Introduction

By mid‐February 2022, around 405 million people have been infected with the novel coronavirus SARS‐CoV‐2 (Johns Hopkins University, 2022).Footnote 1 With the rapid spread of the virus and the decisive shutdown of social and economic activities around the globe, citizens have experienced large‐scale exposure to the consequences of such a pandemic not only in terms of risks to their own health and that of their loved ones but also with regard to economic recession and a compartmentalization of everyday life enforced by social distancing measures. Previously open borders regularly crossed by people were closed within days or even hours. Across the globe, political leaders and epidemiologists relied on restricting access to countries for outsiders, sometimes banning citizens from foreign nations. At the same time, out‐group negativity rose significantly as demonstrated by anti‐Asian hate speech and crime (Dhanani & Franz, Reference Dhanani and Franz2020; Reny & Barreto, Reference Reny and Barreto2020) or the use of racial slurs to denote the origins or particular variants of the virus targeted against for example, Brazil, China, India, South Africa or the United Kingdom (van Bavel et al., Reference Bavel, Baicker, Boggio, Capraro, Cichocka, Cikara, Crockett, Crum, Douglas, Druckman, Drury, Dube, Ellemers, Finkel, Fowler, Gelfand, Han, Haslam, Jetten and Willer2020). In that sense, the exact nature of setting criteria for belonging to national in‐ and out‐groups grew increasingly important.

This is the starting point of our investigation. We want to find out whether exposure to the Covid‐19 pandemic threat is reflected in our understanding of national belonging. To evaluate the impact of exposure to the threat posed by the Covid‐19 pandemic on conceptions of nationhood, we refer to the behavioural immune system (BIS) hypothesis, also known as the parasite stress theory (Murray & Schaller, Reference Murray and Schaller2016; Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014). The behavioural immune system hypothesis links the prevalence of disease‐causing parasites to an increased avoidance of unfamiliar out‐group targets and to a strengthened cohesion with close in‐group targets in order to inhibit contact with pathogens (Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Hill and Murray2018, p. 3).Footnote 2 By focusing on how boundaries between the in‐group and out‐group(s) are drawn, we study conceptions of nationhood as a major embodiment of group membership across the globe (Ariely, Reference Ariely2018; Greenfeld & Eastwood, Reference Greenfeld, Eastwood, Boix and Stokes2007; Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999). Given that nation states were the main institutions for combating Covid‐19, especially at the onset of the pandemic, nations should also provide the most relevant in‐group in this particular context.Footnote 3 Further, we are interested in the mechanisms linking the threat of the pandemic to conceptions of nationhood. Accordingly, we tie together insights of the behavioural immune system hypothesis with the affective intelligence theory (AIT), a common model of emotional processing in political science and sociology (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000). We argue that emotions triggered by exposure to the Covid‐19 pandemic threat shape how citizens form their conceptions of nationhood.

Using an original survey in six European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom) during the first peak of the pandemic in late April and early May 2020, we analyze the impact of both individual threat experience and exposure to the pandemic at the regional level through hierarchical analyses of 105 European regions. Our empirical analysis, which combines both comparative and within‐country models, shows that exposure to the pandemic is indeed linked to stronger ethnic conceptions of nationhood. This effect proves to be conclusive for both levels of analysis (individual and contextual). We also find that anger is a substantial mediator of this relationship and has primacy over feelings of fear, which reflects other recent findings in political psychology referring to emotional responses to threat (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Valentino, Vasilopoulos and Foucault2019).

Overall, this study contributes to existing research in several ways. First, in the absence of real‐world data from global pandemics, direct measurements of health threat exposure by infections are missing. In order to map pathogen exposure, previous studies have focused on the experimental design of (artificially) constructed health threats, exposure to disgust experiences, the creation of macrolevel indices of pandemic exposure based on parasite presence in a society or fatalities caused by infectious diseases (Albertson & Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015; Faulkner et al., Reference Faulkner, Schaller, Park and Duncan2004; Murray & Schaller, Reference Murray and Schaller2016; Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014, Reference Thornhill, Fincher, Workman, Reader and Barkow2020; Tybur et al., Reference Tybur, Frankenhuis and Pollet2014). Consequently, our approach of directly operationalizing Covid‐19 exposure puts pandemic threat as such into focus and, for the first time, makes it possible to evaluate how direct perceptions of threat from an infectious disease on a global scale affect definitions of group membership, particularly conceptions of nationhood.

Second, while existing theories mostly aim to account for the impact of fear as one single threat‐oriented emotion on political attitudes, we build on the insights of functional neuroscience perspectives and the AIT and scrutinize the role of fear and anger as two pivotal emotions activated simultaneously, yet distinctly, in threatening situations. Third, while most studies referring to emotional responses to threatening stimuli rely on single country studies, we provide a fitting analysis with a rich, comparative dataset to study the effects of the Coronavirus pandemic. Finally, we offer a theoretical argument for linking pandemic exposure with views on belonging to in‐ and out‐groups that has only tentatively been touched upon by previous political science research. Consequently, the present study adds a likely crucial explanatory variable to the research field of national identity, which mainly focuses on the impact of issues like globalization, populism or social status (Ariely, Reference Ariely2018; Inglehart & Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2017; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). Indeed, including pathogen avoidance in previous explanations of political values and behaviours has far‐reaching implications for our understanding of societal processes since predisposed, evolutionary traits are very stable and deeply enshrined in human psychology even if we are not aware of them most of the time (Aarøe et al., Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017, p. 281).

