Autism spectrum disorder (hereafter autism) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by social communication differences and restricted/repetitive behaviours that begin in early childhood and persist over time. 1 In addition to core autistic traits, autistic children may often present with mental health difficulties, including internalising and externalising behaviours at preschool age. Reference Guerrera, Menghini, Napoli, Di Vara, Valeri and Vicari2 Externalising behaviours, including irritability, aggression, self-injurious behaviour or temper tantrums, might be a presentation of frustration arising from the difficulties in expressing one’s needs. Reference Fung, Mahajan, Nozzolillo, Bernal, Krasner and Jo3 Studies have reported that autistic preschoolers and children often exhibit clinically significant aggression towards either a caregiver or another person. Reference Kanne and Mazurek4 Autistic children might also have conflicts with colleagues or authority figures due to psychosocial and confrontation skill differences. Reference Nazeer5 Because irritability and other behaviours of concern commonly co-occur in autistic individuals, and these behaviours may jeopardise educational and recreational activities and even lead to in-patient psychiatric hospitalisation or residential placements, it is crucial to address and prevent these adverse behaviours with early intervention and supports. Reference McGuire, Fung, Hagopian, Vasa, Mahajan and Bernal6

Studies have shown that internalisation of symptoms is common in autistic preschoolers, with anxiety and depression being the most frequent presentations. Reference Guerrera, Menghini, Napoli, Di Vara, Valeri and Vicari2 A study by Lugnegård et al Reference Lugnegård, Hallerbäck and Gillberg7 reported that autistic young adults may be more vulnerable to anxiety because they are more aware of their differences in interpreting social cues. Similarly, autistic adults with more subtle social challenges may be at increasing risk of developing depressive symptoms. Reference Sterling, Dawson, Estes and Greenson8 There is also evidence to suggest higher rates of withdrawn/depressed, specific phobias and separation anxiety among autistic preschoolers compared with non-autistic preschoolers. Reference Chan, Fenning and Neece9 Because these internalising behaviours may increase the severity of repetitive behaviours, social communication differences and sensory deficits, further research into appropriate strategies to address these features deserves greater attention.

Because mental health difficulties commonly co-occur in autistic individuals, and these behaviours may impact access and participation in educational and recreational activities, it is important to support such issues with early interventions and support. Reference Kaat, Lecavalier and Aman10 While there is research demonstrating a link between autism diagnosis and mental health difficulties, these studies were mostly carried out in school-aged children and adolescents. Reference Guerrera, Menghini, Napoli, Di Vara, Valeri and Vicari2 Additionally, other studies Reference Bacherini, Igliozzi, Cagiano, Mancini, Tancredi and Muratori11,Reference Rescorla, Kim and Oh12 that have examined this association among preschool populations were of small sample size, which may not accurately represent the wider population, making it difficult to draw reliable or generalisable conclusions. Furthermore, there is also a scarcity of reports exploring these associations with a social determinant of health lens that also takes into account critical psychosocial factors. To address this knowledge gap, this study examined mental health difficulties identified using the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL), and their association with core autistic traits, cognitive level and adaptive functioning alongside key sociodemographic factors, among a large sample of autistic preschoolers in Australia.

Method

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the University of New South Wales Institutional Human Research Ethics Committee (no. HC14267).

Study design, setting, recruitment, participants and consent

Study findings are reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines. Reference Von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke13 The study is a secondary data analysis utilising data from six Australian Autism Specific Early Learning and Care Centres (ASELCCs) as part of the Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism (Autism CRC) ‘Autism Subtyping Project’. Reference Masi, Dissanayake, Alach, Cameron, Fordyce and Frost14 All children in the ASELCCs that met the criteria for autism diagnosis based on either DSM-IV or DSM-5, 1 or had features consistent with an autism diagnosis, were invited to participate in the study. No other inclusion or exclusion criteria, nor pre-screening measures, were applied. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s) for all procedures performed.

Families from each centre that were interested in the study were provided with the same set of questionnaires to complete; arrangement of time required to complete researcher-administered assessments was undertaken by either professional staff at each ASELCC or a research assistant who had been trained to research reliability. Relevant staff also attended formal training to administer the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – Second Edition (ADOS-2). Further details about the intervention and study procedures are detailed elsewhere. Reference Masi, Dissanayake, Alach, Cameron, Fordyce and Frost14

