Background

Hypertension (HTN) is the primary cause of preventable cardiovascular-related deaths globally (Skar et al. Reference Skar, Young and Gordon2015; Yusuf et al. Reference Yusuf, Joseph, Rangarajan and Dagenais2020; Dai et al. Reference Dai, Bragazzi, Younis and Grossman2021) and represents the most important modifiable risk factor for preventing such deaths (Nguyen & Chow Reference Nguyen and Chow2021). An estimated 700 million of the 1.3 billion adults with HTN worldwide remain untreated; the majority of these individuals live in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), including in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), due to low rates of detection and treatment despite the relatively simple and low-cost nature of these interventions (World Health Organization 2021). Untreated HTN is also influenced by the often asymptomatic nature of this condition, as well as contextual factors such as lack of awareness of HTN, limited availability of primary health care services, and socioeconomic and systemic deterrents to health care utilisation such as limited financial resources, long distances to health facilities, and long waits to receive care at a healthcare facility (Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Angell, Asma and Wang2016; Schutte et al. Reference Schutte, Jafar, Poulter and Tomaszewski2023).

Barriers to the diagnosis of HTN also impact treatment adherence after diagnosis and the initiation of treatment. Adherence to HTN treatment remains a global problem, and it is more pronounced in LMICs due to the factors described above, which contribute to a substantial mismatch between the needs of patients and the resources available to meet these needs (Boima et al. Reference Boima, Ademola, Odusola and Tayo2015; Aovare et al. Reference Aovare, Abdulai, Laar and Agyemang2023). This scoping review uses a qualitative synthesis method to examine the cultural and contextual factors influencing HTN treatment adherence in East Africa and the lived experiences of patients with HTN to gain a better understanding of these factors in the region. All included countries, but Seychelles, are LMICs. This review incorporates studies using a qualitative design as well as those using a mixed-methods design containing a qualitative component. The goal of this review is to inform practical decision-making for future interventions that can be tested.

Adherence to treatment is defined as the extent to which individuals living with a health problem follow a treatment plan that has been mutually agreed upon with their health providers (Fernandez-Lazaro et al. Reference Fernandez-Lazaro, García-González, Adams and Miron-Canelo2019). For HTN, the treatment plan typically includes medication and diet, exercise, and other lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation and/or reduction of alcohol use. Globally, of patients who received treatment for HTN, nearly four in every five of them do not have their blood pressure controlled (World Health Organization 2023a). Factors influencing poor HTN control vary based on one’s environment through the interplay of social networks, cultural norms, economic conditions, and contextual factors guiding their beliefs and choices (Chaturvedi et al. Reference Chaturvedi, Zhu, Gadela, Prabhakaran and Jafar2024). However, despite extensive literature on the prevalence of HTN and determinants of treatment adherence in some LMICs, there is limited literature synthesising the contextual and cultural factors influencing HTN treatment adherence in the East African region.

In SSA, which comprises several regions including East Africa, the prevalence of HTN continues to increase (Dai et al. Reference Dai, Bragazzi, Younis and Grossman2021) while adherence remains a problem. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Ataklte et al. (Reference Ataklte, Erqou, Kaptoge, Taye, Echouffo-Tcheugui and Kengne2015) on the burden of HTN in SSA found that only 27% people in SSA were aware of their HTN status, 18% of those who were aware started on treatment, and only 7% of them had their blood pressure controlled (Ataklte et al. Reference Ataklte, Erqou, Kaptoge, Taye, Echouffo-Tcheugui and Kengne2015). Limited awareness of HTN and its complications contributes to low screening and treatment rates for HTN (Kruk et al. Reference Kruk, Nigenda and Knaul2015; Chang et al. Reference Chang, Hawley, Kalyesubula and Rabin2019; Muhihi et al. Reference Muhihi, Anaeli, Mpembeni and Urassa2020) and low rates of adherence to treatment (Boima et al. Reference Boima, Ademola, Odusola and Tayo2015; Aovare et al. Reference Aovare, Abdulai, Laar and Agyemang2023). Thus, besides screening and treatment initiation, it is important to identify contextual factors influencing adherence to HTN treatment to help develop effective strategies that target contextual barriers and promote treatment adherence.

Chronic health problems such as HTN necessitate adherence to treatment for improved outcomes (Aovare et al. Reference Aovare, Abdulai, Laar and Agyemang2023). Despite extensive knowledge of the importance of community-engaged approaches to address infectious diseases (Genberg et al. Reference Genberg, Shangani, Sabatino and Operario2016) and maternal and child health problems in the region (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Alim, Kengne and Patel2014; Perry et al. Reference Perry, Zulliger and Rogers2014), there is minimal literature on such approaches pertaining to the treatment adherence to chronic, non-communicable conditions like HTN in LMICs, including East Africa. There is also limited literature on engaging people in low-resource settings in their care for prevention and treatment of HTN (Vedanthan et al. Reference Vedanthan, Bernabe-Ortiz, Herasme and Fuster2017; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Pullar, Wickramasinghe and Townsend2018). Additionally, HTN research specific to the East African region has been sparse. Previous literature has documented the broad distribution and diversity of medication-related risk factors in Africa (Shin & Konlan, Reference Shin and Konlan2023). Identifying the regional factors influencing treatment adherence in East Africa could help to mitigate their impact on care and promote patients’ engagement in their own care. Examining the regional literature in detail will facilitate the development of tailored interventions that meet the needs of individuals in this region of the world.

The objectives of this research, identified using a PEO (population, exposure, and outcome) approach (Brennan Reference Brennann.d.), are to (1) describe the barriers and facilitators to HTN treatment adherence in East Africa and (2) share perspectives on the prominence of each factor in the literature.

