Introduction

“Let last year's Canada Day be our last,” wrote Molly Cross-Blanchard in a June 2021 article for The Tyee. Cross-Blanchard's call for an end to the celebration of Canada Day and its exaltation of the settler-colonial nation-state followed the May 27, Reference Cross-Blanchard2021, announcement from Chief Rosanne Casimir of the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc nation confirming the location of unmarked graves at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School containing the remains of 215 children. When the Lekwungen Traditional Dancers pulled out of the City of Victoria's Canada Day events to focus on community needs, then-Mayor Lisa Helps (2021) cancelled Victoria's celebrations, eliciting mixed reactions nationwide. Several Indigenous and settler communities followed suit, with announcements following from Penticton, BC, Rankin Inlet, NU, Wilmot, ON, and St. Albert, AB. Then, on June 24, Cowessess First Nation announced the location where the remains of 751 children were found at the former Marieval Residential School (Eneas, Reference Eneas2021). Idle No More organized rallies protesting Canada Day celebrations in major cities, and groups organized walks to honour Indigenous children who died at residential schools (APTN, 2021). Another wave of Canada Day cancellations followed across the country. In total, 126 communities issued statements cancelling Canada Day in 2021.

The stories we tell about ourselves as individuals and nations matter to our political relationships. The stories told through national celebrations are illustrative of how sovereignty, identity, and belonging are imagined; the same is true of the stories told about their cancellation. This article presents an analysis of statements issued by local governments and community organizations cancelling Canada Day in 2021. Informed by scholarly debates on the opportunities and limitations of reconciliation in the context of settler-colonialism, we ask: How do local governments and communities justify the policy of cancellation? For what purpose, to what end, and for whom is Canada Day cancelled? What kinds of stories do these statements tell?

We argue that local Canada Day cancellation statements in 2021 reflect dominant national narratives of liberal multiculturalism, residual logics of white nationalism, and the emergent, transformative political projects of Indigenous-defined reconciliation and resurgence (Williams, Reference Williams1977). Emphasizing dominant national narratives of Canadian benevolence, diversity, peace, and multiculturalism, statements frame cancellation as the Canadian thing to do. Paradoxically, the policy of cancelling Canada Day is justified through narratives associated with celebrating Canada Day. From a liberal multicultural perspective, residential schools are described as an exception to an otherwise peaceful history, and reconciliation is vaguely defined, presented as value or state of being that individuals can embrace as they reflect. At the same time, the statements reflect the residual logics of the post-Confederation era, when Dominion Day was an unabashed celebration of the British race (Brodie, Reference Brodie, Adamoski, Chunn and Menzes2002). This residual white nationalism is evident as national subjects assume governance over the appropriate limits of celebration and sorrow, prescribing a temporary moment of reflection before subjects can resume being Canadian as normal. The statements tend to speak to an imagined normative Canadian subject who makes a temporary exception when it comes to celebrating Confederation. In other words, this normative Canadian subject would not contend the idea that Confederation is worth celebrating—but for the confronting evidence of physical genocide and the immediate nature of Indigenous grief. Finally, the statements also evidence emergent political forces, including Indigenous articulations of transformative reconciliation, resistance to settler-colonialism, and expressions of sovereignty. These interventions signal the potential for a major shift in Canadian narratives and practices of national celebration in Canada.

We begin by providing crucial context regarding the events of 2021. Next, we synthesize literature on Canadian national celebrations, situating contemporary debates about Canada Day within historical and theoretical context, examining the dominant, residual, and emergent forces that shape policymaking around Canada Day. Third, we explain our methodological approach. Fourth, we present our findings on dominant, residual, and emergent narratives of Canada Day in 2021. Finally, we offer conclusions.

Context and Contributions

Quoted in the introduction, Cross-Blanchard's is one of many Indigenous voices critiquing the celebration of Confederation for obscuring settler-colonialism even as national narratives emphasize diversity, peace, and multicultural harmony (Ladner and Tait, Reference Ladner and Tait2017: 11). The movement to cancel Canada Day gained momentum in 2017 as the grassroots Indigenous decolonization movement Idle No More campaigned to unsettle celebrations of the sesquicentennial of Confederation or “Canada 150” through a National Day of Action on July 1st (Idle No More, 2017). In his contribution to Surviving Canada: Indigenous Peoples Celebrate 150 Years of Betrayal, David B. Macdonald (Reference MacDonald, Ladner and Tait2017) writes that celebrating Confederation requires Canadians to “forget many things about how the country was created” (157).

Indeed, Indigenous peoples were an “obstacle” in the way of John A. Macdonald's nation-building policy (Treaty Seven Elders et al., 1996: 197). The British North America Act (1867) conceived of “Indians and lands reserved for Indians” as objects of colonial governance, and the Indian Act (1876) consolidated legislation designed to regulate and control Indigenous peoples (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence2003). Following Confederation, the Canadian government engaged in treaty-making to “pacify resistance” and facilitate settlement (King, Reference King and Brodie2018: 115). Canada's execution of Louis Riel and the introduction of a scrip system dispossessed the Métis of land, whilst the pass system was used to coerce Indigenous parents into sending their children to residential schools (Anderson, Reference Andersen2014: 41; Venne, Reference Venne and Asch1997: 195).

In short, the period following Confederation, between 1869 and 1885, saw “the rise of a settler colonial regime on the northern plains” (Wildcat, Reference Wildcat2015: 398). Settler-colonialism describes the state's pursuit of territorial control and institutional power, accomplished through the destruction or assimilation of Indigenous societies and the suppression of Indigenous sovereignty (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2006). Though the late anthropologist Patrick Wolfe (Reference Wolfe2006) argues that settler-colonialism is “inherently eliminatory, but not invariably genocidal” (387), Matthew Wildcat (Reference Wildcat2015) argues elimination—a project to “destroy, contain, or modify Indigenous societies so that a settler society can build on Indigenous territories”—is genocidal (394). As Wildcat explains, disrupting people's traditional ways of life and their relationships to land has “a direct impact on that people's capacity to stay alive” (Reference Wildcat2015, 394). The Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Reference Wildcat2015) describes residential schools as a form of cultural genocide intent on eliminating Indigenous languages, laws, political systems, food systems, spiritual traditions, family ties, gender norms, and relationships to land—in short, acts other than physical violence that nevertheless seek to destroy a group.

To be clear, the TRC also documents examples of physical genocide and scholars affirm that the evidence documented by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission meets the criteria of genocide as defined by the United Nation's Genocide Convention (MacDonald, Reference MacDonald, Ladner and Tait2017: 163). Volume 4 of the TRC documents evidence of missing children and unmarked graves, and for survivors of residential schools, the news from Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc confirmed what they already knew—children died at residential schools at the hands of those who ran them. For many non-Indigenous Canadians, however, confirmation of unmarked graves and evidence of physical genocide prompted a long overdue “moment of reckoning” (Meissner, Reference Meissner2022).