Theoretical framework: Exposure to pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood

Preventing contagion with infectious diseases like Covid‐19 and coping with the consequences in case of an infection have been major drivers of human attitudes and behaviour since ancestral times (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Fincher and Walasek2016; Faulkner et al., Reference Faulkner, Schaller, Park and Duncan2004; Gilles et al., Reference Gilles, Bangerter, Clémence, Green, Krings, Mouton, Rigaud, Staerklé and Wagner‐Egger2013; Murray & Schaller, Reference Murray and Schaller2016; Navarrete & Fessler, Reference Navarrete and Fessler2006; Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014). Biological sciences as well as evolutionary psychology demonstrate that the prevalence of infectious diseases and related parasites has led to the development of not only the classical immune system but also of a behavioural one as ‘a motivational system […] inhibiting contact with disease‐causing parasites’ (Murray & Schaller, Reference Murray and Schaller2016, p. 76; see also Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Hill and Murray2018). From the viewpoint of natural selection, the ‘behavioral prophylaxis’ (Schaller, Reference Schaller and Buss2016, p. 299) provided by this BIS is more efficient than the costly (i.e., resource intensive) immunological reactions of the body (Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Hill and Murray2018).

Overall, if individuals view themselves as comparatively vulnerable to becoming infected, for example by living in an area of high parasite stress or due to having certain medical conditions, the BIS is activated, which in turn triggers certain attitudes and ways of behaviour by these individuals. This ‘functional flexibility’ (Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Hill and Murray2018; Murray & Schaller, Reference Murray and Schaller2016) or context‐dependent adoption (Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill, Fincher, Workman, Reader and Barkow2020) incentivizes individuals to hold more negative views of out‐groups posing potential infection risks (Aarøe et al., Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017; Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Hill and Murray2018; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Fincher and Walasek2016; Faulkner et al., Reference Faulkner, Schaller, Park and Duncan2004). Such negativity stems from the notion that members of out‐groups often hold different values or patterns of behaviour with little compatibility to combat threatening parasites (Navarrete & Fessler, Reference Navarrete and Fessler2006, p. 271). Correspondingly, individuals portray greater loyalty towards one's in‐group, which is unlikely to carry pathogens to which one has not yet become immune, but is likely helpful in mitigating the consequences of an infection (Navarrete & Fessler, Reference Navarrete and Fessler2006; Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2004; Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014).

Consequently, the extent of one's interaction with members of out‐groups results from a trade‐off between the advantages of interacting with out‐groups and the (perceived) risks of contracting potentially dangerous diseases from doing so (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Fincher and Walasek2016; Faulkner et al., Reference Faulkner, Schaller, Park and Duncan2004; Navarrete & Fessler, Reference Navarrete and Fessler2006; Oaten et al., Reference Oaten, Stevenson and Case2009; Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014, Reference Thornhill, Fincher, Workman, Reader and Barkow2020). Importantly, individuals do not deal with this trade‐off by ways of a cost‐benefit calculation under perfect information. Instead, people rely on cues and heuristics to assess infection risks (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Fincher and Walasek2016, p. 100) and do not even need to be conscious of doing so (Navarrete & Fessler, Reference Navarrete and Fessler2006, p. 280). In case the (perceived) risks of infection are high enough to push this trade‐off in this direction, the BIS may activate a set of attitudes and behaviour referred to as ‘assortative sociality’ to prevent contagion (Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill, Fincher, Workman, Reader and Barkow2020, p. 169). These attitudes and behaviours include stronger in‐group orientations, an aversion to new ideas and hostility towards outsiders.

The idea of the BIS and its underlying psychological mechanisms have received substantial empirical support, especially regarding more negative attitudes towards out‐groups if the prevalence of infectious pathogens is high (Aarøe et al., Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017; Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Hill and Murray2018; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Fincher and Walasek2016; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Schaller and Park2009; Faulkner et al., Reference Faulkner, Schaller, Park and Duncan2004; Fincher & Thornhill, Reference Fincher and Thornhill2012; Gilles et al., Reference Gilles, Bangerter, Clémence, Green, Krings, Mouton, Rigaud, Staerklé and Wagner‐Egger2013; Krings et al., Reference Krings, Green, Bangerter, Staerklé, Clémence, Wagner‐Egger and Bornand2012; Navarrete & Fessler, Reference Navarrete and Fessler2006; Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014, Reference Thornhill, Fincher, Workman, Reader and Barkow2020). Whereas results from previous studies lend clear support to an increased out‐group negativity in the face of pathogen stress, research lacks a thorough understanding of whom people actually conceive of as belonging to their respective in‐ and out‐group(s). This is even more astonishing given the established view that definitions of group membership are of paramount importance in this context (Navarrete & Fessler, Reference Navarrete and Fessler2006; Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014).

To address this research gap, this paper focuses on the relationship between pandemic threat and conceptions of national belonging, which today constitute the major form of group attachment around the world (Davidov, Reference Davidov2009; Greenfeld & Eastwood, Reference Greenfeld, Eastwood, Boix and Stokes2007; Lenard & Miller, Reference Lenard, Miller and Uslaner2018; Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999). Since adaptive immunity is highly localized, out‐group members may be (perceived as) hosts to novel parasites to which the immunological defences of one's in‐group are not yet adapted (Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014). Moreover, out‐group members are likely to be unaware of – and thus violating – local rituals, norms and customs implicitly relevant in preventing infection with local parasites (Kusche & Barker, Reference Kusche and Barker2019; Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014). In this sense, it is imperative to study precisely how delineations between the in‐group and out‐group(s) are constructed to gain a thorough understanding of the applicability of the behavioural immune system hypothesis.

