1. Introduction

Although language is universal among humans, a host of research suggests meaningful individual and group variation that can potentially shed light on the factors and processes involved in typical and atypical language development, including speech development. Recent work suggests that canonical proportion (CP; introduced below) is one measure of speech development that can be deployed in a large age range at scale. The present study explores a recently released large dataset, the Speech Maturity Dataset (SMD; Hitczenko et al., Reference Hitczenko, Peurey, Harvard, Tey, Seidl, Semenzin, Scaff, Lavechin, Kelleher, Hamrick, Gautheron, Cychosz, Casillas and Cristia2025), which builds upon previous work (Cychosz et al., Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021; Hitczenko et al., Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023; Semenzin et al., Reference Semenzin, Hamrick, Seidl, Kelleher and Cristia2021), and includes data from hundreds of children growing up exposed to various language and cultural backgrounds. Our primary goal is to harness variability in the SMD to understand how several aspects of language environments may relate to the development of CP.

1.1. Indicators of speech development

Research reveals a variety of indicators of the process whereby children come to control the form and meaning of their vocalisations. For example, the number of speech-like vocalisations (i.e., Children’s Vocalisation Counts) increases with children’s age (e.g., Gilkerson et al., Reference Gilkerson, Richards, Warren, Montgomery, Greenwood, Kimbrough Oller, Hansen and Paul2017) and correlates with standardised tests such as the MacArthur–Bates Communicative Development Inventory (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Williams, Dilley and Houston2020). Other work studies how infants employ such speech-like vocalisations. For example, Long et al. (Reference Long, Bowman, Yoo, Burkhardt-Reed, Bene and Oller2020) reported that over half of infants’ speech-like vocalisations (“protophones” in that paper) are directed to nobody in particular (rather than socially motivated), at least based on lab recordings of children aged 3–10 months.

Other research zooms into phonetic characteristics of the vocalisations themselves. For instance, vocalisations containing clear consonant–vowel transitions begin to appear in infants’ babble at around 7 months of age, constituting about 15% of their syllables by 10 months of age (Oller et al., Reference Oller, Eilers, Neal and Schwartz1999). Research tracking the syllable or word shapes apparent in infants’ speech often finds continuity across babbling and first words (e.g., Vihman, Reference Vihman2019). Yet others, able to determine which words children aim to say, measure the percentage of sounds correctly produced and derive the timeline of mastery of various consonants (a review in McLeod & Crowe, Reference McLeod and Crowe2018). Fine-grained phonetic measures suggest speech development continues well beyond early childhood (Nip & Green, Reference Nip and Green2013).

1.2. Canonical proportion in early speech development: background and previous research

The present study follows much previous research in setting aside all non-speech-like vocalisations (like crying and laughing), which will not be studied further here. Instead, we focus on a division among speech-like vocalisations, aimed at capturing children’s increasing ability to produce well-formed syllables in both early babbling and later-developing meaningful speech (Cychosz et al., Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021). Among speech-like vocalisations, we distinguish those containing clear consonant–vowel or vowel–consonant transitions (canonical) and those that do not (non-canonical). Experts may argue that the meaning of “canonical” here is different than that found in discussions of canonical babbling ratios (e.g., CBRsyl and CBRutt; Molemans et al., Reference Molemans, van den Berg, Van Severen and Gillis2012; Oller et al., Reference Oller, Eilers, Steffens, Lynch and Urbano1994; note that Cychosz & Long, Reference Cychosz and Long2025, reported no effect of using syllables vs. utterances on any of their analyses). Canonical babbling ratio often indexes the proportion of utterances or syllables that are canonical based on a very precise definition (e.g., with a supraglottal constant and fully resonant vowel joined by a rapid, adult-like transition), and it is typically applied by expert annotators (but see Oller et al., Reference Oller, Eilers and Basinger2001) onto babble by pre-linguistic infants. To protect privacy and avoid sharing sensitive information (e.g., names that could be obvious when listening to full vocalisations), we follow Cychosz et al. (Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021) by using automated algorithms to select vocalisations and then split them into 500 ms clips. This approach additionally allows judgment by minimally trained annotators. Even though the methods diverge, it is possible that CP and CBR yield similar results. To the best of our knowledge, no published study has assessed this.

