Introduction

Family is important in shaping the political thought of citizens, as the field of political socialization has demonstrated considerable overlap in parental and children's political orientations (Beck & Jennings, Reference Beck and Jennings1991; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968; Ventura, Reference Ventura2001; Westholm & Niemi, Reference Westholm and Niemi1992). Parents are therefore considered important socializing agents for the development of adolescents’ political preferences and behaviour (Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1974; Percheron & Jennings, Reference Percheron and Jennings1981); and remain of enduring influence until later in life (Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009). However, the lion's share of family political socialization research has been performed decades ago. The question arises to what extent the classic socialization model, providing a stable base for the initial formation of voters’ political preferences, is still valid nowadays in light of increased volatility and the decrease in partisanship (Chiaramonte & Emanuele, Reference Chiaramonte and Emanuele2017; Dalton, Reference Dalton2002). While the left-right distinction forms the main summarizing concept of political ideology in Western Europe, only few studies have recently analyzed the transmission of left-right identification, in two specific regions (Corbetta et al., Reference Corbetta, Tuorto, Cavazza and Abendschön2013; Rico & Jennings, Reference Rico and Jennings2016). Other recent research in political socialization in Europe (Avdeenko & Siedler, Reference Avdeenko and Siedler2017; Coffé & Voorpostel, Reference Coffé and Voorpostel2010; Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2011; Hooghe & Boonen, Reference Hooghe and Boonen2015; Kroh & Selb, Reference Kroh and Selb2009; Zuckerman et al., Reference Zuckerman, Dasovic and Fitzgerald2007) takes a relatively similar approach as the seminal studies. This study, on the other hand, focuses on the transmission of left-right ideological positions in European multiparty systems.

Furthermore, this study considers the implications of the political gender gap for the intergenerational transmission of political ideology. The process of gender realignment – observed by the 1990s in most Western countries – reversed the gender gap in political preferences and ideology (Inglehart & Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2000), but this has been overlooked by existing studies in political socialization. The fact that gender differences are increasing in younger generations (gender-generation gap) is expected to impact patterns of intergenerational political similarity, but these could remain unobserved when considering ideology transmission as a linear process. Moreover, studies in political socialization have reached inconsistent conclusions regarding the larger impact of one parent relative to the other (Acock & Bengtson, Reference Acock and Bengtson1978; Gniewosz et al., Reference Gniewosz, Noack and Buhl2009; Ventura, Reference Ventura2001; Zuckerman et al., Reference Zuckerman, Dasovic and Fitzgerald2007) and same-sex dynamics in intergenerational transmission (Avdeenko & Siedler, Reference Avdeenko and Siedler2017; Filler & Jennings, Reference Filler and Jennings2015; Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Wass and Valaste2016; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968). This study connects these two strands of literature and tests different hypotheses about gendered patterns in parent–offspring concordance. To adequately study these dynamics, the analysis differentiates between the transmission of left- and right-wing positions by mothers and fathers, towards their daughters and sons.

In doing so, this study complements previous work in political socialization by providing a comparative account of the transmission of left-right positions in two European multiparty systems. Valuable intergenerational data providing direct accounts of the political ideology of respondents and their mothers and fathers are employed from German and Swiss household surveys. The analyses show generally a large overlap in parent–offspring ideology, which is increased by parental similarity in ideology. While no evidence is found for same-sex patterns in political socialization, other gendered patterns are demonstrated: the gender-generation gap is consequential for intergenerational similarity in political ideology as sons and daughters systematically differ in their probability to take over parental left- and right-wing positions. While parent–son transmission is equal across the ideological leanings of parents, this is not the case for parent–daughter transmission, as young women consistently lean more strongly than do their parents. The patterns induced by the gender-generation gap point at a more active role of especially female offspring in political socialization processes, and imply a general advantage of left-leaning over right-leaning parents in having their political orientations emulated in the next generation. The concluding section discusses these findings in relation to previous work in the field, underlining the applicability of the family socialization model to the intergenerational transmission of left-right positions. Moreover, it stresses the importance of distinguishing by ideological leaning and by offspring gender when studying the transmission of political traits that demonstrate gender differences within and between parental and offspring generations.

The intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology

The intergenerational transmission of political preferences and ideology is considered an important part of family political socialization. Social learning theory provides the first explanation for this process, positing that children take over attitudes and values from their parents through observation and imitation, as parents play a key role in children's lives (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1974; Percheron & Jennings, Reference Percheron and Jennings1981). The socialization process can be intentional or unintentional, with parents engaging in overt transmission, or rather serving as role models (Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968). The second main explanation for parent–child political similarity is the inheritance of structural factors such as socioeconomic position and religion, that results in similar preferences that are connected to certain political predispositions (Beck & Jennings, Reference Beck and Jennings1982; Glass et al., Reference Glass, Bengtson and Dunham1986). More recent work suggests a more active rather than passive role for children in political socialization processes, rooted in family political communication (McDevitt & Chaffee, Reference McDevitt and Chaffee2002). Empirical studies demonstrate the two-directionality of these family influences (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2011; Zuckerman et al., Reference Zuckerman, Dasovic and Fitzgerald2007).

The present study applies the family political socialization model to the transmission of political ideology from parents to children, as measured by identification with a position on the left-right scale. Most of the seminal studies in political socialization stem from the United States, and have focused on the transmission of partisanship (Beck & Jennings, Reference Beck and Jennings1991; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968). Due to various problems with the applicability of this concept in Europe, Percheron and Jennings (Reference Percheron and Jennings1981) conclude that it is country-specific whether partisanship or left–right ideology (or another relevant dimension) is passed on from parents to children. In stable multiparty systems, it is more likely that left–right ideology is transmitted. As a higher number of parties hinders the transmission of an attachment to one specific party, ideology is the cue with the largest heuristic advantage (Ventura, Reference Ventura2001; Westholm & Niemi, Reference Westholm and Niemi1992).

Despite these findings, most European work on intergenerational political transmission relies on party identification or party preferences (Boonen, Reference Boonen2017; Kroh & Selb, Reference Kroh and Selb2009; Zuckerman et al., Reference Zuckerman, Dasovic and Fitzgerald2007). The salience of the left-right distinction in West European politics, the increased volatility and the decline in partisanship (Chiaramonte & Emanuele, Reference Chiaramonte and Emanuele2017), and voters’ within-block vote volatility (Van der Meer et al., Reference Van der Meer, Van Elsas, Lubbe and Van der Brug2015) are additional reasons why political socialization processes in Western Europe can be understood in terms of political ideology transmission. However, only few studies have recently investigated the transmission of left-right ideology, using data from Italy and Catalonia (Corbetta et al., Reference Corbetta, Tuorto, Cavazza and Abendschön2013; Rico & Jennings, Reference Rico and Jennings2016). Therefore, this research complements the current state of the field by investigating the intergenerational transmission of left-right positions in two other multiparty contexts, Germany and Switzerland. It provides a comparative overview of the level of transmission and the factors that impact this process, with a specific focus on gender differences.

