Introduction

Climate change is a long-term policy problem that requires drastic near-time cuts in carbon emissions to safeguard the well-being of future generations (IPCC 2018, 2022). Many high-emitting, affluent democracies, such as Canada, Germany, Japan, and the UK, have pledged since the 2015 Paris agreement to reach ‘net zero’ emissions by 2050 (Höhne, Gidden, den Elzen et al. Reference Höhne, Gidden, den Elzen, Hans, Fyson, Geiges and Rogelj2021). Yet implementing the policies capable of achieving that goal will require a significant and sustained level of political will and leadership over the next decades to come (Boasson and Tatham Reference Boasson and Tatham2023; Jordan, Lorenzoni, Tosun et al. Reference Jordan, Lorenzoni, Tosun, i Saus, Geese, Kenny and Schaub2022). A key obstacle to such leadership appears to be that, although general public support for climate change mitigation is often diffusely present, many concrete decarbonisation policies concentrate the short-term transformation costs in geographically defined communities, thereby leading to spatial patterns of climate policy opposition (Anderson, Butler, Harbridge-Yong et al. Reference Anderson, Butler, Harbridge-Yong and Markarian2023; Bolet, Green and González-Eguino Reference Bolet, Green and González-Eguino2024; Finseraas, Høyland and Søyland Reference Finseraas, Høyland and Søyland2021; Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley Reference Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley2022; Kono Reference Kono2020; Stokes Reference Stokes2016). Thus, for politicians operating under the constraints of 4–5-year-long election cycles, a major political challenge lies in the reconciliation of their short-term and often geographically defined political pressures with the long-term vision of net zero.

In this paper, we put the spotlight on how members of parliament (MPs) in the UK’s constituency-based electoral system handle that challenge when they represent constituents whose lifestyles are particularly carbon-intensive. Our focus on local consumption-based carbon emissions is a novel and important contribution to the existing literature on climate politics. Given that cutting private households’ emissions is crucial for the achievement of net zero goals in affluent democracies like the UK (Committee on Climate Change 2019, p. 155; Skidmore Reference Skidmore2023; Whitmarsh, Steentjes, Poortinga et al. Reference Whitmarsh, Steentjes, Poortinga, Beaver, Gray, Skinner and Thompson2021), the politics behind this task warrants much more attention from political researchers. Arguably, overcoming the current carbon lock-in of consumer behaviour is particularly challenging in political terms, given that it requires significant lifestyle changes at the individual level, with the scale of changes needed not necessarily being obvious to consumers (eg Capstick, Khosia and Wang Reference Capstick, Khosia and Wang2021; Cass, Lucas, Adeel et al. Reference Cass, Lucas, Adeel, Anable, Buchs, Lovelace, Morgan and Mullen2022; Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig et al. Reference Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig, Dietz and Stern2021; Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick et al. Reference Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick, Whitmarsh and Poortinga2023). Moreover, the issue of cutting consumption-based carbon emissions raises the question of whether high-emitting individuals should shoulder more of those lifestyle changes and hence spurs perceptions of (in)justice (Dolšak and Prakash Reference Dolšak and Prakash2022, p. 285). Indeed, the moral responsibility of cutting carbon emissions is commonly attributed to those who disproportionally cause them (Cass, Lucas, Adeel et al. Reference Cass, Lucas, Adeel, Anable, Buchs, Lovelace, Morgan and Mullen2022; Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig et al. Reference Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig, Dietz and Stern2021).

For the first time, we thus set out to explore this conundrum in the UK political context. Our main argument is that, although constituencies with a high consumption-based carbon footprint present a considerable potential to contribute to nationwide emissions cuts (Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh Reference Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh2025; Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig et al. Reference Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig, Dietz and Stern2021), MPs representing these geographies have an incentive to disengage from decarbonisation politics. Drastically bringing down private household emissions would require considerable lifestyle changes (Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick et al. Reference Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick, Whitmarsh and Poortinga2023), which is a politically sensitive topic that MPs representing concentrations of high-emitting constituents are hesitant to make a focus of their parliamentary work.

We examine this empirically by leveraging a triangulated, mixed-methods research design that combines constituency-level data with quantitative and qualitative indicators of political behaviour. First, we study quantitatively how MPs represent their constituents’ carbon footprints politically by drawing on rare consumption-based local emissions data in England (Morgan, Anable and Lucas Reference Morgan, Anable and Lucas2021) and a corpus of over 350,000 parliamentary debate contributions of English MPs in the UK House of Commons between 2011 and 2018. Novel methodological approaches to text-as-data (TADA) (Geese, Sullivan-Thomsett, Jordan et al. Reference Geese, Sullivan-Thomsett, Jordan, Kenny and Lorenzoni2024; King, Lam and Roberts Reference King, Lam and Roberts2017) enable us to unearth large-scale statistical relationships between parliamentary behaviour and local carbon footprints. Second, to better understand MPs’ rationales underlying these large-scale empirical patterns, we supplement the analysis based on qualitative in-depth interviews with twenty sitting and retired MPs.

Results suggest that MPs are indeed responsive to the consumption-based carbon intensity of their geographic constituencies. The quantitative analysis of parliamentary speeches suggests that their propensity to engage in parliamentary decarbonisation politics declines notably as the average consumption-based carbon footprint of their constituents increases. Moreover, party affiliation as well as seat safety are important moderating factors for this relationship. First, Conservative MPs adapt their decarbonisation-related parliamentary behaviour much more strongly in response to constituents’ carbon-related lifestyles than MPs from the Labour Party do. Second, the negative association between decarbonisation-focused speeches and local carbon footprints is more pronounced for MPs holding marginal seats.

The qualitative interview evidence substantiates and puts these quantitative findings into context. Interviewed MPs confirmed that the realisation of lifestyle-changing decarbonisation is a crucial political challenge and that their electoral considerations and vulnerability play an important role in how they represent their constituents on these matters. Furthermore, partisan divides between Conservatives and Labour shape constituency representation due to clearly distinguishable ideological convictions regarding state-led lifestyle interventions and different electoral strategies following from parties’ government-opposition status.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. In the following section, we discuss in greater detail the political representation challenge of consumption-focused decarbonisation and theorise politicians’ responsiveness to voters’ carbon footprints in constituency-based democracies like the UK. In the ‘Data and methods’ section, we present our case selection rationale and provide the details of our mixed-methods research design. In the ‘Findings’ section, we present the empirical results. Thereafter, we discuss results from alternative model specifications in the ‘Robustness checks’ section. Finally, in the ‘Conclusion’ section, we summarise the main takeaway messages of our study and link them to current academic and public debates around climate action. Here, we also detail how our study contributes to the existing literature on climate politics and political responsiveness and make suggestions for future research.

Consumption-focused decarbonisation politics in constituency-based political systems

Existing literature: MPs’ re-election incentives and the territorial politics of climate change

The territorial organisation of the UK’s first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system, where MPs are elected in geographical single-member constituencies based on a simple plurality rule, is well-known to engender a strong dyadic representational relationship between MPs and their electoral constituencies (eg Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987; Fenno Reference Fenno1977; Hanretty, Lauderdale and Vivyan Reference Hanretty, Lauderdale and Vivyan2017; Kellermann Reference Kellermann2013; Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963). In such systems, MPs have been repeatedly shown to take the (perceived) needs and interests of their voters into account, for example, when they vote in parliament (Kam Reference Kam2009; Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963); in terms of what topics and positions they cover in their speeches (Blumenau and Damiani Reference Blumenau and Damiani2021, p. 794), in their parliamentary questions (Kellermann Reference Kellermann2016), on social media (Barrie, Fleming and Rowan Reference Barrie, Fleming and Rowan2024); or in terms of constituency casework (Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987; Fenno Reference Fenno1977).

While MPs may cultivate a close relationship with their constituents out of a variety of motives (Giger, Lanz and de Vries Reference Giger, Lanz and de Vries2020; Searing Reference Searing1994; Tavits Reference Tavits2010), re-election is clearly a key consideration for MPs (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). After all, re-election is a requirement for other goals desired by MPs, such as policy influence and higher office within parliament (Kam Reference Kam2009; Strøm Reference Strøm1997). In electoral systems in which the electoral fates of individual MPs depend ultimately on their constituents’ future voting decisions, MPs are incentivised to utilise their behavioural repertoire in anticipation of what their constituents might reward or sanction at the next general election (Bowler and Farrell Reference Bowler and Farrell1993; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003), for example, by strategically raising or lowering attention to certain issues, taking positions, claiming credit and/or advertising their own qualities on selected policy topics (Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987; Eulau and Karps Reference Eulau and Karps1977; Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974).

Existing research from the US and Canada suggests that MPs’ re-election considerations are also important factors shaping climate politics. Focussing on Canada, Stokes (Reference Stokes2016) shows how spatially concentrated voters punish decision makers for climate policies that enjoy widespread public support across constituencies but concentrate costs in their specific local areas, thereby sending ‘spatially distorted’ signals of policy resistance to political elites. Research from the US adds to this key finding by turning around the telescope to assess how legislators adapt their decarbonisation-related behaviour in response to voters’ spatially varied levels of short-term climate policy vulnerability. For example, Anderson, Butler, Harbridge-Yong et al. (Reference Anderson, Butler, Harbridge-Yong and Markarian2023) show that US State legislators’ support for gas taxes is stronger when their constituents have less commuting burdens and when there is good availability of public transport infrastructure. Similarly, Kono (Reference Kono2020) shows that US legislators from districts with carbon-intensive employment were less likely to vote for climate legislation. These studies thus substantiate the notion of politicians having reason to fear and anticipate a decarbonisation-related electoral backlash in the short term.

A political, consumption-focused decarbonisation perspective

In two meaningful ways, our study takes this burgeoning literature a crucial step forward. Not only do we investigate MPs’ responsiveness to geographically varied levels of local climate policy vulnerability outside of the United States, namely in the United Kingdom, but we also break new ground by investigating, for the first time, how MPs navigate the crucial political challenge of addressing constituents’ consumption-based carbon footprints.

This is an important research focus since reducing consumption-based carbon emissions is necessary in order to accomplish net-zero goals in affluent democracies like the UK (Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick et al. Reference Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick, Whitmarsh and Poortinga2023; Whitmarsh, Steentjes, Poortinga et al. Reference Whitmarsh, Steentjes, Poortinga, Beaver, Gray, Skinner and Thompson2021, p. 2). The most recent ‘Independent Review of Net Zero’, commissioned by the UK government and chaired by former Energy Minister Chris Skidmore, assesses that almost half of the actions in the Government’s Net Zero Strategy require households to drastically reduce carbon emissions (Skidmore Reference Skidmore2023, p. 216). Likewise, a report by the UK Committee on Climate Change – the independent advisory body to the UK government – estimated that 62% of nationwide emissions cuts needed to reach net zero by 2050 will depend on the extent to which people will change their carbon-dependent lifestyles (Committee on Climate Change 2019, p. 155). In other words, on top of the phase-out of fossil fuel-based forms of energy generation, ‘lifestyle change and individual contributions are inevitable to reduce emissions; especially in high-carbon areas such as diet and agriculture, transport, heating and cooling, and material consumption’ (Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick et al. Reference Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick, Whitmarsh and Poortinga2023, p. 101).

Certainly, as high-emitting people are disproportionately responsible for causing climate change, changing their consumption patterns provides high-leverage opportunities for reducing carbon emissions (Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh Reference Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh2025; Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig et al. Reference Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig, Dietz and Stern2021, p. 1015). Household-level carbon emissions are strongly related to socioeconomic status (SES) (eg Beiser-McGrath and Busemeyer Reference Beiser-McGrath and Busemeyer2024; Minx, Baiocchi, Wiedmann et al. Reference Minx, Baiocchi, Wiedmann, Barrett, Creutzig, Feng, Förster, Pichler, Weisz and Hubacek2013; Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig et al. Reference Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig, Dietz and Stern2021; Pottier Reference Pottier2022) and hence cluster towards more affluent neighbourhoods in geographical terms (Cass, Lucas, Adeel et al. Reference Cass, Lucas, Adeel, Anable, Buchs, Lovelace, Morgan and Mullen2022, p. 18). The statistical link originates mainly from stark consumption inequalities in relation to air travel, motor vehicle use, as well as larger homes and/or multiple residences that need more energy to heat and run (Cass, Lucas, Adeel et al. Reference Cass, Lucas, Adeel, Anable, Buchs, Lovelace, Morgan and Mullen2022; Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig et al. Reference Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig, Dietz and Stern2021).

However, average household-level income increases do not translate in proportion into consumption-based carbon emissions in industrialised democracies (Lévay, Vanhille, Goedemé et al. Reference Lévay, Vanhille, Goedemé and Verbist2021; Pottier Reference Pottier2022). Affluent households are more likely to have the resources needed to decarbonise, for example, by purchasing heat pumps, solar panels, or electric vehicles, and some may pursue these options out of pro-environmental considerations (Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh Reference Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh2025, pp. 8–9). Thus, while it is a truism that the most carbon-emitting households are universally high-SES, there is still considerable variation in carbon emissions in the group of affluent households. In other words, affluence and consumption-based carbon footprints are by no means observable equivalents, and there are other notable correlates of consumption-based carbon emissions (Ivanova, Vita, Steen-Olsen et al. Reference Ivanova, Vita, Steen-Olsen, Stadler, Melo, Wood and Hertwich2017; Salo, Savolainen, Karhinen et al. Reference Salo, Savolainen, Karhinen and Nissinen2021). Sociodemographic and attitudinal factors, such as location (eg urban vs. rural) (Ivanova, Vita, Steen-Olsen et al. Reference Ivanova, Vita, Steen-Olsen, Stadler, Melo, Wood and Hertwich2017; Salo, Savolainen, Karhinen et al. Reference Salo, Savolainen, Karhinen and Nissinen2021), political conservatism (Dietz, Leshko and McCright Reference Dietz, Leshko and McCright2013; Gromet, Kunreuther and Larrick Reference Gromet, Kunreuther and Larrick2013), and levels of climate concern and pro-environmental behaviour (Leferink, Heinonen, Ala-Mantila et al. Reference Leferink, Heinonen, Ala-Mantila and Árnadóttir2023), influence the carbon-dependence of lifestyles and voluntary uptake of low-carbon alternatives and – by extension – are also likely reflected in geographic patterns of consumption-based carbon footprints.

Right-wing political views are particularly important to consider here as these curb pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours and thus increase – all else being equal – consumption-based carbon emissions. In the US, for example, political conservatives have been shown to be less likely to purchase more expensive energy-efficient products when labelled with pro-environmental messages (Gromet, Kunreuther and Larrick Reference Gromet, Kunreuther and Larrick2013). Moreover, across Western European and anglophone countries, partisan polarisation in relation to climate-related attitudes, such as climate change belief, concern, and policy support, has been rising over the past decades (Caldwell, Cohen and Vivyan Reference Caldwell, Cohen and Vivyan2025; McCright, Dunlap and Marquart-Pyatt Reference McCright, Dunlap and Marquart-Pyatt2016a; McCright, Marquart-Pyatt, Shwom et al. 2016Reference McCright, Marquart-Pyatt, Shwom, Brechin and Allenb). Conservative party-family voters were found to be less concerned about climate change than voters on the left, even when accounting for SES and other political values (Fisher, Kenny, Poortinga et al. Reference Fisher, Kenny, Poortinga, Böhm and Steg2022). Additionally, the literature on environmental party politics suggests that the type of state-led interventions required for profound transformations towards a low-carbon economy challenge core conservative values of social system preservation, private property rights and individual freedoms as antipodes to government intervention (Båtstrand Reference Båtstrand2015; Farstad Reference Farstad2018; Fielding, Head, Laffan et al. Reference Fielding, Head, Laffan, Western and Hoegh-Guldberg2012; Ladrech and Little Reference Ladrech and Little2019). Conversely, these interventions resonate better with the ideological profiles of left parties whose voters tend to expect interventionist policies from their political representatives (Schulze Reference Schulze2021, p. 47).

