In April 1632, Michel-Ange de Nantes received the news that he was to be sent to the Levant. From Brittany, he was to travel to Marseille and then onwards to Aleppo, where he would join the few Capuchin fathers who had already been living there for several years. Stopping in Paris, Michel-Ange de Nantes encountered rumours circulating about other Capuchins who had gone before him: it was said that some had failed to learn the local languages and had no choice but to return to France, while others in Rome had claimed that Capuchin missionaries had been unable to live in ‘good conscience’ abroad. Even the Propaganda Fide, the recently established office of the papacy tasked with responsibility for missions, had written to Père Joseph de Paris, director of the order, about news it had received that some Capuchins had allegedly converted to Islam. As he travelled, he continued to encounter other, different reports about the mission abroad, which some in Marseille described as being well-regarded by local communities in Aleppo, both Christian and Muslim. In this way, Michel-Ange de Nantes spent a hot, uncertain summer in Marseille, waiting three months for a ship, and finally departing on 8 September 1632, which happened to be the feast of the birth of the Virgin Mary.

If he felt trepidation during his journey, his concerns seem to have disappeared by the time of his arrival in Aleppo. In his first letter from Aleppo – written to Raphael de Nantes, the provincial, or head, of the order in Brittany – he described how impressed he was by what the Capuchins had already accomplished there. The rumours he had heard of the hardships faced by missionaries was wrong. Instead, he described the close, personal relations he had quickly developed himself with both local Christians and Muslims. He spent some three years studying Arabic and Armenian before deciding, in 1636, to leave Aleppo in hopes of establishing a Capuchin presence further east in Baghdad and Mosul. From 1637 to 1641, Michel-Ange focused his energies among the local communities in Baghdad, even becoming superior of the Capuchin household there. This too was a period of great success: in 1638, he wrote that he had received more alms from Ottoman subjects than he could ever obtain in France. During the day, he conversed with local notables and higher clergy, joined the laity in their daily devotions, and sometimes even offered medical advice to Christian and Muslim families. At night, he wrote letters that would make their way to France, inspiring and energizing other Capuchins, even Père Joseph, the head of the order, who passed his time reading stories of the conquests of Godefroy de Bouillon, leader of the First Crusade and the first ruler of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. It is unclear how much of his life Michel-Ange de Nantes spent in this way, before he travelled back at some point to Brittany, where he died in Auray in 1664.

Almost all that we can know about Michel-Ange de Nantes relies on information taken from twenty-six letters he wrote over a period of some nine years spent in the Ottoman empire.Footnote 1 That these letters survive at all is down to some measure of luck. It was at some point after 1641 that Michel-Ange de Nantes’s letters were recovered, copied and assembled into a single manuscript as part of a larger collection of letters written by Capuchins in the Ottoman empire. Little is known about the identity of the compiler, but what is clear is that the manuscript itself was sent, probably in 1648, to Marcellinus de Pise, a Capuchin of the province of Lyon, who had been collecting materials to use for his continuation of a history of the order that had been started earlier in the century. While Marcellinus’s history was published in Lyon only in 1675, the letter book itself has somehow survived and is preserved today at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.Footnote 2 Comprising a total of 116 letters written by twenty-six Capuchins over a period stretching from 1626 to 1641, the collection offers an idiosyncratic window into the earliest Capuchin missions to the Ottoman empire. Some missionaries are much better represented than others. In contrast to the twenty-six letters written by Michel-Ange de Nantes, for example, we learn almost nothing from the collection about one of his companions, Charles-François d’Angers, whose presence can only be gleaned from occasional references to him made by Michel-Ange de Nantes. For others, such as Agathange de Vendôme, we do not possess a single letter in the collection, despite its being clear from other sources that Agathange de Vendôme had studied Arabic and conversed with locals for nearly a decade as he travelled from Jerusalem to Aleppo to Cairo, before his death in Ethiopia in 1638.Footnote 3 Despite the echoes of his movements in the archives, Agathange’s voice is absolutely silent in this letter book. This is a reminder of how little can ever be known about a category of individuals who spent much of their lives far from home, in oral conversations with the local societies in which they lived, and who rarely, if ever, published any works in print. In search of past lives spanning great distances, historians must depend on the haphazard survival of letters and other scraps of paper, all of them witnesses to the desires of the dead for connection to distant family, friends and others in the worlds they left behind.

I. Introduction: Margins and Peripheries

Did these missionaries think of themselves as living ‘on the margins’ or ‘at the peripheries’? This is an important question in as much as the everyday lives of missionaries play a central role in debates about the nature, global or otherwise, of early modern Catholicism. These debates have tended to revolve around rival ways of conceptualizing ‘the making of Roman Catholicism as this planet’s first world religion’: Europe and the world, converters and the converted, or in the apt formulation by Simon Ditchfield, the ‘papacy and the peoples’.Footnote 4 Whereas an earlier generation of scholarship took for granted a centre-periphery model in which Catholicism spread outwards from Rome to Africa, Asia and the Americas, recent approaches have sought to decentre our focus away from assumptions about the centrality of Rome in the making of global Catholicism. This work of ‘decentering’ has transformed our understanding of early modern Catholicism in important ways. Some scholars have emphasized the importance of new relationships that developed directly between different regions in this period and without any reference to Rome.Footnote 5 Others have challenged Eurocentric ideas of Christianity, emphasizing instead the dynamism of the Christian world beyond Latin Christendom, especially in the Christian East.Footnote 6 In the most recent and transformative example of this approach, Simon Ditchfield has emphasized ‘reciprocity’ and the creativity that underlay the ways in which European forms of Catholicism ‘were owned and adapted to local needs by the indigenous peoples of Asia, America, Africa, and parts of Europe itself’.Footnote 7 In place of traditional ideas of a ‘global Catholicism’ with its notional headquarters in Rome, therefore, scholars have proposed the importance of frameworks such as ‘local religion’, ‘polycentric’ Christianity, and even ‘composite Catholicism’ as ways of rethinking the place of geography in our understanding of early modern Catholicism.Footnote 8

These approaches have coincided with a second set of transformations in the ways in which scholars have studied the history of the missions themselves. Where missionary orders, and their archives, were traditionally sifted for documentary sources about the societies they encountered, a more recent wave of scholarship has made missionaries themselves the subject of critical study. These approaches offer alternative ways of imagining the experience of missionaries. Christian Windler, for example, has shown how the work of missionaries in Persia was subject to competition between multiple Catholic actors, whether papal, national, or the orders themselves.Footnote 9 Similarly, Megan Armstong’s study of the ‘reinvention of Catholicism’ in the Holy Land demonstrates how competition between different religious orders defies any simplistic ways of thinking about ‘Catholic mission’ as a unified, coherent set of aspirations.Footnote 10 In another recent approach to missions in Asia, one group of historians has focused on ‘patterns of localization’ as a way of recovering a sense of the place of missionaries in a defined set of contexts, for example in courts, cities, the countryside, and in their own households.Footnote 11 Taken together, these approaches have emphasized the importance of situating the analysis of missionaries firmly within the context of the local societies in which they were rooted, in some cases disconnected entirely from Rome.

Underlying both these fields – ‘global Catholicism’ and ‘early modern missions’ – are a set of assumptions rooted in how historians think about issues of distance in the early modern world. On the one hand, these works have shown how the circulation of information created a sense of simultaneity between communities dispersed around the world.Footnote 12 They have shown us how Europeans conflated geography, sometimes seeing in the missions to the Americas models for how to approach the ‘other Indies’ at home.Footnote 13 They have also challenged contemporary ideas about the expansion of Catholicism, emphasizing the spread of Catholicism as a granular process that took place at the level of individuals.Footnote 14 All of this is a testament to the fruitful ways in which scholars of early modern Catholicism have increasingly adapted the language of global history, especially the way global historians have engaged critically with the study of space, mobility and circulation.Footnote 15 Yet, as Jeremy Adelman has argued, even global historians still have a good deal of work to do when it comes to thinking about the problem of distance in a critical and reflexive way.Footnote 16

For missionaries far from home, being ‘on the margins’ was as much a state of mind as a lived reality. To this end, this article applies the insights of global history to help us rethink how global Catholicism was lived and experienced by missionaries, particularly in relation to this volume’s focus on margins and peripheries. It does so through the close study of a collection of letters written by Capuchins during the order’s earliest presence in the Ottoman empire. The focus on this book of letters allows us to recover a sense of the different ways in which a single missionary order reflected on its position in local, Ottoman and global contexts. In what follows, I emphasize the significance of these reflections as windows into both individual and collective forms of belonging as they intersected within a single community: the Capuchins of the province of Brittany. Members of a global religious order, but also individuals resident in local Ottoman societies, their reflections on distance do not map easily onto the frameworks generally used to understand early modern Catholicism, whether centre-periphery or local-global. Instead, this article argues that an emphasis on geography distracts us from more important aspects of the missionary experience, namely the specificity with which Catholic orders regarded particular societies and places in the early modern world. Within the global theatre of Catholic missions, the Ottoman empire offered a unique stage.

In emphasizing the specificity of the Capuchin experience in the Ottoman empire, I build here on a generation of scholarship that has transformed our understanding of the ways in which the work of Catholic missions in the Christian East was distinct from that of missions in Africa, Asia and the Americas. This was implicit in the earliest handbooks written for the instruction of missionaries such as that of the Discalced Carmelite Thomas á Jesu (1564–1627), which contained a special chapter for missionaries travelling to the East that circulated widely among the Capuchins.Footnote 17 The distinctiveness of the Ottoman empire was also present in the basic, but vexing, question about how to ‘convert’ Eastern Christians, a problem that would generate much debate in later decades.Footnote 18 At the same time, it has long been clear that generic categories like ‘Eastern Christianity’ are deeply problematic: in 2003, Bernard Heyberger was already cautioning against the dangers of treating Eastern Christian confessions as fixed and stable, emphasizing instead the dynamic and connected histories of different communities of Christians across the Ottoman empire.Footnote 19 All of this should serve as a warning against too easily incorporating the Ottoman empire into debates about ‘global Catholic missions’, at least not without giving sufficient attention to the ways in which contemporaries regarded it as being distinct in space and time from other societies where Catholic missionaries travelled in this period.

What follows in this article, therefore, is the study of a group of Capuchins from Brittany who were dispersed across a constellation of places, all of them different from one another even as they shared the status of being part of the political world of the Ottoman empire. Rather than see these early Capuchin missions as operating ‘on the margins’ – whether by virtue of their presence in the world of Eastern Christianity, or by virtue of their distance from Rome or their own countries of origin – this article starts from a different perspective, that is, by situating these individuals at the heart of the Ottoman communities in which they established themselves. Neither ‘local’ nor ‘global’, the early Capuchin missionaries thought about their own position in the Ottoman empire in three main ways. First, I show how the circulation of letters between Capuchins facilitated their participation in a global order organized around the Capuchin province of Brittany. Next, I argue that, within this order, the Capuchins developed a distinct sense of the specificity of their presence within the Ottoman empire. This specificity was not defined in a geographic sense, or as a function of distance, but rather by the unique circumstances of religious diversity they faced in the Ottoman empire and, in particular, in terms of their aspirations to achieve proximity to Ottoman Christian communities. Finally, in the last section of this article, I explore how the specificity of their work in the Ottoman empire played itself out in everyday life as the Capuchins sought to become closer to the societies in which they lived. Seeing global Catholicism through the eyes of someone like Michel-Ange de Nantes, we can understand how the everyday work of ‘global Catholicism’ could enable a missionary in the Ottoman empire to feel as though they were at the centre of Christianity despite the great distance – thousands of kilometres, between Brittany and Aleppo – that separated them from home.

II. Brittany in Aleppo: A Global Capuchin Order

The main materials for this study survive today in a single manuscript located at the Bibliothèque nationale de France under the shelfmark NAF 10220.Footnote 20 There is no indication of who copied and compiled these letters into a single manuscript. A note scribbled onto the first folio of the manuscript indicates only that the ‘book of letters and relations’ had been sent from the ‘superior of the province of Brittany to R. P. Marcellin’ for the purpose of the ‘composition of his annals of the mission’.Footnote 21 Other annotations in the manuscript include reference to the dispatch of specific copies of letters that had been ‘sent to R. P. Marcellin de Pise in 1648’, all of which suggests that the letter book had come into the possession of Marcellinus de Pise, a Capuchin of the province of Lyon, at some point in the 1640s.Footnote 22 Little more can be known about the larger context surrounding Marcellinus’s writing of a history of the order. Given the focus of the manuscript on letters written by Capuchins from Brittany – almost all the letters are addressed to Raphael de Nantes, Capuchin provincial of Brittany in the 1630s – it may be that his history was intended to celebrate the contributions of the province to the order’s success in the Ottoman empire. At any rate, it appears that Marcellinus de Pise’s history was only published decades after the manuscript itself had been returned to Brittany.Footnote 23

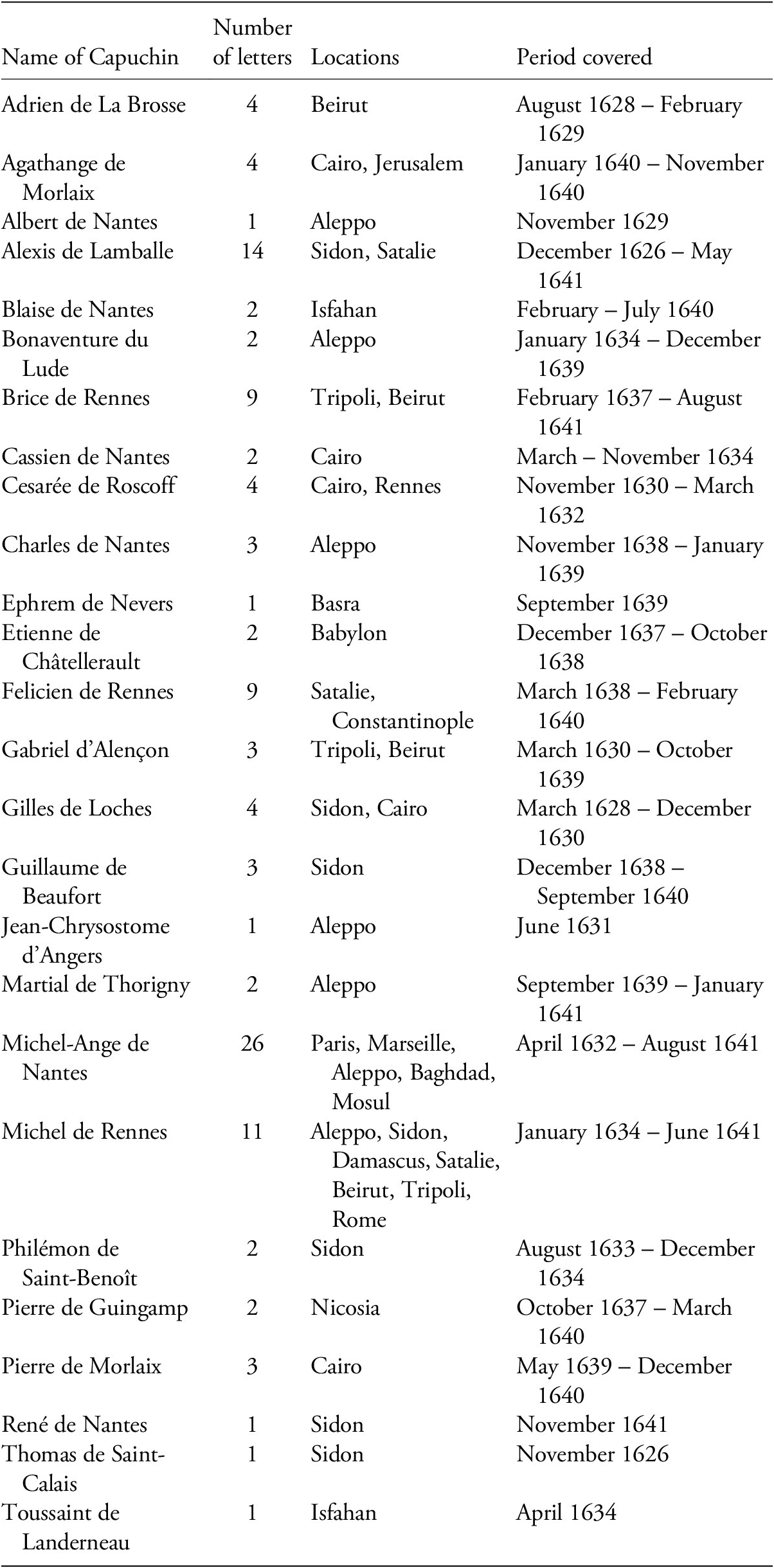

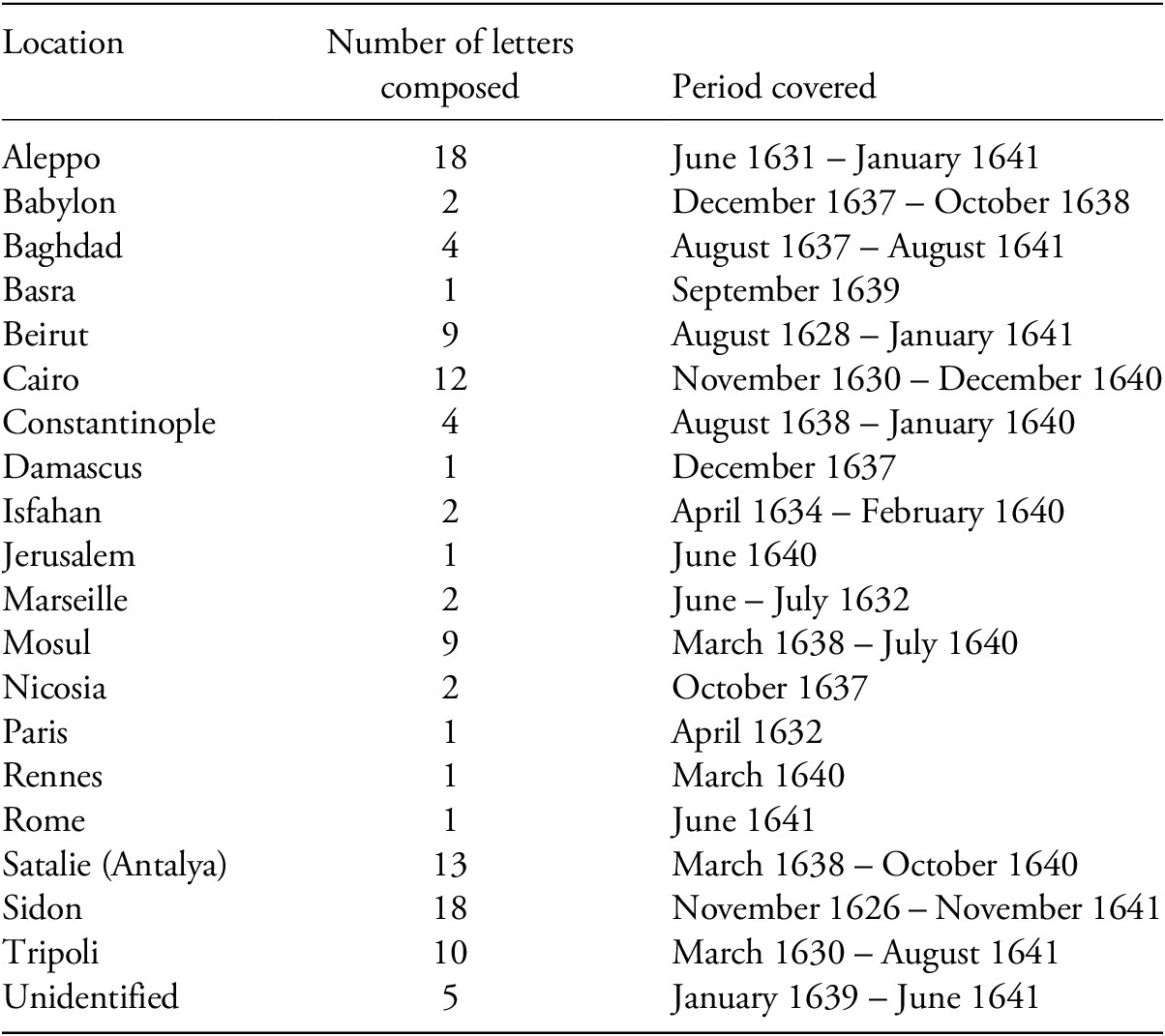

Representing a foundational moment in the Capuchin mission to the Ottoman empire, the manuscript includes some 116 letters by twenty-six individual missionaries written from fifteen different locations in the Ottoman empire including, in order of frequency: Aleppo, Sidon, Satalie (Antalya), Cairo, Tripoli, Beirut, Mosul, Constantinople, and Baghdad. Table 1 details the names of all the missionaries represented in the collection as well as the number of surviving letters and general dates covered by the letters. Table 2 contains information of all the locations of the letters. In addition, the manuscript contains copies of several important documents related to the Capuchin missions in the East, for example, early charters and instructions related to the founding of the mission in the Levant in 1625 under the leadership of Père Joseph (François Leclerc du Tremblay, 1577–1638).Footnote 24 Moreover, a ‘table des lettres et relations’ at the beginning of the manuscript flags twenty-four letters as being of particular importance (‘les plus notables’); however, further study would be needed to establish whether there is any relationship between these letters – they were written by different authors and from different locations – or why the compiler thought they deserved to be singled out in this way in the table of contents. Whilst all the letters appear to be written in the same hand, there are also a number of marginal annotations that are written in Arabic, which correspond to Arabic terms transcribed in the letters; and in one case there is also a copy of an entire letter in Arabic.Footnote 25 All of this suggests that whoever compiled the manuscript had access to the original letters as sent from the Ottoman empire, and they must have possessed at least rudimentary abilities in writing Arabic or had help from someone who did.

Table 1. The Capuchin Letters in NAF 10220

Table 2. The Composition of Letters in NAF 10220

While the presence of Catholic missions in the Middle East dated back to the medieval Franciscan presence in the Holy Land, the beginning of the seventeenth century witnessed the arrival of new orders in the wake of the establishment of the Sacred Congregation of the Propaganda Fide in 1622. In addition to the reinvigoration of Catholicism in the Holy Land, the seventeenth century also witnessed increased competition between different religious orders over who would have jurisdiction over specific locations in the Ottoman empire.Footnote 26 In the early 1620s, a handful of Jesuits could already be found in Constantinople, Syria and Mediterranean islands including Cyprus, whilst Discalced Carmelites and Augustinians had been dispatched mainly to Isfahan and other locations in Safavid Iran.Footnote 27 In the Arab provinces of the Ottoman empire, the Capuchins became more present from the early seventeenth century, especially in the period that followed the mission of the Friar Minor Tommaso Obicini di Novara, who served as a papal emissary to a synod with the Church of the East held in Diyarbakir in 1616.Footnote 28

Seen within this larger context, the letters collected in NAF 10220 provide only a small window into a much longer history of Catholic missions in the Ottoman empire. They are not witnesses to the earliest presence of Capuchins.Footnote 29 Nor should they be seen as offering a complete account even of the short period during which the letters were composed, since they were assembled, and therefore curated, by the anonymous compiler in Brittany. Moreover, the letters provide a distorting impression if we try to read them as signs of any ‘permanent’ Capuchin presence in a given location. With the exception of a couple of Capuchin households established in key centres like Aleppo and Sidon, the presence of a missionary in any given location was not necessarily sustained over a long period of time. This was the case for example with Mosul: the town witnessed the arrival of the first Capuchins in 1638, but they had left by 1641, after which the order ceased to maintain a permanent presence in the city again until the 1660s.Footnote 30 The impression of ubiquity painted by the list of locations in Table 2 is also misleading in that the actual number of missionaries at any one place in time rarely exceeded a couple of individuals; sometimes there may have been more if we take into account the possibility of missionaries travelling through a location. Individual Capuchins were themselves sometimes ignorant of the presence nearby of other members of their order, and in some cases they seem unaware even of previous Capuchin missions in the places where they were.Footnote 31 Unlike modern historians who can build a complete picture of the missions retrospectively through the gathering of archival sources, individual missionaries could be entirely in the dark when it came to their position relative to other missionaries in both space and time. This is a reminder that episodes of exchange between Catholicism and Eastern Christianity were never sequential and cumulative in the tidy way often imagined by twentieth-century church historians.

NAF 10220 quickly complicates any ideas of the triumphant spread of global Catholic missions. Instead, we find a tentative process through which a very small number of individuals – dispersed across a vast, changing set of locations – managed to establish permanent missionary households in only a few locations. This may explain the acute sense of solitude, loneliness and isolation we find repeatedly in the earliest letters of the Capuchins: not only the quiet solitude of living by oneself, or the unpredictability of travelling alone, but also the all-consuming worry and fear about the fate of friends who were themselves living and travelling on their own. Writing from Tripoli in 1640, Brice de Rennes noted that he ‘was alone most of the time, on account of the small number of clerics we are here’.Footnote 32 On the same day, less than fifty miles away in Beirut, another missionary confessed that he was contemplating leaving the mission and returning to France. He did not want to do so, but felt that he could not persevere any longer without the company of others: ‘It is a pity to be all on one’s own as a cleric in such situations of great risk.’Footnote 33 Frequent news of the deaths of other missionaries would only reinforce these feelings of isolation. After describing a sickness from which he was slowly recovering, Brice de Rennes wrote in 1640:

It displeases me that being alone here as I am without any companions, I am unable to carry out my work. Father Gabriel has left me here alone so that he can travel to assist Father Pierre de Guingamp, who is himself alone in Cyprus. I have received news that Father Felicien de Rennes has died at Satalie [Antalya] three days after his return from Constantinople, thereby leaving Father Alexis de Lamballe alone now at Satalie, and this after he had spent six months on his own without being able to confess to anyone while Father Felicien was away in Constantinople. Your Reverence can see from this the sadness and chagrin that remains for a poor cleric who is all alone.Footnote 34

Rather than seeing this automatically as a sign of their being on the margins, we should also consider other reasons that explain the frequency of such comments by missionaries, for example the way in which everyday life in the mission must have challenged individuals who had chosen to live life under a rule, that is, within a community. How could they remain faithful to this vow when isolated in conditions that were so far from the communal modes around which the order was organized in western France? However, not all individuals felt the same way. Writing from Beirut in February 1629, Adrien de La Brosse wrote that if he ever felt he was living as a Friar Minor, ‘it is here and now’, and he claimed never to have thought, even once, of returning to France.Footnote 35

Reflections on isolation must also be seen as part of a larger missionary rhetoric aimed at recruiting more missionaries to assist with the work required in the Ottoman empire. Writing from Sidon in December 1638, Guillaume de Beaufort requested the dispatch of more missionaries: ‘Above all, take care to choose healthy men, because even with those who have only ordinary illnesses in the province, when they arrive in this country, these illnesses will increase, especially the headaches’.Footnote 36 Another missionary, writing from Tripoli in 1640, was more specific:

It seems to me that it would be preferable either to leave our [current] locations in order to be together in groups of at least two, or to abandon the missions entirely, because being here alone means we cannot travel to preach neither to the countryside nor to the city. Instead, one acts as a sort of chaplain to two or three Franks [European Christians], something which I think is better suited to the Observants than ourselves. They tell us continually that they are chaplains for the French, and I respond to them that I did not come here to preach to anyone other than local [Ottoman] Christians.Footnote 37

Beyond the question of numbers, the letters also expressed a preference for the skills and talents needed for the work of mission. Apart from obvious considerations like the need for people who could learn languages effectively, there was an acute demand for more manual labour and technical skills. Writing from Mosul in 1638, Michel de Rennes reiterated a previous request for more friars:

We ask for help in the form of four missionaries and two lay friars … . The friars should be young clerics, fervent and humble, who will live in poverty. You would do us a great deed if they could be taught bloodletting, and if they could be introduced to some carpenters to teach them how to work. Over here they have no idea what a door or window is. The friars will also need to bring tools with them from France, because they do not have [good ones here] and they only use axes for all of their projects.Footnote 38

The assumption was that the presence of more friars would contribute to the making of a well-functioning household, thereby freeing up the missionaries to focus entirely on engaging with local communities. Not only does such rhetoric reflect the genuine practical needs of everyday life, but it is an important reminder of the extent to which these letters were also intended to contribute to fundraising efforts among patrons and donors in France.Footnote 39

Far from communicating a sense of being on the margins, the letters suggest the extent to which individual missionaries imagined themselves as participating in a much wider global order of Capuchins, one that had its heart in Brittany. On the most basic level, this is because the great majority of Capuchins studied in this article actually came from one of two provinces of the order, namely Brittany and Touraine, both of which in 1641 were still under the supervision of a single provincial, Raphael de Nantes.Footnote 40 The shared origins of the missionaries are also clear in the epithets used in the naming practices of those who joined the order, for example, the appellation of ‘de Nantes’ for six of them: Albert de Nantes, Blaise de Nantes, Cassien de Nantes, Charles de Nantes, Michel-Ange de Nantes and René de Nantes. In some cases, they even came from the same families. By the late seventeenth century, specific locations in the Ottoman empire had effectively been ‘twinned’ with one or another of the two provinces. Writing in 1684, a Capuchin publishing under the pseudonym Michel Febvre explained that missionaries originally from Touraine tended to be dispatched to Cyprus, Aleppo, Cairo, Diyarbakir, Mosul and Baghdad, while those from Brittany were based mainly in Damascus, Tripoli, Beirut, Sidon and Mount Lebanon.Footnote 41 Moreover, a close reading of the letters makes clear that in addition to maintaining a correspondence between Brittany and the Ottoman empire, Capuchins living in the Ottoman empire also regularly exchanged letters with one another.

If they retained a close link to Brittany, and to one another, the early Capuchins also envisioned themselves as part of a global Capuchin network extending across North Africa, the Caribbean and the Americas. The letters show Capuchins in the Ottoman empire occasionally comparing their own experiences with those of friends based in Morocco, Canada and Guinea. Writing from Sidon in 1626, for example, Gilles de Loches thanked God that he was being treated better by the locals than his counterparts who had gone to Morocco in 1624.Footnote 42 In 1636, another missionary wrote from Aleppo to ask Raphael de Nantes whether he could send him any news of whether ‘there are Capuchins of our province in Canada’ and of those who had travelled to Guinea ‘what good have they accomplished, have they returned, and if so from which Guinea (because there are two)’.Footnote 43 In return for this news, he reassured Raphael de Nantes that ‘all our missionaries in Persia, Egypt, and Palestine are well.’ In this way, the early Capuchin missions were constituted by a group of individuals who shared a common origin in as much as they came from the same region in western France, and in some cases, even from the same families.Footnote 44 A more refined prosopography could help better understand the proximity of individual Capuchins to one another, but what is clear here is the sense that through the work of the Capuchins, Brittany had itself been transplanted into the Ottoman empire.

III. A ‘Babylon of Confusion’: The Specificity of the Ottoman World

Across the great distance that separated Brittany and Aleppo, a global order of epistolary communication worked against any sense of being on the margins of Christendom. Yet this impression of simultaneity should not be confused with the idea that the experience of Capuchins in the Ottoman empire resembled that of Capuchins living in other parts of the world. Instead, the Capuchins themselves quickly developed a sense of the specificity of their circumstances in the Ottoman empire. Unlike in Morocco, for example, where their counterparts lived among Muslim communities, the Capuchins in the Ottoman empire focused their missionary work mainly on local Christian communities. Ottoman Christians constituted a patchwork of communities of different languages, theologies and liturgical traditions, in which one of the few characteristics they shared in common was their legal status as dhimmīs, or non-Muslim subjects, of the Ottoman sultan. Some of these Christian communities, such as the Copts, traced their origins back to the apostolic missions of the early Christian church; others celebrated their distinctiveness, for example, the Maronites who wrote with pride of their history of close ties to Rome going back to earlier centuries.Footnote 45 In specific locations, missionaries encountered these ‘Eastern Christianities’ alongside the other communities with which they lived: Muslims, both Sunni and Shi’i, but also Yazidis, Druze and Jewish communities. Beyond their distinct confessional identities, Christian and non-Christian communities alike inhabited a complex linguistic world in which Turkish, Persian, Arabic, Greek, Armenian, Kurdish and Aramaic were spoken across the collective locations of the Capuchins.

Even in their earliest despatches, therefore, the Capuchins invoked the twin themes of ‘disorder’ and ‘Babylon’ as a way of characterizing the religious diversity they encountered in the Ottoman empire. When Michel Febvre described the Ottoman empire as a ‘true Babylon of confusion’, for example, he identified some fourteen different sects he had encountered: six Muslim (Turks, Arabs, Kurds, Turcoman, Yezidis and the Druze), six Christian (Greeks, Armenians, Syrians, Nestorians, Maronites and Copts), Jews, and a final sect that he designated as ‘sunworshippers’ (‘solaires ou chamsi’, for Arabic shamsī).Footnote 46 Febvre’s categories conflate linguistic and confessional identity, but Capuchins also saw these differences expressed in physical ways. As Gilles de Loches described in 1628 in Sidon, ‘some people are completely white, others are entirely black, and some are olive-coloured’.Footnote 47 The impression of disorder was also rooted in the observations the Capuchins made of everyday devotions and practices, especially the blurring of confessional boundaries that they witnessed in the use of shared rituals and sacred spaces. Writing from Beirut in 1628, Adrien de La Brosse admitted that he found it difficult to ‘distinguish between different sorts [of people] here, because of the great familiarity that exists between Christians and Turks.’Footnote 48 There are various ways of understanding these comments. On the one hand, such reactions might reflect the simple fact that missionaries could not always understand local customs. On the other hand, it also reveals something of the genuine mixing of different confessions and religions that took place in the Ottoman empire, especially in the ‘everyday religion’ that James Grehan has identified in agrarian societies far from the imperial capital of Istanbul.Footnote 49 Whatever the case, it is clear that the Capuchins used these observations to construct ideas of the religious and cultural specificity of individual locations within the wider Babylon in which they found themselves. An example of this can be seen in the way in which Gilles de Loches described several locations in the region around Beirut in 1628:

There are the Raphadins who are of the religion of the Persians … . They are a very superstitious people who do not want either to drink or to dine with anyone who is not of their faith. These people comprise some seven or eight hundred villages in this country, and they are very difficult to convert despite the fact that they have more affection for the French than any other nation … . We also have Turkmen … in the mountains and the plains. These people are docile and speak the Turkish language … . Moreover, there are the Arabs who have their own law and who live always in the countryside. These groups of infidels, or Muslims, are separate from the Jews and the Christians, of whom only the Maronites are Catholic. In Sidon, there are mostly Greeks, small numbers of Armenians, and a handful of Maronites. But in Damascus, Tripoli, and Jerusalem, you will find Abyssinians, Copts, Jacobites, and Nestorians.Footnote 50

Moreover, distinctions made about specific localities developed in tandem with the crystallization of ideas about specific communities. By 1627, the Druze were assumed to have ‘no religion’; by 1634, the Mandeans were regarded simply as Christians who preserved a particular devotion for John the Baptist; and in 1640, Michel-Ange de Nantes could write that the Nestorians, one of the Christian communities in the region around Baghdad, were the ‘least liked’ by other Ottoman Christians.Footnote 51 In some cases, it is very striking how quickly an individual might develop such views. Only four months after his arrival in Sidon in 1627, Thomas de Saint-Calais could write optimistically that ‘Having arrived in this country, I find a completely new world, which I have never seen before … nowhere near as diabolical as [I] thought. If liberty is given [to us], we will convert the whole country in no time’.Footnote 52 These views also contributed to strategic assessments about which locations were better suited for the presence of Capuchin missions. In 1637, Etienne de Châtellerault criticized the focus of the Capuchins on Ottoman cities like Aleppo, arguing instead that smaller towns like Mardin, Diyarbakir and Urfa were a better destination for new missions. Not only were there more Christians residing in such towns, but the people living there were ‘very docile’ and open to evangelism.Footnote 53

It is striking that the letters exchanged between Capuchins differs in tone from the writings that Capuchin writers composed for audiences outside the order. Where NAF 10220 suggests an attention to the specificity of the Ottoman empire, letters composed for non-Capuchin audiences, at least in this letter book, fold Ottoman distinctiveness into a more generic rhetoric about disputation between Christianity and Islam. In the few letters in the collection that were sent to the Propaganda Fide, for example, Capuchins made much of the time they spent engaged in theological disputations with Ottoman Christians and Muslims. Consider one account sent by Michel de Rennes to Rome in June 1641, which described the conversations he had held with a Muslim qadi, or judge, visiting from Cyprus. As Michel de Rennes told the story, the qadi had been so moved by their conversations that before returning to Cyprus he had asked him for a copy of an Arabic Gospel because he had ‘lived as a Christian in his heart’ (‘il demeura chrestien en son coeur’). After returning to Cyprus, the qadi began to preach publicly about the superiority of the Gospels, at which point he was imprisoned under the trumped-up charge of having gone mad. Given a chance to redeem himself eight days later, the qadi was released, only to be later found proclaiming in front of an assembled crowd that Christianity was superior to Islam. The crowd set upon and killed him. The message of Michel de Rennes’s letter was clear enough to readers in Rome: the efforts of the Capuchins had inspired a Muslim convert to sacrifice his life for Christianity in a way that recalled a much longer tradition of Christian polemics about Islam.Footnote 54

This polemical interest in disputation was also suggested in works that were printed and published by Capuchin authors. An example from a later period is a book first published in Latin by the Propaganda Fide, entitled The Book comprising Answers of the People of the Holy Catholic Universal Apostolic Church to the Objections of the Muslims, Jews and Heretics who oppose the Catholics. Footnote 55 Written by Michele Febvre, the author who, as discussed above, had invoked the imagery of a ‘Babylon of confusion’, the book was subsequently translated into Arabic and Armenian. The topics in the book were aimed to assist in the refutation of Muslims, Jews and especially Eastern Christians. Judging from the small size of the book, some have suggested it was intended to support the everyday work of the Capuchins; however, as Feras Krimsti has argued, it would have been unthinkable to travel around the Ottoman empire carrying such a potentially inflammatory work written in Arabic.Footnote 56

Tales of martyrdom and refutations of Islam: these sorts of works appear at first to reinforce a sense of the Capuchins occupying an ambiguous and timeless space on the frontiers between Christendom and the Islamic world. However, one must be cautious not to use such sources as a window into the experience of Capuchin missionaries in this period. Unlike the letters under study, these sources were not written by and for the Capuchins. Instead, they offer a glimpse into what wider Catholic audiences wanted to hear from the Capuchins, and they cannot provide a useful indication of their actual undertakings on the ground. To understand the Capuchins’ attitudes to the specificity of the Ottoman empire, we need to turn instead to the critical work of reading the letters for what they reveal about how the Capuchins viewed their own positions within local Ottoman societies.

IV. Proximity and Distance in Everyday Life

NAF 10220 is a testament to the main activities that the early Capuchins focused on in the Ottoman empire. Most individuals spent their time in three main ways: the study of local languages, chief among them Arabic; the translation of devotional works into local languages and, to a lesser extent, the composition of new, original works; and the daily participation in the everyday lives and religious devotions of Eastern Christian communities. Taken together, these three activities all shared a common goal, namely to reduce the distance between Capuchins and the societies in which they lived.

Most missionaries began to study local languages only after their arrival in the Ottoman empire.Footnote 57 Decades later, this would become a point of derision among later writers, most notably Eusèbe Renaudot, the French theologian and orientalist who, in 1701, wrote a fierce critique of the Capuchins as part of a treatise submitted to the papacy on the limited progress made in the spread of Catholicism in the Ottoman empire.Footnote 58 Nonetheless, there is already in these early missions clear evidence of an engagement with the study of Ottoman languages, especially Arabic.Footnote 59 As Adrien de La Brosse wrote in 1629, knowledge of Arabic, in particular, was highly valued among Ottoman Christians and also important from a practical perspective: ‘It is necessary to learn it, and speak it, because we are most of the time without any interpreters.’Footnote 60 Written Arabic also offered a way of bypassing the patchwork of colloquial languages spoken in the region, which La Brosse had described in the same letter as ‘extremely difficult Moorish languages, different from both Turkish and Arabic’.Footnote 61 Less clear are the methods the Capuchins used for studying Arabic. Requests were occasionally made for the dispatch of grammars and lexica that had been published in Europe, although it is unclear whether any of these requests were ever fulfilled.Footnote 62 However, surviving evidence suggests that, very early on, the Capuchins began to develop their own study materials such as the ‘dictionary of vulgar [that is, colloquial spoken] Arabic’ that Albert de Nantes was reported to have completed in Beirut as early as 1629.Footnote 63 Moreover, there was a cumulative and collaborative aspect to language study: a missionary who knew a language could teach it to one who had just arrived, an approach that was effective in the case of Arabic, but less so for languages studied by only one or two individuals, for example Syriac and Armenian.Footnote 64

The emphasis on language study in the letters should not distract us from the fact that, then as now, some people simply picked up languages more easily than others. Shortly after his arrival in Tripoli in July 1636, Brice de Rennes described how he had impressed Ottoman Christians by the progress he had already made in both Arabic and Turkish. By his account, he had learned enough Arabic in five months to be able to give as good a sermon in Arabic as in French. That was because, in his words, ‘I’ve received a God-given grace for languages, which is why I am not at all surprised [by my progress].’Footnote 65 Others were apparently less blessed: in 1632, Jean-Chrysostome d’Angers was forced to return to France after having spent three years in Aleppo trying to learn Arabic, but with no success.Footnote 66

Most importantly, the study of Arabic provided Capuchins with an opportunity to become closer to local communities by receiving language instruction directly from Ottoman Christians. It is difficult to know much about these local teachers, most of whom are not identified by name in the correspondence. However, in those cases where it is possible to identify them, it becomes clear that the Capuchins often studied Arabic with individuals whom other sources show to have had reputations in their own communities as celebrated scholars and prolific copyists. This was the case even for the gifted Brice de Rennes who, it appears, studied Arabic with Yuhanna al-Ghurayr, a Syrian Orthodox priest and later bishop of Damascus, who was responsible for composing over fifty manuscript works.Footnote 67 While scholars such as Aurélien Girard and Giovanni Pizzorusso have transformed our understanding of the consolidation of a linguistic register of missionary and Catholic Arabic, further work still remains to understand the place of language study in cultivating personal ties between Capuchins and Ottoman Christians and Muslims.Footnote 68

A second main focus of the daily lives of Capuchins involved the copying, translation and composition of Arabic texts, again often in collaboration with local Ottoman Christians. These unique works tend to survive today, if at all, only in small numbers of manuscript copies in church libraries and monastic collections in the Middle East, many of which are not easily accessible to scholars. However, a recent series of ground-breaking digitization projects has unearthed an entire corpus of manuscripts still in need of systematic study. In NAF 10220, it is possible to identify several categories of works that caught the attention of the earliest Capuchins. These included: sacred texts, for example the Gospels, the New Testament, and in time, the Psalter; spiritual works, normally translations of European Catholic Reformation writers; pastoral works, including catechisms; polemical works; and linguistic works, including grammars and dictionaries. Although these activities gained real momentum only in the second half of the seventeenth century, it is clear that by 1640, Capuchins were already occupied with the translation and composition of texts, and that these activities were being carried out at several different locations across the Ottoman empire.Footnote 69 One reason for this was that translation was an activity that could be carried out virtually anywhere. While travelling on the caravan from Aleppo to Baghdad, for example, Juste de Beauvais was reported to have completed an Arabic translation of Richelieu’s catechism. Such efforts also reflected the usefulness of having manuscripts to offer as gifts to local notables. On the same journey, Juste de Beauvais presented some Armenian priests in Urfa with a copy of a translation of Bellarmine’s catechism into Arabic that he had completed while travelling.Footnote 70

As with other mobile communities of Catholics in this period, the work of translation afforded Capuchins a way of reducing the distance between themselves and the worlds they had left behind.Footnote 71 In some cases, missionaries selected works for translation that reflected perfectly the reforming spirit of early modern Catholicism in Rome. This was the case, for example, with a three-volume abridgement of the Annales Ecclesisastici, the triumphant history of the church written in the sixteenth century by Cesare Baronio. The Annales offered a history of the church from the establishment of Christianity at the start of the first millennium until the present. Brice de Rennes had started working on an Arabic translation while living in Damascus in 1644, and he completed the work with the help of local scribes, including a man whom he identifies only as a deacon named Yusuf (‘Yusuf Shammās’).Footnote 72 Brice spent six years working on the translation before he travelled to Rome in 1650, where he published the first two volumes of the work. He returned to Syria in 1655, where he continued his work on a third and final volume.Footnote 73 Originally written in Rome in the sixteenth century, rendered a hundred years later into Arabic in Damascus, printed on the Propaganda Fide press in Rome, and circulated in physical copies back to the Ottoman empire, the three volumes comprise over 1,000 pages in total, yet Brice de Rennes’s Arabic translation still lacks any systematic, critical study.Footnote 74

The act of translating Baronius into Arabic captures something important about the ambitions of the early Capuchins, but it would be misleading to characterize the significance of such works as being primarily scholarly or even evangelical. Rather, the act of collaborative translation afforded Capuchins with an opportunity for daily conversations and personal interactions with Ottoman Christians. The correspondence provides us with countless examples of how capacious these forms of participation could be, from attempts to treat the medical needs of Ottoman subjects, to engaging in local business transactions, to education of the local youth. Chief among these was an activity referred to throughout the letters by the term ‘preaching’ (prêcher). The term is used to describe those situations in which the Capuchins sought to evangelize Ottoman Christians through sermons, lessons and participation in liturgical services. Writing from Tripoli in February 1637, for example, Brice de Rennes offered a moving account of the first time he ‘preached’ in the presence of some three hundred Christians. This appears to have involved him reciting the Our Father in Arabic, which incited the tears of those around him: ‘They came to me afterwards and kissed my hand, saying what I had preached was like a pearl’.Footnote 75 Some months later, further east near Mardin, Juste de Beauvais preached to a village of Syrian Orthodox Christians. Etienne de Châtellerault described the experience in the following way:

Father Juste preached in Arabic, and after he had finished, the entire crowd came to him to kiss his hands. Whether he liked it or not, he accepted it, which is why I permitted it as well. They called him ‘Abona Emoutran’ [Arabic, abūna and mutrān, a combination of the titles used to address priests and bishops, respectively], which in our language means ‘Our Father the Bishop’. As for me, they called me ‘Abona Elcacia’ [Arabic, qasīs, meaning priest], which in our language signifies ‘Our Father the Priest’. We spent our entire visit to this village in possession of these marks of distinction (‘avec ces qualités’).Footnote 76

Clearly, this reference to preaching refers to an official permission obtained from higher clergy which allowed the Capuchins to preach in the churches of Eastern Christian communities. In 1637, Michel-Ange de Nantes provided a fascinating account of how his companion, Juste de Beauvais, had used one such permission to insinuate himself into the local Maronite community in Aleppo. This was how one missionary described Juste de Beauvais’s entrance into the church:

Having received the letter from the Patriarch giving him permission to preach, Father Juste went one Sunday to the Maronite church and had the Patriarch’s letter read out loud. After it was read, he told the assembled crowd in a loud voice in Arabic that if there was anyone from among their priests or deacons who did not agree to our Fathers preaching in their church, in contravention to what had been expressed by their Patriarch, then he would not do anything contrary to their wishes. He went even further, saying that if there was anyone at all in their community – if even just one woman – who did not want them to preach in their church, he would not do so … . There were four priests present of whom two had been persuaded by other clerics to try and prevent our Fathers from preaching, but they did not dare to oppose us publicly and formally [in such circumstances]. All the common people declared loudly that they wanted us to preach, so Father Juste left, having agreed all of these arrangements.Footnote 77

On this basis, the Capuchins continued to preach at weekly services for the Maronites in Aleppo. One can only speculate what local priests made of this brazen behaviour, but as Michel-Ange de Nantes noted with glee in another letter, ‘no one dared challenge the authority of their patriarch in this regard’.Footnote 78

At the same time, references to preaching should be understood as a sort of shorthand for a wide spectrum of forms of participation that the Capuchins used to make themselves omnipresent in the devotional lives of Ottoman Christians. They attended local liturgies; they were present at local funerals; they even sought opportunities to live in the residences of the higher clergy.Footnote 79 Writing from Aleppo in January 1634, Michel de Rennes described how he had gradually established himself as the confessor to one of the bishops of Aleppo whilst he continued to study Arabic: he hoped, thereby, to give ‘some of the first rudiments of our faith to many people, both the notables and the lowly’.Footnote 80 This strategy also applied to the laity, with whom marks of ‘good affection’ were frequently reported.Footnote 81 Michel-Ange de Nantes summed up the situation well when he wrote from Mosul in 1638 that ‘These people hold us in such high affection that they want us to bless their houses and they stop us on the road to take us into their houses. … We move with much ease among them’.Footnote 82

In the areas of language study, the production of manuscripts, and everyday devotions, therefore, the Capuchins’ efforts were aimed at achieving a single goal: the cultivation of personal relationships with and above all proximity to Ottoman Christians. This desire for proximity was also a function of the fact that the missionaries relied – in a material sense – on local communities for financial resources, political support, access to markets, and even for the provision of buildings and accommodation in which to live. Christian Windler has shown, for a different context, the extent to which Carmelites relied on local economies for a good portion of their livelihood.Footnote 83 Although we lack the sort of account books that would provide such a level of detail for the early Capuchins, the theme of their reliance on charity is an oft-repeated topic in the correspondence. Writing from Babylon in 1638, for example, Etienne de Châtellerault shared with Raphael de Nantes in Brittany the stories that were circulating about Juste de Beauvais, one of the earliest missionaries to establish himself in Baghdad in 1628. He was reputed to have spent an entire year living with the poor, begging for alms, and relying on the charity of Ottoman Christians and even the local Ottoman pasha.Footnote 84 Ten years later, another missionary, Gabriel d’Alençon in Beirut, would still write, with admiration, that the mission in Baghdad continued to depend entirely on alms.Footnote 85 Not only a reflection of local realities, these claims also made for effective rhetoric in the circulars that were regularly sent across Europe to raise funds for the Capuchins from Catholic patrons.

The dependence on local communities extended even to a reliance on political support from Ottoman officials and local elites. Because the political fortunes of such notables could change rapidly, the early Capuchins experienced a distinct form of precarity that exposed them to local intrigues, factionalism, and the complicated relations that linked provinces back to the imperial capital in Istanbul. The earliest Capuchins to arrive in Beirut, for example, had quickly endeared themselves with Fakhr al-Din al-Maani, the local Druze emir of Mount Lebanon. However, all this changed in 1633 when Fakhr al-Din was arrested under suspicion of planning a rebellion against the Ottoman state.Footnote 86 It would take years for those seen as allies of Fakhr al-Din to recover from his fall from grace, including the Capuchins, some of whom had also been arrested and transferred with him to Istanbul. Likewise, the correspondence is full of countless stories of the complicated challenges that faced the early Capuchins when it came to navigating local politics. Importantly, these political circumstances differed from one location to another, meaning that accumulating local knowledge in one place did not necessarily translate into progress in another. Far from the courtly rhythms of the imperial capital in Istanbul, the learning curve for Capuchins in this period was very steep indeed.

This precarity may explain why so little reference to the topic of conversion is made in NAF 10220. The word itself is rarely used by any of the letter-writers; nor do the letters contain the regular reports of numbers of converts that one finds, for example, among the writings of Carmelites in this period.Footnote 87 In some ways, this silence may reflect the extent to which the early Capuchins struggled to make sense of what exactly it meant to convert people who were, ostensibly, already Christians. Here the correspondence suggests a mix of the facile and the confused, at any rate certainly nothing that can be identified as a coherent Capuchin ‘approach’ to conversion. Some missionaries in this period imagined a sort of top-down conversion of Ottoman Christians. Michel-Ange de Nantes wrote in 1635 that:

if we win a Patriarch, and his clerics, then we win all the people who are submitted to him, because each church having its own bishop in this country, new bishops are only made from their clergy [who are already submitted to them]. If we win the youth, we win everything.Footnote 88

Others reported initial success in developing good relationships with local Christians, but they wondered where to go from there. Writing from Tripoli in 1640, Gabriel d’Alençon reflected on these challenges: having described the ‘good affection’ he had developed with the Syrian Orthodox community in Tripoli, many of whom affirmed that they accepted the supremacy of the pope, he wrote to Raphael de Nantes for further advice on what he should do next.

I want to know your advice on the matter. Are they obliged to leave their sect, or can they receive the sacraments of their priests while acknowledging nonetheless the sovereignty of the Roman Pontiff and all that is believed and taught by the Roman Church? And must we absolve as heretics those who come to us and say that they have never had any differences between us and them?Footnote 89

These anxieties point to the early signs of a set of doubts and questions that would develop decades later into what Cesare Santus has demonstrated to be full-fledged debates about communicatio in sacris, that is, the participation of Catholic converts in the rituals and ceremonies of their traditionalist communities.Footnote 90

Beyond conversion, very little attention was given to the subject of church union, which would become an important priority in later Catholic missions to Eastern Christianity. In some ways, this is unsurprising given that the Capuchins, unlike the Jesuits, were not known for their contributions to theological debate or their knowledge of church history. Instead, the correspondence shows that Capuchins focused their efforts mainly on persuading the higher clergy to accept the authority of the pope in Rome.Footnote 91 Writing from Tripoli in 1640, Gabriel d’Alençon reported that he had met with the Greeks and Syrian Orthodox who had agreed to recognize the pope as ‘the sovereign pontiff’, even if there were some who, although accepting the pope, wished to remain ‘in their own sect’.Footnote 92 Likewise, the few accounts of meetings between Capuchins and the patriarchs of specific Christian communities tend to focus either on local matters – for example, obtaining permission to preach – or on the authority of the pope, but rarely on securing ‘professions of faith’ that would confirm the patriarch’s conformity with Roman doctrine.Footnote 93 Above all, the reluctance to engage with issues of union reflected the reality that doing so risked alienating the Capuchins from the very communities to which they were trying to gain access. This awareness created the possibility for disagreements to emerge between the activities of the early Capuchins and expectations placed on them by the Propaganda Fide. In March 1638, the Capuchins in Mosul received instructions from Rome encouraging Juste de Beauvais to travel to Rabban Hormizd, the seat of the patriarchate of the Church of the East, in order to persuade the Nestorians to agree to a union with Rome.Footnote 94 Juste de Beauvais preferred instead to remain in Baghdad as his companions tried to explain to Propaganda officials in Rome:

We have taken the view that to effect a union, it is more important to know them [the Nestorians], to win their friendship and thereby to render them more open [‘plus facile’] to the idea [of union]. Otherwise, if those who have never met us and who do not know us well find that we speak immediately about union, we will be pushed away rather than advanced [in our work].Footnote 95

In other words, the very act of bringing Eastern Christians closer to Rome risked being counter-productive: it could result in the Capuchins’ being pushed to the margins of the local societies in which they lived. This may be why some missionaries in this period looked for less explicit ways to facilitate the conformity of Eastern Christians with Roman doctrine, for example through the translation of Roman canon law into Arabic.Footnote 96

V. Conclusion

Standing in Europe, it is rather easy to be taken in by the story of a global, triumphant Catholicism that drew the margins of the world into a centre of gravity based around Rome. However, listening to the voices of Capuchins in the letters they sent to one another, one is forced to wonder: where is the centre; where are the margins; and indeed, who decides which is which? This article has suggested that traditional models of centres and peripheries – constructed around as yet unrefined ideas of geography and distance – are not suitable for recovering the actual experience of mobility as lived by Capuchins in the earliest years of their mission to the Ottoman empire. Through epistolary communication, individual Capuchins felt themselves part of a global order based in Brittany even whilst they focused their daily lives on finding a place at the centre of Ottoman Christian communities. No matter where they were in the Ottoman empire, they developed a distinct sense of the specificity of place. This was also, we must remember, only one of several competing views of what mission should look like in the Ottoman empire, nor is it a foregone conclusion that other orders would act in the same way, be they Franciscans, Jesuits or Carmelites. Whatever the case, modern historians need to incorporate ideas of specificity more effectively into our understandings of the shape, scale and places of ‘global Catholicism’. When we do so, we may well find that the margins are in our minds, if they are there at all.

Perhaps the greatest sign of the confidence the early Capuchins felt in their place in the world comes from some of the last letters in the collection. Writing from Mosul in 1640, Michel-Ange de Nantes reports an encounter with a local priest whom he had met on the road. The priest asked him:

To what end do you seek to persuade our Patriarch of your lies? … . Why are you trying to seduce us away from our religion and obedience to our patriarch in order to impose on us the law and religion of the Franks? Truly, you act in this way as if we do not already have our own shepherds and bishops to look after our salvation.Footnote 97

Months later, Michel-Ange de Nantes reported another encounter with a man who spoke even more directly when he asked him in the presence of the patriarch: ‘When will you leave this city?’. To this question, the Capuchin’s response was deceivingly straightforward: ‘If we ever do leave, there will be others who come in our place.’Footnote 98 This reply betrays little sense of a man who felt himself to be on the margins, far from the centre of Christianity. Instead, Michel-Ange de Nantes seems convicted of his rootedness and permanence, if not for himself than certainly on behalf of his order. His was a community that had its centre not in Rome, but in the neighbourhoods of Brittany, where he and his compatriots shared childhoods, memories, and sometimes even families, long before they ever arrived in the Ottoman empire.

In so much as this article is based only on the voices of Capuchins, further research remains to incorporate alongside these voices the perspectives of Ottoman Christians themselves. When we do so, we come into direct contact with communities of Eastern Christians who regarded themselves, if not as the centre of Christianity, then at least as autonomous Christians, each with their own independent visions of their place in the world. Here at the level of everyday life in communities scattered across different localities in the Ottoman empire, we begin to glimpse the possibility of a third way of imagining the ‘missionary theatre’ of the Ottoman empire: not a world of Eastern Christianity suspended in time on the margins of Western Christendom, nor simply another stage for the performance of global Catholic ambitions, but rather what Peter Brown has called, in a different context, a series of ‘little Romes’, that is, an archipelago of communities, each with its own particular set of priorities, worldviews and aspirations.Footnote 99 For some of these ‘little Romes’, friendship and proximity with Roman Catholicism was a path they were willing to explore so long as they could do so on their own terms. This was something that was well understood by the earliest Capuchins who lived in their midst, trying day after day to carve out for themselves a secure place in these other worlds.