Introduction

One remarkable trend of contemporary democracy is the widespread practice of institutional innovation at the local level. Irrespective of region, culture, or economic conditions, renewed models of local democracy have rapidly developed in various countries (Sirianni & Friedland, Reference Sirianni and Friedland2001; Bowler & Donovan, Reference Bowler and Donovan2002; Wezel & Inglehart, Reference Welzel and Inglehart2008). For example, Fung and Wright (Reference Fung, Olin Wright, Fung and Olin Wright2003) described the “empowered participatory governance (EPG) model,” which refers to innovative ways for citizens’ to engage locally. This model has been implemented in neighborhood governance councils in Chicago, the participatory budget system of Porto Alegre in Brazil, and the Panchayat (community council) reforms in West Bengal and Kerala, India. We argue that a central point of these local democracy models is that the self-empowerment of ordinary citizens is crucial for achieving a more meaningful, innovative, and sustainable operation of democracy. In other words, the models commonly emphasize the “process” of individual growth as an autonomous citizen at the grassroots level and presume that the realization of such a process promotes overall political stability, political trust, and institutional efficiency at the upper or state level. Therefore, the local self-empowerment process can be seen as the cornerstone of a virtuous cycle or as the internal driving force of democratic development.

However, many questions remain regarding the effective operation of these models in actual contexts. For example, to what extent can alternative local models contribute to overcoming fundamental obstacles that are widespread at the state or societal level? What factors significantly enhance citizens’ participation in and satisfaction with local democracy models? Lastly, what feasible policies and strategies could be implemented to achieve scaling-up and scaling-out?

In this paper, we examine residents’ self-governance associations (RSAs) in Seoul, South Korea, as an innovative model of local democracy. Specifically, we statistically analyze a survey of all members of RSAs conducted by the Seoul Community Support Center (SCSC) in 2019 and attempt to identify the conditions that significantly enhance the political efficacy of participating citizens. Since its democratization in 1987, South Korea has strived to promote local autonomy and decentralization. In particular, the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) has taken the lead in this endeavor. The case of RSAs in Seoul will shed light on some of the key enabling conditions of local democracy at the metropolitan city level.

The paper consists of five parts. First, we will briefly provide background information and the general characteristics of RSAs in Seoul. Second, the concept of political efficacy and its promoting conditions will be discussed as core issues related to the practical development of local democracy. These are the dependent and independent variables in our research. The third part provides a summary of our research design and the results of the statistical analysis. Finally, we will discuss several important implications arising from the analysis and the challenges that individuals face when seeking to improve the operation of their RSA.

Local Democracy and RSA in the Seoul Metropolis

Local Democracy in Seoul

The metropolitan city of Seoul is divided into 25 districts. Each district has 10 to 27 sub-district communities (dong), and there are 425 communities in total. The average population of these communities is approximately 20,000, and each has its own community center and residents’ autonomous committee (RAC). These committees are generally characterized as a closely connected body of sub-district administrative offices.Footnote 1 Since 2011, SMG has vigorously introduced various new models. A multilevel participatory budgeting system (chamyeo yeasan) was implemented, which includes a city- and district-level decision-making system with some quota to the sub-district level. In 2013, a neighborhood community program (maul gongdongche) that financially supports voluntary establishments of groups of more than three residents was launched. They also initiated pro-active public services providing community centers in 2015 through the chat dong project. Furthermore, participation-oriented community planning projects (mauel gihoeg dan) were introduced in 2016. This project involves a team consisting of approximately 100 voluntary residents who establish a yearly plan for community development at the sub-district level. Thus, the institutional landscape of Seoul’s local democracy has undergone radical changes over the past decade. Indeed, the total number of civic organizations increased almost tenfold in the past 20 years, from 2000 to 2020 (SMG, 2021). During 2012–2020, neighborhood community programs supported 6,702 residents’ groups, and a total of 5281 projects were implemented through the participatory budgeting system (Seoul Democracy Committee, 2020a). The number of citizens participating annually in a participatory budgeting system at the city level was 100,000 to 120,000, representing approximately 1% of the total population of Seoul (Seoul Democracy Committee, 2020b).

During the past decade, SMG has effectively addressed numerous urgent issues and demands through voluntary participation and bottom-up deliberations by residents. Empirical studies also support the positive effects of various types of participation in the South Korean context (Ryu et al., Reference Ryu, Lee and Lee2018; No & Hsueh, Reference No and Hsueh2020). For example, Liu (Reference Liu2023) demonstrated, by adopting the Asian Barometer Survey in 2010 and 2015, that those who participated in nonprofit organizations recorded a higher level of political participation in South Korea. Furthermore, Lee (Reference Lee2010) explained that citizens’ commitment to associations and interactions within their in-group, rather than mere membership, fostered their political participation, such as voting.

Design and Operation of RSAs in Seoul

The RSA concept was introduced in a provisional form with the enactment of the “Special Law on Local Autonomy and Reforming Local Public Administration Systems” in 2013. A principal purpose of this reform is to promote democratic participation and autonomy at the grassroots level (Article 27), as existing RACs are considered ineffective due to their rigid systems. A comprehensive operational plan was developed by each local government at the regional level starting around 2016. SMG took the lead in developing an operational model of an RSA. Its key democratic and institutional features are summarized below.

• Substantial community participation and voluntary formation : The Act mandates the genuine promotion of grassroots self-governance in alignment with the objectives of the RSA. This mandate is contextualized by the historical evolution of existing RSCs, which have transformed into subcontracting entities assisting municipalities in implementing prescribed policies. Although the establishment of RSAs is primarily led by mayors through municipal ordinances, their actual formation is achieved through consultations between local officials and community members.

• Self-governance, representation, and political neutrality: Each RSA consists of approximately 50 voluntary community residents who are elected through sortition from individuals who have completed an educational program on local democracy offered by their metropolitan or district government. Once formed, the association’s representative is elected by its members, and its basic rules are established through an initial plenary meeting as outlined in its articles of association. Each sub-district, known as a dong, has one RSA; therefore, the RSA is a distinct and loosely representative body of the residents within the dong community. In addition, RSA members must maintain political neutrality according to the Article 29 of the Act and local party representatives cannot serve as chairpersons in practice.