Study measures

CBCL

CBCL 1.5–5 is a self-reported questionnaire, for parents of children aged 1.5–5 years, that consists of 100 behavioural items designed to assess emotional and behavioural issues. Reference Achenbach and Rescorla15 It comprises eight subscales that can be classified into (a) emotionally reactive, (b) anxious/depressed, (c) somatic complaints and (d) withdrawn syndromes (a–d comprise the internalising score); (e) aggressive behaviour and (f) attention problems syndrome (e–f comprise the externalising score); and (g) a sleep problem score and (h) other problems (g–h comprise the score for other problems). The total score was calculated by summing all eight subscales. The study also utilised this scale in determining the categories of the study subjects: children with t-scores ≤59 were classified as not having any behavioural issues, while t-scores ≥60 but ≤64 were classified as at risk and t-scores ≥65 considered as clinical. Reference Guerrera, Menghini, Napoli, Di Vara, Valeri and Vicari2 CBCL has been found to be a valid and reliable measure for childhood behaviour concerns, with strong internal consistency; in the current study, there was excellent internal consistency for the CBCL externalising scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90) and CBCL total (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93), while it was slightly lower and yet robust for CBCL internalising scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86). For the purposes of this study, CBCL total, internalising and externalising scores were used as outcome measures.

ADOS-2

ADOS-2 is an assessor-led, semi-structured, standardised diagnostic observational assessment used to confirm autism diagnosis. Reference Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, Risi, Gotham and Bishop16 It contains specific developmental and language level-dependent modules (modules 1–3) that examine autistic traits in two domains – restricted and repetitive behaviours (RRB) and social affect. To account for differences between modules, scores for RRB and social affect domains, as well as total score were converted into calibrated severity scores based on previous validation studies, in which comparisons with the severity of autism symptomatology across modules can be carried out; a higher score indicates greater severity. Reference Hus, Gotham and Lord17

SCQ

The Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) is a self-reported, 40-item questionnaire that measures autistic traits in the social communication domain. Reference Lord, Michael and Rutter18 The SCQ is completed by parents with either a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response covering reciprocal social interaction, language and communication and repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, with a higher score indicating greater severity. The current study showed good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89) internal consistency between items.

RBS-R

Repetitive Behaviour Scale – Revised (RBS-R) is a 43-item, parent-completed questionnaire that measures repetitive behaviours in autistic children, adolescents and adults. Reference Lam and Aman19 It is divided into six subscales of behaviours: stereotyped, self-injurious, compulsive, ritualistic, sameness and restricted behaviour. It is scored on a 3-point scale, with 0 indicating not present and 3 indicating a severe concern. The total score is computed, with a higher score indicating greater severity. For the current study, there was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94) internal consistency between items.

MSEL

The Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) assesses children’s development across key domains including language, motor, perceptual abilities, cognitive ability and motor development. Reference Mullen20 The assessment provides four subscales (visual reception, fine motor, receptive and expressive language) and a standardised and age-equivalent overall early learning composite. In the current study, raw scores of the first three domains and a corresponding age-equivalent score were obtained. A standardised developmental quotient ((age equivalent/chronological age) × 100) was calculated for both non-verbal (mean fine motor and visual reception) and verbal (mean receptive and expressive language) domains, Reference Messinger, Young, Ozonoff, Dobkins, Carter and Zwaigenbaum21 where a higher score indicates better cognitive functioning.

VABS-II

The Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales, second edition (VABS-II) parent/caregiver rating form assesses an individual’s adaptive functioning in five domains: communication, daily living skills, socialisation, motor skills and maladaptive behaviour. Reference Sparrow, Balla, Cicchetti and Doll22 All items on VABS-II are scored as either 0 (behaviour never performed/never occurs without help), 1 (behaviour is sometimes performed without help or reminders) or 2 (behaviour usually occurs without help). Adaptive behaviour composite scores were computed by summing the scores from the 4 domains (except maladaptive behaviour); these ranged from 20 to 160, where a higher score indicates better adaptive functioning.

Sociodemographic factors

Sociodemographic items included the child’s age (in years) and gender (male, female); parent’s age (in years); culturally and linguistically diverse background (CALD) status (refers to people born in non-English-speaking countries and/or who do not speak English at home Reference Pham, Berecki-Gisolf, Clapperton, O’Brien, Liu and Gibson23 ) (yes, no); sibling’s autism diagnosis (no, yes); caregiver’s disability status (no, yes); carer’s level of education (primary/secondary, postgraduate/tertiary); occupation (professional/paraprofessional, other labour); and annual family income (in Australian dollars (AUD), <AUD40 000, AUD40 001–85 000, AUD85 001–115 000, >AUD115 000).

Data analysis

The characteristics of the sample were analysed using descriptive statistics, and are presented as mean and standard deviations for continuous measures and as frequency counts with percentages for categorical measures. Given the missing data in the sample, multiple imputation using chained equations was applied Reference Azur, Stuart, Frangakis and Leaf24 and variables with <50% missingness on the CBCL were imputed. Multiple imputation makes repeated draws from the model of distribution of variables and provides valid values using other available information from the data-set. Reference Rubin25 Incomplete variables were imputed under fully conditional specification and combined using Rubin’s rules. The scores for each subscale (e.g. withdrawn subscale, internalising scale or total) were recalculated using imputed estimates. These recalculated scores were also compared against the non-imputed subscale scores to ensure that there were no significant differences that might impact the mean.

A univariate linear regression was first carried out to determine the independent association of each independent variable against the outcome variable. Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to determine any significant correlation between each of the clinical indicators and sociodemographic variables. With the large number of sociodemographic, cultural and socioeconomic variables, only variables with a P-value ≤0.20 in the univariate regression analysis, and those not significantly correlated, were entered into the multivariable models. This approach in statistical modelling helps to reduce potential overfitting and noise from other highly non-significant variables in the univariate model, as well as improving model interpretability. This less stringent cut-off (e.g. P ≤ 0.20 rather than the conventional 0.05) helps in avoiding the exclusion of potentially important predictors that may become significant when adjusting for confounders in the multivariate analysis. Reference Chowdhury and Turin26

A multivariable regression analysis model was carried out to examine the association between autistic and child features, including social communication differences, repetitive behaviours, cognitive level, adaptive functioning (predictors) and mental health challenges (CBCL internalising, externalising and total score) as outcome variables adjusted for sociodemographic variables. Additionally, we also examined associations among key sociodemographic variables against the mental health challenges. Findings from the regression models are reported as standardised beta coefficient (β) with 95% confidence interval and P-value (P). All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v.28 (SPSS for macOS, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA, https://www.ibm.com/products/spss) and R language v.3.6.1 within RStudio IDE (for macOS, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://cran.r-project.org).

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the sample

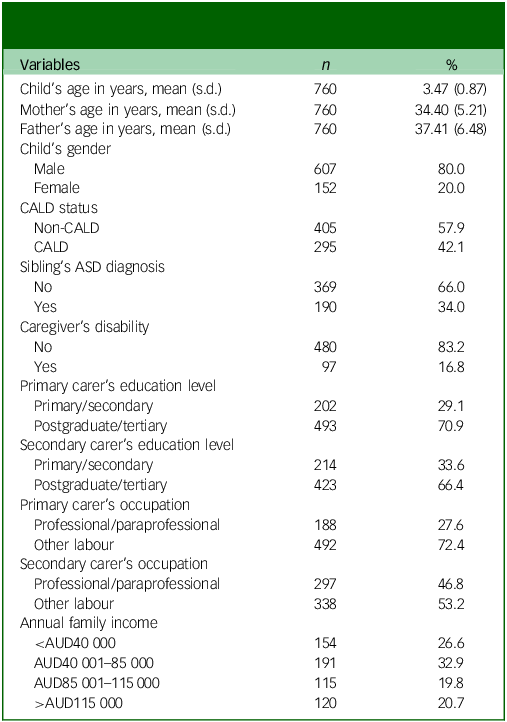

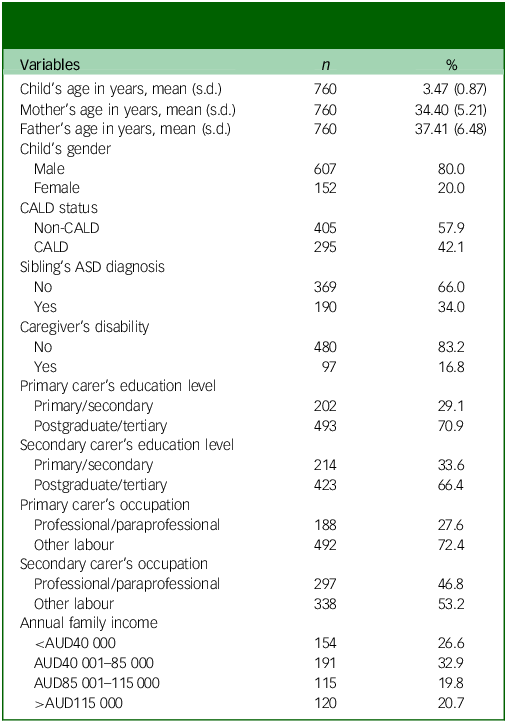

The descriptive characteristics of the children and their families are outlined in Table 1. The average age of the participants was 3.47 ± 0.87 years, and 80% were male. Around a third of the total sample had an autistic sibling and 42.1% of the total sample were from a CALD background.

Table 1 Baseline demographic characteristics (N = 760) of autistic children and their parents/caregivers

CALD, culturally and linguistically diverse; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; AUD, Australian dollar.

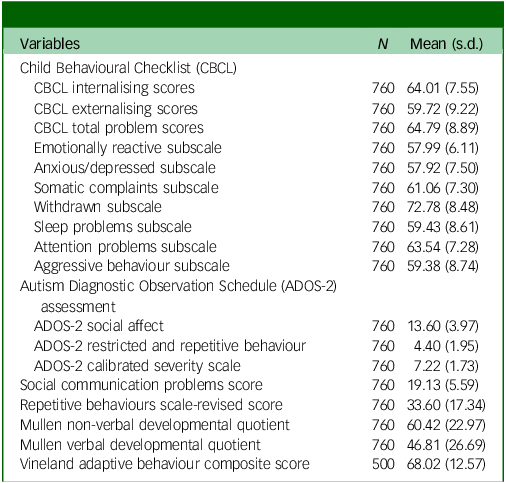

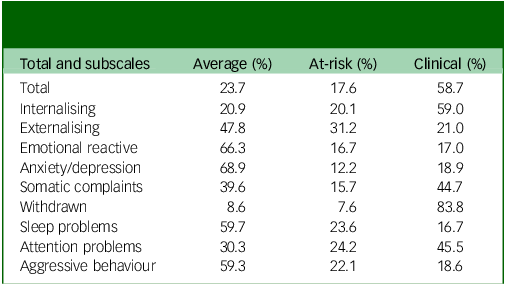

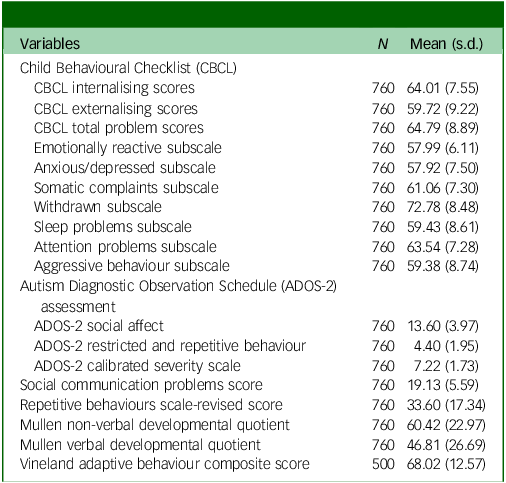

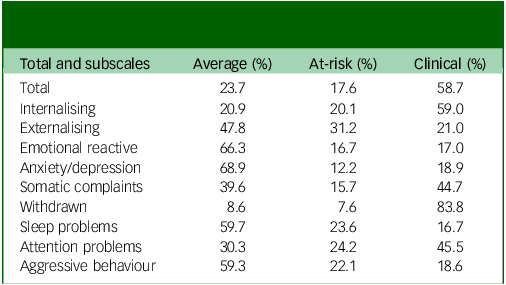

The baseline characteristics of autistic features, cognitive and adaptive functioning, as well as mental health issues, are detailed in Tables 2 and 3. Regarding mental health difficulties, 59% reported internalising concerns, 21.0% reported externalising behavioural challenges and 58.7% exhibited overall behavioural difficulties. Out of the seven CBCL subscales, three behavioural problems (withdrawn problem, attention problems and somatic complaints) had more children in the at-clinical group than the average group.

Table 2 Behavioural and cognitive measures of autistic children

Table 3 Frequency of autistic children in average and at-risk/clinical groups for total Child Behavioural Checklist and subscales (N = 760)

Associations among autistic features, cognitive and adaptive functioning and mental health difficulties

