Significant Outcomes

This study provides an integrated perspective by simultaneously examining common psychological risk factors for food addiction (FA), problematic internet use (PIU), and internet gaming disorder (IGD).

Mental health predictors such as depression, anxiety, and stress were found to have distinct patterns of association for each behavioral addiction, highlighting that they are not uniformly associated across all three.

The relatively high prevalence of PIU (14.3%) underscores the urgent need for targeted public health and school-based interventions to promote healthy digital habits among adolescents.

Limitations

The study’s cross-sectional nature prevents the establishment of causal relationships or the determination of the temporal sequence between psychological factors and the onset of behavioral addictions.

The use of convenience sampling via school-based online recruitment may have introduced the risk of selection bias, potentially leading to an inaccurate representation of true prevalence rates in the general adolescent population.

The fact that the study sample consists only of high school students in one province may limit the generalizability of the findings to a broader population.

Introduction

Behavioural addictions (BAs), characterised by compulsive, repetitive behaviours leading to significant harm or distress and impaired functioning, are increasingly recognised as a major concern, particularly among adolescents (Kardefelt-Winther et al., Reference Kardefelt-Winther, Heeren, Schimmenti, van Rooij, Maurage, Carras, Edman, Blaszczynski, Khazaal and Billieux2017). Although traditional addictions pose a major public health problem among adolescents, the prevalence and impact of non-substance-related addictive behaviours have gained increasing attention in recent years, leading to a growing interest in the literature (Estévez et al., Reference Estévez, Jáuregui, Sánchez-Marcos, López-González and Griffiths2017; Griffiths, Reference Griffiths2017). While behavioural addictions related to the internet, digital media, and technology have been more extensively studied, research on non-internet-related addictions remains relatively limited, with even fewer studies examining the relationship between technological and non-technological BAs (Park et al., Reference Park, Hwang, Lee and Bhang2022; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Latner, O’Brien, Chang, Hung, Chen, Lee and Lin2023; Kucuk & Alemdar, Reference Kucuk and Alemdar2023). Adolescence, a critical developmental period, presents a heightened vulnerability to developing these unhealthy behaviours (French et al., Reference French, Story, Neumark-Sztainer, Fulkerson and Hannan2001; Schiestl et al., Reference Schiestl, Rios, Parnarouskis, Cummings and Gearhardt2021).

Food addiction (FA) is a non-digital behavioural addiction characterised by compulsive seeking and consumption of food, development of tolerance and withdrawal symptoms, and activation of reward pathways in the brain, mirroring the neurobiological mechanisms observed in substance addictions (Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Mannarini, Castelnuovo and Pietrabissa2023). The prevalence of FA among adolescents varies widely, ranging from 2.6% to 49.9%, highlighting the need for further research in this area (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Jebeile and Burrows2021). This variability may be partly attributed to the unique challenges adolescents face in establishing healthy dietary habits, including increased consumption of fast food, processed foods, and irregular eating patterns, all of which can contribute to FA and subsequent health issues like obesity (French et al., Reference French, Story, Neumark-Sztainer, Fulkerson and Hannan2001; Schiestl et al., Reference Schiestl, Rios, Parnarouskis, Cummings and Gearhardt2021). Importantly, FA shares common risk factors with other BAs, suggesting potential overlapping vulnerabilities (Alavi et al., Reference Alavi, Ferdosi, Jannatifard, Eslami, Alaghemandan and Setare2012).

The digital age has witnessed a dramatic increase in internet usage across all age groups, with adolescents and young adults at the forefront (Terres-Trindade & Mosmann, Reference Terres-Trindade and Mosmann2016). This increased exposure has led to a rise in PIU, with global prevalence rates ranging from 0.7% to 35.5%, and in Turkiye, from 1.3% to 16.1% (Goel et al., Reference Goel, Subramanyam and Kamath2013; Kilic et al., Reference Kilic, Avci and Uzuncakmak2016; Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Neupane, Rijal, Thapa, Mishra and Poudyal2017; Sayili et al., Reference Sayili, Pirdal, Kara, Acar, Camcioglu, Yilmaz, Can and Erginoz2023). Similarly, IGD, another prevalent BA, has reported global prevalence rates between 1.6% and 29.3%, with Turkish studies reporting rates of 4.32% to 28.8% (Alfaifi et al., Reference Alfaifi, Mahmoud, Elmahdy and Gosadi2022; Irmak & Erdoǧan Reference Irmak and Erdoǧan2019; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Janikian, Dreier, Wölfling, Beutel, Tzavara, Richardson and Tsitsika2015). PIU and IGD are associated with a range of negative psychological, physical, and social consequences (Yen et al., Reference Yen, Yen and Ko2010; Zeyrek & Fatih Tabara, Reference Zeyrek and Fatih Tabara2024). These include loneliness, low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, poor coping skills, impulsivity, emotional regulation difficulties, and sleep disturbances. Individuals struggling with these addictions often prioritise online activities over essential needs such as sleep, nutrition, and social relationships, leading to health problems like back pain, eye fatigue, and even eating disorders (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee and Choo2017). Furthermore, these addictions can have devastating psychosocial impacts, including school or work dropout, relationship breakdowns, and strained family dynamics (Bargeron & Hormes, Reference Bargeron and Hormes2017).

