Introduction

The National Health Service (NHS) long term plan (NHS England, 2019) renewed the NHS’s commitment to improve specialist perinatal mental health services, to ensure support for all women who need it. This includes implementing Maternal Mental Health Services (MMHS) in every area of the country by 2023/24. MMHS provide maternity and psychological therapy for women experiencing moderate to severe, or complex mental health difficulties directly arising from, or related to, their maternity experience. This involves providing support for women who have had their babies removed at birth and are struggling with traumatic symptoms related to this. This paper endeavours to explore the needs of mothers when their babies are involuntarily removed and how MMHS can support them. In doing so, this paper will provide a background context on the reasons for infant removals and draw on existing literature to understand the specific needs of these women. Furthermore, due to a lack of comprehensive guidance, it will draw from literature for similar presentations, such as therapy recommendations for other perinatal losses, to propose therapeutic approaches that can be tailored to address these needs. Perinatal loss encompasses a range of experiences including miscarriage, stillbirth, neonatal death, termination for medical reasons and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (Sands, n.d.). Custody loss refers to a situation where a parent loses the legal right to care for their child, leading to the child being removed from their care, whether temporarily or permanently.

Background

Prevalence and context

Morriss and Broadhurst’s (Reference Morriss and Broadhurst2022) editorial outlines more than 13,000 women are involved in care proceedings every year in England and that many of these women will lose their children permanently from their care. Outlined in the Born into Care report, 173,002 children were involved in care proceedings between 2007/08 and 2016/17 in England, and 47,172 (27%) were infants (Broadhurst et al., Reference Broadhurst, Alrouh, Mason, Ward, Holmes, Ryan and Bowyer2018).

Newborn babies are removed at birth when the infant is identified as being at risk of suffering significant harm from one or both parents (Broadhurst et al., Reference Broadhurst, Alrouh, Mason, Ward, Holmes, Ryan and Bowyer2018). Harm is defined by the Children Act 1989 as the ill-treatment of a child or the impairment of their health or development. An application to the family court system can be triggered by neglect, physical, sexual and/or emotional abuse of a child. Additionally, issues for the parents such as domestic abuse, substance misuse, mental health difficulties, learning difficulties or contact with the criminal justice system are also considerations (Morriss, Reference Morriss2018). When there is reasonable cause to believe a child is, or is at risk of, suffering significant harm, care proceedings are initiated by the local authority under section 31 of the Children Act 1989 (Morriss, Reference Morriss2018).

Neuroscience and imaging research suggest babies and children who experience neglect and trauma have significant negative impacts on their brain development (Allen, Reference Allen2011). Growing up in an environment that is neglectful or abusive often results in a child who is unable to regulate their emotions, does not develop empathy and leads to increased risk of mental health problems, relationship difficulties, anti-social behaviour, and aggression (Allen, Reference Allen2011). Babies adopted within their first year, with the chance to form secure attachments, are more likely to fully recover compared with those adopted later in childhood (van den Dries et al., Reference van den Dries, Juffer, van Ijzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg2009). Later adoptees may continue to face attachment difficulties into adulthood (van den Dries et al., Reference van den Dries, Juffer, van Ijzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg2009: Raby and Dozier, Reference Raby and Dozier2019). This research has added to the evidence base that has contributed to an increase in court proceedings, particularly for children under one year old, thereby increasing the number of infant removals (Broadhurst et al., Reference Broadhurst, Alrouh, Yeend, Harwin, Shaw, Pilling, Mason and Kershaw2015). Furthermore, recent changes to the Children and Families Act 2014 in England and Wales introduced a 26-week maximum limit for case resolutions. This means parents have a restricted time frame to demonstrate required changes by the local authority, which could determine whether their children remain in care or are returned to them (Morriss, Reference Morriss2018).

Research by Marsh et al. (Reference Marsh, Robinson and Shawe2015) highlights the lack of societal acknowledgement of grief symptoms in mothers whose babies are removed at birth, hindering their recovery. This absence of support often leads to maladaptive coping behaviours like repeated pregnancies, perpetuating a cycle of trauma and removals (Marsh and Leamon, Reference Marsh and Leamon2019). Lacking sufficient support services, these women often find themselves repeatedly recounting their experiences to different professionals leading to recurring feelings of shame and embarrassment (Marsh and Leamon, Reference Marsh and Leamon2019). Addressing this issue requires broader societal recognition and tailored support structures. Efforts in research and advocacy are essential for improving the well-being of affected mothers and families.

Therapeutic needs of women who have experienced infant removal

The therapeutic requirements of women who have experienced involuntary infant removal can vary greatly and should be customised according to each woman’s personal history and present circumstances. This represents a crucial area where specialist MMHS can provide valuable assistance. The existing literature suggests several key therapeutic needs, three of which will be explored here: the impact on their identity, emotions of guilt and shame, and feelings of isolation.

