1. Introduction

Providing a semantic theory for gender terms that is inclusive of trans identities has posed a challenge in recent philosophy of language. In an influential paper, Jennifer Saul (Reference Saul, Crasnow and Superson2012) suggested (without herself endorsing) a strategy of viewing gender terms as context sensitive. Several writers have taken up the suggestion, exploring a range of semantic theories for context-sensitive expressions to test whether they may be applicable to the case of gender terms. These accounts tend to be motivated by the intuition that many gender ascriptions vary in truth value depending on the context in which they are used or assessed. However, the motivation for the intuition is questionable. For example, a commonly cited candidate sentence is WOMAN:

WOMAN: X is a woman.

Consider the case where X is a trans woman. Following Saul’s original discussion, this example is presented as intuitively true when uttered in a context where the issue under discussion is whether X should be entitled to use the women’s bathroom. But, so the argument goes, it will not be intuitively true when the issue under discussion is whether X should be invited for a medical procedure for those with female reproductive organs such as a cervical screening test. While many share the intuition that WOMAN changes truth value across such contexts, there are good grounds for resisting that conclusion. In particular, as noted by many (e.g., Bettcher Reference Bettcher, Soble, Power and Halwani2013, 240; Kapusta Reference Kapusta2016; Zeman Reference Zeman2020, 771–72) we may well want to insist that, regardless of the intuitions arising in such cases, the extension of the term woman tracks gender, not sex, and hence the sentence remains true in both contexts.

This motivation for resisting the intuitive pull of context sensitivity that these examples tend to trigger is attractive in light of the distinction between ameliorative and descriptive projects. This influential distinction was first introduced by Haslanger (Reference Haslanger2000). A descriptive definition of a term identifies a meaning which explains the usage of that term by ordinary speakers. In many cases, a descriptive definition is the uncontroversial goal of an attempt to identify the meaning of a term. An empirically adequate semantic theory for English indexicals, for example, should make the right predictions about how ordinary speakers of the language use these words. But there are some expressions, particularly those with contested definitions within social, political, and philosophical theorizing, where Haslanger argues that an alternative approach is available and, indeed, preferable. The term woman is just such an expression. As philosophers, our interest in the definition of this term is a theoretically sophisticated one that is rarely reflected in the ordinary usage of the word. Most notably, philosophers tend to ask the question against the background of a rich theoretical framework incorporating the sex/gender distinction.Footnote 1 But this distinction is rarely respected in ordinary language. Insofar as the descriptive analysis tracks ordinary language, it will be unhelpful in defining the term in a way that makes it suitable for discussions presupposing the sex/gender distinction. In response, Haslanger holds that we are entitled to adopt a self-consciously normative strategy in defining the term. Rather than asking “how do ordinary speakers use the word woman?” we should ask “how should ordinary speakers use the word woman?” The answer will be an ameliorative definition of the term.

An ameliorative approach, we think, should inspire us to reject the intuitions that push us towards thinking WOMAN is false in the medical context. While it may be true that ordinary speakers tend to use the word woman in a way that is ambiguous between a word denoting gender and a word denoting biological sex, they should not do so. Rather they should reserve the term woman for denoting gender. Accordingly, WOMAN is just as true in the medical context as it is in the bathroom context. What is false is the assumption that all women have cervices, and an ameliorative definition of woman should deliver the normative directive to medical professionals that they modify their use of the term to ensure it is a gender term, not a sex term.

Whilst we reject the claim that WOMAN varies in truth value between the medical and bathroom scenarios, we do not reject the claim that gender terms are context sensitive. We aim to show in this paper that reflection on issues surrounding transgender identities and experiences provides independent grounds for endorsing the view that attributions of gender are subject to possible truth-value variation across contexts. The reason is the need to accommodate the possibility of retraction, i.e., the ability to take back a previously true utterance. Some (but not all) trans individuals retract past gender self-identifications despite the fact that they were sincere in their context of use. Our motivation for retraction comes from trans testimony and especially from, as we call it, Later in life narratives. These narratives and the ability to retract, we will argue, show that sentences like WOMAN can change truth value after all. Furthermore, the kind of truth-value variation at play here places constraints on the kind of semantic theory that can accommodate it which were not raised by the existing examples of alleged truth-value variation. In short, we offer a novel argument for the context sensitivity of gender terms that is wholly independent of the existing arguments. We will argue that a relativist semantic theory for gender terms best accounts for the phenomenon we identify and will describe the sort of relativist theory that we think is best equipped for the task.

2. Testimony

Before we delve into the matter of retraction, we want to spend some time presenting gender experiences that motivate this paper. In the following, we present two types of narratives that we draw from existing interviews with trans individuals. Our aim here is simple: to highlight that there is no one universal trans experience. This will help us to establish the types of cases we consider when we think of retraction as well as give a clear indication of what types of experiences a semantic account ought to cover.

2.1 “I always knew” narrative

The most familiar trans experience is one in which the individual has always known or known from a very young age that they were of a different gender than the one assigned to them at birth. This is summarised succinctly by Catherine’s and Taylor’s experiences:

2.2 Later in life narrative

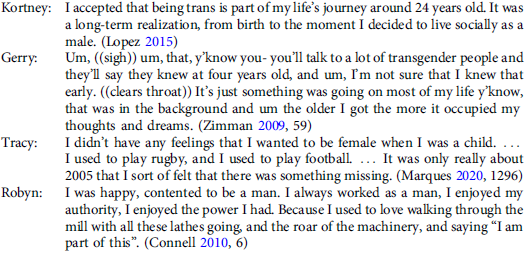

Although the “I always knew” narrative is common, it is not the universal gender experience. One alternative is the Later in life narrative where the realization of one’s true gender identity occurs when one is a teenager or older. In such cases it is likely that at t1 an individual can truthfully utter “I am a man” and the proposition be true, whilst at t2 the same proposition is false. Here an individual is likely to take back their previously true utterance. Later in life narratives are supported by extracts from the following interviews:

Whilst we think that most semantic accounts have focused on the “I always knew” narrative in their motivations and considerations, we want to illuminate the Later in life narrative. As we show below, we take these types of narratives to be suitable for cases of retraction.