These divides, we argue, matter also for the political relevance of consumption-based carbon footprints. High-emitting individuals in the UK associate low-carbon lifestyles with sacrifice and reduction but excess consumption with status and well-being (Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh Reference Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh2025, p. 18) and especially those climate policies that restrict individual choices and lifestyles are least welcomed by Conservative voters (Whitmarsh, Steentjes, Poortinga et al. Reference Whitmarsh, Steentjes, Poortinga, Beaver, Gray, Skinner and Thompson2021, p. 4). Thus, political conservatism in combination with high SES is likely a key detriment for a transition to a low-carbon lifestyle, reflected in particularly high carbon footprints. At present, this consumer type also has few economic incentives to decarbonise. In the absence of a proactive approach towards curbing consumption-based carbon emissions, affluent households can still afford the status quo of excess carbon consumption. To quote the Skidmore review, for ‘many people, the long payback period means that even if they do break even or save by 2050, going ahead with changes to decarbonise their home and transport won’t feel worthwhile’ (Skidmore Reference Skidmore2023, p. 222).

Thus, while decarbonisation experts agree that net zero policy interventions would be required that ‘disrupt people’s day-to-day lives’ with ‘drastic changes to their lifestyle and norms’ (Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick et al. Reference Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick, Whitmarsh and Poortinga2023, p. 101), their political feasibility remain an open question.

MPs’ representation of constituents’ consumption-based carbon footprints

Against this backdrop, we argue that local concentrations of high-emitting individuals shape the incentives according to which MPs consider their own engagement in parliamentary decarbonisation politics. As canonical studies in the US and UK have established, MPs have a distinct ‘geographical, space-and-place perception of their constituency’ and comprehend ‘‘their districts’ internal makeup using political science’s most familiar demographic and political variables’, including socioeconomic structure, residential patterns, rurality, and partisanship (Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1979, pp. 520–521; Fenno Reference Fenno1977, pp. 884–885). In fact, UK MPs’ constituency rootedness due to local residency, family roots, and political experience has been particularly notable since 2010 (Cowley, Gandy and Foster Reference Cowley, Gandy and Foster2024) – a factor well-known to make MPs internalise the sociodemographic, cultural, and ideological composition of their constituencies with measurable effects on parliamentary activities (Hanretty, Lauderdale and Vivyan Reference Hanretty, Lauderdale and Vivyan2017, p. 240; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999, p. 629; Tavits Reference Tavits2010). Based on this strand of literature, we thus contend that, even if MPs do not have detailed knowledge of local consumption-based carbon emissions data, they can reliably draw on their localised knowledge as a heuristic to acquire an awareness of the carbon dependency of their constituents’ lifestyles and willingness to decarbonise.

Commonly discussed consumption-focused decarbonisation policies, such as carbon taxation, bear heavily on low-income households but hardly affect the excess carbon consumption of affluent households who can afford to continue polluting (Büchs, Bardsley and Duwe Reference Büchs, Bardsley and Duwe2011; Otto, Kim, Dubrovsky et al. Reference Otto, Kim, Dubrovsky and Lucht2019). For some time now, advocates of equitable climate action have lamented the absence of serious policy proposals targeting high-emitting excess consumption, such as frequent flyer levies, progressive energy pricing, or net zero obligations for houses and apartments above a certain size (Otto, Kim, Dubrovsky et al. Reference Otto, Kim, Dubrovsky and Lucht2019). In the words of Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh (Reference Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh2025, p. 2): ‘excess consumption of energy, aviation, food, transport fuels, and other resources by high emitters remains largely untouched by climate policy across OECD countries, including the UK’.

A symptom of this observation might be that MPs representing concentrations of high-emitting constituents eschew debates on consumption-focused decarbonisation rather than drawing attention to forsaking their constituents the amenities of a carbon-intense lifestyle. We know from the literature on social class representation that high-SES voters enjoy particularly high levels of elite attention compared to low-SES voters (eg Lupu and Warner Reference Lupu and Warner2022; Persson and Sundell, Reference Persson and Sundell2024). Given that high-emitting households are ubiquitously high-SESFootnote 1 and tend to be politically conservative and less environmentally minded, MPs representing these constituents may therefore have an electoral incentive to eschew the responsibility to make decarbonisation a priority of their parliamentary work.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Higher consumption-based carbon footprints at the constituency level decrease MPs’ prioritisation of decarbonisation

Furthermore, based on our discussion of the role of political conservatism in relation to consumer behaviour, we expect that the local carbon footprint effect on parliamentary behaviour will not be uniform for Labour and Conservative MPs. In the 2010s, the Labour and the Conservative Parties were the two main competitors for English parliamentary seats, and as they won by far the most constituency races, they are the focus of this study.

However, during our observation period (2011–2018), which is determined by the availability of local-level consumption-based emission data (see data section), the Conservative Party were continuously in government and the Labour Party in opposition. As Farstad (Reference Farstad2018, 701) dubs it, opposition parties are normally ‘[e]ager to find ways of attacking the government (…,) can more easily criticise the status quo and also do not have to stand to account for the current levels of [climate] ambition’. Indeed, Hopper and Swift show for the US that state-level Democratic legislators are more vocal on ambitious climate policies when the state government is Republican-led (Hopper and Swift Reference Hopper and Swift2022). Thus, in contrast to the Conservatives in government, Labour MPs in opposition could be generally less concerned about the possibility of an electoral backlash and thus relatively less sensitive to high consumption-based carbon footprints in their constituencies.

As the government-opposition and party ideology rationales are equally plausible and potentially co-existing causal explanations for an intervening party effect, we are faced with an observational equivalence problem to neatly disentangle these mechanisms. Whilst our mixed-methods research design allows us to examine the relevance of party differences across MPs quantitatively, qualitative interviews provide additional insights into the motivational aspects driving these differences. As the mechanisms could in fact co-exist, we thus formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The negative impact of consumption-based carbon footprints on MPs’ prioritisation of decarbonisation is stronger for Conservative than for Labour MPs.

Presuming that re-election considerations drive MPs’ responsiveness to the carbon-related consumption habits of their constituents, one would also expect that this responsiveness intensifies as MPs’ parliamentary seats become more electorally vulnerable. Studies on the effect of electoral vulnerability on parliamentary behaviour suggest that marginal seats heighten MPs’ constituency service (André, Depauw and Martin Reference André, Depauw and Martin2015; Fernandes, Geese and Schwemmer Reference Fernandes, Geese and Schwemmer2019; Kellermann Reference Kellermann2016). Similarly, political economy scholars argue that electoral safety is a key condition for politicians to adopt unpopular long-term policy investments (also specifically in relation to climate change mitigation) by insulating them against decreases in vote shares (Finnegan Reference Finnegan2022, p. 1206; Jacobs Reference Jacobs2016).

Arguably, MPs who succeeded in the previous constituency race by a large vote margin might not be as concerned about electoral backlashes as MPs who prevailed due to smaller winning margins. Thus, as another conditional hypothesis, we expect that the link between the consumption-based carbon footprint of the constituency and MPs’ decarbonisation-related parliamentary behaviour hinges on the marginality of their seats.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): The negative impact of consumption-based carbon footprints on MPs’ prioritisation of decarbonisation grows stronger as parliamentary seats become more electorally vulnerable.

Data and methods

In this section, we outline the mixed-methods research strategy to examine the hypotheses laid out in the previous section. We begin by discussing case selection before moving on to showcase our quantitative data and analysis approach. Finally, we outline how we use qualitative in-depth interviews with sitting and retired Westminster MPs to supplement the quantitative analysis.

Case selection: Why study the UK?

The UK is a prototype of a majoritarian FPTP system (Farrell Reference Farrell2011; Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012). MPs are elected in 650 single-member constituencies according to a simple plurality rule, which is widely acknowledged to have crucial consequences for the representational link between citizens and their parliamentary representatives (eg Hanretty, Lauderdale and Vivyan Reference Hanretty, Lauderdale and Vivyan2017; Mitchell Reference Mitchell, Gallagher and Mitchell2005). Other major democracies, most notably the US, Canada and India, use FPTP as well, rendering it the most widely used electoral system across the globe in population terms (Farrell Reference Farrell2011, p. 13). These four countries alone were responsible for 22% of global carbon emissions in 2021 (European Commission 2022), which justifies the need to examine more closely the politics shaping decarbonisation politics under FPTP from a global carbon emissions perspective.

