Introduction

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, video games became a vital alternative form of entertainment for people facing restrictions on mobility and personal contacts. The diverse effects of video games on players’ real-life experiences during this period attracted significant academic interest, as demonstrated by a 24-chapter edited volume (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson, Fay, Fernandez-Vara, Pinckard and Sharp2021) that comprehensively explores these effects. Within this volume, Daneels (Reference Daneels, Davidson, Fay, Fernandez-Vara, Pinckard and Sharp2021) argues that video games provide not only hedonic and eudaimonic experiences, but also emotional support and opportunities for meaningful social connection during periods of social distancing. Furthermore, Kocik et al. (Reference Kocik, Dalton, Forbush, Kersting, Malagon, Olson, O’Ceallaigh, Davidson, Fay, Fernandez-Vara, Pinckard and Sharp2021) examine the sense of co-presence among players, which can emerge even when individuals play at different times or from geographically distant locations, through shared emotional responses within the game. These findings suggest that video games can provide psychological resilience and promote social cohesion during periods of social distancing. However, cases such as the one examined in this paper, in which players of video games simulate real-world social distancing situations and thereby potentially support social distancing policies, have yet to receive detailed academic investigation. Such games may heighten people’s sensitivity or stimulate critical reflection on the status quo.

The implementation of social distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the subject of extensive cross-country analysis. In the early stages, Japan faced global criticism for its handling of a cruise ship outbreak (Nakazawa et al. Reference Nakazawa, Ino and Akabayashi2020). However, it later garnered rather positive attention for maintaining a low infection rate without imposing strict lockdowns or harsh penalties, relying instead on voluntary compliance and relatively lenient policies (Yan et al. Reference Yan, Zhang, Long, Zhu and Chen2020; Nishikawa Reference Nishikawa, Hawksley and Georgeou2024). The government repeatedly requested that people refrain from going out (Yan et al. Reference Yan, Zhang, Long, Zhu and Chen2020). This approach led to behavioral changes comparable to those under lockdowns, which effectively slowed transmission (Chung and Chan Reference Chung and Chan2021; Watanabe and Yabu Reference Watanabe and Yabu2021).

Scholars have attributed Japan’s effective implementation of social distancing policies to various factors, especially an impactful slogan that originates from political discourse. The slogan “Three Cs” (san-mitsu in Japanese), referring to three types of social contact density—closed spaces (mippei), crowded places (misshū), and close-contact settings (missetsu)—has gained attention for its role in guiding and educating the public (Yan et al. Reference Yan, Zhang, Long, Zhu and Chen2020; Allgayer and Kanemoto Reference Allgayer and Kanemoto2021; Okada Reference Okada, Comfort and Rhodes2022). “Mitsu desu!” (“You are too close!”) is a phrase used in a concrete situation to indicate that one of the Three Cs (closed spaces, crowded places, or close-contact settings) is occurring. The phrase also influenced pop culture, leading to a boom in the “Mitsu Desu” video game genre, which was directly inspired by the phrase and featured a politician who disseminated it nationwide.

Yuriko Koike, the first female governor of Tokyo, played a key role in promoting the Three Cs slogan on a national level (Allgayer and Kanemoto Reference Allgayer and Kanemoto2021; Borovoy Reference Borovoy2022; Okada Reference Okada, Comfort and Rhodes2022). On March 25, 2020, as shown in Figure 1 (HuffPost 2020), Governor Koike held out her hand and said, “Mitsu desu!” to prevent reporters from coming closer. She likely used the phrase to warn against missetsu (close-contact settings), one of the Three Cs. Experts have noted that her use of the phrase “Mitsu desu” in this scene was highly effective in spreading the slogan (Jiji Tsūshin Reference Tsūshin2020). Although the Three Cs slogan was originally introduced by the central government, Koike became the key figure in spreading it, as evidenced by her receiving an award when the slogan was selected as the Buzzword of the Year (Bunshun Online 2020). By highlighting her accomplishments during her second term, especially her COVID-19 measures, she garnered more than 2.9 million votes and secured a third term in the July 2024 election (BBC 2024). Her striking media presence during the pandemic, especially her memorable use of the “Mitsu desu” phrase, not only boosted her lasting popularity, but also inspired memes and parodies and triggered a boom in a video game genre known as the “Mitsu Desu” game, which further contributed to the slogan’s dissemination.

The boom of the Mitsu Desu game has attracted scholarly attention from the perspectives of risk and public health management as an example of pop culture’s role in facilitating informal social control and influencing public behavior (Borovoy Reference Borovoy2022; Okada Reference Okada, Comfort and Rhodes2022). Game scholar Navarro-Remesal (Reference Navarro-Remesal, Frangville, Kellner and Ponjaert2024) also takes up the game as an example of satirical video games featuring Japanese politicians as protagonists. However, he still considers its boom largely nonpolitical because it failed to stimulate political debate. Therefore, drawing on other recent research on video games created in Japan, this paper focuses on the connection between the boom of the Mitsu Desu game and social distancing policies that has not been examined in detail.

This article addresses the following questions to identify the factors that led to the Mitsu Desu game becoming a social phenomenon in 2020 and supporting the implementation of social distancing policies: Which design elements attracted people? How did players and other viewers interpret in-game actions in relation to real-world social distancing, especially whether these interpretations include manifestation of critical reflection on social distancing policies or changes in real-world behavior? And what roles did both new and traditional media play in expanding the boom? I argue that the game’s widespread reception, driven by a powerful synergy between new and conventional media, played a supportive role in implementing social distancing policies by heightening awareness and facilitating behavior changes.

