Introduction

Many of today's most pressing democratic challenges are related to the quality of public debates, such as the partisan polarisation of news outlets, the proliferation of ‘fake news’ and the discrediting of media sources by politicians at the highest levels. At the same time, many of the most dramatic instances of democratic contestation are taking place in the public sphere, from the rise of social movements that have triggered worldwide processes of political change on issues like sexual harassment, LGBTQ rights and police brutality, to the spread of whistleblower and watchdog organisations.

To what extent do citizens consider the public sphere important for democracy? Are certain groups more likely to care about the public sphere? How does the quality of the public sphere in a country affect citizens’ views about its importance? Older (e.g., Schumpeter Reference Schumpeter1950; Downs Reference Downs1957) and more recent strands of democratic theory (e.g., Brennan Reference Brennan2016; Achen & Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017) have questioned the willingness and capacity of ordinary citizens to acquire political information and participate in public debates. Some of these works have even argued that broad public deliberation is neither necessary nor desirable for democratic politics. Even mainstream procedural theories of democracy (e.g., Dahl Reference Dahl1973, Reference Dahl1989) see the institutions that underpin public deliberation as ancillary to more important parts of the democratic system, such as free and fair elections or the rule of law. However, if citizens consider public debate central to democracy, electoral integrity and legal equality will not suffice to make collective decisions legitimate in their eyes. This is especially important if those who care the most about public debate are also those who are already disadvantaged by or dissatisfied with political institutions.

To our knowledge, this article represents the first empirical and cross‐national analysis of citizens’ views about the importance of the public sphere. Building on problem‐based approaches to democracy (Warren Reference Warren2017), the article first outlines three democratic functions that public spheres are expected to perform – voice, critique and information – and describes how these functions relate to democratic principles of inclusion, accountability and publicity. We argue that citizens view these functions pragmatically, in terms of the extent to which these functions empower them to participate effectively in collective decision making. In other words, citizens tend to care more about the public sphere depending on (1) their ability to influence political decisions through public debate, and (2) the extent to which voice, critique and information are effective means to address democratic problems that are particularly important to them. We then derive a set of hypotheses from the normative literature on deliberation about which groups are more likely to care about the different functions of the public sphere depending on their cultural capital (education), shared experiences of discrimination (cultural and sexual minority status) and dissatisfaction with government performance.

Using data from Wave 6 of the European Social Survey (ESS) (Ferrín & Kriesi Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016), the statistical analyses indicate, first, that citizens see access to reliable information among the most important aspects of democracy. Second, we observe variation among citizens in how important they consider the different functions of public spheres. More educated citizens tend to assign greater importance to all three functions compared to less educated citizens. Members of cultural and sexual minorities are instead more likely to emphasise the importance of giving voice to alternative perspectives. In turn, dissatisfied citizens are more likely to prioritise public criticism and access to reliable information. Finally, a set of mixed‐effects models indicates that experience with more democratic public spheres magnifies differences based on education and minority status, but reduces differences based on dissatisfaction with the government.

The article makes two contributions to research on democratic attitudes and democratic theory. First, it joins recent studies that propose a shift from ‘model‐based’ to ‘problem‐based’ theories of democracy in research on democratic attitudes (Werner et al. Reference Werner, Marien and Felicetti2020; Hansen & Goenaga Reference Hansen and Goenaga2019). This shift allows us to identify specific democratic practices and institutions that different social groups are more likely to prioritise, depending on whether such practices and institutions effectively empower them to participate in collective decision making.

Second, against those arguments that question the relevance of public debate for contemporary representative democracies (e.g., Hibbing & Theiss‐Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss‐Morse2002; Brennan Reference Brennan2016; Achen & Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017), we provide robust empirical evidence that citizens see many of the normative goods produced by public spheres as core aspects of democracy, comparable in importance to competitive elections and the rule of law. The article thus advances an empirically grounded and citizen‐centred defence of the importance of public debate for democratic politics.

The next section discusses related research on democratic attitudes. The third section outlines the normative functions of public spheres and theorizes which groups are more likely to consider them important for democracy. We then describe the data and empirical strategy and present the results. We conclude by highlighting the main contributions of the article and suggesting avenues for further research.

Previous research on democratic attitudes

We adopt a normatively ‘thin’ definition of the public sphere as a system of actors and institutions – parties, media, governments, interest groups and informal networks – that promotes talk‐based interactions to express and shape individual and collective preferences on public issues (Neblo Reference Neblo2015; Hendriks Reference Hendriks2006; Parkinson & Mansbridge Reference Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). These communicative interactions do not need to meet idealised standards of deliberation and include non‐deliberative forms of negotiation, persuasion and bargaining (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge and Macedo1999, 211). Similarly, there is no a priori definition of what counts as a public issue, but rather public spheres are the site in which citizens thematise aspects of their lived experiences to render them a matter of public interest (Benhabib Reference Benhabib1997: 17–19).

Empirical research on citizens’ attitudes towards deliberation has focused on instances of direct deliberation in citizens’ assemblies, town hall meetings or online (e.g., Gamson Reference Gamson1992; Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Cook and Delli Carpini2009; Minozzi et al. Reference Minozzi, Song, Lazer, Neblo and Ognyanova2020). However, despite the rapid spread of social media, public debate in contemporary democracies still occurs primarily through mediated communication, that is, through media organisations, political parties, interest groups and governmental agencies. Even though there is extensive research on citizens’ trust towards and satisfaction with these institutions, we do not know much about how citizens view their role in public debates and whether they think it matters for democracy.Footnote 1

Three discussions in the literature on democratic attitudes offer analytical insights that can help us elucidate citizens’ views about the public sphere: (1) whether citizens support democracy for instrumental or intrinsic reasons; (2) how experience with democratic institutions affects support for democracy and (3) which factors make citizens prioritise certain democratic practices and institutions over others.

Instrumental theories of democratic attitudes argue that citizens are more likely to express support for democracy if they are satisfied with its outputs. From this perspective, citizens who are on the losing side of democratic processes – for example, because they lose an election or because policies have a negative impact on their interests – are less likely to support democracy (Evans & Whitefield Reference Evans and Whitefield1995; Gilley Reference Gilley2009; Houle Reference Houle2009; Magalhães Reference Magalhães2014; Krieckhaus et al. Reference Krieckhaus, Son, Bellinger and Wells2014; Dahlberg et al. Reference Dahlberg, Linde and Holmberg2015). However, other authors find evidence of an opposite relationship: the more critical citizens are of their government's performance, the more likely they are to support democratic principles (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2018). Other scholars claim instead that citizens value democratic institutions for intrinsic reasons, independently from the outputs of democratic decision making. From that perspective, citizens are more likely to support democracy if democratic processes live up to certain normative ideals (Easton Reference Easton1975; Bratton & Mattes Reference Bratton and Mattes2001; Norris Reference Norris1999, Reference Norris2011; Qi & Shin Reference Qi and Shin2011; Doorenspleet Reference Doorenspleet2012; Magalhães Reference Magalhães2016). As long as citizens perceive democratic processes as fair and legitimate, they are more likely to be satisfied with (and, crucially, remain committed to) democracy, even if their preferred candidates are not elected and the policies they desire are not enacted (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Esaiasson Reference Esaiasson2011; Ezrow & Xezonakis Reference Ezrow and Xezonakis2011; Merkley et al. Reference Merkley, Cutler, Quirk and Nyblade2019).

A parallel debate is about whether experience with democratic institutions fosters democratic support. ‘Socialisation’ theories assert that citizens develop a ‘taste’ for democracy's rights and freedoms as they experience democratic institutions (Bratton & Mattes Reference Bratton and Mattes2001; Mishler & Rose Reference Mishler and Rose2002; Magalhães Reference Magalhães2014; Denemark et al. Reference Denemark, Mattes and Niemi2016). This means not only that democratic support should increase as the quality of democracy improves and persists over time, but it also implies that differences in support for democracy between social groups should also narrow down (Walker & Kehoe Reference Walker and Kehoe2013; Konte & Klasen Reference Konte and Klasen2016). Others argue instead that support for democracy follows a thermostatic logic: it grows when democracy is scarce, but it wanes as the quality of democracy increases (Claassen Reference Claassen2020).

Finally, citizens mean very different things when they claim to support democracy. This concern has inspired a growing body of research on citizens’ understandings of democracy (e.g., Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Sin and Jou2007; Schedler & Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007; Canache Reference Canache2012; Ferrín & Kriesi Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016; Ulbricht Reference Ulbricht2018). Most of this literature has focused on assessing the extent to which citizens view democracy in terms of a liberal model that emphasises free and fair elections, checks and balances and civil liberties, or associate democracy with radical, participatory or deliberative models that prioritise principles of social justice, direct popular participation or deliberation (Schedler & Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007; Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Sin and Jou2007; Ceka & Magalhães Reference Ceka, Magalhães, Ferrín and Kriesi2016; Heyne Reference Heyne2019). However, recent studies argue that citizens do not think about democracy in terms of coherent sets of principles and institutions that correspond to well‐defined ‘models of democracy’ (Hansen & Goenaga Reference Hansen and Goenaga2019; Werner et al. Reference Werner, Marien and Felicetti2020). Instead, these authors claim that citizens think pragmatically about democracy, prioritising political practices and institutions that empower them over those parts of the democratic system that privilege the influence of other actors.

In what follows, we draw on these debates to develop testable hypotheses about which groups are more likely to consider the public sphere important for democracy and how the quality of the public sphere in a country affects those views.

Theory: A problem‐based analysis of public spheres

The democratic functions of public spheres

Following Mark Warren's problem‐based approach to democracy, we start by asking “what kinds of problems a political system needs to solve to count as ‘democratic’” (Warren Reference Warren2017: 39), and how public spheres contribute to solving some of those problems. In representative democracies, the actors and institutions that constitute the public sphere provide voice to alternative perspectives and interests; they empower citizens to scrutinise and criticise the exercise of political power and they disseminate information on matters of public interest. By performing these normative functions, public spheres contribute to solve problems related to inclusion, accountability and publicity.

Voice: Inclusion – meaning that all citizens should be able to influence collectively binding decisions – is one of the main problems that political systems need to solve to count as democratic (Warren Reference Warren2017: 44). However, political inclusion cannot be limited to the authorisation of collective decisions (e.g., via elections or referenda), but citizens must also be able to influence the processes that define which issues are to be addressed through collectively binding decisions (i.e., agenda‐setting) and the processes that shape preferences over those decisions (i.e., collective preference and will formation). Public spheres provide tools for citizens to identify common experiences of injustice or domination, to present them as a matter of public interest that should be addressed by political authorities, and to influence the preferences of other citizens on those issues (Benhabib Reference Benhabib1997: 9–10; White & Ypi Reference White and Ypi2016: 58–61). In this way, public spheres empower citizens to have their preferences and interests voiced in public debates and thus contribute to solve problems of inclusion in processes of agenda‐setting and collective preference formation (Young Reference Young2002: 67). For example, labour parties and the working‐class press contributed to raise awareness about labour conditions and to introduce them in the political agenda in the nineteenth century. Similarly, twentieth‐century civil rights movements turned to the public sphere to reframe forms of injustice that were experienced by marginalised groups as matters of public interest (e.g., Lara Reference Lara1998; McCammon Reference McCammon2001). More recently, the MeToo and the Black Lives Matter movements offer examples of how the public sphere served to thematise issues that were privately experienced by large numbers of people – sexual harassment and police brutality – and to turn them into matters of general concern.

Critique: If democracy is understood as self‐rule, inclusion in political decision‐making needs to come with empowerments that enable citizens to hold public officials accountable (Warren Reference Warren2017: 44). In representative democracies, adversarial institutions such as competitive elections and constitutional checks and balances are the main ways in which citizens can hold authorities accountable. However, for elections and checks and balances to serve effectively as accountability mechanisms, citizens need to be able to publicly criticise government officials. Even if the evidence in favour of retrospective voting is contested (Lupia & McCubbins Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998; Achen & Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017), a vigilant public sphere can still prevent blatant abuses of power or outright disregard for voters’ preferences (Grimes Reference Grimes2013). If one takes a more optimistic perspective, robust public spheres can help voters clarify their interests and evaluate government performance accordingly (Chambers Reference Chambers2009: 341–342). Therefore, public spheres serve key monitoring functions that are necessary for the exercise of democratic accountability.

Information: Publicity represents another core principle of modern democracy (Fraser Reference Fraser1990: 58). Access to information is necessary for citizens’ enlightened understanding of public issues, for the formation of coherent political preferences, and consequently for any meaningful form of democratic self‐rule (Christiano Reference Christiano1996: 83–86). Hence, public spheres perform epistemic functions that are essential for democracy by producing, verifying and disseminating relevant information. Furthermore, the principle of publicity introduces a requirement of rationality into the exercise of political power because it demands government officials to justify collective decisions to the public. This not only represents a source of legitimacy for political power in post‐conventional societies (Habermas Reference Habermas1996: 151), but it may also lead to better outcomes (Landemore Reference Landemore2012).

In complex societies, no single actor or institution can single‐handedly carry out any of these functions, let alone all three of them. Rather, these functions are performed in different loci of the public sphere, through various political practices, and by a wide array of actors (Parkinson & Mansbridge Reference Parkinson and Mansbridge2012; Warren Reference Warren2017). To the extent that citizens are able to voice alternative perspectives, to monitor and criticise political power and to access information about matters of public interest, we can speak of more democratic public spheres.

Who cares about the public sphere?

Having established the normative functions that public spheres perform, we can now ask how important citizens consider those functions for democracy, and which citizens and under what circumstances are more likely to care about them. Rather than expecting citizens to form monolithic preferences about the public sphere as a whole, we argue that they develop differentiated views about the importance of each of its democratic functions.

Building on recent applications of problem‐based democratic theory to the study of political attitudes, we argue that citizens prioritise practices and institutions that they find particularly empowering (Hansen & Goenaga Reference Hansen and Goenaga2019) or that address democratic problems that they especially care about (Werner et al. Reference Werner, Marien and Felicetti2020). Since even facially neutral democratic practices and institutions interact with broader social inequalities in ways that privilege particular resources and interests over others, certain groups are likely to derive greater benefits from them and thus to consider those practices more important parts of the democratic system. This, of course, is also the case for the communicative practices that constitute the public sphere. Theorists of deliberative democracy have advanced distinct claims about the relative benefits that individuals derive from public discussion depending on their cultural capital (e.g., Fraser Reference Fraser1990), experiences of discrimination (e.g., Young Reference Young2002) and dissatisfaction with government performance (e.g., Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970). These claims yield concrete expectations about which groups are more likely to prioritise the different democratic functions of the public sphere.

First, citizens may possess material or cultural assets that increase their political influence through communicative interactions. Critics of deliberative democracy have pointed out how public deliberation requires specific performances, cultural codes and linguistic registers that make certain groups more likely to participate, to be listened and to influence the outcomes of public deliberation (Fraser Reference Fraser1990: 63–64). Hence, actors who are rich in cultural capital have an advantage when it comes to shaping public debates and using public information to advance their interests. Therefore:

H1: Higher levels of education should be associated with greater importance of all democratic functions of the public sphere.

Second, some citizens tend to be particularly concerned about certain democratic problems and thus are more likely to care about those parts of the democratic system that help them address those issues. For instance, cultural or sexual minorities are likely to be especially concerned about problems of inclusion (Young Reference Young2002). Even if their votes count the same as the votes of other citizens, members of these groups are likely to perceive that they are not fully included in democratic decision making if the issues they care about do not enter the political agenda (Christiano Reference Christiano1996: 90). Therefore, we expect members of marginalised groups to prioritise democratic practices and institutions that empower them to voice their group‐specific demands in ways that can garner broader public support. Hence:

H2: Members of cultural and sexual minorities should assign greater importance to those aspects of the public sphere related to voice.

Different democratic practices and institutions are also likely to matter more depending on whether one is satisfied with governmental performance. As noted above, research on democratic attitudes finds that output satisfaction is associated with greater support for democracy (Magalhães Reference Magalhães2014; Krieckhaus et al. Reference Krieckhaus, Son, Bellinger and Wells2014; Dahlberg et al. Reference Dahlberg, Linde and Holmberg2015). However, there are reasons to expect dissatisfied citizens to care more about those practices and institutions that empower them to hold public officials accountable for underperforming (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2018). In contemporary representative democracies, accountability rests on both exit and voice (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970).Footnote 2 For any individual citizen, exit – for example, by not voting for incumbents in the next election – is a weak way of holding public officials accountable, especially if it requires large numbers of voters to withdraw their support for incumbents to fear losing power (Dowding et al. Reference Dowding, John, Thanos and Van Vugt2000: 470). Instead, the ability to scrutinise, criticise and demand authorities to justify themselves to the public, gives dissatisfied citizens the opportunity to convince others to withdraw their support from incumbents and use the threat of collective exit as an effective accountability mechanism. Consequently:

H3: Citizens dissatisfied with the government should assign greater importance to public criticism and access to information.

Previous research shows that citizens develop higher levels of support for democracy the more they experience its benefits (Bratton & Mattes Reference Bratton and Mattes2001; Denemark et al. Reference Denemark, Mattes and Niemi2016; Heyne Reference Heyne2019). If that is the case, citizens should develop more differentiated views about the importance of the public sphere in contexts in which it is an effective source of voice, critique and information. Conversely, if the public sphere fails to provide citizens with those democratic goods, actors should be less likely to find it empowering and consequently differences between groups should be narrower. Therefore, we expect that:

H4: Differences between social groups in their views about the importance of the public sphere should widen as the quality of the public sphere improves.

In some instances, inequalities in the benefits that different groups derive from the public sphere may be a corrective to broader power asymmetries. This is the case, for example, for disadvantaged minorities that may find in the public sphere opportunities to formulate group‐specific experiences of injustice as matters of public interest that would otherwise not be addressed through other democratic institutions. In other contexts, the fact that certain groups are particularly empowered by the communicative practices of the public sphere may magnify political inequalities – for example, by privileging the participation of cultural and economic elites. This is one of the reasons why advocates of deliberative democracy propose mini‐publics that are explicitly designed to tackle those inequalities as complements to the public sphere (e.g., Felicetti et al. Reference Felicetti, Niemeyer and Curato2016; Beauvais & Warren Reference Beauvais and Warren2019). It is also why democratic theorists often highlight the role of non‐deliberative institutions in counteracting the power asymmetries inherent to communicative interactions (Parkinson & Mansbridge Reference Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 6–7; Warren Reference Warren2017: 48).

Data and methods

To evaluate these hypotheses, we analyse individuals’ views about the importance of specific practices and institutions associated with the public sphere in 29 predominantly European countries. The data come from the module on citizens’ understandings of democracy from Wave 6 of the ESS (Ferrín & Kriesi Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016). These questions were only asked on Wave 6, so we cannot look at changes over time. The evidence presented here is therefore purely correlational. However, the ESS6 data have the advantage of having been collected in 2012, prior to the Brexit and Trump campaigns that popularised concerns about the erosion of public spheres in advanced democracies. In that regard, the data offer a representative snapshot of European's views about these issues before they became widely politicised.

The ESS6 questionnaire asked respondents to rate on a scale from 0 to 10 how important they considered various practices and institutions for democracy, ranging from free and fair elections to governments reducing income inequality. Six of these items explicitly referred to practices that involve propositional forms of communication (i.e., ‘offer alternatives’, ‘discuss’, ‘criticise’, ‘provide information’, ‘explain’):

Voice:

Different political parties offer clear alternatives to one another.

Voters discuss politics with people they know before deciding how to vote.

Critique:

Opposition parties are free to criticise the government.

The media are free to criticise the government.

Information:

The media provide citizens with reliable information to judge the government.

The government explains its decisions to voters.

These variables relate to the three normative functions of voice, critique and information and span the main institutional loci of public spheres in contemporary democracies, including parties, media, government and informal networks.

To examine citizens’ views about the importance of voice, we rely on two indicators that refer to different channels for the expression of alternative interests and perspectives in public debates. First, citizens may care that their views are voiced in public debates, even if they do not express them directly. The party system plays a crucial role in this kind of mediated deliberation, as two of the core democratic functions of political parties are (1) to formulate the preferences and interests of their supporters as a matter of general concern (White & Ypi Reference White and Ypi2016: 59–61), and (2) to articulate distinct political programs that give voice to the relevant variety of interests and preferences present in society (Christiano Reference Christiano1996: 188). Hence, our first indicator for voice evaluates how important it is for citizens that parties offer clear alternatives so that different interests and preferences enter the political agenda. Unfortunately, the ESS module did not include a question about the importance of having a wide diversity of voices in the media, which represents the other major institutional space for voice through mediated deliberation (Norris Reference Norris2009: 18–19). Second, to measure citizens’ views about direct deliberation, we include an indicator that measures the importance of political discussion in informal networks. Those discussions can be an important site of preference formation (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge and Macedo1999). For example, experimental research shows that informal face‐to‐face conversations can change negative attitudes against minorities (Broockman & Kalla Reference Broockman and Kalla2016; Kalla & Broockman Reference Kalla and Broockman2020).

To measure the importance of public criticism, we draw on indicators that focus on opposition parties and the media. In addition to voicing alternative viewpoints, opposition parties scrutinise and criticise the goals and performance of those in power. This is the main way in which electoral competition can lead to popular accountability in representative democracies. Similarly, the media are expected to monitor public officials (as captured by the classical expression of the ‘fourth estate’), to investigate and denounce acts of incompetence or malfeasance and to give citizens platforms to publicly criticize authorities (Norris Reference Norris2009: 16–17).

To evaluate views about the epistemic functions of the public sphere, our first indicator measures the importance that the media disseminates reliable information on matters of general interest (Norris Reference Norris2009: 17–18). However, citizens may not only care about what the government does, but also about why it does it. Therefore, our second indicator focuses on public justification by government officials as another kind of epistemic good provided by the public sphere (Christiano Reference Christiano1996: 188).

Previous research has used the ESS6 data to, for example, examine differences in how men and women understand democracy (Hansen & Goenaga Reference Hansen and Goenaga2019), to explore citizens’ attitudes towards direct participation via referendums (Werner et al. Reference Werner, Marien and Felicetti2020) and to analyse the extent to which European citizens embrace models of liberal, social‐democratic or direct democracy (Ferrín & Kriesi Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016; Kriesi Reference Kriesi2018; Heyne Reference Heyne2019). None of these studies, however, has been primarily concerned with attitudes towards the public sphere. In fact, the latter group of studies collapse these indicators as part of an overall measure of support for liberal democracy. By analysing separately the practices and institutions that constitute the public sphere, our goal is not to evaluate citizens’ overall support for a liberal conception of democracy, but to assess whether citizens consider public deliberation a central component of democracy and to identify which groups are more likely to care about the different democratic functions of public debate.

In our analyses, the main independent variables are education, cultural and sexual minority status and dissatisfaction with government outputs. To measure education, we rely on the ESS harmonised variable that divides educational levels into eight categories: (1) less than lower secondary (reference category); (2) lower secondary; (3) low‐upper secondary; (4) high‐upper secondary; (5) vocational; (6) Bachelor's degree; (7) Master's degree or higher and (8) other. We treat education as a categorical variable since the values for vocational and other forms of education do not follow the same ordinal structure as the other categories.

To examine the views of members of cultural and sexual minorities, we look at whether respondents reported experiences of discrimination on the basis of, on the one hand, their race, ethnicity, religion or nationality, and, on the other hand, their sexual orientation.Footnote 3 By foregrounding experiences of discrimination, these variables identify cultural minorities consistently across countries even though certain racial, ethnic, religious or national groups may be marginalised in some contexts but not others. This advantage comes at the expense of a higher propensity for social desirability bias, as respondents might be more reluctant to acknowledge experiences of discrimination in contexts where discrimination is more extreme.

To measure citizen dissatisfaction, we rely on two questions that asked respondents to score their satisfaction with governmental performance and with the state of the economy on a scale from 0 to 10. We invert the scales so that higher values indicate more dissatisfied citizens and calculate the mean for both questions to produce a single indicator of ‘output dissatisfaction’.

To examine individual‐level correlates of citizens’ views about the public sphere (H1 to H3), we run two different sets of OLS models with country fixed‐effects, post‐stratification and population survey weights and standard errors clustered by country. All the models control for age, gender, income, immigrant background and political ideology. The first set of models estimates differences between social groups in how important they consider each aspect of the public sphere. Since certain groups may be more likely to assign greater importance to most aspects of democracy, the second set of models includes as a control variable the mean value of respondents’ scores for the importance of all other aspects of democracy.Footnote 4 These models thus represent a more stringent test of H1 to H3.

To analyse how the characteristics of the public sphere in the country affect citizens’ views about its importance (H4), we build an index of the quality of the public sphere between 2000 and 2012 using data from the Varieties of Democracy (V‐Dem) Project (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Agnes, Nazifa, Lisa, Haakon, Garry, Nina, Laura, Valeriya, Juraj, Römer, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig and D.2020). The index is a factor score of ten indicators that evaluate specific aspects of the public sphere based on expert assessments. To measure the extent to which parties offer alternatives, we use a measure of whether national political parties have distinct party platforms (v2psplats). To capture the extent to which voters discuss politics, we rely on V‐Dem's indicator for engaged public (v2dlengage). To measure the extent to which parties are free to criticise the government, we use the indicator for opposition parties’ autonomy (v2psoppaut). For the extent to which the media is free to criticise the government, we draw on four indicators: government censorship effort (v2mecenefm), how many print and broadcast media outlets are critical of the government (v2mecrit), harassment of journalists (v2meharjrn) and media self‐censorship (v2meslfcen). To examine the extent to which the media provides reliable information, we use assessments of media bias (v2mebias) and media corruption (v2mecorrpt). Finally, to measure whether the government explains decisions to voters we draw on V‐Dem's indicator on reasoned justification (v2dlreason). All the mixed‐effects models control for the country's mean level of democracy and economic development between 2000 and 2012 and include post‐stratification weights.

Appendix A in the Supporting Information presents descriptive statistics and coding information for all the variables. Appendix B in the Supporting Information reports additional models that evaluate, separately, satisfaction with government and satisfaction with the economy, as well as models that control for political interest, interpersonal trust and trust in institutions. Appendix C in the Supporting Information presents mixed‐effects models that examine the conditional effects of each aspect of the public sphere.

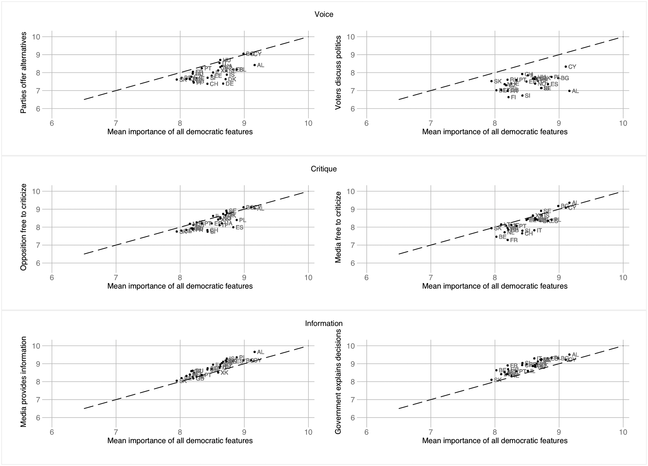

Figure 1 plots citizens’ views about the importance of the public sphere relative to other features of democracy in the 29 countries. The y‐axes measure the country‐means for each of the six public sphere indicators. The x‐axes measure the mean score for twelve democratic characteristics: the six indicators of the public sphere plus free and fair elections, rights of minority groups, legal equality, electoral accountability, direct participation and judicial checks on government authority. Dots above the diagonal lines indicate that citizens on average prioritise that aspect of the public sphere over other democratic features, while dots below the diagonal lines indicate that citizens in that country tend to consider that aspect of the public sphere less important than other democratic practices and institutions.

Figure 1. Importance of aspects of public spheres relative to other democratic features.

We observe that citizens across countries hold similar views about the relative importance of the different functions of the public sphere. The indicators related to voice tend to receive lower scores compared to other democratic features, whereas the indicators related to critique are more or less at the mean, while the epistemic indicators are consistently among the most important aspects of democracy. Additional figures presented in Appendix A (in the Supporting Information) show that, in most countries, citizens consider access to reliable information and public justification by government officials as important for democracy as free and fair elections, legal equality or protection of minority rights.

Results

Individual‐level factors

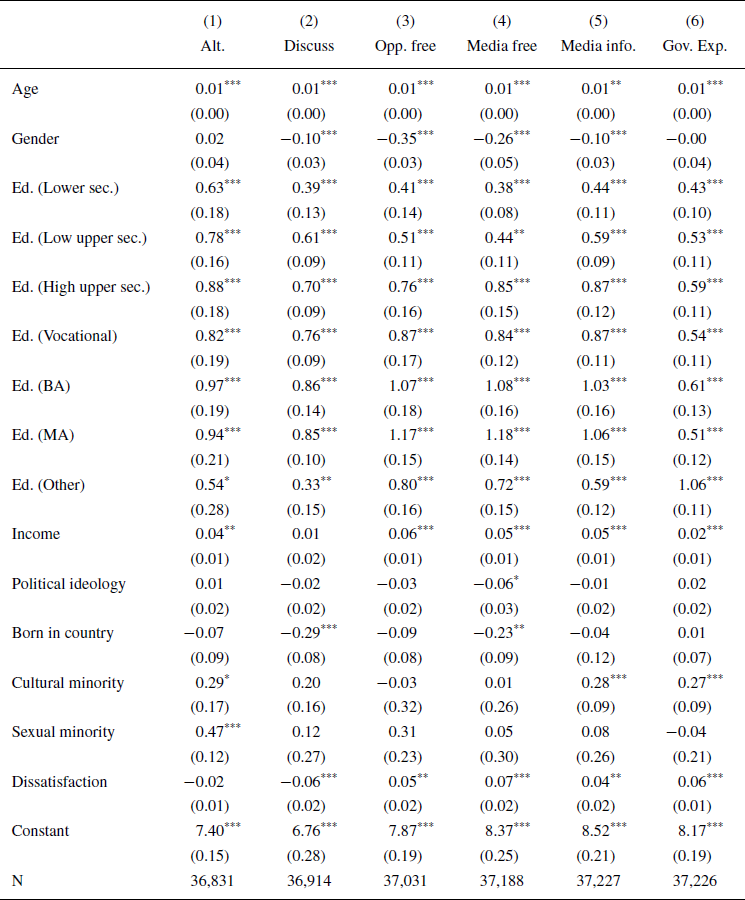

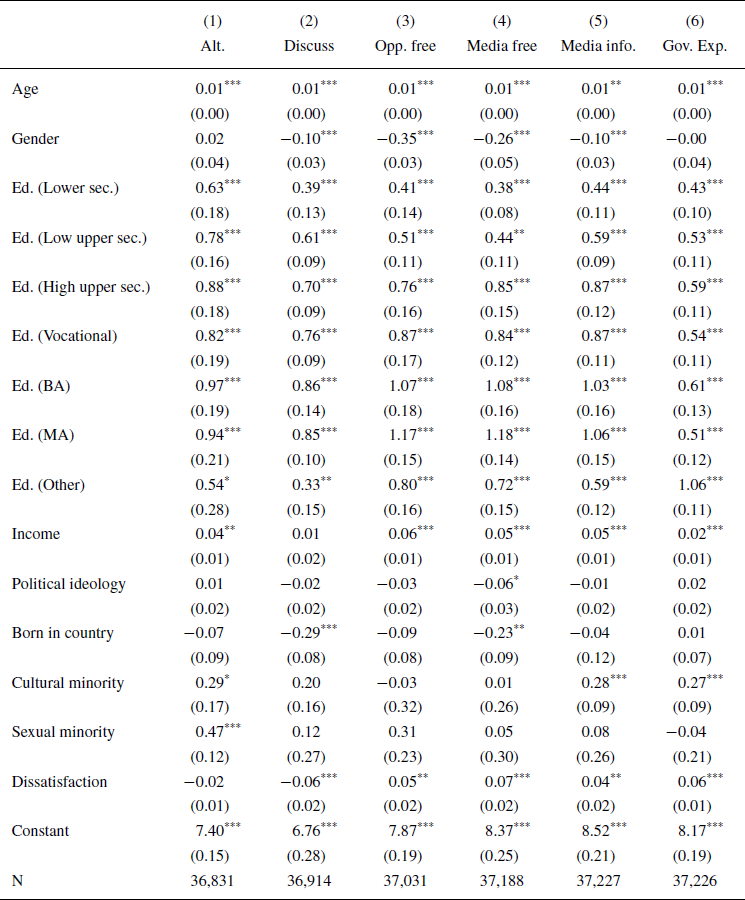

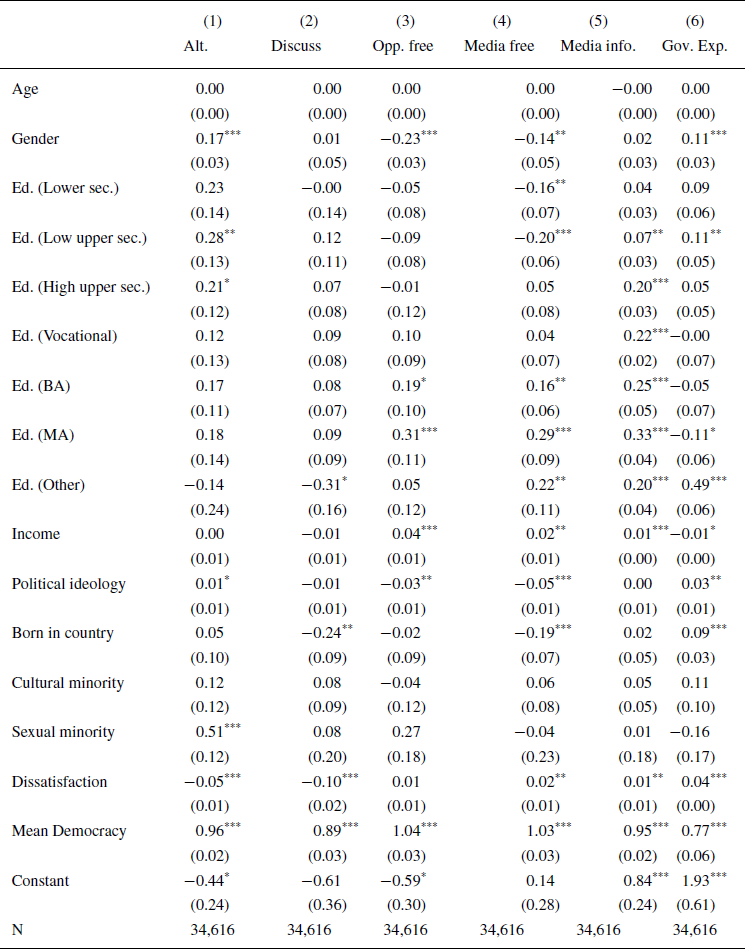

Table 1 presents the results of statistical models that examine respondents’ views about the importance of the different functions of the public sphere. Models 1 and 2 focus on indicators related to voice through mediated deliberation via political parties (Model 1) and through direct deliberation in informal discussions among voters (Model 2). Models 3 and 4 refer to public criticism, as it is carried out by opposition parties (Model 3) and the media (Model 4). Models 5 and 6 focus on the epistemic functions of public spheres, based on the importance that the media provides reliable information (Model 5) and the importance that the government explains its decisions to voters (Model 6). All of these models include country‐fixed effects and population and post‐stratification weights. Standard errors are clustered by country.

Table 1. Importance of different aspects of the public sphere

Note: All models include country fixed effects and population and post‐stratification weights. Standard errors clustered by country. *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Education is consistently associated with greater importance of all aspects of the public sphere, as expected by H1. The coefficients report the difference in respondents’ views relative to the baseline category: respondents with less than lower secondary education. All the coefficients for education are positive and statistically significant at the 0.01 level and increase in size as we move up to higher levels of education. Respondents with lower secondary education report scores that are 0.4 to 0.6 points higher than respondents without a secondary education in a scale from 0 to 10. Having a BA degree is associated with scores that are over one full point higher compared to the baseline category.

Consistent with H2, respondents who claimed to experience discrimination on the basis of their membership to a cultural or sexual minority tend to give scores that are between 0.2 and 0.6 points higher for those aspects of the public sphere related to voice, at least when it comes to the importance that parties offer alternatives (Model 1). However, the coefficients for cultural and sexual minorities are positive but smaller and not statistically significant in Model 2, which estimates the importance of informal discussion. It could be the case that the challenges of direct inter‐personal deliberation in informal networks are especially high for members of marginalised groups (Mendelberg & Oleske Reference Mendelberg and Oleske2000; Beauvais Reference Beauvais2020), and thus they may see mediated deliberation through political parties as a more important channel of voice. Such challenges may also explain the significant coefficients in Models 5 and 6, which suggest that members of cultural minorities are also more likely to care about access to epistemic goods.

H3 argued that dissatisfied citizens are more likely to prioritise public criticism and access to information. Models 1 and 2 suggest that greater dissatisfaction with the economy and the government is not associated with higher regard for voice (Models 1 and 2). Conversely, Models 3–6 show that more dissatisfied citizens are more likely to report higher scores for public criticism and access to information. The importance of these aspects of the public sphere increases by approximately 0.1–0.2 points for every standard deviation in the level of dissatisfaction. To put these values in perspective, highly dissatisfied respondents (a score of 10 in the dissatisfaction index) on average report scores that are almost one full point higher than those of satisfied citizens (a score of 0 in the dissatisfaction index) regarding the importance of critical media (Model 4) and government justification (Model 6). These differences are comparable in magnitude to those between respondents with less than secondary education and respondents holding a BA degree.

The models in Table 2 reproduce a similar setup but now control for the importance that respondents assign to the other procedural indicators of democracy included in the survey. The large and statistically significant coefficients for Mean Democracy indicate that respondents who consider the public sphere important for democracy tend to assign higher values to other democratic practices and institutions as well. However, these models also provide evidence that more educated citizens, sexual minorities and dissatisfied respondents on average emphasise the importance of the different functions of the public sphere even after controlling for their views about other aspects of democracy.

Table 2. Relative importance of different aspects of the public sphere

Note: All models include country fixed effects and population and post‐stratification weights. Standard errors clustered by country. *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Respondents with a BA degree or higher are more likely to prioritise critique (Models 3 and 4) and access to reliable information through the media (Model 5) but not public justification (Model 6). While the results presented in Table 1 are consistent with H1 and with previous studies showing that more educated citizens tend to consider more important most aspects of democracy (Ceka & Magalhães Reference Ceka, Magalhães, Ferrín and Kriesi2016), Table 2 shows that differences based on education are especially acute for democratic practices that disproportionately empower those with cultural capital, such as public criticism and access to information.

Once we control for their views on other aspects of democracy, the coefficient for cultural minorities is no longer statistically significant in Model 1. This suggests that, even though members of cultural minorities tend to care more about parties voicing alternatives than the rest of the population (as seen in Table 1), this is also the case for other democratic practices. Conversely, in line with H2, Model 1 in Table 2 shows that members of sexual minorities are more likely to emphasise the importance of diverse party systems even after controlling for their views on other parts of the democratic system. These results provide robust empirical evidence behind claims commonly made by democratic theorists about the special role that pluralistic public spheres perform for the inclusion of marginalised groups (Young Reference Young2002).

Finally, even after accounting for respondents’ attitudes towards other democratic institutions and in line with H3, highly dissatisfied respondents report scores for critical media (Model 4) and the two epistemic indicators (Models 5 and 6) that are up to 0.4 points higher than those of highly satisfied respondents. These differences are again comparable in size to the differences between the least educated respondents and those with post‐graduate degrees in Table 2. These results go in line with Kriesi (Reference Kriesi2018: 71–72), who finds that dissatisfied citizens tend to express greater support for liberal democracy. However, these coefficients also highlight the importance of looking beyond composite measures of democratic models. Even if all six aspects of democracy included in the analyses are commonly viewed as components of liberal democracy, we find that dissatisfaction with government performance is associated with greater concern for practices related to accountability (such as public criticism and access to information), but with lower importance of those aspects related to voice (as indicated by the negative and statistically significant coefficients in Models 1 and 2). These results provide further support to the claim that citizens develop differentiated views about specific practices and institutions based on the normative functions they serve rather than on the basis of support for abstract models of democracy.

Tables 1 and 2 provide insight into why the epistemic indicators receive very high scores in most countries (see Figure 1). Economic and cultural elites and dissatisfied citizens tend to consider the epistemic functions of the public sphere among the most important aspects of democracy. The effects of government dissatisfaction are particularly important in this regard, since the distribution is skewed towards higher levels of dissatisfaction in most countries.

At the same time, while the indicators for voice tend to be considered among the least important aspects of democracy, our analyses show that some disadvantaged groups – namely, cultural and sexual minorities – emphasise the importance that parties voice alternative perspectives. These results underscore our claim that different groups tend to value more those democratic practices and institutions that they find particularly empowering and that this has important normative implications for democratic theory.

Country‐level effects

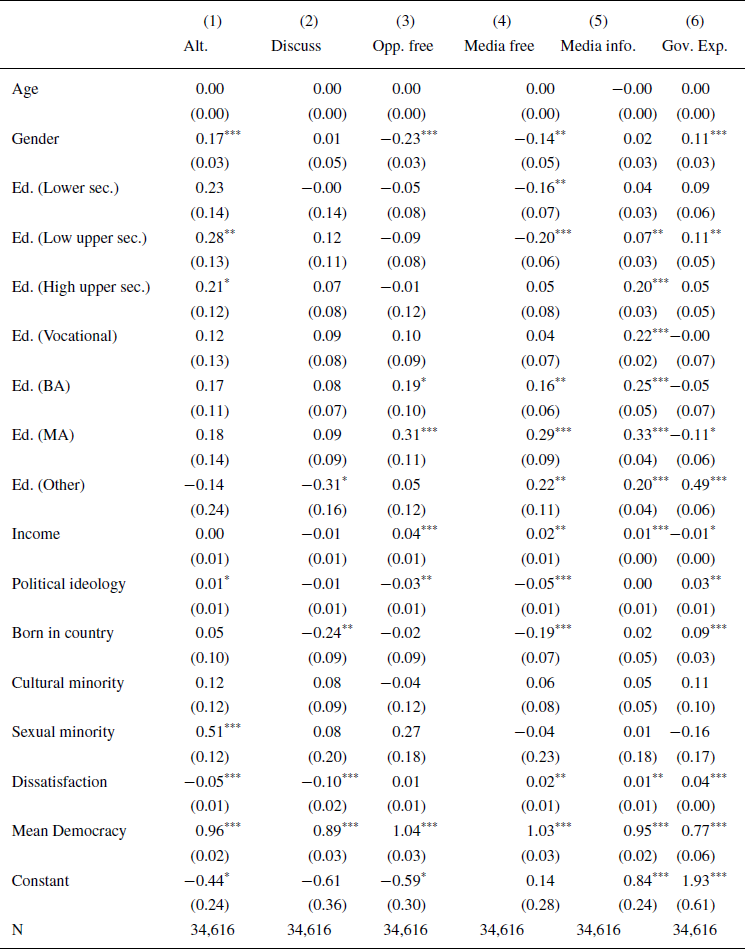

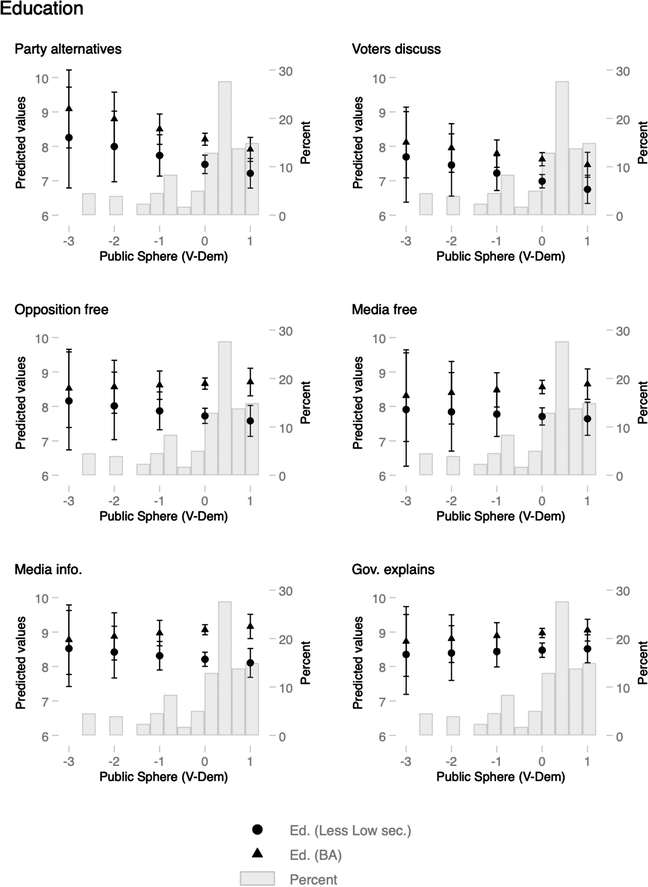

H4 argued that differences between social groups should be wider in countries with more democratic public spheres. To evaluate this claim, we run mixed‐effect models in which we interact individual‐level characteristics with a country‐level measure of the public sphere. As a reminder, the public sphere index is a factor score of ten V‐Dem variables measuring institutional characteristics of the public sphere in the country from 2000 to 2012. All the models control for the overall quality of democracy and economic development, as well as the same individual‐level covariates from Table 1. We only report here predicted values for the main independent variables, but full regression tables are presented in Appendix C (in the Supporting Information).

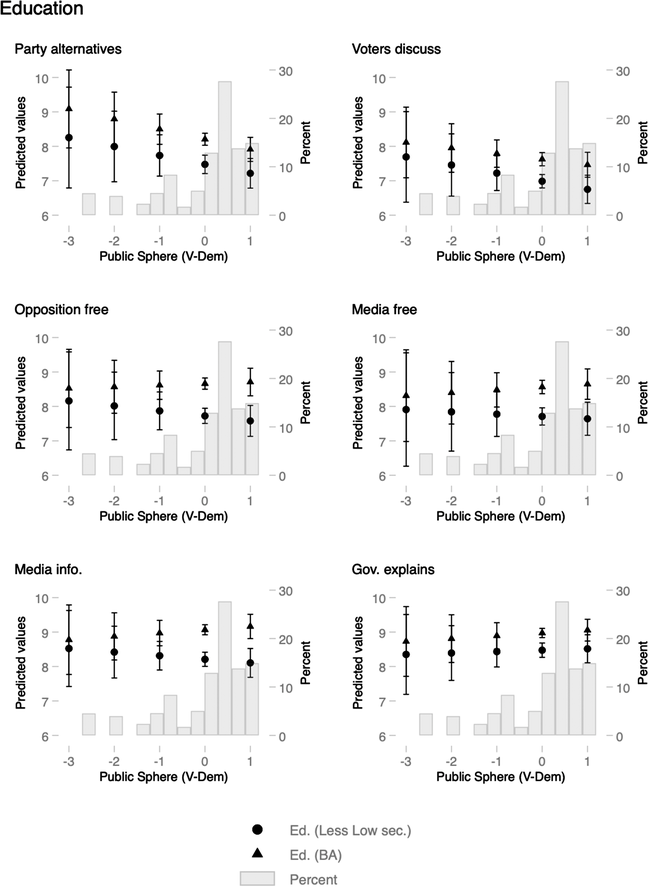

Figure 2 presents the predicted importance of each of the six public sphere indicators for respondents with lower secondary education and for respondents with a BA degree at different values of the public sphere index. Consistent with H4, differences between these two groups are wider as the quality of the public sphere improves in the country. At lower scores of the public sphere index, the confidence intervals for education are very large. However, at higher scores, the predicted values are more precisely estimated and show clearer differences between respondents at different levels of education. This is especially the case in the models for public criticism. The results go in line with the expectation that, as the public sphere becomes a more effective vehicle of political influence, highly educated citizens that disproportionally benefit from public debate are more likely to deem it important for democracy.

Figure 2. Predicted importance of different aspects of the public sphere for different levels of education at different values of the public sphere index.

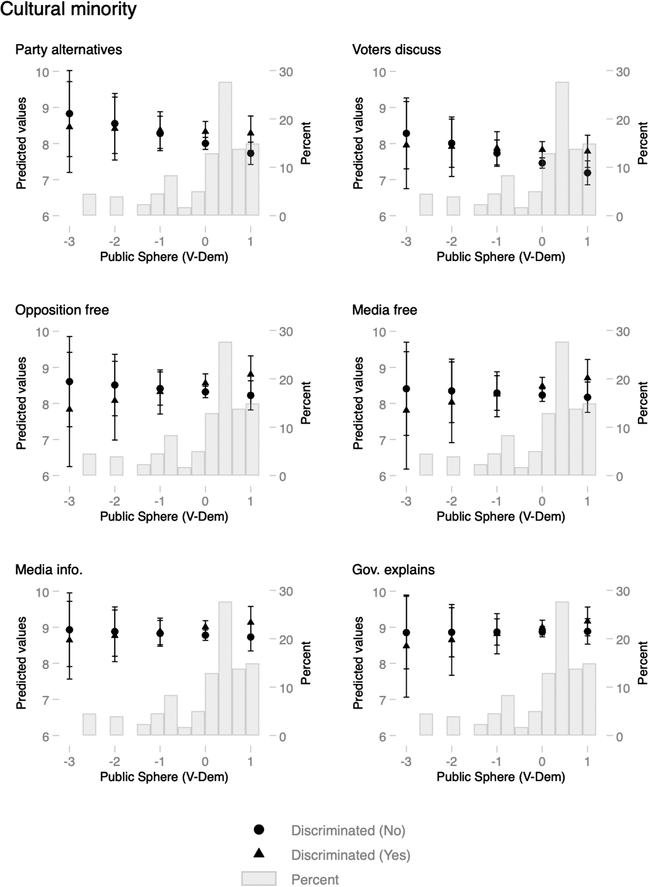

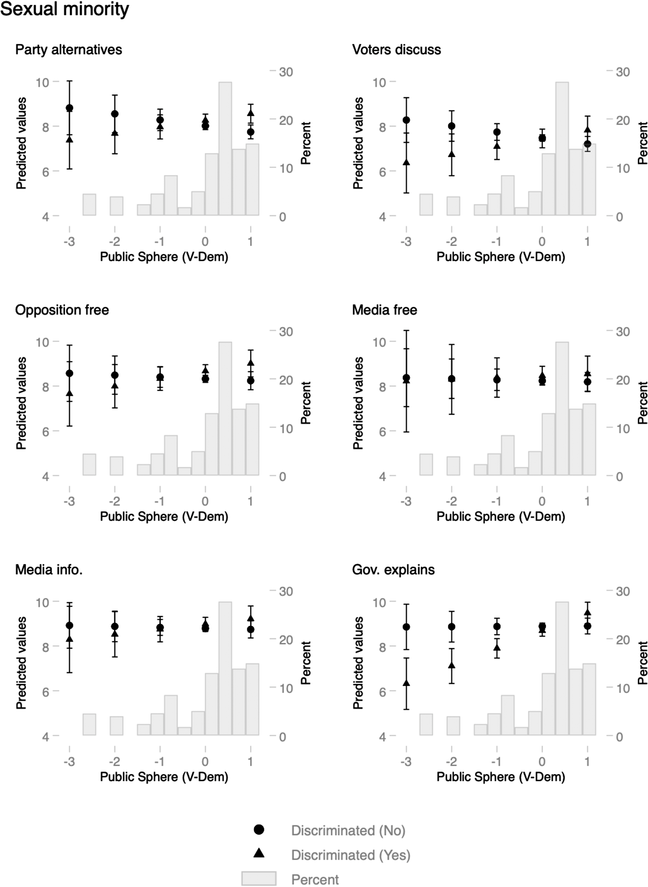

Figure 3 provides some indication that members of cultural minorities also care more about parties offering alternatives in countries with more democratic public spheres. Even though the confidence intervals partly overlap, the point estimates for each group move apart at higher values of the public sphere index. Figure 4 shows clearer evidence that members of sexual minorities develop more differentiated views about the importance of parties voicing distinct alternatives in countries with more democratic public spheres but not for other aspects of public deliberation. These findings support H4.

Figure 3. Predicted importance of different aspects of the public sphere by cultural minority status at different values of the public sphere index.

Figure 4. Predicted importance of different aspects of the public sphere by sexual minority status at different values of the public sphere index.

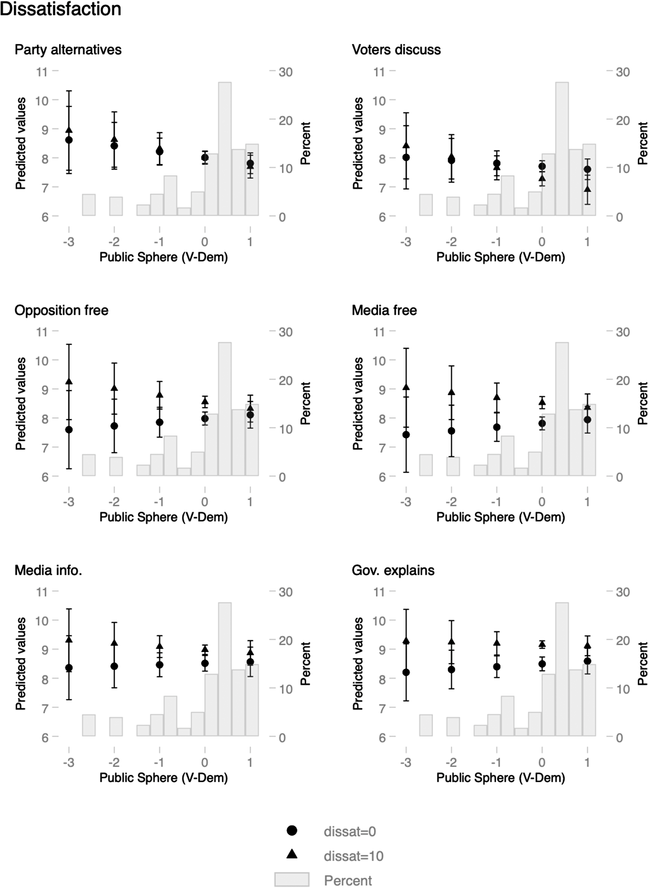

Finally, Figure 5 shows that differences between satisfied and dissatisfied citizens tend to disappear in countries with more democratic public spheres. Dissatisfied citizens tend to care deeply about public criticism and access to information in most contexts, but there is more variation among satisfied citizens depending on the quality of the public sphere. This pattern is clearer when we analyse separately the conditional effects of the monitoring and epistemic aspects of national public spheres (Figure C4 in Appendix C of the Supporting Information). One plausible interpretation is that, in countries with more democratic public spheres, satisfied citizens may associate good governmental performance with their ability to hold public officials accountable, and thus assign greater importance to public criticism and access to information. Conversely, in countries with more restricted public spheres, those who are satisfied with the government are less likely to associate good government performance with accountability and may instead see public criticism as a nuisance to effective leadership. Hence, we observe greater differences between satisfied and dissatisfied citizens in those contexts. Even if these results go against the expectations of H4, they are consistent with the claim that citizens care more about the public sphere if they perceive that they benefit from those practices and institutions.

Figure 5. Predicted importance of different aspects of the public sphere for satisfied and dissatisfied respondents at different values of the public sphere index.

Conclusion

This article has examined citizens’ views about the importance of the public sphere in 29 European countries. We have argued that citizens tend to care more about those aspects of the public sphere that they find particularly empowering or that help them address democratic problems that are especially important to them. The statistical analyses show that more educated respondents are more likely to consider all three functions of public spheres important for democracy, particularly those that privilege cultural capital, such as public criticism and access to information. Members of cultural and sexual minorities are more likely to emphasise those parts of the public sphere that give voice to alternative perspectives, while dissatisfied citizens are more likely to prioritise the critical and epistemic functions that underpin vertical accountability. The multi‐level models indicate that differences based on education and minority status are wider as the quality of the public sphere improves, while the views of satisfied and dissatisfied citizens tend to converge in more democratic public spheres.

These findings are based on a snapshot of European public opinion in 2012, before concerns about ‘fake news’, targeted advertising and echo chambers became widespread. Further research could examine whether these relationships have changed as the quality of public debate has become a salient political issue. The analyses of country‐level effects also suggest new paths for research regarding how changes in the quality of national public spheres have affected democratic attitudes. Recently, public spheres seem to have become more inclusive of alternative perspectives in most democracies. However, as a larger number of actors and viewpoints have been able to participate in public debates, it has become more difficult for citizens to discriminate reliable from unreliable information. What has been the impact of such trends on democratic attitudes? Has the opening of public spheres strengthened democratic support among minorities? Has the decline in the epistemic functions of public spheres undermined support for democracy among those who are dissatisfied with government performance? Finally, the evidence presented here has been purely correlational. A next step will be to examine the causal mechanisms that make certain groups more likely to prioritise particular functions of the public sphere. For example, is it really the case that minorities tend to value more pluralistic party systems because they see them as effective channels to introduce group‐specific demands to the political agenda?

We conclude by highlighting two implications of these results for research on democratic attitudes and democratic theory. First, our analyses indicate that citizens develop differentiated views about the importance of specific practices and institutions depending on the extent to which those aspects of the democratic system empower them to participate in collective decision making. These findings illustrate how the shift from model‐based to problem‐based approaches to democracy can yield new insights about how citizens think about democracy and which aspects of democracy they value most.

Second, procedural theories of democracy tend to see public spheres as at best ancillary institutions to competitive elections and the rule of law. Moreover, the shortcomings of ‘actually existing’ public spheres have pushed scholars to denounce ideals of public reason as unrealistic and even to advocate for forms of epistocracy that overtly reject public debate. Against those claims, we have shown that citizens consider aspects of the public sphere central to democracy, and that disadvantaged and dissatisfied citizens particularly care about the democratic functions of public deliberation. If we wish to develop theories of democracy that meet citizens’ normative expectations, we should then place public debate at their centre. This means, at a conceptual level, pushing procedural theories of democracy to think about the public sphere, along with competitive elections and legal equality, as a necessary component of democratic legitimacy. Similarly, at an empirical level, we should be devoting as much effort to understand the institutional characteristics that enable the public sphere to perform its democratic functions as we have put into understanding the institutional foundations of elections and the rule of law.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project is funded by a ‘Society's Big Questions’ Fellowship from the Swedish Royal Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities. The author thanks the participants of the Comparative Politics Lunch Seminar at Lund University and three anonymous reviewers for thoughtful comments on previous versions of this article.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1. Individual‐level variables

Table A2. Individual‐level variables (categorical)

Table A3. Country‐level variables

Figure A1. Importance of democratic characteristics by country.

Table B1. Sparse models using only satisfaction with government

Table B2. Sparse models using only satisfaction with the economy

Table B3. Sparse models, relative importance, looking only at satisfaction with government

Table B4. Sparse models, relative importance, looking only at satisfaction with the economy

Table B5. Models controlling for other political attitudes

Table B6. Models controlling for other political attitudes, relative importance

Table C1. Random intercept model (public sphere indicator)

Table C2. Cross‐level interaction (education × public sphere index)

Table C3. Cross‐level interaction (cultural minority × public sphere index)

Table C4. Cross‐level interaction (sexual minority × public sphere index)

Table C5. Cross‐level interaction (dissatisfaction × public sphere index)

Table C6. Random intercept model (disaggregate country‐level features of public sphere)

Table C7. Cross‐level interaction (education × specific public sphere features)

Table C8. Cross‐level interaction (cultural minority × specific public sphere features)

Table C9. Cross‐level interaction (sexual minority × specific public sphere features)

Table C10. Cross‐level interaction (dissatisfaction × specific public sphere features)

Figure C1. Predicted values for different levels of education and specific public sphere features.

Figure C2. Predicted values for cultural minority status and specific public sphere features.

Figure C3. Predicted values for sexual minority status and specific public sphere features.

Figure C4. Predicted values for dissatisfaction with government and specific public sphere features.

Supplementary Materials