• Problem-solving through deliberation and residents’ general meetings (town hall meetings): The RSA establishes several subcommittees that intentionally address pressing issues faced by the community. Solutions are discussed through subcommittees and plenary meetings, and the outcomes are included as an agenda item in the “community development plan” during the residents’ general meeting. All residents in a sub-district have the right to participate in their RSA’s general meeting, which takes place every year. A quorum at the general meeting is typically set at 0.5% to 1% of the total community population.

• Utilization of the resident tax and participatory budgeting system: Budgeting for the community development plan relies on various financial sources. Financial subsidies are provided by the metropolitan and district governments. The allocation process for these funds is integrated into the participatory budgeting system at the district level. In addition, the SMG returns to each RSA the tax amount paid by their residents for discretionary use. In other words, an innovative “democracy of finance” is implemented at Seoul’s RSAs.

• Public–private partnerships: RSAs receive not only financial support from district and metropolitan governments but also administrative support from district and city governments for their formation and operation processes. The district government operates a special support team (jiwon dan) at the district level and designates one special support staff member (jiwon gwan) to practically support one or two RSAs. In addition, the SMG established intermediary community support centers in each district to provide various forms of administrative support to the RSAs.

The average operational results of 26 RSAs during 2017–2018 were as follows. Membership amounted to 45.4 residents with 61% female and 39% male. Among the members, 19.9% were former members of a RAC, while 23.5% had no experience in any local democracy model or project. Regarding the background of participation, 56.6% became aware of the RSA through promotional efforts and explanations provided by special support staffs. Another 16.9% were encouraged to participate through invitations from family or acquaintances (SCSC, 2019). As results, 209.6 residents participated in general meetings, representing approximately 2.4% of the total population in these communities. The general meetings passed 8.6 agenda items by a majority vote and allocated approximately 58 million Korean won for implementation. The major fields of agenda items include complex agenda items (37%), culture and the arts (22%), infrastructure and community beautification (21%), living environment security (18%), and education and childcare (17%) (SCSC, 2019).

Political Efficacy and Its Promoting Conditions

In this research, we focus on the self-empowerment of citizens participating in local democracy. From an analytical perspective, this research agenda holds strong theoretical relevance to the concept of political efficacy, which has been widely discussed in political science. The concept was originally defined by Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Gurin and Miller1954, 187) as the “feeling that political and social change is possible and that the individual citizen can play a part in bringing about this change.” By applying the original definition to the recent discussion on local democracy models, the concept of political efficacy in a local context can be more strictly reinterpreted as “the residents’ feeling that local political and social change is possible and that they can play a part in bringing about this change.”

However, relatively few studies have investigated the causes and conditions of local political efficacy (Grillo et al., Reference Grillo, Teixeira and Wilson2010; Geissel & Hess 2017). Some studies have even raised suspicions and highlighted the limitations of local political efficacy. For example, Dyck and Lascher (Reference Dyck and Lascher2009) assessed how, in some cases, participatory institutions such as referendums in the USA did not have a direct effect on the political efficacy of participating residents. Kahne and Westheimer (Reference Kahne and Westheimer2006) emphasized that certain participatory programs actually decreased participants’ political efficacy when they encountered significant real-world barriers. Further research is still needed to provide a more detailed explanation of the mechanisms and strategies to enhance local political efficacy. In this paper, based on an extensive review of relevant literature, we hypothesize the following enabling conditions and factors of local political efficacy: 1) socioeconomic factors, 2) cultural factors (specifically considering social capital), 3) process factors, and 4) institutional factors. These factors encompass not only the primary elements frequently examined in the aforementioned research but also those addressed in subsequent studies on local democracy, civic participation, and citizen empowerment from a comprehensive perspective. These factors are believed to promote citizens' political efficacy through intrinsic and extrinsic, normative and artificial, preliminary and practical influences and mechanisms. Although systematically organizing these factors presents considerable challenges, each holds significant theoretical importance and cannot be disregarded. Therefore, it is essential for efficacy research to meticulously investigate how these factors specifically function within real-world contexts.

First, the socioeconomic status (SES) of individuals, such as their education and income level, can determine their political efficacy (Mattei & Niemi, Reference Mattei, Niemi, Best and Radcliff2005; Verba & Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972). Existing studies commonly argue that a combination of wealth, education, and power leads to the formation of political classes with a higher level of political efficacy and participation. Other studies have also argued that SES was one of the primary determinants of civic engagement (Antoci et al., Reference Antoci, Sabatini and Sodini2013). In local democracy models, SES can be seen as a prerequisite for local political efficacy at the individual or regional level.

Second, social capital, defined as “features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” (Putnam, Reference Putnam1995, 67), can promote civic engagement (Grillo et al., Reference Grillo, Teixeira and Wilson2010; Kim, Reference Kim2020; Putnam, Reference Putnam1995). In local democracy models, the assumption of social capital can also take multilevel forms: 1) communities or regions with higher social capital, such as a greater number of civic organizations that can foster increased civic engagement, and 2) individuals with higher social capital, such as positive trust with others or extensive experience with reciprocal activities, tend to participate more actively and positively. Social capital, in terms of social trust and norms of reciprocity, will positively affect political efficacy. Individuals and regions with a higher level of social capital can better address collective action problems in local democracy. Arguably, Putnam’s study on Italy suggests that “making democracy work” in northern Italy was largely attributed to the region’s elevated level of political efficacy, which can be linked to its higher level of social capital (Putnam, Reference Putnam1995).

Third, the experience of participation at the local level matters. Existing studies indicate that participation is a learning process, where the continued and deepening engagement of individuals can result in an increased level of political efficacy. The educational effects of participation are at the core of participatory democracy (Pateman, Reference Pateman1970). The “empowered involvement of ordinary citizens and officials” and the “process of reasoned deliberation” among them regarding specific problems are the fundamental political principles of the EPG model by Fung and Wright (Reference Fung, Olin Wright, Fung and Olin Wright2003). Ansell and Gash (Reference Ansell and Gash2008, 557–561) also examined the collaborative process among all stakeholders as a central mechanism of their collaborative governance model. According to them, the cyclical process of involvement and communication among actors is the core of collaborative governance. This process typically involves 1) face-to-face dialogue, 2) trust-building, 3) mutual commitment (such as mutual recognition, sharing ownership, and seeking mutual gain), 4) shared understanding, and 5) intermediate achievements. In other words, actors' substantial commitment to endogenous processes, such as the participatory, collaborative, voluntary, and devoted operation of local democracy models, can be seen as a virtuous process. The process can help strengthen their political efficacy, and when combined, can empower citizens, eventually promoting the success of collaborative governance.