Epidemiological studies have investigated PIU, IGD and FA separately; however, research examining the relationship between FA and other digital addictions remains limited (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Jebeile and Burrows2021; Szerman et al., Reference Szerman, Basurte-Villamor, Vega, Mesías, Martínez-Raga, Ferre and Arango2023). Despite shared underlying mechanisms and potentially overlapping risk factors, the complex interplay between these behaviours is not fully understood (Alavi et al., Reference Alavi, Ferdosi, Jannatifard, Eslami, Alaghemandan and Setare2012). Several studies have begun to explore these relationships but more research is crucial (Park et al., Reference Park, Hwang, Lee and Bhang2022; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Latner, O’Brien, Chang, Hung, Chen, Lee and Lin2023; Kucuk & Alemdar, Reference Kucuk and Alemdar2023). This study addresses this gap by taking a holistic approach, examining the prevalence of these co-occurring behavioural addictions among adolescents and investigating shared risk factors. Identifying these common risk factors will be crucial for developing comprehensive and effective intervention programmes aimed at preventing and addressing these interconnected challenges.

Methods

Design and setting

The study is cross-sectional, targeting high school students in grades 9, 10, 11 and 12 in 33 schools in Bingöl province. The students participating in this study were selected by convenience sampling, which involves selecting individuals who are easily accessible or willing to respond. 866 students participated in the study in this way. In order to conduct the study, permission was obtained from the Directorate of National Education. The study link was shared with all accessible students in 33 schools. Participation was voluntary, and students could proceed with the online survey only after selecting the “I voluntarily agree to participate in this study” option at the beginning of the questionnaire. Parents and subjects agreed to participate and signed informed consent. It was made clear that participant identities would remain anonymous. The online questionnaire was designed to be completed at home to provide a quieter and more comfortable environment for students. Teachers were trained on the study to ensure that they could support the process effectively. Students reached out to their teachers if they had any questions about the study or the survey items so that they could receive guidance and clarification when they needed it.

Data was collected between September 2023 and November 2023. The questionnaire was created and data was collected using Google Forms. It consists of eight sections. The scales used in sections three to eight are also included. The first section provides a brief introduction to the study and an option to approve participation. The second section assesses the demographic characteristics of the participants, including age, gender, class, income, academic achievement, daily screen and sleep time, and leisure time activity.

Demographic variables such as income, screen time and academic achievement provide insight into the risk factors associated with behavioural addictions. These factors exert an influence on behaviours including internet use, gaming habits and emotional regulation (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Pu, He, Yu, Xu, He, Chen, Gan, Liu, Tan and Xiang2022). For instance, income affects technology access, screen time is linked to internet use and academic achievement may indicate underlying psychological challenges. The analysis of these variables facilitates an exploration of the ways in which different aspects of students’ lives contribute to the risk of addiction.

Ethical approval

The ethics committee of Bingol University approved this study (Approval number: 33117789/044/135265). The procedures followed during the present study were completely in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Measures