This moment of reckoning coincided with the lead-up to Canada Day, when provincial governments were preparing to re-open after 2020's COVID-19 lockdowns. The City of Victoria was the first municipality to cancel Canada Day celebrations after Lekwungen groups confirmed that they would participate as usual (Helps, Reference Helps2021). In response, Premier of British Columbia John Horgan urged communities to continue their celebrations, arguing that National Indigenous Peoples’ Day “would be a more appropriate time for us to collectively focus on how we can redress the wrongs of the past” (Prasad, Reference Prasad2021). Nevertheless, several communities nationwide followed Victoria's example, citing the need to respect survivors and their communities. For example, the Rankin Inlet, NU volunteer fire department, who organize the annual Canada Day parade there, wrote:

The discovery of 215 Indigenous children's remains at the Kamloops Residential School is the tip of the iceberg that has brought widespread grief and anger to the surface across the country and has touched every member of our fire department. Until the Federal Government takes some serious action, we don't feel that now is the time to celebrate Canada. (Rankin Inlet Fire Department, 2021)

Going further, Keewaywin First Nation declared July 1st a day of mourning to “memorialize all the children and families who endured residential schools” (Kakekagumick et al., Reference Kakekagumick, Meekis, Mason, Kakegamic and Kakekagumick2021). These statements resist the aphasia or deliberate, “calculated forgetting” required to celebrate Confederation (Thompson, Reference Thompson, Anievas, Manchanda and Shilliam2014: 45). While Canadian public opinion was by no means consolidated in 2021, both allies and antagonists posed the question “should Canada cancel Canada Day?” in op-eds and on social media, such that the idea of cancelling Canada Day became, for the first time since Idle No More launched its campaign to unsettle celebrations in 2017, part of Canadian public discourse writ large.

As the next section illustrates, research on Canadian national celebrations typically emerges from fields like History (for example Hayday, Reference Hayday2010; Mann, Reference Mann2014), Canadian Studies (for example Mackey, Reference Mackey2005), and Sociology (for example, Leroux, Reference Leroux2010). This research brings the study of national celebrations into the field of Political Science, studying announcements as policy texts that provide insight into the changing governance of national identity and reconciliation. Beyond this, our research makes three main contributions. First, this research offers rich empirical evidence building on theories of settler-colonialism explaining how settler states seek to replace Indigenous societies while narrating legitimacy in ways that obscure colonial power. Second, this research provides insight into ways local communities—Indigenous and non-Indigenous, urban and rural, North and South—negotiate and challenge settler-colonial national discourses and policies in diverse ways. Whereas Canadian Political Science has typically studied Indigenous Peoples as problems to be solved, we aim to take up Kiera Ladner's (Reference Ladner2017) call to interrogate “the Canadian problem” by examining how settler-colonialism is negotiated and renegotiated in the field of heritage policy. Third, this study builds upon research in the field of Indigenous Studies on the tensions, contradictions, possibilities, and limitations of Indigenous and Canadian conceptions of reconciliation. Noting ways Indigenous—and some non-Indigenous—communities intervened in dominant narratives through transformative conceptions of reconciliation, we hold out hope for alternative ways of narrating political and national relationships in ways that can support material change.

Theorizing Canada Day

This section provides historical and theoretical context for contemporary discourses about Canada Day. Borrowing from the late Raymond Williams (Reference Williams1977), Janine Brodie (Reference Brodie, Harder and Patten2015) argues that contemporary events “defy singular authoritative narratives,” since the present is always shaped by dominant, residual, and emergent forces (30–31). Present debates over Canada Day are influenced by dominant national narratives, shaped by the state and national subjects, about the supposed generosity of Canadian liberal recognition politics (Coulthard, Reference Coulthard2014). At the same time, the residual ideologies of the post-Confederation era, in which the white national subject and “pioneer” embodied the ideal citizen of the Dominion (Brodie, Reference Brodie, Adamoski, Chunn and Menzes2002), continue to shape the boundaries of discourse about Canada Day and affirm assumptions of the nation as a “white possession” (Moreton-Robinson, Reference Moreton-Robinson2015: 10). Finally, emergent political forces focused on resurgence and reconciliation suggest alternative ways for narrating political relationships through—and, also, against—national days.

Dominant Discourses

In the present, Canada Day events tend to emphasize multiculturalism, reconciliation, and diversity, ideas rooted in the liberal idea of recognition. Glen Coulthard (Reference Coulthard2014) identifies a shift in the Canadian state's approach to the governance of Indigenous peoples from a double-pronged policy focused on elimination and assimilation to a mode of governance focused on the recognition of Indigenous cultural and political rights (4). The introduction of the language of recognition, Coulthard explains, was a strategic response to the emergence of a more forceful and active pan-Indigenous, anticolonial resistance movement following the introduction of the White Paper (4). As opposed to a departure from settler-colonialism, Audra Simpson (Reference Simpson2014) argues persuasively that the liberal framework of recognition is merely a “gentler” form of settler governance, “the least corporeally violent way of managing Indians and their difference, a multicultural solution to the settlers’ Indian problem” (20).

Whereas reconciliation has typically been used in post-conflict societies as a transitional justice tool, the Canadian government introduced the language of reconciliation in the absence of structural transition (Coulthard, Reference Coulthard2014: 121). The effect of using the transitional justice language of reconciliation in a nontransitional context is the “fabrication” of a colonial “past” separate from present oppression (121). Indeed, Mark Rifkin (Reference Rifkin2017) argues settler-colonialism has a temporal structure, marking time according to indicators of founding events and national progress. In Canada, this kind of temporal colonialism is evident in the celebration of Confederation, a practice that seeks to naturalize settler occupation and power and confine Indigenous peoples within these national historical parameters, obscuring their sovereignty since time immemorial (Rifkin Reference Rifkin2017, 13). Meanwhile, discourses of redress describe colonialism as a historical event and promise a better future, implying that colonial violence is an unfortunate step on a path towards national progress and unity (Simpson Reference Simpson2016).

Ultimately, Rachel yacaaʔał George (Reference George, Ladner and Tait2017) argues that the “emerging reconciliation paradigm” is a state-building project, including Indigenous peoples within the settler-colonial capitalist structure and seeking to foreclose emancipatory projects of self-determination (49–50). From this perspective, the state's reconciliation discourse is a form of “performative morality,” whereby Canada avoids “substantial structural change” in favour of hollow appeals to the recognition of cultural difference (George, Reference George, Ladner and Tait2017: 53). In this context, individuals and institutions tend to engage in “settler moves to innocence”—symbolic gestures of inclusion of Indigenous Peoples that fail to transform colonial power relations (Tuck and Yang, Reference Tuck and Wayne Yang2012: 3).

Sara Ahmed's (Reference Ahmed2014) study of Australia's “Sorry Books,” collections of messages composed by (mostly white) Australians to express remorse to the Stolen Generation, offers important insights for Canada. Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2014) theorizes that individual and collective expressions of national shame can, paradoxically, function as a source of national identity construction. By sharing in the process of atoning for the nation-state's violence, national subjects engage in a social process of identifying core national values such as multiculturalism and inclusion; meanwhile, through their expressions of remorse, they feel a distance from state violence, which is framed as contrary to core national values (108). Within a reconciliation paradigm, the practice of expressing remorse and sorrow is framed as “the right thing to do”; in this context, Ahmed argues, those who refuse to admit national shame become a secondary source of national shame (110). By this logic, if all Australians would express their remorse, the national image could be recuperated (112). In short, by feeling bad, Australians can feel good again. Importantly, as national subjects experience the process of identifying, condemning, and atoning for the nation's shameful past, they are simultaneously, by implication, recommitting their allegiance to the nation, and reaffirming their status as national subjects who have assumed some power to determine the national character (108–09). As we discuss below, Canadian statements cancelling Canada Day in 2021 evidence a similar process of recuperating the national image through expressions of shame by identifying Canada's core values, positioning residential schools as an aberration from those values, and looking forward to a better, more harmonious future. The implication is that by feeling bad, Canadians can feel good again.