Fourth, existing studies of local democracy models also focus on various institutional conditions. For example, the EPG model can be promoted through: 1) devolving power to local units, 2) centralized supervision and coordination of local units by superordinate bodies, and 3) utilizing official state power and resources for local unit projects (Fung & Wright, Reference Fung, Olin Wright, Fung and Olin Wright2003, 20–23). The collaborative governance model is influenced not only by the starting conditions (power-resource-knowledge asymmetries and the prehistory of cooperation or conflict affecting the initial trust level) but also by the institutional design (participatory inclusiveness, forum exclusiveness, clear ground rules, and process transparency) and facilitative leadership (various forms and quality levels of facilitative leadership depending on the specific context (Ansell & Gash, Reference Ansell and Gash2008, 550–557). These studies all emphasize that institutional conditions are crucial in local democracy. In particular, they indicate that institutional support provided by the government can help promote citizens’ motivation and capacity for political engagement, leading to a higher level of political efficacy.

Based on the above arguments and the review of existing studies, we have formulated the following four groups of hypotheses. These hypotheses have been systematically reconstructed with specific consideration of our analytical target. Specifically, H1 and H2 are relevant to SES and social capital arguments, respectively. In addition, we consider both individual and regional (district) levels in the analysis of these hypotheses because the theoretical effects and explanations of SES and social capital may vary between these two levels. H3 and H4 are relevant to the process and institutional conditions. They are reconstructed specifically to incorporate realistic as well as potential endogenous and exogenous conditions of RSA.

H1 Residents with stronger socioeconomic backgrounds are likely to have higher political efficacy.

H2-1 Residents with higher levels of social capital at the district level are likely to have higher political efficacy.

H2-2 Residents with higher levels of social capital at the RSA level are likely to have higher political efficacy.

H3-1 Residents who participate more in and acknowledge the importance of RSA are likely to have higher political efficacy.

H3-2 Residents who have a more positive evaluation of the formation, collaboration, and empowerment processes of RSA are likely to have higher political efficacy.

H4-1 Residents who have higher evaluations of public–private partnerships for deciding on and operating community development plans are likely to have higher political efficacy.

H4-2 Residents who have higher evaluations of support from special staff and district special support teams are likely to have higher political efficacy.

Research Design and Data

This research analyzes a survey titled “Satisfaction Investigation of 2019 Seoul RSA Exemplary Cases” to investigate the impact of the RSA process, social capital, public–private partnerships, personal attributes, and district backgrounds on the satisfaction and political efficacy of RSA members. SCSC, an intermediary support organization established by the SMG, collected survey data from 1319 citizens, which accounted for 65.9% of the total 2000 participants in RSA in 2019. The citizens were those who had experience as members of 81 RSAs in 15 districts during the first and second waves of implementation from 2017 to 2019. A total of 385 surveys were collected out of 650 participants in the first wave, and 934 out of 1350 in the second wave. SCSC collected data through a mobile survey (SCSC, 2019). Data at the district level, including levels of volunteer activity, NGO presence, trust, income, and education, was sourced from the Ministry of Interior and Safety. There is no missing data at the RSA and district levels. Given the potential challenges associated with survey analysis, such as social desirability bias and self-reporting bias, this study aims to explore the correlations among variables collected through the survey.

The survey mainly consists of questions about the level of satisfaction with participation in the RSA, community support policies, community development efforts, and private–public partnerships. Our dependent variables focus on political efficacy when participating in the RSA. To analyze political efficacy, our study includes questions, “Would the benefits of the RSA’s community development plan primarily reward most of the residents?” “Has the RSA helped with neighborhood consensus building?” Participants were asked to rate their satisfaction on a five-point Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1: very unsatisfied; 2: unsatisfied; 3: neither satisfied nor unsatisfied; 4: satisfied; 5: very satisfied). As discussed in the theory section, local political efficacy refers to residents' feelings that they play a role in bringing about meaningful social change. Local political efficacy can be established and enhanced through community planning, problem-solving, or consensus building within residents’ self-governing institutions. Understanding these variables, we can analyze how each factor is associated with local political efficacy.

As discussed in the theoretical framework, our analysis includes two levels of independent variables: the RSA level and the district level. RSA-level variables consist of four sub-components: the participation process, social capital, public–private partnerships, and personal characteristics (gender and age). District-level variables measure volunteer activities, the number of nonprofit organizations, trust in the neighborhood, and income and education levels.