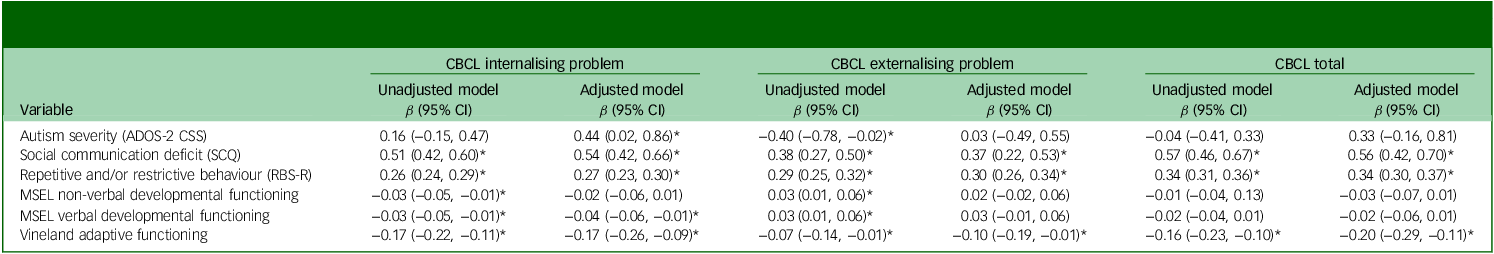

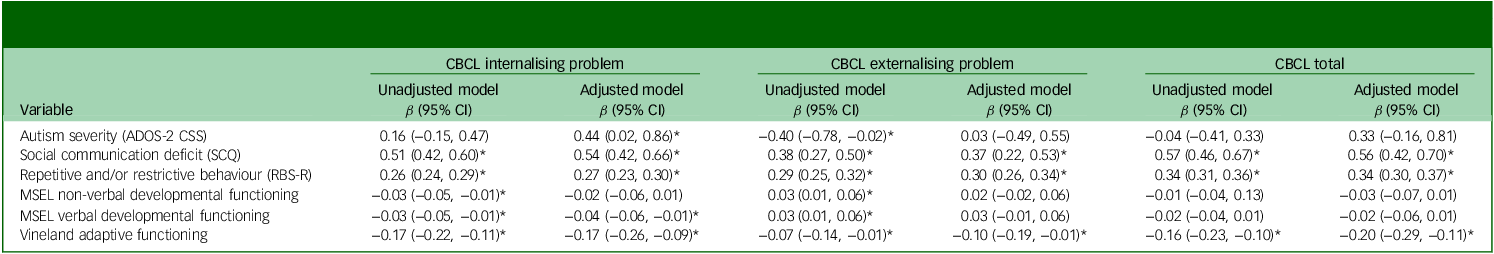

Findings from the multivariable linear regression models showing associations between mental health difficulties and autistic traits are shown in Table 4.

Table 4 Multi-level linear regression analysis with behavioural, communication, cognitive and adaptive traits associated with CBCL internalising and externalising problems (unadjusted and adjusted models, adjusted for sociodemographic covariates)

CBCL, Child Behavioural Checklist; ADOS-2, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule − Second Edition; CSS, calibrated severity score; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire; RBS-R, Repetitive Behaviour Scale − Revised; MSEL, Mullen Scale of Early Learning. *P < 0.05.

Consistent with the univariate models, findings from the multivariable models showed that higher scores on both social communication difficulties and repetitive and/or restricted behaviours were significantly associated with higher internalising (β = 0.54, 95% CI 0.42, 0.66), externalising (β = 0.37, 95% CI 0.22, 0.53) and total problem scores (β = 0.56, 95% CI 0.42, 0.70). On the other hand, higher adaptive functioning was associated with lower internalising (β = −0.17, 95% CI −0.26, −0.09), externalising (β = −0.10, 95% CI −0.19, −0.01) and total problem scores (β = −0.20, 95% CI −0.29, −0.11). Furthermore, greater severity of autistic symptoms was significantly associated with higher internalising behaviours (β = 0.44, 95% CI 0.02, 0.86) but not with externalising or total problems. Additionally, higher scores on verbal developmental functioning were significantly linked to lower internalising behavioural problems (β = −0.04, 95% CI −0.06, −0.01).

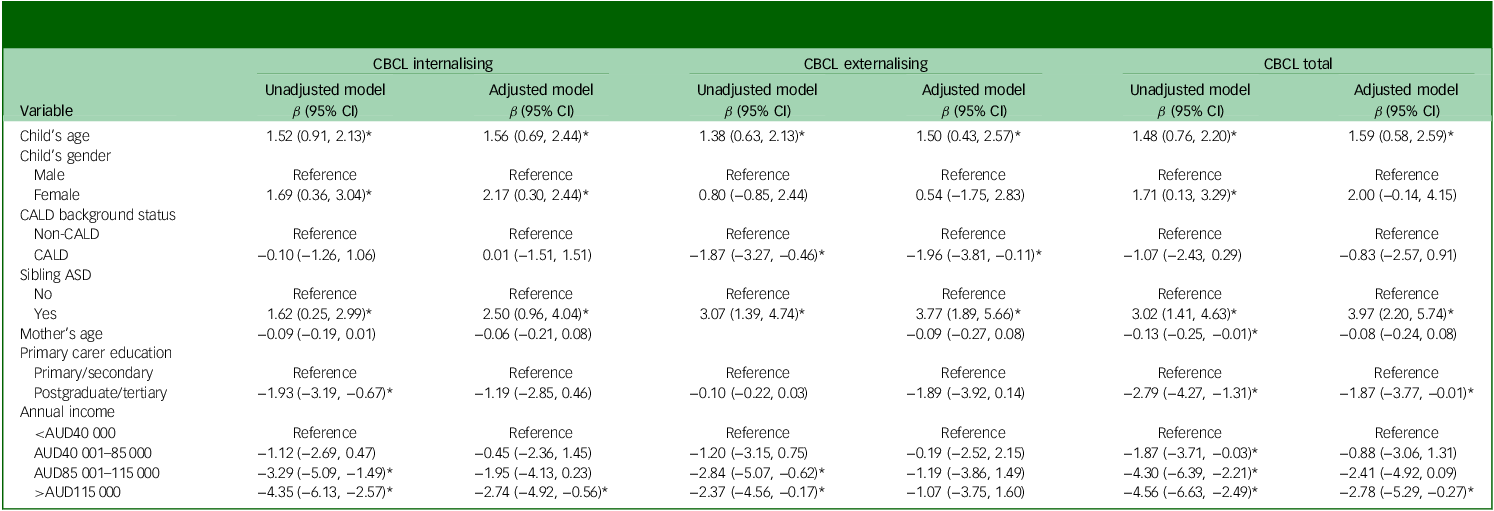

Associations among sociodemographic and sociocultural factors and mental health difficulties

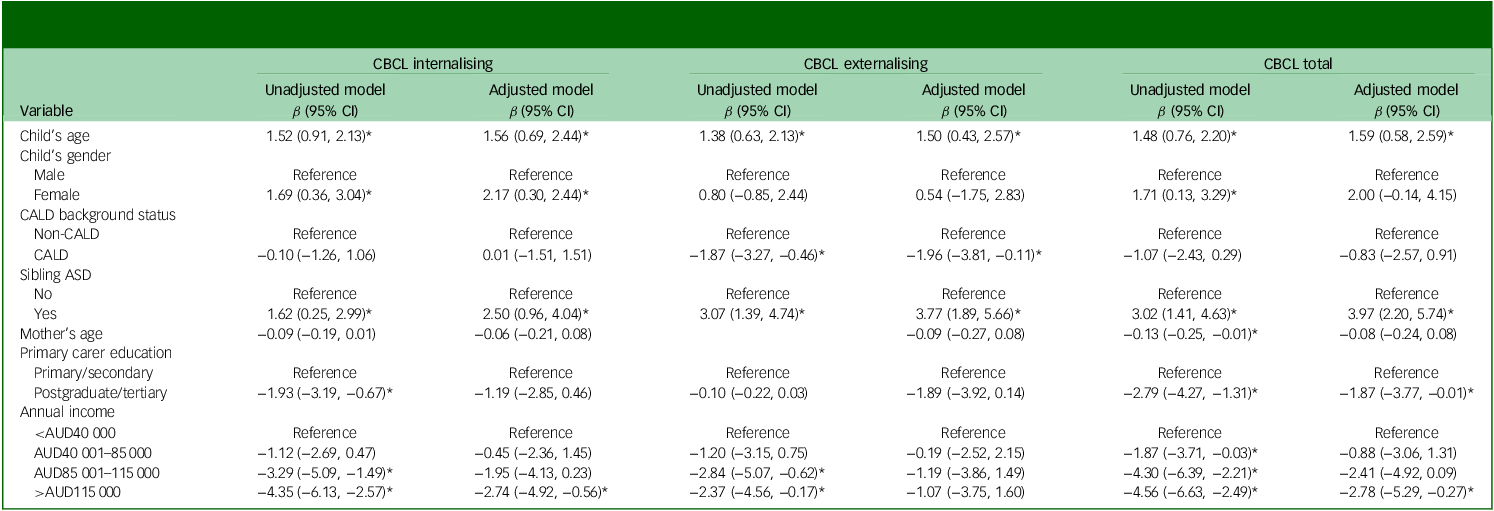

The associations among mental health challenges and sociodemographic factors were also examined (Table 5). Findings showed that increase in children’s age was associated with higher internalising (β = 1.56, 95% CI 0.69, 2.44), externalising (β = 1.50, 95% CI 0.43, 2.57) and total problems (β = 1.59, 95% CI 0.58, 2.59). Compared with males, females reported significantly higher internalising problems (β = 2.17, 95% CI 0.30, 2.44). Furthermore, compared with siblings without an autistic diagnosis, children with an autistic sibling reported significantly higher internalising (β = 2.50, 95% CI 0.96, 4.04), externalising (β = 3.77, 95% CI 1.89, 5.66) and total problems (β = 3.97, 95% CI 2.20, 5.74).

Table 5 Multi-level linear regression analysis showing sociodemographic factors associated with CBCL internalising, externalising and total problem (unadjusted and adjusted models, adjusted for behavioural, communication, cognitive and adaptive traits)

CBCL, Child Behavioural Checklist; CALD, culturally and linguistically diverse; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; AUD, Australian dollar. *P < 0.05.

Interestingly, children from a CALD background were reported as having significantly lower externalising problems (β = −1.96, 95% CI −3.81, −0.11). Furthermore, higher levels of parental education were associated with significantly lower total problems (β = −1.87, 95% CI −3.77, −0.01), and annual family income was also protective against both internalising (β = −2.74, 95% CI −4.92, −0.56) and total problems (β = −2.78, 95% CI −5.29, −0.27).

Discussion

Summary of findings

This study aimed to determine the association between behavioural and mental health challenges in autistic preschoolers and their association with autistic traits, cognitive level, adaptive functioning and sociodemographic factors. The findings of this study provide useful insights into the high prevalence of mental health difficulties, via CBCL internalising, externalising and total problem scores, among autistic preschool children. The study found a significant association between autistic traits and mental health difficulties. Additionally, sociodemographic factors such as being older, female and having a sibling with autism, were linked to a higher risk of mental health challenges, while a CALD background, higher parental education level and greater family income appeared to offer a protective effect.

Prevalence of mental health challenges

This study found that behavioural concerns are common among autistic preschoolers, occurring in as many as three-quarters of children. This is consistent with the findings of Guerrera et al, Reference Guerrera, Menghini, Napoli, Di Vara, Valeri and Vicari2 who found that around 50% of autistic children exhibited CBCL total scores in the at-risk or clinical range. Because that previous study looked at an older sample (ages 2.6–17.8 years, mean 5.45 years), it is possible that the relatively lower rates seen were a function of the decline in behavioural concerns as children age. Furthermore, it has been shown that externalising behaviours may be more common at lower severities at a younger age, Reference Guerrera, Menghini, Napoli, Di Vara, Valeri and Vicari2 while our findings suggest higher rates of internalising behaviours in the preschool age group. While this finding of higher internalising than externalising behaviours is also consistent with that of Guerrera et al, Reference Guerrera, Menghini, Napoli, Di Vara, Valeri and Vicari2 the overall rate for both internalising and externalising behaviours in this study was higher. This might be due to the fact that the children in the current study were attending a specialised early intervention programme for autistic children, whereas those in the study of Guerrera et al were attending neuropsychiatry out-patient units for clinical assessments and rehabilitative follow-ups.

The high prevalence of emotion regulation issues in autistic preschoolers, and their limited capacity for self-regulation to help control their emotion, attention and activities, may manifest as either internalising or externalising behaviours. Reference Nuske, Hedley, Tseng, Begeer and Dissanayake27 Also, it is possible that in the early years the fears or worries (internalising behaviours) that they experience will manifest more as externalising behaviours, based on family and contextual factors such as parental and family functioning. Reference Nuske, Hedley, Tseng, Begeer and Dissanayake27 Given the heterogeneity in the development of internalising and externalising behaviours in autistic preschool children, and the limited knowledge about the development of these behaviours in either isolation or combination, Reference Guerrera, Menghini, Napoli, Di Vara, Valeri and Vicari2 further research into autistic preschoolers is warranted. Furthermore, our findings are also in keeping with previous studies that have reported higher prevalences of withdrawal, Reference Ooi, Rescorla, Ang, Woo and Fung28,Reference Kim and Ha29 attention difficulties Reference Kim and Ha29 and somatic complaints Reference Leader, Flynn, O’Rourke, Coyne, Caher and Mannion30 relative to other subscales.

Association between mental health difficulties and autistic traits

The finding that autistic children with high repetitive and/or restricted behaviours had more internalising and externalising behaviours is consistent with the existing literature. Reference Rodgers, Glod, Connolly and McConachie31 This might be explained by the fact that, when autistic children are anxious, they may attempt to control their environment to overcome further stimulation, uncertainty and consequent increase in anxiety by using RRBs such as restricted interests and insistence on sameness as a coping behaviour. Reference Rodgers, Glod, Connolly and McConachie31 Furthermore, we found that children with greater social communication differences exhibited higher internalising and externalising behaviours, consistent with findings from prior studies. Reference Kim and Ha29,Reference Leader, Flynn, O’Rourke, Coyne, Caher and Mannion30 Such differences may hinder their ability to interpret others’ emotions, express their own feelings and assess social responses, Reference Mazefsky, Herrington, Siegel, Scarpa, Maddox and Scahill32 making social interactions seem unpredictable. This can evoke fear (internalising) or frustration (externalising), creating a cycle of awkward peer interactions, social withdrawal and heightened anxiety or, conversely, tantrums and aggression. Reference Li, Bos, Stockmann and Rieffe33

Our study’s finding that higher levels of adaptive functioning and verbal developmental functioning are linked to lower internalising and externalising problems aligns with established developmental and clinical theories. Reference Phillips34 Enhanced adaptive skills may serve as protective factors against psychopathology by facilitating more effective communication, reducing frustration and enabling positive social interactions with peers and caregivers. These skills increase opportunities for meaningful participation in daily activities and social contexts which, in turn, supports emotional regulation and behavioural adjustment. Reference Donoso, Rattray, De Bildt, Tillmann, Williams and Absoud35 Verbal developmental functioning further contributes by providing children with the tools to express needs and emotions verbally rather than through maladaptive behaviours, thereby reducing internal distress and externalising reactions. Reference Chow, Ekholm and Coleman36 Together, these capacities may help buffer children from developing significant mental health difficulties by fostering adaptive coping strategies and resilience within social environments.

