1. Introduction

Some risks are well defined and play out in a familiar and consistent way, making them more predictable. These recognisable patterns enable targeted management to reduce risk. Beyond such ‘conventional’ risks, other types of risk are less intuitive and result from non-linear cause-and-effect relationships, often manifesting themselves through complex causal pathways. Such ‘systemic’ risks arise from interactions between different interconnected systems, for example, through a process of contagion across political, economic, social, technological, legal/regulatory, or environmental systems (Centeno et al., Reference Centeno, Nag, Patterson, Shaver and Windawi2015; Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Homer-Dixon, Janzwood, Rockstöm, Renn and Donges2024).

Systemic risks present challenges in terms of understanding their importance (e.g. their probability and impact) and developing appropriate responses. Anticipatory frameworks are challenging due to the complex nature of causal pathways, leading to low confidence and/or deep uncertainty inherent in such assessments. Nevertheless, we believe appraising systemic risks is essential because these risks can have extensive impacts on the health and prosperity of our societies (Sillmann et al., Reference Sillmann, Christensen, Hochrainer-Stigler, Huang-Lachmann, Juhola, Kornhuber, Mahecha, Mechler, Reichstein and Ruane2022). In an increasingly interconnected world, systemic risks are becoming more likely, thus increasing the urgency for credible and robust frameworks to deal with them (World Economic Forum, 2024). Innovative frameworks and decision-making support tools are needed to identify strategies to reduce exposure and impact from such risks (IRGC, 2015; UNDRR, 2023).

Several academic and science-policy initiatives have highlighted how risks can cascade in complex socio-environmental systems impacting livelihoods, health, social cohesion, and the environment (Avin et al., Reference Avin, Wintle, Weitzdörfer, Ó Héigeartaigh, Sutherland and Rees2018; Homer-Dixon et al., Reference Homer-Dixon, Walker, Biggs, Crépin, Folke, Lambin, Peterson, Rockström, Scheffer and Steffen2015; Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Homer-Dixon, Janzwood, Rockstöm, Renn and Donges2024). Yet, major deficits remain in many governmental risk management procedures to deal with systemic risk (UK House of Lords, 2021; IRGC, 2020; Maskrey et al., Reference Maskrey, Jain and Lavell2023; Schweizer, Reference Schweizer2021). These deficits relate to both assessing and understanding risks (e.g. gathering and interpreting knowledge around hazard probabilities and consequences including multiple dimensions of risk, and how risks are perceived by stakeholders depending on values, beliefs, and interests). They also pertain to managing risks (e.g. failure to consider a reasonable range of risk mitigation options, inability to reconcile the timeframe of risk with decision-making procedures, failure to balance transparency and confidentiality, and failure to build adequate and coherent organisational capacity to manage risk).

A wide range of institutions face these challenges, including national governments as well as multilateral risk management initiatives (e.g. UN Sendai Disaster Risk Framework, International Risk Governance Center, and World Health Organisation). It is clear that understanding and responding to systemic risks will require diverse expertise across sectors/disciplines, and requires disciplines which go beyond traditional risk management approaches by introducing new competencies and approaches, such as systems thinking literacy (Ison & Shelley, Reference Ison and Shelley2016; Oliver, Benini, et al., Reference Oliver, Benini, Borja, Dupont, Doherty, Grodzińska-Jurczak, Iglesias, Jordan, Kass, Lung, Maguire, McGonigle, Mickwitz, Spangenberg and Tarrason2021b).

There is a strong potential for risk managers (e.g. in government and other policymakers) to draw more strongly upon the diverse expertise available in academic institutions, other sectors, and public community groups to span the required breadth of multidisciplinary input. This study, based on a UK project called SysRisk (Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Boazman, Doherty, Dornelles, Gilbert, Greenwell, Harrison, Jones, Lewis, Moller, Pilley, Tovey, Wilde and Yeoman2021a), explores a process by which systemic risks can be appraised, with relevant interventions and key ‘watchpoints’ identified to understand if and how risks are being realised. We focus on three case studies, selected because they already have real-world impacts and so are salient for many decision-makers. They are: (i) Air Quality: reducing health impacts of air pollution, (ii) Biosecurity: improving resilience to zoonotic disease emergence, (iii) Food Security: ensuring access to healthy, safe, affordable food. The process is experimental and therefore this report takes a reflexive approach to understand the possible strengths and limitations of the methodology, with a view to informing future refinements.

2. Methodology

2.1. Selection of expert participants

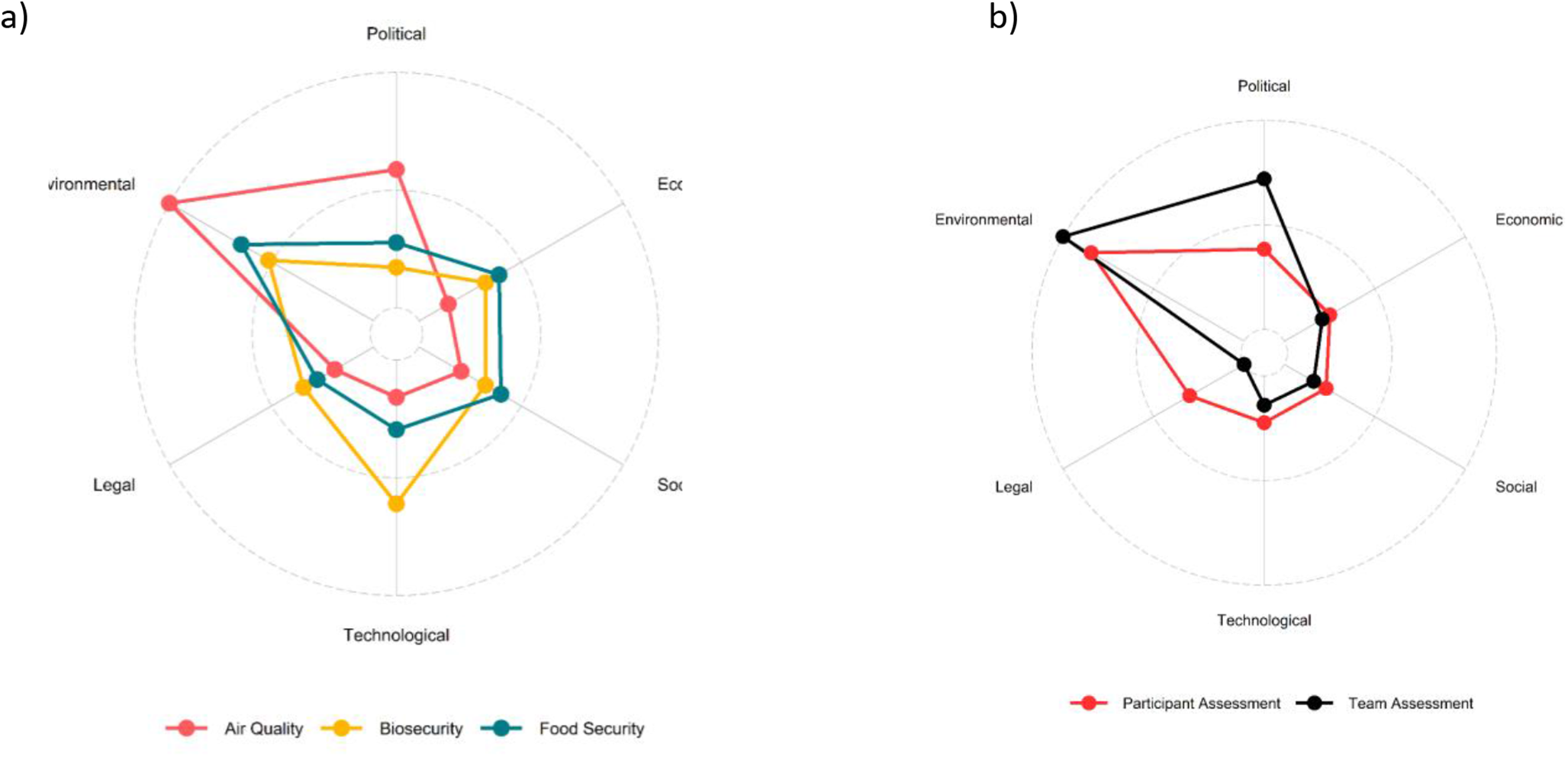

To increase cognitive diversity for each case study, a longlist of potential participants was developed by identifying people with expertise in either the political, economic, social, technological, legal/regulatory, and environmental (PESTLE) aspects of their case study area (Figure 1). Participants were allocated percentages across the six PESTLE categories by SysRisk team members based on review of their research profiles and staff web pages. Twelve participants were recruited for each case study (n = 36 in total). Participants were also asked to score themselves using the same system. This scoring process is further explained in the Supplementary Methods. Ethical approval from a University Ethics committee was received prior to the work commencing.

