Introduction

Women’s experiences when reaching high-profile political positions differ substantially from those of men. A typical example illustrating these biases is the German politician Annalena Baerbock (Greens). She ran for Chancellor in the 2021 federal elections, securing the nomination after a close contest with Robert Habeck. Misogynist attacks from the media, competing parties, and even from party members accompanied her election campaign (Abels et al. Reference Abels, Ahrens, Jenichen and Och2022; Diekmann Reference Diekmann, Fuchs and Motzkau2023). The Green party’s performance in the election was considered a failure irrespective of substantially higher vote shares compared to previous elections. As a result, Habeck led the coalition negotiations with the Social Democrats and the Liberal Party rather than Baerbock. During government formation, Baerbock still shattered a glass ceiling by becoming Germany’s first woman foreign minister. After she entered this highly prestigious position, she was one of the government ministers receiving the harshest criticism by opposition members. In particular, her travel arrangements resulted in substantial negative news coverage portraying her as lacking expertise and authority (Krappitz Reference Krappitz2024; Röhlig Reference Röhlig2024). She also struggled to gather support within her own party for some of her policy endeavors (ZDF heute 2024). While this example illustrates different standards for and experiences of women and men politicians, systematic comparative knowledge on how the working conditions of ministers are gendered is still missing. The present study enhances the understanding of the way women experience gender bias even after they have entered the most prestigious political posts by turning to the role of ministers’ gender for legislative oversight. Legislative oversight is a key element of the relationship between parliament and government in parliamentary democracies. Scholarly work shows that institutional powers, party competition, and the characteristics of MPs (members of parliament) shape legislative oversight (Akbik and Migliorati Reference Akbik and Migliorati2022; Celis Reference Celis2006; De Vet and Devroe Reference De Vet and Devroe2023b; Friedberg Reference Friedberg2011; Höhmann and Krauss Reference Höhmann and Krauss2022; Höhmann and Sieberer Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020; Martin Reference Martin2011; Pelizzo and Stapenhurst Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2013; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2000). However, these studies only capture part of the picture since they do not consider in what way the gender of the minister shapes how tightly MPs oversee their work. We thus address the questions of whether and why MPs oversee women and men ministers differently.

We argue that parliamentarians oversee women ministers more tightly than men ministers. This expectation is based on two causal mechanisms: differences in the competence MPs attribute to men and women ministers and differences in the trust MPs place in them. First, MPs perceive men ministers as more competent than women because they associate them with traits valued in political actors. MPs assume men ministers to be more capable due to stereotypical beliefs about gender roles. Second, parliamentarians tend to regard men ministers as more trustworthy – as reliable partners who can be confided in (Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Levi and Stoker Reference Levi and Stoker2000). This perception emerges partly because men have historically dominated government and thus appear more accessible, and partly because the male majority in parliaments fosters trust in those who share their characteristics (Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2018; Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2006; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015). As a result of the gendered differences in perceived competence and trust, parliamentarians scrutinize women ministers more closely than men.

We study the relationship between ministers’ gender and legislative oversight in five European parliamentary democracies since 1990, using original data for parliamentary questions. The selected countries – Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, and Spain – offer substantial variation in women’s parliamentary representation, the complexity of the political situation in parliament, and dynamics of cabinet formation, enhancing the generalizability of our findings to Western parliamentary democracies. To examine the impact of ministers’ gender on MPs’ oversight activities, we analyze change in the number of written and oral questions submitted by MPs to specific ministries if, within the same cabinet, a man replaces a woman as minister or vice versa. This research design has two key advantages. First, questions are an important formal oversight tool that MPs can use independently (Maricut-Akbik Reference Maricut-Akbik2021), allowing us to trace gendered patterns in MPs’ oversight activities. Second, by focusing on ministerial changes within a cabinet, we control for factors such as party constellations and portfolio salience, isolating the effect of ministers’ characteristics on oversight intensity. Our empirical analysis demonstrates that MPs oversee women ministers more strictly than their male counterparts. In four of the five countries, MPs submit more questions to ministries while women are in charge compared to the time their man predecessors or successors were in office. In Belgium, gender bias in legislative oversight appears only under specific conditions, such as when ministers hold highly prestigious portfolios and for women replacement ministers. These patterns persist regardless of differences in ministers’ political experience. In addition to the quantitative analysis, we draw on semi-structured interviews on specific cases of ministerial replacements with thirty-two MPs to support our claim that gendered legislative oversight stems from differences in how MPs perceive the competency and trustworthiness of men and women ministers. The interviews suggest that MPs perceive the men ministers as more competent and trustworthy than the women ministers and that these assessments directly influence their oversight behavior, as they scrutinize more closely those ministers they perceive as less competent and trustworthy.

Our findings contribute to the literature on parliamentary democracy and women in politics. This study is the first to demonstrate that ministers’ individual characteristics – such as gender, and potentially also ethnicity, social status, or age – shape parliamentary scrutiny. As MPs subject women ministers to stricter oversight, they risk neglecting shortcomings in the work of men ministers. Since legislative oversight is essential for government accountability to the public (Pelizzo and Stapenhurst Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2013), this imbalance weakens parliamentary democracy as a whole. From a gender and politics perspective, our findings highlight the unequal working conditions women face in the highest political offices. Beyond barriers to entering and advancing to influential party and government positions (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2016; Kroeber and Hüffelmann Reference Kroeber and Hüffelmann2022; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012), women who reach these posts are vulnerable to failure, standing on ‘quick sand’ (Aldrich and Somer-Topcu Reference Aldrich and Somer-Topcu2025: 53). Prior research has demonstrated that women are set up to fail when appointed during crises (see, for example, Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O’Brien2024; O’Neill et al. Reference O’Neill, Pruysers and Stewart2019). This article sheds light on why women fail even in normal times by showing that they must devote disproportionate time and resources to responding to parliamentary scrutiny. This burden reduces ministers’ ability to set policy agendas (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Müller, Angelova and Strobl2021), develop policy proposals, and engage with the media. Furthermore, increased oversight heightens women’s exposure to parliamentary and public criticism, as even under the least stringent forms of questioning, they must disclose more information than men ministers. By illuminating these gendered oversight conditions, our study enhances the understanding of women’s performance in high-profile political office.

Literature Explaining Variation in Legislative Oversight

Legislative oversight refers to parliamentarians’ right and duty to scrutinize government actions to ensure they serve the interest of the people. By gathering information about policy initiatives, requesting modifications, or applying sanctions, MPs wield a powerful tool to hold governments and their ministers accountable (Griglio Reference Griglio2020; Pelizzo and Stapenhurst Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2013). Research on the relationship between ministers and MPs in parliamentary democracies is largely grounded in principal–agent theory (Griglio Reference Griglio2020; Miller Reference Miller2005; Strøm Reference Strøm and Döring1995). Under this framework, the people (as ultimate principal) delegate the power to govern to the executive (as ultimate agent) via the legislature (which acts as both agent of the people and principal of the executive). Political parties and their leaders act as intermediaries, linking citizens to both parliament and executive (Müller Reference Müller2000; Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2014; Strøm Reference Strøm and Döring1995). Party and institutional gatekeepers select, hold accountable, and deselect ministers. As principals, they aim to minimize appointing underqualified or misaligned agents through pre-selection screening (Dowding and Dumont Reference Dowding and Dumont2014; Lupia Reference Lupia, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2003). Once in office, oversight mechanisms ensure continued accountability (Kiewiet and McCubbins, Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991; Strøm Reference Strøm, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2003; Weingast and Moran Reference Weingast and Moran1983). Legislative oversight thus involves continuous scrutiny and evaluation of all government policies, actions, and performance. Individual MPs have far-reaching rights in this process, including oral and written questions to the government members and requests for legislative action (Mattson and Strøm Reference Mattson, Strøm and Döring1995; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2000). Existing research highlights institutional designs, party competition, and MPs’ characteristics as factors influencing variations in legislative oversight.

Scholars have extensively examined how institutional factors such as parliamentary oversight rights empower or restrict MPs’ ability to oversee the executive effectively (Friedberg Reference Friedberg2011; Pelizzo and Stapenhurst Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2013; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2000). Legislators can monitor executive action through three primary mechanisms: extracting information about government activities, overseeing the implementation of laws, and compelling the government to justify its decisions (Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2000). Oversight serves as a tool for policy control, either by shaping policy ideas or influencing policy implementation (Griglio Reference Griglio2020). The effectiveness of oversight is further determined by institutional design, which can either encourage collaboration between parliament and government or reinforce parliamentary control over the executive – depending on whether the system favors a soft or hard approach to legislative oversight (Griglio Reference Griglio2020).