The origins of the Mitsu Desu game genre can be traced back to Japan’s first state of emergency. When it was declared by the government at the national level between April 16 and May 25, 2020, a game engine platform held a contest with the theme “mitsu” (meaning “crowded” or “close” in Japanese). Both amateur and professional creators submitted 353 games to UnityRoom as part of the contest (UnityRoom 2020). They also released games independently on their own websites.

This paper focuses on the following four key examples among the games uploaded to UnityRoom and individual websites: (1) a two-dimensional (2D) browser game developed by Chicken GUNJŌ (@miseromisero), who was an economics student, (2) a 3D version developed by Mose SAKASHITA (@motulo), who was a PhD student at Cornell University at the time, (3) a rhythm game titled Mitsu Desu Beat Street developed by the indie creator team MARUDICE (@marudice), and (4) an endless runner titled Avoid! Three Cs!! (Sakero! Sanmitsu!! in Japanese) developed by KYS/KIYOSU (@kiyosu775), who was then a student at the University of Tokyo and is now a PhD student at Princeton University. All of these games were browser based and required no installation, which contributed to their wide accessibility and rapid dissemination.Footnote 1

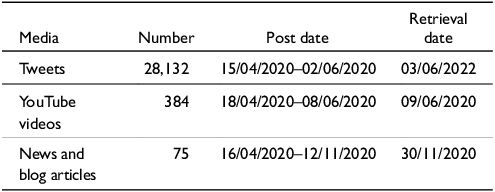

This paper analyzes the Mitsu Desu game phenomenon, using Japanese-language data collected mainly from Twitter, UnityRoom, and YouTube. Table 1 provides an overview of the primary data for this article, extracted using the keyword “mitsudesu + game” (密です + ゲーム) or “mitsudesugame” (密ですゲーム). The specific data used and their extraction methods are detailed in the relevant analytical sections.

Table 1. Primary data retrieved for analyzing the Mitsu Desu game and its boom

To thoroughly analyze the boom of the Mitsu Desu game, the following sections examine three aspects. First, they analyze the design elements that attracted many users and examine the potential of these elements to heighten awareness and facilitate changes in real-world behavior. Second, they examine the ways in which players and viewers interpret in-game actions in relation to real-world social distancing situations, specifically investigating manifestations of heightened sensitivity and critical reflection as defined by Whaley (Reference Whaley2023) and Roth (Reference Roth2018). Third, they investigate the media dissemination that helped transform the game into a social phenomenon.

Design elements of the Mitsu Desu game

Within the Mitsu Desu game genre, four distinct types have gained wide circulation through both new and traditional media. By drawing in a large audience, promoting repeated gameplay, and thereby heightening awareness and facilitating changes in real-world behavior, as detailed in subsequent sections, these games supported the implementation of social distancing policies. This section provides an overview of their key design elements, which attracted many players and encouraged repeated play.

Data

This article specifically focuses on four different games belonging to the Mitsu Desu game genre to explore their design elements: (1) the original 2D game (Mitsu Desu!); (2) the 3D game (Mitsu Desu 3D); (3) the rhythm game (Mitsu Desu Beat Street); and (4) the endless running game, Avoid! Three Cs!! (Sakero! Sanmitsu!!). The selection is based on the differences in game types, the substantial number of gameplay videos uploaded on YouTube, and the abundance of tweets referencing these games. All four games could be played directly in the browser, without downloading or installing any software. This also made them easily accessible for people who may not typically engage with video games.

Analysis

Apart from the “endless running game,” in which players run as far as possible, avoiding obstacles, the three other games share a common rule: a protagonist resembling the Tokyo governor to disperse the mob shouts “Mitsu desu!” and earns points. While the “rhythm game” is created by a team of four indie game creators, the three others were developed by graduate and undergraduate students in 4–7 days.

The four games include elements that not only encourage long-term, repetitive play, but also heighten sensitivity and facilitate behavior changes. The 3D game features a unique structure, prompting players to repeat gameplay by earning gold coins through each stage and using them to purchase 45 different items, such as hats and weapons. The games differ not only in music but also in the protagonist’s voice source—Governor Koike’s voice from news videos, a voice actor, or synthetic voice. The mechanic, in which pressing a button makes the protagonist shout “Mitsu desu!” and disperses a crowd, is shared by the three games except for the endless running game. It provides players with a sense of pleasure each time they press the button, thereby encouraging repeated play. The protagonist’s repeated shouting of “Mitsu desu” is also important for the game’s potential to heighten players’ sensitivity to real crowded situations and to prompt changes in their real-world behavior, such as shouting “Mitsu desu!” in those situations. Visuals, particularly whether they use 2D manga/pixel art or 3D characters, also vary significantly, as shown in Figure 2. This diversity also allows the Mitsu Desu games to cater to different player preferences, such as visual style, helping to establish the series as a distinct genre.

Figure 2: Screenshots from gameplay videos of four different Mitsu Desu games.

Note: Top left: 2D game, top right: 3D game; bottom left: rhythm game, bottom right: endless running game.

In the following, this article discusses design elements in each of the four games that could enhance people’s awareness and promote changes in real-world behavior and thereby support the implementation of social distancing policies.

The original 2D game (Mitsu Desu)

Compared with the other three games, this game enhances players’ awareness of the recommended two-meter social distance more effectively by indicating it with a green circle. Players click to move crowds that gather around the protagonist and block the protagonist’s path. In contrast to the other three games, both the protagonist and people in the crowds wear masks. As the latter approach within the 2-m range, the masks become soiled, changing from white to black. The visualization, in which masks turn black upon contact with anyone within a 2-m range, may also heighten players’ awareness of crowded situations and the risk of infection. At the beginning of the game, the player starts with five masks, or five life points. If a mob enters the 2-m range, the player loses a mask or a life point. This effectively conveys that people should not continue wearing old, soiled masks, which may also enhance their sense of hygiene. Occasionally, a character resembling Prime Minister Abe appears to distribute two masks, as shown in the top left picture of Figure 2. If the player approaches the character and collects two masks, two life points are restored. This setup also encourages obtaining clean masks rather than soiled ones. Thus, the visualization of the 2-m social distancing circle and the mask mechanic in the game may heighten players’ sensitivity to this distance in real life and encourage behavior changes.