Identity

The removal of an infant into care can deeply affect the birth mother’s sense of identity, both in her role as a mother and as an individual (Memarnia et al., Reference Memarnia, Nolte, Norris and Harborne2015). Women can struggle to navigate the dual process of holding onto and letting go of motherhood. This involves balancing detachment and maintaining hopes for a future relationship with their child (Siverns and Morgan, Reference Siverns and Morgan2021). Moreover, contending with the intricate emotions entailed in balancing societal expectations of motherhood with the reality faced by mothers of removed children can be challenging (Memarnia et al., Reference Memarnia, Nolte, Norris and Harborne2015). MMHS can assist mothers in coping with this identity struggle by leveraging insights from literature on other forms of loss and emphasising strategies for maintaining a relationship with the lost child (Scholtes and Browne, Reference Scholtes and Browne2015), thereby facilitating their ongoing identification as mothers. For instance, these connections may involve keeping mementos obtained during birth (such as hope boxes), commemorating birthdays and other significant occasions (through writing cards or letters, keeping them for future connection, or sending them if feasible). Bereaved families have employed diverse methods to sustain a bond with their lost babies, including creating memorial gardens, lighting candles, planting trees, and discussing the lost child with other family members or their other children (Rossen et al., Reference Rossen, Opie and O’Dea2023). These techniques can also serve as valuable means for preserving their identity as a mother and sustaining a connection with the baby who has been removed.

Guilt and shame

Mothers whose children are placed into care commonly harbour an intrinsic sense of maternal inadequacy, which inhibits their perceived entitlement to openly express grief. Consequently, they tend to suppress their emotions, choosing to bury their feelings instead (Siverns and Morgan, Reference Siverns and Morgan2021). Furthermore, there is a prevalent fear among these mothers that they will face negative judgement from both peers and professionals if they articulate the profound pain they experience because of the separation (Knight and Gitterman, Reference Knight and Gitterman2019). The overwhelming intensity of these emotions may drive women to resort to destructive coping mechanisms, such as alcohol consumption or self-harm, to numb the pain. Regrettably, these behaviours hinder the likelihood of seeking help (Memarnia et al., Reference Memarnia, Nolte, Norris and Harborne2015).

The stigma associated with having a child in care can complicate the grieving process (Memarnia et al., Reference Memarnia, Nolte, Norris and Harborne2015). Mothers often find themselves silenced by the fear of societal judgement, perceiving themselves as an inadequate parent, which adds to their apprehension about the potential removal of future children, thereby perpetuating the stigmatisation of their past experiences and compounding the challenges they face in subsequent motherhood (Morriss, Reference Morriss2018). Confronting and accepting their own role in the circumstances leading to their child’s removal can evoke profound emotional distress, prompting some mothers to adopt a defensive stance by attributing blame to professionals involved. This defensive narrative offers them a shield against an alternative perspective, one that challenges their sense of identity and self-worth (Memarnia et al., Reference Memarnia, Nolte, Norris and Harborne2015).

Isolation

Research indicates that women feel devalued as human beings, often perceiving a lack of recognition or validation for their experiences. Even when surrounded by others, they may still grapple with an overwhelming sense of isolation (Siverns and Morgan, Reference Siverns and Morgan2021). Due to feeling stigmatised, birth mothers often feel like outsiders in society (Scholfield et al., Reference Schofield, Moldestad, Höjer, Ward, Skilbred, Young and Havik2010). Public opinion often shifts blame to parents who have a child in care; society judges parents who appear to have failed at putting the needs of their children first (Schofield et al., Reference Schofield, Moldestad, Höjer, Ward, Skilbred, Young and Havik2010).

Understanding loss and grief

Comprehending the terms used around death of a loved one and their relevance to the experience of mothers who have had their babies removed at birth can aid MMHS in validating their experiences. Loss can be understood as an experience where returning to life as it once was feels impossible because of altered perception and circumstances (Harris, Reference Harris and Harris2020). Bereavement refers to the condition wherein individuals undergo the absence or loss of a person, relationship, object, or entity that holds subjective significance for them (Corr et al., Reference Corr, Corr and Doka2019). Bereavement is derived from the word bereft: deprived of, absent from, or torn away from (Black, Reference Black2020). Typically used to reference to the loss of a valued person, bereavement refers to a state of being in the aftermath of a significant loss (Black, Reference Black2020). According to the American Psychological Association (2018), grief is the anguish felt after a significant loss, usually the death of a loved one. It is not always synonymous with bereavement or mourning, as not all losses trigger intense grief. Grief often includes physical distress, separation anxiety, confusion, yearning, dwelling on the past, and fear of the future. Severe grief can endanger life by disrupting the immune system and leading to neglect or suicidal thoughts. It may also involve regret, remorse, or sorrow for personal misfortune.

Grief is a natural and integral component of the healing process following the death of a loved one. While normal grief can fluctuate it typically peaks immediately after the loss and gradually reduces over time (Bonanno, Reference Bonanno2004). Despite the intensity of emotional pain, individuals undergoing normal grief are generally able to accept the reality of the loss and reintegrate into daily life following the acute phase (Bonanno, Reference Bonanno2004). In 2022, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) was updated to include diagnostic criteria for prolonged grief disorder (PGD), also referred to in the literature as complicated grief (Eisma, Reference Eisma2023) in the DSM-5-TR (text revision of the DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). PGD is distinct from normal grief in that it is characterised by significant severity (marked distress and impairment in important life areas such as work, leisure and interpersonal relationships). Furthermore, PGD is differentiated from normal grief by its extended duration, with symptoms persisting for 12 months or longer (Eisma, Reference Eisma2023). Individuals with PGD often have trouble accepting the loss, as well as persistent yearning and/or preoccupation with the deceased, which significantly hinders their ability to move forward in life. Although the literature focuses on bereavement following death, there is a lack of empirical research describing the patterns of grief in mothers who have experienced custody loss. Despite this gap, existing knowledge can be applied to these mothers. Like bereaved individuals, these women may experience profound and prolonged grief, persistent preoccupation with the lost child, and difficulty reintegrating into daily life.