Methods

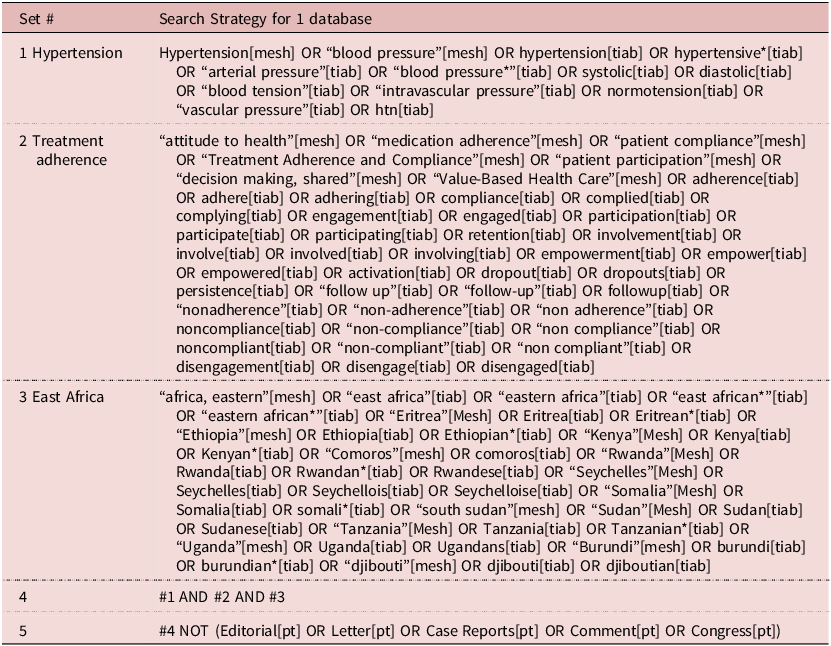

The team conducted a systematic search of published research examining HTN treatment adherence in East Africa. It was carried out using the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Peters et al. Reference Peters, McInerney, Munn, Tricco and Khalil2020) and is reported following the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al. Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin and Straus2018). A protocol was registered with Open Science Framework Registries in October 2023 and updated in December 2023 (registration # 10.17605/OSF.IO/5PQGT). The databases searched included MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase (Elsevier), CINAHL (Ebscohost), and Web of Science (Elsevier). The search was developed and conducted by a medical librarian (3rd author) in consultation with the author team and included a mix of keywords and subject headings representing HTN, treatment adherence, and East Africa, respectively (see Table 1). The searches were independently peer reviewed by a second librarian using a modified PRESS Checklist (McGowan et al. Reference McGowan, Sampson, Salzwedel, Cogo, Foerster and Lefebvre2016).

Table 1. Search Strategy

Search hedges or database filters were used to remove publication types such as editorials, letters, case reports, comments, and animal-only studies as appropriate for each database. The initial search was conducted on 18 October 2023 with 3,406 citations returned. The reference lists of the final set of included articles were reviewed manually to identify studies potentially missed in the search. In December 2024, citation tracking (Haddaway et al. Reference Haddaway, Grainger and Gray2021) was used to identify additional relevant studies; 846 additional abstracts were returned. An updated search was conducted on 21 October 2025 to include current relevant literature in the review up to that date. Using all four databases, a total of 1,092 abstracts were retrieved and screened for inclusion.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for the final review were as follows: articles defining HTN management and treatment adherence in any country in East Africa in adult populations using a qualitative or mixed-methods design with sufficiently detailed descriptions of their methodologies and findings for their qualitative arm. In this study, the East Africa regional delineation was derived from the African Development Bank Group, which includes 13 countries: Burundi, Comoros, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda (Bank Reference Bank2019). The review incorporated studies conducted on HTN and other comorbidities if they reported separate results for HTN as opposed to a combined section for both HTN and the other comorbidity (ies).

Exclusion criteria for this scoping review included studies primarily focused on other health problems besides HTN and studies conducted with individuals from the East African diaspora now living in other countries (e.g., refugee or immigrant populations). Prior reviews and study protocols were also excluded, along with studies conducted in other African regions or high-income countries, studies not in English, and unpublished data.

Selection process

All identified studies were uploaded into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation n.d.), an online platform for managing systematic reviews. Duplicates were removed by the software (n = 1,636). A final set of 1,770 citations remained for screening in the title/abstract phase. Study screening and final selection were each carried out independently by two authors after a pilot screen of 10 articles (1st and 2nd).

Studies were excluded during screening if they did not clearly meet the inclusion criteria based on title and abstract review. All disagreements were resolved by discussion among 1st and 2nd authors and with the 4th author’s input when warranted. With the help of a medical librarian, the full texts of the remaining articles were uploaded for review and assessed for final inclusion. In December 2024, of the 846 additional abstracts returned through citation tracking, 22 additional studies were added for full-text review. In October 2025, 1092 additional titles/abstracts were screened from the final search after duplicates were removed by Covidence. Twenty additional studies were added for full-text review. Again, any conflicts between the two independent reviewers were resolved to a consensus through discussion. The article selection is presented by a flowchart as per PRISMA guidelines (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Data collection process

Data items

Two reviewers (1st and 2nd authors) extracted data independently from each included study using a Data Extraction Form that included the following: lead author’s name, year of publication, title, country, study aim, study type, settings, language the study was conducted in, number and type of participants, HTN status of participants, study findings, funding sources, and author-identified strengths and limitations. Any disagreements in the extractions were discussed among the reviewers until agreement was achieved.

Synthesis methods

This study synthesis was guided by methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Qualitative Studies, with a particular focus on the Cochrane qualitative Methodological Limitations Tool (CAMELOT) used alongside GRADE-CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research) (Munthe-Kaas et al. Reference Munthe-Kaas, Booth, Sommer and Group2024). CAMELOT was used to develop the data extraction form and systematically analyse the selected studies (Munthe-Kaas et al. Reference Munthe-Kaas, Booth, Sommer and Group2024). This structured extraction then allowed us to systematically cross-compare included studies and identify recurring themes regarding patients’ experiences with HTN treatment (Munthe-Kaas et al. Reference Munthe-Kaas, Booth, Sommer and Group2024). The analysis focused on factors affecting HTN treatment adherence, participants’ perceptions, and the broader contextual influences on adherence.

Although critical appraisal of primary studies is not required in scoping reviews, the GRADE CERQUAL approach was applied to assess methodological limitations of the included studies and their general quality (Munthe-Kaas et al. Reference Munthe-Kaas, Booth, Sommer and Group2024) to enhance trustworthiness (i.e., credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability) (Lincoln & Guba Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). Ratings were provided by two team members (1st and 2nd authors), and discrepancies among the two reviewers were resolved through discussions. Most studies were graded moderate to high methodological quality, with descriptions of their data collection and analysis. Few studies discussed reflexivity or confirmability, a potential limitation to the dependability of the reported findings.

