Introduction

I see the results once I do the practice. I feel the results…. There’s my hope. Whatever else is happening in the world, I can find some peace. I can find some centeredness. I can feel strong again. You know, everything is okay. Even if it isn’t okay, it’s still okay. Participant (Female, 70, FG4)

The increasing longevity and the growing population of older adults necessitate new models of healthy aging that reflect the diverse experiences and potential richness of longer lives. At the same time, and thanks in part to critical gerontology, there is an increasing epistemological openness to learning from non-Western traditions, Indigenous knowledges, and the arts (Chivers et al., Reference Chivers, Katz and Kriebernegg2023). One place we see this openness is in the growing interest in Eastern-influenced perspectives, such as mindfulness and yoga. These traditions are providing knowledge, values, and practices to reimagine both growing older and, more generally, living with vulnerability, loss, change, and uncertainty (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee, Balestrini, Hoydis, Kainradl and Kriebernegg2023). These may be referred to as contemplative traditions, wisdom traditions, or, as is becoming common within the medical field, mind–body medicine (MBM). Such terms encompass a diverse range of traditions and are not all Eastern in origin (for an introduction to contemplative studies for instance see Komjathy, Reference Komjathy2018).

In this article, we are interested in the potential of MBM to provide value-based skills that can support individuals through life transitions and contribute to a holistic approach to aging.Footnote 1 We draw on insights from the qualitative component of a larger study involving participants who completed an 8-week course where they began to learn how to integrate mind–body techniques in their lives. Participants reported that their training engendered a shift in attitude with more kindness, openness, and curiosity experienced towards themselves and others. From a gerontological perspective, we suggest that this shift in values is helpful in supporting individuals through life transitions – a crucial aspect of healthy aging. What’s more, by developing skills for self-awareness and self-regulation as they reported, the program offered valuable tools for embracing change and vulnerability as fundamental components of aging. We therefore suggest that MBM can offer a form of “contemplative training” that helps reimagine healthy aging, which has for the most part focused on the maintenance of activity and/or the avoidance of debility. In the case of MBM training, we find individuals learn to reframe vulnerability as a normal part of life, while developing the skills to be with suffering, in some cases even using it as an opening to a deeper connection with life.

In what follows, we situate this study within discourses of successful aging that have for the most part defined the dominant approach to healthy aging. We also briefly describe research on MBM and suggest the value of a life course perspective, which is helpful in both understanding the development of MBM over time and understanding aging as a process that benefits from preparation and training.

Background and theoretical framing

The aging population calls for a reimagining of health models that recognise the varied experiences and untapped potential of aging lives. Healthy aging has been profoundly shaped by the paradigm of “successful aging”, which emphasizes the avoidance of disease and disability, while maintaining high physical and cognitive function as well as an active engagement in life (Katz & Calasanti, Reference Katz and Calasanti2015). Emerging in the late 1980s, successful aging dovetailed with the rise of neoliberal ideologies, with both emphasizing individualism and self-reliance, while aligning with emerging therapeutic and fitness cultures that encouraged personal health practices such as improving nutrition and engaging in physical exercise (Bülow & Söderqvist, Reference Bülow and Söderqvist2014). Taken together, the successful aging framework contributed to a vast cultural shift, certainly within North America, that was optimistic about the capacity for individuals to marshal scientific knowledge and individual responsibility in the management of their own aging (Cozza et al., Reference Cozza, Ellison and Katz2022).

One example of this cultural shift can be seen in the growth of the physical fitness industry and more recently the growth of wearable fitness technologies. Those Canadians who are old enough may remember the 1973 ParticipACTION advertising campaign that made the claim that 60-year-old Swedes were fitter than 30-year-old Canadians. The campaign caused alarm, triggering a furor in parliament and a national debate on physical fitness. By today’s standards, the surprise is quaint. Training for physical health has become a well-established strategy for healthy aging. Gyms are commonplace in most urban centres, and the past decade has seen an exponential growth of wearable fitness technologies that offer individuals tools to facilitate self-monitoring and one hopes more successful aging (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Choiniere, MacDonald, Daly and Braedley2025).

But successful aging is not without its detractors. Not only is the individualism inherent in this approach criticized, but scholars such as Lamb (Reference Lamb2017) have observed that successful aging is ageist. The model focuses on maintaining youthfulness and reinforces a fear of growing old and a fear of loss, vulnerability, and dependency more generally. While the preventative motivations of successful aging are both laudable and influential, this framework is limiting to the degree that it pathologizes vulnerability and the changes that come with aging, including physical decline and dependency, which are – given enough time – typically inevitable. This is where MBM and contemplative approaches to aging (e.g., Sherman, Reference Sherman2010) may be helpful.

Mind–body approaches and aging

There is a growing literature exploring the effects of mind–body interventions for older adults, emphasizing their role in enhancing physical, mental, spiritual, and emotional wellbeing (Bhattacharyya et al., Reference Bhattacharyya, Andel and Small2021; Bui et al., Reference Bui, Chad-Friedman, Wieman, Grasfield, Rolfe, Dong, Park and Denninger2018; Farhang et al., Reference Farhang, Miranda-Castillo, Rubio and Furtado2019; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Yoon, Lee, Yoon and Chang2012; Morone & Greco, Reference Morone and Greco2007; Rejeski, Reference Rejeski2008; Vasudev et al., Reference Vasudev, Torres-Platas, Kerfoot, Potes, Therriault, Gifuni, Segal, Looper, Nair, Lavretsky and Rej2019; Wayne et al., Reference Wayne, Yeh and Mehta2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Shen, Lee, Chen and Tung2023). For instance, yoga-related programs in particular, combined with physical and psychological interventions, have been shown to enhance resilience (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Shen, Lee, Chen and Tung2023). Yoga has also been shown to improve the ability to rise from a chair and reduce fears of falling (Keay et al., Reference Keay, Praveen, Salam, Rajasekhar, Tiedemann, Thomas, Jagnoor, Sherrington and Ivers2018). Relatedly, meditation-based therapies have been associated with reductions in depression and anxiety (Vasudev et al., Reference Vasudev, Torres-Platas, Kerfoot, Potes, Therriault, Gifuni, Segal, Looper, Nair, Lavretsky and Rej2019). And the integration of mind–body approaches also offers significant benefits for the management of suffering related to chronic illnesses, cancer-related symptoms, insomnia, and grief (Bui et al., Reference Bui, Chad-Friedman, Wieman, Grasfield, Rolfe, Dong, Park and Denninger2018; Morone & Greco, Reference Morone and Greco2007).