Ambiguous loss and disenfranchised grief

The theory of ambiguous loss can be useful to reflect on when thinking about the loss experienced after infant removal. Ambiguous loss is defined as ‘a situation of unclear loss that remains unverified and thus without resolution’ (Boss, Reference Boss2016; p. 270). Boss (Reference Boss2010) identified two types of ambiguous loss: physical absence with psychological presence, and physical presence with psychological absence. When considering ambiguous loss for women who have experienced infant removal, the most relevant type is physical absence with psychological presence. Even though the child is no longer physically present in the biological mother’s life, she still maintains thoughts and concerns regarding their present and future well-being (Knight and Gitterman, Reference Knight and Gitterman2019).

The model of disenfranchised grief is also useful to consider. Disenfranchised grief is defined as ‘the grief experienced by those who incur a loss that is not or cannot be, openly acknowledged, publicly mourned or socially supported’ (Doka, Reference Doka1989; p. 37). Doka (Reference Doka1989) highlights the isolating nature of this type of grief, noting that reactions are often complicated because individuals are unable to grieve in traditional ways as their losses are not recognised by society.

PTSD after loss

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is categorised into four symptom clusters in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013): re-experiencing, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, and hyperarousal. The DSM-5 also stipulates that these symptoms must be present for at least a month. The author reflects that this can result in mothers being referred into services just over a month after losing their babies, which could be too soon. Soloman and Rando (Reference Solomon and Rando2012) caution against trauma processing in the immediate aftermath of a loss, when numbness, denial, or dissociation may be present, as these are essential parts of the grieving process and should be respected rather than processed. However, it is equally important to recognise that research indicates failure to acknowledge or validate the grief these mothers experience can result in long-term psychological distress (Marsh and Leamon, Reference Marsh and Leamon2019). Moreover, when PTSD symptoms are evident, it is crucial to consider the potential negative impact of delaying treatment.

PTSD and PGD share similarities as both can arise following a traumatic event such as the removal of a baby. Both conditions can involve intrusive thoughts related to the loss, such as persistent memories or dreams. However, they differ significantly in their core symptoms and diagnostic criteria. PTSD is characterised by trauma-related symptoms including flashbacks, nightmares, and hyperarousal symptoms, including irritability and sleep disturbances (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In contrast, PGD is characterised by intense yearning for the deceased, with the individual unable to accept the death (American Psychiatric Association, 2022), or, in the case of these mothers, unable to accept the loss of their baby through removal. Moreover, PTSD includes avoidance of reminders of the trauma and heightened arousal (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), whereas PGD involves emotional numbness with difficulty adapting to life after the loss (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Both conditions involve distress and dysfunction following trauma; PTSD centres on trauma-related psychological and physical reactions, and PGD on the mourning process.

Current evidence base

There is a noticeable lack of empirical research investigating the experiences of mothers subjected to compulsory separation from their infants. At the time of writing, only two papers were found with a specific focus on the subjective experiences of these mothers, with only one of them focusing on a therapeutic intervention. The Memarnia et al. (Reference Memarnia, Nolte, Norris and Harborne2015) qualitative study included seven birth mothers who experienced the removal of their children into care. The study highlights the need for holistic, multi-disciplinary support for these mothers and emphasises the importance of early intervention to prevent crises and break inter-generational parenting cycles. It calls for therapeutic interventions to address their complex needs and help prevent repeated child removals. Additionally, the qualitative study of Morgan et al. (Reference Morgan, Nolte, Rishworth and Stevens2019) involved five mothers who experienced person-centred counselling following the compulsory removal of their children. The study identified that counselling is crucial in helping these mothers process their emotions and rebuild their identities, addressing the crisis in their sense of self. It also highlights the marginalisation they face within the adoption and foster care system, emphasising the need for more comprehensive and compassionate support to better meet their needs and enable them to reclaim their voices. With such a small amount of research in this area, our understanding of the emotional challenges faced by mothers in these situations and how to support them is limited. Additionally, there are no established clinical guidance for MMHS on how to effectively support these women. This paper addresses this significant professional issue for MMHS.

Marsh and Leamon (Reference Marsh and Leamon2019) examine both the similarities and differences in how mothers process grief following the death of a baby compared with those whose babies have been removed. Similarities between the two experiences include elevated levels of emotional distress and common grief responses, such as anger, guilt and depression. However, notable differences arise; mothers who have experienced infant removal often struggle with intense feelings of shame related to perceived maternal inadequacy (Marsh and Leamon, Reference Marsh and Leamon2019). Limited support and lack of mourning rituals can impede their grieving and lead to maladaptive coping mechanisms (Logan, Reference Logan1996). Additionally, these women frequently feel embarrassment and frustration from repeatedly recounting their experiences to professionals (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Robinson, Shawe and Leamon2020). Unlike mothers mourning the death of a baby, who typically experience some reduction in grief within 6 months, the grief of mothers whose babies have been removed tends to intensify over time (Marsh and Leamon, Reference Marsh and Leamon2019). Overall, these studies highlight the profound emotional impact of compulsory separation, yet the evidence base remains extremely limited.