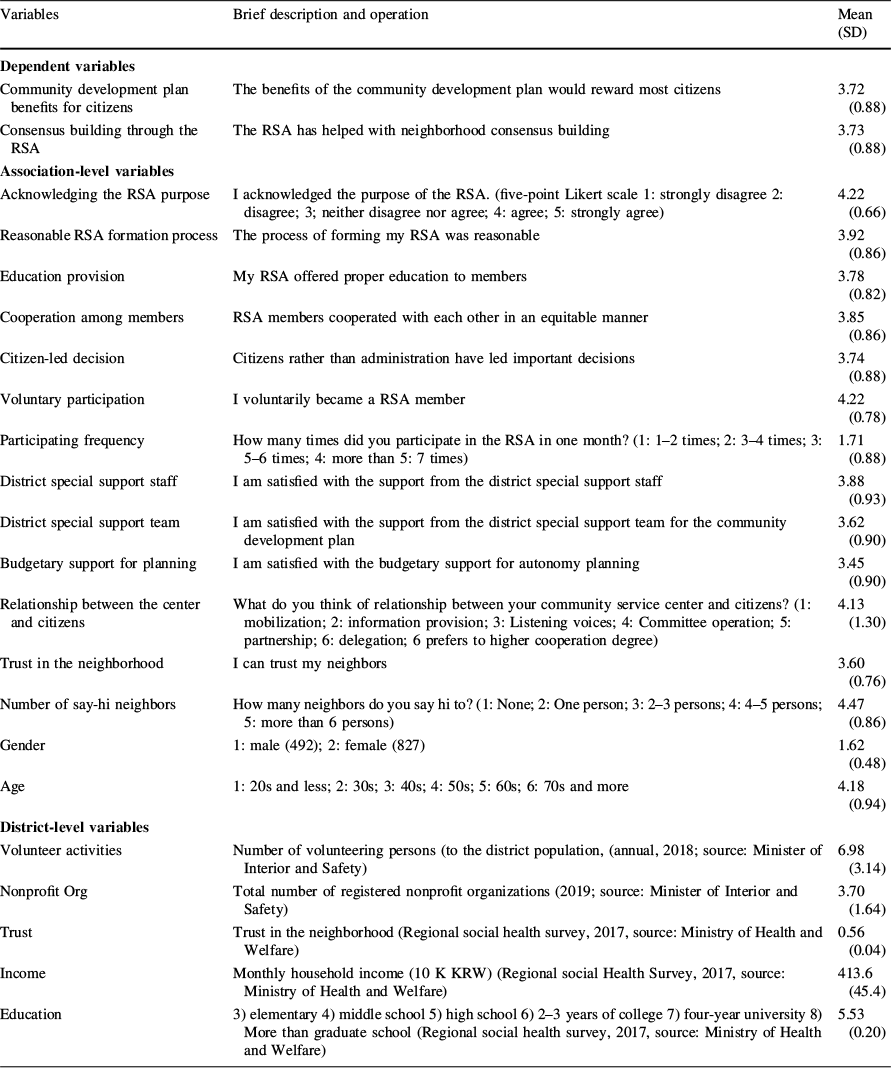

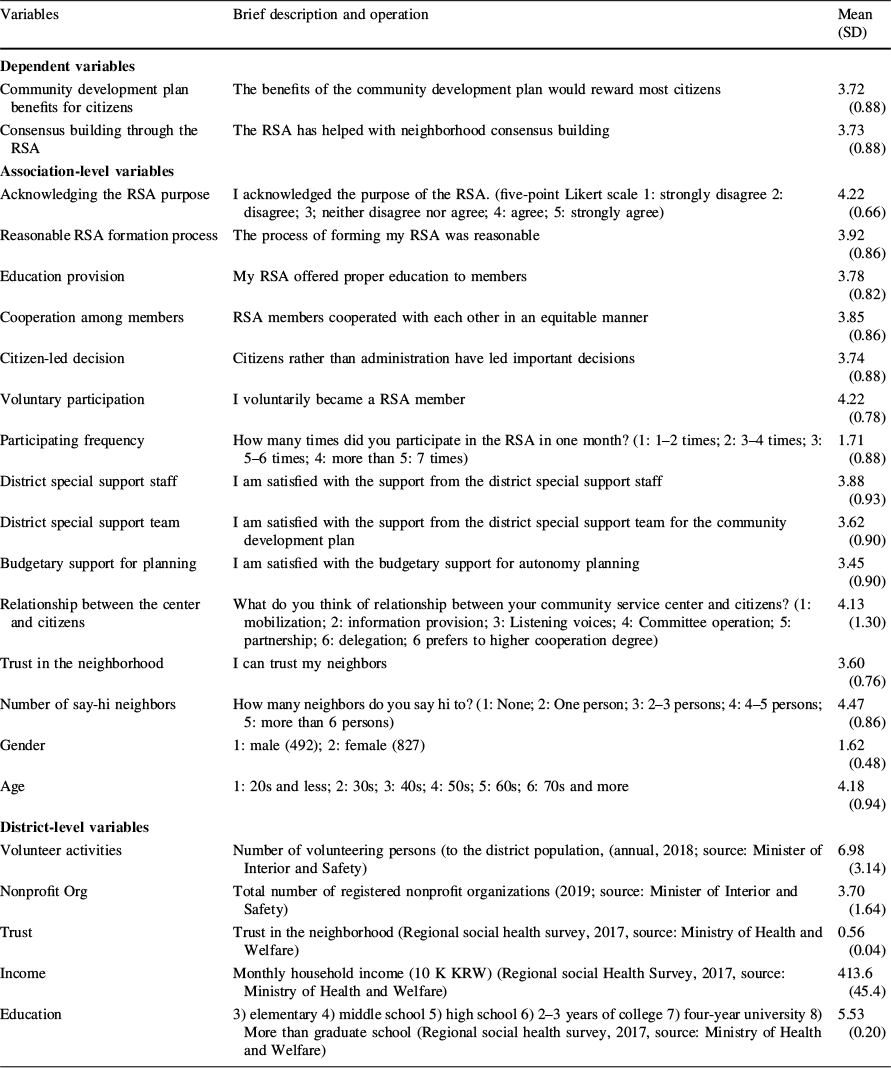

The independent variables are divided into the following four categories, corresponding to the four groups of hypotheses described above. The first category of hypotheses includes two key variables related to SES. The income variable measures monthly household income, while the education variable categorizes education levels as follows: 3) elementary, 4) middle school, 5) high school, 6) 2–3 years of college, 7) four-year university, and 8) graduate school or higher (Table 1).

Table 1 Variable description and descriptive statistics

Variables |

Brief description and operation |

Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

Dependent variables |

||

Community development plan benefits for citizens |

The benefits of the community development plan would reward most citizens |

3.72 (0.88) |

Consensus building through the RSA |

The RSA has helped with neighborhood consensus building |

3.73 (0.88) |

Association-level variables |

||

Acknowledging the RSA purpose |

I acknowledged the purpose of the RSA. (five-point Likert scale 1: strongly disagree 2: disagree; 3; neither disagree nor agree; 4: agree; 5: strongly agree) |

4.22 (0.66) |

Reasonable RSA formation process |

The process of forming my RSA was reasonable |

3.92 (0.86) |

Education provision |

My RSA offered proper education to members |

3.78 (0.82) |

Cooperation among members |

RSA members cooperated with each other in an equitable manner |

3.85 (0.86) |

Citizen-led decision |

Citizens rather than administration have led important decisions |

3.74 (0.88) |

Voluntary participation |

I voluntarily became a RSA member |

4.22 (0.78) |

Participating frequency |

How many times did you participate in the RSA in one month? (1: 1–2 times; 2: 3–4 times; 3: 5–6 times; 4: more than 5: 7 times) |

1.71 (0.88) |

District special support staff |

I am satisfied with the support from the district special support staff |

3.88 (0.93) |

District special support team |

I am satisfied with the support from the district special support team for the community development plan |

3.62 (0.90) |

Budgetary support for planning |

I am satisfied with the budgetary support for autonomy planning |

3.45 (0.90) |

Relationship between the center and citizens |

What do you think of relationship between your community service center and citizens? (1: mobilization; 2: information provision; 3: Listening voices; 4: Committee operation; 5: partnership; 6: delegation; 6 prefers to higher cooperation degree) |