In the study, six internationally validated and reliable scales were employed, each utilising Turkish versions that have undergone validation and reliability testing (Arıcak et al., Reference Arıcak, Dinç, Yay and Griffiths2018; Durmuş et al., Reference Durmuş, Torlak, Tüğen and Güleç2022; Kutlu et al., Reference Kutlu, Savci, Demir and Aysan2016; Tetik & Cenkseven Önder, Reference Tetik and Cenkseven Önder2021; Tok et al., Reference Tok, Ekerbicer and Yazici2023; Yılmaz et al., Reference Yılmaz, Boz and Arslan2017). These included the Modified Yale Food Addiction Scale Version 2.0 (mYFAS 2.0), Young’s Internet Addiction Test-Short Version (IAT-SV), Internet Gaming Disorder Scale 9-Short Form (IGDS9-SF), Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-Brief (BIS-Brief), Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) and Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (ERQ-CA) (Lovibond & Lovibond, Reference Lovibond and Lovibond1996; Gullone & Taffe, Reference Gullone and Taffe2012; Pawlikowski et al., Reference Pawlikowski, Altstötter-Gleich and Brand2013; Steinberg et al., Reference Steinberg, Sharp, Stanford and Tharp2013; Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2015; Schulte & Gearhardt, Reference Schulte and Gearhardt2017). The ERQ-CA contains 10 items that assess the emotion regulation strategies of cognitive reappraisal (6 items) and expressive suppression (4 items). The scale scoring criteria and category cut-off points provided by the respective author of each scale were not altered. The diagnosis of FA (mild = 2–3 symptoms and impairment, moderate = 4–5 symptoms and impairment, severe = 6 or more symptoms and impairment) was accepted (Gearhardt et al., Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell2016). The cutoff value for the IAT-SV was set at 36 based on literature values (Meerkerk, Reference Meerkerk2007; Tran et al., Reference Tran, Mai, Nguyen, Nguyen, Latkin, Zhang and Ho2017; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Tran, Huong, Hinh, Nguyen, Tho, Latkin and Ho2017). The cut-off score for IGDS9-SF was also set as 36. To assess specific domains of behavioural addictions, three scales (mYFAS 2.0, IAT-SV, IGDS9-SF) were used. Impulsivity was measured using the BIS-Brief, emotion regulation was assessed using the ERQ-CA, and depression, anxiety, and stress were evaluated using the DASS-21.

Data analysis

The study employed an online questionnaire where all questions were set as mandatory fields, reducing the likelihood of incomplete responses. As a result, there were no missing data in the final dataset used for analysis. In instances where participants did not complete the survey in its entirety (e.g., exiting before submission), their responses were not saved, as required fields ensure completeness. This approach ensured a clean dataset for analysis. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 was used to analyse the data (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Whether the data showed normal distribution was evaluated by Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables were compared with Chi-square test. Scale scores of those with and without food addiction and those with and without PIU were compared using the Student’s t-test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare scale scores between participants with and without Internet gaming disorder. Effect size values (Cohen’s d for Student’s t-test and Eta squared for Mann–Whitney U test) are given in the text together with p values. Correlations related to FA and IA were evaluated with Pearson’s correlation test, while correlations related to IGD were evaluated with Spearman’s correlation test. The variables predicting addictions were analysed in a multiple linear regression model. Variables for inclusion in the multiple linear regression models were selected based on their statistical significance (p < 0.05) in the bivariate analyses. Variables showing a significant association with the behavioural addiction scores (mYFAS, IAT-SV, IGDS9-SF) were included in the respective regression models. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were calculated to assess multicollinearity. All VIF values were below 5, indicating no significant multicollinearity among the predictors. Residual plots were visually inspected to ensure that the variance of residuals was consistent across the range of predicted values. The normality of residuals was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Q-Q plots. The residuals were found to approximate a normal distribution for all models. The adjusted R 2 values and p-values for each regression model were reported in Table 3, demonstrating the model fit and statistical significance. The adjusted R 2 values and p-values for each regression model were reported in the regression table (Table 3), demonstrating the model fit and statistical significance. Factors that were found to be significantly associated with the scores of all behavioural addiction scales according to bivariate analyses were included in the linear regression model. In all evaluations, p < 0.05 was accepted as the level of statistical significance.