Party competition also influences how MPs utilize oversight tools. Opposition members typically conduct oversight in a highly visible manner, leveraging formal rights granted by constitutions and laws. By contrast, governing party MPs often rely on informal, less transparent mechanisms that operate behind closed doors (for a discussion of coalition meetings see, for example, Miller and Müller Reference Miller and Müller2010). However, in coalition governments, governing party MPs also use formal oversight tools to monitor ministers from their coalition partners (Höhmann and Krauss Reference Höhmann and Krauss2022; Höhmann and Sieberer Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020; Martin and Whitaker Reference Martin and Whitaker2019).

MPs’ individual characteristics also influence how they exercise oversight. Research shows that legislators’ policy priorities shape their scrutiny of ministers in specific portfolios. These priorities often stem from electoral pressure (Höhmann Reference Höhmann2019), party control (De Vet and Devroe Reference De Vet and Devroe2023b), or social background factors such as ethnicity (Minta Reference Minta2009), nationality (Akbik and Migliorati Reference Akbik and Migliorati2022), and gender (Celis Reference Celis2006). Additionally, MPs’ gender influences how they engage in their institutional roles, both in opposition and government. It shapes their use of formal oversight tools (Kroeber and Krauss Reference Kroeber and Krauss2023) and determines the extent to which opposition MPs prioritize party-aligned issues in their parliamentary questioning (de Vet and Devroe Reference de Vet and Devroe2023a).

While these research strands explain some variation in oversight processes, they overlook a key actor in the process – the minister. A think piece by Kroeber and Dingler (Reference Kroeber and Dingler2023) highlights this gap by examining how crises influence gendered dynamics of legislative oversight. They argue that the gender of both ministers and MPs shapes their mutual expectations, interactions, and the extent to which crises create opportunities for these dynamics to change. Building on this work, the present study advances the field by systematically linking ministers’ gender to MPs’ oversight activities. It is the first to propose consolidated causal mechanisms explaining this connection and to provide in-depth empirical evidence testing these relationships. The study thus moves gendered legislative oversight from an abstract concept to an empirically grounded reality.

Literature on Unequal Conditions for Men and Women Political Leaders

This article connects the study of legislative oversight with research on the unequal conditions faced by women and men in high-profile political offices. Even in the twenty-first century, women remain less likely than men to become party leaders (Aldrich and Somer-Topcu Reference Aldrich and Somer-Topcu2025, O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015), heads of government (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai, Alexander, Bolzendahl and Jalalzai2018), or ministers (see, for example, Claveria Reference Claveria2014; Goddard Reference Goddard2021; Kroeber and Hüffelmann Reference Kroeber and Hüffelmann2022; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012). Three recurring contexts stand out in the literature as situations in which inequality in women’s access to these offices emerges.

First, women are more likely to enter high-profile positions during a crisis than during ordinary times (see, for example, Morgenroth et al. Reference Morgenroth, Kirby, Ryan and Sudkämper2020; Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Haslam, Morgenroth, Rink, Stoker and Peters2016), as men tend to avoid taking over new responsibilities when the risk of failure is high. Second, gender progressive attitudes within parties and societies increase women’s chances for reaching top political offices (Aldrich and Somer-Topcu Reference Aldrich and Somer-Topcu2025; Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Dingler and Helms Reference Dingler and Helms2023; Goddard Reference Goddard2019).Footnote 1, Footnote 2 Third, the nature of the tasks associated with a leadership role can shape women’s access. In ministerial selection, for instance, women are disproportionally appointed to portfolios linked to ‘women’s issues’ such as family, education, or health, and less often to ‘masculine’ areas such as security, finance, or the economy (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009; Goddard Reference Goddard2019). In line with this pattern, the ‘glass wall’ argument more broadly suggests that women leaders are often steered towards roles with administrative or supportive responsibilities, while men are more likely to occupy strategic or high-prestige positions (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Kerr and Reid1999; Sneed Reference Sneed2007).

Substantially less is known about how working conditions differ once men and women have entered office, but descriptive evidence suggests distinct career trajectories. Some studies find that women’s tenure in office is shorter than men’s (Bright et al. Reference Bright, Döring and Little2015; Saaka Reference Saaka2025), though others show that this effect is context-dependent (O’Neill et al. Reference O’Neill, Pruysers and Stewart2019; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015) or absent altogether (Aldrich and Somer-Topcu Reference Aldrich and Somer-Topcu2025; Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O’Brien2024). Within cabinet, women are less likely to be promoted to prestigious portfolios (Curtin et al. Reference Curtin, Kerby and Dowding2023) and often remain longer in less prestigious roles before advancing than men (Kroeber and Hüffelmann Reference Kroeber and Hüffelmann2022). The literature interprets this pattern as an indication that women in high-profile positions are held to higher standards than men. Experimental evidence on ministers supports this claim: in a survey experiment with German and Austrian MPs, Dingler and Kroeber (Reference Dingler and Kroeber2022) find that, when gender stereotypes are activated, right-wing MPs rate women ministers less competent, while left-wing MPs rate them more favorably. Furthermore, higher standards also appear in the aftermath of electoral losses, where women party leaders are more likely to leave office than their men counterparts (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015, Aldrich and Somer-Topcu Reference Aldrich and Somer-Topcu2025).

Despite these important contributions, we still know little about the mechanisms that produce unequal career paths for men and women. Legislative oversight provides a valuable perspective for understanding these dynamics. Through oversight, MPs ask for transparency, justifications of decisions, policy change, or even sanctions (Maricut-Akbik Reference Maricut-Akbik2021). These demands are potential stumbling blocks that threaten a minister’s tenure or career prospects. Heightened oversight also reduces ministers’ capacity to set policy agendas (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Müller, Angelova and Strobl2021), develop new proposals, or engage with the media. Understanding gendered patterns of legislative oversight promises to enhance our understanding of why women face shorter political careers and more limited access to prestigious posts than men.

Theory: Gender and Oversight

We argue that MPs’ execution of their oversight function is shaped by ministers’ gender. This argument builds on existing scholarship demonstrating that gender significantly affects how politicians evaluate political actors (see, for example, Eagly and Carli Reference Eagly and Carli2003; Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Eagly et al. Reference Eagly, Nater, Miller, Kaufmann and Sczesny2020).Footnote 3 We ground our expectation of stricter oversight of women ministers in two causal mechanisms that serve to develop the main hypothesis of this paper: (1) differences in the competence MPs attribute to men and women ministers and (2) differences in the trust MPs place in them.

MPs tend to perceive men ministers as more competent than their women counterparts, a bias rooted in gender stereotypes about leadership skill and socially acceptable behavior. First, the traits associated with effective political leadership align with traditionally masculine characteristics, reinforcing the perception that governing is a male domain (Bruckmüller et al Reference Bruckmüller, Ryan, Rink and Haslam2014; Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt Reference Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt2001; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Butterfield and Parent2002; Schein and Mueller Reference Schein and Mueller1992). These masculine traits, such as assertiveness, confidence, competitiveness, or ambition, correlate with the competence individuals ascribe to politicians (Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt Reference Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt2001; Eagly et al. Reference Eagly, Nater, Miller, Kaufmann and Sczesny2020; Rosenwasser and Dean Reference Rosenwasser and Dean1989; Thomas Reference Thomas1994). By contrast, women are often ascribed traits such as affection, helpfulness, kindness, and sympathy, which do not align with traditional notions of political efficacy. Bjarnegård (Reference Bjarnegård2018) refers to this phenomenon as ‘patriarchal resources’, a set of attributes that enhance the perceived competence of men politicians while remaining largely inaccessible to women. Second, even when women exhibit traditionally masculine traits, they are still evaluated less favorably than men according to role congruity theory (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). Women who deviate from expected feminine behavior are often viewed as behaving inappropriately, resulting in negative evaluations (Heilman and Okimoto Reference Heilman and Okimoto2007; Rudman et al. Reference Rudman, Moss-Racusin, Phelan and Nauts2012). Consequently, women in high-ranking political and corporate roles frequently encounter skepticism about their leadership ability (Biernat and Fuegen Reference Biernat and Fuegen2001; Eagly and Carli Reference Eagly and Carli2003; Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt Reference Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt2001). Applying these insights to our study, we expect heightened oversight of women in ministerial positions, because MPs perceive women ministers as less competent than men ministers.