Left-right identification is one part of individuals’ political identity. Therefore, focusing on the transmission thereof inevitably implies that other relevant aspects such as political interest, processes of civic learning and instillment of civic duty, fall outside the scope of this study. However, this summary measure of political ideology is one of the main ways to describe individuals politically in Western Europe. Left and right are the most used terms to distinguish political ideologies, for political parties and citizens. Left-right self-placement is widely used as a summarizing concept of individuals’ political ideology, and a large majority of the electorate has been able to place themselves on the left-right scale since decades (Inglehart & Klingemann, Reference Inglehart, Klingemann, Budge, Crewe and Farlie1976; Mair, Reference Mair, Dalton and Klingemann2007). The measure has also been criticized for being an “empty vessel” and not adequately capturing the multidimensionality of the political space (Huber & Inglehart, Reference Huber and Inglehart1995). The meaning of left and right indeed varies across time and space (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Barberá, Ackermann and Venetz2017; De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hakhverdian and Lancee2013). However, when studying intergenerational political socialization processes, I argue that this flexibility is rather an advantage. Using the left-right scale as a shortcut for ideology that adapts its meaning to salient political issues and dimensions at a given time, implies that it is a durable cue for intergenerational transmission that is not limited to a specific political context at a given time. By focusing on left- and right-wing identification, this study provides new insights regarding the intergenerational transmission of political ideology, while at the same time remaining close to the tradition of the political socialization field.

Parent–child political socialization: Mothers, fathers and the political gender gap

The question which of both parents is more influential in the political socialization process has been asked repeatedly. In reality, parental couples are often similar in many respects: a phenomenon attributed to ‘assortative mating’, which also extends to political traits (Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1971; Zuckerman et al., Reference Zuckerman, Dasovic and Fitzgerald2007). Social learning theory states that when parents have similar political preferences, they are better able to transmit those to the child, because it receives uniform cues and no cross-pressures (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977). Recent studies confirm that this classic explanation for heightened parent–child concordance is still valid in recent American and Catalonian contexts (Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009; Rico & Jennings, Reference Rico and Jennings2016). Therefore, I also expect heightened parent–offspring similarity in political ideology when both parents identify with the same ideological block (H1) that is, when both parents identify themselves as on the left, in the centre, or on the right.

However, when parents differ in their ideological leaning, how does that affect political transmission in families? While initial work considered the father the most important socializing agent in the household (Lazarsfeld et al., Reference Lazarsfeld, Berelson and Gaudet1968 [1944]), this is rejected by most empirical research that finds rather equal socializing roles of mothers and fathers (Boonen, Reference Boonen2017; Gniewosz et al., Reference Gniewosz, Noack and Buhl2009; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968, Reference Jennings and Niemi1971; Ventura, Reference Ventura2001). Some studies conclude, to the contrary, that the mother is the most important socializing agent (Acock & Bengtson, Reference Acock and Bengtson1978; Zuckerman et al., Reference Zuckerman, Dasovic and Fitzgerald2007), explained by the fact that she usually spends more time with the children relative to the father, which enhances social and political learning (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Wass and Valaste2016). Another explanation is the mother's different communication style with greater emphasis on conversation, which could foster mother–child political similarity (Shulman & DeAndrea, Reference Shulman and DeAndrea2014).

An additional factor to consider is the combination of parent and child sex. Gendered parenting practices and bidirectional patterns of same-sex identification (Conley, Reference Conley2004; Lynn, Reference Lynn1966; McHale et al., Reference McHale, Crouter and Tucker1999) can result through social learning and role modelling in stronger socializing influences between parent and offspring from the same sex (Bussey & Bandura, Reference Bussey and Bandura1999). At the same time, the empirical evidence for such patterns in political preference transmission is mixed.Footnote 1 Earlier US studies on party identification transmission either found modest same-sex patterns, with particularly stronger ties between mothers and daughters (Jennings & Langton, Reference Jennings and Langton1969; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1974, p. 169), or no evidence thereof (Acock & Bengtson, Reference Acock and Bengtson1978; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968). By contrast, positions on gender and politics issues do show stronger same-sex intergenerational concordance, especially between mothers and daughters (Filler & Jennings, Reference Filler and Jennings2015). In Europe, results are not consistent either. In the Netherlands and Germany, studies find a heightened same-sex transmission of party preferences and right-wing extremist attitudes (Avdeenko & Siedler, Reference Avdeenko and Siedler2017; Nieuwbeerta & Wittebrood, Reference Nieuwbeerta and Wittebrood1995). However, other work on the intergenerational impact of political discussion with parents (Belgium) and of parental turnout (Finland) finds no evidence for same-sex patterns, but distinct generalized influences of mothers and fathers (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Wass and Valaste2016; Hooghe & Boonen, Reference Hooghe and Boonen2015).

These previous studies hypothesized heightened political similarity between parents and offspring of the same sex, based on mechanisms of same-sex identification and role modelling. According to this reasoning, gender here is the main distinguishing factor of influence in intergenerational political transmission, and concretely implies two types of gender differences: by gender of offspring, and by gender of parents. First, it considers differences in parent-offspring similarity between daughters and sons, a comparison between offspring by gender in parent-offspring concordance. This suggests greater ideological similarity of mothers and daughters, compared to sons (H2a); and of fathers and sons, compared to daughters (H2b). Second, this expectation suggests a distinct impact of the mother relative to the father on their offspring's political positioning, a comparison of the respective impact of the two parents in mother–father–offspring combinations. It leads to the hypothesis that among parental couples of dissimilar ideological leaning, mothers more strongly affect their daughters’ political ideology than fathers (H3a); and fathers more strongly affect their sons’ political ideology than mothers (H3b).

However, due to the mixed evidence on other political traits, it is an empirical question whether same-sex dynamics are observed in the transmission of political ideology. Therefore, next to testing these hypotheses, this study adds an important factor overlooked by previous work in political socialization: the political gender gap. While women used to hold on average more conservative political views than men, gender realignment during the 1980s and 1990s has resulted in women moving to the left of men in Western post-industrial societies (Inglehart & Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2000). The contemporary gender gap in political ideology implies women being more left-wing than men, which is explained by women's decreased religiosity and more egalitarian attitudes (Kittilson, Reference Kittilson2016). In younger generations, women are increasingly more leftist than men, a phenomenon referred to as the gender-generation gap (Shorrocks, Reference Shorrocks2018).

I argue that the political gender gap cannot be overlooked when studying parent-offspring political transmission. In the absence of same-sex dynamics, the gender-generation gap alone can be expected to result in relevant differences between daughters and sons in parent-offspring political transmission. Recent studies show that women of younger generations are moving increasingly to the left of their male peers, while their parents’ generations do not show such similar change. Consequently, we can expect asymmetries in parent–offspring concordance of left-leaning versus right-leaning ideologies by offspring gender, as the probability to take leftist positions is higher for women in younger generations. In line with recent work in political socialization discussed earlier, these expectations imply a more active role of offspring in the political socialization process, and do not consider parents as the sole socializing influence that their offspring is exposed to. Generational differences and political dynamics lead women in younger generations to move increasingly towards the left of men (period forces) and result in young men taking on average more often right-wing positions than women. Therefore, we can expect greater ideological similarity of left-wing parents and their daughters, compared to their sons (H4a), and of right-wing parents and their sons, compared to their daughters (H4b). Contrary to the expectations based on same-sex dynamics, these considerations imply general differences between left-leaning and right-leaning parents rather than regarding the relative role of both parents among dissimilar ideological parental couples. Because of the previously described period forces we can expect that left-leaning parents are more successful than right-leaning parents in having a daughter of similar ideological leaning (H5a); while right-leaning parents are more successful than left-leaning parents in having a son of similar ideological leaning (H5b).

Country differences

The countries included in this study are Germany and Switzerland, two West European multiparty systems that differ in a few important respects. First, as Switzerland has a fully proportional system with a high degree of federalism (Kriesi & Trechsel, Reference Kriesi and Trechsel2008), this leads to a more fragmented party system with a higher absolute and effective number of political parties than Germany that has a 5 per cent election threshold (Laakso & Taagepera, Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979). A higher number of parties hinders the transmission of an attachment to one specific party from parents to children (Ventura, Reference Ventura2001), which makes it generally more likely that left–right ideology is transmitted in stable multiparty systems (Westholm & Niemi, Reference Westholm and Niemi1992). Therefore, the transmission of left–right ideology is expected to be higher in Switzerland than in Germany. In both countries, the left-right scale structures the political space. While the left-right scale was embedded somewhat later in the Swiss electorate's political thinking compared to Germany (Inglehart & Sidjanski, Reference Inglehart, Sidjanski, Budge, Crewe and Farlie1976), the left-right scale in Switzerland became one of the strongest ones in Europe in terms of ideological meaning (Medina, Reference Medina2015). In Germany, the concept of left-right identification has leverage in former East and West Germany, before and after reunification (Inglehart & Klingemann, Reference Inglehart, Klingemann, Budge, Crewe and Farlie1976; Neundorf, Reference Neundorf2009). While former East and West Germans have been politically socialized under sharply different regimes of which consequences are still visible 30 years after reunification, this is not reflected in their subsequent familiarity with the terms ‘left’ and ‘right,’ nor in differential usage of the left-right scale (Neundorf, Reference Neundorf2009).

Other pertinent differences between the two countries consist of the direct democratic system and the relatively late introduction of women's suffrage in Switzerland (Kriesi & Trechsel, Reference Kriesi and Trechsel2008). The former would suggest that politics is more often an object of discussion, which may enhance political socialization processes. On the other hand, the late universal suffrage could reduce the role of mothers in these processes, as women might be less perceived as political role models. Moreover, as the expectations in this study are conditional on the political gender gap, findings can be expected to differ depending on the size thereof. While during the 1990s the gender gap was somewhat larger in Germany than in Switzerland (Inglehart & Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2000), more recently the reverse was found, with the Swiss political gender gap being the second-largest in Europe (Abendschön & Steinmetz, Reference Abendschön and Steinmetz2014).

Research design

Data

The data demand for this study are high, as it requires direct accounts of the political ideology of mothers, fathers and their offspring. Therefore, household data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (G-SOEP) and the Swiss Household Panel (SHP) are used (Goebel et al., Reference Goebel, Grabka, Liebig, Kroh, Richter, Schröder and Schupp2019; SHP Group, 2019). Waves are analyzed in which the left-right self-placement variable is available (G-SOEP: 2005 and 2009; SHP: all waves 1999–2017). The waves are pooled without overlap, by using for each respondent the observations from the most recent year (wave) in which their and their parents left-right self-placement was reported. Observations of parents and offspring are taken from the same year. In the SHP, 1-year lags for the parental ideology are used if no self-placement by parents was reported in the same year.Footnote 2

Respondents are observed from age 16 (SHP) and age 17 years (G-SOEP) onwards. All analyses are restricted to respondents of whom their own and their parents' ideology are directly observed, whether they live in the same household or not. Although the datasets provide representative samples of the German and Swiss populations, respectively, the analytic samples applied here are biased towards respondents whose parents are included in the household study, and their own and their parents’ political ideology is reported. Therefore, the analytic samples in this study are younger (mean age respectively 23 (SHP) and 29 (G-SOEP)) than the full samples of the datasets (mean age 50 in both datasets). The analyses are demanding as they require the joint observation of the ideology of the mother, father and offspring from the same family, and control variables, which decreases the number of observations. All analyses are performed on this analytic sample. To ensure comparability and exclude potential outlier influence of older respondents, both samples are restricted to respondents under age 36 years, as 97 per cent of the analytic SHP sample falls in that age group.Footnote 3 Consequently, the outcomes of the study are limited to adolescents and young adults.

Variables

The dependent variable is left–right self-placement (scale 0–10), recoded into left-wing (0–4), centre (5) and right-wing (6–10) blocks for the first set of descriptive analyses. Subsequent dyadic multivariate analyses use the similarity in ideological blocks between offspring and parent's left-right positions as dependent variable (0 = different block; 1 = same block). Finally, additional triadic multivariate analyses that predict offspring's ideology across combinations of both parents’ ideology, use respondents’ position on the left-right scale (0–10) as the dependent variable.

The following independent variables are included. Mothers’ and fathers’ left-right positions are also measured using the left-right self-placement variable, recoded into left, centre and right. A dummy variable for parental similarity in ideology indicates whether both parents adhere to the same ideological block (0 = different block; 1 = same block). Treiman's social prestige score (Treiman, Reference Treiman1977) serves as a proxy for socioeconomic status (SES) of origin, recoded into low, medium and high social prestige (30th percentile; 31st–69th percentile; 70th–100th percentile). Respondents’ level of education is measured in the year of their left-right placement, recoded into lower (inadequately and general elementary), medium (middle vocational and vocational, in G-SOEP also Abitur) and higher education (higher vocational and higher education), and the category ‘still in (compulsory) school’. Finally, in the G-SOEP, most respondents were born before German reunification in 1989. Therefore, region of residence in 1989 is included (former East Germany, West Germany, or abroad), to control for the different political regimes. For respondents born after reunification (17 per cent of the sample), the region of residence in the year of the left–right self-placement is used.

Analytic strategy

Unlike most previous studies, this research does not model the transmission of political ideology as a linear process, but differentiates between the transmission of left and right ideologies, and explicitly models the (dis)similarity of parental political leanings. As such, this is the first study investigating the distinct transmission of left- and right-wing ideologies between mothers, fathers, daughters and sons. The analytic strategy entails descriptive analysis and two types of multivariate analysis explained in detail below.

First, descriptive analyses show ideological similarity in parent–child dyads and among parental couples, and the political gender gap in the two generations. Then, a set of dyadic multivariate regression analysis investigates parent–offspring ideological similarity separately for mothers and fathers, estimating the probability of the child's adherence to the same ideological block. Parent–offspring similarity (1 = yes, 0 = no) is regressed on parental ideological similarity to test H1, and on parental ideology (left, centre, right). To test differences between parent–daughter and parent–son dyads (H2 and H4) in the transmission of left- and right-leaning positions (H5), parental ideology is interacted with offspring gender to calculate the average probability to adhere to the same ideological block. Linear probability models (LPM) are used instead of non-linear models because of the possibility to compare coefficients across models, and the easier interpretation (Angrist & Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2008). Moreover, the out-of-range predictions comprise less than 1 per cent and the main results of interest are the average predicted values, for which the application of a LPM rather than a logit model is deemed appropriate (Mood, Reference Mood2010).

Finally, to directly compare the relative impact of both parents (H3), their ideologies are jointly included in multivariate ordinary least squares (OLS) analyses using triads (mother–father–offspring). This configuration implies a more rigorous test of H5, as the dyadic analysis does not consider the joint impact of both parental ideologies. The dependent variable differs from the foregoing analysis, as no single value for parent-offspring similarity can be produced when working with triads. The mother's and the father's left-leaning and right-leaning positions are interacted with each otherFootnote 4 and with offspring gender in predicting offspring's left-right ideology. This three-way interaction allows to predict offspring's ideological positioning across different combinations of parental ideology and by offspring gender (H5), and to test whether the relative impact of the mother's and father's ideologies significantly differ (H3). This analysis can also be regarded as a replication of the foregoing analysis in testing the other hypotheses. As multiple children from the same family are often present in the sample, robust standard errors are clustered at the family level in all multivariate analyses.

Results

Descriptive analyses: Similarity in left–right ideology in families

First, I discuss results of descriptive analyses regarding dyadic parent–offspring similarity in ideology. A majority of parent–offspring dyads take similar left–right positions, with a larger overlap in mother–offspring dyads (differences statistically significant at p < 0.01 in G-SOEP and SHP). In Germany, 64 per cent of mother–child and 60 per cent of father–child dyads have a distance of 0 or 1 on the left-right scale. In Switzerland, respectively 54 per cent of mother–child dyads and 51 per cent of father–child dyads take such close positions. These findings are similar to earlier studies on left–right ideology transmission in Catalonia (Spain) and Italy (Corbetta et al., Reference Corbetta, Tuorto, Cavazza and Abendschön2013; Rico & Jennings, Reference Rico and Jennings2016). Correlations (Pearson's R) between parent and offspring left-right positions in Germany and Switzerland are respectively 0.30 and 0.42 (mother–offspring); and 0.26 and 0.40 (father–offspring). This may indicate that left–right transmission in Germany is now higher than before, as a correlation of 0.20 in West Germany was reported using 1970s data (Westholm & Niemi, Reference Westholm and Niemi1992). In short, parents and children take very close left–right positions, in both Germany and Switzerland, and in line with expectations, transmission rates seem to be somewhat higher in Switzerland than in Germany.Footnote 5

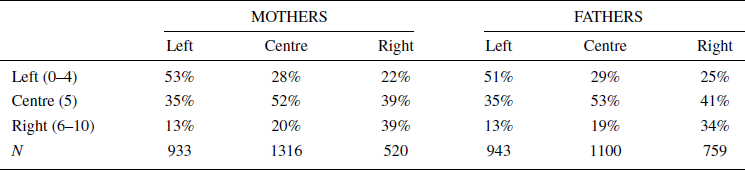

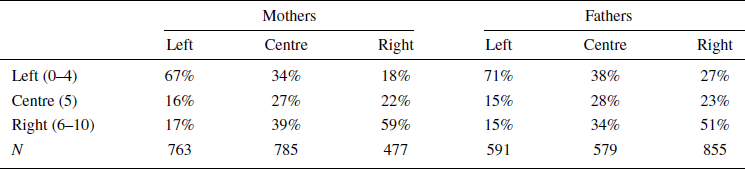

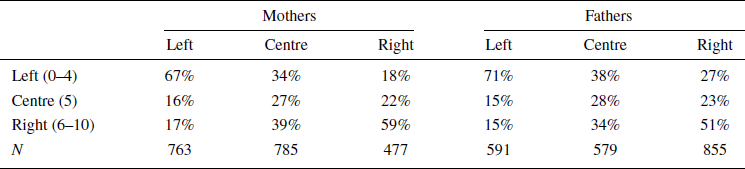

Subsequent analyses present the overlap in ideological blocks. Table 1 and Table 2 display the overlap in left (0–4), centre (5) and right (6–10) positions for parent–offspring dyads. Highlighted cells on the diagonals indicate adherence to the same ideological block, whereas off-diagonal cells indicate offsprings identifying with a different ideological block than the parents. The results show relevant similarities across both countries. First, a left-wing ideology is most often transmitted, with the overlap ranging between 51–53 per cent (Germany) and 67–71 per cent (Switzerland). Second, in these dyadic analyses, that do not include the other parent's ideology and do not distinguish by offspring gender, the overlap by ideological block does not seem to systematically differ between fathers and mothers.

Table 1. Germany: Overlap in ideological blocks between parents and offspring, column percentages

Source: Author's calculations using G-SOEP 2005 and 2009 (N = 2802).

Table 2. Switzerland: Overlap in ideological blocks between parents and offspring, column percentages

Source: Author's calculations using SHP 1999–2017 (N = 2025).

The main differences between the two countries regard the transmission of centre and right-wing positions.Footnote 6 In Germany, left and centre positions are more often transmitted (51–53 per cent) than right-wing positions (34 and 39 per cent). A surprising finding is that children of right-wing fathers more often take a centre (41 per cent) than a right-wing position (34 per cent), pointing at the offspring generation's more progressive political positioning. In Switzerland, the centre position is not as much transmitted (27 and 28 per cent) as in Germany, and left- and right-wing positions are more equally transmitted (percentages ranging between 51 and 71 per cent). However, while a majority of Swiss fathers take rightist positions, left-wing fathers are more successful in transmitting their ideology than right-wing fathers, again indicating the younger generation taking on average more progressive/leftist positions than their parents.

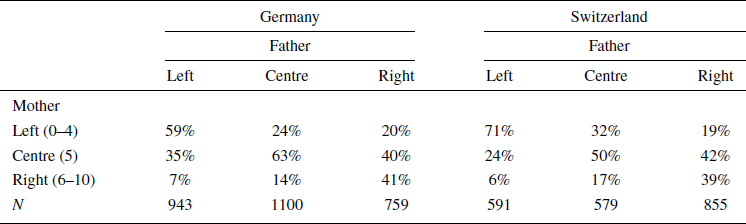

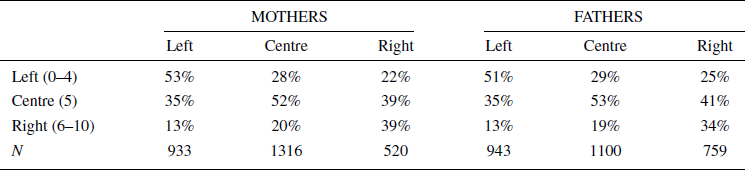

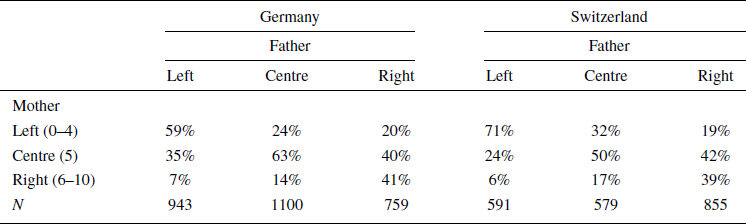

In line with literature on assortative mating and political homogamy, a majority of parental couples identify with the same ideological block (55 per cent in Germany, 51 per cent in Switzerland). Table 3 displays different combinations of the couples’ ideology, where highlighted diagonal cells indicate ideological similarity. The results show that when parents differ in their ideology, the most common combination is one parent identifying with the left or the right block and the partner taking a centre position. In both countries, the political gender gap in the parental generation is apparent: among left-wing fathers, 59 and 71 per cent have a partner adhering to the same block, while among right-wing fathers, this is 41 and 39 per cent.

Table 3. Overlap in ideological blocks between mothers and fathers, column percentages

Source: Author's calculations using G-SOEP 2005 and 2009 (N = 2802) and SHP 1999–2017 (N = 2025).