Although many ways of distinguishing between in‐ and out‐group(s) are conceivable in the context of a pandemic, national membership should be pivotal as it creates borders to combat an infectious disease geographically (limiting the territorial spread), politically (access to health care and large‐scale containment measures) and socially (grouping of similar people with shared rituals, values and norms) as stipulated by the BIS‐hypothesis. In the context of the latter, national identity is particularly important for constructing perceptions of sameness (Anderson, Reference Anderson2006; Greenfeld & Eastwood, Reference Greenfeld, Eastwood, Boix and Stokes2007). National membership based on ethnic criteria as a ‘thick’ set of criteria (Berg & Hjerm, Reference Berg and Hjerm2010) provides many of the cues regarding norms, values and other disease‐inhibiting behaviours aiming to protect oneself and the in‐group that have developed over the course of evolution.

Conceptualizing national identity, this source of group membership constitutes one of the most extensively researched topics in the social sciences. Current research addresses the question of its emergence as a product of nationalist movements (Anderson, Reference Anderson2006; Gellner, Reference Gellner1983; Hobsbawm, Reference Hobsbawm1992; Hobsbawm & Ranger, Reference Hobsbawm and Ranger1983), its lasting impact on modern societies (Calhoun, Reference Calhoun2007; Newman, Reference Newman2000) or the differences between nationalist and patriotic identities (Ariely, Reference Ariely2020; Davidov, Reference Davidov2009; Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999; Schatz & Staub, Reference Schatz, Staub, Bar‐Tal and Staub1997). Besides these issues, the content dimension of national identity is decisive for setting the criteria according to which national membership is constructed (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Wong, Duff, Ashmore, Jussim and Wilder2001; Helbling et al., Reference Helbling, Reeskens and Wright2016).Footnote 4

Following the seminal work of Hans Kohn (Reference Kohn1939), research on national identity tends to distinguish between ethnic and civic conceptions of nationhood, which define what people consider necessary for being a ‘true’ member of any nation. On the one hand, ethnic conceptions of nationhood give priority to objectivist criteria for national belonging, which refer to national ancestry, being born in a country or adhering to a particular religious belief (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker1992; Lenard & Miller, Reference Lenard, Miller and Uslaner2018; Reeskens & Hooghe, Reference Reeskens and Hooghe2010). As such criteria are considered largely fixed, ethnic views on nationhood treat national boundaries as generally impermeable and fixed for most individuals (Sarrasin et al., Reference Sarrasin, Green and Assche2020; Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2008). In that sense, people are unlikely to change their national belonging over the course of their lives even if they relocate to another nation. Civic conceptions of nationhood, on the other hand, revolve around adherence to an explicitly political culture, its norms and values and knowledge of the national language (Helbling et al., Reference Helbling, Reeskens and Wright2016; Ignatieff, Reference Ignatieff1993). Such views on nationhood gained prominence in the context of the French Revolution and invite any person interested to join another nation as long as they conform with certain values and take part in the respective nation's political life irrespective of where they were born or where their ancestors originated from (Habermas, Reference Habermas and Gutman1994; Luong, Reference Luong, Verdugo and Milne2016). Moreover, a civically informed notion of the nation conceptually relates to a higher acceptance of immigration and an endorsement of multiculturalism, which is substantially different from ethnic conceptions of nationhood (Ariely, Reference Ariely2020; Simonsen, Reference Simonsen2016). Importantly, ethnic and civic conceptions of nationhood are mostly ideal types since most people combine elements of both in defining membership to their own nation (Lenard & Miller, Reference Lenard, Miller and Uslaner2018; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Citrin and Wand2012) and this combination may be re‐assessed regularly to adapt to developments both within an individual's mindset and outside their immediate locus of control. To sum up, these differences provide a valid theoretical framework for studying patterns of national boundary making to define membership of the in‐group (Ariely, Reference Ariely2020).

With respect to the relationship between pandemic threat and different conceptions of nationhood, we argue that wariness towards out‐group members resulting from the activation of the BIS resonates well with more exclusive conceptions of nationhood. As stipulated by the concept of assortative sociality, members of out‐groups are denied the possibility of becoming ‘true’ members of the respective nation due to their lack of national ancestry and their birth in another country. Further, the behavioural immune system may trigger more clear‐cut distinctions between in‐ and out‐groups (Murray & Schaller, Reference Murray and Schaller2016; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Zhang, Anderson, Gasiorek, Bonilla and Peinado2012), which also supports ethnic conceptions. Consequently, citizens being more exposed to a pathogen‐rich environment, such as one hit by the Coronavirus pandemic, should be more inclined to hold ethnic conceptions. As opposed to ethnic views on nationhood, civic views are generally more welcoming towards outsiders aspiring to become part of another nation and consider national boundaries as permeable and flexible. Given that the requirements for joining any nation refer only to political norms and values as well as to the national language, this notion runs somewhat contrary to the desire for cue‐based similarity of cultural norms and practices stemming from the heuristics used by the BIS‐hypothesis. Consequently, we expect ethnic conceptions of nationhood to be more prevalent in environments with higher exposure to infectious diseases, whereas civic views should be less widespread in such areas.

H1: Individuals exposed to the Covid‐19 pandemic threat are more likely to hold ethnic conceptions of nationhood and are less likely to embrace civic ones.