Results

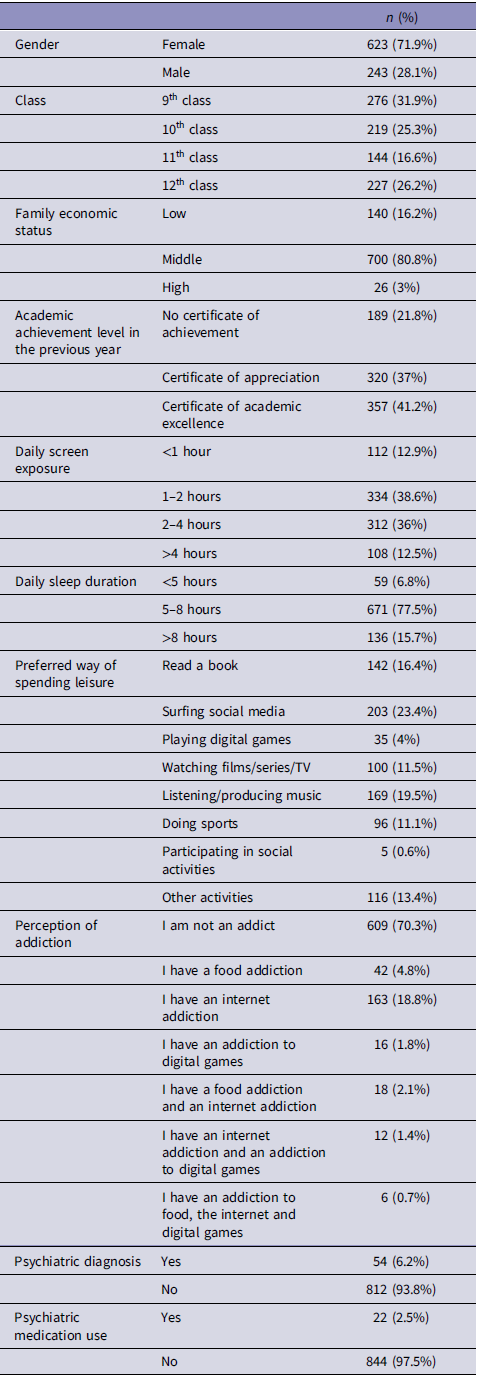

The study included 866 participants. The mean age of the participants was 15.19 ± 1.31 years. 71.9% (n = 623) of the participants were female and 28.1% (n = 243) were male. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