Furthermore, the common view of the UK as an international ‘climate leader’ compared to the other mentioned prominent carbon-emitting countries using FPTP renders the country a least-likely case (Seawright and Gerring Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) for the purpose of our study. The ‘groundbreaking’ 2008 Climate Change Act (CCA) passed by an overwhelming cross-party majority made the UK the first country to enshrine emission reductions into law (Carter Reference Carter2014, p. 423) and it was also among the first to amend this law to include a ‘net zero’ goal by 2050 in the aftermath of the 2015 Paris agreement (Höhne, Gidden, den Elzen et al. Reference Höhne, Gidden, den Elzen, Hans, Fyson, Geiges and Rogelj2021). This places the UK formally as a world leader on climate action with a commitment to climate action across both main parties (Dudley, Jordan and Lorenzoni Reference Dudley, Jordan and Lorenzoni2022; Rayner and Jordan Reference Rayner and Jordan2016). If the electoral geography of carbon-related consumption habits works as a constraining factor on parliamentary decarbonisation politics in the UK, similar dynamics are likely to matter even more in countries where climate change mitigation is indeed less of a national policy priority.

Therefore, insights into how Westminster MPs respond to the carbon intensity of their constituents’ consumption habits will likely have implications applicable to a broader class of democratic systems.

The dependent variable: English MPs’ decarbonisation-related parliamentary speechmaking

As indicators of decarbonisation-related parliamentary behaviour, we study MPs’ oral contributions to parliamentary debates in the UK House of Commons, 2011–2018. Parliamentary debates are central to the process of political representation and public policymaking. Given that any ‘controversial topic being considered for serious policy action must have some debate in the chamber’ (Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005, p. 39), parliamentary debates offer MPs the opportunity to give voice to constituency interests in the policymaking process (Fernandes, Debus and Bäck Reference Fernandes, Debus and Bäck2021). From an analytical viewpoint, parliamentary debates also offer key analytical advantages compared to legislative votes, which – in the UK in particular – are characterised by high levels of party discipline and relatively rare ‘backbench rebellions’ (Cowley Reference Cowley2002; Slapin, Kirkland, Lazzaro et al. Reference Slapin, Kirkland, Lazzaro, Leslie and O’Grady2018). Through speechmaking in parliament, individual MPs are able to voice their own views and/or local concerns without the drawback of having to undermine the party line in legislative voting. Moreover, House of Commons rules of procedure do not provide party leaders formal means of controlling when backbenchers speak or what they say in parliamentary debates, but provide MPs a well-mediatised platform to speak their conscience relatively free of party control (Proksch and Slapin Reference Proksch and Slapin2015). Thus, studying parliamentary debates should provide key insights into MPs’ constituency representation in relation to decarbonisation politics.

We collected the texts of all individual contributions to parliamentary debates of English MPs from 2011 until 2018 from the theyworkforyou API.Footnote 2 The restriction to English MPs follows from the availability of local emissions data (see next subsection). Following existing research practice of parliamentary speech analysis, we include all types of debates, including Question Time and Westminster Hall debates, but we discarded oral contributions consisting of less than 50 words and those provided by the Speaker of the House (Blumenau and Damiani Reference Blumenau and Damiani2021). The resulting text corpus of parliamentary speeches consists of overall 351,115 oral contributions.

As the dependent variable of our quantitative study, we focus on speeches that make unambiguous references to decarbonisation-related policy issues rather than simply looking for references to climate change, carbon emissions, or global warming in the abstract. For this purpose, we utilise the computer-assisted topic discovery algorithm proposed by King, Lam and Roberts (Reference King, Lam and Roberts2017). This method combines supervised document classification with human key-term selection (Grimmer and Stewart Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013) to iteratively narrow down an extensive corpus of text to documents that relate to a pre-defined concept. Particularly in relation to climate policy-relevant text, this approach avoids many of the pitfalls that accrue to the application of from-scratch or off-the-shelf dictionary methods (Geese, Sullivan-Thomsett, Jordan et al. Reference Geese, Sullivan-Thomsett, Jordan, Kenny and Lorenzoni2024). We provide further details in the online Supplementary Material A.

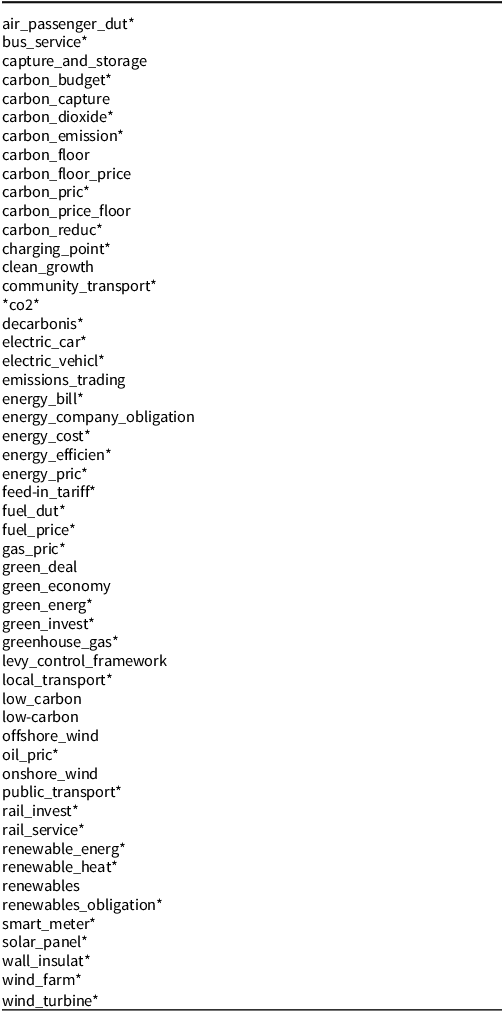

Table 1 provides an overview of the references extracted from the corpus using King et al.’s method to identify decarbonisation-related debate contributions. We focus on fifty-three commonly used references relevant to the issue of decarbonisation and paid particular attention to measures that affect people’s lifestyles and costs (eg fuel duty, smart metres, air passenger duties) as well as aspects of the green transition that ultimately influence consumers (eg onshore wind, carbon capture, emissions trading). Although the latter types of regulations might be viewed as addressing mainly producers of energy and other carbon-dependent goods, associated investments typically require substantial upfront costs that tend to be ultimately passed to consumers (De Almeida and Esposito Reference De Almeida and Esposito2024, p. 413; Poynting and Reuben Reference Poynting and Reuben2025). Moreover, in this ‘core’ list of decarbonisation-related key terms, we ignore more abstract references to climate change, fossil fuels, or transport.

Table 1. Final list of decarbonisation-related key terms extracted from the corpus using King et al.’s semi-supervised topic discovery algorithm (Reference King, Lam and Roberts2017)

However, to show that the results of our analysis are not biased by a list of handpicked key terms, we provide extensive replication analyses in the Supplementary Material. This includes an extended list of seventy-eight key terms, inclusive of abstract references to climate change and fossil fuels, as well as a shortened, exclusive list of sixteen key terms relating directly to consumer costs and behaviours (see Supplementary Material A and D for more details).

Out of the 351,115 speeches, we identified 13,652 (3.9 per cent) in which MPs engaged with the issue of decarbonisation. In Supplementary Material A, we provide five random examples of such speeches. Focussing on the speech-level as the unit of analysis, the resulting dependent variable thus distinguishes between decarbonisation-related (=1) and -unrelated (=0) debate contributions.

The main independent variable: Consumption-based carbon footprints at the constituency level

Our independent variables vary at the constituency level. First, we measure the local carbon footprints of all constituencies in England based on data from the Place-based Carbon Calculator project (https://www.carbon.place). This data estimates the annual per-person carbon footprint in kilograms CO2 for every Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) in England between 2011 and 2018 using a wide range of sources from official spatial statistics in combination with existing surveys to quantify consumer behaviour in terms of electricity and gas use, domestic heating, car/van mileage, flights, and the consumption of goods and services (for more information, see Morgan, Anable and Lucas Reference Morgan, Anable and Lucas2021). We aggregated the data at the constituency level using official look-up files from the Office for National Statistics (Office for National Statistics 2011), weighting each LSOA’s per capita footprint by its population share in the constituency.Footnote 3

Based on this, Figure 1 visualises the electoral geography of these consumption-based carbon footprints in England. At the constituency level, average annual per-capita emissions ranged from 4,544 to 12,743 kg CO2 between 2011 and 2018 in the 533 English constituencies. The three top-emitting constituencies were Henley, North East Hampshire, and Wimbledon, all of which were Conservative-led constituencies. The three least-emitting constituencies, Manchester Gorton, Manchester Central, and Birmingham Hodge Hill, were all Labour-led constituencies. This party divide can also be observed in the right-hand histogram of Figure 1: Conservative constituencies tend to have higher average consumption-based carbon footprints than Labour constituencies (8,810 vs 7,116 kg CO2 per annum), which is in line with our theoretical argumentation that local preferences for political conservatism are reflected in larger consumption-based carbon footprints. Furthermore, the data also reflects the SES-correlation of consumption-based carbon footprints, as can be seen in the bottom-right plot of Figure 1, which illustrates that high-emitting constituencies are systematically less affected by unemployment than low-emitting ones.

Figure 1. Average consumption-based carbon footprints in English Westminster constituencies 2011–2018.

Other explanatory and control variables

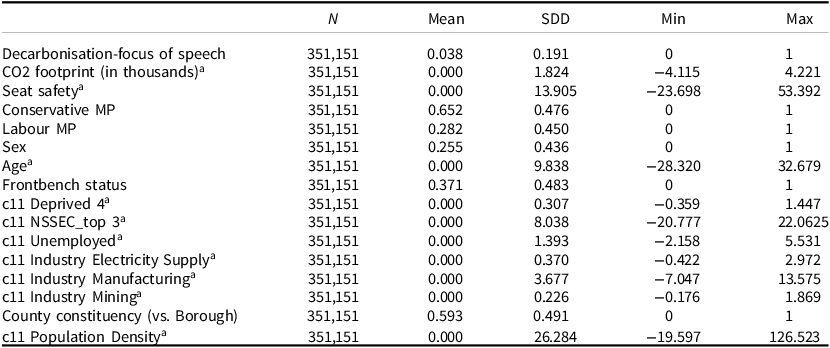

We extend our dataset further with MP-level and constituency-level variables, for which Table 2 provides basic descriptives. We coded MPs’ party affiliation, sex, age, frontbench Footnote 4 status, and the official IDs of their constituencies from publicly available sourcesFootnote 5 . We measure seat safety based on the margin of an MP’s electoral victory over the second-placed candidate in the most recent general election.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Note: a mean-centred.

We also control for alternative constituency-level variation based on Census 2011 data, which we sourced from the British Election Study (Fieldhouse, Green, Evans et al. Reference Fieldhouse, Green, Evans, Mellon and Prosser2022). This includes the unemployment rate shown in Figure 1 as well as alternative measures indicative of SES and the broader non-consumer carbon intensity of the district. As alternative measures of SES, we consider the percentage of households considered deprived on 4 dimensions (employment, education, health, and housing) by the Office of National Statistics, as well as the percentage of the workforce in the top 3 (out of 10) occupation categories of the National Statistics Socioeconomic Classification (NS-SeC). To assess the relevance of heavy industry and fossil fuel production in the constituency, we further consider three variables that indicate the percentage of the local workforce employed in manufacturing industries, in the electricity supply sector and in mining industries, which includes coal, oil, and gas extraction. And to capture urban-rural differences, we incorporate population density and the distinction between county and borough constituencies.

In Figure C1 of Supplementary Material C, we provide additional scatterplots showing the covariation of these constituency-level factors with consumption-based carbon footprints. These reiterate the strong, albeit imperfect, correlations of carbon footprints with SES-related indicators. Furthermore, the plots indicate that there is considerable variation in carbon footprints within the group of high-SES constituencies. For example, constituencies with more than 40% of the workforce employed in the top 3 NS-SeC categories range between 7,000 and 13,000 kg consumption-based CO2 footprints. However, at the end of ultra-high emitting constituencies above 11,000 kg, the plots show that these constituencies are much more homogenous, for example, in terms of consistent low levels of unemployment, deprivation, population density or workforce employed in manufacturing. As panel (b) of Figure 1 shows, these constituencies are also overwhelmingly conservative seats.

Finally, we control for each legislative term 2010–15, 2015–17, and 2017–19 in the estimation because the government constellation differed slightly between those: from 2010 until 2015, the Conservatives were in a coalition with the Liberal Democrats; from 2015 until 2017, the Conservatives had an absolute parliamentary majority; and from 2017 until 2019, they formed a minority government supported by the Northern Irish DUP.

Statistical model

Our quantitative data collection constitutes a nested data structure that needs to be accommodated in the data analysis. We consider observations to be nested within constituencies per legislative term. Given that the dependent variable distinguishes between decarbonisation-focused (=1) and other debate contributions (=0), we estimate multilevel logistic regression models in which random intercepts vary at the constituency level. This allows us to capture unobserved local heterogeneity in addition to those characteristics explicitly modelled through control variables. Furthermore, we model observations as nested within three legislative terms by including dummy covariates for each term. Our baseline model specification is hence the following:

$$\log \left[ {{{{p_{ij}}}}\over{{1 - {p_{ij}}}}} \right] = {\rm{\;}}{\beta _{00}} + {\beta _{01}}{\rm{CO}}{2_j} + {\beta _{02}}Ter{m_j} + {\beta _{0i}}{x_j} + {\mu _{0j}} + {\varepsilon _{ij}}$$

$$\log \left[ {{{{p_{ij}}}}\over{{1 - {p_{ij}}}}} \right] = {\rm{\;}}{\beta _{00}} + {\beta _{01}}{\rm{CO}}{2_j} + {\beta _{02}}Ter{m_j} + {\beta _{0i}}{x_j} + {\mu _{0j}} + {\varepsilon _{ij}}$$

Here,

![]() ${p_{ij}}$

is the likelihood of a speech i of MP j being decarbonisation-focused.

${p_{ij}}$

is the likelihood of a speech i of MP j being decarbonisation-focused.

![]() ${\rm{CO}}{2_j}$

is the constituency-level explanatory variable measuring local carbon footprints.

${\rm{CO}}{2_j}$

is the constituency-level explanatory variable measuring local carbon footprints.

![]() $Ter{m_j}$

is the dummy control variable for the three analysed legislative terms.

$Ter{m_j}$

is the dummy control variable for the three analysed legislative terms.

![]() ${x_j}$

represents other MP and constituency-level explanatory and control variables. The fixed intercept component

${x_j}$

represents other MP and constituency-level explanatory and control variables. The fixed intercept component

![]() ${\beta _{00}}$

and the slopes

${\beta _{00}}$

and the slopes

![]() ${\beta _{01}}$

and

${\beta _{01}}$

and

![]() ${\beta _{02}}$

are the parameters to be estimated. The error term

${\beta _{02}}$

are the parameters to be estimated. The error term

![]() ${\mu _{0j}}$

represents varying intercepts at the constituency level.

${\mu _{0j}}$

represents varying intercepts at the constituency level.

![]() ${\varepsilon _{ij}}$

is the speech-level error term. In addition, we grand mean-centred all continuous variables varying at the MP/constituency-level (Enders and Tofighi Reference Enders and Tofighi2007).

${\varepsilon _{ij}}$

is the speech-level error term. In addition, we grand mean-centred all continuous variables varying at the MP/constituency-level (Enders and Tofighi Reference Enders and Tofighi2007).

Qualitative in-depth interviews

We supplement the quantitative analysis with qualitative interviews conducted with twentyFootnote 6 sitting or retired Labour and Conservative MPs from England. The interviews took place in-person or online between October 2023 and February 2024.Footnote 7 Participants were targeted based on their public record of climate change engagement as indicated in parliamentary questions, speeches and media appearances, and recruited via personalised email invitations.Footnote 8 Importantly for our research interest, the twenty interviewed MPs provide a good spread across constituencies’ consumption-based carbon footprints: five MPs are from constituencies with a lower carbon footprint profile (below 6,500 kg CO2), ten from constituencies with a medium carbon footprint (between 6,500 and 9,000 kg CO2) and five from high-emitting constituencies (over 9,000 kg CO2). The interview design was semi-structured and had a specific climate change angle. Topics covered included how MPs conceptualised their relationship with voters, how important they considered political leadership and their own parliamentary work for tackling climate change, and what responsibility they attribute to members of the public for climate action. The average interview length was 33 minutes.

Findings

In this section, we present the empirical evidence from our mixed-methods research design. In the first subsection ‘Charting the link between constituencies’ carbon footprints and politicians’ decarbonisation-related behaviour’, we bring together the evidence from the quantitative speech analysis and qualitative interviews to examine the relationship between constituencies’ carbon footprints and politicians’ decarbonisation-related behaviour. Thereafter, in subsections ‘The role of party differences’ and ‘The role of electoral considerations’, we consider the moderating impacts of MPs’ party affiliations and electoral considerations respectively.

Charting the link between constituencies’ carbon footprints and politicians’ decarbonisation-related behaviour

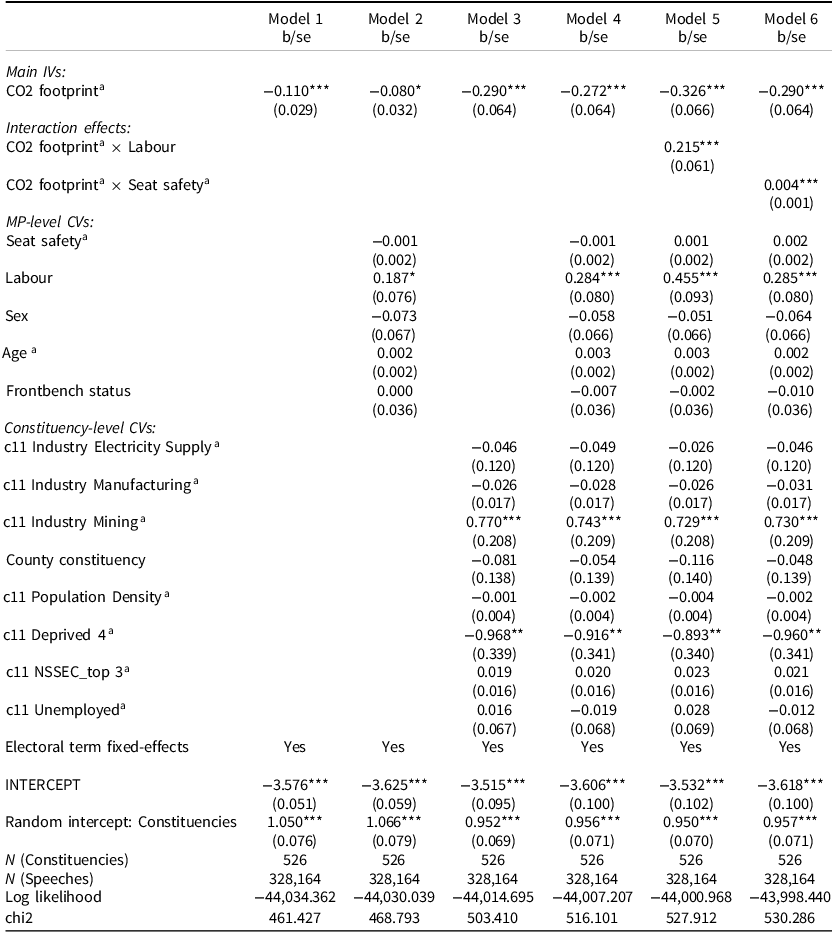

Table 3 presents the results of a series of multilevel logit models regressing the likelihood of making a decarbonisation-focused speech on constituency-level and MP-level characteristics. We restrict the analysis to observations of speeches given by Labour or Conservative MPs, the two largest parties in parliament.Footnote 9

Table 3. Multi-level logistic regression models explaining decarbonisation-related speechmaking

Note: Multi-level logit regression mixed effects estimates; standard errors reported in parentheses; amean-centred; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Model 1 presents a simple model that considers only the baseline specifications (random-intercepts at the constituency level and electoral term fixed-effects) and the main independent variable, ie the local carbon footprint. Models 2, 3, and 4 extend this model by different sets of control variables: Models 2 and 3 add MP-level and constituency-level variation respectively; Model 4 adds all those controls simultaneously. Importantly, in all these models, the consumption-based local carbon footprint is found to have a negative and statistically significant effect on the likelihood of an MP engaging with decarbonisation issues in parliamentary speech. The left-hand plot of Figure 2 visualises this effect as a predicted probabilities plot. At the lower end of the emissions spectrum, the likelihood of a decarbonisation-related speech is estimated to amount to almost 0.10, while it is only at 0.01 at the upper end.

Figure 2. The effect of local CO2 footprints on decarbonisation-related speechmaking.

Note: left-hand plot based on Model 4 and right-hand plot based on Model 5 in Table 3.

While this lends empirical support for our first hypothesis, the qualitative interview material helps to contextualise these findings. A key assumption underlying our theoretical rationale is that MPs draw on their comprehension of the local socio-structural composition to acquire an awareness of local lifestyles and the decarbonisation sentiment of their constituencies that are also reflected in consumption-based carbon footprints. In our interviews, MPs commonly admitted that they are constrained in terms of how they understand and are able to represent the opinions of all of their constituency, eg

… you can’t do an opinion survey of the whole of your constituency and say, “Is this something you think we should be doing?” (Int62),

… notwithstanding the fact that probably 99.9% of my constituents have never expressed an opinion to me on anything, I represent them too (Int45).

Yet, they often indicated that they could gather and comprehend this from the sociodemographic and political makeup of their constituencies:

… this area, the community that I represent, to be fair or to be frank, is very different to, say, Brighton, which Caroline Lucas represents (Int38).

My constituency is not like another constituency in my region which has more Green than Labour councillors […] you’ll get people that will be cycling around, and going to buy their organic this, that and the other, but a lot of them won’t be (Int49).

Thus, although we did not directly ask MPs about their perceptions of local consumption-based carbon footprints, statements like these back our confidence in the fact that MPs infer local lifestyles and decarbonisation stances from their knowledge of socioeconomic and political factors, which are also reflected in local carbon footprints.

The role of party differences

Party differences are a key element in our theoretical argumentation underlying the link between local carbon footprints and parliamentary speechmaking. In our quantitative analysis, the two-way interaction between CO2 footprint and party membership (Model 5) generates a statistically significant interaction term, suggesting that Labour MPs respond considerably differently to local carbon footprints than Conservatives do. With Labour MPs representing on average lower-emitting constituencies (see Figure 1B), the negative association between local CO2 footprint and speechmaking is less stark than for Conservative MPs. The right-hand plot of Figure 2 provides a visualisation of this. As hypothesised, the negative relationship between CO2 footprint and speechmaking is mainly driven by Conservative MPs but much attenuated for Labour MPs. Although the slope is also negative for Labour MPs, it is a much gentler slope with estimated confidence intervals being rather large and overlapping across different values of the local CO2 footprint.

Our qualitative interviews provide further nuance to this moderating effect of party affiliation. On the surface, many of Conservative and Labour interviewees acknowledged that ordinary members of the public have a role in making choices to reduce their CO2 emissions:

We need members of the public to do things to reduce their own carbon footprints and encourage their friends and family and neighbours to do the same (Int58).

Yet MPs across the aisle also highlighted the challenge of advocating for low-carbon lifestyle changes politically, frequently mentioning the burden of short-term transformational costs. A Conservative MP, for example, aired the view that ‘Today’s living standards are important too as well as tomorrow’s climate’ (Int52). Labour interviewees highlighted similar perceptions, remarking that people generally think it is a good idea to tackle climate change ‘as long as it doesn’t affect their lifestyle too much’ (Int50).

However, below the surface of more generic statements, the interview material also provides evidence of deep-rooted party ideological convictions concerning the role of consumer choice and state-led interventions that, in particular, set apart Conservative MPs representing high-emitting constituencies from other Conservative MPs and, most strongly, from Labour interviewees. More generally, Conservative MPs, regardless of their constituency’s carbon footprint, shared the view that decarbonisation

… needs to be driven by markets and commercial decisions and consumer choice. […] [L]et the market decide where the opportunities are rather than have a government saying, “It’s X and we’re going for X and we’re going to make a law to make sure you go for X” (Int45).

Conservative MPs representing high-emitting constituencies were markedly outspoken against the idea of state-led lifestyle interventions. These MPs commonly highlighted the idea that the market will deliver necessary new technologies that people would eventually independently support by ‘making hard-nosed commercial decisions to invest in this technology’ as one of the five interviewed Conservative MPs representing high-emitting constituencies put it (Int65).

A second Conservative MP from a high-emitting seat contrasted getting people to adopt climate mitigation technologies with that of digital technologies like Netflix:

[People who want] Apple devices, they go out and pay their own good money for them and they don’t need subsidies, they don’t need tax, they don’t need regulation, they don’t need laws. They do it because they are offering enhancements to their lives that they really value (Int59).

The same MP also contended that constituents should be allowed to do ‘nice’, carbon-intensive things like flying abroad for holidays or having petrol or diesel cars, and was aggrieved at the prospect of a politician who would ‘go around lecturing all my constituents that they have got to find a pile of money to buy an electric car and a heat pump’ (Int59). And a third Conservative interviewee from a high-emitting constituency contended:

People won’t do, in a complex democracy, anything that reduces the quality of their lifestyle. […] you can’t punish a population with decarbonisation (Int47).

To the contrary, although none of our Labour interviewees represented high-emitting seats, even Labour MPs representing medium-emitting constituencies in our sample were much more likely than Conservative MPs to challenge the ‘classic anti-regulation Conservative way’ (Int56). As another Labour interviewee lamented:

[T]here is a real tendency on the part of this [Conservative] government to push everything to consumers. […] And so, I’m always a little bit wary of – I think it’s almost like letting the government off the hook a bit […] and it’s an ideological thing. It’s always framed as educating people, telling people, rather than imposing it on them (Int49).

Our theoretical discussion also highlighted different electoral considerations between MPs from governing (Conservatives) and opposition (Labour) parties as an alternative plausible explanation in relation to state-led lifestyle interventions. The interview material evidences that the government-opposition status complements rather than replaces the relevance of deep-rooted ideological differences between these parties. Compared to their Conservative peers on the government benches, MPs from the Labour Party talked about the influence of electoral factors in far more party-political terms, cynically referring to the Conservative government’s climate policy decisions as being mainly related to its re-election prospects. For example, Labour interviewees opined that the electoral cycle leads to ‘cheap politics’ like Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s delay of the ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2030 to 2035 (Int49), which another interviewee saw as an attempt to reduce the government’s unpopularity at the time (Int58). In contrast, Conservative MPs framed electoral factors less in a party-political sense but in a more pragmatic sense around the general limitations of the electoral and parliamentary system. Conservative MPs stated, for example, that the pace of change that the party and/or government takes in tackling climate change should only go ‘as fast and thoroughly as your voters allow’ (Int64) or that…

You would be a foolish politician if you didn’t do what your constituents ask you to […]. Sometimes I should be advocating and trying to persuade people what is right even if a significant minority – or indeed a majority – disagree with me. They will have their chance to question my judgement at the next election (Int45).

The role of electoral considerations

Turning back to Table 3, Model 6 extends Model 4 by the two-way interactions between CO2 footprint and seat safety. Figure 3 visualises the interactive effect between the local carbon footprint and MPs’ seat safety for different values of seat safety: when the vote margin is slim at only 1%, when it is average (21%) and when it is at a comfortable winning margin (37%). As these plots suggest, the strength of the negative association between decarbonisation-related speechmaking and the CO2 footprint attenuates as the safety of the parliamentary seat increases. This corroborates H3.

Figure 3. The interactive effect of CO2 footprint and seat safety.

Note: based on Model 6 in Table 3.

The relevance of MPs’ electoral considerations for the negative relationship between the local CO2 footprint and parliamentary speechmaking is further buttressed by our qualitative interview evidence. Indeed, re-election prospects were frequently mentioned by MPs and – as the last interview quotes in the previous section exemplified – especially Conservatives as a factor that would affect the extent to which they act of their own volition as opposed to following the opinion of (a majority of) their constituents.

Sometimes, these voter/electoral narratives were pitched in relation to MPs’ seat marginality and its relevance for their felt insulation from a potential electoral backlash. As one MP from a high-emitting constituency put it:

I was fortunate, I had a substantial majority and therefore if people said, “I can’t ever vote for you again,” well, it wasn’t going to be the end of the world. So, I was able to toughen it out. I’d previously had a marginal seat, and then that’s very different, because you know that every single vote is the one which could determine whether you win or lose. But you have got that greater comfort when you’ve got a large majority, because you can say, “Look, this is what I think. This is the right thing to do and I intend to pursue that course” (Int41).

Robustness checks

In Supplementary Material C and D, we provide several alternative model specifications to assess the robustness of our quantitative findings.

In Supplementary Material C Table C1, we provide additional regression models that control for only one of the constituency-level control variables at a time to address concerns of multicollinearity and overfitting.

In Supplementary Material D, we re-estimated the models shown in Table 3 in different samples and based on alternative operationalisation of the dependent variable as additional robustness checks of our findings. As a first robustness check, we re-estimate models in the whole sample of all English MPs, ie inclusive of those from smaller parties, results of which are shown in Table D1. As can be seen, coefficient estimates for CO2 footprint and its respective interactions with seat safety and party affiliation are hardly different. Tables D2–5 then present a series of robustness checks with alternatively specified dependent variables. Table D2 replicates the models with a dependent variable based on the less conservative, extended list of decarbonisation-related key terms extracted via King et al.’s semi-supervised topic discovery workflow (cf. ‘Data and Methods’ section on the dependent variable and Supplementary Material A). By contrast, the replication models shown in Tables D3 and D4 are based on more conservative versions of the original dependent variable: they classify speeches as decarbonisation-specific only if those make at least two (Table D3) or three (Table D4) references to the key terms shown in Table 1. Finally, Table D5 provides replication models for a dependent variable based on the reduced list of key terms referring directly to consumer costs and behaviours. Yet, none of these alternative specifications would lead to substantially different model estimations and hence conclusions. Moreover, the robustness of our analysis is corroborated in that the quantitative and qualitative side of the analysis provide complementary results.

Conclusion

A growing number of high-income liberal democracies, like the UK, have pledged to reach net zero carbon emissions by, or even before, mid-century (Höhne, Gidden, den Elzen et al. Reference Höhne, Gidden, den Elzen, Hans, Fyson, Geiges and Rogelj2021). While reaching these targets would constitute important contributions to keep global warming at ‘safe levels’, their political feasibility remains uncertain given that the carbon-dependent lifestyles of consumers and (hence) voters need to change considerably in the near-time to enable large-scale emission cuts (Skidmore Reference Skidmore2023; Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick et al. Reference Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick, Whitmarsh and Poortinga2023). As the link between carbon emissions and everyday consumption behaviour is not necessarily self-evident, calls have been made for politicians to intensify their political leadership on the issue (Boasson and Tatham Reference Boasson and Tatham2023; Jordan, Lorenzoni, Tosun et al. Reference Jordan, Lorenzoni, Tosun, i Saus, Geese, Kenny and Schaub2022; Willis Reference Willis2018). As Whitmarsh, Steentjes, Poortinga et al. put it, there is ‘a need for further communication with the public to raise awareness of the societal transformation needed for net zero and of the costs of inaction to avoid backlash’ (Reference Whitmarsh, Steentjes, Poortinga, Beaver, Gray, Skinner and Thompson2021, p. 6). In particular, members of the public who disproportionally cause carbon emissions would present a high potential for demand-side decarbonisation (Cass, Lucas, Adeel et al. Reference Cass, Lucas, Adeel, Anable, Buchs, Lovelace, Morgan and Mullen2022; Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig et al. Reference Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig, Dietz and Stern2021) and should therefore receive heightened political attention from a climate mitigation and justice perspective (Beiser-McGrath and Busemeyer Reference Beiser-McGrath and Busemeyer2024; Dolšak and Prakash Reference Dolšak and Prakash2022; Harlan, Pellow, Roberts et al. Reference Harlan, Pellow, Roberts, Bell, Holt, Nagel, Dunlap and Brulle2015).

Our study speaks to this debate by providing the first assessment of how voters’ carbon-dependent consumption habits relate to their parliamentary representatives’ engagement with issues of decarbonisation. Theoretically, we have argued that imposing the required near-term transformational costs on high-emitting constituencies confronts parliamentary representatives with a dilemma: while their constituencies could make crucial contributions to nationwide emission cuts, their electoral calculus is often stacked against making this a focus of their parliamentary work and communication. Therefore, our argument posits that the carbon-intensity of constituents’ lifestyles dampens politicians’ immediate appetite to engage in decarbonisation politics despite the urgent action required by a changing climate.

This intuition is supported by the evidence revealed by our mixed-methods research design, in which we combined rare consumption-based local emissions data with quantitative speech analysis, and qualitative elite interviews. Our findings suggest that English MPs’ prioritisation of decarbonisation issues between 2011 and 2018 was indeed negatively correlated with local consumption-based carbon footprints. Moreover, Conservative MPs were more responsive to the carbon-dependent lifestyles of their constituents than Labour MPs. Especially in interviews with Conservative MPs representing high-emitting constituencies, there was a notable sense of scepticism towards state-led interventions into peoples’ lifestyles, where instead laissez-faire technological and market-based approaches to consumption-focused decarbonisation were favoured. This partisan divide was further reinforced by both parties’ continuous role as government/opposition parties throughout the observation period. Labour MPs, who were in opposition, framed the issue notably more strongly in a party-political way, accusing the Conservative government of following mainly short-term electoral considerations rather than long-term climate goals. By contrast, Conservative MPs rationalised the challenge of consumer decarbonisation in a more pragmatic sense around the general limitations of the electoral and parliamentary system.

This draws a sobering picture of politicians’ willingness to sacrifice short-term electoral gains for the long-term prospect of net zero and especially for those MPs representing constituencies that could make high-impact contributions to nationwide emission cuts. Our findings hence provide important lessons for a burgeoning body of literature seeking to understand the political prerequisites and barriers for a low-carbon societal transformation so urgently required to avert the worst consequences of a changing climate (Boasson and Tatham Reference Boasson and Tatham2023; Jordan, Lorenzoni, Tosun et al. Reference Jordan, Lorenzoni, Tosun, i Saus, Geese, Kenny and Schaub2022).

First, our study should be of interest to scholars of environmental party politics (eg Båtstrand Reference Båtstrand2015; Farstad Reference Farstad2018; Ladrech and Little Reference Ladrech and Little2019; Schulze Reference Schulze2021; Schwörer Reference Schwörer2024). Our finding of deep-rooted ideological differences moderating the representative relationship between MPs and constituents’ carbon footprints shows the importance of party politics in the challenge of bringing down consumption-based emissions – an aspect of decarbonisation that remains under-researched in the existing party politics literature.

Second, our study also makes several contributions to the accelerating academic debates on the relevance of distributive conflict, socioeconomic inequalities, and justice perceptions in climate politics (eg Aklin and Mildenberger Reference Aklin and Mildenberger2020; Bakaki, Böhmelt and Ward Reference Bakaki, Böhmelt and Ward2022; Dolšak and Prakash Reference Dolšak and Prakash2022; Harlan, Pellow, Roberts et al. Reference Harlan, Pellow, Roberts, Bell, Holt, Nagel, Dunlap and Brulle2015). The climate policy challenge of navigating the trade-off between long-term climate mitigation goals and short-term, geographically targeted benefits/costs has predominantly been studied from the perspective of members of the public (Bolet, Green and González-Eguino Reference Bolet, Green and González-Eguino2024; Colantone, Di Lonardo, Margalit et al. Reference Colantone, Di Lonardo, Margalit and Percoco2024; Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley Reference Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley2022; Stokes Reference Stokes2016), but relatively sparsely from the perspective of elite responsiveness (Anderson, Butler, Harbridge-Yong et al. Reference Anderson, Butler, Harbridge-Yong and Markarian2023; Finseraas, Høyland and Søyland Reference Finseraas, Høyland and Søyland2021; Kono Reference Kono2020). Not only does our study provide new evidence from a politician perspective, but it links the issue of local climate policy vulnerabilities also to that of inequalities in carbon emissions (Beiser-McGrath and Busemeyer Reference Beiser-McGrath and Busemeyer2024; Cass, Lucas, Adeel et al. Reference Cass, Lucas, Adeel, Anable, Buchs, Lovelace, Morgan and Mullen2022; Harlan, Pellow, Roberts et al. Reference Harlan, Pellow, Roberts, Bell, Holt, Nagel, Dunlap and Brulle2015; Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh Reference Moorcroft, Hampton and Whitmarsh2025; Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig et al. Reference Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig, Dietz and Stern2021). That is, we provide evidence that geographical inequalities in carbon emissions are reproduced at the elite level where they constrain political engagement with the issue.

Third, and relatedly, our study helps to nuance recent findings in the political economy literature on climate change in relation to the role of electoral institutions as a factor shaping the distribution of near-time climate policy costs across different stakeholder communities. Finnegan has argued that because ‘PR rules increase electoral safety, they decrease risks associated with shifting costs toward voters’ whereas ‘[f]irst-past-the-post rules decrease electoral safety and thereby increase the political risk of imposing costs on voters’ (Finnegan Reference Finnegan2022, pp. 1210–11). Although this system-level view on electoral vulnerability is certainly a fruitful perspective to understand cross-country differences, our results suggest that within-system differences of electoral vulnerability across constituencies are crucial determinants of individual-level behaviour in climate politics – a point that has previously been made in the more general study of legislative behaviour (Fernandes, Geese and Schwemmer Reference Fernandes, Geese and Schwemmer2019).

In making these contributions, our study raises two pertinent avenues for succeeding research to pursue. The first is to explore the conditions under which high-emitting constituents are willing to accept decisive lifestyle interventions to bring down consumption-based emissions. As Beiser-McGrath and Busemayer (Reference Beiser-McGrath and Busemeyer2024, p. 1303) note ‘the existing income gradient in support for climate policy, with higher support amongst higher incomes, may change as the discussion of climate change and climate inequality focuses on the high absolute emissions of richer individuals’. Recent research has shown that spatially targeted decarbonisation policies can succeed if affected communities receive monetary or other forms of compensation from the government. However, this line of research has focused mainly on how compensatory ‘just transition’ policy packages can shore-up the support of comparatively low-SES coal communities rather than high-SES individuals (Bolet, Green and González-Eguino Reference Bolet, Green and González-Eguino2024; Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley Reference Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley2022). Given that the highest emitting households are ubiquitously high-SES that could afford the required lifestyle changes, there is less of a moral imperative for government policy to compensate transformation costs based on an economic vulnerability argument. Indeed, compensating high-emitting individuals for carbon emission cuts would arguably turn the ‘just transition’ narrative on its head, and possibly spur opposition from less well-off people. Hence, there is a need for more research on how the rapid and deep decarbonisation of consumer behaviour can be made ‘just’ and politically feasible at the same time.

Our second suggestion for succeeding research is directly related to this conundrum but turns the attention back to the political representatives of high-emitting constituencies. The process of political representation is not a static, one-way route, but actually a dynamic interaction between represented and representatives, in which the latter have means to ‘educate’ and shape preferences of the former (eg Disch Reference Disch2011; Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam, Persson, Esaiasson and Narud2013; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003). Therefore, more research is required to understand the scope for a political communication between representatives and high-emitting constituents to further the goal of consumption-focused decarbonisation, or indeed to capitalise on short-term climate policy backlash. Given that consumption-focused decarbonisation is a requirement for reaching net zero in only 25 years from now (!) with past debates about related lifestyle changes only foreshadowing what is yet to come (Committee on Climate Change 2019, p. 155; Skidmore Reference Skidmore2023; Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick et al. Reference Verfuerth, Demski, Capstick, Whitmarsh and Poortinga2023), political researchers are called upon to advance knowledge of how policymakers can navigate the issue without creating political backlash that could ultimately prevent countries from delivering on their pledges under the Paris Agreement.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676526100681

Data availability statement

Replication files detailing the quantitative data analysis are provided alongside the article. The transcribed in-depth interviews were pseudonymised and have been archived with the UK Data Service (https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/857385/).

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at the 2023 ECPR General Conference in Prague, the 2023 ECPR Standing Group on Parliaments Conference in Vienna, the 2023 PSA Elections, Public Opinion and Parties (EPOP) conference in Southampton and in the 2023 University of East Anglia School of Environmental Science research colloquium. We would like to thank the EJPR editors-in-chief Nicole Curato and Alessandro Nai, two anonymous reviewers, as well as (in no particular order) Irene Lorenzoni, Jale Tosun, Brendan Moore, Simon Bulian (née Schaub), Andrew J. Jordan, John Kenny, Stephen Fisher, and Jorge Fernandes, for helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding statement

Funding was generously provided by the ERC (via the DeepDCarb Advanced Grant 882601), and the UK ESRC (via the Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations (CAST) (Grant ES/S012257/ and UKRI072)).

Competing interests

The authors are aware of none.

Ethics approval statement

We received ethics approval to conduct qualitative interviews on 10 November 2022 from the University of East Anglia Faculty of Science Research Ethics Subcommittee (Ethics number: ETH2223-0684).