Figure 1. Panel a, assessment of the participants’ expertise according to ‘PESTLE’ categories for the three case studies, carried out by SysRisk team members (n = 36 participants). Panel b, for the air quality study, comparison of the assessment of participants’ expertise carried out by SysRisk team members versus self-assessment by participants. Only individuals with both team and self-assessment scores are included (n = 9 participants).

2.2. Participatory system mapping software

The project used an open source Participatory System Mapping software (PRSM https://prsm.uk). The PRSM software provides a platform to easily draw networks (or ‘maps’) of systems whilst simultaneously interacting with other individuals (Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Bazaanah, Da Costa, Deka, Dornelles, Greenwell, Nagarajan, Narasimhan, Obuobie, Osei and Gilbert2023). Using PRSM, groups of people, each from their own computer (or tablet), can collaborate in the drawing of a map. Groups of people can participate live because every edit (creating nodes and links, arranging them, annotating them, and so on) is broadcast to all the other participants as the changes are made.

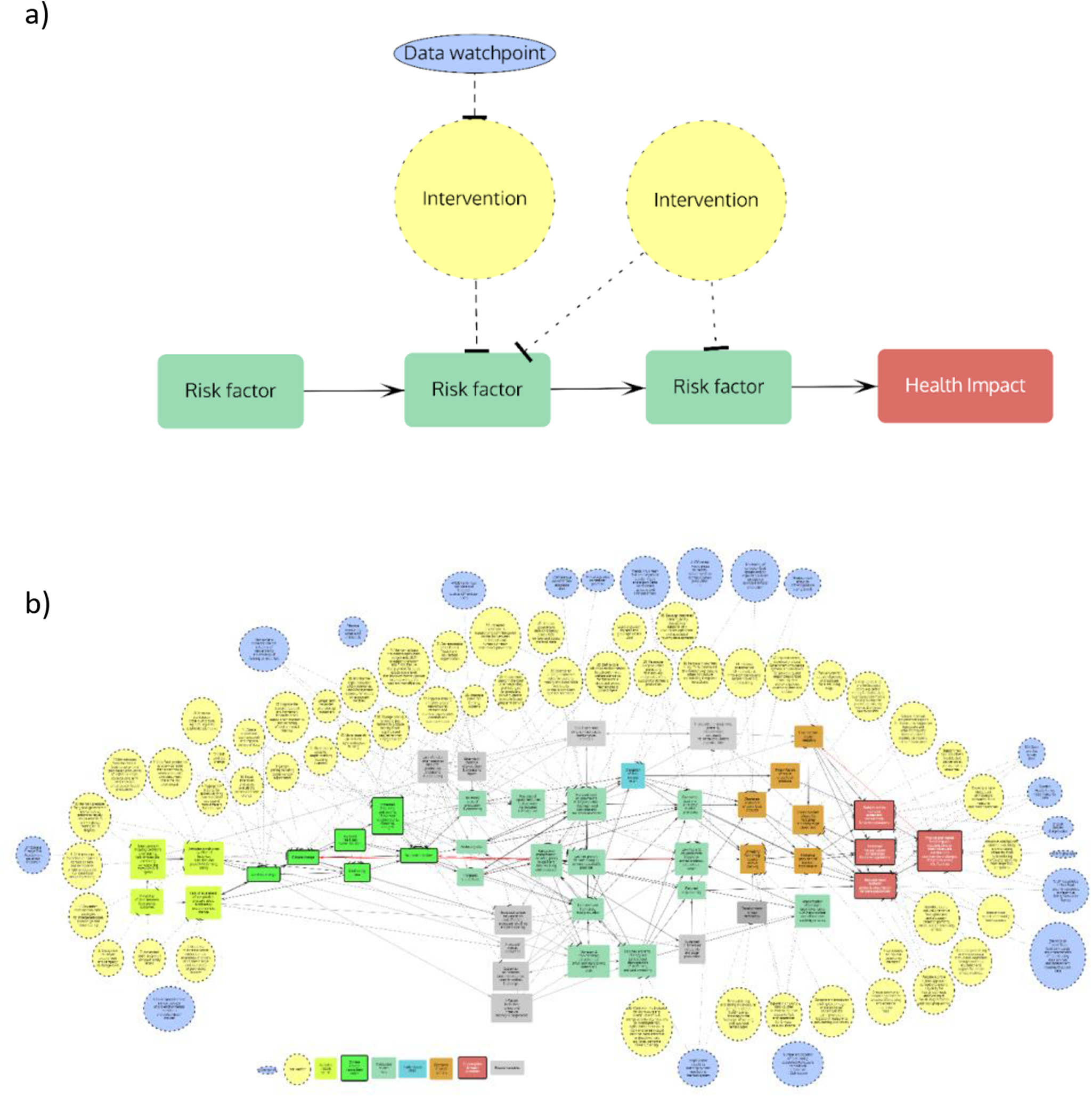

The network or map can be anything that has items (or ‘factors’ or ‘nodes’) connected by links (or ‘edges’). For this project, the items were causal factors linked in a risk ‘cascade’, with interventions to reduce risk and watchpoints to monitor risk (Figure 2). Each item, and the links between them, can have an annotation attached to describe the factor or link in more detail, or to reference other documents.

Figure 2. Panel a shows generic elements of the ‘risk cascades’ developed by participatory mapping. Causal pathways by which risks flow through political, economic, social, technological, legal/regulatory, and environmental spheres are shown in green. The final impact on citizens’ health is shown in red. Interventions to reduce risks are shown in yellow along with data/monitoring initiative ‘watchpoints’ in blue, which can help track whether a specific risk cascade is being realised. Panel b shows an example risk cascade from the workshop on the focal area of soil health for food security (see Table 1 for full details and interactive link). Grey boxes show links to other risk cascades (Table 1).

2.3. Workshop 1: development of risk cascades

Ahead of the first workshops, participants were asked to provide three short narratives or visual flow charts (optionally using the PRSM software) outlining potential ‘risk cascades’ that could result in health impacts in the United Kingdom, relating to their allocated case study topic. We define a risk cascade as a scenario of events linked in a causal chain that leads to some impact (on human health in this case). These were mostly linear but they could also include exacerbating factors (sometimes referred to elsewhere as ‘threat multipliers’). Later in the process, we added data and monitoring watchpoints and interventions to track and reduce risk, respectively (Figure 2). Many of the proposed risk cascades from different participants were related and were edited and amalgamated by the SysRisk team to produce maps grouped by broad themes, each containing multiple cascades (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Finally, short narratives were written in prose describing each particular risk cascade.

Table 1. Project output directory for food security case study. This output directory contains hyperlinks to risk cascades, narratives, and overview theme maps. The four risk cascades prioritised as having high likelihood and impact, examined in workshop 2, are shown in bold. The individual food security risk cascades are highly interconnected, so in workshop 1 we used an overview map to help navigate these linkages (Figure S5). We also included three smaller themed overview maps (right hand column of table) to allow participants to explore the relationships between the different risk cascades

At a separate workshop for each of the three case studies, participants were then asked to comment on and edit the factors and connections on the maps to improve accuracy and clarity. They next added interventions – actions to reduce risk, as well as data watchpoints – data sources or monitoring schemes for adaptive risk governance, to the maps (Figure 2).

After the workshop, the SysRisk team amalgamated duplicate interventions and researched them for more depth and background information. The risk cascades and overview maps were also adapted following participant inputs during the workshop. For the food case study (Table 1), specific recommendations from the National Food Strategy (Dimbleby, Reference Dimbleby2021) were also included as interventions. These were either related to interventions added by participants or subjects raised during the workshop discussion.