Beyond establishing these direct links between pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood, we are interested in potential mediating mechanisms. Here, emotions move into the centre of analytical interest. When the BIS perceives an infection risk, it triggers adaptive psychological responses – including the activation of aversive emotional states and cognitive knowledge structures in working memory that expedite behavioural avoidance or the demand for controlling the infectious disease (Schaller & Park, Reference Schaller and Park2011, p. 99; Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014, p. 12). Research from political psychology follows neural process theories arguing for a physical location of different emotions in the brain (Gray, Reference Gray1987). Drawing on these insights, affective intelligence theory posits that three brain systems operate constantly and routinely to sort information we confront (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000, Reference Marcus, Valentino, Vasilopoulos and Foucault2019). When the first system responds with enthusiasm, it signals that all is well. The second system relies on anxiety or fear to signify the extent to which circumstances are novel or uncertain. A third system focuses on anger signalling that a threat to familiar norms and practices of thought and action exists. These brain systems operate constantly and routinely to sort information we confront. In particular, the latter two emotional states emerge as a response to threat (Marcus et al., 2019). AIT holds that all relevant appraisals are executed simultaneously and largely independently. Thus, rather than feeling angry or fearful, individuals feel angry and fearful when being confronted with a threat (Vasilopoulos et al., Reference Vasilopoulos, Marcus, Valentino and Foucault2019). Whichever system and thus emotion is more robust, at any given moment, will determine the course of action taken (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Groenendyk and Valentino2010; Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000; Vasilopoulos et al., Reference Vasilopoulos, Marcus, Valentino and Foucault2019).

Following AIT, we assume that the novelty of the Covid‐19 pandemic may cause fear, since what is unknown may also be dangerous, disrupt security and induce uncertainty. Moreover, fear is linked to a consideration of alternative options to the status quo in the face of uncertainty (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Valentino, Vasilopoulos and Foucault2019, p. 120). A tightening of membership criteria and a stronger emphasis on exclusive, ethnic views on nationhood poses an important alternative as compared to previously widespread definitions of national membership emphasizing other factors beyond objectivist criteria (Abascal, Reference Abascal2020; Kenworthy & Jones, Reference Kenworthy and Jones2009). Second, we can also anticipate that the detrimental circumstances surrounding the crisis cause anger. This emotional state of aversion arises particularly if we face challenges to central norms that we consider fundamental to the social or political order. The permeability of national borders may be viewed as one major example for such challenges in contemporary societies altering previously existing structures of society (Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). Therefore, we hypothesize that both fear and anger mediate the relationship between exposure to the pandemic threat and the political orientations toward nationhood.

H2: Feelings of fear and anger mediate the relationship between exposure to the Covid‐19 pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood.

Data and method

To test the theoretical argument outlined in the previous chapter empirically, we rely on original survey data collected during the first peak of the coronavirus pandemic in spring 2020 with approximately 6,000 respondents in six European countries. Taking into account the situation at the onset of the crisis in early spring 2020, the survey includes respondents from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Although all countries selected were strongly affected by the first wave of the pandemic, they vary greatly in their governmental responses to it as well as their levels of infection. Whereas Italy, Spain and France were hard‐hit early and imposed strict lockdown measures, the United Kingdom issued such orders much later and experienced a continuing surge of infections. Germany and Switzerland also employed early lockdown measures, but mostly managed to contain the outbreak at comparatively low levels. Thus, the sample contains a substantial degree of variation in pandemic exposure. Further, national identity and the boundaries of national membership are a highly salient issue in each of the countries, while each has a very different history in this regard. Thus, results based on this dataset should not be limited to this specific set of countries in the European context. A detailed description of the survey is presented in Table OA1 in the Supporting Information Appendix.

For our dependent variable, conceptions of nationhood, we employ five widely used indicators referring to the importance that respondents place on being born in the respective country, having national ancestry and being a Christian (the main religion in all countries surveyed) for ethnic conceptions and respecting national political laws and institutions, and being able to speak the respective national language(s) for civic conceptions (Kunovich, Reference Kunovich2009; Reeskens & Hooghe, Reference Reeskens and Hooghe2010). In light of previous research on the relatively continuous nature of conceptions of nationhood between two extremes, we combined these five items into one variable. First, based on principal component analysis we distinguished between two factors that reflect earlier research for civic and ethnic conceptions, respectively (see Table OA2).Footnote 5 Second, we reversed the civic factor and combined it with the ethnic factor. Consequently, we use a continuous scale that runs from civic conceptions (low values) to ethnic conceptions (high values) with a mean value that locates each respondent between the two ideal points. This allows for obtaining a more fine‐grained picture that pays attention to individuals located in between since most people likely combine elements of both ideal types within themselves (Ariely, Reference Ariely2020; Reeskens & Hooghe, Reference Reeskens and Hooghe2010; Smith, Reference Smith1991).

We measure exposure to the Covid‐19 pandemic threat both at the individual and contextual level, thus focusing directly on perceptions of pandemic threat (Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014).Footnote 6 In line with previous research, we propose that pandemic threat not only originates from subjective threat experience, but also from pathogen stress within the larger region of an individual (Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill, Fincher, Workman, Reader and Barkow2020). As the pandemic disturbs societal life extensively in the personal environments and communities, it may well be that all individuals living in strongly affected areas, regardless of whether or not they report subjective threat from the virus, are facing pandemic threat. People may not be affected personally but still be exposed to pandemic threat and restrictions to contain the virus in their everyday lives. Thus, we expect that individuals living in areas strongly hit by the pandemic feel more threatened than individuals living in environments with low pandemic threat, irrespective of their personal pandemic‐related experiences. For individual‐level exposure to pandemic threat, we asked respondents ‘To what extent do you feel the coronavirus pandemic is a threat to you personally?’Footnote 7 For regional‐level prevalence of the pandemic in the 105 European regions across the six countries in our survey, we introduce two measures for the severity of the pandemic, that is, the number of cases and the number of Covid‐19‐related deaths, both per 100,000 inhabitants.Footnote 8 We gathered these data from the responsible statistical offices of the respective countries. As these regional‐level variables are vastly skewed towards lower values and given the potential for measurement error (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2009, p. 191), we took the logarithm. This approach should ensure that we can assess pandemic exposure thoroughly and that we are able to draw valid conclusions based on several modelling strategies.

