1 Introduction

The investigation of ultrafast processes in physics, occurring on femtosecond and attosecond timescales[ Reference Krausz and Ivanov1], demands laser sources capable of delivering ultrashort pulses with high peak power and precisely controlled electric fields[ Reference Shestaev, Hoff, Sayler, Klenke, Hädrich, Just, Eidam, Jójárt, Várallyay, Osvay, Paulus, Tünnermann and Limpert2– Reference Hassan, Luu, Moulet, Raskazovskaya, Zhokhov, Garg, Karpowicz, Zheltikov, Pervak, Krausz and Goulielmakis5]. High peak power, exceeding a few hundred gigawatts, is crucial for driving high harmonic generation (HHG) and enabling efficient attosecond pulse generation[ Reference Li, Lu, Chew, Han, Li, Wu, Wang, Ghimire and Chang6, Reference Ghimire and Reis7]. High repetition rates are also vital, as they facilitate rapid data acquisition and enhance signal-to-noise ratios. Furthermore, carrier-envelope phase (CEP) stabilization is essential for applications requiring precise control over the generated light field, such as the generation of isolated attosecond pulses[ Reference Witting, Osolodkov, Schell, Morales, Patchkovskii, Šušnjar, Cavalcante, Menoni, Schulz, Furch and Vrakking8, Reference Midorikawa9]. This scientific challenge is addressed by several attosecond beamlines[ Reference Kretschmar, Hadjipittas, Major, Tümmler, Will, Nagy, Vrakking, Emmanouilidou and Schütte10, Reference Viotti, Seidel, Escoto, Rajhans, Leemans, Hartl and Heyl11], including the development of the ELI-ALPS HR1 laser system[ Reference Hädrich, Shestaev, Tschernajew, Stutzki, Walther, Just, Kienel, Seres, Jójárt, Bengery, Gilicze, Várallyay, Börzsönyi, Müller, Grebing, Klenke, Hoff, Paulus, Eidam and Limpert12].

The HR1 system is an exceptional laser system with parameters suitable for a wide variety of attosecond pump–probe studies. To address potential repetition rate effects in experiments, for example, thermal effects at high repetition rates or renewal of a target hit repeatedly, the system allows for adjustable repetition rate operation while maintaining output pulse energy, beam quality and other beam parameters. However, a key limitation of the HR1 system, which ultimately motivated the development of the HR Alignment system, is the lack of repetition rate tunability, which is a consequence of the ytterbium-doped fiber amplifier architecture. Due to the relatively long time of energy storage of the amplifying medium the decrease of repetition rate before amplification would significantly increase the energy of a single amplified pulse, potentially leading to saturation, gain distortion or even nonlinear effects that can lead to damage of the amplifier. Furthermore, the continuous pumping at lower repetition rates would lead to increased amplified spontaneous emission (ASE), degrading the signal-to-noise ratio. On the other hand, repetition rate control after amplification (e.g., a Pockels cell) is challenging regarding the high average power and requirement of low CEP noise contribution. For this reason, moderate average power systems are ideal candidates for applications, where tunability is a key feature.

Achieving few-cycle pulse duration with millijoule-level energy typically involves spectral broadening in a nonlinear medium followed by temporal compression. Various techniques have been employed for this purpose, including utilizing the nonlinearity of thin silica plates[ Reference Lu, Witting, Husakou, Vrakking, Kung and Furch13– Reference Tóth, Nagymihály, Seres, Lehotai, Csontos, Tóth, Geetha, Somoskői, Kajla, Abt, Pajer, Farkas, Mohácsi, Börzsönyi and Osvay15], gas-filled hollow-core fibers (HCFs)[ Reference Hädrich, Shestaev, Tschernajew, Stutzki, Walther, Just, Kienel, Seres, Jójárt, Bengery, Gilicze, Várallyay, Börzsönyi, Müller, Grebing, Klenke, Hoff, Paulus, Eidam and Limpert12, Reference Nagy, Hädrich, Simon, Blumenstein, Walther, Klas, Buldt, Stark, Breitkopf, Jójárt, Seres, Várallyay, Eidam and Limpert16] and multi-pass cells (MPCs)[ Reference Lavenu, Natile, Guichard, Zaouter, Delen, Hanna, Mottay and Georges17– Reference Müller, Buldt, Stark, Grebing and Limpert19], which are particularly well-suited for nonlinear compression of short pulses[ Reference Tsai, Liang, Tsai, Lai, Lin and Chen20– Reference Pi, Kim and Goulielmakis22]. Recently, 6.1 fs pulses were achieved by HCF compression with an energy throughput of 72%[ Reference Ivanov, Doiron, Scaglia, Abdolghader, Tempea, Légaré, Trallero-Herrero, Vampa and Schmidt23]. In a separate advance, the combination of Ti:sapphire technology with an MPC has produced record short 3.8 fs pulses using this compression technique[ Reference Daniault, Kaur, Gallé, Sire, Sylla and Lopez-Martens24]. While these methods are widely used in ultrashort pulse laser systems, these systems often lack simultaneous CEP stabilization and flexible repetition rate tunability.

To address the wide range of repetition rate demand, we have made a (tunable) high-repetition-rate, CEP-stable laser system based on the combination of a very stable, tunable, commercially available ytterbium-doped potassium gadolinium tungstate (Yb:KGW) chirped pulse amplification (CPA) system (Pharos, Light Conversion)[ 25] and MPC based post-compression stages to be a robust toolset for experiments. The Pharos front-end offers exceptional flexibility, delivering 300 fs pulses with multi-mJ energy in the repetition rate range of 0.01–10 kHz, providing up to 20 W average power, and an excellent Gaussian beam profile. Exploiting our experience gained during the development of the HR1 laser[ Reference Hädrich, Shestaev, Tschernajew, Stutzki, Walther, Just, Kienel, Seres, Jójárt, Bengery, Gilicze, Várallyay, Börzsönyi, Müller, Grebing, Klenke, Hoff, Paulus, Eidam and Limpert12], we employ nonlinear compression stages based on the well-established MPC product available at Active Fiber Systems GmbH[ 26] to achieve sub-6 fs pulse duration from the 300 fs output. Each MPC preserves the high beam quality of the Pharos front-end while also maintaining a contrast of 10–5 on the 100 ps scale and 10–10 on the nanosecond scale. The resulting system, integrating the Pharos front-end with two MPC stages, offers exceptional robustness and compactness, occupying a mere 3 m × 1.5 m optical breadboard. Integrated into one of the HHG beamlines at the ELI-ALPS facility[ Reference Kühn, Dumergue, Kahaly, Mondal, Füle, Csizmadia, Farkas, Major, Várallyay, Calegari, Devetta, Frassetto, Månsson, Poletto, Stagira, Vozzi, Nisoli, Rudawski, Maclot, Campi, Wikmark, Arnold, Heyl, Johnsson, L’Huillier, Lopez-Martens, Haessler, Bocoum, Boehle, Vernier, Iaquaniello, Skantzakis, Papadakis, Kalpouzos, Tzallas, Lépine, Charalambidis, Varjú, Osvay and Sansone27, Reference Charalambidis, Chikán, Cormier, Dombi, Fülöp, Janáky, Kahaly, Kalashnikov, Kamperidis, Kühn, Lepine, L’Huillier, Lopez-Martens, Mondal, Osvay, Óvári, Rudawski, Sansone, Tzallas, Várallyay and Varjú28], this system delivers record high flux for applications such as coincidence measurements[ Reference Ye, Oldal, Csizmadia, Filus, Grósz, Jójárt, Seres, Bengery, Gilicze, Kahaly, Varjú and Major29] and attosecond interferometry[ Reference Hammerland, Zhang, Kühn, Jojárt, Seres, Zuba, Várallyay, Charalambidis, Osvay, Luu and Wörner30], among others. The very high temporal contrast can also enable plasma dynamics studies. Since this laser system is coupled into the beamline of the HR1 laser system[ Reference Shestaev, Hoff, Sayler, Klenke, Hädrich, Just, Eidam, Jójárt, Várallyay, Osvay, Paulus, Tünnermann and Limpert2, Reference Hädrich, Shestaev, Tschernajew, Stutzki, Walther, Just, Kienel, Seres, Jójárt, Bengery, Gilicze, Várallyay, Börzsönyi, Müller, Grebing, Klenke, Hoff, Paulus, Eidam and Limpert12], it can be utilized to align experiments at lower average power while the HR1 system is unavailable: this system is labelled as the HR Alignment system. We note that, due to the outstanding stability of the laser, and repetition-rate tunability, the system is used far more often to perform experiments, rather than to provide an alignment beam.

In addition, both the HR1 and HR Alignment systems offer operational flexibility by providing a long-pulse mode with 30–35 fs pulse duration and 1.5 times higher pulse energy achieved through bypassing the second MPC stage. To address potential thermal effects at high repetition rates, the system allows for adjustable repetition rate operation while maintaining output pulse energy, beam quality and other beam parameters.