Results

Overview of included studies

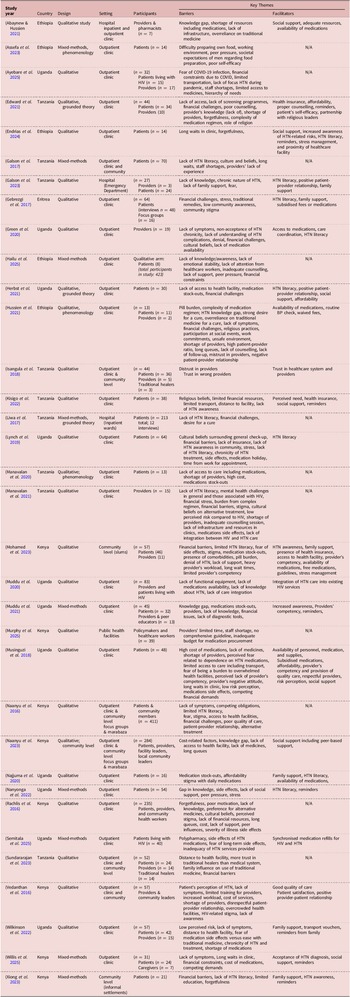

A total of 34 studies, including 25 qualitative and 9 mixed-methods designs, were included in the final review. Studies were from the following five East African nations: Uganda (n = 11), Tanzania (n=9), Kenya (n = 8), Ethiopia (n = 5), and Eritrea (n = 1), all of which are LMICs. Most of the studies (n = 24) were conducted in an outpatient clinic setting, 6 of them in both outpatient clinics and community settings, 2 in community settings, and the remaining 2 in hospital settings. In total, 30 of the studies included individuals with HTN, 17 included HTN providers, 3 included community leaders, 2 included traditional healers, one included caregivers, and policymakers participated in one. Identified factors associated with HTN are classified into two main categories in relation to the research aim, which are barriers and facilitators. Table 2 provides an abridged version of the characteristics of the included studies. Most of the studies reported either on barriers or facilitators, with some studies reporting on both.

Table 2. Overview of included studies

The sample size of included studies ranged widely from 7 to 411 participants, with a mean of 60 and a median of 40 participants enrolled in the qualitative aspect of the studies. Methods of data collection encompassed individual interviews, focus groups, and traditional community assemblies called mabaraza. Twenty-five studies employed thematic analysis to extract their findings, five applied content analysis, one study used an abductive analytical approach, while three utilised a combination of methods. Twenty-eight of the 34 studies reported the language in which data collection was done, which was either English or the local language.

Perceived associations with HTN treatment adherence

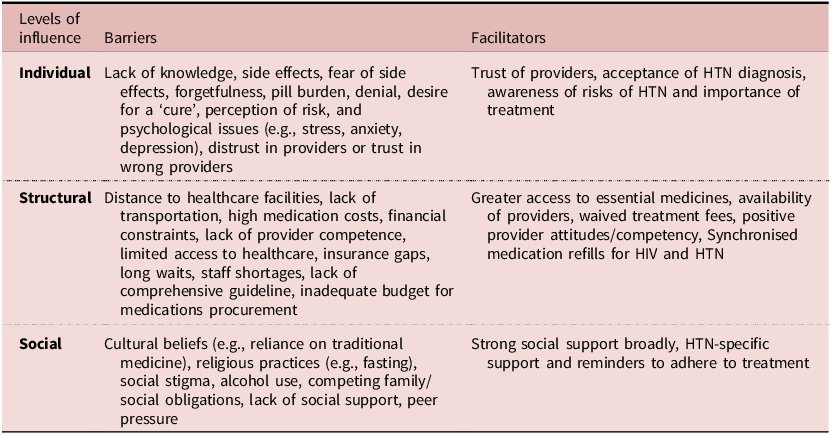

Each main category of barriers and facilitators was further subdivided into three levels of perceived association with HTN treatment adherence: individual, structural, and social. Individual factors focused on personal, internal characteristics or challenges that an individual may face in regard to HTN treatment adherence, which include psychological, cognitive, and behavioural factors (World Health Organization 2024). Structural factors addressed issues at the healthcare system level, such as access to care, affordability, and quality of services (World Health Organization 2024). Social factors reflect the external influences of culture, family, and society that shape attitudes toward chronic illness and treatment, as well as the practicalities of adhering to a treatment plan in the context of one’s social environment (World Health Organization 2024). Table 3 contains a summary of barriers and facilitators by level of influence.

Table 3. Summary of barriers and facilitators

Reported barriers to HTN treatment adherence

A. Individual barriers to adherence

Individual barriers to HTN treatment adherence stemmed from the individual’s personal behaviours, psychological state, and knowledge that interfered with their ability to follow prescribed treatment plans. Most studies (n=14) reported lack of knowledge and awareness about HTN, its treatment, its chronic nature, risks, and complications, all of which were perceived contributors to non-adherence, as patients may not understand the importance of following the prescribed regimen (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Galson et al. Reference Galson, Staton, Karia and Stanifer2017; Liwa et al. Reference Liwa, Roediger, Jaka and Peck2017; Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Green, Clarke Nanyonga and Heller2019; Green et al. Reference Green, Lynch, Nanyonga and Heller2020; Abaynew & Hussien Reference Abaynew and Hussien2021; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Nanyonga et al. Reference Nanyonga, Spies and Nakaggwa2022; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Garden, Nanyonga and Heller2022; Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Zeleke, Sergo, Misganaw and Mekonnen2023; Galson et al. Reference Galson, Pesambili, Vissoci and Stanifer2023; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Peoples, Ostbye and Yan2023; Hailu et al. Reference Hailu, Yigezu, Gutema and Hordofa2025). Lack of knowledge about the role of medication in managing HTN was an added component across several studies, along with lack of symptoms leading patients to decide that treatment was not important (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Rachlis et al. Reference Rachlis, Naanyu, Wachira and Braitstein2016; Vedanthan et al. Reference Vedanthan, Tuikong, Kofler and Fuster2016; Galson et al. Reference Galson, Staton, Karia and Stanifer2017; Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Green, Clarke Nanyonga and Heller2019; Green et al. Reference Green, Lynch, Nanyonga and Heller2020; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Tusubira, Nakirya and Ssinabulya2020; Hussien et al. Reference Hussien, Muhye, Abebe and Ambaw2021; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Garden, Nanyonga and Heller2022; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Peoples, Ostbye and Yan2023; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023; Willis et al. Reference Willis, Mbuthia, Gichagua and Murphy2025).

Some studies reported experiencing side effects or fear of side effects as causes for patients to stop their medications, especially if the side effects were severe or uncomfortable (Rachlis et al. Reference Rachlis, Naanyu, Wachira and Braitstein2016; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Nanyonga et al. Reference Nanyonga, Spies and Nakaggwa2022; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Garden, Nanyonga and Heller2022; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023; Semitala et al. Reference Semitala, Ayebare, Kiggundu and Katahoire2025). Adherence was also hindered by fear of being screened for stigmatised conditions such as HIV (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Vedanthan et al. Reference Vedanthan, Tuikong, Kofler and Fuster2016), fear of being burdensome to families (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016), and fatalism (Galson et al. Reference Galson, Pesambili, Vissoci and Stanifer2023). Forgetfulness, particularly with complex treatment regimens, was another reported barrier, leading to missed medication doses (Rachlis et al. Reference Rachlis, Naanyu, Wachira and Braitstein2016; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Peoples, Ostbye and Yan2023; Endrias et al. Reference Endrias, Geta, Desalegn and Nigussie2024). Additionally, pill burden of having to take multiple medications or follow complicated schedules was reported to overwhelm some patients, causing them to skip doses or stop treatment altogether (Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Hussien et al. Reference Hussien, Muhye, Abebe and Ambaw2021; Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Wanda, Galson, Thielman, Mmbaga and Watt2021; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023; Semitala et al. Reference Semitala, Ayebare, Kiggundu and Katahoire2025). Denial of HTN as a health problem or refusal to accept the need for long-term treatment also played a role, as some patients may not believe their condition is serious enough to warrant medication (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016); Green et al. Reference Green, Lynch, Nanyonga and Heller2020; Hussien et al. Reference Hussien, Muhye, Abebe and Ambaw2021; Mohamed et al. (Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023).

The desire for a ‘cure’, sometimes through traditional or alternative therapies, drove patients to discontinue prescribed medications (Liwa et al. Reference Liwa, Roediger, Jaka and Peck2017; Hussien et al. Reference Hussien, Muhye, Abebe and Ambaw2021). Furthermore, patients’ low perception of the risk of not adhering to HTN treatment negatively influenced some patients’ commitment to their prescribed regimen (Vedanthan et al. Reference Vedanthan, Tuikong, Kofler and Fuster2016); (Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Garden, Nanyonga and Heller2022). Finally, psychological issues such as stress, anxiety, or depression were cited as sapping a patient’s motivation, making adherence seem overly burdensome or unimportant (Gebrezgi et al. Reference Gebrezgi, Trepka and Kidane2017; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Wanda, Galson, Thielman, Mmbaga and Watt2021; Nanyonga et al. Reference Nanyonga, Spies and Nakaggwa2022; Hailu et al. Reference Hailu, Yigezu, Gutema and Hordofa2025). Mistrust in the health system or in providers was another contributing factor hindering treatment adherence (Isangula et al. Reference Isangula, Seale, Nyamhanga, Jayasuriya and Stephenson2018); (Green et al. Reference Green, Lynch, Nanyonga and Heller2020), as was trust in the wrong providers, causing vulnerability to malpractice and overreliance on one provider (Isangula et al. Reference Isangula, Seale, Nyamhanga, Jayasuriya and Stephenson2018). Several of these barriers often overlapped, creating a complex and multidirectional challenge to address both the psychological and practical aspects of HTN treatment adherence.

B. Structural barriers to adherence

Reported structural barriers to HTN treatment adherence were largely shaped by factors within the healthcare environment, including issues related to access, cost, and the quality of care provided. These barriers often interact, creating significant challenges for patients in managing their HTN effectively. These barriers are grouped into (1) healthcare access and availability, (2) financial barriers, and (3) healthcare system barriers.

Healthcare access and availability: One of the most significant reported structural barriers was limited access to healthcare services and medications (Rachlis et al. Reference Rachlis, Naanyu, Wachira and Braitstein2016; Green et al. Reference Green, Lynch, Nanyonga and Heller2020; Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Minja, Wanda and Watt2020; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Tusubira, Nakirya and Ssinabulya2020; Abaynew & Hussien Reference Abaynew and Hussien2021; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021; Kisigo et al. Reference Kisigo, Mcharo, Robert, Peck, Sundararajan and Okello2022; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Garden, Nanyonga and Heller2022; Galson et al. Reference Galson, Pesambili, Vissoci and Stanifer2023; Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Njuguna, Koros and Akwanalo2023; Sundararajan et al. Reference Sundararajan, Alakiu, Ponticiello and Peck2023; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Peoples, Ostbye and Yan2023) and limited infrastructures such as consultation rooms (Vedanthan et al. Reference Vedanthan, Tuikong, Kofler and Fuster2016; Abaynew & Hussien Reference Abaynew and Hussien2021; Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Njuguna, Koros and Akwanalo2023), particularly in rural or underserved areas. Patients often faced long distances to travel to clinics or healthcare facilities (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021; Kisigo et al. Reference Kisigo, Mcharo, Robert, Peck, Sundararajan and Okello2022; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Garden, Nanyonga and Heller2022; Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Njuguna, Koros and Akwanalo2023; Sundararajan et al. Reference Sundararajan, Alakiu, Ponticiello and Peck2023), and a lack of reliable transportation further exacerbated patients’ non-adherence to their treatment (Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Kisigo et al. Reference Kisigo, Mcharo, Robert, Peck, Sundararajan and Okello2022; Ayebare et al. Reference Ayebare, Siu, Kaawa-Mafigiri and Katahoire2025). Additionally, participants described inconvenient clinic hours due to designated HTN clinic days, long wait times (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Rachlis et al. Reference Rachlis, Naanyu, Wachira and Braitstein2016; Vedanthan et al. Reference Vedanthan, Tuikong, Kofler and Fuster2016; Galson et al. Reference Galson, Staton, Karia and Stanifer2017; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Green, Clarke Nanyonga and Heller2019; Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Minja, Wanda and Watt2020; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021; Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Njuguna, Koros and Akwanalo2023; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023; Endrias et al. Reference Endrias, Geta, Desalegn and Nigussie2024; Willis et al. Reference Willis, Mbuthia, Gichagua and Murphy2025), lack of blood pressure monitoring equipment (Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Tusubira, Nakirya and Ssinabulya2020), and limited access to skilled healthcare providers (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Vedanthan et al. Reference Vedanthan, Tuikong, Kofler and Fuster2016; Galson et al. Reference Galson, Staton, Karia and Stanifer2017; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Minja, Wanda and Watt2020; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Wanda, Galson, Thielman, Mmbaga and Watt2021; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Mbuthia, Willis and Reich2025), especially at lower-level facilities, as important factors that discouraged patients from seeking care, remaining in care, and/or adhering to their prescribed treatment plans. This lack of consistent access to high-quality treatment reduced the likelihood of regular follow-up appointments, which are essential for the long-term monitoring and management of blood pressure and adjusting treatment as needed.