Broadhurst and Mason’s (Reference Broadhurst and Mason2013) paper synthesizes existing knowledge to raise awareness of the issues of compulsory child removal. They advocated for preventative interventions and enhanced support services, including mental health and parenting support, and recommended integrating services, improving risk assessment, addressing root causes, and reforming policies to better prevent repeated child removals. Alongside the sparse evidence on custody loss itself, there is a small body of research and practice knowledge examining specific services and interventions for these mothers. The creation of hope/memory boxes is believed to offer immediate and long-term emotional support for experiences of loss (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Robinson, Shawe and Leamon2020). Hope (Hold on Pain Eases) boxes have been shown to help mothers feel connected to their babies as well as support the grieving process following permanent removal (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Ward and Broadhurst2023). Hope boxes are designed to capture the time spent between birth mother and baby before separation. Included in the Hope boxes are photos, footprints, cot cards, and matching toys and blankets. Two identical boxes are created, one for the birth mother and one for the baby (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Ward and Broadhurst2023). Additionally, Mason et al. (Reference Mason, Ward and Broadhurst2023) outline how in some areas of the country boxes include a poem or letter written by women from a lived experience group to help reduce the feelings of stigma and shame (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Ward and Broadhurst2023). The review of McGrath-Lone and Ott (Reference McGrath-Lone and Ott2022) found that women appreciated the chance to make mementos of their baby (foot and handprints, photos, locks of hair). These boxes or mementos can serve as valuable therapeutic tools that MMHS can integrate into clinical sessions, promoting an enduring sense of connection with the infant and encouraging a deeper engagement with the period spent with their child before separation.

In some areas of the country, specialist services exist to support mothers who have experienced infant removal to pause and reflect on their lives, helping them break the cycle of repeated removals. PAUSE initiates with a 16-week engagement phase, followed by the PAUSE program, during which women agree to postpone pregnancy for 18 months to focus on the program. The model is trauma-informed and prioritises the relationship between the women and her PAUSE practitioner. PAUSE offers practical support such as housing and benefits, assistance in accessing external therapeutic services (e.g. drug and alcohol counselling), support with physical health needs, and assistance in various life areas including exercise, education, relationships, and self-reflection. These interventions are tailored to the specific needs of each woman over the 18-month period (Pause, n.d.). Although PAUSE makes a significant contribution where it is available, it does not provide trauma-focused psychological therapy. In this context, MMHS can complement programmes such as PAUSE by delivering specialist trauma-focused interventions and developing collaborative pathways to address the complex needs of these mothers. It is essential that MMHS utilise the expertise of existing services in their area and collaborate to deliver support that is tailored to the specific circumstances of these mothers.

How can MMHS support women who have experienced infant removal?

A report published by the Maternal Mental Health Alliance (MMHA) in 2024 revealed that of the 41 identified MMHS operating nationwide, only 11 provided support for women who have experienced infant removal. Furthermore, the type of support offered varied significantly between services (Maternal Mental Health Alliance, 2024). This paper highlights the need for robust research to evaluate interventions for loss-related PTSD post-baby removal, given the absence of current guidelines for MMHS to provide this support.

Previous research (Marsh and Leamon, Reference Marsh and Leamon2019) indicates potential benefits from therapies used for stillbirth and pregnancy loss. Further to this, O’Connor et al. (Reference O’Connor, Lasgaard, Shevlin and Guldin2010) found overlapping dimensions of complicated grief and PTSD, particularly in shared experiences of intrusive symptoms. Consequently, trauma-focused treatments may be appropriate for addressing complicated grief such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), eye movement, desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) or narrative therapy. Therefore, MMHS might consider these therapies for working with mothers who have experienced infant removal. Importantly, research emphasises therapy is most effective when women feel they can trust therapists/professionals (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Cocks, Johnston and Stoker2017).

It is essential to recognise that MMHS are specifically designed to support women experiencing moderate to severe or complex mental health challenges directly associated with their maternity experience (NHS England, n.d.). Consequently, the primary role of MMHS is to address the immediate mental health needs arising from the trauma of infant removal after birth, rather than focusing on the long-term objectives of preventing future separation or custody losses. A comprehensive assessment is vital to determine if PTSD is present and to recognise the complex range of emotional and psychological responses these women exhibit. This complexity presents additional challenges for women, referrers, and services in determining the optimal starting point for interventions. While the criteria for accessing MMHS may vary nationally, it is imperative for these specialised services to establish a supportive and effective pathway for a demographic of women who may have previously encountered frustration or disappointment from past service encounters.

Additionally, MMHS are not typically designed to provide support specifically for grief, unless the individual is exhibiting PTSD-related symptoms. However, it can be beneficial to incorporate grief theories and models when working with these specific trauma presentations. In the absence of specific guidance on supporting these women, MMHS can draw on established theories and therapeutic models for loss and trauma to inform the assessment, formulation and treatment of their mental health needs.