To measure the role of emotions, we rely on the well‐known Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scale in its short version (Crawford & Henry, Reference Crawford and Henry2004; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988). The question reads as follows: ‘Now we would like to know how you feel. The following words describe different kinds of feelings and emotions. Read every word and mark the intensity on the scale. You have the choice between five gradations. Please indicate how you feel at the moment.’ For anger, we use (a) upset and (b) hostile. For fear we use (c) afraid and (d) nervous.Footnote 9 Although restrictions on the questionnaire size allow for only a limited number of items per latent construct, confirmatory factor analysis with maximum likelihood estimation supports the notion that fear and anger are correlated, yet distinct, emotional states (see Table OA3). The model fit for the confirmatory factor analysis implies a very good model fit with RMSEA < 0.08 and CFI > 0.9. Given that the strength of factors may vary between countries, we conducted a test for measurement invariance (see Table OA4), which supports full metric invariance that is crucial for a substantive interpretation of our results (cf. Davidov, Reference Davidov2009).

In accordance with previous research, we control for a range of socio‐demographic variables that likely affect conceptions of nationhood as well as exposure to the pandemic, such as age, gender, education, income situation, health, migration background and left‐right self‐placement (see Table OA5 for summary statistics and OA6 for exact item wording of the main variables). All variables were z‐standardized (mean = 0 and variance = 1) to make the respective coefficients comparable. In addition, we collected macro data for all regions to control for variation at the regional level that might affect the relationship between pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood. We use the share of elderly among the population, population density, unemployment rates and gross domestic product per capita as this set of macrolevel control variables contains a wide range of potentially influential predictors linked to the respective region.

To test the first hypothesis, we employ two linear regression models with country‐fixed effects and region‐clustered standard errors as our respondents are nested within the 105 regions across the six countries surveyed. Adjusting our estimates for country‐fixed effects allows controlling for unobserved heterogeneity between the countries. Besides this comparative approach, we conduct the microlevel analysis separately for each country surveyed to get a better understanding of the relationship that we are interested in. In addition to this individual‐level analysis, we conduct a macrolevel analysis using random‐intercept multilevel models for numbers of both cases and deaths at the level of the respective region.Footnote 10

The final step of our analysis consists of mediation analyses by means of path models to test hypothesis 2 that focuses on the mediating role of fear and anger (Preacher et al., Reference Preacher, Zyphur and Zhang2010; Rabe‐Hesketh et al., Reference Rabe‐Hesketh, Skrondal and Pickles2004). This set of models tests the mediation effect of fear and anger simultaneously as stipulated by previous research (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Valentino, Vasilopoulos and Foucault2019). These structural equation models are based on maximum likelihood estimations with regionally clustered standard errors and allow us to test whether fear and anger mediate the relationship and whether there are indirect effects of the exposure to pandemic threat on conceptions of nationhood. As with the first set of models, we conduct our mediation analyses using both individual‐ and regional‐level indicators for measuring pandemic threat exposure and split the individual‐level analysis for each of the six countries. When using regional‐level indicators, we rely on generalized structural equation models (Preacher et al., Reference Preacher, Zyphur and Zhang2010; Rabe‐Hesketh et al., Reference Rabe‐Hesketh, Skrondal and Pickles2004).

Empirical results

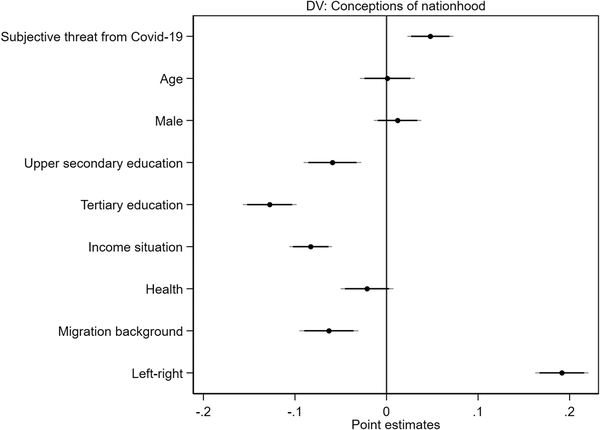

Figure 1 shows the results obtained from our first model looking at pandemic threat at the individual level (see Table OA7). The positive coefficient linking higher pandemic threat exposure to ethnic conceptions of nationhood supports our first hypothesis. Individuals perceiving Covid‐19 as a higher subjective threat are more likely to view national belonging as based on criteria such as having national ancestry and birth as well as adhering to the Christian religion, indicating an activation of the BIS and its disease‐avoidant norms and behaviours. Accordingly, respondents experiencing less subjective pandemic threat are more likely to hold civic conceptions of nationhood that draw on language and political values to define in‐group membership and allow for a higher permeability of national borders, which lends support to hypothesis 1. The relationships for our control variables equally point in the expected directions and are in line with previous studies. Right‐leaning, less educated individuals with a more adverse income situation or without a migration background are more likely to hold ethnic conceptions of nationhood.Footnote 11

Figure 1. Coefficient plot for individual‐level pandemic threat.

Note: Estimates are based on the full models as in Table OA7. Linear regression coefficients are displayed with confidence intervals at 90 per cent (black bars) and 95 per cent (light grey bars) levels.