2.4. Workshops 2 and 3: Considering interventions in greater depth

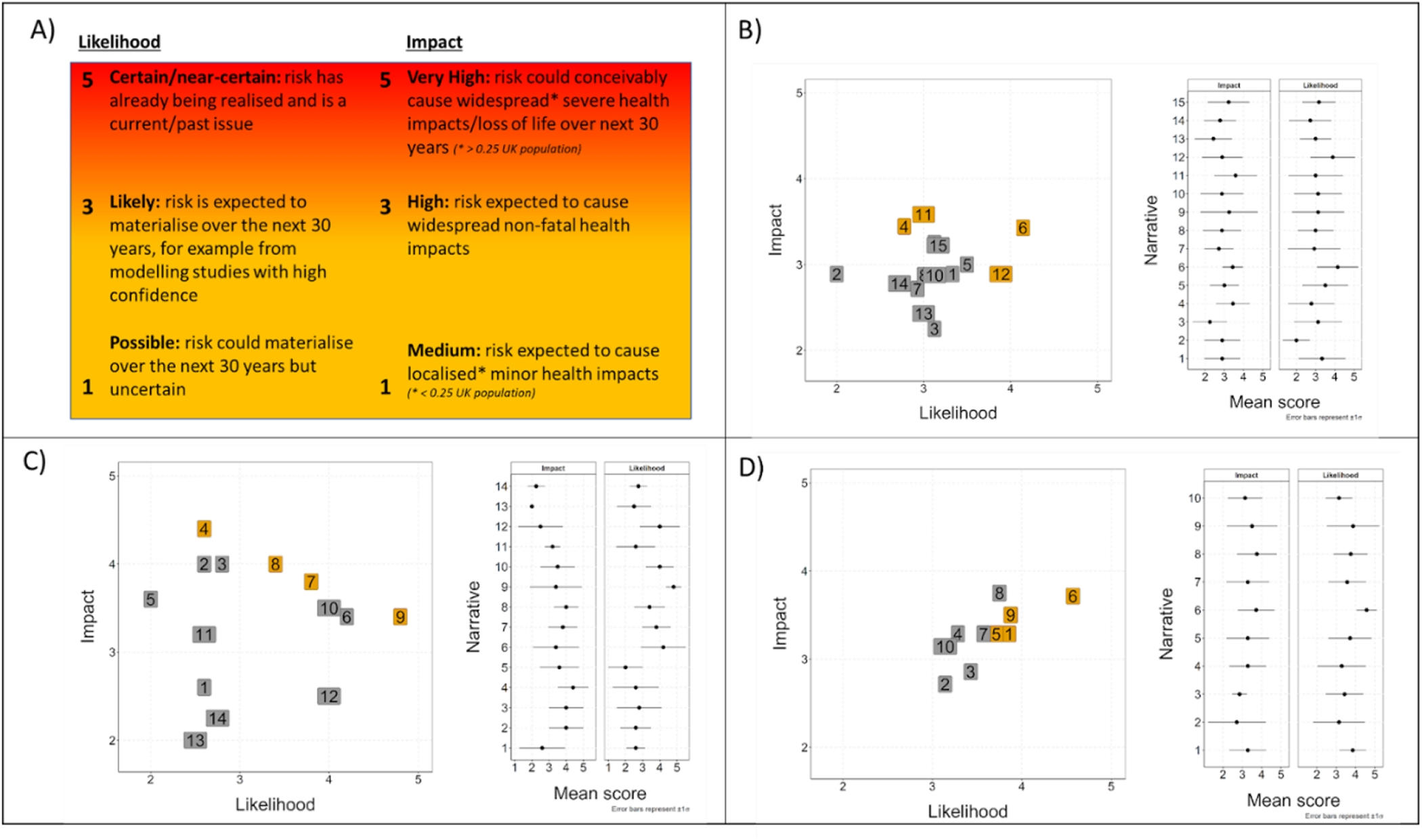

In preparation for workshop 2, the SysRisk team derived a rank order by analysing the risk narratives based on their impact and likelihood using mean scores obtained across participants (Figure 3). The results were used to select four narratives from each case study that scored highly for both impact and likelihood for further exploration in the second workshop.

Figure 3. Scoring criteria for assessing the likelihood and impact of specific risk cascades (panel A). Mean scores and standard deviations as assessed by participants for air quality (B), biosecurity (C), food security, and (D) case studies. Cascades selected for workshop 2 are highlighted in Orange. Cascade numbers: Air Quality (panel B) 1. Weight, 2. Perception, 3. Scavenging, 4. Uptake, 5. Temperature effects, 6. Extreme weather, 7. Net-zero pressure, 8. Financial pressure, 9. Government resources, 10. NHS pressure, 11. Novel pollutants, 12. Domestic emissions, 13. Delivery vehicles, 14. Domestic energy, 15. Pollution resilience; Biosecurity (panel C) 1. Dormant pathogen, 2. Resource prioritisation, 3. Novel research, 4. Malicious actors, 5. Sample transport, 6. Food-borne pathogens, 7. Livestock, 8. Wildlife, 9. Household transmission, 10. Physical and mental health, 11. Vaccine uptake, 12. School closures, 13. Gender gaps, 14. Public health messaging; Food Security (panel D) 1. Soil health decline, 2. Water risks (shortages and floods), 3. Crop pests and diseases, 4. Policy and economic impacts on UK land use, 5. Non-tariff trade barriers, 6. Labour shortages, 7. Trade deals and retailer–grower power relationships, 8. Human transmissible disease, 9. Impact of system shocks such as the pandemic given increased reliance on food aid, 10. Livestock disease with human health impacts.

In separate second workshops for each case study, participants were then invited to assess the four prioritised risk cascades and review the interventions, to answer the following questions: (i) If all these interventions were in place, to what extent would the risk be effectively reduced?; (ii) Are multiple complementary interventions needed?; (iii) In aggregate, what are the main barriers to putting effective interventions in place?; and (iv) Are there unintended consequences of these interventions (or positive co-benefits)?

The third participatory workshop explored protocols to help refine interventions; in particular: (a) how certain interventions might be implemented, and (b) whether interventions reduce multiple types of risk (‘multifunctionality’) or whether they lead to trade-offs across risks. To achieve this, each of the interventions described in the final risk cascades were assessed in two phases. First, individuals scored interventions from their own case study with regard to the extent they were being implemented using the following criteria:

• Yes: Existing policy framework in place, and/or significant business of third sector initiatives deemed to have a significant impact.

• Partly: Part of current policy reform or planned initiatives; some initiatives in place by businesses/third sector.

• No: Some recognition of the problem and discussion of possible actions but negligible coordinated implementation.

