Introduction

The police [in Brazil] are an institution designed to be violent and corrupt, yet people still wonder. Why do I say that? Because the police were created to serve the state and the elite. I enforce the law to protect and serve the status quo; that’s simple. How do you keep 2 million “favelados” under control? Engaging in repression practices?! Of course, how else do you do it? This is the political police. This is an unjust society. We are here to protect this unjust society. (Our translation of an interview by Delegado Hélio Luz, Chief of Rio de Janeiro Civilian Police 1995–97)Footnote 1

The global wave of democratization has not yielded a consistent decline in violence. In many countries, electoral institutions coexist with high levels of political and criminal violence. Research shows that elections themselves can become flashpoints for violence, targeting candidates and party officials, or exacerbating broader criminal dynamics (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2018; Rios Reference Rios2015; Blume Reference Blume2017; Novaes Reference Novaes2024). According to some accounts, democratization may exacerbate violence when it fails to include mechanisms of transitional justice, such as truth commissions capable of punishing agents of state repression from the authoritarian period (Trejo et al. Reference Trejo, Albarracín and Tiscornia2018; Cruz Reference Cruz2016). Other accounts emphasize how democratization can produce political systems and repressive bureaucracies that remain embedded within the criminal ecosystems inherited from authoritarian regimes (Feldmann and Luna Reference Feldmann and Luna2023; Jupiara and Otavio Reference Jupiara and Otávio2015). This embeddedness grants criminal actors not only protection but also the institutional access needed to influence markets, elections, and even public policies within their spheres of control (Arias Reference Arias2013, Reference Arias2018).

In Latin America, persistent institutional weakness creates particularly fertile ground for the emergence and consolidation of paramilitary and mafia-type organizations, many of which originate within the political system and security forces themselves (Snyder and Duran-Martinez Reference Snyder and Duran-Martinez2009). Following democratization, countries across the region dramatically expanded citizen rights, including voting rights and access to social entitlements such as housing, healthcare, and environmental protections (Brinks et al. Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2020). Yet this rapid expansion of rights was not accompanied by comparable gains in institutional capacity. The resulting mismatch, which was intensified by rapid urbanization (Caldeira and Holston Reference Caldeira and Holston1996) and deep social transformations, produced urban environments marked by widespread informality and endemic violence (Yashar Reference Yashar2018)Reference Rodgers. The gap between legal guarantees and their implementation gave rise to so-called “no-go” zones: areas lacking effective property rights enforcement or the rule of law (Koonings and Kruijt Reference Koonings and Krujit2006). In response, state and elite actors often backed the formation of grassroots death squads (Alves Reference Alves2003) and normalized police violence, leading to the indiscriminate use of extrajudicial executions as a tool of urban control (Brinks Reference Brinks2003; Flom Reference Flom2020; Willis Reference Willis2016).

Mafia-style paramilitary organizations are, by definition, extortionate actors that extract profits by selling protection to both legal and illegal entrepreneurs (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993). These groups often emerge in contexts where institutional trust is low and state capacity is undermined by corruption or outright abdication of authority, stepping in to organize markets and regulate interactions through coercion (Volkov Reference Volkov2002). In such settings, the state may not only fail to prevent the rise of these groups but may actively mobilize them to fulfill functions the state itself is unwilling or unable to perform, such as enforcing social norms, protecting business interests, or conducting social cleansing campaigns (Taussig Reference Taussig2005; Gill Reference Gill2009). In countries like Colombia, this dynamic has given rise to armed actors across the political spectrum: from leftist insurgencies like FARC and ELN to right-wing paramilitaries such as the “autodefensas” (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Robinson and Santos2013). These organizations often emerge as byproducts of the disjuncture between the rule of law and what is materially enforceable on the ground. In many parts of the Global South, mafias operate as the managers of an “ordered disorder,” filling governance gaps left by weak or unwilling state institutions (Gayer Reference Gayer2014). While they benefit from connections to state officials, they thrive in areas of limited enforcement, not merely because of absent capacity, but due to institutional weakness that undermines the state’s ability to discipline its own agents and bureaucracies. Nowhere is this more visible than in the pervasive impunity enjoyed by police forces in much of Latin America (Flom Reference Flom2024).

In Rio de Janeiro, militias (milícias, hereafter) represent a particularly salient example of such hybrid governance. These paramilitary groups emerged from within the state apparatus itself, drawing members from the police, fire brigade, and other militarized institutions (ALERJ 2008). Like mafias elsewhere, milícias run extortion rackets and control access to markets. Yet their business model extends far beyond protection: they derive significant profits from selling counterfeit or unauthorized versions of public services, such as electricity, gas, housing, and cable TV, that are nominally regulated or provided by the state (Willis Reference Willis2017). Their ability to operate in favelas and disordered markets, however, hinges on strategic interactions with the state. On one hand, they rely on state forces to displace rival criminal organizations and consolidate territorial control. On the other hand, they depend on the state’s deliberate inaction: a refusal to enforce urban regulations, disrupt illegal markets, or interfere in their fiefdoms. In this context, the provision of electoral services, such as mobilizing votes for allied candidates or intimidating opposition (Trudeau Reference Trudeau2024), is a key mechanism through which milícias secure bureaucratic protection. By delivering electoral capital, they shield their territories from regulatory scrutiny and legal enforcement. As such, milícias do not merely exploit institutional weakness—they actively reproduce and deepen it. We argue that this dynamic, which Hidalgo and Lessing (Reference Hidalgo and Lessing2019) term “endogenous state weakness,” forms a self-reinforcing cycle that connects criminal territorial expansion to electoral politics.

In this article, we extend existing theories of paramilitary expansion by integrating the concepts of forbearance and coercion gaps (Holland Reference Holland2016, Reference Holland, Brinks, Murillo and Levitsky2020) into a broader framework of institutional weakness. We argue that milícias consolidate territorial control and political influence not only through coercion, but through the provision of counterfeit public goods—including illegal housing, private security, and pirated utilities such as cable, wireless connection, and electricity (Willis Reference Willis2017; (Magaloni and Franco-vivanco Reference Magaloni and Franco-Vivanco2020; Müller Reference Müller2022). These services enhance their local legitimacy and embed them in everyday governance, enabling milícias to participate in electoral politics directly or to support allied candidates. According to the theory of coercion gaps, politicians strategically appoint bureaucrats who are willing to withhold enforcement in order to secure political advantages or prioritize welfarist outcomes (Holland Reference Holland2016, Reference Holland, Brinks, Murillo and Levitsky2020). In the case of milícia-controlled territories, the widespread dependence on illicit service provision creates a constituency that benefits from non-enforcement. This demand for bureaucratic forbearance, which is grounded in both coercive control and material reliance, helps explain how milícias transform territorial dominance into durable political power.

Drawing on geolocated data on milícia governance, geolocated electoral outcomes, and data on senior bureaucratic appointments for police districts’ leadership, we examine whether electoral concentration in milícia-controlled areas facilitates their political entrenchment and territorial expansion. We show that districts under milícia influence display unusually high levels of vote concentration, and that milícia-backed candidates disproportionately rely on support from areas they criminally govern. We further demonstrate that the identity of senior police commanders is strongly associated with patterns of milícia expansion, suggesting that discretionary enforcement is politically negotiated. Finally, we find that electoral concentration in the 2006 state elections—before national attention on milícia-political ties—predicts milícia growth and increased police violence in subsequent years.