Food addiction

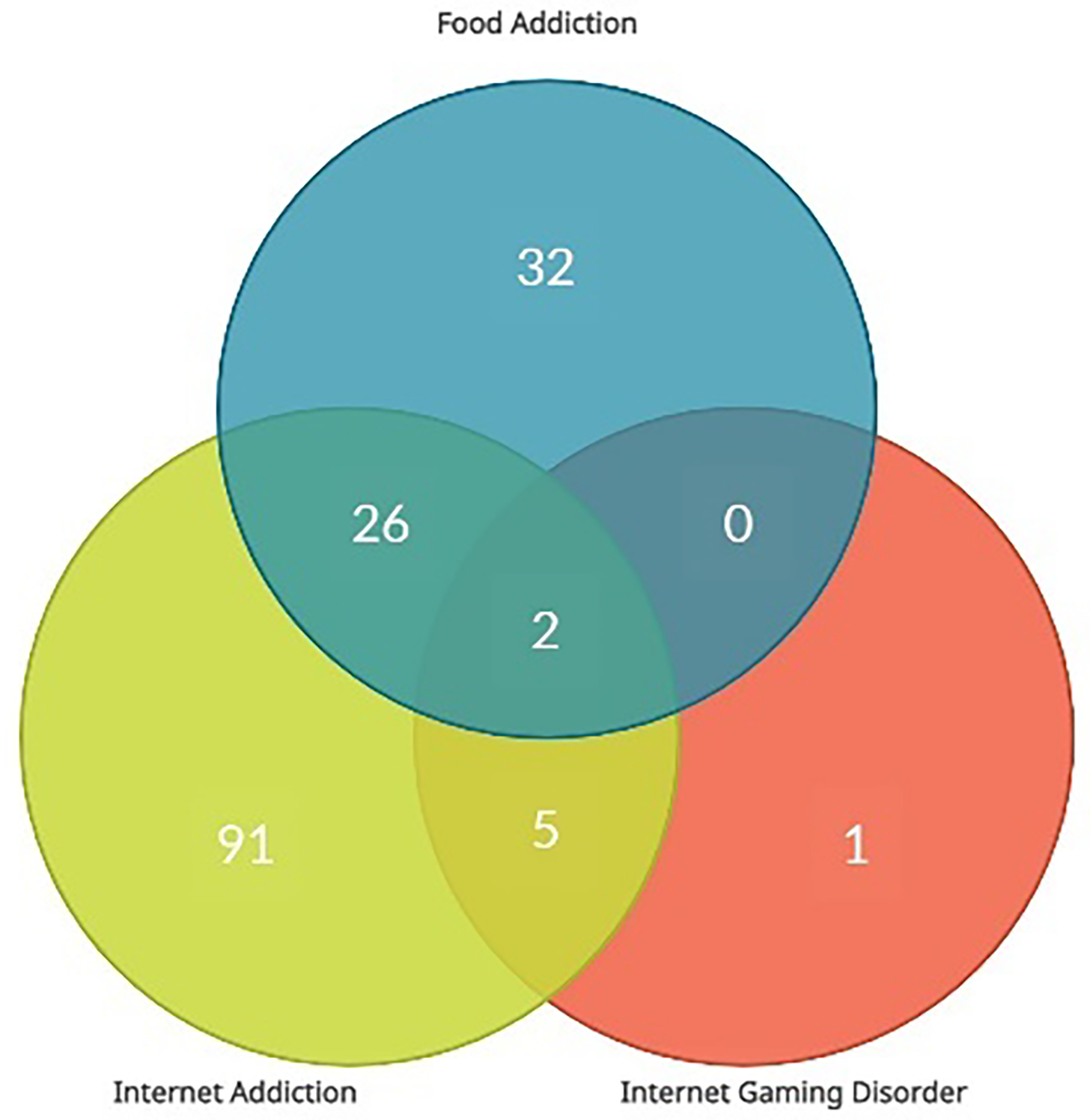

The prevalence of FA was found to be 6.9% (n = 60) (mild FA 3.2%, moderate FA 1.5%, severe FA 2.2%). No significant difference was found between the FA group and the non-FA group in terms of gender, class, family economic status, and academic achievement level variables (p > 0.05). When evaluated in terms of average daily screen exposure time, it was found that the FA group was significantly more exposed to the screen than the non-FA group (X2 = 11.901, p = 0.008). Mean sleep duration was similar in the FA and non-FA groups. In terms of leisure activities, it was found that the FA group spent more time on social media and participated less in sports activities (X2 = 15.147, p = 0.034). In the FA group, 11 (18.3%) participants had a psychiatric diagnosis, while 43 (5.3%) participants in the non-FA group had a psychiatric diagnosis (X2 = 16.137, p < 0.001). In addition, 10% (n = 6) of the FA group were taking psychiatric medication, compared with 2% of the non-FA group (X2 = 14.489, p < 0.001). The co-occurrence of behavioural addictions is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The venn diagram illustrates the overlap among food addiction, problematic internet use, and internet gaming disorder. Most participants were diagnosed with only one condition, with problematic internet use being the most prevalent. Overlaps were observed, with a small group sharing all three conditions and others sharing two. Notably, food addiction and IGD did not overlap directly without the presence of problematic internet use, highlighting unique and shared features of these behavioural addictions.

Participants were compared on the ERQ-CA and its subscales. There was no difference between the groups in terms of total score and cognitive reappraisal subscale scores. However, the expressive suppression subscale score of the FA group was significantly higher than that of the non-FA group (Cohen’s d = 0.44; p = 0.001). The groups were compared on the DASS-21 and its subscales. Stress, anxiety and depression subscale scores were significantly higher in the FA group (respectively Cohen’s d values = 1.07, 1.10 and 1.09; p < 0.001 for all). While the PIU score was significantly higher in the FA group (Cohen’s d = 1.07, p < 0.001), no significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of internet gaming disorder score (p = 0.093). Impulsivity scores of the FA group and the non-FA group were similar (p = 0.376).

To summarise, the FA group exhibited longer daily screen exposure, spent more time on social media, and engaged less in sports. Psychiatric diagnoses were more common in the FA group, as was psychiatric medication use. The FA group showed higher expressive suppression scores on the ERQ-CA and significantly elevated stress, anxiety, and depression scores on the DASS-21. PIU was higher in the FA group, but no differences were found in internet gaming disorder or impulsivity.

Problematic internet use

14.3% (n = 124) of the participants were found to be addicted to the internet and the mean score was 26.54 ± 9.26. No significant difference was found between the PIU group and the non-PIU group in terms of gender, class, family economic status, and academic achievement level variables (p > 0.05). When evaluated in terms of average daily screen exposure, it was observed that those with more screen exposure had a significantly higher frequency of PIU (X2 = 55.315, p < 0.001). Mean sleep duration was similar between the groups. The frequency of PIU was found to be significantly higher among those who spent their leisure time playing digital games and surfing social media (X2 = 15.171, p = 0.034). The frequency of psychiatric diagnoses and psychiatric medication use was similar in the group with and without PIU.

While ERQ-CA total score and expressive suppression subscale scores were significantly higher in those with PIU (respectively Cohen’s d values = 0.35 and 0.45; p < 0.001 for both), cognitive reappraisal subscale scores were similar (p = 0.062). Both the total DASS-21 score and the subscale scores were statistically significantly higher in the group with PIU (respectively; Cohen’s d values = 1.22, 1.09, 1.32 and 1.33; p < 0.001). IGDS9-SF scores were significantly higher in participants with PIU (Cohen’s d = 0.84, p < 0.001).

In a nutshell, PIU was significantly associated with increased screen time and spending leisure time on gaming and social media. Those with PIU showed higher scores on expressive suppression in emotional regulation and reported elevated stress, anxiety, and depression levels. Internet gaming disorder scores were also significantly higher among participants with PIU.

Internet gaming disorder

The frequency of internet gaming disorder (IGD) was 0.9% (n = 8). The mean score for the IGD was 13.20 ± 6.10. It was found that the prevalence of IGD did not vary according to socio-demographic variables such as gender, class, family income, academic performance in the previous year, sleep duration, presence of a psychiatric diagnosis and use of psychiatric medication (p > 0.05). IGD was more common in those with higher average screen exposure (p = 0.020). No significant difference was found when comparing participants with and without IGD on the ERQ-CA and its subscales (p > 0.05). Stress, anxiety and depression scores of those with IGD were higher than those without IGD (respectively; Eta squared (η2) = 0.007, 0.007 and 0.011; p = 0.002, p = 0.017, p = 0.013).

In summary, the study found that IGD was significantly associated with higher screen exposure. Participants with IGD also reported higher levels of stress, anxiety and depression compared to those without IGD.

Correlation and regression analyses of addictions

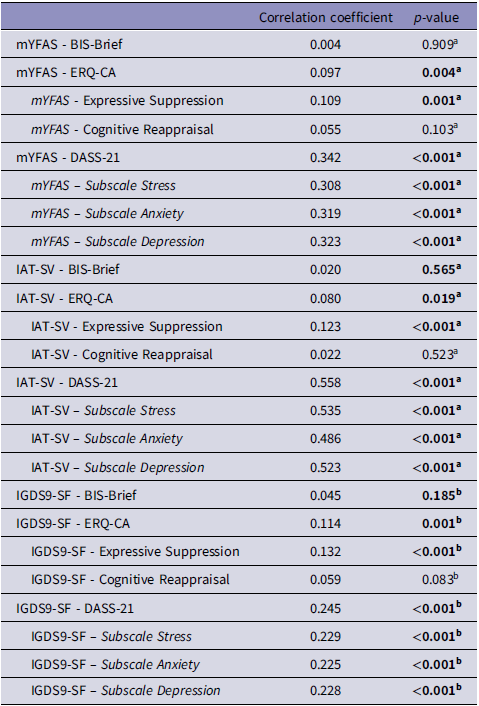

A significant correlation was found between DASS-21 and its subscales and mYFAS, IAT-SV and IGDS9-SF scales. No significant correlation was found between BIS-Brief scores and mYFAS, IAT-SV and IGDS9-SF scales. A significant correlation was found between ERQ-CA and its expressive suppression subscale and mYFAS, IAT-SV and IGDS9-SF scales. Correlations between scale scores are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. The correlation analysis of scales scores with clinical features

Bold data, p < 0.05 (significance).

a Pearson’s correlation test.

b Spearman correlation test.

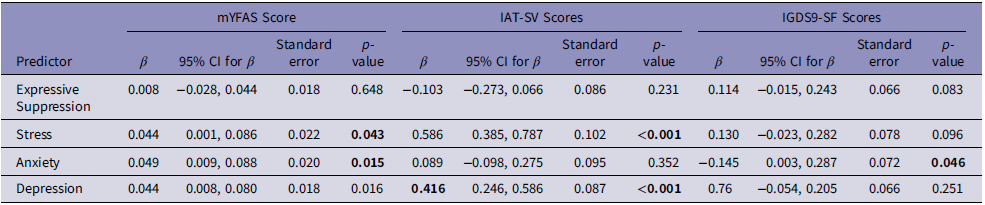

The relationship between the variables predicting each behavioural addiction was examined using a multiple linear regression model. Regression model showed statistical significance for food addiction, PIU and internet gaming disorder (respectively R2 = 0,145, p < 0.001; R2 = 0,317, p < 0.001; R2 = 0,089, p < 0.001). Stress, anxiety and depression subscale scores were statistically significant in predicting food addiction. Stress and depression subscale scores were statistically significant in predicting PIU. Finally, only anxiety subscale scores were statistically significant in predicting internet gaming disorder. The regression models for all three behavioural addiction models are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Multiple linear regression analysis of clinical features predicting the scores of the behavioural addiction scales

Notes: R = 0.381, R2 = 0,145, p < 0.001 for mYFAS; R = 0.563, R2 = 0,317, p < 0.001 for IAT-SV; R = 0.298, R2 = 0,089, p < 0.001 for IGDS9-SF.

mYFAS, the Modified Yale Food Addiction Scale Version 2.0; IAT-SV, short version of Young’s Internet Addiction Test; IGDS9-SF, Internet Gaming Disorder Scale - Short Form.

Bold data, p < 0.05 (significance).

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence Interval; Standard Error, SE.

Discussion

This study examined the prevalence of behavioural addictions such as food addiction, problematic internet use and internet gaming disorder among adolescents and the relationship between these addictions and impulsivity, emotion regulation, depression, anxiety and stress.

Obesity is a significant public health concern, particularly among adolescents. Therefore, it is crucial to implement measures to address food addiction and reduce obesity rates. Research into food addiction among adolescents is a developing area that has received less attention than that given to younger children or adults. A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to examine the prevalence of food addiction in children and adolescents. The study found that the prevalence of FA was 15% (Yekaninejad et al., Reference Yekaninejad, Badrooj, Vosoughi, Lin, Potenza and Pakpour2021). For the Turkish population, this rate was 12.4 % (Dayılar Candan & Küçük, Reference Dayılar Candan and Küçük2019). In our study it was 6.9%, of which 2.2% were severe food addicts. In this study, the prevalence of food addiction was found to be lower, which may be due to regional cultural differences and methodological differences. The study’s findings indicate that young people may be susceptible to developing food addiction (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Sayed, Mostafa and Abdelaziz2016).