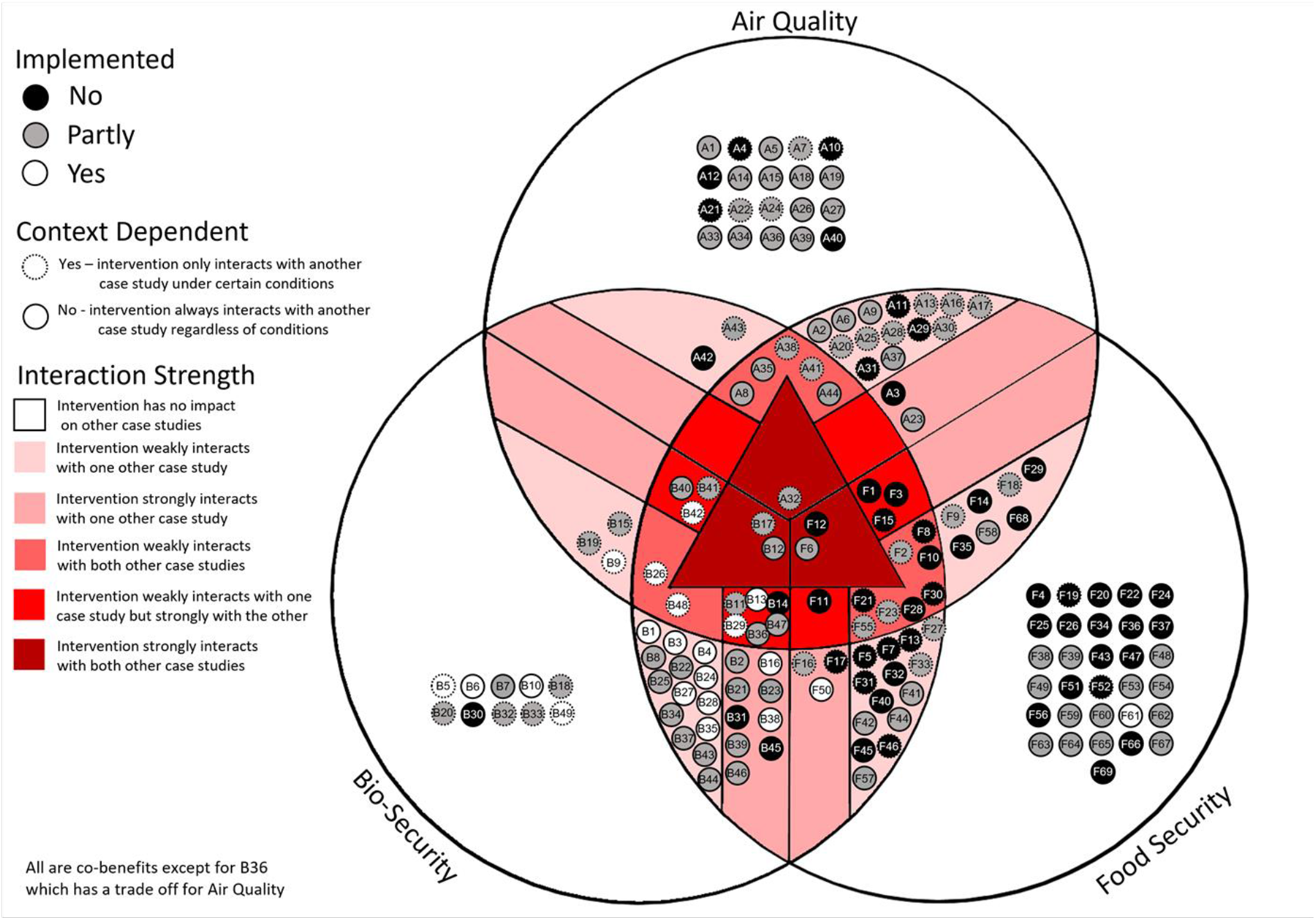

Next, individuals reviewed interventions from the two other case studies to assess whether any of these interventions would have an impact in reducing or increasing risk in their own case study (i.e. their multifunctionality; Figure 4). For example, would interventions identified in the air quality case study have benefits or trade-offs for food security or biosecurity? Each intervention was given one of the following scores: −2 (strong trade-off), −1 (weak trade-off), 0 (no/very limited effect/s), 1 (weak co-benefit), 2 (strong co-benefit). Where intervention impact was deemed to be highly context dependent, an asterisk was added to the number, for example, 2*. Participants were invited to add comments if they felt their scoring required justification, and were also given the option of leaving interventions blank if they felt it was outside of their subject knowledge.

Figure 4. Visualisation of multifunctionality and degree of current implementation of interventions across the three case studies. Interventions listed in the centre of the Venn diagram have multiple benefits in terms of reducing multiple types of risk across the case studies. The intervention identity is shown by a code within each circle and can be found in Tables 1 (food security) or Tables S1 (air quality) and S2 (biosecurity).

In case study-specific groups, participants next used the software Mural(https://www.mural.co/) to develop implementation strategies for a single selected multifunctional intervention. The exercise involved describing (i) specific ways to implement the respective interventions, (ii) identification of enablers and barriers for implementation, (iii) potential negative impacts, (iv) identifying the actors and stakeholders responsible for implementation, and (v) winners and losers if the intervention was implemented.

3. Results

We created 39 risk cascades across the three case studies (air quality, biosecurity, and food security), with 681 watchpoints and interventions listed in total. For each case study, hyperlinks to risk cascades in the interactive PRSM software can be found in an output directory (see Table 1 for food security, Table S1 for biosecurity, and Table S2 for air quality). These also contain links to narratives that describe each directory in prose, with potential interventions to disrupt risk cascades detailed as numeric citations. Participant scoring assessing the likelihood and impact of specific risk cascades is summarised in Figure 3.

In terms of the analysis of different interventions, we found that the biosecurity case study exhibited the most co-beneficial interventions compared with other case studies: 34 of the 49 (70%) interventions in the biosecurity case study were deemed to be co-beneficial to food security, although only 9 (18%) were deemed beneficial for air quality (Figure 4; Table S4). In contrast, interventions in air quality case study generally showed fewer interactions with other case studies: 8 out of 44 interventions (18%) showed evidence of co-benefits in relation to biosecurity (and mostly weak co-benefits); while there were more co-benefits in relation to food security (22 out of 44 interventions; 50%; though 12 of these were deemed highly context-dependent; Table S5). Food security interventions were also sometimes beneficial in terms of reducing risks in the other case studies: out of the 69 interventions for food security, 16 (23%) were synergistic with biosecurity, and 19 (27%) with air quality (Table S6). Across all case studies, there were very few clear trade-offs in terms of an intervention in one case study increasing risk for another (Figure 4), but there were a relatively large number of context-dependent outcomes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Participant selection

We sought to increase the cognitive diversity of participants in this project through a stratified selection procedure. This enabled participants with a breadth of systemic knowledge to work with those with a depth of expertise in particular areas and allowed the cross-fertilisation of ideas and practices from other disciplines. However, there were some limitations and lessons learned from our approach, which we reflect upon here.

As evident in Figure 1a, there was some participant expertise in all categories, reflecting the value in a systematic, stratified selection of participants. However, expertise was not always equally distributed across each category. For example, the air quality case study was strongly represented by environmental and political expertise and less on technological, social, economic, and legal aspects.

As part of the exploration of different protocols, we also asked participants to self-score their expertise. As shown for the air quality case study (Figure 1b), there are some overlaps with assessments by the SysRisk project team, but not a perfect match. For example, the SysRisk team appeared to overestimate political expertise compared with the participant self-assessment. On reflection, self-assessment by the participants is probably a more accurate reflection of expertise, but it necessarily involves a longer lead time in any project. In order to screen which participants to approach initially, a two-stage process of external assessment of expertise followed by participant self-scoring may be worthwhile.

An additional limitation with our approach is that there may be elements of expertise and cognitive diversity not well reflected in these PESTLE categories. For example, the selection of participants for air quality may have been different if we also attempted to stratify selection across various systems that contribute to air quality emissions, such as energy, transport, industry, and health. We did undertake some further categorisation for selecting participants in the food security case study (see Supplementary Methods).

Further reflections can be found in the Supplementary Discussion, in terms of (i) selecting different participants for each part of the process, (ii) ensuring a balance of gender, career stage, and including representatives of communities commonly affected by risks. We discuss participant familiarity with the themes of the project and with systems thinking in general, and also further reflections on the facilitation process.

4.2. Defining boundaries in systemic risk analysis

As described by Cash et al. (Reference Cash, Adger, Berkes, Garden, Lebel, Olsson, Pritchard and Young2006), taking into account different types of scales and cross-scale interactions leads to a more successful assessment of problems and solutions that are politically and ecologically more sustainable. The spatial, temporal, and jurisdictional boundary scales, summarised and presented in Figure 1 of Cash et al. (Reference Cash, Adger, Berkes, Garden, Lebel, Olsson, Pritchard and Young2006), have been used to structure our reflections on boundary choices in this project. In the Supplementary Discussion, we also critically reflect on the project funding focusing on environmental risks.