Our contribution to the literature on criminal(ized) politics is twofold. First, we contribute to the literature on criminal entrenchment into politics (Feldmann and Luna Reference Feldmann and Luna2023; Arias Reference Arias2018; Barnes Reference Barnes2017; Trudeau Reference Trudeau2024) by integrating previous theoretical insights on institutional weakness into a completeand testable theoretical model explicating the links between electoral politics and milícia expansion in Rio de Janeiro. Second, we leverage a combination of qualitative and quantitative data to test the plausibility of our theoretical model through a series of empirical analyses. Combined, the insights drawn from our model contribute to explaining the resilience of the milícia groups and their entrenchment and electoral success despite clear extractive behavior.

The remainder of the article is organized into six sections. We begin by outlining the institutional context of Brazil, with a focus on the case of Rio de Janeiro. Next, we engage with existing scholarship on mafia-style organizations, criminal governance, and institutional weakness in Latin America to develop our theoretical framework and articulate specific hypotheses. We then describe our data sources and present both qualitative and quantitative findings. The following section discusses the limitations of our analysis. We conclude by highlighting broader implications and suggesting directions for future research.

Institutional Context

Politics in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro refers both to a state and to its capital city, located in Brazil’s Southeast region. The state is home to over 17 million residents, approximately 12 million of whom live in the greater metropolitan area. Within the city itself—home to roughly 6 million people—an estimated 25% of residents live in favelas, with even higher proportions in surrounding municipalities. The democratization process of the late 1980s and early 1990s expanded social inclusion, but often through clientelist arrangements (Leeds Reference Leeds1996). In such contexts, strong clientelist parties have been linked to heightened violence, as they are more likely to forge alliances with coercive actors (Nieto-Matiz and Skigin Reference Nieto-Matiz and Skigin2023).

Governance in Brazil is multilayered: municipalities are responsible for service delivery, urban regulation, and infrastructure, while states oversee public security through two distinct police forces: the Polícia Militar, tasked with patrolling and maintaining public order, and the Polícia Civil, responsible for investigations and judicial support. These overlapping responsibilities often clash in Rio’s informal settlements, where high levels of violence and institutional fragmentation severely strain the state’s capacity to govern effectively (Magaloni et al. 2020; Trudeau Reference Trudeau2024).

Brazil’s electoral calendar is staggered. Voters elect mayors and city councilors in one cycle, and governors, state and federal legislators, senators, and the president in the next. Legislative elections operate under an open-list proportional representation system (OLPR), with large, at-large districts that fuel intense intraparty competition. Under OLPR, candidates must cultivate localized support bases (or “corrals”) even though votes are tallied and ranked across the entire jurisdiction (Avelino et al. Reference Avelino, Biderman and Silva2011). In this competitive landscape, consolidating electoral strongholds in specific neighborhoods has become a key strategy (Trudeau Reference Trudeau2024), typically achieved through alliances with local power brokers (Novaes Reference Novaes2018). The resulting increase in political competition, coupled with the need to incorporate clientelist actors into governing coalitions, amplifies political influence over bureaucratic appointments (including in the police) and weakens mechanisms of accountability (Flom Reference Flom2019, Reference Flom2023).

Our electoral analysis focuses on elections to the “Assembleia Legislativa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (ALERJ),” the state’s legislative assembly. ALERJ wields disproportionate influence over bureaucratic appointments, including the selection of commanders for the state’s police districts. Over the past two decades, clientelist and center-right coalitions have dominated the legislature. Within this system, elected officials often trade bureaucratic favors, such as police protection or access to public services, for political loyalty and electoral support (Bezerra Reference Bezerra1999). These dynamics form the institutional foundation for the political-criminal exchanges that have enabled the expansion of milícias (Nieto-Matiz Reference Nieto-Matiz2023; Trudeau Reference Trudeau2024).

Milícias in Rio de Janeiro

The rise of milícias in Rio de Janeiro is widely seen as a product of Brazil’s punitive, militarized, and hierarchical approach to policing (Cano and Duarte Reference Cano and Duarte2012; Magaloni et al. 2020). Unlike drug-trafficking organizations, which were often cast as internal enemies of the state, milícias were frequently viewed as legitimate extensions of state authority. Formed primarily by current and former police officers, they emerged at the intersection of violent law enforcement and organized criminal enterprise. Their illegal practices were commonly framed as necessary to protect communities, while in practice serving to extract rents and assert territorial control. These practices are not exceptions, but rather part of a broader continuum of state-sanctioned and state-enabled violence in Brazil’s urban peripheries.

Policing in Rio has long been shaped by militarized logic. During the Military Dictatorship (1964–85), police forces were restructured for political repression, not public safety. This legacy produced institutions marked by impunity, corruption, and extrajudicial violence. Officers who excelled at suppressing enemies of the regime were rewarded (not disciplined) for abuses of power (Jupiara and Otavio Reference Jupiara and Otávio2015). Many parlayed this impunity into private gain: forming “esquadrões da morte” (death squads) financed by local business elites to eliminate suspected criminals and “undesirable” residents (Alves Reference Alves2003). Over time, these squads evolved from extrajudicial enforcers into organized criminal networks with territorial control.

By the 1990s, Rio faced surging violence linked to the expansion of illegal markets. The state’s response to double down on repression further empowered the most violent segments of the police. Political support for these tactics was bipartisan and public. In a 2006 campaign interview, Eduardo Paes (then a candidate for governor, later mayor of the capital) lamented the state’s loss of control in some neighborhoods and proposed a solution: support for milícias, which he framed as a means for the state to “reclaim” territory, citing Jacarepaguá as a success case. Paes had previously served as sub-mayor of Rio’s western zone under Mayor Cesar Maia, who openly endorsed milícia groups as “community self-defense forces” (Silva & Cocco, Reference Silva and Cocco2009; Arias Reference Arias2013). These groups, built around police officers, engaged in textbook death squad behavior, eliminating petty criminals and drug users on behalf of local businesses. Fees soon became mandatory, and the same mechanisms of impunity were repurposed to sustain extortion and enforce political loyalty. By the early 2000s, these groups had transformed into state-sponsored criminal organizations (Snyder and Duran-Martinez Reference Snyder and Duran-Martinez2009).

The Parliamentary Inquiry Commission on Milícias (“CPI das Milícias;”ALERJ 2008) classified milícia development into three stages. The first is characterized by death squads operating on behalf of business patrons. The second level indicates that these squads integrate with residents’ associations, establishing lasting sources of income. Finally, milícias achieve stable political alliances, coordinate directly with bureaucrats and law enforcement, and shape the provision of local (counterfeit) public goods like informal housing or paratransit (Hummel Reference Hummel2018; Magaloni et al. 2020). In this article, we focus primarily on this third stage, in which milícias act as political entrepreneurs embedded in the state apparatus.

Milícias operations, known colloquially as “mineira,” have long been normalized among police officers. These activities include extortion, drug and arms trafficking, contract killings, debt collection, protection rackets for informal businesses, and the control of slot machines and brothels (Misse Reference Misse2007; Paes Manso Reference Paes Manso2020). What sets milícias apart is not just the breadth of their illicit markets, but their ability to shield those markets through institutional capture. The state’s unwillingness to punish police malfeasance, coupled with internal assassination of whistleblowers (see, for instance, Soares Reference Soares2023, 210), enabled the rapid and relatively uncontested territorial expansion of these groups.