The 3D game (Mitsu Desu 3D)

Insofar as the 3D game allows the protagonist to fly to detect crowded groups from the sky and occasionally shoot them, players can experience the radical exercise of power virtually. Players have three different kinds of crowds—engaged in chatting, exercising, and jogging in groups of four—as targets to disperse as quickly as possible. Since the first update in September 2020, a radar has also been available to detect crowded groups. The introduction of this radar may have further heightened players’ sensitivity to crowds. In contrast to the 2D game, mobs in this game do not wear masks, although the protagonist does. The risk of infection outdoors is relatively low. Nevertheless, the protagonist actively seeks out mobs outdoors, blowing them away and dispersing them. This strict stance toward outdoor infections in the game world may heighten awareness of infection risks in the real world. The creator utilized assets inspired by Manhattan, yet the landscape partially resembles Japanese office districts. This might enhance players’ sense of simulating real-life situations. This game, unlike the 2D game, requires players to sharpen not only their visual but also auditory senses to identify the location of mobs. In particular, the voices of chatting groups become crucial clues for finding mobs. This might have also made players sensitive to such voices in real life. Thus, heightening senses and adopting a strict attitude toward crowded groups in this game could potentially contribute to implementing social distancing policies.

The rhythm game (Mitsu Desu Beat Street)

In contrast to the other three games, the rhythm game emphasizes the distinction between the Three Cs (closed spaces, crowded places, close-contact settings), much as politicians and experts were promoting awareness of that distinction. To earn points, players must disperse three different types of crowded groups by pressing three different keys (C, Z, X) with precise timing: (1) two people in a closed phone booth; (2) a crowded family of four on the street; and (3) two people sharing a table. In this game, players walk or run through the street with the music. The design might foster a strong sense of simulating real-life movement, as it makes players feel as though they were actually walking or running in the real world. As shown in Figure 2, the protagonist’s illustration features a cute manga style. However, this game adopts a stricter stance on social distancing compared with other games, as it assumes 2–3 people equate to a crowd. For example, the 3D game is designed to treat groups of four or more people as crowds that should be dispersed. By taking such a strict approach—defining even two or three people as a crowd—the rhythm game reinforces the political slogan and could facilitate changes in real-world behavior necessary for the implementation of social distancing policies.

The endless running game (Avoid! Three Cs!!)

This game distinguishes itself from the other three games through its first-person perspective, focusing on actions to wear and discard soiled masks, and the satirical use of an illustration of Governor Koike’s face. Players must navigate through a theoretically endless white corridor by moving forward, using the right and left arrow keys to avoid randomly placed cubes featuring the portrait of Tokyo Governor Koike. Players start with two face masks or life points. Unlike the other three games, players do not disperse mobs, which may partly explain its lower popularity. Players can continue even after colliding with a cube by discarding soiled masks and wearing fresh masks using the upper arrow key. The surreal corridor setting may weaken the sense of simulating real situations, yet the prominently featured masks, which occupy nearly one-fifth of the gameplay screen, likely contributed to a heightened awareness of mask wearing in the real world. Because players must avoid obstacles to keep their mask clean, the game may have enhanced awareness of maintaining distance and mask hygiene without repeating the crowd dispersal mechanic.

Although the endless running game is not particularly addictive, the four types of Mitsu Desu games attracted many players through different design elements, as shown in this section. Moreover, by using Governor Koike as a motif, they enhanced her presence, made her a more familiar figure to the public, increased her popularity, and simultaneously contributed to the dissemination of the Three Cs political slogan.

Building on this analysis of the Mitsu Desu game elements and their possible effects, this paper now turns to whether these elements may have fostered critical reflection and changed real-world behavior. This transition allows for a more precise interpretation of the Mitsu Desu games’ influence by examining qualitative data, particularly tweets, in relation to the game’s mechanics and visual design.

Reflection and changes in real-world behavior through gameplay

This section adopts a perspective derived from research on Japanese video games created before the pandemic, which argues that video games allow players to interpret game actions in relation to the real world and produce two effects: reflection and changes in real-world behavior. Reflection, in Martin Roth’s conceptualization, refers to gameplay’s potential to prompt critical self-reflection on real-world issues and to encourage imagining alternatives to the status quo (Roth Reference Roth2018: 2–3, 6, 14, 50). For example, Roth shows that games set in worlds dominated by bureaucracy and violence can lead players to reflect critically on their real-world situations (Roth Reference Roth2018: 149–72).

Changes in real-world behavior, according to the framework of Ben Whaley, concern heightened sensitivity and engagement with real-world situations, both of which are triggered by gameplay (Whaley Reference Whaley2023: 12, 16–17, 23). Whaley emphasizes that gameplay allows players to simulate real-world, including extraordinary, situations. He argues that video games with settings resembling real-world social contexts can enhance awareness and promote behavioral change. For instance, such games can give hikikomori youth opportunities to simulate social interactions, potentially helping them go outside and meet people (Whaley Reference Whaley2023: 104–29). Disaster survival games can not only simulate future disasters, but also help players process past traumatic events such as the Fukushima nuclear disaster (Whaley Reference Whaley2023: 48–72). He also suggests that moral systems in games may heighten awareness and prompt players to reject dominant political narratives in the real world (Whaley Reference Whaley2023: 67, 70).

Building on these previous studies, this section examines the case of the Mitsu Desu game, seeking evidence of critical reflection and real-world behavioral changes among players and viewers. The analysis also investigates how these behavioral changes manifested in heightened sensitivity and enhanced awareness of real-world crowds and social distancing situations.

