I. Introduction

Many scholars and policymakers believe that opportunistic trading by corporate insiders erodes outside investors’ confidence in the fairness and integrity of financial markets, and if left unchecked, this practice may even lead to market failures.Footnote 1 Therefore, there is ongoing interest in understanding the impact of regulatory mechanisms aimed at deterring insider trading. However, empirical evidence on the efficacy of insider trading regulations has been mixed. Some studies find that these regulations have effectively reduced the frequency and profitability of opportunistic trades (e.g., Agrawal and Jaffe (Reference Agrawal and Jaffe1995), Garfinkel (Reference Garfinkel1997), and Xu (Reference Xu2008)), while others cast doubt on their efficacy (see, e.g., Jaffe (Reference Jaffe1974), Seyhun (Reference Seyhun1992), and Banerjee and Eckard (Reference Banerjee and Eckard2001)).

The mixed findings on the impact of insider trading regulations can be partly attributed to the lack of strong identification techniques that can isolate the causal effect of litigation risk on insider trading. Identification is particularly challenging because most modern insider trading laws in the United States are adopted at the federal levelFootnote 2 and affect all firms simultaneously. Moreover, regulatory reforms are rarely random and often follow heightened concerns about illegal insider trading activities. The lack of adequate cross-sectional variation and potential endogeneity of regulatory changes limits the ability of existing studies using federal regulations to establish causality. For example, a decrease in insider trading following the passage of a stricter law may simply reflect mean-reversion after a period of rampant insider trading that prompted the law. Studies focusing on enforcement intensity and court decisions (e.g., Cheng, Huang, and Li (Reference Cheng, Huang and Li2016), Del Guercio, Odders-White, and Ready (Reference Del Guercio, Odders-White and Ready2017)) face similar limitations. Accordingly, Bhattacharya (Reference Bhattacharya2014) concludes his extensive review of the insider trading literature with the verdict that “We need methodologies (such as natural experiments) to evaluate the efficacy of current and future insider trading rules.”

This article attempts to fill this important gap in the literature. We exploit the staggered adoption of Universal Demand (UD) laws in 23 U.S. states and the District of Columbia over 23 years to examine the effect of shareholder litigation risk on opportunistic insider trading. Our research is motivated by recent studies that find that UD laws significantly reduce shareholders’ ability to bring derivative lawsuits (DLs) against directors and officers (D&O) for breach of their fiduciary duty to the company (see, e.g., Davis (Reference Davis2008), Houston, Lin, and Xie (Reference Houston, Lin and Xie2018), and Appel (Reference Appel2019)).

How do UD laws affect insider trading? DLs, which typically allege that D&O breached their fiduciary duty, often also include allegations of insider trading (see Erickson (Reference Erickson2010)), especially insider selling. Prior studies find that D&O misconduct is much more likely to result in shareholder lawsuits when it is accompanied by evidence of insider trading by D&O (see, e.g., Johnson, Nelson, and Pritchard (Reference Johnson, Nelson and Pritchard2007)). This is partly because insider trading by D&O strengthens the evidence that the primary alleged wrongdoing was deliberate and financially motivated. Therefore, the threat of DLs should deter insiders from trading opportunistically.Footnote 3 Houston et al. (Reference Houston, Lin and Xie2018) and Appel (Reference Appel2019) estimate that the adoption of a UD law decreases the annual probability of DLs against a firm by as much as about one-half, and decreases in DLs are not substituted by increases in direct shareholder lawsuits. Therefore, we posit that by making it harder to bring DLs, UD laws enable insiders who are subject to derivative lawsuits (i.e., D&O) to trade more opportunistically.

States’ adoption of UD laws serves as excellent quasi-natural experiments to study the effect of regulation on insider trading for two reasons. First, the staggered adoption of UD laws by different states over many years provides rich time-series and cross-sectional variation in the ex ante probability of shareholders bringing DLs. Second, UD laws satisfy both the relevance and exclusion restrictions for a natural experiment in our setting. The relevance condition is met because, as discussed in Section II.A. UD laws dramatically reduce the empirical probability of DLs by imposing a demand requirement that significantly hinders the possibility of a successful lawsuit, regardless of the board’s response to the demand.Footnote 4 The exclusion restriction is satisfied because most states appear to have adopted these laws for reasons largely unrelated to concerns about insider trading. This makes the passage of UD laws plausibly exogenous to preexisting levels and profitability of insider trading.

Our empirical methodology builds on recent studies such as Bertrand and Mullainathan (Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2003), Gormley and Matsa (Reference Gormley and Matsa2016), and Appel (Reference Appel2019) that employ multiple exogenous shocks for identification to make causal inferences. We create treatment and control groups using indicator variables based on the timing of adoption of UD laws by firms’ states of incorporation. We then employ difference-in-differences (DiD) regression specifications to estimate the effect of the ex ante threat of shareholder litigation on the volume and profitability of insider trades.

Using our full sample of trades by D&O, we analyze the effect of UD laws on these trades’ profitability as measured by buy-and-hold abnormal return (BHAR).Footnote 5 Our DiD regressions show that compared to control firms, the D&OFootnote 6 of treatment firms avoid average losses of about 2.6%, 2.8%, and 3.4% in BHAR over 1, 3, and 6 months, respectively, following a sale. These DiD estimates are also economically meaningful. These incremental abnormal returns after UD law adoptions are larger in magnitude than the mean abnormal returns (i.e., loss avoidance) of 0.5%, 1.3%, and 1.9% over the corresponding periods for all insider sales in our sample. They translate into insiders avoiding incremental abnormal dollar losses after UD law adoption of about $27,000 and $52,500 in constant 2013 dollars over 1- and 3-month periods compared to the corresponding values of $2,500 and $7,700 for all insiders. Although the absolute amounts of loss avoidance may still seem modest for highly paid executives, this is perhaps not surprising given that UD laws are not specifically targeted at insider trading. Note that this evidence by itself cannot distinguish between two plausible explanations of our findings: i) insiders exploit negative private information more aggressively after UD laws or ii) insiders are less hesitant to engage in legitimate trades when the threat of shareholder lawsuits decreases. Our later tests try to separate between the two stories.

In our full sample, the evidence on the effect of UD laws on the profitability of insider purchases in terms of BHAR is insignificant. However, insiders’ abnormal dollar profits on purchases, which account for both trade size and subsequent returns, increase significantly after UD laws over 1- and 3-month holding periods.

We conduct a number of additional tests to understand how UD laws affect the timing and opportunism in insider trades. We find that UD laws predict increases in the dollar value of shares sold within a given period, but not the number of shares. This finding suggests that after UD laws, insiders increase the dollar value of their individual sales transactions, timing them to avoid subsequent underperformance relative to risk-adjusted benchmarks. Furthermore, UD laws lead to a higher ratio of opportunistic sales to routine sales, as defined by Cohen, Malloy, and Pomorski (Reference Cohen, Malloy and Pomorski2012). We also analyze trades before quarterly earnings announcements (pre-QEA trades), which are particularly opportunistic (see, e.g., Ali and Hirshleifer (Reference Ali and Hirshleifer2017)). We find that after UD law adoption, pre-QEA sales become more profitable over 1- or 3-month horizons. Moreover, insiders significantly increase pre-QEA sales only before negative earnings surprises after the adoption of UD laws. Overall, these results suggest that a decrease in shareholder litigation risk deters more opportunistic behavior by insiders.

Our cross-sectional tests suggest that insiders’ ability to benefit from UD laws depends on firm characteristics that facilitate opportunistic trading. Accordingly, UD laws lead to more profitable insider sales in i) firms with lower monitoring by institutional blockholders and ii) smaller firms, which have fewer alternative governance mechanisms (e.g., company policies against insider trading) in place.

Finally, we conduct a rich set of robustness checks of our main results. First, to mitigate potential biases from an unbalanced panel and time-varying treatment effects, we replicate our baseline model using a cohort-level stacked DiD approach. Second, we show that our conclusions are robust to alternative ways of estimating the profitability of trades. Third, we confirm that our results are robust to Heath, Ringgenberg, Samadi, and Werner’s (Reference Heath, Ringgenberg, Samadi and Werner2023) critique about reusing natural experiments. Specifically, as we discussed previously, UD laws appear to satisfy both the relevance and exclusion restrictions for a natural experiment in our setting. We also confirm the statistical significance of our tests that account for multiple hypothesis testing based on the number of previously published studies using the experiment. Fourth, our findings are not affected by the recent financial crisis. Fifth, our results also remain intact when we control for potential confounding effects of many other state laws important for corporate governance and ex ante litigation risks. Finally, our results remain similar when we drop all firms located in states under the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit Court to disentangle the effect of a 1999 court decision that restricted shareholders’ ability to bring securities class action lawsuits.

We find strong and consistent evidence throughout our analysis that insider sales become more profitable (relative to benchmarks) after UD laws, while there is no consistent result for purchases. This asymmetry can be explained by the nature of derivative lawsuits. The premise of a DL is a breach by D&O of their fiduciary duty (of care, loyalty, and obedience),Footnote 7 which often entails negative information or harm to the company. By decreasing the threat of shareholder lawsuits, UD laws enable D&O to misbehave in ways that can harm the firm, for example, by earnings manipulation, self-dealing, or neglect. Knowledge of this negative information or harm also provides insiders an opportunity to sell stock based on their private information. Accordingly, many DLs include evidence of insider sales as a secondary complaint, as we discuss in Section II.B. Of course, opportunistic insider trading by D&O, by itself a breach of their fiduciary duty of loyalty to the company and its shareholders, is an issue in some shareholder lawsuits, which explains why we also find evidence of an increase in the profitability of insider purchases in certain cases. The asymmetric impact of UD laws on insider selling versus buying highlights the role of litigation risk in deterring insiders from exploiting negative private information more than positive information.

This study makes several contributions to the literature. First, it contributes to the literature discussed in the first two paragraphs of this section on the efficacy of regulations in deterring opportunistic insider trades. Our novel contribution is our identification strategy, which uses plausibly exogenous shocks to ex ante litigation risk due to states’ staggered adoption of UD laws. As discussed earlier, our approach is more suitable for establishing causality than those of many previous related studies which rely on federal laws.

Second, our evidence challenges a view, especially prevalent in the legal literature, that shareholder litigation is often frivolous and imposes a deadweight loss on the firm (see, e.g., Romano (Reference Romano1991), West (Reference West2001)). Our evidence suggests that shareholder litigation threat plays a role in deterring some forms of opportunistic insider trading and provides evidence that private enforcement mechanisms can complement public enforcement of insider trading rules.

Third, our article is related to recent papers that examine various economic effects of the adoption of UD laws. Houston et al. (Reference Houston, Lin and Xie2018) find that UD laws, which make it harder for shareholders to bring DLs, result in a higher cost of capital for firms due to a decrease in information quality, greater risk-taking, and a higher level of insider trading. Boone, Fich, and Griffin (Reference Boone, Fich and Griffin2023) find that UD laws lead to more opaque financial reporting and a worse information environment. Our article complements these studies by focusing on how UD laws affect insiders’ incentives for opportunistic trading and provides an in-depth analysis of the resulting changes in the profitability of insider sales and purchases.

Our article is also related to a concurrent working paper by Jung, Nam, and Shu (Reference Jung, Nam and Shu2021), who analyze the volume of opportunistic insider trading after UD laws, while we analyze both its profitability and volume, both for all insider trades and pre-QEA trades. Our evidence indicates riskier trades and more opportunistic timing as the drivers of higher profitability after UD laws. Jung et al. argue that while direct lawsuits are likely to be effective mainly against sales, DLs can also be effective against opportunistic insider purchases because they are based on a breach of fiduciary duty and do not need to show economic injury to shareholders. But they find (in their Tables 4 and 5) that the volume of opportunistic sales increases much more than purchases after UD laws, which reduce the threat of DLs. Our article complements theirs by showing that the profitability of insider trades increases after UD laws, particularly for sales. Moreover, our research is the first to dig into the question of whether derivative lawsuits complain about insider sales or purchases, an issue on which there appears to be no empirical evidence. Our hand-collected preliminary evidence suggests that allegations of opportunistic purchases rarely show up in derivative lawsuits (see Section II.B), which can explain why our empirical evidence of an increase in the profitability of opportunistic sales after UD laws is much stronger than the evidence on opportunistic purchases.

Fourth, our study contributes to an important but often overlooked issue of public versus private enforcement of opportunistic insider trading. Most prior studies focus on public enforcement of illegal insider trading, that is, prosecution by regulators such as the SEC and the Department of Justice (DOJ), based, for example, on SEC Rule 10(b)-5, ITSA, and ITSFEA. Agrawal and Nasser (Reference Agrawal and Nasser2012) conjecture that private enforcement (e.g., by shareholder lawsuits) can sometimes be more effective than public enforcement in deterring opportunistic insider trading.Footnote 8 This is plausible because, for insiders of most firms, the risk of being sued by shareholders is higher than the risk of being sued by regulators. Regulators such as the SEC have limited staff and resources, so they are outgunned in monitoring and enforcing insider trading laws against numerous potential insiders in a large number of public companies. Therefore, regulators tend to focus their monitoring and enforcement efforts on a few high-profile cases that are likely “slam-dunks” and likely to generate substantial media coverage (see, e.g., Dechow, Sloan, and Sweeney (Reference Dechow, Sloan and Sweeney1996), Agrawal and Chadha (Reference Agrawal and Chadha2005), and Agrawal and Cooper (Reference Agrawal and Cooper2015)). While that may be an effective strategy for a resource-constrained regulator, it is unlikely to deter all, or even most, insider trading. Because DLs are filed by shareholders against corporate insiders, our evidence here that roadblocks against shareholder lawsuits increase insider trading profits speaks to the efficacy of private enforcement in deterring opportunistic insider trading.

Finally, our article also contributes to the literature on corporate governance. Specifically, our study complements several recent studies that exploit exogenous shocks to establish causal effects of litigation risk and new laws on corporate governance and firm value (see, e.g., Bertrand and Mullainathan (Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2003), Gormley and Matsa (Reference Gormley and Matsa2011), (Reference Gormley and Matsa2016), and Appel (Reference Appel2019)).

II. Background, Literature Review, and Hypothesis Development

A. DLs, UD Laws, and Insider Trading

A DL is filed by a shareholder against D&O on behalf of the company for breach of their fiduciary duties of loyalty (e.g., fraud, mismanagement, earnings manipulation, accounting irregularities, self-dealing, or dishonesty) or care (e.g., negligence to timely disclose pertinent, especially negative, information to investors). DLs can be a potent check on the behavior of D&O, who face a high risk of incurring out-of-pocket expenses because state laws typically do not allow firms to reimburse D&O for losses in cases involving misconduct (e.g., criminal or fraudulent activities) or illegal profits, nor are these losses covered by D&O insurance (see, e.g., Willis (2005), Lin, Officer, and Zou (Reference Lin, Officer and Zou2011), Embroker (2019), and Jung et al. (Reference Jung, Nam and Shu2021)). Moreover, lawsuits and the underlying misconduct can cause insiders to lose their positions in the company and damage their reputation in the labor market (see, e.g., Agrawal, Jaffe, and Karpoff (Reference Agrawal, Jaffe and Karpoff1999), Ferris, Jandik, Lawless, and Makhija (Reference Ferris, Jandik, Lawless and Makhija2007), Karpoff, Lee, and Martin (Reference Karpoff, Lee and Martin2008), and Brochet and Srinivasan (Reference Brochet and Srinivasan2014)).

To have the standing to bring a DL, the plaintiff usually needs to have been a shareholder at the time of the wrongdoing by the insider. But in some cases, these lawsuits can be brought by attorneys themselves, who simply have to buy one share to become a shareholder before bringing a lawsuit, as in section 16b cases (short-swing rule; see, e.g., Agrawal and Jaffe (Reference Agrawal and Jaffe1995)).

To initiate a DL, most states require an eligible shareholder to file a demand on the board (known as the “demand requirement”) to sue the alleged wrongdoers. Shareholders can initiate derivative suits themselves only if the board refuses the demand or does not act on it. However, because DLs typically name all or most of the board members as defendants, the board is obviously not eager to act on the demand! So, boards typically ignore the demand or appoint a board committee, which sits on it for months before declaring that it looked into the matter and found no wrongdoing. Therefore, many jurisdictions allow an exception to the demand rule, known as a futility exception. The standards for determining futility vary across jurisdictions (see, e.g., Swanson (Reference Swanson1992)). For example, Delaware has a two-prong test requiring shareholders to allege “particularized facts” that create a reasonable doubt that: i) the directors are disinterested and independent and ii) the challenged transaction was a product of a valid exercise of business judgment (Kinney (Reference Kinney1994)). While that sets a high hurdle for bringing a DL, in the wake of corporate scandals such as Enron and Worldcom and the adoption of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002, Delaware made it easier for shareholders to bring DLs (see, e.g., Jones (Reference Jones2004), Qi and Pederson (Reference Qi and Pederson2019)).

The critics of demand futility argue that the demand requirement allows management to address shareholder allegations and provides a chance to either take corrective action or reject the proposed action. Besides, the demand requirement helps to resolve a dispute without costly litigation (see, e.g., Swanson (Reference Swanson1992)). The American Law Institute (ALI) and the American Bar Association (ABA) advocated the need for ending the futility exception. ABA (2008) proposed a demand requirement in all derivative actions (Universal Demand) in its Model Business Corporation Act (MBCA). In response to MBCA, 23 states plus DC have adopted UD laws from 1989 to 2011.

The demand requirement, imposed on all DLs against companies incorporated in a state by its adoption of a UD law, significantly reduces shareholders’ incentive to bring a DL by substantially reducing the chances of a lawsuit succeeding. Boards obviously do not want to be sued! So, they either simply reject the demand or appoint a special committee that can (pretend to) investigate the matter endlessly.Footnote 9 And courts almost always side with the board’s decision. This happens because if the board refuses the demand, courts can typically only review if the board failed to exercise a valid business judgment (Pinto and Branson (Reference Pinto and Branson2013), and Appel (Reference Appel2019)). If the court ascertains that a majority of the board or the special committee is independent (which is true in most cases), they will dismiss the suit (Kinney (Reference Kinney1994)). Empirically, Houston et al. (Reference Houston, Lin and Xie2018) and Appel (Reference Appel2019) find that the probability of DLs indeed decreases substantially after a state adopts a UD law. Thus, time variation in the adoption of UD laws by different states leads to time-series and cross-sectional variations in shareholders’ ability to bring DLs against insiders for breach of their fiduciary duties (Davis (Reference Davis2008), Appel (Reference Appel2019)).

DLs typically allege that D&O breached their fiduciary duty. In addition, they often include allegations of insider trading (in about 60% of the cases; see Erickson (Reference Erickson2010)).Footnote 10 Evidence of insider trading, which is publicly available due to the Section 16a reporting requirement, serves to establish a motive for D&O to engage in the alleged wrongdoing involving the company and increases the odds of the shareholder lawsuit succeeding (see, e.g., Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Nelson and Pritchard2007), Choi, Nelson, and Pritchard (Reference Choi, Nelson and Pritchard2009)). The most common type of settlement in a DL is governance reform, rather than monetary compensation (see, e.g., Ferris et al. (Reference Ferris, Jandik, Lawless and Makhija2007), Erickson (Reference Erickson2010)), although there have been several large dollar settlements.

States claim to have adopted UD laws primarily to discourage frivolous lawsuits and to allow boards to take corrective actions instead of immediately facing lawsuits. Importantly, their decision to adopt UD laws appears largely unrelated to concerns about insider trading. This feature makes the adoption of UD laws an ideal quasi-natural setting to test the effect of shareholders’ litigation risk on insider trading because UD laws are mostly free from concerns about reverse causality concerning insider trading. Thus, our approach contrasts with those of most previous studies, which rely on federal laws or court decisions specifically designed to address elevated concerns about opportunistic insider trading.

B. Are DLs More Relevant for Opportunistic Insider Sales or Purchases?

As discussed in Section I, a DL is filed by a shareholder against D&O on behalf of the company for breach of their fiduciary duties to the company. These breaches often result in harm to the company. The primary claims of harm are often accompanied by claims that insiders sold stock to avoid losses from the harm. The additional evidence of insider trading by D&O increases the merit of a lawsuit and therefore increases the probability of its being filed (see, e.g., Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Nelson and Pritchard2007)).

An example is a derivative action brought by Citigroup Inc.’s shareholders against the company’s current and former D&O in 2009.Footnote 11 This lawsuit alleges that the D&O committed five types of wrongdoing in connection with Citigroup’s mortgage-related losses: i) breached fiduciary duties of care and loyalty by allowing Citigroup to knowingly make risky mortgage-related investments, ii) failed to inform shareholders of Citigroup’s subprime exposure, iii) wasted corporate assets by repurchasing stock, iv) committed securities fraud by making or authorizing misleading statements that omitted the extent of Citigroup’s investment in subprime mortgages, and v) some defendants committed insider trading by selling Citigroup stock while in the possession of material, nonpublic information.

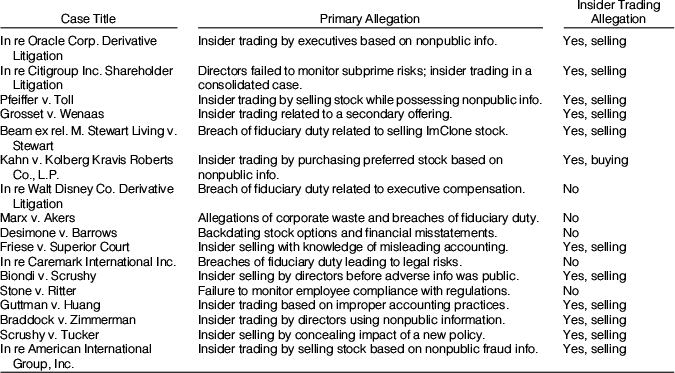

Clearly, in this case, the complaint about insider trading is about sales. But do DLs that include complaints of insider trading typically complain about insider sales or purchases? We cannot find any empirical evidence on this issue. To shed some light on this question, we take two tacks. First, we did a search on Google Scholar Case Law in August 2024, using the following search terms: “insider trading” + “derivative action” OR “derivatively” OR “derivative litigation” but without specifying purchases or sales. The search covered all state courts for our sample period of 1996–2013. We then carefully read the case files of the top 20 search results listed by relevance and summarize our findings in Table A5. The complaint in 11 (1) of these cases includes allegations of insider sales (purchases).Footnote 12 This limited evidence suggests that DL cases that include complaints about insider trading are more likely to complain about insider sales, rather than insider purchases, even though opportunistic purchases also involve a breach of fiduciary duty of loyalty or obedience and can be a subject of DLs. Second, we find that many of the high-profile DLs reported by the media that involve allegations of insider trading are also predominantly about sales.Footnote 13

Jung et al. ((Reference Jung, Nam and Shu2021), pp. 3–4) point out that direct shareholder lawsuits, which require proof of economic injury to the plaintiffs, are difficult to pursue against informed insider purchases, which usually occur before good corporate news events. But DLs can still be brought here because such trades involve a breach of D&Os′ fiduciary duty. On the other hand, both direct lawsuits and DLs can be brought against insider sales. Therefore, DLs can potentially affect insider sales and purchases differently. But whether DLs are more effective against insider sales or purchases is unclear a priori.

C. Are Direct or Derivative Shareholder Lawsuits More Effective Against Insider Trading?

Shareholders often prefer to bring direct lawsuits because any monetary compensation goes directly to them, instead of the company as in DLs. But direct lawsuits require evidence of direct harm to the plaintiffs, which is hard to show in cases involving insider purchases, whereas DLs only need to allege breach of fiduciary duty. So, except for the demand requirement, there is a lower hurdle to pursue a DL. Moreover, plaintiffs often file both types of lawsuits to increase their chances of a favorable verdict or settlement. Appel (Reference Appel2019) shows that DLs are generally as prevalent as direct shareholder lawsuits (often filed as class actions) against public companies.

D. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

A large literature in law and finance finds that legal protection of shareholder rights is an important mechanism for reducing agency problems between managers and shareholders (see Shleifer and Vishny (Reference Shleifer and Vishny1997) for a review). But a sizeable legal literature argues that most shareholder litigation is frivolous and mainly benefits lawyers and insurance companies. A common theme in this literature is that DLs are brought not so much to protect shareholder interests, but rather by plaintiffs’ attorneys hoping to extract settlement fees. D&O are usually reimbursed for any financial liability either by the company or by D&O insurance. Therefore, D&O do not bear much financial risk for their misbehavior. Consequently, litigation threat does not really deter managerial misbehavior (see, e.g., Romano (Reference Romano1991), Weiss and Beckerman (Reference Weiss and Beckerman1995), Coffee (Reference Coffee2006), Baker and Griffith (Reference Baker and Griffith2008)).

But many empirical studies find that DLs have important effects, especially on corporate governance. Ferris et al. (Reference Ferris, Jandik, Lawless and Makhija2007) find that boards improve on several dimensions following DLs. More recently, several studies find that a reduction in the threat of shareholder litigation leads to less institutional blockholding and weaker internal governance provisions (see, e.g., Crane and Koch (Reference Crane and Koch2016), Appel (Reference Appel2019), and Huang, Roychowdhury, and Sletten (Reference Huang, Roychowdhury and Sletten2020)). Weaker corporate governance, in turn, leads to an increase in corporate misconduct such as hoarding of negative news, earnings management (see, e.g., Houston, Lin, Liu, and Wei (Reference Houston, Lin, Liu and Wei2019), Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Roychowdhury and Sletten2020)), a deterioration in firms’ information environment (e.g., Boone et al. (Reference Boone, Fich and Griffin2023)), and ultimately an increase in firms’ cost of capital (see Houston et al. (Reference Houston, Lin and Xie2018)).

In the context of insider trading, many studies find that corporate insiders face real litigation risk and take costly actions to circumvent it. For example, Cheng and Lo (Reference Cheng and Lo2006) find that insiders strategically time changes in firm policies to maximize their profits from insider trading. Lee, Lemmon, Li, and Sequeira (Reference Lee, Lemmon, Li and Sequeira2014) suggest that insiders in firms that put voluntary restrictions on insider trading continuously take advantage of private information while being more cautious with exploiting negative private information. Dai, Kang, and Lee (Reference Dai, Fu, Kang and Lee2016) also suggest that insiders deliberately use their information advantage to avoid litigation risk.