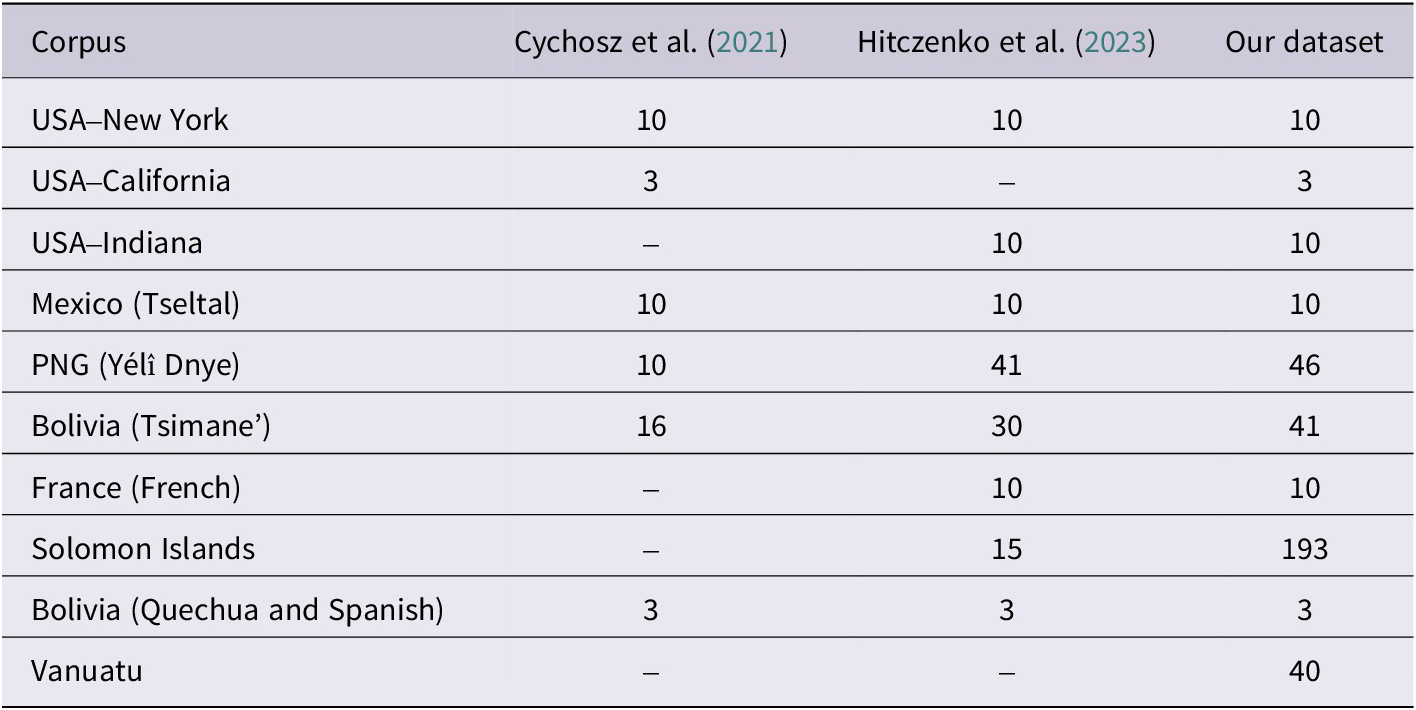

To date, there have been only four studies using CP, which we summarise next. Two cross-linguistic investigations have examined parts of the dataset used in the present study (see Table 1). Cychosz et al. (Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021) analysed 52 infants aged 1–36 months, who were growing up in a variety of communities, as monolinguals or bilinguals. The authors found that, similarly to canonical babbling ratios, CP in these data reached about 15% by 10 months of age. However, by employing CP, they could ascertain that this percentage continued to increase in toddlerhood, reaching about 40% by 36 months. The authors argued that CP, thus defined, is a broader indicator of speech development that remains relevant beyond the babbling stage. In addition, they did not visually detect large differences across groups, which they interpreted as a sign that CP may be resilient to differences across languages and/or communities. However, they did not explicitly test for a difference between monolinguals and the others.

Table 1. Number of participants included in each corpora in previous studies and in the present dataset. The three papers largely build on each other. Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023) included all the data in Cychosz et al. (Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021) (except for USA–California). Our study includes all the data in Hitczenko et al. and more

Building on Cychosz et al. (Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021)’s dataset, Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023) extended coverage by adding 77 children (total N = 129 children) from three additional communities. By extending the age range to 6 years, they documented increases in CP beyond toddlerhood reaching up to ~80%, lending further credence to Cychosz et al.’s argument that CP may continue to track speech development beyond the pre-linguistic period. Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023) also reported differences in CP based on the typological properties of the language(s) children were learning and whether children were growing up in an industrialised community. They did not investigate potential differences as a function of multilingualism.

Two other studies on CP bring important information to bear regarding the value of the CP measure. Crucially, Semenzin et al. (Reference Semenzin, Hamrick, Seidl, Kelleher and Cristia2021) demonstrated high levels of convergence across laboratory coding and citizen science approaches when studying a sample of 20 North American English-learning children. They derived two CP measures: one by having laboratory annotators, who had access to content and context of entire children’s vocalisations, and another through the same citizen science platform our own study builds on. They report strong correlations (r > .8) between laboratory CP and citizen science CP, indicating a high degree of agreement between the two methods. In addition, Semenzin et al. (Reference Semenzin, Hamrick, Seidl, Kelleher and Cristia2021) documented age-related CP increases among low risk controls aged 4–18 months, whereas children with Angelman syndrome (a neurogenetic disorder) aged 11–53 months exhibited age-related decreases. This aligns conceptually with other research linking lower canonical babbling ratios with atypical language development (e.g., Patten et al., Reference Patten, Belardi, Baranek, Watson, Labban and Oller2014).

Finally, Ott and Cychosz (Reference Ott and Cychosz2025) examined CP in 130 English-learning children at a mean age of 3 years, whose CP ranged between 20% and 76%. They observed a positive correlation between CP and age in their sample of 28–49-month-olds. Moreover, they documented that CP significantly predicted standardised assessments of speech and language, which the children completed approximately 1 year later, including consonant articulation, vocabulary size, phonological awareness, and phonological working memory. This parallels findings that delayed onset of canonical babbling (the age at which canonical syllables emerge) is associated with smaller vocabularies in later development (Oller et al., Reference Oller, Eilers, Neal and Schwartz1999).

1.3. Potential factors that may influence the development of CP

The above literature suggests that, although there are systematic increases in CP with age, there may additionally be meaningful individual (Ott & Cychosz, Reference Ott and Cychosz2025) and group variation in CP (Cychosz et al., Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021; Hitczenko et al., Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023; Semenzin et al., Reference Semenzin, Hamrick, Seidl, Kelleher and Cristia2021). Here, we study three factors that vary in our dataset (SMD; Hitczenko et al., Reference Hitczenko, Peurey, Harvard, Tey, Seidl, Semenzin, Scaff, Lavechin, Kelleher, Hamrick, Gautheron, Cychosz, Casillas and Cristia2025) and that reflect language and environmental diversity: multilingual exposure, syllable complexity, and community. In this section, we justify why these three factors might (not) influence the trajectory of CP.

Multilingual exposure. Should monolingual status affect CP? Since CP reflects the proportions of well-formed syllables in children’s speech, it serves as a potential indicator of whether multilingual exposure influences the rate of speech development. One long-standing hypothesis in the field of language development has postulated that multilingual exposure might delay early speech milestones (a discussion in Fibla et al., Reference Fibla, Sebastian-Galles and Cristia2021) because of at least two reasons: First, the presence of multiple linguistic systems may introduce cognitive and linguistic complexity and thus confuse the learners; and second, all else equal, multilinguals may receive less input in each of their languages than corresponding monolinguals, which could influence how quickly stable speech forms emerge (in perception and/or production). Although there is a long controversy in the field of lexical acquisition (with some work suggesting delays, and others showing none; Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Luk, Peets and Sujin2010; Byers-Heinlein, Reference Byers-Heinlein2013; Hoff et al., Reference Hoff, Core, Place, Rumiche, Señor and Parra2012; Oller et al., Reference Oller, Pearson and Cobo-Lewis2007; Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Fernández and Oller1993), the bulk of the evidence suggests that there may not be any difference between monolinguals and multilinguals. However, there is less work pertaining to phonological structure. By examining CP in monolingual and multilingual children, we aim to determine whether multilingual exposure influences not just vocabulary size but also the very structure of early speech patterns. Evidence of this comes from both specific and broader overall multilingualism studies. Oller et al. (Reference Oller, Eilers, Urbano and Cobo-Lewis1997) examined 29 English–Spanish bilingual infants and found they exhibited similar canonical babbling ratios as 44 monolingual infants. In contrast, more recently, Bergelson et al. (Reference Bergelson, Soderstrom, Schwarz, Rowland, Ramírez-Esparza, Hamrick, Marklund, Kalashnikova, Guez, Casillas, Benetti, Alphen and Cristia2023) took a wider perspective, analysing 1,001 children’s speech-like vocalisations using data collected with LENA, a wearable device that records daylong, naturalistic language input and output. The sample included children (2–48 months) from diverse linguistic backgrounds, from both industrialised and non-industrialised communities, with some children at risk of atypical development. Despite the large sample size in their study, they found that the number of speech-like vocalisations children produced did not vary as a function of multilingual status (but see Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Degotardi, Sweller and Djonov2023). Admittedly, no previous study looked at CP specifically, a gap we sought to fill.

Syllable complexity. Some previous studies have demonstrated that ambient language influences early speech development (Andruski et al., Reference Andruski, Casielles and Nathan2014; de Boysson-Bardies et al., Reference de Boysson-Bardies, Hallé, Sagart and Durand1989; de Boysson-Bardies & Vihman, Reference de Boysson-Bardies and Vihman1991; Levitt & Wang, Reference Levitt and Wang1991; Poulin-Dubois & Goodz, Reference Poulin-Dubois, Goodz, Cenoz and Genesee2001; Sundara et al., Reference Sundara, Ward, Conboy and Kuhl2020). For instance, previous cross-linguistic research has shown that children learning languages with simpler syllable structures, such as Turkish (moderate syllable complexity), acquire phonological awareness faster than those learning languages with more complex syllable structures, such as English (Stringer, Reference Stringer2021). Given that SMD contains data from several different languages, but not enough in each, we sought to employ a typological classification that systematically differs across languages, and which may directly influence the various types of syllable structures that children are exposed to, since syllables are a foundation of speech production. For this, we turned to Maddieson (Reference Maddieson, Dryer and Haspelmath2013), who categorised languages as a function of the types of syllables allowed: a simple syllable complexity if only open syllables were allowed ((C)V); moderately complex syllable complexity if additionally some codas and complex onsets were allowed ((C)(C)V(C)); and complex syllable complexity if additional syllable shapes were permissible ((C)(C)(C)V(C)(C)(C)). The details of Maddieson’s categorisation will be discussed in Section 2.

How may a language’s syllable complexity status influence early speech development? Previous work shows that children simplify their output to match their articulatory capacities (e.g., Vihman, Reference Vihman2014), such that, early on, CV syllables are over-represented. Moreover, children’s own productions also influence how they perceive spoken input, heightening their attention to sounds and sound sequences they already produce (DePaolis et al., Reference DePaolis, Vihman and Nakai2013; Vihman, Reference Vihman2014). This is consistent with the findings that children whose native language allows only simple syllable complexity might be exposed to substantially more input matching their preferred patterns than children exposed to languages with more complex syllable complexity. Potentially, in languages with simpler syllable complexity, as infants begin to babble, their caregivers more easily recognise their babble as real words since there are fewer mismatches with the target word due to, for example, dropped codas or simplified clusters, probably affecting the social feedback loop that reinforces canonical vocalisations (Warlaumont et al., Reference Warlaumont, Richards, Gilkerson and Oller2014). Thus, considering both input frequency and social feedback, one might expect children learning simple syllable complexity languages to develop CP faster.

Using a subset of the SMD, Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023) found a significant effect of syllable complexity on CP. However, the strongest difference was between moderate and the other types, which challenges the assumption that syllable complexity linearly influences CP development. Similarly, Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Jhang, Relyea, Chen and Oller2018) investigated the canonical babbling ratio in long-form recordings from 21 infants learning English (a complex syllable complexity language) in the United States and Chinese (a moderate one) in both the United States and Taiwan, hypothesising that the lower level of syllable complexity found in Chinese may affect outcomes. Children learning Chinese showed numerically higher canonical ratios, although the difference was not statistically significant. Together, these previous findings invite further attention to the input language’s syllable complexity classification.

Communities. In this study, we follow previous work by adopting a simple first approach to classifying communities (Cristia, Reference Cristia2023; Hitczenko et al., Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023). Communities are classified as non-industrialised if they are rural, practice a subsistence-based economy, and have limited access to formal education and healthcare, in contrast to industrialised communities, which have a market-based economy and wide access to formal education and healthcare services. SMD contains data from children growing up in 10 communities. Based on this classification, most communities in SMD were considered non-industrialised. Several studies in children’s lexical development have reported that children in non-industrialised communities have smaller vocabularies and/or lower language scores than their industrialised counterparts (e.g., Ma et al., Reference Ma, Jonsson, Feng, Weisberg, Shao, Yao, Zhang, Dill, Guo, Zhang, Friesen and Rozelle2021; Vogt et al., Reference Vogt, Mastin and Aussems2015; see also Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Pappas, Rule, Gao, Dill, Feng, Zhang, Wang, Cunha and Rozelle2024). However, other studies have found comparable language development trajectories between children from non-industrialised and industrialised communities (Casillas et al., Reference Casillas, Brown and Levinson2020, Reference Casillas, Brown and Levinson2021).

This raises the question: How might community differences influence CP? The two previous studies on which we build reached opposite conclusions. Based on the first 52 children, Cychosz et al. (Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021) commented on the lack of salient visual differences in CP across the various communities (each represented by only 3–16 children). In contrast, by increasing the sample size to 129 children and attempting a comparison based on a dichotomic non-industrialised/industrialised distinction, Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023) found significant variability: Children in non-industrialised communities showed higher CPs than those in industrialised communities but similar developmental trajectories, as there were no interaction effects with age. Our expanded dataset allows us to examine the robustness and generalisability of these patterns across a broader sample.

1.4. The present study

Our study harnesses variability in SMD to explore how CP varies by three experiential factors: multilingualism, syllable complexity, and community characteristics. Since our dataset includes and expands upon data analysed in Cychosz et al. (Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021) and Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023), our work is an exploratory extension of theirs, and not confirmatory testing given the overlapping data.

2. Methods

Reproducibility of analyses has been ensured using a repository accessible at the review stage via OSF: https://osf.io/yjq7r/?view_only=afc0ad9758dc457b9af97056f97540d2.

2.1. Dataset

Our data come from the SMD (Hitczenko et al., Reference Hitczenko, Peurey, Harvard, Tey, Seidl, Semenzin, Scaff, Lavechin, Kelleher, Hamrick, Gautheron, Cychosz, Casillas and Cristia2025). Children were individually recorded using an unobtrusive wearable recording device, resulting in long audios (e.g., 15 consecutive hours), which were analysed either manually or using state-of-the-art software (called VTC; Lavechin et al., Reference Lavechin, Bousbib, Bredin, Dupoux and Cristia2020) to automatically identify sections of the audio in which the child or others vocalised (i.e., babbled, cooed, or spoke). These vocalisations were sampled using different methods, including key child vocalisation sampling (extract audio sections attributed to the key child), loudness sampling (extract audio sections based on the amplitude profile, so as to be independent from VTC), and female adult vocalisation sampling (extract audio sections attributed to female adults). Once sampled, these audio sections were cut into short ~500 ms clips. The 500 ms duration was selected because it is short enough to meet ethical and privacy standards, preserving participants’ sensitive information and voice identity, yet long enough for listeners to reliably judge whether the clip contains a canonical vocalisation for perceptual classification, as shown in prior work (e.g., Semenzin et al., Reference Semenzin, Hamrick, Seidl, Kelleher and Cristia2021).

CP has been calculated over different units in different studies, such as utterances (in the laboratory annotation used in Semenzin et al., Reference Semenzin, Hamrick, Seidl, Kelleher and Cristia2021), or chunked vocalisation (Cychosz et al., Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021; Hitczenko et al., Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023; and citizen science CP in Semenzin et al., Reference Semenzin, Hamrick, Seidl, Kelleher and Cristia2021). Here, we calculated CP using those same fixed-length 500 ms clips. These clips do not necessarily align with complete child utterances or individual syllables.

The clips were then uploaded to a citizen science platform. For the vast majority of the data, the platform was Zooniverse, and the project was called the Maturity of Baby Sounds (https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/laac-lscp/maturity-of-baby-sounds). In this case, several thousand non-expert individuals contributed to crowdsourcing classifications after minimal training. Before the annotation, citizen scientists completed a tutorial and had access to reference materials and discussion forums for general questions. The data from the 52 participants from Cychosz et al. (Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021) came from a different citizen science platform, which is no longer available. In all cases, at least three citizen scientists classified each individual clip into different categories: canonical, non-canonical, laughter, crying, or none of the above. Considering only clips in which majority annotators agreed on the label, Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023) calculated CP for each child by dividing the total number of clips that had been classified as canonical by the sum of the number of clips classified as either canonical or non-canonical. They did this for every combination of recording date and sampling method. For instance, a child who was recorded on two separate days, and had key-child as well as female-adult vocalisations separately sampled from each day, would have four CP values associated with their participant ID, only two of which – the two key-child CP values – are relevant to the present study. For a more comprehensive description of the data collection and processing involved in the SMD, refer to Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Peurey, Harvard, Tey, Seidl, Semenzin, Scaff, Lavechin, Kelleher, Hamrick, Gautheron, Cychosz, Casillas and Cristia2025).

No intra-annotator reliability was assessed, as each citizen scientist typically labelled each clip only once. Support for inter-rater reliability at the individual clip label comes from Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Suresh, Warlaumont, Hitczenko, Cristia and Cychosz2025; Interspeech), who studied the SMD and reported fair-to-moderate agreement among multiple human annotators, with a weighted Fleiss’ kappa of .276 (95% CI [.266, .285]). However, our analyses do not rely on individual clip labels. Instead, we aggregate all clips belonging to each child on the same recording day to compute a single child-level CP value. The aggregation substantially reduces the impact of any disagreements on individual clips. There is also promising evidence that these aggregated CP values are highly accurate. The validity of this crowd-sourcing approach was supported by Semenzin et al. (Reference Semenzin, Hamrick, Seidl, Kelleher and Cristia2021), which analysed data from 20 children (10 with Angelman Syndrome, 10 typically developing; this is the USA–Indiana corpus, within SMD). They found high correlations between CP derived from expert human annotators and citizen scientists (overall: r(18) = .938, CI [.848, .976], p < .001; Angelman syndrome: r(8) = .855, CI [.487, .965], p < .001; typical developing children: r(8) = .966, CI [.858, .992], p < .001).

In its rawest format, SMD data are based on individual chunks. For our scientific purposes, we selected data allowing us to calculate a CP measure per child at a given age. Therefore, we excluded chunk-level data when they had been sampled to focus on female voice or when they had not been labelled as belonging to an infant or child. When multiple CP measures were available less than 15 days apart, we merged them. We also excluded 10 CP measures from children with atypical language development (Semenzin et al., Reference Semenzin, Hamrick, Seidl, Kelleher and Cristia2021). The final dataset includes 366 children (described in detail in Section 2.2), with each child contributing up to one to three CP measures at different ages (median = 1, mean = 1.04), for a total of 379 included CP measures. On average, each CP measure was based on 59 canonical clips and 114 non-canonical clips. Table 2 presents, for each corpus, the number of CP measures in each age range. Note that children recorded at multiple time points contribute one CP measure for each recording session.

Table 2. Number of CP measures across age range, by corpus

^Languages spoken in Solomon Islands: Roviana, Avaso, Babatana, Marco, Marovo, Pidjin, Sengga, Simbo, Sisinga, Ughele, Vaghua, and Varisi. *Languages spoken in Vanuatu: Bislama, Venen Taut, Petarmul, Neverver, Uripiv, Vinmavis, Novol, Epi, Nah’ai, Paama, Ninde, Tautu, French, Pinalum, Malo, Rano, Tauta, Santo Language, Ambae, Maevo, South, Atchin, and Tempun.

2.2. Participants

We analysed data from 366 unique children (193 boys; some children contributed data for >1 day) aged 2–76 months. These children came from a variety of linguistic backgrounds, representing 10 different corpora. Table 3 provides an overview of the characteristics of each corpus.

Table 3. Summary of corpus characteristics

*Languages spoken in Solomon: Roviana, Avaso, Babatana, Marco, Marovo, Pidjin, Sengga, Simbo, Sisinga, Ughele, Vaghua, and Varisi. †Languages spoken in Vanuatu: Bislama, Venen Taut, Petarmul, Neverver, Uripiv, Vinmavis, Novol, Epi, Nah’ai, Paama, Ninde, Tautu, French, Pinalum, Malo, Rano, Tauta, Santo Language, Ambae, Maevo, South, Atchin, and Tempun.

Within each corpus, SMD participants are classified as monolingual or multilingual following Bergelson et al. (Reference Bergelson, Soderstrom, Schwarz, Rowland, Ramírez-Esparza, Hamrick, Marklund, Kalashnikova, Guez, Casillas, Benetti, Alphen and Cristia2023): monolinguals are reportedly exposed to only one language (30.1% in the dataset); otherwise, they are multilinguals (i.e., non-monolinguals), regardless of the number of languages.

Monolingual children were further categorised based on the syllable complexity of their input language. Although it would have been possible to classify multilingual children as the highest syllable complexity of input languages (see Supplementary Table 2), we thought this may introduce additional noise due to inconsistent exposure levels across languages. Detailed language exposure information at the individual levels is not available. Classification followed Maddieson’s (Reference Maddieson, Dryer and Haspelmath2013) simple, moderate, and complex syllable complexity languages as follows: In languages classified as having a simple syllable structure, syllable structure is restricted to (C)V (C: consonant; V: vowel) sequences, allowing no onset consonant clusters, and only V and CV as permissible syllables. This category is relatively rare, representing only 12% of the languages studied by Maddieson. In our data, Yélî Dnye is the only language representing this category.

In contrast, languages classified as having moderate syllable complexity allow single codas and/or consonant clusters (typically involving an approximant or liquid) in onsets. This includes syllable types such as VC, CVC, CCV, and CCVC, in addition to the simpler structures V and CV. Around 57% of the languages studied by Maddieson are in this category. Tsimane’ is the only language classified as moderate syllable complexity in SMD.

Finally, languages with complex syllable complexity allow more intricate consonant clusters in both onsets and codas. Some examples of syllable structures that are allowed in languages with complex syllable complexity are V, CV, VC, CVC, CCV, CCVC, CVCC, CCVCC, CCCVCC, and CCCVCCC. The remaining 31% of languages were classified by Maddieson in this category. In SMD, French, English, and Tseltal are classified as having complex syllable complexity.

As for the last factor focused in this study, communities were classified as industrialised or non-industrialised (Cristia, Reference Cristia2023; Hitczenko et al., Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023). Our dataset includes four corpora from industrialised communities and six corpora from non-industrialised communities (see Table 3 for details). Although we acknowledge that the actual classification of communities in the real world is a complex and multifaceted process, the simple classification serves as a starting point for our analysis.

2.3. Analyses

All analyses were conducted in R version 4.3.2 (R Core Team, 2024), using the stats (R Core Team, 2024) and car (Fox & Weisberg, Reference Fox and Weisberg2019) packages for statistical analysis, and the ggplot2 (Wickham, Reference Wickham2016) package for data visualisation. To better match age distributions and in the presence of multicollinearity, we examined the predictive value of multilingual exposure, native language syllable complexity, and community type in three separate mixed-effects logistic regression models, with CP as the dependent variable. Weighted analyses were employed to account for the differences in number of clips available for each child and ensure accurate representation in the models. Specifically, each CP measure was weighted by the total number of canonical and non-canonical clips it was derived from (i.e., excluding those labelled as junk, NA, no majority label, and non-speech). The linear and quadratic terms of age (both z-scored) were also included, in interaction with the main effect being studied. As our study builds on Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023), with a larger dataset, we followed many of their statistical analysis approaches, including the inclusion of the quadratic term for age. We address multiple comparisons within each model by using q-values (which adjust for false discovery rate). Type 3 Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tests were performed to confirm the significance of main effects and interactions identified in the regression models.

Multilingual exposure, syllable complexity, and community were treated as categorical variables, with monolinguals, simple syllable complexity, and non-industrialised communities set as reference levels, respectively. Re-levelling was performed in relevant analyses to facilitate specific pairwise comparisons among different categories, as described in Section 3. Child_id was treated as a random variable nested within the corpus to account for individual and corpus-level variability.

3. Results

3.1. Multilingual exposure

To explore whether CP varies as a function of multilingual exposure, we analysed data from all participants, namely 366 children, spanning the entire age range (2–76 months). We fit a mixed-effects logistic regression model to test the effects of multilingual status, age, and their interaction on CP: CP ~ age × multilingualism + age 2 × multilingualism + (1|corpus/child_id).

The results revealed a significant main effect of multilingualism (Estimate = −.65, SE = .17, z = −3.83, p < .001), indicating that monolingual children demonstrated higher CP measures compared with multilingual ones (see Sections 1 and 2 of the Supplementary Material for robustness checks). At the mean age of the sample (25.3 months), CP is estimated at 0.36 for monolinguals and 0.22 for multilinguals, leading to a difference of 63.6% higher CP for the former compared with the latter. Both linear and quadratic terms for age were significant predictors of CP (Estimate = .52, SE = .06, z = 8.62, p < .001; Estimate = −.14, SE = .05, z = −2.87, p < .01). These results suggest that CP increases with age overall (as indicated by the positive linear term), but the significant negative quadratic term suggests that this increase slows down with age. Notably, no significant interaction between age and multilingualism was observed (Estimate = −.02, SE = .1, z = −.21, p = .84, 95% CI [−0.21, 0.17]). While this result may suggest similar age-related trends across groups, we caution that the confidence interval includes both negligible and small (positive and negative) effect sizes. Thus, the data are consistent with either true absence of an interaction or insufficient power to detect a true but small interaction. Figure 1 shows the CP distribution in monolingual and multilingual children across the children’s age.

Figure 1. Canonical proportions by age and multilingual exposure (full sample). The regression line represents the fitted model, and the shaded bands surrounding the line represent the 95% confidence intervals. Each data point represents a single child, with point size representing the total number of vocalisations contributed by that child (larger points represent children who produced more vocalisations).

Overall, these results suggest that CP increased with age, with growth slowing over time, and that monolingual children consistently exhibited higher CP than multilingual children.

3.2. Syllable complexity

Second, we explored the relationship between syllable complexity and CP among monolingual children. Since this analysis focuses only on monolingual children (as we do not have detailed information on languages spoken by each child in multilingual settings), we included 110 monolingual children (31 learning a simple syllable complexity language, 41 moderate, and 38 complex). This selection excluded 256 children from the analysis. We fit a mixed-effects logistic regression model to test the effects of syllable complexity, age, and their interaction on CP: CP ~ age × syllable_complexity + age 2 × syllable_complexity + (1|corpus/child_id).

This analysis revealed a significant main effect of syllable complexity on CP. Specifically, children learning a language of moderate syllable complexity (Estimate = −.73, SE = .14, z = −5.11, p < .001) and complex syllable complexity (Estimate = −.95, SE = .27, z = −3.52, p < .001) exhibited significantly lower CP compared with the reference category, namely children learning a language with simple syllable complexity, who exhibited the highest CP (see Section 3 of the Supplementary Material for a robustness check). Re-levelling syllable complexity with “moderate” as the reference category showed that the difference between moderate and complex syllable complexity was not statistically significant (Estimate = −.23, SE = .26, z = −0.87, p = .384). At the mean age of the sample (28.7 months), CP is estimated at .51 for simple, .35 for moderate, and .22 for complex, leading to a difference of 45.7% higher CP for the simple versus moderate, and 59.1% for moderate versus complex. As in the multilingual model discussed in the previous section, the linear age predictor had a significant positive effect on CP (Estimate = .38, SE = .13, z = 2.99, p < .005), and the interactions were not significant (all p > .05). However, unlike in the previous analysis, the quadratic term for age did not explain significant variance. This suggests that disaggregating monolinguals by syllable complexity reveals less of a plateau in older age groups than in the combined analysis represented in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows monolingual children’s CP as a function of age and their native language’s syllable complexity level.

Figure 2. Canonical proportions by age and syllable complexity in monolingual children. The regression line represents the fitted model, and the shaded bands surrounding the line represent 95% confidence intervals. Each data point represents a single child, with point size indicating the total number of vocalisations contributed by that child (larger points represent children who produced more vocalisations). *Others represent French, Tseltal, and English.

3.3. Communities

Last, we explored the relationship between community types (industrialised vs. non-industrialised) and CP. Noticing an unequal age range between industrialised and non-industrialised groups, we subset data to children aged 3–19 months, resulting in 148 children (115 non-industrialised, 33 industrialised) being included in a mixed-effects logistic regression model: CP ~ age × community + age 2 × community + (1|corpus/child_id).

The analysis revealed no significant main effects for the community (Estimate = −.38, SE = .42, z = −0.9, p = .37), suggesting no significant differences in CP measures between community types. Both the linear (Estimate = .16, SE = .06, z = 2.8, p < .01) and quadratic (Estimate = .16, SE = .08, z = 2.09, p < .05) terms for age were positively associated with CP, suggesting a developmental increase in CP over time that speeds up in this age range (3–19 months), unlike the significant plateauing observed in the analysis centred on multilingualism which spanned our full age range (2–76 months). No significant interaction was observed between community and age. Figure 3 reveals that children from non-industrialised communities exhibited a numerically higher CP than industrialised children at the youngest ages, with this difference narrowing with age. This pattern goes against what we might expect based on experiential factors. Given that industrialised children are typically exposed to more structured linguistic input, they would be expected to have higher CP. However, our results show the opposite, non-industrialised children start with higher CP, though the gap narrows with age.

Figure 3. Canonical proportions by age and community. The regression line represents the fitted model, and the shaded bands surrounding the line represent 95% confidence intervals. Each data point represents a single child (N = 115 non-industrialised; N = 33 industrialised), with point size indicating the total number of vocalisations contributed by that child (larger points represent children who produced more vocalisations).

4. Discussion

The present study explored the relationship between CP and three factors: multilingual exposure, ambient language syllable complexity, and community. Because our analyses were exploratory, we use statistical significance descriptively and not as null hypothesis testing, especially since we did not adjust for repeated testing across models. In our analyses of the SMD, monolingual children have higher CP than multilingual children. At the mean age of the sample (25.3 months), CP was estimated at .36 for monolinguals and .22 for multilinguals, meaning that monolinguals exhibited a 63.6% higher CP than multilinguals. We also found that monolingual children learning languages with simple syllable complexity exhibited the highest CP, followed by those learning languages with moderate and complex syllable complexity. At the mean age of the monolingual sample (28.7 months), CP was estimated at .51 for simple, .35 for moderate, and .22 for complex syllable complexity. This reflects a 45.7% higher CP for children learning simple versus moderate syllable complexity and a 59.1% difference between moderate and complex syllable complexity. Finally, we failed to find a significant difference between children from non-industrialised and industrialised communities. Next, we discuss each of these effects.

4.1. Multilingual exposure

The observed higher mean CP in monolingual versus multilingual children is consistent with the prediction made in the Introduction, whereby reduced input per language found in multilingual children causes acquisition delays (Fibla et al., Reference Fibla, Sebastian-Galles and Cristia2021). In line with this prediction, an Australian study (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Degotardi, Sweller and Djonov2023) found that monolingual children produced more vocalisations than multilingual children at preschool. However, the latter difference was not statistically significant after controlling for variables such as family income and home environment; and previous studies reported no significant differences in babbling (Oller et al., Reference Oller, Pearson and Cobo-Lewis2007) or speech-like vocalisation patterns between monolingual and multilingual children (Bergelson et al., Reference Bergelson, Soderstrom, Schwarz, Rowland, Ramírez-Esparza, Hamrick, Marklund, Kalashnikova, Guez, Casillas, Benetti, Alphen and Cristia2023).

4.2. Syllable complexity

In our analyses, children learning languages with simple syllable complexity showed higher CP than those learning languages with moderately complex or complex syllables. Note that we observed a different pattern from Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023). That analysis attributed all the Solomon corpus children to a “simple” complexity type, whereas we excluded them since we did not have detailed information about their ambient languages. Differences in results thus likely reflect both the increased sample size (Serdar et al., Reference Serdar, Cihan, Yücel and Serdar2021) and our methodological decision to focus specifically on monolingual children, illustrating how results can shift as datasets are expanded and analytical approaches are refined.

Could it be that the CP measure misrepresents languages with consonant clusters in some way? One may wonder if in languages with greater syllable complexity, where onset clusters are allowed, the sections of the 500 ms clip that reflect vowels or consonants are relatively shorter than in simpler syllables, and this leads to a higher proportion of clips labelled as non-canonical. We think this is not a good explanation of the effects we observed for syllable complexity on CP for several reasons. First, this would predict that children at ages where they start producing clusters would show lower CP, but this is not what we see in the data, where group differences between e.g. simple syllable complexity and complex syllable complexity languages are obvious even before 18 months, an age at which children do not readily produce many consonant clusters. Second, the 500 ms duration almost certainly covers a full syllable, even for syllables with complex onsets and codas. Finally, our request to citizen scientists was for speech-like VC or CV transitions, which should not penalise children who produce more clusters.

4.3. Communities

Our results did not align with Hitczenko et al.’s (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023) in terms of community differences. While their analysis of a subset of SMD yielded significantly higher CP in children from non-industrialised communities, ours did not reveal significant differences as a function of community type. This divergence may reflect an interplay between sample size, dataset composition, and analytical approaches that can occur when datasets are expanded.

4.4. Age

The data from all three analyses can shed light on how CP changes with age. During the early stages of development, CP increases rapidly as children make significant progress in oral motor and phonological skills, thereby improving their ability to articulate complex canonical forms (Anthony & Francis, Reference Anthony and Francis2005). In fact, our third analysis (Figure 3) suggests that in the 3–19-month range, CP is increasing rapidly, as evidenced by a positive and significant quadratic term. The first stage in which CP continues to increase goes on until at least 36 months of age (see Figure 2, regression line for complex syllable languages). However, as children reach more stable stages of speech production, the rate of CP growth slows. This slowing was reflected in the negative and significant estimate of the quadratic term of age observed in the first analysis (Figure 1). This slowdown aligns with other developmental milestones in children’s speech development. Coordination between lips and jaw continues to be refined between 2 and 6 years of age (Green et al., Reference Green, Moore, Higashikawa and Steeve2000), and developmental phonological processes (e.g., consonant cluster simplification) become less frequent after around 48 months (Sampallo-Pedroza et al., Reference Sampallo-Pedroza, Cardona-López and Ramírez-Gómez2014). Similarly, Hustad et al. (Reference Hustad, Mahr, Natzke and Rathouz2021) report that speech intelligibility increases markedly from 30 to about 48 months, followed by more gradual growth thereafter. Additional research is necessary to study the relationship between CP and other speech development indices, such as in Ott and Cychosz (Reference Ott and Cychosz2025).

Is it the case that these developmental trends vary as a function of the language’s syllable complexity? Our analyses did not reveal a significant interaction, but we hope the question is revisited by future work with larger sample sizes and better age coverage. Notice that the oldest children learning languages with complex syllable complexity were only 36 months of age; for moderate and simple syllable complexity, this was over 70 months. Future work should also problematise the fact that children learning languages with simple or moderate syllable complexity tend to have a higher CP starting point than children learning complex syllable complexity languages, which is unexpected if differences truly are due to exposure.

4.5. A better understanding of CP differences

This and previous papers present CP as a measure of speech development. But what precise conceptual aspect of speech development does CP capture and how does this relate to the effects we observed (multilingualism, syllable complexity) or lack thereof (community)? As evidence accumulates, it would be important to start developing inductive and deductive theoretical frameworks to provide causal accounts linking children’s experience to outcomes.

One possibility we speculate on is that CP captures differences in syllable duration. According to this explanation, our CP measure will better capture full CV or VC transitions in the speech of children whose syllables are shorter. This explanation would readily account for CP differences as a function of age (since older children produce shorter syllables; Nip & Green, Reference Nip and Green2013). Perhaps it may also account for syllable complexity differences, should future research find that syllables are shorter in languages with simple syllable complexity. However, we do not readily see how it may account for the multilingualism effect we observed.

Another possibility evoked in the Introduction is that children exposed to more input develop higher CPs because the additional exposure facilitates the formation of perceptual targets, similarly to processes likely involved in children developing larger vocabularies when exposed to more speech. We feel this hypothesis does not carry a large explanatory value with respect to our results. For instance, multilingualism-related differences have rather been attributed to input quantity within each language and ensuing confusion (Fibla et al., Reference Fibla, Sebastian-Galles and Cristia2021), and not the absolute quantities afforded. Similarly, the pathways we described in the Introduction for syllable complexity differences related to the amount of exposure to templates matching children’s spontaneous production, and not the overall amount of input.

Longitudinal work like Ott and Cychosz (Reference Ott and Cychosz2025) is beginning to shed light on the ways in which CP relates to other measures of speech and language development. Further work employing other statistical approaches (e.g., standard equation modelling) and carefully considering causal chains is needed to better understand how experience affects CP and speech development more broadly.

4.6. Limitations

This study builds on datasets previously analysed by Cychosz et al. (Reference Cychosz, Cristia, Bergelson, Casillas, Baudet, Warlaumont, Scaff, Yankowitz and Seidl2021), Semenzin et al. (Reference Semenzin, Hamrick, Seidl, Kelleher and Cristia2021), and Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023), with those earlier data forming part of our current sample. For that reason, this study cannot be confirmatory, given that our dataset was not statistically independent from previous observations. This exploratory nature does not, in our view, detract from the value of the present work. For example, Hitczenko et al. (Reference Hitczenko, Bergelson, Casillas, Colleran, Cychosz, Grosjean, Hamrick, Kelleher, Scaff and Seidl2023) found that children from rural communities have higher CP, whereas our analysis of the expanded dataset did not. This difference highlights the importance of revisiting earlier findings using expanded datasets, rather than assuming that a given positive result will necessarily be ratified with a larger sample.

Another limitation concerns statistical inference in large shared datasets like SMD. Our field does not yet have clear guidelines for multiple-comparison correction with resources that are analysed repeatedly, and where some patterns are already known from previous studies. In such cases, it may be more appropriate to use an explicit exploratory approach, as we have done here. Because the same data are used in multiple studies, it is not possible for future researchers to be completely unaware of existing patterns in previous work.

Three other limitations relate to SMD in particular. At present, SMD contains only one language representing each of the simple and moderate syllable complexity categories, and only three for the complex one. In addition, we could only test the difference across industrialised and non-industrialised communities in a narrow age range (3–19 months). A broader age range would be important to capture the full developmental trajectory. Second, SMD lacks detailed information on the specific language spoken by multilingual children and their extent of exposure to each language, in part because of interdisciplinary collaboration and data reuse. For example, infants in Solomon Islands were recorded as part of a larger study, limiting the collection of specific language details due to survey length constraints. Today, there are no standardised methods for quickly gathering multilingual exposure information that do not require lengthy (30-min) surveys. As a result, we cannot categorise children by factors thought to be key in bilingualism and multilingualism research, such as language dominance and proportion of exposure (Byers-Heinlein, Reference Byers-Heinlein and Schwieter2015). In addition, SMD relies on judgments based on 500 ms clips. In such clips, suprasegmental cues, such as intonation, rhythm, and duration, are often not fully captured, particularly when isolated from their broader utterance context. Previous studies (Kehoe, Reference Kehoe2022; Vihman et al., Reference Vihman, DePaolis and Davis1998) have shown that, when children grow, they begin to adjust syllable duration according to prosodic structure, typically producing longer final syllables. Such changes cannot be studied with SMD data.

5. Conclusions

This study offers valuable insights into the potential impact of multilingual exposure, syllable complexity, and community factors on the development of CP in children’s early language production. By analysing a large and diverse dataset, which includes understudied languages and communities, our findings emphasise how universal developmental processes and language-specific characteristics impact early speech development. Our findings suggest that multilingual exposure may explain some variability in CP development. Moreover, provided that a large enough sample and age range is represented, children exposed to languages with simple syllable complexity may tend to have higher CP than those learning languages with moderate and complex syllable complexity, underscoring the influence of syllable structure of the ambient language on the development of speech production. Finding differences in speech development as a function of these further emphasises the importance of considering a range of linguistic and cultural contexts when studying language acquisition. Although an analysis based on a binary classification of communities into non-industrialised versus industrialised did not reveal significant differences, further research with more nuanced classification is needed to shed light on potential community-based differences. Ultimately, this study contributes to a nuanced understanding of the diverse pathways children take across languages during early speech development.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000926100476.

Acknowledgements

ChatGPT was used for minor language refinement.

Funding statement

This work was funded by the J. S. McDonnell Foundation Understanding Human Cognition Scholar Award and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (ExELang; Grant Agreement No. 101001095).

Competing interests

We have no known competing interests to disclose.

Disclosure of use of AI tools

No AI tools were used for data analysis, study design, or interpretation.

Statement of ethical approval

This present paper makes use of the SMD, which comprises 10 different corpora collected independently by different research teams. Ethical approval and consent procedures were obtained separately for each corpus, as detailed below.

1. Corpus: Bolivia (Quechua and Spanish). a. Data were obtained via the scientific archive HomeBank. Ethical approval details are not included in the archive metadata and were managed by the original data collectors.

2. Corpus: Bolivia (Tsimane’). a. Name of the ethics committee that approved the research: UNM Health Sciences Center Human Research Review Committee (HRRC).

b. Ethics Committee approval number: 17-262.

c. Types of consent obtained: Verbal informed consent was obtained from participants and/or parents or legal guardians of child participants using an IRB-approved verbal consent procedure. Child assent was obtained where developmentally appropriate.

3. Corpus: France (French). a. Name of the ethics committee that approved the research: Comité d’Éthique de la Recherche (CERES/CER Paris Descartes; later CER U-Paris).

b. Ethics Committee approval number: IRB 2015140001072 (2015-14), with amendment 2020-20-BERGMANN-CRISTIA-HAVRON.

c. Types of consent obtained: Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians of participating children. Child assent was obtained where developmentally appropriate.

4. Corpus: Mexico (Tseltal). a. Data were obtained via the scientific archive HomeBank. Ethical approval details are not included in the archive metadata and were managed by the original data collectors.

5. Corpus: PNG (Yélî Dnye). a. Name of the ethics committee that approved the research: Ethics Committee of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics (ECSW).

b. Ethics Committee approval number: ECSW2017-3001-474 (Manko–Rowland; Language Development).

c. Types of consent obtained: Written informed consent was obtained, including parental consent and child assent/co-consent where applicable.

6. Corpus: Solomon Islands. a. Name of the ethics committee that approved the research: University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (UNSW HREC).

b. Ethics Committee approval number: HC180755.

c. Types of consent obtained: Written informed consent was obtained, including parental consent and child assent/co-consent where applicable, in accordance with UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee approval.

7. Corpus: USA–California (English & Spanish). a. Data were obtained via the scientific archive HomeBank. Ethical approval details are not included in the archive metadata and were managed by the original data collectors.

8. Corpus: USA–Indiana (English). a. Data were obtained via the scientific archive HomeBank. Ethical approval details are not included in the archive metadata and were managed by the original data collectors.

9. Corpus: USA–New York (English). a. Data were obtained via the scientific archive HomeBank. Ethical approval details are not included in the archive metadata and were managed by the original data collectors.

10. Vanuatu. a. Name of the ethics committee that approved the research: Ethics Committee (Ethik-Kommission), Universitätsklinikum Jena, Germany.

b. Ethics Committee approval number: 4818-06/16.

c. Types of consent obtained: Written informed consent was obtained, including parental consent and child assent/co-consent where applicable, in accordance with ethics approval and Vanuatu National Cultural Council research requirements.