Residual Ideologies

The process through which atonement for national violence becomes an expression of patriotism is rooted in what Aileen Moreton-Robinson (Reference Moreton-Robinson2015) calls the “white possessive,” the commonsense assumption among white people that they have a legitimate right to govern the nation. The white possessive, or the feeling among white settlers that “the right to be here” is self-evident, is not merely discursive or ideological—it is also “enabled by structural conditions” (Moreton-Robinson, Reference Moreton-Robinson2015: 18). The concept of the white possessive helps explain how settler-colonialism is a racialized structure. For Wolfe, “the primary motive for elimination is not race […] but access to territory” (Reference Wolfe2006: 388). Yet, he notes that settler-colonialism employs “the organizing grammar of race” (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2006: 387). In Canada, the white supremacist logics animating the Indian Act and the genocidal residential school system also underpinned post-Confederation immigration policies, which identified white people as a “hearty” race ready to take up the life of a pioneer, and exploit Canada's natural resources (Brodie, Reference Brodie, Adamoski, Chunn and Menzes2002: 47; Thobani, Reference Thobani2007: 90). Belief in “Aryan” superiority permeated both sides of the House of Commons in the post-Confederation moment; while Macdonald professed his belief in white supremacy, so did Liberal MP R.G. Macpherson, who argued that Canada could “never expect to maintain a high standard of nationality unless we kept the strain white” (quoted in Smith Reference Smith, Brodie and Trimble2003, 117).

The practice of celebrating Confederation originated in this context. “Dominion Day”—renamed Canada Day in 1982—was created in 1879 (Hayday, Reference Hayday2010: 289). Until the mid-twentieth century, English-speaking Canadians used Dominion Day to locate themselves as a “core part of a worldwide British race” (Mann, Reference Mann2014: 253). In this context, the state identified the loyal “Imperial Subject” as the recipient of citizenship rights and defined the ideal citizen against Indigenous peoples and nonwhite immigrants, who were framed as threats to the Dominion's white racial purity (Brodie, Reference Brodie, Adamoski, Chunn and Menzes2002; Thobani, Reference Thobani2007: 90). Up until the late 1960s, Indigenous peoples were included in Dominion Day celebrations only to the extent that they conformed to the state's assimilatory goals. For example, Father H. O'Connor of the St. Joseph's Mission residential school wrote to the federal government in 1965, petitioning for his students to play bagpipes at Dominion Day celebrations on Parliament Hill on the basis that they represented “the better side of our Indian people” (quoted in Hayday, Reference Hayday2010: 299).

By 1967, however, Canada was experimenting with an emerging multicultural identity. In the postwar context, successive federal governments pursued policies to construct a distinct national identity from Britain's and one resistant to American cultural dominance (Brodie, Reference Brodie, Adamoski, Chunn and Menzes2002: 49). The policy and discourse of multiculturalism served this purpose, meanwhile capturing demands from nonwhite immigrants for inclusion in the Canadian political and social story (Abu-Laban et al., Reference Abu-Laban, Gagnon, Tremblay, Abu-Laban, Gagnon and Tremblay2022: 6). The 1967 centennial and Expo ’67 provided a chance for Canada to share its emerging multicultural identity worldwide (Mackey, Reference Mackey2005: 72). Through “pedagogies of patriotism” Expo ’67 taught citizens about Canadian “cultural pluralism and tolerance” through songs, dances, and food (72). As opposed to a meaningful shift in colonial governance, however, Eva Mackey (Reference Mackey2005) argues that Expo ’67's emphasis on multiculturalism was a way to manage and contain difference.

Because multiculturalism as a policy and discourse defines culture as that which departs from white settler norms and implies that politics and culture can be easily separated, it tends to normalize whiteness and racial power structures and implicitly gives white people a mandate to tolerate, regulate, and govern nonwhite citizens, demarcating acceptable expressions of difference (Dhamoon, Reference Dhamoon2009; Thobani, Reference Thobani2007: 143). These critical perspectives on multiculturalism locate it in the same liberal approach to recognition that shapes state approaches to reconciliation—an approach that does little to address power structures or inequality (Dhamoon, Reference Dhamoon2009). In fact, studies of contemporary Canadian national celebrations emphasize that these commemorative events invoke colonial origin stories alongside narratives of diversity and difference, interpolating an “unmarked and yet normative” white identity (Mackey, Reference Mackey2005; Caldwell and Leroux, Reference Caldwell and Leroux2017; Leroux, Reference Leroux2010). For example, in her ethnographic research of local celebrations during 1992's “Canada 125” events, Mackey (Reference Mackey2005) identifies an emphasis on “Canadian-Canadian” identity, a form of national subjectivity that rejects the multiculturalism of diasporic hyphenated Canadian identities (145).

The residues of white supremacy are layered underneath present Canada Day narratives emphasizing positive feelings of togetherness, loyalty, pride, and happiness. Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2010) argues that subjects seek happiness in the nation so that they might also find belonging. In Canada, celebrating the nation, thereby imagining it as a source of happiness, requires obscuring its violent foundations. To do so, celebrations of Canada tend to reproduce colonial myths about the discovery of an “unknown” land, and peaceful settlement (Leroux, Reference Leroux2010). Such narratives affirm the “mythologized exceptionalism that constructs Canada as the good colonizer” (Ladner et al., Reference Ladner, Ace, Closen, Monkman, Abu-Laban, Gagnon and Tremblay2022: 248). The act of expressing happiness about the nation can become a social obligation or “happiness duty”—a “positive duty to speak of what is good” and a “negative duty not to speak of what is not good, not to speak from or out of unhappiness” (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2010, 158). In 2021, when Canadian settler-colonial violence was making headlines worldwide, it evidently became more challenging for Canadians to perform the happiness duty characteristic of July 1st. In this context, the dominant discourses of multiculturalism, diversity, and reconciliation were stripped away, revealing only the thick residues of white supremacist ideologies foundational to the residential school system. Nevertheless, as we illustrate, statements cancelling Canada Day sought to recuperate the nation as a source of happiness and pride.

Emergent Forces

Emergent articulations of transformative reconciliation and resurgence represent alternatives to the happiness duty and dominant state-centric discourses of reconciliation and multiculturalism, which tend to re-inscribe settler-colonialism. Among academics and communities invested in Indigenous self-determination and decolonization, there are, broadly, two perspectives on reconciliation. The first, described above, views reconciliation as providing a new narrative for state legitimacy and power over Indigenous peoples. Many scholars and communities convinced by this critique of reconciliation's limitations prefer the concept of resurgence, which describes “Indigenous peoples exercising powers of self-determination outside of state structures and paradigms” (Borrows and Tully, Reference Borrows, Tully, Asch, Borrows and Tully2018: 4). Definitions of resurgence are contested. John Borrows and James Tully (Reference Borrows, Tully, Asch, Borrows and Tully2018) describe resurgence as “reclaiming and reconnecting with traditional territories by means of Indigenous ways of knowing and being” (4). Resurgence is not synonymous with decolonization; rather, it describes actions that have decolonization as a goal.