Beyond competence perception, MPs regard men ministers as more trustworthy than women – that is, they see them as reliable partners who can be confided in (see Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019, Levi and Stoker Reference Levi and Stoker2000). Trust is inherently relational (Levi and Stoker Reference Levi and Stoker2000). It develops from personal and partisan networks, in which members view each other as dependable allies who keep confidence (see Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019). As a result, trust shapes patterns of interaction and co-operation (see Levi and Stoker Reference Levi and Stoker2000 for a discussion), and, as we argue, legislative control. Two factors contribute to a systematic trust gap disadvantaging women ministers. First, because men have historically dominated government, they possess denser and more durable political networks. Women, by contrast, still seen as newcomers, are perceived as less predictable or reliable (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2006; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015). Second, men’s numerical dominance in parliaments reinforces homosocial dynamics. Shared ascribed characteristics foster interaction and loyalty privileging men ministers as trusted partners (Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2018). Additionally, shared identities shape perceptions of approachability and accessibility (Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2018), which further enhance trust. Consequently, MPs in general – and men MPs in particular – are more likely to trust men ministers than women ministers. Since lower trust leads to heightened attentiveness, closer monitoring, and less co-operative behavior (Levi and Stoker Reference Levi and Stoker2000), we expect that women ministers are more frequently subjected to rigorous oversight than their men counterparts.

We expect differences in MPs’ perceptions of ministers’ competence and trustworthiness to produce the following overarching effect:

HYPOTHESIS 1: Parliamentarians oversee ministerial activities more tightly if the minister is a woman compared to a man.

Research Design

To test these propositions, we examine how MPs change their oversight behavior when a woman minister is replaced by a man minister or vice versa within a cabinet.Footnote 4 We analyze five European democracies between 1990 and 2022 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, and Spain). These countries are all parliamentary systems with long-established democratic procedures, ensuring a comparable context. However, they differ in key aspects, notably women’s representation in parliament (ranging between averages of 27.5 per cent in Belgium and 37.9 per cent in Denmark), the numbers of parliamentary parties (on average between 4.57 in Austria and 12.6 in Denmark), and the size of the governing majority (on average between 38.9 per cent in Denmark and 62.6 per cent in Germany). Additionally, the frequency of MPs’ oversight activities varies across cases, with the average number of questions per ministry per term ranging between 391.4 in Austria and 1,329.4 in Germany (for a detailed comparison of the countries see Table A1.1 in Appendix 1). This variation enhances the generalizability of our findings to Western industrial democracies.

We focus on ministerial replacements and compare MPs’ oversight of a man and woman minister holding the same portfolio within the same cabinet (for an overview, see Table A1.2 in Appendix 1). This strategy minimizes the influence of confounding factors such as portfolio salience, party ideology, or government–opposition constellation, allowing us to isolate the impact of ministers’ gender. We contend that the patterns observed in our sample of replacements are indicative of gendered oversight dynamics in ministerial appointments more broadly for three reasons. First, replacements constitute a substantial share of all appointments; specifically, our sample includes 36.5 per cent of all women ministers appointed to the cabinets under study. Second, most replacements occur for reasons exogenous to legislative oversight. These include larger cabinet reshuffles where a minister takes over a new post within cabinet (37 per cent), career changes such as transitions to regional government (21 per cent), or health-related reasons (1 per cent). Performance-related resignations or deselections account for 32 per cent, while only 9 per cent of replacements follow scandals or portfolio crises (see Table A1.3 in the Appendix 1).Footnote 5 Third, additional tests show that a replacement itself does not generate distinctive oversight dynamics. Patterns of oversight are similar for original and successor ministers, suggesting that our findings are not driven by the replacement event (see section ‘Testing sampling bias’ in Appendix 4).

For the analysis, we restrict our observations to ministerial changes where both the man and woman minister served for more than six months. This approach ensures that MPs have sufficient time to evaluate a minister’s performance and that parliamentary processes normalize after a ministerial change.

The data is structured as monthly panel data, with each observation representing a ministry in a given month (N = 3,064). These observations stem from eighty-one cases in which a man minister was replaced by a woman or vice versa across the five countries.Footnote 6

Dependent Variable

We use the number of questions posed by MPs to ministers as an indicator of the intensity of legislative oversight. As previous research argues, MPs may address questions to any minister on virtually any issues (Höhmann Reference Höhmann2019; Kroeber and Krauss Reference Kroeber and Krauss2023; Martin Reference Martin2011; Saalfeld and Bischof Reference Saalfeld and Bischof2013).Footnote 7 Unlike other oversight tools, such as requests or proposals, which require co-ordination with others, MPs can submit questions individually and in large numbers.Footnote 8 , Footnote 9 Additionally, while minor requests are primarily employed by opposition MPs, questions are also used by government MPs, particularly to monitor coalition partners (Höhmann and Krauss Reference Höhmann and Krauss2022; Höhmann and Sieberer Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020; Martin and Whitaker Reference Martin and Whitaker2019).

We collected original data on all written and oral questions submitted to the governments across the five countries. For Spain, we include only oral questions, as MPs cannot pose written questions directly to a specific minister but only to the government as a collective body. Consequently, it is impossible to determine with certainty which minister an MP intended to address. We draw on existing data of questions from Remschel and Kroeber (Reference Remschel and Kroeber2022) for Germany (up to 2017) and ParlSpeech V2 data set by Rauh and Schwalbach (Reference Rauh and Schwalbach2020) for Spain (1998–2018). For all other electoral periods in these countries, as well as Austria, Belgium, and Denmark, we scraped parliamentary web archives to compile the data.

We use the number of questions submitted to a ministry per month as an indicator for the tightness of MPs’ oversight. This measure is based on the assumption that a higher volume of questions reflects greater scrutiny of the minister in charge. We construct this indicator by counting the total number of questions directed to each ministry per month.Footnote 10

On average, ministers receive 7.28 questions per month from MPs, with values ranging from 0 to 139 questions and a standard deviation of 15.33. In 48.40 per cent of the months observed, ministries receive no questions. Variation across countries is substantial, with Spain recording the lowest average (1.12 oral questions per ministry per month), followed by Denmark (5.41 oral and written questions), Austria (9.24), Belgium (12.41), and Germany (23.08). This variation reflects both institutional differences and distinct oversight cultures, suggesting that legislative oversight operates under slightly different logic across the cases studied. We therefore model the data separately per country instead of preparing a pooled model.

Figure 1 visualizes the aggregated time trend in the number of questions by country. The data reveals opposing time trends across countries. In Austria, Germany, and Denmark, the number of questions submitted to a ministry is highest early in the electoral cycle and declines over time. Belgium, by contrast, exhibits the opposite pattern, while Spain shows no clear time trend. Overall, this descriptive evidence underscores the importance of accounting for context-specific variation in the number of questions.

Figure 1. Average number of questions per month over government duration by country.

Note: For comparability, the figure displays only forty-eight months after the first minister takes office, corresponding to the standard government duration, although some ministers might serve longer.

Independent Variable

The independent variable is ministers’ sex. We collected data from various internet sources, including mostly parliamentary websites, but also media reports. The variable is coded as binary, with ‘1’ indicating men ministers and ‘2’ indicating women ministers.

Confounders

Since we compare MPs’ oversight activities towards men and women ministers holding the same portfolio within the same legislative period and government, we include only confounders that vary with the minister.

We introduce a set of variables to capture relevant differences in the political experience of men and women ministers. MPs are likely to place greater trust in ministers with substantial political experience, perceiving them as more capable. As a result, experienced ministers may face less tight oversight. At the same time, research suggests that women often have more experience than men when entering high-profile political posts (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013; Müller-Rommel and Vercesi Reference Müller-Rommel and Vercesi2017; Verge and Astudillo Reference Verge and Astudillo2019). Thus, gender differences in experience may counterbalance differences in legislative oversight. To account for these dynamics, we include three confounders for political experience: first, legislative experience is measured by the number of years a minister served as an MP. A squared term is included in the models, as the benefits of additional parliamentary tenure may diminish over time. To avoid multicollinearity, this variable is centered around its mean. Second, executive experience is captured through the number of years a minister previously served in government before assuming the position under study. This variable is also mean-centered, with a squared term included. Third, we include a variable for portfolio-specific experience, indicating the years a minister previously served in the same portfolio. Data for these variables were collected from various online sources, primarily government and parliamentary websites, supplemented by the personal websites of former ministers.