4.13 (1.30) |

Trust in the neighborhood |

I can trust my neighbors |

3.60 (0.76) |

Number of say-hi neighbors |

How many neighbors do you say hi to? (1: None; 2: One person; 3: 2–3 persons; 4: 4–5 persons; 5: more than 6 persons) |

4.47 (0.86) |

Gender |

1: male (492); 2: female (827) |

1.62 (0.48) |

Age |

1: 20s and less; 2: 30s; 3: 40s; 4: 50s; 5: 60s; 6: 70s and more |

4.18 (0.94) |

District-level variables |

||

Volunteer activities |

Number of volunteering persons (to the district population, (annual, 2018; source: Minister of Interior and Safety) |

6.98 (3.14) |

Nonprofit Org |

Total number of registered nonprofit organizations (2019; source: Minister of Interior and Safety) |

3.70 (1.64) |

Trust |

Trust in the neighborhood (Regional social health survey, 2017, source: Ministry of Health and Welfare) |

0.56 (0.04) |

Income |

Monthly household income (10 K KRW) (Regional social Health Survey, 2017, source: Ministry of Health and Welfare) |

413.6 (45.4) |

Education |

3) elementary 4) middle school 5) high school 6) 2–3 years of college 7) four-year university 8) More than graduate school (Regional social health survey, 2017, source: Ministry of Health and Welfare) |

5.53 (0.20) |

Analysis and Results

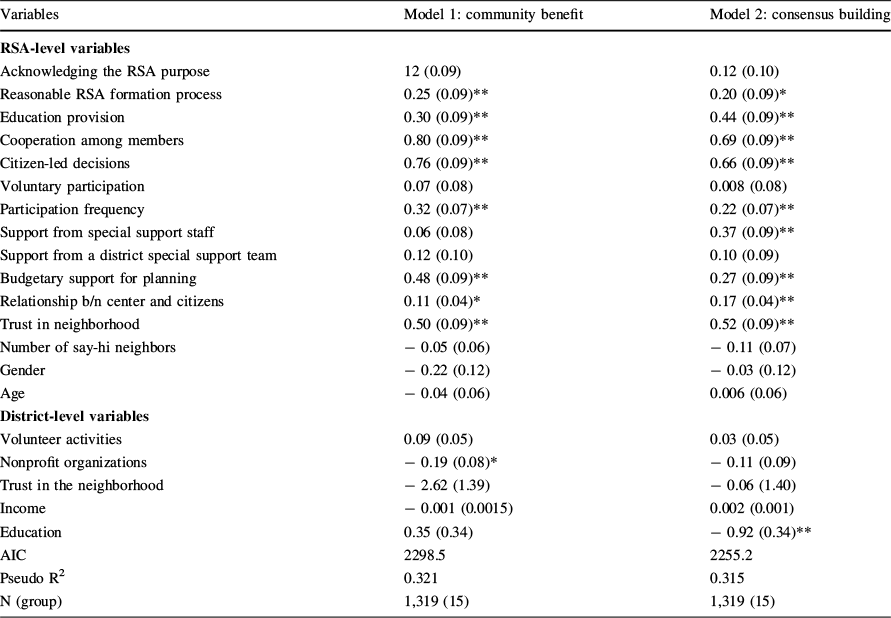

We conducted a multilevel ordered-logit analysis to test our hypotheses. Our RSA-level survey data are typically influenced by data from higher-level variables. A multilevel model, with two levels in this case, is the appropriate method to analyze these RSAs, as they are nested within their respective districts. In addition, due to the ordinal attributes of our dependent variables, we utilize an ordered logit model. Our analytical strategy involves initially analyzing the data at the RSA level and subsequently at both the RSA and district levels to assess the association of the two-level variables with our dependent variables. We also evaluate two distinct attributes of political efficacy: the role of RSAs in consensus building and community benefits. Although the complexity and space constraints may prevent testing every cluster of hypotheses using these model specification strategies, this analysis rigorously examines two different dependent variables across two levels (RSA and district) in a systematic and step-by-step manner. The model specification is primarily based on theoretical considerations. We also provide a path model and Heckman selection model outcomes, considering potential theoretical connections between variables and endogeneity in the Appendix 1 and 2.