2.3 Retraction

To clarify what retraction is we begin with MacFarlane’s (Reference MacFarlane2014) retraction rule. In doing so we utilize examples from the literature on the semantics of predicates of personal taste (e.g., fun and tasty) and epistemic modals (e.g., must and might) before moving on to retraction and gender terms.Footnote 2 MacFarlane takes the following rule to be a norm for retraction:

Retraction Rule. An agent in context c2 is required to retract an (unretracted) assertion of p made at c1 if p is not true as used at c1 and assessed from c2. (MacFarlane Reference MacFarlane2014, 108)

Consider two contexts: in context c1 X is a small child and does not find olives tasty hence she utters (1); in context c2 X has grown up and now find olives tasty hence she would not utter (1).

-

(1) Olives are not tasty.

Since X’s tastes have changed at c2, (1) is no longer true. Thus, according to the retraction rule, X must take back her utterance of (1) as it is not true as used at c1 and assessed from c2. X should utter I take that back; what I said was false, olives are tasty or I retract that; olives are tasty. Importantly, X’s utterance at c1 was sincere: X, at the time of c1, did not find olives tasty. By retracting her assertion X is not claiming that she’s blameworthy for her earlier assertion (e.g., that she was lying at c1). As MacFarlane writes: “Retraction is not admitting fault” (Reference MacFarlane2014, 110).

Before we move on to discuss how this applies to gender, a word of caution is needed. We, like many others, do not find the claim that one is required or obligated to retract an utterance that is no longer true very convincing. This seems to ask too much of an individual. If we were to demand X take back her earlier assertion of (1) there is no reason why she cannot protest and say I’m not taking it back, when I said it it was true. Doubts regarding obligatory retraction have been raised by von Fintel and Gilles (Reference von Fintel and Gilles2008). They focus on epistemic modals (in this case might) as illustrated below:

-

(2)

-

a. Alex: The keys might be in the drawer.

-

b. Billy: (Looks in the drawer, agitated.) They’re not. Why did you say that?

-

c. Alex: Look, I didn’t say they were in the drawer. I said they might be there—and they might have been. Sheesh. (von Fintel and Gilles Reference von Fintel and Gilles2008, 81)

-

Were we to follow MacFarlane we would have to insist that Alex should retract her earlier claim once she finds out that the keys are not in the drawer. As such, (2c) should read as infelicitous at worst and unreasonable at best. It does not. Of course, more can be said about these examples and the nature of retraction itself. But, given that we are seeking a retraction rule that fits with the range of data spanning both the “I always knew” and the Later in life narratives, we clearly need a weakened rule compared to MacFarlane’s. One can retract an utterance that is no longer true (but it is not the case that one must retract).Footnote 3 Consequently, we amend the retraction rule:

Amended Retraction Rule. An agent in context c2 can retract an (unretracted) assertion of p made at c1 if p is not true as used at c1 and assessed from c2.

It should be noted at the outset that this modification of the rule will require some moves to be made within the details of the semantic theory we endorse. MacFarlane’s retraction rule is a direct consequence of MacFarlane’s semantic theory, and our preferred semantic theory will have to be constructed so as to support our rule instead. We will return to this point when introducing relativist semantics in section 5. We take the possibility of retraction to be essential to a theory of gender terms since we want an account to allow for a wide range of gender experiences. Retraction provides the option to retract one’s earlier gender claim if one wishes. Perhaps after her transition, X might want to reassess her whole life and be able to take back her previous utterances. This sentiment is reflected by Bettcher who, in considering a self-identificatory account, writes:Footnote 4

Admittedly, this means trans women who don’t yet self-identify as women aren’t yet women (in this sense). That said, once she does self-identify as a woman, she may well re-assess her entire life by saying she’s always been a woman (something we should respect, too). (Bettcher Reference Bettcher, Garry, Khader and Stone2017, 396)

To clarify what retraction looks like with gender terms consider two contexts: in context c1 X is younger and identifies as a man; in c2 X is older and has come to realize that her true gender identity is that of a woman. In such a scenario there is no reason why X cannot retract assertions made at c1.

-

(3)

-

a. X at c1: I am a man.

-

b. X at c2: I take that back; what I said was false, I am not a man/I retract that; I am not a man.

-

To be clear the type of phenomenon we’re interested in is when one sincerely identifies as a different gender in an earlier context. Thus, cases described by the “I always knew” narrative seem less likely (although not impossible) to be of the kind to give rise to retraction. This is because if X has always known that she is a woman, then a plausible explanation of utterances of (3a) at an earlier context would be that those utterances were never true. Perhaps X felt pressured into uttering (3a) but she never really believed it.Footnote 5

The paradigm cases that we would consider of retraction would be those occurring in the Later in life narratives. If X only realizes later in life that she’s a woman (similar to Tracy or Robyn in the section above), it seems that her earlier utterances of (3a) would be sincere. She would have truthfully made those claims. Later in life however, realizing her true identity she is entitled to take back those earlier utterances (if she wishes to do so). If someone sincerely identifies as one gender at c1 yet identifies as a different gender at c2 we want to be able to account for the need to retract that statement without making the claim (as used and evaluated) at c1 false. What we want is a semantic theory that allows for (3a) to be true at c1 and (3b) to be true at c2. Since retraction is not connected with being at fault, endorsing retraction will respect this intuition. Again, it’s worth reiterating that one need not retract. Retraction will be the main challenge we present against other theories as well as motivation for our account.

3. Semantics

To assess the strengths of a particular theory and specifically its ability to deal with retraction, we must first present a semantic framework. Keeping formalism to a minimum, we start with a general picture stemming from Kaplan’s (Reference Kaplan, Almog, Perry and Wettstein1989) semantics for indexicals, i.e., expressions like I, here, now.

Kaplan takes indexicals to encode functions which map the context in which they are used to a content, with the content thus varying in accordance with changing contextual parameters. So, a context in which agent A is speaking is mapped to a different content by the function encoded by the word I, to that which a context in which agent B is speaking is mapped to. This function Kaplan calls the character of the indexical. Contexts are the sequences of parameters which are demanded as the inputs to the characters of the indexicals. Typical contextual parameters will include: the world parameter (cw); the time parameter (ct); the location parameter (cl); the agent (i.e., the speaker) parameter (ca). The context sensitivity of indexicals is therefore linguistically mandated in the sense that the contribution made by context is required as part of the linguistic meaning (character) of the expression. In addition to specifying this systematic role for context in determining the meanings of indexicals, Kaplan also allocated a somewhat different kind of (what we might also call) context sensitivity by taking propositions to have truth conditions which are temporally relative. The proposition Socrates is sitting can be true relative to some times, and false relative to others. This variation across times is not something which results from a character producing varying contents, rather we have perfectly complete contents that can vary in truth value over time.

To formalize this relativization of truth values to times, Kaplan takes propositions to be functions from world-time pairs to truth values. Inspired by Kaplan’s formalization, recent work in formal semantics has extended the model beyond relativization of truth values to worlds and times to generate versions of semantic relativism, by simply expanding the world-time pairs to sequences of greater adicity. So, for example, relativists about predicates of personal taste such as Lasersohn (Reference Lasersohn2017) and MacFarlane (Reference MacFarlane2014) recognize a judge or a standard of taste parameter as something that statements regarding matters of taste are true or false relative to. What emerges from this semantic framework is a two-fold way that context is semantically significant. On the one hand, a sentence may depend on context to express a content (as we see with indexicals), or it may have a different truth value depending on which sequence of parameters it is assessed relative to (as we see with relativism). So sentences are sensitive to the contexts they are used in, as well as the contexts they are assessed relative to. Let us say the first depends on a sensitivity to the context of use and the second is a sensitivity to the context of assessment. Footnote 6

Drawing on this framework, we focus on two proposals indexical contextualism and assessment-sensitive relativism. For the former the contents of expressions are sensitive to the context of use in the way we see for indexical expressions in Kaplan’s theory. Consequently, gender terms will change in content from context to context. For the latter, we recognize contexts of assessment in addition to contexts of use. As such, the contents of gender terms are stable from context to context, but the proposition will be evaluated relative to a context of assessment. Hence, the outcome of the evaluation may change across contexts of assessment. We begin by investigating indexical contextualism in more detail.

4. Indexical Contextualism

Indexical contextualism is the view that the contents of gender terms change across contexts of use and so woman has a non-constant character. Akin to the character of the indexical I. Notably, this view was suggested (but not endorsed) by Saul (Reference Saul, Crasnow and Superson2012) who proposes the following truth-conditions for utterances like WOMAN:

X is a woman is true in a context C iff X is human and relevantly similar (according to the standards at work in C) to most of those possessing all of the biological markers of female sex. (Saul Reference Saul, Crasnow and Superson2012, 201)

The key part here is the one in parentheses, “according to the standards at work in C.” If the standard changes, then the content of woman will change and in turn, the truth values of a proposition will also change. We can think of this proposal as introducing a standard parameter into the context of use (c s ), which will pick out the right standard for each context. Thus, in a context where c s picks out self-identification, we get the following explication of WOMAN:

-

(4) Uttered at cu1, where self-identification is under consideration:

X is a woman -in-a-woman-self-identifying-manner.

It is enough for X to self-identify as a woman to be “relevantly similar … to most of those possessing all of the biological markers of female sex” for the utterance to come out as true in cu1. Importantly, the standard can be set by anyone uttering WOMAN, this is where such contextualism falls short of a satisfactory theory. Saul herself notes that one of the main issues with the view is that it will allow transphobic utterances to come out as true (Reference Saul, Crasnow and Superson2012, 210). Take someone who believes that only biological markers (such as having XX chromosomes) make it true that one is a woman. For such a person, WOMAN would mean the following:

-

(5) Uttered at cu2, where biological markers are under consideration:

X is a woman -in-a-woman-XX-chromosome-manner.

For whoever applies the standard of biological markers as in (5), WOMAN would always come out as false. Thus whilst WOMAN will be true in those contexts where self-identification is the relevant standard (and so WOMAN’s negation will be false), there will still be contexts where WOMAN will come out as false as the speaker of those contexts will not take self-identification to be the relevant standard. Moreover, as has been pointed out by Saul herself, this view would trivialize the word woman, Saul writes:

[The flexibility of the word woman] would be deeply unsatisfying to the trans woman who wants to be recognized as a woman simply because she is a woman rather than because “woman” is such a flexible term. What the trans woman needs to do justice to her claim is surely not just the acknowledgement that her claim is true but also the acknowledgement that her opponent’s claim is false. And the contextualist view does not offer that. (Reference Saul, Crasnow and Superson2012, 210)

As a solution to the applicability of contextualism to gender terms, Díaz-León (Reference Díaz-León2016, Reference Díaz-León, Plou, Castro and Torices2022) proposes a modification of Saul’s contextualism by shifting the focus away from the speaker to the subject of the sentence. She calls Saul’s contextualist presentation attributor-contextualism (the standards are determined by the speaker) and her own species of contextualism subject-contextualism. Under Díaz-León’s account, the standard will be determined “by the best moral and political considerations involving the subject of the utterance” (Díaz-León Reference Díaz-León, Plou, Castro and Torices2022, 240). As such Díaz-León can explain why the standard applied in (4) is appropriate, whilst the one applied in (5) is not. In the case of (4), our best moral and political considerations are such that what is important is self-identification of the subject of the utterance. Since our best political and moral considerations are ones where gender is not decided by biological matters, we can explain why utterances like (5) are incorrect: the speaker applies an incorrect standard to the term woman. Importantly, subject contextualism does allow for truth-value variation. The character of the word woman is something along the lines of meets the standard determined by the political and moral reasons involving the subject of the context of use. The character will provide different content in different contexts (should the standard change). The change in the content of the word means there is no fixed meaning of the term woman.