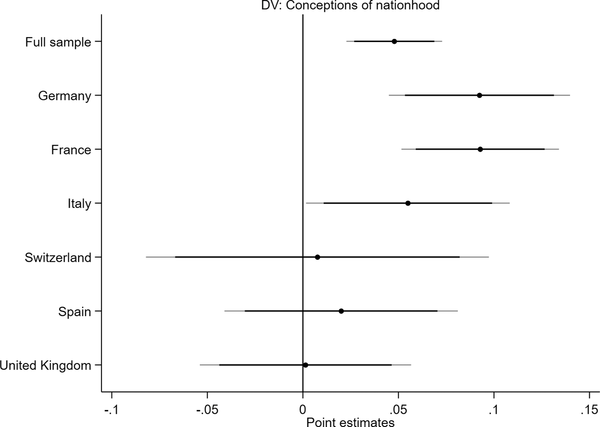

When investigating this relationship across countries (Figure 2), we find that it is significant in Germany, France and Italy. In Switzerland, Spain and the United Kingdom, the coefficients point in the expected direction but are not significant. Overall, looking at the countries individually supports the main finding from the comparative analysis, but it is also evident that it does not apply equally to the exclusion of other factors, which emphasizes the importance of investigating the nature of this relationship in more detail by means of mediation analysis to uncover underlying patterns.Footnote 12

Figure 2. Coefficient plot for individual‐level pandemic threat by country.

Note: Estimates are based on the full models as in Table OA11. Displayed are linear regression coefficients with confidence intervals at 90 per cent (black bars) and 95 per cent (light grey bars) levels.

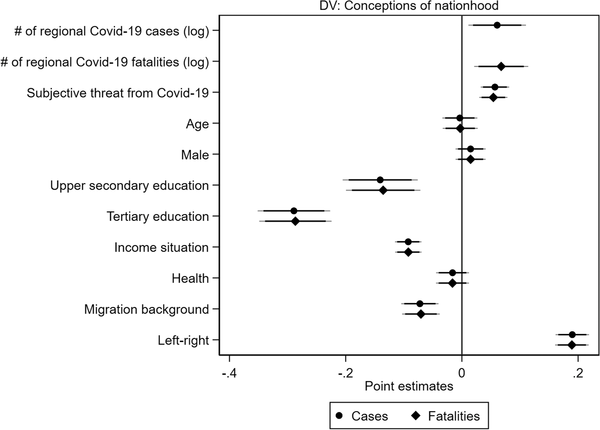

Figure 3 details the respective results for the multilevel analyses (see Table OA12). At the regional level, we observe that both higher numbers of Covid‐19 cases and Covid‐19‐related fatality rates are significant predictors of more ethnic‐based conceptions of nationhood. Individual threat levels remain robust and significant in both models. Including further macrolevel control variables (share of elderly among the population, population density, unemployment rates and gross domestic product per capita) does not change our main results (see Table OA13). To test for a potential sensitivity of our estimates to extreme cases or clusters, we estimated the same models using a jack‐knifing procedure, that is, we re‐estimated each model several times, removing all respondents from each region once to control for highly influential clusters. The results reflect those found in the base model (see Table OA14).

Figure 3. Coefficient plot for macrolevel pandemic threat.

Note: Estimates are based on the full models as in Table OA12. Displayed are linear regression coefficients with confidence intervals at 90 per cent (black bars) and 95 per cent (light grey bars) levels.

In a next step, we use mediation analysis to uncover whether the emotional states of fear and anger mediate the relationship between exposure to pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood. We test both micro‐ and macrolevel exposure to the virus as focusing only on the direct relationship between independent and dependent variables has been shown to hamper theory development and overlook potentially important indirect effects (Preacher et al., Reference Preacher, Zyphur and Zhang2010). Again, we start with exposure to pandemic threat at the individual level as the explanatory variable and test whether negative emotional responses mediate the relationship with conceptions of nationhood. Taking into account that both anger and fear likely occur simultaneously (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000), we analyze both emotions in a single, comprehensive model.

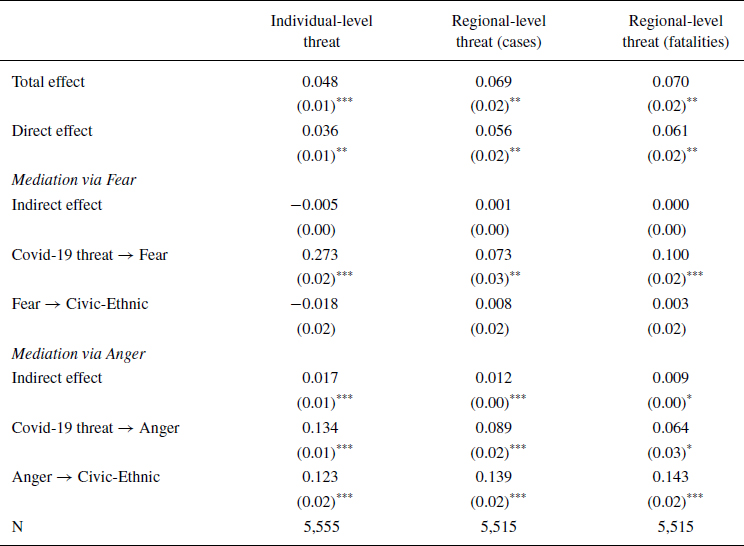

Table 1 shows the results obtained from our path models to uncover the hypothesized mediation effects. This mediation analysis reveals that the Covid‐19 pandemic threat is significantly related to both fear and anger at the individual and contextual levels. In other words, people who feel more threatened by the pandemic are likely to be both more angry and more fearful than those experiencing less pandemic threat. Yet, the results clearly show that these two emotions play decisively different roles. Whereas we do not find any mediation effect for fear, anger is a significant mediator linking pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood. These two findings hold regardless of how we measure pandemic threat.Footnote 13

Table 1. Combined path models for fear and anger with pandemic threat

Clustered standard errors (region) in parentheses.