Financial barriers: The cost of medications and treatment was a major obstacle to HTN treatment adherence across several studies (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Gebrezgi et al. 201); Liwa et al. Reference Liwa, Roediger, Jaka and Peck2017; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Green, Clarke Nanyonga and Heller2019; Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Minja, Wanda and Watt2020; Najjuma et al. Reference Najjuma, Brennaman, Nabirye and Muhindo2020; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021; Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Wanda, Galson, Thielman, Mmbaga and Watt2021; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Galson et al. Reference Galson, Pesambili, Vissoci and Stanifer2023; Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Njuguna, Koros and Akwanalo2023; Sundararajan et al. Reference Sundararajan, Alakiu, Ponticiello and Peck2023; Willis et al. Reference Willis, Mbuthia, Gichagua and Murphy2025). High medication prices (Liwa et al. Reference Liwa, Roediger, Jaka and Peck2017; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Minja, Wanda and Watt2020; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Hailu et al. Reference Hailu, Yigezu, Gutema and Hordofa2025; Willis et al. (Reference Willis, Mbuthia, Gichagua and Murphy2025), coupled with the burden of managing HTN with multiple drugs, were financially prohibitive for many patients (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021). Moreover, those without health insurance or with inadequate coverage faced significant out-of-pocket expenses for medications and consultations, which led them to forgo treatment (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; (Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Green, Clarke Nanyonga and Heller2019; Najjuma et al. Reference Najjuma, Brennaman, Nabirye and Muhindo2020; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021; Willis et al. Reference Willis, Mbuthia, Gichagua and Murphy2025). Financial stress often led patients to prioritise other, more immediate financial needs over their healthcare, leading to skipped doses or missed appointments.

Additionally, healthcare system barriers, which are systemic issues within the healthcare system, also affected HTN treatment adherence. Perception of a lack of competency among healthcare providers and perception of poor care (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Galson et al. Reference Galson, Staton, Karia and Stanifer2017; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023; Hailu et al. Reference Hailu, Yigezu, Gutema and Hordofa2025; Semitala et al. Reference Semitala, Ayebare, Kiggundu and Katahoire2025), providers’ lack of knowledge managing HTN and HIV drug interactions (Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021), and lack of HTN treatment protocols (Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Mbuthia, Willis and Reich2025), particularly in lower-level health facilities, undermined patients’ confidence in the prescribed treatment plans. In some cases, limited availability of affordable, quality medications (Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Najjuma et al. Reference Najjuma, Brennaman, Nabirye and Muhindo2020; Abaynew & Hussien Reference Abaynew and Hussien2021; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Garden, Nanyonga and Heller2022; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Mbuthia, Willis and Reich2025) meant that patients were unable to obtain the correct medications or forced to use less effective alternatives that were more affordable or readily available (Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018). Additionally, the lack of continuity in care, whether due to fragmented health services, missed appointments, or inadequate follow-up, disrupted treatment plans and hindered the consistent management of HTN (Isangula et al. Reference Isangula, Seale, Nyamhanga, Jayasuriya and Stephenson2018). Moreover, disrespectful care and negative patient-provider interactions (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Vedanthan et al. Reference Vedanthan, Tuikong, Kofler and Fuster2016; Abaynew & Hussien Reference Abaynew and Hussien2021), providers’ negative attitudes, and patients’ fear of harsh treatment were reported as hindering HTN treatment adherence (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018).

One study explored the barriers to HTN management using single-dose combination medications (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Mbuthia, Willis and Reich2025), an effective approach to decrease pill burden (An et al. Reference An, Derington, Luong and Jackevicius2020; World Health Organization 2023b). It revealed significant knowledge gaps among healthcare providers, with some expressing reluctance to prescribe the combination pill due to insufficient familiarity with guidelines (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Mbuthia, Willis and Reich2025). Supply chain challenges resulted in medication expiration due to demand miscalculations, accentuating the complex interplay between policy development, provider education, and system capacity, besides individual-level factors.

C. Social barriers to adherence

Reported barriers to HTN treatment adherence also stemmed from social and cultural issues, including family dynamics, which could influence an individual’s attitude and ability to follow prescribed regimens. Adherence was particularly difficult when patients’ beliefs, social interactions, and living conditions conflicted with medical advice. Social barriers were grouped into two subcategories: (1) cultural and religious beliefs, (2) social influences and family dynamics.

Cultural and religious beliefs: Some studies reported that many individuals turned to traditional medicine as an alternative to prescribed medications in the region, especially if these practices were culturally ingrained (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Rachlis et al. Reference Rachlis, Naanyu, Wachira and Braitstein2016; Galson et al. Reference Galson, Staton, Karia and Stanifer2017; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Gebrezgi et al. Reference Gebrezgi, Trepka and Kidane2017; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Green et al. Reference Green, Lynch, Nanyonga and Heller2020; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021; Hussien et al. Reference Hussien, Muhye, Abebe and Ambaw2021; Sundararajan et al. Reference Sundararajan, Alakiu, Ponticiello and Peck2023). Additionally, religious beliefs (Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Kisigo et al. Reference Kisigo, Mcharo, Robert, Peck, Sundararajan and Okello2022) and practices, such as fasting, sometimes interfered with medication schedules or dietary guidelines necessary for managing HTN (Hussien et al. Reference Hussien, Muhye, Abebe and Ambaw2021). Moreover, cultural stigma surrounding the use of daily medications, particularly for chronic conditions like HTN, deterred individuals from adhering to prescribed treatment, as medications were perceived by some as a sign of weakness or failure to heal naturally. In some studies, HTN patients described being afraid that others might mistake them for taking antiretroviral medications for HIV, a highly stigmatised condition (Gebrezgi et al. Reference Gebrezgi, Trepka and Kidane2017; Najjuma et al. Reference Najjuma, Brennaman, Nabirye and Muhindo2020). Holding a belief in a ‘complete cure’, rather than accepting the need for ongoing treatment, also discouraged adherence (Liwa et al. Reference Liwa, Roediger, Jaka and Peck2017).