This paper reports on the design and comprehensive characterization of a high-performance, compact and turnkey sub-6 fs laser source mainly used for HHG and attosecond photoionization spectroscopy. We present a detailed analysis of the system’s performance, including the energy stability, beam profile, spectral and temporal characteristics and phase properties measured using the d-scan technique. We stabilize the CEP by a double f-2f setup (interferometric technique comparing frequency-doubled (2f) and fundamental (f) components of the laser spectrum to measure the CEP) and present the CEP stability out-of-loop measurement using a stereo-ATI measurement device[ Reference Hoff, Furch, Witting, Rühle, Adolph, Sayler, Vrakking, Paulus and Schulz31] with a phase tagging option. This system, with its CEP-stable front-end, two MPC compression stages and exceptional pulse characteristics, joins the suite of high-performance laser systems in the ELI-ALPS facility[ Reference Kühn, Dumergue, Kahaly, Mondal, Füle, Csizmadia, Farkas, Major, Várallyay, Calegari, Devetta, Frassetto, Månsson, Poletto, Stagira, Vozzi, Nisoli, Rudawski, Maclot, Campi, Wikmark, Arnold, Heyl, Johnsson, L’Huillier, Lopez-Martens, Haessler, Bocoum, Boehle, Vernier, Iaquaniello, Skantzakis, Papadakis, Kalpouzos, Tzallas, Lépine, Charalambidis, Varjú, Osvay and Sansone27, Reference Charalambidis, Chikán, Cormier, Dombi, Fülöp, Janáky, Kahaly, Kalashnikov, Kamperidis, Kühn, Lepine, L’Huillier, Lopez-Martens, Mondal, Osvay, Óvári, Rudawski, Sansone, Tzallas, Várallyay and Varjú28]. It uniquely provides high stability, 1 mJ pulse energy at tunable repetition rates between 10 Hz and 10 kHz and beyond, and CEP stability below 300 mrad out-of-loop, making it a valuable resource for fundamental and applied research within the HHG beamline for reaction microscope (ReMi) experiments.

2 System design and layout

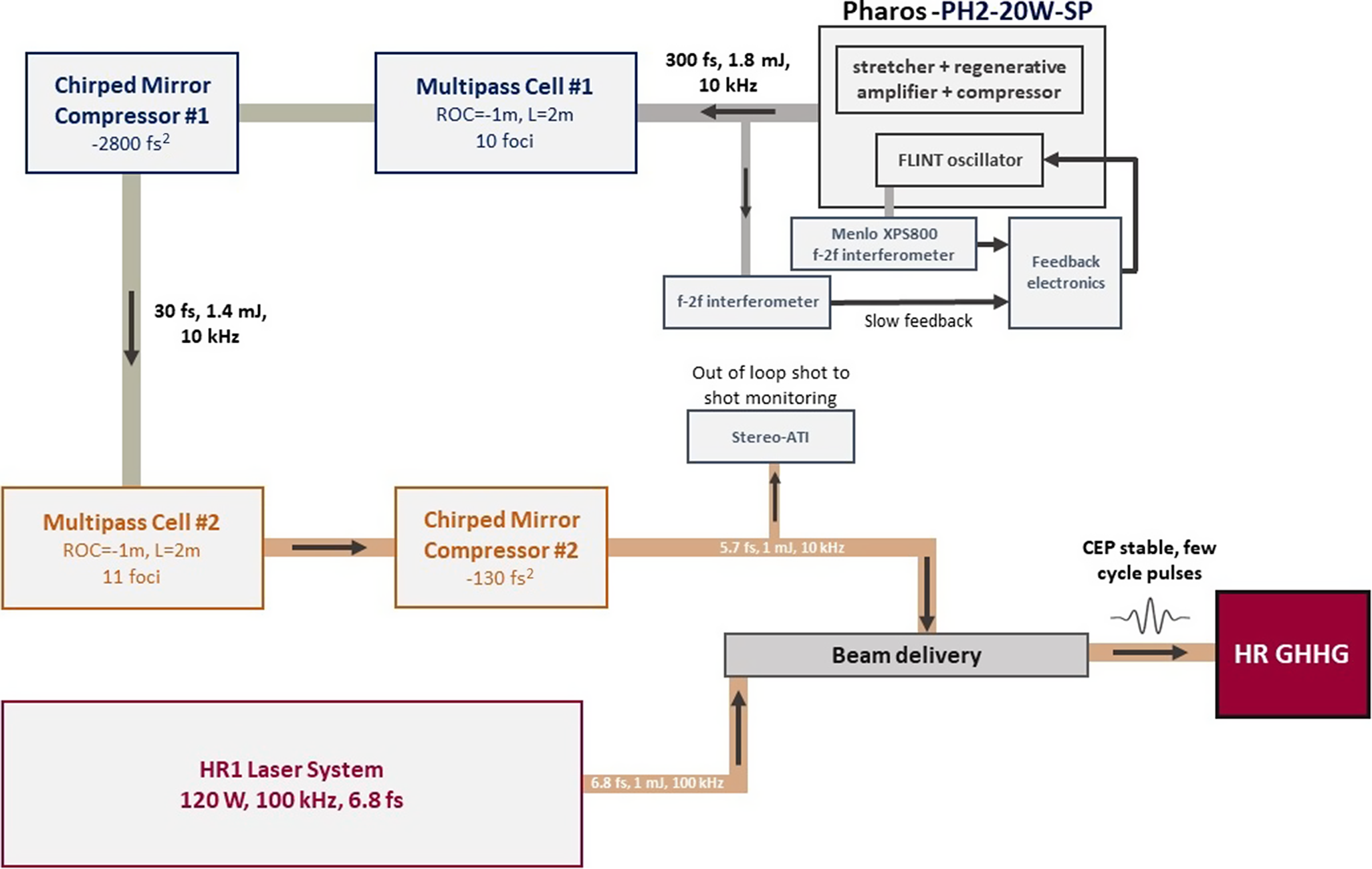

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the HR Alignment laser. The front-end is a commercially available Pharos-PH2-20W-SP laser[ 25], which delivers 1030 nm, CEP-stable pulses of 20 W output average power (up to 3 mJ pulse energy), 300 fs transform-limited pulse duration and a variable repetition rate up to 1 MHz. For most of this work, the Pharos laser was operated at 10 kHz repetition rate and 2 mJ pulse energy. CEP stabilization is achieved using two feedback loops. The output of the first f-2f interferometer (XPS800 by Menlo) is used to stabilize the carrier-envelope offset (CEO) frequency of the 76 MHz oscillator. The second f-2f interferometer measures the relative CEP of the Pharos output and provides feedback to the oscillator to compensate for long-term CEP drift.

Figure 1 Schematic layout of the HR Alignment laser system. The drawing includes the separate HR1 laser system, the beam delivery system (light gray boxes with dashed borders) and the gas HHG chamber. Injection points into the beam delivery system indicate the position of the two systems each sharing the same beamline, namely the output of HR1 is farther from the HHG point than that of the HR Alignment system.

The first compression stage employs an MPC with a cavity length of 2 m and mirrors with –1 m radius of curvature (ROC). Ten focal passes are implemented in a krypton gas medium at 0.6 bar pressure. After spectral broadening, the pulses are compressed by chirped mirrors that compensate for a total of 2800 fs2 of group delay dispersion (GDD). A part of the chirped mirrors (four pieces) is still in the first MPC chamber in 0.6 bar krypton gas, while two of them are outside of the chamber in air and another two mirrors are placed in the second MPC in our configuration. The mirrors do not require additional cooling but the optical breadboard that they are placed on is water-cooled. This setup can provide 1.4 mJ, 30 fs pulses with excellent spatial and spectral quality. The second MPC has the same 2 m cavity length and mirrors with the same ROC but utilizes 11 focal passes in 0.15 bar of argon. The compression after the first MPC stage uses eight reflections on Gires–Tournois interferometer (GTI) type mirrors (Laseroptik GmbH) with a wavelength range of 980–1080 nm and –350 fs2 GDD. The compressor after MPC2 also consists of chirped mirrors adding –248 fs2 of GDD and –247 fs3 of third-order dispersion (TOD) to the pulses. The first pair of mirrors is located inside MPC2, in argon (wavelength range is 700–1400 nm, GDD is –67 fs2/reflection), while the second pair is outside of the chamber, in air (GDD is –64 fs2/reflection and TOD is –62.75 fs3). This is sufficient to achieve transform-limited duration at the output of MPC2. For absolute CEP measurement, 10% of the 1.1 mJ output energy is sampled out for the stereo-ATI (Single Cycle Instrument); therefore, an additional number of –134 fs2 worth of chirp mirror bounces is applied at the output of the laser system, also in air. In this way, the 3 mm fused silica material of the sampler and the dispersion of the air propagation in the sampled beam path could have been well compensated. The stereo-ATI measures the out-of-loop shot-to-shot CEP of the sub-two-cycle pulses providing phase tagging capabilities for experiments.

The laser system, comprising the Pharos front-end and an AFS post-compression module, provides a turnkey system to drive experiments. Repetition-rate independence is facilitated by a Pockels cell in the front-end that enables precise repetition rate control at this power level. This is not only a highly reliable system, but as we demonstrate below it also possesses repetition-rate-independent operation that is considered an additional benefit. The following section details the key characteristics of the system, including its long-term stability and repetition-rate independence.

