Introduction

2016 proved to be more turbulent than 2015 in Bulgaria, with presidential elections, a cabinet resignation and a lot of speculation about the foreign policy orientation of the country. The Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) re-asserted itself on the political stage, the nationalist bloc consolidated, while the traditional right disintegrated.

Election report

Presidential elections

Presidential elections took place on 6 and 13 November 2016. Twenty-two candidate pairs (president and vice-president) registered for the first round of the elections and ran in a relatively short but dramatic campaign. What caused much speculation during the campaign was the delayed announcement of the candidacy of GERB. For several months before the nomination polling results consistently indicated that a GERB nominee would almost certainly become the next president, capitalising on GERB's dominance and popularity. GERB's main opponent, the Socialists (BSP), chose to tap into the anti-establishment attitudes of the electorate by fielding a candidate with virtually no experience in politics. General Rumen Radev (officially nominated by an initiative committee) ran together with Iliana Iotova, an acting socialist MEP, former deputy, BSP spokesperson and popular television journalist.

Finally, in early October, Tsetska Tsacheva, the Chairwoman of Parliament since 2009, a lawyer and a leading GERB politician, was put forward by Prime Minister Borissov as the antipode to the BSP candidate. As the campaign unfolded, Tsacheva, herself not a popular political figure in the country, faced tough competition from three dominant male candidates: Radev; the candidate of the nationalist platform Krasimir Karakachanov; and the Bulgarian ‘Trump’, businessman Veselin Mareshki. As a result, the GERB campaign lost momentum, and ultimately reached a parity with the BSP in the weeks running up to the elections. The main issues in the campaign were relations with Russia, the refugee/migrant crisis and the protection of national interests.

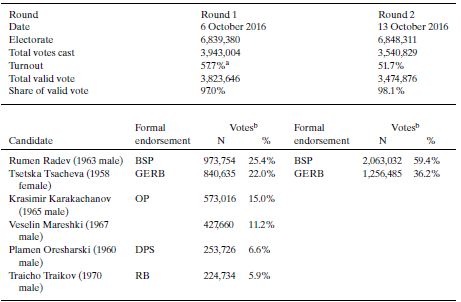

At the first round, with voter turnout at 58 per cent Radev came first, winning 25 per cent of the popular vote, while Tsacheva finished second, 130,000 votes behind. At the second round, at which almost 52 per cent of eligible voters turned out, a majority supported the opposition candidate and General Radev was elected President of the Republic, with 59 per cent of the vote.

Table 1. Elections for President in Bulgaria in 2016

Notes: aOur calculations differ slightly from the turnout rates announced officially by the Central Election Commission.

b There is an option in the ballot ‘I don't support any of the nominated’, which got 214,094 votes (5.6%) in the first round and 155,411 (4.5%) in the second round.

Source: Central Election Commission website, 2016 Presidential Elections, 1st round https://results.cik.bg/pvrnr2016/tur1/president/index.html

Referendum

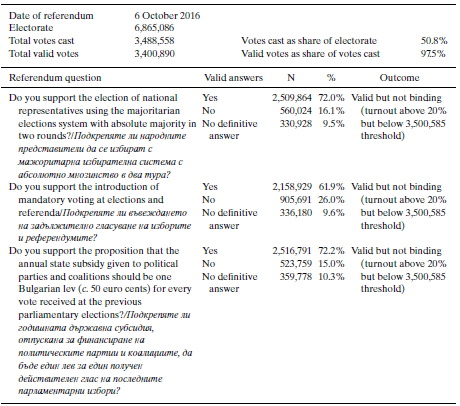

A national referendum on changes in the electoral law and party financing was held parallel to the presidential vote. The referendum was initiated by Slavi Trifonov, a popular host of a late night television show. Having followed the procedures for a popularly initiated referendum, the proposal asked the Bulgarian people to vote on three questions, including changing the electoral system to a ‘majoritarian system with absolute majority in two rounds’; the introduction of mandatory voting in national elections and referenda; and a decrease in the amounts of state subsidies allocated to parties by the national budget.

The national referendum barely missed the threshold needed to make its decision binding. It fell short of about 13,000 votes to reach the necessary threshold – the number of votes cast in the previous national parliamentary elections. In spite of this, the consequences of the referendum are likely to be substantial as 72 per cent voted in favour of the introduction of a majoritarian system. The National Assembly is legally bound to consider the propositions and given the public predisposition is likely to move the electoral legislative framework in this direction.