Since UD laws reduce the risk of derivative lawsuits faced by D&O, we hypothesize that these laws change how insiders trade their firms’ stock. Specifically, UD laws may reduce constraints on informed trading based on private information, or alternatively, reduce concerns about litigation for trades that might appear opportunistic ex post, regardless of the motivation.

As discussed in Section II.B, derivative lawsuits may affect insider sales and purchases differently, as sales are more commonly alleged in DLs than purchases. However, the theoretical prediction is rather ambiguous. While direct shareholder lawsuits are difficult to pursue against informed purchases (which typically precede good news), derivative lawsuits can target both sales and purchases since both can involve breaches of fiduciary duty. Therefore, whether UD laws have stronger effects on sales or purchases is an empirical question, and we examine them separately throughout our analysis.

III. Data, Variables, and Summary Statistics

A. Sample and Data

Our main explanatory variable (After UD Law) is an indicator variable which equals 1 if a firm’s state of incorporation has a UD law in a given year; it equals 0 otherwise. Table A4 presents the timeline of states’ adoption of UD Laws. Following the prior literature, we define After UD Law based on firms’ historical states of incorporation.Footnote 14

Our data on insider trades come from Thomson Reuters Insider Filing data (TIF). Our sample begins in January 1996, when TIF starts reporting these data in earnest and ends in December 2013, 2 years after the last UD law was adopted.Footnote 15 These data include all open market trades reported by corporate insiders (directors, officers, and beneficial owners of 10% or more of the company’s stock) through SEC Forms 3, 4, and 5. We drop beneficial owners’ transactions because they do not have any fiduciary duty to fellow shareholders, so they are not subject to UD laws. We analyze directors’ and officers’ open-market purchases and sales of common stock (CRSP share codes 10 or 11) of firms listed on NYSE, Amex, or Nasdaq and exclude financial and utility firms. Our sample includes transactions without missing data and verified for accuracy by Thomson Reuters and indicated by cleanse codes of R, H, L, C, or Y.Footnote 16

Thomson Reuters Insider Filing (TIF) database does not use separate codes for open-market and private transactions. Following prior studies (e.g., Lakonishok and Lee (Reference Lakonishok and Lee2001), Marin and Olivier (Reference Marin and Olivier2008)), we use two data screens to isolate open-market transactions, albeit imperfectly. Accordingly, we exclude trades where the transaction price falls outside the trading range for the day on CRSP and where more than 20% of the outstanding shares are traded. We also exclude trades involving less than 100 shares and trades in penny stocks, that is, where the share price is less than $2 at the beginning of the calendar year. Following the prior literature on insider trading,Footnote 17 we separately add up the purchases and sales by all insiders on a given day. We analyze insiders’ sales and purchases separately because UD laws can have differential effects on insiders’ incentives to sell and buy, as discussed in Section II.B.Footnote 18

We obtain accounting and stock price data from the Compustat and CRSP databases. The main dependent variables include buy-and-hold abnormal return (BHAR), total number and dollar value of shares traded, and total dollar abnormal profits for each trade day. We calculate the BHAR for 6 months (126 trading days; bhar6m), 3 months (63 trading days; bhar3m), and 1 month (21 trading days; bhar1m) beginning on the day of the insider trade.Footnote 19 We use Carhart’s (Reference Carhart1997) four-factor model to calculate the BHARs. When estimating the model, we exclude returns for 50 days before the insider trading day to avoid a bias from any pretrade price run-ups or run-downs. We calculate posttrade expected returns and BHARs after excluding the estimated alpha to avoid a bias from any systematic price trends during our estimation window of (−250, −50) days.Footnote 20 The BHAR incorporates compounding effects and is well-suited for testing longer term abnormal returns (see Barber and Lyon (Reference Barber and Lyon1997)) while accounting for asset pricing factors. Following prior studies (e.g., Huddart, Ke, and Shi (Reference Huddart, Ke and Shi2007), Kallunki, Nilsson, and Hellström (Reference Kallunki, Nilsson and Hellström2009), and Kallunki et al. (Reference Kallunki, Kallunki, Nilsson and Puhakka2018), we therefore use the BHAR for different holding periods computed from daily returns as our main measure of profitability. As robustness checks, discussed in Section V.B, we also use two alternate measures of insider trading profitability that do not require estimating asset pricing parameters or alpha: i) cumulative total returns (CRETs) and ii) DGTW characteristics-adjusted abnormal returns. Our main conclusions do not change when we use these alternate measures.

We use daily, instead of monthly aggregation, to ensure that we capture relevant stock returns precisely after each trade date, without missing any shorter horizon returns where litigation risk is the highest.Footnote 21 Using monthly aggregation requires collapsing all the trades within a month into a single indicator (i.e., net purchases or net sales), which ignores the frequency and timing of individual trades.Footnote 22 Our approach follows a long line of papers on insider trading that use daily aggregation, many of which also analyze shorter term returns (see, e.g., Bettis et al. (Reference Bettis, Coles and Lemmon2000), Huddart et al. (Reference Huddart, Ke and Shi2007), Khan and Lu (Reference Khan and Lu2013), Gao, Lisic, and Zhang (Reference Gao, Lisic and Zhang2014), Ali and Hirshleifer (Reference Ali and Hirshleifer2017), Kallunki et al. (Reference Kallunki, Kallunki, Nilsson and Puhakka2018), and Wu (Reference Wu2018)).Footnote 23 Nevertheless, we also try a monthly aggregation approach as a robustness check, as discussed in the last paragraph of Section V.B.

For additional analyses, we obtain institutional ownership data from Thomson Reuters’ institutional holdings (13F filings) database. We define higher ownership based on the percentage ownership of the largest 10 institutional investors in a firm. We obtain data on quarterly earnings announcement (QEA) dates and measures of standardized unexpected earnings (SUE) from the Compustat Fundamentals Quarterly and IBES databases. SUE equals (Actual EPS for a quarter – Median of analyst forecasts of EPS) / Stock price. Finally, we obtain data on the disclosure quotient (DQ), which measures the richness of financial disclosure in 10-K filings, from the authors of Chen, Miao, and Shevlin (Reference Chen, Miao and Shevlin2015).

B. Summary Statistics

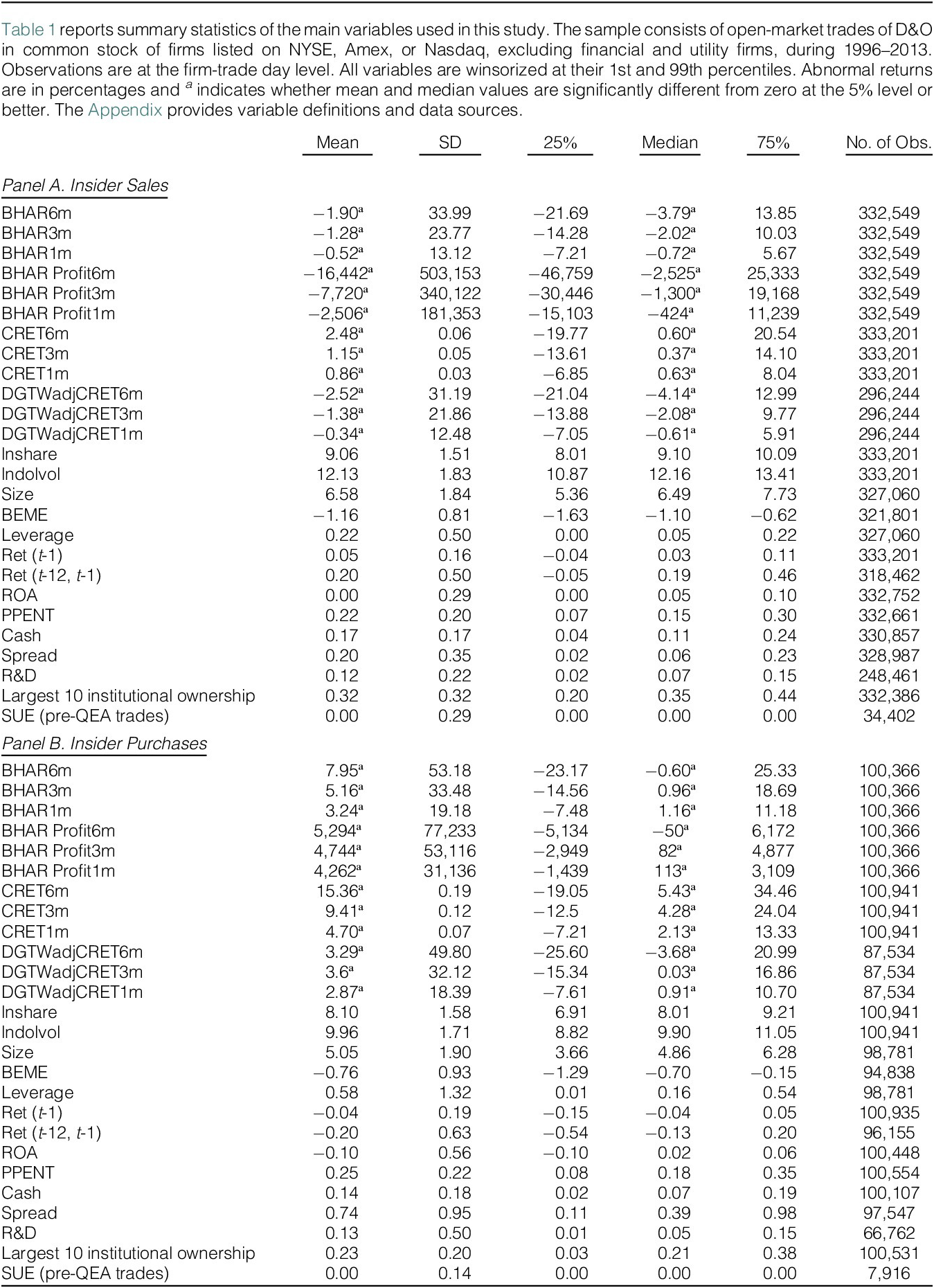

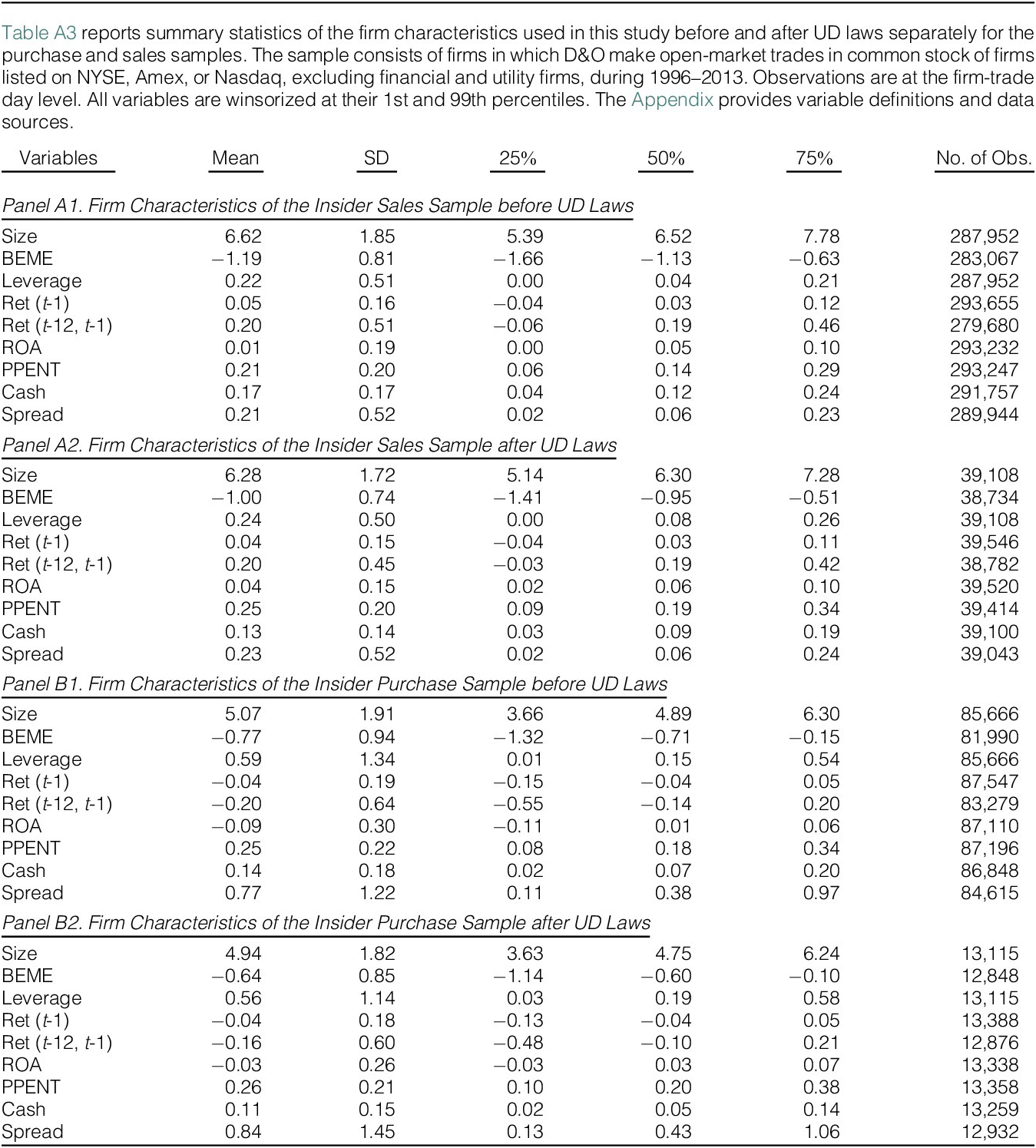

Table 1 reports summary statistics of the main variables of interest separately for our insider purchases and sales samples. We winsorize all continuous variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles to minimize the influence of outliers. Our full sample includes 333,201 firm-sale days and 100,941 firm-purchase days, showing that days with insider sales are about three times as frequent as those with insider purchases, on average. Average BHAR is negative for sales and positive for purchases, consistent with prior findings that, on average, stock prices experience abnormal declines after insiders sell and abnormal increases after they buy stock. Over the 1 month (i.e., 21 trading days), 3 months (63 days), and 6 months (126 days) following the insider trade day, insider sales have average BHAR of −0.52%, −1.28%, and − 1.90%, respectively, while the corresponding returns for insider purchases are 3.24%, 5.16%, and 7.95%.Footnote 24 The average total number of shares traded per day and their dollar values are substantially higher for insider sales than for insider purchases. This pattern is consistent with previous findings that opportunistic insider sales tend to be riskier than purchases. Therefore, a smaller proportion of all sales are likely opportunistic.

TABLE 1 Summary Statistics

The distribution of insiders’ abnormal dollar profits is highly skewed. Estimated dollar profits are expressed in constant 2013 dollars, the last year of our sample, to adjust for inflation. The mean estimated dollar abnormal loss avoidance for assumed holding periods of 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months is about $2500, $7700, and $16,400, respectively, while their median values are much smaller. Mean and median abnormal dollar profits from purchases are generally much smaller. It is important to note that these average profitability measures are across all, not just opportunistic, insider trades, most of which are for liquidity purposes. Hence, small average profitability numbers are not surprising. They are also comparable to the magnitudes found in prior studies on insider trading (see, e.g., Cziraki and Gider (Reference Cziraki and Gider2021)). It is more informative to compare these against the additional profit estimates from our DiD models for trades influenced by litigation risk.

Sellers’ firms are larger and more profitable, and their stock is more liquid (i.e., has a lower bid–ask spread) than buyers’ firms. Sellers’ firms also have lower leverage, slightly lower asset tangibility (PPENT), and higher cash holdings than buyers’ firms.

IV. Empirical Methodology and Main Results

Our empirical methodology follows recent studies that deal with endogeneity issues by exploiting natural experiments, especially multiple exogenous shocks which vary by time and location (e.g., Bertrand and Mullainathan (Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2003), Gormley and Matsa (Reference Gormley and Matsa2011), Karpoff and Wittry (Reference Karpoff and Wittry2018), and Appel (Reference Appel2019)). Specifically, we use the following difference-in-differences (DiD) regression model to examine the effect of UD laws on opportunistic insider trading:

The dependent variable (

![]() ) measures insider trading outcomes, such as abnormal returns or dollar profits earned by insiders in different holding periods.

) measures insider trading outcomes, such as abnormal returns or dollar profits earned by insiders in different holding periods.

![]() indicates firm i, in industry j, state of headquarters k, state of incorporation s, and time t.

indicates firm i, in industry j, state of headquarters k, state of incorporation s, and time t.

![]() is an indicator variable for a firm that is incorporated in a state that has a UD Law in a given year. Notice that After UD Law = UD State × After, where UD State = 1 for a firm incorporated in a state that has a UD law, and 0 otherwise; and After = 1 for firm-years starting with the year of UD law adoption in the firm’s state of incorporation, and 0 otherwise. The regression does not include the main effect variables UD State, which is time-invariant, and After because the former (latter) is subsumed by firm (time) fixed effects. Thus,

is an indicator variable for a firm that is incorporated in a state that has a UD Law in a given year. Notice that After UD Law = UD State × After, where UD State = 1 for a firm incorporated in a state that has a UD law, and 0 otherwise; and After = 1 for firm-years starting with the year of UD law adoption in the firm’s state of incorporation, and 0 otherwise. The regression does not include the main effect variables UD State, which is time-invariant, and After because the former (latter) is subsumed by firm (time) fixed effects. Thus,

![]() is the DiD parameter measuring the treatment effect of UD Law on our outcome variables of interest.

is the DiD parameter measuring the treatment effect of UD Law on our outcome variables of interest.

Following previous studies (e.g., Gormley and Matsa (Reference Gormley and Matsa2016)), we control for time-invariant heterogeneity across firms and time-varying heterogeneity within and across industries and states by including firm by trade month (

![]() ), industry-time (

), industry-time (

![]() ), and headquarters (HQ) state-time (

), and headquarters (HQ) state-time (

![]() ) fixed effects. The industry is defined by 3-digit SIC codes. HQ state-time fixed effects are important controls to subsume varying economic and regulatory conditions across states over time, for example, state-level business cycles that affect local companies’ stock returns significantly (see, e.g., Korniotis and Kumar (Reference Korniotis and Kumar2013)). Similarly, industry-time fixed effects control for time-varying industry effects such as industry momentum in stock returns (see, e.g., Moskowitz and Grinblatt (Reference Moskowitz and Grinblatt1999)). Time is the year and month of trade. To account for firm-level insider trading policies such as blackout periods in certain months (see, e.g., Bettis et al. (Reference Bettis, Coles and Lemmon2000)), and potential seasonality in firm-level stock returns, we include firm-by-trade-month fixed effects.Footnote

25

) fixed effects. The industry is defined by 3-digit SIC codes. HQ state-time fixed effects are important controls to subsume varying economic and regulatory conditions across states over time, for example, state-level business cycles that affect local companies’ stock returns significantly (see, e.g., Korniotis and Kumar (Reference Korniotis and Kumar2013)). Similarly, industry-time fixed effects control for time-varying industry effects such as industry momentum in stock returns (see, e.g., Moskowitz and Grinblatt (Reference Moskowitz and Grinblatt1999)). Time is the year and month of trade. To account for firm-level insider trading policies such as blackout periods in certain months (see, e.g., Bettis et al. (Reference Bettis, Coles and Lemmon2000)), and potential seasonality in firm-level stock returns, we include firm-by-trade-month fixed effects.Footnote

25

We also include a set of continuous control variables, lagged by one-period

![]() that may affect our dependent variables.Footnote

26 Appel (Reference Appel2019) finds that UD laws decrease the quality of corporate governance, lead to lower profitability, and, in some cases, lead to declines in firm values. Our main variables of interest are abnormal stock returns following insider trades. So one concern is that the negative abnormal returns we observe after UD laws are unrelated to insider trades but are a general effect of these laws in depressing stock prices across the board. So we include control variables important for asset pricing (such as size, book-to-market, past returns) and firm-specific variables that Appel (Reference Appel2019) finds to be affected by UD laws (such as profitability). We also control for bid-ask spread (Spread) to account for the possibility that a decrease in litigation threat can lead to changes in a firm’s information environment, thus providing profitable trading opportunities to insiders.Footnote

27

that may affect our dependent variables.Footnote

26 Appel (Reference Appel2019) finds that UD laws decrease the quality of corporate governance, lead to lower profitability, and, in some cases, lead to declines in firm values. Our main variables of interest are abnormal stock returns following insider trades. So one concern is that the negative abnormal returns we observe after UD laws are unrelated to insider trades but are a general effect of these laws in depressing stock prices across the board. So we include control variables important for asset pricing (such as size, book-to-market, past returns) and firm-specific variables that Appel (Reference Appel2019) finds to be affected by UD laws (such as profitability). We also control for bid-ask spread (Spread) to account for the possibility that a decrease in litigation threat can lead to changes in a firm’s information environment, thus providing profitable trading opportunities to insiders.Footnote

27

A. UD Law Adoptions and Profitability of Insider Trading: Baseline Results

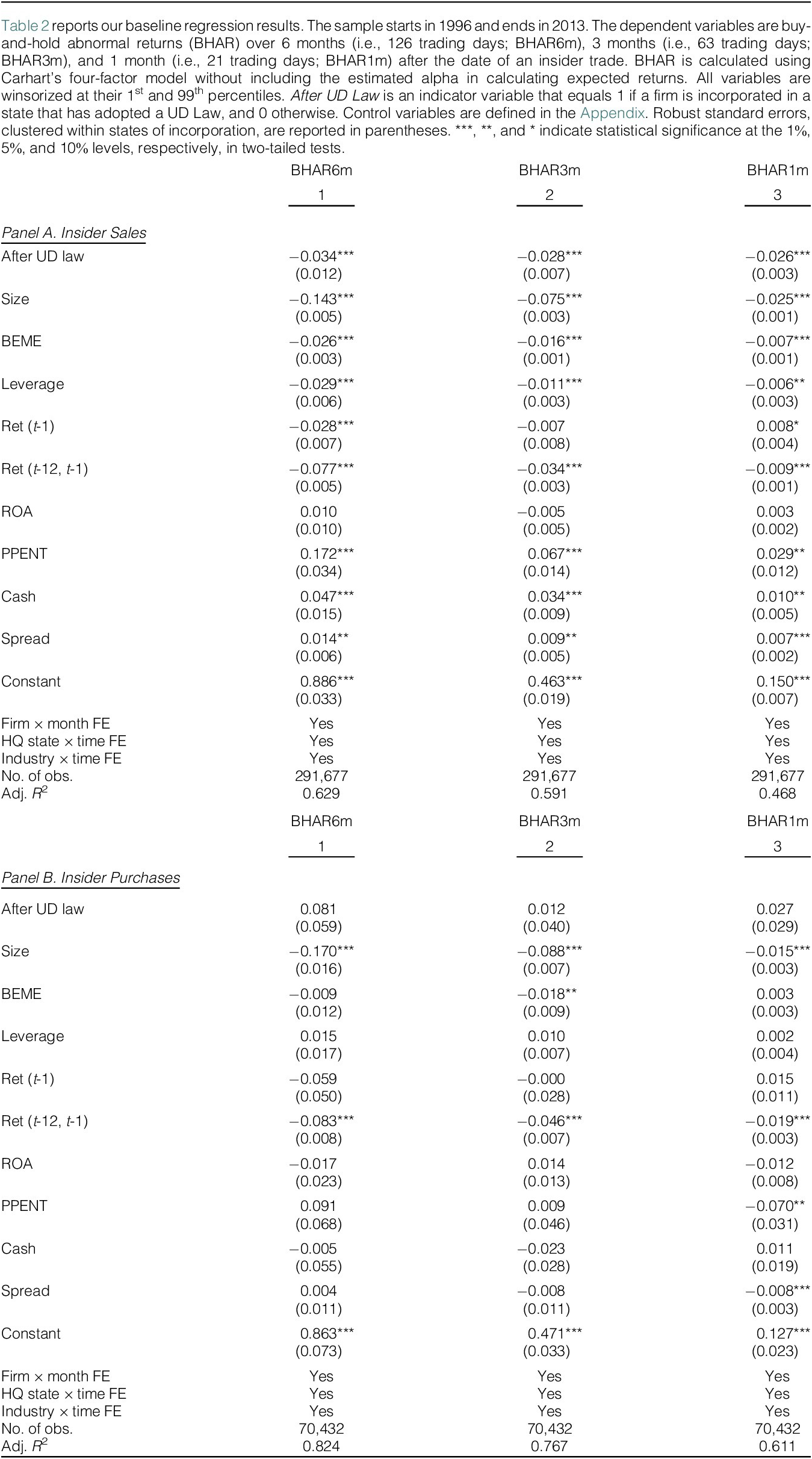

Table 2 summarizes the results from DiD regressions of insider trading profitability measured by buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHAR) for holding periods of 1, 3, and 6 months. In Panel A, After UD Law obtains negative and statistically significant (at 5% or better levels) coefficients in explaining buy-and-hold abnormal returns after an insider sale for all three holding periods. These results suggest that after the passage of UD laws and after controlling for other things, insiders of treatment firms avoid about −2.6%, −2.8%, and −3.4% in abnormal losses (i.e., BHAR) over 1, 3, and 6 months after their open market sale dates, compared to pre-UD law days. These returns are economically large, compared to their unconditional averages (−0.52%, −1.28%, and −1.90%), and support our main hypothesis that insider sales become more profitable after the passage of UD laws, which make it difficult for shareholders to sue insiders for the breach of their fiduciary duties, including opportunistic insider trading. Panel B shows a similar set of results related to the profitability of insider purchases. While the coefficient estimates on After UD Law are positive in predicting BHAR, they are statistically insignificant.

TABLE 2 Universal Demand Laws and Profitability of Insider Trades

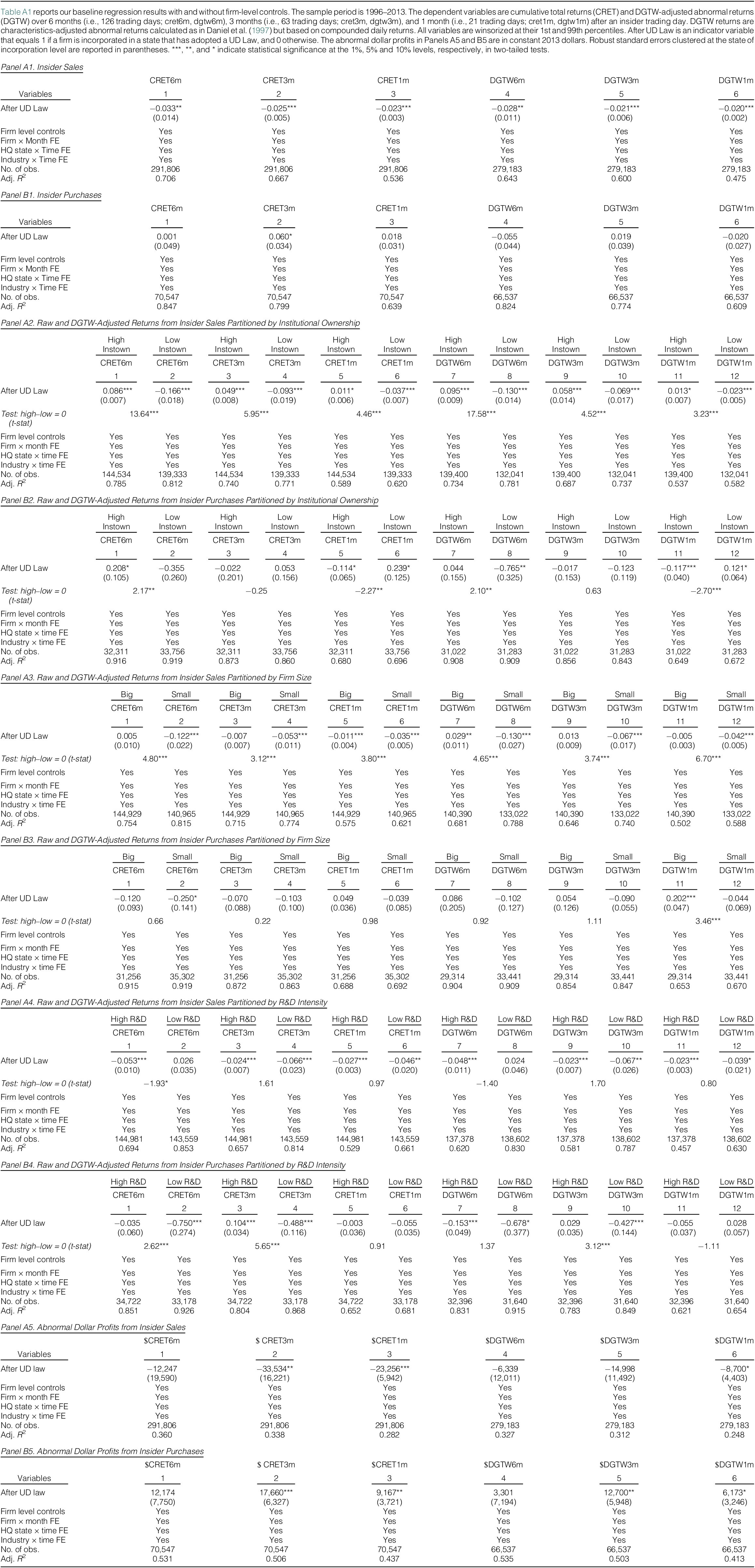

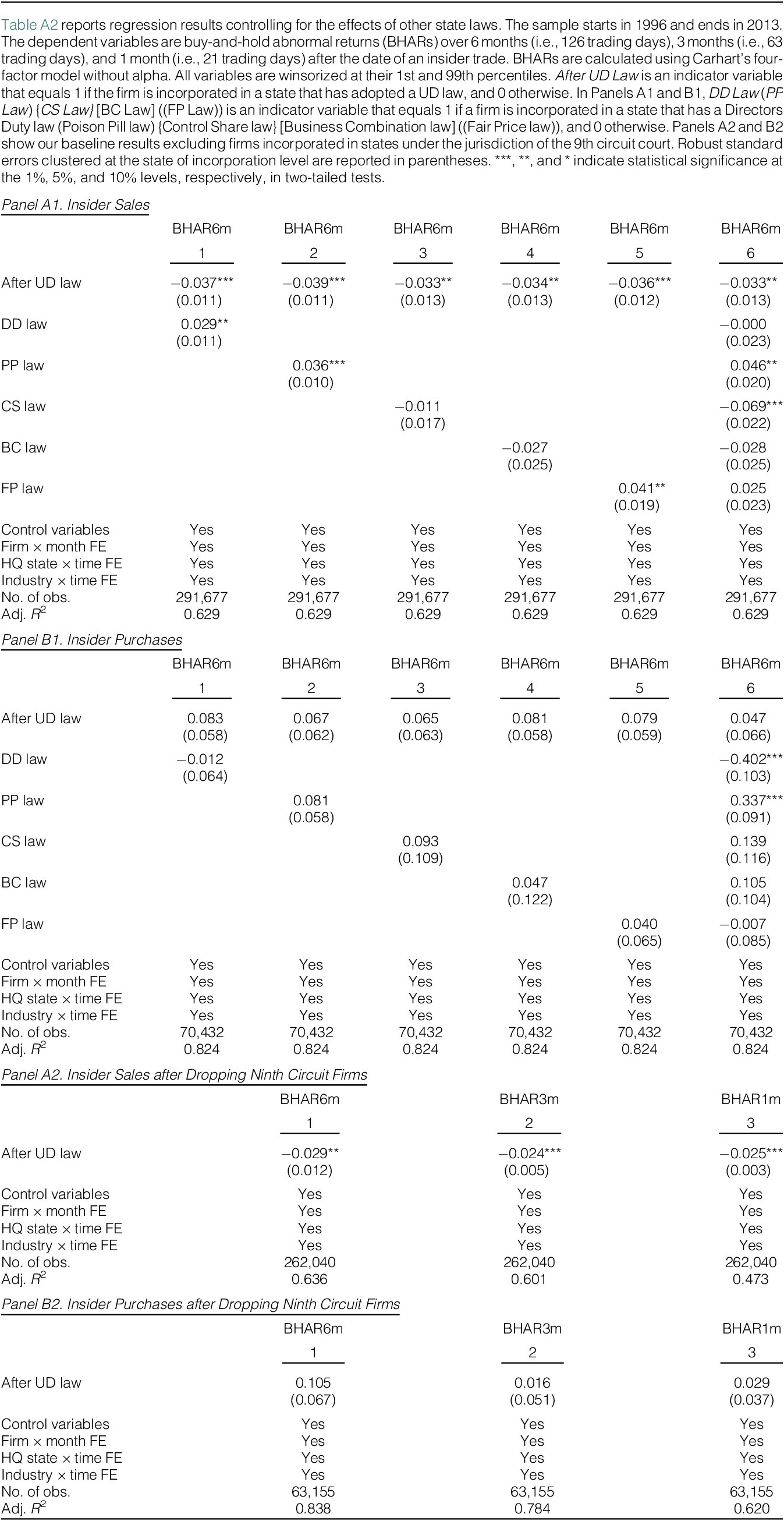

We next check how robust our conclusions are to the specification of estimated returns. While we exclude alpha in calculating our BHAR, one concern is that other asset pricing parameters estimated right before insider trades may be biased for various reasons. To reduce this concern, we exclude the returns for 50 trading days immediately before an insider trade day from the parameter estimation window. To further alleviate this concern, Table A1 shows our baseline results using cumulative total raw returns (CRETs) and DGTW-adjusted returns as dependent variables, neither of which requires estimation of asset pricing parameters.Footnote 28 These results largely mirror our main results in Table 2. In Panel A1, the coefficient of After UD Law for insider sales is negative and statistically significant for all three holding periods for both return measures, suggesting that insiders timed their sales to avoid abnormal losses.Footnote 29 For purchases, the corresponding coefficient is statistically insignificant at the 5% level in Panel B1 in all six regressions.

Overall, we find that After UD Law predicts negative BHAR following insider sales in both economically and statistically significant ways. For purchases, even though the point estimates are often sizable, they are statistically weak or insignificant, and occasionally in the wrong direction. These results are consistent with the notion that UD laws encourage more litigation-prone insider trades, especially sales based on private information.Footnote 30 Moreover, the differential results for purchases and sales provide further assurance that the negative coefficient on After UD Law in predicting BHAR following sales is driven by more informed selling by insiders rather than a general drop in stock prices caused by the adoption of UD laws. A general drop in stock prices would predict no difference in the effect of After UD Law on future returns between the sales and purchase samples.Footnote 31

B. Profitability During the Years Surrounding UD Law Adoptions

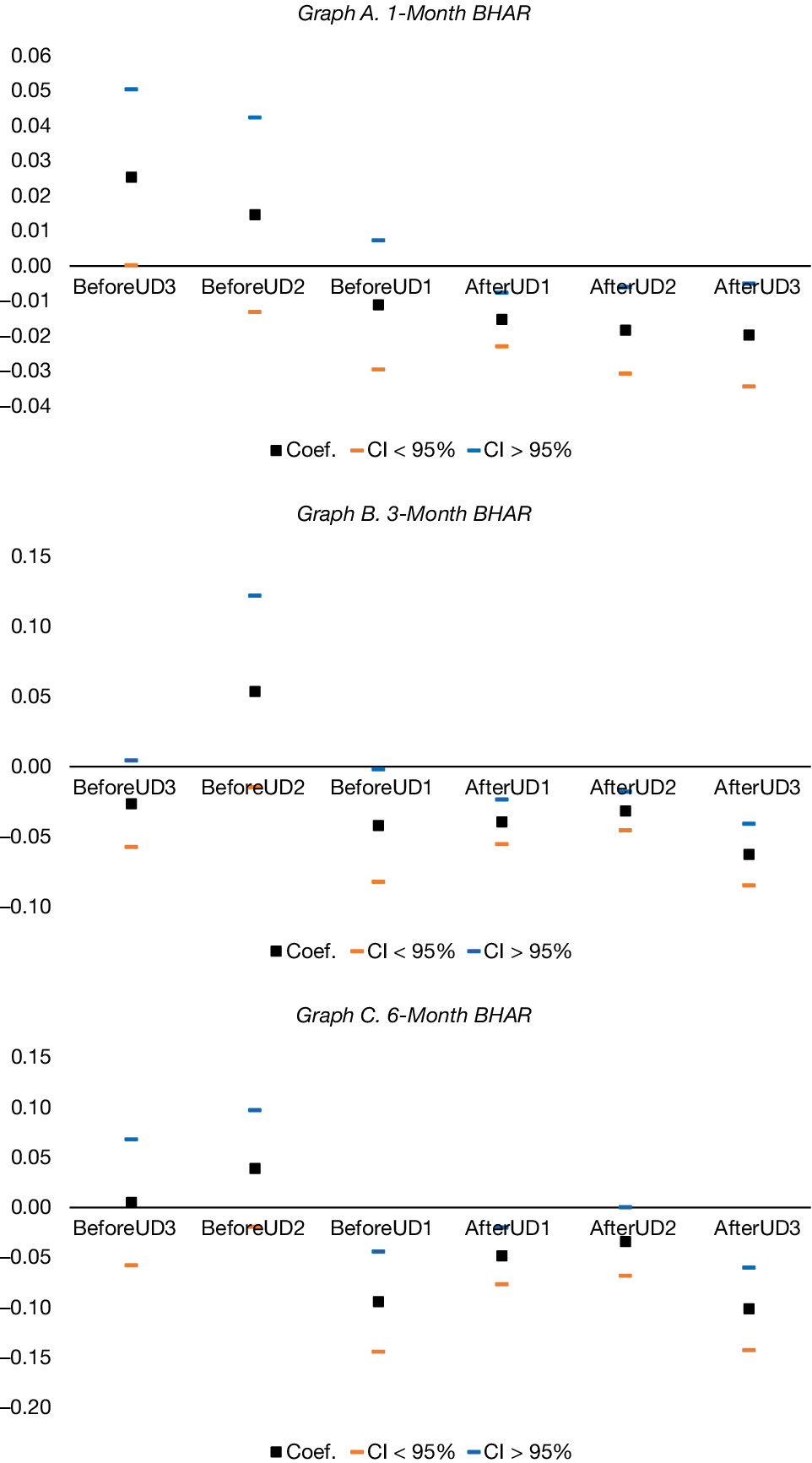

To validate that the passage of UD laws is followed by increased profitability of insider sales, we next examine pretrends. We create indicator variables for each of the 3 years before (BeforeUD3) and 3 years after (AfterUD3) UD law passage in a firm’s incorporation state, with the adoption year labeled AfterUD1. We then re-estimate Table 2 Panel A regressions, replacing AfterUDLaw with these six indicators.

Figure 1 presents the coefficient plots for insider sales over the 6-year window. The solid black squares represent point estimates, and the lines above and below represent 95% confidence bands. Point estimates with bands that surround the horizontal axis (0) are statistically insignificant at the 95% level. The figures show that the average coefficients are more negative post-UD than pre-UD in predicting BHARs for all three holding periods, consistent with Table 2. Graph A shows that the difference in 1-month BHAR for sales between UD and non-UD firms has no pretrend. BHARs are insignificant or positive before the passage, with significant negative effects showing up starting the year of passage. Graphs B and C exhibit a similar pattern for 3-month and 6-month BHARs, which are all negative after year of passage, while most pre-UD years are either insignificant or positive. However, for these holding periods, especially for 6 months, the BHAR turns negative right before the year of passage, likely indicating some anticipation effect, but not a sustained pretrend. Overall, we do not find any concerning violation of parallel trends, affirming the causal impact of UD laws.

FIGURE 1 Dynamics of Buy-and-Hold Abnormal Returns (BHAR) from Insider Sales

Figure 1 shows estimated average excess buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHAR) without alpha for 1-month (Graph A), 3-month (Graph B), and 6-month (Graph C) holding periods following the day of insider sales during the years surrounding the passage of UD laws. The solid black squares indicate the point estimates, and the lines above and below indicate 95% confidence intervals from regressions of BHAR similar to Table 2, where the After UD Law variable is replaced by indicators for the years before and after the passage of UD laws in a firm’s state of incorporation. After UD1 denotes the year of adoption of a UD law.

C. How Do Insiders Exploit Opportunism?

The next sets of tests are aimed at understanding the source of increased profitability of insider trading after UD laws.

1. Trading Volume and Timing

Given a set of profitable trading opportunities, insiders exploit their private information to increase their profits by i) increasing the size of trades before opportunistic but low-risk events, ii) timing the trades more opportunistically and in a riskier manner, or iii) doing both.

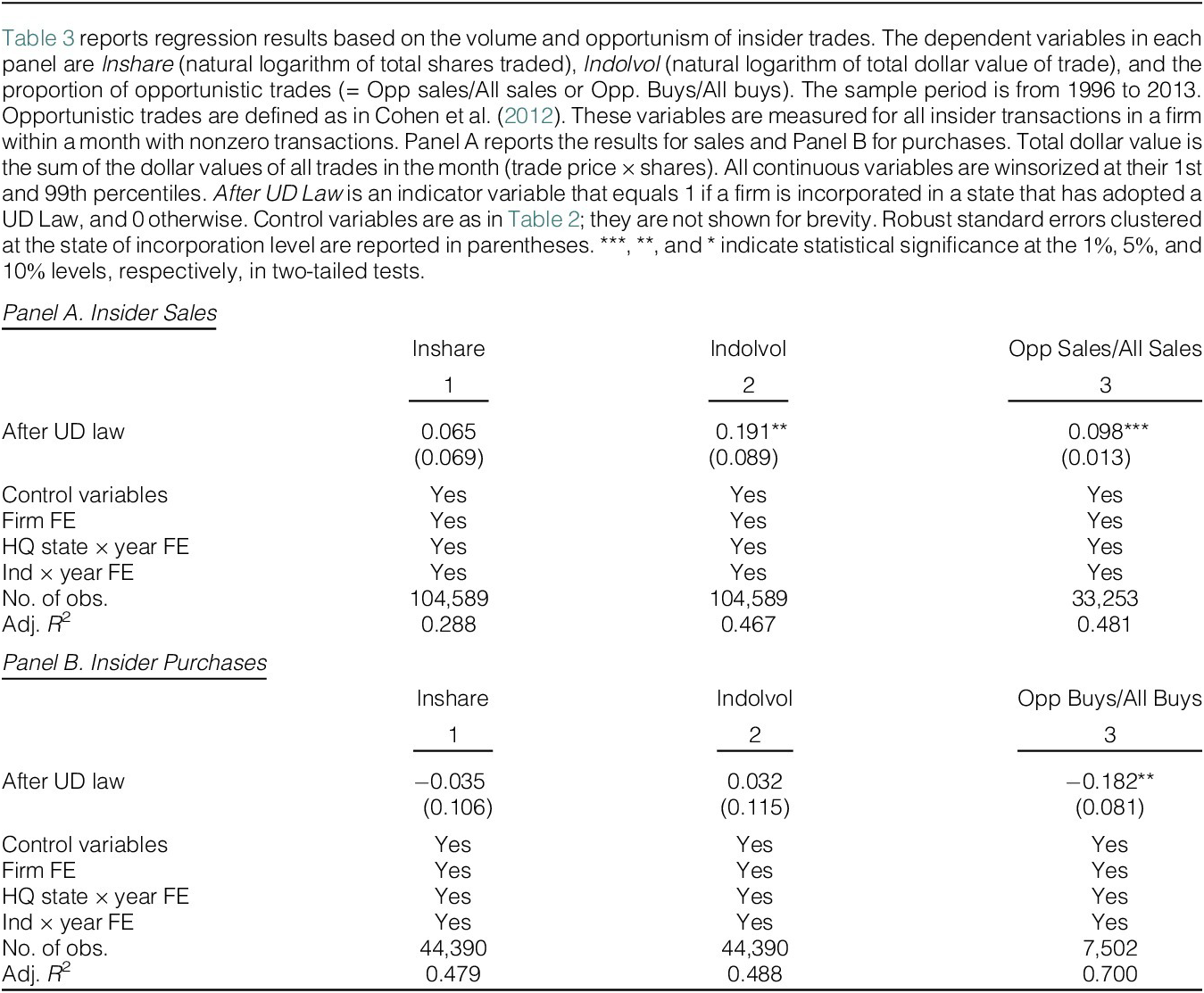

To isolate these channels, we examine the effect of UD Laws on the total number of shares bought or sold by insiders in a given month and the total dollar value of such trades (trade price × shares). Table 3 reports the results. The dependent variables in Panel A (for sales) and Panel B (for purchases) are lnshare (natural logarithm of total shares traded) and lndolvol (natural logarithm of the total dollar value of trades) of all insider transactions in a firm in each month that has at least one insider trade. Column 1 of Panel A shows that the average number of shares sold by insiders in a given month (lnshare) does not change significantly after the adoption of a UD Law. However, the DiD estimate in column 2 shows that the total dollar values of insider sales (lndolvol) in these months increase significantly by about 21% (= e0.191 – 1) in treated firms compared to control firms. Thus, after the adoption of UD laws, insiders do not increase the number of shares sold. They appear to time their sales more opportunistically by using their private information that stock prices are inflated and a price decline is likely.Footnote 32 We do not find a similar pattern for purchases. In columns 1 and 2 of Panel B, insiders in treated firms change neither the number of shares nor the dollar value purchased in a significant way compared to control firms.

TABLE 3 Trading Volume and Opportunism

We next identify opportunistic and routine trades following Cohen et al.’s (Reference Cohen, Malloy and Pomorski2012) methodology. Column 3 in each panel shows estimates of the regressions of the proportion of the number of opportunistic insider (i.e., D&O) trades to all such trades. In our partitionable sales sample using Cohen et al.’s (Reference Cohen, Malloy and Pomorski2012) approach, the proportion of opportunistic sales in a month increases by 0.098 in treatment firms after UD laws in Panel A. This increase is both statistically and economically significant.Footnote 33 On the other hand, in Panel B, in the partitionable purchase sample, the ratio of opportunistic purchases decreases.Footnote 34 Overall, these results suggest that while there is not a significant increase in the level of selling by insiders in treatment firms after the adoption of UD laws, their sales become more opportunistic, and therefore, more profitable.

2. Volume and Profitability of Pre-QEA Trades

Our analysis so far suggests that after the adoption of UD laws, insiders avoid losses by timing their sales more opportunistically. Insiders become more willing to push the boundaries of the law in their trading, presumably because of the reduced risk of shareholder lawsuits. To further investigate this possibility, we examine an especially high-risk form of opportunistic insider trading, namely, insider trades before quarterly earnings announcements (pre-QEA). This analysis is motivated by Ali and Hirshleifer (Reference Ali and Hirshleifer2017), who find that despite tight regulations, voluntary corporate policies on insider trading and high risks, some insiders continue to trade pre-QEA.Footnote 35 They define the pre-QEA period as the 21 trading day period ending three trading days before a QEA date and find that pre-QEA trades tend to be among the most profitable insider trades.

Ali and Hirshleifer (Reference Ali and Hirshleifer2017) suggest that the high profitability of such trades serves as a robust way to identify the most opportunistic insider trades, as an alternative to Cohen et al.’s (Reference Cohen, Malloy and Pomorski2012) approach. This is because, regardless of whether a firm has an explicit policy prohibiting pre-QEA insider trading and whether it enforces it strictly, such trading looks opportunistic to investors. While investors cannot observe whether a firm has such a policy, how lenient it is in granting exceptions to it, and whether and how strictly it enforces it, they can observe reported insider transactions, including pre-QEA trades. While pre-QEA trades are somewhat rare, they are still numerous. For example, in Panel A of Table 4, there are 38,774 (= 9862 + 28,912) days with pre-QEA insider sales in our sample, about 11.6% of all 333,201 days with insider sales in Table 1. However, our interest is not in analyzing the frequency of pre-QEA trades, but rather in determining whether they are opportunistic and profitable, a task we turn to next.

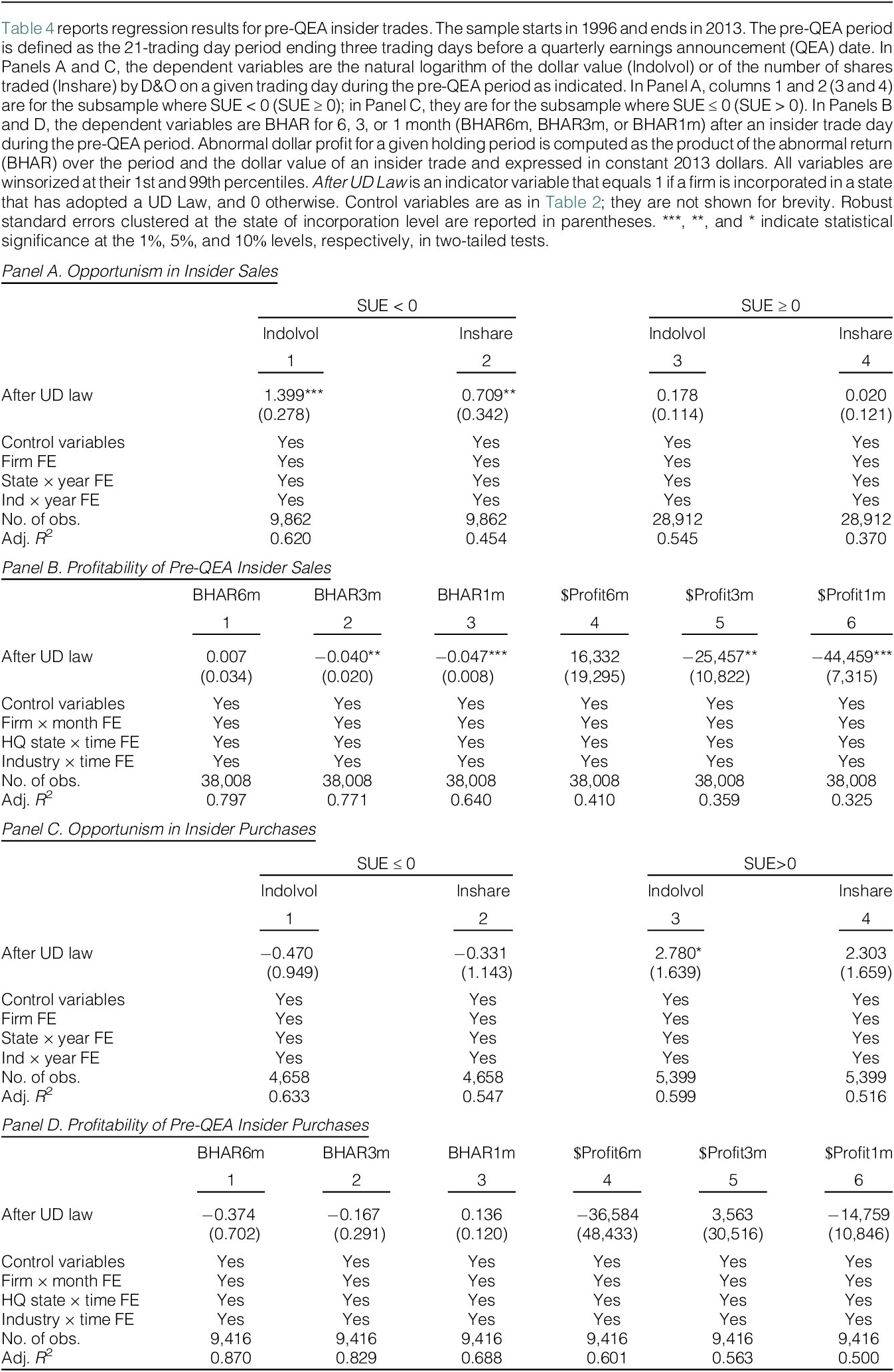

TABLE 4 Profitability of Insider Trades before Quarterly Earnings Announcements

We examine two issues here: i) whether the volume of pre-QEA trades depends more on the direction of earnings surprises after UD laws and ii) whether pre-QEA insider trades become more profitable after UD Laws. Table 4 shows the results. The unit of analysis here is a trade-day for the subsample of pre-QEA trades. To examine the first issue, we aggregate the number of shares and dollar value of trades on each pre-QEA trading day and estimate separate regressions based on whether the subsequent SUE is negative or nonnegative. In columns 1 and 2 of Panel A, both the number and dollar value of pre-QEA sales preceding negative SUEs increase significantly after UD law adoption. In contrast, in columns 3 and 4, UD laws have no effect on sales volume when SUE is positive or zero, that is, when profitable selling opportunities are low. This asymmetric volume response provides further evidence that insiders opportunistically time their pre-QEA sales ahead of negative earnings news once the threat of shareholder litigation recedes. The lack of volume change when SUE is nonnegative indicates that insiders specifically ramp up sales in anticipation of negative earnings surprises, rather than increasing their overall pre-QEA sales. The strategic increase in the volume of sales before bad news aligns with insiders taking greater advantage of UD laws to profit from their inside information. Importantly, the fact that these accounting-based SUE results mirror our return-based profitability findings helps further alleviate any remaining concerns about the measurement of our abnormal returns.

Finally, we examine profitability in the subsample of pre-QEA trades, as we do in our baseline models. Panel B shows the results for the profitability of insider sales. We find that pre-QEA sales become significantly more profitable after UD law adoption over the 1- and 3-month periods following the trade. The coefficient of After UD Law is much larger for these periods than in the full sample in Table 2. However, these trades do not become more profitable after UD law adoption over the 6-month period, consistent with our hypothesis that UD laws impact shorter term, hence previously more litigation prone, profits more. This point is particularly important for pre-QEA trades, where the profit is likely to be realized at or soon after the QEA (see Ali and Hirshleifer (Reference Ali and Hirshleifer2017)). Given the definition of the pre-QEA period, 1-month profits after the trade date are likely the most pertinent here. In constant 2013 dollars (= BHAR × $Trade in constant dollars), the increase in abnormal loss avoided by insiders of treated firms from pre-QEA trades after UD law adoption exceeds that for control firms by about $44,000 and $25,000 for 1- and 3-month holding periods, respectively. Both of them are statistically significant. The additional dollar profit for the 1-month holding period is much larger in this subsample than in the full sample (Table 6). For insider purchases, a similar set of tests shown in Panels C and D yields mostly statistically insignificant and inconsistent results.

Taken together, elevated opportunistic trading volumes and increased profitability around QEAs paint a consistent picture: UD laws enable insiders to more aggressively exploit their information advantage through pre-QEA trading, mainly sales, where multiple metrics point to increased opportunistic behavior during lucrative, but otherwise legally perilous, windows.

D. Cross-Sectional Tests of Risks and Opportunities

We now dig deeper into the role of opportunism as the underlying channel for the increased profitability of insider sales that we observe after the adoption of UD laws. We focus on the role of governance, firm size, and trading opportunities as discussed in the following.

1. Institutional Blockholdings and Firm Size

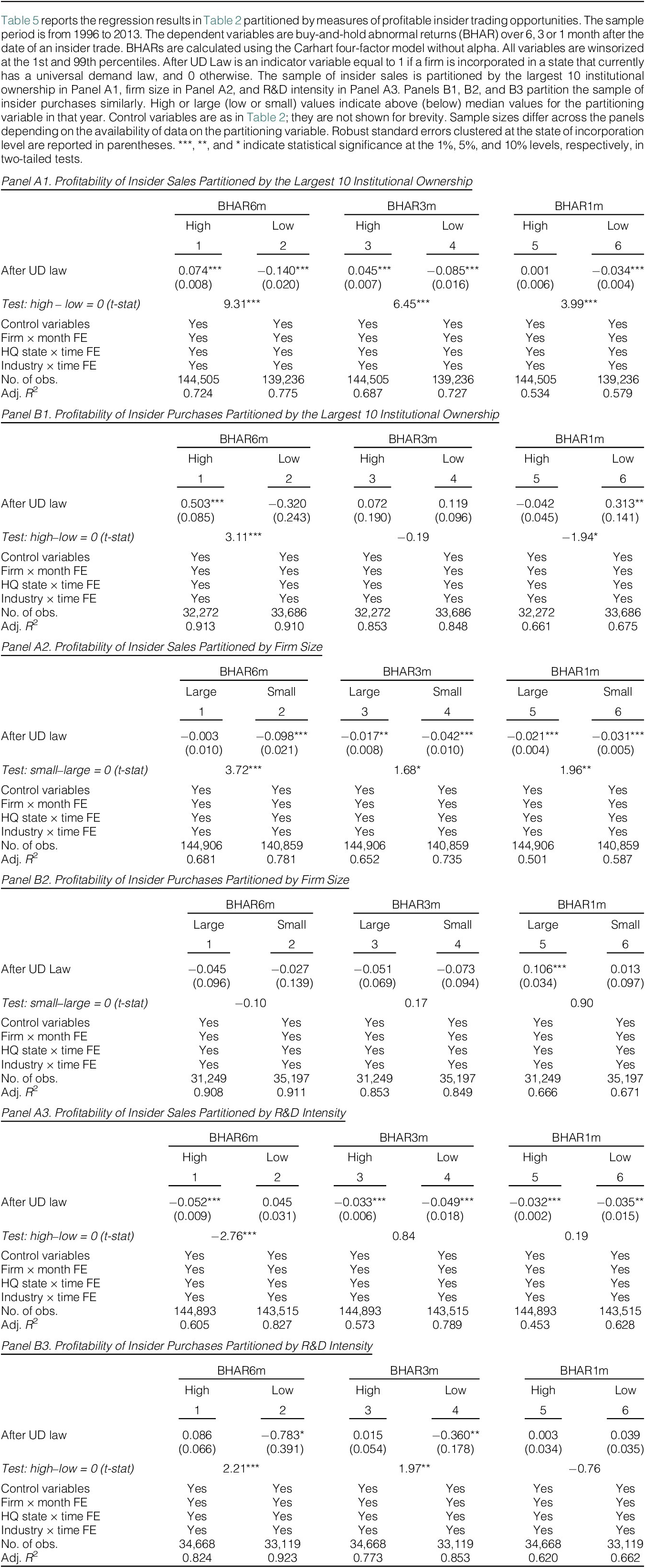

Davis (Reference Davis2008) argues that DLs are less important for highly visible large corporations, which are subject to many other governance mechanisms that can substitute for the effects of DLs. One such mechanism is company rules on insider trading, which are more common in large firms (see, e.g., Bettis et al. (Reference Bettis, Coles and Lemmon2000)). This argument implies that the effect of UD laws on insider trading profitability should be greater for firms with fewer alternative governance mechanisms in place and for smaller firms. We first consider institutional blockholdings as an external governance mechanism.Footnote 36 We calculate the total percentage equity ownership of a firm’s 10 largest 13F institutional owners of each sample firm. We then split the sample annually by the median of such blockholder ownership. Second, we partition the sample into large and small firms annually based on median market capitalization. Table 5 reports the results. To save space, we only tabulate the coefficient estimate and test statistics of the After UD Law variable.

TABLE 5 Cross-Sectional Tests for Insider Trading Opportunities

Panel A1 of Table 5 partitions the insider sales sample by blockholder ownership. We find that after UD law adoption, insider sales in treatment firms with below median blockholder ownership exhibit much larger increases in profitability across all horizons compared to firms with higher blockholder ownership. All the differences are highly statistically significant. Table 5, Panel A2 shows that after UD laws, insider sales turn more profitable (as measured by BHAR) both for smaller and larger firms over two horizons. This effect is significantly higher among smaller firms over all three horizons.

Panels B1 and B2 show results for insider purchases with similar sample partitions. Although purchase results are significant in some subsamples, they do not show a consistent pattern expected from differences in size and governance. Overall, the cross-sectional tests support our predictions and suggest that governance substitutes like firm visibility and monitoring by blockholders mitigate the incentives for opportunistic sales created by UD laws.

2. Trading Opportunities

Insiders’ opportunities to trade on private information should be greater among firms with higher information asymmetry. To test this conjecture, we follow Aboody and Lev (Reference Aboody and Lev2000), who find that outside investors face greater information asymmetry with insiders in more R&D intensive firms, which provides greater opportunity for profitable insider trading. We define high (low) R&D based on above- (below-) yearly median of a firm’s R&D intensity.

Table 5, Panel A3 shows that the profitability of insider sales in terms of BHAR after UD law increases for both high and low R&D intensive firms. The coefficients of After UD Law are statistically different and economically higher between high and low R&D firms over the 6-month holding period.

In Panel B3, we also see some moderating effect of information asymmetry on the profitability of insider purchases in the expected directions: higher positive returns in higher R&D firms after UD Laws for BHAR6m and BHAR3m. However, similar to the full sample results, these results are noisier than those in the sales sample.

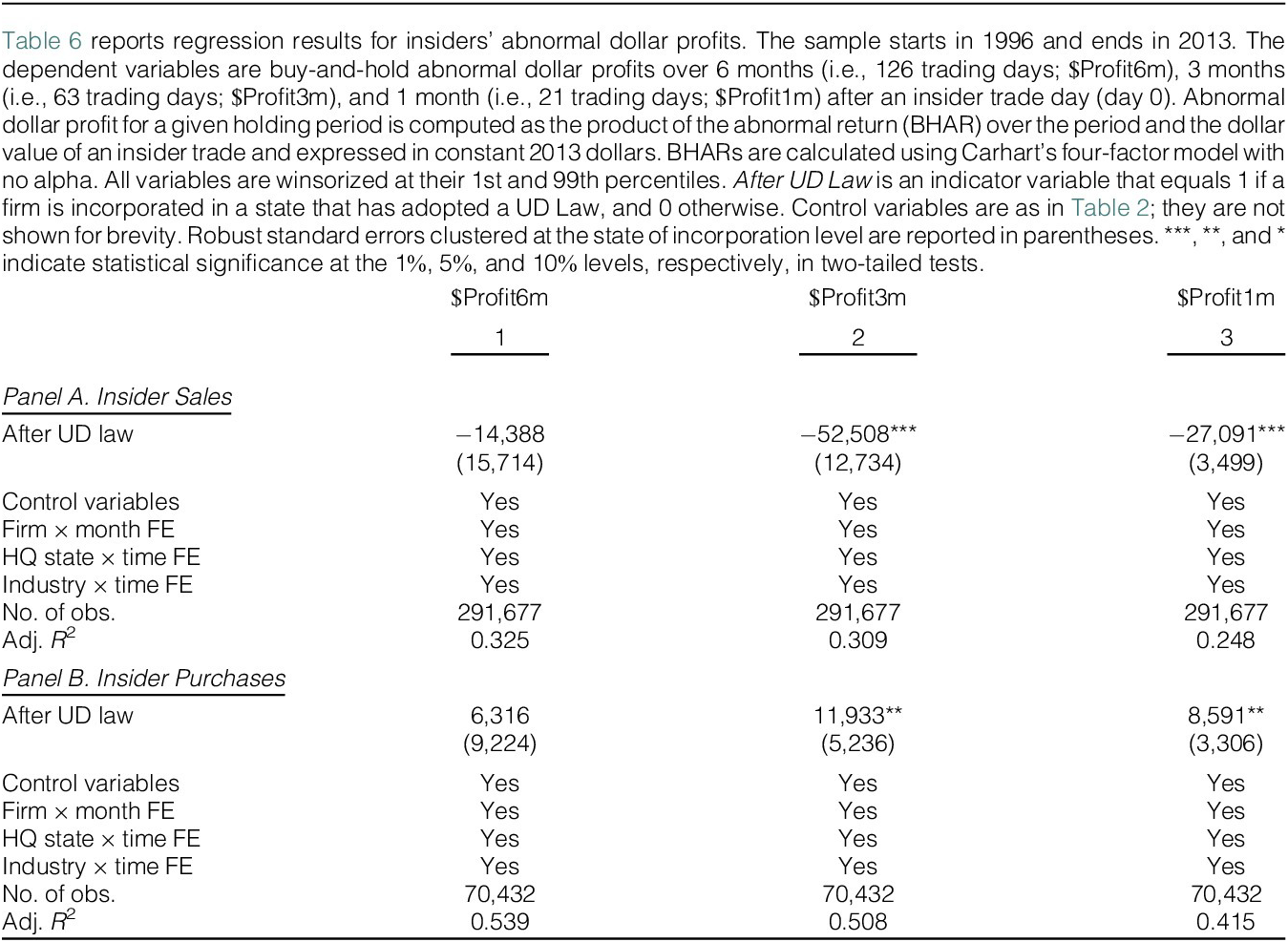

E. Insiders’ Abnormal Dollar Profits

We next estimate the impact of UD laws on the dollar value of insiders’ profits as an alternate way to assess economic significance. These measures incorporate both trade size and posttrade stock returns to estimate the potential dollar profits for each trade day. We calculate buy-and-hold abnormal dollar profits for each trade day over the next 1-, 3-, and 6-month horizons (denoted profit1m, profit3m, and profit6m and computed over 21, 63, and 126 trading days, respectively) by multiplying the dollar value of a trade by the BHAR over the holding period. They are expressed in constant inflation-adjusted 2013 dollars.

Table 6 reports the results. Columns 1–3 of Panel A show that after UD laws, each insider sale avoids abnormal losses of approximately $27,000, $52,500, and $14,400 per trade over the subsequent 1, 3, and 6 months, respectively. The 6-month coefficient is smaller and statistically insignificant, in contrast to the significant BHAR6m result in Table 2. This difference arises because BHAR regressions equally weigh each trade, while dollar profits weigh them by the dollar value of the trade. The findings suggest that UD laws encourage some additional opportunistic longer-horizon trades with significant 6-month BHARs, but the dollar volumes of such trades increase less. UD laws predominantly affect sales volumes that are profitable over the shorter 1- to 3-month horizons, which are presumably riskier than those that are profitable over the 6-month period.

TABLE 6 Insiders’ Abnormal Dollar Profits

Panel B of Table 6 shows that insiders’ purchases after UD laws yield abnormal dollar profits of around $8,600, $11,900, and $6,300 over 1-, 3-, and 6-month holding periods. The first two are statistically significant. While smaller in magnitude than the sales results, these gains significantly exceed the unconditional mean abnormal dollar profits in Table 1, Panel B. However, earlier in Table 2, Panel B, we find positive but statistically insignificant effects of UD laws on BHARs for purchases. Again, this divergence arises because BHARs equally weigh each trade, while dollar profits weigh them by trade value. The dollar profit results suggest that insiders time some larger purchases opportunistically after UD laws, profiting more on those trades. But equal-weighted BHARs suggest that such opportunistic purchases do not increase significantly in frequency for the full sample post-UD laws. These differing purchase results align with our earlier evidence that UD laws lead to more opportunistic timing of insider purchases in certain subsamples. These results suggest that UD laws enable some opportunism for purchases, but with weaker effects compared to the pervasive opportunism they induce on insider sales.

F. Size of Insider Trading Profits and the Role of DLs in Curbing Insider Trading

As we conclude our key results and before moving to robustness checks, we address an important question about the interpretation of our findings, particularly regarding the economic magnitude of the effects and what they imply about the role of derivative lawsuits in constraining insider trading. In our full sample (Table 6, Panel A), we find that after UD laws, an average insider sale in treated firms experiences an increase in abnormal dollar profit (i.e., a reduction in underperformance relative to the benchmark) of approximately $27,000 and $52,500 over 1- and 3-month holding periods, respectively, compared to control firms. These amounts appear modest relative to the compensation and wealth of highly paid executives and raise the question whether they are large enough to lead D&O to engage in trades that are legally dubious despite UD laws.

The answer depends on one’s priors about the marginal role that derivative lawsuits play in constraining insider trading behavior. If one views derivative lawsuits as a primary deterrent to opportunistic trading, these modest dollar amounts might suggest limited practical importance. However, if one views derivative lawsuits as a supplementary enforcement mechanism, which seems more appropriate given that they rarely target insider trading as a primary allegation and federal enforcement remains in place, then even these modest effects demonstrate that private enforcement extends deterrence beyond what public enforcement alone achieves.

Here are some other contexts for interpreting our magnitudes. First, the effects we find are economically meaningful relative to what the prior literature finds for typical insider trades. Cziraki and Gider (Reference Cziraki and Gider2021), who focus on analyzing dollar profits from insider trading, report abnormal profits of approximately $4000 and $10,000 over 1- and 3-month windows for average insider trades.Footnote 37 Bhattacharya and Marshall (Reference Bhattacharya and Marshall2012) note that even some high-profile SEC prosecutions involve only modest gains. For example, Martha Stewart’s ImClone trade avoided only $45,673 in loss, representing just 1.7% of her annual pay. Relative to the unconditional mean abnormal dollar profits of $2500 and $7700 in our sample (Table 1), the incremental effects we document are economically meaningful.

Second, our sample necessarily includes many nonopportunistic liquidity trades, which dilutes estimates of the effects on purely opportunistic transactions. When we focus on trades that appear more opportunistic, such as sales before quarterly earnings announcements, we find larger effects. One-month abnormal profits from pre-QEA sales increase by approximately $44,000 on average after UD law adoption,Footnote 38 suggesting more substantial effects for the subset of trades where litigation risk was previously the highest.

Third, the nature of derivative lawsuits themselves provides important context. DLs are not primarily aimed at insider trading; rather, they target a broader range of alleged harms to the company, with insider trading typically serving as a secondary allegation or supporting evidence.Footnote 39 As discussed in the introduction and Section II.A, this feature makes UD laws particularly valuable for identification purposes, since their adoption is rarely motivated by concerns about insider trading, satisfying the exclusion restriction. However, this also implies that UD laws should not be expected to produce large effects on insider trading behavior. While UD laws likely reduce constraints on some insider trading, the most egregious illegal trading remains subject to federal enforcement. Additionally, derivative lawsuits typically seek governance reforms rather than large monetary penalties, limiting their expected deterrent effect.

Regardless of how one weighs these considerations in assessing economic magnitude, our study makes an important contribution by providing clean causal evidence that private enforcement through shareholder litigation has a deterrent effect on insider trading and complements public enforcement.

G. Blockholders as a Placebo Group

Our main analysis excludes trades by 10% blockholders, who are also required to report their trades to the SEC. But unlike D&O, blockholders do not owe any fiduciary duty to other shareholders and therefore are not normally subject to DLs. We next consider whether this distinction allows us to use blockholders as a potential placebo group because UD laws should not affect their trading patterns. But this prediction is not obvious. First, many firms lack a 10% blockholder, and where they exist, many of them are likely passive institutional investors, who do not trade (especially sell) as frequently. This issue is apparent from our untabulated finding that the number of firm-trade days in our sample where blockholders sell (buy) is about 10% (one-third) of those for D&O. Second, even though blockholders are not affected by the decreased risk of DLs, they can mimic trades by D&O, which become more informative after the adoption of UD laws.

Nevertheless, we estimate regressions similar to our baseline (Table 2) regressions separately for the samples of blockholders’ sales and purchases. The results, untabulated for brevity, show little resemblance with our main results on D&O transactions. For non-D&O transactions, After UD Law does not obtain signs and significance in the predicted direction in any specification. These results support our litigation risk hypothesis and increase the hurdle for other interpretations of our main results, such as an overall change in stock returns or information asymmetry. UD laws mainly affect opportunistic sales by D&O, who are subject to DLs.

V. Alternative Explanations and Robustness Checks

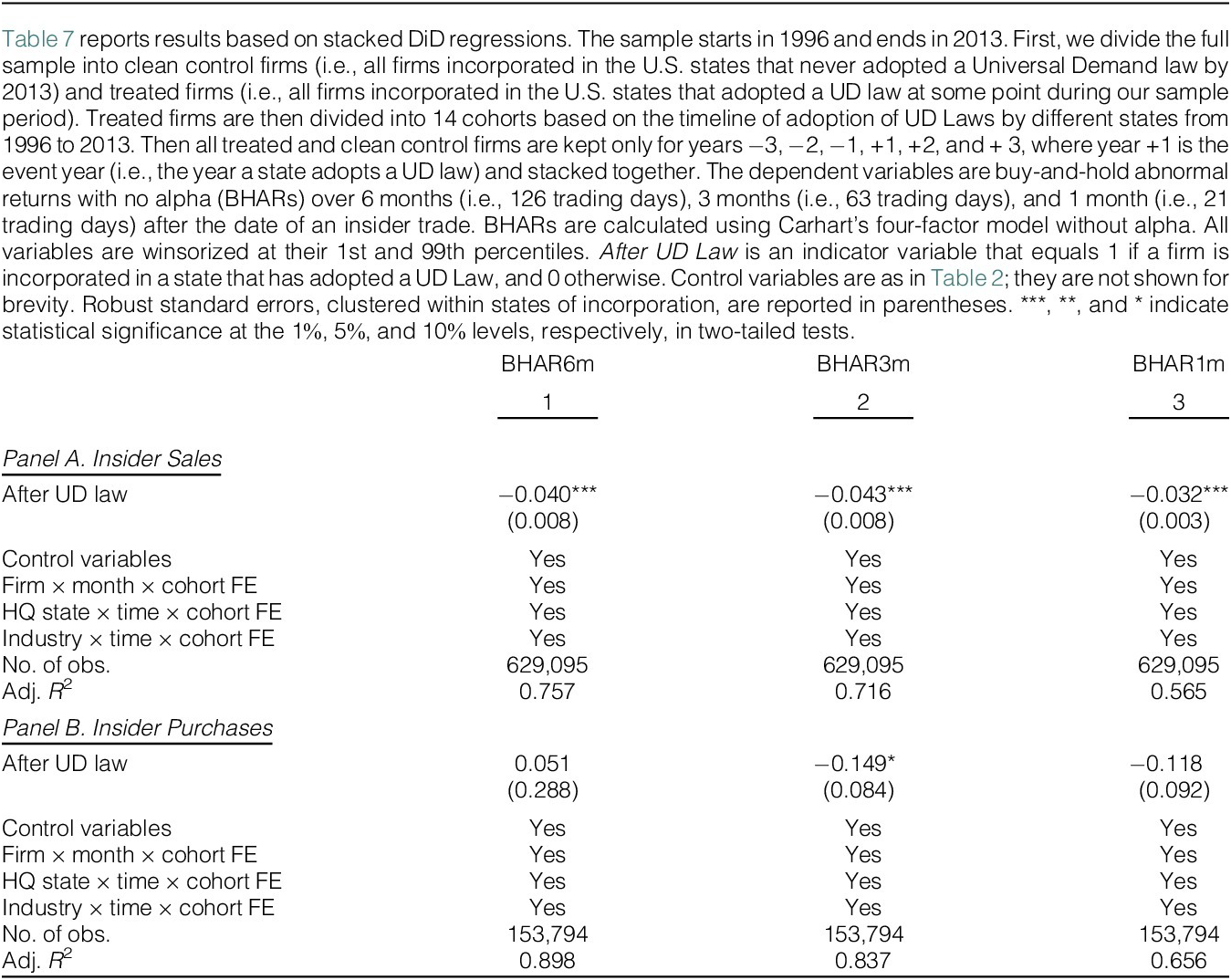

A. Stacked DiD Regressions

We conduct a rich set of tests to check the robustness of our main results. One concern with our Table 2 results is that, as Table A4 shows, UD laws were adopted over a long period of time, potentially creating a bias if treatment effects vary over time. To alleviate this concern, we re-estimate our baseline model using a cohort-level stacked DiD approach following previous studies (e.g., Cengiz, Dube, Lindner, and Zipperer (Reference Cengiz, Dube, Lindner and Zipperer2019), Deshpande and Li (Reference Deshpande and Li2019), and Li, Monroe, and Coulton (Reference Li, Monroe and Coulton2023)). Accordingly, we define firms headquartered in states that do not have UD laws until the end of our sample period as the control group. For each treated state, we construct a balanced panel with 3 years of pretreatment data (i.e., years −3, −2, and −1) and 3 years of posttreatment data (i.e., years +1, +2, and + 3, where +1 is the adoption year). We merge the corresponding years for the clean (i.e., never-treated) control group and stack the data into one data set. We then re-estimate our baseline regression of insider trading profitability on the posttreatment (After UD Law) indicator in this stacked sample. We include fixed effects for Firm × Month × Cohort, State × Time × Cohort, and Industry × Time × Cohort, following Li et al. (Reference Li, Monroe and Coulton2023), who analyze a similar setting. In Panel A of Table 7, After UD Law obtains negative and significant coefficients in explaining returns from insider sales. These results are consistent with and stronger than our baseline results in Panel A of Table 2. The results for the purchase sample in Panel B of Table 7 are statistically insignificant at the 5% level, similar to our baseline results in Panel B of Table 2. These results offer additional assurance that our baseline results are not significantly affected by an unbalanced panel or time-varying treatment effects.Footnote 40

TABLE 7 Robustness Test with Stacked DiD: Baseline Results

To further address the issue of pre- versus posttreatment observations in our staggered DiD setting, we reanalyze our main results in Table 2 by excluding “always adopter” states from our sample, that is, states that adopted UD laws before 1997. This ensures the availability of both pre- and posttreatment observations for all treated states. In this restricted sample, the After UD Law variable yields negative coefficients of −0.032, −0.036, and −0.37, which are close to our baseline estimates in Panel A of Table 2 and statistically significant at the 1% level.

We also conducted an experiment to mimic a balanced panel, albeit imperfectly, in the staggered adoption setting by focusing on a narrower time window around the passage of UD laws. Specifically, we define PostUD3 as the period 1–3 years after the law’s adoption and PreUD3 as the period 1–3 years before adoption for treated states. Using these indicators, we re-estimate our baseline regressions in Table 2 to compare how treated states performed after adoption versus before adoption, relative to the control states. For insider sales, the coefficient on PostUD3 is more negative than PreUD3 across all return horizons, indicating that, during this time window, insider sales in treated states experienced more negative abnormal returns after the passage of UD laws compared to before, relative to control states. These differences are statistically significant at the 1% level for the 1-month and 3-month return horizons.

B. Alternate Return Measures

Next, we consider whether our main results hold when we use alternative methods to calculate abnormal returns on insider trades. We consider two other approaches: raw returns and DGTW’s characteristic-adjusted abnormal returns, neither of which requires estimation of parameters of asset pricing models. We show these results in Panels A1 and B1 of Table A1. Consistent with our main results, After UD Law obtains negative coefficients in predicting abnormal returns from insider sales. The sales results are statistically significant for all time horizons.

We also conduct cross-sectional tests of risks and opportunities using raw returns and DGTW characteristic-adjusted returns as alternate measures of abnormal returns. These results are presented in the remaining panels of Table A1. In Panel A2, the profitability of insider sales after UD law adoption increases more in treatment firms with lower institutional blockholding compared to those with higher institutional blockholding, using both raw returns and DGTW-adjusted returns. Panel B2 reveals a similar pattern for insider purchases, with significantly higher positive returns over 1- and 3-month holding periods among firms with lower (vs. higher) institutional blockholding after UD laws. In Panel A3, the increase in the profitability of insider sales after adoption of UD law is larger for smaller firms; the difference is consistently significant for DGTW returns. Panels A4 and B4 examine the effect of UD laws on insider trading profitability for firms with different R&D intensity. The increase in the profitability of both insider sales and purchases after adoption of UD law is generally larger in more R&D-intensive firms, although the differences are mostly statistically insignificant.