3 Results

3.1 Energy stability and spatial quality

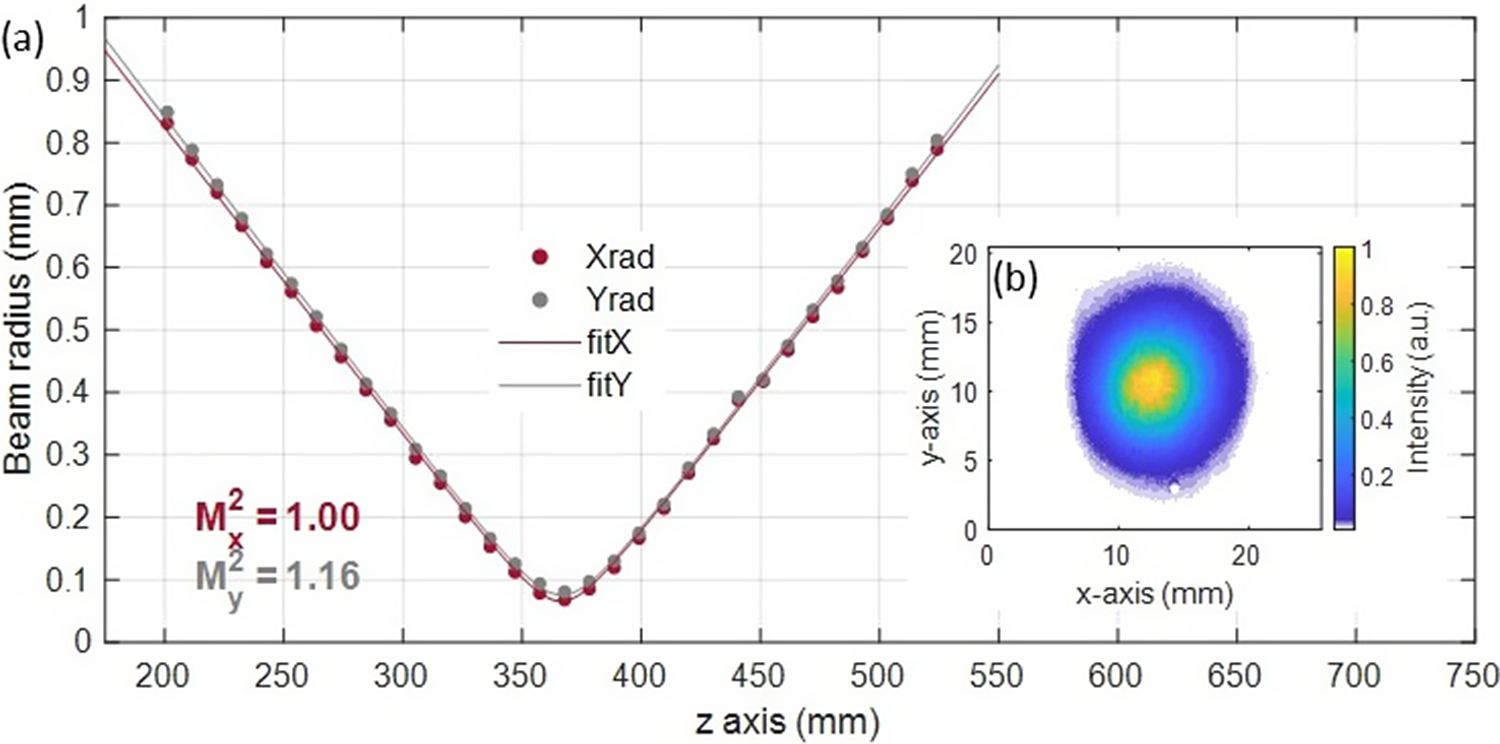

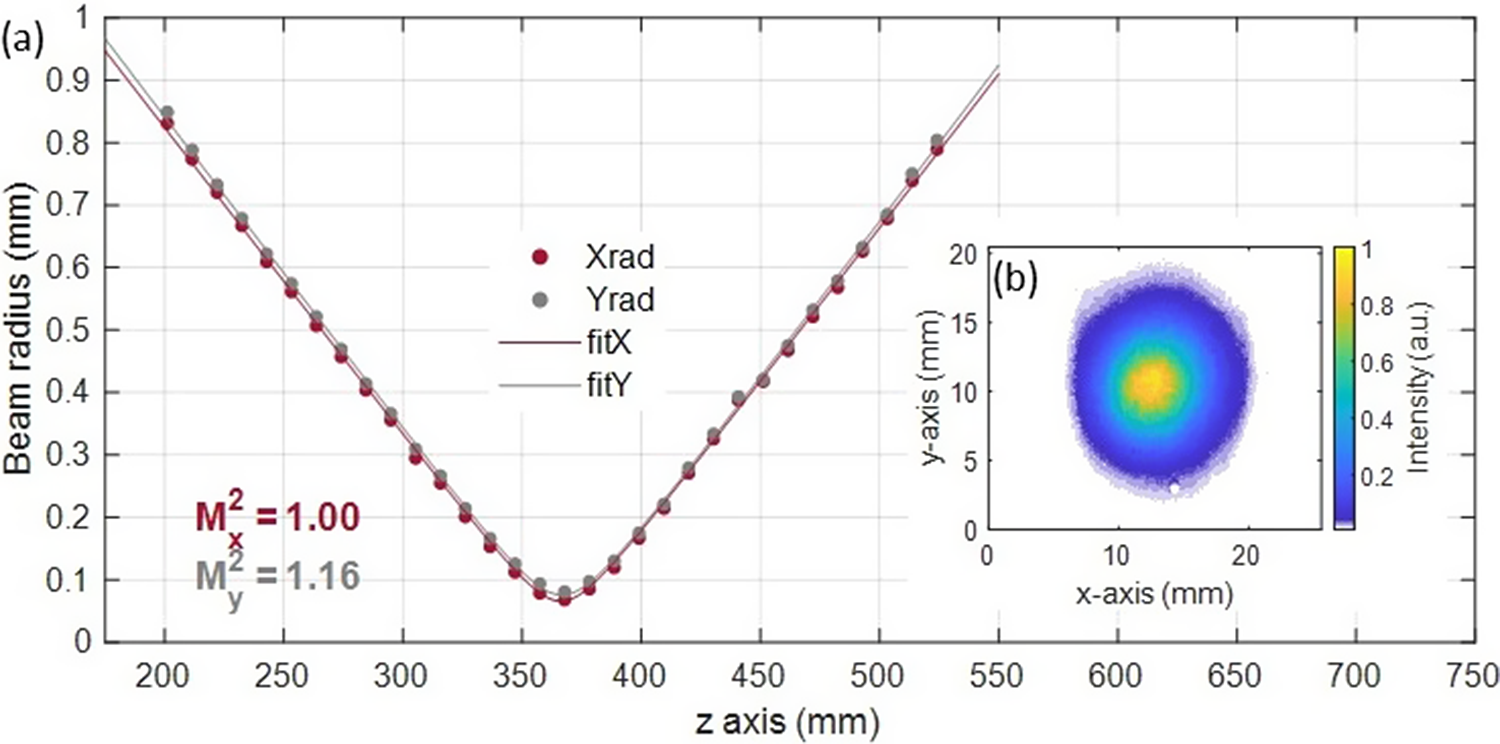

The integrated active power locking of the front-end results in exceptional output energy stability, with a root-mean-square (RMS) fluctuation of less than 0.04% measured over 1 h. Active beam stabilization using motorized mirrors achieves excellent pointing stability, with fluctuations below 25 μrad over a 4-h measurement. The beam quality, characterized by the M 2 parameter, was measured using a Gentec Beamage-M2 device (see Figure 2). The measured M 2 values were 1.0 and 1.16 for the x- and y-axes, respectively. Figure 2 also shows the spatial profile of the output beam in the near-field. The ellipticity of the beam remains between 0.94 and 1.00 throughout the whole caustic, with a value of 0.99 in the near-field and 0.94 in the far-field. The astigmatism was found to be 0.04% of the focal length, and the Strehl ratio was found to be 0.95. This near-ideal beam quality stems not only from the excellent spatial characteristics of the front-end but also from the spatial filtering effect of the nonlinear interaction within the MPCs. The nonlinear interaction occurs near the far-field of the focusing optics and operates close to the critical power for self-focusing. This regime leads to a spatial filtering effect within the MPCs, further improving the beam quality. The spatial quality remained unchanged across other repetition rates; we experienced 2% standard deviation in the values of the beam diameter. The M 2 parameter together with the caustic is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Characterization of the output beam spatial quality. (a) M 2 measurement, demonstrating near-diffraction-limited performance. (b) Near-field beam profile exhibiting spatial homogeneity.

3.2 Temporal and spectral quality

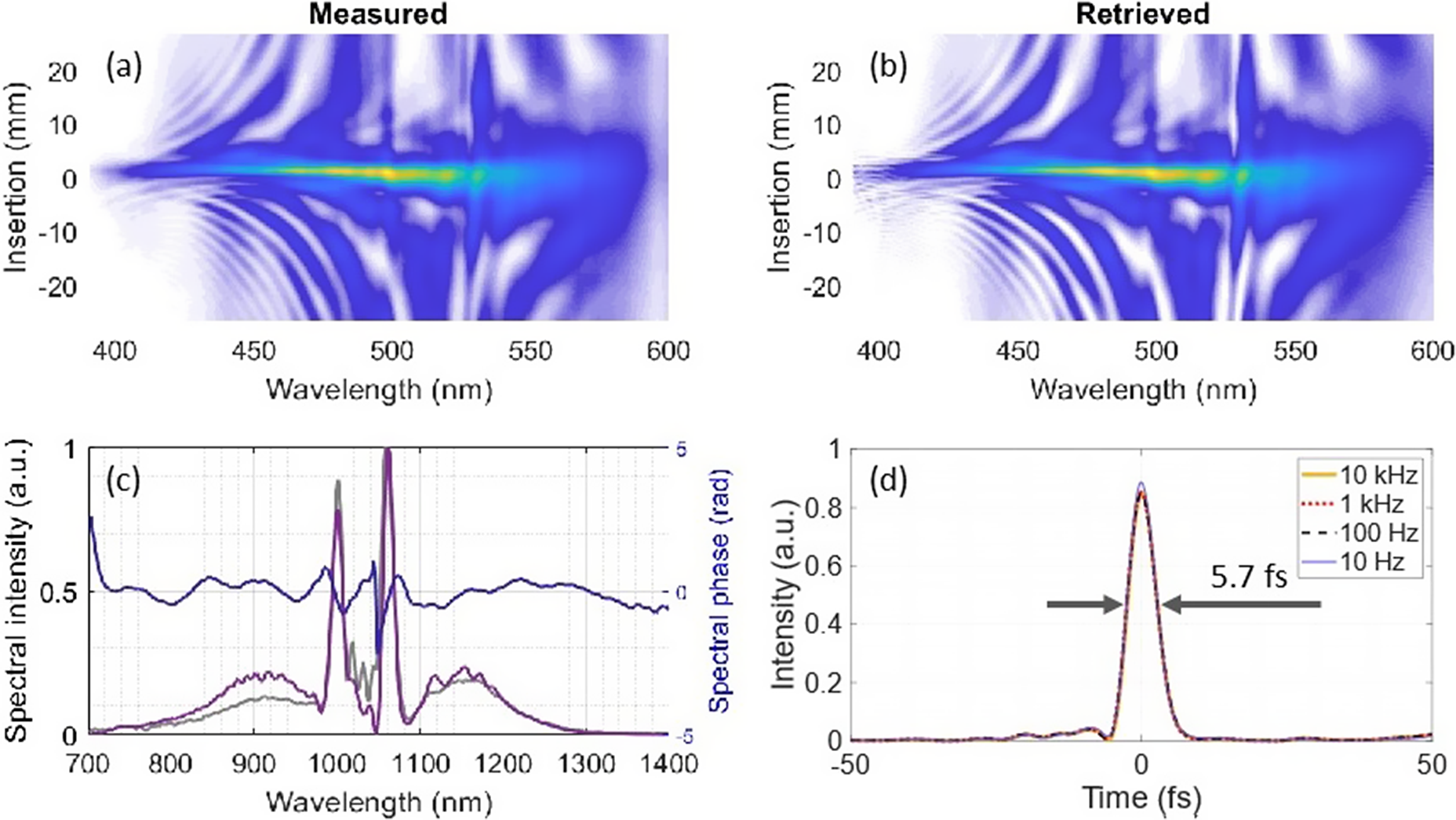

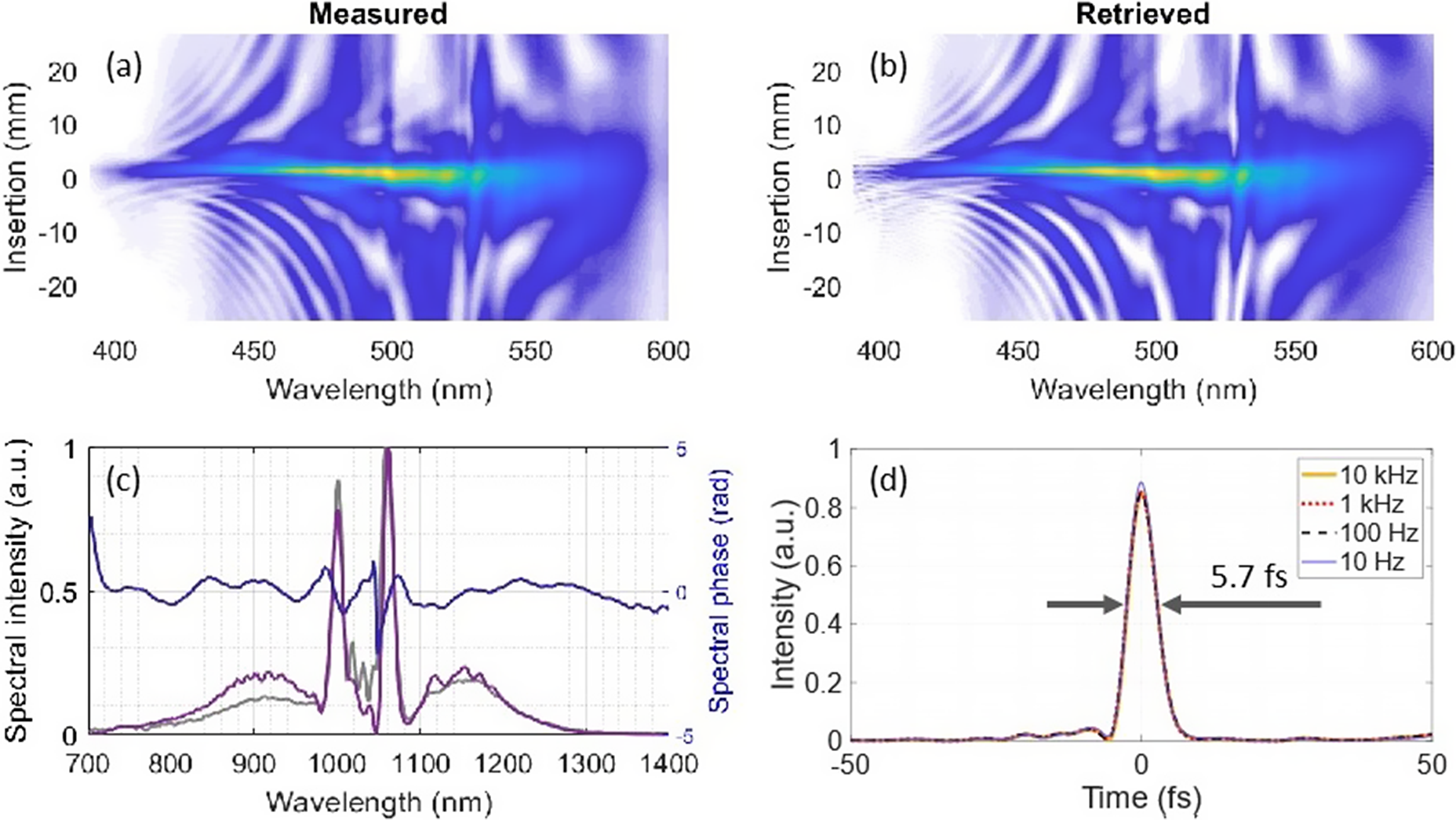

The temporal shape of the output pulses, measured by a d-scan device (Sphere Photonics, D-cycle NIR 700-1400), revealed a transform-limited pulse duration of 5.7 fs full-width at half maximum. The measured and retrieved d-scan traces are shown in Figure 3. The main peak of the pulse contains 86.3% of the total energy, with the remaining energy residing in the sidelobes. As depicted in Figure 3(d), the retrieved pulse shapes, recorded at various repetition rates between 10 Hz and 10 kHz, clearly demonstrate the repetition-rate independence of the laser pulses with a duration of 5.7 ± 0.1 fs.

Figure 3 (a) Measured and (b) retrieved d-scan trace of the output pulses of the HR Alignment laser system. (c) Measured (gray) and retrieved (purple) spectra and spectral phase (blue) and (d) reconstructed temporal shape of the output pulses recorded at different repetition rates. The consistent, overlapping pulse profiles confirm repetition-rate-independent operation.

