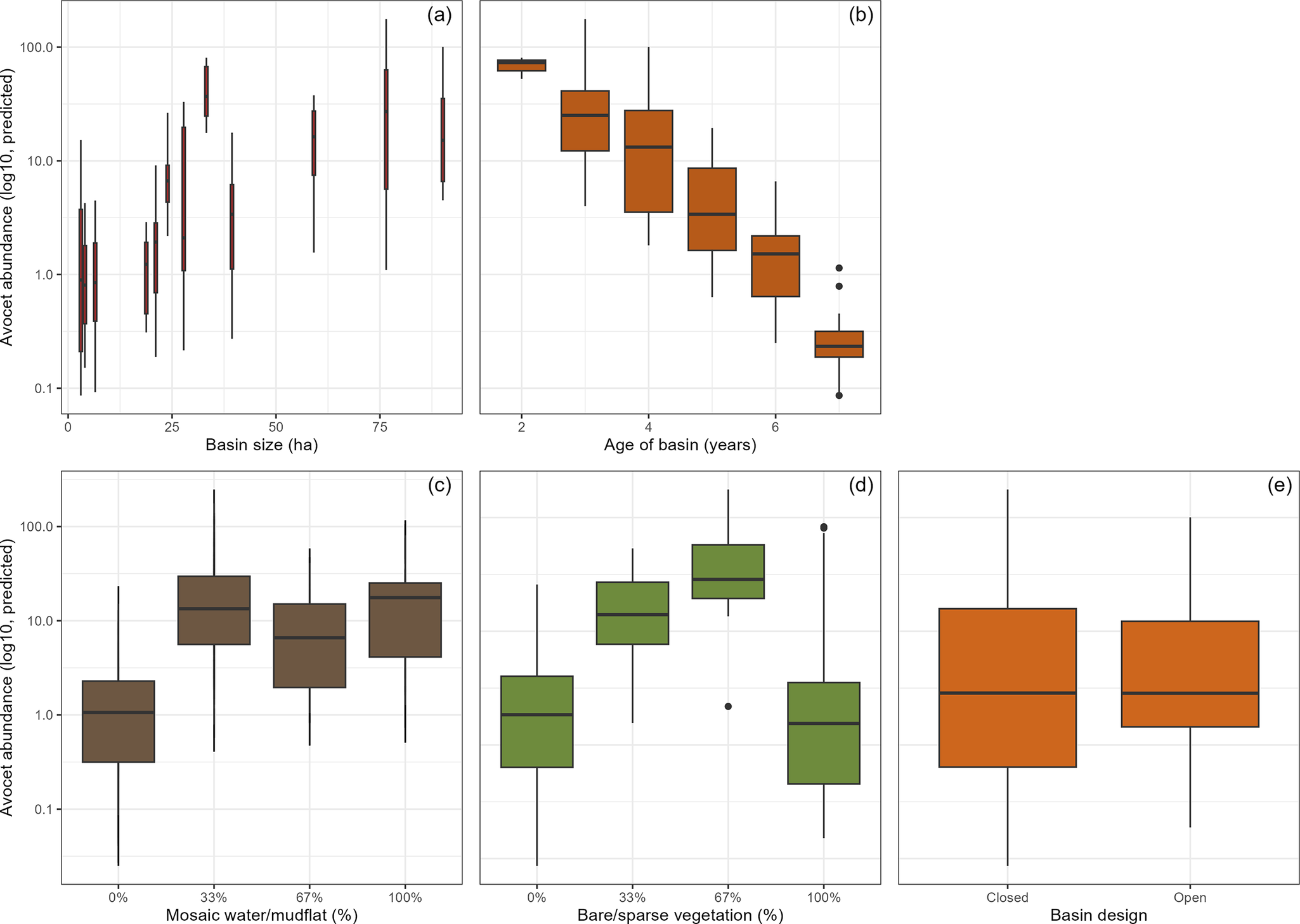

Modelling step B. Habitat characteristics quantified with fixed-location photography between 2020 and 2023 had VIFs <5 with the other covariates, rejecting multicollinearity (SM2). The NB zero-inflation model was significantly different from the other models (Table 1; X2 = 406.8, P <0.0001). In the selected model in step B, again basin age and size predicted avocet abundance (Figure 5b). Larger and younger basins had more avocets (Table 1 and Figure 6a and b). Habitat characteristics also had significant effects on avocet numbers (Figure 5b): the presence of water–mud mosaic had a positive effect (Figure 6c), while numbers were highest at intermediate bare or sparsely vegetated soils (Figure 6d). Design still had a significant effect; however, the remaining difference in numbers between basin designs was small (Figure 6e).

Figure 6. Factors significantly predicting differential use of the archipelago basins by Pied Avocets. Shown are the predicted avocet abundances in relation to (a) basin size, (b) basin age, i.e. succession, and two habitat characteristics (c) proportion mosaic–mud, (d) proportion bare soil, and (e) basin design. Habitat characteristics were measured on on-the-ground observation with standardised fixed-location photography (up to three points per basin). Model estimates are based on monthly basin assessments made in May–July 2020–2023. For results of the statistical model see Table 1.

In summary: (1) basin age and basin design were the main predictors of avocet numbers, with age having the strongest negative effect; (2) basin age correlated with increases in vegetation cover and raptor presence which had no significant effect, signifying that age captured these aspects of natural succession; (3) closed basins had more avocets than open basins, however not after accounting for habitat characteristics (the availability of water–mud mosaic and bare or sparsely vegetated surfaces); (4) basin size had a significant positive effect in both models.

Discussion