Empirical Analysis

Bivariate Evidence

At the aggregate level, women ministers receive slightly more questions than their men colleagues. On average, a woman minister received 0.12 more questions than the man she replaced or was replaced by. More specifically, among the eighty-one replacements, thirty cases show fewer average monthly questions for women ministers, ten cases display no difference, and forty-one cases include higher average numbers of questions for women compared to men ministers. This pattern occurs consistently across all five countries, with women ministers receiving more questions in a slight majority of cases.

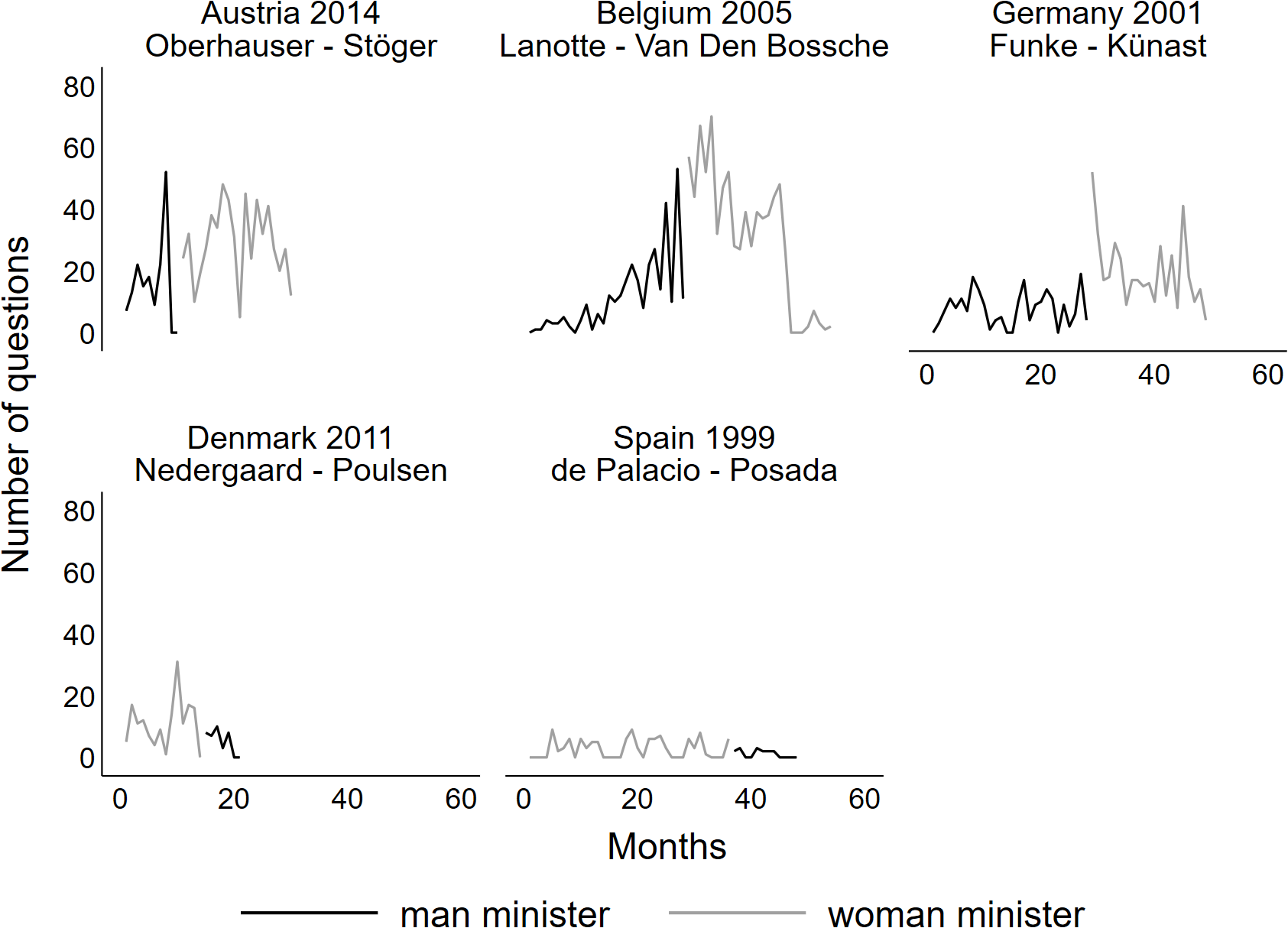

Figure 2 illustrates these descriptive trends by depicting the number of questions received by specific women and men ministers involved in a replacement. These illustrative cases, selected as a convenience sample, highlight the pattern in which women receive more questions than men. Figures covering all cases are provided in Appendix 2. The selected examples reflect the diverse contexts in which gender biased oversight occurs. The cases include ministerial replacements involving both left- and right-wing parties and span across three decades. The reasons for these replacements vary, including scandals, personal motives, and career changes.Footnote 11 The subsequent section shows that gendered legislative oversight also becomes visible in a multivariate model.

Figure 2. Monthly number of questions received by selected men and women ministers.