Social Influences and family dynamics: Social stigma around chronic diseases like HTN prevented some individuals from openly discussing their condition or seeking support, leading to a reluctance to adhere to treatment plans (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Rachlis et al. Reference Rachlis, Naanyu, Wachira and Braitstein2016; Gebrezgi et al. Reference Gebrezgi, Trepka and Kidane2017; Najjuma et al. Reference Najjuma, Brennaman, Nabirye and Muhindo2020). Additionally, peer pressure or community norms appeared to minimise the seriousness of HTN in the region and could discourage medication use, especially in communities where non-medical treatments were more socially accepted (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016; Rachlis et al. Reference Rachlis, Naanyu, Wachira and Braitstein2016; Abaynew & Hussien Reference Abaynew and Hussien2021; Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Zeleke, Sergo, Misganaw and Mekonnen2023; Hailu et al. Reference Hailu, Yigezu, Gutema and Hordofa2025). Alcohol or substance use also interfered with medication adherence and worsened HTN (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016), as these behaviours often hampered self-efficacy and contradicted medical advice. Competing social obligations (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Vedanthan, Kamano and Inui2016), such as work or caregiving responsibilities, made it difficult for individuals to prioritise their health, leading to missed medications or appointments. Lack of social support, whether from family members, friends, or the community, also hindered adherence. Some HTN patients described having no one to remind or encourage them to take their medication regularly (Galson et al. Reference Galson, Pesambili, Vissoci and Stanifer2023; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023; Hailu et al. Reference Hailu, Yigezu, Gutema and Hordofa2025). Furthermore, the inability of individuals with HTN to prepare their own foods that are low in salt intake and societal expectations of men not to cook added another layer to non-adherence and precluded them from following lifestyle modifications for HTN management (Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Zeleke, Sergo, Misganaw and Mekonnen2023). Peer pressure during social events to consume offered foods outside of their recommended diet further reinforced non-adherence (Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Zeleke, Sergo, Misganaw and Mekonnen2023).

Living in unsafe environments precluded individuals with HTN from outdoor activities, discouraging exercise (Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Zeleke, Sergo, Misganaw and Mekonnen2023), an important part of managing HTN (Hussien et al. Reference Hussien, Muhye, Abebe and Ambaw2021). Additionally, residing in areas with inadequate healthcare infrastructure, such as rural locations with few healthcare facilities or pharmacies, made it harder for patients to access medications, follow up with their care, or seek health advice, further complicating their ability to adhere to treatment (Isangula et al. Reference Isangula, Seale, Nyamhanga, Jayasuriya and Stephenson2018; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018). Together, these social barriers created a complex web of influences that hindered HTN treatment adherence.

Six studies were conducted with patients living with both HTN and HIV (Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Minja, Wanda and Watt2020; Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Wanda, Galson, Thielman, Mmbaga and Watt2021; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Tusubira, Nakirya and Ssinabulya2020; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Ayebare et al. Reference Ayebare, Siu, Kaawa-Mafigiri and Katahoire2025; Semitala et al. Reference Semitala, Ayebare, Kiggundu and Katahoire2025). Findings from these studies largely corroborated the findings from the other studies, but they also highlighted major gaps between the management of communicable and non-communicable diseases. Patients in these studies lauded their HIV care but were dissatisfied with their HTN care, along with a lack of care integration for the two conditions (Manavalan et al. Reference Manavalan, Minja, Wanda and Watt2020; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Tusubira, Nakirya and Ssinabulya2020; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Semitala et al. Reference Semitala, Ayebare, Kiggundu and Katahoire2025). Some patients living with HIV reported prioritising adherence to their antiretroviral medications over their HTN medications, emphasising the need for HTN health literacy, including its chronic nature and the complications that can arise as a result of uncontrolled blood pressure (Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021). Additionally, one of these six articles explored HTN management during COVID-19, highlighting patients’ competing financial needs, exacerbation of existing healthcare access barriers (such as medication shortages, healthcare worker availability, and patient healthcare-seeking behaviour), along with fear of being infected with COVID-19 during the pandemic (Ayebare et al. Reference Ayebare, Siu, Kaawa-Mafigiri and Katahoire2025).

Facilitators to HTN treatment adherence

Reported facilitators are also categorised into individual, structural, and social levels.

A. Individual facilitators to adherence

At the individual level, trust (Isangula et al. Reference Isangula, Seale, Nyamhanga, Jayasuriya and Stephenson2018) in healthcare providers and increased awareness of patients’ HTN status and treatment options were shown to be fundamental drivers of treatment adherence (Abaynew & Hussien Reference Abaynew and Hussien2021; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Endrias et al. Reference Endrias, Geta, Desalegn and Nigussie2024). When patients trusted their healthcare providers, they were more likely to follow treatment plans because they believed in the effectiveness of the prescribed regimen. Increased awareness about HTN (Gebrezgi et al. Reference Gebrezgi, Trepka and Kidane2017; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Nanyonga et al. Reference Nanyonga, Spies and Nakaggwa2022; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Peoples, Ostbye and Yan2023; Endrias et al. Reference Endrias, Geta, Desalegn and Nigussie2024), patients’ accurate perceptions of HTN risks and complications (Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018), acceptance of HTN diagnosis (Willis et al. Reference Willis, Mbuthia, Gichagua and Murphy2025), and awareness of the benefits of treatment (Najjuma et al. Reference Najjuma, Brennaman, Nabirye and Muhindo2020) empowered individuals to take ownership of their health, making them more committed to adhering to prescribed treatments. These personal factors shape patients’ attitudes toward treatment, influencing their decision-making and behaviour.

B. Structural facilitators to adherence

On the structural level, consistent availability of medications and skilled providers (Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Green et al. Reference Green, Lynch, Nanyonga and Heller2020; Najjuma et al. Reference Najjuma, Brennaman, Nabirye and Muhindo2020; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023) facilitated patients’ adherence to their treatment by providing patients with the resources they needed to stay on track with treatment. Access to essential medicines, affordability of care and a reliable supply of medications contributed to HTN treatment adherence and prevented interruptions in treatment (Green et al. Reference Green, Lynch, Nanyonga and Heller2020; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023). Similarly, proximity of health facilities (Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Endrias et al. Reference Endrias, Geta, Desalegn and Nigussie2024), transport vouchers covering patients’ transportation fees (Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Garden, Nanyonga and Heller2022) were highly valued. At the provider level, health education and counselling provided during HTN care (Abaynew & Hussien Reference Abaynew and Hussien2021; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021) and strong patient-provider relationships (Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021) were critical for facilitating consistent monitoring, guidance, and adjustments in the treatment plan.