Our study showed that the initially high numbers of Pied Avocets foraging on Marker Wadden in 2018 declined sharply over the years. The mudflats and shallows that avocets typically use for feeding (Enners et al. Reference Enners, Chagas, Ismar-Rebitz, Schwemmer and Garthe2019; Moreira Reference Moreira1995; Quammen Reference Quammen1982) became increasingly overgrown with vegetation. Additionally, the elevated water levels in the open basins shrunk the mudflats and shallows (affecting >70% of the surface). Numbers remained highest in the basins that remained closed and were still shallow (representing just 30% of the surface). By 2023, confined between higher vegetation and deeper water, avocets found much less feeding habitat than in 2018. In conclusion, feeding opportunities for large numbers of avocets in the newly created freshwater basins were relatively short-lived. The long construction in phases extended the period with suitable habitats, as did providing closed basins.

Unmanaged natural succession

Foraging avocets and other wader species commonly use specifically created habitats in existing brackish or freshwater wetlands (Rehfisch Reference Rehfisch1994), or artificial wetlands that are created or managed as foraging habitat for waders (Li et al. Reference Li, Chen, Lloyd, Zhu, Shan and Zhang2013; Skagen and Knopf Reference Skagen and Knopf1994). However, the loss of foraging habitats due to natural succession is not documented for avocets, and to our knowledge this is the first study documenting unmanaged natural succession in an artificial freshwater wetland and the effects on foraging waders (but see, for example, coastal restoration projects; Gamblin et al. Reference Gamblin, Darrah, Woodrey and Iglay2023). Studies mentioning managing natural succession in foraging habitats of waders mainly focus on invasive plants (e.g. on mudflats; Li et al. Reference Li, Liao, Zhang, Chen, Wang and Chen2009), preventing shrub growth with, for example, grazing and water management (e.g. in grasslands; Voslamber and Vulink Reference Voslamber and Vulink2010), or managing water levels to provide birds with well-timed high abundances of food (in rice fields; Elphick Reference Elphick1996; Elphick and Oring Reference Elphick and Oring1998). Managing natural succession by building new pristine habitats while older habitats are subsiding or eroding is not yet common, and this cyclical concept could be considered in wetland conservation for pioneer species.

Breaching the levees

In most basins after the levees were breached, water levels were soon as high as those in the lakes, so making it possible for fish to enter the basins. We do not have data on the extent of shallows in the basins that did not exceed the tarsus+tibia length of avocets, but large parts of the basins became too deep for avocets and other waders as indicated by the declining numbers. However, we found that habitat characteristics such as mosaics of bare mudflats and shallow water were important variables, so breached basins can still be potential feeding habitat, if they provide sparsely vegetated shallows. Irrespective of this, our results emphasise the waders’ need for mudflats and shallows (<20 cm deep) at a large scale in freshwater wetlands (e.g. Colwell and Taft Reference Colwell and Taft2000). The concept of closed basins can be used as a design model for future projects.

Water levels and prey base

Shallow waters, difficult to access for predatory fish, can also have different invertebrate communities (Baschuk et al. Reference Baschuk, Koper, Wrubleski and Goldsborough2012; Bouma Reference Bouma2025). Marker Wadden has a relatively simple food base, with high abundances of chironomid larvae, supplemented by scuds (Gammaridae), water boatmen (Corixidae), and opossum shrimps (Mysida) (Verkuil et al. Reference Verkuil, Dreef, van Leeuwen, van der Winden and Bakker2024). As predatory fish are less dominant in closed basins, the prey abundance and/or diversity may be different. Indeed Verkuil et al. (Reference Verkuil, Dreef, van Leeuwen, van der Winden and Bakker2024) found differences in the invertebrate community between closed and open basins. In managed wetlands with invertebrate abundances dominated by chironomids, food resources can be optimised through carefully planned flooding and drawdowns (Dechant et al. Reference Dechant, Zimmerman, Johnson, Goldade, Jamison and Euliss2002; Taft et al. Reference Taft, Colwell, Isola and Safran2002). On Marker Wadden the feeding opportunities for avocets and other waterbirds are not managed and are yet to be studied in more detail.

Lessons learned from Marker Wadden

A novel artificial archipelago such as Marker Wadden can provide inland feeding habitat for avocets and other waders. With an on-going loss of natural habitats, the importance of protected or managed natural habitats, but also artificial habitats, is paramount (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Cai, Li and Chen2010). The longevity of new (early stage) habitats depends on design (which can be controlled), natural processes (which are less easy to control), and water management. Our results suggest that freshwater habitats for avocets are best designed with closed basins with substantial amounts of shallows, allowing waders to forage while the access for fish is limited. However, Marker Wadden as such cannot be used as a model for marine environments with tidal and salt stresses, nor for all climatic regions. In other situations, for example in drier climates, open basins that are regularly flooded may be beneficial assuming water levels are adjusted for waders (Elphick Reference Elphick1996).

Conclusions

We conclude that the muddy bare or sparsely vegetated habitats, abundantly present in the initial stages of the development of Marker Wadden, were essential for avocets. The ageing archipelago became less attractive for avocets due to vegetation succession, and an intentional increase in water levels in most of the basins. However, our study also showed that the remaining mudflats and shallows continued to attract avocets. In combination with existing knowledge on the relationship between habitat use and foraging behaviour (Dreef et al. Reference Dreef, Bom and van der Winden2020), this could guide future developments of the archipelago.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270925100324.

Acknowledgements

We thank the volunteers and students for their support with counts and fixed-location photography, and especially Maarten Hotting and René Vos for their help with monitoring the avocets. The Society for Preservation of Nature Monuments in the Netherlands (Natuurmonumenten) supported with logistics such as boats and lodging. Funding was provided by the Department of Waterways and Public Works (Rijkswaterstaat), Deltares, Province Flevoland, and Natuurmonumenten. We want to especially thank Roel Posthoorn, André Rijsdorp, Quirin Smeele, Sander Postmus, Daan Vreugdenhil, Tim Kreetz, Ruurd Noordhuis, and Ruben Kluit for support during all stages of the project. We thank the Marker Wadden volunteers for their help with housing, and other logistics. Especially we thank the ferry captains for dropping us off at Marker Wadden, even in difficult situations. Jesse Conklin commented on earlier versions of the manuscript.