Multivariate Evidence

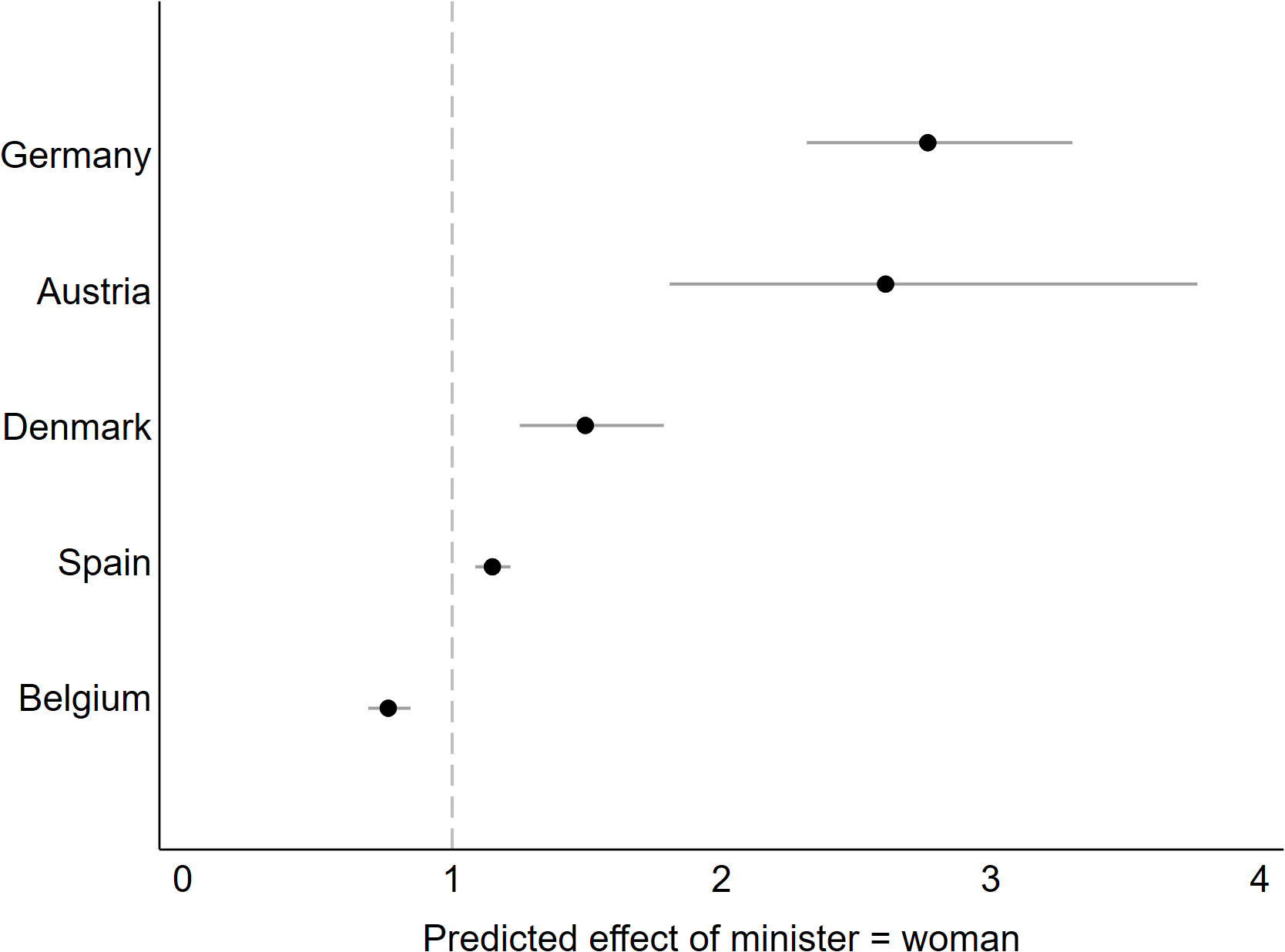

We estimate separate models for each of the five countries to allow for country-specific characteristics. We estimate Poisson regression models for panel data to model the data structure and the nature of the dependent variable as a count variable without overdispersion. The models include fixed effects to control for unobserved heterogeneity at the level of ministerial replacements. This ensures the remaining variance analyzed reflects within-replacement differences, such as the effect of the minister’s sex and variation in political experience.Footnote 12 Additionally, we introduce a time trend to capture systematic shifts in the number of monthly questions posed to a ministry. Figure 3 visualizes the effects of ministers’ sex across country models, while the full models are displayed in Table A3.1 in Appendix 3.

The multivariate results largely confirm that women ministers receive more questions from MPs than their men predecessors and successors. Four of the five country models show positive effects for women ministers. The predicted gender gap in questions ranges from 15 per cent in Denmark and 49 per cent in Spain to over 160 per cent in Austria and up to 177 per cent in Germany. Only the Belgian model deviates from this pattern, showing a 35.27 per cent decrease in the number of questions received by women compared to men ministers.

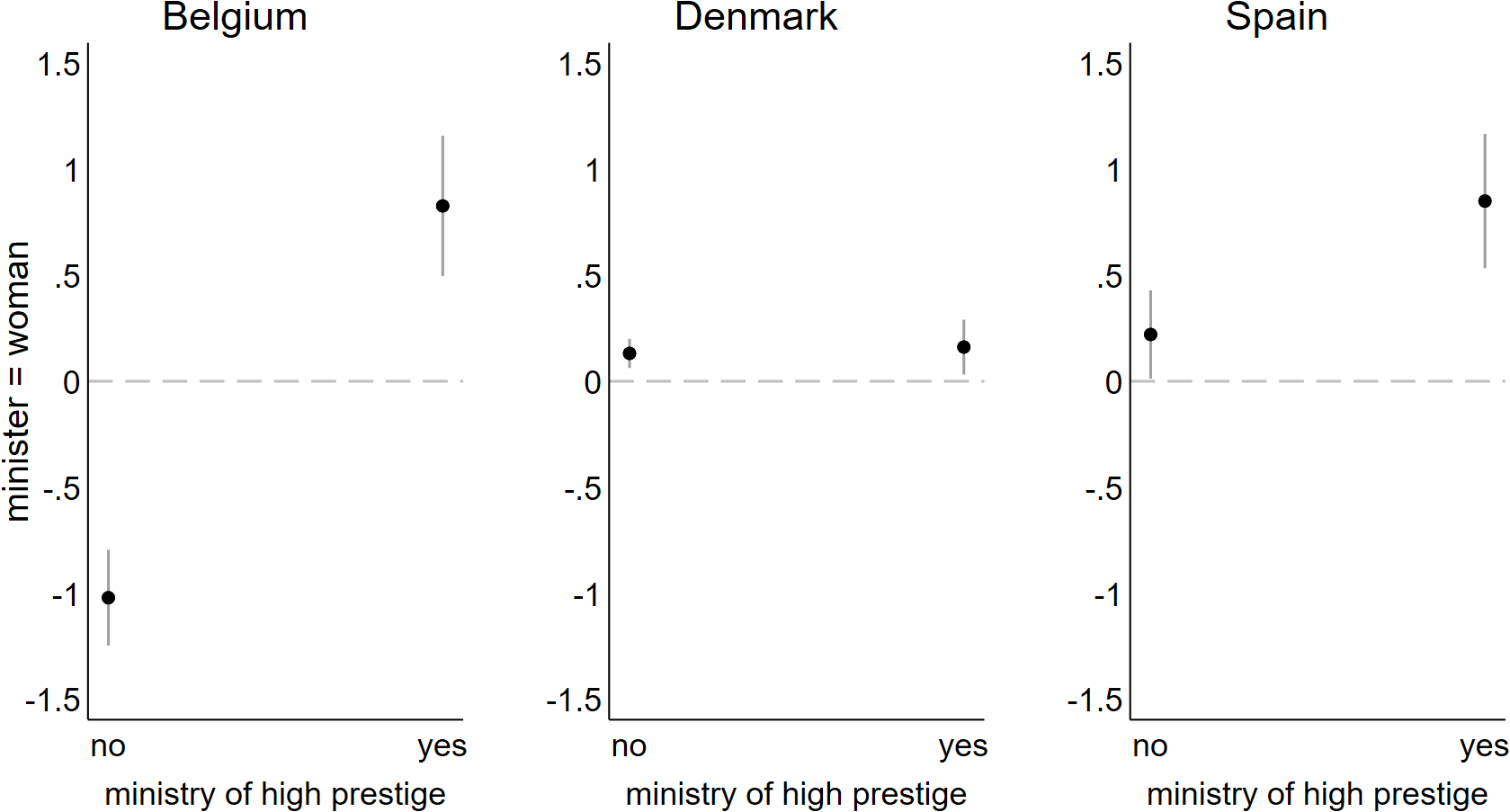

We extend our analysis with additional models to examine factors that may condition gendered patterns of legislative oversight. Specifically, we aim to determine whether gender bias in the questioning activities of Belgian MPs arises under certain specific conditions and whether the observed effects in other cases are context dependent. First, we test whether disparities in the number of questions directed at men and women ministers occur primarily in highly prestigious portfolios. Certain portfolios command greater visibility, policy-making influence, and social standing (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2005, 833). Finance and budget, interior, economy, employment, foreign and EU affairs, and defense are typically regarded as high-prestige portfolios, whereas health, environment, family, agriculture, justice, or transportation are generally of lower prestige. Women’s lower likelihood of securing highly prestigious portfolios (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012) suggests that gender stereotypes about women’s governing capacity may be particularly pronounced when they occupy these roles. Similarly, gendered patterns of legislative oversight may be limited to these prestigious posts. To test this conditional effect, we interact the minister’s sex with a binary variable coded ‘0’ for low- or medium-prestige portfolios and ‘1’ for high-prestige portfolios.Footnote 13 Given the need for sufficient degrees of freedom when introducing an interaction with a panel-level variable, we limit these models to the three countries with more than ten ministerial replacements: Belgium, Denmark, and Spain. The results are displayed in Figure 4, with full models provided in Table A3.3 in Appendix 3. We find a substantial gender gap in the number of questions directed at ministers holding highly prestigious portfolios in Belgium. In Denmark and Spain, gendered oversight patterns persist largely independent of portfolio prestige.