Access to providers for follow-up appointments or advice further improved adherence to treatment plans. Financial facilitators were also important, including waived fees (Hussien et al. Reference Hussien, Muhye, Abebe and Ambaw2021), better insurance coverage (Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Hussien et al. Reference Hussien, Muhye, Abebe and Ambaw2021; Kisigo et al. Reference Kisigo, Mcharo, Robert, Peck, Sundararajan and Okello2022; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023), and reduced financial barriers such as free supply of medications through government support (Gebrezgi et al. Reference Gebrezgi, Trepka and Kidane2017). Additionally, synchronised medication refills for HIV and HTN were reported to promote adherence to HTN treatment, enabling access to medications while decreasing required clinic visits and transportation fees (Semitala et al. Reference Semitala, Ayebare, Kiggundu and Katahoire2025). Holistic structural support removed practical barriers to adherence, enabling patients to stay on track with their treatment.

C. Social facilitators to adherence

Social facilitators were reported to be important in supporting HTN treatment adherence across multiple studies. Social support (Gebrezgi et al. Reference Gebrezgi, Trepka and Kidane2017; Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Najjuma et al. Reference Najjuma, Brennaman, Nabirye and Muhindo2020; Abaynew & Hussien Reference Abaynew and Hussien2021; Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Olds, Nuwagaba, Okello and Haberer2021; Kisigo et al. Reference Kisigo, Mcharo, Robert, Peck, Sundararajan and Okello2022; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Garden, Nanyonga and Heller2022; Mohamed et al. Reference Mohamed, Macharia and Asiki Gand Gill2023; Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Njuguna, Koros and Akwanalo2023; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Peoples, Ostbye and Yan2023; Endrias et al. Reference Endrias, Geta, Desalegn and Nigussie2024; Willis et al. Reference Willis, Mbuthia, Gichagua and Murphy2025), including encouragement and reminders to follow one’s treatment plan from family, friends, and community members, helped patients feel accountable and motivated (Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Kisigo et al. Reference Kisigo, Mcharo, Robert, Peck, Sundararajan and Okello2022; Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Njuguna, Koros and Akwanalo2023); Endrias et al. Reference Endrias, Geta, Desalegn and Nigussie2024; Willis et al. Reference Willis, Mbuthia, Gichagua and Murphy2025), along with good coping strategy (Willis et al. Reference Willis, Mbuthia, Gichagua and Murphy2025), including stress management (Endrias et al. Reference Endrias, Geta, Desalegn and Nigussie2024). Emotional support provided reinforcement to help patients stay consistent with their treatment, especially during difficult moments or periods of uncertainty. Reminder systems, whether from family members or technology (e.g., mobile apps), helped reduce forgetfulness and take medications as scheduled (Musinguzi et al. Reference Musinguzi, Anthierens, Nuwaha, Van Geertruyden, Wanyenze and Bastiaens2018; Edward et al. Reference Edward, Campbell, Manase and Appel2021; Muddu et al. Reference Muddu, Ssinabulya, Kigozi and Semitala2021; Kisigo et al. Reference Kisigo, Mcharo, Robert, Peck, Sundararajan and Okello2022; Nanyonga et al. Reference Nanyonga, Spies and Nakaggwa2022; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Garden, Nanyonga and Heller2022; Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Njuguna, Koros and Akwanalo2023; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Peoples, Ostbye and Yan2023; Willis et al. Reference Willis, Mbuthia, Gichagua and Murphy2025). These external reminders created a structure around treatment that increased the likelihood of adherence.

Discussion

This qualitative scoping review highlighted critical contextual barriers and facilitators to HTN treatment adherence in East Africa across individual, structural, and social levels. Cognitive and behavioural factors, such as lack of HTN literacy and limited risk perception, were often cited as individual barriers to adherence. Other studies have similarly emphasised the importance of patients’ knowledge and beliefs as key determinants of adherence (Brathwaite et al. Reference Brathwaite, Hutchinson, McKee, Palafox and Balabanova2020; Sorato et al. Reference Sorato, Davari, Kebriaeezadeh, Sarrafzadegan, Shibru and Fatemi2021; Bhattarai et al. Reference Bhattarai, Bajracharya, Shrestha and Sen2023). Mental health issues, including stress, anxiety, depression, and forgetfulness, were frequently reported as contributing to non-adherence, along with fear, particularly fear of stigma associated with living with HIV, a highly stigmatised condition in the region. Trust in the healthcare system and providers, and increased awareness of HTN and its treatment efficacy, were identified as strong facilitators. Patients who felt engaged and empowered were more likely to continue with their treatment plans, indicating the need for a clearer understanding of the purpose and benefits of HTN medications and lifestyle modifications.

Structural factors such as inconsistent healthcare delivery, lack of access, and financial constraints were prevalent. These findings align with other reviews, which reported that lack of stable healthcare access led to disruptions in treatment and gaps in adherence (Brathwaite et al. Reference Brathwaite, Hutchinson, McKee, Palafox and Balabanova2020; Sorato et al. Reference Sorato, Davari, Kebriaeezadeh, Sarrafzadegan, Shibru and Fatemi2021; Bhattarai et al. Reference Bhattarai, Bajracharya, Shrestha and Sen2023). Healthcare policies that emphasised medication pricing were found to hinder adherence, while policies enabling reduced medication fees or financial support were seen as facilitators. Additionally, social norms surrounding health behaviours and attitudes towards HTN treatment were identified as key determinants, similar to studies done in other global and regional regions (Miezah & Hayman Reference Miezah and Hayman2024). Addressing these cultural barriers through education and community engagement could help shift social attitudes and improve adherence. Social support and reminders emerged as important facilitators, particularly for those struggling with forgetfulness or mental health challenges. These findings provide insights into the multifaceted challenges faced by HTN patients in East Africa and underscore the importance of identifying local factors and using local ways to enhance adherence in the region.

These findings indicate that adherence in the East African region is shaped by intertwined individual, structural, and social factors that cannot be considered in isolation. For example, a motivated patient may still struggle with adherence if medications are unaffordable or unavailable (stock-outs) even with a policy for ‘free care’ in place. Social support can reinforce self-management behaviours learned from providers, while cultural beliefs may shape how patients adhere to their treatment.

Additionally, the included study that examined HTN care for people living with HIV during COVID-19 revealed that pandemic conditions exacerbated pre-existing challenges (Ayebare et al. Reference Ayebare, Siu, Kaawa-Mafigiri and Katahoire2025). This finding aligns with prior reviews showing how external crises can intensify existing barriers to healthcare access (Okereke et al. Reference Okereke, Ukor, Adebisi and Lucero-Prisno2021; Pujolar et al. Reference Pujolar, Oliver-Anglès, Vargas and Vázquez2022; Emami et al. Reference Emami, Lorenzoni and Turchetti2024), suggesting that effective management of chronic diseases requires health system strengthening to maintain care continuity during emergencies. The study addressing barriers to HTN management using fixed-dose combination (FDC) (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Mbuthia, Willis and Reich2025) showed that implementation barriers may still persist even when evidence-based solutions exist (An et al. Reference An, Derington, Luong and Jackevicius2020), reinforcing that addressing HTN management barriers requires comprehensive approaches to enhance adherence behaviours.

Implications for healthcare practice

The findings of this scoping review have significant implications for clinical practice. Addressing challenges related to HTN treatment adherence requires a comprehensive, multi-level strategy that integrates individual, structural, and social factors. At the individual level, healthcare providers must consider the psychosocial context of each patient and offer personalised support. This may involve addressing mental health concerns, simplifying complex medication regimens, and offering tailored interventions to improve adherence. This might appear as a tall order in the face of a shortage of healthcare providers. However, task sharing with non-professionals, trained local community members in HTN treatment and adherence, and using telehealth to help increase HTN literacy could help mitigate this problem (Inagaki et al. Reference Inagaki, Matsushita, Appel, Perry and Neupane2024). Additionally, patient education plays a crucial role in this process, particularly in helping patients understand the importance of adherence and the risks associated with non-adherence.

At the structural level, healthcare systems should prioritise the accessibility and affordability of medications. Policies aimed at reducing financial barriers, such as subsidised medications or sliding-scale fees for patients with limited financial resources, can significantly enhance adherence rates. Simplifying regimens through strategies such as ‘single-pill combination therapy’ (An et al. Reference An, Derington, Luong and Jackevicius2020; Bruyn et al. Reference Bruyn, Nguyen, Schutte, Murphy, Perel and Webster2022) along with clearer, consistent instructions could help minimise confusion and foster greater adherence, offering a more manageable solution. Community-based efforts towards bringing care closer to patients, using task sharing with local resources, could help alleviate some of the burden associated with distances and long waits. Additionally, a combination of trained local providers with mobile health could offer practical reminders to patients to enhance adherence. Moreover, synchronised medication refills for HIV and HTN could help mitigate barriers related to repeated visits to health facilities, thereby reducing half patients’ travel time to clinic, wait times, and transport costs.

At the social level, healthcare systems should promote the involvement of family members and peers in the treatment process. Encouraging family-centred care and developing community-based support networks can provide the social reinforcement needed for patients to stay committed to their treatment plans (Naanyu et al. Reference Naanyu, Njuguna, Koros and Akwanalo2023). Moreover, culturally sensitive interventions are essential to ensure that adherence strategies are aligned with patients’ cultural beliefs and values, ensuring their effectiveness and relevance (Miezah & Hayman, Reference Miezah and Hayman2024).

Implications for future research

This area of research has been sparse in several East African nations, as only 5 of the 13 included countries are represented. There is a need for more research in the region. Future research should focus on exploring the intersection of individual, structural, and social factors in East Africa. Studies that integrate qualitative and quantitative methods could offer a more comprehensive understanding of adherence patterns and the effectiveness of various interventions. Future reviews should also seek to identify studies that have attempted to improve medication adherence with interventions addressing all three levels simultaneously, leveraging self-efficacy, healthcare system facilitation, and social support. Additionally, there is a need for more research on the role of technology and digital health tools in improving HTN treatment medication adherence, as well as the integration of community health workers, particularly among those with limited access to healthcare in the region. More studies are also needed to understand how best to integrate the management of both communicable and non-communicable diseases due to existing dissonance in managing both diseases in the region.

Implication for policy

Considering the interplay of factors influencing adherence in this review, the findings provide the opportunity for future policy initiatives to address structural barriers to adherence. Such policies could aim at ensuring reliable access to medications by reducing stock-outs and improving supply chain management, since interruptions in treatment can undermine adherence despite patients’ motivation and social support. Additionally, strengthening HTN treatment guidelines and provider training could lead to more consistent, evidence-based care, which could enhance patients’ adherence.

Strengths and weaknesses

In this scoping review, the team described the findings of qualitative research, which offered rich, contextual insights representing the lived experiences of patients and detailed recommendations of patients, providers, and others to improve care, a finding not available from quantitative research alone. Additionally, the diversity of participant types provides a more comprehensive understanding of local barriers and facilitators to HTN treatment adherence in the region. While this review provides valuable insights into the barriers and facilitators of HTN treatment adherence in the East African region, several limitations should be noted. The small sample sizes in some studies may hinder the generalizability of the findings. Unpublished research and manuscripts not written in English were excluded from this review as they were not feasible for this team. Moreover, this review only contained articles from 5 of the 13 countries in East Africa, which may have led us to miss valuable perspectives of many people in the region. With adherence being a global problem and uncontrolled HTN more prevalent in low-resource settings, there is a need for more research in the other East African countries.

Conclusion

This qualitative scoping review underscores the complex interplay of individual, structural, and social factors associated with HTN treatment adherence in East Africa. Addressing these challenges requires culturally sensitive healthcare interventions, community engagement, and the provision of robust social support systems leveraging local resources, including community health workers, to help increase HTN literacy in the face of a shortage of providers in the region. Additionally, focusing on mental health challenges to increase treatment adherence, addressing HIV-related stigma associated with daily medication intake in the region, along with enforcing policy guidelines to increase access to essential medications for HTN, could help mitigate obstacles at all three levels towards improving patients’ health outcomes. Patient-centred care, structural reforms, and social support are essential in overcoming adherence challenges. Future research should continue to explore multi-level approaches and assess the effectiveness of interventions in varied contexts, particularly in resource-limited settings using community-participatory approaches, to further improve HTN treatment adherence.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standard

We assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.