4.2.1. Spatial boundaries

The focus of our project was on the appraisal of risks to the health of UK citizens, even though those risks may play out across international systems. The backgrounds of participants and their perspectives, both on how risks play out and how interventions need to be implemented across different spatial scales, likely differ from those of policymakers. For example, participants’ underlying worldviews influence the different definitions of food security they hold, which also relates to how they view spatial scale, for example, food security is sometimes equated with UK self-sufficiency (Barling et al., Reference Barling, Sharpe and Lang2008) or the maintenance of the status of food supplies to the United Kingdom, rather than a more universal definition we used in this SysRisk project of accessibility to sustainable and healthy food across the population. Additionally, we found that participants were keen to discuss current or salient risks, for example, recent UK labour shortages and their effects on food security, or housing insulation protests and their influence on policy and air quality. In contrast, other risks such as cybersecurity risks arising from AI technologies (e.g. Radanliev et al., Reference Radanliev, De Roure, Maple and Ani2022) in food, air quality, and biosecurity systems were more neglected. Although the aim of this project was to engage participants in thinking about UK risk reduction and resilience, many threats are actually global ones. This different thinking about spatial scale is relevant for whether participants proposed local, national, or international interventions and implementation ideas. In the air quality space in particular, this is highly dependent on the spatial dynamics of the risk (e.g. indoor vs outdoor air quality). Interventions to address novel pollutants, generally focusing on outdoor spaces, could potentially require international regulation if emitted pollutant species have long atmospheric lifetimes (long-range transport of air pollutants means species emitted abroad may affect the health of UK residents, and vice versa; WHO, 2006). In contrast, some interventions related to working patterns (e.g. a domestic emissions risk cascade regarding home/workplace ventilation) could be implemented locally by each of the four UK nations. This example shows how the spatial consideration of an intervention is dependent on the spatial nature of the risk.

4.2.2. Jurisdictional boundaries

The SysRisk processes focused on UK national government risk mitigation strategies, but it is crucial to consider jurisdictional scale when considering legislative interventions. Adapting the process to do this is very much conditional on what type of intervention is being considered. Scaling of regulatory interventions may be problematic, as scaling down to a local (e.g. council) level may be more difficult as local authorities do not have the same enforcement power as the national government. Equally, there are difficulties scaling up regulatory interventions to the global level as this would usually be dependent on the cooperation and agreement of many nations, which in most cases is not straightforward or timely. On the other hand, education and mindset change interventions, such as stressing relevant hygiene measures to reduce disease transmission, could be rescaled to both local and global levels more easily as implementation is based on influencing public capability, opportunity, and motivation (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011), which can be carried out in various ways without always requiring legislative change.

4.2.3. Temporal boundaries

It is clearly important to specify temporal horizons in the assessment of risk. In this project, the boundaries for this project were limited as we were considering salient environmental risks as part of the national recovery to COVID-19. To raise the profile of environmental risk, these case studies were selected as risks that are likely to be realised over a period of just a few years. Nevertheless, we did factor in long-term processes that cause amplification of risk such as global land use degradation, climate change, geopolitical change, and demographic change.

Understanding risk pathways on long-term timeframes is crucial if we are to build resilience. The most obvious example is around non-linearities (including ‘tipping points’). Although certain risks may not be realised for some time in terms of a dramatic change in state, the erosion of resilience occurs prior to this. For this reason, there has been a call in some disciplines such as ecology to develop indicators of resilience (cf. ‘early warning indicators’) rather than simply monitoring system state (Burthe et al., Reference Burthe, Henrys, Mackay, Spears, Campbell, Carvalho, Dudley, Gunn, Johns, Maberly and May2016; Quinlan et al., Reference Quinlan, Berbés-Blázquez, Haider and Peterson2016; Weise et al., Reference Weise, Auge, Baessler, Bärlund, Bennett, Berger, Bohn, Bonn, Borchardt, Brand and Chatzinotas2020). For example, with regard to food security, pollen delivery to crops is a measure of pollination state (which could theoretically decline relatively quickly), but pollination function resilience based on species richness and functional composition would give a better early warning signal (i.e. showing a more gradual decline which warns of impending crash in pollination function; Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Heard, Isaac, Roy, Procter, Eigenbrod, Freckleton, Hector, Orme, Petchey, Proença, Raffaelli, Suttle, Mace, Martín-López, Woodcock and Bullock2015).

In this project, our data/monitoring watchpoints may give some indicator of system resilience to non-linear changes, but more work is needed on understanding these changes and what to expect (Lenton et al., Reference Lenton, Mckay, Loriani, Abrams, Lade, Donges, Buxton, Milkoreit, Powell and Smith2023). Hence, in addition to data watchpoints, the right models (both qualitative and quantitative) of potential system collapse dynamics are needed, which requires robust underpinning science.

An additional limitation is that the reductionist approach used in this project meant that compounding risks were largely excluded. Although some factors such as land use degradation and climate change were included as exacerbating factors, it was unfeasible to use this approach to exhaustively include all factors whose dynamics over time could result in systems becoming more susceptible to hazards. Therefore, it is important to recognise that our approach, although detailed, is certainly not exhaustive.

4.3. Watchpoints

The participatory process involved the identification of ‘watchpoints’ defined as datasets of monitoring initiatives that help identify if a certain risk is becoming realised, that is, an indicator that the socio-environmental system is changing in such a way that makes that type of risk more likely. These can be found in the risk cascades and narratives (Table 1 and Tables S1 and S2). One constraint was limited time availability, and a specific workshop devoted to identifying watchpoints (rather than combining with the activity to identify interventions) may have been better. Furthermore, it was recognised that some important watchpoints may only be known in closed circles (e.g. national security risk assessments conducted by the government). Bringing in a broader set of experts and providing more time could be valuable for initiatives aiming to track risk in real time (e.g. the UK government Cabinet Office ‘Situation Centre’). In principle, these watchpoints enable early warning of non-linear changes (Lenton et al., Reference Lenton, Mckay, Loriani, Abrams, Lade, Donges, Buxton, Milkoreit, Powell and Smith2023) and rapid propagation of systemic risks. However, they would benefit from careful consideration, involving incorporating into theoretical and empirical models of system resilience, in order to be most useful.

4.4. Types of interventions

Three key points for reflection emerged from the discussion about the range of types of interventions: (i) whether interventions are proactive or reactive, (ii) whether they address mainly shallow or deep leverage points, and (iii) whether they are specific to that case study or provide multifunctional co-benefits to the other case studies. These aspects relate to various strategies for enhancing resilience: robustness (maintain status quo), recovery (bounce back), and reorientation (transform). From the point of view of reducing systemic risks, some aspects of system robustness and recovery can be undesirable (Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Boyd, Balcombe, Benton, Bullock, Donovan, Feola, Heard, Mace, Mortimer, Nunes, Pywell and Zaum2018). This is because they ‘lock in’ aspects of the system that might appear to deliver benefits (e.g. cheap food in the short term; Benton & Bailey, Reference Benton and Bailey2019), but that maintain vulnerability to systemic risks; for example, increasing food insecurity in the longer term through degradation of ecosystem services, such as soil health, pest control, and pollination, on which agriculture depends (Mbow et al., Reference Mbow, Rosenzweig, Barioni, Benton, Herrero, Krishnapillai, Liwenga, Pradhan, Rivera-Ferre, Sapkota, Tubiello, Xu and Shukla2020). In the food security case study, we found discussion about interventions was often focused on those aimed at a reorientation strategy (see ‘horizon three’ thinking referenced above; Sharpe et al., Reference Sharpe, Hodgson, Leicester, Lyon and Fazey2016). Participants were often proposing to address systemic risks through proactive interventions aimed at systemic transformation. In contrast, interventions raised in the air quality and biosecurity case studies tended to be focused on increasing the robustness of the existing system.

4.5. Reactive versus proactive interventions

Interventions can be placed on a scale from purely reactive interventions to highly proactive interventions. Reactive interventions are those put in place to mitigate or adapt to an existing or developing risk, perhaps in response to information from a data/monitoring watchpoint. Proactive interventions are those put in place in anticipation of future risks and include a larger role for prevention. For example, many interventions in the air quality case study were proactive, involving research and regulatory interventions to improve monitoring capacity and to predict and prevent emerging risks such as novel pollutants. Across the case studies, there was a mix of reactive and proactive interventions (e.g. Table S7), but arguably a greater overall focus on proactive interventions, perhaps because several of the pathways through which systemic risk could materialise (the ‘risk cascades’) were still hypothetical.

4.6. Deep versus shallow intervention points

In addition to a preference for proactive interventions, participants emphasised interventions that aim to create systemic change and disrupt the risk cascades, rather than adapt to or mitigate individual factors on the cascades. Meadows (Reference Meadows1999), a seminal researcher in systems thinking, described 12 points in which to intervene in a system, ranging from shallow leverage points such as subsidies, taxes, and standards, to deep leverage points such as ‘changing the rules of the game’, changing people’s mindsets, and new paradigms. With increasing depth comes increasing ability to create system-wide change. Abson et al. (Reference Abson, Fischer, Leventon, Newig, Schomerus, Vilsmaier, von Wehrden, Abernethy, Ives, Jager and Lang2017) aggregated these 12 points into 4 system characteristics: ‘Parameters’ are the modifiable, mechanistic characteristics of the system such as taxes, incentives, and standards, or the stocks and rates of flow of physical elements of a system, such as pollutants, animals, and food products. ‘Feedbacks’ include interactions that drive or provide information about desired outcomes. ‘Design’ includes the social structures and institutions that manage feedback and parameters. ‘Intent’ includes the underlying values, worldviews, and goals of the actors that shape the emergent direction to which a system is oriented (Figure S6). Considering the implementation of interventions through this lens can help demonstrate barriers to systemic change.

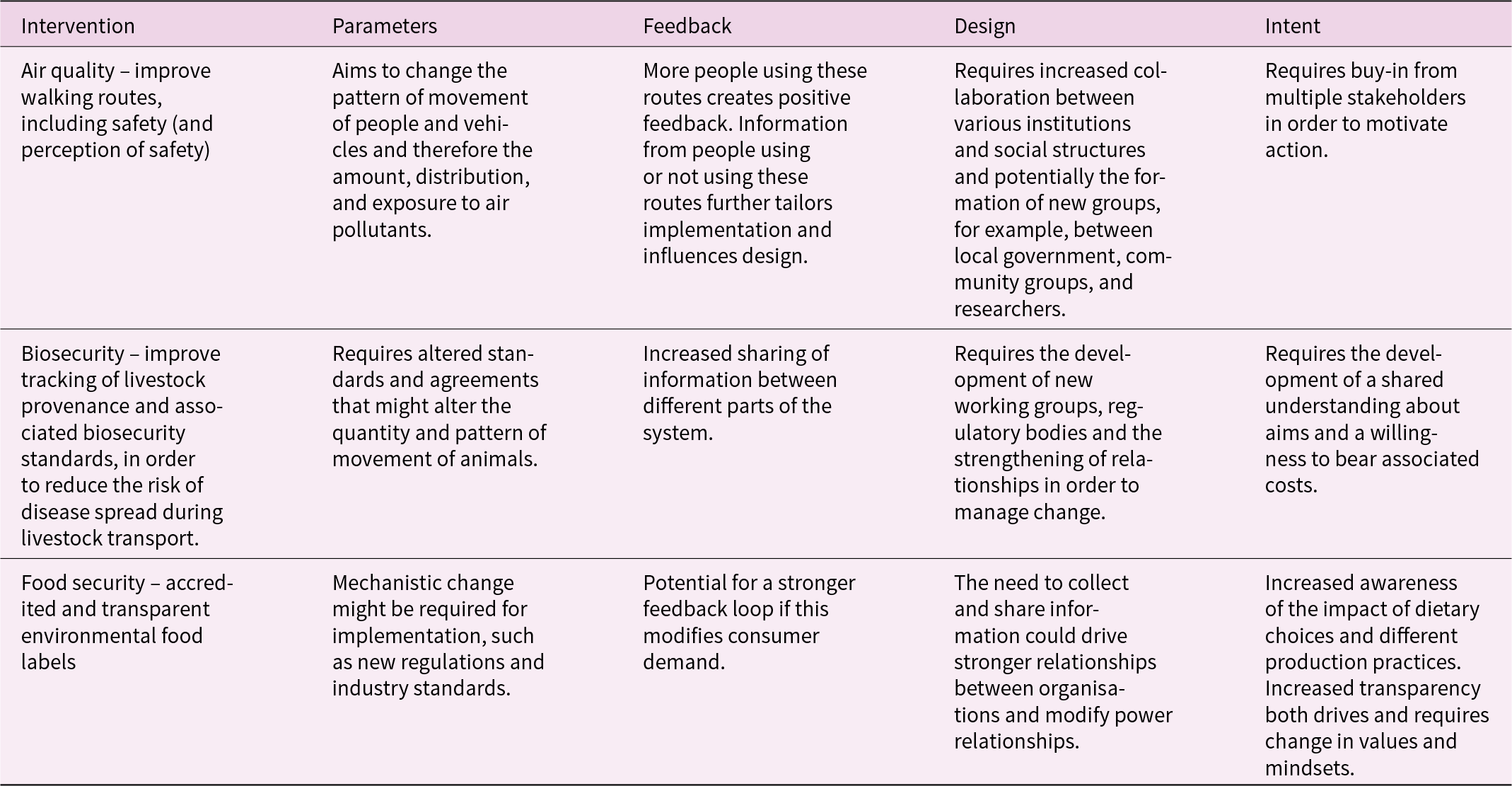

Rather than the interventions identified in this project inherently targeting ‘deep’ or ‘shallow’ system characteristics, the majority involved actions that influenced the system at multiple depths. For example, an air quality intervention to improve walking routes (Table 2) occurs at the parameter level because it alters the movement of people and vehicles, resulting in a change in the amount, distribution, and exposure to air pollutants. However, implementing this requires a change in institutions and social structures, with feedback loops operating to potentially reinforce this change, for example, providing knowledge and capacity to alter transport policy.

Table 2. Example interventions from the three case studies, showing how implementation of interventions can occur at different levels, as categorised by Abson et al. (Reference Abson, Fischer, Leventon, Newig, Schomerus, Vilsmaier, von Wehrden, Abernethy, Ives, Jager and Lang2017). See main text for definitions of these levels

In this way, deeper system characteristics constrain what is possible at shallower system characteristics (Abson et al., Reference Abson, Fischer, Leventon, Newig, Schomerus, Vilsmaier, von Wehrden, Abernethy, Ives, Jager and Lang2017). For example, the success of improving tracking of livestock provenance and associated biosecurity standards at a parameter level is likely dependent on underlying values and institutional capacity (Table 2). A certain amount of change at the ‘intent’ level is needed in order to implement change within standards or properties of the system. However, change in these underlying values and mindsets is then also further enabled by capacity building in institutions and by the creation of feedback loops (Markus & Kitayama, Reference Markus and Kitayama2010; Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Doherty, Dornelles, Gilbert, Greenwell, Harrison, Jones, Lewis, Moller, Pilley, Tovey and Weinstein2022).

In most cases, interventions need to be implemented at multiple depths, or along with other complementary interventions, in order to be effective (OECD, 2021; Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Boyd, Balcombe, Benton, Bullock, Donovan, Feola, Heard, Mace, Mortimer, Nunes, Pywell and Zaum2018). For example, providing food labelling information alone will have a limited impact if this is not perceived to involve accurate information from trusted institutions (Table 2) and if it is not part of a suite of wider complementary interventions that enable behaviour change. A systems approach can encourage coordination between different policy communities to design policy frameworks with interventions across the system (Defra, 2022; European Environment Agency, 2024; OECD, 2021; Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Benini, Borja, Dupont, Doherty, Grodzińska-Jurczak, Iglesias, Jordan, Kass, Lung, Maguire, McGonigle, Mickwitz, Spangenberg and Tarrason2021b).

Many of the interventions identified in this project had a strong focus on awareness raising, which reflects participants’ eagerness for interventions that leverage change on deeper system characteristics to result in transformational change (e.g. Table 2). This is also reflected in some global food system initiatives, such as the Conscious Food Systems Alliance, being developed by the UN Development Programme (Legrand et al., Reference Legrand, Jervoise, Wamsler, Dufour, Bell, Bristow, Bockler, Cooper, Corção, Negowetti, Oliver, Schwartz, Søvold, Steidle, Taggart and Wright2022). However, it is important to note that awareness raising is only one element, with capacity, opportunity, and motivation also required for translation into action (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). This highlights the need for complementary interventions that target multiple elements of the system and risk cascades. There can be a danger in emphasising awareness and educational interventions alone while maintaining an existing institutional framework that strongly constrains physical, economic, and social accessibility and acceptability, and therefore maintains the status quo. Hence, conceptual models which consider complementary interventions comprising a mix of individual, social, and material factors, such as the ‘ISM’ model developed by Darnton & Horne for the Scottish Government may be valuable (Darnton & Horne, Reference Darnton and Horne2013).