+ p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

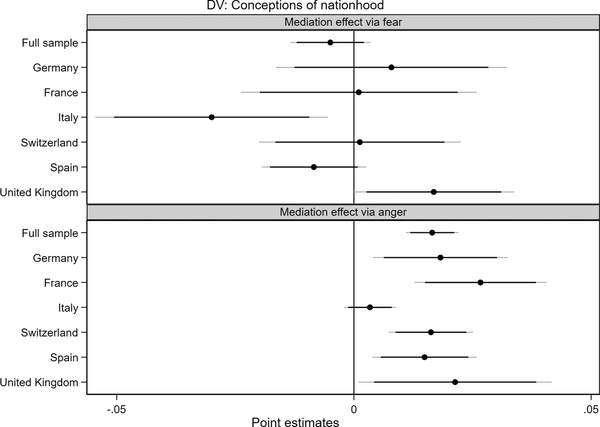

If we estimate these path models in the six countries separately, the results are largely substantiated. Anger significantly mediates the relationship between immediate pandemic threat and ethnic conceptions of nationhood in Germany, France, Switzerland, Spain and the United Kingdom (see Figure 4), whereas it is insignificant only in Italy. For fear, there are mostly insignificant and inconclusive results. We find a negative indirect effect only in Italy. Taken together, we find substantive evidence that emotional responses in the form of anger affect the relationship between exposure to pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood as argued in hypothesis 2. Fear, however, plays a decisively subordinate role in the context of pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood. This finding reflects recent advances in the role of emotions and the primacy of anger over fear in shaping individuals’ political attitudes and behaviours (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Valentino, Vasilopoulos and Foucault2019). These mediation analyses for the individual countries lend additional support to the hypothesized relationship between pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood, as this main relationship is significant in all but one country once emotional responses to threat are properly accounted for.

Figure 4. Coefficient plot for individual‐level mediation analysis by country.

Note: Full regression results available upon request. Displayed are linear regression coefficients with confidence intervals at 90 per cent (black bars) and 95 per cent (light grey bars) levels.

Taken together, our empirical analyses reveal a clear relationship between the Covid‐19 pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood. Individuals threatened by this infectious disease are more likely to hold ethnic views on national belonging that should be better suited for avoiding the contraction with novel pathogens than civic ones implying a greater permeability of national boundaries. These results support earlier findings that ‘intergroup bias is […] [affected] by features of the mind designed to enact approach avoidance mechanisms for negotiating adaptive intergroup relations in a way that would attenuate disease threat’ (Navarrete & Fessler, Reference Navarrete and Fessler2006, p. 279). Further, the mediation analyses show that certain emotional states are crucial to understand the relationship between the Covid‐19 pandemic and definitions on group membership thoroughly. Here, anger in particular is highly relevant in shaping the relationships between our main variables of interest. The threat of pandemic exposure activates anger, which in turn fosters ethnic conceptions of nationhood.

Conclusion

How does the Covid‐19 pandemic threat affect views on belonging to in‐ or out‐groups? In this paper, we evaluate whether pandemic threat experience is related to conceptions of nationhood among citizens in six Western European countries. Looking at national membership as today's most important form of group membership (Davidov, Reference Davidov2009; Greenfeld & Eastwood, Reference Greenfeld, Eastwood, Boix and Stokes2007), we suggest that ethnic conceptions of nationhood stressing the role of ‘thicker’ (Berg & Hjerm, Reference Berg and Hjerm2010, p. 393) criteria, like national ancestry, beyond the political sphere resonate well with the premise of the BIS‐hypothesis. Conversely, civic views on nationhood that deem respecting national political institutions and laws alongside being able to speak the national language as sufficient for being a full member of a nation should be more in conflict with attitudes and behaviours aiming to reduce the risk of contracting infectious diseases. The empirical analyses based on original survey data collected during the early phase of the pandemic support this argument. Individual experiences of pandemic threat as well as macrolevel data in the form of both case numbers and fatality rates predict conceptions of nationhood.

In addition, we follow AIT and add key insights regarding emotional responses in threatening situations to the behavioural immune system hypothesis. Focusing on fear and anger as crucial and distinct drivers of people's response to threat and uncertainty (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000, Reference Marcus, Valentino, Vasilopoulos and Foucault2019; Vasilopoulos et al., Reference Vasilopoulos, Marcus, Valentino and Foucault2019), we find that anger proves to be a crucial mediator of the relationship between pandemic threat exposure and conceptions of nationhood. Fear, in contrast, appears to play no mediating role if anger is properly accounted for. This crucial finding substantiates recent claims that both scholarly research and political commentators must be careful not to conflate these two emotions reflecting distinct cognitive systems operating largely independently of each other (cf. Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Valentino, Vasilopoulos and Foucault2019). Afraid individuals react very differently to pandemic threat perceptions than angry ones do. Anger drives individuals to confront an adversary and to protect the in‐group, reinforcing ethnic conceptions of nationhood as stipulated by the behavioural immune system hypothesis. Fear, however, more likely induces individuals to seek new perspectives and to go through a learning process (Albertson & Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015; Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Valentino, Vasilopoulos and Foucault2019; Vasilopoulos et al., Reference Vasilopoulos, Marcus, Valentino and Foucault2019). Consequently, people facing pandemic threat should assess the complexity of the pandemic and the transmission of the virus from a more differentiated point of view that does not lead to a withdrawal into more close‐knit social groups and a scapegoating of national out‐groups.