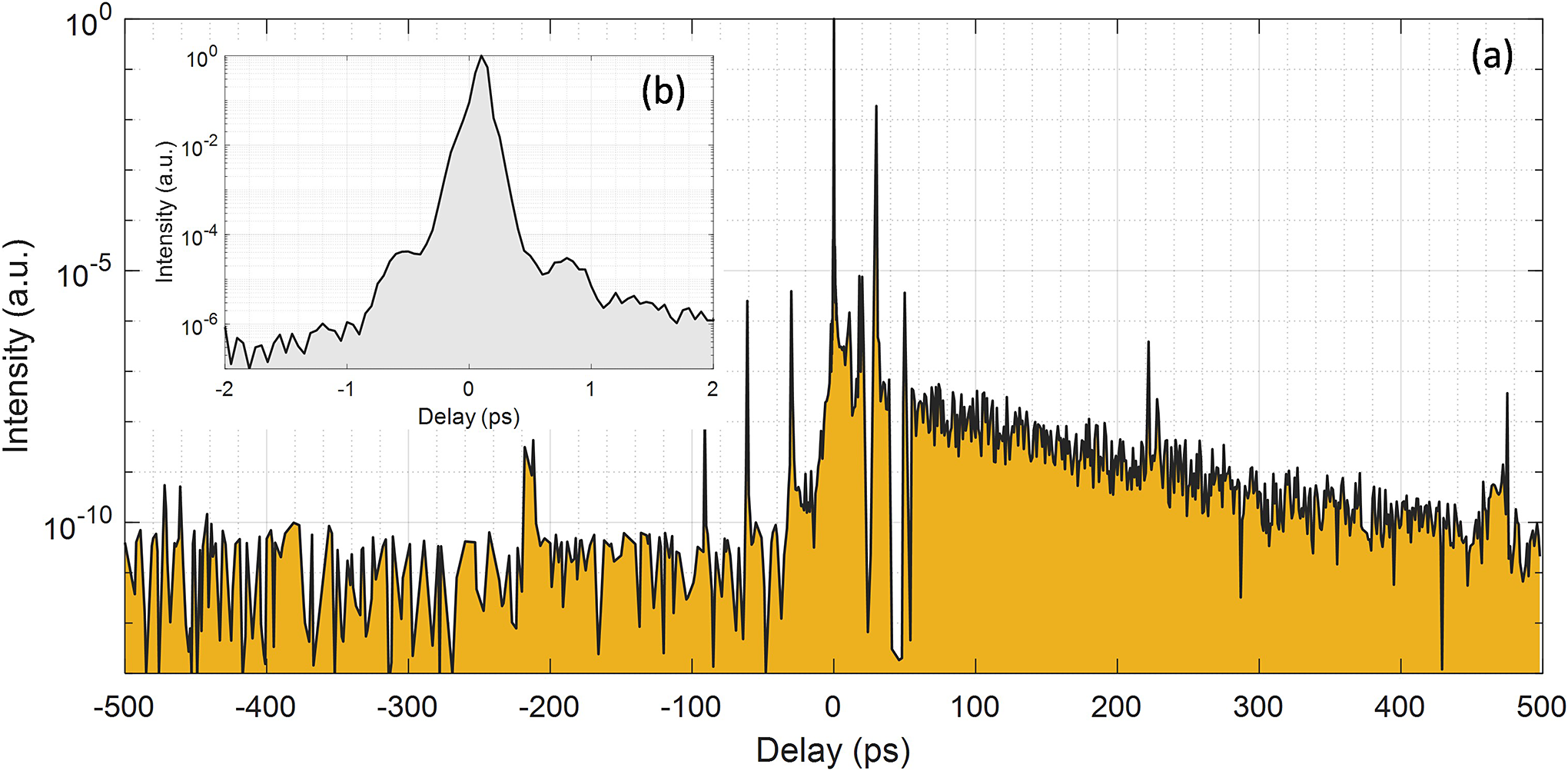

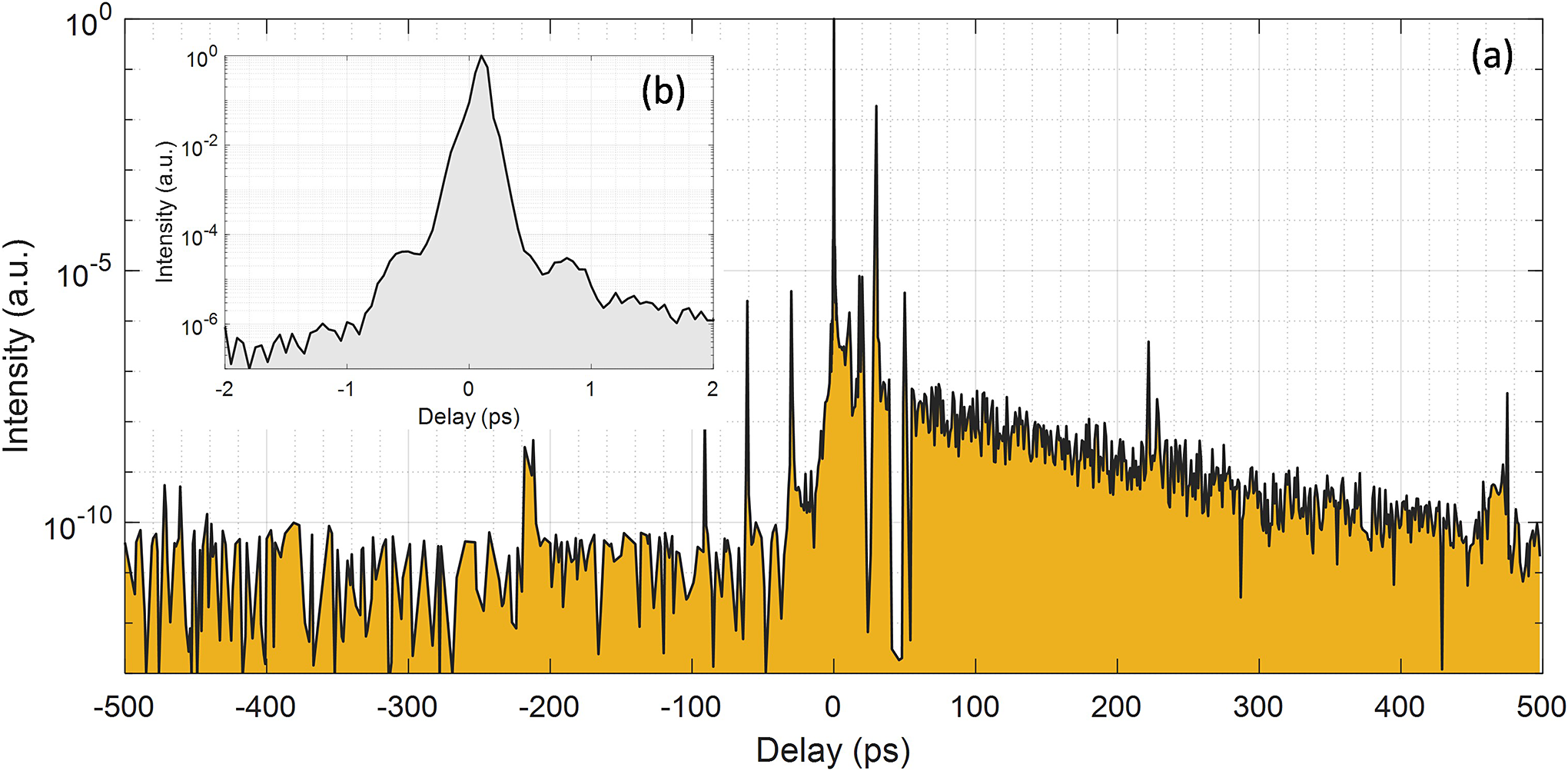

Given that the intensity contrast of pre-pulses is crucial in light–matter interaction experiments, we measured the third-order autocorrelation trace of the output pulses using a TUNDRA+ 1030 nm device (Ultrafast Innovations). Figure 4 displays the measured third-order autocorrelation trace on a –500 to 500 ps scale, with an inset detailing the –2 to 2 ps range. The relative intensity on the pre-pulse side drops below 10–6 level at –2 ps, indicating excellent main peak quality. The post-pulse at 30 ps of the 10–2 level is attributed to the beam sampler used for the contrast measurement. While pre-pulses are observed at –220 and –90 ps, their intensity at the target is estimated to be significantly below the ionization threshold for the materials of interest in typical attosecond and reaction microscopy experiments. This estimation accounts for the relative energy of the pre-pulses, the beam focus at the interaction point and the typical ionization potentials of atoms and molecules studied in these experiments. The background level drops below 10–10 approximately 50 ps before the main pulse and remains at this level across the entire measured range. Overall, the contrast of the pedestal before the main pulse is excellent with an ASE contrast of 10–10. However, the presence of some pre-pulses under the 10–5 level warrants further investigation. The measured contrast is obtained at a 10 kHz repetition rate but remains consistent across all other repetition rates.

Figure 4 Third-order autocorrelation trace of the output pulses of HR Alignment between –500 and 500 ps delay. Inset is a zoom to the region between –2 and 2 ps.

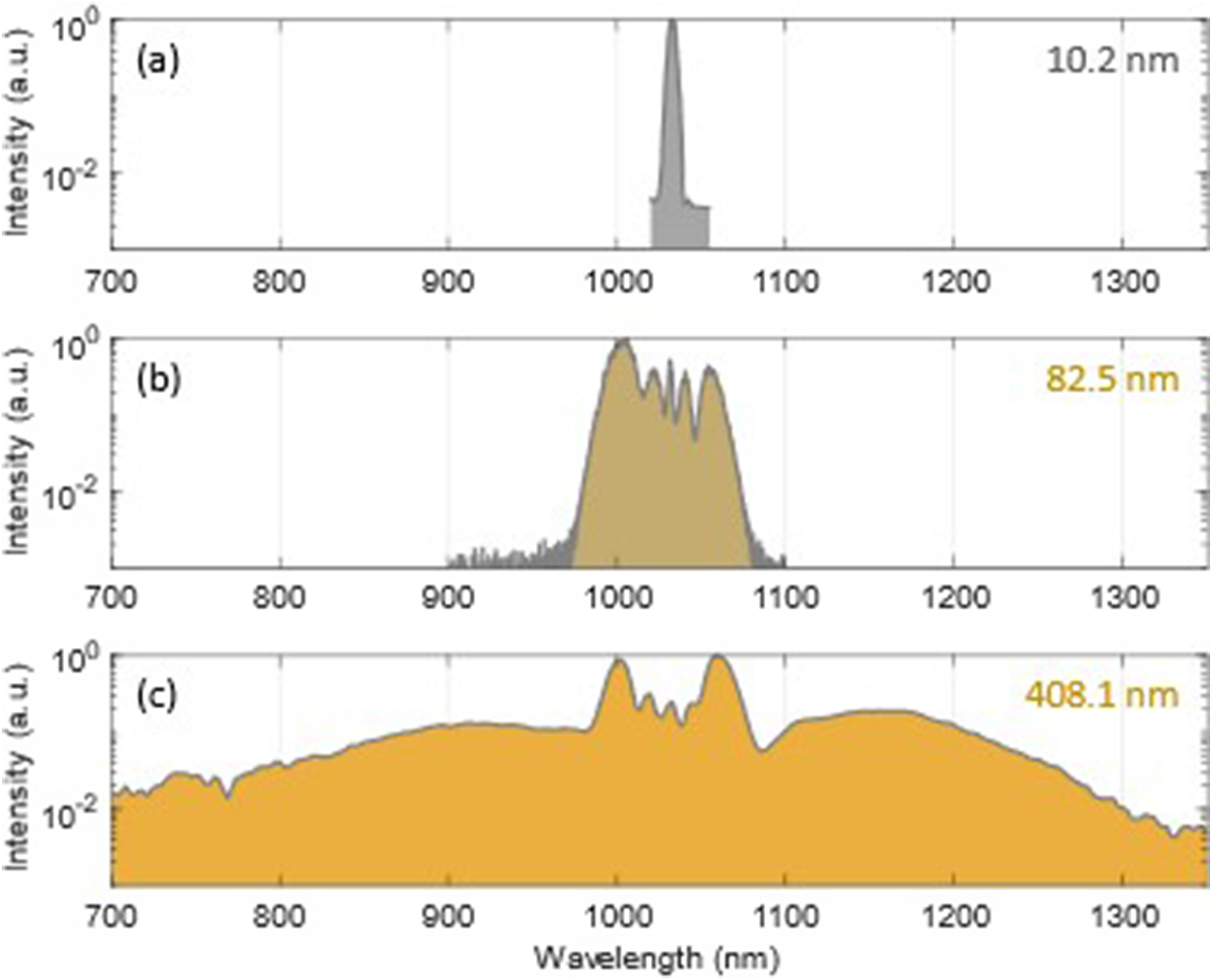

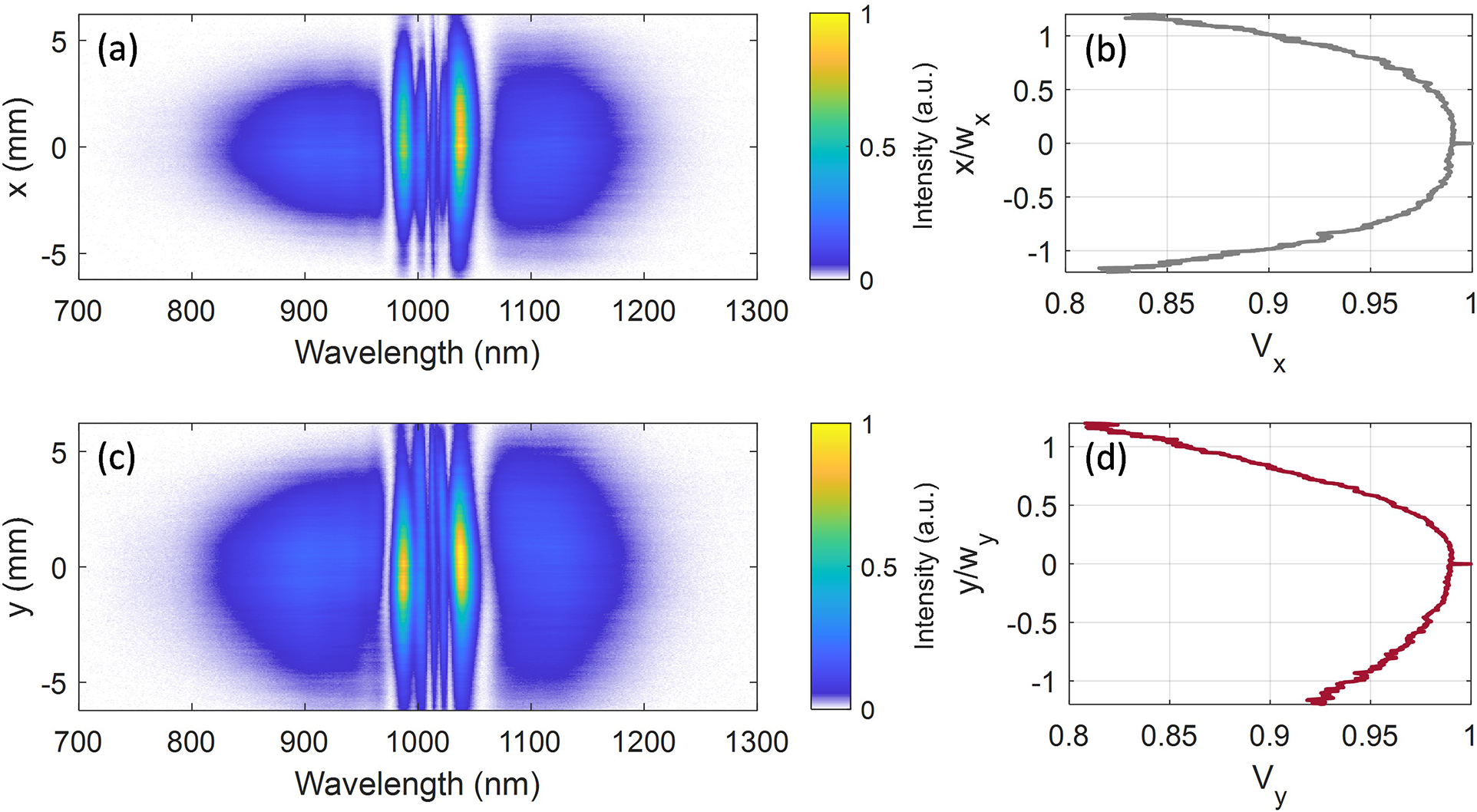

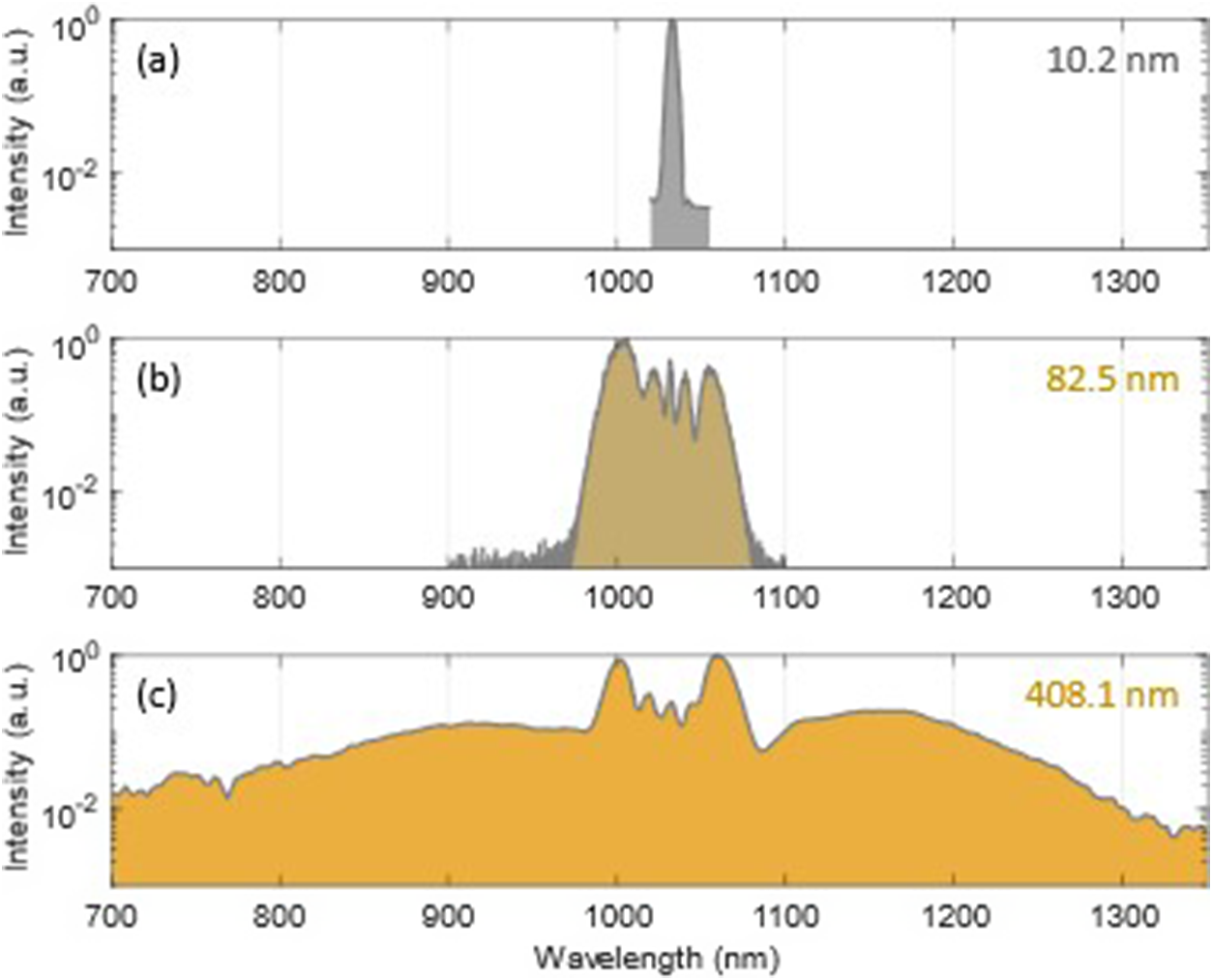

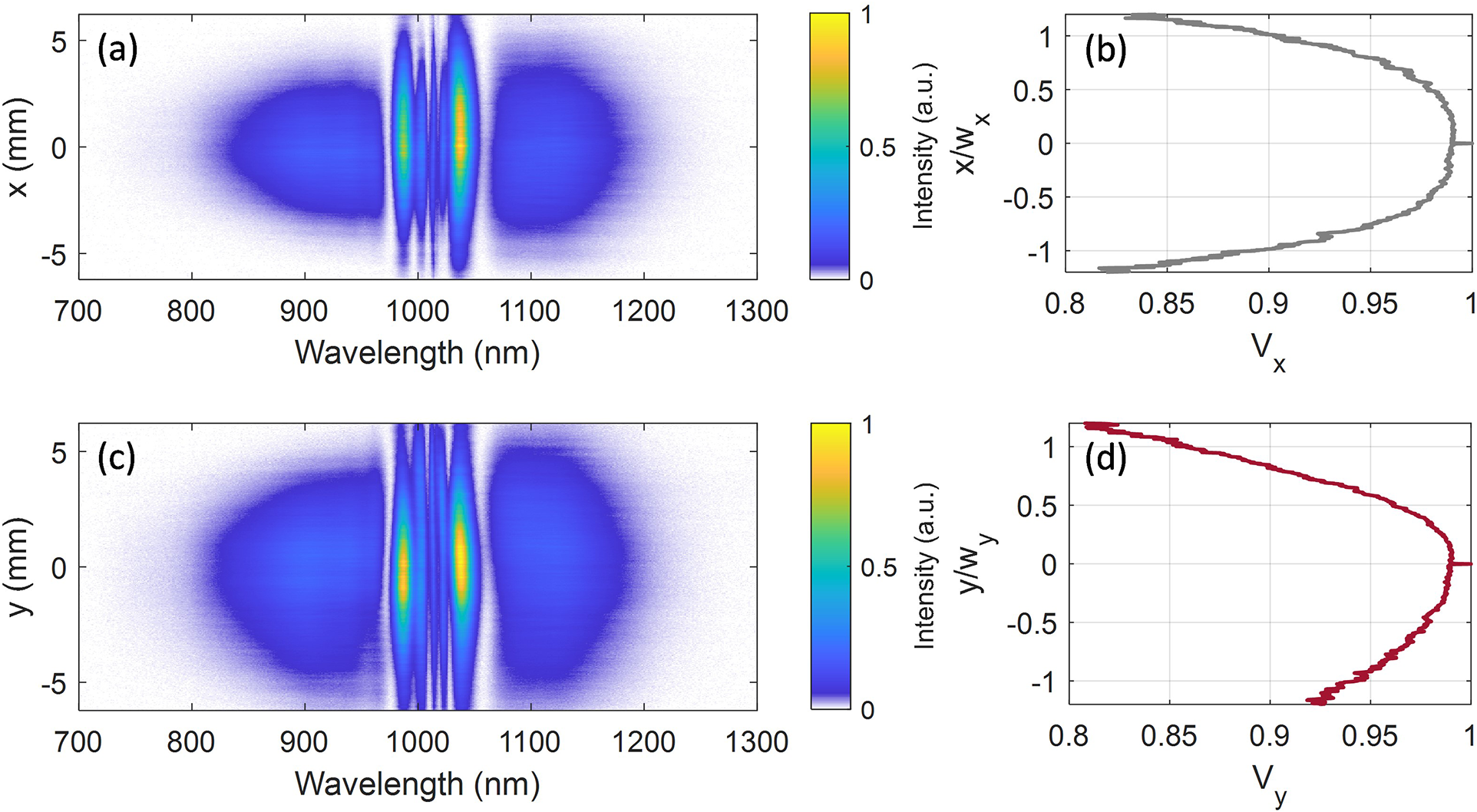

Maintaining a uniform spectral phase distribution during spectral broadening is crucial for achieving temporally clean pulses. Spectral evolution within the laser system is visualized in Figure 5. The two MPCs achieve sequential spectral broadening, resulting in an overall 40-fold increase in bandwidth compared to the front-end output. As previously mentioned, the nonlinear interaction repeatedly occurs in the far-field where spatial and spectral characteristics are intertwined. Therefore, the excellent spatial quality contributes significantly to achieving homogeneous spectral broadening across the entire beam profile. This homogeneity presents a key challenge for post-compression techniques. To assess this spectral homogeneity, we measured the output beam spectrum both horizontally and vertically using a two-dimensional (2D) spectrometer. The measured spectra at a 10 kHz repetition rate are shown in Figure 6 and remain equivalent across all repetition rates with a standard deviation of 3 nm.

Figure 5 Spectral evolution of the pulse from the front-end (a) through the first MPC stage (b) to the last compression stage (c). Post-compression in two noble gas filled multi-pass cells is performed. Spectral width is denoted at –13 dB corresponding to 5% power bandwidth. Only close proximity of the essential region of the spectrum is measured. The plots are presented for a 10 kHz repetition rate, but when tested at lower repetition rates the figures look almost identical.

Figure 6 Vertical (a) and horizontal (c) spatially resolved spectrum measurement of the output pulses on a linear scale; the corresponding spectral homogeneity V parameter values are visualized in (b) and (d), respectively.

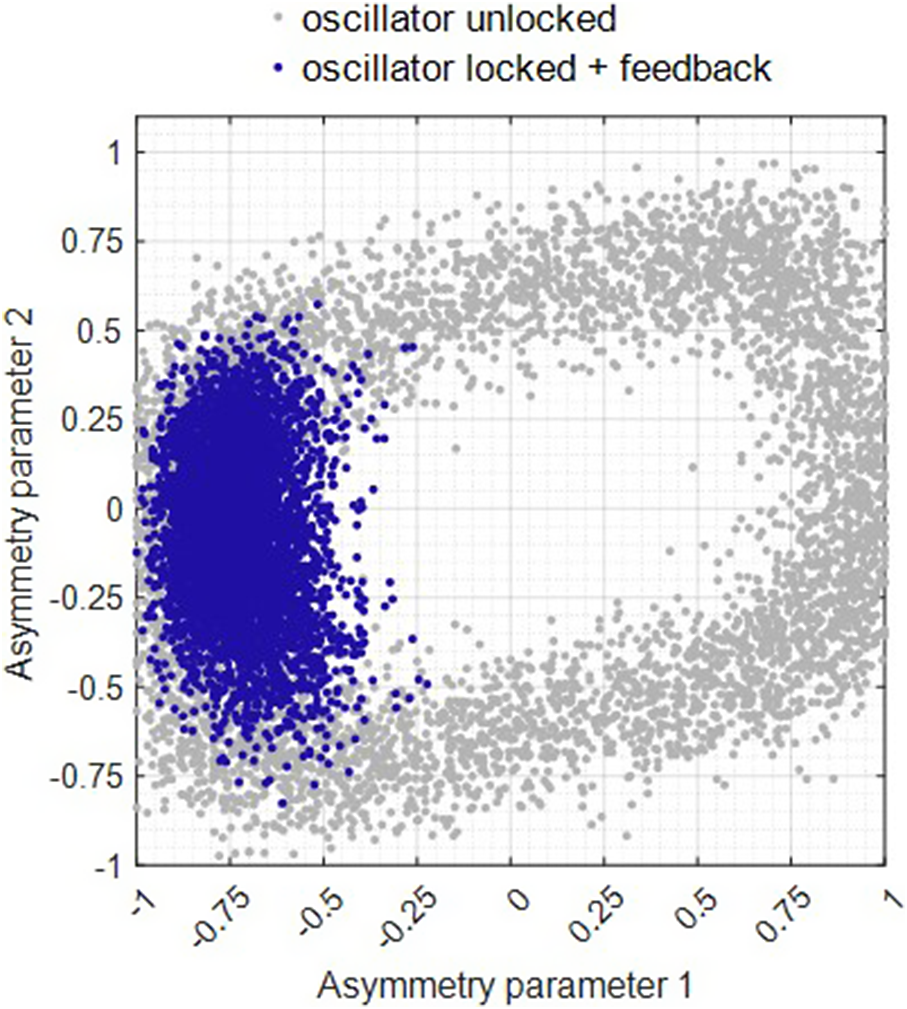

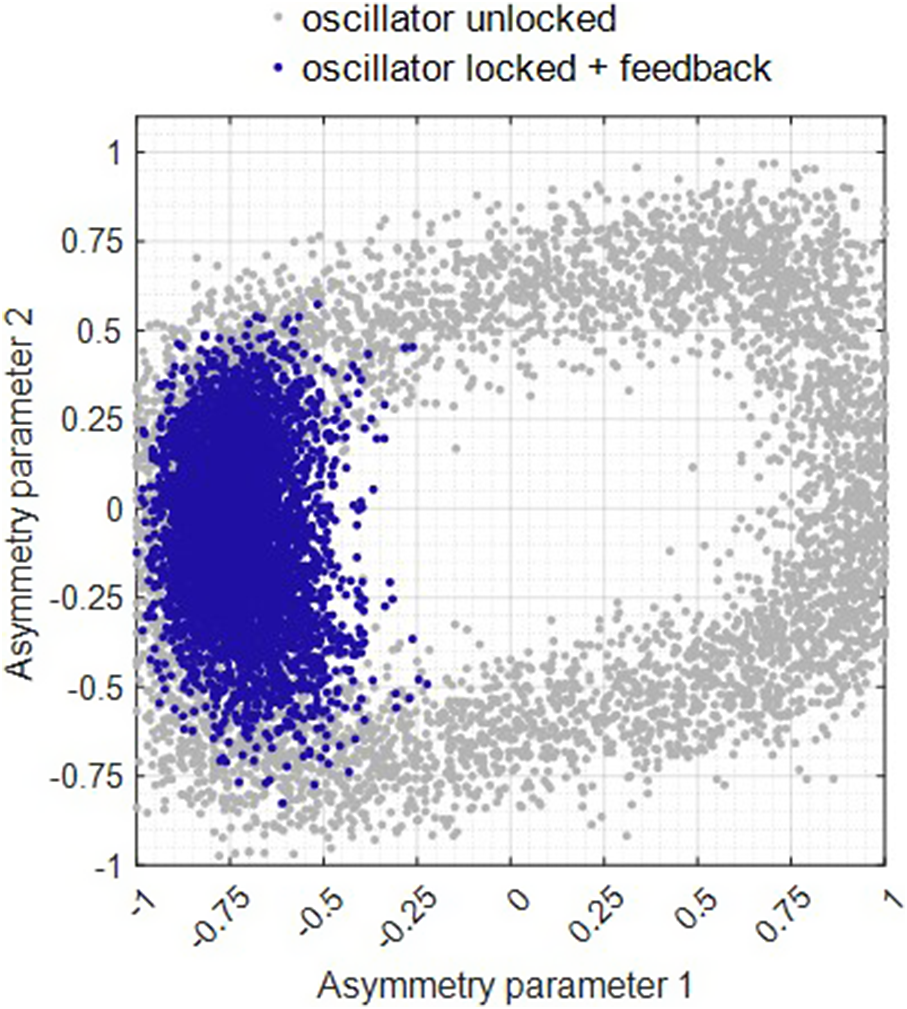

Figure 7 Result of the CEP measurements by the stereo-ATI instrument at 10 kHz repetition rate. Gray dots are shot-to-shot measurements when CEP stabilization is not applied, while blue dots represent the operation with feedback from the f-2f interferometer.

3.3 Carrier-envelope phase stability

The system employs a two-stage CEP stabilization scheme, as shown in Figure 1. The first stage stabilizes the CEO frequency (

![]() ${f}_{\mathrm{ceo}}$

) of the oscillator directly, while a second f-2f interferometer is placed after the front-end and before the first MPC stage. The second f-2f interferometer measures and corrects for slow thermal drifts originating in the amplifier chain by feeding a correction signal back to the pump diodes of the amplifier.

${f}_{\mathrm{ceo}}$

) of the oscillator directly, while a second f-2f interferometer is placed after the front-end and before the first MPC stage. The second f-2f interferometer measures and corrects for slow thermal drifts originating in the amplifier chain by feeding a correction signal back to the pump diodes of the amplifier.

Passive components, including the gas-filled MPCs, can also introduce CEP noise. The primary sources of jitter within the MPCs are as follows: (i) gas pressure fluctuations and thermal conductions; (ii) beam pointing instabilities that cause optical path length variations; and (iii) gas ionization, which can severely degrade CEP stability. We mitigate these effects through precise pressure control, active beam stabilization and by operating below the gas ionization threshold.

The effectiveness of this stabilization feedback loop[ Reference Hoff, Furch, Witting, Rühle, Adolph, Sayler, Vrakking, Paulus and Schulz31] is demonstrated in Figure 7. When the oscillator is unlocked (gray dots), the asymmetry parameters are widely distributed, indicating significant CEP fluctuations (this distribution also supports the fact that the pulses are sub-two-cycle). With the oscillator locked and feedback loop active (blue dots), the asymmetry parameters cluster tightly. This tight clustering confirms the effectiveness of the active stabilization. The out-of-loop CEP noise, evaluated using the feedback loop and locked oscillator setup, remains below 300 mrad. This value was determined by calculating the standard deviation of the phase (derived from the asymmetry parameters) over 1-s intervals as described in Ref. [Reference Hoff, Furch, Witting, Rühle, Adolph, Sayler, Vrakking, Paulus and Schulz31] and was confirmed at both 1 and 10 kHz repetition rates. Below the 1 kHz repetition rate, the phase jitter noise specifications of the Pharos front-end show a constant integrated phase jitter. Also, we tested that switching off the second-stage CEP stabilization system results in a CEP drift on a time scale of a few seconds (typically 3–4 s), indicating the lack of significant noise components at frequencies relevant to the pulse picking. Consequently, changing the repetition rate of the front-end via the pulse picker does not affect the intrinsic CEP stability of the system. The obtained 300 mrad

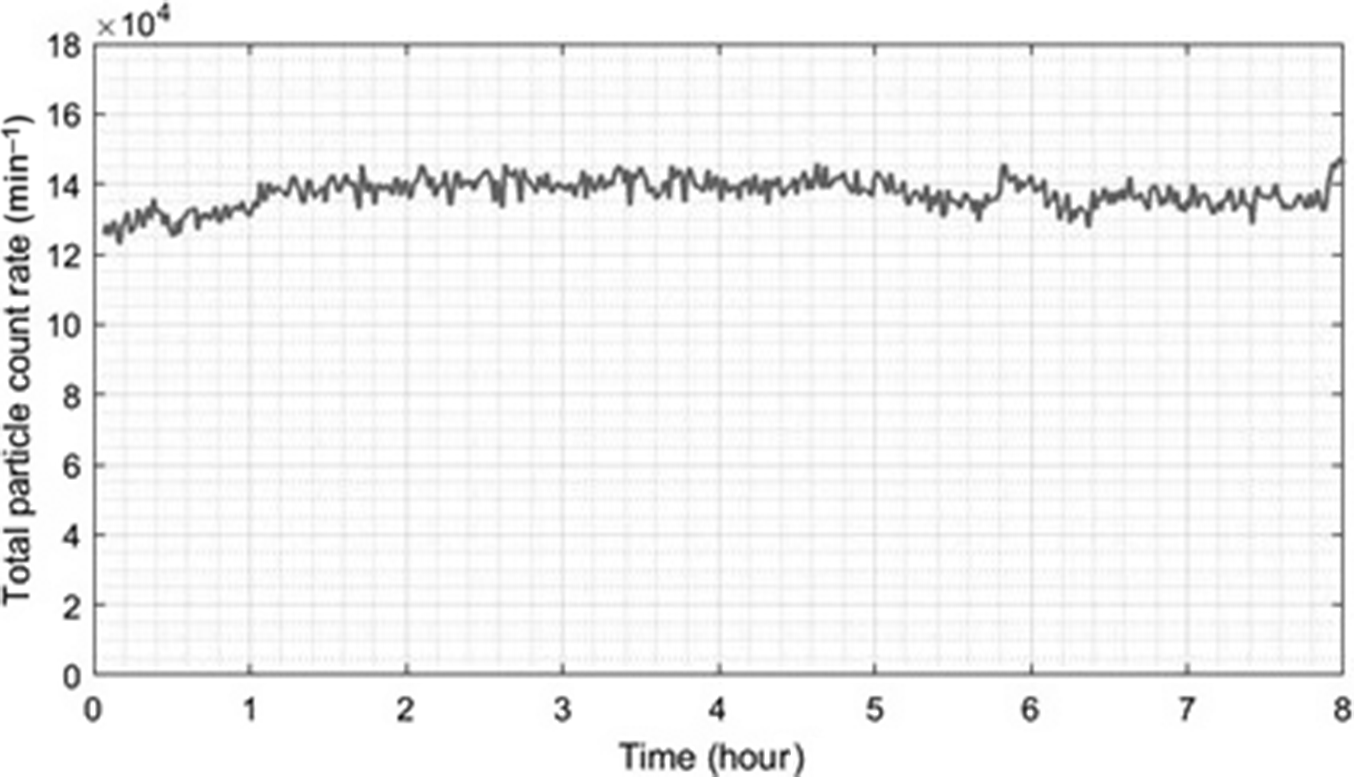

Figure 8 Time evolution of the particle count rates of photoelectrons and photoions from one-photon single ionization of argon by XUV light recorded with a C-ReMi end-station during an 8-h long acquisition at a 10 kHz laser pulse repetition rate.

CEP noise value can be slightly improved by placing the second f-2f interferometer after the MPC compression stages or applying the feedback from the stereo-ATI. While placing the second f-2f interferometer after the final MPC stage would also compensate for jitter introduced within the MPCs, which is, however, a relatively small contribution, this approach presents a significant technical challenge. The spectrum after the second MPC is extremely broad and highly structured, making it difficult to obtain the clean and stable, high signal-to-noise ratio white light required for a stable lock. Placing the f-2f interferometer before this final stage ensures a more robust and reliable signal for the feedback loop considering the present design of the f-2f.

3.4 Application in photoelectron spectroscopy of gas-phase targets

The presented CEP-stable few-cycle pulses of HR Alignment can drive, among other target areas, the HR Gas beamline of the ELI-ALPS facility. This beamline produces attosecond pulse trains for extreme ultraviolet (XUV)–infrared pump–probe measurements. Located in the same laboratory as the laser system, HR Gas is equipped with a ReMi (also known as a cold target recoil ion momentum spectrometer, C-ReMi) experimental end-station that enables kinematically complete reconstruction of photoinduced dissociation fragments with attosecond temporal resolution. Figure 8 shows that under stable environmental and experimental conditions, the stability of HR Alignment supports stable particle counts over at least 8 h of data acquisition with the C-ReMi at a 10 kHz repetition rate. This dataset illustrates the exceptional stability of the HR Alignment laser, as we observe a stable HHG signal, which would amplify the instabilities in the laser parameters due to its highly nonlinear nature. This also proves that the system carries great potential for future user experiments targeting time- and angle-resolved photoelectron-photoion spectroscopy, which by nature requires long acquisition times for achieving sufficient particle statistics. We note that by using this laser with the beamline we have successfully run uninterrupted measurements for more than 5 days.

4 Conclusion

We have presented a compact, high-repetition-rate, CEP-stable laser system delivering sub-6 fs pulses with greater than 1 mJ energy, specifically designed for driving HHG and attosecond spectroscopy. Based on a commercially available Pharos laser front-end with adjustable repetition rate and two nonlinear compression stages, the system offers exceptional performance in terms of energy stability, beam quality, temporal contrast, CEP stability and repetition-rate independence. These critical properties have been thoroughly measured and presented in this paper, with repetition-rate independence specifically proven and discussed for each individual measurement. Integrated into the HR Gas beamline at the ELI-ALPS facility, this turnkey system provides a valuable resource for ultrafast research, enabling experiments with unprecedented precision and control over light–matter interactions on the attosecond timescale. Demonstrating very high long-term stability (over days), and similar performance to the HR1 laser (except for repetition rate), this system highlights how robust turnkey solutions can sometimes be more beneficial for research applications than systems, where all the parameters are pushed to their absolute limits.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all the valuable contributions from Light Conversion, Active Fiber Systems (AFS) GmbH, FSU Jena, Single Cycle Instrument and Sphere Ultrafast Photonics.

The ELI-ALPS project (GINOP-2.3.6-15-2015-00001) is supported by the European Union and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund.