Introduction

A place in the streets—and at the table. When young people engage in Fridays for Future, eat vegan, and wear second hand clothes, they are demonstrating political engagement and commitment to making a difference. Young people are equally engaged and political interested as other age groups, they support democracy, are satisfied with the political institutions (Sloam Reference Sloam2014), and are engaged in non-parliamentary politics such as social movements and protests (O’Neill Reference O’Neill2007; Cross and Young Reference Cross and Young2008; Mycock & Tonge Reference Mycock and Tonge2012). However, young people seems to be less involved in traditional parliamentary institutions, such as voting and parties (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004; García-Albacete Reference García-Albacete2014) or parties’ youth wings (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004; Kosiara-Pedersen & Harre 2015; de Roon Reference de Roon2020), which indicate that young people are mobilised outside rather than within the established institutions of representative democracy. The purpose of this article is to depict three ideal type models of youth representation, along the recruitment ladder from voters to ministers, and to show the appropriateness of these models with an empirical analysis of the Danish case.

Why does youth representation matter? Representation is a multifaceted phenomenon (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). There are (at least) three arguments for the importance of the descriptive representation of young people: legitimacy, experience and interests. The legitimacy argument is that all groups within the population have the right to participate in decisions that concern them. Political bodies are not legitimate if the representatives do not mirror the represented (Phillips 1995). Secondly, different social groups bring forth varying experiences, life perspectives, and resources. While all older representatives have been young at some point, they are not young ‘now’, hence, they have the experience that comes with age but not the generational experience of young people ‘nowadays’. Third, the representation of youth matters to a country’s political substance, that is, descriptive (social characteristics) and substantive (opinions) representation are linked. Studies have shown clear age differences in e.g., spending priorities (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2013; Mello et al. 2016), and that younger representatives are more likely to represent youth preferences (Curry & Haydon Reference Curry and Haydon2018; Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Cassidy and Troiano2019). These arguments are not exclusive for young people but apply to other social groups as well. ‘Young people’ is not a fixed homogeneous group as they have intersectional identities like other social groups (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989); they vary across class, ethnicity, race etc. However, the focus here is on the representation of youth as a (heterogeneous) group.

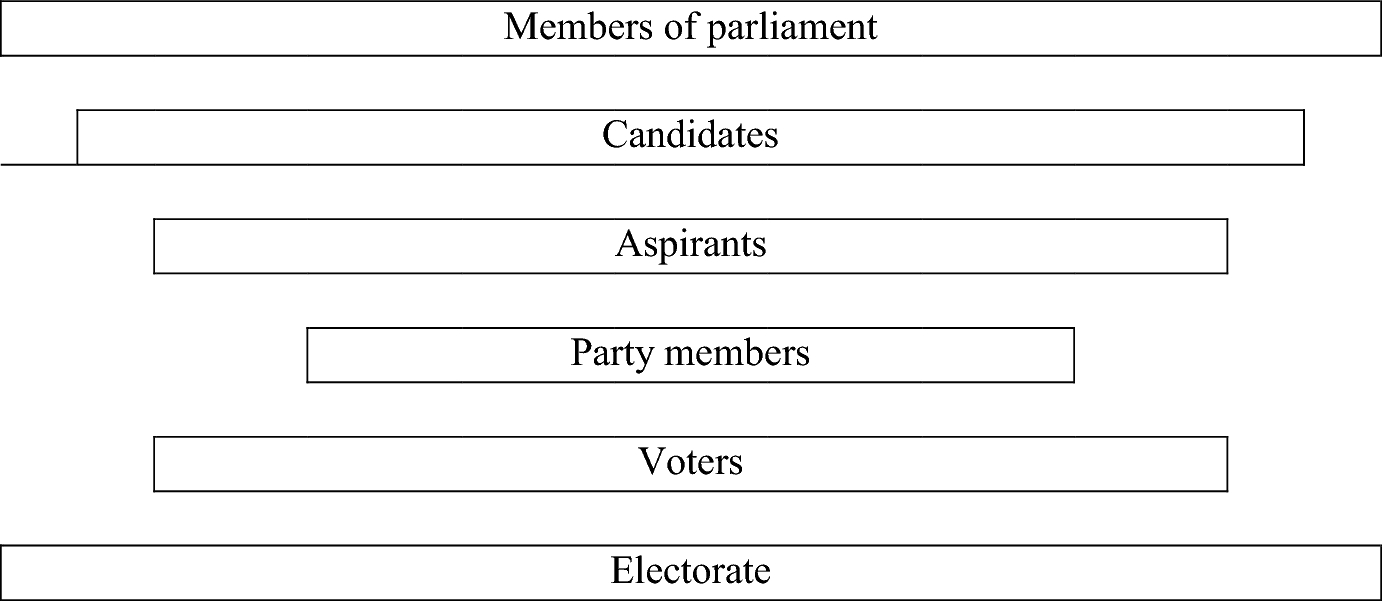

The main and theoretical part of this article is divided in three parts. First, I lay out the basic principles of the recruitment ladder model from both the composition and process perspectives. Then I present three ideal type models of how the youth is represented: the equality, pyramid, and hourglass models. In the last theoretical parts of the article, I discuss the important distinctions between representation at the system and party levels, and at the local, national, and European levels. In the last, empirical part of the article, I show the usefulness of these models. I first present the Danish case and method, whereafter I demonstrate the empirical relevance of the proposed ideal models by applying them to the Danish case. I conclude that the Danish youth recruitment ladder resembles the hourglass ideal type rather than the pyramid or equality types. The young are less likely to vote and to enrol in a party/political youth organization, but more likely to be willing to stand for election. Their representation among both candidates and elected representatives is equal to their share of the population, and they are over-represented in government.

The ladder of recruitment

The ladder of recruitment provides a theoretically useful model when studying the political recruitment of the youth. The process of political recruitment is divided into the phases of mobilisation, nomination, and election, where each phase represents a step up the political hierarchy (Norris & Lovenduski 1995). In their original model of the recruitment ladder, Norris and Lovenduski include five groups: voters, party members, applicants, candidates, and MPs (1995: 16). Their insistence on including several steps in the recruitment ladder was part of a renewed focus on the role of political parties in political recruitment. In the extended ladder of recruitment, Lovenduski (Reference Lovenduski2016) adds important nuances. From the bottom, she first includes citizens as well, indicating that not all citizens are voters. The next addition recognises that there are several steps between voting and enrolling in a party, namely, being first politically interested and then becoming a party supporter. The category of aspirants was also added to recognise that some party members are interested in standing in the intra-party process of candidate nomination, but that not all necessarily do it. Hence, the distinction between aspirants and applicants illuminates the different stages of ambition. Candidates are divided into unwinnable, marginal, and safe seats. Finally, the top of the extended ladder is a seat in government.

The ladder of recruitment may be viewed and applied both from a composition and a process perspective. The composition perspective focuses on the steps themselves; both how large the pool of people at each step is, and who makes up the groups of each step. The essence of the ladder of recruitment model is that, at each step, fewer continue on to the next step. Hence, the closer to the top of the ladder, the fewer people. Various studies contribute to our understanding of the compositions (e.g. socio-demographic factors, political values, and so on) of the groups along the recruitment ladder, ranging from e.g. classic elite studies of MPs (Semenova et al. Reference Semenova, Edinger and Best2015) to studies of voters (e.g. Bengtson et al. 2024), candidates (e.g. Coffé & von Schoultz Reference Coffé and von Schoultz2021) and party members (van Haute and Gauja Reference van Haute and Gauja2015; Heidar and Wauters 2019). The composition perspective provides a first insight into whether the ladder of recruitment is skewed or not, and if so, in what directions. But to truly understand the composition of the steps on the ladder, we need to include the process perspective. The same share of e.g. young people on two steps may be the result of various interactions between the individual’s competences and characteristics on the one hand, and the formal and informal institutions they encounter on the other hand. Supply and demand at each step interact, and a variety of explanations could be relevant. As such, when Sundström and Stockemer (Reference Sundström and Stockemer2021) assess whether youth is represented in parliament equal to its share of the population, they picture the degree of (under-)representation (composition) but overlook the dynamics of recruitment (process).

Individuals may themselves choose to take the first three steps on the recruitment ladder, hence there is a tendency towards focussing on individual choices when explaining turnout, membership and political ambitions. In contrast, the following steps of the recruitment ladder—becoming a candidate for an election and getting elected—are not decided solely by the individuals themselves. While institutions provide the contexts within which individuals vote, enrol and become interested in standing for election, formal institutions matter far more in the following steps.

Three ideal type models of youth representation along the ladder of recruitment

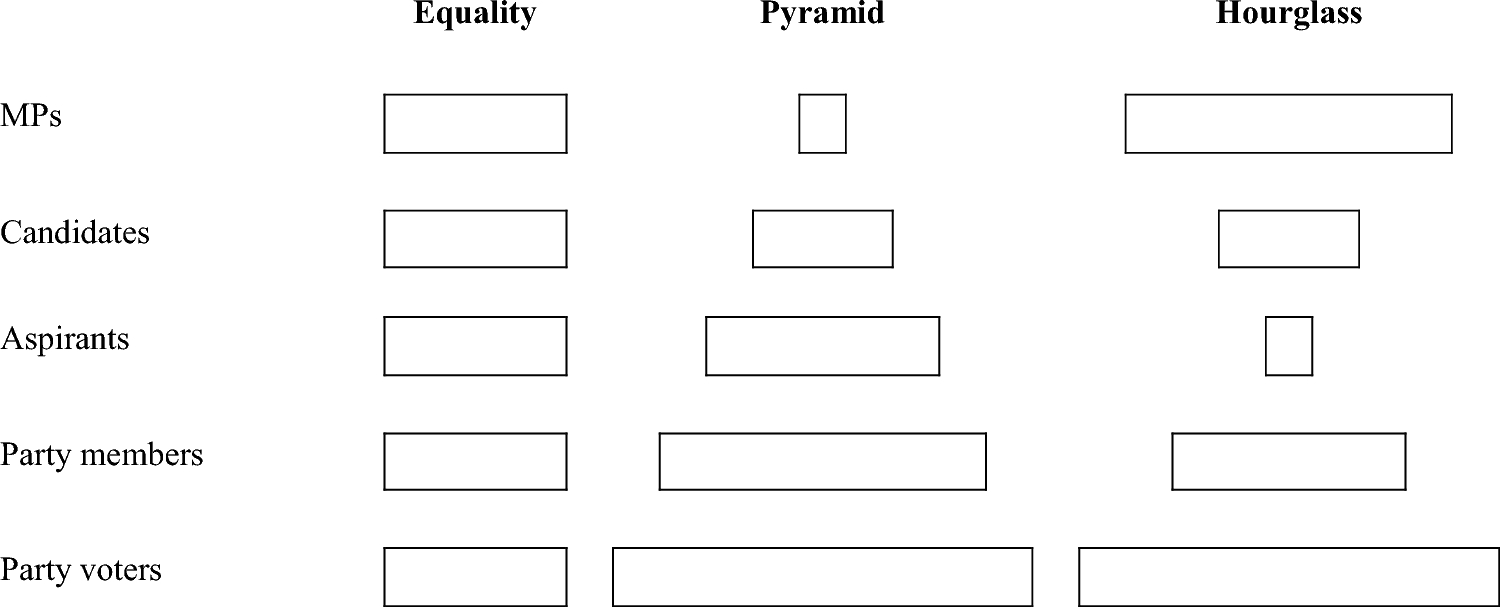

The recruitment ladder provides the basis for three ideal type models of the descriptive representation of the youth: the equality, pyramid, and hourglass models. First, if institutions, structures, and processes neither discriminate against nor favour young people, they will be equally represented on the various steps in the ladder of recruitment. I call this the ‘equality’ model in Fig. 1. This is an ideal type model reached only if institutions, structures, processes and the interaction between these and the individual traits, skills and competences are neutral without (dis-)favouring anybody. To some extent, this could be argued to be a normative ideal in a descriptive representation perspective.

Fig. 1 Three models of youth representation along the recruitment ladder

However, institutions, structures, and processes are often not neutral; they distort by either favouring or disfavouring various individuals and social groups. If institutions, structures, and processes disfavour or even discriminate against young people, the share of young people at these steps will shrink, as argued by Kjær and Kosiara-Pedersen (Reference Kjær and Kosiara-Pedersen2019) in regard to women. The higher towards the top of the political hierarchy, the more majority groups are expected to be over-represented compared to minority groups. This is the essence of Putnam’s law of increasing disproportion (Reference Putnam1976: 33) as well as the idea of minority attrition (Taagepera 1994). The absolute number of people taking each step on the ladder of recruitment decreases towards the top, but more importantly, the argument is that among the political elite, the share of people from under-represented groups declines more than the share of the majority. “The higher, the fewer pattern” (Bashevkin Reference Bashevkin1993) has in particular been studied in a gender perspective, but the arguments may just as well be applied to young people, due to their historical under-representation. This ‘pyramid’ model is shown in Fig. 1.

The dynamics of demand and supply at the various steps may not be the same across the ladder of recruitment. Kjær and Kosiara-Pedersen (Reference Kjær and Kosiara-Pedersen2019) show that for Danish women, the pattern is an hourglass, where the share of women shrinks from voters to members and again to potential candidates. However, the share of women among candidates is higher than it is among potential candidates, and the share of women further expands at the level of MPs. This means that ‘the higher, the fewer’ pyramidal pattern holds only until candidates are ready be nominated, then it becomes ‘the higher, the more’. The same model could be expected in regard to young people, if they, like women, are less likely to enrol in a party and also less likely to want to stand for election, but if parties are reaching out to nominate them in order to diversify their candidate lists, that is, they are favoured in parties’ selection processes, and if voters select them, that is, they are favoured by the electorate. These dynamics create the ‘hourglass’ model in Fig. 1.

It is relevant to know which of the models apply empirically, since it is an indication of how representation works. If a study shows that specific parts of the electorate, e.g. the young, is well represented among candidates and representatives, this does not guarantee that they are also voting, integrated within parties, and as likely to stand for election. Hence, descriptive representation between the bottom and the top of the recruitment ladder does not guarantee a substantial representation at the institutions in between, which are essential to ensure integration into the democratic system.

Note that the absolute size of the steps in Fig. 1 may differ empirically. The important thing in these models is whether a step is relatively bigger or smaller than the one above or below them, as the figure depicts, since this indicates whether a larger or smaller share of the given group, here young people, are under-, over- or equally represented.

Party or system? And what level of government?

These ideal type models of youth representation along the recruitment ladder focus on the relative share of youth, not the absolute level. In country comparative studies, the share of young people in parties and parliament should not be compared across borders without taking the baseline into consideration, as the age distribution of the population varies markedly (Ritchie & Roser 2024). The cross-country variation implies that e.g. a 20% share of MPs may equal descriptive representation in one country but a severe under-representation in another. The baseline is important, and in system-level studies, the baseline is the share of youth in the electorate, that is, of all eligible voters.

The baseline changes a bit in party-level analyses, since parties do not have distinct electorates; in this case, the party voters provide the baseline. Parties are not equally attractive to young voters. Young voters are more attracted to parties on the left- and right-wings (Walczak et al. Reference Walczak, van der Brug and de Vries2012; Zagórski et al. Reference Zagórski, Rama and Cordero2021), to green parties (Lichtin et al. Reference Lichtin, van der Brug and Rekker2023), and to new parties (Brug and Kritzinger Reference van der Brug and Kritzinger2012; Franklin and van Spanje Reference Franklin and van Spanje2012). Similarly, some parties are better at attracting young people among their members than others. For instance, in Italy, young members (under age 35) make up only 13% of the Christian Democrat party but almost 33% of the Five Star movement (Sandri et al. 2015). Party-level analyses enable us to point to whether parties are supporting or hindering youth representation, notwithstanding a high or low level of youth representation among party voters.

In addition to deciding whether to assess representation at the aggregate system level or at the party level, there is a choice about what level of office to study. On the one hand, we can include all levels of government in one system. Both Putnam’s law of increasing disproportion (1976: 33) and Taagepera’s idea of minority attrition (1994) point to studying the system as a whole since all levels are linked; e.g., local government may serve as a training ground for the national level. However, the dynamics may differ across the levels of government. In particular when studying the representation of a specific social group like the youth, the decision-making power of each level is important to consider given the variation in the relevance of each level for young people, e.g. formal education, stipends, affordable housing, or the right to abortion are especially important issues for young people, and these are mostly decided at the national level.

The equality, pyramid, and hourglass ideal type models allow us to provide a picture of youth representation without emphasis only on the absolute number of the youth at each step, but also on where and how youth representation increases or decreases to solve any under-representations (cf. Norris & Lovenduski 1995). Party-level analyses allow us to explore further variation across parties.

Applying the models to the Danish case

Denmark is chosen as a case study since it is a most likely case of a high level of youth integration into parliamentary politics, hence, most likely to produce the ideal type model of equality. Danish schools are cradles for democracy in the sense that a high level of political education is integrated into the formal curriculum. In addition, every other year since 2015, pupils have engaged in the voluntary ‘school election’ [skolevalg] project, where 14–16 year-olds from around half of all Danish schools hold an election. This election is called by the Prime Minister, and students engage in a campaign in which the political parties’ youth organisations play an important part. The process culminates in an election with an election night. Compared to other EU countries, Danish youth political participation lies in the highest quarter (Kitanova Reference Kitanova2020). There is an abundance of political youth organisations across the political spectrum. Political youth organisations are in all but one party (the newly created Moderates) formally independent from their mother parties, but with varying degrees of representation at the mother party’s annual meeting/national committee (Kosiara-Pedersen & Harre 2015). Hence, the term ‘youth wings’ is a bit off in Denmark.

The empirical part of this article is based on existing studies, hence, there is little new data collection and data analysis included here. While existing studies focus on and explain the process at each of the various steps in the recruitment ladder, no study has combined these to provide a complete picture of the composition of youth representation from electorate to government, which is the modest ambition here to show the usefulness of the ideal type models. Hence, the aim is not a comprehensive analysis of youth representation at each step but a depiction of the application of the three ideal types. The implications of this approach are, first, that the ‘young’ definition depends on the studies included, however, it is specified below how the various studies define it. Secondly, the analysis is mainly at the aggregate level, not of each party. Finally, at all steps, there are more indepth studies of the dynamics and composition to dive into elsewhere.

The first step of the recruitment ladder is identical for all parties, in that parties do not have their own electorates (anymore). In cleavage-based politics, parties had certain groups of potential voters they could count on, however, dealignment and electoral volatility have long demolished this link. Furthermore, both international and Danish research shows that turnout increases with age (Fieldhouse et al. Reference Fieldhouse, Tranmer and Russell2007; Bhatti et al. Reference Bhatti, Hansen and Wass2012). At the 2009 Danish municipal elections, turnout increased over the age span of 20 to 60, whereafter it dropped again, and by age 90 it had returned to the same level of turnout as for 20 year-olds (Bhatti & Hansen Reference Bhatti and Hansen2012: 384). In sum, since young people are less likely to vote, they make up a smaller share of the voters than the population above 18 years.

Party membership scholarship shows how party membership is skewed towards older, long educated men (van Haute & Gauja Reference van Haute and Gauja2015; Demker et al. 2019). In a collaborative study of whether parties still represent, conducted in eight western countries, Heidar and Wauters conclude that in “all countries and (nearly) all parties, women, young people, and the lower educated are under-represented when party members are compared with the electorate at large, and also compared with the specific party electorate” (2019: 171). This is also the case in Denmark. Party members are on average older than members, where the 18–40 year-olds make up 20% of members compared to 28% of the population (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2017). There is marked variation across the political spectrum, with the Danish trend following the international voting pattern, namely that the left- and right-wing parties cater more to the young than centre parties. The lowest average ages were found in the left-wing Red-Green Alliance and right-wing Liberal alliance, closely followed by the left-wing Green Left and the centre Social Liberals (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2017).

Since Danish party youth organisations are formally independent from parties, their enrolment needs to be taken into consideration separately when assessing enrolment in party organizations. Membership of party youth organisations does not make up for the lack of young members within the parties themselves. The total number of all members of party-affiliated youth organizations is less than 12,000, which equates to only 1.3% of the 18–29 year-olds among the population. Furthermore, Danish political youth organisations mobilise in particular the 18–22 year-olds and less so those in their later twenties (Kosiara-Pedersen & Harre 2015). Hence, not only are members of party youth organisations a small group, they are also mostly very young, not creating representation for those in their (later) twenties.

Party members make up the recruitment pool from which parties may recruit aspirants and candidates for elections. However, not all members (and not even all those who attend events like the annual meeting) have political ambitions. Rather, we need a specific question on willingness to stand for election to the national parliament if encouraged by their party. When assessing the extent to which age matters for this potential candidacy, controls are made for some of the usual drivers of political ambitions: at the individual level (gender, education, political interest, political efficacy, political socialization) and at the party level. It turns out that younger party members are more likely to report that they would stand for election if encouraged by their party (Kjær and Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kjær and Kosiara-Pedersen2019; Kosiara-Pedersen 2019), so the skewed party enrolment patterns are somewhat ameliorated. The youth’s share of aspirants is larger than their share of party members at large.

In addition, not only parties but also the youth wings or party-affiliated political youth organisations provide critical recruitment pools for political parties (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004; Mycock & Tonge Reference Mycock and Tonge2012; Ødegård Reference Ødegård2014; de Roon Reference de Roon2020; Jalali et al. Reference Jalali, Silvia and Costa2025) as they recruit and train the politically interested youth (Dobbs 2025). Kosiara-Pedersen & Harre (2015) show that among members of the Danish political youth organisations, 60–80% are potential candidates for elected office.

Formal and informal aspects of parties’ candidate selection procedures within are decisive for who make it through intra-party nomination processes (Hazan & Rahat Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Kenny Reference Kenny2013; Bjarnegård 2013). In Danish parties, this is mainly a matter for local or regional party branches, however, there are some centralizing tendencies also (Bille Reference Bille2001). If members of youth organizations want to stand for election, this takes place within the parties; youth organizations do not have the formal right to nominate candidates, but they are actively supporting their candidates within the parties. Turning to those who make it as candidates, analyses based on the Comparative Candidate Surveys including 21 OECD countries show that the number of 18–35 year-olds among candidates is proportionate to their share of the population in 2012–2019 (Belschner Reference Belschner2024). The Danish case follows this international trend since official statistics (Danmarks Statistik 2024) show that at the 2019 election, the 18–29 year-olds were under-represented among the candidates but the 30–39 year-olds were over-represented, on balance making the 18–39 year-olds fairly represented among the candidates as compared to the population at large.

While parties’ nomination processes and decisions are final in closed-list systems, voters decide in open-list systems. Voting behaviour is a common focus area in political science, and a plethora of explanations have over time been uncovered, pointing to a variety of explanations other than candidate characteristics such as age. However, an affinity effect would imply that voters prefer candidates similar to themselves, however voters may also want elected representatives with both life experience and political experience, which works to the disadvantage of young and new candidates (Muthoo & Shepsle Reference Muthoo and Shepsle2014; Magni-Berton & Panel Reference Magni-Berton and Panel2021). Proportional representation favours youth representation, as does a lower eligibility age (Joshi Reference Joshi2013; Sundström & Stockemer Reference Sundström and Stockemer2021; Belschner & Paredes Reference Belschner and Garcia de Paredes2021; Segaard & Saglie Reference Segaard and Saglie2021). The Danish proportional system allows for preference votes, and these are in almost all parties decisive.

In their international study, Stockemer and Sundström (Reference Stockemer and Sundström2022: 116) show that candidates under 40 are less likely to get elected than candidates over 40. Across 18 elections in eight countries in 2012–2017, the young make up a third of the candidates but only a quarter of the elected. However, in four of the 18 countries, this general trend is not supported. In Sweden and to a lesser extent Finland and Chile, the young candidates were more likely to get elected, while the representation is about equal in Norway. The Danish pattern follows that of its Nordic neighbours. Those under 30 as well as those over 60 are under-represented, while both the 30–40, 40–50 and 50–60 year-olds are over-represented in the Danish parliament, Folketinget. Hence, the under-representation of young people depends very much on the definition of young; the youngest in their 20 s are under-represented, making up only 6% of the 175 MPs, but the youngish in their 30 s are over-represented, making up 23% of the MPs (Folketinget 2023).

Finally, the top step in Lovenduski’s extended ladder of recruitment (Reference Lovenduski2016) is a seat in government. Not all parties make it into government, so the eligible pool is on the one hand confined to the parties in government. On the other hand, the number of ministers is low, and some systems even allow ministers from outside parliament. When appointing ministers, prime ministers have a certain freedom to manoeuvre. In the Danish case, in 2019 the Social Democrat minority government had 20 ministers, of which nine were in their 30 s, nine in their 40 s, and two in their 50 s (Kosiara-Pedersen 2020). The oldest was 55, and the average age was around 42; the prime minister was 41, the youngest-ever prime minister in Denmark. When the government was formed in 2019, the average age of the ministers was lower than the average age of the parliamentarians in the previous term: 42 compared to 46 (Folketinget 2023). Furthermore, the share of those in their 30 s is higher among the ministers than among the parliamentarians (45% compared to 23%). If we define young as under 40, then the youth make up 29% of parliamentarians and are still over-represented at 45% of the ministers.

In sum, aggregately, the Danish youth recruitment ladder resembles the hourglass ideal type model rather than the pyramid or equality types, as shown in Fig. 2. The youth (mostly defined as under 40) is less likely to vote and to enrol in a party/political youth organization, but more likely to be willing to stand for election. Their representation among both candidates and elected representatives is equal to their share of the population, and they are over-represented in government. Hence, while the conditions for youth engagement all along the recruitment ladder is highly likely in the Danish case, not even here are young people equally represented among neither voters, members nor aspirants.

Fig. 2 Youth (under 40) representation along the recruitment ladder in Denmark

Conclusion

The recruitment ladder provides a framework for understanding the processes of representation, and who is part of these processes. The equality, pyramid and hourglass depict three ideal type models of how young people are represented along the steps of the recruitment ladder. Empirical analyses of the descriptive representation of young people along the steps of the ladder of recruitment allow us to assess whether their representation is equal at all steps, hence, mainstreaming their political integration; whether it resembles a ‘pyramid’ shape with a smaller share of young people the higher up on the recruitment ladder we look, which is what is expected of groups traditionally not represented/included; or whether we see more of an ‘hourglass’ where young people are better represented among voters and the elected, but make up a smaller share at the steps in between (members, aspirants, and candidates) due to the nature of processes within parties and youth organisations. The ‘hourglass’ model implies that focussing on parties’ role in political recruitment is important, as processes may be hindering youth participation at certain steps.

Existing studies allow us to follow the Danish case across the various steps in the recruitment ladder, where the results show that youth representation depicts an hourglass. The Danish youth is less likely to vote and to enrol in a party, but more likely to be potential candidates; they are well-represented among the candidates; and their share of representatives (if the youth is defined as under 40) is equal to their share of the population. Interestingly, the hourglass of youth representation in the Danish case differs from the hourglass of Danish gender representation (Kjær & Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kjær and Kosiara-Pedersen2019). In the case of women, the smallest relative representation is among potential candidates, and women’s representation in parliament is smaller than it is among the electorate, whereas the measures to increase women’s representation should focus on getting women interested in standing for election, for youth representation, the focus needs to be on how parties organise, including how they recruit members and supporters. Young people are insufficiently integrated in political parties, which have a unique linkage role in parliamentary democracies.

Political parties are central in parliamentary democracies due to their role in political recruitment. They provide a unique linkage between the elected and electorate. The challenge is how parties are to organise in a way that caters also to young people. Parties could organise to allow individualisation and ad hoc political engagement strong enough for young people to be willing to commit to take part in and stand for elections both within and for this party community. An unequal pipeline depicts a need for both new and established parties to reconsider how they engage, mobilise, and recruit. In sum, if we want young people at the table and not only in the streets, we need to ensure that all elements—the chair, the table, and the company around the table—are welcoming and fit their needs.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ulrik Kjær for collaboration on Kjær & Kosiara-Pedersen (2019), which inspired this article, and to the participants at the conference ‘Youth without representation: Discovering the mechanisms behind youth’s underrepresentation in elected bodies’ in September 2022 at the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa, organized by the Youth Political Representation Research Network, as well as the journal reviewers for constructive feedback.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University.

Data availability

Manuscript has no associated data.

Declarations

Conflict of interest On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest