The first six months of the 2011 Syrian uprising were characterized by a strikingly violent state response to protest. The Syrian army and security forces regularly shot into crowds of unarmed protesters (Slackman Reference Slackman2011), tortured and killed suspected dissidents after conducting house-to-house raids (Human Rights Watch 2011), and laid siege to neighborhoods for weeks at a time (Barout Reference Barout2012, 254). Longtime regime clients were not spared. Sunni Arab communities of tribal background in the country’s northeast, many of whose leaders had long maintained informal patronage relations with regime agents, faced intense state violence. Although the regime initially attempted to head off protests in the northeastern city of Dayr al-Zur by meeting with leaders of tribal confederations (al-Furat 2011), it sent tanks into the city’s streets and killed dozens when protests grew in size and scope (Darwish Reference Darwish2016, 17). Yet protests in some of that same region’s communities evoked a notably different response: protestors in Kurdish towns and cities voiced similar demands to other protests around the country but faced a far less violent state response. The regime used conciliatory tactics to deal with Kurdish protesters: meeting with leaders of protesting groups, directing protests away from public buildings and regime symbols, and leaving most protestors unharmed (Barout et al. Reference Barout, Bishara, al-Mustafa and Nahar2013, 103).

The Syrian regime’s differential response to similar forms of challenge in a single episode is a common feature of state repression strategies. The Algerian government, for example, granted cultural rights it long denied to Amazigh populations in 2016 after otherwise repressing popular dissent (Maddy-Weitzman Reference Maddy-Weitzman2022, 39). Similarly, Libya’s Qaddafi regime reached out to Amazigh community leaders to keep the Amazigh from joining their Arab neighbors in the 2011 rebellion while violently repressing protests among Arabs (Lacher Reference Lacher2020, 76–82). Research on state use of repression against challengers has developed theories of which states are more likely to use repression (Davenport Reference Davenport2007), the types of repression states use (Shen-Bayh Reference Shen-Bayh2018; Sullivan and Davenport Reference Sullivan and Davenport2018), how protesters respond to repression (Pearlman Reference Pearlman2013; Rasler Reference Rasler1996), and the nature of strategic interaction between the state and protesters (Pierskalla Reference Pierskalla2010; Ritter and Conrad Reference Ritter and Conrad2016). There has also been more focused research on why states repress some protests and not others (Bishara Reference Bishara2015; Lorentzen Reference Lorentzen2013) or arrest some dissenters and not others (Sullivan Reference Sullivan2016). Yet the question of why governments would repress some groups from the same antigovernment movement more harshly than others has received less attention in the repression literature.

To explain heterogeneous state responses to protest, we draw on literature concerning authoritarian institutions and the coalitional nature of revolutions. We contend that incumbent regimes exploit identity divisions to weaken and fragment challenger groups in order to survive episodes of revolution. States are likely to repress the most threatening of the groups coalescing to challenge their right to rule. By sparing other groups, incumbents can sow division within diffuse challenger coalitions, which are often united only by their dislike of the incumbent. Such violence sends a message not only to its physical targets but also to those spared the violence.

We test this logic of strategic repression by examining the incumbent regime’s response to the 2011 Syrian uprising, focusing on the ethnic identity difference between Arabs and Kurds. First, we present descriptive quantitative evidence on ethnic composition, protest incidence, and lethal state repression, showing that the Syrian regime used violence toward protesters differentially along ethnic lines. Then, to account for the endogenous selection of protesting towns into a greater likelihood of being targeted by the state, we fit a selection model that, in two stages, accounts for the likelihood of town-level state repression given the occurrence of protest in that town. The results show ethnicity-based differentiation of repression by the state. In the first months of the uprising, Kurdish towns were significantly less likely to face lethal repression than towns with majority-Sunni Arab populations, whereas Sunni Arab tribal towns faced rates of repression comparable to other Sunni Arab towns, despite having a lower propensity for protesting than nontribal Sunni Arab towns.

We substantiate the quantitative findings with a qualitative analysis of regime response, drawn from interviews and Arabic-language secondary literature. Initially, the interactions between the regime and protesters in both Kurdish and Sunni Arab communities of tribal background followed a similar pattern: protesters made national-level demands and the regime appealed to local elites to quell protests. However, when efforts to halt demonstrations failed, the regime only showed restraint toward protests in Kurdish areas, and especially in response to protests that made demands regarding the political and cultural rights of Kurds. This restraint, we argue, was aimed at convincing the Kurdish elite and wider public that Sunni Arab-dominated rule would be more unpalatable than the current ʿAlawi-dominated regime. In contrast, because regime clients of Sunni Arab tribal background in Syria’s northeast shared the Sunni Arab identity of protest leaders in other regions of Syria, the regime employed more lethal forms of repression against protesters from tribal communities.

Our analysis highlights the coalitional aspect of regime repression calculations. Building on recent work on how challenger coalitions factor into revolutionary success (e.g., Beissinger Reference Beissinger2022), we unpack the mechanisms through which identity-based targeting of repression in an ethnically diverse polity can fracture revolutionary coalitions. In doing so, we contribute to ongoing debates about how authoritarian regimes combine violent and nonviolent forms of control (Hassan, Mattingly, and Nugent Reference Hassan, Mattingly and Nugent2022, 169) and the interrelation of challenger violence, civilian support, and state repression/concessions (Braithwaite and Butcher Reference Braithwaite and Butcher2023; Dorff, Gallop, and Minhas Reference Dorff, Gallop and Minhas2023; Schubiger Reference Schubiger2023). Our findings have broad implications for research on how authoritarian regimes understand their challengers and deploy violence in confronting internal threats. Critically, we show that the deployment of state violence not only depends on timing, the level of force employed, or the location of protests but on who is protesting and what selective repression can do to the cohesion of revolutionary coalitions.

Strategic Repression of Ethnically Heterogeneous Challengers

Why do incumbent governments conduct harsher repression against some protesting groups? We contend that incumbents respond to the coalitional dynamics of revolutionary movements by focusing their repression away from less threatening groups and toward groups that constitute the greater threat to their rule, with the aim of splitting revolutionary movements.

A Coalitional View of Repression

Our argument builds on the scholarship of contemporary revolutions as phenomena brought on and sustained by “negative coalitions”: alliances that form when coalitions constructed by incumbent authorities break down and excluded social actors gather to challenge the regime (Dix Reference Dix1984). These coalitions are typically united by antipathy toward the incumbent, rather than by a shared vision for the country’s future (Beissinger Reference Beissinger2013); founded on mass gatherings in central urban spaces to force the resignation of prevailing political authorities (Beissinger Reference Beissinger2022, chap. 4); and subject to fragmentation either before, during, or after successful toppling of the incumbent regime (Clarke Reference Clarke2023).

An incumbent government facing a negative coalition calling for regime change has various options for containing the uprising. Before escalating to repression, incumbents are known to use clientelism (Chandra Reference Chandra2004), media messaging (Snyder and Ballentine Reference Snyder and Ballentine1996), and even the incitement of interethnic violence (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2004) as a way to fragment ethnically heterogeneous opposition coalitions. Along with fostering divisions, governments may also buy off opposition groups by offering them spoils (Weingast Reference Weingast1997) or positions in toothless legislatures (Lust-Okar Reference Lust-Okar2005) to prevent the emergence of a cohesive negative protest coalition.

But when these techniques fail and challenge persists, regimes often turn to violence. We focus on autocratic regimes because one of the most robust findings in the repression literature is that democracies are less likely to use violence to suppress challenge (Davenport Reference Davenport2007). Among autocracies, recent work has found that the severity of state repression varies and is related to ethnic coalition size (Hendrix and Salehyan Reference Hendrix and Salehyan2019), the presence of relatively autonomous civil society organizations (Berman Reference Berman2021), low levels of information about challengers (Xu Reference Xu2021), and very high or very low levels of inequality (Shadmehr Reference Shadmehr2014).

Targeting of subgroups within an episode of challenge has been given less explicit attention. The dominant assumption in the repression literature is that repression works by incapacitating its targets and deterring future challengers by altering their cost-benefit calculations (Przeworski Reference Przeworski2023, 981).Footnote 1 Yet mass repression may be too costly for regimes or may backfire by broadening support for the challenger (Rasler Reference Rasler1996). Moreover, regimes are aware that their use of violence has second-order effects on the composition of the challenger group, in addition to physically incapacitating or altering the payoffs to the whole coalition. For example, Rozenas (Reference Rozenas2020, 1271) shows how regimes target repression along a “cross-cutting cleavage,” weakening the grievance–behavior linkage and communicating the potential costs for participation to the population not being repressed. Whereas mass repression can persuade a large segment of the public to support the opposition, Davenport and Loyle (Reference Davenport and Loyle2012, 92) demonstrate how repression of a specific social group can stigmatize the group and “unify…societal opinion” in favor of the incumbent. An analogous dynamic has been identified in the intrastate war context. Specifically, regime violence fragments ties across diverse militant groups but hardens the resolve of individuals and smaller networks within those groups. Schubiger (Reference Schubiger2023) shows how not targeting parts of the challenger coalition leaves intact those higher-level network structures between neighborhood- or city-level leaders. These networks subsequently channel group members’ actions away from challenge.