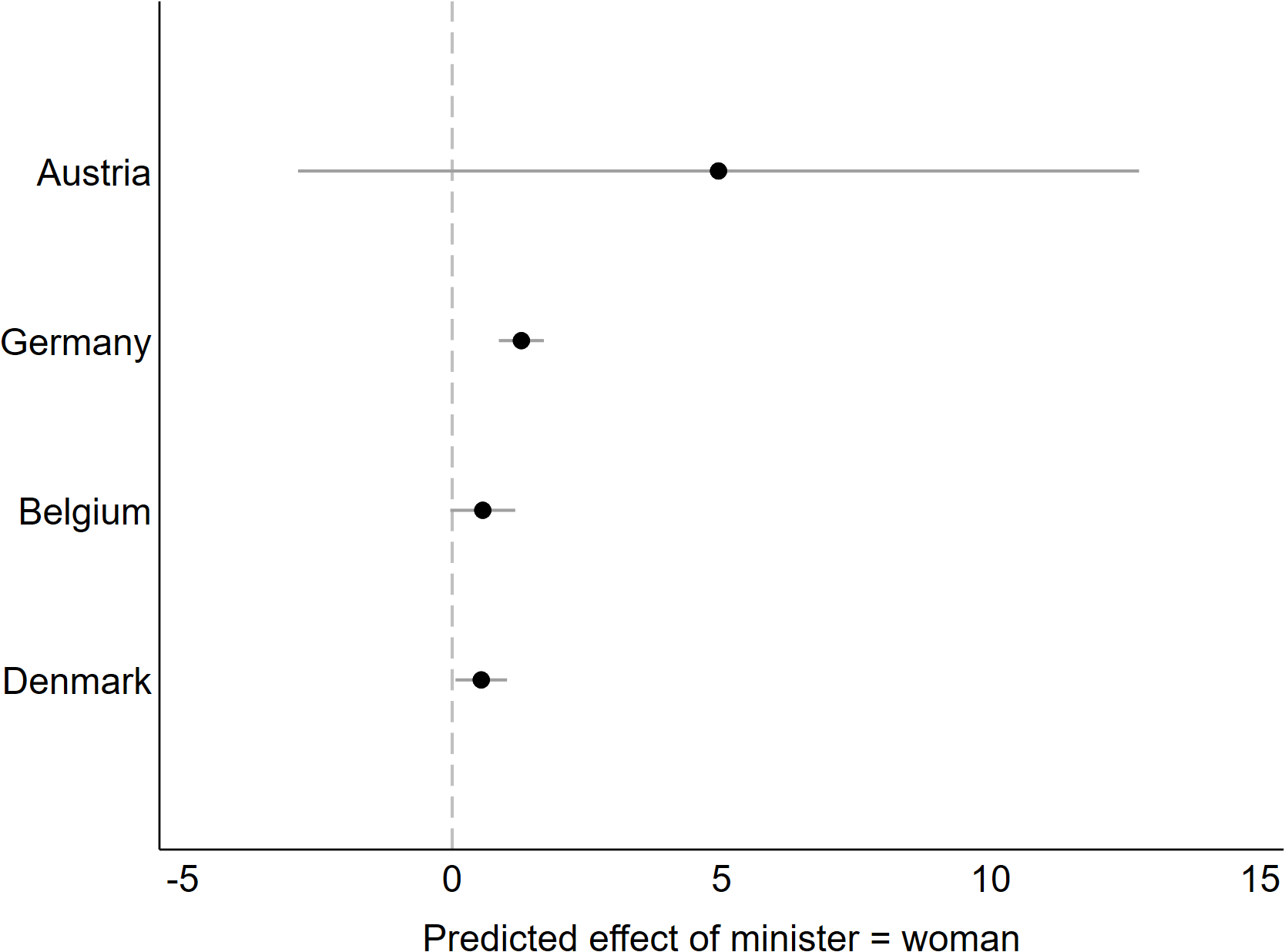

In a second set of additional models, we examine whether gender bias differs between written and oral questions. Oral questions may be more prone to gender bias than written ones. MPs typically prepare written questions carefully, whereas oral questions are often posed on short notice (for an overview of the rules governing written and oral questions, see Table 1.4 in Appendix 1). Research indicates that individuals are less likely to show prejudice when they are able to engage carefully with politicians (Setzler Reference Setzler2019). Thus, MPs may have more opportunity to mitigate gender bias when drafting written questions, whereas oral questions may reflect more spontaneous, unfiltered behavior. To test this, we separate the monthly count of written and oral questions in additional models (excluding Spain, where we only study oral questions) (see Figure 5 and Model A3.5 in Appendix 3). The vast majority of parliamentary questions are written, with ministries receiving an average of 9.8 written questions per month but only 1.2 oral questions.Footnote 14 As a result, when modeling only written questions, the findings remain largely consistent with the main models (see Table A3.4 in Appendix 3). When analyzing only oral questions separately, the effects persist as in the main models.

In Appendix 4, we conduct a series of additional robustness tests to further scrutinize these findings. First, adding confounders for ministers’ political outsider and technocracy status shows no indication of omitted variable bias (see section ‘Omitted variable bias’ in Appendix 4). Second, excluding ministries that received exceptionally high numbers of questions does not change the results, indicating that the observed gender bias in legislative oversight is not driven by influential outliers (see section ‘Sensitivity to influential observations’ in Appendix 4). Third, we further examine contextual variation. Gendered legislative oversight appears across MPs of different genders, ideological camps, and time periods, as well as across the full duration of governments (see section ‘Conditionality of the effect of minister’s gender’ in Appendix 4). Notable exceptions emerge in three contexts. In Spain, the effect of ministers’ gender does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance when limiting the sample to men MPs from the opposite ideological camp as the minister’s party; in Denmark, gender differences in legislative oversight appear to be concentrated in the first twenty months of a cabinet; and in Belgium, heightened oversight of women ministers was visible for women ministers who are replacements. These insights point towards the importance of studying variation in the degree to which oversight is gendered in future research. Lastly, alternative categorizations of ministerial portfolios based on gendered issue areas and levels of policy-making activity show that the effect of ministers’ gender is not limited to a particular type of portfolio (see section ‘Alternative measures of portfolio content’ in Appendix 4).

In sum, women ministers tend to receive more questions than their men predecessors and successors, independent of their political experience, in four of the five countries. This pattern holds across variations in ministry prestige and for both written and oral questions. Even in Belgium, the only country where the main model does not indicate a gender bias in legislative oversight, disparities emerge for specific contexts such as highly prestigious portfolios and for women replacement ministers.

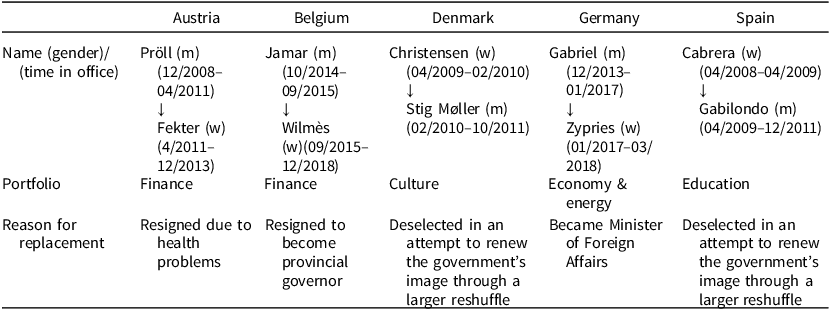

Studying the Causal Mechanism

To probe the mechanisms behind the observed patterns of gendered legislative oversight, we conducted semi-structured interviews with MPs in the five countries. In the interviews, MPs were asked to reflect broadly on their oversight practices and to assess their control of a specific man and woman minister involved in a replacement. Table 1 provides an overview of the selected ministerial replacements, with detailed descriptions in Appendix 5.1. We chose ministerial replacements that mirror the broader population of ministerial appointments. The replacements were not triggered by ministerial competence issues or scandals and included portfolios of varying prestige. Moreover, we ensured comparability of the political experience of the man and woman minister. In total, we interviewed thirty-two MPs who were in parliament during the ministerial replacement, averaging seven per country. All interviewees were members of a parliamentary committee linked to the portfolio in which the ministerial change took place, ensuring that oversight of the ministers in question was a salient part of their work and thereby enhancing the reliability of retrospective accounts.Footnote 15 Appendix 5 provides background information on the interview process (Section 5.2), questionnaire (Section 5.3), case study role (Section 5.4), interviewee selection (Section 5.5), transcription (Section 5.6), and data protection strategy (Section 5.7).

Table 1. Oversight of the case studies surveyed in the qualitative interviews

Note: Details on the case studies are provided in Appendix 5.1.

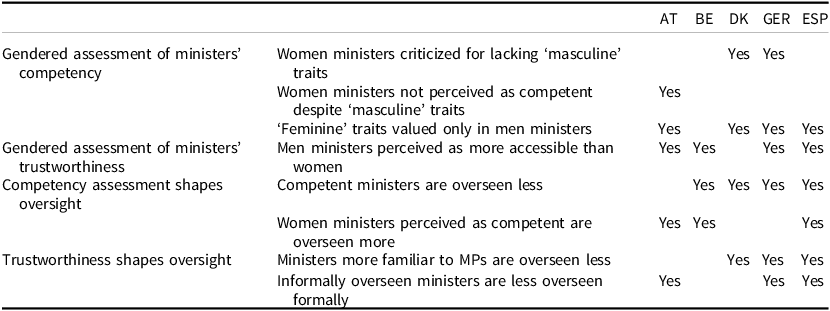

We analyze the interviews using qualitative content analysis, documented in Appendix 6, which details the coding procedure (Section 6.1) and coding scheme (Section 6.2). In the following, we assess to what extent the evidence supports the proposed causal mechanisms and challenge alternative explanations. We propose that differences in MPs’ competency assessments and trust in men and women ministers drive gendered patterns of legislative oversight. These processes unfold in two steps: (1) MPs perceive men and women ministers’ competence and trustworthiness differently and (2) MPs adjust their oversight accordingly. The analysis disentangles these steps and evaluates the evidence for each of the steps. Table 2 provides an overview of the patterns identified in the qualitative interviews.

Table 2. Overview of indications of gendered patterns of legislative oversight in the qualitative interviews

To begin with, we observe that gender stereotypes shape how MPs perceive the competency of men and women ministers. MPs’ responses indicate that gender stereotypes can directly diminish perceptions of women ministers’ competence, create role incongruencies that undermine the assessment of women ministers, or allow men ministers to benefit from exhibiting traits traditionally ascribed to women. We asked respondents to evaluate the work of men and women ministers and to compare their work. While peculiarities of the cases influence the way perceptions of ministers are gendered, MPs in all cases but Belgium express stereotypical assessments of ministers’ characteristics. In Germany and Denmark, there is evidence that MPs perceive women ministers as less competent because they do not display typically masculine traits. In Germany, MPs describe Zypries (w) as lacking the manipulativeness and the assertiveness displayed by Gabriel (m) (GER01; GER02; GER03, GER04; GER06). At the same time, MPs show appreciation for Gabriel’s tactics and link it to his perceived competence: ‘What happened with Gabriel was that he also played dirty. You have to admire him. He understood our way of working, so to speak, and then [he] developed his own tools to catch us out, which meant we had to think along with Gabriel. Zypries didn’t play dirty, so we didn’t have to play any more tricks’. (GER01 00:03:31-9). In Denmark, MPs describe Christensen (w) as ‘not a typical politician’ (DK04 00:9:40-4), because she – as Zypries (w) (GER03) – demonstrates co-operation and negotiation skills (DK04). These responses align with previous research showing that women in leadership positions are often criticized for lacking stereotypically masculine traits commonly associated with strong political leadership (Bruckmüller et al. Reference Bruckmüller, Ryan, Rink and Haslam2014; Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt Reference Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt2001; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Butterfield and Parent2002; Schein and Mueller Reference Schein and Mueller1992).

The Austrian case provides evidence in line with role congruity theory (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Heilman and Okimoto Reference Heilman and Okimoto2007; Rudman et al. Reference Rudman, Moss-Racusin, Phelan and Nauts2012). Respondents perceive Fekter (w) as having more expertise in the role as minister of Finance compared to Pröll (m) (AT01, AT06). MPs describe Fekter (w) as aggressive and assertive, expressing appreciation for these characteristics. Nevertheless, MPs rate her overall competency in office lower than that of her men predecessor. As one of the MPs put it: ‘If you ask me who I preferred as finance minister, my God, I personally liked Josef Pröll better’ (AT04 00:21:48).

Additionally, men ministers are praised for exhibiting traits stereotypically associated with women, whereas women ministers do not receive similar recognition. In both the Spanish and Austrian case, men ministers are commended for displaying feminine characteristics such as politeness and kindness (AT01; ES02), as well as the ability to compromise and to display empathy (ES03; ES06; ES07). As a Spanish respondent noted: ‘Ángel Gabilondo is a person who garners consensus and understanding’ (ES03 00:37:01-5). By contrast, these characteristics are only mentioned in passing for women ministers. In Germany, Zypries (w) is presented as co-operative (GER01; GER02); in Spain, Cabrera (w) as just as kind as Gabilondo (m) (ES04); and in Denmark, Christensen as diplomatic but not a ‘real politician’ (DK04). MPs’ responses in Denmark, Germany, Austria, and Spain suggest that traits typically ascribed to women seem to be more highly valued when exhibited by men ministers, but not when displayed by women ministers.

Beyond gendered perceptions of competence, MPs’ assessment of men and women ministers’ trustworthiness tends to differ. If trusted individuals are understood as allies who participate in common personal political and party networks (Levi and Stocker Reference Levi and Stoker2000, Annesly et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019), informal accessibility of a minister should shape their trustworthiness. In this context, we observe that MPs generally perceive men ministers as more accessible than women ministers in all case studies except Denmark. In Austria, MPs perceive Pröll (m) as well-connected and approachable (AT02, AT01), whereas Fekter (w) is seen as unapproachable (AT04). In Germany, MPs agree that Gabriel (m) is highly connected and easily accessible through informal channels, while Zypries (w) appears to prioritize interpersonal contact less (GER01, GER02, GER04). In Spain, interviewees highlight Gabilondo’s (m) accessibility (ES06). Belgian MPs similarly describe Jamar (m) as more of a people person compared to Wilmès (w) (BE01, BE02).

Our qualitative evidence is also consistent with the second step of the proposed causal chain: perceptions of ministers’ competence and trustworthiness shape the intensity of MPs’ oversight in the five ministerial replacements under study. To examine this, we asked MPs what factors influence variation in their formal and informal oversight activities. Linking competence to oversight, MPs in all countries except Austria explicitly state that they scrutinize individuals they perceive as less competent more thoroughly (BE01, BE03, BE04, DK04, DK05, ES03, ES04, ES05, GER06, GER07). A Danish MP explicitly acknowledges the gendered role of competence, stating: ‘But of course, I think the same inequalities you see in the society, they are also produced in parliament. So of course, women ministers have more problems’ (DK01 00:21:26-5).

However, according to MPs’ responses in the case studies, perceptions of how competence relates to oversight display a double-bind for women ministers in Austria and Belgium. In these cases, several respondents who describe the women ministers as more competent assume that the women receive more questions precisely because of their competence (AT01, AT06, BE02, BE03). In this regard, the Belgian case displays a unique narrative compared to the others. All MPs discussing the replacement of Jamar (m) with Wilmès (w) view the woman as significantly more qualified than her man counterpart (BE01, BE02, BE03, BE04, BE06). MPs justify the higher level of oversight towards Wilmès (w) by citing her expertise in finance. As one Belgian MP explains: ‘With Wilmès, there were more challenging questions because she was able to tell more on these things. Like I said, she was more in finance than Jamar. So, you could challenge her more on specific topics’ (BE 00:21:39-4). These responses suggest that women ministers face heightened scrutiny even if they are perceived as competent – which points towards the importance of trust for oversight (or the lack thereof).

Regarding the role of trust for shaping legislative oversight, MPs in all countries except Belgium indicate that greater trust in a minister leads to less intensive scrutiny. Respondents note that ministers who are newer (DK03; DK04) are less connected (GER06, ES01), and therefore less familiar and accessible to MPs, and thus tend to be more closely monitored. In a similar vein, interviewees emphasize that the informal accessibility of a minister correlates with reduced formal oversight (AT04; ES03, ES04; ES06). In Austria, MPs highlight the informal nature of interactions with Pröll (m): ‘Well, with Mrs. Fekter the control mechanisms were rather limited to written questions and question time in parliament. Informally not so much. The informal aspect was more present during visits to Josef Pröll’s ministerial office’ (AT04 00:23:29). In Germany, MPs similarly mention that Gabriel (m) was more accessible for oversight through informal channels than Zypries (w) (GER02). Likewise, in Spain, Gabilondo (m) was ‘more accessible and more receptive’ (ES06 00:12:01-1) informally than Cabrera (w). These responses indicate that MPs also oversee ministers they trust, but in a way that is less impactful. While technically allowing them to oversee the ministers’ actions, informal oversight serves somewhat different purposes than formal oversight, as it does not make the oversight process visible to the public and other politicians. Essentially, it implies giving the minister the opportunity to provide transparency and accountability to the MP in a protected environment. Formal oversight, by contrast, entails making MPs’ critiques and ministers’ justifications visible to the public and is therefore more likely to create pitfalls for politicians.