Sheryl Lightfoot (Reference Lightfoot, Stevens and Michelsen2020) argues that the “resurgence school” is limiting because it relies on binaries of Indigenous peoples as either colonized or “authentic,” reduces state power to a totalizing force, and forecloses possibilities for Indigenous engagement with the state (156). Debate pivots on whether resurgence requires Indigenous communities to turn away from the state and settlers, or whether resurgence can be meaningfully linked with reconciliation as defined by Indigenous peoples (Borrows and Tully, Reference Borrows, Tully, Asch, Borrows and Tully2018: 5). While Snelgrove and Wildcat (Reference Snelgrove, Wildcat, Stark, Craft and Aikau2023) ultimately view reconciliation as “a unique moment of colonial reconfiguration,” they emphasize that reconciliation nevertheless opens strategic opportunities for those pursuing Indigenous self-determination (158). Moving beyond binaries that position reconciliation as either “good or bad,” Snelgrove and Wildcat argue that reconciliation is both a state-driven project focused on legitimizing Canadian colonial sovereignty, and a project arising from decades of Indigenous political action that has “forced a response within Canadian society and by the state” (158–9). By demanding the state and settler society confront Canadian violence against Indigenous peoples, Indigenous peoples have created a new political environment that can be used strategically (158).

Borrows and Tully (Reference Borrows, Tully, Asch, Borrows and Tully2018) argue that there is potential for a transformative reconciliation project if reconciliation is defined by Indigenous peoples and connected to Indigenous resurgence (5). Indigenous conceptions of reconciliation, unlike the Canadian state's depoliticized version identified above, envision a transformative political, social, legal, and cultural project (Ladner, Reference Ladner, Asch, Borrows and Tully2018). Emerging from diverse Indigenous knowledge that include laws guiding relations between humans and nonhumans, Indigenous-defined reconciliation seeks to affirm multiple sovereignties (Ladner, Reference Ladner, Asch, Borrows and Tully2018). Providing the conditions for Indigenous sovereignties to flourish, Ladner argues, requires Canadians to engage in “acts of remembrance” that disrupt its “mythologized exceptionalism”; in Ladner's words, “Canada needs to reconcile itself with the great historical myths and lies that form the legal and political bedrock of this nation” (Reference Ladner, Asch, Borrows and Tully2018, 248).

Indigenous peoples have long used Canadian national celebrations to identify and disrupt colonial narratives. For example, at Expo ’67 Indigenous peoples used the “Indians of Canada Pavilion” to subvert colonial and imperial fantasies, offering an Indigenous-led celebration of survivance (Griffith, Reference Griffith2015: 171). As such, by identifying Indigenous projects of resurgence and reconciliation as emergent forces, we do not mean to suggest that Indigenous resistance to settler-colonialism is new; rather, we contend that present articulations of Indigenous-defined, transformative reconciliation and resurgence are disrupting dominant narratives.

Method

Our argument is supported by a critical discourse analysis of statements cancelling Canada Day in 2021. Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is a qualitative approach used to demonstrate and critique the ways language structures power relations and resistance (Wodak, Reference Wodak, Meyer and Wodak2001: 2–3). Since CDA examines relationships between language, power, inequality, political struggle, and subjectivity, it is informed by theory and scholarly accounts of historical, political, cultural, and social contexts (Wodak Reference Wodak, Meyer and Wodak2001). We apply theoretical insights on settler-colonialism, reconciliation, and resurgence to interpret Canada Day cancellation announcements, which we understand as forms of discursive governance that shape, reproduce, and disrupt dominant ideas about national identity, subjectivity, and settler-colonialism (Brodie, Reference Brodie, Adamoski, Chunn and Menzes2002: 54).

We focus on cancellation announcements from local governments and community organizations because, while Canada Day is a national holiday, celebrations of Confederation have always been planned, executed, and experienced at local levels in diverse ways (see, for example, Cupido, Reference Cupido, Blake and Hayday2018). While the prime minister and his provincial and territorial counterparts weighed in on the debate in 2021, it was local governments and volunteer organizations who decided whether and how celebrations would go ahead. Our sample includes 132 statements issued by local governments and communities on the cancellation of Canada Day celebrations in 2021. Canada Day celebrations are organized variously by local governments, band councils, nonprofit organizations, volunteer groups, and private for-profit organizations; as such, the authors of the statements range from local politicians to individual volunteers to business organizations. For example, in Rankin Inlet, the local fire department traditionally organizes a parade, whereas the Downtown Business Improvement Association organizes Collingwood, Ontario's July 1st events. Our focus on the local level enables an examination of the ways settler-colonialism is reproduced locally (Starblanket and Stark Reference Starblanket, Stark, Asch, Borrows and Tully2018, 190). At the same time, as research in other settler-colonial contexts demonstrates, political actors at the local level are taking the lead in reforming practices of national celebration, signalling the need to trace whether similar patterns exist in Canada (see, for example, Busbridge Reference Busbridge2023).

To compile our sample, research assistants (RAs) used an open-access database compiled by Idle No More (INM) tracking Canada Day cancellation announcements as a starting point to locate primary texts, such as press releases and social media statements, so that we could examine announcements in their original, unmediated contexts. In six cases, RAs could not locate a primary source, or the primary source was only one or two lines. In these cases, we added to the sample news articles containing detailed statements from local leaders. Cross-referencing the INM list with local, regional, national, and international news reports tracking cancellation announcements Canada-wide, RAs verified the accuracy of the INM list. RAs archived the statements online. Because COVID-19 restrictions were still in place in May and June 2021, many communities had already planned to forgo July 1st celebrations. We eliminated from our sample any statements that justified cancellation statements due to COVID-19 only (for example, Kelowna, BC) and any duplicate statements (for example, the Durham Region issued a single statement for multiple towns). As provinces lifted health restrictions, several major cities, including Edmonton, Calgary, and Winnipeg, opted to go ahead with celebrations and fireworks. Cancelling was the exception, not the rule, in 2021. Our analysis is limited to an examination of cancellation announcements and does not include press releases or statements about rallies or marches organized by social movements or community groups. RAs searched for announcements for Canada Day events in 2022 to see whether any cancelling communities in 2021 carried that policy forward into the following year. While a few cities that did not cancel in 2021, such as Winnipeg, reformed their events in 2022, no settler communities that cancelled in 2021 cancelled again in 2022.

We added 57 statements from Indigenous governments—mostly First Nations band councils—which either cancelled their own Canada Day events or issued statements calling for cancellation. We understand that band councils, as creations of the Indian Act, are distinct from Indigenous governance systems; as such, we are mindful that the terminology we are using is contested. We classified communities with a predominantly Indigenous population (for example, Iqaluit) as Indigenous. Otherwise, we classified communities as settler communities. While our use of “settler” to describe predominantly non-Indigenous communities glosses over urban and off-reserve Indigenous presence, we note important differences worth capturing using this, albeit imperfect, Indigenous/settler binary. The term settler is also highly contested for the ways it can homogenize diverse groups with different relationships to colonial power. We use the term to refer to those invested in maintaining settler colonial structures (Wildcat, Reference Wildcat2015: 394–5). Table 1 provides a summary of the cases.

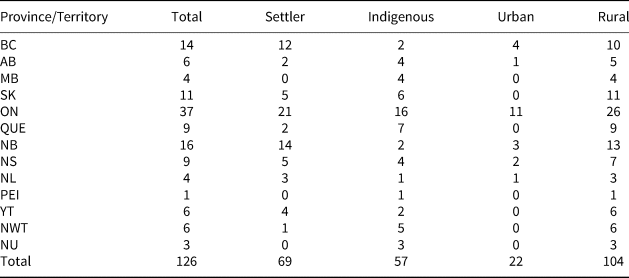

Table 1. Case Summary

*For the purposes of this table, “urban” includes census metropolitan areas and large and medium-sized population areas, as defined by Statistics Canada. “Rural” means rural and small population areas (under 30,000).

Note: Four statements are co-authored by Indigenous and settler governments. For the purposes of this study, they are identified as “Indigenous” statements.

Political scientists use CDA to identify and interpret the meanings produced through political discourses, which use specific grammar, words, frames, metaphors, and rhetorical devices to persuade audiences. As such, CDA requires “close, qualitative interpretations” and rich analyses to “identify the discursive patterns” that cannot be captured by content analyses that measure the frequency of particular words (Saurette and Gordon, Reference Saurette and Gordon2013, 162). Given CDA's critical orientation, scholars using this approach tend to shy away from prescriptions about how best to do it. That said, our approach resembles the steps described by Gill (Reference Gill, Bauer and Gaskell2000: 188–9). We began by reading the texts once with theory-driven questions in mind, including: for what purpose is Canada Day cancelled? How is cancellation justified, and for whom? How is reconciliation conceptualized? After a first reading, we identified three broad themes: the framing of cancellation as the Canadian thing to do, contrasting uses of the language of reconciliation, and competing Canadian and Indigenous descriptions of past, present, and future. Second, using NVivo software, we created coding categories to capture discussions of Canadian identity, reconciliation, and time (past, present, and future). We coded entire sentences and paragraphs to capture meanings in context. Third, we coded the coded texts; in the case of the theme of Canada, for example, we identified various ways Canadian national identity is affirmed: through emphases on Canadian virtues, through the location of violence in the past, through appeals to diversity and multiculturalism, and through promises of a brighter future, for example. As we examined the texts, we continually revisited theory to guide our coding strategies and developed a coding framework with specific descriptions of each code and sub-code. For the purposes of interpreting latent meanings and rhetorical strategies, we are less interested in capturing how often terms appear and more concerned with using theory to interpret various ways language is used. That said, it is illustrative to see how infrequently certain terms come up; so, we used NVivo's text search function to identify the frequency of certain terms (for example, “genocide” and “colonialism” and “reconciliation”).

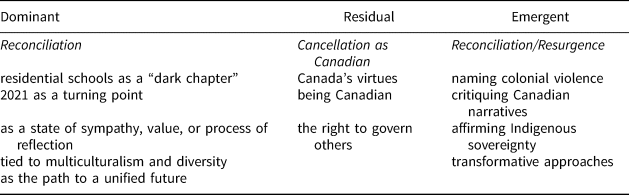

Our qualitative approach reflects calls for methodological pluralism in the study of Canadian politics (Everitt, Reference Everitt2021). Proceeding with skepticism about positivistic approaches that presume the reader and researcher are neutral, unbiased, and scientific, CDA does not necessarily aim for replicability and reliability, concepts associated with quantitative methods. The principle of reliability, for example, emphasizes the need for consistency in quantification of manifest content to illustrate that a finding is a true or objective account that any researcher using the same codebook would glean from analyzing the same texts. On the other hand, CDA is theory-driven, and casts suspicion on the idea that a true or objective account of language is possible (Bauer and Gaskell, Reference Bauer and Gaskell2000; Madill et al., Reference Madill, Jordan and Shirley2000). CDA is, ultimately, interpretative, and researchers are encouraged to participate in the project of meaning-making through analysis. Instead of reliability, scholars using CDA aim for dependability and trustworthiness, through, for example, providing access to the dataset, explaining deviant cases, and providing rich descriptions for readers to interpret and challenge themselves—the task to which we now turn (Bauer and Gaskell, Reference Bauer and Gaskell2000: 187–8). Table 2 provides a summary of our findings.

Table 2. Overview of Discourse Analysis Themes

Findings

Dominant Discourses: Reconciling Canada Day?

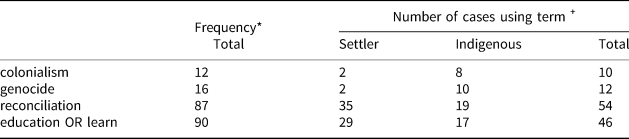

For the communities we studied, the decision to cancel Canada Day in 2021 was a response to the news of unmarked graves at former residential school sites containing the remains of Indigenous children. Those unaware that Indigenous children died in large numbers at residential schools were unable to avoid the facts, as the confirmation of physical evidence of unmarked graves made international headline news. As Table 3 illustrates, of 132 statements, 54 use the term reconciliation at least once. In total, the term reconciliation appears 86 times. Yet, curiously, the violence of residential schooling tends to go unnamed in the statements—particularly those from settler communities. The term genocide appears just 16 times, and statements from Indigenous leaders were more likely to use the term. Likewise, references to colonialism are scant, the term appearing in just 10 cases. Statements cancelling Canada Day in response to news of unmarked graves tended to avoid naming genocide and violence.

Table 3. Frequencies

* Includes total number of references. Searches include stem words (for example, colonial OR colonialism OR colonization)

+ The number of statements containing the term at least once.

When statements did identify—even if vaguely—that Canada has done harm to Indigenous peoples, this harm is situated squarely in the past. With some exceptions, settler statements frame the violence of residential schooling as a unique historical episode, dislocating residential schooling from ongoing settler-colonialism. For example, statements call for acknowledgment of “what has happened” (Town of New Glasgow, 2021) and identify the need to “right the wrongs of the past” (Hume, Reference Hume2021). Cancellation is made more comfortable, in some cases, by using the passive voice to avoid naming actors or institutions that perpetuated harm. For example, authors encourage readers to “acknowledge the actions that have taken place” (Stellarton, 2021) or learn about “the intergenerational trauma that has occurred” (District of Sechelt, 2021). Some statements encourage residents to “take time to reflect on Canada's history” with no mention of residential schools (Vassilaki, Reference Vassilaki2021).

The politics of redress, Simpson (Reference Simpson2016) argues, locates violence in the past so that settlers can move on, or perhaps, forget (439). The move to distance the nation-state from violence is evidenced by the identification of the summer of 2021 as a distinct historical event in and of itself. For example, the summer of 2021 is described as “a critical point in our history” and time to reflect (Saint John, Reference John2021). Canada Day 2021 is said to be serving an extraordinary purpose, as an “opportunity to reflect on the past, present, and future of this country” (Levanen, Reference Levanen2021) and a day to “pause, educate ourselves and reflect on darker times” (Ville Régionale de Cap-Acadie, 2021). This type of recognition through redress, in which one party affirms the other's existence and acknowledges harm done, tends to imply that the individual act of affirming and acknowledging—and in this case, pausing to reflect—is the extent of accountability required.