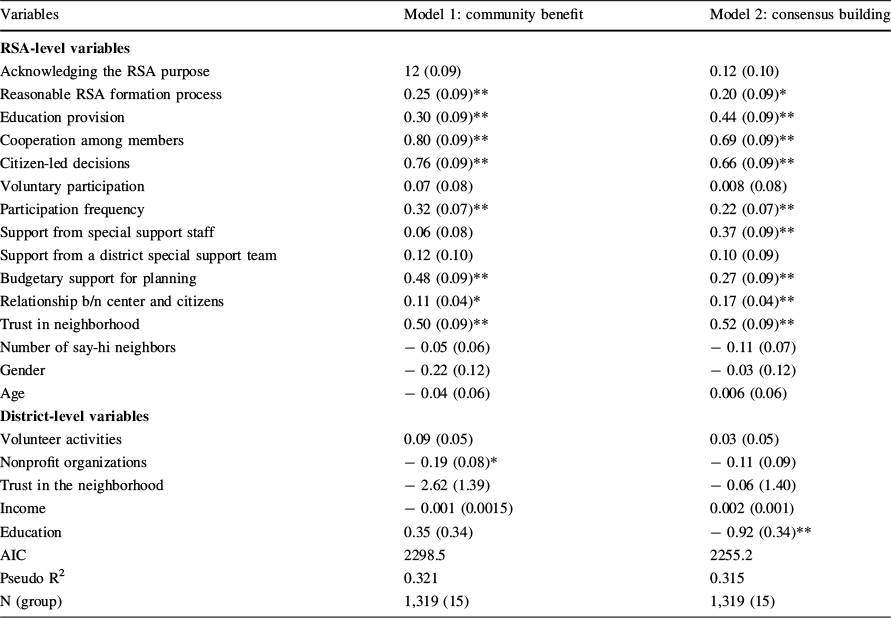

In addition, to avoid the issue of multicollinearity, we conducted a correlation test. Most of the Pearson correlation coefficients of the independent variables are less than 0.4, indicating that multicollinearity issues are not significant. Furthermore, the mean variance inflation factor (VIF) is 1.64, which is less than 5, indicating a low level of multicollinearity. As an additional robustness check to account for measurement errors in explanatory variables, the Delgado and Mantiga test for Model 1 resulted in rejecting the null hypothesis of no measurement error, with a p-value of 0.10 (Lee and Wilhelm, Reference Lee and Wilhelm2020). Additionally, we conducted a robustness check by investigating common source bias, considering that both the dependent and independent variables are derived from the same survey. The percentage of variance explained in Harman's single-factor test is 32.5%, indicating a low likelihood of contamination by common source bias in the analyzed variables. Models 1 and 2 in Table 2 examine the association between our driving factors and overall satisfaction with the RSA at the RSA level and both at the RSA and district levels, respectively. AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) indicates that Model 2, which includes district-level variables, shows a slightly better fit to the data than Model 1. Pseudo R2 values for Models 1 and 2 indicate that 30.9 percent and 31.4 percent, respectively, of the variation in the dependent variables can be explained by the independent variables. To assess potential model specification errors, such as the omission of relevant variables or the inclusion of irrelevant ones, we conducted a specification link test comparing Model 1 and Model 2. The squared predictions exhibited no explanatory power, with statistically insignificant p-values of 0.212 and 0.134 for Model 1 and Model 2, respectively. This suggests that both models are appropriately specified.

Table 2 Multilevel modeling output on participation satisfaction

Variables |

Model 1: community benefit |

Model 2: consensus building |

|---|---|---|

RSA-level variables |

||

Acknowledging the RSA purpose |

12 (0.09) |

0.12 (0.10) |

Reasonable RSA formation process |

0.25 (0.09)** |

0.20 (0.09)* |

Education provision |

0.30 (0.09)** |

0.44 (0.09)** |

Cooperation among members |

0.80 (0.09)** |

0.69 (0.09)** |

Citizen-led decisions |

0.76 (0.09)** |

0.66 (0.09)** |

Voluntary participation |

0.07 (0.08) |

0.008 (0.08) |

Participation frequency |

0.32 (0.07)** |

0.22 (0.07)** |

Support from special support staff |

0.06 (0.08) |

0.37 (0.09)** |

Support from a district special support team |

0.12 (0.10) |

0.10 (0.09) |

Budgetary support for planning |

0.48 (0.09)** |

0.27 (0.09)** |

Relationship b/n center and citizens |

0.11 (0.04)* |

0.17 (0.04)** |

Trust in neighborhood |

0.50 (0.09)** |

0.52 (0.09)** |

Number of say-hi neighbors |

− 0.05 (0.06) |

− 0.11 (0.07) |

Gender |

− 0.22 (0.12) |

− 0.03 (0.12) |

Age |

− 0.04 (0.06) |

0.006 (0.06) |

District-level variables |

||

Volunteer activities |

0.09 (0.05) |

0.03 (0.05) |

Nonprofit organizations |

− 0.19 (0.08)* |

− 0.11 (0.09) |

Trust in the neighborhood |

− 2.62 (1.39) |

− 0.06 (1.40) |

Income |

− 0.001 (0.0015) |

0.002 (0.001) |

Education |

0.35 (0.34) |

− 0.92 (0.34)** |

AIC |

2298.5 |

2255.2 |

Pseudo R2 |

0.321 |

0.315 |

N (group) |

1,319 (15) |

1,319 (15) |

Standardized coefficient; standard errors are in parentheses, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Model 1 and Model 2 in Table 2 present the analysis results of the political efficacy variables. We tested two hypotheses regarding the extent to which the plan would provide benefits to most community residents (community benefit) and whether the association aided in consensus building among community residents (consensus building). Among the RSA process variables, individuals who are more satisfied with a reasonable RSA formation process, adequate educational support, and citizen-led decisions are more likely to indicate higher values for both community benefit and consensus-building variables. The variable for proper education provision is statistically significant and positively associated with community benefits and consensus building. The frequency of participation, rather than voluntary participation, is positively associated with the variable of political efficacy. For public–private partnership variables, support from the community administrative team and a higher level of budget support likely lead to increased political efficacy. As discussed in the theoretical framework, adequate budgetary support and collaboration with municipal administration are crucial for improving political efficacy. As predicted by the hypothesis, trust in the neighborhood is one of the key factors driving higher levels of political efficacy. Compared to trust at the district level, trust within the neighborhood explains higher levels of community benefits and consensus building.

The second category of hypotheses is related to social capital. Participants answered two questions: “I trust my neighbors” (on a five-point Likert scale) and “How many neighbors do you say hello to?” This question referred to neighbors with whom they have a friendly relationship in their community, excluding family, workplace colleagues, and friends who live in another community. Answers are coded as follows: 1: none; 2: one person; 3: 2–3 people; 4: 4–5 people; and 5: more than 6 people. We also controlled for gender (1: male (492 persons); and 2: female (827 persons)) and age (1: 20s and younger; 2: 30s; 3: 40s; 4: 50s; 5: 60s; 6: 70s and older). For the district-level variables, we include the extent of volunteer activities, presence of nonprofit organizations, and the level of trust in the neighborhood. Participants are exposed to the upper (in this case, district-level) civic culture and social trust. Thus, we control for the number of volunteer activities within the district population as a measure of the level of volunteer participation. The number of nonprofit organizations in the district is a measure of the strength of nonprofit civil society organizations. Trust in neighbors is measured using the same survey question that is used at the district level.

The third category of hypotheses pertains to the participation process at the RSA level. This includes acknowledging the purpose of the RSA, voluntary participation, a reasonable formation process of the RSA, and proper educational provisions. Participation process variables also include the frequency of participation in an RSA per month, cooperation among RSA members (RSA members cooperating with each other in an equitable manner), and citizen-led decisions (citizens, rather than the administration, leading important decisions).

The fourth category of hypotheses pertains to a set of questions concerning the institutional conditions of the RSA. Specifically, public–private partnerships for deciding on and operating the community development plan, and support from the administration, are important institutional design factors of the RSA. When creating a community development plan, collaboration between citizens and the local administration is critical. This category includes the satisfaction level with support provided by specialized staff assigned by the district, support offered by a dedicated support team from the district, and budgetary support for planning. It is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. The survey also investigated the relationship between the community service center and citizens using ordinal scales as follows: 1. mobilization; 2. information provision; 3. listening to voices; 4. operational committee; 5. partnerships; and 6. authority delegation.

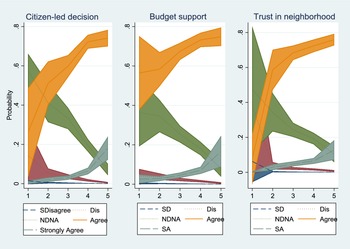

Figure 1 presents the predicted probability of the ordered logit model, illustrating the relationships among the community benefits of the determined plan, citizen-led decisions, budgetary support, and trust in the neighborhood. This finding is consistent with the ordered logit results of Model 1 in Table 2. Individuals who express higher satisfaction with the citizen-led decision process are more inclined to provide “agree” and “strongly agree” responses regarding community benefits as a political efficacy indicator. Similar to the predicted probability for citizen-led decisions, budgetary support also confirms our hypothesis regarding the impact of public–private partnerships as an institution on the community benefit aspect of political efficacy. The likelihood of choosing “Neither disagree nor agree” decreases among individuals who are more satisfied with the budgetary support for the community development plan. The predicted probability for trust in the neighborhood also supports our main argument on social capital. The percentage of those who reported a higher level of trust in the neighborhood is significantly higher among respondents who indicated “agree” or “strongly agree” with the community benefits of the determined plan. In summary, predicted probability plots (Fig. 1) illustrate that citizen-led RSA processes, supportive relations between local government and RSA, and trust as a form of social capital can contribute to elevating the political efficacy of RSA participants.

Fig. 1 Probability of political efficacy (community benefits)

Discussion

First, contrary to the widely accepted claim that citizens’ education and income level can determine their political efficacy (Antoci et al., Reference Antoci, Sabatini and Sodini2013; Mattei & Niemi, Reference Mattei, Niemi, Best and Radcliff2005; Verba & Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972), socioeconomic status (SES) demonstrated relatively low relevance in the case of Seoul. This implies that the development of local political efficacy and the success of local democracy are not structurally predetermined by socioeconomic conditions. We will need to consider cultural, voluntaristic, and institutional factors to fully understand the enabling conditions for local political efficacy.

Secondly, social capital, particularly trust in neighbors, also positively influences political efficacy. But, the perception of trust in close neighbors (at the RAS level) rather than in the broader neighborhood (at the regional level) better explains the level of political efficacy. This result seems to be in line with Putnam's theoretical development of social capital. While his study on Italy emphasized that social capital, as a historically shaped cultural template at the regional level, determined the development of democracy in Italy (Putnam, Reference Putnam1993), he illustrated in a more universal way that local democracy could be developed in various places by constructing and enhancing social capital at the local level within a relatively short time period (Putnam, Reference Putnam1999, Reference Putnam2003). In Bowing Alone, he even calls for strategies of social capitalists, indicating the malleable and constructible nature of social capital. Our study also indicates that trust in close neighbors or face-to-face trust-building among residents at the unit level is important for enhancing local political efficacy.

Third, this study has provided evidence suggesting that collaborative and empowering processes at the unit level are crucial for enhancing the political efficacy of community benefits and consensus building. The citizen-led decision-making process and cooperation among members of voluntary organizations demonstrate a strong relevance to political efficacy. In addition, there is a relatively strong correlation between the process of forming reasonable RSAs and the frequency of participation. Also, these process factors are supported or enhanced by the institutional and cultural factors (refer to the path model in the Appendix). The dynamic structure of local political efficacy supports the common ground of a voluntaristic and artefactual nature in existing local democracy models such as the EPG model, collaborative governance model, and associative democracy (Ansell & Gash, Reference Ansell and Gash2008; Cohen & Rogers, Reference Cohen and Rogers1995; Fung & Wright, Reference Fung, Olin Wright, Fung and Olin Wright2003).

Fourth, institutional factors had a varied impact on political efficacy. While budgetary support from the government and direct support for staff and educational programs provided at the unit level have a strong or relatively strong effect, indirect support for staff provided at the SMG level and the relationships between SMG support centers and citizens showed relatively low relevance. This finding has policy implications for designing institutional interventions to support local democracy, which will be briefly discussed in the conclusion section.

Conclusion

Nurturing civil society and voluntary organizations is often seen as a virtue for democracy. Participation in grassroots organizations is expected to enhance democracy. However, little is known about how and to what extent citizens’ participation in such associations affects their political efficacy. Our study raised a question about the conditions under which citizens perceive political efficacy when they join local self-governance associations. We investigated the relationships between perceived political efficacy and socioeconomic conditions, social capital, participatory processes, and institutional support. The study discussed various effects, relevance to existing studies, and ways to enhance citizens' political efficacy. Contrary to common assumptions, socioeconomic preconditions are not necessarily associated with the level of local political efficacy in our case. Trust in close neighbors at the unit level, rather than a broad cultural template at the regional level, significantly enhances political efficacy. Process factors, experienced directly by citizens at the unit level, play a crucial role. Various forms of policy and institutional intervention have diverse effects. Budgetary support is vital without a doubt. The staff and educational programs offered at the unit level seem to be more effective in enhancing local political efficacy compared to the staff and support center provided by the SMG at higher levels of government.

One practical policy implication of this study is that interventions aimed at enhancing local political efficacy should be tailored to promote and strengthen bottom-up participatory processes within grassroots associations. For example, the realistic logic that community-based social capital and bottom-up participation structures enhance citizens’ sense of political efficacy can be found in the following interview with RSA participants. “I felt particularly rewarded by being able to deepen my connections with the community people through my involvement in the RSA. The association is full of smart and good-hearted people, including a truly righteous local gentleman. Becoming friends with these neighbors and chatting with them on the streets has made me feel genuinely happy.” “The purpose of RSA is to build a community. To create a community, there must be social connections within it. Through self-governance activities, I came to feel the necessity of these connections and a sense of pride in them. Although we may not have significant influence, we make every effort to address residents' concerns by sincerely collaborating with the administration.”Footnote 2 Thus, to enhance participation in and ensure the sustainability of RSA, it is imperative to develop policies that emphasize community-based approaches fostering direct, face-to-face interactions, rather than relying solely on abstract notions of civil society or democracy.

It is also important to note that among different forms of institutional support, staff and education programs provided at the unit level are more effective than indirect support provided at the SMG level. Budget matters significantly, but it is advisable for the government to develop less intrusive and more participatory measures in collaboration with citizens. Through further interviews with RSA participants, this point is confirmed: regardless of the amount, when citizens take the lead in managing the community budget, it fosters their sense of civic responsibility. “RSA members approach the use of resident taxes very sensitively because the residents are watching. We feel the burden and responsibility of using the funds properly and ensuring that all residents benefit. Therefore, we carefully gather and consider the opinions of the residents.”Footnote 3 This approach could help establish a more sustainable and synergistic foundation for local political efficacy.

Future research could systematically examine other remaining questions, such as why some individuals join RSAs, while others do not, and whether and to what extent a higher level of political efficacy leads to democratic and effective outcomes. While it would be challenging to measure actual “community benefits” and “consensus building,” exploring the connection between political efficacy and community-level outcomes could provide valuable insights for understanding the roles of citizens and grassroots organizations in local democracy and governance. In this regard, conducting comparative studies with a broader geographical perspective and more detailed context-specific case analysis of RSAs in Seoul will help address the limitations of this paper.

Most importantly, we will need to conduct a more in-depth case study or a future longitudinal study exploring the potential bidirectional relationship between political efficacy and citizens’ perceptions of the RAS process, including participation, support, and partnership. Based on our findings, we argue that residents’ evaluation of the participatory processes, public–private partnership, and support from special staff and district special support teams affects their political efficacy: the residents believe that local political and social change is possible and that they can contribute to this change. While not inherently tautological, there are potentially bidirectional relationships or complex interplay between political efficacy and the residents’ evaluation of various aspects of RSA. For example, residents with a higher level of political efficacy may have a more positive evaluation of the RSA process. Regarding this intriguing question, we suspect that there could be a virtuous or vicious circle of learning, where newly initiated members’ learning experience with various aspects of RSA could either positively or negatively affect their sense of political efficacy. However, this remains, for now, a hypothesis to be explored in a future study.Footnote 4

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by KEITI (Korea Environmental Industry & Technology Institute) RS-2023-00221109 and RS-2024-00469807 and University Innovation Center, Seoul National University.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Seoul National University.

Declarations

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix 1: Path model (model 3): the effects of socioeconomic variables, participation, and political efficacy (community benefits)

Where d1: gender, d2: age, q17r4: trust, q4r1: participation, q4r3: Reasonable RSA formation, q21: Relationship between the center and citizens, q6r6: community benefit.

A path modeling presents how socioeconomic variable such as gender, education, and social capital may be associated with participation, which lead to evaluation on RSA then to political efficacy. Trust has a positive effect on participation (β = 0.15, p <0.01), indicating the more trust in the community, the more likely will the person engage in RSA activities. Political efficacy is the function of reasonable RSA formation (β = 0.48, p <0.01), better relationship between the community support center and citizen (β = 0.15, p <0.01), and participation (β = 0.06, p <0.01).

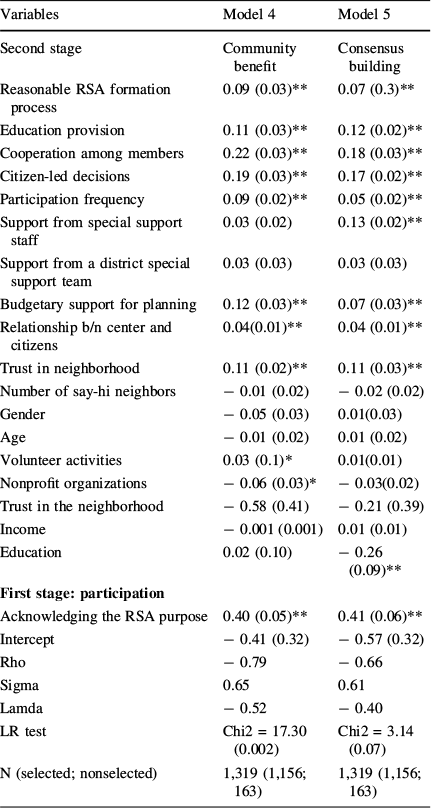

Appendix 2: Heckman selection model: the selective effect of participation on political efficacy

Variables |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

|---|---|---|

Second stage |

Community benefit |

Consensus building |

Reasonable RSA formation process |

0.09 (0.03)** |

0.07 (0.3)** |

Education provision |

0.11 (0.03)** |

0.12 (0.02)** |

Cooperation among members |

0.22 (0.03)** |

0.18 (0.03)** |

Citizen-led decisions |

0.19 (0.03)** |

0.17 (0.02)** |

Participation frequency |

0.09 (0.02)** |

0.05 (0.02)** |

Support from special support staff |

0.03 (0.02) |

0.13 (0.02)** |

Support from a district special support team |

0.03 (0.03) |

0.03 (0.03) |

Budgetary support for planning |

0.12 (0.03)** |

0.07 (0.03)** |

Relationship b/n center and citizens |

0.04(0.01)** |

0.04 (0.01)** |

Trust in neighborhood |

0.11 (0.02)** |

0.11 (0.03)** |

Number of say-hi neighbors |

− 0.01 (0.02) |

− 0.02 (0.02) |

Gender |

− 0.05 (0.03) |

0.01(0.03) |

Age |

− 0.01 (0.02) |

0.01 (0.02) |

Volunteer activities |

0.03 (0.1)* |

0.01(0.01) |

Nonprofit organizations |

− 0.06 (0.03)* |

− 0.03(0.02) |

Trust in the neighborhood |

− 0.58 (0.41) |

− 0.21 (0.39) |

Income |

− 0.001 (0.001) |

0.01 (0.01) |

Education |

0.02 (0.10) |

− 0.26 (0.09)** |

First stage: participation |

||

Acknowledging the RSA purpose |

0.40 (0.05)** |

0.41 (0.06)** |

Intercept |

− 0.41 (0.32) |

− 0.57 (0.32) |

Rho |

− 0.79 |

− 0.66 |

Sigma |

0.65 |

0.61 |

Lamda |

− 0.52 |

− 0.40 |

LR test |

Chi2 = 17.30 (0.002) |

Chi2 = 3.14 (0.07) |

N (selected; nonselected) |

1,319 (1,156; 163) |

1,319 (1,156; 163) |

The survey targeted RSA participants rather than non-participants. To address potential selection bias, we applied the Heckman selection models, using a participation variable for selection. We operationalized participation as a binary variable: 0 for participants who responded with 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), or 3 (neither disagree nor agree) (163 cases), and 1 for those who responded with 4 (agree) or 5 (strongly agree) (1,156 cases) regarding voluntary participation. Considering the endogenous attributes of participation, the Heckman selection model results closely align with those of multilevel modeling, as demonstrated in the above table.