Given that behavioural addictions stem from the same underlying mechanisms, their coexistence has been the focus of research studies. Although problematic internet use and eating disorders and attitudes have been investigated in previous studies, the association of FA and PIU has not been sufficiently studied. One of these studies has shown that problematic internet use increases the risk of behavioural addictions such as overeating and pathological gambling (Kuss & Griffiths, Reference Kuss and Griffiths2011). Tang and Koh’s study demonstrated that addiction to social networks can lead to other behavioural addictions, such as those related to food and shopping (Tang & Koh, Reference Tang and Koh2017). Our findings show that PIU is more common in those with FA. It was found that 46.6 per cent of those with FA also had a PIU. There is no information on the frequency of coexistence of FA and PIU in the literature to the best of our knowledge.

Screen exposure is rewarding, so adolescents who are prone to addictive eating may also have higher levels of screen exposure (Domoff et al., Reference Domoff, Sutherland, Yokum and Gearhardt2021). Findings have shown a relationship between daily screen time and FA. Long screen time may be a natural consequence of PIU and IGD. However, it is important to note that PIU is also common in cases of FA, so long screen time in FA may be best explained by this. However, as the current study was cross-sectional, it can solely showed a relationship between food addiction and screen time. The results cannot be used to establish causality. Further prospective studies on this topic are needed.

Adolescents are thought to be more vulnerable to PIU (Cerutti et al., Reference Cerutti, Presaghi, Spensieri, Valastro and Guidetti2016). Previous studies have reported varying prevalence rates of problematic internet use, ranging from 0.8% to 26.7% (D. Kuss et al., Reference Kuss, Griffiths, Karila and Billieux2014). In a systematic review and meta-analysis examining the epidemiology of problematic internet use, PIU was found to be 7.02% (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Chiu and Lin2020). Studies among Turkish adolescents have found PIU rates between 10.1% and 15.1% (Alpaslan et al., Reference Alpaslan, Koçak, Avci and Uzel Taş2015; Şaşmaz et al., Reference Şaşmaz, Öner, Kurt, Yapıcı, Yazıcı, Buğdaycı and Şiş2014). Consistently, 14.3% of the participants were found to be addicted to the internet. Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of IGD ranges from 0.6% to 5.4% worldwide depending on geographical region (Király et al., Reference Király, Griffiths and Demetrovics2015; Rehbein et al., Reference Rehbein, Kliem, Baier, Mößle and Petry2015; Pan et al., Reference Pan, Chiu and Lin2020). Among the Turkish population, 0.96% were found to have an IGD (Evren et al., Reference Evren, Dalbudak, Topcu, Kutlu, Evren and Pontes2018). In this study, the prevalence of IGD was 0.9%. Although the sample consisted of university students, the rate of IGD was found to be similar to our study in the study by Evren et al. (Evren et al., Reference Evren, Dalbudak, Topcu, Kutlu, Evren and Pontes2018).

Several types of addictions, including behavioural addictions (FA, PIU, IGD), have been associated with depression, stress and anxiety, and previous studies have shown that anxiety and depression can lead to addictive behaviours in humans (Parylak et al., Reference Parylak, Koob and Zorrilla2011; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Sayed, Mostafa and Abdelaziz2016; Saikia et al., Reference Saikia, Das, Barman and Bharali2019; Hakami et al., Reference Hakami, Ahmad, Alsharif, Ashqar, AlHarbi, Sayes, Bafail, Alqrni and Khan2021; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Zhang and Zhao2023). In this study, correlational results showed that behavioural addiction was associated with stress, anxiety and depression, which is consistent with previous studies showing that people with high BAs have psychological distress. The cause-and-effect relationship between behavioural dependence and depression, stress and anxiety could not be fully established due to the cross-sectional design of the study. Nevertheless, in this study, it was revealed that depression, anxiety, and stress predicted food addiction. Additionally, depression and stress were identified as predictors for problematic internet use, with anxiety being the sole predictor for internet gaming disorder. Importantly, it was demonstrated that expressive suppression did not predict any form of behavioural addiction. Adolescents may be more prone to overeating when faced with emotional difficulties, and in order to cope with these emotional challenges, they may choose to spend additional time on the internet and engage in extended gaming sessions. This indicates the significance of emotional problems for behavioural addictions.

The internet, which is a behavioural addiction, is used by addicts as a means of avoiding and coping with underlying psychological problems (Rey & Martin, Reference Rey and Martin2006). One study found that participants with higher problematic internet use scores were more likely to report greater difficulties with affective regulation (Mo et al., Reference Mo, Chan, Chan and Lau2018). The prefrontal-limbic circuit, the insula, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the prefrontal areas are involved in the cognitive regulation of emotions and enhance the coupling of limbic and prefrontal areas. When activated, it increases the release of dopamine as well as opiates and other neurochemicals. Chronic use can affect the associated receptors, leading to tolerance or the need for increased stimulation of the reward centre to produce a `high’ and the subsequent characteristic behaviour required to avoid withdrawal symptoms (Herpertz et al., Reference Herpertz, Schneider, Schmahl and Bertsch2018). In the study by Estevez et al., emotion regulation was shown to be a predictive factor for all of the addictive behaviours assessed (Estévez et al., Reference Estévez, Jáuregui, Sánchez-Marcos, López-González and Griffiths2017). Expressive suppression is an emotion regulation strategy involving the conscious, top-down control of reflexive behavioural expressions of emotion (Gross & John, Reference Gross and John2003). Research has shown that people with difficulties in emotion regulation are more likely to engage in addictive behaviours or have difficulty stopping such behaviours (Sayette & Griffin, Reference Sayette and Griffin2004). However, this study found significant correlation between expression suppression and behavioural addiction in the correlation analysis, but it did not predict behavioural addiction in the regression analysis. In the study by Estevez et al., attachment and emotion regulation risk factors in behavioural addiction were studied, while in this current study impulsivity, emotion regulation, depression, anxiety and stress were examined . Estevez et al., conducted a study with a sample of high school and vocational education centre students aged 13–21 years (Estévez et al., Reference Estévez, Jáuregui, Sánchez-Marcos, López-González and Griffiths2017). In contrast, this study only included high school students aged 13–18 years. Therefore, prospective studies on this topic are needed.

Similar to our study, anxiety was found to be important in predicting IGD in the study conducted by Fumero et al. (Fumero et al., Reference Fumero, Marrero, Bethencourt and Peñate2020). Although the measurement tools used for IGD and anxiety in the study of Fumero et al., differed, the sample size and target population were similar to our study. Three hypothetical theoretical models have been proposed to explain the factors involved in IGD (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Cheung and Wang2018). One of these is the comorbidity hypothesis, which relates to the presence of other individual psychological problems or symptoms. The comorbidity hypothesis suggests shared neurobiological and psychological mechanisms between IGD and other substance or behavioural addictions (Gomis-Vicent et al., Reference Gomis-Vicent, Thoma, Turner, Hill and Pascual-Leone2019).

Adolescents should be evaluated for symptoms of behavioural addiction, and special attention should be paid to the manifestation of the following signs: excessive food consumption and prolonged use of the Internet and gaming, despite awareness of the negative consequences. Additionally, factors such as tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, and a reduction in important social or occupational activities should be considered. Given that these symptoms overlap with psychiatric comorbidities in this study, conducting a psychiatric evaluation becomes even more crucial.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. Firstly, it is important to note that our research design is cross-sectional, which means that we cannot establish causality between behavioural addictions and impulsivity, emotion regulation, depression, anxiety, and stress. The sensitivity of behavioural addictions across many cultures may contribute to the low response rate in the study. Additionally, our study sample only consisted of high school students in one province, which may limit the generalisability of our findings to a broader population. In addition, it is important to note that the scales used in our study rely on self-report measures, which may introduce subjective biases.

Conclusion

The increase in internet usage and the accessibility of video games has raised concerns regarding addiction. The results of this study indicate that high prevalence of behavioural addiction, particularly problematic internet use, and its potential association with suppression, depression, stress, and anxiety. In conclusion, it is anticipated that this issue will continue to grow over time. Further research is required to confirm the prevalence and investigate the causal or correlational relationship with emotion regulation, impulsivity, depression, stress, and anxiety. Future studies should include a larger sample size to examine the issue in the general population and across different age groups. Lastly, it is essential to assess the effect of these behavioural addictions on quality of life and functioning to inform appropriate interventions.

Data availability statement

The data are not accessible to the general public because of ethical and privacy concerns. Upon reasonable request, the corresponding author will provide the data supporting the study’s conclusions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all students and relevant participants for their involvement in this study.

Author contributions

İ.Z.: Conceptualisation, Project Administration, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Supervision, Data Curation, Investigation

M.F.T.: Validation, Resources, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Data Curation

M.Ç.: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing

A.K.: Validation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing

Funding statement

No funding was received.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.