Data

To examine the Mitsu Desu game’s potential for reflection and changes in real-world behavior, this research qualitatively analyzed 200 tweets posted between April 16, 2020, when the original 2D game was released, and June 23, 2023, which was the last date on which tweets discussing players’ and viewers’ impressions and interpretations of the game in relation to real-world situations were posted. Tweets that did not concern players’ or other viewers’ impressions or interpretations of the Mitsu Desu game were excluded through manual coding.

The corpus of 200 tweets consists of the following three parts: (1) 17 tweets identified with all three Japanese words “Mitsu desu,” “gēmu” (game), and “genjitsu” (reality); (2) 163 tweets identified with the three Japanese words “Mitsu desu,” “gēmu,” and “riaru” (real); and (3) 20 tweets identified with the three Japanese words “Mitsu desu,” “gēmu,” and “te” (hand). The search terms “riaru” and “genjitsu” were selected to detect reports concerning players’ and other viewers’ reflection on real-world situations, and changes in real-world behavior, which Roth (Reference Roth2018) and Whaley (Reference Whaley2023) conceptualize. The search word “hand” (te) was selected to specifically identify reports related to the game’s most iconic gesture, the protagonist’s crowd-dispersing hand movement, to examine players’ and viewers’ changes in external, real-world behavior, which Whaley (Reference Whaley2023) focuses on. Most of the 200 tweets refer to the Mitsu Desu game without clearly specifying which version they mean, and they generally talk about the game in which the protagonist can immediately disperse crowds.

Analysis

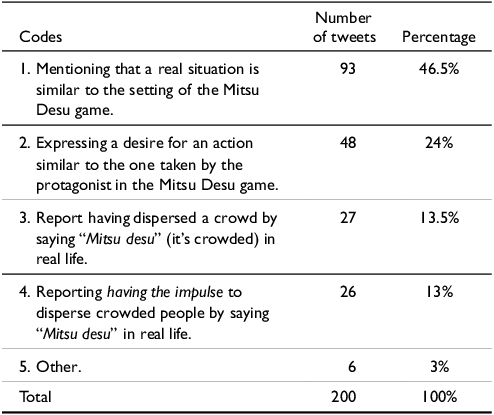

A qualitative analysis of 200 tweets posted by players suggests that the Mitsu Desu game induced behavior changes among players and other viewers, characterized by heightened sensitivity and awareness of real-world crowds and social distancing. When encountering crowds in urban areas, in news footage, or in photographs, they often reported feeling a connection to the game world or expressed a wish for authorities to respond in ways reminiscent of the game. The game’s influence appears to reinforce official government rhetoric on social distancing, rather than encourage resistance. This section provides specific examples of heightened sensitivity and changes in real-world behavior on the basis of coding of the 200 tweets presented in Table 2. The tweets fall into four categories, each representing either a change in sensorial perception or desires and actions resulting from that change. The tweets falling into the following four categories are statements about perceptual changes or about desires or actions that arose as a result of those changes.

Table 2. Results of coding for 200 tweets detected by the words “Mitsu desu,” “game,” “real,” “reality,” and “hand”

Just under half (46.5%) of tweets in which players related the game world to the real world were classified under code 1, “mentioning that a real situation is similar to the setting of the Mitsu Desu game.” The authors of these tweets were sensitive to crowds depicted in towns, news footage, or photographs. When encountering crowds, they tended to associate the scenes with the game world. The association between real-world crowds and the game world is likely triggered by visual cues in the 2D game, such as the green circle indicating the recommended 2-m social distance. The visualization of this circle may prompt players to imagine similar boundaries in real-world settings, as discussed in the Design Elements section. Similarly, the 3D game’s urban landscape, modeled on Manhattan and partially resembling Japanese office districts, appears to increase sensitivity to real-world crowd contexts. Moreover, when viewing news about mass events and patrols aimed at dispersing crowds, players reported feeling as if they were in the game world. This sensation seems to be intensified by the 3D game’s design, which allowed the protagonist to patrol by running or flying overhead, identify crowded groups, and occasionally shoot at them. Such settings provide a virtual experience of superhuman control over crowds and convey a strict stance toward outdoor infections. As explained earlier in the Design Elements section, these experiences appear to heighten players’ awareness of infection risks in real-world settings.

The tweets classified under code 1 often react positively to reports related to social distancing policies, especially those involving police enforcement. Among the 14 tweets classified under code 1 that cite news articles, the following are representative examples. One tweet reacts to a report about police checking on people drinking on the streets, saying, “It’s like a real-life Mitsu Desu game, lol” (リアル密ですゲームじゃん笑) (no. 25, posted April 23, 2020). Another tweet responds to news about police patrolling a park by saying, “The police officers are patrolling the park, playing a real-life Mitsu Desu game” (警察の方が公園を巡回していてリアル「密です」ゲームやってる) (no. 125, posted April 25, 2020).

These tweets, which highlight a perceived similarity between the Mitsu Desu game’s setting and real-world situations, can be interpreted as instances in which players use the game as a humorous cultural reference. This interpretation is supported by the frequent presence of laughter, emoticons, or expressions such as “lol” (e.g., in example no. 25), indicating that the game served as a lighthearted means of coping with the challenges of social distancing.