In sum, our qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews with MPs indicates that the causal mechanisms we developed in the theory section were indeed at play in the five ministerial replacements under study. First, when MPs were asked about their assessment of the ministers involved in these ministerial replacements – which occurred for exogenous reasons and involved largely comparable individuals – they indicated that they perceived the men ministers as more competent and trustworthy than the women ministers. Second, MPs suggested that these assessments directly influenced their oversight behavior, as they scrutinize more closely those ministers they perceive as less competent and trustworthy. Some MPs also noted that they oversee women ministers more tightly when they perceive them as particularly competent. Yet, the evidence also suggests that not all mechanisms operate simultaneously in every country.

Two alternative causal mechanisms could also explain gender bias in legislative oversight: gendered administrative support and gendered popularity. We inquired whether MPs perceive these factors to be relevant drivers of their oversight activities in the interviews (for a detailed discussion, see Section 6.3 in Appendix 6). First, one might argue that women ministers receive systematically less support from their ministerial staff than men ministers, leading to lower performance and, consequently, higher scrutiny. To assess this claim, we asked MPs whether they recalled differences in how men and women ministers were received within their ministries. Across all cases, respondents perceive administrative structures as offering equal professional support to ministers regardless of gender, with bureaucracies seen as neutral, loyal, and technically proficient (AT01, AT02, AT04, AT05, AT06, BE01, DK04, ES01, ES04, ES05, ES07, GER01, GER02). Second, gender bias in public popularity and media assessment could lead to heightened oversight, as MPs might capitalize on public criticism or negative press targeting women ministers. To investigate this, we asked MPs about the public perception of the ministers and whether they believe it influenced their oversight behavior. While some MPs acknowledge gender bias in media coverage (AT07, GER01), they generally deny that it shapes their oversight activities (AT03, BE04, DK05, GER04). A few interviewees consider such a link plausible but provide contradictory responses concerning its direction. Some suggest that higher popularity leads to lower oversight (DK04, GER04, GER06, GER03), arguing that it is more difficult to challenge a well-liked minister. Others state that popular ministers attract more scrutiny because engaging with them can provide MPs with media visibility (BE06, BE05; DK03). In sum, this additional evidence does not provide any indication that MPs believe these two mechanisms are of particular relevance for their oversight activities. These insights reinforce our argument that gender stereotypes and gendered trust networks are the primary drivers of gendered oversight patterns.

Conclusion

This article is the first to demonstrate that legislative oversight is a gendered process. While previous research on parliamentary control of the executive has focused on institutions, party competition, and, more recently, MPs’ characteristics in shaping oversight intensity and methods (Akbik and Migliorati Reference Akbik and Migliorati2022; Celis Reference Celis2006; de Vet and Devroe Reference de Vet and Devroe2023a; Friedberg Reference Friedberg2011; Höhmann and Krauss Reference Höhmann and Krauss2022; Höhmann and Sieberer Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020; Martin Reference Martin2011; Pelizzo and Stapenhurst Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2013; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2000), this study shifts the focus to how ministers’ characteristics influence the extent of oversight. We develop the theoretical argument that parliamentarians oversee women ministers more tightly than men ministers and identify two causal mechanisms driving this pattern: first, men ministers are perceived as more competent than women. MPs tend to value masculine traits in government members more highly than feminine traits, leading to a systematic bias in favor of men. Second, men ministers are perceived as more trustworthy than women. MPs perceive men government members as reliable partners who can be confided in due to their dense political networks and their shared characteristics with the majority of (men) MPs (Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2018). We provide empirical support for this argument through a quantitative analysis of parliamentary questions in five European democracies. Qualitative interviews with thirty-two MPs in all countries, each studying a specific ministerial replacement, support the proposed causal mechanism.

Finding that legislative oversight is a gendered process has important implications for the functioning of parliamentary democracy. As MPs scrutinize women ministers more closely, they risk overlooking major shortcomings of men ministers. Given that legislative oversight is crucial for government accountability, this incomplete scrutiny weakens parliamentary democracy (Pelizzo and Stapenhurst Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2013). Future research should explore whether this issue is likely to intensify with ongoing efforts to involve civil society in the oversight process (Pelizzo and Stapenhurst Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2013). Citizens are generally less informed about ministers’ performance than MPs, but research is at odds about which consequences limited information about leaders entail for women. While some research argues that less-informed individuals use gender cues more frequently (Eagly and Wood Reference Eagly, Wood, Wong, Wickramasinghe, Hoogland and Naples2016; Heilman Reference Heilman2012), others find that they are less dependent on gender stereotypes to assess the leadership of a women (Taylor-Robinson and Geva Reference Taylor-Robinson and Geva2023). As a result, incorporating civil society into legislative oversight may exacerbate or reduce gender disparities in scrutiny. While public engagement may enhance the legitimacy of parliamentary democracy (Pelizzo and Stapenhurst Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2013), it is unclear whether it also makes oversight less effective and more unequal. Future research should explore the role of gender when civil society is involved in government oversight.

This study’s main finding about gendered oversight is also consequential for understanding the unequal careers of men and women in top political offices. Women leaders operate in particularly demanding environments (Aldrich and Somer-Topcu Reference Aldrich and Somer-Topcu2025), in which they are held to higher standards than men (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015). While electoral performance constitutes a heightened expectation placed on women party leaders (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015, Aldrich and Somer-Topcu Reference Aldrich and Somer-Topcu2025), stricter parliamentary scrutiny represents a higher standard for women ministers. Future research should examine whether further double standards exist in other core tasks of political leadership. For example, are women ministers expected to deliver more substantial policy innovation than men, possibly as a consequence of stereotypes linking women to consensus-building and foresight? Or, are women prime ministers expected to combine directive and participative leadership styles simultaneously to balance role incongruency concerns, while it suffices if men show one or the other? Exploring these questions would shed light on the broader range of higher standards that constrain women’s political careers (Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O’Brien2024; Bright et al. Reference Bright, Döring and Little2015; Curtin et al. Reference Curtin, Kerby and Dowding2023; Kroeber and Hüffelmann Reference Kroeber and Hüffelmann2022; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015; O’Neill et al. Reference O’Neill, Pruysers and Stewart2019; Saaka Reference Saaka2025), and advance our understanding of why women who reach high office often struggle to sustain or expand their influence.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425101221.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DZLCQL.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to everyone who contributed to the development of this paper. We are particularly grateful to the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions. Moreover, we are especially thankful for the valuable feedback and insightful discussions provided by colleagues during the various conferences where we presented earlier versions of this work. Special thanks go to Amber Brittain-Hale, Susan Franceschet, Thomas Zittel, Murat Yildirim, and Despina Alexiadou, who gave valuable feedback as discussants, but also all panel participants at EPSA the Annual Conference 2023 (Glasgow, Scotland), Conference of the ECPR Standing Group on Parliaments 2023 (Vienna, Austria), DVPW TG Vergleichende Parlamentarismusforschung 2023 (Bamberg, Germany), and APSA Annual meeting 2024 (virtual conference). Additionally, we are grateful for helpful feedback from the participants of the GSParls Workshop ‘Gender and Intersectionality in the Finnish, German, and Polish Parliament’, the research seminars of the Cologne Center for Comparative Politics, the Democratic and Comparative Politics Research Group (DAC) at Copenhagen University, the Comparative Politics Colloquium and the Interdisciplinary Center for Gender Studies workshop (IZfG) at the University of Greifswald, and the GASPAR Research Group at Ghent University. Furthermore, we are thankful to Dominik Duell and Marcelo Jenny for providing feedback to our interview guidelines. Finally, we are also deeply grateful to our student assistants – Dzaneta Kaunaite, Lena Elsa Droese, Cord Masche, Jonas Ruben Lück, Niklas Otremba, Katharina Isser, and Valentina Chesi – for their invaluable research support.

Financial support

This research was funded by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation (Aktenzeichen: 10.21.1.006PO).

Competing interests

The authors do not declare any conflict of interest.

Note

This research is part of the larger project ‘Can a woman do the job? Introducing a gender perspective on legislative oversight’ jointly and with equal responsibilities led by Sarah C. Dingler and Corinna Kroeber.