The fact that statements invoke the concept of reconciliation without naming colonial violence speaks to ways reconciliation can be utilized as a tool in a process of “colonial reconfiguration,” articulating a new relationship to Indigenous peoples without disrupting the status quo (Snelgrove and Wildcat, Reference Snelgrove, Wildcat, Stark, Craft and Aikau2023: 158). Though the theme of reconciliation pervades cancellation statements, few settler communities articulate a clear definition of reconciliation or identify specific commitments. Statements call on readers to “work together towards reconciliation” (Rothesay, 2021), pursue “reconciliation on a greater scale and deeper level” (Hume, Reference Hume2021), and engage in “quiet reflection in the spirit of truth and reconciliation” (City of Miramichi, 2021). Sometimes, qualifiers like “true” or “meaningful” are applied to the term (Town of New Glasgow, 2021). The use of qualifiers suggests an understanding that contemporary appeals to reconciliation can be superficial, but few statements offer specific commitments, suggesting things like “reflection” or “education” that are disconnected from political action. Variations of the terms “education” and “learning” appear more frequently than the term “reconciliation.” Yet, just 17 settler statements offer specific resources where readers can learn more.

When reconciliation is not framed as a form of individual growth, it is presented as a tool for Canadian nation-building, as in Hay River's declaration that “We will move forward as a stronger community and nation through recognition and reconciliation” (Jameson, Reference Jameson2021). Appeals to reconciliation in settler statements are ill-defined, but often imply that reconciliation is individual and emotional, accomplished by reflecting and keeping “reconciliation in our hearts, minds, and actions” (Henry, Reference Henry2021). In these statements, reconciliation is a state of sympathy or an expression of solidarity, and the kind of specific policy commitments that are required to shift relationships are largely absent. There are exceptions. Grand Bay-Westfield's statement (2021) commits to pass three motions: first, to adopt the Canadian Commission for UNESCO Coalition of Municipalities for Inclusion Declaration; second, to address six TRC Calls to Action directed at municipalities; and, third, “to use the historic spelling of Woolastook (Wolastoq) and Nerepis (Na.li'pits) on road signs.” Likewise, citing the need to move “beyond gestures” the City of Dawson Council (2021) promises to donate their Canada Day funds to the Yukon Government to support investigations at former residential schools.

Cancellation statements tie expressions of atonement to the language of multiculturalism and diversity, pointing to evidence of Canadian virtuousness even as physical evidence of missing and murdered children accumulates. For instance, the statement from Melville, Saskatchewan (2021), ties cancellation to diversity and assumptions of Canadian kindness:

We are a nation built on the strength and diversity of our people, the ability to help our neighbour and respect one another. We celebrate with strangers when our favourite team wins, we bow our heads when a funeral procession passes us by… [now] is a time to reflect and mourn with our Indigenous community.

In this statement, Canada's status as a colonizer is replaced with an expression of solidarity—the message is that Canada stands with, not against Indigenous Peoples. St. Albert Mayor Cathy Heron (Reference Heron2021) expresses remorse for past wrongs, while affirming Canadian national narratives of diversity, peace, and benevolence:

Obviously, there's many things to celebrate about Canada -- you know, our many peacekeeping missions around the world. We have a fantastic international reputation, you know our multiculturalism, our past achievements in science and poetry and sports, et cetera. So, I want you to celebrate this as a day to be proud of who we are; however, you know, we should also take some time to reflect on some of the darker chapters of Canadian history.

Likewise, the former Victoria mayor explains that the city's Canada Day celebration is usually an opportunity to “bring the community together for a diverse, multicultural celebration of our country” (Helps, Reference Helps2021). In the Town of Smithers, BC (2021), residents are prompted to “reflect on what it means to live together as a diverse community of Canadians.” Statements look to a not-so-far-off future when celebrations can resume.

Though July 1, 2021, is described as a moment of reflection or time to pause, statements reassure readers that celebrations will be resumed “when the time is right” (Churchill Mayor Mike Spence, quoted in CBC News 2021a). References to the future imply the ultimate objective of moving on and forgetting. The teleology is complex, portraying a future form of collective actualization made possible by past violence. In other words, the logic is that we had to do wrong to learn how to do right. Genocide becomes the implicit but necessary pretext for an idealized multicultural future (Simpson, Reference Simpson2016: 439–41). For example, Heron (Reference Heron2021) asserts that “Canadians will face the tragedy of the past, acknowledge the misdeeds of our institutions and move forward to a brighter future.” This future is presented as a single point in time that all Canadians are imagined to be collectively working towards, one that can culminate in a better, unified Canada. As such, even as they express sadness, the authors of these statements perform the happiness duty (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2010: 158). Paradoxically, national shame becomes as a pathway to national happiness (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2014a). Instead of a more accurate account of reconciliation as the result of Indigenous political action, these statements frame reconciliation as evidence of Canada's “moral progress” (Snelgrove and Wildcat, Reference Snelgrove, Wildcat, Stark, Craft and Aikau2023: 164). Through appeals to reconciliation that gloss over violence, obscure ongoing colonialism, and emphasize Canadian virtues, cancellation is depoliticized, morphing from a transformational practice into a settling one.

Residual Ideologies: Cancellation as the Canadian Thing to Do

Underlying Canadian appeals to reconciliation, diversity, and multiculturalism are the residues of Canada's explicitly white supremacist foundations, including the white possessive logic, which conceives of Indigenous peoples as objects of governance as opposed to self-determining subjects. In addition to affirming a normative national subject whose right it is to govern others, statements from settler communities attempted to depoliticize cancellation, detaching it from Indigenous resistance movements and framing the policy of cancellation as evidence of Canadian benevolence and tolerance. Just as Australian “Sorry Books” constructed a sense of national pride out of national shame (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2014a), settler statements framed cancellation as the Canadian thing to do.

Many statements from settler communities express their sorrow even as they affirm their commitment to Canada, wherein residential schools are imagined as “un-Canadian”—an exception to the rule. Cancellation announcements often qualify that the decision to cancel the celebrations does not diminish Canada's reputation for peace, freedom, diversity, and multiculturalism, affirming, for example, that: “there are many reasons to celebrate Canada's great successes” (Ville Régionale de Cap-Acadie, 2021); there are “many aspects of our nation to be proud of” (City of Pickering, 2021); and, that “we're fortunate to be Canadian and live here” (Jamal, Reference Jamal and Maral2021). The Collingwood Downtown Business Improvement Area (2021) expresses the need to “celebrate the strengths that unite us.” Meanwhile, St. Catharines Mayor Walter Sendzik urges Canadians to live out their values and “show our respect, understanding and empathy” (Green, Reference Green2021). These rhetorical appeals to the inherent virtues of “being Canadian” reinforce the idea that, ultimately, Canadians are good people. Paradoxically, cancelling Canada Day in recognition of colonial violence becomes further evidence of this inherent goodness. Cancellation is not just the right thing to do, it's the Canadian thing to do. By making cancellation Canadian and tying it to Canadian values, statements depoliticize the decision. The discursive production of Canadian-ness as something to be embraced and expressed through cancellation also implies acceptable national parameters for action. That is, those who name ongoing colonialism or engage in protest are implicitly constructed as outside of the national community (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2014b).

Alongside appeals to Canada's virtues are exhortations to consider that the meaning of being Canadian in a time of hardship is about coming together in communities of support. The City of Burnaby, for example, urges citizens “to use Canada Day as a time to reflect on what it means to be Canadian and […] consider where we want to go as a community” (Balzer, Reference Balzer2021). Just as celebrations of Canada tend to interpolate an “unmarked and yet normative” white identity (Mackey Reference Mackey2005, 145), Canada Day cancellation statements in 2021 imagine a normative Canadian subject and exhibit Canadian white possessive logic. Using the first-person plural pronoun “we” when identifying decision-makers, and the first-person possessive pronoun “our” to refer to Indigenous peoples, statements take for granted that the nation belongs to a group with the power to decide the appropriate course of action as Indigenous communities grieve. For example, Durham, Ontario Regional Chair and CEO, John Henry (Reference Henry2021) writes:

We have always prided ourselves on being one of the best countries in the world because we are open, honest, and welcoming. We need to uphold that reputation this Canada Day, and take this time to be open and honest with ourselves, and our historic and present-day relationship with the First Peoples of this land.

This statement recognizes Indigenous peoples as “First Peoples” but assigns to Canadians the power to determine the boundaries of belonging and inclusion.

These kinds of assertions of settler governance are contrasted with statements that describe the decision as the result of consultation and collaboration. Notably, a statement co-authored by Ft. Smith NWT Mayor Lynn Napier, Salt River First Nation Chief Poitras, Fort Smith Metis Council President Heron, and Smith's Landing First Nation Chief Cheezie describe their decision as the result of “traditional Indigenous cultural teachings,” assert a need for relationship building to “create new connections between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians,” and invoke the image of a circle as a basis for non-hierarchical relationships:

Our family, our community, our nation, our country, is a circle. A circle in which we stand together, where we are equal, where we can speak the truth, and where each of us steps forward with our gift, for the good of all life. (Napier et al., Reference Napier, Poitras, Heron and Cheezie2021)

While this statement, like others, affirms a singular national identity, its emphasis on non-hierarchical, reciprocal relationships is distinct and rooted in Indigenous teachings.

While a minority of non-Indigenous communities explained that their decisions were taken in consultation with Indigenous leaders, others emphasized that their decision was their own, and not a reaction to Indigenous peoples or social movements. The statement from Kitimat, BC (2021) asserts: “This course of action is not about cancelling Canada Day or the celebration of the many wonderful cultures and peoples that make up the fabric of our nation.” Victoria Mayor Helps (Reference Helps2021) distanced Victoria's decision from Indigenous leaders and social movements, explaining:

Victoria City Council didn't #CancelCanadaDay. We weren't responding to social media campaigns. And no one actually asked us to rethink what we had planned for July 1st.

Taking ownership of their decisions, these statements affirm a white possessive approach to governance and sidestep the opportunity for a deeper, more meaningful reflection on the relationship between Canada Day, reconciliation, and ongoing colonialism. Instead of a political intervention in step with movements like INM, cancellation becomes a depoliticized act of civil duty, through which Canadians are invited to embody supposedly core Canadian traits and values.

Emergent Forces: Since Time Immemorial

Indigenous communities intervene in these patterns, naming colonial violence, disrupting Canadian mythologies, affirming Indigenous sovereignty, and articulating transformative approaches to reconciliation and resurgence. For example, illustrating settler-colonialism's structural nature and eliminatory goals, Chief Sawan and the Loon River First Nation (2021) council write:

Make no mistake — this is genocide! Canada and its forefathers will be held responsible for enacting and implementing the genocide of our peoples. Society will know the truths of Canada's colonial processes that began in 1493 with the Papal Bulls including the Doctrine of Discovery, a Papal Bull that claims ownership of our Nehiyaw lands.

Indigenous communities are more likely to connect residential schooling and cancellation to ongoing settler-colonialism, explaining that “Canada continues its colonialist policies” (United Chiefs and Councils of Mnidoo Mnising, 2021). Whereas many settler statements only allude to colonial violence in vague terms as “a dark cloud that hangs over our community” (City of Melville, 2021), Indigenous statements describe residential schooling as a genocidal project. For example, Chief Mel Grandjam of Ft. McKay First Nation (Reference Grandjam2021) writes:

There was a clear and deliberate effort by leaders of Canada's government to eliminate Indigenous cultures, languages, and identity […] In [residential schools], Indigenous children were separated and isolated from their families, cultures, and languages. Countless children faced physical, sexual, and mental abuse. Many children never made it home. Generations of Indigenous peoples in this country have paid a human toll. The intergenerational trauma caused by the genocidal acts of residential schools is a reality for Indigenous peoples today — in communities without access to clean water or adequate health care and education, in memories repressed with substance use, in grief, and in unmarked graves of stolen children who were not allowed to go home. This reality should not make Canadians proud.

Indigenous statements disrupt Canadian narratives that isolate residential schooling as a deviation from an otherwise peaceful history. The Whitefish River First Nation (2021) describes residential schooling as “just one example of the many horrors we have endured under this country's colonial policies.”

As they name colonialism and genocide, Indigenous statements also challenge dominant Canadian national narratives emphasizing liberal multiculturalism. Pushing back against the idea that it is possible to separate Canadian virtues from colonial violence, Indigenous communities call Canada Day “a day of profound sadness” (United Chiefs and Councils of Mnidoo Mnising, 2021). Waterhen Lake First Nation (2021) leaders reject Canada Day, announcing that they will work on July 1st and “take [their] holiday on the 2nd for remembrance of the lost and stolen children that never made it home from the residential school system.” Ordering all Canadian flags to be taken down, Shamattawa First Nation Chief Eric Redhead promises that “Those flags […] will not go back up as long as I'm Chief” (CBC News 2021b). Indigenous leaders call upon Canadians to “reflect upon the false history of Canada that they have been taught for many years” (Wolastoqey Chiefs, 2021) and declare that Canada's “true history will be shared throughout the world” (Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2021). At a time when eyes and ears were attuned to the words and actions of Indigenous peoples and communities, these communities strategically intervene in prevailing Canadian narratives of a dark colonial past giving way to a bright Canadian future. As Snelgrove and Wildcat (Reference Snelgrove, Wildcat, Stark, Craft and Aikau2023) explain, reconciliation represents both a moment of colonial configuration and an opportunity for intervention.

Alongside challenges to Canadian national narratives are powerful assertions of Indigenous sovereignty that disrupt Canadian temporal sovereignty. The most profound example of this is offered by the Heiltsuk Tribal Council (2021) in their “Joint Leadership Resolution on Haíłzaqv Day Formally Known as Canada Day”:

Haíłzaqv history tells us we have been here in our territory since time immemorial. Archaeological evidence says that we have continuously live in our territory for at least the last 14,000 years and counting. In comparison, Canada is merely 154 years old.

Locating Canadian settler-colonial time inside of a much lengthier Haíłzaqv history, the authors disrupt and unsettle Canadian colonial temporality. In doing so, they also assert their sovereignty, citing their ancestors, who “left us a great legacy and a great responsibility” (Heiltsuk Tribal Council, 2021). “For generations,” they write:

the Haíłzaqv people have vigorously protected our culture, our language, our home territory, our future generations and our right to self-determination as sovereign peoples. (Heiltsuk Tribal Council 2021)

Their statement synthesizes the nation's past, present, and future as co-constituting, using the statement of cancellation to re-assert Haíłzaqv sovereignty. One Arrow First Nation's statement also articulates a temporal paradigm that holds the past, present, and future together to emphasize care for their ancestors and descendants:

We want to let the children, our relatives that didn't make it home know that we will remember them. We will be their voices. We will not let their deaths be in vain; they can rest peaceful now. This will never happen again to our children. My heart aches for the children that were in these residential schools. I keep the survivors and their families all in my prayers. (Sutherland Reference Sutherland2021)

Holding Indigenous past, present, and future generations together, these statements challenge settled ideas of Canada-time. By narrating Indigenous sovereignty irrespective of Canadian historical markers like Confederation, these statements disrupt seemingly settled notions of Canadian sovereignty and futurity.

Articulating sovereignty through Indigenous knowledge and outside of settler-state paradigms, these statements are expressions of resurgence and transformative reconciliation or “resurgence-reconciliation” (Borrows and Tully, Reference Borrows, Tully, Asch, Borrows and Tully2018: 5). Indigenous conceptions of resurgence-reconciliation describe a transformative project encompassing all aspects of relationships between Indigenous peoples, nonhumans, and settlers, enabling multiple sovereignties to flourish simultaneously (Ladner, Reference Ladner, Asch, Borrows and Tully2018). The Haíłzaqv Tribal Council (HTC) emphasizes the need for an “Indigenous defined ‘reconciliation’” that is also Indigenous-led, writing that, “in the era of reconciliation, the Haitzaqv have taken on the burden of leadership.” Affirming that a new relationship with Canada based on Indigenous-defined reconciliation “would give validity to the Crown,” the HTC assert the power to legitimize Canadian sovereignty, as opposed to seeking Canadian state recognition (Heiltsuk Tribal Council, 2021). Unlike Canadian statements that present reconciliation as a process of deepening Canadian national identity, this statement gives Indigenous peoples the power to determine whether Crown has fulfilled its obligations to Indigenous peoples. Likewise, Sawan (Reference Sawan2021) writes, “We recognize our Sovereignty and the relationship with the Imperial Crown. The state of Canda has no power or authority of our Peoples.”

Evidencing Indigenous conceptions of reconciliation or reconciliation-resurgence, Indigenous communities identify the need for political action. For example, Chief Andy Rickard (Reference Rickard2021) of Ketegaunseebee writes:

This national day of tragedy is a strong signal that transformative change is required across the nation. We will no longer accept hallow words of progress from government as their message is designed to pretend government is serious about taking concrete action.

A post on the Micmacs of Gesgapegiag Facebook page (Reference Rickard2021) rallies supporters to engage in direct action to slow traffic on highways, unsettling Canada Day by compelling Canadians to learn about residential schools:

Traffic will be delayed, we ask community members to come and show support by offering prayers, song. A sacred fire will be lit at the powwow grounds from 7:00am to 7:00pm, you are all welcome to join us by offering tobacco at the sacred fire.

Such actions cannot be understood simply as protest; rather, what is described here is a resurgent practice of Indigenous ceremony (Danyluk and MacDonald, Reference Danyluk and MacDonald2018). As we describe above, with a handful of exceptions offering alternatives to the status quo, settler statements of cancellation tend to depoliticize cancellation, emphasizing reflection over resistance or reform, implying that there is a narrow window of acceptable political action.

Conclusion

Proceeding with the assumption that the stories we tell about ourselves matter to political relationships, this article analyzes Canada Day cancellation statements from 2021, examining the stories these statements tell about Canada in a moment where the state's colonial violence is laid bare. We argue that these statements eschew a singular characterization, evidencing dominant discourses of liberal recognition and multiculturalism, residual yet powerful logics of white supremacy, and emergent movements for Indigenous resurgence and reconciliation. The settler governance of Canada Day—in this case the governance of the cancellation of Canada Day—utilizes a liberal framework of recognition, neutralizing Indigenous calls for Canada Day that emphasize transformative projects of reconciliation, decolonization, and resurgence. To perpetuate the structure of settler-colonialism, the state consistently reinvents its claims to legitimacy, as it contends with the persistence of Indigenous life and Indigenous political orders (Simpson, Reference Simpson2017: 22). As such, even when calls to cancel Canada Day reached critical-mass from within settler institutions, cancellation was grafted onto the settler nation-building project. Though settler sadness, shame, and sorrow could be mobilized discursively in service of reforming or cancelling Canada Day permanently, or for broader projects of Indigenous-defined reconciliation or decolonization, settler statements tend to limit the political possibilities of the moment by tying these feelings to a vague and individualized concept of reconciliation, linking that with being Canadian, and envisioning a settled, harmonious future after the feelings have dissipated. The movement to cancel Canada Day—created by Idle No More—was, in many cases, co-opted and mutated into a performance of Canadian patriotism projecting the image of a harmonious, united settler-Canadian future, in which everyone moves on. The shallow nature of settler expressions of solidarity via cancellation in 2021 are confirmed by our finding that all the settler communities that cancelled their events in 2021 resumed their celebrations in one form or another in 2022.

Some municipal governments have reformed Canada Day in partnership with Indigenous nations. For example, in Winnipeg, at “The Forks,” the intersection of the Assiniboine and Red rivers and a traditional meeting place, organizers planned “A New Day” on July 1, 2022, a result of “Indigenous-led discussions with community members, newcomers, and youth” (CBC News 2022). Promising a “reimagining” of Canada Day, the 2022 event included: a morning ceremony; Nehiyaw, 2SLGBTQ+, Metis, and Oji-Cree pipe ceremonies, a gathering space for quiet reflection, powwow dancers and singers, an oral history tour, and Inuit ceremonies and throat singers (The Forks, 2022). By 2023, however, Canada Day was back as usual in Winnipeg. Thunder Bay introduced reforms to Canada Day events in 2022 guided by the municipal Indigenous Relations Office and Anishinaabe Elders Council to “recognize that Canada Day means something different to everyone, and to move forward in an inclusive, thoughtful, and meaningful way towards Reconciliation” (Thunder Bay, 2022). In 2022, the syíyaya reconciliation movement, working with the District of Sechelt and the shíshálh Nation, introduced syíyaya days. Featuring “ten days of awareness building, learning and cultural celebration,” syíyaya days begins on National Indigenous Peoples Day and ends with “an inclusive Canada Day, celebrating Canada while also recognizing our colonial history and celebrating the cultures of First Peoples of this land” (syíyaya Reconciliation Movement, 2023). Future research should examine whether such projects offer frameworks for reforming national days in ways that are responsive to Indigenous conceptions of reconciliation and challenge colonial national narratives.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Cassandra Monahan and Rohina Saidy for their research assistance, as well as Dr. Rita Dhamoon and Dr. Corey Snelgrove for their feedback on early drafts of this article. We are grateful, also, to the anonymous reviewers for their feedback.