Much of the existing health literature on MBM frames mindfulness within medical and clinical contexts, positioning it primarily as an intervention aimed at conventional physical or mental health outcomes. What’s more, foundational research on the stress response (Selye, Reference Selye1955) continues to influence medical thinking about spirituality. This research revolutionized medicine by establishing a physiological basis for psychological stress, legitimizing mind–body approaches within Western medical frameworks. As an example, over the past decade, there has been considerable effort made to establish the neurological correlates of meditation and spirituality, leading to what some have termed “neurotheology” (Klemm, Reference Klemm2022). However, although these approaches may have originally legitimated research on spirituality with medicine, they risk narrowing the terms by which they matter for healthy aging.

The techniques made available through yoga, Buddhist inspired mindfulness, and others have deep roots in wisdom traditions that are increasingly being explored in fields, such as contemplative studies, religious studies, and cultural studies (Komjathy, Reference Komjathy2018; O’Brien-Kop & Newcombe, Reference O’Brien-Kop, Newcombe, Newcombe and O’Brien-Kop2021). Scholars in these areas emphasize the philosophical, spiritual, and existential dimensions of mindfulness and yoga, which extend far beyond their role in stress management or disease prevention (McMahan, Reference McMahan2023). These explorations highlight their potential to foster meaning, connection, and a more integrated sense of self – insights that are particularly relevant to adults navigating the complexities of life and growing older.

A life course approach to mind–body medicine

Life course perspective provides a useful framework for situating mind–body approaches within the lifespan. Unlike theoretical lenses that view aging as only a later-life phenomenon, the life course perspective frames it as a lifelong process, capturing the temporal, contextual, and processual components of human development throughout the entirety of life (Elder, Reference Elder1994). This perspective also recognizes the cumulative advantages and/or disadvantages that are accrued and how experiences are carried forth, influencing later life (Dannefer, Reference Dannefer2003).

With a life course perspective in mind, we approach mind–body training as a means of developing values and skills throughout the life course, which may prepare individuals to manage challenges and transitions, such as career shifts, relationship changes, accidents, and/or illnesses, more effectively. In Pathways to Stillness, Canadian gerontologist Gary Irwin-Kenyon (Reference Irwin-Kenyon2016) provides numerous examples of how contemplative practices have supported aging, helping him and others find meaning and connection through challenging situations, such as a midlife divorce, chronic illness, and grief. Similarly, in a study of older adults’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, Achephol and colleagues (Achepohl et al., Reference Achepohl, Heaney, Rosas, Moore, Rich and Winter2022) found that most participants categorized as having high resilience reported engaging in some form of contemplative practice, which enabled them to adapt to the rapidly changing social landscape. This finding leads them to call for a rethinking of healthy aging to incorporate the integration of “contemplative practices” into the lives of older adults. “As we continue to face global challenges”, they propose that:

we must redefine care, guide interventions, and promote healthy aging by incorporating contemplative practices into the lives of older adults. On a community level, non-profit organizations should be intentional about cultivating contemplative practices. On a provider level, physicians should consider asking older adults about their contemplative practices and encouraging them to continue developing their resilience.

(Achepohl et al., Reference Achepohl, Heaney, Rosas, Moore, Rich and Winter2022, p. 10)Current research appears to support their calls for the integration of contemplative practices into both an understanding of healthy aging and public health provision. However, the authors’ focus on older adults reflects the absence of a life course perspective. Their participants reported benefiting from well-established contemplative practices, in some cases with over a decade of training. For people who are already old, it is certainly better to start late than never. But when one is making systems level recommendations, it might make more sense to recommend cultivating contemplative practices earlier so that they are established when one needs them – a form of contemplative training for growing older.

The mind–body medicine program

Those living in Fredericton, New Brunswick have unique access to the type of not-for-profit organization that Achephol et al. (Reference Achepohl, Heaney, Rosas, Moore, Rich and Winter2022) are calling for, offering MBM training to adults – both young and old – as part of publicly funded medical care. For over a decade, the Iris Centre for Mindfulness, Peace and Healing has been hosting a range of MBM courses, notably an 8-week course designed for beginners, titled “Mindfulness and Conscious Living: A Body–Mind Awareness Training” (MCL: BMAT). The course is led by a biomedically trained physician who is also a long-time contemplative practitioner. Participants come to the course either as a result of a clinical referral from another physician or a self-referral, with most presenting concerns related to life stress, mood, anxiety, or pain disorders. A smaller sub-set engaged with the program primarily for general wellness.

The course incorporates a range of mind–body techniques, including mindfulness, relaxation response, breathwork, cognitive-behavioural therapy, and kindness-compassion practice. These techniques draw from established mindfulness-based interventions, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (Hanh & Kabat-Zinn, Reference Hanh and Kabat-Zinn2013; Santorelli & Kabat-Zinn, Reference Santorelli and Kabat-Zinn2010), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (Segal et al., Reference Segal, Williams, Teasdale and Kabat-Zinn2018; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Teasdale, Segal and Kabat-Zinn2024), and mindfulness-based relapse prevention (Bowen et al., Reference Bowen, Chawla, Grow and Marlatt2021). Notably, the MCL-BMAT program situates MBM within contemplative values of openness, presence, curiosity, kindness, and compassion. It consists of one 3-hour orientation session followed by eight 3-hour classes. The program also includes a mid-program consultation with the instructor and a full-day silent retreat to deepen the experience. Each class introduces a set of skills and values, with time for practice, deep reflection, journaling, and group inquiry. Themes progress from understanding perception and reactivity to cultivating compassion and intentional living, further details of the MCL-BMAT sessions can be found in the Supplementary Material. The experiential and group elements allow participants to examine and share their experience with others. For instance, in the first of the 8-week classes, participants are taught to perform a basic body scan, which is a Buddhist inspired mindfulness meditation technique. Over approximately 60 minutes, participants are guided in bringing their attention to each part of their body, systematically moving from toe to head, noticing sensations without judgment. Then they are given time to reflect, journal and share their experience. The group sharing enables the instructors to offer further guidance, for instance, pointing out how judgments, particularly negative ones, creep into seemingly neutral descriptions. Subsequent classes build on this learning, in a step wise fashion, loosely guided by Buddhist psychologist Tara Brach’s RAIN approach, which asks people to Recognize what is happening, Allow the experience to be there as it is, Inquire with kindness, and Nurture with compassion. Each class also presents a brief overview of the current scientific understanding of how these techniques work.

Methods

The MCL-BMAT course offered us an opportunity to learn about the lived experience of contemplative training. We were particularly interested in understanding how participants made sense of the contemplative approach, what favourable effects they encountered in learning these skills, what struggles they faced with understanding or implementing them, and the difference the program made in their lives outside the course. Given our gerontological interest in healthy aging, we were particularly curious about whether and how the program might support more holistic approaches to aging and mortality.

To answer these questions, we conducted a mixed-methods study. Ethics approval for the study was received from both St. Thomas University’s (REB202121) and Horizon Health’s research ethics boards (RS20213064). In the first phase, we analysed 897 course completion questionnaires that gathered both quantitative and qualitative data on participants’ experience with the course content and delivery. Following the analysis of this data, we conducted focus groups with 20 participants to better understand the process of learning and practicing the material. To explore barriers to completion, we also interviewed four individuals who did not finish the course. Individual interviews were conducted rather than focus groups to provide these participants with greater anonymity and facilitate openness. Interestingly, although each interviewee attended several sessions before discontinuing, only one attributed their decision to quit to the course content itself, noting that it did not “click” for him. The remaining three interviewees valued the material but found the course design and delivery challenging. One participant reported that the three-hour sessions were too long and the plastic chairs too hard, given their chronic pain. Another participant described the sessions as overly long, quiet and slow, preferring more active forms of mindfulness practice (e.g., mindful walking). Finally, one interviewee explained that, due to past trauma, they were not yet ready to engage in a group setting but otherwise would have wanted to complete the course. An initial report drawing on the survey, group and individual interviews found a wide range of benefits from participating in the program was produced for the centre.

Our analysis in this article explores the learning process and draws specifically on the qualitative data, including focus group and interviews, as it provides a rich understanding of participants’ experiences with the material. The focus groups included 20 participants who completed at least six of the eight sessions, and their data are labeled with an “FG” in the results section. Participants in the focus groups were not drawn from the same course cohort, nor did they know each other, except for two individuals. Individual interviews were conducted with four people who did not complete the program and are referred to as “II”. Data collection analysed here included all six focus group sessions and four semi-structured interviews.

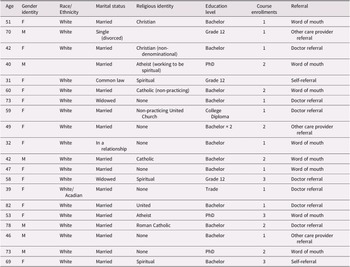

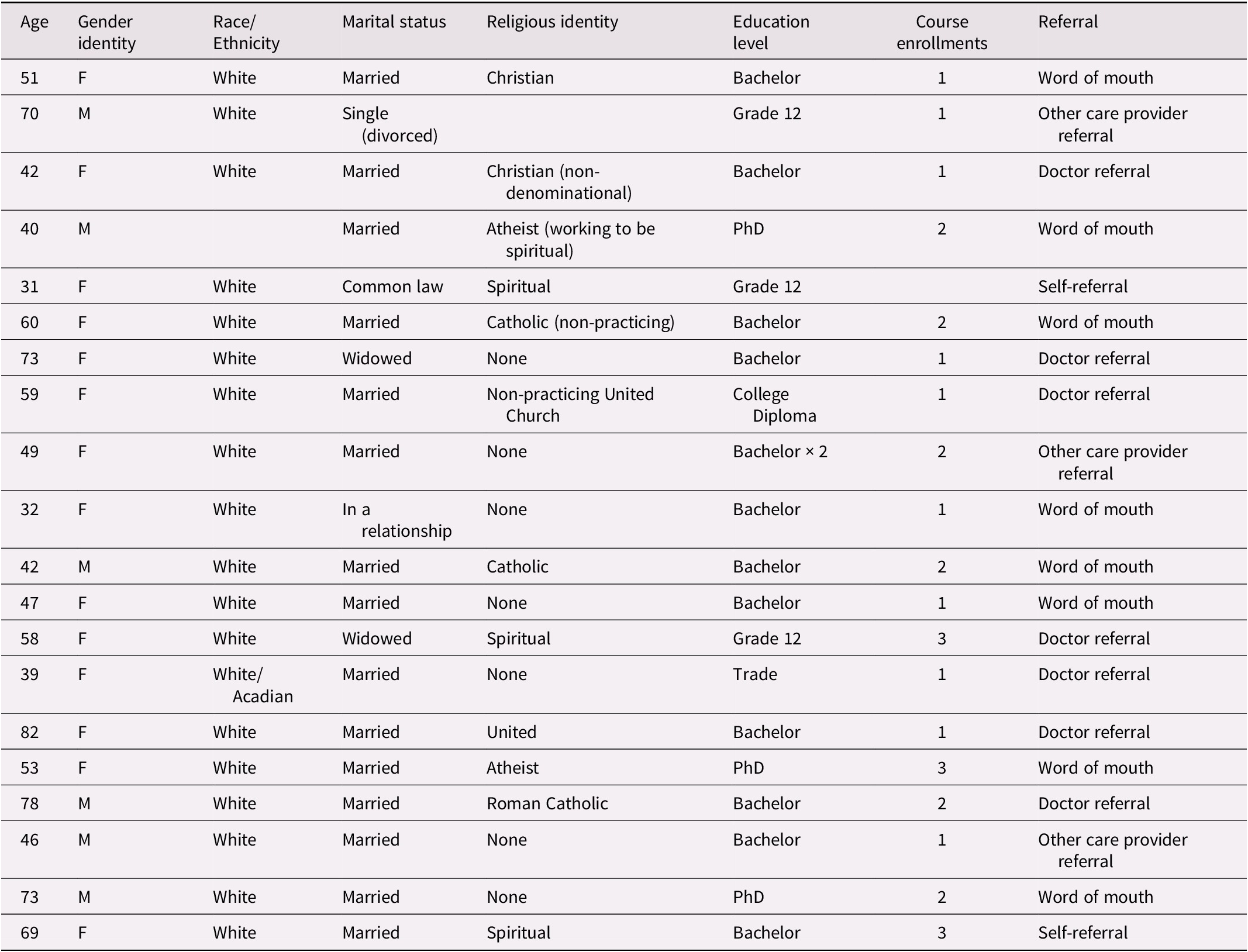

Participants were recruited through email invitations by the second author. Emails were sent to individuals who were registered for the 8-week course, including those who did not complete it. Sample characteristics of the focus group participants can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics of focus group participants

All focus groups and interviews were semi-structured – loosely following a guide – to support the in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences, while providing the flexibility to pursue new themes. Focus group prompts and interview questions explored participants’ experiences with resilience, personal transformation, and mindfulness practice. Sample questions included “What the most important thing you learned from this course?”, “How has the course affected your relationship yourself?”, “Has this practice helped you deal with the challenges of life?”, and “What aspects of the material were easy or difficult to apply?”

The focus groups and interviews were transcribed and imported into NVivo 15, a qualitative data analysis software, to facilitate the organization and coding of data. An open coding approach was initially employed to identify significant concepts and themes directly from the data. This process involved detailed line-by-line analysis, during which codes were assigned to segments of text that captured key aspects of participants’ experiences. Following the open coding, axial coding was used to further refine and categorize the initial codes into broader themes and subthemes. This stage involved examining the relationships between codes, identifying patterns, and linking categories to form a coherent thematic structure (Williams & Moser, Reference Williams and Moser2019).

The goal of this analysis was to produce a nuanced understanding of participants’ experiences of MBM training, including its benefits and challenges. Emerging themes were reviewed and refined through discussions among the research team. The qualitative findings were synthesized into several themes with key quotations that encapsulated the essence of the participants’ experience with the MCL-BMAT program. Following this analysis, the audio recordings were listened to again to identify negative cases and ensure accurate representation. In sum, these accounts provided rich, contextualized insights into how the program influenced participants’ relationships with themselves, others, and their understandings of health and aging.

Results

The analysis presented below aims to understand some of the important aspects of contemplative training as described by participants dealing with a variety of challenges, many of them relevant to aging (e.g., chronic illness, bereavement, loss, trauma). We present three notable analytic themes: The first was “learning to notice and be with experience”, the second was “accepting change and vulnerability as normal parts of life”, and the third was “the ongoing development of a contemplative toolkit”. Interwoven throughout these themes are the values of compassion and curiosity that pushed back against dominant narratives of fear and control. They also supported participants in approaching life with greater openness. While these themes build on each other, they also occur concurrently, reflecting the complex and dynamic nature of contemplative training.

Learning to notice and be with experience

One of the foundational skills that participants reported developing through the 8-week course was the capacity to slow down, notice and be with what was happening for them. For instance, one participant, talkative by nature, discovered the power of silence. “When my anxiety kicks in I over intellectualize. I overanalyze. I get really chatty. […] I’ve learned to just embrace the silence. You don’t have to speak. Just really listen” (FG3).

The course provided many opportunities to practice present moment awareness, which participants could develop further outside the course. This ability to notice was foundational in becoming more conscious about what they were thinking and feeling, enabling them to begin to respond to experience with greater wisdom. A military veteran (FG2) who was suffering from chronic pain, described that he could no longer “go-go-go” as he used to because of his “limitations”. His developing capacity to be present enabled better responsiveness:

I found with myself having the military experience and training stuff, I plan for the future. I see when things start getting off the rails. I can anticipate them and adjust to overcome. Whereas with the newfound limitations I was dealing with, it’s harder for me to be able to realize when things are starting to get off the track. Then all of a sudden it becomes super-overwhelming! How to cope with these things and adjust and overcome without making it a disaster for everybody. I found it easier to stay calm and collected and to be able to make an educated thought-through correction versus just a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants and whatever you’re feeling in that in the moment type thing. (FG2)

It was very common to hear, as in the above quote, that participants were developing the ability to notice and reflect on their experience and respond in novel and more helpful ways. Another participant, a nurse by profession, explained that the program helped her prioritize her anxieties more effectively, likening the process to a “triage” (FG2). This shift in perspective did not deny problems but allowed her to better evaluate the importance of her concerns and recognize that many worries may never materialize. Others reported implementing a lesson on negativity bias, to assess whether their thoughts/feeling were realistic or helpful. As one participant explains:

[the instructor] talks a lot about our negativity bias and how we’re so trained to look at the negative in life and always see things as a threat. Always seeing things as like “poor me.” I’m not always able to get out of that framework, but I’m able to look at it and be like: you’re in a negative framework. This is what your brain is thinking. (FG1)

We heard a growing capacity to work with their thoughts and emotions. This included training oneself to become more compassionate. “Having the practice of being good to myself and other people”, remarked one participant (FG4), “If I remind myself of that, it is really helpful”. In all cases, what we were hearing in the focus groups was that through their training, participants were experiencing a growing space between their thoughts/feeling and reality. “I am not my thoughts”, as one father put it succinctly (FG5). Or as we can read in the quote above, this is not what “I” am thinking, “[t]his is what your brain is thinking”. Another participant (FG1) noted:

One of the things – I have it up on my bathroom mirror – is thoughts aren’t facts. Looking at how we have all this sensory input, and we think of sound, and touch, and all those things as outside stimuli, but recognizing our thoughts are too. They’re not reality. Being able to look at what your thoughts are experiencing, that narrative brain that we have isn’t necessarily truth, and trying to just come to a deeper place…

Central to these discussions was also the value of accepting emotional experiences without striving to change them. Many recounted lessons on neutrally labeling emotions and accepting them: “just being… not trying to get to a different state… just be where you are” (FG1). This acceptance-oriented approach was contrasted with the value of control. For example, one participant reflected on how the program helped her accept her husbands’ dying and be with him without trying to “control every single, solitary thing”. As she explains:

It was just helping me accept. You have to go through stages of grief and things. But when I really realized at the end that my husband was ready to pass, I was able to accept that and to try to do as much as he wanted, with his wishes. I really think a lot of it was not trying to control everything and just living for the day. (FG2)

It should be noted that acceptance did not preclude agency. In the above, as with many other participants, acceptance enabled more appropriate or beneficial responses. One could be with, accept, and then decide what to do: such as evaluate the thought, put another kinder thought in its place, or set a boundary. One participant (FG5) who was dealing with an “unsafe work environment’” noted how the instructor encouraged him to both “accept and advocate’” The combination was empowering. “The information I got [from the instructor] was much more beneficial because he was speaking of advocacy and acceptance, whereas the telehealth [support person] was suggesting, why don’t you put a picture of an ocean on your cubical! No. Nope. No. That’s not going to help”. He and several other participants facing difficult work environments reported finding new jobs.

The sense of gratitude that participants expressed because of these newly cultivated skills and attitudes was palpable in the focus groups. One participant cried tears of gratitude (FG1). Many declared the program “life changing” (FG4). Another noted it was a pivotal moment in their life’s course: “It helped me to slow down and discover who I am…it was a catalyst to my healing journey” (FG3).

Accepting change and vulnerability as normal parts of life

Participants remarked on how the course gave them a variety of tools to help them face difficult transitions and life events, such as anxiety, chronic illnesses, death, grief, loss, childhood trauma, accidents, family challenges, and other major life crises. Many practices were referenced, including meditation, yogic poses, yogic breathing, reflection, journalling, mindfulness, mindful eating, mindful walking, reminders, aphorisms, poetry, readings, and prayer, just to name a few. These tools were used in various ways to work with difficult situations. For instance, one participant recounted the experience of receiving distressing news about their son getting a DUI:

To actually have the tools and the actual things that I can do. Like the night when I got the news about my son. You know, I’d wake up. Go to the bathroom. And right away, I’m like: “Oh my god! Oh my God!” But I’m able to stop myself and [use] the body scan […] I was actually able to mostly sleep through the night because I’m able to follow the steps that we learned. (FG2)

Participants offered many examples such as the above, where they drew on their training to work with difficult life events. The course was described by some participants as developing their ability to cope with struggle. It offers “a coping mechanism for when those stressors come up’” (FG2) as one participant put it. This clearly is important, and as we hear in the above quote, being well rested when facing life’s challenges is no small accomplishment. However, others noted and appreciated the existential and spiritual elements of the course. “For me, it was an introduction to this type of stuff and spirituality, which kind of developed my interest in it. …It’s been a lot of kind of dabbling with different things and, you know, trying to figure out what your life purpose is and what the universe is and how it’s interacting with you and stuff…’”(FG3).

A key element of this broader, existential or spiritual approach to life was the normalization of vulnerability and suffering. “[The course] does help you reach calmness. But it also makes you feel more, you know, accepted. We’re human, this is normal. This is life. We get through it, and that kind of thing” (FG2). The course represented adversity as normal. Death was not an exception. Illness was not an exception. Failure was not an exception. These ordeals were positioned as shared. Reflecting on the challenges people were dealing with, one participant (FG5) remarked that you could “sort figure out why they [the participants] were there”, even though the reason might be “a bit ambiguous and not specific”, the instructor made it feel like it was “communal’”. Even the instructor shared some of the hardships he had lived through, thus, adopting a stance, as one participant (FG4) described of: “I’m not above you and not below you. I am with you”.

The group sharing played a crucial role in normalizing vulnerability. As one participant described:

you know that you’re not the only one that’s suffering…. just knowing we’re all there because we need help just makes me feel I’m not alone and there is hope. I see, in others, over the weeks, how they bloom. And I feel that for me too. You go in there initially and you feel so out of place. Really, if they only knew what I was about! Then within two or three weeks, you realize that it’s home. You don’t have to know anybody’s name or, you know, you don’t have to talk to them during the break or anything. It’s just when you’re there, it’s like you’re there together. (FG4)

On the one hand it is remarkable that in the midst of suffering one can feel at home. As one participant (FG6) noted, the course builds a sense of “solidarity” through shared suffering. On the other hand, it does this by delving into difficult topics, which has its challenges. As another participant remarked. “That’s what I mean by mindfulness is a tough sell. You have to welcome stuff that you try to avoid all your life, and all of a sudden you’re welcoming it into your world” (FG2). Another found himself sharing like he never had, becoming more open and honest with himself and others:

Here I am. I’m sixty-three and I’m just starting to discuss some of the things I should have discussed a long time ago. That being said, I grew up in a very closed emotional environment. Men don’t cry. Men don’t express emotions. Here I am sixty years of age, starting to express some of my deepest darkest secrets. It’s getting easier. It’s still not easy, but I know I have to speak my truth and be honest with myself. Not only for me but for my family too. I’m better at it. I’m working at it. I’ve experienced benefits firsthand, when I’m open and honest with myself and with others. (FG5)

Many participants reported that this openness and acceptance of suffering gave them power over their experience, and could even help them reframe it as something positive:

What I found was that the program brought me into a place of calm and a place of acceptance. A place of being the victor, not victim. You know, the mindset was instead of being a victim of circumstance, I was the victor of this. It was also the gratefulness. It was huge. Shifting that experience – as horrible as it was – the gratitude of that experience and how that experience has changed my life as well. (FG1)

Participants’ accounts of how they have come to make sense of various life events and transitions highlighted the transformative power of vulnerability. Embracing vulnerability was pivotal in helping participants navigate suffering and change. A common thread running through these accounts was a shift from self-criticism to self-compassion. Participants described how they have become kinder to themselves, less governed by an inner critic demanding perfection. They were learning to forgive themselves for mistakes and to approach life with a greater sense of openness, curiosity, and acceptance. Self-compassion emerged as a crucial strategy to manage change, with participants recognizing the importance of being kind to themselves. Others found the course stimulating interest in spiritual inquiry or helping them understand what some of the work behind spiritual clichés might involve. As one man suffering with chronic pain noted, “I understand the phrase, live for today. I’m getting better at living for today” (FG5).

The ongoing development of a contemplative toolkit

In listening to the wide range of benefits participants reported from their training – e.g., increased capacity to manage pain, greater ability to be present with family, less anxiety and greater calm – it became apparent that a common thread was the development of a set of tools that participants could use across a variety of situations. Reflecting on the ordeal of COVID-19, one participant observed that while she initially had a difficult time, she was able to draw on her training: “Thank God I had the tools and that eventually I was able to get myself back in there and pull them out of the toolbox and be able to help myself and to help other people as well” (FG1). Having these tools at one’s disposal was empowering, as she went on to add: “[The instructor] putting the power in the tools and the knowledge in your hands. It’s an invitation. It’s an invitation for you to try this. It’s just so empowering, and you don’t get that in the health care system”. This sentiment was echoed by many others. One participant acknowledged that while struggle and pain would not disappear from his life, he now had “little tricks” to help him regain balance in difficult moments (FG5).

However, developing these tools was not quick nor necessarily easy. The practice, as participants consistently highlighted, required dedication and effort. There were obstacles participants needed to confront, such as the cultural skepticism around these sorts of practices or a lack of understanding from family or work colleagues. Indeed, their own skepticism was noted as an initial barrier. Some delayed registering in the course until they were “desperate”. But by far the most common challenge was setting aside time for practicing new skills. Participants described the difficulty of finding time and space for meditation, especially when others might not share the same commitment. They noted that the tools took time to implement reliably. As one participant put it:

Just knowing you can calm yourself down that you have the innate resources instead of having to smoke a joint, you have these innate resources to calm yourself down, which we said is a practice. It took me a good two, two and a half years of doing it every day until I could go to bed at night and breathe and feel like this was a massage for my soul or something. It didn’t happen overnight. (FG1)

Two and a half years is a long time. Of course, not all skills took this long, some came quicker, and some people reported immediate benefits. Moreover, if we pay attention to the start of her statement, we can hear that “just knowing” that you have these tools, that you have a “practice” is empowering. Indeed, for many participants the notion of a practice gave them a sense of agency – that one could develop the skills with time. As one participant remarked, “I also think the thought that I have a tool to go to and that it’s not just one tool, it’s a whole bunch of things. I still feel like I have so much more to learn, but I know that it’s there for me to tap into” (FG2).

As we see above and in the last theme, the course presented struggle and failure as part of life. Acceptance of failure also applied the practice itself. One participant recounted a difficult day when he let his anger hold sway. He shared this with the instructor and reflected on the supportive response: “He understood that my anger was probably deep-rooted… He just understands that you can have a bad day. And it gives you the idea you can practice. You can recover” (FG5). The notion of MBM as a “practice” normalized imperfection, stumbling, and still growing and this was experienced as empowering. One could fail. One could get angry. And one could try again.

Indeed, some people took the course multiple times. As one participant who did so remarked: “Just the idea that it’s a lifelong practice and the reminder, each time I took the course that again, you just simply pick up where you left off and try and integrate it into one’s life” (FG6). Thus, the actual way MBM works – as skills that take time to learn and integrate – might be seen as a strategy of pushing back against a culture of quick fixes in which ease is normalized and failure somehow exceptional.

While developing these tools and the capacity to integrate them in one’s life took effort and time, participants presented the journey itself as worthwhile. Participants were learning, growing, developing capacity and wisdom through contemplative training. The instructor also served as a living example and his modeling was both educational and inspiring. Referring to the instructor, one participant noted:

It’s a stance, I think would be the word I would use. It’s intelligence. He embodies the program. Maybe that’s what I mean. You can tell by the way he stands his ease…he embodies the program, and you feel when you meet him that there’s something different. (FG4)

This “something different”, we were told, had much to do with the instructor’s openness, calm, presence, and acceptance, which participants experienced directly and commented upon: “Him telling me that I wasn’t a broken person, gave me so much fucking hope for the rest of my life” (II1). Or as another participant put it:

It was really helpful to have someone who actually could explain it so much clearer and answered questions… it’s probably the difference between trying to study, say, basketball by reading about it and having a coach to actually demonstrate for you how to actually perform the skill. (FG5)

Finally, we note that one of the recurring benefits that was flagged by participants was hope. The course gave them hope, and this was a hope that derived not from some outside source but from the skills and capacities they were developing. As one participant put it, “I see the results once I do the practice. I feel the results…. There’s my hope. Whatever else is happening in the world, I can find some peace. I can find some centeredness. I can feel strong again. You know, everything is okay. Even if it isn’t okay, it’s still okay” (FG4).

Discussion

Someone I loved once gave me a box full of darkness. It took me years to understand that this, too, was a gift

—Mary Oliver, The Uses of Sorrow

This study explored the practice and effects of MBM training from the perspectives of participants. They reported an improved capacity to confront challenging situations such as chronic pain, the death of a spouse, as well improved relationships, including with themselves. Our analysis highlighted some of the key elements of their contemplative training, such as learning to notice and be with feelings, particularly difficult ones. We found the program supported participants’ acceptance of change, struggle and vulnerability as normal parts of life. Our study thus aligns with emerging critiques of the successful aging paradigm, particularly those articulated by Martinson and Berridge (Reference Martinson and Berridge2015) that recognise the model offers a narrow, ageist, ableist, and ultimately unrealistic conceptualization of aging. In contrast, participants in our study described the development of a practical repertoire of contemplative tools in the face of vulnerability and life’s challenges. Notably, they reported a shift in their attitude towards themselves, characterized by increased openness, curiosity and self-compassion.

These findings lead us to challenge the notion of healthy aging as a static state, associated with avoiding decline. Instead, we propose a dynamic, skills and value-based approach to healthy aging. This perspective is skill-based because it recognises the importance of a range of contemplative techniques, from journaling to breathwork, to help navigate life’s struggles. It is value-based, because these are offered within a context that accepts change, vulnerability, and loss as normal parts of life. Our findings highlight the potential of cultivating contemplative practices as a foundational component of healthy aging, supporting individuals in navigating life transitions and challenges that may intensify in later years.

This echoes the work of Achepohl et al. (Reference Achepohl, Heaney, Rosas, Moore, Rich and Winter2022), who, as noted earlier, observed that older adults engaged in contemplative practices such as meditation, breath awareness, and gratitude showed higher resilience during a time of crisis. However, our findings lead us to amend their call to reimagine healthy aging to begin earlier than one’s later years. Certainly, participants in this study found that developing their skills took time, requiring deliberate intention and effort. Indeed, some participants had taken the course multiple times, with each iteration revealing new insights and deepening existing capacities. This finding contributed to our theorizing of MBM from a life course perspective, recognising that contemplative aging requires ongoing training. Rather than being a “one-and-done” experience, our research suggests that knowledge unfolded gradually, with skills broadening and deepening through repeated use, learning, and engagement. Several participants even noted that the focus groups themselves served as a welcome refresher. These insights underscore the importance of considering opportunities for maintenance and continued learning in both program delivery and future research on contemplative approaches to aging.

While the requirement for such practice might seem undesirable and even inefficient compared to a pharmaceutical intervention, the knowledge that participants could develop and refine their skills gave them a sense of agency. The idea of “a practice” was itself empowering. Indeed, several participants regretted they had not been exposed to contemplative training earlier. This raises the question of when is it appropriate to begin contemplative education? One father, for instance, recalled sharing the insight that “we are not our thoughts” with his young daughter and reported that it was helpful for her as it had been for him. Whereas another participant wondered whether he would have valued these practices as he does now, suggesting that he needed to experience some hardship for them to make sense. Again, a life course perspective may prove valuable in examining when and how contemplative education resonates and how it might be pedagogically adapted for different stages of life. Our findings, consistent with other scholarship (e.g., Rohr, Reference Rohr2011), suggest a nuanced dynamic exists between age and suffering that warrants further investigation. For instance, might a younger individual who has experienced significant adversity be more receptive to contemplative training than an older person who has encountered relatively little hardship? In other words, what roles do age and exposure to suffering play in openness to contemplative practices?

We also want to flag the value-based nature of the MBM training we studied. In addition to skills, the openness and acceptance participants were learning mattered. Kenyon’s scholarship on Tai Chi as narrative care is helpful in clarifying how contemplative values can recontextualize healthy aging. Narrative gerontology is a perspective that attends “inner aging”, as Kenyon (Reference Kenyon, Kenyon, Bohlmeijer and Randall2011) explains. It pays attention to our inner life and the meanings that we give to life events. Importantly, narrative care recognises – as our participants had learned to recognise – that there is a gap between what happens and the meanings we make. “It is this space that allows for the possibility of restorying the experience towards less suffering” (Kenyon, Reference Kenyon, Kenyon, Bohlmeijer and Randall2011, p. 242). As with the MBM course we studied, where participants were taught to understand vulnerability and loss as part of life, Kenyon suggests that contemplative training such as Tai Chi presents us with a different story that we can use to reframe the changes we may not initially desire. In such restorying, we may experience a “movement from loss and suffering to surrender and acceptance, to the creation and discovery of new meaning…” and perhaps even to something beyond ourselves he adds (p. 241). Much as participants in our study were trained to face struggle with some openness and curiosity, “[p]rogress in Tai Chi, whether we view it as a meditation or as a martial art, occurs to the degree that we are able to accept and surrender to what is happening in the present moment” (p. 245). In this way, contemplative training provides narratives that people can marshal to engage with the challenges of life. However, the narrative resources that are being provided do not reproduce the aspirations for control that underly successful aging nor are they simply narratives of decline. Similarly, participants were not being trained to seek control nor be passive. The value orientation enacted by contemplative training is more complex than such binaries allow. As Kenyon explains:

One way to describe this is to say that when something comes at you whether it is a training partner or life itself, do not abandon your intention or disarm before the inevitable. By the same token, do not rigidly or stubbornly attempt to control the situation. Instead, “follow” what is happening and be flexible…. We attempt to move with the changes and have no expectations from ourselves or from our environments. (pp. 245–246)

There are clear parallels between the Tai Chi teachings that Kenyon describes and the openness and curiosity participants in our study were practicing. As they reported, this orientation towards receptivity enabled them to face difficulties with some agency and grace, leaving them feeling empowered while paradoxically accepting life’s events – even if it was something as distressing as chronic pain or the death of a beloved spouse.

It is also critical to acknowledge the role of the instructor and the relational dynamics of healthcare in producing these benefits. The outcomes of the course were not solely a result of the curriculum or practices themselves but appear to be deeply influenced by the relational environment fostered by the instructor. Participants consistently described feeling safe, seen, and supported, which in turn allowed qualities such as openness, curiosity and self-compassion to emerge. Additionally, the instructor’s own embodied expression of the program’s principles was noted by many participants as integral to their learning. The instructor thus served as a wellbeing role model for participants (Howick et al., Reference Howick, de Zulueta and Gray2024). This raises important questions: How do we replicate such relational environments? What does this suggest about the qualities of presence and leadership required of those teaching such courses? This may have implications for program design, suggesting that healthcare providers who are less experienced with these techniques could benefit from partnerships with seasoned mindfulness and yoga instructors when delivering such programs. Not only are these considerations for future research, they invite a broader reimaging of healthy aging, not only as a dynamic, value-driven process but one that also includes the role and wellbeing of practitioners as integral to the conceptualization and delivery of care.

One of the limitations of the research design is that focus groups were not stratified by age. Group formation was based on availability via a scheduling poll, resulting in randomly assembled groups of differing ages. While stratifying groups by age could have yielded more targeted insights, we opted for intergenerational groupings as a result of scheduling considerations and to encourage cross-generational dialogue. Despite these constraints, the data revealed meaningful reflections on aging and the life course. Participants articulated the relevance of the training across various life stages, described how skill development facilitated life transitions, and conveyed how their understanding evolved through sustained engagement. Although many challenges discussed were associated with aging, they also reflected broader experiences not exclusive to later life.

As well, it is important to address critiques of MBM, particularly how Western societies have instrumentalized contemplative practices, often focusing on personal optimization in ways that align with neoliberal values of individual entrepreneurship (Purser, Reference Purser2019). There are many harms that follow from this responsibilization, including individuals who might feel at fault and ashamed for their illness and misfortunes (Lamb, Reference Lamb2017). Indeed, some participants reported starting the program feeling this way, but the value orientation and the group sharing helped them reframe their experience, fostering what one participant referred to as a sense of “solidarity” that we are not in this alone. Whether and how contemplative training might foster broader political forms of solidarity or cultural change around vulnerability and aging is an open question, and one worth asking (e.g., Rowe, Reference Rowe2024). Could the generalization of these approaches contribute to a more caring and age-friendly society? Could this assist with reimagining healthy aging, such that it is more compassionate and empowering? Maybe healthier, in other words?

Conclusion

The findings from this study demonstrate the value of transitioning towards more holistic models of healthy aging that incorporate the significance of accepting vulnerability and change as inherent aspects of life. Mind body training can complement traditional healthcare, empowering individuals to manage their health and stress more effectively. There are also broader social and cultural changes that such training, if mainstreamed, may support, addressing some of the fear of vulnerability that may well underly ageism and, in doing so, contributing to a more age-friendly environment (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee, Balestrini, Hoydis, Kainradl and Kriebernegg2023). Although our study did not explore the sociocultural or political elements of contemplative perspectives directly, they are worth further study in the context of an aging society. Nonetheless, the insights from this study offer a valuable stepping stone towards bridging mindfulness with evolving narratives of successful aging, one that embraces vulnerability not as a weakness, but as a vital thread woven throughout the life course.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980826100531.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all individuals who participated in our interviews and survey, generously sharing their time and insights. Their contributions were invaluable to this research. Special thanks to Darlene Hamilton, Office Manager of the Iris Centre for Mindfulness, Peace and Healing for her assistance with various aspects of this project.

Author contribution

Study conception and design: A.B., W.A.C.; Data collection: R.P., A.B.; Data analysis and interpretation: S.T., R.P., A.B.; Draft manuscript preparation: S.T.; Critical revisions of the manuscript: A.B., S.T.; Manuscript editing and final approval: S.T., R.P., W.A.C., A.B.

Financial support

This research was supported by funding from the NB Research Chair in Community Health and Aging and from Mitacs through the Mitacs Accelerate program.

Competing interests

W.A.C. serves as the primary facilitator of the 8-week course that was studied in this article and is the director of the non-profit Iris Centre for Meditation, Peace and Healing where the course was hosted. To mitigate potential conflicts of interest, rigorous methodological safeguards were implemented throughout the research process. W.A.C was excluded from participant recruitment (beyond providing a REB approved comprehensive participant roster), data collection procedures, and preliminary data analysis. His substantive contributions were limited to study conceptualization, interpretation of preliminary analyses, and manuscript preparation, where his subject matter expertise was essential. These measures were designed to maintain research integrity while benefiting from W.A.C.’s specialized knowledge in the field. The remaining authors declare none.