In the Supplementary Discussion, we detail some additional reflections about underlying societal differences in aims and definitions of food security at the ‘intent’ level, which may also form major barriers to implementation.

4.7. Multifunctional versus specific interventions

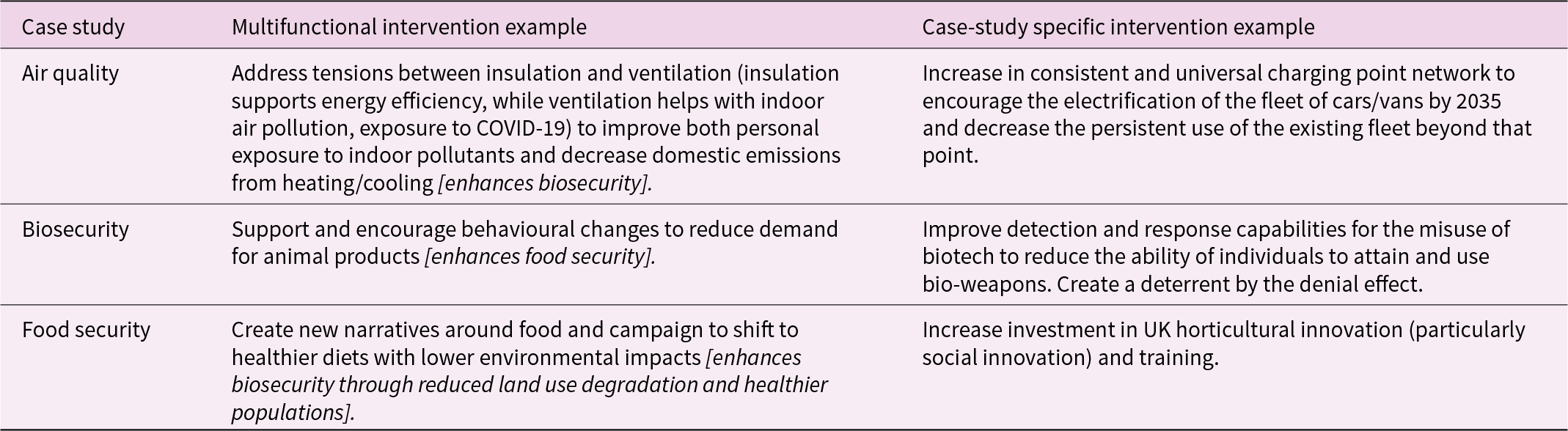

Multifunctionality of interventions, in the scope of this report, was defined as the ability of an intervention to simultaneously impact risks in other case studies, either as a co-benefit or a trade-off (Table 3). In many cases, co-benefits extend beyond our case studies. For instance, nature-based interventions improving food security and biosecurity (e.g. low intensity agroforestry) provide multiple additional functions such as biomass production, carbon storage, flood regulation, and biodiversity conservation (Manning et al., Reference Manning, van der Plas, Soliveres, Allan, Maestre, Mace, Whittingham and Fischer2018). The identification of potential trade-offs amongst interventions can help to reveal lock-in effects where progress in one of the case studies may limit progress in others (Pradhan et al., Reference Pradhan, Costa, Rybski, Lucht and Kropp2017).

Table 3. Example of interventions deemed to be multifunctional in terms of reducing multiple types of risk (across the case studies) versus those with specific, limited benefits to only one case study

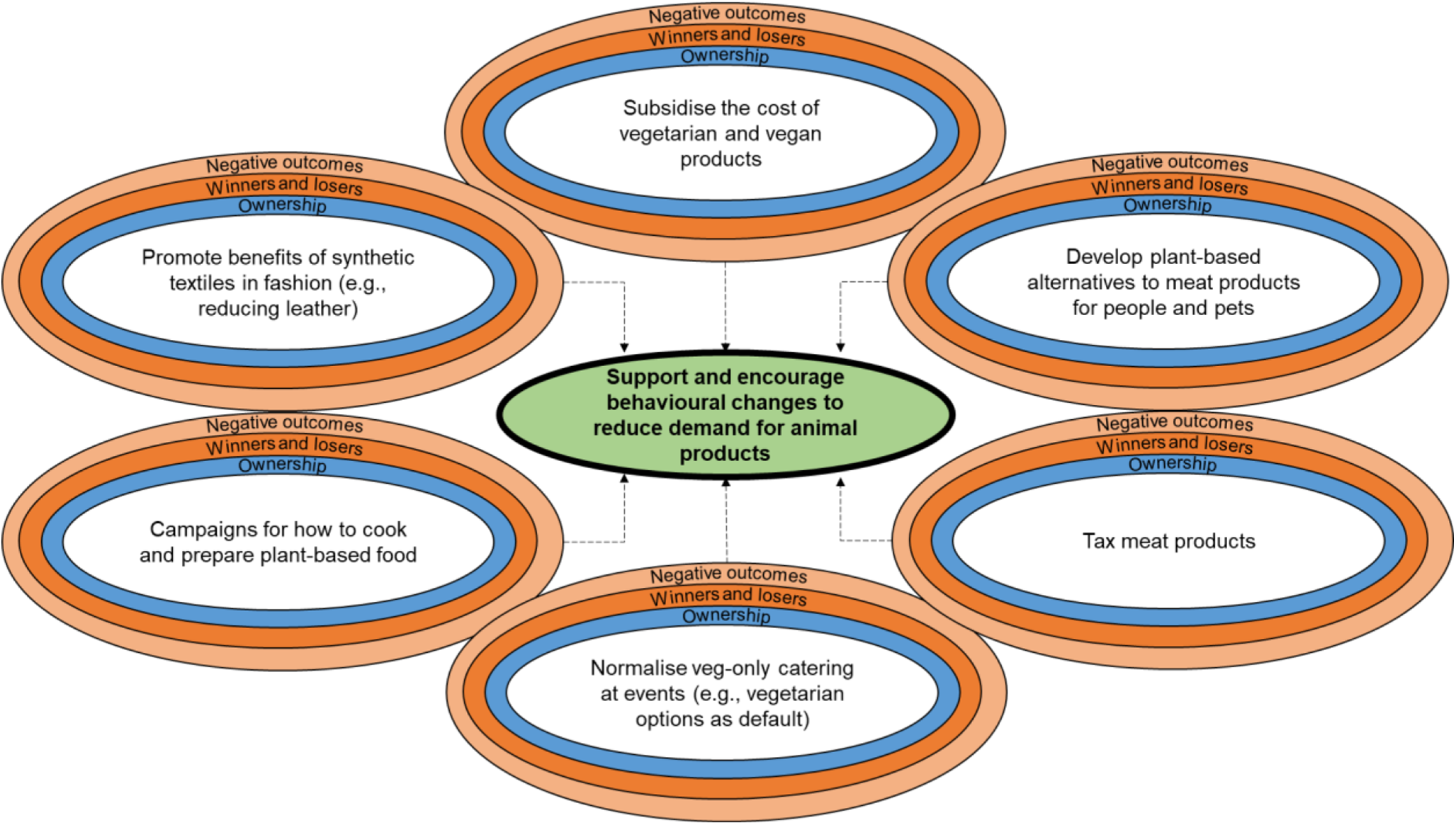

One of our findings was that multifunctional interventions tended to be described in more vague terms, that is, they were less specific in terms of ownership and the allocation of resources for successful implementation. Therefore, we conducted an additional participatory workshop (workshop 3) to explore more tangible implementation strategies. For example, for the biosecurity intervention ‘support and encourage behavioural changes to reduce demand for animal products’, one possible implementation would be to ‘subsidise the cost of healthy vegetarian and vegan products’ (Figure 5). This would be implemented by actors including the government, employers that have staff canteens, and higher education establishments. Potential negative outcomes could lead to increased budget constraints, possible health impacts due to less vitamins and minerals in vegan alternatives (which can be mitigated, importantly, with culinary and dietary training). The implementation of this strategy identified more environmentally sustainable plant-based agriculture as a potential winner, whilst potential losers were suggested to be livestock producers.

Figure 5. Example of different ways that a multifunctional intervention from the biosecurity case study could be implemented.

5. Conclusion: ways forward for systemic risk analysis and governance

This project has critically explored a participatory systems mapping approach with inputs from diverse experts to identify ‘watchpoints’ to track risk and potential interventions to reduce risk. Approaches such as Bayesian belief networks, system dynamics models, and digital twins were all discussed by the project team, but these were considered to be more appropriate as secondary steps compared with an initial, more holistic conceptual approach using participatory systems mapping. However, we were also time-limited in this (12 month) project and, in retrospect, it would have been valuable to have more time to develop the risk cascades, identify key factors, and linkages to other pathways. Therefore, we see these risk cascades as ‘living documents’ to initiate conversation with different actors down the chain about what data exists, what data could exist, and how effective watchpoints could be developed. These further conversations should add additional perspectives and bring new insights that can then be added to the risk cascades and narratives.

Although the participatory systems mapping approach with broad expert input that we advocate allows a more holistic appraisal of risk, it is still inevitably reductionist in terms of focusing on specific risk cascades and interventions. The approach is more comprehensive than risk assessments developed from sector-specific siloes, though it will never, of course, be fully comprehensive. Complex systems, by definition, change in ways that we cannot always anticipate. Therefore, there is a need to complement this type of risk appraisal with more general resilience-building approaches (Baird et al., Reference Baird, Blythe, Murgu and Plummer2024). In practice, some of the interventions identified through these participatory systems mapping address key drivers, and this also tends to promote general resilience. For example, reducing poverty, tackling unsustainable consumption, and building population health are all ‘multifunctional’ interventions that address specific risks, as well as building resilience to unknown threats (Lade et al., Reference Lade, Haider, Engström and Schlüter2017).

We piloted combining our participatory systems mapping with additional systems approaches to help prioritise interventions. This broader lens helps to identify interventions across different sectors and move beyond solely reactive responses to risk (i.e. ‘sticking-plaster’ interventions aimed at proximate symptoms), and towards addressing deeper drivers of change. This inevitably produces a large number of possible interventions. Policy teams often have strong expertise in some elements of prioritisation, such as considering the cost, feasibility, and deliverability of interventions. Additional elements that need to be considered include equity issues (e.g. losers/winners), trade-offs, and co-benefits (‘multifunctionality’) of interventions. Our project found that certain interventions are relatively neglected, even though they would address multiple types of risk. This is perhaps inevitable given the siloed nature of government departments and can be improved through further development of cross-cutting risk analysis initiatives along with more integrated policy development for implementing interventions. Systems thinking methods and competencies can also help to identify the multiple outcomes of interventions in terms of trade-offs and synergies (European Environment Agency, 2020; Griggs et al., Reference Griggs, Nilsson, Stevance and McCollum2017; Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Benini, Borja, Dupont, Doherty, Grodzińska-Jurczak, Iglesias, Jordan, Kass, Lung, Maguire, McGonigle, Mickwitz, Spangenberg and Tarrason2021b). Thus, participatory systems mapping to identify multiple risk cascades and intervention points is not the end of the risk appraisal process, but instead the first step in a process which can also use system methods to help further refine and prioritise interventions (Hochrainer-Stigler et al., Reference Hochrainer-Stigler, Deubelli-Hwang, Parviainen, Cumiskey, Schweizer and Dieckmann2024).

Taking these recommendations forward will require a significant investment in systemic risk appraisal capacity. Cost-benefit analysis of such investments is challenging when the risks by definition cannot be easily defined in probabilistic terms. Yet, recent past experience alone shows how impacts such as COVID-19, air quality, and food insecurity are hugely costly to a nation. Extending this to other types of systemic risk that are expected to materialise under rapid global change (Figure 1), and significant capacity building to appraise possible risk pathways and identify key watchpoints and interventions would seem a wise investment. Such capacity is likely best facilitated through the national government, but should no doubt involve wide-ranging inputs from different academic disciplines and representatives from key sectors and/or ‘activity systems’. Furthermore, for the analysis of very complex risks surrounding wicked problems that involve value judgements, involving representatives from the general public is also worth carefully considering (IRGC, 2020), in order to best capture plural values and perspectives as well as maximising cognitive diversity. The most appropriate ‘knowledge architecture’ (cf. Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Benini, Borja, Dupont, Doherty, Grodzińska-Jurczak, Iglesias, Jordan, Kass, Lung, Maguire, McGonigle, Mickwitz, Spangenberg and Tarrason2021b) to build capacity in systemic risk assessment needs further consideration, but given the high likelihood and impact of many of these risks, there is urgency in moving forward as soon as possible. We hope that this SysRisk project and the reflections on lessons learnt provide some useful input towards developing systemic risk assessment processes that might be valuable. These will need to be combined with lessons from other ‘experiments’, for example, those that explore the best way to appraise the trade-offs and co-benefits, distributional (equity impacts), cost, and feasibility of various interventions. Once again, given the wicked nature of these problems, it is likely that any approaches facilitated by national governments should also involve diverse participatory inputs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2025.10038.

Acknowledgements

The project was funded by UK Research and Innovation under the project title ‘SysRisk- Systemic environmental risk analysis for threats to UK recovery from COVID-19’ (ref NE/V018159/1). The project was coordinated by Kelly Boazman, University of Surrey and supported through in-kind support from the UK Department for Food Environment and Rural Affairs (Defra). We are deeply grateful to the experts for their essential contribution to developing the participatory systems maps described in this study. For the air quality case study these were: Amber Yeoman and Shona Wilde, University of York; Jo Barnes, University of the West of England Bristol; Brian Castellani, University of Durham; Emma Garnett, King’s College London; David Green, Imperial College London; Sarah Legge, Environmental Protection UK; Caroline Mullen, University of Leeds; Eloise Scotford, University College London; Rahat Siddique, Confederation of British Industry; John Stedman, Ricardo Energy and Environment; Heather Walton, Imperial College London; Rose Willoughby, Defra; Stefan Reis, UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. For the biosecurity case study these were: Ben Ainsworth, University of Bath; Mark Burgman, Imperial College London; Marina Della Giusta, University of Reading; Mark Eccleston Turner, Keele University; Simon Gubbins, The Pirbright Institute, Piers Millett, University of Oxford; Silviu Petrovan, University of Cambridge; Robert Smith, University of Sheffield; Lalitha Sundaram, University of Cambridge; James Wagstaff, University of Oxford; Simon Whitby, University of Bradford. For the food security case study these were: Tim Benton, Chatham House; Dan Crossley, Food Ethics Council; Tom Curtis, 3Keel; Caroline Drummond, Linking Environment And Farming (LEAF); Alan Hayes, Consultant; Mark Horler, UK Urban AgriTech (UKUAT), Maria Jennings, Food Standards Agency; Melville Miles, Greencore; Maddy Power, University of York; Ben Raskin, Soil Association; Yaadwinder Sidhu, Defra; Alastair Trickett, Trickett Farming.

Author contributions

THO conceived the study and all authors were involved in study design, workshop facilitation, results synthesis, and writing the article.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the UK Research and Innovation (research grant NE/V018159/1) and in-kind support from UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Competing interests

Author THO is lead educator on an open online course about systems thinking, member of Food Standards Agency science council and the Office for Environmental Protection expert college, and a member of the international Accelerating Systemic Risk Assessment (ASRA) network. Authors BD, AD, MPG, LH, IMJ declare no conflicts. Author AL is Chair of the Department for Transport Science Advisory Council and the Defra Air Quality Expert Group. Author SM is a member of the Department for the Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (Defra) Air Quality Expert Group. Author NG is a Director of CECAN Ltd., which carries out evaluation consultancy relating to sustainability and environmental policies.

Data availability

N/A.