Table 2. Results of the referendum on changes in the electoral law and party financing in Bulgaria in 2016

Source: Central Election Commission website, 2016 Referendum Results https://results.cik.bg/pvrnr2016/tur1/referendum/index.html

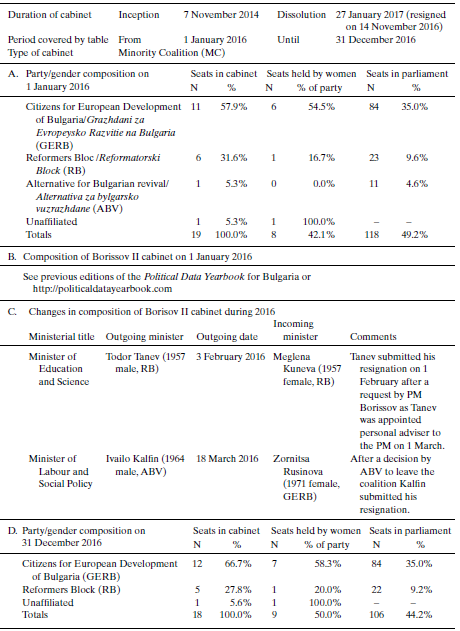

Cabinet report

Tensions in the three-party minority coalitionFootnote 1 of Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB), Reformists Bloc (RB) and Alternative for Bulgarian Revival (ABV) – already noted in 2015 – increased in the first half of 2016. Early on in the year, personnel changes in the composition in the cabinet indicated tensions within the Reformists Bloc. Its Minister of Education Tanev resigned on 3 February and was replaced by Vice Prime Minister Meglena Kuneva, party leader of Movement Bulgaria of the Citizens (DBG), a constituent part of RB. In March, Democrats for Strong Bulgaria (DSB), another constituent party of RB, openly joined the opposition. In May 2016, in clear anticipation of the presidential elections in November 2016, the left-wing coalition partner ABV left the governing coalition, and its minister Ivaylo Kalfin (Minister of Labour and Social Policy) resigned and was replaced by Zornitsa Russinova (independent). This was seen as the first definite sign that the coalition formula of the cabinet needed to change and it resulted in negotiations to incorporate cabinet ministers of the support party Patriotic Front. Cabinet reshuffling was planned for after the presidential elections, and expectations were that the share of RB ministerial portfolios would be decreased in accordance with its decreasing parliamentary support for the cabinet and the anticipated poor performance at the presidential elections.

A decline in the popularity of Borissov's cabinet was noted in June 2016: satisfaction with the cabinet was down 4 percentage points from February to June, but in contrast dissatisfaction with Prime Minister Borissov was up 5 percentage points, reaching over 40 per cent for the first time since Borissov took office in 2014 (Alpha Research 2016). This was attributed not so much to dissatisfaction with the work of the cabinet, but more so with the intra-coalition problems, tensions and scandals that have accompanied the cabinet since 2015.

During the campaign for presidential elections and especially in the period between the two rounds, Prime Minister Borissov made a clear commitment that he would resign if the GERB candidate failed to win. The landslide victory of the candidate backed by the Socialists at the second round indicated that a considerable proportion of supporters of the coalition parties voted for the opposition candidate. This led to the resignation of Borissov on 14 November, even though the cabinet could de facto still rely on the support of more than 140 MPs, with 121 needed for majority decisions (GERB, RB, Patriotic Front, Bulgarian Democratic Centre and even ATAKA). With 38 MPs the Socialists were practically unable to form a coalition and they declined to attempt to do so. As Reformist Bloc, Patriotic Front, Bulgarian Democratic Centre and ATAKA declared their willingness to work out a new coalition, the president gave the Reformists two weeks to make a last attempt to form a cabinet. This did not prove successful because GERB and Borissov were determined to push for early elections. On 21 December, with only a few weeks remaining of his tenure, President Plevneliev decided to leave it to the new president to dismiss the parliament and appoint a caretaker government in January 2017.

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Borissov II in Bulgaria in 2016

Source: Council of Ministers website: http://www.government.bg/ (2016).

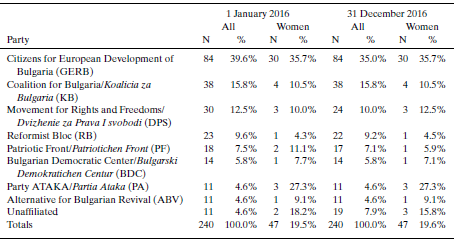

Parliament report

Parliamentary life reflected the gradual change in the format of the coalition. In February 2016, a vote of no confidence was introduced by BSP, DPS and two unaffiliated MPs because of the cabinet's alleged failure in the area of healthcare reform. Not having enough support from other parliamentary factions, the vote failed with only 80 votes in support of the no-confidence motion. While further votes were discussed and planned, the resignation of Borissov pre-empted further parliamentary actions of control. Parliamentary party groups remained somewhat stable with the major exception of DPS, which lost quite a few members following the expulsion of Mestan.

There was a visible consolidation between the two nationalistic parties – Patriotic Front and ATAKA, with the latter moving from a radical opposition to a support party. After the presidential elections PF and ATAKA tried to build on the good performance of its candidates – Karakachanov (PF) and Notev (ATAKA) had finished third at the elections – and set out to become a ‘kingmaker’ in parliament. After Borissov's resignation they actively promoted the option to form a new GERB cabinet (led by Borissov or another candidate). RB stood firmly behind Borissov and were only willing to support a new cabinet with him as prime minister. Both options were unacceptable for GERB as they did not guarantee cabinet stability and the party opted for pre-term elections aiming to preserve its dominant position in the parliament – be it in the government or in opposition.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of parliament (Narodno Subranie) in Bulgaria in 2016

Source: National Assembly Archive: http://www.parliament.bg/bg/archive/51/2/

Political party report

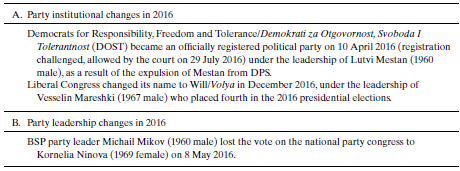

Three substantial changes happened in Bulgaria's party landscape in 2016. First, after a leadership reshuffle in the DPS, a contender for the votes of the Turkish minority emerged in early 2016. Lutvi Mestan, the former DPS leader who had been expelled from the party in late 2015 established Democrats for Responsibility, Freedom and Tolerance (DOST). While at the beginning the courts refused to register the party, arguing that the use of the abbreviation DOST (friend in Turkish) violated the constitutional ban on ethnic parties, ultimately the registration was allowed by the Supreme Court of Cassation. The party officially backed a different presidential candidate in the October elections than the DPS, and using that vote as an indicator, it appeared able to attract a substantial amount of the DPS votes in the country and particularly its supporters among the Bulgarian Turkish diaspora in Turkey. The role of DPS is visibly diminishing as the main party objective for 2016 was to retain its monopoly on the ethnic Turkish and Muslim vote.

Second, a new contender with a consumer-populist profile emerged when Vesselin Mareshki ran in the presidential elections and managed to win 11 per cent of the votes. Mareshki had been active in national and local politics since much earlier, capitalising on his major economic presence in the region of Varna. Gradually expanding his ownership of two business chains – pharmacies and gas stations – he appealed for political support by offering lower prices of both medicines and gasoline to the Bulgarian population. Aspiring to be the ‘Bulgarian Donald Trump’, Mareshki changed the name of his party to Will (Volya) in December 2016 following his good performance at the presidential election. Volya is clearly a business party, based on the Mareshki company's reach into the economy of the country.

Third, 2016 witnessed the beginning of the disintegration of the Reformists Bloc, the coalition of traditional centre-right parties. Disagreements among its constituent parts were evident early on in the year, and while the Bloc ran a joint presidential candidate in October, by the end of 2016 it became clear that there were at least two irreconcilable camps, which were going to go their own ways come the early elections in 2017. Some of the RB parties explicitly defended the government and the strategy to maintain a coalition with GERB, while others joined the parliamentary opposition and strongly criticised the politics of Borissov II.

Table 5. Changes in political parties in Bulgaria in 2016

Sources: 24 Chassa: https://www.24chasa.bg/novini/article/5901404; Darik News: https://dariknews.bg/novini/bylgariia/korneliq-ninova-e-noviqt-lider-na-bsp-1573586

Institutional change report

The legal electoral framework was amended substantially in 2016 while groundwork for even more fundamental changes was laid as well. In April parliament approved several major changes: introduced mandatory voting, introduced the option ‘vote against all candidates’, and banned local coalitions among parties which are in different coalitions nationally. The legislature also tried to limit the number of voting sections in foreign countries, but after a strong civil society reaction from the Bulgarian diaspora, the limit was repealed. Despite disapproval from both the opposition and some of the coalition partners, mandatory voting was introduced in order to meet the strong demand of the Patriotic Front, a support party holding the key to government stability. The mandatory nature of the vote implied a punishment of being removed from the voting registry after two repeated failures to vote, and the need to re-register in order to vote again. Further changes might be anticipated following the national referendum described in the Election report.

Issues in national politics

Political life in Bulgaria became certainly less predictable in 2016. The instability of the coalition increased over the course of the year and presidential elections signaled the return of the Socialist party as a major challenger to GERB's dominance of the political process. Economically, the country continued to be the poorest in the EU, while macroeconomic indicators improved gradually.

Issues of national security became more relevant in the context of the refugee/migrant crisis, developments in Turkey and Russia's more prominent political role. Nationalist political parties Patriotic Front and ATAKA continued to be a stable presence in the country's political life and had a strong anti-minority and anti-migrant position, but as the other parties also adopted a strong patriotic stance the influence of the nationalistic bloc did not increase.

One of the hottest issues that framed the political debate and strongly influenced the presidential election outcome was the rivalry between two Bulgarian candidates for the position of UN Secretary General. The BSP-DPS government of Plamen Oresharski nominated Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO (former BSP MP and Deputy Foreign Minister). In early September 2016 she proved to have limited chances of being elected. In the middle of the voting procedure on 28 September, as Bokova dropped to sixth (out of nine) position, Prime Minister Borissov withdrew the government's support for Bokova and put foreward a new Bulgarian candidate – European Commission Vice-President Kristalina Georgieva. It was a high-risk decision as the presidential elections were forthcoming and Georgieva had little chance of being elected. Ultimately, Antonio Gutieresh was elected Secretary General and the results were humiliating for Georgieva and, respectively, Borissov. During the parliamentary debates and presidential campaign in October the BSP played up their claim that GERB is unable to defend Bulgarian national interest in its foreign policy.