4.1 Indexical contextualism and retraction

In this section, we demonstrate how indexical contextualism struggles to deal with retraction claims. We’re going to stay neutral over exactly which standard is applied as we’re neutral to which version of contextualism we’re talking about. Recall our amended retraction rule from section 2.3:

Amended Retraction Rule. An agent in context c2 can retract an (unretracted) assertion of p made at c1 if p is not true as used at c1 and assessed from c2.

Consider a context cu1 where X sincerely utters:

-

(6) X at cu1: I am a man.

-

a. X is a man-according-to-standard-of-cu1.

-

At cu2, X no longer sincerely identifies as a man, instead she sincerely identifies as a woman:

-

(7) X at cu2: I take that back; what I said was false, I am not a man.

-

a. X takes it back; what X said was false, X is a man-according-to-standard-of-cu2.

-

On the indexical contextualist’s framework, the proposition expressed by (6) is (6a). Thus (6a) will only be true if X meets the standard of cu1. The content of each utterance is anchored to the context (and standard of that context) in which it is uttered. Since the standard for man changes in cu2, man in (7) will mean something different from man in (6).

When X is retracting her earlier utterance, she is not actually retracting what she said, rather she’s saying that if we take the new standard into consideration, she no longer meets the standard of man. Thus, by uttering (7) X has not expressed that she’s not a man from the standard of cu1, she’s only expressed that she no longer meets that standard. In other words, X cannot say that what she said (at cu1) is false, for at cu1 (6a) will always be true as X did meet the standard of man at cu1. The only way she could utter I was wrong, I take (6) back is if at the time of the utterance the proposition was evaluated as false, i.e., the contextual standard was not met.Footnote 7 This is not the scenario that we’re considering. So, prima facie, indexical contextualism cannot deal with retraction claims.Footnote 8

As a reviewer for this journal notes, there are options available for the indexical contextualist when it comes to retraction. They suggest two. The first strategy would be to deny that when X says what I said in cu 1 is false X is referring to the proposition expressed in cu1, but rather X is saying that the proposition that sentence would express in the new context is now false. Another possibility would involve metalinguistic negotiation. Metalinguistic negotiation occurs when a speaker or multiple speakers negotiate what a particular term means or should mean in a context. Hence, when X utters what I said in cu 1 is false she is genuinely referring to the past proposition, but what she is metalinguistically implicating is that the use of man in that context should have been used to express a different proposition—one which would consider the standard of cu2 and hence that proposition would be false. In other words, the speaker is negotiating (with her past self) over the correct meaning of man. Regarding the first avenue, we recognize that this is a possibility but it is not a case of genuine retraction—the most one can say is that I am no longer a man, the previous standard no longer applies, the proposition expressed by that sentence would now be false, but all of this has to do with a current context and not the one in which the utterance was first made. One has not taken anything back. We’re also sceptical about appealing to metalinguistic negotiation. There are no speech markers to indicate that what the speaker is engaged in is metalinguistic negotiation. Unless the indexical contextualist is prepared to say that every instance of retraction involves metalinguistic negotiation (a claim for which an argument would need to be made), it’s more likely that retraction markers like I take that back directly target the previous speech act and they target it for truth and not the meaning of the word. This is not to say that metalinguistic negotiation never occurs. For example, matters would be different if X was askedwhat counts as a “man” in your country?Footnote 9 Here there is space for X to negotiate the meaning of “man,” perhaps even consider her own previous utterances. Again, this does not seem to be a case for retraction.

Of course, an indexical contextualist might find our replies unsatisfactory or they might simply want to explain away retraction.Footnote 10 This might be sufficient for some; however, we find the indexical contextualist’s inability to give a straightforward account of retraction motivation enough to look to alternative avenues.

5. Assessment-sensitive relativism

In this section, we consider assessment-sensitive relativism and show that, although the simple version outlined here has some shortcomings (similar to Saul’s contextualism), this view can account for retraction. In section 6, we will go on to amend assessment-sensitive relativism and show how, with our amendment, it avoids all the challenges we have raised against other views.

Whilst assessment-sensitive relativism (relativism for short) has not been endorsed by anyone regarding gender terms, it has been considered by Zeman (Reference Zeman2020, 761–65). More broadly, it has been applied to predicates of personal taste (fun, tasty), epistemic modals (might), future contingents (there will be a sea battle tomorrow).Footnote 11 To illustrate its function, observe X’s utterance with the predicate of personal taste fun:

-

(8) Climbing is fun.

According to a relativist, the character of the predicate fun is a constant function from context of use to content—the content of fun never changes. What does change is the parameter that (8) gets evaluated from. The relativist introduces a new parameter into their semantics—the judge parameter—and utilizes it in the context of assessment (caj). The judge is the relevant individual for the assessment of a proposition, the assessor (one assessing the proposition) and the judge (for whom the proposition is true or false) often coincide, but this need not be the case. Hence, the speaker of an utterance or one evaluating a proposition at a later time might not be the judge. Further, since judges’ tastes can change over time we need to evaluate (8) in relation to a judge-time pair. As such (8) will be true just in case climbing is fun according to the judge’s tastes at the relevant time of evaluation and false otherwise. Thus, if X finds climbing fun, then (8) is true from the context of assessment where X is the judge of the judge-time pair. Crucially, the same proposition can be assessed from multiple contexts of assessment. Take Y for example, who is scared of heights and does not find climbing fun. As evaluated from the context of assessment in which Y is the judge, (8) is false.

Applying assessment-sensitive relativism to gender terms we get the following picture. The meaning of the term woman is constant, it’s the same in any context. Evaluation of gender propositions will depend on some judge-time pair. Thus, when X evaluates WOMAN, the proposition will be evaluated as true for it is true at the time of the context of assessment where X is the judge since X judges herself to be a woman. It might be obvious that relativism falls short in a similar manner to attributor contextualism. Whilst Saul’s attributor contextualism made the meaning of the gender term woman too flexible, this species of relativism makes the truth conditions of WOMAN too flexible. Yet again we’re in an unwanted situation where a trans person’s gender avowal is at the risk of becoming trivial since there is no restriction on who can be the judge. Whilst X takes herself to be a woman in ca1 (and thus WOMAN is true at ca1), the same utterance can be evaluated by a transphobe (at ca2) rendering WOMAN false at the context of assessment in which the transphobe is the judge. Moreover, akin to attributor contextualism, there is no way for anyone to argue that the transphobe has spoken wrongly. After all, the proposition is false as evaluated from the context of assessment in which the transphobe is the judge.

5.1 Assessment-sensitive relativism and retraction

One often cited benefit of assessment-sensitive relativism over contextualism is its ability to account for retraction.Footnote 12 This is because one can assess a proposition uttered at cu1 as false from ca2, even though it would be true if assessed from the context in which it was uttered. For example, if X utters I am a man at cu1, then this proposition (namely that X is a man) will only receive a truth value when evaluated from a particular context of assessment and importantly this context of assessment need not coincide with the context of use. The problem with indexical contextualism is that the content of a proposition is anchored to a particular context of use. For an assessment-sensitive relativist, this issue is non-existent since the content of a gender term is stable across different contexts (i.e., man and woman have the same meaning in all contexts) and the truth values are sensitive only to contexts of assessment. As such one can easily take back an utterance from the current context of assessment, as that proposition can be judged as false at the judge-time pair of the context of assessment (at ca2) if the judge no longer deems it true, i.e. the judge has changed their mind. In section 6, we develop a version of assessment-sensitive relativism in such a way that restrictions on the relevant parameter are introduced. However, a word of caution about relativism and retraction regarding gender has been given by Zeman:

Relativism accounts for [retraction] cases because, when trans people assess their claims about their own gender made before transitioning, the count-as[/judge] parameter is that of C A and the C A they occupy now is different from the one occupied before transitioning. Of course, this is good news for relativism only insofar it is a robust phenomenon that trans people take themselves to have been previously wrong about their own gender after transitioning. Despite the existence of a common narrative that might support this idea (expressed, arguably, by statements like “I always knew I was a man,” “I knew that something was wrong about my gender” etc.), there surely are alternative narratives concerning transition. What is worse, if such alternative narratives support the idea that some trans people do not, in fact, take themselves to have been previously wrong about their own gender, this might become a problem for relativism instead of a point in its favor. More data on this, as well as extreme caution, is needed here. (Zeman Reference Zeman2020, 764, n. 28)

We take Zeman’s concern that retraction is not a universal experience of trans folk seriously and we would like to make two comments. First, as discussed in section 2, we recognize that there is no one universal experience of being trans, thus we wholeheartedly agree with Zeman’s observations.Footnote 13 Secondly, the existence of alternative narratives would only present a problem for relativism if we demanded retraction in every case. We considered why this is an unreasonable demand not just when considering gender terms, but any terms—hence the Amended Retraction Rule.

A concern one might have with our proposal is the ease with which we have substituted MacFarlane’s retraction rule with our amended rule. As an anonymous referee rightly pointed out to us, this is no minor modification to MacFarlane’s position as it follows from his semantic theory for predicates of personal taste that retraction is compulsory if the utterance is no longer true.Footnote 14 The reason why comes down to the choice of parameter that we relativize intuitively subjective judgements to. MacFarlane notes that the required truth-conditional clauses can be equipped to provide the coordinates required for assigning denotations to predicates of personal taste in at least two ways. One can posit a judge parameter, such that a taste expression like “fun” has a denotation, and “rollercoasters are fun” has a truth value, relative to a judge. Or one can simply posit a standard of taste that “fun” and the like are relativized to. His choice is to opt for the latter, precisely because he thinks that changes of taste over time by the judge would lead to cases where retraction of past assertions regarding taste would be unrequired even when one’s tastes had changed (Reference MacFarlane2014, 163–64). MacFarlane’s retraction rule has it that a sentence S uttered in c1 should be retracted at c2 just in case S (as used at c1) is false with respect to parameters relevant to c2. If S is false with respect to the standard of taste initialized in c2 then the speaker should retract their earlier utterance of S. From a semantic point of view, the question is simply whether S is true relative to c2. So, if the agent finds rollercoasters fun at c1, but has had a drastic change of heart at c2 (one year later, let’s say), the semantics predicts that the agent should say things like:

(R1) I was wrong about rollercoasters, they are not fun after all.

And not things like:

(R2) I wasn’t wrong/I spoke truly, rollercoasters were fun.

(where this is meant purely as an observation about a change in taste, not of any objective features of rollercoasters such as their design being less extravagant than a year ago). For others (MacFarlane cites Lasersohn Reference Lasersohn2005 and Stephenson Reference Stephenson2007), results are not the same. On Lasersohn’s approach, for example, the semantic theory does not contain a standard of taste coordinate, but a judge parameter. Judges can change their tastes over time and Lasersohn is accordingly less demanding than MacFarlane in his approach, allowing utterances like (R2) to be true. It is important to note that this gives the temporal parameter a different role in Lasersohn’s semantics to the role it has in MacFarlane’s because we can now have cases where two contexts of assessment ca1 and ca2 differ only with respect to the temporal element of a judge-time pair, yielding different judgments of taste. MacFarlane’s adoption of a standard of taste rather than a judge does not predict that in cases where the standard of taste remains constant, while the time parameter shifts, a difference in judgment regarding taste could occur.Footnote 15 Accordingly, we follow Lasersohn’s approach as a better model for our purposes and take gender identity statements to express propositions which are true or false relative to judge-time pairs, rather than standard of taste-time pairs.

Of course, if Lasersohn’s semantic theory predicted that retraction was forbidden (i.e., that the fact that rollercoasters used to be fun relative to the agent’s tastes at the time they asserted it blocked them from subsequently taking it back), this would be a disastrous result not least because it would mean that the theory would lose its power to accommodate various retraction data that are often taken to support relativism.Footnote 16 But this is not the case. As Lasersohn (Reference Lasersohn2017, 139–41) makes clear, what agents are faced with is a choice between which context of assessment to assess an earlier assertion from. Just as one can (and often should) assess a statement of taste from a different perspective to one’s own, so one can assess a statement of taste from a different time to the present. For example, when Amy (a vegan) asks George whether his beefburger is tasty, she is seeking assessment from George’s perspective, not her own. Just as such exocentric judgments are relevant in many uses of predicates of personal taste, so also can earlier times be relevant to assessments of taste, making true utterances of (R2) felicitous. By uttering (R2), one is “sticking to their guns” and refusing to retract a previously true utterance, since the non-retraction marker “I wasn’t wrong/I spoke truly,” makes it clear that the relevant time of the context of assessment is one where an earlier judge-time pair is under consideration. But, equally, one can adopt a perspective anchored to the current time, making retraction like in (R1) appropriate, i.e., it is the current judge-time pair that is relevant. Both contexts of assessment are available within the semantic theory, but it is a pragmatic matter as to what guides the selection (Lasersohn Reference Lasersohn2017, 139).

In terms of the retraction rule we have been working with, what this means is that the full statement of the rule can be expanded as follows:

Amended Retraction Rule (Expanded). An agent at context c2 can choose to retract an (unretracted) assertion of p made at an earlier context c1, if p is not true as used at c1 and assessed from c2; or an agent can choose not to retract that assertion of p by assessing p relative to c1.

In short, an agent can choose between assessment from the time of their current situation, or from their earlier perspective. The latter will yield cases where utterances like (R2) are perfectly felicitous and true.

The scope of this paper does not extend to an evaluation of the competing arguments for MacFarlane’s position compared to Lasersohn’s with respect to the semantics of predicates of personal taste, and their ensuing predictions regarding retraction.Footnote 17 But for our application of relativism to gender terms we will clearly be better off adopting Lasersohn’s approach. On this view, retraction of an earlier assertion of gender self-identity is permitted, but not obligatory.Footnote 18

6. Our proposal: gender relativism

Although so far this paper has been largely critical, we also want to highlight the insights that we’ve gained. Subject contextualism made a convincing case for the restriction of the judge/standard parameter to guarantee that transphobic utterances come out as false. The simple version of relativism we discussed above equipped us with a framework in which retraction is realized. In the following, we combine these two insights and present a view we call Gender Relativism.

On our proposal, the character of a gender term is a constant function from context to content, resulting in the fact that man and woman have a constant meaning.Footnote 19 In other words, the context of use does not affect the content of these terms. What does change is the truth value of an utterance containing a gender term. Similarly to assessment-sensitive relativism, we adopt a judge parameter in the context of assessment. Unlike assessment-sensitive relativism, we want to restrict who the judge can be based on who the subject is. Thus, the judge parameter (caj) will pick out whoever the gender term is predicated of, and it will be down to their self-identification whether that predication is true or false.Footnote 20 Let’s repeat our principal example:

WOMAN: X is a woman.

According to gender relativism, WOMAN is true at those contexts of assessment where X is the caj and X identifies as a woman at the time of the context of assessment; WOMAN is false at those contexts of assessment where X is the caj and does not identify as a woman at the time of the context of assessment. This gets the correct result in cases where a transphobe attempts to deny X’s gender identity. For example, if Y was to utter X is not a woman, the proposition would not be assessed from Y’s perspective since Y is not the subject of the sentence. In other words, even though Y is assessing the proposition, given our semantics, Y is not the judge of the context of assessment. Since the judge of Y’s context of assessment would select X and X identifies as a woman, Y’s utterance would come out as false. We would have a way to explain why the transphobe is wrong, as they have failed to recognize X’s gender identity.

Note that although our view shares some similarity with subject contextualism by putting restrictions on who can be the judge, our view places a narrower requirement on this restriction. For subject contextualism the standard is decided by our best political and moral considerations. Consequently, this means that in some cases subject self-identification is trumped by other considerations.Footnote 21 Our view goes a step further and claims that it’s the self-identification of the individual that is the only suitable restriction; self-identification wins over other considerations. This restriction and the relativist semantics we adopt are the key differences between our view and subject contextualism.

The above sketch explains how our semantic theory provides relativistic truth conditions for singular predications of gender terms. An utterance of WOMAN is true at a context of assessment ca1 just in case X self-identifies as a woman in ca1. This holds whoever assesses WOMAN, and for all values of X. So for example, if X is someone who expresses the proposition themselves by using the first person pronoun then her assessment of it will be true if and only if she self-identifies as a woman at the relevant context of assessment, and Y’s expression of the same proposition by use of X’s proper name, and subsequent assessment of it will also be true if and only if X (the judge of the proposition Y is assessing) self-identifies as a woman in that context of assessment. A compositional semantics also needs to accommodate the use of gender terms in non-singular cases, like “All women deserve to be treated with respect,” “Some women are mothers,” “No women applied for the job,” and so on. It would be unwieldy, to say the least, to take the propositions expressed by utterances of these sentences to require evaluation at a context of assessment which featured a judge parameter corresponding to each and every woman denoted by the quantifier phrases employed here. Thankfully, this challenge is not unique to our semantic theory, and we can find correlates that arise for other relativistic expressions. Consider, for example, “Girls just wanna have fun.” What truth conditions should the relativist about fun offer for this? One option, of course, might be to insist that it is true at a context of assessment ca1 if and only if all girls want to have fun relative to ca1j. But this seems contrary to the sentiment of Cindi Lauper’s anthemic refrain. Surely what she meant was that all women want to have fun, by their judgment of fun, not by the judgment of whoever happens to listen to the song.Footnote 22 This requires treatment along the following lines:

“Girls just wanna have fun” is true as used at cu1 and assessed at ca1 iff for all x such that x is a girl and x wants to have funby the judgement of x .Footnote 23

Applying gender relativism will simply extend the same approach to the gender term:

“Girls just wanna have fun” is true as used at cu1 and assessed at ca1 iff for all x such that x is a girlby the judgement of x and x wants to have funby the judgement of x .Footnote 24

As Lasersohn (Reference Lasersohn2008) explains in detail, these results can be delivered most naturally by understanding quantification in such perspectival cases to involve quantification directly over the parameters that relativistic expressions are indexed to. Without being drawn into unnecessary technical details of how this is achieved here, we will simply note that the above examples show that there is nothing unique to gender relativism that raises this issue. The issue obviously arises also for relativist analyses of predicates of personal taste, and the solution adopted for those will naturally extend to gender terms.Footnote 25

6.1 Gender relativism and retraction

To complete our proposal, we explicate how gender relativism deals with retraction cases. We begin by reminding the reader of the Later in life testimonial data from section 2 and then move on to explain how those experiences can be accounted for within our semantics.

What we want from a semantic theory for gender terms is to allow for the possibility that Kortney, Gerry, Tracy, or Robyn, in light of what they say here, might want to retract some earlier utterances regarding their gender identities at the times they are describing even if those utterances were true at the time of their use. For example, if Robyn had asserted “I am a man” during the time she is here recalling, she may choose to retract that claim now in light of her current gender identity. Following the amended (extended) retraction rule we can see that if any of the individuals who subscribe to the Later in life narrative want to retract a previous utterance they can. We represent such a situation with X as an example below:

-

(9)

a. X: I am a man (true as evaluated from ca1).

b. X: I take that back; what I said was false, I am not a man (true as evaluated from ca2)/I retract that; I am not a man (true as evaluated from ca2).

Under gender relativism, as we present here, we can do this quite easily. Propositions are not anchored to any context since the contents of gender terms are constant in each context of use. Consequently, one can evaluate utterance (9a) from a judge-time pair separate from context of use. Thus, since X is still the subject of the sentence from the new context of assessment (ca2), it is still her who has the ability to evaluate the proposition. Since she no longer identifies as a man, her utterance of (9a) is false as evaluated from the new context of assessment (ca2).

We can also see how non-retraction is possible. Consider someone asking if X was wrong to utter “I am a man”. On our view X can respond:

-

(10) X: I wasn’t wrong. At that time, I was happy and contented to be a man (true as evaluated from ca1).

Here X makes it clear that she is taking the time of her original utterance to be the relevant one for evaluation (as marked by the non-retraction marker “I wasn’t wrong”) and at that time X did identify as a man. This satisfies the second clause of the expanded retraction rule, i.e., “an agent can choose not to retract that assertion of p by assessing p relative to c1.” Hence, she can explicitly refuse to retract that earlier assertion.

This also provides an explanation for why Robyn could, from the present context of assessment in which she identities as a woman, truly utter the past tense sentence “I was a man.” Given the past tense of “was,” the relevant judge-time pair for the context of assessment is at the time where Robyn was a man. Hence as uttered today the proposition—Robyn was a man—will be evaluated relevant to an earlier time rendering it true.Footnote 26

We take the possibility of retraction to provide a new argument for the context sensitivity of gender terms which is wholly independent of existing arguments. Furthermore, we take retraction to be demanded by the testimony considered in this paper. Because of the ease with which relativism can account for retraction, we take relativism to be the most promising approach to the semantics of gender terms. When amended, as we have done here, gender relativism provides a semantic theory which best accommodates the full range of gender experiences. A crucial feature of gender relativism as we have developed it is the appeal to self-identification. We therefore now turn to a major criticism against self-identificatory views.

6.2 Absence of self-identification

Elizabeth Barnes (Reference Barnes2020, Reference Barnes2022) has presented a serious question for self-identificatory views of gender: what do we say about those individuals without the capacity for self-identification? Barnes argues that, although self-identificatory accounts provide a way to include all of the individuals who identify as their chosen gender, at the same time such accounts manage to exclude those individuals without a capacity for self-identification. Barnes notes that “denying womanhood to cognitively disabled women seems like a gross injustice, especially given that cognitively disabled women are particularly vulnerable to gendered abuse” (Barnes Reference Barnes2020, 7). She attributes this point to Haslanger:

[I]f sincere self-identification is necessary, then what do we make of infants, the severely disabled, or others who don’t have a language? Infants are viewed and treated with gendered expectations and coerced to behave as gendered beings, and pre- and non-linguistic females are sexually abused, raped, and killed, all driven by sexist ideology. (Haslanger (Reference Haslanger2016) in response to Jenkins (Reference Jenkins2016))

This objection has a particular bite against our account as self-identification of the subject is a necessary component for assessing gendered propositions. We take this point seriously since to have a theory that harms marginalized and vulnerable individuals would go against our aims and feminist goals more broadly. As such, we’ll provide a possible answer that we take to give a way of assigning truth values to gender sentences involving those who cannot self-identify whilst at the same time granting gender sentences non-trivial truth values.