The gender gap in ideology is a precondition of the analyses performed in this study. Comparing average ideological positions by gender is a common measurement of the political gender gap. T-tests (p < 0.01) confirm that women take ideological positions on the left of men in the data applied here. In the German sample, the gender gap in ideology is 0.5 among offspring (sons M = 4.9; daughters M = 4.4), and 0.2 among parents (fathers M = 4.8, mothers M = 4.6). In the Swiss sample, the gender gap is 0.8 in the offspring generation (sons M = 5.2; daughters M = 4.4), and 0.6 among parents (fathers M = 5.3; mothers M = 4.7). The data thus show the gender-generation gap as identified by previous studies (Shorrocks, Reference Shorrocks2018), that is, larger gender differences in political ideology in the younger generation. This is the result of women in the offspring generation taking more leftist positions compared to women in the parental generation, whereas there are little to no differences in men's positioning across generations. While the Swiss sample shows larger absolute gender differences in ideology in line with previous studies (Abendschön & Steinmetz, Reference Abendschön and Steinmetz2014), the gender-generation gap in Germany is relatively larger than in Switzerland.

Dyadic analyses: Parent–offspring similarity in political ideology

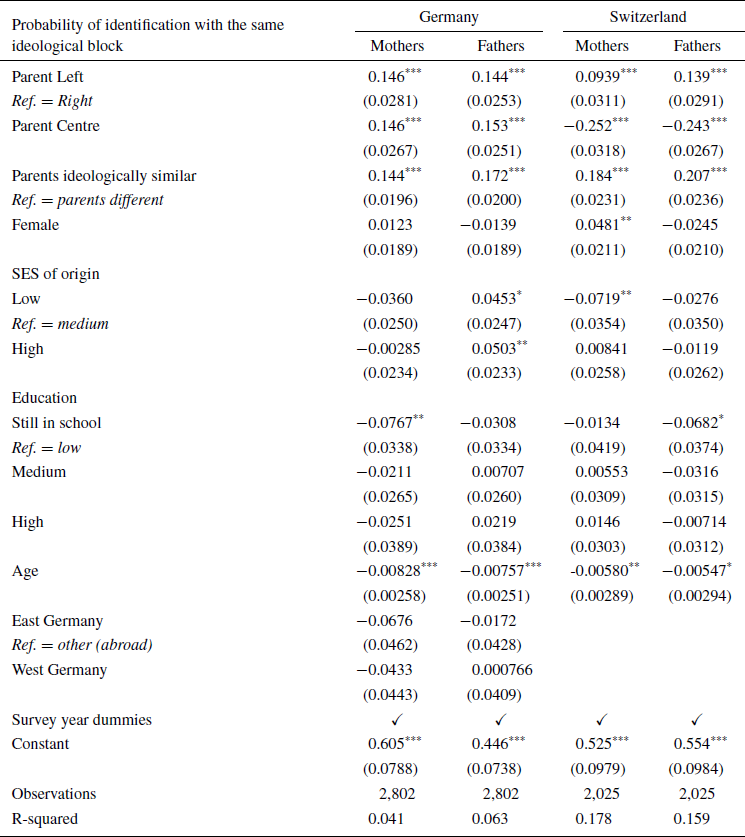

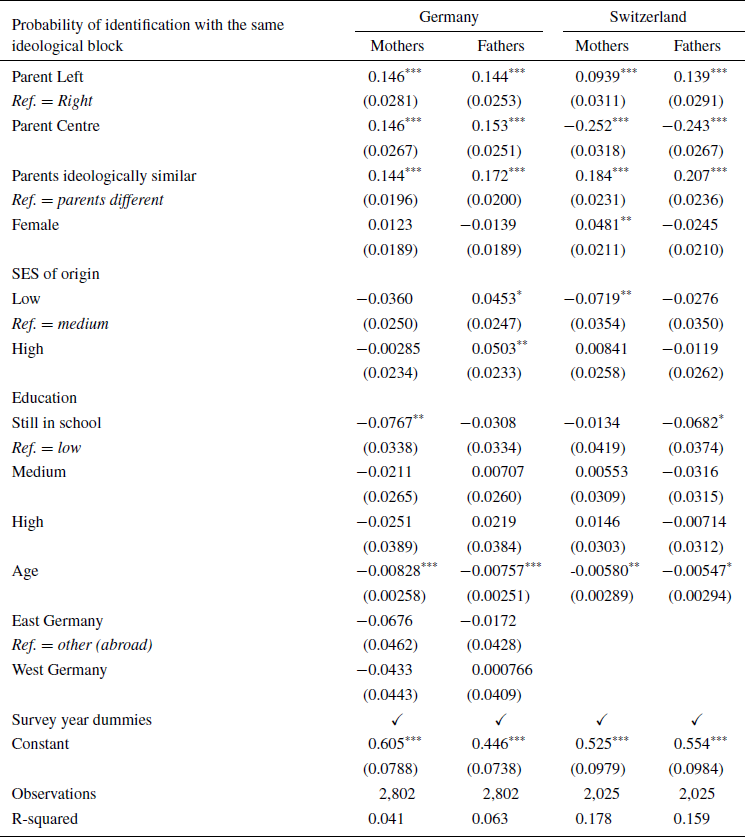

This section presents the results of dyadic multivariate analyses that model the ideological similarity of parents and offspring, separately for mother–child and father–child dyads. Table 4 displays the results of the first baseline model, including several variables at the family, parental and child levels. Positive values indicate a higher probability of respondents to identify with the same ideological block as the parent.

Table 4. Factors predicting parent–offspring similarity in ideological block

Source: Author's calculations using G-SOEP 2005, 2009 and SHP 1999–2017.

Robust clustered standard errors in parentheses.

* p < 0.1;

** p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.01.

First, parental similarity in ideology increases parent–child ideological similarity substantially in all models (up to 20 per cent in the Swiss father-offspring model), in line with Hypothesis 1 that is based on the importance of cue consistency in social learning (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977). Moreover, the results indicate that in both countries a left-wing ideology is more likely to be transmitted than a right-wing ideology (the reference category), by mothers and fathers. Previous research indicates that couples with similar political leanings are also more politicized, and that left milieus have a stronger discussion culture and more strongly value political homogamy (Muxel, Reference Muxel2015a, Reference Muxel2015b). Therefore, ideologically similar parental couples, especially on the left, perhaps more often create household environments that foster ideological transmission. Unfortunately, differences in the extent of politicization and the frequency of political discussion of the households are not available in the data applied here. Relevant differences in intergenerational transmission are also apparent for the centre categories: while in Germany parent–child similarity is enhanced among offspring of centrist parents compared to rightist parents, the reverse is found in Switzerland, where right-wing positions are more transmitted. These results are in line with the descriptive analyses in Tables 1 and 2.

Furthermore, there is one significant effect of offspring gender: the Swiss mother–offspring model indicates that daughters are 5 per cent more likely to place themselves in the same block as their mother, compared to sons. This general, greater similarity between mothers and daughters compared to sons, is in line with the mechanism of same-sex identification and role modelling underlying Hypothesis 2a. At the same time, the analysis shows no support for H2b as there is no statistically significant negative coefficient for females in the father–offspring models. These dynamics are more elaborately tested in the next analysis that distinguishes between the transmission of left- and right-leaning positions. As SES of origin and level of education do not systematically impact parent–offspring similarity, with only a few statistically significant effects in two models, I conclude that there are no pertinent social class or educational differences in ideological transmission. Moreover, a negative effect of age in all models indicates that ideological similarity is lower among older respondents.Footnote 7 Although parental political socialization is lasting until later in life, a decline in its effect by age is in line with existing literature (Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009).

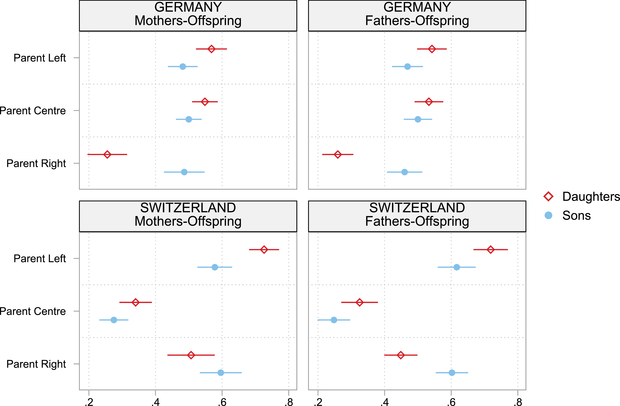

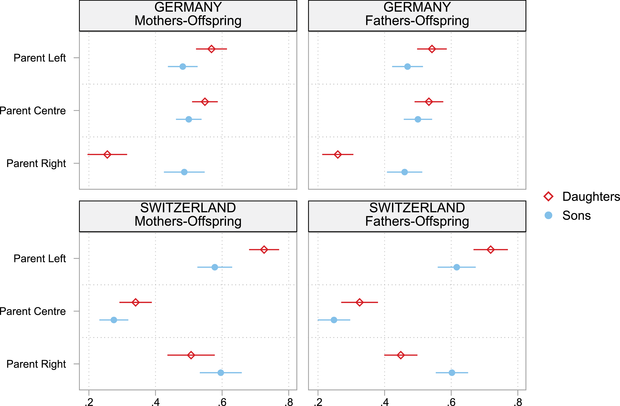

In the next models, I investigate differences between daughters and sons in parent–offspring dyadic similarity in left- and right-wing identification (H2 and H4), by interacting categories of parental ideology with offspring gender. The average predicted probabilities based on the interactions are presented in Figure 1 (regression coefficients available in Table S1 in the Supporting Information). Positive and statistically significant interaction terms with gender in all models indicate significant differences in the probability of taking over parental ideologies by offspring gender, in both countries. As the patterns are similar in the mother–offspring and father–offspring models, these results do not show further support for same-sex patterns (H2). Instead, they are in line with the expected differences in the transmission of left- and right-wing ideologies to, respectively, sons and daughters, as formulated in H4.

Figure 1. Average predictions of parent–offspring similarity in ideological block, by offspring gender (interaction) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Source: Author's calculations using G-SOEP 2005, 2009 (N = 2802); and SHP 1999–2017 (N = 2025).

Regression specification and covariates are as in Table 4, adding an interaction term between parental ideology (categorical) and offspring gender. Regression coefficients are available in Supporting Information, Table S1.

First, there is a generally greater similarity between left-wing parents (both mothers and fathers) and their daughters, compared to sons (H4a). Second, similarity between right-wing parents (again, mothers and fathers) and their sons is greater compared to their daughters (H4b). Importantly, there is a clear asymmetry in the transmission of left-leaning versus right-leaning positions by offspring gender: while sons are equally likely to take over the left or the right ideological leaning of their parents, daughters are more likely to take over leftist positions. Daughters are, especially in Germany, much less likely to take over the rightist position of either parent compared to other ideological leanings.Footnote 8 These patterns also provide support for H5a as left-leaning parents – regardless of their gender – are more successful than right-leaning parents in having a daughter that looks like them ideologically. As sons do not display similar differences, right-leaning parents do not have such an advantage over left-leaning parents (contrary to H5b). In the next analysis, this hypothesis is tested by jointly including the ideology of both parents in the model.

The gender-generation gap thus shows to be consequential for political transmission in families and leads to an important asymmetry in parent–offspring similarity. For young women in the offspring generation, transmission is unequal across ideological leanings of the parents, while this is not the case for sons (aside from differences with the centre category in Switzerland). This signals an active rather than passive role of offspring in the transmission process and underlines the relevance of socialization influences outside the parental home that may be larger for young women than men. A second important result is that left-leaning parents have a comparative advantage over right-leaning parents in having a daughter that looks like them ideologically. The gender-generation gap results in strengthened ideological transmission for left-leaning parents as the socialization forces outside the home are supportive of parent–daughter similarity, while the opposite is true for the transmission of right-leaning ideologies. It means that daughters are generally drifting further away from their parents’ political orientations when they are right-leaning, while this trend is not observed for sons.

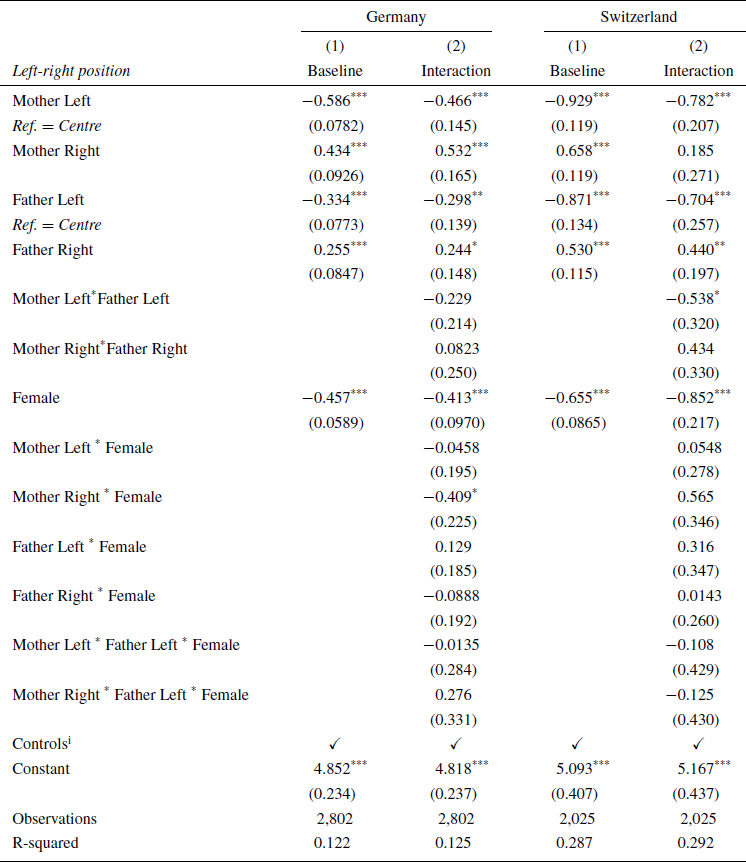

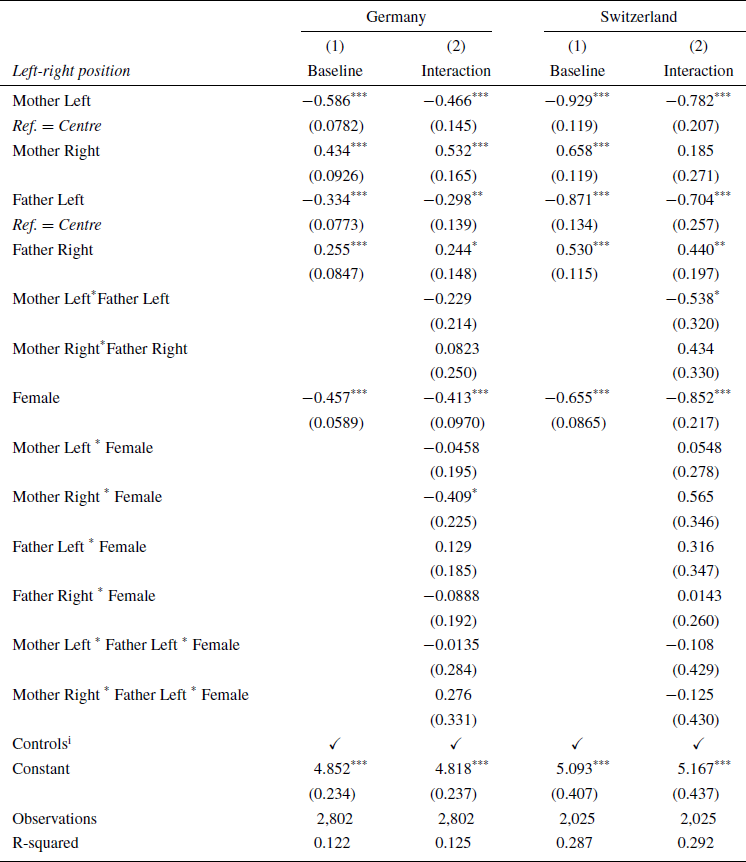

Triadic analyses: Offspring's ideology by combinations of parental ideology

To study differences between parents in terms of their relative impact on their offspring's positioning (H3), their political ideology is jointly included in the triadic analyses presented in Table 5. In contrast to the foregoing analyses, the dependent variable is offspring's left-right position, which allows to predict their ideological positioning across combinations of the parental ideology. This different configuration also provides a more rigorous test of H5, and a replication of the foregoing analysis in testing the other hypotheses. Negative coefficients imply left-wing effects, whereas positive coefficients indicate right-wing effects.

Table 5. OLS regression of offspring ideology on parental ideology

Source: Author's calculations using G-SOEP 2005, 2009 and SHP 1999–2017.

Robust clustered standard errors in parentheses.

i SES of origin, level of education, age, survey year, DE region. All estimates are available in Supporting Information Table S2.

* p < 0.1;

** p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.01.

The first model indicates substantively and statistically significant effects of the parental ideology on their offspring's self-placement when jointly included, in both countries. The generally larger coefficients of parental ideology in Switzerland can be explained by respondents using the entire range of the left-right scale more than in Germany where centrist positions are more common. F-tests that compare the size of coefficients, indicate that in Germany the mother's left-wing coefficient is larger than the father's (p < 0.05) while the right-wing coefficients of both parents are of equal size in both countries. This could point at a more important role for mothers, also found by previous work using the G-SOEP (Zuckerman et al., Reference Zuckerman, Dasovic and Fitzgerald2007), but here only in the transmission of left-leaning positions. The negative coefficient for female indicates the offspring's gender gap in ideology.

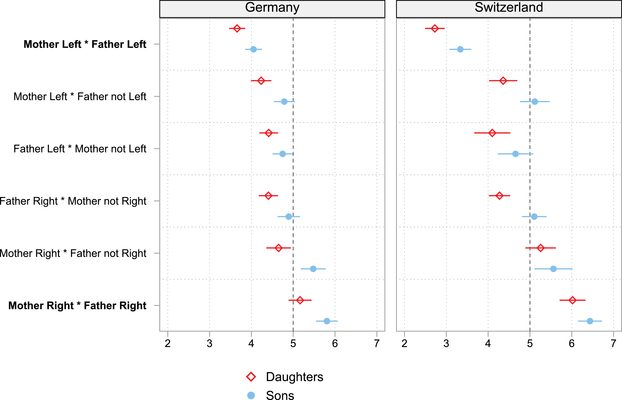

In the second model, the parents’ ideology is interacted with each other and with their offspring's gender, to test H3, comparing the role of both parents in the transmission process. None of the three-way interaction terms are statistically significant, while two other interaction terms are.Footnote 9 In Germany, the impact of the mother's right-wing position is weaker on their daughter's ideological positioning compared to their son's (interaction term of −0.4). This indicates, as in the previous analysis, that daughters are less likely to take over rightist ideologies. In Switzerland, there is a stronger effect of parental left-wing positions when parents are both left-wing (interaction term of −0.5), providing additional support for H1 regarding the impact of parental similarity in ideology. Importantly, the fact that the three-way interaction terms are not statistically significant, means that the ideological differences between sons and daughters do not depend on respective combinations of the parental ideology. These dynamics are further discussed on the basis of the predicted left-right positions of daughters and sons across different combinations of parental ideology presented in Figure 2, estimated using predictive margins based on the interactions.

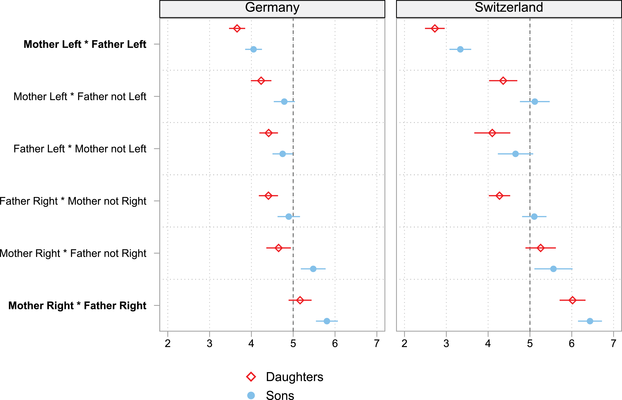

Figure 2. Average predictions of offspring left-right position by combinations of parental ideology and offspring gender (three-way interaction) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Source: Author's calculations using G-SOEP 2005, 2009 (N = 2802); and SHP 1999–2017 (N = 2025).

Bolded categories indicate parents with similar ideological leaning.

Figure 2 shows that the ideological positioning of children from homogamous left-wing and respectively right-wing parental couples most strongly differs from the categories with dissimilar parental leanings (H1), especially in Switzerland where one of the interaction terms is significant. When parents differ in ideology, their offspring generally take less distinct ideological positions and cluster more around the centre, especially sons. Contrary to H3, daughters and sons of ideologically dissimilar parents are not more strongly impacted by the ideology of the same-sex parent. The emerging pattern is that offspring systematically differ in their ideological positioning by gender, as daughters place themselves consistently on the left of sons across almost all combinations of parental ideology, corroborating the support for H4.Footnote 10 Importantly, the average predicted ideological position of daughters in Germany is leftist or centrist across all categories, even when both parents are right-wing. In Switzerland, the only category in which female offspring take right-leaning positions is when both parents are right-wing. This reflects the earlier finding that while sons are equally likely to take over a left- or a right-wing ideology of either parent, daughters are significantly less likely to take over right-wing positions.

As these patterns are mainly the result of the constitutive term for female, we thus cannot speak of one parent being clearly more impactful than the other. Differences are however clearly observed between the different categories of parents’ ideological combinations. The systematic distinct positioning of daughters compared to sons leads to the previously discussed comparative advantage of left-leaning parents over right-leaning parents in having a daughter that looks like them ideologically (in line with H5a), while vice versa, this is not the case for right-leaning parents in having a son of similar ideological leaning (contrary to H5b). The offspring of ideologically dissimilar couples generally show less distinct ideological positioning and cluster more around the centre, especially sons. When one of the two parents is right-leaning while the other is not, a son is not as likely to take right-leaning positions as a daughter is to take left-leaning positions, when one parent is left-leaning and the other is not. The generational change in political positioning of young women turning to the left, therefore, results only in a comparative advantage of left-leaning over right-leaning parents in political similarity with their daughters, and not vice versa of right-leaning parents with their sons.

Conclusion

This study has investigated the transmission of left-right ideology in Germany and Switzerland, testing classic explanations for parent–offspring overlap in ideology, hypotheses regarding same-sex dynamics and new hypotheses regarding the consequences of the political gender-generation gap. The results demonstrate the applicability of the classic family political socialization model to the intergenerational transmission of left-right positions in contemporary Western Europe and how the gender-generation gap is consequential for this process.

While the results are relatively similar across countries, levels of transmission are generally higher in Switzerland than in Germany, due to the tendency of Swiss respondents to use a wider range of left-right positions and cluster less around the centre. Centrist positions are therefore less often transmitted compared to Germany, where respondents more often refrain from taking right-wing stances and a large proportion take centrist positions. An explanation for this difference may be the meaning of left and right across the countries. Earlier studies concluded that in Germany right-wing positions are associated with xenophobic attitudes (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Barberá, Ackermann and Venetz2017; Neundorf, Reference Neundorf2009), and in Switzerland social class is more strongly associated with left-right positions (Medina, Reference Medina2015). These explanations are more likely to underlie the differences in ideological transmission than the differences in party systems discussed in the theory section, as they are in line with the distribution of both generations of respondents over the left-right scale.

This study did not find evidence for same-sex patterns in ideological transmission, which contributes to the already mixed findings regarding such patterns in political socialization. Apparently, when it comes to left-right identification, mothers and fathers are mostly perceived as similarly important role models by their sons and daughters. This may differ for other political traits, such as vote choice, for which previous studies have identified same-sex patterns. Although political ideology and vote choice are strongly associated with each other, in multiparty systems the direct link between the two is less obvious than in two-party systems, as there are usually multiple parties that correspond to a voter's left-right orientation. In translating attitudes into political party preferences, role modelling by the parent of the same gender is perhaps more important than it is for ideological positioning in multiparty systems. Moreover, an explanation for the fact that mothers are not found to be generally more influential in the intergenerational transmission process, compared to some previous studies, may point at a more equal division of labour in households than in earlier decades. Yet, in a few instances this study showed a larger role for the mother: a higher impact of the mother's left-wing positions compared to those of the father in Germany; and higher general mother–daughter similarity in Switzerland. The pattern is however not systematic enough to lead to strong conclusions. This also signals the impact of different modelling strategies when studying ideological transmission, which may contribute to the mixed findings among existing studies.

The most consistent finding of this study, apparent in the dyadic and the triadic analyses in both countries, is that the largest differences in intergenerational political similarity are between daughters and sons, rather than between mothers and fathers. Sons and daughters systematically differ in two important respects. First, daughters take more leftist positions than sons, irrespective of the combination of the parental ideology; and, second, by extension, daughters are less likely to take over rightist positions, while sons are equally likely to take over the parental left- or right-wing ideology. The generational differences found in the first descriptive analyses that lead to left-wing positions being more often transmitted than right-wing positions, are thus mainly driven by young female offspring. Even though transmission by block rather than position on the left-right scale is less subject to generational differences in ideological positioning, these findings do point at a left-wing turn in the younger female generation, with especially larger differences in Switzerland. These findings are in line with previous work demonstrating the gender-generation gap and the larger political gender gap in Switzerland. The intergenerational transmission of ideology from parents to sons demonstrates a more typical form of political socialization, as they do not show different tendencies in taking over the parental views across parental ideological blocks. Daughters, on the other hand, show a very low probability of taking over their parents’ right-wing positions, especially in Germany.

The results of this study have important implications for the mechanisms underlying political socialization. When both parents have similar ideological leanings, patterns are in line with expectations as their offspring usually identifies with the same ideological block. At the same time, this reproduction of the parental ideology is still larger for homogamous left-wing parental couples, especially in Switzerland. When parents are of dissimilar ideological leaning, intergenerational transmission becomes less obvious as their offspring is exposed to conflicting political cues. Therefore, in these cases we can particularly expect the offspring to be more impacted by political socialization forces outside the parental home. The generational change that is moving women to the left sustains the transmission of left-wing ideologies to daughters, while this is not the case for right-wing ideologies to sons. This leads to left-leaning parents, including those in dissimilar couples, holding an advantage over right-leaning parents to have their political ideology reproduced by their, especially female, offspring. Consequently, intergenerational similarity on the right-hand side of the political spectrum is not as affected by period forces and socialization outside the parental home as is the case for left-leaning positions.

Daughters thus appear more strongly than sons to be influenced by factors outside the parental home in developing their ideological leaning. One underlying reason may be the increased societal attention in recent decades for gender equality, which is associated with left-wing positions. Another explanation could lie in different political socialization practices between left- and right-wing households, which differentially impact daughters and sons. Previous work studying such processes in France has shown relevant distinctions in how these respective households deal with political differences, noting a particular tradition of debate among left milieus (Muxel, Reference Muxel2015b). Differences in communication styles and preferences between sons and daughters, that have been previously identified between mothers and fathers (McDevitt & Chaffee, Reference McDevitt and Chaffee2002; Shulman & DeAndrea, Reference Shulman and DeAndrea2014), may also impact the offspring's receiving role in family socialization processes. Left-wing families could, therefore, be particularly successful in fostering similar ideological positions to their female offspring, compared to right-wing families. As this study does not include measures of politicization or frequency of discussion in the respective families, this remains a relevant question to address in future studies.

Future studies may be able to address these questions to further investigate the underlying mechanisms, by studying the political dynamics in households, the perceived importance of the respective parents in the transmission of different political traits, and offspring cohort differences in political gender gaps. This study has demonstrated the relevance of the family in the political self-positioning of individuals and of political ideology as a durable transmission cue, showing similar patterns in Germany and Switzerland. It also underlines the increasing importance of distinguishing by gender in contemporary studies of political socialization when studying political traits that demonstrate gender differences within and between parental and offspring generations. Despite trends of increased individualization, political volatility and perhaps decreased importance of family ties, the family provides an important basis for individuals’ political self-identification. Yet, children are not solely passive recipients in the political socialization process, as demonstrated by the gender differences in the intergenerational reproduction of left- and right-wing positions, that are the consequence of generational processes of further gender realignment.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Alexander Trechsel, Fabrizio Bernardi, Hanspeter Kriesi, Elias Dinas, Andrea De Angelis, Macarena Ares, and four anonymous reviewers of the European Journal of Political Research for their helpful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of (parts of) this article, as well as participants at the 2020 conference of the Swiss Political Science Association.

Open access funding provided by Universität Luzern.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table S1. Parent-child similarity in ideological block by ideology of parent, dyadic models (LPM).

Table S2. Respondent's left-right ideology regressed on parental ideology (OLS).

Replication Code