Recovery Colleges are recovery-focused, adult education interventions supporting people experiencing mental health challenges. The colleges offer courses, sessions and workshops designed to foster improved mental well-being and support recovery. Reference Thornhill and Dutta1,Reference Perkins, Meddings, Williams and Repper2 The Recovery College approach places emphasis on co-production, Reference Crowther, Taylor, Toney, Meddings, Whale and Jennings3 referring to people with lived experience of mental health issues being active agents in contributing to all elements of the college, including operation, curriculum development and quality assurance. Reference Thornhill and Dutta1 The courses the colleges provide are co-produced, meaning that they are designed and delivered by those with lived experience of mental health challenges (known as peer tutors) and those with subject-matter expertise, e.g. mental health professionals. The first Recovery College opened in South West London in 2009. Reference Perkins, Repper, Rinaldi and Brown4 In 2021, there were 221 Recovery Colleges in operation across 28 countries, Reference Kotera, Ronaldson, Hayes, Hunter-Brown, McPhilbin and Dunnett5 including 88 in England. Reference Hayes, Camacho, Ronaldson, Stepanian, McPhilbin and Elliott6 There is increasing evidence of benefits for students attending the colleges Reference Allard, Pollard, Laugharne, Coates, Wildfire-Roberts and Millward7 including positive impact on goal achievement, increased knowledge of self-management and reductions in service use. Reference Perkins, Repper, Rinaldi and Brown4,Reference Perkins and Repper8,Reference Bourne, Meddings and Whittington9 The societal benefits of Recovery Colleges have been evidenced where mental health staff co-running the college courses were seen to develop an enhanced appreciation for co-production as well as less stigmatising perceptions towards people using mental health service. Reference Crowther, Taylor, Toney, Meddings, Whale and Jennings3 Furthermore, collaborations with third-sector organisations (such as mental health charities), expand their reach and positively influence public attitudes towards mental health. Reference Crowther, Taylor, Toney, Meddings, Whale and Jennings3 Psychiatrists have identified how co-production and power sharing within Recovery Colleges can contribute to a culture of parity between qualified mental health professionals and users of the service. Reference Collins, Shakespeare and Firth10

Recovery College heterogeneity

While Recovery Colleges share a set of principles in relation to recovery and social inclusion, including adult education and co-production, they are highly varied institutions. In order to establish what constitutes a Recovery College, a number of approaches to consistency have been developed. First, Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change (Imroc), a national initiative fostering a recovery-oriented approach within mental health services, identifies six underpinning principles for Recovery Colleges: educational, co-produced, strengths-based, person-centred, inclusive and community-focused. Reference Perkins, Meddings, Williams and Repper2,Reference Thompson, Simonds, Barr and Meddings11 Second, the key characteristics of Recovery Colleges are identified in the widely-used RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure, a 12-item quantitative assessment of the extent to which Recovery Colleges are organised according to core recovery principles. Reference Toney, Knight, Hamill, Taylor, Henderson and Crowther12 The measure comprises seven non-modifiable ordinal value-based organisational components (Valuing Equality, Learning, Tailored to the Student, Co-production, Social Connectedness, Community Focus and Commitment to Recovery) and five categorical non-modifiable components (Available to All, Location, Distinctiveness of Course Content, Strengths-Based and Progressive). English Recovery Colleges have generally a high fidelity, with a median score of 11 out of 14 for non-modifiable components. Reference Hayes, Camacho, Ronaldson, Stepanian, McPhilbin and Elliott6 Finally, organisational variation in Recovery Colleges in England was previously categorised using cluster analysis which identified three distinct groupings: Strengths-oriented (affiliated with the National Health Service (NHS) and has a strong focus on amplifying the strengths of students); Community-oriented (not NHS Trust-affiliated and focused on social connectedness); and Forensic (NHS Trust-affiliated, with majority male student populations). Reference Hayes, Camacho, Ronaldson, Stepanian, McPhilbin and Elliott6 While Imroc principles and components of the Fidelity Measure are widely propagated and understood among proponents of Recovery Colleges, research has not sought to examine, in depth, the variations in practice and operation within Recovery Colleges and how these develop. Existing studies describing specific operating practices and organisational variation within the colleges tend to be single-site case studies, for example in England, Reference Ali, Benkwitz and McDonald13 Italy Reference Lucchi, Chiaf, Placentino and Scarsato14 and Canada. Reference Martin, Stevens and Arbour15 Furthermore, while Recovery Colleges must adhere to the core principles of recovery, research has not investigated how organisational factors can pose challenges to staff’s ability to adhere to ideals such as being accessible to all. By understanding how Recovery Colleges operate in relation to factors such as their relationship with funders, access to facilities and staffing profiles, this paper contributes to informing good practice guidelines for setting up and sustaining Recovery Colleges.

Aims

The aims of this study were to ascertain how organisational factors facilitate or hinder the set-up and sustainable running of Recovery Colleges, and to identify how colleges vary in their operation.

Method

Study design

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were analysed to investigate the organisational factors contributing towards the set-up, development and sustainability of Recovery Colleges. The RECOLLECT 2 Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP) comprised individuals based in England with lived experience of working at Recovery Colleges, attending Recovery Colleges as students and using and/or caring for those who use mental health services. LEAP members co-created the topic guide and co-facilitated the interviews.

Participants

Our previous national survey Reference Hayes, Camacho, Ronaldson, Stepanian, McPhilbin and Elliott6 aimed to identify all Recovery Colleges in England via web searches, consultation with Recovery College experts, snowball sampling and contacting organisations affiliated with a Recovery College (host organisations). Recovery Colleges included in the national survey were those that focused on supporting personal recovery and aspired to use co-production and adult learning approaches. A total of 88 Recovery Colleges were identified, from which 63 Recovery College managers completed the national survey, providing an indication of the organisational characteristics of the colleges. All 63 managers were invited to participate, of whom 31 managers provided informed consent in written or electronic form.

Materials and procedures

The topic guide for the interviews (shown in Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10955) was co-produced with the college managers attending an Imroc Recovery College Learning Set (meetings where Recovery College stakeholders discuss any aspect relating to the colleges) and LEAP members. The topic guide aimed to explore (a) how the COVID-19 pandemic had an impact on college operations (reported elsewhere) Reference McPhilbin, Stepanian, Yeo, Elton, Dunnett and Jennings16 (b) the history and organisational context of the Recovery College including when, why and how it was set up, goals when established, notable changes since set-up, and plans for further development (reported here).

Manager interviews were conducted online using Microsoft Teams (version 1.4.00.20211 for Windows) between October 2021 and April 2022. Interviewers were researchers (n = 6) or LEAP members. A total of 31 interviews were conducted, comprising 18 conducted by researchers alone, 10 conducted by researchers who were shadowed by LEAP members and three conducted by LEAP members alone. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, pseudonymised and analysed with NVivo 14 (version 1.6.1 for Windows; Lumivero, Denver, Colorado, USA; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/).

Analysis

Collaborative Framework Analysis was used to analyse the transcripts, an iterative process involving stages of data management, data summary and display and interpretation. Reference Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid and Redwood17 Grounded in interpretivism, Reference Bryman18 we adopted an inductive approach that sought to understand participant’s perspectives and experiences from their point of view while grounding our own interpretations in the data.

Stage 1 involved the creation of clear interview transcripts and Stage 2 consisted of familiarisation with these transcripts. The lead researcher (S.K.T.) read each transcript, checked for accuracy and noted themes of interest. Four academic researchers (S.K.T., T.J., V.L. and S.B.) with expertise in qualitative methodology and organisational behaviour, familiarised themselves with two interview transcripts.

Stage 3 involved open coding – a process where data deemed particularly relevant to the research question were assigned a code to summarise portions of the transcripts. The four researchers independently coded the same two interview transcripts using Microsoft Word.

In Stage 4, all four researchers met to compare the codes and agree upon a preliminary thematic framework (shown in Supplementary Appendix 2) that was used to sort the data into key topics of enquiry relating to the organisational variation and context of the colleges. This framework was then applied to a third transcript to assess how well it captured important information. In Stage 5, the refined thematic framework (shown in Supplementary Appendix 3) was deductively applied to all 31 transcripts using NVivo 14 software.

In Stage 6, the data were charted into a matrix table by summarising codes within each subtheme and including relevant quotes. A condensed version of the matrix is presented in Supplementary Appendix 4. In Stage 7, codes in the matrix were examined to identify interpretive themes across interviews, moving from surface features of the data to more analytical properties. Academic researchers discussed the matrix to refine and combine more descriptive themes into more abstract groupings, each drawing on impressions and ideas that they had recorded in note form in earlier stages of the analysis. A further meeting with co-authors, J.G.-R. – the CEO of Imroc and G.W., an academic within a School of Education, facilitated the interpretation of themes.

Ethics statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, as well as with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, revised in 2013. This study was conducted as part of the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) programme grant Recovery Colleges Characterisation and Testing 2 (RECOLLECT 2) (NIHR200605), a 5-year research programme exploring the effectiveness of Recovery Colleges in England. Reference Hayes, Henderson, Bakolis, Lawrence, Elliott and Ronaldson19 Ethics committee approval for the RECOLLECT 2 programme was obtained (MRA-21/22-26274 29.9.21 and 22/NW/0091).

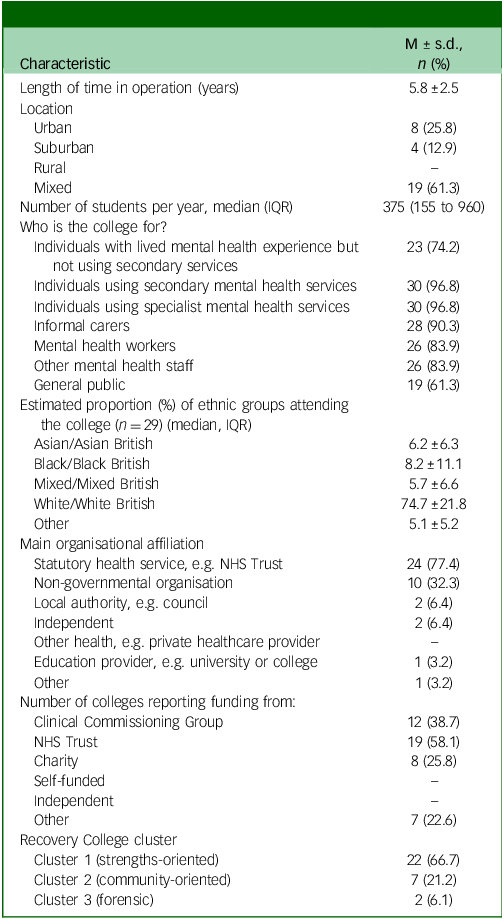

Of the 63 Recovery College managers who were approached, 31 (49%) participated in the interviews, comprising 35% of the 88 identified colleges in England. The organisational and student characteristics of the managers’ Recovery Colleges (taken from Reference Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid and Redwood17 ) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Organisational and student characteristics (n = 31)

IQR, interquartile range; NHS, National Health Service.

Compared with the national survey sample, while rural and private sector Recovery Colleges were under-represented, the distribution of Recovery College characteristics (e.g. location, main organisational affiliation and cluster) were broadly similar.

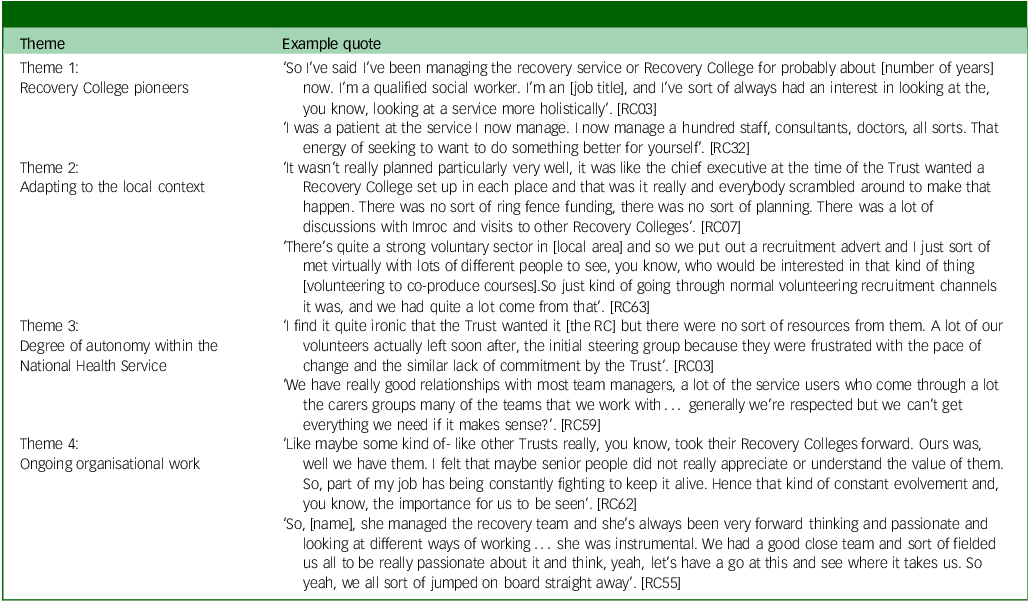

Five themes were identified. Corresponding quotes for each theme are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Subordinate themes and corresponding quotes

Results

Theme 1: Recovery College pioneers

Running a Recovery College was commonly described as a collaborative endeavour, yet managers often highlighted the importance of one person or a small group of actors who were instrumental in setting up the college. These were individuals who identified strongly with the values of the Recovery College, championed its establishment and were passionate about the college movement. This enthusiasm was often linked back to visiting an existing Recovery College, attending recovery conferences and/or reading peer-reviewed articles on these colleges:

‘We started to hear about recovery education. We decided to visit Recovery Colleges in Nottingham. We were introduced by the staff there and saw how this new model was working for them and the impact on people’s recovery and agreed we’re going to do it’. [RC15]

‘Noticing the research that was coming out on Recovery Colleges, we thought, this is great. We took it to some senior managers and they were really interested so, a little task group formed to bring them into our Trust’. [RC63]

Enthusiasm for Recovery Colleges often coexisted with lived and/or professional experience of the pitfalls of mainstream mental health services. Many managers had backgrounds working within mental health and the voluntary sector and identified specific limitations in their local service offerings:

‘If you wanted something as simple as dealing with anxiety, where would you find that? There’s just nowhere that you would find something like that unless you were able to pay for a session yourself’. [RC003]

The background of key instigators varied greatly across Recovery Colleges, including professional membership, current work role and whether they had lived experience of recovery. Their organisational position influenced the trajectory of their college’s development. In some instances, it was senior managers from within the NHS Trust that spearheaded support for the colleges. In these cases, they were able to mobilise existing Trust resources, for example staffing, IT systems and facilities. Front-line NHS staff also pioneered the creation of Recovery Colleges; here, they endeavoured to garner support for the colleges from senior managers whose organisational position greatly facilitated the development of the Recovery Colleges.

In other circumstances, it was members of third-sector organisations who sought to move towards the Recovery College approach. This required them to piece together resources and facilities from diverse sources. In one instance, it was a local group of ‘activist’ patients who acted as the key instigators:

‘We were so lucky because from day one we had a full sign up from the senior management and we were having conversations with various people about what this new model could bring to hospital’. [RC15]

‘Thing is to do with personalities and what people believe in and if you’re a chief executive and you believe in something, you’ve got the power to make a change. That particular chief exec had contact with Imroc. I think his leadership style was to create a vision’. [RC17]

The development of the Recovery College was seen to be linked to the characteristics of the instigators, including their professional and organisational background, their tenacity as well as their level of seniority.

Theme 2: Adapting to the local context

A second important source of variation was how the Recovery College model was translated to the local context. This required detailed consideration of how the principles and values of recovery could work in relation to the local needs, while working with existing organisational structures, resources, staffing, facilities and processes. It also involved considering broader aspects of the local and regional environment, including geography and patient demographics, existing health and care services, gaps in provision and the potential to use existing resources and/or link with partner organisations:

‘We worked initially very closely with the community mental health team. We wouldn’t have the same eligibility criteria but it was a great place to start gathering ideas because they knew the local population in some way and we could see what gaps we could potentially help to fill’. [RC63]

‘I read about Recovery Colleges and thought we need to formalise this so along with the board of experts by experience, we designed basic outline for what our college would look like. I called together all the partner agencies and got everybody to write me a list of what resources they had and what they could provide’. [RC16]

In this way, Recovery Colleges commonly built upon elements existing within the local context, using existing templates rather than being implemented from scratch. Alongside this ad hoc contingent development, participants reported that instigators also reflected on the alignment of the emerging college to recovery principles. Imroc was referenced by multiple managers as providing support in this context, for example providing general guidance on the values and practices of Recovery Colleges:

‘The Recovery College model really seemed to suit what we were doing. There are 22 other service charities that do employment support, so we thought we didn’t need to be the 23rd, we could lend our strengths to the psycho-ed courses’. [RC19]

Establishing the Recovery Colleges involved iteratively negotiating how to fit the model to the local context, while also reviewing the development of the college in relation to the guiding principles provided by Imroc.

Theme 3: Degree of autonomy within the NHS

A third source of Recovery College variation stems from the extent to which strengths-oriented colleges (funded by the NHS) were integrated or comparatively independent from the funding NHS Trust. Integration with the NHS Trust created two main benefits for the colleges. First, a wide pool of qualified health professionals (such as psychologists) to co-produce and co-facilitate courses, thus increasing staff capacity to co-produce health-related workshops and courses:

‘If you are separate to the NHS, you don’t have those professionals by experience… If we’re developing a course around eating disorders, I can pick the phone up and speak to three consultants and 10 nurses and say, “let’s sit around a table and look at this and make sure it’s safe and effective”’. [RC23]

The second benefit of Recovery Colleges being integrated with an NHS Trust is the increased visibility of the colleges among secondary care users of the service and therefore the promotion of Recovery Colleges as a recovery-oriented intervention available alongside mainstream mental health treatment. This was evidenced in cases where the NHS Trust drew upon the college resource to support people in transitioning back into the community:

‘We have got a community forensic team. We are working with them on developing a pathway, narrowing down to what it is exactly that they would like to do after discharge. The Recovery College is always keen to employ new peer tutors and involving service users and family members in service development and improvement’. [RC15]

While integration with the NHS facilitated provision of resources and raised the visibility of the colleges, several managers explained a feeling of competing against the NHS Trust for resources. This, in turn, led to staff feeling that they needed to continually justify their existence against mainstream mental health services:

‘It was a bit of a sort of a begging game. “Please can you offer this?” “On top of this, could you co-produce?”’. [RC15]

‘I would love to be able to convince the Trust to let the Recovery College have its own space’. [RC62]

The perceived lack of support from the funding NHS Trust was associated with the prioritisation of clinical services which, in turn, created funding challenges for the Recovery Colleges:

‘We get left out of a few things … because we’re not clinical, we aren’t a priority, it’s difficult to get the funding. Funding has to be a priority for clinical services’. [RC59]

‘We were promised some money for the Recovery College but it got taken away because it was put against paid peer support workers. They were very much seen by the Trust as something very separate’. [RC62]

Managers also articulated challenges related to NHS bureaucracy as some procedures were perceived as tedious and time-consuming which, in turn, contributed to a sense of lacking autonomy within the Recovery College. One manager of a college funded by multiple charities, reported being less burdened by rules and paperwork, stating that third-sector partners helped to mitigate the impacts of bureaucracy:

‘There’s quite a lot of governance around how they do the mindfulness, you need to have certain levels of experience to teach people mindfulness’. [RC54]

‘In the NHS … we have to write the business case and get around 40 to 50% of what you’ve asked, this is why partnerships are so important to us’. [RC23]

While collaborative relationships with an NHS Trust felt integral for Recovery Colleges, providing resources such as patient referrals, professional staff and avenues for promotion, this sometimes came at the cost of the college staff feeling constrained. Recovery College managers spoke about the importance of charity and third-sector partnerships in bypassing some of the difficulties seen within the NHS.

Theme 4: Ongoing organisational work

The fourth source of variation was the ongoing organisational work undertaken by Recovery College leaders alongside staff, students and supporters to keep the college operating in changing circumstances. As a relatively novel service, there were often few existing templates for action. This meant that maintaining the Recovery College involved numerous ongoing decisions around each aspect of the organisation, including the focus of classes and courses, forms of delivery, locations of activities, appropriate forms of user engagement and co-production and referral and eligibility criteria:

‘We initially only opened up registrations for clients of the community mental health team … a decision made by the head of mental health in terms of kind of risk management. After more conversations with our steering group, we opened up to all adults in the area, so that was a big milestone and something that we were really keen to push for’. [RC63]

Managers identified numerous challenges and events that shaped decisions on how to take the Recovery College forward while seeking to align this with their vision for recovery. This included internal factors such as difficulty in collaboration with the host Trust, bureaucracy, lack of funding and resistance to the recovery approach by mainstream mental health services. This also included external factors, such as changing public policy and commissioning arrangements as well as numerous changes within partner organisations:

‘We’ve just had a horrible budgetary kerfuffle, we lost the funding for my (senior manager) role and all our admin. The only funding we still had was for our casual peers and our service manager’. [RC50]

Recovery College staff and members worked in creative and entrepreneurial ways to continue the colleges within tight constraints. This included action to understand changing circumstances, maintain networks of support, adapt processes and communicate the successes of the colleges. In many respects, it was the combination of the constraints faced by Recovery Colleges combined with the enthusiasm and passion of staff that shaped the emerging colleges:

‘The Trust wanted the RC but there were no resources from them. The building was still local authority building so in my mind we’ve worked very much to an asset-based approach and a partnership approach model because that was going to get us off the ground’. [RC07]

The description of this manager as adopting an asset-based approach and partnership model was illustrative of the way in which Recovery College managers looked for opportunities and were willing to work around organisational gaps and a lack of resources. Adaptation existed alongside reflection on the way the college upheld the principles of recovery. Overall, the interview respondents conveyed the need for resilience and fortitude among those involved in the Recovery College to keep it going, which, in turn, was underpinned by the belief and investment in the recovery approach.

Discussion

Our aim was to identify barriers and facilitators to the set-up, running and sustainability across 31 English Recovery Colleges, as well as ascertaining how the colleges operate differently from each other. In relation to the set-up of the colleges, initial development was typically led by one person or a small group, who had a combination of passion for recovery, mental health lived experience and/or dissatisfaction with current provision. Development involved navigating diverse aspects of the local and regional context, including existing services and workforce opportunities, with momentum often provided by Imroc guidance. The level of autonomy versus integration with the existing statutory service provided by the NHS, created both opportunities and costs. Finally, no single route to sustainability was identified, indicating the need for agility and the benefits of an asset-based partnership model.

Set-up approaches are based on local resources. While Imroc was instrumental in supporting the set-up and development of the Recovery Colleges by offering frameworks, consultancy and practical tools to help embed recovery-oriented practices within mental health services, due to the diversity of existing resources, an initial resource scan of local opportunities and networks is needed to establish Recovery Colleges. Reference Claisse, Durrant, Branley-Bell, Sillence, Glascott and Cameron20 Collaborating with existing services, particularly those which had an orientation towards personal rather than clinical recovery, led to establishing a wider ‘task force’ to develop aspects of the colleges.

Sustainability involves agility. Recovery Colleges are guided by shared principles operationalised by Imroc and the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure, but they must remain responsive to local needs, resources, gaps in service provision and pressures from the funder, rather than adopting a uniform blueprint. This localised evolution supports the view that fidelity to recovery values must be balanced with practical responsiveness. For example, the goal of the colleges being accessible to those who do not use mental health services is challenging where their funding is sourced via secondary mental health services, since their performance indicators may place pressure on the colleges to restrict attendance to people using the services. Reference Perkins, Meddings, Williams and Repper2 Recovery College implementation is highly contingent on individual leadership, organisational alignment and contextual factors. Supportive infrastructure – such as flexible funding mechanisms, Imroc guidance and knowledge-sharing networks, enable Recovery Colleges to evolve in contextually appropriate ways while maintaining fidelity to recovery principles.

The relationship between a college and its funding host led to advantages and disadvantages. The integration of a Recovery College with its funding NHS Trust (e.g. by the college being a part of a person’s discharge plan) has been linked to heightened visibility, both in terms of increasing staff awareness of the Recovery Colleges, and promoting the college as a recovery-oriented intervention available alongside mainstream mental health treatment. Reference Crowther, Taylor, Toney, Meddings, Whale and Jennings3 Less collaborative relationships between the funder and Recovery College saw a direct impact on funding. Funding has been shown to reflect the value placed on staff, with research illustrating peer support workers feeling that the lack of investment in long-term positions and training indicates lower value. Reference Foye, Lyons, Shah, Mitchell, Machin and Chipp21 Relationships between the funder and college need to be collaborative in a way that ensures that a recovery-oriented approach is systemically and sustainably embedded within both organisational cultures. Reference Slade, Amering, Farkas, Hamilton, O’Hagan and Panther22

Despite Recovery Colleges being funded by an NHS Trust, managers described difficulty in securing resources, attributing this to the prioritisation of clinical services and thus contributing to a culture of the college staff feeling sidelined within the NHS. This sense that recovery is at odds with the way the NHS is run mirrors research indicating that where clinical systems dominate, favouring medicalised, risk-averse and outcome-focused models, Reference Le Boutillier, Slade, Lawrence, Bird, Chandler and Farkas23 this acts as a barrier to recovery-oriented care. The prioritisation of measurable clinical targets such as treatment compliance, highlights a need for recovery-driven values, organisational policies and training being embedded within a whole-systems approach.

Contrary to research highlighting Recovery Colleges as autonomous institutions despite being embedded in statutory infrastructures, Reference Woolsey and Mulvale24 managers within NHS-located colleges also reported a lack of autonomy due to bureaucracy. Documentation-heavy procedures and the overhead of adhering to NHS-specific governance in relation to delivery of some courses, were deemed excessive, contributing to the Recovery College workforce feeling burdened. For the colleges to flourish within and alongside traditional mental health systems, funding models which enable a degree of separation between the Recovery Colleges is a way forward, allowing the colleges to be adequately resourced while having the autonomy to cultivate the colleges as a distinct, recovery and educational-oriented environment. Reference Crowther, Taylor, Toney, Meddings, Whale and Jennings3

A passionate workforce is central to the high degree of organisational resilience shown within Recovery Colleges. Organisational resilience has been defined as the way in which organisations achieve desirable outcomes amid adversity and barriers to adaptation and development. Reference Georgescu, Bocean, Vărzaru, Rotea, Mangra and Mangra25 Passion and staff fortitude were particularly visible in cases where the organisational context was perceived to be clashing with the values of the college staff, e.g. enrolment being limited to existing mental health patients. Recovery Colleges are required to navigate a number of competing pressures in order to enact recovery principles in practice. Entrepreneurial strategies such as partnership-building, asset-based approaches and ongoing advocacy, highlight the significant emotional and strategic labour required to sustain the colleges. While it is integral to invest in senior leaders and staff who invest in recovery-oriented practice and are prepared to respond to resistance and challenges, emotional and practical support must be provided to prevent burnout and reduce the burden associated with emotional labour. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Recovery College staff were shown to be agile and innovative when responding to pandemic-related challenges. Reference McPhilbin, Stepanian, Yeo, Elton, Dunnett and Jennings16 The ability to innovate allowed the colleges to develop an alternative culture to their host organisation. Within Recovery Colleges, organisational resilience requires not only a passionate, united college workforce but also a system which allows for flexibility to continuously innovate ways of working..

Strengths and limitations

This is the first multi-site study exploring the factors contributing to the success of Recovery Colleges, and the organisational challenges faced by college staff. It demonstrates how organisational aspects influence college operations and fidelity, for example, the previously mentioned reduction in the peer support workforce (implemented by an NHS Trust), had an impact on the associated Recovery College’s co-production capacity. The interviews were co-developed and co-facilitated by the LEAP, enhancing the trustworthiness of the data. A limitation is that demographic data were not collected from managers, meaning that relationships between certain characteristics of the participants (such as the length of time working as a manager and seniority level of their management position) and themes in the data, cannot be investigated. Similarly, the anonymising process of transcripts inadvertently deleted the Recovery College cluster information, so between-cluster differences cannot be investigated. However, the large sample size and involvement of an expert in organisational behaviour (S.B.) in creating the thematic framework, enabled organisational context to be a strong focus.

Future directions for research

This study demonstrates the usefulness of using a theory-informed approach to the evaluation of Recovery Colleges as a complex intervention. Reference Hayes, Henderson, Bakolis, Lawrence, Elliott and Ronaldson19 As context is integral to the way in which the colleges operate, future work on the colleges could increasingly include consideration of how contextual factors play into observed outcomes, for example, by using realist evaluation which has been applied to other recovery-related innovations. Reference Marshall, Barbrook, Collins, Foster, Glossop and Inkster26 A second future priority is the investigation of Recovery College set-up and sustainability influences beyond England. This will involve de-emphasising England-specific influences such as the relationship with the NHS and identifying new dimensions of heterogeneity for colleges operating in very different contexts. It will also involve consideration of cultural characteristics, which are known to influence Recovery College fidelity. Reference Kotera, Ronaldson, Hayes, Hunter-Brown, McPhilbin and Dunnett5 For example, one fidelity item – staff responding to students’ individual needs – implicitly relies on students being able to express those needs. This ability to express needs, which may be easier in more indulgent cultures such as England (where societies greatly value and encourage gratification of desires), compared with more restraint-oriented cultures (where value is placed on self-control, social norms and delayed gratification). Reference Hofstede27,Reference Kotera, Ronaldson, Takhi, Felix, Namasaba and Lawrence28 Moreover, students’ expectations of the colleges vary across cultures; Reference Kotera, Daryanani, Skipper, Simpson, Takhi and McPhilbin29 for instance, ‘self-management’ is valued by Recovery College students in England, while ‘learning together’ is prioritised by students in Japan. Reference Kotera, Miyamoto, Vilar-Lluch, Aizawa, Reilly and Miwa30 Attending to such cultural nuances will be essential in ensuring that Recovery Colleges remain responsive, effective and contextually relevant across diverse international settings.

This study lays the foundation for building a theory-informed, globally relevant understanding of Recovery Colleges as complex interventions. A balance needs to be achieved where the colleges are autonomous and culturally distinct interventions while, crucially, being adequately resourced. In the absence of any central policy guidance on resourcing or managing collaborative relationships between the funder and college, tensions and a sense of Recovery College staff ‘fighting to keep the Recovery College alive’ may continue.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10955

Data availability

Data are available from the UK Data Service https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-857525.

Acknowledgement

M.S. acknowledges the support of the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: M.S., C.H., S.K.T., S.B., V.L. and T.J. Data collection: M.M., K.S., D.D., S.B., Y.O. and J.G.-R. Data analysis: S.K.T., T.J., S.B. and V.L. Writing of manuscript: S.K.T. S.K.T., T.J., M.M., K.S., D.D., J.G.-R., Y.O., G.W., J.G.-R., A.R., M.N., Y.K., P.B., S.L., A.K., S.M., J.R., L.P., C.H., M.S., S.B. and V.L. contributed to critically revising the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Funding

This article is independent research funded by the NIHR (Programme Grants for Applied Research, Recovery Colleges Characterisation and Testing (RECOLLECT) 2, NIHR200605). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declaration of interest

None.

Transparency declaration

The lead authors affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the reported study; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.