Yet, our approach also has limitations requiring further attention. Although our observational data gives important, first‐hand evidence on pandemic threat regarding both the individual and contextual levels, we cannot make causal claims as compared to experimental settings in laboratory studies or time‐series analyses. While there exists substantial causal evidence that the activation of the BIS has an effect on xenophobia (Aarøe et al., Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017; Faulkner et al., Reference Faulkner, Schaller, Park and Duncan2004) or in‐group favouritism (Navarrete & Fessler, Reference Navarrete and Fessler2006), similar studies have not yet been conducted for conceptions of nationhood. We argue that it appears unlikely that people are more likely to contract Covid‐19 because they hold more ethnic conceptions of nationhood. Individuals convinced that only those born and raised in their respective countries are true members of their in‐group will have comparably closed social environments that are less open towards newcomers. Consequently, such individuals should be less likely to become infected with contagious diseases from out‐groups. Evidence that many infections happened among in‐group members (family, friends, co‐workers, religious communities, associations or sports clubs) indeed supports the main tenets of the BIS hypothesis (Tybur et al., Reference Tybur, Lieberman, Fan, Kupfer and Vries2020). If individuals are particularly careful in their dealings with out‐group members, they may also systematically underestimate the threat of infections emanating from members of their own in‐group since evolutionary developed heuristics lead to misperceptions of infectiousness. While this pattern might call into question the success of the BIS as a means of ensuring protection from a contagious virus like SARS‐CoV‐2 in modern, large‐scale societies, we provide substantive evidence that it plays a decisive role in shaping people's attitudes and behaviours, nonetheless. In sum, we argue that providing first‐hand, real‐world data on pandemic threat is pivotal to complement previous studies that have provided substantive evidence on the issue of causality (see also Murray & Schaller, Reference Murray and Schaller2016; Tybur et al., Reference Tybur, Frankenhuis and Pollet2014).

Finally, the countries selected for our original survey do not cover all possible contextual factors that may drive the relationship under study. This is particularly relevant for certain parts of the world where ethnic, religious or regional identities are much more important than national ones. However, our dataset provides insight into cases with substantial variation, which certainly allows for drawing conclusions more broadly applicable than the six countries studied in this paper.

In conclusion, our results have far‐reaching implications for a better understanding of group membership in modern societies. We show how exposure to pandemic threat relates to belonging to the national in‐group, thereby providing the first evidence on the validity of the BIS in the context of a novel, yet highly salient, pandemic among citizens, for whom parasite stress and infectious diseases arguably played a minor role for many decades. Our findings corroborate the claim that liberal, open societies – which all surveyed countries claim to be – must combat infectious diseases not only as a matter of public health, but also to ensure their own survival (cf. Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill, Fincher, Workman, Reader and Barkow2020, p. 175). This is even more crucial if the boundaries of social groups become less permeable in the face of pandemic threat and should be equally applicable to other societal groups, where (non‐)membership contributes to individuals’ social identities beyond national belonging. If belonging to in‐ and out‐groups in general becomes more static, the very foundations of liberal and pluralistic societies are shaken substantially and even democratic governance itself may come under pressure (Erhardt et al., Reference Erhardt, Wamsler and Freitag2021). Given that globalization fosters the presence of diverse ethnic groups across the globe, a continued salience of infectious diseases likely becomes a serious obstacle to societal acceptance of people with different backgrounds (Aarøe et al., Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017). Concern about pathogen prevalence may thus inhibit inclusive societies and exchange across different ethnic groups severely if the mere presence of physically and culturally distinct out‐group members may be seen as threatening due to the prevalence of infectious diseases like Covid‐19.

The importance of emotions in general and of anger in particular, as shown by the uncovered mediation effects, further stresses that distinct affective responses to threat and uncertainty like fear and anger must not be used interchangeably as they vary decisively in their potential to shape attitudes and behaviours with regard to a large variety of social sciences concepts (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Valentino, Vasilopoulos and Foucault2019). Correspondingly, political communication and policy design should always consider the emotional reactions invoked among citizens to avoid backfiring if citizens react with fear or anger to them (cf. Albertson & Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015). This is all the more important given the increasing consensus among leading epidemiologists that globalization may continue to accelerate both the frequency and severity of pandemics over time. Future research might now look for data to gain an even deeper understanding of the role of (other) emotions and to assess the role of the Coronavirus pandemic in shaping other relevant sets of attitudes, such as norm‐conformity, authoritarianism or social conservatism (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Fincher and Walasek2016; Thornhill & Fincher, Reference Thornhill and Fincher2014). Another promising avenue for future research will be to examine the role of the Coronavirus pandemic in shaping within‐country outgroup‐hostility (e.g., rich vs. poor, ethnic majority vs. ethnic minority) or to delve deeper into aspects of national identity not covered by conceptions of nationhood, such as nationalist attitudes or ethnocentrism. Finally, researchers might theorize and study, which contextual factors might play a prominent role in the context of pandemic threat and conceptions of nationhood to explain differences across countries in more detail. Overall, our study gives vital insight into the extent to which the Covid‐19 pandemic threat structures feelings of national belonging and initiates avenues for future research on the social and political consequences of the crisis.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank several people who contributed to this study. We are grateful to Michael Wicki, Sara Gomm, Oriane Sarrasin, Thomas Kessler as well as all participants of the respective workshops at the Annual Conference of the Swiss Political Science Association 2021 and the Scientific Online Meeting of the German Political Psychology Network 2021, whose invaluable feedback provided us with excellent opportunities to improve our paper.

Open access funding provided by Universitat Bern.

Funding Statement

This article was written as part of the research project “The Politics of Public Health Threat” that is financially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) (grant no. 100017_204507) and the Berne University Research Foundation (grant no. 25/2020).

Conflicts Of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix