Introduction

Austrian politics in 2019 was dominated by a series of dramatic events. The publication of a scandalous video of the Freedom Party of Austria/Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) – Die Freiheitlichen (FPÖ) party leader and deputy government leader Heinz‐Christian Strache in May led to the break‐up of the right‐wing ÖVP–FPÖ coalition headed by Federal Chancellor and Austrian People's Party/Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) party leader Sebastian Kurz. The resulting ÖVP minority Cabinet was toppled a week later by the first ever successful parliamentary no‐confidence vote. President Alexander van der Bellen played a central role in forming the next government. A caretaker government, led by former President of the Constitutional Court, Brigitte Bierlein, the first female government head ever of the first non‐partisan government (in the Second Republic), cautiously ruled for the remainder of the year. Snap elections at the end of September brought a huge success for Kurz and the ÖVP. The Greens – the Green Alternative/Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (GRÜNE) made an impressive comeback two years after dropping out of the lower house in the previous election. At year's end a coalition government between the ÖVP and the Greens was finalized, the first between the two parties at the national level.

Election report

European Parliamentary elections, 26 May 2019

An unexciting European elections campaign was jolted by the publication of the Ibiza affair video (see below) just nine days before election day. A quickly unfolding government break‐up with almost all FPÖ ministers resigning in solidarity with Minister of the Interior Kickl whom the ÖVP wanted dismissed (see Cabinet report below) and a looming non‐confidence vote against the remaining ÖVP minority Cabinet made the European elections a poll on the parties’ responsibility for these dramatic events.

Turnout rose strongly from 45.4 percentage points in 2014 to 59.8 percent in 2019 (+14.4 percentage points) Table 1. The ÖVP was the only party with major gains, increasing its vote share to 34.6 percent (+7.6 percentage points) and the number of seats to seven (+2). The Social Democratic Party of Austria/Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) obtained 23.9 percent (−0.2) and remained at five seats. The FPÖ obtained 17.2 percent (−2.5) and three seats (−1). The Greens, who ran with their party leader Werner Kogler as top candidate, won 14.1 percent (−0.4) and two seats (−1). NEOS/NEOS – Das Neue Europa (NEOS) obtained 8.4 percent (+0.3) and remained at one seat. Other parties together had only 1.8 percent of the votes. In previous European elections, four other parties collectively had 6.6 percent of the valid votes.

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament in Austria in 2019

Notes: aParty names on the ballot paper.

bIn the 2014 EP elections, the Communist Party was a member of the electoral alliance ‘Different Europe’ (ANDERS) consisting of the KPÖ, Pirate Party, Change and the former MEP Martin Ehrenhauser. Change in votes compares the different electoral alliances.

Source: Federal Ministry of the Interior Reference Eberl, Kathirgamalingam, Boomgaarden, Juárez‐Gámiz, Holtz‐Bacha and Schroeder2020b, https://www.bmi.gv.at/412/Europawahlen/Europawahl_2019/.

Parliamentary elections, 29 September 2019

After the end of the FPÖ–ÖVP coalition, an ÖVP minority government was widely seen as a temporary solution only. Most parties wanted snap elections in the autumn. The SPÖ in opposition faced a choice between campaigning against the ÖVP with Kurz leading a minority Cabinet or, by ousting him with a no‐confidence motion, on an equal footing under a caretaker government. The FPÖ declared it would support the ousting of Kurz. One day after the European elections, a no‐confidence vote was passed against the complete Cabinet with the votes of the SPÖ, FPÖ and Now (JETZT). The subsequent Bierlein caretaker government could have proposed to the President the dissolution of the lower house, but followed the tradition of letting the chamber decide the end of its term. The National Council voted to prematurely dissolve on a private member's bill jointly introduced by the ÖVP, SPÖ, FPÖ and NEOS in June, allowing for some parliamentary sessions in which costly private members’ bills were passed by various voting coalitions.

After his ousting as Federal Chancellor, Kurz declined to remain even for a day as provisional head of government. He also did not return to his seat in the lower house. The party toyed with an image of Kurz as a ‘political martyr’ who felled by Parliament would be brought back as government leader by the voters in the upcoming election. Polls put the ÖVP clearly ahead of all other parties. The FPÖ campaigned for a renewal of the coalition with the ÖVP and likened the government break‐up to a marital crisis. The SPÖ was not thrilled about becoming a junior partner in a coalition with the ÖVP. The ÖVP remained non‐committal on the issue of future partners. Kurz even brought up the idea of a minority cabinet ruling after the election through ad hoc parliamentary coalitions. NEOS was in favour of government participation, though too small for a two‐party coalition. The Greens had very good prospects of returning to the lower house, but evaded the question of government participation. The Greens’ campaign topics enjoyed a strong international backwind from the Fridays for Future movement and the party profited from the woes of Now (JETZT), the renamed green splinter party Now – List Pilz/Jetzt – Liste Pilz that had spectacularly supplanted it in the previous election (Jenny 2017, 2019d). Most Now MPs were disillusioned with party founder and de facto leader Peter Pilz. Withdrawing from politics or switching to the Greens they withheld support for another candidacy of Now (JETZT), which required three signatures of support from sitting MPs or a much larger number of signatures by citizens. A non‐affiliated MP helped put Now (JETZT) on the ballot again. For more details on the election campaigns, see Eberl et al. (2020a, Reference Eberl, Kathirgamalingam, Boomgaarden, Juárez‐Gámiz, Holtz‐Bacha and Schroeder2020b).

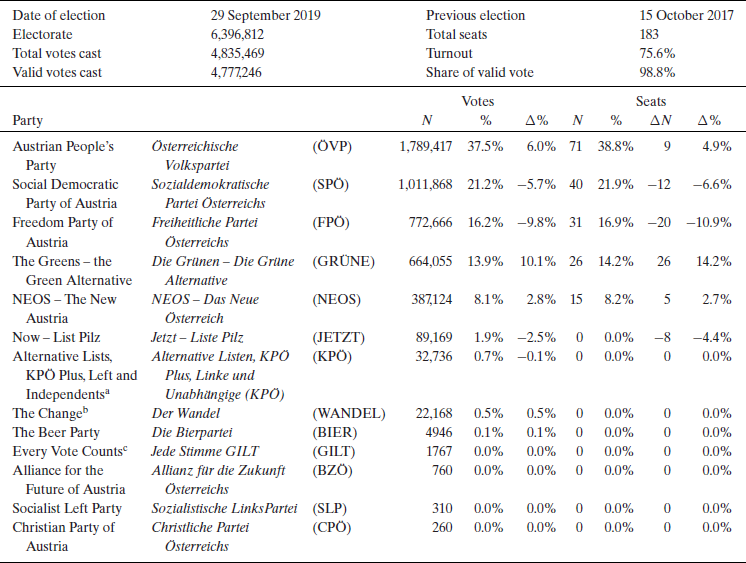

The result of the parliamentary elections on 29 September was an even greater success for Sebastian Kurz than in the 2017 elections. The Greens made a comeback to the lower house with their best result ever, after they had failed the entry threshold two years before. The ÖVP came in far ahead of the other parties with 37.5 percent of the vote (+6.0 percentage points) and 71 seats (+9) Table 2. While the SPÖ remained the second largest party, its 21.2 percent of the vote (−5.7) and 50 seats (−12) marked a new low for the party in national elections. The FPÖ received the expected pummelling for the Ibiza scandal and investigations of illegal party financing and expenses and dropped to 16.2 percent of the vote (−9.8) and 31 seats (−20). The Greens rose to 13.9 percent (+10.1) of the vote and from zero to 26 seats. NEOS also increased its vote share to 8.1 percent (+2.8) and received 15 seats (+5). JETZT failed the entry threshold of 4 percent by a wide margin with only 1.9 percent of the vote (−2.5). Other parties collected negligible numbers of votes.

Table 2. Elections to the lower house (Nationalrat) in Austria in 2019

Notes: aAn electoral alliance of small left‐wing lists.

bParty name on the ballot paper was ‘Wandel – Aufbruch in ein gemeinwohlorientiertes Morgen mit guter Arbeit, leistbarem Wohnen und radikaler Klimapolitik. Es gibt viel zu gewinnen’.

cParty name and acronym as listed on the ballot paper. The party uses G!LT as its acronym.

Source: Federal Ministry of the Interior 2019b, https://bmi.gv.at/412/Nationalratswahlen/Nationalratswahl_2019/

While party system concentration remained stable – with an effective number of parties of 4.2 in 2019 and 4.1 in 2017 – numerically the ÖVP could now form a majority coalition with either the SPÖ, FPÖ or the Greens. In light of their losses neither the SPÖ nor the FPÖ wanted to join, though, and public expectations focused on the Greens as the second winner of the elections. Tasked by the President with forming a new government. Kurz held exploratory talks with the parliamentary parties. Then ÖVP and Greens negotiated from mid‐November to the end of the year. On New Year's Day, party leaders Kurz and Kogler announced their agreement on the first government coalition between a moderate right and a green–left party at the national level.

Two regional elections took place after the national elections, in Vorarlberg on 13 October and in Styria on 24 November. The FPÖ suffered big losses in both elections. In Vorarlberg it dropped to 13.9 percent (−9.5) of the votes and five (−4) seats. All other parties in the regional Parliament registered small vote and seat gains. The ÖVP obtained 43.5 percent (+1.7) and 17 seats (+1); Greens 18.9 percent (+1.7) and seven seats (+1); the SPÖ 9.5 percent (+0.7) and four seats (+1); and NEOS 8.5 percent (+1.6) and two (+1) seats. The dominant ÖVP, led by Land Governor Markus Wallner, resumed the government coalition with the Greens, which replaced the FPÖ as second largest party in the regional Parliament. Due to the election result, the FPÖ lost a seat in the upper house of the national Parliament to the Greens.

In Styria, where a coalition between the ÖVP and SPÖ ruled, the regional elections were held a year ahead of schedule. In August, the ÖVP Land Governor Hermann Schützenhöfer announced he wanted premature elections. The Greens were in favour, too. Both parties expected to profit from a backwind from national politics. The motion was introduced by the FPÖ, however, which apparently wanted to limit damage from negative events at the national level through early elections. The party lost one‐third of its voters, nonetheless. The SPÖ suffered heavy losses as well. The ÖVP obtained 36.1 percent (+7.6) and 18 (+4) seats Table 3; the SPÖ 23 percent (−6.3) and 12 (−3) seats; the FPÖ 17.5 percent (−9.3) and eight (−6) seats; the Greens 12.1 (+5.4) and six (+3) seats; the Communist Party plus others/KPÖ Plus – European Left, offene Liste (KPÖ) 6.0 percent (+1.8) and two (0) seats; and NEOS 5.4 percent (+2.7) and also two (+2) seats. SPÖ Land party leader Michael Schickhofer stepped down and was followed by Anton Lang, who quickly accepted Schützenhöfer's offer to renew the government coalition between ÖVP and SPÖ. Due to the election result, the ÖVP and Greens gained one seat each, and the SPÖ and FPÖ lost one seat each in the upper house of the national Parliament Table 8.

Table 8. Party and gender composition of the upper house (Bundesrat) in Austria in 2019

Source: Austrian Parliament (2019).

Cabinet report

The publication of extracts from a secretly recorded video of Vice‐Chancellor and FPÖ party leader Heinz‐Christian Strache and parliamentary party leader Johann Gudenus on 17 May, a Friday just a week ahead of the European elections, by the German news websites Der Spiegel and Süddeutsche Zeitung set off a fast‐paced cascade of wide‐reaching political decisions involving actors from all major parties and turned the President into a central figure. The video recorded a meeting with a supposed niece of a Russian oligarch searching for investment opportunities in Austria that took place in Ibiza (Spain) in July 2017, a few months before the parliamentary elections that led to the formation of an ÖVP–FPÖ coalition government (Jenny 2019d). Politically explosive excerpts showed Strache and Gudenus talking about potential ways of cooperating once the FPÖ was in government, such as the steering of public tenders to selected firms, party financing via associations and acquiring control of the largest Austrian mass daily Kronen Zeitung to raise its party‐friendly coverage.

The following day Vice‐Chancellor Strache announced his resignation and named deputy party leader and Minister for Infrastructure Norbert Hofer as his successor in government and party office. Parliamentary party leader Gudenus resigned and left the party. The FPÖ’s intention to continue the coalition hit a wall, when Federal Chancellor Kurz also demanded the resignation of controversial Minister of Interior Herbert Kickl, a demand the FPÖ was unwilling to meet. However, Kurz could simply propose the Minister of Interior's dismissal to President Van der Bellen, who would likely accept it. The FPÖ threatened to withdraw all ministers and support a motion of no confidence against Kurz. On Monday evening Federal Chancellor Kurz announced he would go through with Kickl's dismissal and respond to resignations by replacing them with experts. The government coalition ended on 22 May with almost all remaining FPÖ ministers resigning, except for Foreign Minister Karin Kneissl who was not a party member Table 4. Kurz replaced them with candidates from in‐ and outside the ministerial administration. The government had effectively become a single‐party minority government.

Table 4. Cabinet composition of Kurz I in Austria in 2019

Note: aAfter the dismissal of Minister of Interior Kickl on 22 May, five of six remaining FPÖ‐nominated ministers and a state secretary resigned. The Kurz government turned into a single‐party minority government. It lost a parliamentary no‐confidence vote on 27 May and was dismissed by the President on 28 May.

Source: Österreichischer Amtskalender (Reference Jenny2018).

SPÖ party leader Rendi‐Wagner declared Austria was in a national crisis and demanded the complete Cabinet replaced. On Monday, 27 May, the SPÖ introduced a no‐confidence motion against the government, the party JETZT introduced another one against Federal Chancellor Kurz only. The broader motion was voted on first and passed with the support of the SPÖ, FPÖ and JETZT. President Van der Bellen announced dismissed ministers with Minister of Finance Löger as new Federal Chancellor, as Kurz wanted to leave immediately, would stay provisionally until he had appointed a caretaker government. The provisional Löger government lasted six days in office, replacing the just toppled Kurz government as the shortest‐lived post‐war government Table 5.

Table 5. Cabinet composition of Löger in Austria in 2019

Source: Österreichischer Amtskalender (Reference Jenny2018).

President Van der Bellen tasked the President of the Constitutional Court, Brigitte Bierlein, with forming a caretaker government, and on 3 June appointed six male and six female government ministers Table 6. After becoming the first female head of the Constitutional Court, Bierlein became the first female Federal Chancellor. Her Cabinet was also the first civil servants’ government in the Second Republic. It had no support commitments from parliamentary parties, but its ministers represented a wide range of political tendencies.

Table 6. Cabinet composition of Bierlein in Austria in 2019

Notes: aVice‐Chancellor until 3 October. Traditionally there is no post of Vice‐Chancellor in the provisional government in charge after an election, until the next government is sworn in.

bAppointed as Minister without Portfolio on 3 June and put in charge of listed affairs on 5 June.

cAdditionally put in charge of EU, Arts, Culture and Media affairs on 5 June.

Source: Österreichischer Amtskalender (Reference Jenny2018).

Federal Chancellor Bierlein stressed her government would be lean. It was a smaller Cabinet with no Vice‐Chancellor, no state secretaries and no politically appointed general secretaries in the ministries. It would refrain from major policy changes, focus on service provision and prepare for the elections. Her government mostly held on to these guidelines and enjoyed good public ratings. Minister of Defense Thomas Starlinger, a General in the Armed Forces, published a blunt assessment of much bigger budgetary needs compared with what predecessors from various parties had proposed as politically feasible defence budgets.

Parliament report

The National Council's XXVI legislative period from November 2017 to September 2019 was the third shortest period since 1945 Tables 7. Until the Ibiza scandal broke in May, parliamentary activities were mostly structured along the government‐opposition divide with the government parties ÖVP and FPÖ facing the three opposition parties SPÖ, NEOS and Now. After the coalition break‐up and especially after the non‐partisan expert Cabinet came into office, parliamentary voting coalitions became diverse.

Table 7. Party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat) in Austria in 2019

Source: Austrian Parliament (2019).

Political party report

After FPÖ party chairman Heinz‐Christian Strache, deputy party leader Norbert Hofer was designated new party leader and nominated the party's top candidate in June for the parliamentary elections and officially elected as new party chairman by the party executive on 14 September Table 9. Ending the ex‐party leader's hold on the party, however, turned into a protracted process. Ridiculed by the Ibiza video and blamed for setting up the meeting, parliamentary party group leader Johann Gudenus had immediately cut all ties with the party, while ex‐party leader Strache defended himself as a victim of a political ‘hit job’, who had been lured into a trap set by criminals.

Table 9. Changes in political parties in Austria in 2019

Sources: Der Standard (2019); Wiener Zeitung (2019).

Strache was last placed candidate on the party list for the European elections as a ‘honorary candidate’, a tactic frequently employed to collect party votes. After the Ibiza scandal and the break‐up of the coalition, however, fans of Strache expressed their support through preferential voting. Strache collected 44,750 preference votes, surpassed only by the party's top candidate Harald Vilimsky with 64,520, and far more than his designated successor Norbert Hofer, who came in third with 7461 preference votes. Because his preference votes surpassed the threshold of 5 percentage points of party votes, Strache had a claim to one of the three European Parliament seats won by the FPÖ (Federal Ministry of the Interior 2020d). In an apparent deal denied by both sides, Strache declined to take the European Parliament seat, while the FPÖ nominated his wife, Philippa Strache, party policy speaker on animal protection and employee of the parliamentary party, to a safe list position in Vienna for the upcoming national parliamentary elections. Heinz‐Christian Strache initially also remained in control of his ‘personal’ Facebook page with about 800,000 followers, until the party managed to take it away. After a judicial probe was launched into potential misuse of party funds for private expenses by the party's former ‘first couple’, the relationship between party and them soured further. Despite the party's dismal election result, Mrs Strache had – based on her list position – a claim to a parliamentary seat in the Vienna Land district. The party pressured her to resign and tried to deny her claim, but was blocked by a court. Refused membership in the parliamentary party group, Mrs Strache entered the first session of the lower house as a non‐affiliated MP. She was dismissed from the party shortly afterwards. Mr Strache was first suspended and then dismissed from the party in December.

Despite much internal criticism SPÖ party leader Pamela Rendi‐Wagner secured her unanimous nomination by the party executive as top candidate for the national election. After the party's worst ever result in the parliamentary elections and party staff reductions were announced to cope with lower public party funding intra‐party criticism increased again. An anonymous tip revealed that the party leader was more than a year in arrears in paying her party dues. However, no contender stepped up to challenge Rendi‐Wagner's position as party leader.

Institutional change report

No major changes were passed in 2019. President Van der Bellen repeatedly lauded the federal constitution’ precision and clarity on the politically sensitive situations confronted (Salzburger Nachrichten 2019).

Issues in national politics

Overshadowed by bigger issues, the three people's initiatives introduced in 2019 were among the worst faring ever. A people's initiative on holding a referendum on the European Union–Canada Free Trade Agreement (CETA) collected 0.45 percent signatures of support, on having more compulsory referendums 0.43 percent, and on the introduction of an unconditional basic income 1.1 percent (Federal Ministry of the Interior 2019c).