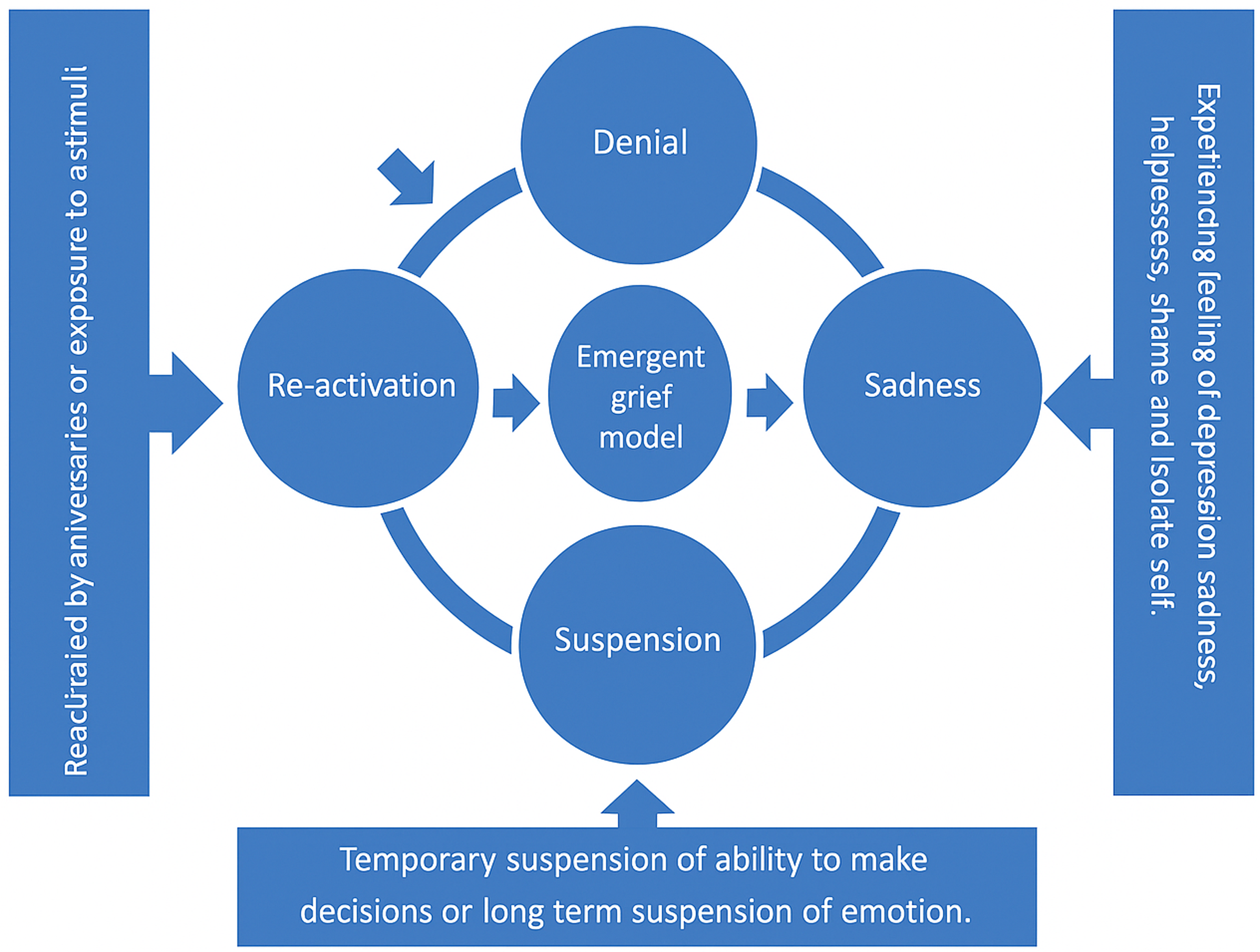

Models of loss

Kübler-Ross (Reference Kübler-Ross1969) outlines a five-stage non-linear theory of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. While this theory is useful, it should be used with caution. Marsh et al. (Reference Marsh, Robinson, Shawe and Leamon2020) conducted a qualitative study that found women whose babies were removed at birth experienced grief in a way that differed from the traditional stages. Initially, they felt disbelief or denial, bypassing anger and bargaining and proceeding directly to sadness resembling symptoms of depression. These women often felt suspended in time, sustaining the image of their baby as it was at the time of separation, and frequently pondering their baby’s well-being and whereabouts. These thoughts were regularly triggered by stimuli, significant events, and memories. This study emphasised the need for a better understanding of the grief process for these mothers. Although not validated, Marsh et al. (Reference Marsh, Robinson, Shawe and Leamon2020) proposed a model of the adaption and grief process experienced by mothers whose babies were removed at birth, based on the experiences of both mothers and those who cared for them (Fig. 1). This model can help women normalise and better understand their experiences after having their babies removed into care, especially when their emotions have been dismissed by others. Recognising these stages as part of the grieving process may also support early therapeutic work and strengthen the therapeutic relationship.

Figure 1. Adapted Model of Grief (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Robinson, Shawe and Leamon2020), a suggested model of the adaption and grief process experienced by mothers whose babies are removed at birth. Diagram published with permission from MIDIRS Digest.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

CBT is an ideal therapeutic approach for women who have experienced infant removals. In addition to the core techniques of CBT, the model underscores the critical role of the therapeutic relationship in facilitating change (Kazantzis and Dobson, Reference Kazantzis and Dobson2022). Central to this is the concept of collaborative empiricism, which fosters a partnership between the therapist and the client to identify and address unhelpful thoughts and behaviours and promotes a shared understanding and mutual respect (Kazantzis and Dobson, Reference Kazantzis and Dobson2022). Such a stance is particularly valuable when working with women who are understandably suspicious after repeated negative experiences of care and may enter therapy with caution and mistrust. Moreover, CBT’s emphasis on collaborative assessment and idiosyncratic conceptualisation of the presenting issues ensures that therapy is tailored to the individual’s needs, thereby fostering transparency and trust. The therapist’s commitment to engaging clients as active participants and maintaining a compassionate stance further supports the development of a positive therapeutic alliance.