Milícia power spread most quickly through Rio’s west side and neighboring municipalities in the “Baixada Fluminense.” These areas share similar stories of origin: local death squads, initially backed by shopkeepers, were institutionalized by entrepreneurial police officers who saw in them opportunities for rent extraction far beyond vigilante justice. Milícias infiltrated or forcibly took over residents’ associations, positioning themselves as intermediaries between communities and the state at a time when Brazil’s democracy was decentralizing and urban governance was being renegotiated (Arias Reference Arias2013; Alves Reference Alves2003; Paes Manso Reference Paes Manso2020).

Milícias’ comparative advantage lay in combining coercive power with political capital. By offering votes, campaign finance, and some types of constituent demands, milícias became indispensable to politicians seeking local bases. They demobilized legitimate community leadership (Arias Reference Arias2013), captured participatory institutions, and gained de facto control over public investment and service delivery (ALERJ 2008; Werneck Reference Werneck2015). This enabled them to regulate nearly every facet of local economic life, from utilities and housing to transportation and credit.

Paes’s 2006 interview reflected how deeply embedded these groups had become in mainstream politics. Framed as a “lesser evil” when compared to drug factions (Chaves Reference Chaves2008), milícias enjoyed tacit support from large segments of the political establishment. Their expansion into Rio’s northern zones brought them into direct conflict with Comando Vermelho (CV) and other trafficking gangs. The typical pattern of takeover was as follows: a police operation weakens a rival group through arrests or killings, after which the territory is immediately invaded by a milícia faction. Often, the invading group had coordinated the police action itself (Soares Reference Soares2023, 234). Trudeau (Reference Trudeau2022) documents a causal link between police raids and increases in civilian deaths, showing how state power was selectively mobilized to favor certain criminal groups.

In 2006, CV launched a series of violent protests—burning buses, attacking police—to denounce what it called the advance of the “comando azul” (milícia forces).Footnote 2 Internal intelligence reports from 2008 (Paes Manso Reference Paes Manso2020, 79) revealed that 171 favelas were under milícia control, with 52 of those taken from rival gangs following police operations. Milícias did not merely fill a governance vacuum: they leveraged state violence, electoral politics, and bureaucratic impunity to actively construct and defend their own criminal territories.Footnote 3

Milícia Engagement in Democratic Governance

To document the expansion of the milícias in Rio de Janeiro, we build on the insights of the literature on mafias and private protection markets, emphasizing how mafiosi services emerge primarily as substitutes for state institutions that are unwilling or incapable of governing specific economic transactions effectively. Following this, we situate the challenge of public goods provision within contexts characterized by violence, poverty, distributive conflicts, and electoral competition. By bridging the literature strands on mafia electoral engagement and institutional weakness in Latin America, we introduce our theoretical framework linking state-sponsored militia expansion to the availability of coercion gaps to be exploited by criminals.

Gambetta’s (Reference Gambetta1993) seminal work demonstrates how pervasive distrust, fragile property rights, and deficient enforcement mechanisms fuel the demand for private protection in Sicily. Mafiosi are conceptualized as specialized entrepreneurs using credibility as their primary asset. Their effectiveness stems from their capacity to manage societal mistrust and govern interactions in areas where the state fails to do so. This dynamic was similarly evident in post-Soviet states, where the collapse of centralized authority and the rapid shift toward capitalist markets outpaced the regulatory capabilities of emerging institutions, creating substantial gaps quickly filled by violent entrepreneurs (Volkov Reference Volkov2002). In such environments, mafiosi provided essential governance services, including contract enforcement, debt collection, as well as protection from petty crime.

Mafiosi also critically regulate illegal sectors of the economy. Cartels, whether engaged in illegal activities such as drug-trafficking or corruption in public procurement processes, typically face internal trust deficits (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993). Since disputes cannot be adjudicated by the state, mafiosi function as reliable arbiters, enforcing cooperation through credible threats of violence. Their reputation for violent enforcement and privileged access to information creates a distinct competitive advantage. Consequently, mafiosi roles attract individuals with pre-existing proficiency in violence, such as former military personnel or dismissed law enforcement officers, as extensively documented in post-Soviet Russia (Volkov Reference Volkov2002; Varese Reference Varese2006), Colombia (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Robinson and Santos2013), and Rio de Janeiro (Paes Manso Reference Paes Manso2020; Alves Reference Alves2003).

Quantitative analyses of mafiosi engagement in legitimate economic sectors further illustrate their adaptive responses to institutional failures. For instance, Buonanno et al. (Reference Buonanno, Durante, Prarolo and Vanin2015) identify historical mafia proliferation in southern Italy associated with labor-intensive industries such as sulphur mining, following institutional disruption. Dipoppa (Reference Dipoppa2021) provides evidence of mafia involvement in labor market regulation, controlling illegal southern migrants in northern Italy to circumvent labor laws while delivering electoral support to the ruling Christian Democratic Party. Similarly, Acemoglu et al. (Reference Acemoglu, De Feo and De Luca2020) show mafias emerging to protect agricultural profits against leftist peasant movements, highlighting mafia roles as defenders of the economic status quo in vulnerable markets. Alves (Reference Alves2003) recounts analogous instances in Rio de Janeiro, where early death squads provided protection for local businesses, reflecting a consistent pattern wherein mafiosi uphold property rights selectively to those who afford protection fees.

Recent scholarship underscores the direct political participation of mafiosi. Driven by their need for protection against state intervention, mafiosi strategically engage in electoral politics, aiming to capture state institutions rather than openly confronting them (Daniele and Dipoppa Reference Daniele and Dipoppa2017). These alliances with political actors facilitate mutually beneficial arrangements, providing mafiosi with non-enforcement of laws, policy influence, and state resources, while politicians secure votes mobilized through mafiosi networks (Dipoppa Reference Dipoppa2021; Trudeau Reference Trudeau2024). Violence against political opponents who threaten their interests further exemplifies their coercive political strategies (Blume Reference Blume2017; Feo and Luca Reference Feo and Luca2017; Rios Reference Rios2015; Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2018).

Central to mafiosis’ electoral influence is their embeddedness within local communities. Arias (Reference Arias2018) argues that criminal organizations exploit “back-channel” connections with policymakers, simultaneously providing constituent services like infrastructure upgrades and facilitating basic services such as healthcare or childcare placements. Although ostensibly legitimate democratic actions, these services enable mafiosi to externalize and legitimize their political preferences by presenting themselves as grassroots community representatives (Arias Reference Arias2018). This influence can manifest either as participation, co-optation, or outright domination of local political institutions (Lessing Reference Lessing2020).

Building on these insights, our theory views milícia expansion as driven by deliberate gaps in state enforcement, what we call state-sponsored coercion gaps, which local political actors strategically maintain. As such, we argue that milícias flourish precisely because their provision of counterfeit public goods and their political connections mutually reinforce conditions of institutional weakness, which in turn facilitates their territorial and political consolidation.

Our Argument

State-sponsored Coercion Gaps: State Inaction as a Market and Electoral Strategy

Building on Holland’s (Reference Holland2016, Reference Holland, Brinks, Murillo and Levitsky2020) concept of forbearance—when state officials deliberately refrain from enforcing laws to mitigate distributive harm—we conceptualize milícia power in Rio de Janeiro as a form of strategic, violent forbearance embedded in a broader political economy of coercion. Milícias have evolved from informal security actors into political entrepreneurs who exploit institutional inaction to dominate both markets and electoral spaces. Few places illustrate this dynamic more clearly than Rio, where milícias have systematically transformed forbearance into an opportunity for territorial governance and political power.