The tweets classified under code 1 can provide insights into whether the game influenced people’s stances on real-world issues or whether it supported resistance to official, dominant narratives. One tweet, for example, highlights the Mitsu Desu game as a simulation of extraordinary scenarios and notes its potential to raise public awareness: “The Mitsu Desu game might be useful for raising public awareness if it simulates crowding in realistic scenarios” (密ですゲーム、現実に即したシチュエーションで密を作っておくと啓発に使えそうなんだよな) (no. 4, posted April 23, 2021). Roth (Reference Roth2018) argues that video games have the potential to stimulate the imagination of alternative political futures. However, this tweet and the other code 1 tweets provide no evidence that the Mitsu Desu game fulfilled this potential. The stances of most tweet authors align with that of the game’s protagonist—Tokyo Governor Koike, who led the implementation of social distancing policies in Tokyo. One tweet even declares, “The Yuriko inside me is getting restless! Let’s play Mitsu Desu game [emoji depicting a smiling face with open mouth]” (わたしの中の百合子が騒いでいる!さ、密ですゲームやろやろ ![]() ) (no. 196, posted on April 21, 2020). This tweet largely reinforces the status quo and provides no evidence of critical reflection.

) (no. 196, posted on April 21, 2020). This tweet largely reinforces the status quo and provides no evidence of critical reflection.

The second largest number of tweets was classified into code 2, “expressing a desire for an action similar to the one taken by the protagonist in the Mitsu Desu game.” These tweets convey a strong wish for the police and other authorities to implement stringent measures on crowds, akin to those in the Mitsu Desu game. The authors often cited news articles on mass events and crowds that gathered inappropriately despite the pandemic. This indicates that the players observed news coverage of mass events and crowded areas primarily from the perspective of authorities such as police.

For example, one tweet expresses frustration at the large number of people not following social distancing and a strong wish for the Tokyo governor to appear there in person and disperse people as in the game. The tweet states: “There’s no choice but for Yuriko to play the real-life Mitsu Desu game seriously, saying, ‘If you’re going to eat and drink, don’t talk! If you talk, wear a mask and keep your distance!”’ (;´Д`)/[emoticon representing impatience] (「飲み食いするならしゃべるな!しゃべるならマスクをして距離を取れ!」と百合子がガチでリアル密ですゲームをやるしかないと思う(;;´Д`) /) (no. 36, July 4, 2020). Another tweet shows anger at the news that, despite recommendations for social distancing, about 50 people held a barbecue party on the banks of the Tama River, saying, “This is exactly like the stage of the game where the protagonist shouts ‘Mitsu desu Mitsu desu,’ isn’t it? lol” (『密です密です!』のゲームのリアル出番じゃないのw) (no. 89, May 4, 2020). The use of emoticons and “lol” in these tweets can likewise be interpreted as an instance of employing the Mitsu Desu game as a humorous cultural reference to cope with the hardship of enforced social distancing.

Furthermore, a total of 26.5% of the tweets correspond to reports about the behaviors and attitudes of authors and their family members when encountering a crowd in real life. Just over one-tenth (13.5%) of the tweets fall under code 3, “report having dispersed a crowd by saying ‘Mitsu desu’ in real life,’ while 13% are categorized as code 4, “reporting having the impulse to disperse crowded people by saying ‘Mitsu desu’ in real life.” These results suggest that the Mitsu Desu game heightened players’ awareness and prompted changes in real-world behavior.

Tweets classified under code 3 were posted by authors reporting that they or their family members attempted to disperse crowds in real life by saying “Mitsu desu.” For example, one mother reported: “My children spontaneously say, ‘Mitsu desu! (´艸`) Let’s keep our distance (´艸`).’ They say it both in real life and in the game” (no. 48, June 4, 2020). Another user wrote: “During commuting to and from work, I play the Mitsu Desu game in real life” (no. 166, April 20, 2020). There is also a tweet by a user whose daughter, after watching a gameplay video, began to imitate the protagonist’s actions by “putting her hand forward, saying ‘Mitsu desu!’ and trying to fly” (no. 194, April 22, 2020). This behavior reflects the protagonist’s distinctive abilities in the 3D game, specifically the ability to fly and to disperse crowds with a hand gesture, as described in the Design Elements section. Tweets no. 48 and no. 194 provide examples showing that the game protagonist’s behaviors and phrases appeared to directly influence children’s real-life actions, even among those who merely viewed the gameplay. These behaviors, such as spontaneously vocalizing “Mitsu desu!” or imitating the protagonist’s gestures, show a clear connection between in-game action and real-world behavior. The use of emoticons in tweet no. 48 suggests that the game was also employed as a humorous cultural reference to cope with the challenges of social distancing.

Representative tweets classified under code 4 were posted by users who felt the impulse to shout “Mitsu desu!” at a crowd and disperse it. For example, one user who encountered numerous groups loitering on their way home tweeted, “I was eager to play the Mitsu Desu game in real life” (リアル密ですゲームやりたすぎてうずうずした) (no. 69, May 12, 2020). Another user, frustrated by overcrowding at a local supermarket, posted, “I felt like playing the Mitsu Desu game in real life” (リアル密ですゲームやりたくなった) (no. 173, April 19, 2020). A third user, commenting on supermarket crowding around the checkout, wrote, “I would raise my hand and slash through the air [to maintain distance with other people]” (密です!ってゲームみたいに手を振り上げて、空を斬りたくなりますよね) (no. 192, April 23, 2020). This tweet illustrates the author’s impulse to replicate the protagonist’s hand-raising gesture, which is employed in both the 3D and rhythm versions of the game. These behavioral changes are likely caused by the game’s design, which requires the protagonist to perform this action repeatedly to earn points. As with tweet no. 194, these examples show that gestures from the Mitsu Desu game come to mind automatically whenever users imagine situations in which social distancing is not maintained. Thus, the tweets provide further evidence of users’ heightened awareness of crowding and social distancing.

According to the coding data, players and viewers, including children, showed increased sensitivity to crowding. They often recalled the game when they encountered crowded scenes in everyday life and sometimes shouted “Mitsu desu!” or imitated in-game gestures. These patterns point to heightened sensitivity and to changes in real-world behaviors. At the same time, the game also seems to have served as a humorous cultural reference, offering a lighthearted way to cope with stressful situations.