The constraints that regimes face and the aforementioned examples of strategic targeting suggest there are more nuanced reasons for why regimes target specific subgroups within a broader challenger group than the extant repression literature has explored. We adapt the logics of revolutionary coalitions to authoritarian regimes ruling over diverse polities, developing a theory about how incumbents facing a negative coalition target violent repression.

Regime Threat Perception and Co-optation

Which groups within a negative coalition are most likely to be targeted by or spared state violence? We argue that incumbents target groups most threatening to their rule to hive other groups off from the challenger coalition.

How incumbents perceive threats has been a central concern of the repression literature since the advent of “mass threat” theories of authoritarian rule (Friedrich and Brzezinski Reference Friedrich and Brzezinski1965). Berman (Reference Berman2021) shows that the Moroccan government repressed challenge associated with independent civil society groups more harshly to channel dissent from autonomous social groups and toward “captured” corporatist organizations. Such repression prevents the rise of collective movements that bring pressure on the incumbent, which is fundamental to contemporary revolutionary movements (Beissinger Reference Beissinger2022).

Yet the independent organizations targeted in quasi-democratic and liberal autocratic settings are rare in fully authoritarian regimes. Incumbents view all such organizations as a threat and systematically block their development (Sullivan Reference Sullivan2016), in the Middle East (Diani and Moffat Reference Diani, Moffat, Alimi, Sela and Sznajder2016) and Syria (Pearlman Reference Pearlman2021) in particular. What, then, are the primary characteristics of a threatening group within a coalition challenging an authoritarian regime?

We posit that the most threatening groups in such settings are those that (1) are less likely to accept accommodation with the incumbent, (2) represent a larger share of the population, and (3) have a history of anti-regime mobilization. First, groups that seek to control the center and implement wholesale change to the economic or political system are less likely to accept compromise as a solution. Second, groups that comprise a large share of the population are likely to be more threatening because solidarity along group lines could bring large numbers out nationwide. Regimes are often aware of the threat from large groups and aim to draw distinctions within such populations, exemplified by divisions that incumbent regimes tried to stoke among Shiʿis in Baʿthi Iraq (Baram Reference Baram1997), Oromos in Ethiopia (Abbink Reference Abbink2006), and Sunni Arabs in Syria (Mazur Reference Mazur2021). Third, previous episodes of anti-regime mobilization indicate a willingness and capability among members of a group to mobilize. For this reason, multiple Arab regimes have targeted the Muslim Brotherhood (e.g., Egypt, Darwich Reference Darwich2017; Syria, Lefèvre Reference Lefèvre2013), and Ethiopia targeted Amhara-associated political groups (Abbink Reference Abbink2006).

The presence of a well-defined leadership, crucial to much work on mobilization and co-optation, cuts both ways. Structures like well-established diaspora organizations (Roth Reference Roth2015), clandestine networks (Sullivan Reference Sullivan2016), and elite backers more generally (Radnitz Reference Radnitz2010) could all fund within-country activity and establish a shadow governing apparatus to take over the central government following the incumbent’s ouster. Opposition leadership based in Iran helped stoke rebellion in Iraq during the 1991 uprising (Abdul-Jabar Reference Abdul-Jabar and Hazelton1994), and diasporic networks functioned similarly in the lead-up to the 2003 American invasion (Vanderbush Reference Vanderbush2014). By the same token, a well-defined leadership structure can constitute a basis for in-group policing (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin1996) on behalf of the incumbent. Ramazan Kadyrov, for example, performed in-group policing for the incumbent Russians in Chechnya (Littell Reference Littell2009). We thus analyze leadership mechanisms in terms of their component parts: their proven capacity and an inclination to mobilize members against the regime, which make repression more likely, and their ability to steer group members away from challenge, which makes repression less likely.

Ultimately, incumbent perceptions—and how those perceptions can be generalized throughout the population—rather than the reality of challenger group composition are central to incumbent decision-making. Thus, groups that played key roles in historical episodes of challenge may loom larger in incumbent calculations than the reality on the ground. In practice, challenger groups are typically heterogeneous initially, and the actors who come to dominate a challenging movement in its later, violent phases can be quite different from those who initiate it. Youth activists critical to early protests often become marginalized in the process of contention and in postrevolutionary ruling coalitions, as in Tunisia and Egypt after 2011 (see Clarke Reference Clarke2023). In Syria, both longtime opposition leaders and early protest organizers came from non-Sunni Arab backgrounds. Regime action altered protest composition and demands, because the aforementioned civic-minded activists were largely apprehended by regime raids. Leaders who persisted in the face of violence largely came from densely networked Sunni Arab communities (ʿAbd al-Rahman Reference ʿAbd al-Rahman2016; Bishara Reference Bishara2013).

The opposite of targeted repression is targeted concessions. Aware that challenger coalition members calculate the threat and opportunity entailed by their participation in a revolution (Goldstone and Tilly Reference Goldstone, Tilly, Aminzade, Goldstone, McAdam, Perry, Tarrow, Sewell and Tilly2001), incumbent regimes can take advantage and deploy concessions to break up coalitions (Rasler Reference Rasler1996). We argue that incumbents should thus target concessions to less threatening coalition members. Incumbents do so to manipulate group calculations and spur in-fighting through perceptions that the group receiving concessions will defect from the coalition (La Spada Reference La Spada2022, 4). The groups most likely to defect and thus be targeted by concessions are those with relatively moderate demands that are seeking autonomy from the central government, make up a relatively small percentage of the population, or have not historically challenged the incumbent.

Once concessions are made, what assurance do groups have that they will not be repressed? First, cooperation can become an equilibrium. As long as the nontargeted population does not engage in collective action, the incumbent is incentivized to continue not repressing (Rozenas Reference Rozenas2020, 1258). Continued nonrepression, in turn, promotes “in-group policing” to enforce the equilibrium and curtail dissent from within the group. Second, nontargeted groups may lack other options in a highly violent situation (Kalyvas and Kocher Reference Kalyvas and Kocher2007), making relative peace in the short term preferable to the risk of becoming a small party in a large multiparty civil war.

Group Identity Boundaries

We follow the broader repression literature in thinking about identity differences in terms of ethnicity (e.g. Hendrix and Salehyan Reference Hendrix and Salehyan2019; Rozenas Reference Rozenas2020). Our theoretical claims are therefore situated in the politics of ethnically heterogeneous societies with at least two politically relevant ethnic groups (see Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Bormann, Ruegger, Cederman, Hunziker and Girardin2015).

Yet the logic we spell out should apply to a far wider set of cases and types of identity boundaries. Frequently, identity-based targeting by state authorities occurs along other lines (Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín and Wood2017, 22), including party affiliation (Steele Reference Steele2011), trade union membership (Stillerman Reference Stillerman2006), class (Rozenas Reference Rozenas2020, 1257), and religious group membership (Darwich Reference Darwich2017).

The “groups” participating in a negative coalition are composed of individuals who form subsets of identity groups; not every person in a polity sharing those characteristics. Group members are thus often motivated by concerns to which their shared identity is irrelevant, such as political ideals, material self-interest, or revenge. Targeted repression is part of a struggle to impose a particular “vision of divisions” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1989), in which ethnicity could fragment the diverse segments of a negative coalition or be eclipsed by other divisions. This logic is consistent with work analyzing challenger–incumbent interaction (see Tilly Reference Tilly2008) and ethnicization of conflict (Brubaker and Laitin Reference Brubaker and Laitin1998; Hashemi and Postel Reference Hashemi and Postel2017). These strands of research highlight how the character of challenge develops through a series of challenger and regime moves and countermoves, rather than as a mechanical product of social group characteristics.

Precisely because the nature of challenger-incumbent interaction changes as the conflict evolves (Tilly Reference Tilly1998), we focus on a particular phase of conflict: state response to initial, mostly nonviolent challenge. The logic of challenger and incumbent action differs as the form and degree of state authority over territory vary (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006, 22), compelling researchers to focus on a specific phase of conflict (e.g., Christia Reference Christia2012). Although we believe the knock-on effects of the incumbent strategies we examine here are a fruitful avenue for future research, they are beyond the scope of the present theory and empirical analysis.

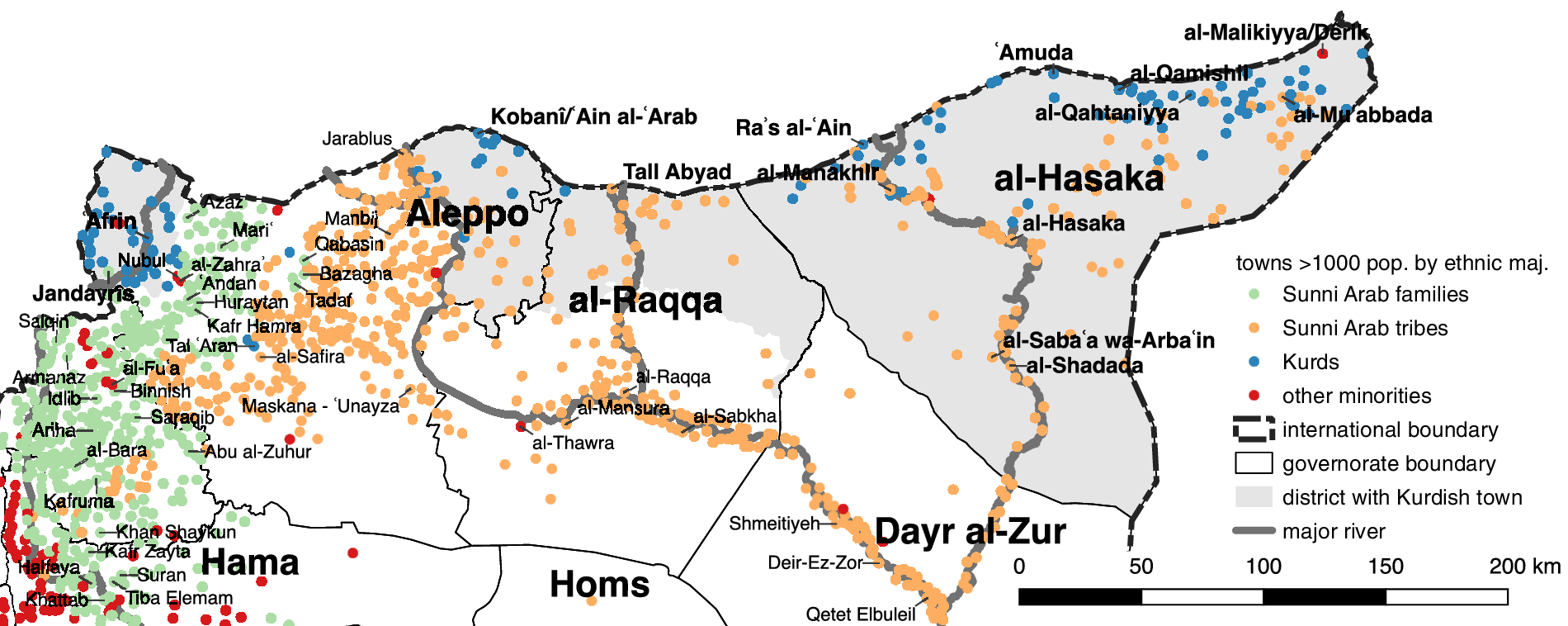

Repression during the 2011 Syrian Uprising

We test our argument by examining the Syrian government’s response to the early stages of the 2011 uprising. Syria at the time of the uprising fits the theory’s scope conditions. It is a multiethnic society that, in 2011, was ruled by an autocratic regime centered around the family and close associates of President Bashar al-Asad. Al-Asad belongs to the ʿAlawi ethnic group, which constitutes a small percentage of the Syrian population. Ethnic demographic data were not officially collected or publicized by the regime, but one prominent demographer of Syria, Youssef Courbage (Reference Courbage, Dupret, Ghazzal, Courbage and al Dbiyat2007, 189), estimated that 72% of the pre-2011 population was Sunni Arab, 10% ʿAlawi, 8% Kurdish, and the remaining 8% were members of other ethnic groups, including various Christian denominations, Druzes, Ismaʿilis, and Turkmans.Footnote 2 Areas of substantial Kurdish settlementFootnote 3 and the ethnic composition of large towns in and around Syria’s Northeast are presented in figure 1 and table 1.

Figure 1 Map of Towns and Majority Ethnic Identities in Syria’s Northeast Region

Table 1 Ethnic Composition of Towns in Syria’s Northeast Region

Sources: Syria Town database (Khaddour and Mazur Reference Khaddour and Mazur2018); 2004 census (Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics 2004).

Our understanding of identity in Syria is in line with the prevailing social-scientific understandings of ethnicity. Ethnic identities emerged historically, with shifting boundaries and varying salience, and they are thus ambiguous in some situations and largely irrelevant to others. Before the 2011 uprising, regional provenance and discrete social networks often took precedence over ethnic boundaries in navigating security checkpoints or accessing state resources (Khaddour and Mazur Reference Khaddour and Mazur2013). Moreover, neoliberal restructuring of the economy led to an increasing rate of intermarriage of Sunni elites and ʿAlawis close to political power (Terc Reference Terc2011). Yet these interactions and their increasing prominence in the lead-up to the 2011 uprising neither erased ethnic boundaries nor rendered them irrelevant for many Syrians. For instance, many Kurds were denied basic rights and excluded from regular access to state-controlled resources (Tejel Reference Tejel2009). The patchwork structure of ethnic boundaries thus set the stage for the instrumentalization of ethnicity by the regime.

We follow Wimmer (Reference Wimmer2013) in conceiving of religious differences, commonly described in the Levantine context as “sectarian,” as a subcategory of ethnic difference. Ethnicity also includes differences along linguistic or racial lines. Kurdish identity differs from these “sectarian” identities because most Kurds are Sunni Muslims but are differentiated from their Arab coreligionists by their native language and distinct cultural practices, such as dress, food, and celebrations. These differences could, in principle, motivate a separatist challenge. Nevertheless, Druze and ʿAlawi religious difference defined the only two ethno-states in Syria’s modern history, which were created under French Mandatory rule (Neep Reference Neep2026, chap. 4). In 2011, challengers from all ethnic backgrounds called for center-focused political change in the early phases of the Syrian uprising.

The uprising began with demonstrations in several cities in March 2011. Regime repression fueled protest throughout the country and greatly increased its frequency, turning isolated demonstrations into nationwide challenge. The majority of participants in the early protests, like the overall Syrian population, were Sunni Arabs. However, the protest movement that emerged in March 2011 consisted of members of all of Syria’s ethnic groups, and demonstrators overwhelmingly articulated demands focused on supraethnic political issues, including democratization and equal treatment of all Syrian citizens (Ismail Reference Ismail2011). Sustained regime repression during the summer of 2011 tilted the largely nonviolent demonstrations toward an armed response. Starting in summer 2011, challengers formed militias, loosely organized under the Free Syrian Army (FSA) umbrella (al-Haj Saleh Reference al-Haj Saleh2017, 78). These groups began to wrest peripheral areas around major cities from regime control in autumn 2011. By January 2012, rebels had fully expelled regime agents from the town of al-Zabadani in the Damascus periphery (Bishara Reference Bishara2013, 199).Footnote 4

As nonviolent protest morphed into civil war in 2011 and 2012, regime tactics and challenger response varied significantly. In the following section, we examine how the multiethnic coalition of challengers from the early, nonviolent phase of protest set the stage for the regime’s use of strategic repression, differentiated along ethnic lines. Our focus is on how repression of challengers differed across ethnicity from the baseline of Sunni Arabs, who formed the numerical core of the Syrian opposition at the outset of the uprising.

Descriptive Quantitative Analysis

As a first empirical step, we describe patterns of protest and repression during the first year of the Syrian uprising. We present these data at the level of the town (n = 5,204).Footnote 5

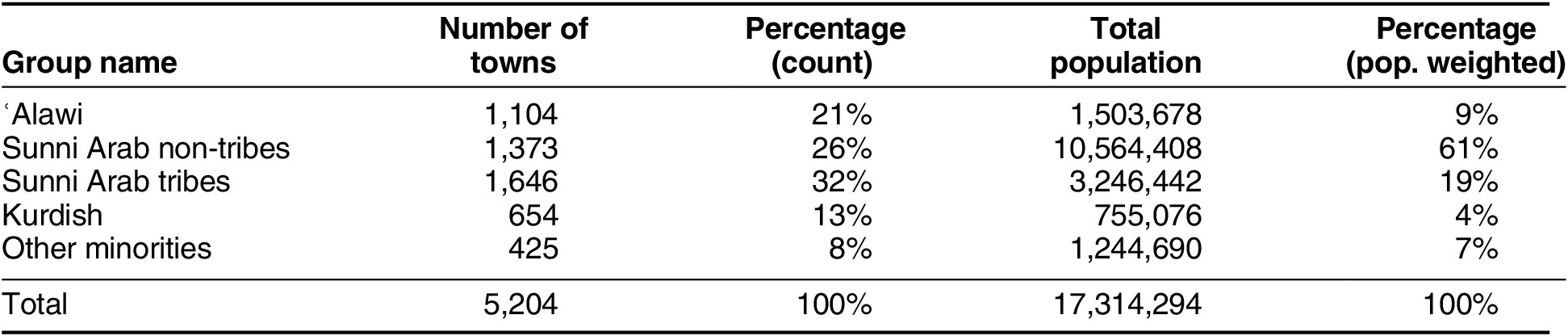

To measure lethal repression, we use data from Syria Tracker (Kass-Hout Reference Kass-Hout2016), an online database cataloging killings in the early stages of the Syrian uprising. Syria Tracker aggregates data from other online repositories and user reports and has been used in other academic studies of violence in Syria (e.g., De Juan and Bank Reference De Juan and Bank2015). It geolocates killings, allowing us to match them to our town-level data using GIS software.Footnote 6 Protest events are drawn from the Syrian Uprising Event Database (Mazur Reference Mazur2020), an event catalog based on a range of newspaper sources and coded at the town level. For ethnic identity, we use the Syria Town Database (Khaddour and Mazur Reference Khaddour and Mazur2018), which provides information about the ethnic composition of each town, including whether it was ethnically homogeneous and the identity of the majority ethnic group. We condense the many ethnic categories in the Syria Town Database into five, creating dichotomous variables for whether a majorityFootnote 7 of town residents were ʿAlawi, Kurdish, Sunni Arab, or from another minority ethnic group (e.g., Christians, Druzes, Ismaʿilis). We also distinguish between Sunni Arab populations with tribal lineage and those without this background. Those of tribal lineage historically had extended family structures and closer relations with state authorities that might depress their participation in contentious challenge or facilitate state conciliation (Al Mashhour Reference Al Mashhour2017, 23; Chatty Reference Chatty2010, 43). Table 2 presents the distribution of towns according to ethnic majority from the Syria Town Database (Khaddour and Mazur, Reference Khaddour and Mazur2018).

Table 2 Ethnic Composition of Syrian Towns

Source: Khaddour and Mazur (Reference Khaddour and Mazur2018).

The core group within the challenger coalition in the Syrian uprising was Sunni Arabs, so we expect that repression would be disproportionately focused on Sunni Arab towns. We focus in this initial descriptive exercise on Kurdish- and Sunni Arab tribal-majority towns because they are spatially proximate to one another, concentrated in Syria’s northeast region, and experienced similar levels of relative state neglect.

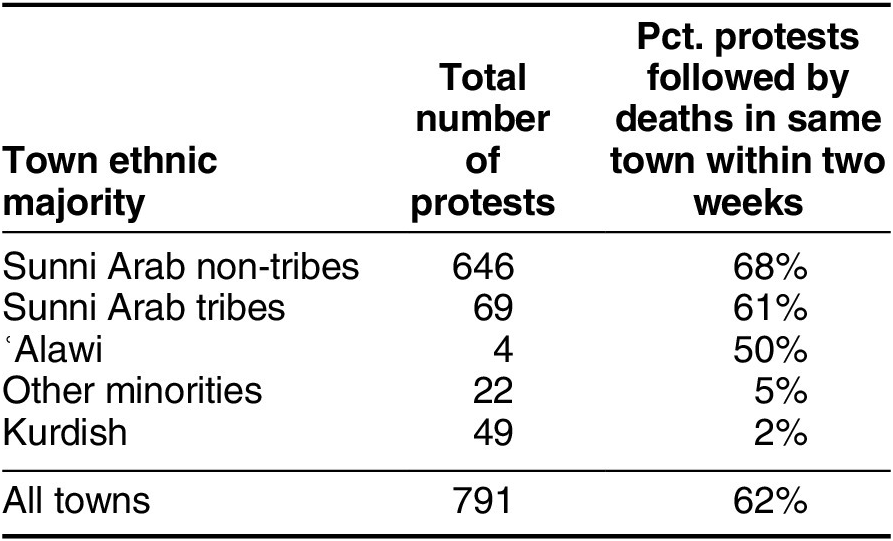

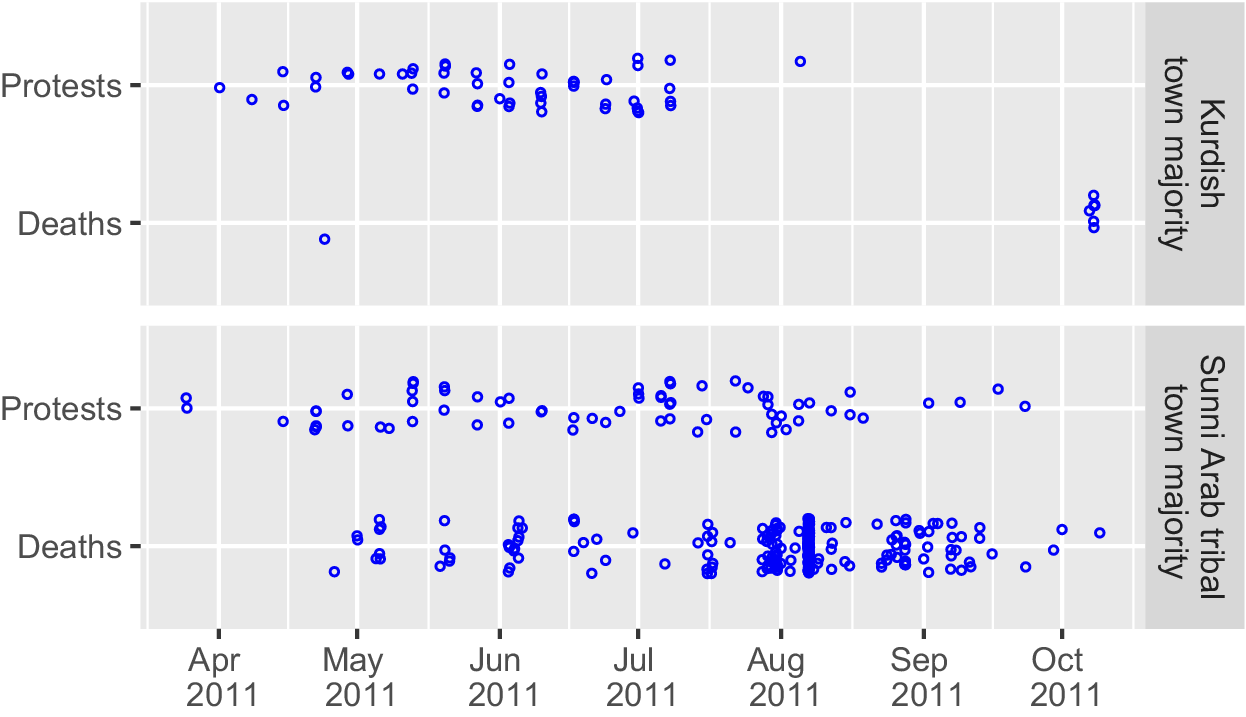

Because repression decisions are bound up in challenger actions (Lichbach Reference Lichbach1987; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2022), we examine patterns of challenge and repression simultaneously. Figure 1 plots incidences of protest and challenger fatalities, demonstrating a clear pattern: Kurdish locales experienced a considerable amount of initial protest, like those in Sunni Arab tribal neighboring towns, but faced comparably little repression. The same trend is borne out when we examine state response to protest over time within a locale. Table 3 reports a count of protests by town ethnic majority, as well as the percentage of those protests followed by deaths in the same town two weeks after the protest in question occurred.Footnote 8 Sunni Arab tribal-majority towns experienced deaths in the two weeks following protests 61% of the time. In contrast, only 1 of the 50 protests in majority Kurdish towns between March and October was followed by a challenger death in the next two weeks.

Table 3 Protest and Repression by Town Ethnic Majority through October 11, 2011

Selection Model and Instrumental Variables

The previous section describes the clear ethnic variation visible in patterns of dissent and repression. Towns with Kurdish and Sunni Arab tribal majorities experienced about the same number of protests between March and October 2011, but towns with Sunni Arab tribal majorities were targeted with much more repression. Both figure 2 and table 3 suggest that protest onset changes the regime calculus in carrying out repression. Specifically, the regime appears to respond to protests with repression based on the ethnic characteristics of the location where the protest is taking place. Nevertheless, figure 2 and table 3 are descriptive, and other factors might influence the relationship between town ethnic identity and state repression, most notably the choice to protest by opposition organizers. As such, we turn to inferential statistics to establish the role of town ethnicity in regime repression.

Figure 2 Distribution of Protests and Repression from March to October 2011 in Majority Kurdish and Sunni Arab Tribal Towns

The simplest inferential statistical option is a single-stage linear model that predicts repression, controlling for protest.Footnote 9 Unfortunately, such a model does not sufficiently capture the differential effects of town ethnicity on both protest incidence and regime repression. The choice to protest changes not only the likelihood of regime repression but also the effect of a town’s majority ethnicity on repression. This problem is known as endogenous selection (see Lewbel Reference Lewbel2007). Although a simple solution to endogenous selection could be to interact protest and town majority ethnicity, as we do in appendix 2.1, such a design remains prone to inconsistent estimates (Greene, Reference Greene2017, 788).

To account for endogenous selection, we employ a two-stage model first proposed by Heckman (Reference Heckman1979). The Heckman selection model is concerned with outcome variables whose occurrence is influenced by a nonrandom observable process. Heckman’s (Reference Heckman1979) classic example is that hours worked by women can only be observed among women who enter the labor force. Thus, factors impelling labor market participation need to be accounted for when measuring hours worked. Heckman (Reference Heckman1990) extends the selection model to self-selection (see also Greene Reference Greene2017, 787–88) into an otherwise completely observed set of outcomes: the choice of joining a labor union and wages. As in Heckman (Reference Heckman1979), the differential role of factors predicting union membership needs to be accounted for when predicting wages, which are observed for both union and non-union workers. Our case involves similar self-selection because the differential role of factors predicting protestFootnote 10 must be accounted for to properly predict changes in our outcome of interest: repression by the Asad regime.

For our selection model to be unbiased, we require an instrumental variable in the first stage. Despite the self-selection observed on the part of protest organizers in staging protests, we can isolate some “as-if-random” assignment of protest through an instrumental variable that exogenously predicts some first-stage outcomes independently of second-stage errors (Cameron and Trivedi Reference Cameron and Trivedi2005). An instrument must satisfy three assumptions: independence from the unobserved covariates affecting the outcome, relevance to the covariate of interest, and effect on the outcome through only the covariate of interest, also known as the exclusion restriction (Baiocchi, Cheng, and Small, Reference Baiocchi, Cheng and Small2014, 2300).

The instrumental variable we use to isolate the “as-if-random” effect of protest on repression is the deviation in temperature and precipitation from 2006 to 2010 from the average of the preceding 105-year span. To measure variation in temperature and precipitation, we use temperature and precipitation data from the Climatic Research Unit (CRU TS 3.22; Harris et al. Reference Harris, Jones, Osborn and Lister2014; Mitchell and Jones Reference Mitchell and Jones2005). These data provide monthly measures of temperature and precipitation, gridded on 0.5 x 0.5 degree squares. We aggregate these measures into two averages (2006–10 and 1900–2005) and take the difference to create a measure of varying meteorological drought impact during the drought period. Much like our measure of repression, we calculate borders 5 km away from town borders and take precipitation and temperature averages within those extended areas.Footnote 11

We believe our instrument satisfies the relevance assumption, because lower temperature deviation and higher precipitation conditional on lower temperature deviation have been found to be associated with more protest (Ash and Obradovich Reference Ash and Obradovich2020). Put differently, greater exposure to meteorological drought, through either below-average precipitation, higher-than-average temperatures, or higher-than-average temperatures conditional on below-average precipitation, should be negatively associated with protests for the assumption of relevance to be satisfied. We confirm that the relevance assumption is satisfied in appendix 5.1. One possible reason for the association between temperature deviation and protest is that individuals in towns affected by drought migrated to places that did not experience drought, reducing the set of potential challengers in drought-afflicted locales and clustering migrants in receiving areas more likely to engage in protest.Footnote 12

We do not have any reason to believe that varying exposure to the drought would have affected the likelihood of the state to carry out lethal repression other than because that town staged a protest. If there were such an association, the assumption of independence from unobserved covariates would be violated, and our instrumental variable would not be valid. In appendix 5.2, we confirm that drought is uncorrelated with the error term of a single-stage linear model predicting repression.Footnote 13 Although appendix 5.3 shows some association between weather station location and stronger regime influence after 1998, there is no association between ethnicity and weather station location, suggesting that there is no systematic bias in weather station placement after 1998 based on our model covariates of interest.

Our instrumental variables must satisfy one final assumption—that they only affect repression, our outcome of interest, through protest. Mellon (Reference Mellon2024) presents a challenge for using weather as an instrumental variable based on violations of this assumption, finding numerous such violations across a multitude of studies. Nevertheless, specifications using “rainfall to estimate the effect of protests” (Mellon Reference Mellon2024, 13), specifically those of Collins and Margo (Reference Collins and Margo2007), do not violate the exclusion restriction even if the instruments are simulated to be perfectly correlated with the outcome of interest. Because our design is similar to that of Collins and Margo (Reference Collins and Margo2007), we do not expect our instrument to directly correlate with repression or for such a correlation to hypothetically bias our findings.

Temperature and precipitation deviations thus appear to be valid instruments in the Syrian case, ensuring that our selection model eliminates endogenous selection.

Operationalization of Outcome, Selection, and Ethnicity Variables

Our dependent variable is the town-level occurrence of lethal repression during the first six months of the Syrian uprising. We match the Syria Tracker repression data to our town units of analysis by spatially joining this data with maps of the built-up area of all Syrian towns, drawn from the United Nations Cartographic Section (UNCS; 2017), and counting the number of fatalities occurring in each during the period of investigation. Because the coordinates georeferencing repression data may not fall exactly within the built-up areas, we extend the borders around the defined built-up area boundaries to count all killings that take place within those extended areas to capture our dependent variable. We specify these new boundaries in two ways: 5 km past the actual boundaries to account for false negatives and 1 km past the actual boundaries to prevent double counting.

We operationalize lethal repression both dichotomously and as a count. The dichotomous variable is coded as zero if no killings are recorded as taking place within either 1 km or 5 km of a town, and one if any killings took place in that area within our period of interest. The count variable reports the number of killings that took place within either 1 or 5 km of a town during a specified period.

For ethnicity, we employ the categories from the Syria Town Database, coding towns according to their ethnic majority.Footnote 14 The reference category in our statistical analysis is nontribal Sunni Arab towns.

We cluster standard errors at the second administrative level, the district, assuming spatial autocorrelation within every Syrian district. We use an OLS selection model, rather than a probit-probit model, to gain efficiency in models with our binary measure of repression.Footnote 15 We use a two-stage Heckman Poisson model derived from Terza (Reference Terza1998) to analyze a count of deaths within either 1 or 5 km of a town.Footnote 16 The Heckman OLS and Heckman Poisson regression models are otherwise identical.

Statistical Findings

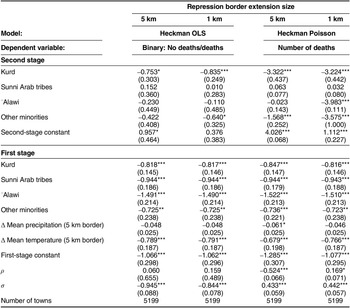

Table 4 presents our findings, using October 11, 2011, as the cutoff and 5 km and 1 km extensions of town borders to calculate the dependent variable. We fit both traditional Heckman selection models and the Heckman Poisson model.Footnote 17

Table 4 Heckman Two-step Selection Model of Deaths up to October 2011 (binary)

Note: OLS models include governorate-level fixed effects. All models cluster standard levels at the second administrative level. Sunni Arab non-tribal majority towns are the reference category.

*p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Cumulatively the results suggest that, taking into account the heterogeneous likelihood of towns to protest, towns with a Kurdish majority were significantly less likely than Sunni Arab tribal towns to experience repression and more likely to have fewer deaths as a result of repression. Towns with a Sunni Arab tribal majority were, however, no more likely than towns with a Sunni Arab nontribal majority to experience repression or to have fewer deaths before October 11, 2011. In appendix 10, we find that towns with substantial populations of both Kurds and Sunni Arab tribes also experienced significantly less repression, suggesting the regime went out of its way not to repress Kurdish population centers before October 11, 2011. There are also similar, albeit inconsistent, results for towns with majorities of small ethnic groups, consistent with findings that the Syrian regime made an effort to quell dissent among ethnic minority groups without using lethal repression (e.g., Ezzi Reference Ezzi and Stolleis2015). We examine selective nonlethal repression toward the Druze in al-Suwaydaʾ Governorate in appendix 8. In appendix 9, we find that a town’s population and majority ethnic group have no joint effect on repression.

Our first-stage results on a town’s propensity to have a protest before October 11, 2011, confirm the relevance of our instruments. Lower deviations in temperature from the pre-2006 average are significant predictors of protest, consistent with Ash and Obradovich’s (Reference Ash and Obradovich2020) findings. As such, protests occurred in areas less exposed to Syria’s preconflict drought. The first-stage findings also suggest the utility of using a selection model. Towns with majorities among the ethnic groups we examine,—including ʿAlawis, Kurds, Sunni Arab tribes, and others—were on average less likely to protest than towns with Sunni Arab nontribal majorities. Nevertheless, only some groups faced relatively less lethal repression by the incumbent.Footnote 18

The quantitative findings are consistent with our theoretical expectations. The Kurdish component of the challenger coalition, which we argue was less threatening to the incumbent, was subject to less repression. This finding stands even after addressing the endogenous selection of protesting towns and is robust to the inclusion of a range of control variables and alternate specifications. Nevertheless, our statistical findings cannot tell us why the regime acted as it did. For that explanation, we turn to a qualitative study of what led to differential patterns of repression toward Kurds and Sunni Arab tribes.

An In-depth Look at Syria’s Northeast

The initial demonstrations in northeastern Syria, where the majority of Kurds and Sunni Arabs of tribal background reside, could hardly be told apart by their participants’ ethnicity alone. Protests were nonviolent and staged by primarily young, educated people living in cities and large towns, who were calling for democratic political reforms and an end to regime repression. The regime initially responded to these protests by reaching out to local notables of both ethnic groups. However, when this failed to halt the protests, the regime acted with restraint toward Kurds while repressing Sunni Arabs in the northeast with the same ferocity as other Sunni Arabs.

This differential use of repression is best understood through the lens of incumbent regime threat perception and strategic action to hive Kurds off from the broader uprising. Although we lack access to the internal calculations of regime members, we argue that Sunni Arab challengers were perceived by the regime as the greatest threat and thus became its primary target for violent repression. Sunni Arabs fulfill the conditions we posit for what makes a given group a threat: unwillingness to accept accommodation with the incumbent, constituting a large share of the population, and a history of violent anti-regime activity. Kurds constituted a smaller threat to the regime on all these accounts. Indeed, the one effective political institution for either group in the region, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD), was both more open to conciliation and capable of disciplining many Kurdish would-be challengers.

We substantiate these claims by sketching historical state–society relations in Syria’s northeast and then examining the sequence through which protests among members of each group and divergent state responses unfolded. We build on English-language reporting and secondary sources, supplementing them with evidence from interviews and Arabic-language primary and secondary sources.Footnote 19 These materials provide ground-level evidence on the modalities through which the regime and PYD directed Kurdish challenge away from national demands and the specific language and symbols the regime used to communicate its conciliatory stance to Kurds.

State–Society Relations and the Bases of Regime Threat Perception

Kurds suffered cultural and political discrimination throughout Baʿth Party rule. A highly politicized census in the 1960s left hundreds of thousands of Kurds stateless. The regime also suppressed Kurdish cultural expression and took a range of measures to limit Kurdish economic activity, including the infamous Law 49, which banned property sales near the border (Ababsa Reference Ababsa, Hinnebusch and Zintl2015, 216; Kurdwatch 2010). Despite this extensive discrimination—and in part due to severe repression of its political organization—there was no major violent Kurdish resistance to the Baʿth. The largest contentious episode in Kurdish areas occurred in March 2004, triggered by taunting at a soccer match in al-Qamishli. Protests in al-Qamishli escalated to exchanges between challengers and regime agents that killed at least seven people and led to further protests and state repression in all of Syria’s northeastern cities with a substantial Kurdish population, as well as Damascus and Aleppo. The regime responded to the protests brutally, killing 43 people before the uprising was suppressed (Tejel Reference Tejel2009, 108).

Sunni Arabs, by contrast, faced no explicit cultural prohibitions from the regime, but were generally excluded from its extensive patronage system and were subject to its arbitrary violence in a way that no group-specific concessions could overcome. The regime shared Sunni Arab Syrians’ Arabic linguistic identity and, nominally, their religious identity.Footnote 20 Yet informal discrimination was widespread, with state employment and other forms of patronage bestowed on members of al-Asad family networks disproportionately comprised of their coreligionists (Mazur Reference Mazur2021, chap. 3). Moreover, Sunni Arabs had a history of more sustained and violent anti-regime activism. The Islamist insurgency of the late 1970s and early 1980s—composed overwhelmingly of Sunni Arabs and culminating in al-Asad regime’s massacre in the city of Hama—was the touchstone societal threat to the regime (Lefèvre Reference Lefèvre2013). Although Sunni Arabs in the northeast engaged in this resistance to a far lesser extent than those in cities like Hama and Aleppo, their shared ethnic identity made them appear to be a threat. This perceived threat would prove a self-fulfilling prophecy in 2011 following repression of protests in other parts of the country and regime violence against Sunni Arabs in the northeast.

In the decades before 2011, the regime made informal, selective alliances with segments of both Kurdish and Sunni Arab tribal society in ways that provided some access to the state, although it was limited and inconsistent. A range of Kurdish political parties emerged in the Baʿth period, and members of these parties frequently acted as intermediaries between the state and Kurdish individuals (Allsopp Reference Allsopp2014, 145–48). The parties were heavily intertwined with traditional leaders; as a Kurdish lawyer told Harriet Allsopp, “to know the parties, one must know the families” (43). Because leaders of these parties were not elected by their members and did not have institutional positions in the state that might provide them resources to distribute to constituents, their power came primarily from their role as mediators, whether in intracommunity disputes or with the state.

The Kurdish parties’ accommodation with the regime limited their ability to develop robust institutional structures. Mustafa Jumaʿa, former head of the Azadî party, recalled a 2009 demonstration by members of all major Kurdish parties in front of the People’s Assembly building in Damascus, demanding relief from Law 49. He and the other Kurdish party leaders present were arrested for around 12 hours, gaining release when a representative of the Republican Palace came to inform them that “Mister President (sayyid al-raʾis)” was releasing them.Footnote 21 Detention and release in this manner were intended to deliver a message: the regime regularly detained people without reason for years and treated them with arbitrary and severe violence, so the fact that these leaders were quickly released, and at the whim of “Mister President,” communicated both regime restraint toward the Kurdish leaders and the sharp limits it placed on associational life.

For decades, the Turkey-based Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) was the sole institutionalized group in the northeast that was tolerated by the Syrian regime. The PKK sought to carve out a Kurdish state from southeastern Turkey and was allowed a presence in Syria and in Syrian-controlled areas of Lebanon by the Syrian regime to put pressure on Turkey in the 1980s. PKK founder Abdullah Öcalan, in return, limited his claims for Kurdish self-determination to Turkey, even though the party recruited heavily from among Syrian Kurds (McDowall Reference McDowall2004, 479). In 1998, the threat of a Turkish invasion to pursue PKK leaders and the prospect of bilateral economic agreements convinced the Syrian regime to expel Öcalan and ban the PKK (Tol Reference Tol2012). A small offshoot of the party re-formed in Syria in 2003 as the Democratic Union Party (PYD), comprised of Syrian Kurds. PYD leaders sought refuge in and received training at PKK headquarters in the Qandil Mountains of northern Iraq (International Crisis Group 2013, 22). Eventually, the PYD would play a crucial role in making Kurds amenable to regime conciliation.

The relationship between the Syrian regime and Sunni Arabs of tribal background in the northeast had the same general qualities as that with Kurds (excepting the PKK/PYD), characterized by informal relations to local leaders with a limit on institutionalized activity. However, these relations were more consistent and conciliatory. Many tribal privileges that predated the modern Syrian state were revoked in 1956, and early Baʿthist leaders denounced tribes as retrograde (Batatu Reference Batatu1999, 23). But Hafiz al-Asad’s government moderated those policies (Chatty Reference Chatty2010), establishing a mutually beneficial relationship through which some tribal leaders received status and material benefits in exchange for ensuring their populations’ compliance. Tribal networks were instrumental in ensuring that the Muslim Brotherhood insurgency of the late 1970s and early 1980s did not gain a foothold in the northeast (Rae Reference Rae1999, 221). In exchange, tribal leaders were given some autonomy to control local society and a degree of formal recognition, a practice exemplified by Diyab al-Mashi, head of a clan, who served in Syria’s parliament from 1955 until he died in 2009.

To sum up, on the eve of the uprising, the Syrian regime had weakened all institutional structures in the northeast, save the remnants of the PKK that it had expelled a decade earlier, and maintained its discriminatory policies against Kurds. This treatment, paradoxically, created grievances that would make Kurd-specific regime concessions appealing to many Kurds. Sunni Arabs of tribal background were, in general, given better, albeit still meager and arbitrary, access to state-controlled resources than Kurds. Nevertheless, they shared an ethnic identity with the Sunni Arab populations throughout the rest of the country, which had a history of violent resistance along ethnic lines. These conditions set the stage for regime calculations about which populations constituted the greatest threat and held the greatest potential for hiving off from the uprising.

Shared Claims and Modalities of Protest

During the Syrian uprising’s first months, the level of contention in Syria’s northeast did not approach that of the country’s largest cities, in which tens of thousands regularly poured into the streets. Yet committed groups of challengers, often in the thousands, regularly massed in Kurdish- and Sunni Arab-majority cities and large towns alike (Barout et al. Reference Barout, Bishara, al-Mustafa and Nahar2013, 102). In their size and claims presented, the protests happening in Sunni Arab and Kurdish towns of the region were virtually indistinguishable.

Protests began in cities with large Kurdish populations—al-Qamishli, ʿAmuda, al-Hasaka, and Kobanî/ʿAin al-ʿArabFootnote 22—on April 1, 2011, just one week after the first protests in southern Darʿa (Kurdwatch 2011; Najjar Reference Najjar2017, 207, 229). They continued in these cities and spread to smaller Kurdish-majority locales in the following months. These protests were organized by local coordinating committees (LCCs)—networks of educated youths who, like protest organizers in the rest of the country, were outside the framework of established political organizations (Barout Reference Barout2012, 102). LCCs in Kurdish areas boycotted the Kurdish National Council (KNC), a body established by Kurdish parties to represent Kurdish interests during the uprising (Kurdwatch 2012a). Challengers demanded rights for all Syrians, the fall of the regime, and freedom for all political prisoners. Demonstrators displayed only Syrian flags, and few made explicit demands for recognition of Kurdish identity or cultural or political rights (Kurdwatch 2011).

In Sunni Arab areas, a similar dynamic was at play. The cities of Dayr al-Zur, al-Mayadin, and al-Bukamal were characterized by slowly escalating, mostly nonviolent protests that began on March 25, 2011, and continued weekly, intensifying during April and May. Participants made demands similar to those in Kurdish-majority cities and the rest of the country, focused on political reforms at the center (Barout et al. Reference Barout, Bishara, al-Mustafa and Nahar2013, 120, 128). The primary movers of these demonstrations were educated, young residents who also organized into LCCs and stressed the political nature of their participation (ʿAbd al-Rahman Reference ʿAbd al-Rahman2016; Al Mashhour Reference Al Mashhour2017, 26).

The regime initially dealt with both Kurdish and Sunni Arab communities of Syria’s northeast using relatively conciliatory tactics. Security forces typically arrested several demonstrators and urged others to go home (ʿAllawi Reference ʿAllawi2016, 8; Darwish Reference Darwish2016). The regime also attempted to woo the region’s customary leaders. On April 5, 2011, al-Asad hosted an informal meeting with 33 traditional local leaders from the region, of whom 18 were Kurdish, 12 were Sunni Arab, and 3 were Christian. An additional five representatives of Kurdish political parties were invited by the regime but declined to attend (Allsopp Reference Allsopp2014, 142; Kurdwatch 2011).

Demonstrators in both Kurdish and Sunni Arab locales initially rejected regime entreaties. In response to offers to Kurdish party leaders, challengers in several Kurdish cities held vigils and demonstrations with slogans rejecting negotiation and seeking the overthrow of the regime (Kurdwatch 2011). Protesters in Sunni Arab tribal Dayr al-Zur chanted, “Where’s the sense of honor, oh Nawaf? (wayn al-nakhwa, ya Nawaf?),” invoking a tribal concept in an attempt to get Nawaf al-Bashir, the head of a large tribe, to join the uprising (Al Mashhour Reference Al Mashhour2017, 26).

A Differentiated Regime Response

Facing resistance from demonstrators in both Kurdish and Sunni Arab communities in the northeast, the regime began to adopt vastly different strategies toward challengers from the two ethnic groups. In dealing with Kurdish demonstrators, the regime mixed conciliation, co-optation, and very light repression. By contrast, it made no ethnic–group-specific concessions and treated growing demonstrations with violence in Sunni Arab-majority locales. This differential treatment pushed challenge along divergent trajectories: contention in Kurdish areas remained nonviolent and came to focus on Kurdish-specific reforms, rather than the fall of the regime, whereas challenge in Sunni Arab areas became increasingly violent and aimed at the overthrow of the regime—following the trend in Sunni Arab localities in the rest of Syria.

The Syrian regime’s differentiated repression strategy is consistent with the incumbent repression calculations we posit. Major segments of the Kurdish population were amenable to conciliation, their demands were relatively easy for the regime to satisfy, and there existed a willing organizational structure capable of policing group members. With Sunni Arabs of tribal background, neither an equivalent in-group policing organization nor a set of ethnically targeted concessions were available to the regime.

The specific techniques the regime used to address contention among Kurdish populations are consistent with the hypothesized mechanisms. Specifically, the regime (1) made concessions on issues related to Kurdish nationality, (2) targeted repression against nationally focused demonstrations while tolerating protests advancing Kurdish-specific claims, and (3) empowered the PYD, a previously banned Kurdish political organization, to prevent demonstrators from focusing on national issues. This strategy proved effective, and the tens of thousands of Kurds who took to the streets in autumn 2011 focused their demands almost entirely on Kurdish issues and did not call for the fall of the regime. By contrast, violence meted out against Sunni Arabs in other parts of the country became a self-fulfilling prophecy that pushed many previously ambivalent Sunni Arab populations of the northeast firmly to the side of the uprising.

The regime’s first major concession to address long-standing Kurdish grievances came on April 1, 2011, when President Bashar al-Asad promised to investigate the “1962 statistical problem in al-Hasaka,” the census that left hundreds of thousands of Kurds stateless. In the following weeks, the regime announced pathways to naturalization for registered stateless Kurds and an easing of procedures for unregistered Kurds (Kurdwatch 2011). The regime also allowed the first officially sanctioned Nowruz celebration in a prominent Damascus square, covered it in the official media, and eased restrictions on property sales in border areas (Barout Reference Barout2012, 101–2; Kurdwatch 2011).

Police also exercised restraint in dealing with Kurdish protests. Authorities tolerated nonviolent demonstrations and enforced red lines with far softer tactics than in Sunni Arab areas, leaning on local notables and party members to act as intermediaries. When protesters in the Kurdish-majority city of Dêrik/al-Malikiyya attempted to pull down a statue of Hafiz al-Asad, local security chiefs asked members of Kurdish political parties and local notables to restrain the demonstrators. The intermediaries complied and diverted the protesters. A similar sequence of events occurred in al-Qamishli: after demonstrators attacked security forces, intermediaries again dispersed challengers to prevent escalation.Footnote 23 Regime forces did, however, respond forcefully to protests in Kurdish areas that made national demands. In the city of ʿAfrin, a demonstration using national slogans was stormed by security forces who beat and arrested participants, whereas a parallel demonstration by a Kurdish political party highlighting demands for Kurdish cultural rights was not repressed (Kurdwatch 2011).

Finally, the Syrian regime attempted to direct Kurdish challenge toward more explicitly ethnic claims by co-opting Kurdish leaders. Casting a wide net to attract Kurdish support, the regime’s initial efforts were mostly rebuffed by parties such as the Kurdish Democratic Party-Syria and Yekiti, whose leaders repeatedly declined offers to engage in a dialogue with President al-Asad.Footnote 24 One Kurdish intellectual figure and former party activist, however, related to us that he did accept the invitation to meet with the president. During this meeting, our interlocutor told us, al-Asad spelled out how an alternative political regime might be worse for Kurds, saying, “We are better for you than the Muslim Brotherhood.”Footnote 25

The PYD was more receptive to regime entreaties, exploiting regime tolerance of its activity in northern Syria to increase its following among Kurds and to repress protests making national demands.Footnote 26 The October 2011 killing of prominent Kurdish politician Mishʿal Tammu represented a turning point. Tammu, the leader of the Kurdish Future Movement political party, emphasized national rather than Kurdish demands, and members of his party accused both the regime and PYD of having a part in his killing (Kurdwatch 2012c). However, at his funeral, attended by all major Kurdish parties in al-Qamishli, the signs featured slogans that overwhelmingly concerned Kurdish issues (Barout Reference Barout2012, 104). The PYD demonstrations in the months that followed had only Kurdish national and PYD flags and slogans in support of Öcalan or a “free Kurdistan.” None explicitly opposed the regime or called for Kurdish independence.

Moreover, the PYD worked proactively to stop national-level claims-making among Kurds. Kurdish activists who formed the LCCs, which were crucial to early demonstrations, were pressured by the PYD and other Kurdish parties to direct their demands toward Kurdish-specific issues. To disrupt protests making national-level claims, PYD members marched in the opposite direction through the middle of those demonstrations. The PYD also held their own protests on Sundays, rather than on Fridays, which was the standard day for uprising demonstrations, and its protests limited their demands to Kurdish rights.Footnote 27 Some LCCs in Kurdish areas began to officially participate in the KNC, and LCC members who resisted this pressure were intimidated and marginalized. One such activist, ʿAbd al-Salam ʿUthman, was abducted by PKK members in August 2011 and forced into exile in Germany (Kurdwatch 2012a). On February 3, 2012, members of the PYD attacked a demonstration started by the Azadî party in ʿAfrin with clubs and knives, injuring more than 60 participants. Demonstrators chanted “azadî (‘freedom’ in Kurdish),” while PYD members raised PYD flags and chanted in response, “ʿAfrin is the city of martyrs; supporters of Erdoğan and Barzani have no business here.” Security forces looked on while the confrontation escalated to violence (Kurdwatch 2012b; 2012c). This regime’s delegation of responsibility for security to the PYD culminated in the total withdrawal of military and security forces from large swathes of the northeast in July 2012, effectively allowing PYD forces to control most Kurdish-majority towns and cities in that area (Allsopp Reference Allsopp2014, 208; International Crisis Group 2014, 9).

In contrast to its policy of restraint toward Kurds, the regime met Sunni Arab challenge with a high level of violence. Once initial outreach to local notables failed in Dayr al-Zur, for example, the regime dispersed demonstrators on May 6, 2011, by firing into a crowd, killing four. Protests in response drew tens of thousands in subsequent months (Bishara Reference Bishara2013, 152; Darwish Reference Darwish2016, 12). This escalation of protest occasioned an even stronger response by official regime agents, who began raids on contentious neighborhoods. Protesters set up checkpoints to prevent security raids and began carrying sticks, knives, and light arms in the name of “protecting the revolution.” During the week following a massive protest on July 22, 2011, repression killed six demonstrators, and challengers engaged in their first sustained clashes with regime agents in Dayr al-Zur city. In response, the regime sent tanks into the streets, shelled several neighborhoods, and laid siege to other neighborhoods for six days. This episode killed dozens of residents. Similar regime raids and the establishment of checkpoints followed in other major northeastern Sunni Arab cities and several smaller towns. Repression pushed less educated, more economically deprived residents, particularly in the peripheral towns and villages, into the uprising. Armed challengers began to attack checkpoints, limiting regime security and police forces’ ability to operate in the countryside. By the end of the year, organized FSA brigades were increasingly common, and the army had moved in to confront these armed groups (ʿAbd al-Rahman Reference ʿAbd al-Rahman2016; Al Mashhour Reference Al Mashhour2017, 31; ʿAllawi Reference ʿAllawi2016; Darwish Reference Darwish2016, 17).

Accounting for Differential Treatment

Why did the regime take this violent tack with Sunni Arabs in the northeast while it assiduously avoided violence in dealing with Kurds in the region? First, the likelihood that Sunni Arab communities would accept offers of accommodation was far lower. Cultural and ethnically specific concessions, key pillars of its strategy of restraint with Kurds, were unavailable to the regime in its dealings with Sunni Arabs because there was no cosmetic policy change that could address the latter’s primary grievance: exclusive and arbitrarily violent rule. Similarly, the likelihood that a Sunni Arab government would replace al-Asad’s regime did not pose the same threat to Sunni Arabs of tribal background that it did for Kurds.

Second, regime interactions with Sunni Arab populations in other regions likely reinforced the regime’s historically informed perception of Sunni Arabs as the greatest threat.Footnote 28 By the summer of 2011, violence was frequent and severe in other regions dominated by Sunni Arabs of tribal identity that had a historical rapport with the regime, like Darʿa and Idlib Governorates; the former was known, for example, as “the storehouse of the Baʿth (khizanat al-baʿth)” because of the number of party cadres it produced, yet its youth engaged in fierce challenge when regime elites dealt callously and violently with local residents (Mazur Reference Mazur2021, 129). Regime massacres in other regions of Syria—perpetrated overwhelmingly against Sunni Arab populations—created a widespread sense of outrage among Sunni Arabs in the northeast without a countervailing force equivalent to Kurdish fears of marginalization by a postrevolutionary successor regime.

Third, no institutionalized body equivalent to the PYD existed among Sunni Arabs. Although this deprived challengers of mobilizing structures when contention broke out, it also hamstrung the regime’s efforts to keep established clients on its side. Many of the regime’s main intermediaries with the northeast’s Sunni Arab population, local tribal notables, resisted its entreaties or were ambivalent toward them, avoiding any public stance and allowing youths to lead the uprising (Al Mashhour Reference Al Mashhour2017, 27). When the regime then sought to limit the activities of nascent challenger organizational structures like the LCCs by detaining their members, this application of violence created further grievances and gave the nonviolent activists a stark choice between exile and joining violent rebels for protection in the countryside (Darwish Reference Darwish2016). Many chose the latter, following a logic that has been shown to fuel participation in violent uprisings (Kalyvas and Kocher Reference Kalyvas and Kocher2007) and creating the foundations for an increasingly violent uprising in the northeast.

While scholars are not party to internal regime deliberations over repression techniques, the regime’s actions traced in this section evince an effort to differentiate protest repression along ethnic lines and make ethnic boundaries salient among populations engaging in contentious challenge. The regime assiduously avoided using violence against Kurdish protesters and tolerated the rapid expansion of the PYD, pushing protest to focus increasingly on Kurdish nationalism so as to separate Kurdish challengers from the overall uprising.

Conclusion

This article presents a theory of why governments repress some groups more harshly than others when faced with “negative coalition” challenge to their rule. Given salient identity divisions, incumbents are likely to make concessions to groups they view as less threatening while meting out harsh repression against the most threatening groups. Quantitative evidence from the 2011 Syrian uprising shows that Kurdish-majority towns were significantly less likely to face repression compared to Sunni Arab tribal communities in Syria’s northeast, despite a history of patron-client relationships between the latter and the regime. A closer, qualitative look at contention in this region reveals the steps the regime took to co-opt and redirect Kurdish protests away from the national movement. The regime allowed Kurdish protests making ethnically specific claims, while repressing protest making nationally focused claims. The regime also tolerated an organization, the PYD, that confined its claims to ethnic demands and policed Kurds who strayed from that position. An analogous strategy was not available with Sunni Arabs of the region, both because of the lack of organizations to engage in in-group policing and because repression of Sunni Arabs in other areas of the country undermined the credibility of any targeted concessions.

Our findings have implications for the scholarly understanding of political repression and, particularly, the logics of authoritarian incumbent response to protest. First, we show that recent work on the coalitional character of revolutionary challenge has an analog in incumbent strategies of repression. Incumbent regimes assess which parts of the coalition pose the greatest threat and consider how to fragment coalitions, taking into account second-order effects. As we showed, the regime assessed both how Kurds would react to Sunni Arab communities’ violent response to regime violence and how Sunni Arab challengers would perceive Kurds when the latter were spared otherwise widespread regime attacks on challengers. Although present in individual studies, particularly about the Middle East, the idea that regimes use violence against one population to communicate with another—and to sow divisions between them—has been little studied in the general repression literature (Przeworski Reference Przeworski2023). Future research can examine other second-order effects of repression, such as the role of international actors and potential pro-regime countermobilizers and how challengers respond to regime strategies.

Second, the identity-based targeting documented here shows that not all incumbents mechanically attempt to shore up existing client bases, suggesting the possibility that revolutions may result in rapid coalition restructuring and change in alignment of identity groups. Although our empirical work examines one regime’s response to a protest coalition bridging salient ethnic divisions, the theory could be useful in making sense of situations where regimes aim to divide protest coalitions along other identity lines, such as region or class. When boundaries exhibit properties of impermeability and relevance to public life, regimes should be able to take advantage of any potential internal division among protesters and employ a more measured response toward the group they least expect to take over after a successful revolution. Further cross- and subnational testing can help establish the extent to which our findings are empirical regularities across other contexts and forms of identity-based division.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S153759272510279X.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Salam Alsaadi, Killian Clarke, Christopher Fariss, Kerstin Fisk, Arzu Kibris, Matthew Nanes, Güneş Murat Tezcür, Gary Uzonyi, Beth Whitaker, participants in our panel at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA) and the Special Forum on the Study of Geography and War organized by Bryce Reeder and Gary Uzonyi at the University of Missouri.