Association between mental health challenges and sociodemographic covariates

Besides autism severity and autistic features, several sociodemographic and sociocultural factors were found to be significantly associated with mental health challenges. Older-aged children exhibited more internalising, externalising and total behaviours than younger children, which might be related to the difficulty in adjusting their behaviours to the changing social and environmental demands, which was greater in older autistic children than in younger ones. Reference Guerrera, Menghini, Napoli, Di Vara, Valeri and Vicari2 Gender played a key role, whereby girls reported a higher likelihood of internalising behaviours than boys, which may be linked to the differences in developmental mechanisms and trajectories in autistic females and males. Reference Stephenson, Norris and Butter37 Consistent with previous research, autistic children with an autistic sibling in our sample showed higher internalising, externalising and total behaviour problem scores. This may reflect a combination of shared genetic liability for emotional and behavioural difficulties, as well as environmental stressors within families raising multiple autistic children. Reference Sandin, Lichtenstein, Kuja-Halkola, Hultman, Larsson and Reichenberg38

Interestingly, children from CALD backgrounds were reported to have significantly lower externalising problems, suggesting that cultural norms emphasising behavioural restraint, respect for authority and strong family cohesion may act as protective factors against overt behavioural difficulties. Reference Yap, Cheong, Zaravinos-Tsakos, Lubman and Jorm39 Additionally, the protective role of parental education and family income in behaviours of concern is consistent with prior evidence that higher education and higher family income may equip parents with greater knowledge, problem-solving skills and access to resources that support child emotional and behavioural regulation. Reference Fuller-Thomson and Sawyer40,Reference Kohen and Guèvremont41

Strengths, limitations and directions for future research

This study has several strengths and limitations. Among the key strengths is the inclusion of its large and well-characterised clinical sample drawn from six Australian ASELCCs, which enhances the relevance of findings to children accessing specialised early intervention services. Furthermore, the use of validated measures for autistic traits, cognitive and adaptive functioning and mental health difficulties, combined with multivariable regression analyses, strengthens the robustness of the observed associations. However, we also note several limitations. Due to the nature of the cross-sectional data, causal inferences and developmental trajectories could not be examined. The sample’s restriction to ASELCC attendees may have limited generalisability to the wider autistic population, potentially introducing selection bias. Additionally, reliance on parent-reported instruments could have introduced reporting bias and may not fully capture the complex mental health profiles seen in autism. Future research should aim to build on these findings by employing longitudinal designs to elucidate the developmental trajectories and causal pathways linking autistic traits, adaptive functioning and mental health outcomes. Additionally, expansion of research to include broader community samples beyond specialised early learning centres will enhance generalisability.

Implications for policy and practice

The findings of this study underscore the critical importance of early and comprehensive assessment of, and support for, autistic features, adaptive functioning, verbal skills and mental health difficulties among preschool children. Given the protective role of adaptive and verbal developmental functioning, interventions that enhance communication and daily living skills may be particularly beneficial in mitigating internalising and externalising problems. Furthermore, the inextricable link between sociodemographic and sociocultural factors and mental health challenges underscores the need for family-centred, culturally sensitive approaches and equitable access to resources, ensuring that families from diverse backgrounds receive appropriate and tailored support.

Data availability

The data-sets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data governance arrangements. However, aggregate de-identified data may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the ASELCCs, service providers and researchers, including Professor Cheryl Dissanayake, who have contributed to this programme from conception, and others over different time periods: South Western Sydney, New South Wales: KU Marcia Burgess ASELCC (KU Children’s Services) and Ms Elizabeth Aylward; Brisbane, Queensland: ASELCC – AEIOU for Children with Autism (AEIOU Foundation) and Dr Jessica Paynter; Adelaide, South Australia: Anglicare – SA, Daphne Street Child Care and Specialist Early Learning Centre (Anglicare South Australia Inc.); North West Tasmania: North West Tasmania ASELCC (St Giles Society) and Dr Colleen Check, Ms Miranda Stephens and Dr Damhnat McCann; Melbourne, Victoria: Margot Prior ASELCC, La Trobe University Community Childrens Centre (La Trobe University), Dr Giacomo Vivanti and Dr Kristelle Hudry; Perth, Western Australia: First Steps Autism Day Care (The Autism Association of Western Australia), Dr Annette Jooston and Dr Nigel Chen. The authors acknowledge the financial support of Autism CRC, established and supported under the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centres Program. The authors acknowledge access to the Child and Family Outcome Study data that were collected from children and families attending the six ASELCCs, established through funding from the Australian Government Department of Social Services. The authors also acknowledge Professor Alison Lane for input to the early draft of the manuscript.

Author contributions

J.R.J., A.M.D. and V.E. assisted in conceptualisation of the research question. V.E. was involved in the design of the autism subtyping study from which the data were drawn. J.R.J. and W.T.W. conducted data analysis. W.T.W. drafted the manuscript with input from J.R.J., A.M.D. and V.E. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support of Autism CRC (no. 1.023RU, Autism Subtype project), established and supported under the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centres Program.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Transparency declaration

The manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.