Building on these findings, the next section examines the extensive media dissemination that transformed the game into a widespread social phenomenon, exploring the synergistic effects of new and conventional media in amplifying its reach and impact.

Spread of the Mitsu Desu game through both new and conventional media

The Mitsu Desu game gained widespread recognition through both new and traditional media. For the Mitsu Desu game to heighten awareness and to promote changes in real-world behavior in ways that supported social distancing policies, widespread dissemination of information about the game was crucial. On new media platforms such as Twitter and YouTube, game scores shared by players, gameplay videos uploaded by creators and players, and clips from infotainment TV programs about the game uploaded by viewers were widely circulated, together expanding the game’s reach. Conventional news sites, including major news agencies and entertainment portals, also helped disseminate the game by covering it for diverse audiences. Many of these articles embedded or directly quoted gameplay videos originally posted on Twitter and YouTube, which helped increase their view counts and praised both the game and Governor Koike’s Three Cs appeal. This section examines how these various media platforms collectively fueled the Mitsu Desu game boom. The case also illustrates an example of a newsgame, a genre in which gameplay is used to highlight political or social issues, as is discussed in this section.

The interweaving of entertainment and politics through media

Among conventional media that have promoted the interweaving of entertainment and politics, infotainment TV programs in Japan have attracted international scholarly attention. Every weekday, commercial channels broadcast “wide shows” for 2 hours, sensationalizing soft news about celebrities, politics, and crime, while also covering entertainment topics such as cooking, travel, and pop culture (Ergül Reference Ergül2019). Wide shows remained a key source of pandemic-related information and helped disseminate the Three Cs slogan (Kuwahara et al. Reference Kuwahara, Kato, Ishikawa, Shinozaki and Tabuchi2023). A large survey showed that viewers of these programs were more likely to alert others about preventive behaviors than those relying on other sources (Kuwahara et al. Reference Kuwahara, Kato, Ishikawa, Shinozaki and Tabuchi2023). As detailed in this section, the boom of the Mitsu Desu game can also be understood in connection with the reach of infotainment. The game received extensive media coverage across major TV stations, national newspapers, and a wide range of online outlets in Japan (Asahi Shinbun 2020; Mainichi Shinbun 2020; Sakashita Reference Sakashita2020).

The close relationship between Japanese politicians, wide shows, and pop culture has drawn considerable academic focus worldwide. Since the 2000s, Japanese politicians have used infotainment TV programs to demonstrate leadership and appeal to the public (Mulgan Reference Mulgan, Pekkanen and Pekkanen2022). Around 2005, the Japanese government also began using pop culture, particularly manga and video games, for nation branding under the “Cool Japan” slogan (Valaskivi Reference Valaskivi2013). In 2013, the Liberal Democratic Party launched the browser game “Abe-pyon,” featuring Prime Minister Shinzō Abe (Williams and Miller Reference Williams, Miller, Pekkanen, Reed and Scheiner2016).Footnote 2 In 2016, during the Rio Olympic closing ceremony, Abe announced Japan would host the 2020 Olympics while cosplaying as Mario from “Super Mario” (Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson2019). Against this cultural and political context, the creation of a game featuring Governor Koike was likely encouraged.

In the context of research on the intersection between journalism and video games, Bogost et al. (Reference Bogost, Ferrari and Schweizer2010) conceptualize a category of video games known as “newsgames,” in which players experience the dynamics of political and social systems and help disseminate specific policies or political messages. The Mitsu Desu game fits this genre, as it features a well-known political figure as a protagonist and allows players to simulate 2-m social distancing. Through their in-game actions, players may have supported and disseminated the government’s political slogan and enhanced Governor Yuriko Koike’s popularity. This background also may help explain the emergence of a game that features Governor Koike herself as the central character.

Given these contexts, investigating a Japanese case in which video games featuring the Tokyo Governor as the protagonist supported the implementation of social distancing policies should broaden our understanding of the connection between entertainment and politics.

Data

To examine the media dissemination of the Mitsu Desu game, this section utilizes various data extracted from the Internet as follows. It analyzes 28,132 tweets that were posted between April 15 and June 2, 2020, and were retrieved on June 3, 2020. These tweets were primarily gathered to investigate the spread of different types of games referred to as the “Mitsu Desu” game on Twitter. This period coincides with the first national-level state of emergency in Japan. These tweets were retrieved using the Python library “GetOldTweets3” with the Japanese search term “Mitsu Desu game.” The timespan during which the tweets were posted corresponds to the period when the number of tweets peaked (12,897 tweets on April 18) and the number of daily tweets gradually decreased to single digits.

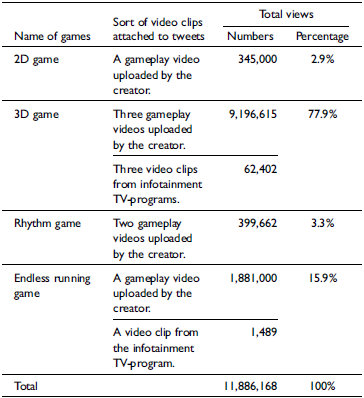

This section also utilized view count data from videos attached to tweets posted by the creators of four popular Mitsu Desu games. Between April 14 and May 26, 2020, these creators shared tweets with gameplay videos as well as videos recording infotainment TV news programs covering their games. Later, on August 2, 2020, the creators posted additional videos attached to tweets. The number of views for all videos attached to these tweets was tallied on August 20, 2020, totaling 11,886,168 views.

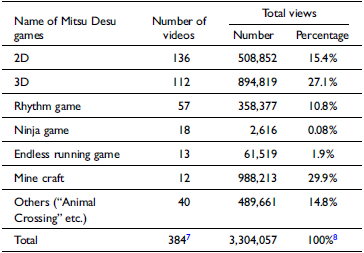

Data on YouTube videos related to the Mitsu Desu game (upload date, title, channel and the number of their subscribers, view count, and the number of reactions such as like and dislike) were also manually collected using copy and paste. The 384 videos were identified on June 9, 2020, through YouTube’s advanced search and the search terms “Mitsu desu” and “game.” Additionally, 75 news and blog articles were detected using Google Search with the search term “Mitsu Desu game” on November 30, 2020 and extracted.

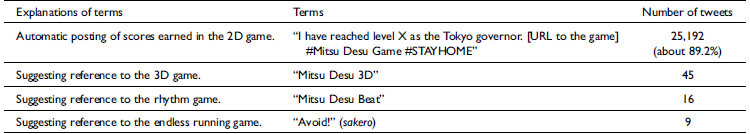

The spread of the Mitsu Desu game via Twitter

With regard to Twitter, the automatic posting of scores and gameplay videos attached to tweets by the creators of the Mitsu Desu game has significantly contributed to the boom of the game. As shown in Figure 3, the number of tweets containing the term “Mitsu Desu game” peaked shortly after the release of the 2D game on April 16, 2020 and experienced a slight increase after the release of the 3D game on April 23, 2020.

Figure 3: Daily counts of tweets containing the term “Mitsu Desu Game” (2020).

The peak, driven by tweets about the 2D game, which accounted for 89.2% of the total, appears to have been triggered by the 2D game’s automatic score-posting feature, shown in Figure 4, which allowed users to easily tweet their scores upon game over. Unlike the 2D game, the 3D game and the endless running game lacked such automatic posting functions and were therefore mentioned only rarely in tweets. However, even the rhythm game, which included an auto-posting mechanism stating, “I cleared X [song title] with a density (mitsu-degree) of XX.X%! [Link to the game] #Mitsu Desu Beat Game,” generated only 313 tweets.Footnote 3 This discrepancy can be attributed to the design features shown in Figure 4: in the rhythm game, the button for posting scores on Twitter was placed on the screen as a small bird icon without any clear label, whereas in the 2D game, the posting button clearly displayed the phrase “Tweet” in Japanese.

Figure 4: Screens of four games after completion or game over.

Note: Top left: 2D game, top right: rhythm game; bottom left: 3D game, bottom right: endless running game.

In addition to the presence and recognizability of an auto-posting function, the content of the auto-generated tweets also influenced user behavior. The 2D game featured humorous phrasing such as “I have reached level X [reached stage number] as the Tokyo governor,” which may have encouraged more users to post. While the rhythm game also used auto-posted messages, the play on words involving “density” (mitsu-degree) was clever but arguably less humorous or relatable than the notion of advancing as the Tokyo governor. These findings indicate that both interface design and the tone of automated content substantially influenced players’ willingness to share their results.

As presented in Table 4, the popularity of the four games is further substantiated by the impressive view counts of gameplay videos shared by their creators on Twitter and YouTube. In particular, the creator of the 3D game posted videos that received more than 9 million views on Twitter and more than 890,000 views on YouTube. These high quantitative figures were likely reinforced by compelling stories covered by infotainment television programs and subsequently circulated on Twitter. For example, the creator, Mose Sakashita, appears in a video in which he reveals that he is a graduate student at Cornell University in New York and explains that Governor Koike’s “Mitsu desu!” exclamation directly inspired the creation of the game. The unexpected connection between a prominent politician and social distancing policies through a game seems to have attracted public curiosity and interest. Additionally, the game’s development by a highly educated creator may have added to this appeal. The game also attracted media attention because the U.S. lockdown provided the creator with time to develop it, allowing him to influence social distancing policies in Japan despite the geographical distance (MyNavi 2020). These factors together likely contributed to the high viewership numbers.

Table 3. Frequently used terms in 28,231 tweets extracted with the term “Mitsu Desu game”

Table 4. Total views of video clips uploaded on TwitterFootnote 5

The spread of the Mitsu Desu game via YouTube

Gameplay videos uploaded on YouTube—commonly referred to as jikkyō dōga (gameplay commentary videos) in Japan and Let’s Play in English-speaking contexts—have also contributed to the awareness of the Mitsu Desu game.Footnote 4 This includes the four examples discussed above as well as other related titles in the genre. As presented in Table 5, the number of gameplay videos and their view counts is high for the 2D, 3D, and rhythm games. The Ninja Game (officially named Mitsu!) is one of the games posted for the aforementioned 1-week game jam. In the game, a ninja progresses through a castle, blowing away enemies gathered around him. This game also drew the attention of several YouTubers. Moreover, videos of gameplay that incorporated elements of the Mitsu Desu game, such as blowing away enemies gathered around the player’s avatar, into commercial games such as Minecraft and Animal Crossing, have also garnered significant views. Among the uploaders of the 384 videos, 12 influencers had more than 100,000 subscribers. This may also have greatly influenced the widespread popularity of the Mitsu Desu game on YouTube.

Table 5. Total views of gameplay videos uploaded on YouTubeFootnote 6

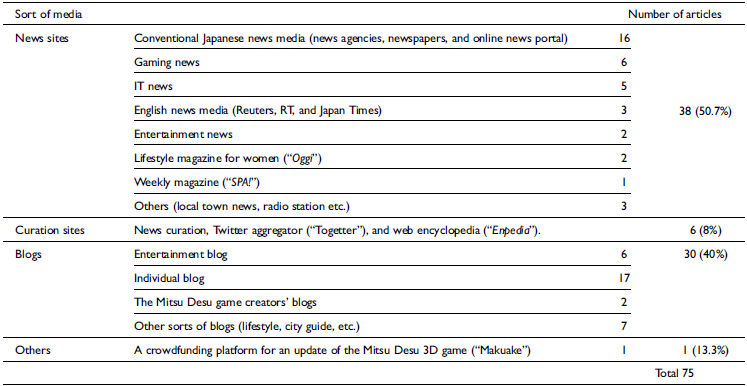

The spread of the Mitsu Desu game via news and blog articles

Not only did Twitter, YouTube, and video clips from infotainment TV programs play a role in disseminating the game, but web articles also fueled the boom and supported the implementation of social distancing policies. Table 6 presents the results of classifying the publishers of 75 web articles extracted through a Google search using the keyword “Mitsu Desu game.” The types of sites were primarily classified qualitatively on the basis of the introduction provided on each site. Among the 75 articles, just over 50% were from Japanese and English news sites, while 40% were blog articles. News articles spanned a broad spectrum. They ranged from elite media—including major newspapers and news agencies—to entertainment news sites that primarily focus on celebrities, such as actors and idols, dramas, and even news targeting specific readerships in IT and games. This suggests that the readership of articles related to the Mitsu Desu game was diverse.

Table 6. Categorization of web article publishers on the Mitsu Desu game

Web articles on the Mitsu Desu game also contributed to the spread of the game through Twitter and YouTube. They often embedded gameplay videos uploaded by creators and players of the Mitsu Desu game on Twitter and YouTube into their own articles. The embedding of such gameplay videos may have increased number of views and broadened the audience. Even newsreaders who do not usually play games may have gained an impression of the game and become interested in playing it.

The web articles may have exposed gamers, including those with little interest in politics, to political news. Almost all news articles related to the Mitsu Desu game addressed both entertainment and politics simultaneously. These news articles began by positively explaining the Three Cs slogan and Governor Koike’s involvement in social distancing policies as an introduction. Afterward, they proceeded to describe the boom of the Mitsu Desu game. Thus, these articles not only raised awareness of the Mitsu Desu game boom, but also likely enhanced understanding of social distancing policies and supported their implementation. The following is an example of a news article:

The nationwide state of emergency in Japan has been declared due to the outbreak of the new coronavirus. Yuriko Koike, the governor leading the forefront in Tokyo, holds almost daily press conferences, urging citizens to take the increase in infections more seriously. As part of the infection prevention measures, emphasizing the importance of avoiding the Three Cs (closed spaces, crowded places, close-contact settings) for social distancing, a phrase uttered by Governor Koike to the press, “Mitsu desu” (it’s crowded), has become a trend on the Internet. It has even become material for manga, music, and video content. On the 20th, on Twitter, a game clip titled “Mitsu Desu game” emerged (AFP 2020).

Although this article is about entertainment phenomena, as long as it reaffirms the meaning of the Three Cs slogan, it supports social distancing policies. Moreover, given that the article also praises Governor Koike for her full commitment to COVID-19 measures, it is highly likely that it contributed to enhancing her popularity. Thus, the coverage of the Mitsu Desu game in both new and conventional media delivered political slogans to an audience primarily interested in entertainment, while also potentially boosting the popularity of a specific politician.

Conclusions

This article comprehensively explores how the boom of the Mitsu Desu game emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic and suggested a supportive role in the implementation of social distancing policies in Japan. The first section shows that diverse game design elements, such as the 2D game’s clear visualization of social distancing and the 3D game’s item-collecting system, attracted players and encouraged repeated gameplay. These qualitative features are reflected in quantitative indicators, including high view counts of gameplay videos and frequent score sharing, which further reinforced the dissemination of the Three Cs slogan and Governor Koike’s public presence.

The second section demonstrates, through qualitative coding of tweets posted by players, that the game heightened players’ sensitivity to crowded situations. It further shows that the similarity between the game and real-life settings heightened awareness and promoted concrete, observable changes in behavior in real-world contexts, and that the game functioned as a humorous cultural reference for coping with the challenges of social distancing.

The final section highlights the synergistic interaction between conventional and new media, which amplified the visibility of the Mitsu Desu game and contributed to its emergence as a widespread social phenomenon. Rapid sharing of user-generated content on Twitter and YouTube, combined with coverage from news outlets and television programs, reinforced public awareness of the game and associated social distancing measures. This interaction also emphasized Governor Koike’s efforts and may have contributed to an increase in her popularity.

This paper’s integrated approach illustrates how strategically designed and disseminated video games can transcend mere entertainment and possess the capacity to function as informal tools of social control and policy implementation, leveraging popular culture to connect in-game actions to players’ and viewers’ interpretations of real-world behavior. The Mitsu Desu game boom demonstrates that a game based on real-life events can entertain, while playing a role in reinforcing government policies and contributing to the public presence of a political figure. At the same time, when a real politician is featured as the protagonist, the game’s potential to imagine alternative futures, reshape political engagement, and foster resistance to official rhetoric—as suggested by Roth (Reference Roth2018) and Whaley (Reference Whaley2023)—may be limited.

The Mitsu Desu game emerged under the exceptional conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, which restricted physical movement and disrupted the supply of new entertainment. As this study shows, video games have the potential to serve as tools of social control in other uncertain contexts such as natural disasters or wartime. Given that games are becoming increasingly integrated into everyday life, further research is needed to explore how video games, as a form of popular culture, stimulate changes in real-world behavior, and whether the presence or absence of players’ critical reflection on the status quo determines their ultimate contribution to or resistance against government policies.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author Biography

Ayaka Löschke is a junior professor of Japanese Studies at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. She earned her PhD in 2018 from the University of Zurich, with a dissertation on post-Fukushima activism aimed at protecting people from radiation. Her current research interests include the regulation of far-right demonstrations and both offline and online activism against far-right users. She can be reached via email at ayaka.loeschke@gmail.com.