Initially formed by police officers leveraging their institutional training and authority, milícia groups gained ground not just through coercion but also through state-backed legitimacy. Supported by public subsidies and equipped with heavy weaponry, they emerged as de facto governing agents in marginalized communities (Cano and Duarte Reference Cano and Duarte2012; ALERJ 2008). Their power was bolstered by selective state inaction (or coercion gaps) in which key political actors chose not to disrupt their territorial control. Rather than merely filling governance vacuums, milícias became active participants in shaping local political economies.

This evolution was underpinned by a mutually beneficial relationship with political elites. Indifference by some and active collusion by others enabled milícias to offer protection, public goods, and clientelist favors in exchange for electoral support (for an example, refer to “Case 3” in Appendix 2c). This clientelist logic allowed milícias to act as local gatekeepers, deciding who gets housing, basic utilities, or economic opportunity. They reinforced their political base by strategically concentrating votes (Soares Reference Soares2023, 265) within their territories. Evidence shows that milícias often deliver decisive margins to aligned politicians (Trudeau Reference Trudeau2024).

Milícias exploit a wide array of markets based on counterfeit public goods (i.e., services that mimic state provision but operate through violence and exclusion). These include illegal paratransit services, stolen electricity and Internet, black-market gas and water, and unregulated housing (Willis Reference Willis2017; Benmergui and Gonçalves Reference Benmergui and Gonçalves2019; Hirata et al. 2020). The state’s unwillingness to enforce property rights in these territories creates a space where milícias thrive. Importantly, any attempt to shut down these services would severely disrupt life for residents, undermining both local economic stability and politicians’ electoral prospects.

Take, for example, the case of Muzema, a milícia-controlled neighborhood in Rio with a history of informal housing collapse. In Muzema, the state’s failure to provide public housing forced residents into illegal constructions. Bureaucrats refrain from enforcing zoning and construction regulations, not merely out of benevolence (as Holland’s welfarist model would suggest) but because such enforcement would harm poor voters and jeopardize political alliances. Politicians, aware of the electoral costs, appoint bureaucrats whose non-enforcement preferences align with their own. Within this arrangement, milícias extract rents, launder capital through real estate development, monitor bureaucratic behavior, and deliver votes to politicians perceived as allies.

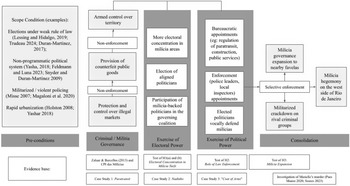

Figure 1 presents a stylized model of how milícias consolidate territorial and political power in contexts characterized by state fragmentation and weak rule of law. The model begins by identifying key scope conditions that allow criminal governance to emerge. These include regular and proportional elections held under weak judicial enforcement (Hidalgo and Lessing Reference Hidalgo and Lessing2019; Trudeau Reference Trudeau2024); non-programmatic, clientelist political systems (Yashar 2018; Feldmann and Luna 2023); militarized policing (Misse Reference Misse2007; Magaloni et al. 2020); and rapid urbanization that gives rise to large informal settlements (Caldeira and Holston Reference Caldeira and Holston1996).

Figure 1 . A Model of Milícia Expansion.

At the foundation of milícia operations are illicit markets, such as drug trafficking, gambling, and extortion, that generate the initial resources needed to sustain their activities. As these groups consolidate territorial control, they expand into the provision of essential goods and services, investing in basic infrastructure to secure long-term rents. By supplying urban infrastructure in underserved areas, milícias bolster their legitimacy among residents and position themselves as de facto or “parallel” state actors. In these contexts, they establish criminal governance through armed control of territory, protection rackets, and the delivery of counterfeit public goods. This form of governance is upheld not only through coercion, but also through state forbearance: a deliberate non-enforcement of laws that allows illegal markets to operate and unauthorized services to persist (Holland Reference Holland2016), effectively delegating aspects of governance to criminal groups.

Milícias were born within the state during the dictatorship and then transitioned into exercising electoral power as democracy spread, using their territorial dominance to influence elections and benefit in their roles as political brokers (see, for instance, Trudeau Reference Trudeau2024). We expect that electoral support will be concentrated within their territories, where coercion, clientelism, and vote brokerage distort democratic competition. This concentration benefits political elites, who in turn reward milícias by appointing loyal police commanders, inspectors, and bureaucrats in key regulatory agencies, and other key positions through which selective enforcement is negotiated (Soares Reference Soares2023). Elected officials further insulate milícia territories from state interference by vocally defending these groups or incorporating their representatives into governing coalitions. This exchange of votes for bureaucratic protection allows milícias to gain political power, which, in turn, enables milícias to expand to adjacent favelas, where they replicate their model of governance. Selective enforcement, backed by bureaucratic and political allies, ensures that rival groups face state crackdowns while milícia territories remain untouched. This asymmetry consolidates milícia hegemony, particularly in the western zones of Rio de Janeiro, while deepening their entanglement with the formal political system.

The linchpin of this model is the ability to construct and maintain coercion gaps. These gaps are not just the absence of enforcement, but rather the result of deliberate political choices. Milícias operate simultaneously on both sides of the transaction: they are the bribe-givers and the bribe-takers. Their networks include law enforcement officers, elected politicians, and private contractors working together to secure non-intervention in milícia-dominated territories. Importantly, this structure would be fragile if it relied solely on force. What makes it resilient is the integration of political capital. Milícias deliver votes, mobilize constituencies, and even run their own candidates for office (ALERJ 2008; Daniele and Dipoppa Reference Daniele and Dipoppa2017). Their ability to shape bureaucratic appointments and influence law enforcement priorities creates a self-reinforcing cycle in which political and economic power are mutually reinforcing. In short, milícia power in Rio de Janeiro is not a deviation from state authority, but its perverse extension. By selectively abstaining from enforcement, the state creates opportunities for criminal governance. Through their ability to co-produce services, enforce order, and deliver votes, milícias exploit these coercion gaps to become indispensable actors in both markets and elections. Understanding their expansion thus requires attention not only to their violent capacities but also to the political strategies that sustain them.

Hypotheses

While our theoretical model identifies multiple mutually reinforcing mechanisms through which milícias consolidate power, ranging from coercive violence and market control to electoral brokerage, this article focuses empirically on one central dynamic: the political construction of coercion gaps. These gaps emerge not as passive enforcement failures, but as deliberate, negotiated absences made possible by the exchange of votes for bureaucratic protection.

We argue that milícias leverage their territorial dominance to deliver concentrated electoral support to aligned politicians. In return, these politicians influence the bureaucratic apparatus by appointing loyal police commanders and regulatory agents who ensure selective enforcement. The resulting non-intervention in milícia territories enables their criminal governance to expand outward: from market control to territorial consolidation and electoral entrenchment. From our theoretical model, we derive the following testable hypotheses:

H1: Milícia presence increases electoral concentration:

H1a: Polling stations under milícia influence should exhibit higher levels of vote concentration than those not under their control.

H1b: Milicia-affiliated politicians running for office should benefit from larger vote shares in the areas that are controlled by milícias aligned with their interests.

H2 (Political power): Milicia expansion should be strongly associated with the identity of senior police commanders, particularly in jurisdictions where milícia-linked politicians wield influence. This reflects the crucial role of discretionary enforcement—or lack thereof—in enabling territorial takeover. The goal of this test is to measure the impact of law enforcement alignment (e.g., through bureaucratic and regulatory appointments) on milícia expansion.

H3 (Milícia consolidation): Jurisdictions with higher electoral concentration in time t should predict milícia expansion in the subsequent years. This reflects the notion that political capital, which is delivered in concentrated vote blocs, enables milícia actors to shape enforcement patterns indirectly through bureaucratic appointments.

These hypotheses anchor our empirical strategy in a theory of political-criminal exchange: milícia actors deliver electoral services and bureaucratic compliance in exchange for territorial autonomy and access to illicit rents. Elections, under this logic, are not threats to their survival but tools for consolidating and legitimizing their power.

Methods, Data, and Sources

We test our theoretical expectations using original data from Rio de Janeiro that bring together evidence on milícia presence, electoral behavior, and law enforcement. Our strategy links geospatial and electoral records with detailed information on bureaucratic appointments, allowing us to trace the mechanisms behind milícia expansion.

Our key variable of interest (i.e., territorial control by milícias) is derived from Zaluar and Barcellos (Reference Zaluar and Barcellos2013), a georeferenced dataset covering criminal governance in over 950 favelas across multiple years. We combine this with electoral data from the FGV Cepespdata project, which includes polling station-level results and geolocation. Information on police behavior, including enforcement activity and jurisdiction commander appointments, is drawn from public administrative records published by the Institute for Public Safety of Rio de Janeiro (ISP-RJ). A table describing all variables is available in the supplementary material (Table A1).

To trace elite-milícia linkages and the political construction of coercion gaps, we also incorporate qualitative and documentary evidence, including the CPI das Milícias (2008) and the ongoing federal investigation into the assassination of Marielle Franco. These sources, alongside in-depth investigative journalism (e.g., Paes Manso Reference Paes Manso2020; Soares Reference Soares2023), offer crucial qualitative evidence on how vote delivery and bureaucratic non-enforcement are exchanged. A table describing the selected milícia-linked candidates is available in the supplementary material (Table A2).

We conduct quantitative tests at multiple levels of analysis. Tests 1 and 2 correspond to Hypotheses 1a and 1b and use the polling station as the unit of analysis. Management is assigned based on whether the polling station is located near a favela with an observed milícia presence. These tests draw on data from three election years that overlap with our data on criminal governance: 2006, 2010, and 2014. Tests 3 and 4 address Hypotheses 2 and 3, respectively. Both use the CISP, a joint police jurisdiction, as the unit of analysis and focus on the 2006–10 period. Test 4 leverages temporal variation to assess whether electoral concentration in 2006 predicts milícia expansion in subsequent years (t+n). Additional methodological details and source documentation are available in the supplementary material.Footnote 4

Essential Service Provision and Government Infiltration

Our theory seeks to clarify the mechanisms linking the provision of counterfeit public goods as a tool of territorial control to the exercise of political and electoral power, culminating in territorial consolidation. To substantiate these claims and provide empirical grounding for our proposed mechanisms, we draw on three case studies that illustrate how the provision of counterfeit public goods, particularly paratransit services, facilitated the accumulation of political capital and the consolidation of power by milícia leaders in the urban peripheries of Rio de Janeiro. While these cases are explored in detail in the supplementary material, we present here a brief overview of the broader context: a series of investigations into paratransit in Rio during the late 1990s and early 2000s, a period when milícias were beginning to assert substantial territorial control.

We then discuss two of the most influential milícia-linked political figures in the West Zone: the so-called “Coat of Arms”Footnote 5 brothers and Nadinho from Rio das Pedras. Among all illicit activities operated by milícias, paratransit stands out as the most expansive and lucrative (ALERJ 2008). Unlike other businesses that operate primarily within no-go zones (Koonings and Kruijt Reference Koonings and Krujit2006), the illegal van networks controlled by milícias are important connectors between Rio de Janeiro’s favelas and wealthier parts of the city where employment is concentrated.

Despite its importance, paratransit in Rio has remained poorly regulated since its inception. As we detail in Appendix 2a, the sector is deeply intertwined with both corruption and violence. Paratransit epitomizes what Holland (Reference Holland, Brinks, Murillo and Levitsky2020) describes as a “coercion gap”: it is illegal and should, in principle, be repressed by state actors, yet it provides essential mobility for workers and students, making it politically costly to enforce prohibitions. As a result, local politicians are often incentivized to tolerate or even tacitly support the service, preferring to frame its provision as informal rather than criminal. This tension between legislation and enforcement in coercion gaps creates a regulatory vacuum that attracts “strongmen” who step in to provide informal governance and generate rent streams (Morais and Brasil Reference Morais and Brasil2021).

Although milícias already held sway within their territories, their control over paratransit allowed them to extend their reach and entrench their political influence. By co-opting local enforcement agencies and intimidating opponents, milícia-controlled van networks often operate through cooperatives that function as fronts for criminal control (ALERJ 2008, p. 112). One such figure is “Batman,” a known miliciano who worked under Navidad and his brother.Footnote 6 While publicly denying any milícia affiliation, he admitted to carrying weapons and collecting protection payments from van operators. He is infamous for having escaped from a maximum-security prison in Rio through the front door (O Globo Reference Globo2011).

Given the broad-based coalitions that define Brazilian politics and, in particular, local politics in Rio de Janeiro, paratransit rents in areas like Rio das Pedras offer strong incentives for figures like Nadinho (Appendix 2b), Navidad, and others to seek elected office. Holding political power allows them to appoint allied bureaucrats and protect their interests as paratransit bosses. There is substantial evidence that transportation demand studies were deliberately manipulated to favor illegal van operators (ALERJ 2008, 114), and that external candidates often have to contract local van services simply to campaign in milícia-controlled territories (ALERJ 2008, p. 60).

Our final case (Appendix 2c) examines the “Coat of Arms” brothers, who rose to become among the most powerful politicians in Rio before being implicated in the assassination of city councilwoman Marielle Franco. Investigations revealed that the “Coat of Arms” brothers ordered her killing because her political agenda clashed with the milícia model of urban expansion. Her mandate opposed efforts to grant preferential urban development rights—typically afforded to favelas—to illegally occupied areas targeted by milícia-led land grabs. She supported community groups resisting these expansion plans, challenging the brothers’ strategy of using residents’ associations as vehicles for formalizing and profiting from illegal land development.

The brothers allegedly hired a former police officer turned contract killer to execute the hit, promising him the right to exploit newly developed areas, extracting rents from basic service provision, including electricity, internet, gas, water, cable TV, vans, and motorcycle taxis. The assassin was eventually arrested and cooperated with federal authorities, revealing that the homicide unit had deliberately obstructed the investigation; a pattern he described as common in Rio’s homicide division. He testified that the brothers had promised him a path to ascend from contract killer to full-fledged miliciano by carrying out the murder.

Quantitative Results

Milícia Presence and Electoral Concentration in Proportional Elections

To empirically assess the political influence exerted by milícia groups, we apply the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a measure commonly used to evaluate market concentration, adapted here to electoral contexts. Specifically, we use the HHI to gauge voting concentration within polling stations, hypothesizing that milícia-dominated territories experience systematically higher levels of vote concentration due to gatekeeping, coercion, intimidation, or clientelistic strategies. We estimate the following regression model:

In this equation, HHI_lt represents the sum of squared vote shares (Σ Vote Share2) at each polling station l during election t, capturing electoral concentration. Milicia_lt is a dummy variable indicating milícia control over the nearest favela, while X_lt includes controls such as the log distance from polling stations to favelas and the local social development index (SDI). We also incorporate the duration of milícia control (Years_Milicia) as both continuous and discrete variables. All models include fixed effects for polling stations and election periods.

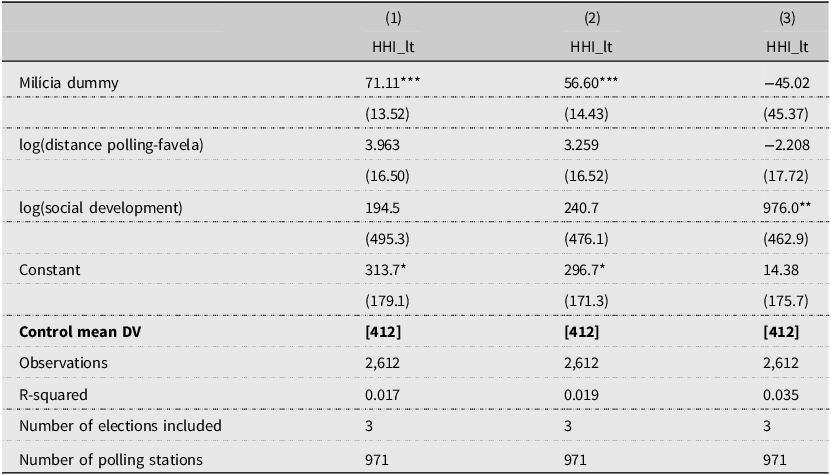

The results presented in Table 1 suggest a strong association between milícia presence and higher voting concentration. The estimated coefficients on milícia presence and duration are consistently positive and statistically significant at conventional levels. Specifically, polling stations located near favelas with four years of documented milícia presence exhibit an increase of approximately 320 points in the HHI—roughly 77% of the control group mean.

Table 1. Regression Models for Electoral Concentration and Milícia Presence

Robust standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors are clustered at the polling station level. Model (2) includes omitted controls for a continuous measure of “years of milícia governance,” while model (3) includes a full set of dummies representing “years of milícia governance.”

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

While these findings are consistent with our first hypothesis, namely that milícia control facilitates territorial concentration, we note that this estimation strategy does not permit causal claims. We interpret the results as suggestive and consistent with a pattern of increased electoral concentration in areas under prolonged milícia governance, potentially reflecting coercive or clientelistic electoral strategies. Descriptive statistics can be found in Table A4.

Voting Concentration and Milícia-Affiliated Candidates

To further substantiate our theory linking milícia groups with electoral behavior, we examine the voting patterns associated with known miliciano politicians using the following regression specification:

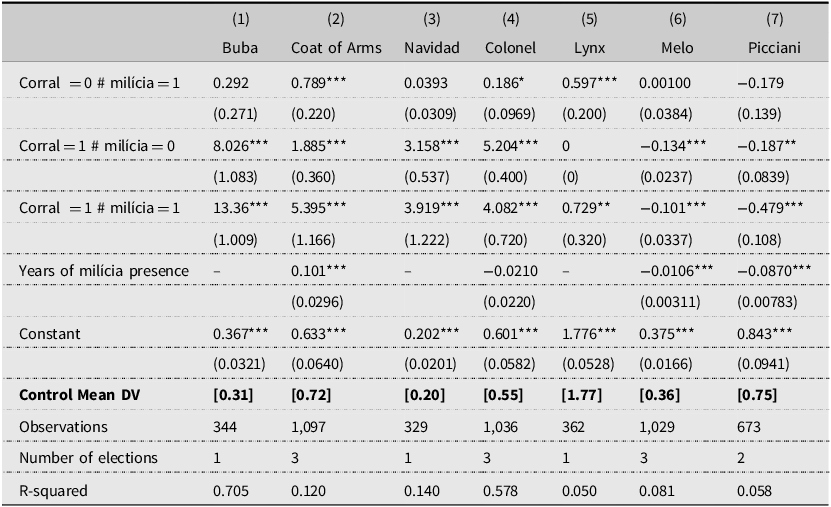

In this specification, the dependent variable (Y_lt) represents the percentage of votes obtained by a candidate at polling station l during election t. The variable Milicia_lt identifies polling stations geographically proximate to milícia-controlled territories, based on groundbreaking ethnographic data from Zaluar and Barcellos (Reference Zaluar and Barcellos2013). Meanwhile, Corral_lt signifies polling stations within areas explicitly documented by CPI das Milícias as being largely influenced by particular candidates.Footnote 7 The interaction term (Milicia_lt × Corral_lt) captures the compounded electoral effect of localized milícia control combined with politician-specific influence.

We analyze the voting behavior of known milicianos (1–5) as well as longtime clientelistic politicians (6–7) who are our placebos. On the miliciano side, we look at “Buba,” who was a Civilian Police officer extensively involved in milícia operations and extortion schemes in Santa Cruz, arrested following the “CPI das Milícias investigation”; the “Coat of Arms,” which we provided a detailed case study in the appendix; “Navidad” (also known as ‘Kills Laughing’) is a former police officer who, alongside his brother, operated Rio’s largest and most notorious milícia network, managing multiple vote extraction schemes. He is currently incarcerated, and his brother was murdered shortly after release; “Colonel,” a military police colonel with considerable political clout in Bangu, was identified by CPI das Milícias as closely aligned electorally with local milícia groups. Despite severe allegations, he remains active in state politics; and, finally, “Lynx,” who was the head of Rio’s Civilian Police, was implicated as a major political facilitator of milícia groups’ expansion on the west side. “Lynx” was arrested in 2008 and expelled from ALERJ. In 2025, he was controversially reinstated to the Civilian Police.

As placebo tests, we also analyze two historically influential, clientelistic politicians without explicit milícia connections—Melo and Picciani—both former speakers of the state assembly, implicated in corruption but lacking documented milícia affiliations. Systematic information on all analyzed candidates is available in Table A2. See descriptive statistics on vote shares in Tables A5 and A6.

The regression results presented in Table 2 reveal significantly heightened electoral support for known miliciano politicians within their designated corrals, particularly when polling stations are within milícia-controlled areas. For example, vote shares for “Buba” and “Navidad” are substantially higher within their respective strongholds (13.36% and 3.92%, respectively; both significant at p < 0.01). Similar, though smaller, patterns are observed for the “Colonel” (4.08%) and “Lynx” (0.73%, significant at p < 0.05).

Table 2. Regressions Using Vote Share in Polling Stations as a Proxy for Voting Concentration

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

In contrast, placebo candidates Melo and Picciani show no electoral advantage from proximity to milícia territories. Rather, their vote shares are either unaffected or negatively associated with milícia presence. These patterns suggest that elevated electoral support is not only a byproduct of broader political dynamics in these territories but may be specific to candidates with direct ties to milícia networks. Given that the average candidate receives approximately 0.26% of votes per polling station, and successful (elected) candidates average around 0.81%, the vote shares observed for milícia-linked candidates represent considerable outliers. These deviations, which stand out when compared to the overall distribution of vote shares (median = 0.26%, 90th percentile = 1.93%, 99th percentile = 9.6%), are consistent with the possibility of strategic electoral coordination or coercive practices. We interpret these findings as suggestive that milícia-affiliated politicians can leverage territorial control to distort local electoral outcomes.

The Association between Police Leadership and Milícia Expansion

The “CPI das Milícias” (ALERJ 2008) revealed several ties between police officers and other public agents and the milícia groups operating in Rio de Janeiro. The investigation resulted in the indictment of politicians and state agents, and documented cases in which senior police officials allegedly used state resources to expand their criminal enterprises. Drawing on data from police operations in Rio de Janeiro’s metropolitan region between 2006 and 2018, the GENI-UFF project shows that police incursions disproportionately target territories controlled by drug-trafficking gangs while largely sparing milícia-dominated areas (Hirata et al. 2020). As of 2019, milícias governed approximately 51% of criminally controlled areas in the metro region, yet accounted for less than 3% of violent police operations. In contrast, areas dominated by drug gangs such as the CV were subject to daily raids and received over 78% of such incursions (Hirata et al. 2020). Similarly, Monteiro et al. (Reference Monteiro, Fagundes and Guerra2020) show that an increase in police killings in a given jurisdiction is not followed by a reduction in other crimes, nor is it associated with the apprehension of rifles or other heavy weaponry, which are often cited as official justifications for violent or deadly incursions into favelas. Finally, Trudeau (Reference Trudeau2022) shows that police actions not only fail to reduce violence but often lead to an increase in civilian deaths in the days that follow.

So far, the analysis of previous work in Rio de Janeiro and the qualitative evidence by the CPI are consistent with our theoretical expectations (H2). To gain some empirical traction, we conduct association tests combining different sources of data. First, we combine geospatial data for police districts and crime levels with the table containing the names of two types of police leadership for each jurisdiction for each year: Military and Civilian Police. These data sets are made publicly available by the Public Safety Institute of Rio de Janeiro (ISP-RJ). We also compile a time-series of the type of gang governance for most favelas in the city of Rio de Janeiro, containing the name of the dominant drug-trafficking gang, or if it is dominated by milícias, for each year in over 900 favelas (Zaluar and Barcellos Reference Zaluar and Barcellos2013). This data is available annually between 2005–10.

To assess whether changes in local police leadership are associated with the territorial expansion of milícia groups, we conduct Pearson’s Chi-squared tests on categorical data from 2005 to 2010. The Chi-squared test evaluates whether two categorical variables are statistically independent by comparing observed versus expected frequencies under the assumption of random distribution.

We construct a favela-level binary variable indicating whether governance in a given year shifted from another actor (e.g., CV, TCP, ADA, or neutral) to milícia control. We then test whether this change is associated with the identity of the senior police officer in charge of the relevant jurisdiction (133 individuals across the period). Results reveal a strong statistical association between police leadership and subsequent shifts to milícia control. For military police commanders, we obtain a Chi² = 832.61 (p = 0.000); for Civilian Police commanders, Chi² = 757.08 (p = 0.000). In both cases, we reject the null hypothesis of independence between the variables. These results indicate a non-random relationship between the identity of police leadership and the timing and location of milícia takeovers. Full contingency tables are provided in Tables A9 and A10 in the appendix.

According to the contingency tables used in the Chi² analysis, 154 of milícia takeovers (representing 57% of all such events) in this period took place under four military police commanders. While some of these individuals have been investigated for alleged criminal activity, most received official commendations from the Rio de Janeiro State Assembly. Subject A, for instance, oversaw a police operation as a major that resulted in six deaths in a West Zone favela; at the time, they were awarded a cash bonus for the operation. Later, as a district commander, Subject A oversaw approximately 80 milícia takeovers within the territory under their authority. In 2005, they were formally decorated upon the recommendation of a state deputy who would later be identified as a milícia leader in the CPI report. Subject A was subsequently accused of administrative misconduct for allegedly managing a fraudulent vehicle rental contract in collaboration with the then-state secretary of public safety. Subject B, another commander under whose leadership milícia expansion was concentrated, was interviewed in a news report about rising milícia activity within their jurisdiction. When questioned about the expansion, they stated:

It was the population’s trust in our work that made drug dealers leave the favelas. After people experience the pleasure of not being oppressed by criminals, they do not come back. If someone reports a crime and realizes something was done about it, without them being compromised or put at risk, they develop a bond with us. So, they stop drug dealers from returning. The merit lies with the community. (Authors’ translation of a news article, c.2005)

Among Civilian Police leaders, eight individuals were in office during 166 of the 269 documented milícia takeovers between 2005 and 2010—approximately 61% of all such events in the period. Subject C, for example, was in command during 27 milícia takeovers and was later summoned for a closed-door hearing by the CPI. They were eventually dismissed from the force after posting misogynistic remarks on Twitter. Subject D oversaw approximately 24 takeovers. They were later removed from duty following public backlash over comments made during an investigation into the murder of a television journalist, in which they implied the victim was partially to blame for reporting in a high-risk area.

Subjects E and F were explicitly named in the final report of the CPI (ALERJ 2008) as having overseen 22 and 44 takeovers, respectively, while serving in leadership positions. According to the commission’s findings:

The modus operandi for occupying a community varies. When there are drug dealers in the targeted area, the use of force is employed, using, illegally, their public function and the official mechanisms of state security. When there are no drug dealers, but populations resist, the milícia robs houses and stores. (Authors’ translation from ALERJ 2008, 44)

Electoral Concentration and Subsequent Territorial Consolidation

Building on the previous HHI analysis, we investigate whether electoral concentration in legislative elections predicts subsequent territorial expansion by milícia groups. To test this hypothesis, we extend our dataset by integrating geospatial data on polling stations and voting returns in Rio de Janeiro from the Centro de Economia e Política do Setor Público (CEPESP, Reference CEPESP2024). For each police district (CISP), we calculate a HHI of vote concentration in the 2006 state deputy elections, denoted as HHI_CISP. This measure captures the degree of electoral competitiveness in each jurisdiction: higher values indicate greater concentration of votes among fewer candidates.

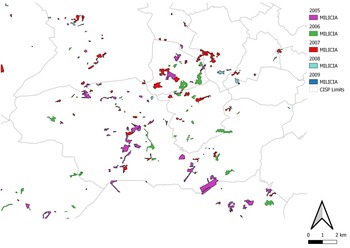

Our theoretical expectation is that high levels of electoral concentration signal milícia influence and coordination in vote delivery, which in turn facilitates future territorial expansion. We test this by modeling the number of new favelas subjugated by milícia groups in each jurisdiction over the subsequent electoral cycle (2007–10). We also include a baseline control for pre-existing milícia presence in 2006 (%Milicia_Baseline), drawn from Zaluar and Barcellos (Reference Zaluar and Barcellos2013), as well as the local SDI. To further explore the connection between electoral concentration and state-sanctioned violence, we estimate a second set of regressions using the annual number of police killings per 100,000 inhabitants in each CISP as the dependent variable (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mapping Milícia Expansion Within CISPs. Note: Figure created by authors using Rio de Janeiro state data and Zaluar and Barcellos (Reference Zaluar and Barcellos2013). Each favela is color-coded by the year of initial milícia control. Gray lines represent CISP (police district) boundaries.

The primary model estimated is:

Where Y f is a count variable, containing the number of favelas taken over by a milícia in the past year (Milícia Conquest) within that jurisdiction. And β is our parameter of interest. Standard errors are clustered at the jurisdiction level to ensure they are estimated correctly under intracorrelation (Table 3).

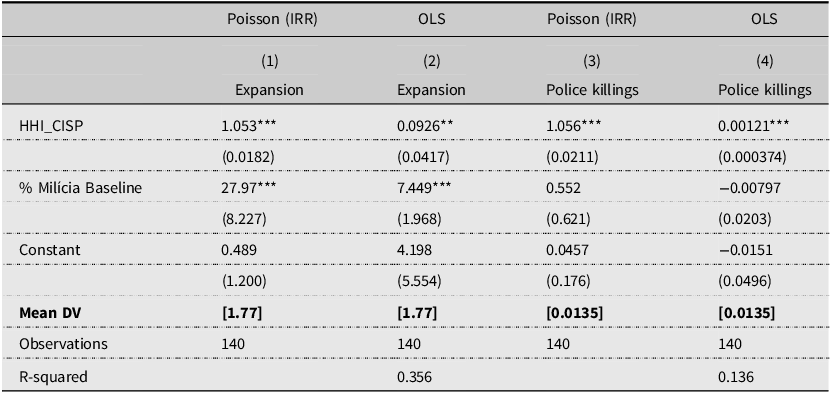

Table 3. Poisson and OLS Estimate of Model 3

Robust standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors are clustered at the jurisdiction level.

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Models include controls for social development and year dummies.

Table 3 presents the Poisson and OLS regression results. The estimates indicate a strong and statistically significant correlation between electoral concentration and milícia expansion. In particular, a one-point increase in HHI_CISP is associated with a 5.3% increase in the number of new milícia takeovers within a jurisdiction (Poisson, p < 0.01) and with a 5.6% increase in police killings (OLS, p < 0.01). These patterns suggest that electoral centralization not only facilitates milícia-political entrenchment but also coincides with increased levels of state violence, potentially used to eliminate rivals or solidify territorial control.

Additionally, the share of favelas already controlled by milícias in 2006 remains a robust predictor of both further expansion and electoral centralization, indicating that these groups tend to consolidate power in already-penetrated areas. The consistency of the Poisson and OLS estimates strengthens the empirical validity of these results. As a robustness check, we re-estimate the models using only police districts with milícia governance in the baseline (see Table A7) in the supplementary material.

Overall, these findings provide evidence supporting our theoretical argument: milícia groups leverage electoral coordination to entrench themselves politically, which in turn facilitates their territorial expansion and instrumental use of state coercive power. In this context, political capital and state violence are not separate domains but mutually reinforcing assets within the milícia business model.Footnote 8

Discussion

This study investigates the complex and often pernicious relationship between electoral politics, coercion gaps, and the expansion of criminal governance, focusing on the case of milícias in Rio de Janeiro. Drawing on multiple sources of data and a novel theoretical framework, we argue that milícias do not merely emerge in the absence of the state but are often enabled and protected through strategic political behavior. These alliances exploit what we term state-sponsored coercion gaps: patterns of selective enforcement where state actors deliberately abstain from regulating illicit markets in exchange for political-electoral returns (Holland Reference Holland, Brinks, Murillo and Levitsky2020). Such gaps are not the byproduct of state failure; rather, they are cultivated by politicians, through the control of state appointments, seeking the organizational and electoral resources that criminal groups can provide.

Our empirical analysis substantiates the plausibility of our claims by documenting a robust association between milícia presence, bureaucratic appointments, and electoral concentration. We first show that milícia presence drives electoral concentration and increases the vote share for aligned candidates. We also demonstrate that the identity of the senior bureaucrats running a police district is strongly correlated with the expansion of milícia groups within that territory. We substantiate this correlation by providing qualitative evidence that senior law enforcement officers have abided milícias’ territorial expansion. Last, we test the hypothesis that electoral concentration within a police district in the 2006 election should predict milícia expansion within that jurisdiction in subsequent years and find a significant correlation. Overall, we argue for a self-reinforcing theory of milícia power where milícias expand through sequential rounds of electoral concertation and political appointments.

We argue these findings have important implications for how we think about criminal consolidation: under conditions of fragmented political authority and institutional weakness, democratic competition may inadvertently incentivize political actors to collude with organized crime. Far from being antithetical to democratic practice, milícias have become embedded within it: providing order, mobilizing votes, and delivering services that, while counterfeit, are nonetheless essential to many. In return, politicians offer impunity, facilitating a mutually reinforcing exchange that transforms elections into vehicles for the consolidation of criminal power. We further argue that state intervention in those disordered counterfeit markets is a necessary––although not sufficient––condition for the state to regain control of the territories exploited by milícia groups.

Despite the strength of our findings, our paper has important limitations. First, while our quantitative data reveal strong correlations, our research design cannot capture any causal pathways linking electoral support to bureaucratic protection or regulatory forbearance. The illicit and opaque nature of these exchanges, which are marked by informal negotiations and quid pro quo arrangements, makes them difficult to observe directly. Large-N data can establish broad patterns, but the micro-foundations of criminal-political collusion require further work.

Second, although our analysis offers a detailed account of milícia expansion and its political enablers, it does not fully explore the long-term consequences of milícia governance. Key questions remain about the broader socio-political effects of milícia rule, including its impact on democratic accountability, civic trust, and economic development. Prior research suggests that criminal governance may hollow out formal institutions while reshaping local political norms; however, these dynamics warrant further empirical scrutiny (see, for instance, Feldmann and Luna 2023; Trudeau Reference Trudeau2024).

Third, although our analysis is grounded in the specific context of Rio de Janeiro, the generalizability of our framework to other urban centers in Brazil and Latin America warrants careful reflection. Rio’s distinctive geography, political history, and especially the criminal ecology characterized by competition between different criminal groups shape the dynamics we observe. Nonetheless, we argue that the core elements of our theoretical framework remain relevant in other contexts characterized by institutional weakness and fragmented state authority.

Our contribution is twofold. First, we propose a mechanism through which criminal actors engage in politics that goes beyond conventional accounts of clientelism or state capture. Rather than simply benefiting from contracts or impunity, milícias actively shape bureaucratic hierarchies, exploiting electoral incentives for state inaction to regulate local economies and extract rents. Second, we offer a theoretical synthesis that links the literature on criminal governance, institutional weakness, and electoral politics, thereby contributing to the growing body of work on how democratic institutions become instrumentalized by criminal actors.

While we hope to contribute to the literature on criminal(ized) politics, we identify potential avenues for further research on the subject. First, further research could help identify what kind of political parties, beyond the programmatic-pragmatic division, are likely to get entangled in transactions with illegal actors, and under what conditions (Nieto-Matiz and Skigin Reference Nieto-Matiz and Skigin2023). Second, more detailed in-depth work is needed to shed light on the role played by criminal actors in informal economies and their roles as guarantors of agreements (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993; Hummel Reference Hummel2017; Hummel Reference Hummel2018) and on how this role grants them political transit. Third, a deeper inquiry into the socio-economic effects of criminal governance could shed light on how long-term exposure to milícia rule shapes patterns of political participation.

In sum, this article highlights the paradoxical ways in which democratic institutions can be subverted from within. Rather than fostering accountability and rule of law, electoral competition in fragmented and under-institutionalized settings may incentivize politicians to align with criminal actors who can mobilize votes and manage local order. Understanding this dynamic is critical not only for diagnosing the challenges of criminal governance but also for informing institutional reforms aimed at insulating democratic processes from criminal capture. The case of Rio de Janeiro’s milícias thus offers a sobering illustration of how state-sponsored coercion gaps undermine democratic accountability while embedding organized crime within the very structures of political power.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2025.10026

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded by FGV-EAESP. We thank George Avelino, Ciro Biderman, Pedro Bruzzi, Gabriel Feltran, Bianca Freire-Medeiros, Alison Post, Eduardo de Oliveira Rodrigues, Scott Straus, and Jessie Trudeau for advice and feedback at various stages of this project. We are grateful for feedback from seminar participants at FGV-CEPESP and the GLOBALCAR Research Group. For research assistance, we thank Gabriela Brogim and Luisa Martinelli.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.