In response to the above challenge, we take a similar line to Zeman (Reference Zeman2020).Footnote 27 Zeman argues that in the case where someone is unable to have a sense of gender identity, we should “bite the bullet” and say that the truth value of a sentence like WOMAN is indeterminate (Reference Zeman2020, 775). The reason is that we do not know the element (namely self-identification) that establishes truth values, that is, we are in an epistemically deficient state to say whether WOMAN is true or false. Zeman goes on to say that such a strategy is “compatible with ascriptions of gender to the cognitively impaired for practical purposes” (Zeman Reference Zeman2020, 775, added emphasis), thus we might assign WOMAN a value if there is a practical reason to do so. The resources available to gender relativism accommodate this proposal, as we now show.Footnote 28

As noted in the previous section, assessment-sensitive relativism allows exocentric judges or perspectives,Footnote 29 i.e. perspectives other than the speaker’s. For example, in trying to convince a child to eat some broccoli X might utter:

-

(11) Broccoli is tasty.

By uttering (11) X need not think that broccoli is tasty, she might hate broccoli. Instead, X is adopting the child’s perspective. When evaluating (11) we do not look for X’s perspective in the context of assessment but rather the child’s and evaluate the truth of the proposition according to the tastes of the child. Before we find out whether the child does or does not find broccoli tasty, we may operate as if they do for practical purposes—we act as if (11) is true because broccoli is healthy. Importantly, (11) will not automatically be true just because we take it to be true, it will be true iff the child finds broccoli tasty. The matter concerning the truth value of (11) will only be settled once we know if the child likes broccoli. We propose that adopting something akin to an exocentric perspective for gender terms could help with Barnes’s concern.

Where an individual cannot self-identify yet there is a need to assign a gender to them (perhaps to address some of the worries Haslanger and Barnes bring up) something like exocentric perspectives could be adopted. For practical purposes only, WOMAN might be classed as true. However, this does not mean that we render WOMAN as actually true since there is no way to know the individual’s gender. As pointed out by a referee, this is where a clear difference between exocentric perspectives in (11) and individuals who cannot self-identify lies. Whilst there is a matter of fact whether the child finds broccoli tasty (hence the truth value could, in principle, be settled), there is no such fact when it comes to cognitively disabled individuals under consideration. In other words, the actual truth value of WOMAN is not settled and could never be settled. So, acting as if WOMAN is true might be useful for practical purposes but given that the truth value is indeterminate, we refrain from actually assigning a gender to someone on the basis of their sex.

A further possible worry concerns dead individuals who no longer have the capacity to self-identify. Should X pass away, would WOMAN be true or false? Given that we knew how X identified prior to her death, we could confidently assign the truth value of true to WOMAN (although “X was a woman” would be more appropriate given that “is” implies existence). However, if we had no clue how X identified, we should refrain from assigning WOMAN a definite truth value as the matter would be beyond our power to settle. This idea is captured nicely by Jaques’s discussion of D.’s piece she heard at the 2008 Transfabulous festival:

D. moved on to work—digging up mass graves from the Srebrenica massacre of 1995, struggling to make sense of the bodies. Ninety-eight percent of the time it’s possible to identify which sex you were born as by the bones of the pelvis … But it’s not possible to tell what gender you lived as or what religion you believed in or what nationality you called yourself. (Jaques Reference Jaques2015: 143)

In some cases, we will never know the gender identities of the dead. But, of course, this is an observation about our epistemic state, not those individuals’ actual genders.

Whilst adopting something like an exocentric perspective might be useful for practical purposes, this should only be licenced in cases where the subject of the sentence does not have the means to self-identify. We are not proposing a system similar to Díaz-León’s where the best political/moral considerations would decide the meaning (or truth values in our case). For us, self-identification is the default, and it trumps all of the other considerations. We may adopt exocentric perspectives only when there’s no way for the subject to self-identify but the actual truth value of an utterance will always depend on the subject and in such cases, they will be indeterminate.

7. Conclusion

In this paper, we have provided a new argument for the context sensitivity of gender terms which, importantly, does not rely on the intuition that terms like woman shift between gender and sex terms across contexts. On our view, woman and man always denote gender not sex, but are context sensitive nonetheless because gender is determined by sincere self-identification and one’s gender identity can be subject to retraction. Gender relativism, we submit, is the best semantic theory to accommodate this.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and thorough comments. We would also like to thank the audience of University of Manchester research seminar for their feedback on an early draft of this paper as well as Lucija Duda for literature recommendations.

Justina Berškytė is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Manchester on a project titled “The Language of Misogyny: Meaning, function and possible interventions.” Her research interests lie in socially important language and their functions (gender terms, slurs, online speech, etc.), the semantics of context sensitivity especially in the debates between contextualism and relativism. She is also interested in ideologies, social identities, and masculinities/femininities.

Graham Stevens is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Manchester. His research focuses on issues on context sensitivity in the semantics of natural language, especially the semantics of indexicality and semantic relativism. He has explored applications of theories in these areas to the semantics of slurs and to issues in feminist philosophy of language. In addition to his work in philosophy of language, he also works on the history of analytic philosophy, often combining the two areas of research.