McGrath-Lone and Ott’s (Reference McGrath-Lone and Ott2022) review found some evidence supporting the effectiveness of CBT for perinatal loss. Furthermore, Hassan and Homes (Reference Hassan and Holmes2023) contributed to the limited literature on pregnancy loss with a single case study, affirming the efficacy of CBT. Additionally, CBT has demonstrated effectiveness in addressing grief more broadly beyond the perinatal context (Boelen et al., Reference Boelen, de Keijser, van den Hout and van den Bout2007; Meysner et al., Reference Meysner, Cotter and Lee2016; Rosner et al., Reference Rosner, Pfoh and Kotoǔcová2011; Wild et al., Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlers2023). In terms of guidance for working with perinatal loss, Wenzel (Reference Wenzel2017) provides insights specifically for pregnancy loss. Kerr et al. (Reference Kerr, Warnock-Parkes, Murray, Wild, Grey, Green, Clark and Ehlers2023) offers a clinical considerations paper, serving as a valuable guide for addressing birth trauma and loss. Trauma-focused CBT (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for treating symptoms of PTSD (NICE, 2018). This paper advocate for trauma-focused CBT as an effective approach for mothers grappling with PTSD symptoms after the removal of their babies. It will now delve into specific adaptions, recommendations, and benefits of utilising CBT for this group of women. For more detailed and specific guidance and clinical implications for working with birth trauma and loss using CBT, refer to the key papers of Kerr et al. (Reference Kerr, Warnock-Parkes, Murray, Wild, Grey, Green, Clark and Ehlers2023) and Wenzel (Reference Wenzel2017).

CBT’s tailored approach to addressing cognitions, behaviours, emotions, and the therapeutic relationship makes it suitable for perinatal loss and PTSD (Wenzel, Reference Wenzel2017). In the early stages of therapy, it is essential to establish a safe and trusting therapeutic relationship, as many women seeking support after compulsory infant removal struggle to openly discuss grief due to societal stigma. Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlers2023) highlights how individuals experiencing traumatic bereavement may enter therapy feeling burdensome and pressured to progress more rapidly. This underscores the importance of normalising the range of emotions they may experience such as anger, grief, relief, or a combination of them all, and that experiencing these emotions is both ‘normal’ and acceptable. The assessment and formulation stage of CBT is an ideal opportunity to do this. Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlers2023) emphasises the importance of not rushing into restructuring the most distressing meaning but rather taking time to empathise and acknowledge the loss. While Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlers2023) focuses on responses to traumatic bereavement, the present paper identifies parallels in the experiences of women who have lost custody of their baby. It is therefore suggested that applying the recommendations from Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlers2023) may help women who have experienced custody loss to feel safe and supported in therapy, creating an environment in which they can begin to reconnect with their identities as mothers.

Kerr et al. (Reference Kerr, Warnock-Parkes, Murray, Wild, Grey, Green, Clark and Ehlers2023) emphasises the importance of early trigger discrimination in treatment. Given that many women have had challenging interactions with professionals in the past, it is crucial to be mindful of any potential impact on the therapeutic relationship. For instance, if the therapist exhibits characteristics that trigger trauma memories such as reminding the patient of a previous encounter with a dismissive midwife, this may hinder the development of a safe trusting therapeutic relationship. Trigger discrimination is particularly relevant for MMHS operating within maternity hospitals, where similar sounds and smells may evoke traumatic memories. Additionally, early attention on these triggers can help foster a therapeutic relationship that allows mothers to feel safe and supported to connect with issues around their identity, as well as process the painful and traumatic memories of their loss.

Addressing guilt and shame is a key focus as therapy progresses. Mothers often experience unhelpful thinking patterns, often focused on excessive guilt and feelings of failure towards their partners, family, and/or their baby (Wenzel, Reference Wenzel2017). Guilt and shame can be targeted by a range of CBT techniques particularly relevant for mothers who have had babies removed; techniques such as psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring to effectively identify and challenge unhelpful cognitions, visual aids such as pie charts, and utilising surveys for introspective assessment. Moreover, fostering compassionate imagery can help reduce feelings of guilt and shame, allowing mothers to adopt a less self-critical view of their loss. Wenzel (Reference Wenzel2017) underscores the importance of fostering acceptance to help women recognise that they can lead a meaningful life despite experiencing distressing thoughts and emotions. Furthermore, acceptance work serves as a viable alternative when cognitive restructuring is insufficient, enabling women to tolerate distress while staying aligned with their values.

When updating the trauma memory Kerr et al. (Reference Kerr, Warnock-Parkes, Murray, Wild, Grey, Green, Clark and Ehlers2023) discusses the advantages of helping the mother carry forward the meaning of the baby. They suggest that imagery can be a helpful tool in this process. Additionally, Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlers2023) emphasises the value of shifting focus from what has been lost to what remains. Supporting women in utilising imagery to carry their loved one forward in an abstract and meaningful manner, this facilitates a sense of continuity in the present, despite the loss experienced in the past.

Isolation is a prevalent issue for women who have had their babies removed, often driven by societal judgement or a desire to conceal the absence of their baby when they return from hospital, thus forgoing positive activities and social support. Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) underscore the significance of introducing reclaiming life activities early on in PTSD treatment. Wenzel (Reference Wenzel2017) accentuates the efficacy of behavioural activation in this regard. Connecting with family and friends and engaging in positive activities can help reduce isolation and restore a sense of connection. Additionally, Wenzel (Reference Wenzel2017) advocates for mindfulness techniques, facilitating a shift in focus from rumination on the past and future apprehensions to the present moment.

Reactions like anger, distress, and frustration are common and understandable emotions for women who have experienced infant removal. However, these emotional responses are often perceived negatively by professionals and the system (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Cocks, Johnston and Stoker2017). Women desire for their reactions to be seen as normal responses to a challenging situation (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Cocks, Johnston and Stoker2017). CBT techniques such as cost–benefit analysis of holding onto anger, writing no-send letters, and addressing blocking thoughts can help women manage and release their anger in a healthy and productive way.

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT)

CFT was developed as a therapeutic approach aimed at populations experiencing complex mental health difficulties characterised by self-criticism and high levels of shame (Au et al., Reference Au, Sauer-Zavala, King, Petrocchi, Barlow and Litz2017). It is rooted in evolutionary psychology, neuroscience and Buddhist philosophies (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009). In the context of baby loss and removals, women often present with high levels of guilt and shame. By cultivating self-compassion, CFT has the potential to address entrenched feelings of unworthiness and insufficiency while mitigating maladaptive tendencies such as social withdrawal and self-criticism (Au et al., Reference Au, Sauer-Zavala, King, Petrocchi, Barlow and Litz2017). While PTSD maintained by fear and perceived as an external threat is responsive to exposure therapy, PTSD driven by shame may be less responsive. Instead, it is better targeted by fostering self-compassion and addressing harsh self-criticism. CFT can help individuals develop a more compassionate and non-judgemental view of themselves, making it a better fit for shame-based trauma responses (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Scragg and Turner2001).

Dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT)

DBT was originally developed as a treatment for individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD). However, as it has evolved, its application has been extended to support any individual experiencing difficulties with emotional dysregulation and challenges in interpersonal relationships (Swales, Reference Swales2009). Core components of DBT, including mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotional regulation and interpersonal effectiveness, offer a structured and supportive approach for addressing the complex emotional and interpersonal difficulties often faced by these women, for example distress tolerance strategies provide practical tools to manage the acute emotional distress.

Narrative therapy

Narrative therapy, as recommended in studies by Memarnia et al. (Reference Memarnia, Nolte, Norris and Harborne2015) and Baxter et al. (Reference Baxter, Scharp, Asbur, Jannusch and Norwood2012), offers mothers an opportunity to construct meaning from their experiences and incorporate parts of their story that may have been dismissed or silenced by the courts. Through narrative approaches, mothers can rewrite their stories, potentially reducing feelings of shame and disenfranchised grief. This process allows them to include positive memories of their time with their baby before removal, express love for them, recount any parenting experiences (including moments during pregnancy), and recall positive memories despite challenges. Engaging in this work can also assist in addressing identity struggles post-removal (White, Reference White2007).

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR (Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2001) is an empirically supported and NICE recommended psychotherapeutic approach effective in treating trauma and other clinical issues, with efficacy in addressing grief (Solomon and Rando, Reference Solomon and Rando2012). Literature demonstrates EMDR as effective in working with complicated grief (Meysner et al., Reference Meysner, Cotter and Lee2016; Sprang, Reference Sprang2001; Ward, Reference Ward2021). Specific guidance for utilising EMDR for grief can be accessed through Luber’s (Reference Luber2012) Excessive Grief protocol and Solomon and Rando’s (Reference Solomon and Rando2012) clinical guidelines for working with grief and mourning. Although there is no specific guidance for using EMDR for perinatal loss, existing literature on grief can inform therapeutic work with women who have experienced infant removal.

Luber (Reference Luber2012) emphasises the importance of discussing early in therapy that EMDR recognises and does not attempt to eliminate healthy and appropriate emotions, such as sadness and grief. Instead, it helps individuals to mourn with a greater sense of inner peace, once the trauma blocking the grieving process has been addressed. Soloman and Rando (Reference Solomon and Rando2012) concur, stating a loss can be so distressing that it blocks access to memory networks containing positive memories of the loved one. By processing distressing memories, those networks can become accessible.

Luber (Reference Luber2012) and Soloman and Rando (Reference Solomon and Rando2012), consistent with the standard EMDR protocol, recommend focusing on past, present and future targets. In the case of baby removal, past targets may include intrusive memories or nightmares related to the loss of the baby, encompassing moments from the pregnancy, birth, the baby’s removal, or the revelation of the removal. Luber (Reference Luber2012) further discussed how these traumatic memories may obstruct access to the entirety of the relationship with the lost person, including positive experiences. For these mothers, such experiences may occur during pregnancy or in the moments immediately after birth before the baby’s removal. Additionally, other past targets may involve earlier unresolved losses and the woman’s thoughts about personal injury or mortality of other loved ones. Present triggers that activate grief are equally significant. For these women, issues of personal responsibility may surface as intense grief is processed, constituting an essential aspect of treating the concealed suffering (Luber, Reference Luber2012). Focusing on the future, a future template can be implemented, emphasising significant milestones like birthdays or Christmas, and reinforcing the belief that they can navigate life’s celebrations and challenges without their baby (Meysner et al., Reference Meysner, Cotter and Lee2016). Alternatively, during times when they may feel overwhelmed with emotions or struggles to cope in the future, compassionate imagery developed in the preparation sessions can be employed. This may involve imagining a resource team or compassionate other around them or engaging in grounding activities like imagining a calm place (Ward, Reference Ward2021). In some cases, women may not have the skills needed to cope in these future situations; in those cases Soloman and Rando (Reference Solomon and Rando2012) suggest learning these new skills either inside or outside of the therapy session to include in the future template. In addition, Ward (Reference Ward2021) conducted a case study focusing on the utilisation of compassion-focused techniques in EMDR memory reconsolidation for complicated grief. Ward (Reference Ward2021) found techniques aimed at facilitating experiential learning during memory reconsolidation, such as compassionate imagery, symbolic objects (e.g. breast milk jewellery, photographs, items from a memory box/hope box), and letter writing, to be beneficial. In the preparation sessions, emphasis was placed on establishing a sense of safety through practising grounding techniques, emotional regulation skills, and calm place imagery. Furthermore, techniques to support individuals with intense emotions (or those prone to dissociation) to remain within their window of tolerance, such as employing ‘the container’ technique, were deemed important. The ultimate goal of therapy is to support mothers in accessing the full range of feelings and experiences associated with their loss and move forward in their lives (Luber, Reference Luber2012).

Recommendations for services

As highlighted in this paper, women who have experienced infant removal frequently present with complex co-morbid conditions, some of which predate the custody loss and may require referral to specialist services. These may include substance misuse, experiences of domestic violence, and co-occurring mental health difficulties, factors that contribute to the removal itself and that precede the trauma associated with losing custody of their infant. It is imperative for MMHS to integrate an understanding of these factors into their assessments and work collaboratively with other services to recommend the most appropriate treatment or service, which may not always be trauma-focused therapy and may therefore fall outside the remit of MMHS. Unfortunately, the most suitable service to address the complex needs of these women are not always available. As a result, many fall through service gaps, perpetuating cycles of adversity, including the repeated removal of subsequent babies (Maternal Mental Health Alliance, 2024). Furthermore, it is important to recognise that some women may present as high risk and require a more comprehensive multi-disciplinary service, and these needs extend beyond the scope of MMHS.

For those taken on by MMHS, it is important to recognise the prevailing theme in the literature suggests that women often perceive professionals as not adequately listening to their perspectives. They frequently feel that the evidence presented in court misrepresent them as parents, reinforcing a sense of being misunderstood. Moreover, many women express that their feelings and emotions are often disregarded or considered unimportant in decision making processes (Memarnia et al., Reference Memarnia, Nolte, Norris and Harborne2015). By addressing barriers sensitively, therapists can create a supportive environment for healing. This stresses the importance of investing time in building a strong therapeutic relationship, considering potential emotional defences from past experiences and societal stigma. Drawing on theory and models of loss is invaluable in helping therapists validate women’s experiences. Building trust is a crucial foundation for effective therapy, as it affirms the women’s experience and provides validation and support in their journey to recovery. Siverns and Morgan (Reference Siverns and Morgan2021) discuss the importance of engaging mothers in a non-blaming conversation, to support them in telling and retelling their stories in ways that help them to re-evaluate their threat responses. Furthermore, normalising the distress mothers feel in relation to their loss (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Scharp, Asbur, Jannusch and Norwood2012) and recognising the importance of tailoring therapy to each individual, underscores the significance of an idiosyncratic approach. This approach allows therapists to consider the nuanced experiences and specific challenges of each person, thereby enhancing the effectiveness and relevance of therapeutic interventions. These decisions can be difficult for therapists to make, given the complexity these mothers present with. However, drawing on research related to complex presentations can provide valuable support in navigating these challenges. While therapeutic decisions may vary on a case-by-case basis, existing research can help therapists make evidence-based choices, even in the absence of specific guidance.

The Maternal Mental Health Alliance (2024) highlights the significant gap in the support MMHS can offer, given their current limited resources. It is essential to recognise the time needed to rebuild trust in professionals, build therapeutic relationships, and complete preparatory work, such as developing distress tolerance skills and addressing shame. Consequently, these women may require more sessions compared with those experiencing other types of perinatal loss. Evidence presented in this paper highlights the significance of these processes as pre-requisites for creating a sense of safety, enabling women to engage with and process distressing trauma memories effectively. To mitigate the risk of further extending waiting times, service delivery models face the challenging task of balancing the need for relationship-building with ensuring timely access to care, which makes it imperative that Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) consider allocating additional funding to support service expansion, ensuring that MMHS can meet the complex and diverse needs of this population without compromising service accessibility. With adequate funding, MMHS have the potential to break the cycle of intergenerational trauma and adversity, creating a new path that focuses on prioritising wellbeing (Maternal Mental Health Alliance, 2024).

Further research is necessary to explore the subjective experiences of these mothers, which will deepen our understanding of their unique challenges. Additionally, research is needed to assess therapeutic approaches to work with the complex needs of these women, such as trauma-focused CBT and EMDR. Evidence-based guidance is crucial to inform MMHS on how to implement the most effective strategies for addressing the trauma experienced by these women. Such research would provide valuable insights into adapting interventions to better meet their specific needs and improve longer term outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper highlights the professional challenge posed by the lack of specific therapy guidelines for addressing the complex grief and PTSD experienced by mothers affected by infant removal. As such, it advocates for the development of guidance in this domain and underscores the necessity for further research. MMHS encounter the dual challenge of managing the intricate presentation of these women and determining the optimal timing for intervention. Distinguishing between symptoms inherent to the grieving process, vital for healing, and those indicative of trauma necessitating intervention, presents a nuanced dilemma. The author anticipates that this paper will stimulate thought-provoking discussions within MMHS nationwide and contribute to the development of effective pathways tailored to meeting the needs of these mothers, in line with the NHS long-term plan (2019) to ensure support for all women who need it.

Key practice points

-

(1) Although there are no current guidelines on working with trauma related to infant removal, therapists can draw on other trauma after loss models, such as trauma-focused CBT, EMDR or narrative therapy.

-

(2) In addition to appropriate therapeutic adaptions to current models of therapy, MMHS also need to juggle appropriate timing of interventions and multi-disciplinary work to assess the most suitable service.

-

(3) Further research and evaluation of these treatments as part of service provision is required to understand the effectiveness for this patient group.

Data availability statement

Not applicable for this article.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contribution

Tara Buckler: Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (lead).

Financial support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Ethical standards

This work adheres to the ethical principle and code of conduct set out by the BABCP. Ethical approval was not required given this paper draws on existing literature and did not involve recruitment of participants.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.